2. Methods and Materials

To address the research questions, a “

reconstructive case” approach [

10], also referred to as “

history” by [

11], was selected. This methodology was chosen to investigate the “

why,” “

what,” and “

how” within a complex system characterized by numerous interrelated decision-making and implementation variables. The objective was to develop a comprehensive and holistic understanding of a notable success case. Accordingly, a “

holistic single-case design” [

11] with theoretical sampling was employed.

An international and interdisciplinary core research team was assembled, comprising two mechanical engineering experts and one expert each in innovation management and industrial engineering. These individuals are the authors of this study. Team members were based in Austria, Germany, and the United States, facilitating a comprehensive linguistic and contextual understanding of both written and oral sources [

12]. Within this team, sub-groups were formed to conduct the specific analyses described below. Partial findings were discussed in detail during collaborative workshops, where contradictions were addressed and consensus reached to eliminate rival explanations.

A standardized case study protocol was employed across all research activities to ensure consistency and comparability. All data and individual research outputs were systematically documented in a centralized database accessible to all team members. Methodological triangulation was achieved through the use of multiple data sources, enhancing construct validity and enabling cross-validation. Interdisciplinary collaboration was facilitated through regular joint workshops, and a “devil’s advocate” role was formally assigned during group discussions to challenge assumptions and mitigate confirmation bias. Chains of evidence were established to support findings, following procedures outlined by Stake [

13]. Preliminary results were reviewed by subject matter experts in handgun development to validate interpretations.

Additional academic and industry specialists were consulted to address specific aspects of design and manufacturing. These included experts in plastics technology, machining, stamping, and bending, who provided validation for material choices and assessed the manufacturability and cost-efficiency of individual components.

Beyond physical analysis of the Glock 17 artifact, the study incorporated a wide range of documentary sources, including peer-reviewed literature, popular science publications, corporate documents, official public records, patents, and online resources. A systematic literature review was performed using the keywords “

Glock*” in combination with “

handgun*,” “

gun*,” “

pistol*,” and “

firearm*” within the German Joint Library Network catalog (Verbundzentrale des Gemeinsamen Bibliotheksverbundes), as well as in Google, Google Scholar, and ProQuest. Special attention was given to statements and interviews involving Gaston Glock (cf. [

14,

15]), and to publications authorized by him (cf. [

16]). These sources underwent qualitative analysis, and statements were clustered thematically.

All secondary analyses were independently conducted by at least two researchers and subsequently shared with the entire research team. Any discrepancies were resolved through workshop discussions. Furthermore, an expert interview was conducted with Dr. Ingo Wieser, a former specialist at the Austrian Armed Forces Weapons and Ammunition Test and Research Centre. Dr. Wieser played a pivotal role in the comparative evaluation of service pistols and was directly involved in testing early Glock prototypes during the Austrian military’s procurement process. Technical representatives from Glock GmbH also contributed by participating in in-depth technical discussions.

The study’s analytical framework was structured into three focal areas: (1) the product (Glock 17), (2) the development process, and (3) the market, customer base, and competitive environment.

(1) Product Analysis

The product analysis included four primary components: (a) patent analysis, (b) reverse engineering, (c) simulation-based functional analysis using CAD models, and (d) comparative benchmarking against competitor products. The analyses collectively focused on the product architecture of the Glock 17, particularly on the design of its individual components and the composition of its assemblies. Special attention was devoted to the human-product interaction, especially regarding ergonomics and usability in operational contexts.

