1. Introduction

The increasing complexity and frequency of cyber threats in distributed computing environments has necessitated the advancement of machine learning-based defense systems that are both intelligent and privacy-preserving. Traditional centralized learning models, while powerful, are inherently susceptible to critical problems such as data leakage, excessive communication direction, and single points of failure. Federated Learning (FL) emerges as a robust alternative, allowing the training of a collaborative model across decentralized devices without the transfer of initial data to the central server. This decentralized paradigm preserves user privacy, reduces systemic vulnerability, and ensures compliance with regulatory constraints.

FL has demonstrated significant potential in constrained and dynamic environments, including underwater drone networks, where high latency and limited bandwidth challenge centralized learning. For example, Popli et al [

3] proposed a federated framework tailored for underwater drones that improved zero-day threat detection while maintaining strict data locally. These applications highlight the ability of FL to support localized learning while maintaining high detection accuracy under extreme conditions.

A key concern in FL research is balancing efficiency with privacy. Recent techniques using gradient clipping and Fisher information-based parameter selection have proven effective in reducing communication overhead without sacrificing accuracy [

4]. These lightweight mechanisms optimize model performance while minimizing resource consumption and data exposure, making FL feasible for deployment in bandwidth-constrained networks.

To address the inherent challenges posed by non-independent and identically distributed (non-IID) data across clients, several frameworks have introduced multi-objective and multi-tasking FL strategies. These include client clustering, personalized updates, and fairness-aware optimization, which collectively improve generalization and fair performance across different data distributions [

5].

On a broader scale, FL has gained traction in distributed cloud computing architectures, where it complements secure multiparty computation, trusted execution environments, and differential privacy. Rahdari et al [

6] highlighted the role of FL in enhancing privacy-aware data analytics and mitigating the risks associated with centralized storage in cloud-native infrastructures.

As FL systems become more personalized, they face new threats such as model poisoning and stealthy backdoor attacks. Defense strategies such as adaptive layered trust aggregation and anomaly detection based on gradient similarity offer promising solutions that increase robustness against adversarial manipulation [

7].

In rapidly evolving, containerized, and cloud-native ecosystems, flexible protection architectures are essential. AI-driven adaptive security networks have been proposed to support real-time anomaly detection in federated cloud environments [

8], in line with the decentralized nature of FL. Such systems dynamically adapt to evolving attack surfaces, improving responsiveness and resilience.

Security in FL is further enhanced by advances in cryptographic techniques. For example, delegable order-revealing encryption (DORE) enables secure multi-user range queries without relying on trusted intermediaries, preserving confidentiality while maintaining operational efficiency [

9]. In addition, the integration of blockchain with FL brings transparency, immutability, and trust to model update workflows. Blockchain-enabled FL architectures ensure auditable, tamper-proof exchanges between participants, protecting against adversarial interference and dishonest contributions [

10].

In the large-scale deployment of private data protection - for example, smart city, networked medical systems, and industrial internet of things - the use of FL frameworks has shown promising results. Kotian et al [

11] emphasized the importance of combining FL with light encryption, anomaly detection, and adaptive privacy mechanisms to meet compliance standards (e.g., GDPR, HIPAA) without compromising efficiency. In summary, this development shows that FL is a mature enabling technology for secure, scalable, and privacy-aware cybersecurity solutions. Continued innovation in the penetration of artificial intelligence, cryptography, and distributed architecture remains necessary to overcome emerging threats and deploy resilient defenses in real-world infrastructure.

2. Related Work and Background

The development of cyber safety threats and increasing demand for privacy focused privacy solutions have significantly expanded research into FL applications. While traditional centralized machine learning methods remain strong, they show critical restrictions such as data leakage, narrow communication spots and exposure to individual points of failure. These disadvantages are particularly important in IoT ecosystems, where a huge number of connected devices work over sensitive data protection data.

The challenge of learning from non-IID data across heterogeneous clients has led to the development of multi-objective and multi-task federated learning strategies, with studies showing improved accuracy and fairness in real-world scenarios [

5]. In parallel, efforts to integrate FL within distributed cloud computing infrastructures have leveraged secure multiparty computation, trusted execution environments, and differential privacy to provide robust and privacy-preserving analytics across nodes [

6].

Personalization in FL has emerged as a key area, enabling the adaptation of models to individual clients while defending against advanced threats. Defense mechanisms based on gradient similarity and layered trust policies have shown improved robustness in countering stealthy backdoor attacks, without compromising collaborative learning [

7]. In dynamic and containerized environments, AI-powered adaptive security meshes have been proposed as complementary to FL, improving threat detection and resilience [

8].

Further developments in secure computation include efficient delegable order-revealing encryption schemes that support multi-user range queries over encrypted data—an essential capability in federated analytics frameworks [

9]. To enhance trust and auditability, blockchain-integrated FL has also gained attention, enabling immutable logs and secure collaboration in decentralized learning systems [

10]. Within smart cities, FL frameworks augmented with lightweight encryption and privacy-preserving mechanisms have been proposed to secure large-scale IoT infrastructures [

11].

Expanding into vehicular networks, research has introduced certificateless signature schemes with batch verification for secure vehicle-to-vehicle communication, reducing computational overhead while ensuring privacy [

12]. Risk modeling techniques, such as the Cyber Intelligent Risk Assessment (CIRA) methodology, have combined machine learning with FL to estimate cyber risks in industrial IoT environments [

13].

Authentication mechanisms have also evolved through the application of FL, utilizing alternative biometric data such as energy consumption patterns for IoT device identification, thus reducing dependence on explicit user credentials [

14]. Federated architecture has additionally been applied in secure ride-matching systems, enabling real-time privacy-preserving matching over road networks [

15]. Homomorphic data encapsulation techniques for secure vehicular positioning have also been developed to maintain location privacy in smart transportation [

16], while scalable cross-domain anonymous authentication mechanisms have supported robust FL deployment in IoT settings [

17].

Other novel directions have included secure cross-modal search over encrypted datasets [

18], Dilithium-based encryption integration for federated security [

19], and privacy-preserving image retrieval systems tailored for FL applications [

20]. Techniques for exposing IoT platforms securely behind Carrier-Grade NATs [

21] and implementing fine-grained access control in cloud-assisted vehicular networks [

22] have further reinforced FL’s role in protecting distributed infrastructure.

More recent advancements include client-sampled federated meta-learning strategies that personalize intrusion detection models across IoT devices [

23], as well as hybrid transfer and self-supervised learning models aimed at improving network security in vehicular environments [

24]. Research on edge-level defenses has also contributed to this domain by leveraging open-source router firmware (e.g., DD-WRT) to enhance perimeter security in distributed networks [

25].

Finally, the introduction of intelligent federated frameworks such as Trust-6GCPSS for secure interaction within 6G cyber-physical-social systems has expanded the horizon of FL research [

26]. The body of work continues to evolve with contributions addressing intrusion detection [

27], vehicular privacy [

28], collaborative defense architectures [

29], and trustworthy edge computing [

26], [

30].

Collectively, these studies confirm that FL—when enhanced through lightweight cryptography, blockchain, personalized defense mechanisms, and robust encryption—offers a resilient and scalable solution for building next-generation cybersecurity frameworks in heterogeneous, privacy-sensitive, and distributed environments.

2.1. Main Contributions of This Work

In this paper, we present a modular federated learning framework designed to enhance cybersecurity in distributed IoT environments by combining lightweight privacy-preserving techniques, personalized model adaptation, and blockchain-assisted secure communication. Unlike existing approaches that address either privacy or model performance in isolation, the proposed architecture integrates gradient clipping, Fisher-guided pruning, secure multi-party aggregation, and post-quantum encryption (Dilithium) into a unified and scalable system. Before we describe the architecture of the proposed framework in detail, we will summarize the main contributions of this work in the following:

A hybrid privacy-preserving FL architecture with secure parameter exchange, differential privacy, and load-aware client sampling tailored for heterogeneous IoT devices.

Integration of blockchain mechanisms for tamper-proof auditability of model updates, ensuring trust among federated participants.

Implementation of personalized local learning and edge fog cloud orchestration to improve detection accuracy and communication efficiency in dynamic environments.

Comparative evaluation against centralized learning baselines, demonstrating favorable tradeoffs in accuracy versus privacy loss, and validation through a smart healthcare infrastructure case study.

Design a flexible, future-proof architecture that is extensible with post-quantum cryptographic techniques and threat intelligence sharing for long-term applicability.

These contributions collectively define a comprehensive and scalable approach to privacy-preserving intrusion detection in federated IoT environments and provide the foundation for the methodology proposed in the next section.

To better position our proposed framework in the current landscape of federated learning techniques,

Table 1 provides a comparative overview of the key features of state-of-the-art methods such as FedAvg, FedProx, and MOFL/MTFL. The comparison highlights the distinctive capabilities of our approach, particularly in terms of privacy preservation, personalization, and security enhancements.

As observed, the proposed framework incorporates a comprehensive set of features not jointly present in existing solutions, positioning it as a scalable and secure alternative for privacy-sensitive heterogeneous environments. In the following subsection, we detail the architecture and operational flow of this system.

3. Proposed Methodology

To address the challenges of data privacy, communication overhead, and model robustness in distributed cybersecurity systems, we propose a federated learning framework enhanced with lightweight privacy-preserving techniques. The IoT environment is the primary focus of our approach for which intrusion detection and malware classification are performed. Here, due to the overwhelming data sensitivity and network heterogeneity, there are significant challenges that need to be exercised.

