Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Firstly, the multilayer concept ensured the contour coating profile (i.e., uniform fibre coverage and low variations in coating thickness) and fewer defects in the coating layer;

- Secondly, premature skin formation and blistering drying are decreased with (a) re-duction in the amount of water to be evaporated in infrared (IR) driers as a consequence of multiple coatings with thin, individual layers and (b) a reduction in IR drying power due to the thin, individual layers. This hypothesis is supported by observations of the influence of drying presented elsewhere [60,73].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Barrier Dispersion

2.2.2. Pilot Coating

- One electric infrared (IR) dryer containing 12 individual IR elements, distributed as 6 elements on each side of the web, where the total installed power was 1036 kW, i.e., 86.3 kW per individual IR element, and the total length of the electric IR dryer was 3.6 m;

- One air turn of radius 0.4 m, not formally classified as a dryer, located between the IR dryer and airfloat dryers, where the air turn has some minor effect on the drying process;

- Three airfloat drying hoods, with a maximum temperature of 300°C.

- Series A: low IR power and high air hood temperature;

- Series B: medium IR power and low air hood temperature.

| Sample Name | Number of Layers | Total (Accumulated) Coat Weight (g/m2) | IR Power (%) |

Number of Active IR Elements |

Drying Hood #1 (°C) |

Drying Hood #2 (°C) |

Drying Hood #3 (°C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base paperboard | |||||||

| BASE | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Series A—IR 20% | |||||||

| A1 | 1 | 1.5 | 20 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| A2 | 2 | 2.5 | 20 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| A3 | 3 | 3.5 | 20 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| A4 | 4 | 4.1 | 20 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| A5 | 5 | 4.6 | 20 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| A6 | 6 | 5.1 | 20 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| Modified Series A—IR 80% | |||||||

| MA2 | 2 | 2.5 | 80 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| MA3 | 3 | 3.5 | 80 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| Series B—IR 40% | |||||||

| B1 | 1 | 1.4 | 40 | 12 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| B2 | 2 | 2.4 | 40 | 12 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| B3 | 3 | 3.05 | 40 | 12 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| B4 | 4 | 3.70 | 40 | 12 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| B5 | 5 | 4.30 | 40 | 12 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| B6 | 6 | 4.75 | 40 | 12 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Modified Series B—IR 40%—half of the IR elements are active | |||||||

| MB6 | 6 | 4.75 | 40 | 6 | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Reference thick single coating | |||||||

| RSA1 | 1 | 5.4 | 80 | 12 | 250 | 250 | 60 |

| RSB1 | 1 | 5.4 | 99 | 12 | 250 | 250 | 60 |

| Reference thick double coating | |||||||

| RDA1 | 1 | 3.7 | 55 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| RDA2 | 2 | 6.8 | 20 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| RDB1 | 1 | 3.9 | 80 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