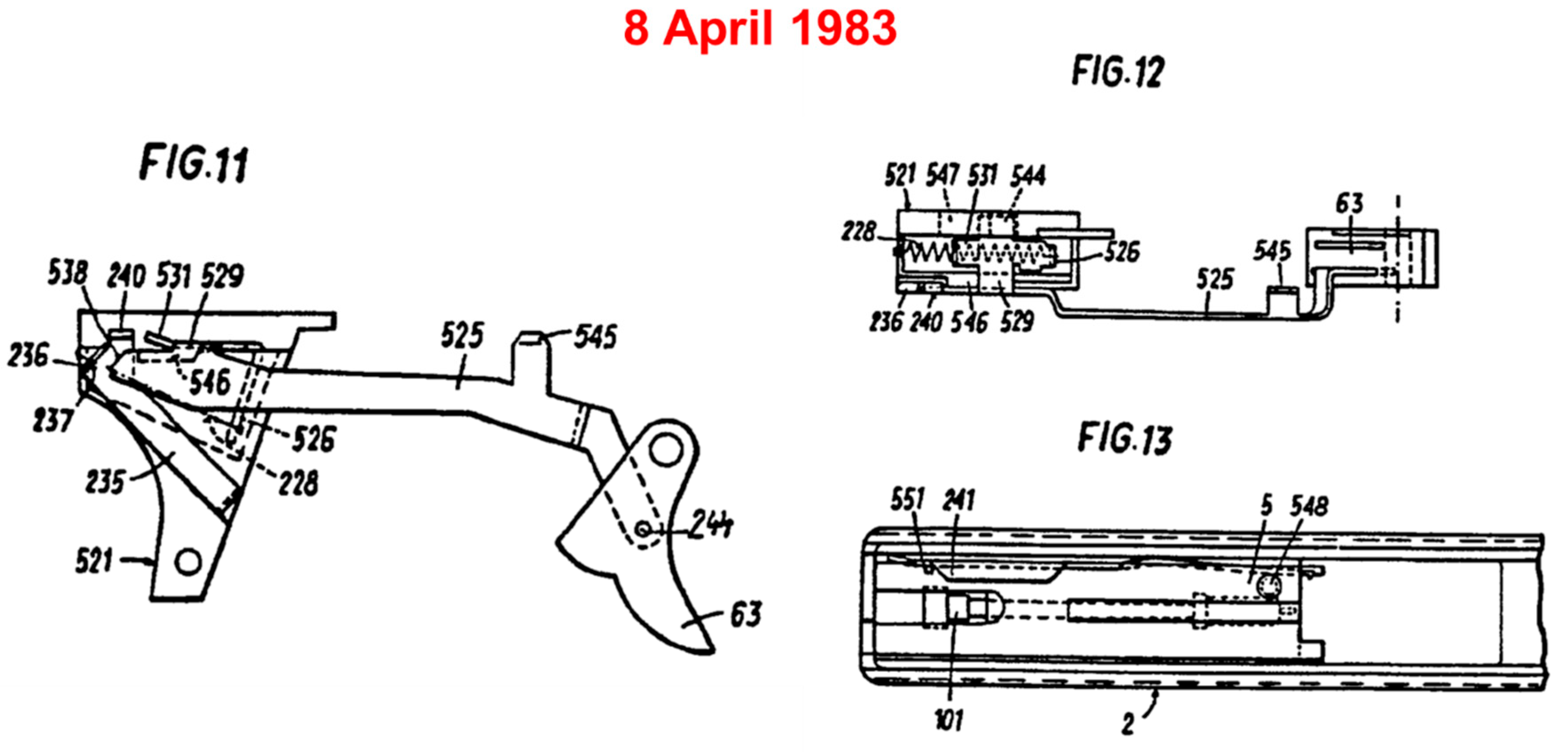

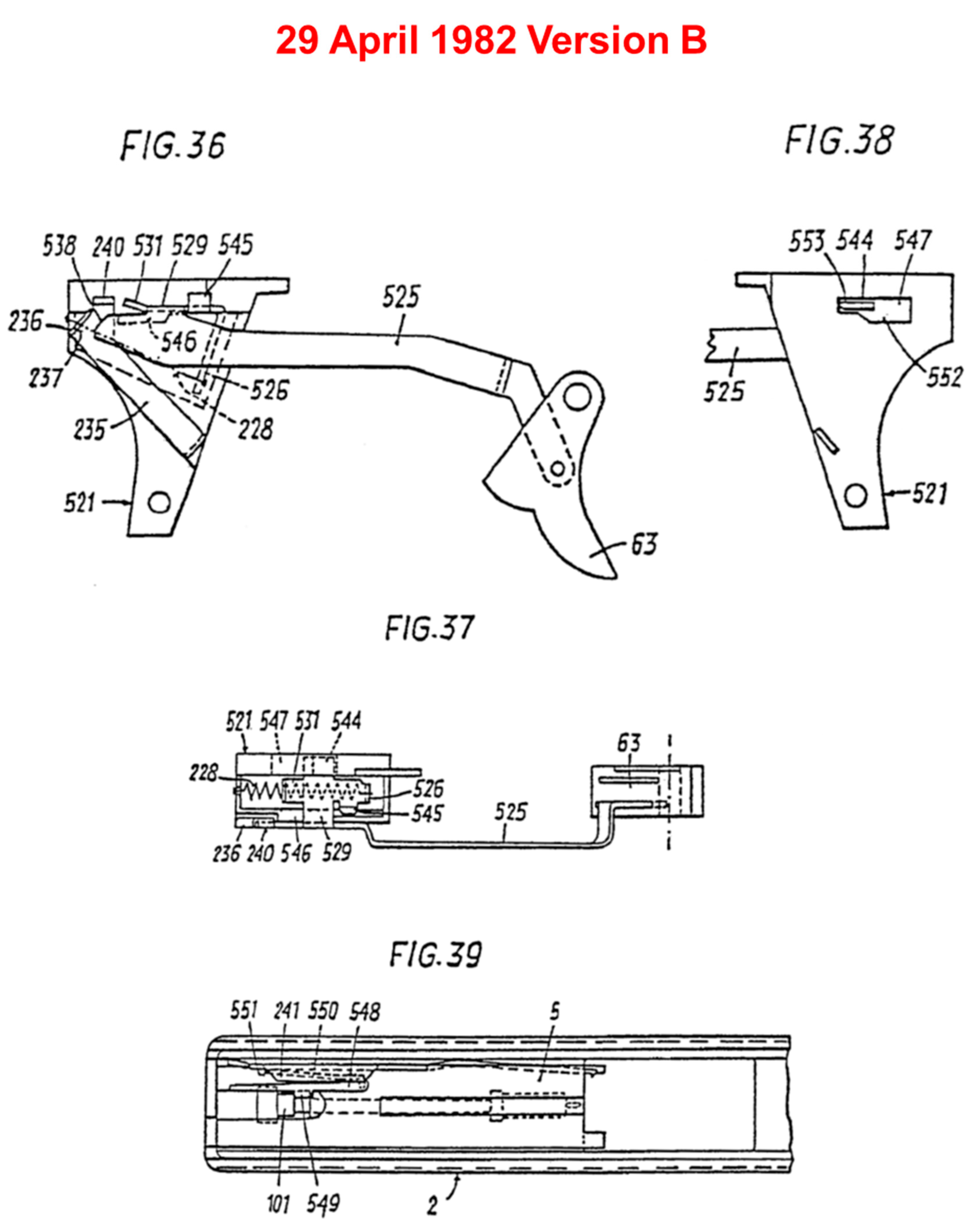

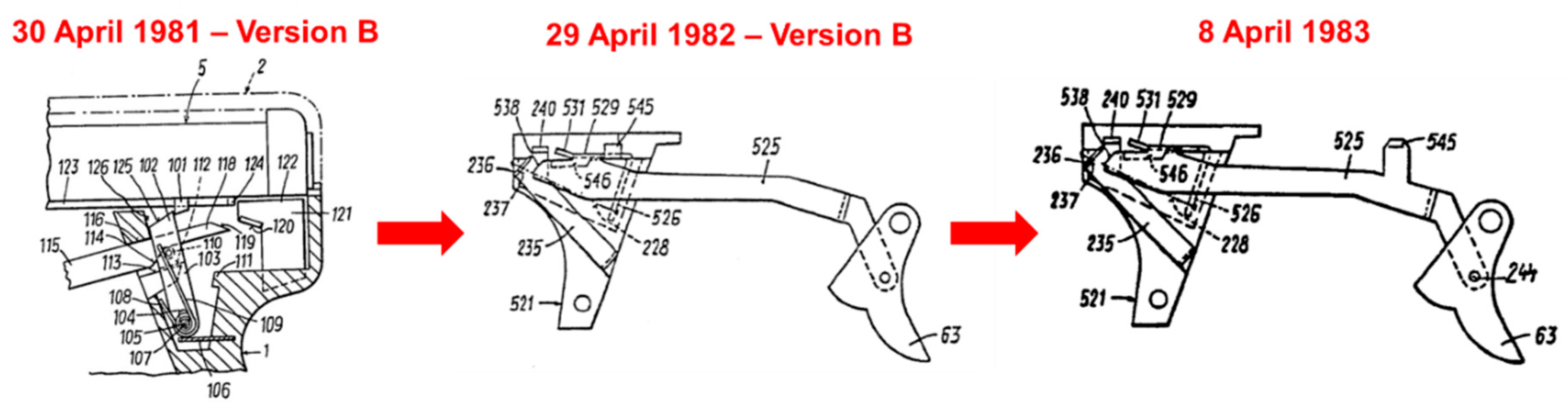

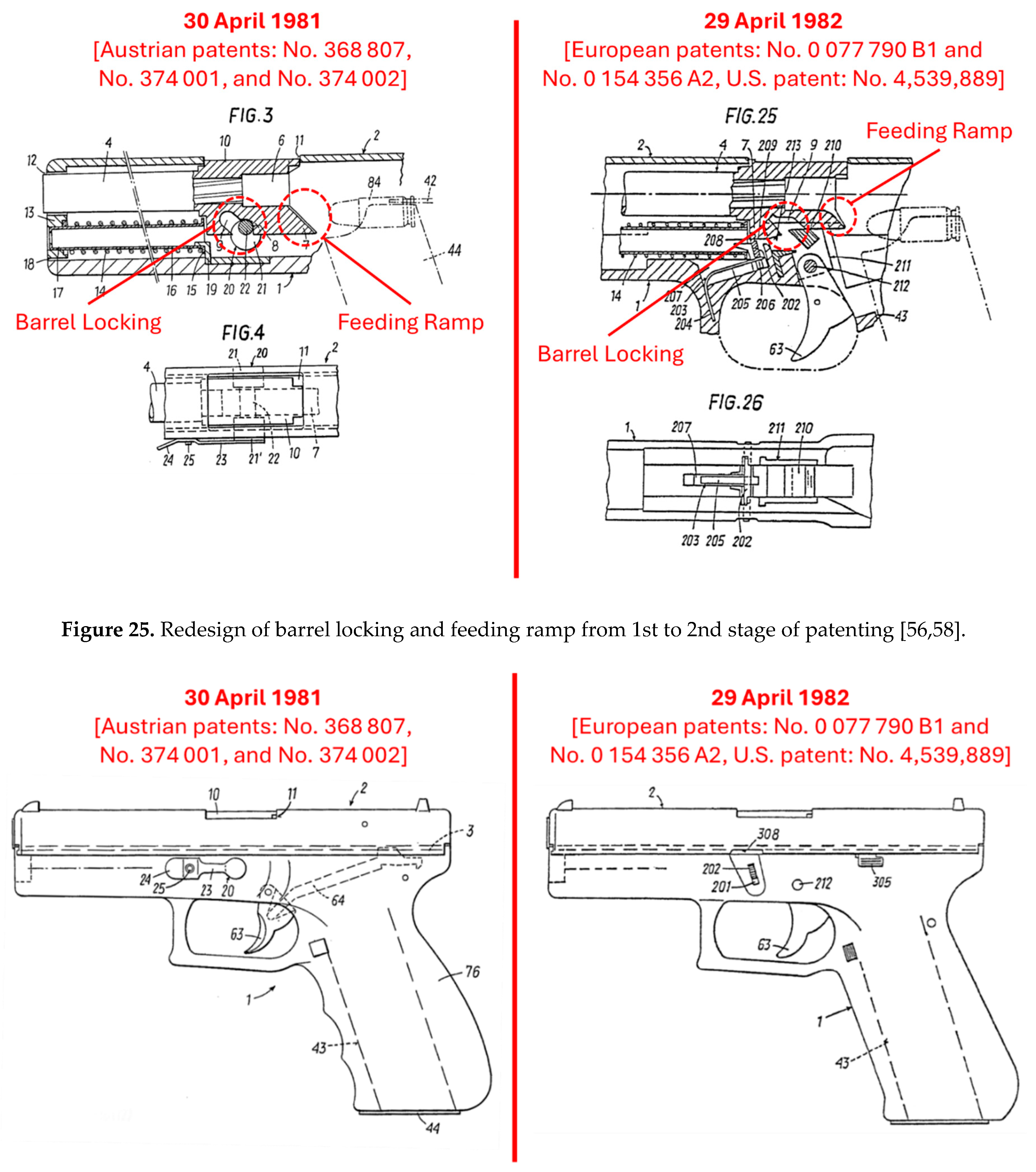

a) Patent Analysis

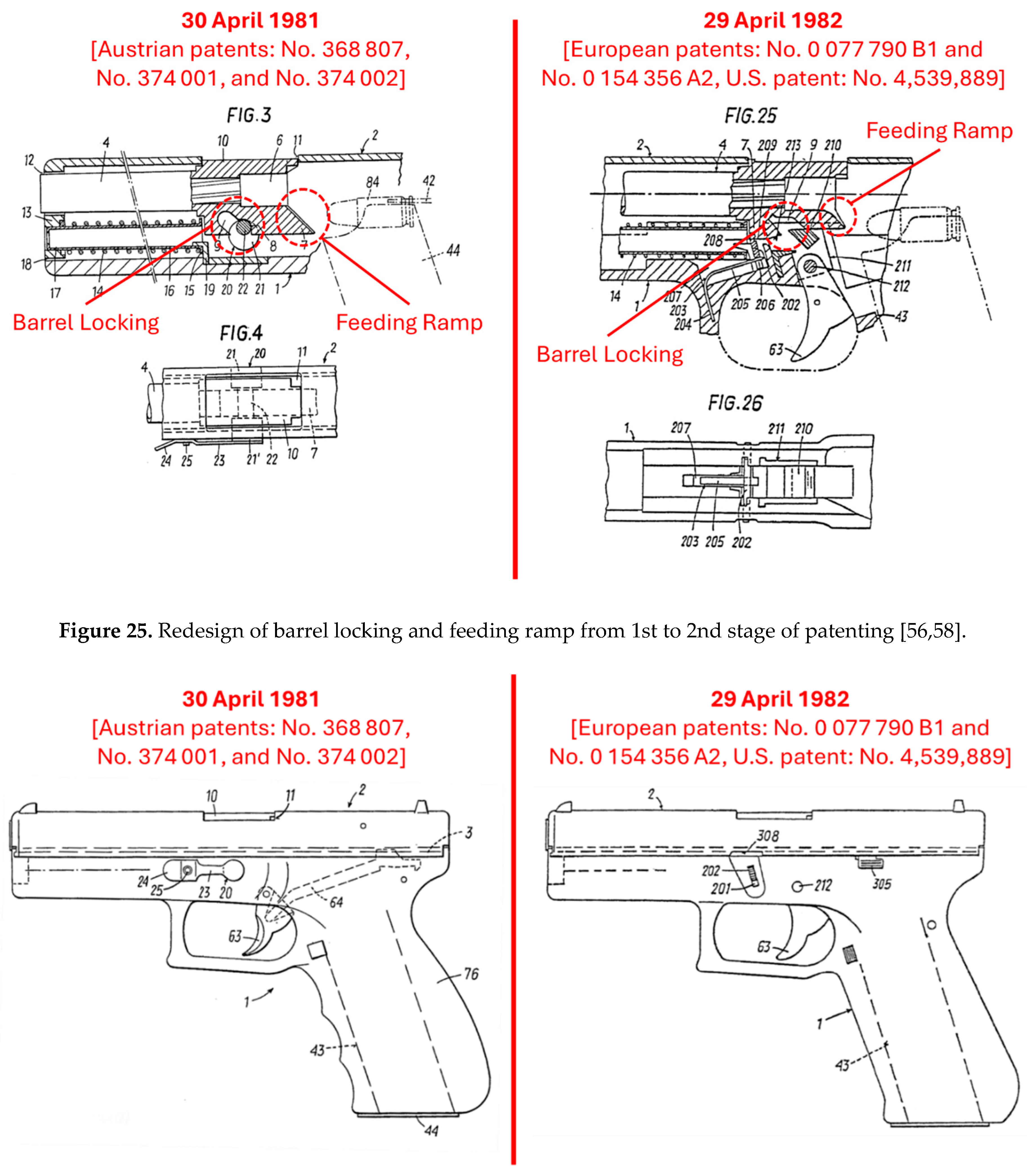

This study introduces a methodological approach that reconstructs a prototype-based, iterative-agile development process through systematic patent analysis. Patents from multiple stages of the patenting process were examined, focusing on both technical drawings and textual descriptions, to trace the design evolution of the Glock 17 and to understand the design decisions underlying its development. Special attention was given to the allocation of functions to components, with particular emphasis on the principle of functional integration (cf. [

17,

18]). This method facilitated an understanding of the rationale behind the final product architecture [

19].

b) Reverse Engineering

Due to the product’s purely mechanical structure and limited number of components, reverse engineering provided a detailed understanding of part design, functional interactions, and overall system configuration [

20,

21]. Innovative features of the Glock 17 were identified and contextualized through comparison with earlier handgun models. Additionally, material properties and geometric characteristics were used to infer the underlying manufacturing processes and, to a limited extent, potential cost structures.

c) Simulation-Based Functional Analysis

Existing CAD and multi-body simulation models were analyzed to examine dynamic interactions among components, enhancing the understanding of system-level functionality. These simulations served as digital prototypes for exploring mechanical behavior and operational sequencing.

d) Comparative Product and Requirements Analysis

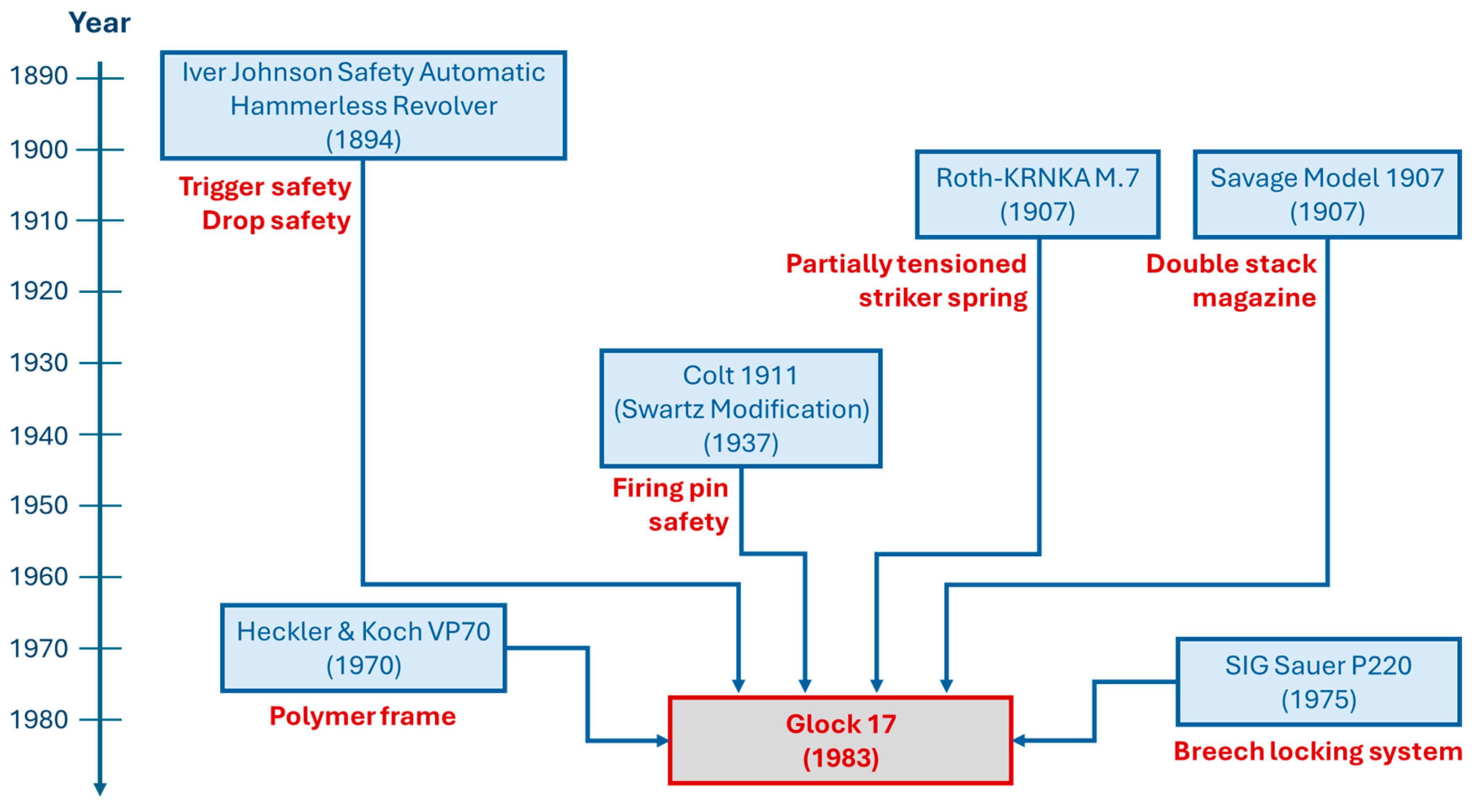

A historical analysis of handguns developed over the past century provided context for benchmarking the Glock 17. This comparative framework facilitated the evaluation of its technological innovations. To further understand user requirements, tender documents from the Austrian Armed Forces were reviewed, along with period-specific evaluations found in gun magazines (cf. [

22,

23]). These sources helped triangulate functional expectations and usability perceptions from both institutional and end-user perspectives.

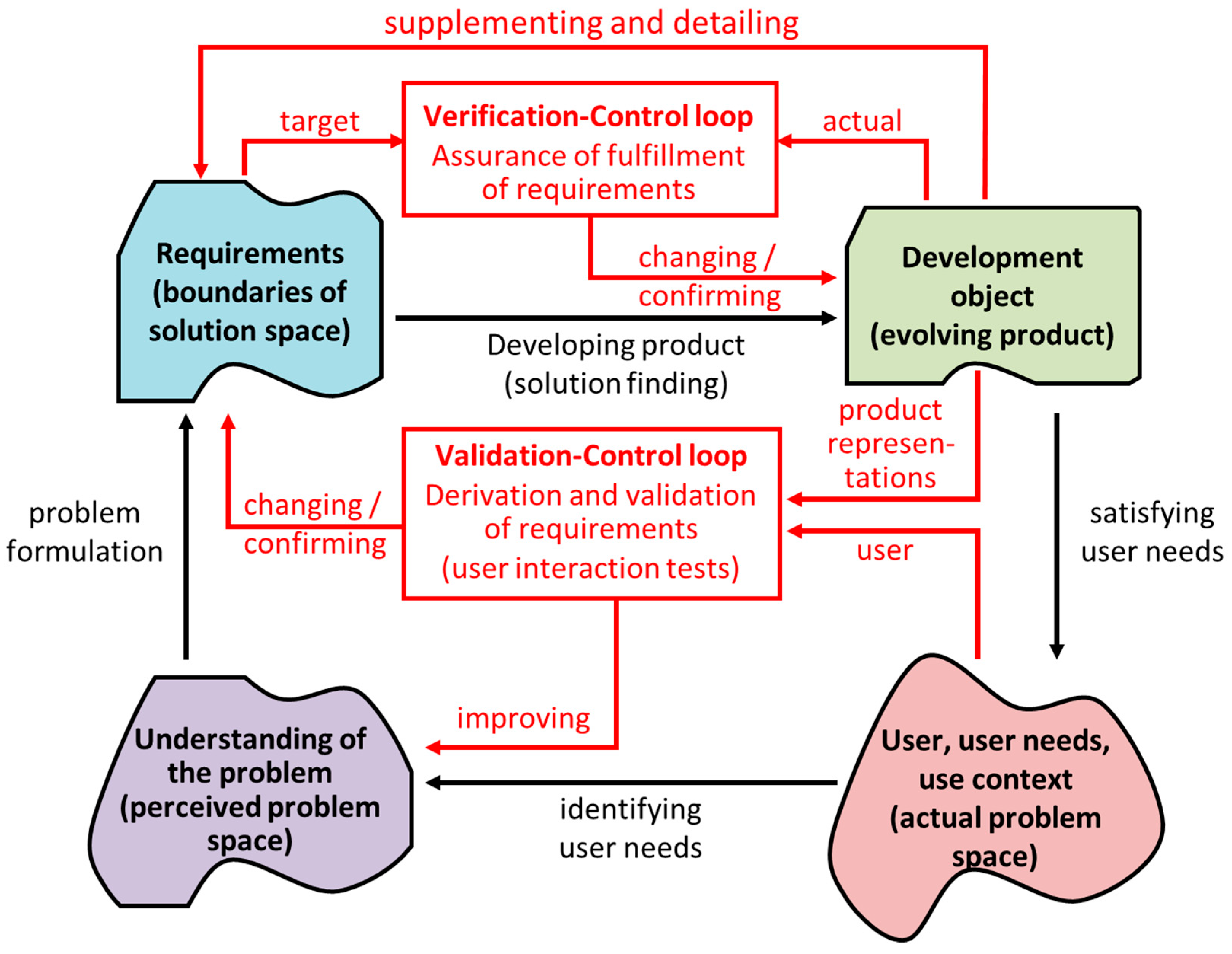

(2) Analysis of the Development Process

The development process of the Glock 17 was reconstructed through a qualitative analysis of both primary and secondary sources, including patent documents, chronological accounts from independent publications (e.g., [

1]), and authorized narratives (e.g., [

16]). Further contextual insights and validation were obtained through an expert interview with Dr. Wieser, which also enhanced the understanding of the collaboration between Gaston Glock and the Austrian Army during the design process.

