1. Introduction

In the contemporary era, data has emerged as a pivotal element of production and a strategic asset across a spectrum of societal domains. It is regarded as the "new oil" of the 21st century. The accelerated development and extensive implementation of information technology have resulted in the generation and aggregation of vast quantities of data at an unprecedented rate. The comprehensive analysis and utilization of these data sets have not only facilitated the transformation of conventional industrial development models but have also markedly enhanced production efficiency, thereby providing robust support for the sustained growth of the economy and the improvement of people's lives. In the field of scientific research, the utilization of data-driven scientific discovery is becoming a dominant paradigm, alongside the traditional three. Scientists regard data as the core object and tool of research. By analyzing and modeling large-scale data, scientists can reveal the laws behind complex phenomena, thereby guiding and implementing various scientific research projects [

1]. To illustrate, the advancement of data acquisition, analysis, and processing capabilities has significantly facilitated the advancement of cutting-edge science in fields such as genomics, astronomy, and climate science. Data serves not only to validate existing theories but also to provide new avenues for developing new hypotheses and exploring previously uncharted territory [

2].

Concurrently, the pervasive application of data presents a multitude of challenges. The exponential growth in data volume has created a pressing need to develop effective methods for storing, processing, and analyzing these data, while also ensuring the privacy and security of the data. In light of these considerations, the implementation of the national big data strategy is not only intended to facilitate technological advancement but also to guarantee that data [

3], as a pivotal resource, can facilitate economic and social development through institutional innovation and policy guidance.

In the contemporary data-driven society, machine learning technology has been extensively employed across a range of domains, including healthcare, finance, and the Internet of Things. However, with the increasing prominence of data privacy protection and security issues, traditional centralized data collection and model training methods are facing significant challenges [

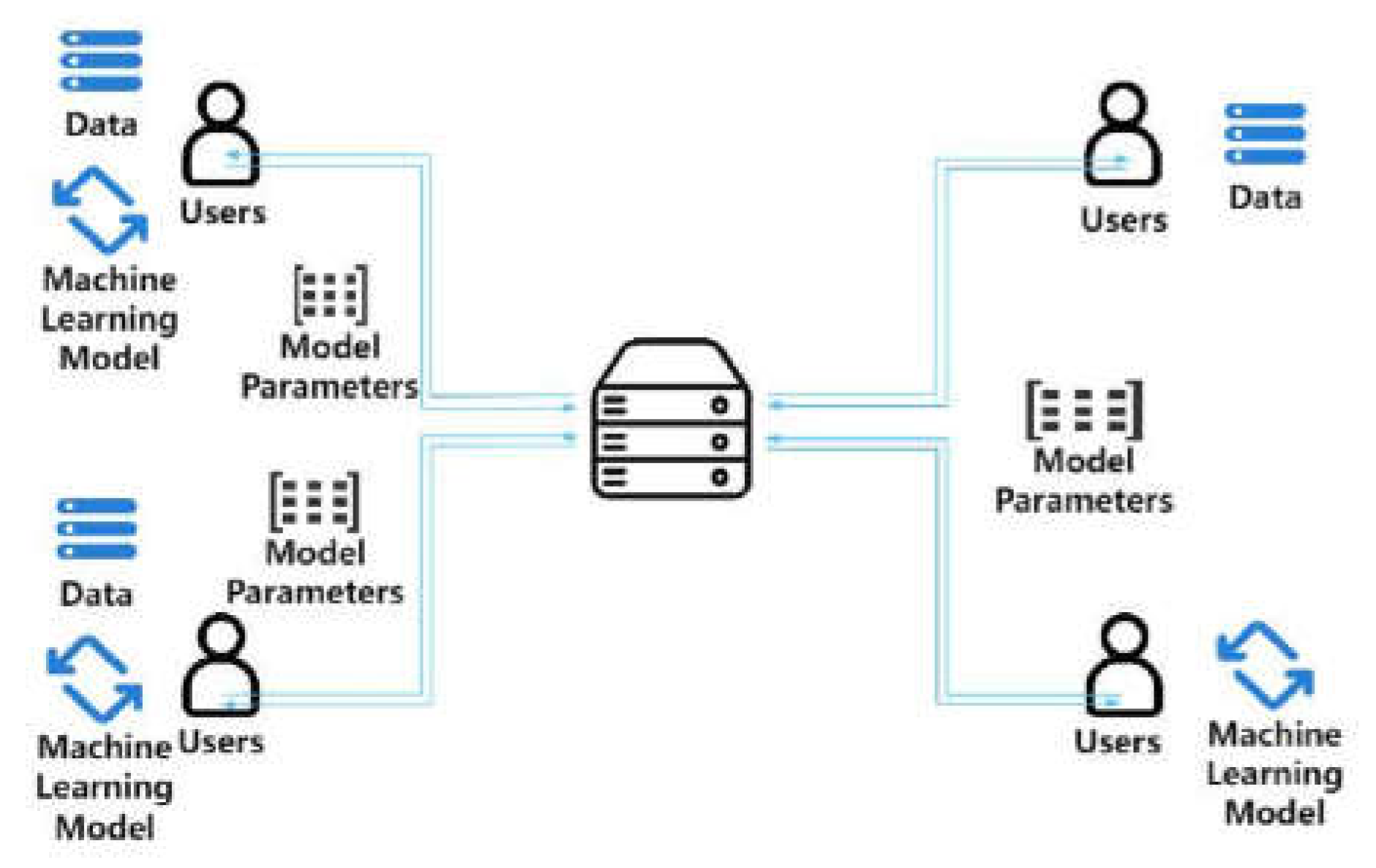

4]. To address this challenge, Federated Learning (FL), a novel distributed machine learning approach, offers a promising solution to data privacy concerns. Federated learning enables multiple participants to collaboratively train a global model without sharing their local data, thereby avoiding direct exposure to sensitive data.

Federated learning represents a novel approach to addressing the issue of data silos. It enables joint modeling between disparate data holders while circumventing the potential risks associated with data sharing, such as the compromise of privacy. In the conventional federated learning model, the data is retained at the local level, with each participant generating model parameters through local training and subsequently transmitting these parameters to a central server for aggregation. Nevertheless, this model presents two significant shortcomings.