| RDB2 | 2 | 7.0 | 80 | 12 | 200 | 200 | 60 |

2.2.3. Analyses of Coated Paperboard

Pinholes

Surface Structure—Air Flow Method

Profilometry—Images, Roughness and Void Volume

Grease Resistance

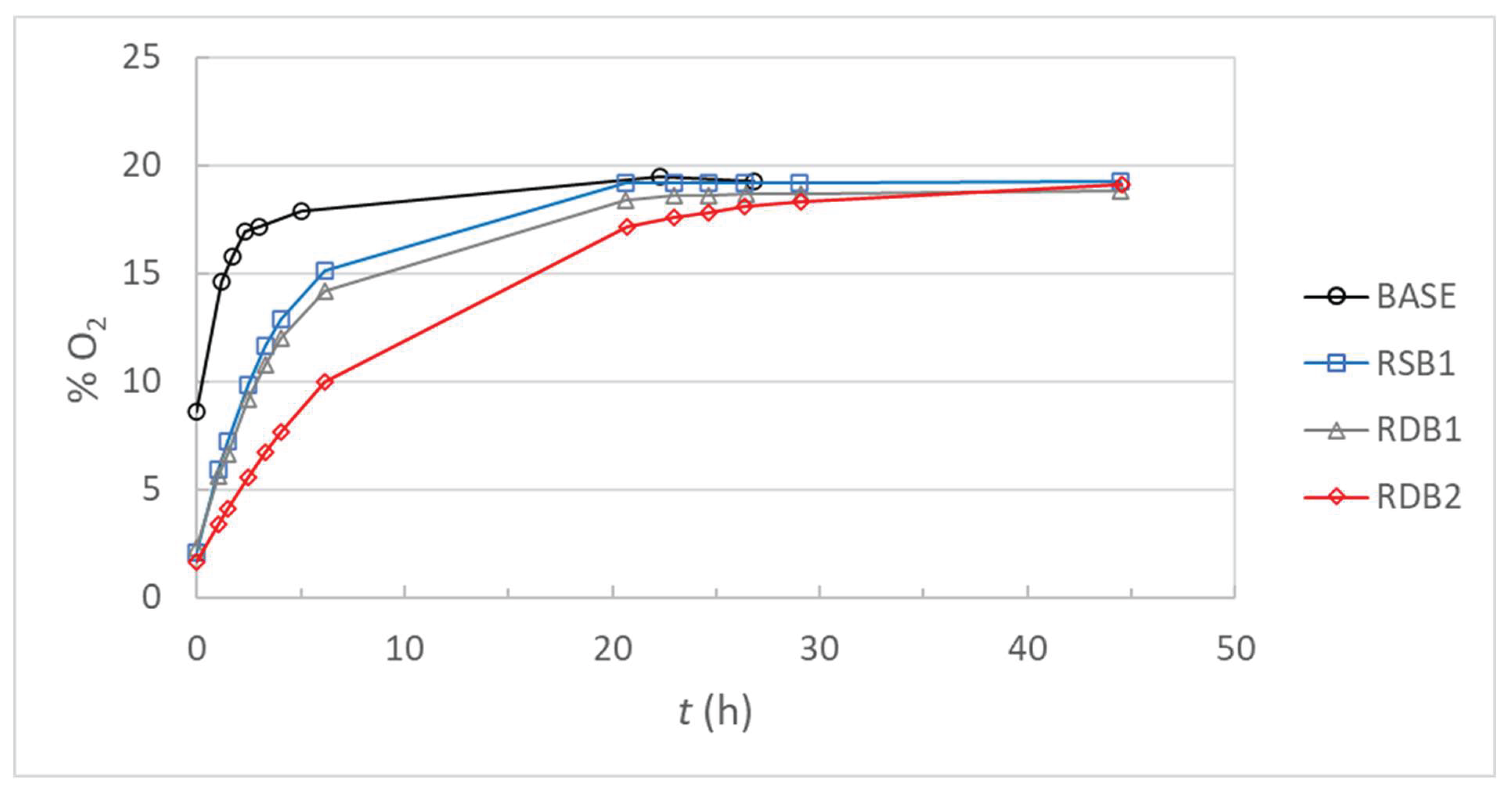

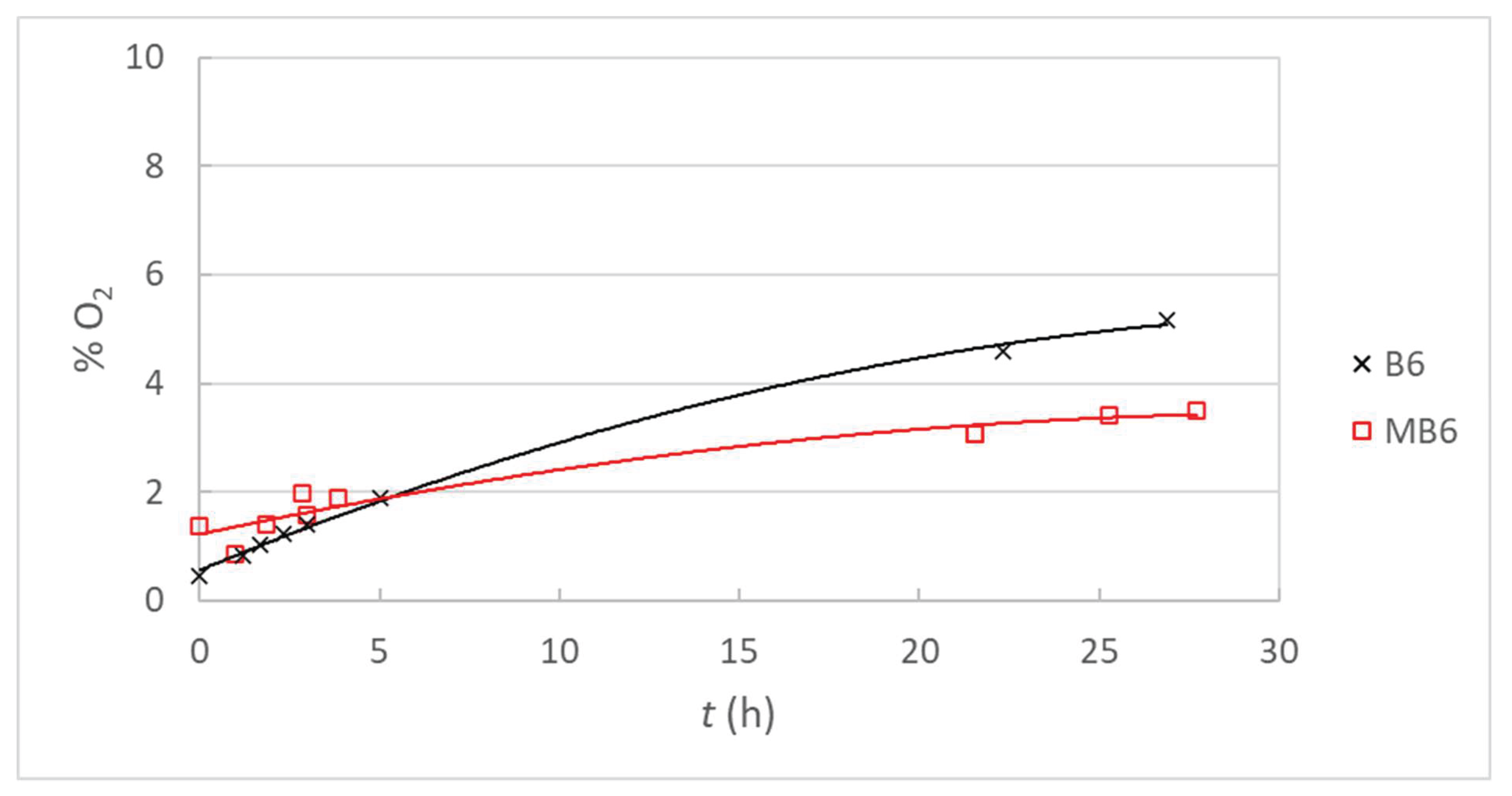

Oxygen Transmission

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Pinholes and Surface Structure

- (1)

- Sample MA3 was excluded from the test protocol due to severe blistering.

3.2. Grease Resistance and Oxygen Barrier Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andersson, C. New ways to enhance the functionality of paperboard by surface treatment – a review. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2008, 21, 339-373. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, P.; Salem, K.S.; Hubbe, M.A.; Lokendra, P. Advances in barrier coatings and film technologies for achieving sustainable packaging of food products – A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 115, 461-485. [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, M.; Bertelsen, G. Predicting the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed in meat. Meat Sci. 2004, 68(4), 603-610. [CrossRef]

- Matar, C.; Gaucel, S.; Gontard, N.; Guilbert, S.; Guillard, V. Predicting shelf life gain of fresh strawberries ‘Charlotte cv’ in modified atmosphere packaging. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2018, 142, 28-38. [CrossRef]