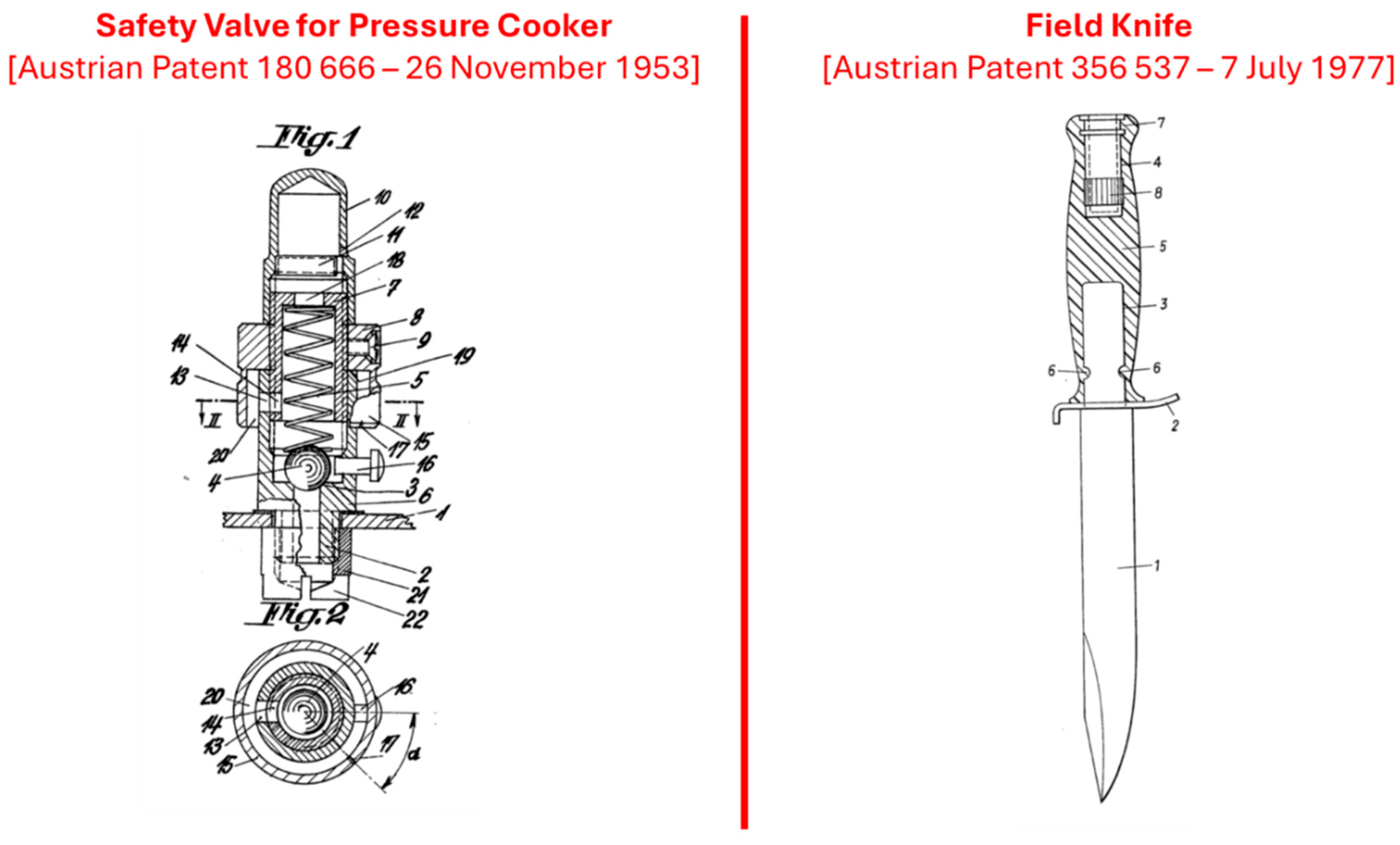

To better understand the competencies underlying the development effort, the educational and professional backgrounds of key figures – especially Gaston Glock – were examined. This analysis also considered the company’s prior product lines (e.g., military knives) and its expertise in manufacturing hybrid products combining polymer and steel.

(3) Market, Customer, and Competitor Analysis

Market data were analyzed to assess the Glock 17’s commercial impact, including sales figures and segmentation trends within the handgun industry [

24]. Special emphasis was placed on the product’s rapid adoption across military, law enforcement, and civilian segments. Key differences and commonalities in user requirements were identified and mapped across these groups.

Building on the analyses 1-3 presented above, the theoretical model delineated in

Section 5 was systematically derived and iteratively refined through abstraction during a series of structured workshops, following the case study methodology proposed by Eisenhardt [

25]. The model emerged through incremental comparison of empirical findings from the Glock case with established theoretical frameworks (e.g., [

26]). In parallel, qualitative coding of the data facilitated the identification of recurring themes and explanatory patterns within the case (“

within-case analysis”), which were subsequently synthesized and elaborated through the emerging model. To assess the broader applicability of the findings, a comparative analysis was conducted using the development of the first iPhone as a reference case – another landmark disruptive innovation [

4]. A tabular comparison highlighted notable parallels in environmental changes, innovation trajectories, and outcome characteristics (“

cross-case patterns”), thereby reinforcing the theoretical generalizability of the proposed model.

3. Key Factors of the Glock Pistol in Defining the Dominant Design for Handguns

3.1. Resolution of a Long-Standing Key Usability Contradiction

The groundbreaking core innovation of the Glock pistol lies in its safe action trigger system, which has resolved a “

key usability contradiction” [

4] that has existed since the invention of (semi-) automatic pistols: combining the firepower and rapid reload capability of semi-automatic pistols with the safety and operational simplicity of double-action revolvers. Specifically, it represents the development of a pistol that, once chambered, remains both ready to fire and safe to carry at all times, with a consistent trigger pull optimized for both safety and performance – light enough to enable rapid and accurate shooting, yet sufficiently heavy to minimize the risk of accidental discharge. To understand this key usability conflict and its increasing relevance in the early 1980s, it is essential to examine the functional differences between pistols and revolvers, as well as the technical and social changes that preceded the development of the Glock pistol.

Pistols vs. Revolvers

Handguns can generally be classified into two main categories: (semi-)automatic pistols, referred to hereafter as “pistols”, and revolvers. As this study does not aim to provide a comprehensive analysis of all handgun types, the term “revolver” in the following discussion refers exclusively to double-action revolvers.

A double-action revolver is characterized by a rotating cylinder that typically holds six cartridges. With a single, continuous pull of the trigger, two mechanical actions occur:

(1) The cylinder rotates, aligning a new chamber – containing a fresh cartridge – with the firing pin.

(2) The trigger mechanism both cocks and releases the hammer. As the hammer moves backward, it compresses the hammer spring, storing potential energy. Upon release, this energy is converted into kinetic energy, propelling the hammer forward to strike the primer, which ignites the propellant and discharges the shot.

After a shot is fired, the hammer spring is decompressed, and, in most revolvers, an additional safety mechanism prevents direct contact between the firing pin and the cartridge in the cylinder. The double-action mechanism necessitates a long, heavy trigger pull, which is both an advantage and a disadvantage. On the one hand, the long and heavy trigger pull makes it virtually impossible to accidentally discharge the gun while carrying, holstering or drawing, thereby eliminating the need for a manual safety mechanism. Thus, a double action revolver is always in the state of being ready to fire (given that the cylinder is loaded with cartridges) and safe to carry. On the other hand, such a trigger pull makes rapid and precise shooting more challenging. While most revolvers allow for single-action operation – where the hammer can be manually cocked for a lighter and shorter trigger pull – this approach is impractical in police or self-defense scenarios, where quick follow-up shots are often necessary. A second major limitation of revolvers is their relatively low firepower, resulting from both the limited ammunition capacity of the cylinder and the inherently slow reloading process. Even with the aid of a speed loader, reloading remains more cumbersome compared to magazine-fed semi-automatic pistols.

In contrast, a semi-automatic pistol uses a detachable magazine that – depending on caliber and design – can typically hold significantly more ammunition than the cylinder of a revolver and allows quick reloading by changing the magazine. The term automatic refers to the defining function of a pistol: it harnesses the energy generated by firing a round to automatically cycle the slide, ejecting the spent casing, chambering a new round and cocking the trigger mechanism, with the latter step excluded in double-action-only designs. The most common design for service pistols prior to the introduction of the Glock was the double-action/single-action (DA/SA) pistol. Like double-action revolvers, these pistols can also be carried safely, yet ready to fire. They were intended to be carried with a fully decompressed hammer spring that has no potential energy to ignite the primer and discharge a round. At the same time, the double-action mechanism of the trigger allowed to fire a shot by pulling the trigger. The first shot, fired in double-action mode, requires a longer and heavier trigger pull, as the trigger must both cock and release the hammer. All subsequent shots are fired in single-action mode, where the hammer is already cocked by the cycling slide, resulting in a shorter and lighter trigger pull. This transition between different trigger pull weights can negatively impact accuracy and shot consistency. Furthermore, additional operating steps are required after chambering a round by racking the slide as well after a shot is fired to decock the hammer before the pistol can be safely holstered. These additional operating steps, which will be discussed in more detail later, complicate the safe operation of the gun and pose potential sources of operating errors, particularly in high stress conditions.

Previous approaches to resolve the usability contradiction

Since pistols were initially developed primarily as cavalry weapons in military contexts, ensuring both safe carry and immediate readiness for use has been a fundamental challenge from the outset. Firearm designers have explored various mechanisms to address this issue.

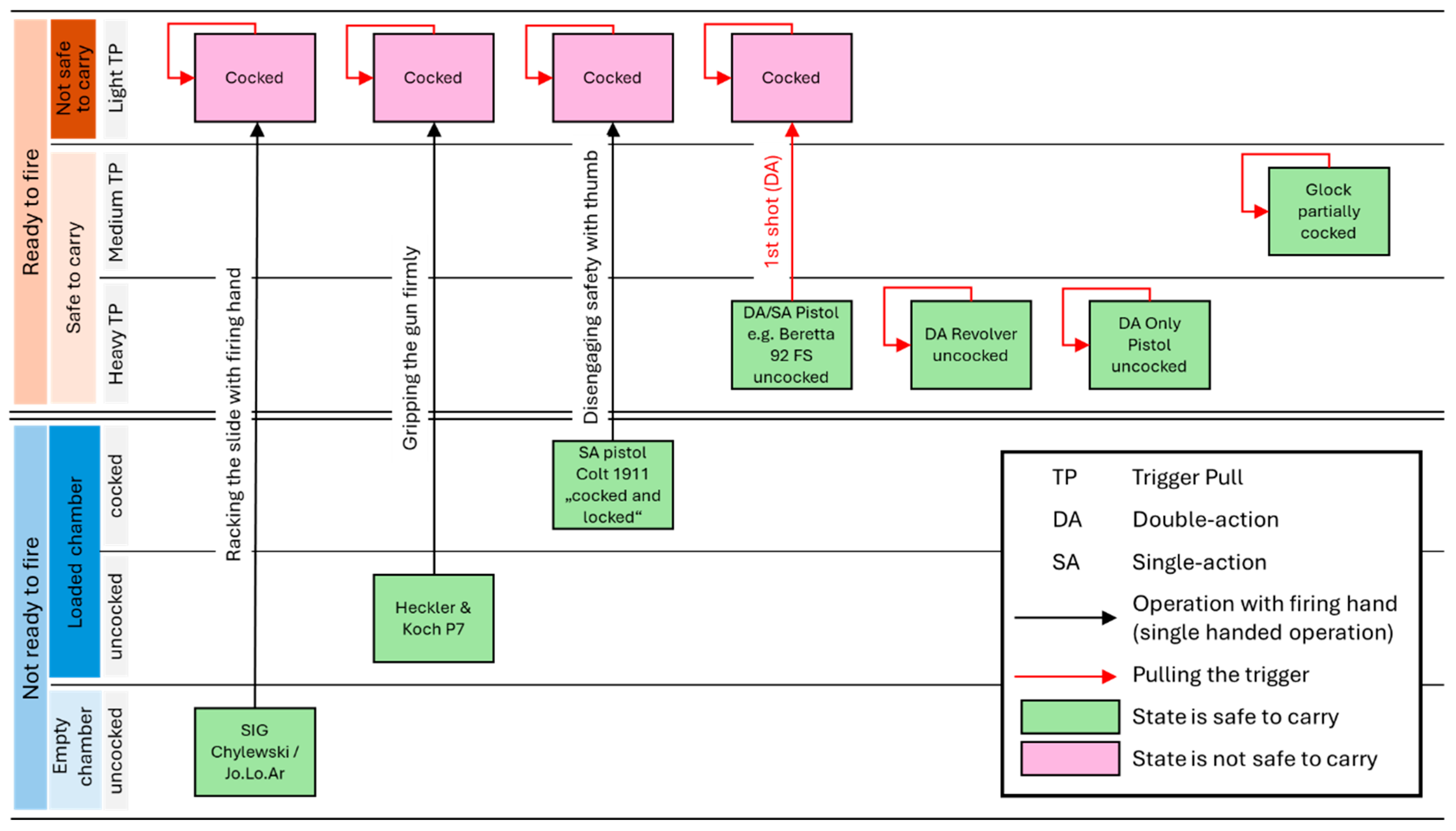

Figure 1 illustrates the operating steps of various pistol concepts necessary to transition a drawn weapon from its intended carrying condition to firing the first shot, as well as the weapon’s state after the first shot has been fired.

Single-action-only pistols, in which the trigger mechanism cannot be cocked by pulling the trigger alone, typically require an additional step before they are ready to fire. Early designs, such as the SIG Chylewski and the Jo.Lo.AR, were intended to be carried with an empty chamber and an uncocked trigger mechanism. To facilitate one-handed operation, both firearms incorporated innovative mechanisms that allowed the slide to be racked using only the firing hand. In the SIG Chylewski, this was achieved by pulling back the trigger guard with the trigger finger, while the Jo.Lo.AR omitted the trigger guard entirely and introduced a lever in front of the trigger that could be manipulated with two fingers of the firing hand. These mechanisms enabled the user to chamber a round and cock the trigger mechanism in a single motion, rendering the pistol ready to fire. However, after firing, both designs required multiple manual steps to return the weapon to a safe carry condition.

The renowned Colt M1911A1, another single-action-only pistol and the standard-issue sidearm of the U.S. military from 1926 to 1985, was designed to be carried in the “cocked and locked” condition—that is, with a round chambered, the hammer fully cocked and the thumb safety engaged. Typically, a pistol in this state presents a safety risk, as the hammer spring stores sufficient potential energy to ignite the cartridge primer, and only minimal force is required to release the sear, potentially leading to an unintentional discharge.