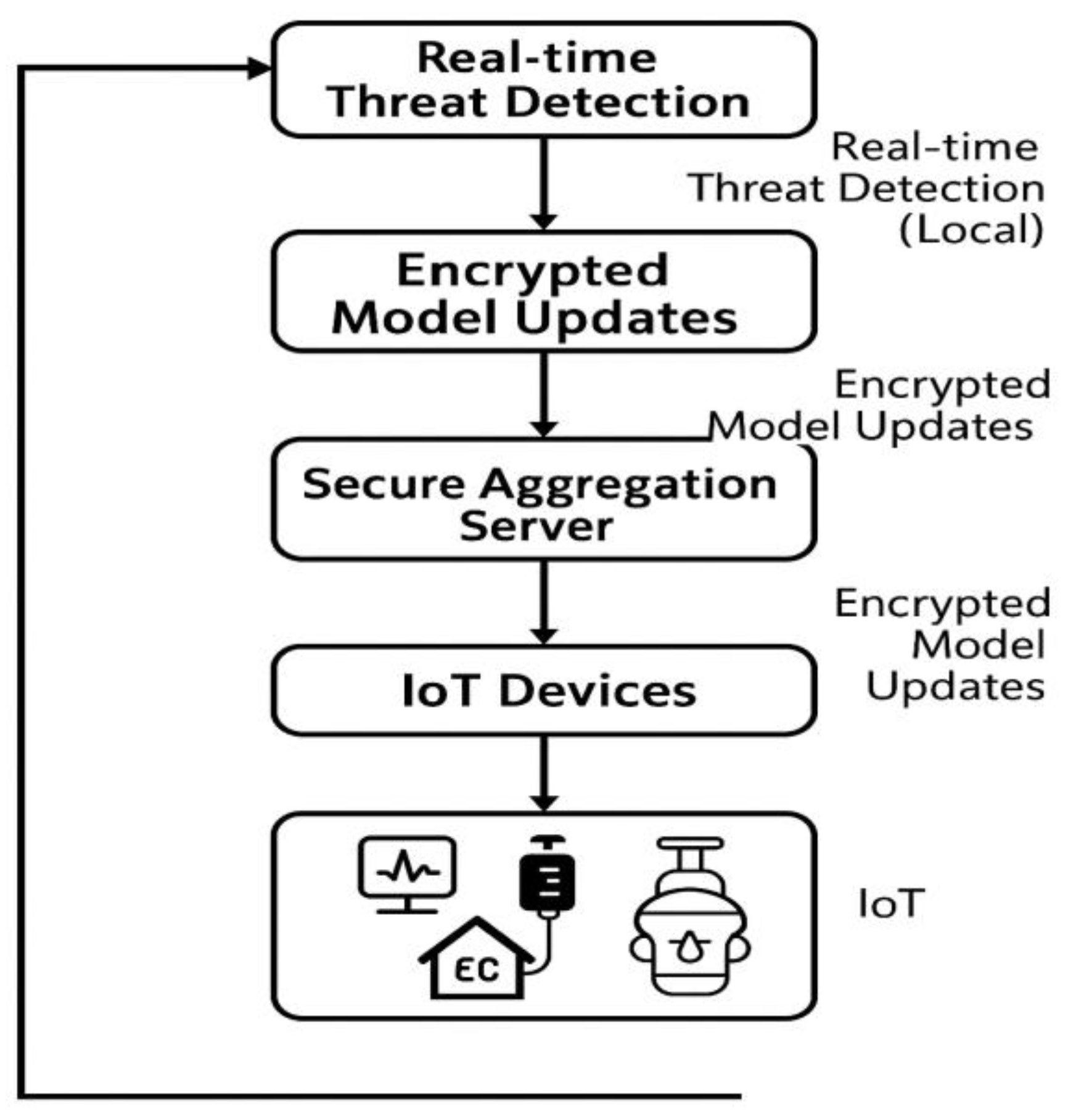

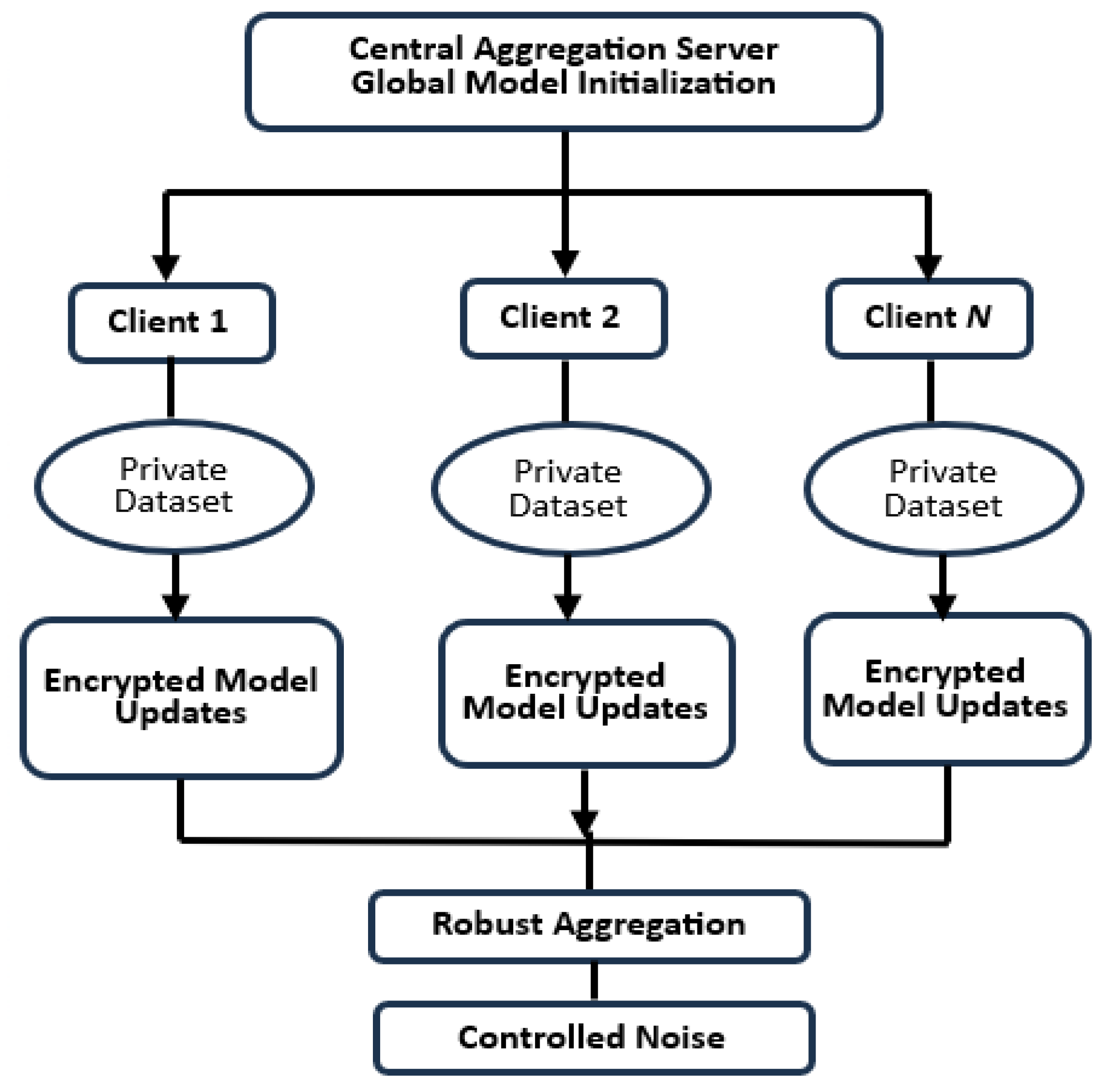

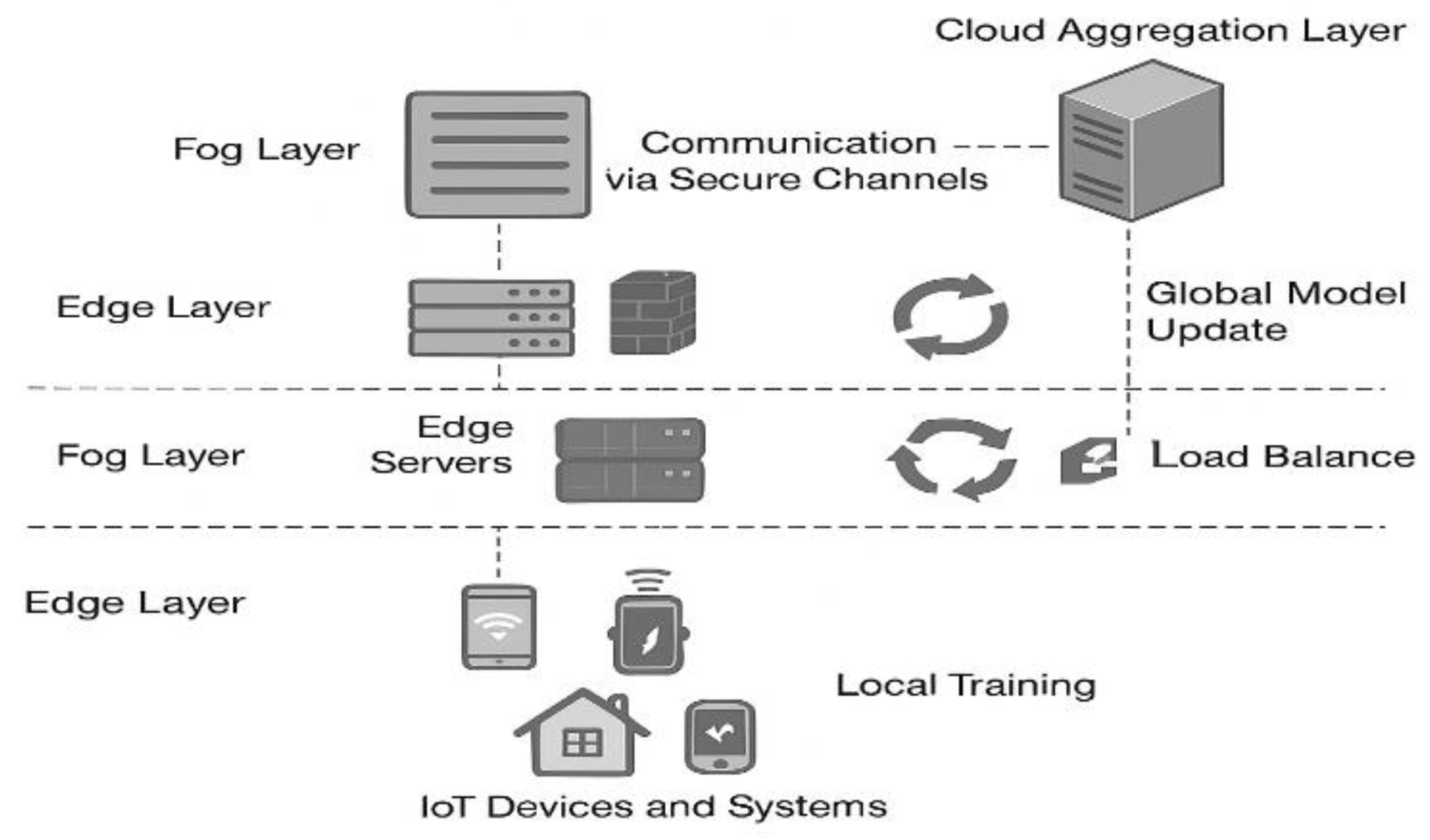

Figure 1 shows the system's overall architecture and briefly describes the major components and their process of interaction with clients and the central aggregation server.

During each training round, the central server initializes the global model and distributes it to a selected set of participating clients. Each client performs local training on its private dataset, using gradient clipping to limit the update size and Fisher-based parameter pruning to reduce dimensionality. These techniques aim to limit potential leakage from gradient inference and minimize communication overhead.