- Jalali, A.; Linke, M.; Geyer, M.; Mahajan, P.V. Shelf life prediction model for strawberry based on respiration and transpiration processes. Food Packag. Shelf Life 2020, 25, 100525. [CrossRef]

- Bristow, J.A. The Pore Structure and the Sorption of Liquids. In Paper Structure and Properties; Bristow, J.A., Kolseth, P., Eds.; Marcel Dekker, New York, 1986, pp. 183-201. ISBN 0-8247-7560-0.

- Zhang, W.; Liu, W.; Li, H.; Hubbe, M.A.; Yu, D.; Li, G.; Wang, H. Improving Stability and Sizing Performance of Alkenylsuccinic Anhydride (ASA) Emulsion by Using Melamine-Modified Laponite Particles as Emulsion Stabilizer. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 12330-12338. [CrossRef]

- Lindström, T.; Larsson, P.T. Alkyl Ketene Dimer (AKD) sizing – a review. Nordic Pulp Paper Res. J. 2008, 23(2), 202-209. [CrossRef]

- Hubbe, M A. Paper's resistance to wetting - A review of internal sizing chemicals and their effects. BioResources 2007, 2(1), 106-145.

- Li, H.; Liu, W.; Yu, D.; Song, Z. Anchorage of ASA on cellulose fibers in sizing development. Nordic Pulp Paper Res. J. 2015, 30(4), 626-633. [CrossRef]

- Seppänen, R. On the internal sizing mechanisms of paper with AKD and ASA related to surface chemistry, wettability and friction, PhD Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden, 2007.