To mitigate this risk, the Colt M1911A1 incorporated two independently operating safety mechanisms: (1) a passive grip safety located on the back of the grip, which prevents the trigger from being pulled unless the shooter firmly grips the pistol, thereby depressing the safety, and (2) a manually operated thumb safety in the form of a frame-mounted lever on the left side of the pistol. When engaged, the thumb safety locks the sear, preventing the hammer from falling and the firearm from discharging. Upon drawing the pistol, a swift downward motion of the firing hand’s thumb disengages the safety, rendering the weapon ready to fire. Reholstering the firearm safely requires only reactivating the thumb safety, while the hammer remains fully cocked.

In the Heckler & Koch P7, also a single-action-only pistol, the designers sought to enhance usability by integrating the additional step required to ready the firearm into an action already necessary for drawing it – gripping the weapon – thus eliminating extra operating steps. This striker-fired pistol had a grip cocking mechanism, a safety lever integrated into the front of the pistol grip, which was operated by the three fingers around the pistol grip. The firing pin spring was automatically cocked by firmly gripping the pistol and decocked when the grip was released. Unlike traditional double-action/single-action (DA/SA) pistols, this design ensured a consistent trigger pull for every shot. However, this system presented practical challenges as it is difficult to move the three fingers surrounding the pistol grip independently of the trigger finger, particularly as a considerable force of approximately 700 N was required to operate the grip cocking mechanism [

27]. In addition, with such a pistol, the safety is always disengaged when the grip is firmly held, and a shot can be fired in single action mode with a relatively light trigger pull. This also applies to the process of drawing and holstering the gun. As gripping the gun is the first step in drawing and releasing the grip is the last step in holstering, the gun remains fully cocked throughout these entire processes. As a result, several accidental discharges have been documented when the P7 has been used as a service weapon by various police departments in Germany [

28].

Another approach to resolving the usability contradiction and combining the advantages of both revolvers and a semi-automatic pistols, was the development of double-action-only (DAO) pistols, such as the Smith & Wesson Model 5946 and the Beretta 92D, both manufactured throughout the 1990s. In these firearms, the recoil energy was used exclusively for ejecting the spent casing and chambering a new round. However, cycling the slide did not tension the hammer spring; it remained fully decompressed, regardless of whether the slide was manually racked or cycled after each shot. Like double-action revolvers, these pistols automatically returned to a safe-to-carry condition after each shot, thereby eliminating the need for the additional decocking procedures required in double-action/single-action pistols. However, this design inherited a major drawback from the double-action revolver: the consistently high trigger pull required for each shot, which severely compromised rapid and accurate shooting, leading some to even describe this concept as “

the worst combination of both types” [

29].

Changes in the social and technical environment preceding the introduction of the Glock pistol

Before examining how Gaston Glock successfully resolved the usability contradiction through the design of the Glock pistol, it is essential to first consider the social and technological changes that made addressing this contradiction increasingly urgent. The most significant shift in the social environment during the 1980s was the rise in urban crime rates in the United States, largely driven by drug-related gang violence [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. The most important change in the technical environment was the introduction of double-action/single-action (DA/SA) pistols chambered in 9 mm, featuring double-stack magazines capable of holding 15 or more rounds in the 1970s, commonly referred to as “

wondernines” back then [

36,

37]. Due to the substantial profits generated from drug trafficking, the gangs had access to considerable financial resources, which enabled them to arm themselves with these modern high-capacity 9 mm semi-automatic handguns. The widespread adoption of these firearms by criminal groups created a significant tactical disadvantage for law enforcement. U.S. police officers, still equipped with service revolvers, found themselves increasingly outgunned in high-intensity confrontations and prolonged shootouts, as revolvers had limited ammunition capacity and slower reload times [

38,

39]. In response, law enforcement agencies began transitioning from revolvers to semi-automatic pistols in the mid-1980s. Given the constraints on training time and resources, law enforcement agencies prioritized firearms that balanced firepower with ease of handling and safety. Consequently, addressing the challenge of combining the firepower of semi-automatic pistols with the simplicity and safety of revolvers became a critical factor in the selection and adoption of new service weapons.

In the military domain, handgun innovation remained stagnant in the decades following World War II. By 1980, most of the world’s armed forces were still equipped with pistols based on designs from World War II or earlier. This stagnation stemmed from the limited role of handguns in Cold War military doctrine, where their necessity for soldiers was increasingly questioned. The Austrian Armed Forces, experiencing persistent issues with the aging Walther P38 – also a World War II-era design – initiated efforts to procure a new service pistol as early as 1971 [

16]. In 1979, the Weapons and Ammunition Testing and Research Center of the Austrian Armed Forces conducted extensive trials in which 22 different double-action pistols in 9 mm Luger caliber available on the market were compared (Ingo Wieser, interview by author, April 11, 2025). These trials did not result in a procurement decision for a new service weapon [

16]. Initial attempts of the Ministry of Defense to collaborate with the established Austrian arms manufacturer “

Steyer-Daimler-Puch AG” on developing a modern handgun did not materialize, since SDPAG’s resources were already allocated to the development of a new assault rifle and no funding for the development costs was provided [

16]. In spring 1980, Gaston Glock, whose company had been supplying the Austrian army with machine gun belts, training hand grenades and field knives for several years, started the development of his own pistol [

16]. Sources differ on whether the initiation of the project was primarily the result of Gaston Glock’s entrepreneurial foresight – recognizing a promising opportunity in the forthcoming tender for a new service weapon [

1] – or whether it was mainly driven by the Austrian Ministry of Defense’s efforts to secure a domestic manufacturer (audio recording of Ingo Wieser’s statement in [

14]). What is certain, however, is that Glock began development of the pistol independently, assuming full financial and technical risk. At the same time, the Austrian military offered significant support by conducting intensive testing of the initial prototypes in 1981 and providing critical input for their further refinement. The importance of this feedback is evident in the substantial progress made between the initial patents filed in 1981 and the subsequent stage of patenting a year later. This progress involved major conceptual revisions, which ultimately led to a reliable and durable embodiment of Glock’s fundamental innovative idea (see section 4.3). Thus, by the time the official tender for the Austrian Army’s new service pistol was issued in 1982, Glock was able to submit a fully reengineered, pilot-production model that represented a significant improvement over the initial prototypes.

Although the Austrian Armed Forces’ procurement tender – outlining 17 specific requirements – served as the initial impetus for the development of the Glock pistol, Gaston Glock strategically designed his firearm with a broader market in mind. From the outset, he considered not only the relatively limited order volume from the Austrian Armed Forces but also potential future contracts from law enforcement agencies, military organizations, and the civilian market [

16].

Resolution of the usability contradiction by the Glock pistol

The Glock pistol at the time of its introduction was the only design that successfully resolved the key usability contradiction described at the beginning of this section. Once the slide was racked, the pistol remained in a state that was both ready to fire and safe to carry (

Figure 1). Additionally, the Glock pistol maintained a consistent trigger pull weight within the optimal range for every shot, balancing safety and the facilitation of fast and accurate shooting. The U.S. patent for the Glock pistol demonstrates that Glock identified the key usability contradiction during development and addressed it deliberately, as evidenced by the following excerpt from the “Summary of the Invention” section:

“Handling of the pistol according to the instant invention is therefore as simple as possible. The pistol is ready after chambering of the cartridge in the barrel for shooting at any time and is nonetheless completely safe from unintentional shots. Similarly in this condition the pistol is fully drop- and jar-resistant. As a result of the unchanging trigger force accuracy is increased. Simple and safe handling of the pistol is ensured even for the unpracticed user.” [

27]

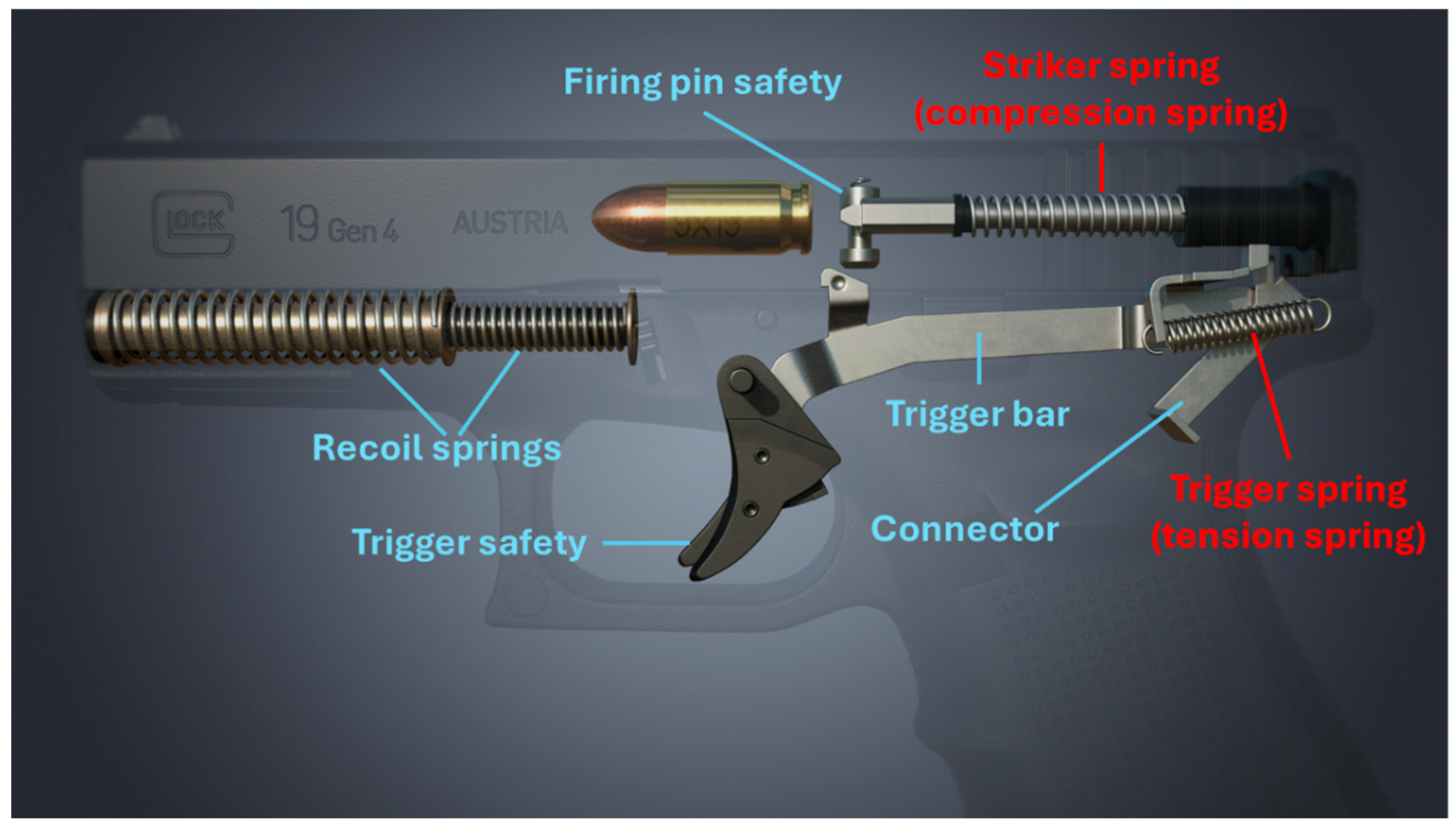

The usability contradiction was resolved through two key innovations in the Glock pistol: (1) a striker-fired mechanism in which the striker spring is only partially cocked after each shot, with a counteracting trigger spring assisting the trigger pull, and (2) a trigger bar capable of movement in two non-parallel directions, allowing it to both tension the striker spring and control the locking and release of the firing pin. We first examine the trigger mechanism, which is controlled by the counteracting forces of the striker spring and the trigger spring.

The Glock’s striker-fired mechanism is only partially cocked after chambering a round and following each shot. The potential energy stored in the striker spring remains in a subcritical range, meaning that when converted, it is insufficient to impart the striker with the kinetic energy required to ignite the primer. The preloaded striker system was inspired by the trigger mechanism of the ROTH/KRNKA M.7 pistol (cf. [

40,

41]). However, a purely partial preloading of the striker spring – such as in the ROTH/KRNKA M.7 – would have been merely a compromise and would not have fundamentally resolved the usability contradiction. A striker spring that is preloaded within the subcritical range increases the safety of the pistol and reduces the required trigger travel but does not lower the trigger pull weight necessary for firing. The key innovation in the Glock pistol was the implementation of a second spring, the so-called trigger spring, which acts on the trigger bar and pulls it backward when the trigger is actuated (

Figure 2). This trigger spring generates a pulling force that supports the shooter’s trigger movement, which must fully tension the striker spring before firing. Consequently, the shooter only needs to apply a force to the trigger that results from the difference between the opposing compressive force of the striker spring and the assisting tensile force of the trigger spring. By incorporating the trigger spring, an additional degree of freedom is introduced, allowing the trigger force to be independently adjusted at a given striker spring preload

2:

“The trigger or cocking force is the difference between these spring forces [the forces exerted by the firing pin spring and the trigger spring] and can be set at a hair trigger or a relatively stiff novice level.” [

27]

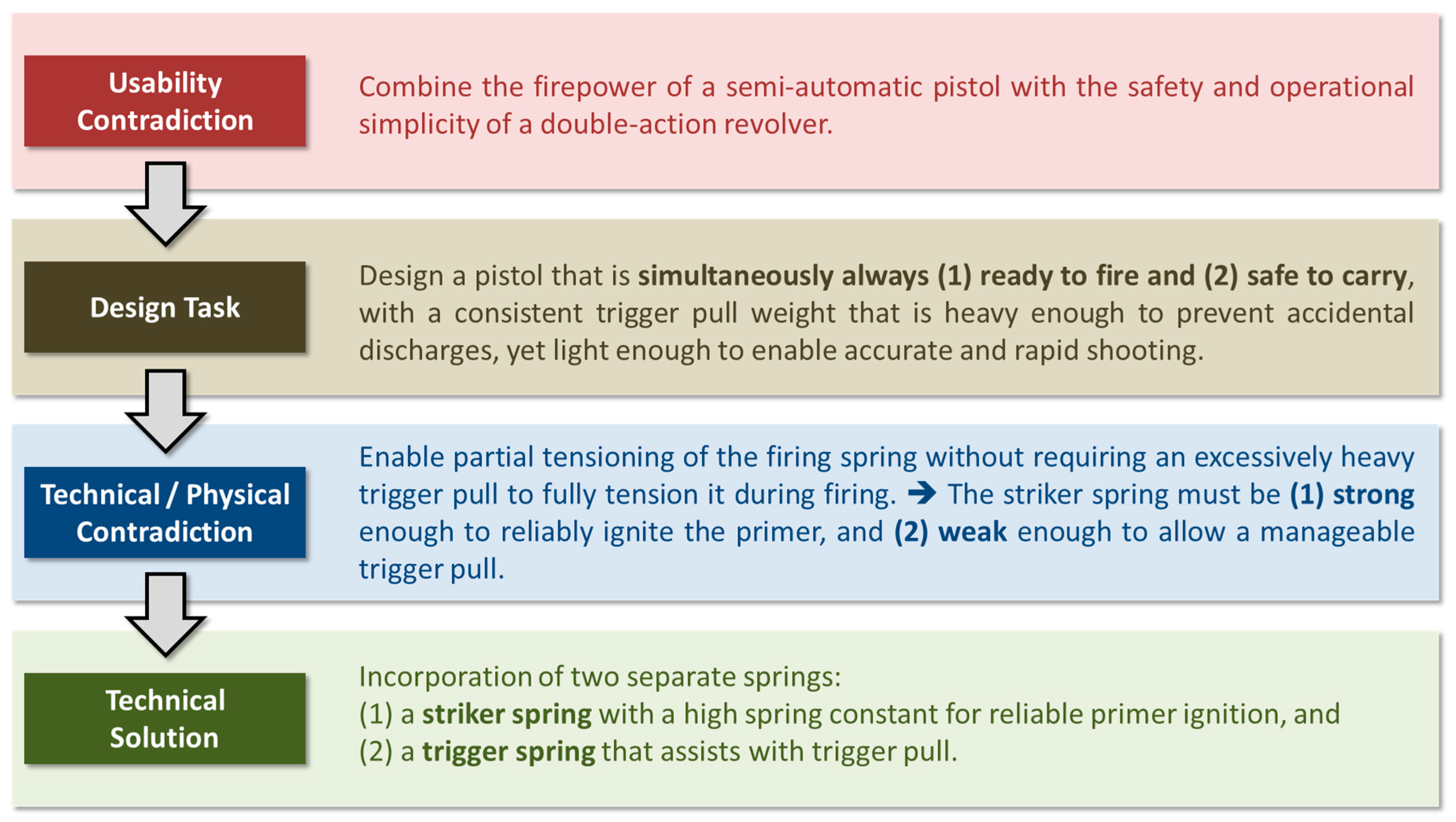

From a design theory perspective, Glock identified a usability contradiction, formulated a corresponding development task, extracted the central technical/physical contradiction, and ultimately resolved it (