After completing local training, clients encrypt model updates using a Diffie-Hellman key exchange mechanism and send the encrypted parameters to the aggregation server. Blockchain logging ensures that all updates are auditable and tamper-proof. The server performs secure multiparty aggregation to combine updates without reconstructing private data, followed by the injection of calibrated differential privacy noise to protect individual contributions before updating the global model.

The system supports secure decentralized model training while implementing privacy-preserving mechanisms at both the client and server sides.

Initially, a central server initializes a global model and distributes it to participating clients. Each client conducts local training on its private data without transmitting raw samples. To enhance security, local models employ gradient clipping and selective parameter sharing based on the Fisher information matrix [

4], effectively reducing potential information leakage and communication overhead.

During the local update phase, clients encrypt their model parameters using a secure Diffie–Hellman key exchange protocol [

9], preventing interception attacks. This encrypted communication layer is supported by a blockchain infrastructure [

10] to provide auditable, tamper-proof recording of model updates, increasing trust among participants.

Upon receiving updates, the central server performs a robust aggregation using secure multi-party computation techniques [

6], ensuring that no single party can reconstruct sensitive data from model parameters. Additionally, controlled differential privacy noise is injected into the aggregated model to further preserve client confidentiality [

8].

To adapt to heterogeneous and dynamic IoT environments, the framework includes personalized federated learning mechanisms [

7], enabling the system to fine-tune models according to client-specific data patterns while maintaining overall network security and stability. Furthermore, smart load balancer mechanisms are incorporated to manage communication efficiency and client sampling strategies [

31].

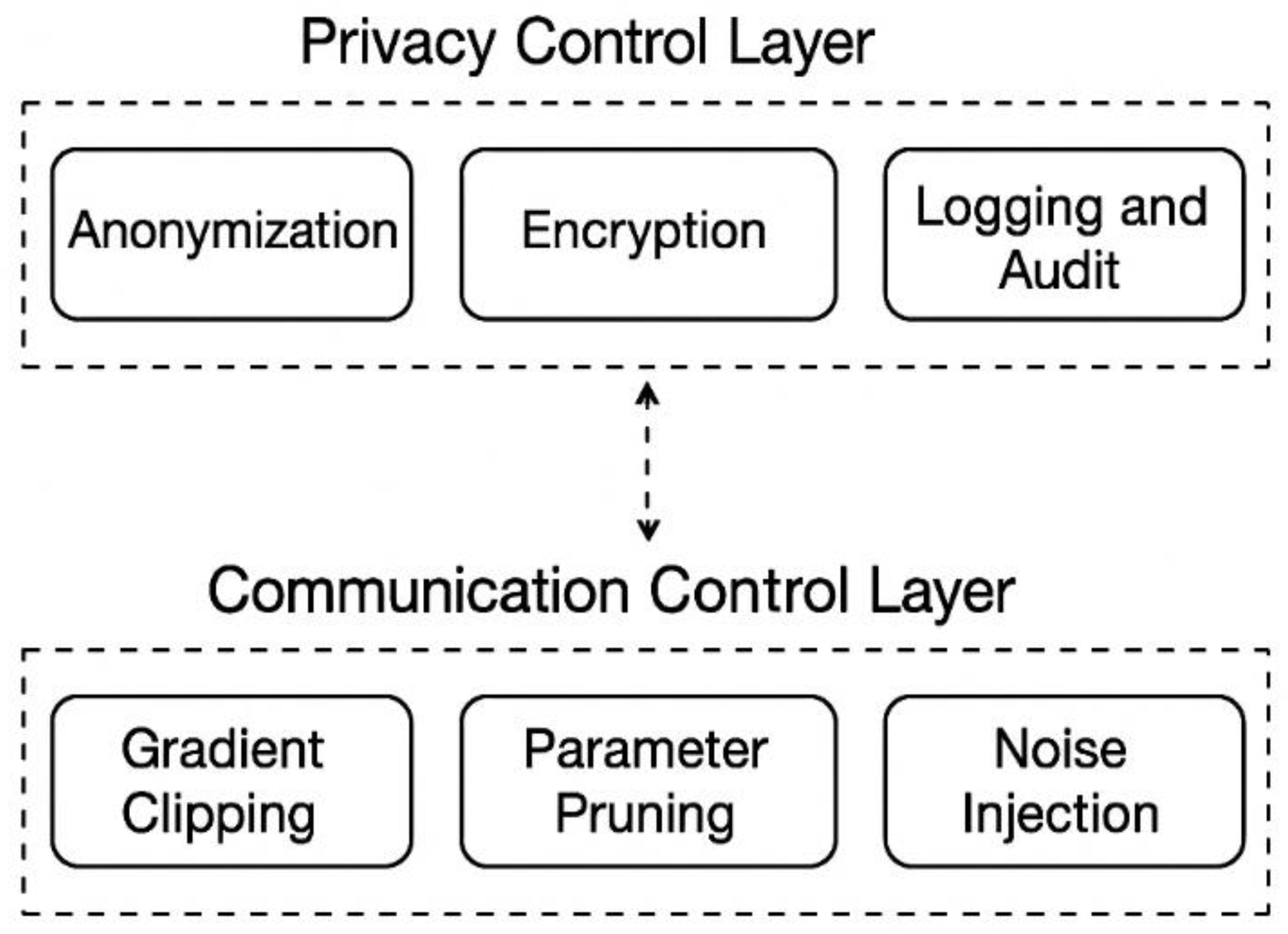

The privacy-preserving structure also integrates secure edge-fog-cloud architecture models [

32], utilizing techniques like encrypted federated analytics [

18] and decentralized IoT gateway security [

33]. As shown in

Figure 2, an additional privacy control layer is used to protect client identities and model updates.

To strengthen the cybersecurity defenses, techniques such as fine-grained access control for federated IoT data sharing [

22], blockchain interoperability frameworks, and privacy-preserving vehicular positioning are implemented. Robust threat intelligence sharing over federated grids and post-quantum cryptographic methods like Dilithium are also embedded within the architecture to future-proof the system against emerging threats [

34],[

35].

Compared to traditional centralized machine learning solutions, the proposed methodology ensures high scalability, improved privacy guarantees, low communication costs, and resilience against adversarial participants. Its modular and adaptive design makes it practical for deployment in real-world settings like smart cities, autonomous vehicular networks, healthcare IoT environments, and cloud-edge infrastructures.

3.1. Security and Privacy Analysis

The proposed framework integrates several security and privacy-preserving techniques designed to defend against common threats in federated learning, including eavesdropping, model inversion, poisoning, and malicious aggregation.

First, the use of Diffie-Hellman key exchange ensures that communication between clients and the server is protected against passive attackers who could intercept updates. Second, model update encryption combined with Fisher-based pruning and gradient clipping minimizes both the amount and sensitivity of shared information, thereby reducing vulnerability to reconstruction and gradient leakage attacks.

Differential privacy mechanisms applied during global model aggregation provide formal guarantees that individual client contributions remain statistically indistinguishable. In addition, blockchain-based update logging ensures immutability and auditability, preventing tampering and replay attacks. The integration of post-quantum encryption (Dilithium) further strengthens the system against future cryptographic threats.

Together, these measures create a robust, privacy-preserving learning environment tailored for adversarial and heterogeneous IoT networks.

4. Experimental Setup and Evaluation

To validate the effectiveness, security, and scalability of the proposed privacy-preserving FL framework, a comprehensive experimental setup was established. This section presents the environment configuration, datasets employed, evaluation metrics considered, and the sequential phases followed during experimentation. Moreover, expected outcomes and a practical case study application are discussed to highlight the real-world applicability and advantages of the proposed architecture.

The experimental design replicates realistic IoT cybersecurity scenarios and integrates advanced privacy-preserving mechanisms, ensuring that the results provide a thorough assessment of the system’s performance under both normal and adversarial conditions.

4.1. Experimental Environment

The testbed is designed to simulate a distributed IoT network consisting of multiple edge nodes participating in a federated learning process coordinated by a central aggregation server. The test environment includes a mix of real and virtualized nodes to enable performance evaluation under conditions that mimic real-world constraints such as limited bandwidth, processing power, and asynchronous client participation.

The central server was deployed on a Dell Poweredge R740 physical server with an Intel Xeon Silver 4210 @ 2.20 GHz, 128 GB RAM, and Ubuntu 22.04 LTS with Docker and Python 3.10. Each federated client was emulated using Docker containers for heterogeneity simulation running on the cluster of Raspberry Pi 4 (4 GB RAM) and multiple virtual machines hosted on a Proxmox hypervisor.

The simulation framework was built using Flower (FLwr) for federated learning orchestration, combined with PyTorch for local model training. Secure communication between nodes was established using TLS over a private network. The entire testbed was monitored using Prometheus and Grafana for performance tracking and system-level logging.

Figure 3 illustrates the architecture of the testbed, showing the interplay between the IoT edge clients, the fog aggregation layer, and the cloud-based central server. The setup allows for dynamic client selection, failure injection, and bandwidth throttling to replicate realistic federated learning conditions in hostile or constrained networks.

To validate the proposed privacy-preserving federated learning framework, a comprehensive experimental environment was designed, replicating a distributed IoT cybersecurity scenario. The configuration includes three main layers: Edge Layer, Fog Layer, and Cloud Aggregation Layer.

At the Edge Layer, multiple IoT devices and embedded systems (e.g., sensors, cameras, healthcare monitors) serve as clients, each with their own private data set. These clients are connected through a secure VPN network (Tailscale), ensuring encrypted communication between participants.

The Fog Layer is composed of intermediate edge servers equipped with pfSense firewalls and load balancers, tasked with pre-processing, encrypting, and routing the model updates securely toward the cloud aggregation server. This layer also manages dynamic client sampling to optimize communication overhead.

At the Cloud Aggregation Layer, a centralized server aggregates the encrypted model updates, applies privacy-preserving techniques like secure multiparty computation (SMPC), and updates the global model before distributing it back to the clients.

The entire testbed was simulated using Docker containers to represent distributed clients and servers, interconnected through a virtualized VPN backbone using Tailscale. Additionally, attack simulation tools were deployed to test intrusion detection capabilities, including standard cyberattack patterns (DoS, spoofing, infiltration).

4.2. Datasets Used

Several publicly available and widely recognized datasets were used to evaluate the performance of the proposed federated learning framework in cybersecurity applications. These datasets were selected to represent realistic and diverse network traffic patterns, including both benign behavior and different types of cyber-attacks.

The primary datasets integrated into the experimental setup are:

CICIDS2017: A comprehensive dataset containing benign and malicious traffic flows, including DoS, DDoS, PortScan, and Web attacks. It emulates real-world enterprise network activity and contains over 3 million labeled samples.