First and foremost, the current approach is not sufficiently versatile. The models and algorithms utilized by each participant frequently necessitate intricate tuning and transformation to align with the specific requirements of local training, particularly in the context of disparate machine learning algorithms [

5]. This significantly constrains the extensive applicability of federated learning frameworks across diverse contexts. Secondly, the efficiency of the algorithm training is low. As the training process depends on regular communication between the central server and individual data nodes, each iteration necessitates a waiting period until all nodes have completed their training and uploaded the model parameters. This process not only requires a significant investment of time, particularly in the context of prolonged network communication delays, but is also constrained by the disparities in computing capabilities across individual nodes. In the event that the computing power of certain nodes is insufficient, the overall training process will be slowed down by these nodes, resulting in a reduction in the aggregation efficiency of the global model [

6].

A variety of strategies can be employed to enhance these processes. As an illustration, the deployment of differential privacy technology enables the processing of data at the local level for the purpose of safeguarding its confidentiality. Subsequently, the processed data can be transmitted to a central server in a single operation. This approach has the additional benefit of reducing the communication overhead associated with model training while circumventing the complexities inherent to local training [

7]. However, this approach also introduces novel challenges pertaining to the protection of data during transmission, necessitating more rigorous safeguards. The primary paradigms of traditional federated learning include horizontal federated learning and vertical federated learning (i.e., data is divided in the feature dimension, with each data holder possessing disparate features of the same sample) [

8]. However, it is not always the case that real-world data can be divided in such a neat manner. In many practical applications, data holders frequently possess only a subset of features for a given sample, rendering traditional horizontal or vertical divisions inapplicable. To illustrate, in the context of Internet of Things (IoT) devices, some devices may only be capable of collecting a subset of the feature data for a given user. This presents a challenge in aligning with the requirements of traditional federated learning frameworks, which typically assume a more uniform distribution of data across all participants.

While federated learning can provide a certain degree of data privacy, practical applications, particularly those involving distributed data across diverse institutions, devices, or users, have encountered significant challenges due to the issue of data heterogeneity. The heterogeneity of data from different participants, in terms of format, feature space, and distribution, presents a significant challenge in the construction of a unified and effective federated learning model in such environments. Furthermore, as an increasing number of regulations and policies impose stringent requirements for data privacy (such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in the European Union), the need to enhance data privacy protection in federated learning and prevent potential information leakage during model training and aggregation has also emerged as a pressing issue that requires immediate attention.

The majority of current research and applications concentrate on horizontally and vertically partitioned datasets. However, there is a paucity of joint modeling studies on heterogeneous data partitioning. In practice, the diversity among data holders and the incompleteness of datasets underscore the urgent need to develop federated learning algorithms that can handle heterogeneous data. Such algorithms must be capable of addressing structural imbalances in data and identifying an optimal balance between computational complexity, privacy protection, and communication costs. This not only enhances the applicability of federated learning but also facilitates its extensive deployment in heterogeneous data-rich contexts, including the Internet of Things and intelligent healthcare.

Differential privacy and homomorphic encryption are common privacy-preserving techniques in federated learning. However, existing methods often suffer from inefficiencies in dealing with heterogeneous data. By integrating these technologies into the FL framework, this study enables effective data privacy protection even in the case of uneven data distribution. At the same time, the combination of these technologies improves the computational efficiency of the model and the overall robustness of the system.

Centralized data processing methods are heavily constrained in traditional data collection and processing due to concerns over data privacy and security. For that reason, FL for Gau-M has the potential of a new paradigm shift that can be inspired out of its nature of heterogeneity across institutions or devices. But the current FL methods still suffer from inefficiency and limited flexibility in scenarios where data is heterogeneous. We propose a new framework to solve existing methods limitations on heterogeneous data applications with advanced privacy protection. Therefore, this paper proposes a novel framework designed to address the inefficiencies and challenges encountered in the application of FL to heterogeneous data scenarios, by incorporating advanced privacy protection mechanisms.

2. Related Work

Jakub et al. [

10] have previously highlighted that the objective of federated learning is to develop high-quality models from data distributed across a vast number of clients while maintaining the data locally. Jakub's proposed training approach entails each client independently computing the model's update parameters based on its local data, which are then conveyed to a central server. On the central server, the updated parameters from the individual clients are aggregated in order to calculate the new global model. In a previous study, Sharma et al. [

11] proposed a federated transfer learning algorithm that enables the sharing of model knowledge and facilitates knowledge transfer between different neural networks, while ensuring data privacy. In this approach, the knowledge of the source domain is transferred to the target domain through the construction of a cross-domain model, thereby enhancing the learning capacity of the target domain task. The essence of federated transfer learning lies in the integration of the strengths of both federated learning and transfer learning. This approach not only safeguards data from unauthorized access but also enhances the model's generalization capacity when there are discrepancies between the source and target domains.

In their study, Chromiak et al. [

12] put forth a data model for heterogeneous data integration that takes into account various forms of data partitioning, including horizontal, vertical, and hybrid partitioning scenarios. However, this model does not safeguard the privacy of data during the process of data integration, which may result in an increased risk of privacy violations in practical applications. While the model is effective in addressing the fusion of heterogeneous datasets, the absence of essential privacy protection mechanisms represents a significant limitation in scenarios where data privacy is a primary concern.

Madaan et al. [

13] conducted a further analysis of the necessity for data integration in the context of the Internet of Things (IoT) and identified a distinctive privacy leakage threat in this scenario. The data collected by IoT devices is often scattered and derived from a multitude of heterogeneous sources, increasing the risk of information leakage during integration, particularly in the absence of robust privacy protection mechanisms. The protection of data privacy in the context of the Internet of Things is not solely a matter of safeguarding personal information; it also entails ensuring the trustworthiness of devices and the security of the system as a whole. Consequently, the need for robust privacy protection is of paramount importance.

In order to address these challenges, Clifton et al. [

14] proposed a research topic on privacy-preserving data integration. This topic discussed how data fusion from multiple data sources could be achieved through third-party matching (Matching) and integration techniques without violating user privacy. The aim was to provide secure query results. The study demonstrates that the deployment of third-party privacy protection mechanisms can effectively mitigate the concerns of all parties involved in the process of data integration. By encrypting and anonymizing the data, third parties can securely match and integrate multiparty data without direct access to the original data.