Figure 3). The solution exemplifies the application of the TRIZ (Theory of Inventive Problem Solving) principle of “

Separation in Space”. This principle is one of four TRIZ separation principles used to resolve physical contradictions that arise when a system or component must simultaneously exhibit opposing properties. In the case of the Glock pistol, the striker spring presents a physical contradiction: it must store sufficient potential energy to ignite the primer while maintaining a low trigger pull weight – two requirements that are at odds. A low spring constant facilitates easier tensioning (i.e., reduced trigger pull weight) but fails to store enough energy for ignition. Conversely, a high spring constant ensures sufficient energy storage but increases the trigger pull force. Integrating both functions into a single spring at a single location would inevitably compromise either trigger pull weight or striker force.

The “Separation in Space” principle resolves this contradiction by spatially distributing the functions across separate components. In Glock’s design, two distinct springs serve complementary roles:

This spatial separation, which enabled Glock to achieve both optimal energy storage for reliable ignition and an optimal trigger pull weight, constitutes the innovative core of the Glock pistol, as it represents a genuinely novel invention previously unseen in firearm design. Accordingly, it is explicitly referenced in the title of Glock’s U.S. patent: “

Automatic Pistol With Counteracting Spring Control Mechanism” [

27].

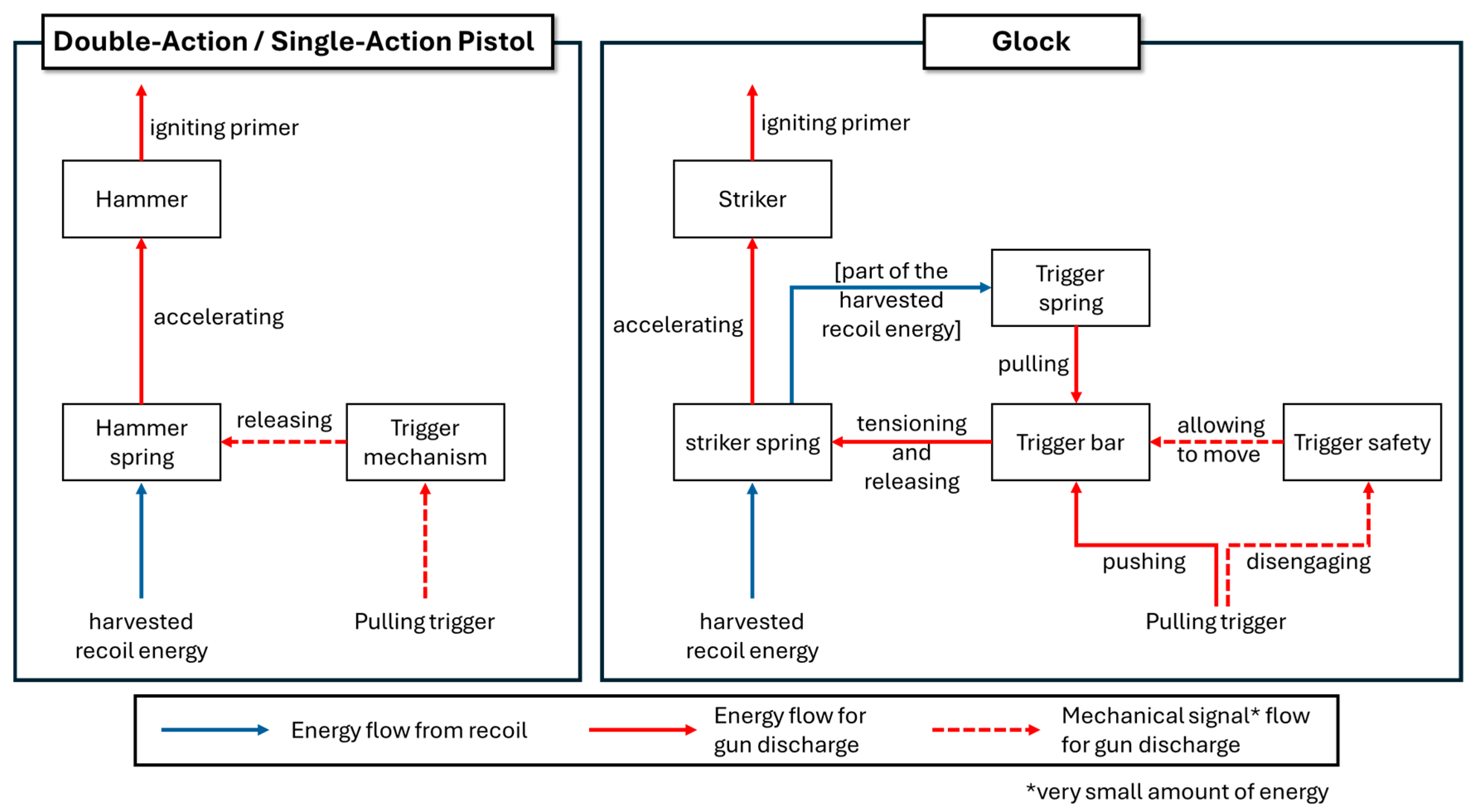

From a systems engineering perspective, after firing, only part of the harvested recoil energy is stored in the striker spring, while another portion is stored in the trigger spring. The energy stored in the trigger spring remains in a secure bypass state and can only be accessed through deliberate actuation of the trigger (

Figure 4).

The trigger bar serves as the core component of the trigger system, integrating multiple functions (

Figure 5). It moves both backward and downward, performing three functions that were traditionally carried out by separate components in firearms prior to the Glock’s introduction: (1) tensioning the striker spring, (2) locking the firing pin, and (3) acting as a sear to release the firing pin. Additionally, during the trigger pull, the trigger bar deactivates both the firing pin safety and the drop safety. This functional integration, embodied in the trigger bar’s complex three-dimensional shape, eliminates the need for manually operated safeties and simplifies pistol operation to a single trigger pull. As a result, “

the condition of the pistol is the same before the first shot as it is before the subsequent shots” [

27] – both safe against accidental discharge and ready to fire. This design relieves the user from the task of operating a manual safety, thereby eliminating a potential source of user error.

How a Glock pistol functions

The following section details the complete cycle of the Glock pistol, illustrating its main components and operational states

34 (

Figure 6):

1. Rest State

At rest, the striker spring is partially compressed, while the trigger spring is fully tensioned. In this state, three independent safeties are automatically engaged. Two of these mechanisms specifically prevent unintentional movement of the trigger bar caused by inertial forces resulting from external impacts (e.g., dropping the firearm), the third one blocks the tip of the firing pin:

- (1)

Drop/Jar Safety: This mechanism prevents forward and downward movement of the trigger bar, thereby blocking release of the firing pin, which is retained by the rear end of the trigger bar. This is achieved by securing the left arm of the cruciform sear plate within a cutout in the trigger mechanism housing, which also serves as the forward stop for the trigger bar (

Figure 7).

- (2)

Trigger Safety5: This mechanism inhibits rearward movement of the trigger bar induced by inertial forces, i.e., the same motion that occurs during an intentional trigger pull. It also prevents accidental discharge resulting from lateral pressure on the trigger.

This mechanism consists of a pivoted lever that protrudes through the trigger face and extends through the trigger body, emerging at the top rear where it contacts the frame, blocking a rearward movement of the trigger [

23] (

Figure 8). When the trigger is depressed, the safety lever pivots, causing its rear portion to move upward into the trigger body and disengage from the frame [

23]. This allows the trigger to move rearward, facilitating discharge.

The inclusion of this safety is necessitated by Glock’s fundamental design principle, which involves two counteracting springs acting on the trigger bar: Since the trigger spring continuously exerts a rearward and upward force on the trigger bar, an external impact or lateral pressure on the trigger would only need to overcome the difference between the forces exerted by the striker spring and the trigger spring to cause an unintended discharge. The trigger safety prevents this by mechanically blocking rearward movement of the trigger – and, consequently, the trigger bar – unless the trigger is deliberately pulled. From a systems engineering perspective, it ensures that the energy stored in the trigger spring can only be released through a deliberate actuation of the trigger.

- (3)

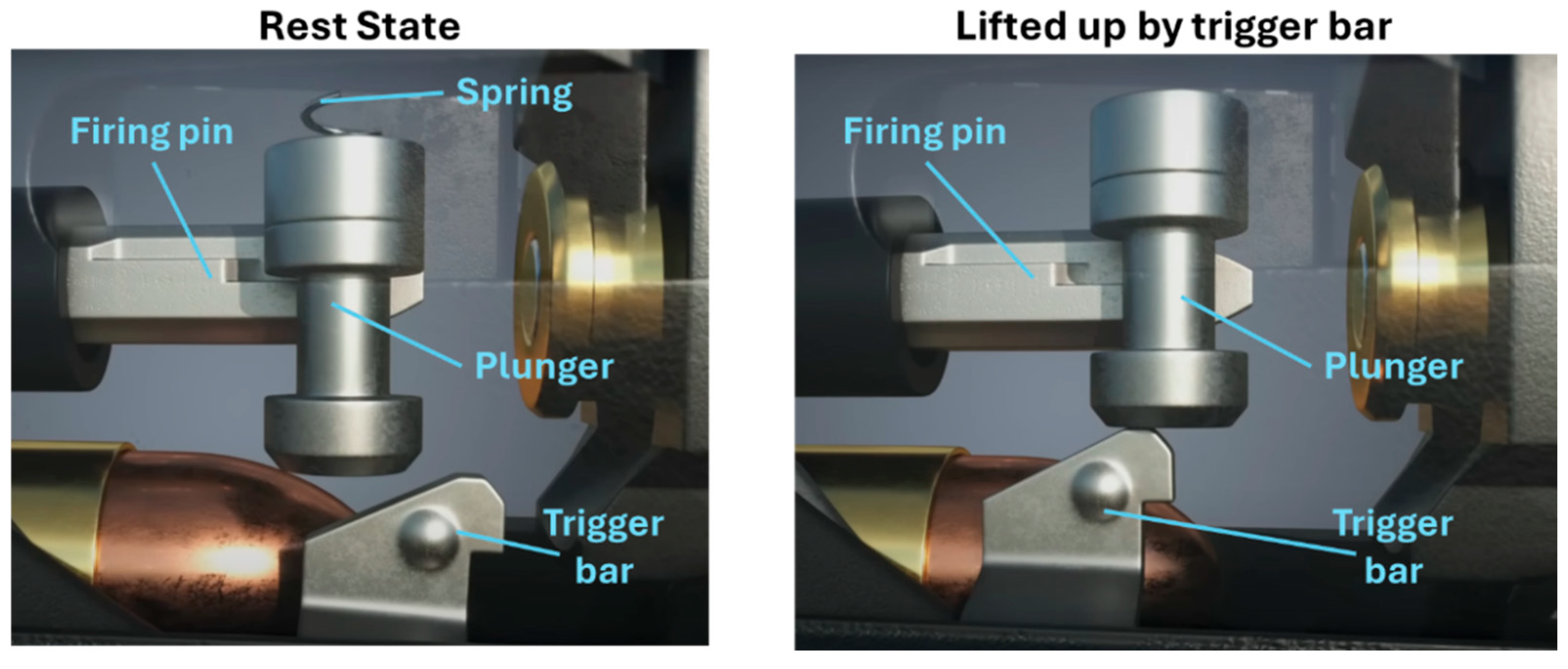

Firing Pin Safety: This mechanism consists of a spring-loaded plunger positioned in front of the firing pin, preventing forward movement of the firing pin (

Figure 9) (see also section 4.3, stage 3 of patenting).

2. Trigger Pull – First stage: Safety releasing and cocking

As the user pulls the trigger, the trigger safety disengages, allowing the trigger and its connected trigger bar to move rearward. This movement compresses the striker spring further as the trigger bar engages a downward extension of the striker. Simultaneously, an upward extension of the trigger bar lifts the firing pin safety plunger, clearing the firing pin’s path. The rearward movement of the trigger bar is substantially assisted by the trigger spring, which progressively releases tension. Near the end of its stroke, the rear end of the trigger bar engages the cam surface of the connector. The trigger travel of this first stage is approximately 5,5 mm.