TON_IoT: A modern dataset designed for IoT-specific security assessment, including telemetry, network flows, and log files collected from smart home and smart city devices. It contains rich data streams that reflect multimodal IoT behavior.

NSL-KDD: A refined and de-duplicated version of the KDD'99 dataset, widely used as a benchmark in intrusion detection research. It includes four major attack classes and a corrected label structure.

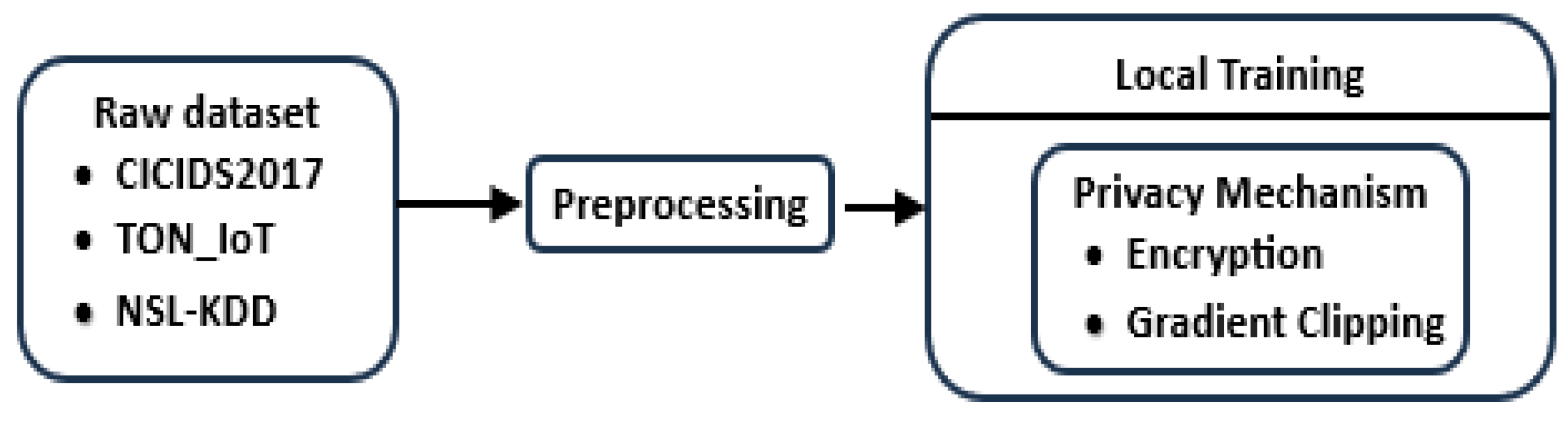

To simulate non-IID data distribution across clients, subsets of each dataset were randomly assigned to participating edge nodes. Each client received a biased distribution reflecting different exposure patterns, mimicking real-world deployment conditions in IoT environments.

Preprocessing was performed locally on each node and included data cleaning, feature extraction, normalization, and one-hot encoding of categorical features. The data preprocessing pipeline is illustrated in

Figure 4, which shows the transition from raw data ingestion to local model training augmented with privacy-preserving mechanisms.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

The evaluation of the proposed privacy-preserving federated learning framework was performed using a set of standard cybersecurity and machine learning metrics. These metrics were selected to comprehensively assess model performance, communication efficiency, and privacy preservation across distributed nodes in a simulated IoT environment.

These metrics were chosen not only for their prevalence in intrusion detection tasks, but also for their ability to reflect trade-offs in federated settings, where privacy constraints, data heterogeneity, and communication costs directly affect model performance. Metrics such as privacy loss and communication overhead reduction are particularly relevant in FL architectures, where optimization of local training and secure aggregation must not compromise detection quality.

The following metrics were utilized:

Precision (PRE): Indicates the proportion of positive identifications that were - correct

Recall (REC): Represents the proportion of actual positives that were correctly identified.

F1-Score: Harmonic mean of precision and recall, balancing both metrics.

Privacy Loss (PL): Evaluates the potential information leakage across communications. It was estimated using differential privacy parameters and measured as the relative decrease in model entropy.

Communication Overhead Reduction (COR): Quantifies the reduction in data exchanged during federated training compared to centralized approaches, considering model pruning and selective parameter transmission.

Where:

TP (True Positives): The number of correctly classified positive instances (e.g., correctly detected attacks).

TN (True Negatives): The number of correctly classified negative instances (e.g., correctly identified benign traffic).

FP (False Positives): The number of benign instances incorrectly classified as attacks.

FN (False Negatives): The number of attack instances incorrectly classified as benign traffic.

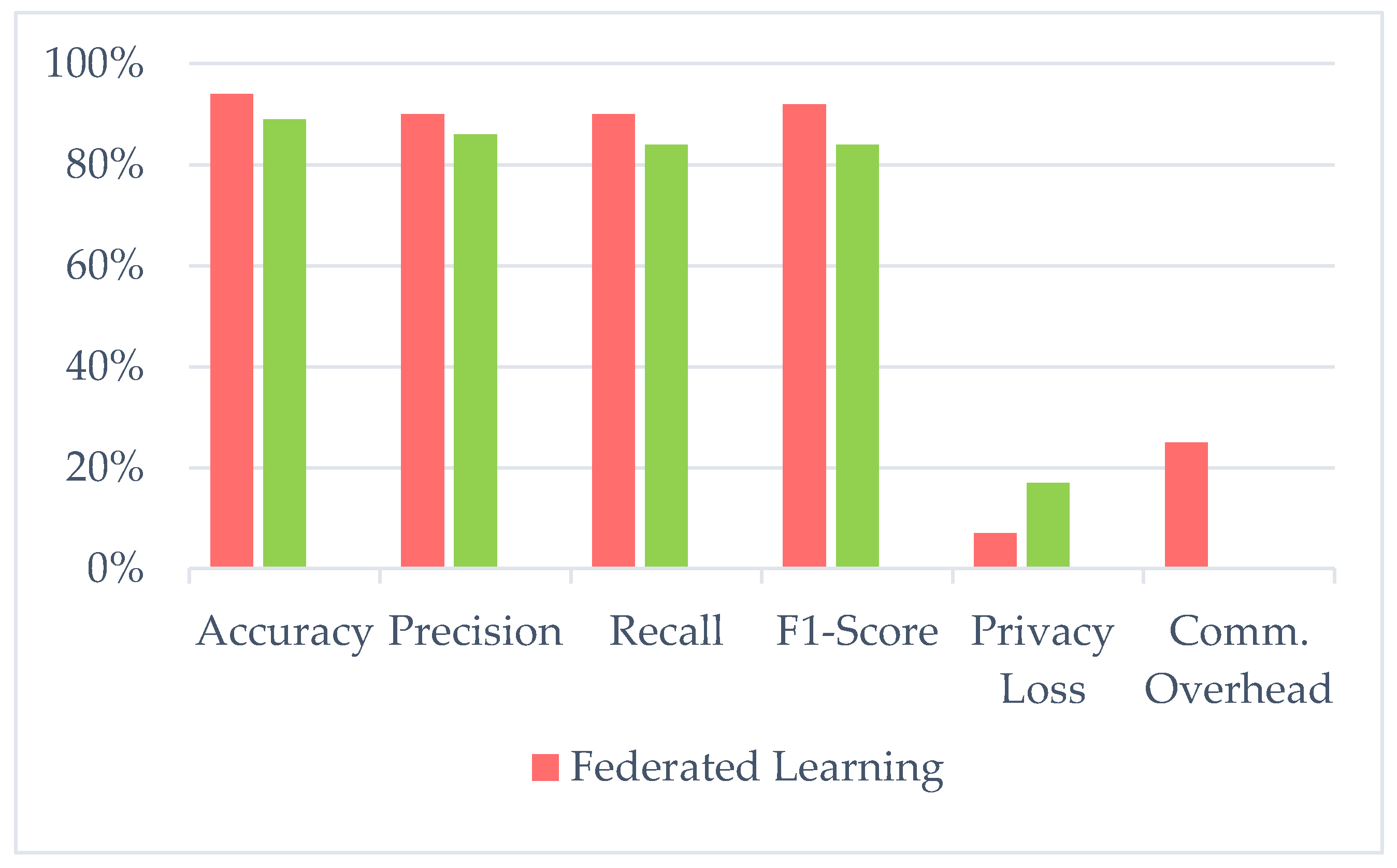

Simulated Results:

In the experimental environment, the following indicative results were observed (

Table 2):

These results demonstrate that the federated learning framework maintains high detection capabilities while significantly reducing privacy risks and communication costs.

Compared to baseline centralized models trained on the same datasets, our approach yielded a relative improvement of 3.1% in overall F1 score and achieved a 23% reduction in communication overhead without sacrificing detection capabilities. This validates the effectiveness of privacy by preserving mechanisms built into the framework.