- Lindström, T. Sizing. In Volume 3 Paper Chemistry and Technology; Ek, M., Gellerstedt, G., Henriksson, G., Eds.; De 671 Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2009, p. 301. [CrossRef]

- Engström, G. Pigment Coating. In Volume 3 Paper Chemistry and Technology; Ek, M., Gellerstedt, G., Henriksson, G., Eds.; De 671 Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2009, pp. 374-375. [CrossRef]

- Furuheim, K.M.; Axelson, D.E.; Helle, T. Oxygen barrier mechanisms of polyethylene extrusion coated high density papers. Nord. Pulp Paper Res. J. 2003, 18(2), 168-175. [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, L.; Stenström, S. Gas diffusion through sheets of fibrous porous media. Chem. Eng. Sci. 1995, 50(3), 361-371. [CrossRef]

- Neilen, M.; Bosch, J. (2007). Tubular LDPE has the extrusion coating future. In Proceedings of the 11th TAPPI European PLACE Conference, Athens, Greece, 14-16 May 2007, TAPPI Press, Atlanta, GA, USA, pp. 87-96.

- Kjellgren, H.; Stolpe, L.; Engström, G. Oxygen permeability of polyethylene-extrusion-coated greaseproof paper., Nordic Pulp Paper Res. J. 2008, 23(3), 272-276. [CrossRef]

- Tuominen, M.; Lahti, J.; Kuusipalo, J. Effects of flame and corona treatment on extrusion coated paper properties. Tappi J. 2011, 10(10), 29-37.

- Putkisto, K.; Maijala, J.; Grön, J.; Rigdahl, M. Polymer coating of paper using dry surface treatment: Coating structure and performance. Tappi J. 2004, 3(11), 16-23.

- Dhoot, S.N.; Freeman, B.D.; Stewart, M.E. Barrier Polymers. In Encyclopedia of Polymer Science and Technology, 4th ed.; Wiley Online Library: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Kuusipalo, J. Starch-Based Polymers in Extrusion Coating. J. Polym. Environ. 2001, 9, 125–135. [CrossRef]

- Lahtinen, K., Kotkamo, S., Koskinen, T., Sanna Auvinen, S., Kuusipalo, J. Characterization for Water Vapour Barrier and Heat Sealability Properties of Heat-treated Paperboard/Polylactide Structure, Packag. Technol. Sci. 2009, 22, 451–460. [CrossRef]

- Sängerlaub, S., Brüggemann, M., Rodler, N., Jost, V., Bauer, K.D. Extrusion Coating of Paper with Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate) (PHBV)—Packaging Related Functional Properties. Coatings 2019, 9, 457. [CrossRef]

- Kogler, W.; Tietz, M.; Auhorn, W.J. Paper and Board, 7. Coating of Paper and Board. In Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 7th ed.; Wiley Online Library, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Renvall, S.; Kuni, S. Coat weight control in bent blade mode. Tappi J. 2013, 12(5), 31-38.

- Engström, G.; Rigdahl, M. Literature review: Binder migration - Effect on printability and print quality. Nordic Pulp Paper Res. J. 1992, 7(2), pp. 55-74. [CrossRef]

- Rückert, H. VARI-BAR: Ein System zur Regelung des Strichgewichts als Ergebnis der Weiterentwicklung der bekannten Rollschabereinrichtungen, Wochenblatt Papierfabr. 1982, 110(13), 461-464.

- Hanumanthu, R., Scriven, L.E. Coating with patterned rolls and rods. Tappi J. 1996, 79(5) 126-138.

- Klass, C.P.; Åkesson, R. Development of the metering size press: A historical perspective. In Proceedings of the TAPPI Metered Size Press Forum, Nashville, TN, USA, 16–18 May 1996; pp. 1–12.

- Schweizer, P.M. Stability of Liquid Curtains. In Proceedings of the PITA Coating Conf., Edinburgh, UK, 4-5 March 2003, pp. 103-111.

- Larsson, J.; Karlsson, A. Coating composition, a method for coating a substrate, a coated substrate, a packaging material and a liquid package. US Patent US 2014/0251856 A1, 11 September 2014.

- Döll, H. Curtain coating for paper industry – Single and multilayer. In Proceedings of the TAPPI PaperCon Paper Conference and Trade Show, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 23-26 April 2017.