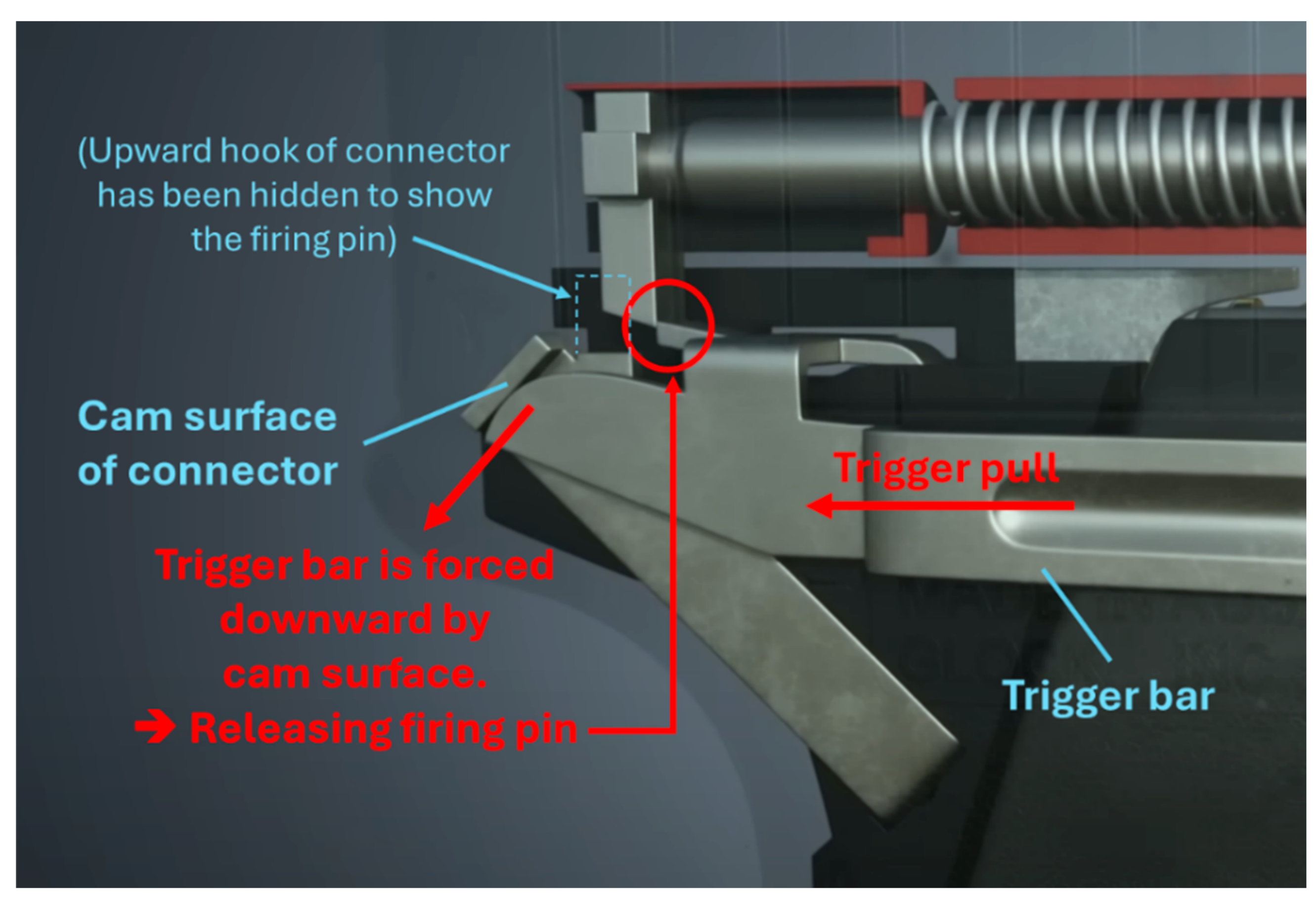

3. Trigger Pull – Second stage: Discharge

The cam surface of the connector forces the trigger bar downward, disengaging it from the firing pin extension

6 (

Figure 10). As a result, the fully compressed striker spring propels the firing pin forward, striking the primer and firing the cartridge. At this moment, the trigger spring retains residual tension. The trigger travel of this second stage is approximately 2,5 mm.

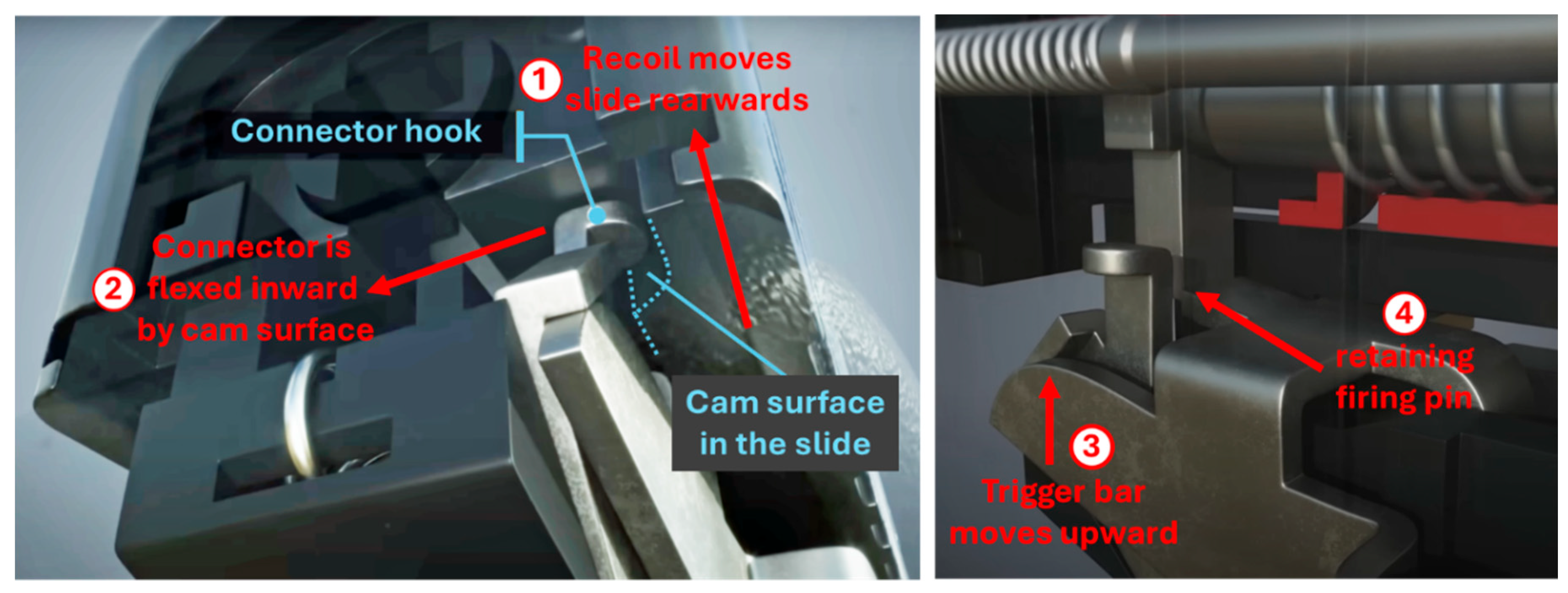

4. Slide Recoil (Rearward Movement)

The recoil force from firing the cartridge drives the slide rearward, compressing the recoil spring. As the slide moves, it carries the striker rearward until its extension is positioned behind the trigger bar. The rearward motion also forces the connector inward via a cam surface in the slide that engages with an upward hook of the connector, flexing it inward (the connector acts as a leaf spring, which is also reflected by its German name “

control spring”). This mechanism enables the trigger bar to move upward again, surpass the connector cam surface, and retain the firing pin during the slide’s forward movement (

Figure 11).

In many pistols, a separate component – the so called disconnector – disengages the trigger bar from the sear after a shot is fired, preventing multiple discharges from a single trigger pull and ensuring proper semi-automatic operation [

44]. In the Glock design, where the sear function is already integrated into the trigger bar, the disconnector function is fulfilled by the interaction between the connector and the cam surface in the slide. This represents another example of functional integration in the Glock system, reducing the number of required components.

The upward movement of the trigger bar is primarily driven by the trigger spring, which pulls the trigger bar backwards and upwards, thereby fully relaxing. However, there is a second mechanism by which the trigger bar can be moved upwards again. Once the connector releases the trigger bar, it can be moved a little further back (approx. 0,29 mm) by applying continued pressure on the trigger. Contact between the S-curve of the trigger bar and a polymer grip surface, inclined backward at approximately 10 degrees, causes the trigger bar to slide 1,65 mm upward along this incline during its rearward motion. This elevation raises its rear end by approximately 3,73 mm, enabling retention of the firing pin and cocking of the striker spring. Said mechanism allows the Glock to continue firing even with a broken trigger spring, provided that the trigger is consistently pressed rearward throughout the slide cycle.

5. Slide Return (Forward Movement)

Once the slide reaches its rearward stop, the compressed recoil spring starts to propel it forward. As the slide returns, the striker extension re-engages the rear end of the trigger bar, recompressing the striker spring.

6. Trigger Reset

Releasing the trigger allows the striker spring, via its extension engaging the trigger bar, to push the trigger bar forward. The forward movement of the trigger bar re-tensions the trigger spring while partially decompressing the striker spring. It also allows the connector to flex outwards back in place, bringing its cam surface back in the path of the trigger bar and thereby enabling the downward movement of the trigger bar with the subsequent trigger pull. This resets the trigger. The system is now back in the rest state, ready for the next cycle, with all three safeties being automatically re-engaged.

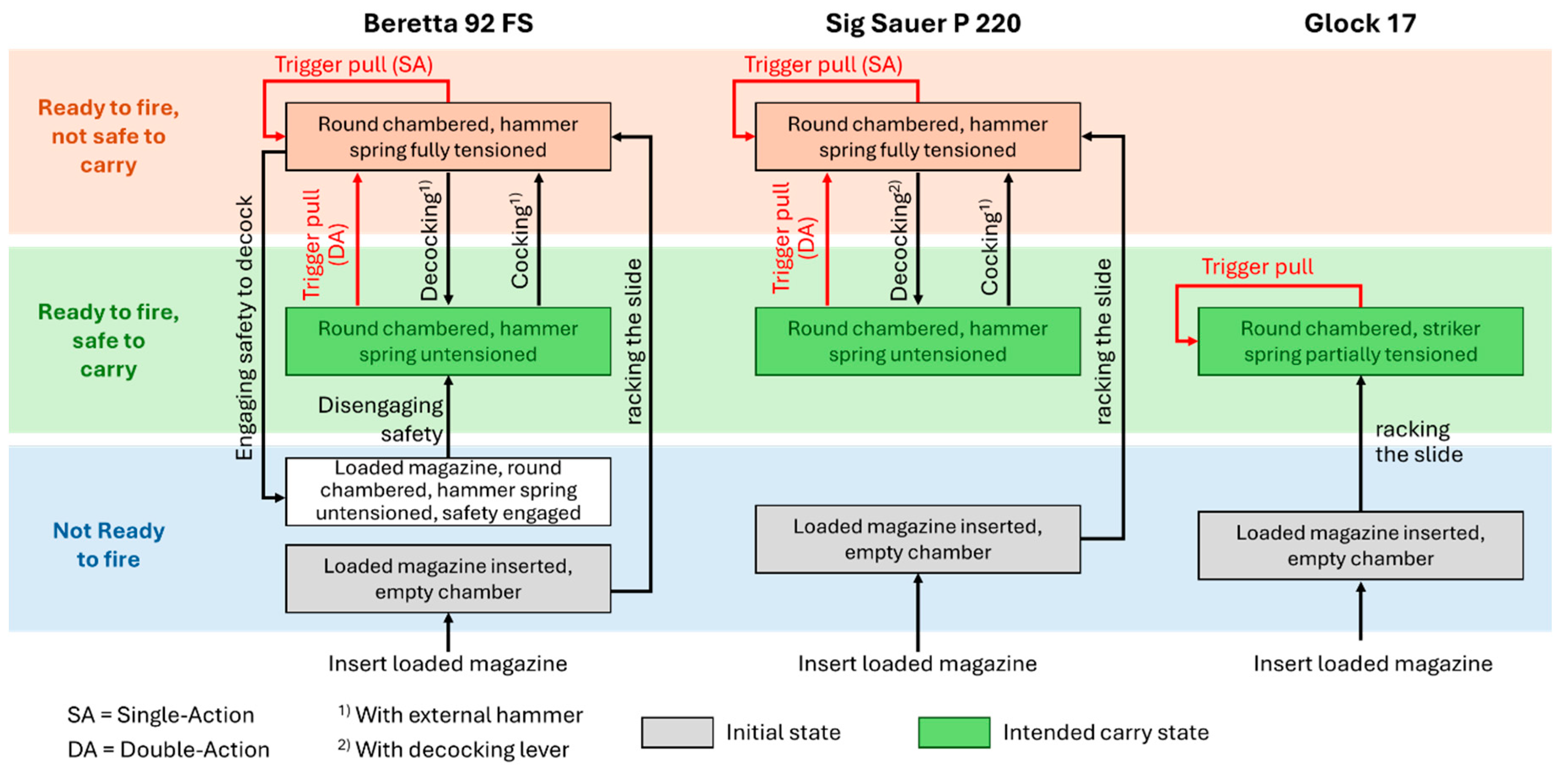

When comparing the usability of the Glock pistol to two widely used representatives of the DA/SA pistol concept that dominated the market at the time of Glock’s introduction – the Beretta 92FS and the Sig Sauer P220 – it becomes evident how significantly Glock’s operating concept improves usability.

Figure 12 illustrates the operational steps required to transition each pistol to its intended carry condition after inserting a loaded magazine, as well as their respective states after firing the first shot. The graphical representation clearly highlights differences in operational complexity. Unlike the Glock, both the Beretta and Sig Sauer require decocking after chambering a round and after firing a shot to ensure a safe carry condition. In the case of the Sig Sauer, which – like the Glock – lacks a manually operated safety, this is achieved via a decocking lever. The Beretta, equipped with a decocking safety, requires an additional step: after decocking the pistol using the safety lever, the safety must be disengaged by pushing the safety lever back up again to return the firearm to a ready-to-fire state. The Glock’s design eliminates these additional steps for the user and ensures that the firearm never enters an unsafe carry condition. This aligns with Thesis 7 from [

4], which posits that disruptive innovations redistribute tasks within the human-product interaction system by shifting responsibilities from the user to the product, thereby reducing the user’s cognitive and physical workload.

The Safe Action System, described in the previous section, also serves as the foundation for a striker-fired design that is neither a double-action-only system, such as the Heckler & Koch VP 70, nor a compromise in safety. Since the primary advantage of an external hammer – indicating the trigger system’s status (i.e., whether it is cocked or not) – is rendered obsolete by this system, and given the external hammer’s several disadvantages, such as potentially obstructing the draw of the weapon, there is no longer a functional justification for its implementation.

3.2. Reciprocal Enablers – Innovation Emergence Through Synergistic Linkages

In addition to its novel operating concept, Glock integrated several key technologies across the three fundamental domains that determine a physical product’s realization and value proposition: geometric layout, materials, and production processes. While most of these technologies had been previously used in firearms (

Figure 13), they had never been systematically integrated into a single system before. Their synergistic interaction led to a significant advancement in the usability of the Glock pistol as an emergent effect in line with systems theory. In this context, they function as “

reciprocal enablers” as defined by [

4]. In the following discussion of these reciprocal enablers, we will focus on those elements that were innovative, or at least unusual, in handgun design at the time of the Glock’s introduction, and that also contributed to its exceptional usability. Systems that were already widely adopted in other pistols, such as the modified Browning locked-breech short-recoil operating principle, will therefore not be analyzed in detail.