In their seminal work, Kasiviswanathan et al. [

15] introduced the concept of Local Differential Privacy (LDP), a groundbreaking approach that eliminates the reliance on trusted third parties and enables users to locally perturb their data, thereby markedly enhancing privacy protection. By introducing noise directly into the data at the user level, local differential privacy provides a heightened level of privacy for each user, rendering it impossible for even the data collector or central server to recover the original data. This model is particularly advantageous in a decentralized data environment, as it reduces the necessity for a global trusted third party and expands the scope of privacy-preserving technologies.

On this basis, Wei et al. [

16] combined differential privacy with federated learning to propose an improved privacypreserving federated learning framework (FL). In this framework, each participant introduces differential privacy noise into the local training process, thereby rendering it challenging to disclose the sensitive information of the original data even if the locally generated model parameters are intercepted. Subsequently, the noise-disturbed local model parameters are uploaded to a central server for integration during the global aggregation phase. This approach demonstrably enhances the security of federated learning, guarantees the confidentiality of participants, and enhances the resilience of the model.

Yu et al. [

17] discussed the security of federated learning (FL) in horizontal and vertical data partitioning, particularly how the model poisoning attacks to be dealt with. In this study, the authors proposed the Rogue Device Detection (MDD) to detect and prevent the attack of rogue devices from interferingthe learning process. Anees et al. [

18] presented a vertical federated learning framework based on neural networks and improved its performance using server integration techniques. In vertical federated learning, different parties share data features rather than splitting data by sample dimensions as in horizontal federated learning. Our study focuses on how to coordinate heterogeneous actors, and how to optimize the complexity of the framework through an integrated server.