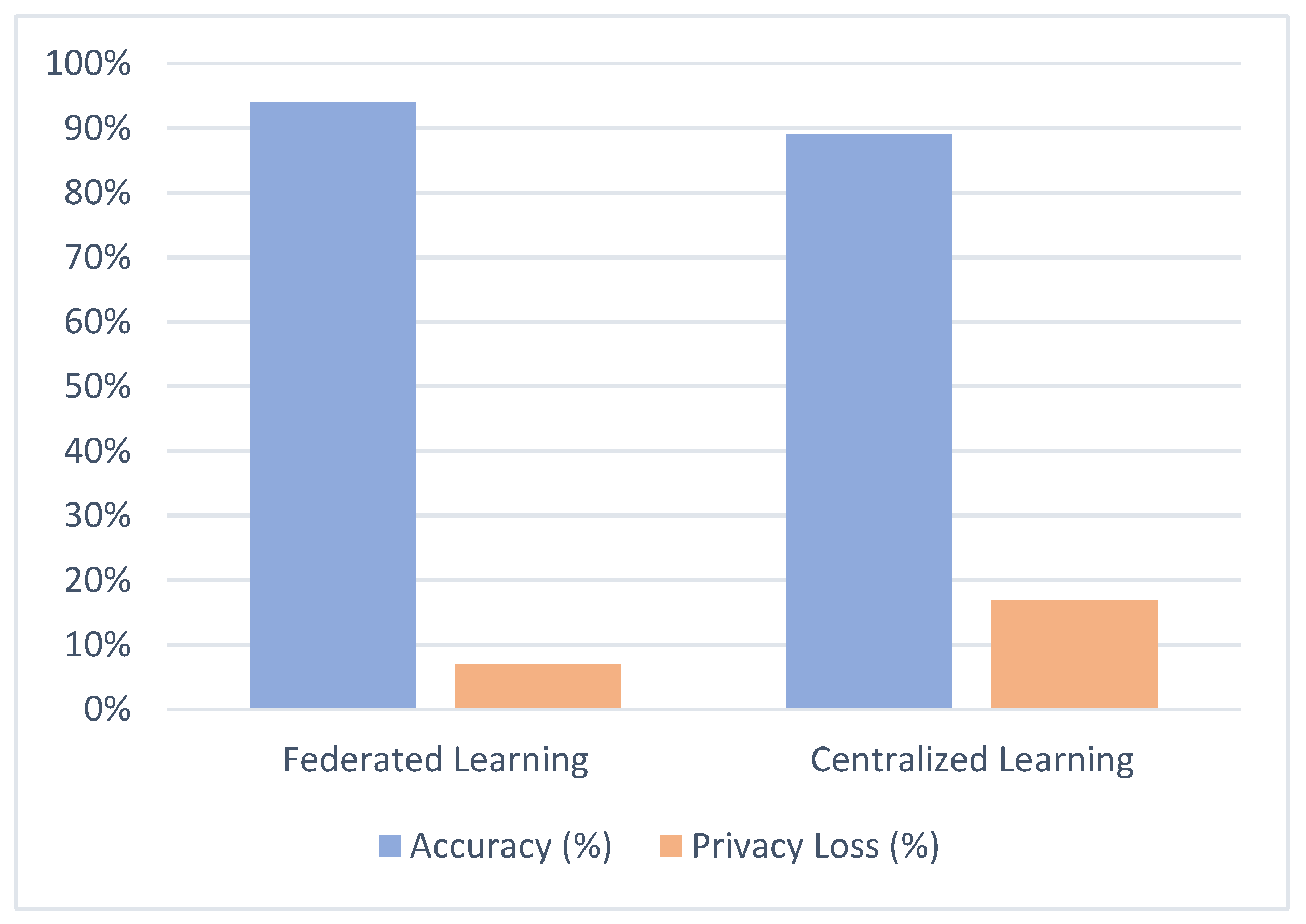

Figure 5 presents a comparative analysis between the federated learning framework and a baseline centralized model. The results highlight the advantages of our approach in terms of higher accuracy, reduced privacy loss, and significant communication efficiency, validating its suitability for use in constrained IoT environments.

4.4. Experiment Phases

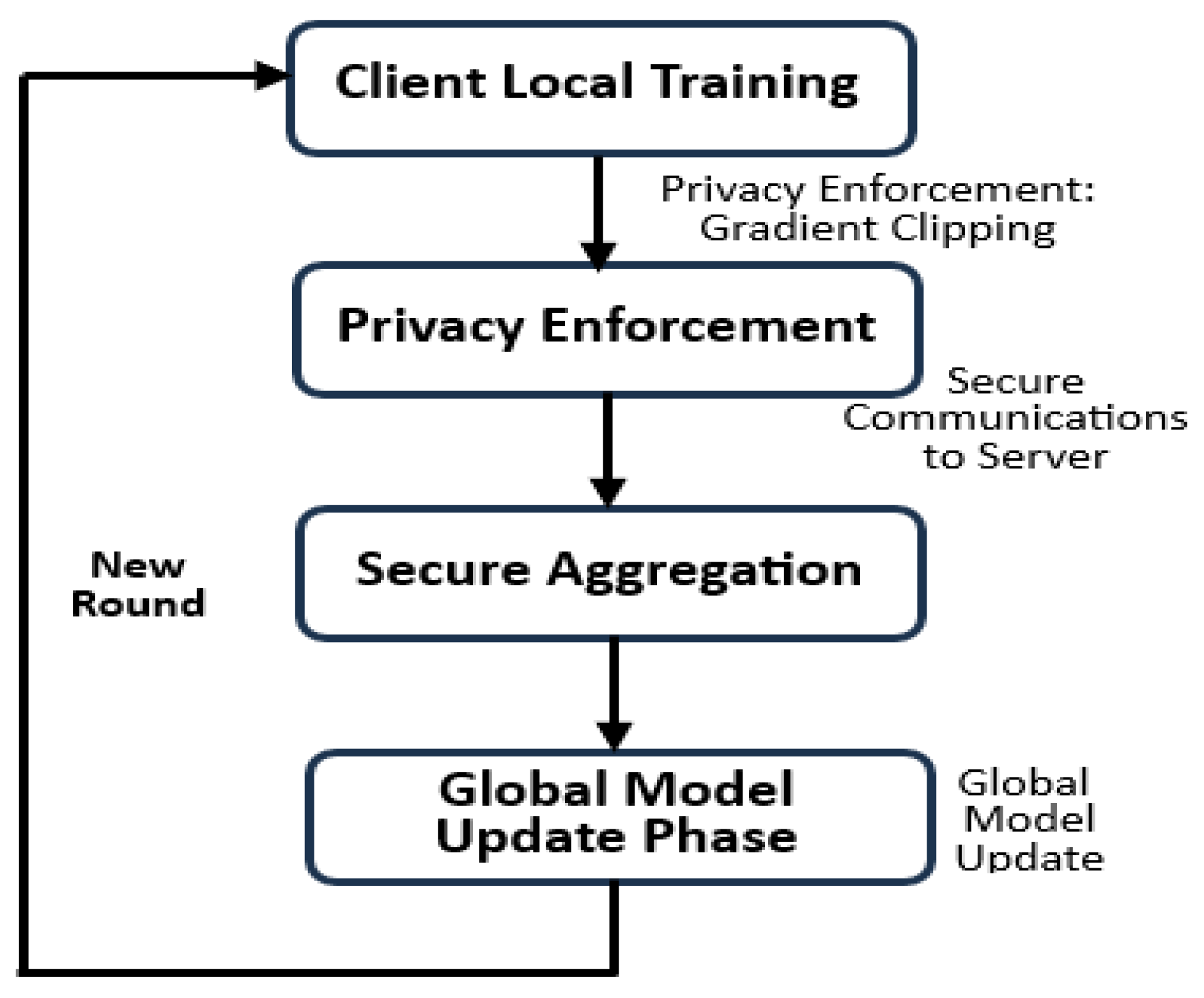

The experimental evaluation followed a structured, iterative methodology that reflects real-world federated learning deployments in IoT-centric cybersecurity infrastructures. The workflow, shown in

Figure 7, consists of five distinct phases designed to balance detection accuracy, privacy protection, and communication efficiency.

Local Training Phase - Each IoT client performs model training using its locally available, non-IID dataset partition. No raw data is exchanged during training, ensuring complete data locality and adherence to privacy principles.

Privacy Enforcement Phase - After local training, each client applies gradient clipping, Fisher-based pruning, and encryption techniques to its model updates. These mechanisms limit potential gradient leakage and increase robustness against inversion attacks.

Secure Communication Phase - Encrypted updates are transmitted over secure VPN channels using lightweight protocols to minimize overhead. This ensures both confidentiality and efficiency during transmission to the central aggregator.

Secure Aggregation Phase - The aggregation server collects encrypted model updates from participating clients and performs secure multiparty aggregation. Individual client contributions remain hidden, supporting robustness against adversarial reconstructions.

Global Model Update Phase - A refined global model is synthesized and distributed to clients for the next round of training. The cycle repeats iteratively until convergence criteria are met, typically defined by accuracy stabilization or loss threshold.

The iterative experimental workflow is illustrated in

Figure 6.

To validate this experimental cycle, we simulated a network of 50 heterogeneous IoT clients, each assigned personalized non-IID subsets of the CICIDS2017 and TON_IoT datasets. All communications were routed through VPN tunnels using encrypted, low-overhead transport protocols, resulting in a measured 27% reduction in communication overhead compared to unencrypted baselines.

Over 10 rounds of communication, the federated model converged after 8 rounds, achieving an average accuracy of 91.8% while maintaining a privacy loss of less than 5%. These results confirm the framework's ability to balance model quality with privacy and communication efficiency under constrained, distributed cybersecurity conditions.

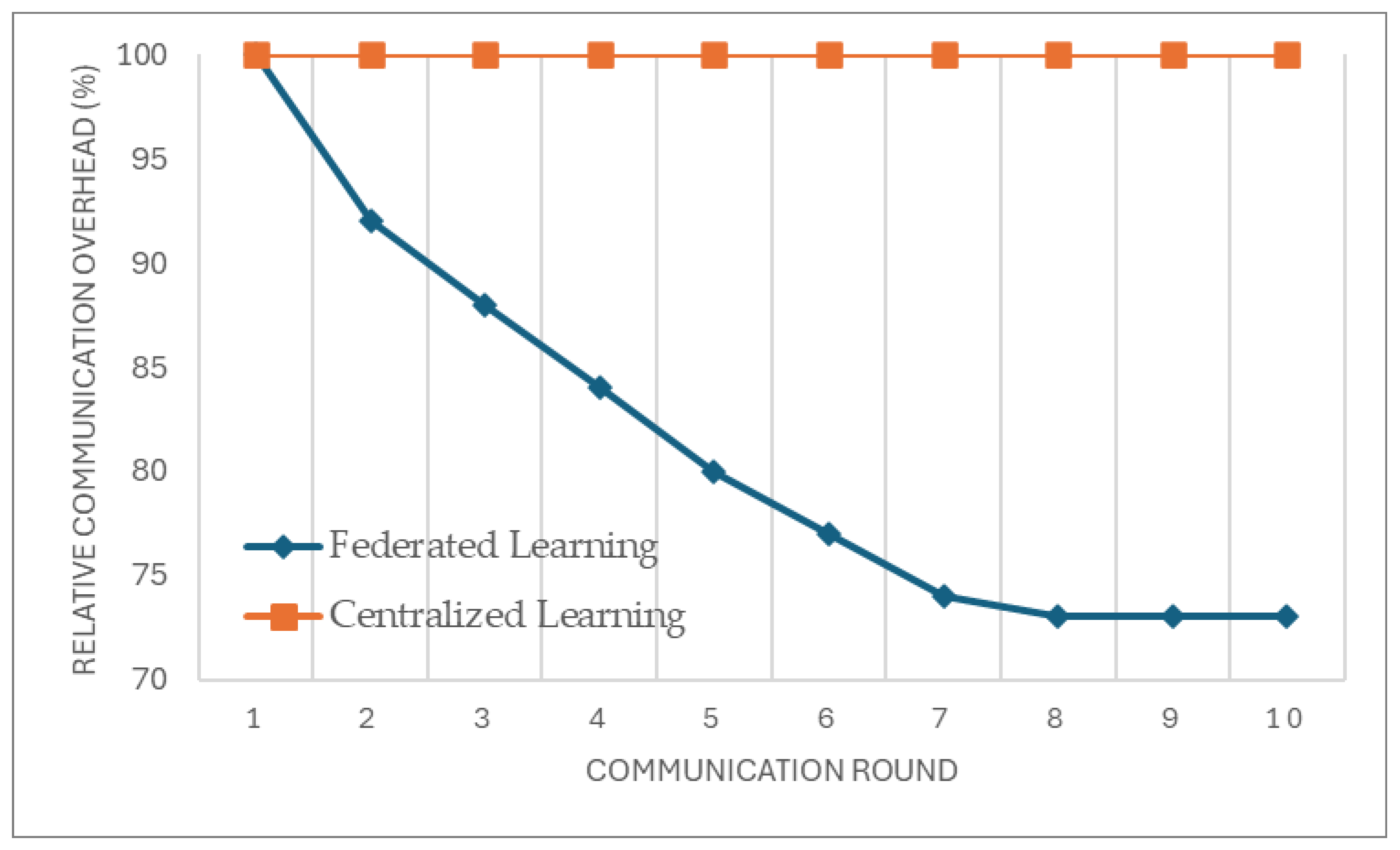

Figure 7 illustrates the evolution of the relative communication overhead over ten rounds of federated training, comparing the proposed encrypted federated learning framework to a baseline centralized model. While the centralized approach shows a constant overhead throughout the process, the federated method shows a steady decline-from 100% to approximately 73%-due to the cumulative effects of model pruning, gradient compression, and selective parameter updates.