- Husband, J.C.; Hiorns, A.G. The trend towards low impact coating of paper and board. In Proceedings of the 6th European Coating Symposium, Bradford, UK, 7-9 September 2005, pp. 1-10.

- Kumar, V.; Elfving, A.; Koivula, H.; Bousfield, D.; Toivakka, M. Roll-to-roll processed nanocellulose coatings for barriers applications. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2016, 55(12), 3603-3613. [CrossRef]

- Ruberto, Y; Vivod, V.; Grkman, J.J.; Lavrič, G.; Graiff, C.; Kokol, V. Slot-die coating of cellulose nanocrystals and chitosan for improved barrier properties of paper. Cellulose 2024, 31, 3589–3606. [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen-Raudaskoski, K.; Hjelt, T.; Koskela, H.; Forsström, U.; Sadocco, P.; Causio, J.; Baldi, G. (2015). Thin barrier and other functional coatings for paper by foam coating, TAPPI PaperCon Paper Conference and Trade Show (Proc.), April 19-22 2015, Atlanta, GA, USA.

- Gómez-Estaca, J.; Gavara, R.; Catalá, R.; Hernández-Muñoz, P. (2016). The Potential of Proteins for Producing Food Packaging Materials: A Review, Packag. Technol. Sci. 2016, 29, 203-224. [CrossRef]

- Kimpimäki, T.; Savolainen, A.V. Barrier dispersion coating of paper and board. In Surface Applications of Paper Chemicals; Brander, J. and Thorn, I., Eds; Springer, Dordrecht, the Netherlands, 1997, pp 208-228. [CrossRef]

- Vähä-Nissi, M.; Savolainen, A.; Talja, M.; Mörö, R. Dispersion barrier coating of high-density base papers, Tappi J. 1998, 81(11), 165-173.

- Andersson, C.; Järnström, L; Hellgren, A.-C. Effects of carboxylation of latex on polymer interdiffusion and water vapor permeability of latex films, Nordic Pulp Paper Res. J. 2002, 17(1), 20-28. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, C.; Ernstsson, M.; Järnström, L. Barrier properties and heat sealability/failure mechanisms of dispersion-coated paperboard. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2002, 15(4), 209-224. [CrossRef]

- Mehravar, E.; Leiza, J.R.; Asua, J.M. Performance of latexes containing nano-sized crystalline domains formed by comb-like polymers. Polymer 2016, 96, 121–129. [CrossRef]

- Burgess, S.K.; Karvan, O.; Johnson, J.R.; Kriegel R.M.; Koros, W.J. Oxygen sorption and transport in amorphous poly(ethylene furanoate). Polymer 2014, 55(18), 4748-4756. [CrossRef]

- Idris, A.; Muntean, A.; Mesic, B.; Lestelius, M.; Javed, A. Oxygen Barrier Performance of Poly(vinyl alcohol) Coating Films with Different Induced Crystallinity and Model Predictions. Coatings 2021, 11, 1253. [CrossRef]

- Guinault, A.; Sollogoub, C.; Domenek, S.; Grandmontagne, A.; Ducruet, V. Influence of crystallinity on gas barrier and mechanical properties of PLA food packaging films. Int. J. Mater. Form. 2010, 3(1), 603–606. [CrossRef]

- Jansson, A.; Järnström, L. Barrier and mechanical properties of modified starches. Cellulose 2005, 12, 423–433. [CrossRef]

- Rindlav-Westling, Å.; Stading, M.; Hermansson, A.-M.; Gatenholm, P. Structure, mechanical and barrier properties of amylose and amylopectin films, Carbohydr. Polym. 1998, 36, 217-224. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Tang, K.; Qin, G.; Chen, Y.; Peng, L.; Wan, X.; Xiao, H.; Xia, Q. Hydrogen bonding energy determined by molecular dynamics simulation and correlation to properties of thermoplastic starch films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 166, 256–263. [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, P.; Kippenhahn, R.; Luck, T.; Schönweitz, C. Mehrschichtige Verpackung für fettende Güter, European Patent EP 1 296 790 B1, 25 February 2004.