The most prominent feature of the Glock is the use of polyamide 66, a polymer material, for the pistol’s frame (

Figure 14). While the Glock pistol was not the first handgun to incorporate a polymer lower receiver, its adoption of this still-uncommon material at the time attracted the most public attention. Following its introduction, widespread debates emerged regarding the potential undetectability of polymer firearms at airports, inadvertently providing the Glock pistol with significant free publicity [

45]. Polymer materials offer several advantages over traditional metals in firearm construction. They are lightweight, cost-effective, corrosion-resistant, and possess greater elasticity than steel, allowing them to absorb some of the recoil energy. The choice of material also affects the domains of production process and geometric layout: polymers are inherently suited for injection molding, a manufacturing process that enables a high degree of design freedom and facilitates highly integrated product designs by allowing complex shapes to be produced cost-effectively. This integration reduces the number of components, minimizes assembly effort, and simplifies production. The high abrasion resistance required for the slide guide was achieved by casting in metal guides into the polymer frame. A key advantage of injection molding is its ability to create an ergonomically optimized grip as a single unit. Unlike metal pistol grips, which require additional grip panels, a polymer grip can maintain a slim profile even when accommodating a double-stack magazine, enhancing usability – particularly for individuals with smaller hands. Furthermore, the flexibility of the polymer frame allows it to compensate for minor tolerances in other mounted components, improving overall fit and function. As a result, the traditional trade-off between reliability and precision – where a pistol was either loose and reliable or tight and accurate but also prone to malfunctions – became obsolete.

Glock recognized manufacturing as the critical process through which a physical artifact is realized to meet customer needs. He optimized the design of his pistol for manufacturability to a level comparable to Toyota’s approach in the automotive industry. A notable example of this is the early adoption of CNC technology, which had only recently emerged in the late 1970s. The Glock slide is CNC-milled from a from a solid rolled-steel bar, with no welding or riveting, enabling a high degree of automation characterized by low labor costs and consistent quality. Additionally, this manufacturing approach allows for an advantage in the domain of the geometric layout: a further reduction in the number of individual parts, thereby minimizing assembly effort. Unlike designs such as the Colt M1911A1, the Glock slide features simple, straight lines, and its barrel consists of a rod with a rectangular chamber at the rear, eliminating the need to monitor complex tolerances during production (

Figure 15.

Aside from the firing pin, which is machined, most of the Glock’s internal components are stamped and bent, a process that facilitates the cost-effective mass production of complex geometric shapes, such as the trigger bar. This approach contributes to a highly integrated product design, further reducing the number of parts. Although stamped and bent parts exhibit lower structural strength compared to machined components, this limitation is offset by a design optimized for load path efficiency. These components are engineered and positioned within the frame to primarily withstand tensile and compressive forces, resulting in high strength and stiffness along the principal load direction. Additionally, the work hardening effect inherent in stamping and bending was deliberately leveraged in specific parts to enhance structural integrity. As a result, the design effectively balances cost-efficient mass production with durability.

Glock selected a polygonal barrel design, which can be manufactured without cutting through hammer forging. Compared to conventionally rifled barrels – then the standard in handguns – the polygonal design provides a superior gas seal, resulting in higher bullet muzzle velocities. Additionally, polygonal barrels exhibit significantly greater service life due to reduced wear.

Glock was also the first to introduce ferritic nitrocarburizing to the firearms industry, applying it to the slide and the barrel of his pistol. This process, commonly referred to in the context of Glock as “teniferation” (derived from a brand name for salt bath nitrocarburizing), significantly enhances the steel’s fatigue resistance, abrasion resistance, and corrosion resistance

7. At the time of the Glock pistol’s development, this technique was rarely used outside of high-end industrial applications, such as bearings, machine shafts, and machine-tool components [

29]. The significance of this innovation was highlighted by Patrick Sweeney in his book “

Glock Deconstructed”, where he remarked, “

We certainly have to tip our hats to Gaston Glock for seeing that an obscure industrial process such as this could be applied to firearms and improve them greatly.” [

29].

In summary, it can be said that Gaston Glock deliberately employed various manufacturing processes that were unusual at the time in the manufacture of handguns to enable the cost-effective realization of a highly integrated product design. The result was a pistol that was not only significantly lighter, more ergonomic, and more cost-effective than all competing products at the time, but had also significantly fewer parts, with only 34

8 parts, no screws and just two pivot pins. This small number of parts not only reduces the effort required for final assembly of the pistol but also significantly simplifies assembly and disassembly during use (“field strip”). Since the number of moving parts is a key determining factor for the reliability of a mechanical system, the small number of parts represents an important foundation for the reliability of the Glock pistol. Thus, from a design theory perspective, the Glock pistol demonstrates a significantly higher level of ideality, as defined by TRIZ, compared to all preceding competing models, thereby confirming Thesis 6 from [

4].

3.3. The Formal Aesthetics of the Glock Pistol

The design language of the Glock pistol is characterized by a plain minimalistic design conveying durability, simplicity and clarity through geometric reduction and its black color (

Figure 16). It is centered on ruggedness and functionality creating an austere purely purpose-driven technical aesthetic that speaks to strength and practicality. The design follows principles commonly seen in high-precision engineering, akin to industrial tools rather than traditional firearms. The Glock features a predominantly rectilinear form with clean, uninterrupted surfaces. The slide is a simple, box-like structure with straight, flat planes, avoiding unnecessary embellishments. The grip integrates subtle curvature for ergonomics but maintains an overall angular, utilitarian appearance. The overall appearance of the Glock very much resembles the bare minimum abstraction to symbolize a gun.

In [

46] graphic designer Jill Butler describes the design language of the Glock pistol as follows:

“If I were going to buy a gun, I would want it to look like this one. The Glock’s single-color plastic body, matte finish, lack of details, and simple shape say, ‘I own the fact that I am a powerful tool designed and built to intimidate, maim, or kill, and I do not take that responsibility lightly.’ The Glock looks serious, subdued, and respectful. And if I were going to shoot a gun, that’s how I would feel.”

The Glock’s distinctly utilitarian design carries a masculine connotation, significantly influencing its perception in segments of popular culture where hypermasculinity is central to identity, particularly in action films and rap music. Within this cultural framework, the Glock is often regarded as the antithesis of firearm designs that incorporate superfluous features or excessive ornamentation, which are sometimes perceived as less functional or even effeminate. This perception is exemplified in the 1998 film “U.S. Marshals”, in which the protagonist, Sam Gerard, critiques a fellow officer’s stainless-steel pistol, remarking: “

Get yourself a Glock and lose that nickel-plated sissy pistol!”. The succinct, one-syllable name “

Glock”, which rhymes with frequently used words in rap music, such as e.g., “

block” and “

cop”, has also served as a catalyst for the pistol’s numerous references in popular culture [

7]. The Glock pistol has become so ubiquitous in film and television that its image is now as recognizable as that of the Russian AK assault rifle, although the latter is depicted on several national flags and the Glock is not [

29].

5. Dominant Design and Disruptive Innovation: A New Model of Product Evolution

Analyses of the innovation cases of the first iPhone, described in [

4], and the Glock pistol revealed striking similarities in preceding environmental changes, innovation processes, and the characteristics of the resulting outcomes. Through a systematic abstraction of these cases, we developed a new model of product evolution with a specific focus on physical products. The model delineates the primary driving force behind product evolution and the interaction of various entities in the emergence and replacement of dominant designs. It is proposed as an initial framework to foster further academic discourse on physical product innovation.

The patterns of product evolution that drive the emergence and replacement of dominant designs within specific product categories have been studied extensively (cf. [

26,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66]). These studies primarily frame technological innovation as the principal driver of product evolution. However, they often fail to adequately account for the distinctive role of the design process as the central creative act through which abstract ideas and emerging technologies are transformed into tangible products. Moreover, as exemplified by the case of the Glock pistol, the innovation underlying newly established dominant designs often lies not in the use of novel technologies, but in the recombination of existing ones. The limited attention given to the design process in innovation research may stem from its disciplinary grounding in economic and organizational theory. Scientific analyses of the design process, by contrast, are typically situated within the field of engineering design. As a result, existing theoretical frameworks on product evolution often remain vague with respect to key concepts such as “

design” and “

performance,” lacking further differentiation or specification.

To understand design trajectories within a given product category, we consider it essential to differentiate the term “

design” into

conceptual and

embodiment design. The conceptual design represents the principle solution of a product and is defined by the working structure, i.e., the function carriers and their linkage along the solution-determining main flow of the product’s function structure. Each function carrier, in turn, is characterized by its working principle, determined by the physical effect it utilizes, along with its geometric and material properties [

67]. The conceptual design can be understood as the

qualitative design of a product that also determines its operational concept. The embodiment design, on the other hand, represents the

quantitative aspects of a product’s design. It encompasses the exact geometric layout and precise geometric specifications – including size, tolerances, surface texture, and quality – as well as the selection of materials and the constructional interrelationships within the product’s physical architecture.

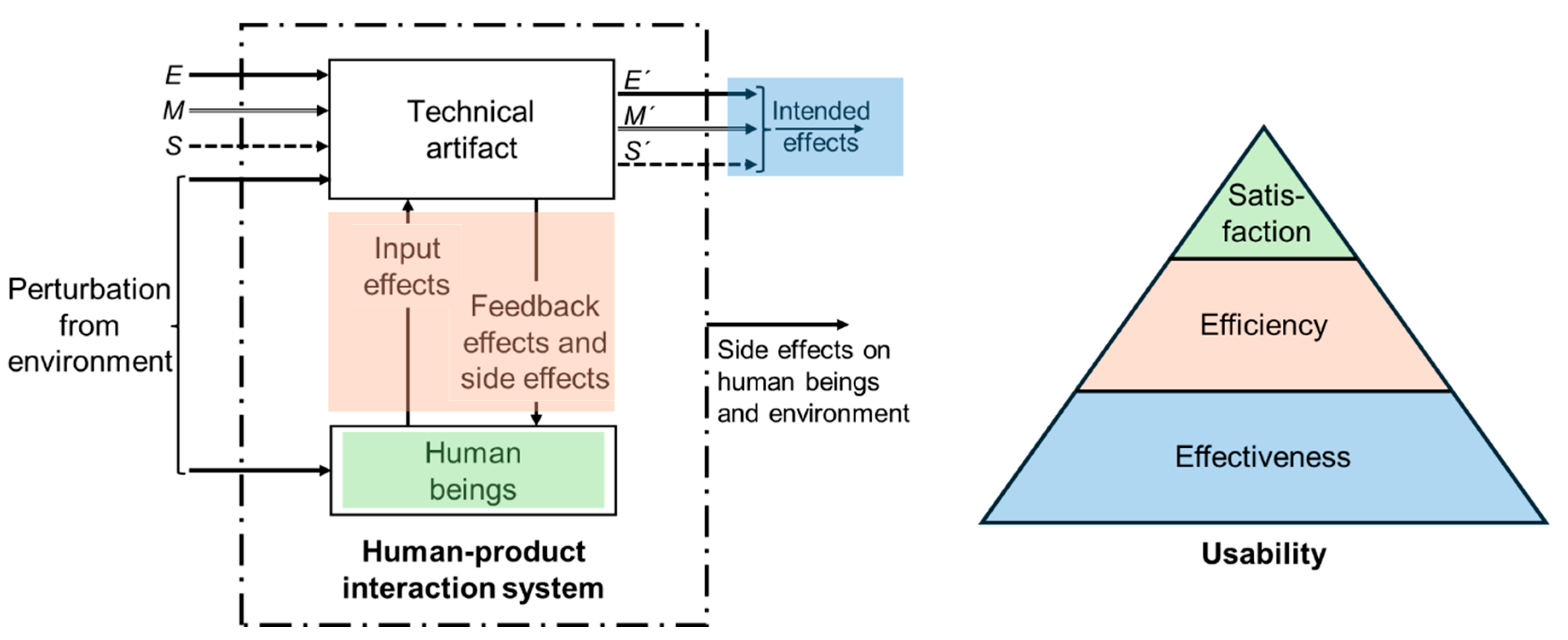

A physical product is a tangible artifact conceived, designed, and physically realized by humans to achieve specific goals through interaction with humans. No product operates completely on its own; it is always embedded within a human-product interaction system, where it is intended to fulfill the system’s overarching purpose – i.e., the intended effects – within a particular use context. The purpose of the human-product interaction system is inherently linked to a fundamental human need that transcends the specific use context. The extent to which a product is suited to achieving the intended purpose of the human-product interaction system is referred to as usability. Our analysis identifies usability as the core performance criterion governing product evolution. In periods of high conceptual uncertainty – commonly referred to as the “

era of ferment” in innovation theory (e.g., [

68]) – usability functions as the decisive fitness criterion in the evolutionary process through which a new dominant design is ultimately selected. According to [

69], usability consists of three distinct aspects:

- □

Effectiveness, which is the accuracy and completeness with which users achieve the specified goals, i.e., the intended effects of the human-product interaction system.

- □

Efficiency, which is the relation between resources expended and effectiveness.

- □

Satisfaction, which is “

the users’ comfort with and positive attitudes toward the use” [

70] of the product.

These aspects are not independent but hierarchically tiered. Effectiveness forms the foundation and is a necessary condition for usability. Without effectiveness, efficiency cannot be evaluated, as it is defined by the ratio of effectiveness to effort. Together, effectiveness and efficiency determine the practical value of a product. Satisfaction, by contrast, represents its emotional value, encompassing qualities such as formal aesthetic design and symbolic significance that contribute to the joy of use and pride of ownership. As products within a category converge in practical value, satisfaction increasingly becomes a key differentiator in competitive markets. This hierarchical relationship is illustrated in

Figure 27, which maps the usability aspects within the human-product interaction system.

Based on this definition, usability is not merely one product feature among many or an auxiliary design concern, but rather the overarching performance metric that indicates how effectively a product fulfills its intended purpose and supports users in achieving their goals. Unlike isolated technical specifications, usability integrates multiple dimensions of product performance – such as functionality, reliability, and efficiency – through the lens of user interaction. As such, it provides a holistic measure of a product’s success in real-world contexts. Regardless of domain or application, the degree to which a product is usable ultimately determines the extent to which it delivers value to its users.

All product development efforts ultimately aim to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency with which a product fulfills the intended goals of the human-product interaction system respectively the human needs that are inherently related to these goals. Therefore, we identify the gap between the usability demanded by users and the usability offered by existing products as the primary driver of product evolution. User expectations and satisfaction with existing solutions are highly dependent on both the technical and social environment, as these factors not only shape the context of use but also affect the goals that reflect the fulfillment of the underlying human needs.