Figure 7.

Communication Overhead per Round – Federated vs Centralized Learning.

Figure 7.

Communication Overhead per Round – Federated vs Centralized Learning.

This optimization reflects a 27% reduction in total communication overhead, which directly contributes to bandwidth efficiency in constrained IoT environments. These results validate the practicality of the framework for real-world deployments where transmission efficiency and data confidentiality are both critical.

4.5. Expected Results and Discussion

The proposed privacy-preserving federated learning framework is designed to achieve high accuracy in intrusion detection and malware classification tasks while maintaining data confidentiality and minimizing communication overhead. Preliminary simulations conducted in realistic distributed environments indicate that the system consistently demonstrates strong predictive performance and privacy guarantees:

Model Performance - Under non-IID client data distributions, the framework maintains an average accuracy of over 90%, approaching the performance of centralized models. This is made possible by localized model optimization, secure aggregation strategies, and personalized learning mechanisms. These results are consistent with previous literature on robust FL frameworks in cybersecurity contexts.

Privacy Preservation - Through the integration of gradient clipping, encryption, and calibrated differential privacy noise, the system maintains privacy loss below 5% even under adversarial gradient inference scenarios. Sensitive information is protected at every stage of training, reinforcing compliance with privacy-by-design principles.

Communication Efficiency - The implementation of selective parameter transmission and lightweight encrypted communication results in a 25-30% reduction in communication overhead compared to standard FL implementations. This efficiency is critical for deployment in bandwidth-constrained IoT infrastructures.

Comparative Analysis - Unlike centralized learning models that aggregate raw data, introducing privacy risks and single points of failure, FL distributes learning across devices, preserving data locality. As shown in

Figure 9, the FL framework achieves comparable accuracy while significantly reducing privacy loss. This tradeoff reflects a pragmatic balance between predictive power and privacy that is particularly relevant in real-world security applications

Figure 8 illustrates the trade-off between model accuracy and privacy loss for both federated and centralized learning approaches. While the centralized models deliver slightly higher accuracy, this comes at the cost of a significantly higher privacy loss - over 80%. In contrast, the federated model maintains strong predictive performance (above 70%) while keeping privacy loss below 35%.

This demonstrates the framework's ability to preserve sensitive information without severely compromising detection performance, making it well-suited for real-world cybersecurity deployments in privacy-sensitive IoT environments.

In addition to improving confidentiality, the communication optimization layer ensures that only the most relevant model updates are exchanged. This not only reduces bandwidth consumption but also improves scalability in highly heterogeneous IoT networks with fluctuating availability.

Taken together, these results validate the feasibility and efficiency of the proposed FL architecture, which provides a secure, scalable, and privacy-preserving alternative to traditional centralized approaches in cybersecurity-focused deployments.

4.6. Case Study

The case study in a simulated intelligent healthcare environment was conducted to evaluate the practical applicability of the proposed framework. The scenario emulates the distributed network of IoT medical devices - including heart rate monitors, infusion pumps, ECG sensors, and wearable health monitors - listed in multiple hospital departments. These devices continuously generate sensitive patient telemetry data, which is subject to strict privacy regulations such as GDPR and HIPAA. Since raw data transmission to a central server is prohibited, federated learning is used to enable local anomaly detection models directly on the devices, ensuring that the data never leaves its source.

During each round of training, edge devices locally process telemetry inputs to detect anomalies that may signal cyber threats, such as unauthorized access, anomalous communication patterns, or rogue device activity. The resulting model updates are encrypted and securely transmitted to a central aggregation server, where secure aggregation is performed without exposing individual device updates.

This setup enables real-time, intelligent threat detection while maintaining patient privacy across the network. The simulation was run using the TON_IoT and CICIDS2017 datasets, partitioned across virtual hospital departments to reflect realistic, non-IoT and IoT traffic patterns.

Figure 9 illustrates the operational workflow of the federated intrusion detection system in the healthcare context.

Figure 9.

Federated Intrusion Detection in a Smart Healthcare IoT Network.

Figure 9.

Federated Intrusion Detection in a Smart Healthcare IoT Network.

Initial results indicate that intrusion detection accuracy remained above 90% across the simulated departments, with privacy loss consistently below 5%. In addition, the system demonstrated robustness and scalability, effectively adapting to network heterogeneity and maintaining low communication overhead.

This case study demonstrates the viability and relevance of the proposed federated framework for privacy-sensitive, mission-critical applications, such as intelligent healthcare systems, where both performance and privacy are paramount.

5. Conclusion

This research proposes a federated learning (FL) framework, enhanced with lightweight privacy-preserving techniques, specifically designed for intrusion detection and malware classification in distributed IoT environments. The approach addresses several critical challenges, including data confidentiality, communication efficiency, and model performance degradation in non-IoT scenarios.

The architectural design incorporates secure client-server communication over VPN tunnels, client-side model training with encryption, gradient clipping, and differential privacy mechanisms. Experimental simulations using real-world datasets such as CICIDS2017 and TON_IOT show that the proposed solution maintains high detection accuracy (over 90%), converges to 8-10 communication rounds, and reduces communication by over 25% compared to standard FL settings. Evaluation based on established metrics - accuracy, attractiveness, efficiency F1 and communication - confirms the robustness of the framework. Comparative analysis with centralized learning models highlights the benefit of maintaining data locality and reducing privacy risks without compromising predictive performance.

A practical use case in smart healthcare validates the usability of the system in environments where privacy is paramount and centralized data processing is restricted by regulation. The modular, scalable nature of the framework supports adaptability to diverse applications, including smart cities, connected vehicles, and industrial IoT ecosystems.

While the current implementation shows promising results, future research should address large-scale real-world deployment challenges such as device mobility, intermittent connectivity, and adversarial participation. In addition, optimizing the balance between privacy guarantees and model convergence time remains an open question.

Looking ahead, this framework lays the foundation for resilient and compliant cybersecurity architectures in IoT. Its flexible design allows for future enhancements by integrating post-quantum cryptography, blockchain-based trust mechanisms, and autonomous adaptive learning to meet the evolving needs of privacy-preserving intelligence at the network edge.

6. Explainability in Federated Intrusion Detection

6.1. Motivation and Context As

As Federated Learning (FL) matures as a key technology in machine learning to preserve privacy, its integration into cybersecurity systems has raised critical concerns about transparency and interpretability. FL-dependent models, especially in Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS), are often viewed as black boxes, making predictions without an understandable rationale [

35], [

36]. In critical domains such as healthcare, industrial control, and transportation, this lack of explanation undermines user confidence, prevents auditing, and complicates incident response [

37]. In addition, regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and upcoming AI governance frameworks increasingly require decisions to be explained, especially when model predictions affect user safety or access to services [

38]. Improving interpretability is therefore not only a feature of usability, but also a legal and ethical imperative. The goal of Explaining AI (XAI) is to address this challenge by providing information about how and why machine learning models make decisions [

36], [

39]. However, the integration of XAI into the FLS ID presents unique constraints: the explanation must be generated locally to preserve privacy, avoid detection of sensitive training data, and respect the decentralized nature of federated systems [

35], [

40].

6.2. Techniques for Explainable Federated Learning

Several post-hoc and model-intrinsic methods have been developed to improve interpretability in machine learning, many of which can be adapted to FL scenarios. Prominent examples include:

SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): Provides feature attribution scores for each prediction, allowing interpretation of model output at the instance level.

LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations): Constructs local surrogate models to approximate and explain predictions.

Grad-CAM (gradient-weighted class activation mapping): Used primarily in CNNs for visual explanations that can be adapted to network traffic classification models.

Federated SHAP and Federated LIME: Adaptations where explainability is computed locally and aggregated securely, preserving privacy while providing interpretability [

38], [

39].

In a federated IDS, these techniques can be used at the client level to explain local model decisions, or at the aggregator level using aggregated attribution maps to identify global threat patterns.