3. Methodologies

3.1. Differential Privacy

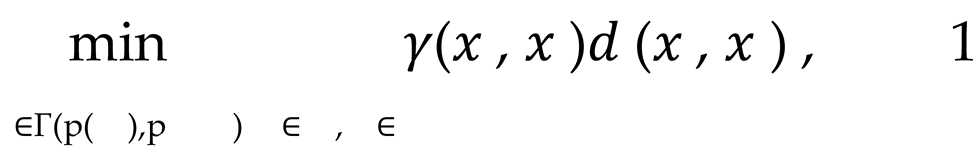

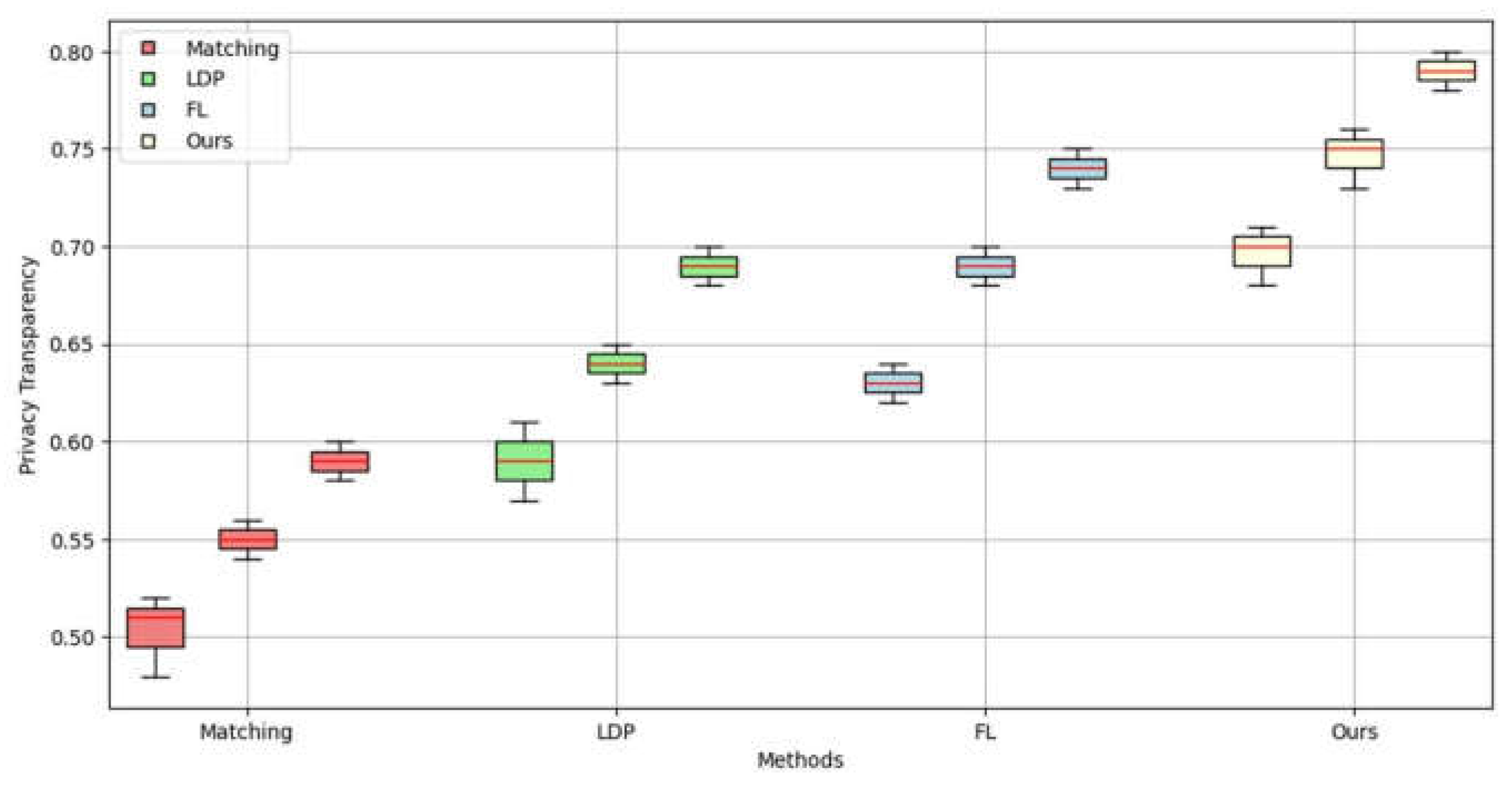

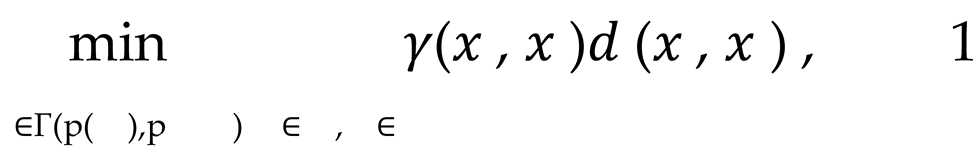

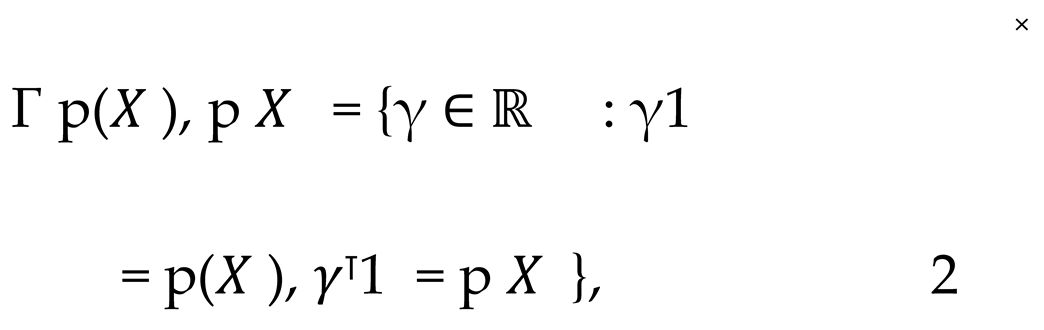

Initially, we assume that the distributions of datasets X and X , respectively, are p(X ) and p X , then aligning the features of these distributions directly may result in confusion regarding the features in the high-dimensional data. Therefore, we adopt an optimal transport (OT)-based approach to map data with different distributions into a common space, while considering preservation of local structure. Transmission problem can be represented by solving the following convex optimization problem, denoted as Equation 1.

where d(x , x ) represents a distance metric (for example, Euclidean distance) defined on the data feature space. γ(x , x ), on the other hand, denotes the mapping matrix, which describes the manner in which the features between X and X are aligned. Γ(p(X ), p X )represents a joint distribution set that satisfies the edge constraints.

By solving this optimal transmission problem, we can ascertain the optimal methodology for mapping the variables

X and

X to the common feature space

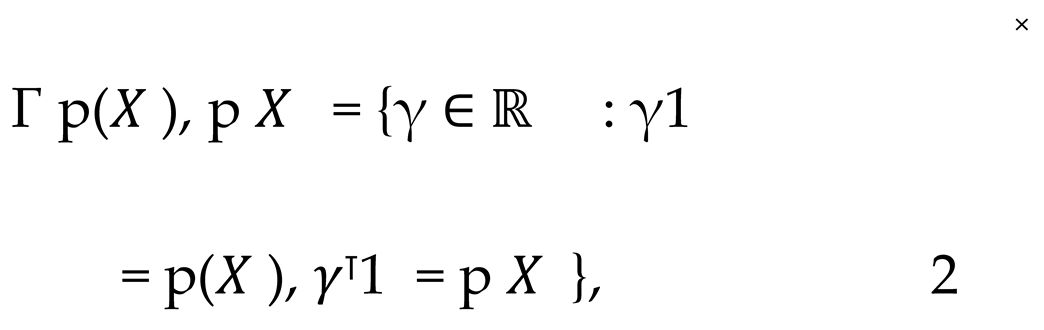

Z, thereby achieving the alignment of heterogeneous data. In order to solve this problem in an efficient manner, the optimal transmission method of entropy regularisation is employed. This rewrites the optimal transmission problem in Equation 2 as follows in Equation 3.