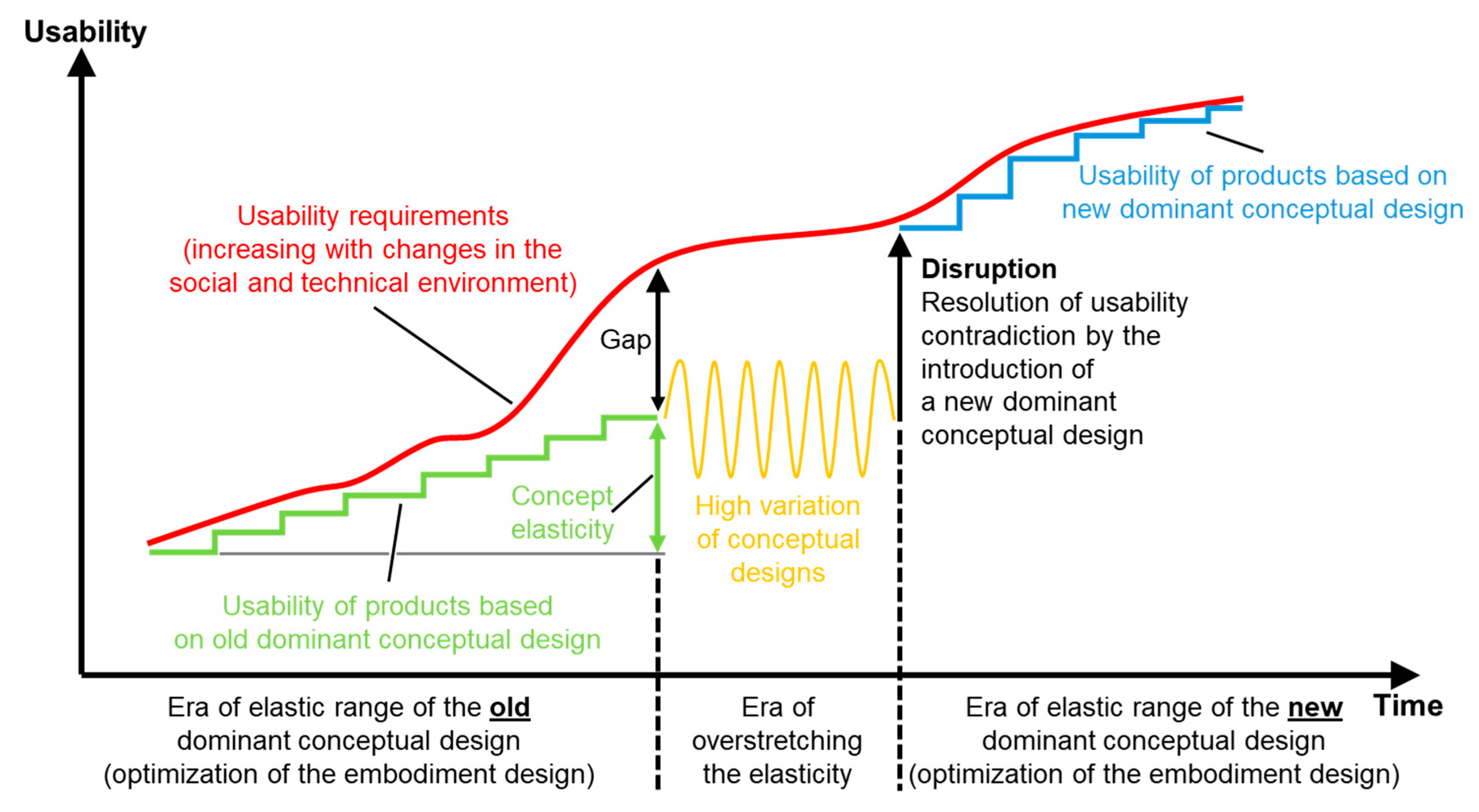

Product evolution becomes evident in the various designs that are developed and introduced, each exhibiting distinct usability characteristics. Both the conceptual design and the embodiment design contribute to a product’s overall usability. The conceptual design, which defines the working principles of the main function carriers and their linkage, reflects the foundational technology of the product and determines its basic use concept. As such, the conceptual design has a greater impact on usability than the embodiment design. While usability can be enhanced through optimization of the embodiment design, it is the conceptual design that sets the upper limit of achievable usability. Accordingly, a dominant design should be understood as a dominant conceptual design. The difference between the usability of a newly introduced product based on a novel conceptual design and the maximum usability attainable through optimizing its embodiment design is referred to in this paper as concept elasticity. Concept elasticity is analytically useful for understanding the performance potential embedded in a particular design trajectory. It allows us to distinguish between improvements that stem from refinement and those that require a fundamental rethinking of the product’s underlying use concept. As such, concept elasticity can explain why some dominant designs persist longer than others despite ongoing technical optimization.

As shown in

Figure 28, this paper’s model of product evolution entails a cyclical model comprising three phases:

1 – Era of the elastic range of the dominant conceptual design

In this era, increasing usability requirements can be met by evolving the embodiment design of the existing dominant conceptual design.

2 – Era of overstretching the elasticity of the dominant conceptual design

The limit of the existing dominant conceptual design’s elasticity is reached. The dominant conceptual design does not offer any further potential for usability improvement through changes in the embodiment design. The gap between required and available usability is constantly growing over time. Emerging user needs, driven by changes in both the technical and social environment, give rise to “

key usability contradictions” [

4] (cf. section 3.1) that cannot be resolved by products based on the existing dominant conceptual design. Said key usability contradictions trigger the era of ferment, characterized by the development of products implementing varying novel conceptual designs.

3 – Disruption of the dominant conceptual design

Ultimately, a novel conceptual design emerges that effectively resolves the key usability contradictions establishing itself as the new dominant conceptual design and supplanting (disrupting

11) the previous one. Products based on this novel conceptual design typically exhibit a higher degree of ideality, as defined by TRIZ, compared to those based on the prior dominant conceptual design [

4]. In physical products, a higher degree of ideality often manifests itself in reduced size and weight. Additionally, the new conceptual design usually redistributes tasks within the human-product interaction system, shifting responsibilities from the user to the product and thereby reducing the user’s cognitive and physical workload [

4].

In the case of handguns, the central role of usability in product evolution is also evident in the widespread adoption of Glock’s operating concept in striker-fired polymer frame pistols developed by competing manufacturers. Due to patent constraints, these manufacturers were required to modify certain aspects of the trigger mechanism. In many of the resulting designs, the striker spring is fully tensioned after each shot, effectively rendering them single-action pistols without manually actuated safeties

12. However, during the trigger pull, the user must overcome additional springs that mechanically impede access to the energy stored in the striker spring. Viewed through the lens of systems theory, this approach constitutes a functional inversion of Glock’s counteracting spring mechanism, aimed at reproducing the same usability.

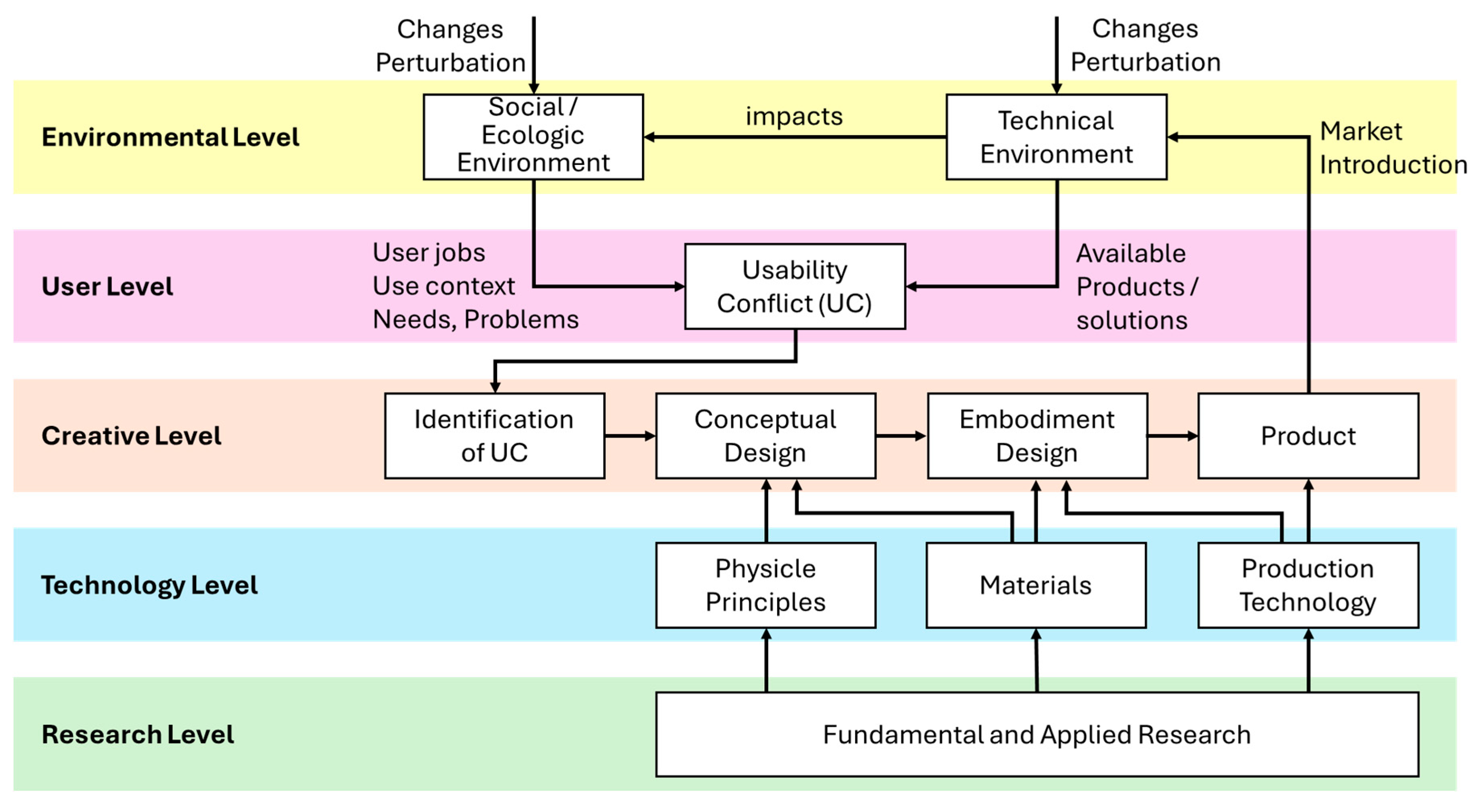

The interactions among various entities that culminate in the evolutionary pattern depicted in

Figure 28 are conceptualized within a five-level model, illustrated in

Figure 29. At the heart of this model is the creative level, which serves as a mediating level between two domains: the environmental and user level on one side, and the research and technology level, encompassing the fundamental body of knowledge, on the other.

New products emerge from activities at the creative level, which may be undertaken by individuals, companies, or organizations. The process typically begins with a comparison performed by the creative entity – between the demands imposed by tasks, needs, problems, and the contexts of use, and the technical solutions currently available at the user level. As the discrepancy between required and provided usability increases, the likelihood that this will trigger an impulse to initiate the development of a new product correspondingly rises.

This comparative process also occurs, often implicitly, in the case of technology push scenarios. In such instances, the creative entity must recognize that a new technological capability enables the development of products that offer substantially improved usability compared to existing solutions – thereby better addressing the human needs embedded in the human-product interaction system.

The development of a new product consistently requires the creative entity to navigate two critical stages

Figure 30:

- (1)

Assessment: The creative entity must determine whether the increased usability necessitated by evolving environmental conditions can be achieved through an advancement of the existing embodiment design based on the dominant conceptual design, or whether a completely new conceptual design is required.

- (2)

Solution Development: The appropriate solution must then be conceived and realized. If a new conceptual design is necessary, its development constitutes a significant act of creative innovation – one marked by high complexity and considerable challenges in successful implementation.

However, our model also suggests that as the gap between required usability and that offered by existing products widens, the likelihood of resolving the underlying usability contradiction increases. This is because the growing disparity generates a stronger impulse for action at the creative level, mobilizing more actors to engage in the problem and attracting greater resources toward its resolution. To put it plainly: even if Gaston Glock had not undertaken the development of a new pistol in the early 1980s, a similar dominant conceptual design featuring the same operating principle would likely have emerged. The breakthrough for this disruptive innovation would then have been reached by another creative entity at a later stage.

6. Summary and Conclusion

This study set out to investigate why the Glock pistol evolved into the dominant design for modern handguns, and how Gaston Glock, despite lacking prior experience in firearm design, succeeded in developing it. Three core research questions guided the analysis: (1) identifying the distinct features that made the Glock the world’s most successful handgun, (2) understanding the unique development process behind its creation, and (3) deriving broader insights for theories of disruptive product innovation.

The research revealed that the Glock pistol successfully addressed a long-standing usability contradiction in handgun design: combining the firepower and rapid reload capabilities of semi-automatic pistols with the operational simplicity and safety of double-action revolvers. This was achieved through the development of the Safe Action System, centered around a partially preloaded striker mechanism, a trigger spring to assist the trigger pull, and a trigger bar with a high degree of functional integration. The Glock was the first pistol that, once chambered, remained both ready to fire and safe to carry at all times, with a consistent trigger pull optimized for both safety and performance – light enough to enable rapid and accurate shooting, yet sufficiently heavy to minimize the risk of accidental discharge.

Three key aspects enabled the resolution of this usability contradiction. First, Glock pursued an unbiased, solution-neutral approach to the design challenge, unencumbered by existing manufacturing constraints or cognitive solution fixations. Second, he conducted a rigorous exploration of the problem space, guided by stringent user-centeredness, which allowed him to develop a deep understanding of user needs and the limitations of existing pistol designs. Third, the development process was prototype-driven and iterative, enabling the co-evolution of problem understanding and technical solution. By continuously testing prototypes and integrating feedback, Glock was able not only to deepen his understanding of the problem but also to converge iteratively on a radically new conceptual solution. This process was further enhanced by the strategic use of functional integration and emerging manufacturing technologies, resulting in a firearm that was lighter, simpler, more reliable, and more cost-effective than its contemporaries.

The Glock’s emergence as a dominant design did not hinge on a single technological breakthrough, but on the systematic resolution of a core usability contradiction through an iterative, user-centered design process. The final design introduced a novel operating principle and integrated multiple technologies that had not previously been combined in a single firearm. These technologies functioned as “reciprocal enablers”, collectively driving the superior usability of the Glock pistol. The case provides valuable lessons for innovation management and engineering design, demonstrating that disruptive innovations can emerge even in mature and highly competitive industries – when development is grounded in disciplined openness to user needs and technical possibilities.

Building on these findings, this study proposes a new generic model of product evolution for physical products. The model frames the gap between user-required and product-delivered usability as the primary driver of product evolution. It distinguishes between conceptual and embodiment design and introduces five interacting levels that govern product development. The creative level serves as a mediator between the user/environmental level and the knowledge base of research and technology. As the usability gap widens, the pressure for innovation grows, prompting creative activity. A central challenge is determining whether improved usability can be achieved through refinement of existing embodiments or whether it requires a new conceptual design. This model provides an initial framework for analyzing disruptive innovation in physical products and invites further academic exploration.

Future research on disruptive product innovations should extend beyond the study of technological discontinuities and competitive dynamics. To better understand how such innovations arise and take hold, it is essential to investigate the conceptual design of products and its role in shaping the product’s usability. This line of inquiry enables deeper analysis of the interactions among the five levels of the proposed model. One promising avenue is the early identification of usability contradictions driven by environmental change, and the proactive resolution of these contradictions within the design process.