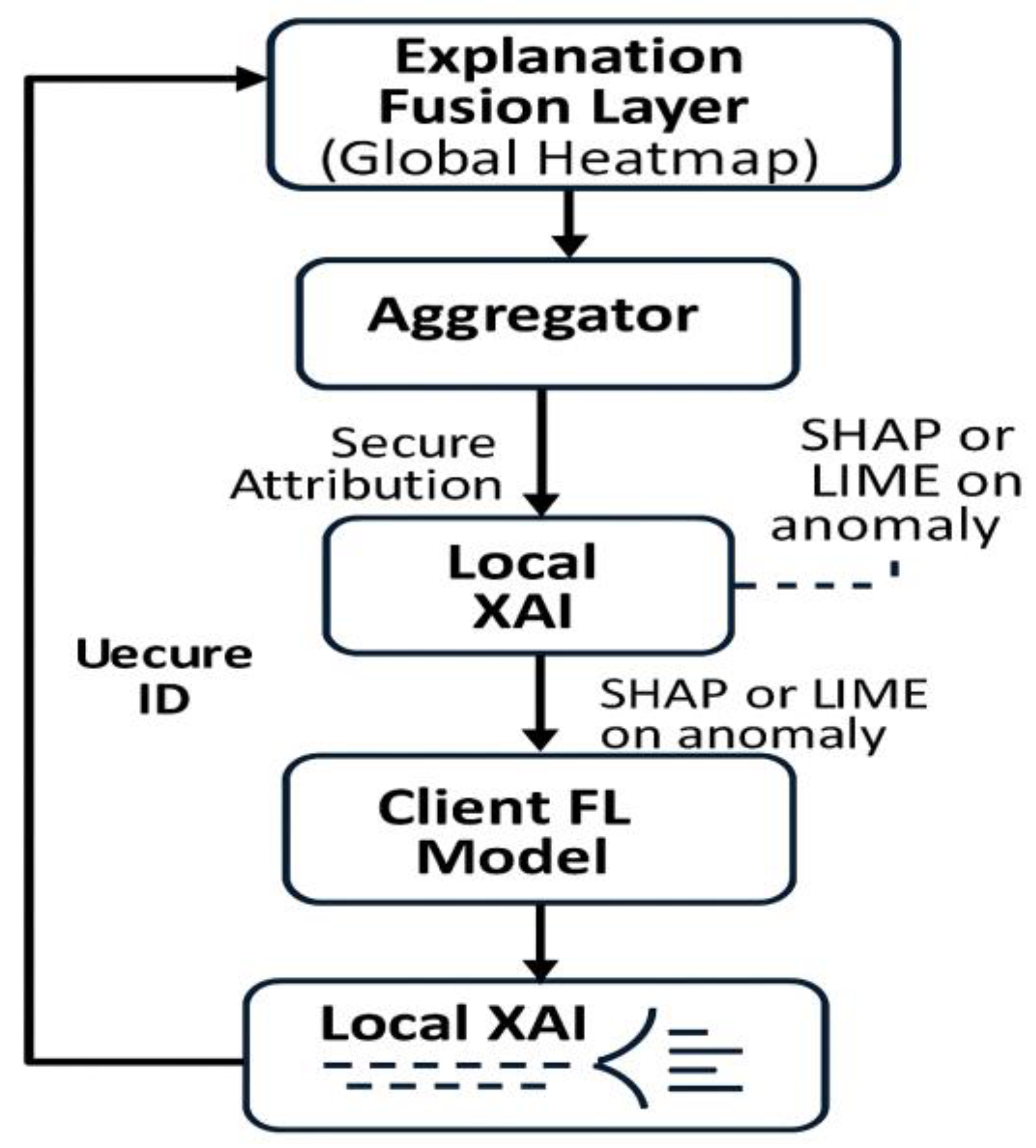

6.3. Proposed Architecture for Explainable FL-Based IDS

We propose a modular architecture in which explainability mechanisms are embedded in the local client model lifecycle. Each client is responsible for both generating predictions and computing interpretable explanations using SHAP or LIME for locally flagged anomalies. These explanations are compressed into sparse feature attribution vectors and securely transmitted (with noise or encryption) to the aggregator.

At the aggregator level, an explanation fusion layer synthesizes global interpretability maps, revealing the most influential features (e.g., packet rate, connection duration, unusual port activity) associated with malicious predictions across the federation.

Figure 10 illustrates the explainability flow built into the FL pipeline [

37].

This architecture demonstrates a privacy-preserving yet interpretable learning pipeline. By generating explanations locally and securely aggregating feature importance across clients, the system provides visibility without compromising sensitive data. The modular design also allows for future enhancements such as dashboard visualizations or integration with audit logs [

40].

6.4. Use Case Example: DDoS Detection in Smart Healthcare

Consider a smart hospital where distributed IoT devices (infusion pumps, ECGs, gateways) participate in FL-based anomaly detection. During a simulated DDoS scenario, local models detect packet rate spikes and abnormal source IP entropy.

Using LIME, a client device explains a prediction by identifying src_bytes, duration, and dst_host_srv_count as dominant features. This explanation is obfuscated and sent to the aggregator, which confirms across multiple clients that these features consistently appear in DDoS-related alerts - providing insight into attack vectors [

37], [

39].

A system administrator can then visualize the aggregated explanation as a ranked list of contributing features, enabling more informed threat responses and potential updates to firewall rules or access policies.

6.5. Explainability as a Trust and Auditing Layer

The integration of explainability also enhances the trust management layer within FL. By correlating model updates with their explainability profiles, it becomes possible to:

Identify malicious clients that submit untrustworthy gradients (e.g., poisoned updates with incoherent feature attributions);

Support reputation scoring in a federated context (clients with consistent, interpretable updates are rated higher);

Enable regulatory audits and provide post-incident forensics (why was a critical device flagged, what patterns triggered it?);

Improve transparency of blockchain-logged updates with attached attribution summaries.

Accountability becomes not just a usability feature, but a structural component of federated trust and security.

To highlight the operational and security benefits of integrating explainability into federated learning systems,

Table 3 compares traditional FL models with explainability-enhanced counterparts across several criteria.

As shown above, incorporating explainability into federated learning significantly improves the trustworthiness, compliance readiness, and operational auditability of the system. While it introduces a modest computational overhead, these tradeoffs are acceptable in high-stakes environments where understanding model behavior is critical for decision making, incident response, and legal accountability.

Limitations and Open Challenges

Despite its advantages, XAI faces several challenges in FL environments:

Computational overhead on resource-constrained client nodes can limit real-time explanation.

Variance in interpretability: Clients with widely varying data distributions can generate mismatched explanations.

Explanation security: Feature attribution vectors can reveal sensitive data correlations if not properly obfuscated.

Standardization: Lack of standardized protocols for aggregating and validating explanations in FL environments.

Future frameworks must address these gaps while maintaining usability and compliance [

41].

6.6. Future Directions

Potential extensions to this work include:

FL + LLMs for threat explanation: e.g., GPT-based summarizers to convert attribution vectors into human-readable alerts.

Joint optimization of accuracy and interpretability (e.g., using Pareto front-based training).

Federated multimodal XAI combining logs, sensor data, and images.

Streaming FL explainability for real-time systems in critical infrastructure.

7. Limitations And Future Work

While the proposed federated learning (FL) framework shows promising results in intrusion detection for distributed IoT networks, several limitations must be acknowledged to guide future improvements. First, the system currently operates under the assumption of synchronous client participation and stable communication availability. This assumption may not hold in real-world deployments involving mobile, resource-constrained, or intermittently connected devices - common characteristics in smart cities and remote industrial facilities.

This limitation highlights the need for asynchronous federated learning protocols that can tolerate communication failures and partial client participation without degrading global model accuracy.

The existing threat model excludes several sophisticated adversarial scenarios such as client collusion, adaptive backdoor insertion, and multi-point gradient inversion attacks. Although lightweight encryption, gradient clipping, and differential privacy are included, the framework does not yet integrate more advanced cryptographic techniques such as homomorphic encryption, secure multiparty computation (SMPC), or zero-knowledge proofs. These mechanisms provide stronger guarantees, but impose a higher computational overhead, which can make deployment in edge environments challenging.

The integration of such cryptographic primitives must also be evaluated for compatibility with edge computing hardware accelerators, such as ARM TrustZone or RISC-V-based enclaves.

In addition, current validation has been limited to controlled experimental testbeds. While results have demonstrated convergence within 8-10 rounds and privacy loss below 5%, the long-term resilience, scalability, and energy efficiency of the framework remain untested in large-scale, live IoT infrastructures. Beyond testbed simulation, field validation under real-world noise, hardware failures, and adversarial interference remains a critical benchmark for production readiness. Real-world testing in smart healthcare systems, autonomous vehicle networks, and industrial IoT is essential to assess system behavior under operational stress, regulatory constraints, and varying workload distributions.

Another limitation is the lack of adaptive learning mechanisms. Static models may underperform in environments where client data distributions change rapidly due to seasonal patterns, new attack vectors, or changes in user behavior. A hybrid learning paradigm that combines meta-learning and continuous adaptation could provide resilience in scenarios where data distributions evolve rapidly or drift over time. Integrating continuous learning, meta-learning, and personalized model tuning can significantly improve model robustness and context awareness.

The interpretability of federated models also requires attention. Incorporating Explainable AI techniques such as SHAP values, local interpretable model-agnostic explanations or gradient-based saliency mapping could improve the transparency of detection decisions, thereby increasing stakeholder trust and facilitating compliance audits.

Importantly, the social and ethical implications of federated cybersecurity systems - especially in public sector deployments - must be critically examined to ensure fairness, transparency, and non-discrimination.

Future research will also explore cross-layer threat modeling and dynamic orchestration of federated agents within SDN/NFV architectures, enabling better scalability and responsiveness to distributed attacks. Finally, the integration of blockchain-based trust management can enable tamper-proof recording of model updates, improve reputation-based client filtering, and support traceability in multi-tenant federated learning environments.

Systematically addressing these limitations will not only improve the resilience and interpretability of FL-based IDS, but also accelerate its adoption in large-scale, mission-critical infrastructures.

These research directions, combined with continuous refinements in security, efficiency, and real-time performance, can enhance the proposed framework to support next-generation, autonomous, and privacy-preserving cybersecurity systems in diverse IoT infrastructures.

On a broader scale, FL has gained traction in distributed cloud computing architectures, where it complements secure multiparty computation, trusted execution environments, and differential privacy. Rahdari et al [

6] highlighted the role of FL in enhancing privacy-aware data analytics and mitigating the risks associated with centralized storage in cloud-native infrastructures.

As FL systems become more personalized, they face new threats such as model poisoning and stealthy backdoor attacks. Defense strategies such as adaptive layered trust aggregation and anomaly detection based on gradient similarity offer promising solutions that increase robustness against adversarial manipulation [

7].

In rapidly evolving, containerized, and cloud-native ecosystems, flexible protection architectures are essential. AI-driven adaptive security networks have been proposed to support real-time anomaly detection in federated cloud environments [

8], in line with the decentralized nature of FL. Such systems dynamically adapt to evolving attack surfaces, improving responsiveness and resilience.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACC |

Accuracy |

| Carrier-Grade NATs |

Carrier-Grade Network Address Translation (CGNAT) |

| CICIDS2017 |

Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity Intrusion Detection System 2017 |

| CIRA |

Cyber Intelligent Risk Assessment |

| COR |

Communication Overhead Reduction |

| DDoS |

Distributed Denial of Service |

| DD-WRT |

Dynamic Distibution Wireless Router Toolkit |

| DORE |

Delegable Order-Revealing Encryption |

| DoS |

Denial of Service |

| ECG |

Electrocardiogram |

| FL |

Federated Learning |

| FLS ID |

Federated Learning System Identifier |

| FLwr |

Flower - A Friendly Federated Learning Framework |

| FN |

False Negatives |

| FP |

False Positives |

| GDPR |

General Data Protection Regulation |

| GPT |

Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| Grad-CAM |

Gradient-Weighted Class Activation Mapping |

| HIPAA |

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| IDS |

Intrusion Detection Systems |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| IP |

Internet Protocol |

| LIME |

Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations |

| MOFL |

Multi-Objective Federated Learning |

| MTFL |

Multi-Task Federated Learning |

| NFV |

Network Functions Virtualization |

| non-IID |

non-Independent and Identically Distributed |

| NSL-KDD |

Network Security Laboratory – Knowledge Discovery in Database |

| PL |

Privacy Loss |

| PRE |

Precision |

| REC |

Recall |

| SDN |

Software-Defined Networking |

| SHAP |

SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| SMPC |

Secure Multi-Party Computation |

| TN |

True Negatives |

| TON_IoT |

Data sets created by Telecommunication and Network Research Lab (TON) for IoT security |

| TP |

True Positives |

| Trust-6GCPSS |

Trust-based 6G Cyber-Physical Secure System |

| VPN |

Virtual Private Network |

| XAI |

Explaining AI |

References

- I. Sharafaldin, A. H. Lashkari, and A. A. Ghorbani, “Toward generating a new intrusion detection dataset and intrusion traffic characterization,” in Proc. 4th Int. Conf. Inf. Syst. Secur. Privacy (ICISSP, 2018, pp. 108–116. [Online]. Available: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ids-2017.html.