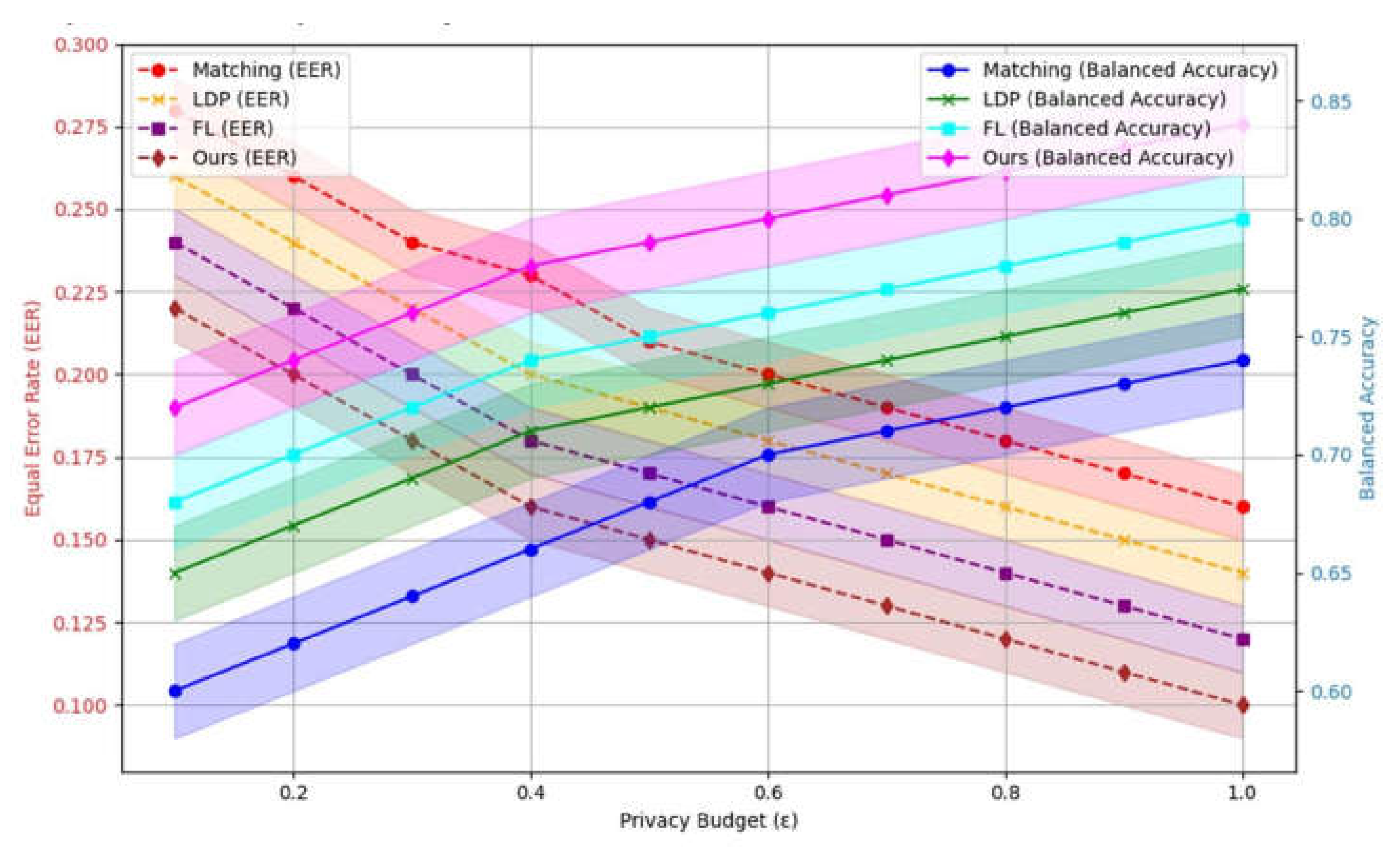

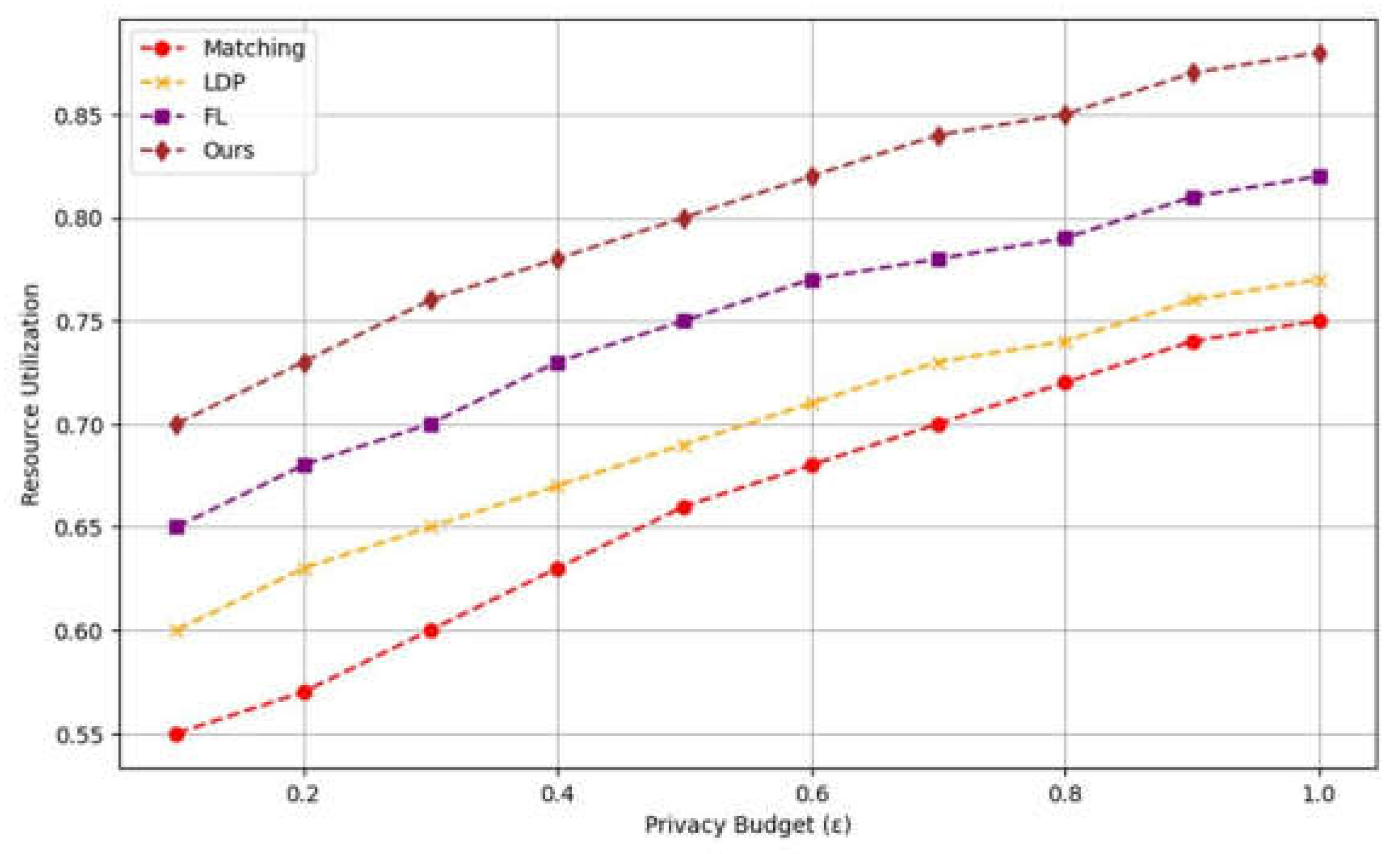

∈Γ(p( ),p ) , where the term H(γ) = − ∑ , γ(x , x )log γ(x , x ) represents the entropy regularisation, whereas ϵ controls the regularisation intensity. As the privacy budget increases, the amplitude of the noise decreases, improving the performance of the model. Conversely, when the privacy budget is small, the noise increases and the privacy protection increases, but the accuracy of the model decreases.

In order to further enhance the flexibility of feature alignment, we combine kernel methods in order to map the data into a high-dimensional Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Space (RKHS). Assuming that the feature map is ∅(∙), a suitable kernel function

k(

x,

y) may be selected, denoted as Equation 4.

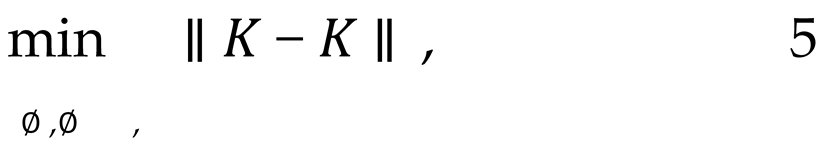

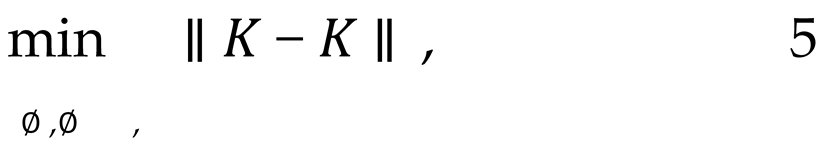

The kernel function allows us to define the corresponding kernel matrices, K and K , which represent the similarity of X and X in high-dimensional space. The optimal transport problem is generalized to the kernel space with the objective of achieving feature alignment in a more flexible feature space. The objective of the nuclear method is to minimize the distance between the two nuclear matrices, represented as Equation 5

where ∥∙∥ represents the Frobenius norm, which serves to align disparate datasets in the kernel space by minimizing the distance between them. This allows the features of each heterogeneous data source to be mapped to a common high-dimensional space, thereby achieving feature fusion.

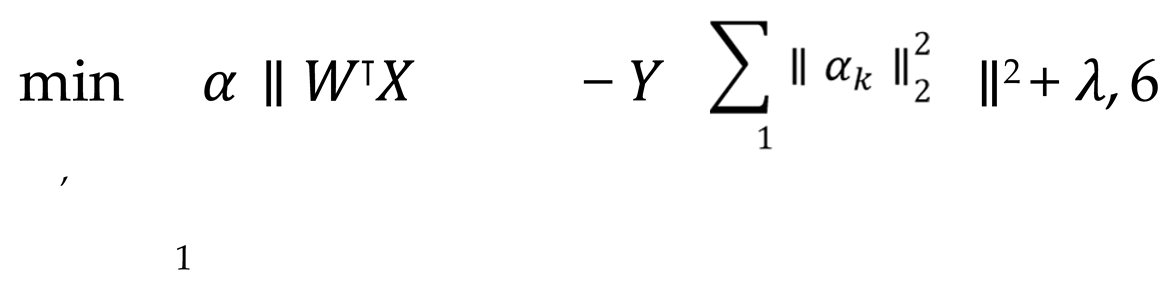

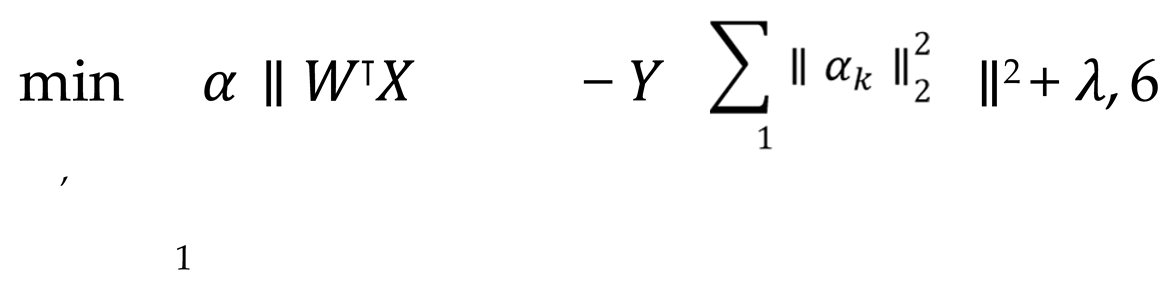

On the basis of feature alignment, further fusion of heterogeneous data is achieved through multi-view learning. In multi-perspective learning, it is postulated that there are K distinct perspectives, designated as V , V , ..., V , each of which encompasses features derived from disparate data sources. The implementation of feature fusion is achieved through the utilization of a weighted federated learning objective function, denoted as Equation 6.