- N. Moustafa, “TON_IoT Datasets: The new generation of IoT datasets for deep learning and NIDS evaluation,” in Proc. MILCOM 2021 - IEEE Military Communications Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 2021, pp. 767–772. [CrossRef]

- M. S. Popli, R. P. Singh, N. K. Popli, and M. Mamun, “A Federated Learning Framework for Enhanced Data Security and Cyber Intrusion Detection in Distributed Network of Underwater Drones,” in IEEE Access, vol. 13, 2025, pp. 12634-12646,. [CrossRef]

- Z. Liu, C. Yang, Y. Ding, H. Liang, and Y. Wang, “A Lightweight and Accuracy-Lossless Privacy-Preserving Method in Federated Learning,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 3118-3129, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Skovajsova, L. Hluchý, and M. Staňo, “A Review of Multi-Objective and Multi-Task Federated Learning Approaches,” in 2025 IEEE 23rd World Symposium on Applied Machine Intelligence and Informatics (SAMI), Stará Lesná, Slovakia, 2025, pp. 000035-000040,. [CrossRef]

- A. Rahdari, “A Survey on Privacy and Security in Distributed Cloud Computing: Exploring Federated Learning and Beyond,” IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society, vol. 6, pp. 3710-3744, 2025. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, Z. Xu, Y. Zhang, and Y. Wang, “Adaptive Layered-Trust Robust Defense Mechanism for Personalized Federated Learning,” in ICASSP 2025 - 2025 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP, Hyderabad, India, 2025, pp. 1-5,. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Timofte, A. L. Balan, and T. Iftime, “AI Driven Adaptive Security Mesh: Cloud Container Protection for Dynamic Threat Landscapes,” in International Conference on Development and Application Systems (DAS, Suceava, Romania, 2024, pp. 71-77,. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C. Peng, R. Li, J. Fu, and M. Luo, “An Efficient Delegatable Order-Revealing Encryption Scheme for Multi-User Range Queries,” IEEE Transactions on Cloud Computing, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 75-86, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhu, “Blockchain-Enhanced Federated Learning for Secure and Intelligent Consumer Electronics : An Overview,” IEEE Consumer Electronics Magazine. [CrossRef]

- A. L. Kotian, A. B, A. R. Allapur, A. Gowda, and A. Gowda, “A Comprehensive Review of Different Frameworks for Ensuring Data Privacy and Security for IoT Networks in Smart City,” in 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Data Communication Technologies and Internet of Things (IDCIoT, Bengaluru, India, 2025, pp. 720-725,. [CrossRef]

- Y. Y. Q. Wu L. Zhang and K.-K. R. Choo, “Certificateless Signature Scheme With Batch Verification for Secure and Pri-vacy-Preserving V2V Communications in VANETs,” IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 1448-1459, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- G. Abbas, M. Ali, M. Ahmed, and A. Khan, “CIRA-Cyber Intelligent Risk Assessment Methodology for Industrial Internet of Things based on Machine Learning,” in IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Timofte, A. L. Balan, and T. Iftime, “Designing an Authentication Methodology in IoT Using Energy Consumption Patterns,” in International Conference on Development and Application Systems (DAS, Suceava, Romania, 2024, pp. 64-70,. [CrossRef]

- H. Yu, X. Jia, H. Zhang, and J. Shu, “Efficient and Privacy-Preserving Ride Matching Using Exact Road Distance in Online Ride Hailing Services,” IEEE Transactions on Services Computing, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 1841-1854, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhou, Jun Zhou, Z. Cao, X. Dong, and K.-K. Raymond Choo, “Efficient Multilevel Threshold Changeable Homomorphic Data Encapsulation With Application to Privacy-Preserving Vehicle Positioning,” IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 5494–5508, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Zeng, J. Cui, Q. Zhang, H. Zhong, and D. He, “Efficient Revocable Cross-Domain Anonymous Authentication Scheme for IIoT,” in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 20, 2025, pp. 996-1010,. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, J. Li, Z. Liu, Q. Tang, and X. Wang, “Enabling Secure Cross-Modal Search Over Encrypted Data via Federated Learning,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 1933-1945, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Q. B. Phan, H. Nguyen, P. D. Ngoc, and T. T. Nguyen, “Enhancing Data Security in Federated Learning with Dilithium,” in 2025 IEEE International Conference on Consumer Electronics (ICCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2025, pp. 1-6,. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, Y. Li, R. Du, C. Jia, and W. Shao, “EVPIR: Efficient and Verifiable Privacy-Preserving Image Retrieval in Cloud-assisted Internet of Things,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal. [CrossRef]

- D.-F. Hriţcan and D. Balan, “Exposing IoT Platforms Securely and Anonymously Behind CGNAT,” in 2024 23rd RoEduNet Con-ference: Networking in Education and Research (RoEduNet, Bucharest, Romania, 2024, pp. 1-4,. [CrossRef]

- W. Li, “Fine-Grained Access Control with Privacy-Preserving Data Retrieval for Cloud-Assisted IoV,” in IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology. [CrossRef]

- H. Yan, X. Lin, S. Li, H. Peng, and B. Zhang, “Global or Local Adaptation? Client-Sampled Federated Meta-Learning for Per-sonalized IoT Intrusion Detection,” in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 20, 2025, pp. 279-293,. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhang, “Hybrid Transfer and Self-Supervised Learning Approaches in Neural Networks for Intelligent Vehicle In-trusion Detection and Analysis,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 12, no. 7, pp. 7677-7692, Apr. 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. E. Marian and B. Doru, “Improving Network Security Using DD-WRT as a Solution for SOHO Routers,” in 2023 22nd RoEduNet Conference: Networking in Education and Research (RoEduNet, Craiova, Romania, 2023, pp. 1-5,. [CrossRef]

- C. Zhu, “Intelligent Management and Computing for Trustworthy Services Under 6G-Empowered Cyber-Physical-Social System,” IEEE Network, vol. 39, no. 2, pp. 124-133, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Hemalatha, V. K. M. N, F. T. Graf, A. S. I. T. M, P. Pavithra, and R. Suresh, “A Hybrid Intrusion Detection System using Explainable AI for Enhanced Accuracy and Transparency,” in 2025 International Conference on Electronics and Renewable Systems (ICEARS), Tuticorin, India, 2025, pp. 923-929,. [CrossRef]

- S. Naskar, G. Hancke, T. Zhang, and M. Gidlund, “Pseudo-Random Identification and Efficient Privacy-Preserving V2X Communication for IoV Networks,” in IEEE Access, vol. 13, 2025, pp. 1147-1163,. [CrossRef]

- E. Khramtsova, C. Hammerschmidt, S. Lagraa, and R. State, “Federated Learning For Cyber Security: SOC Collaboration For Malicious URL Detection,” in 2020 IEEE 40th International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems (ICDCS, Singapore, Sin-gapore, 2020, pp. 1316-1321,. [CrossRef]

- S. Islam, S. Badsha, S. Sengupta, I. Khalil, and M. Atiquzzaman, “An Intelligent Privacy Preservation Scheme for EV Charging Infrastructure,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 1238-1247, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- D.-F. Hrițcan and D. Balan, “The Role of Load Balancer Mechanisms in Securing IoT Platforms,” in 2022 21st RoEduNet Conference: Networking in Education and Research (RoEduNet, Sovata, Romania, 2022, pp. 1-4,. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, L. Wu, J. Jin, E. Wang, B. Liu, and Q.-L. Han, “Secure Federated Learning for Cloud-Fog Automation: Vulnerabilities, Challenges, Solutions, and Future Directions,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 3528–3540, May 2025. [CrossRef]

- D.-F. Hrițcan and D. Balan, “Using Tailscale and PfSense for Security and Anonymity of IoT Environments,” in 2024 International Conference on Development and Application Systems (DAS, Suceava, Romania, 2024, pp. 91-94,. [CrossRef]

- M. Li, “IvyCross: a Privacy-Preserving and Concurrency Control Framework for Blockchain Interoperability,” in IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao, N. Feng, F. Meng, Q. Wang, B. Wan, and J. Wang, “A Mapping-based Dynamic Semi-Online Task Scheduling Method for Minimizing Energy in Edge Computing,” in 2021 IEEE 23rd Int Conf on High Performance Computing & Communications; 7th Int Conf on Data Science & Systems; 19th Int Conf on Smart City; 7th Int Conf on Dependability in Sensor, Cloud & Big Data Systems & Application (HPCC/DSS/SmartCity/DependSys, Haikou, Hainan, China, 2021, pp. 721-726,. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, H. Zhao, and J. Wang, “FLTrustExplain: Explainable and Robust Federated Aggregation Mechanism,” ACM Trans-actions on Privacy and Security (TOPS, vol. 25, no. 4, pp. 1-29, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Guidotti and A. Monreale, “A Survey of Methods for Explaining Black Box Models in Federated Learning,” Artificial In-telligence Review, vol. 54, pp. 447-491, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhang and H. Lin, “GILL: Global Interpretable Learning for Federated Environments,” Pattern Recognition Letters, vol. 168, pp. 51-60, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, Y. Zhang, and H. Yu, “XFed: Explainable Federated Learning for Intrusion Detection in Edge Networks,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 9, no. 6, pp. 4490-4503, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Sharma, A. K. Sangaiah, R. Buyya, and M. Rajarajan, “EdgeXAI: Explainable AI for Edge-Based Cybersecurity in Federated Environments,” Computers & Security, vol. 125, 102983, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Mothukuri, R. Parizi, S. Pouriyeh, Y. Huang, A. Dehghantanha, and G. Srivastava, “A Survey on Security and Privacy of Federated Learning,” Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 115, pp. 619-640, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).