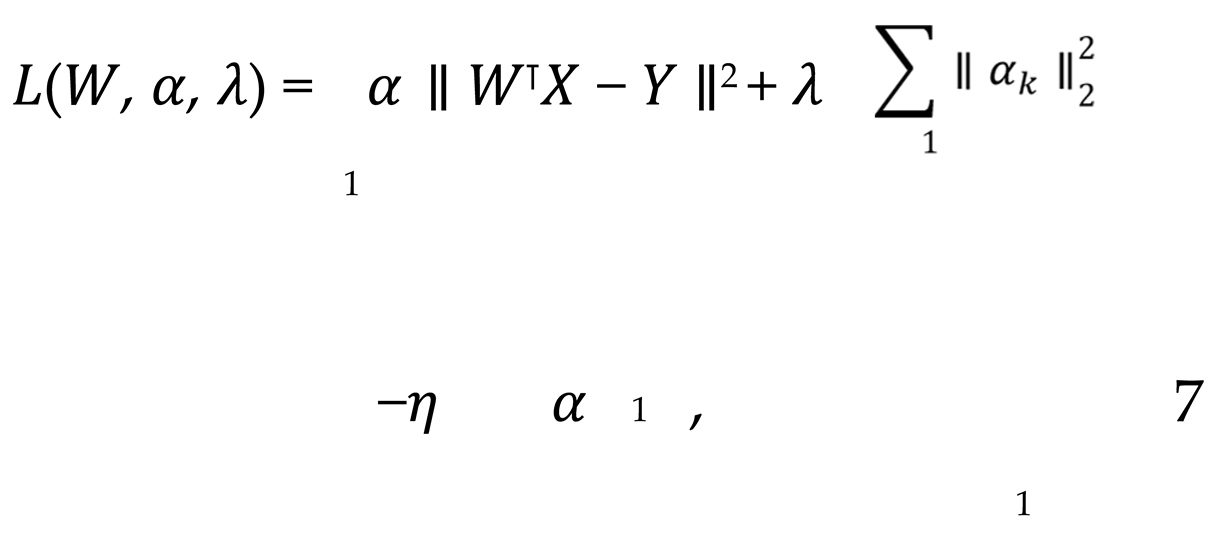

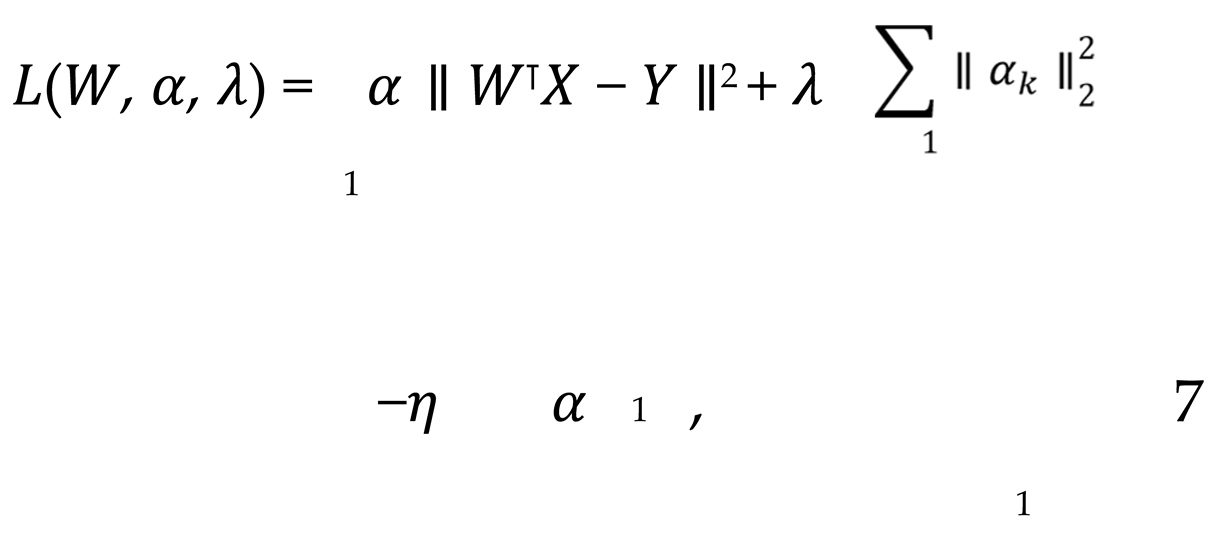

where X represents the data feature matrix of the initial k perspective, W denotes the corresponding feature weight, α signifies the perspective weight, and Y represents the global target. By optimizing both α and W concurrently, it is possible to identify the most effective combination of features across different perspectives and achieve an adaptive fusion of heterogeneous data sources. In order to achieve dynamic weight adjustment, the Lagrangian multiplier method is introduced to optimize the perspective weights, with the final objective function being, shown as Equation 7.

where

η represents the Lagrangian multiplier, which is employed to ensure the normalization of the weights associated with each perspective. By optimizing gradient descent for this objective function, the weight

α and feature matrix

W of each perspective can be adjusted dynamically, thus enabling the adaptive integration of heterogeneous data.

Figure 1 shows framework diagram of proposed model.

3.2. Privacy Protection Mechanism

The protection of privacy is a pivotal concern in the context of federated learning frameworks, particularly in scenarios where multi-party collaboration occurs within heterogeneous data environments. In order to guarantee the confidentiality of data during the processes of model training and data transfer, we have integrated sophisticated privacy-preserving technologies, including differential privacy, homomorphic encryption and secure multi-party computation. In this section, we will undertake a detailed analysis of the complex mathematical and formulaic aspects underlying these privacy protection mechanisms.

The differential privacy mechanism conceals the individual data of the participants by introducing noise during the model update process. This ensures that even if an attacker gains access to information from the training process, it is not possible to derive the data of a single participant. Let us consider the scenario in which the gradient provided by participant

i is updated to ∆

θ at each round of

t model update. In order to protect the privacy of this gradient, we introduce the differential privacy noise

η~

(0,

σ ), which is finally updated as Equation 8.

The variability of the noise

σ is determined by the privacy budget

ϵ and the sensitivity ∆

f. Sensitivity ∆

f is defined as Equation 9.

In accordance with the definition of

ϵ -differential privacy, it is imperative to ensure that the gradient update subsequent to noise addition satisfies the following Equation 10.

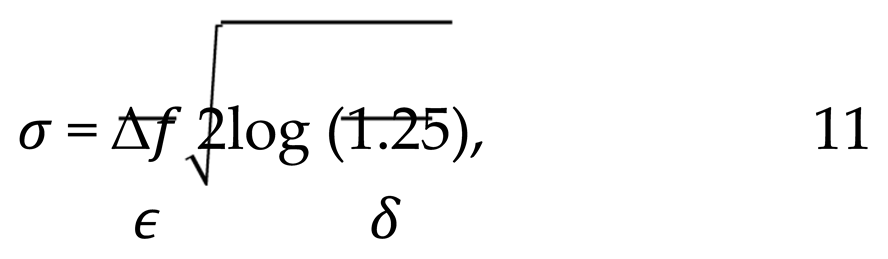

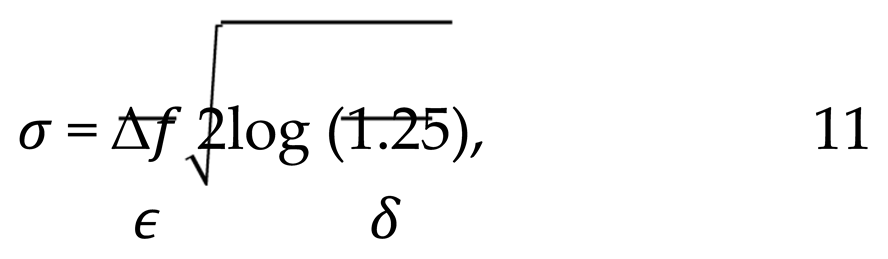

In the event that datasets X and X are adjacent, the perturbed model is employed. The noise is selected to be Gaussian distributed, and its standard deviation, denoted as σ, is determined by the following Equation 11.

where the term δ represents the probability of a privacy failure.

In addition to global differential privacy, local differential privacy can be employed to introduce noise to the data at the local level, rather than at the server side. Assuming that the local data of the participant's

i is

X , the data will first be perturbated through the Randomized Response mechanism. This ensures that each participant can add noise locally, thereby guaranteeing that even the data received on the server side cannot be directly recovered from the original data, denoted as Equation 12.

Homomorphic encryption represents a highly sophisticated privacy-preserving technology, enabling direct computation of encrypted data. In federated learning, the use of homomorphic encryption enables the server to avoid decrypting the data when updating model parameters, thereby preventing any potential data leakage.

Let us consider the case where the local gradient of the participant

i is updated to ∆

θ . In this scenario, the public key encryption mechanism is employed to encrypt the gradient, with the encryption operation represented by

Enc(·) .In homomorphic encryption, the following homomorphism is satisfies Equation 13.

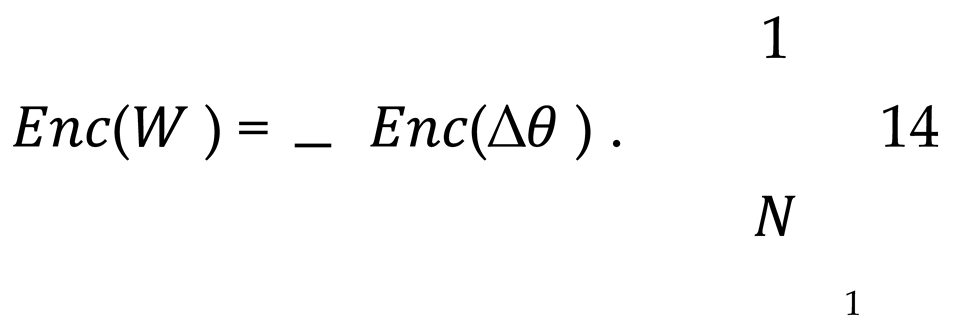

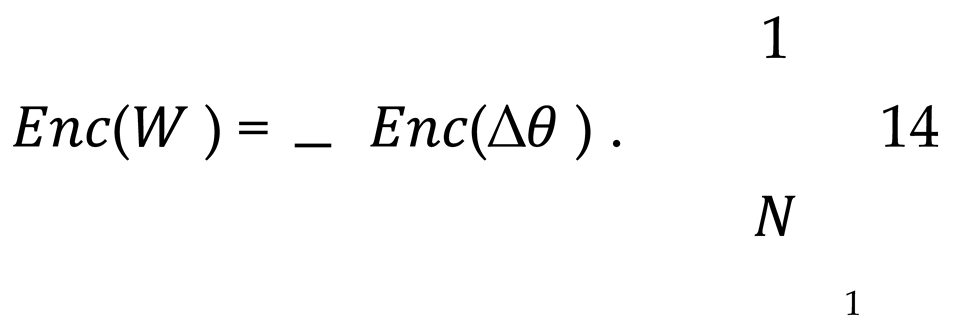

The server is capable of directly assessing the relative importance of the participants in the encrypted state, denoted as Equation 14.

Subsequently, upon the necessity for decryption, the server is able to decrypt the result

W utilizing the private key

sk, calculated as Equation 15.

To further reinforce the security measures in place, we employ the use of homomorphic encryption mechanisms with noise resilience, such as BFV (Brakerski-Fan-Vercauteren) or CKKS (Cheon-Kim-Kim-Song) encryption algorithms. The aforementioned algorithms guarantee that the results can be retrieved even in the event of noise amplification during the computation by incorporating a noise term into the encryption process. The accumulation of noise is a gradual process that occurs during the course of computation. Consequently, it is necessary to implement a process of fine-tuning in order to maintain the desired level of noise. Let us consider the encrypted gradient ∆

θ , which contains an implicit noise term

η . The objective is to ensure that the final noise

η remains within the allowable threshold

σ , described as Equation 16.

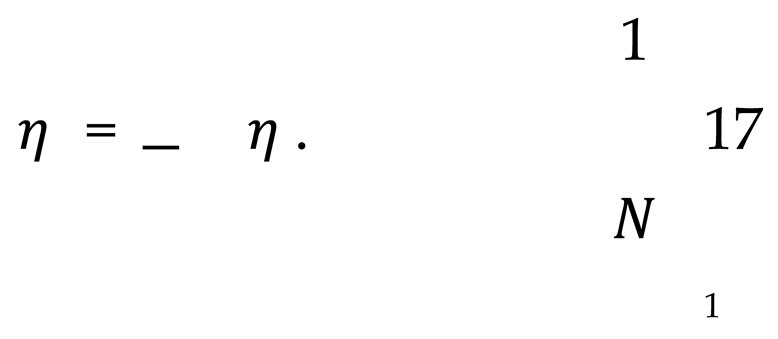

After applying a weighted average, the cumulative form of noise can be expressed as Equation 17.

In each encryption iteration, the variance σ of the noise is adjusted in order to control the final accumulated noise and ensure the accuracy of the resulting calculation.

3.3. Secure Multi-Party Computation

In light of the aforementioned considerations, we put forth a multi-level privacy protection strategy encompassing three stages: data preprocessing, model training, and result aggregation. In the initial phase of data processing, the elimination of personally identifiable information is achieved through the utilisation of de-identification technology. The hash function ℎ(∙) is employed to encode all potentially exposed data, described as Equation 18.

This process ensures that any identifiable information is removed from the data set prior to its integration into the federated learning system. In the model training phase, we employ the use of Secure Multi-Party Computation technology. Each participant performs their own gradient update ∆

θ locally and then decomposes the updated value into multiple sub-parts, which are then sent to other participants through secret sharing, denoted as Equation 19.

Once each participant has received a portion of the other participant's data, local aggregation is conducted, and security protocols are employed to prevent the intermediate computation process from disclosing the data. In the result aggregation stage, the Federated Averaging technique is employed to update the global model, whereby the local model updates of each participant are weighted by Equation 20.

In this instance, the confidentiality and integrity of the aggregated data are assured by the use of homomorphic encryption and differential privacy.