- Ovaska, S.-S.; Geydt, P.; Österberg, M.; Johansson, L.-S.; Backfolk, K. Heat-Induced changes in oil and grease resistant hydroxypropylated-starch-based barrier coatings. Nordic Pulp Paper Res. J. 2015, 30(3), 488-496. [CrossRef]

- Stading, M.; Rindlav-Westling, Å.; Gatenholm, P. Humidity-induced structural transitions in amylose and amylopectin films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2001, 45, 209-217. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, J.K.; Singh, R.P. Green Nanocomposites from Renewable Resources: Effect of Plasticizer on the Structure and Material Properties of Clay-filled Starch. Starch/Stärke 2005, 57(1), 8-15. [CrossRef]

- Mondragón, M.; Mancilla, J.E.; Rodríguez-González, F.J. Nanocomposites from plasticized high-amylopectin, normal and high-amylose maize starches. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2008, 48, 1261-1267. [CrossRef]

- Johansson, C.; Järnström, L.; Breen, C. Biopolymer based barrier material and method for making the same, PCT Patent WO 2010/077203 A1, 8 July 2010.

- Breen, C.; Clegg, F.; Thompson, S.; Jarnstrom, L.; Johansson, C. Exploring the interactions between starches, bentonites and plasticizers in sustainable barrier coatings for paper and board. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 183, 105272. [CrossRef]

- Yano, K.; Usuki, A.; Okada, A.; Kurauchi, T.; Kamigaito, O. Synthesis and properties of polyimide–clay hybrid. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 1993, 31(10), 2493–2498. [CrossRef]

- Yano, K.; Usuki, A; Okada, A. (1997), Synthesis and properties of polyimide-clay hybrid films. J. Polym. Sci. A Polym. Chem. 1997, 35(11), 2289-2294. [CrossRef]

- Weigl, J.; Laber. A.; Bergh, N.-O.; Ruf, F. Oberflächenbehandlung durch Pigmentierung. Wochenblatt Papierfabr. 1995, 123(14/15), 634-645.

- Hlavatsch, J.; Wechselberger, D.; Ruf, F. Streichbentonite – Neuentwicklung mit Perspektive? Wochenblatt Papierfabr. 1997, 125(11/12), 588-594.

- Guezennec, C. Development of New Packaging Materials Based on Micro- and Nano-Fibrillated Cellulose. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Grenoble, Grenoble, France, 2012; pp. 196–246.

- Al-Turaif, H.; Lepoutre, P. Evolution of surface structure and chemistry of pigmented coatings during drying. Prog. Org. Coat. 2000, 38(1), 43-52. [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Rättö, P.; Järnström, L.; Ullsten, H. Lignin-Containing Coatings for Packaging Materials—Pilot Trials. Polymers 2021, 13, 1595. [CrossRef]

- Christophliemk, H.; Bohlin, E.; Emilsson, P.; Järnström, L. Surface Analyses of Thin Multiple Layer Barrier Coatings of Poly(vinyl alcohol) for Paperboard. Coatings 2023, 13(9), 1489. [CrossRef]

- Pignères E.; Gaucel,S.; Coffigniez, F.; Gontard, N.;, Baghe, E.; Lyannaz, L.; Martinez, P.; Guillard, V.; Angellier-Coussy, H. Deciphering the respective roles of coating weight and number of layers on the mass transfer properties of polyvinyl alcohol coated cardboards. Prog. Org. Coat. 2024, 195, 108627. [CrossRef]

- Tanninen, P., Lindell, H., Saukkonen, E., Backfolk, K. (2014). Thermal and mechanical durability of starch-based dual polymer coatings in the press forming of paperboard. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2014, 27(5), 353-363. [CrossRef]

- Menzel, C.¸Koch, K. Impact of the coating process on the molecular structure of starch-based J. Polym. Environ Olsson, E.; Johansson; C.; Larsson. J.; Järnström, L. (2014). Montmorillonite for starch-based barrier dispersion coating — Part 2: Pilot trials and PE-lamination. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 97-98, 167-173. [CrossRef]

- Olsson, E.; Johansson, C.; Larsson. J.; Järnström, L. Montmorillonite for starch-based barrier dispersion coating — Part 2: Pilot trials and PE-lamination. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 97–98, 167–173. [CrossRef]

- Weigl, J.; Grossmann, H. Investigation into the Runnability of Coating Colors at the Blade at High Production Speed. In Proceedings of the 1996 TAPPI Coating Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–22 May 1996; pp. 311–320.

- Kuusipalo, J. PHB/V in Extrusion Coating of Paper and Paperboard—Study of Functional Properties. Part II. J. Polym. Environ. 2000, 8, 49–57. [CrossRef]

- Mesic, B.; Järnström, L.; Johnston, J. Latex-based barrier dispersion coating on linerboard: Flexographic multilayering versus single step conventional coating technology. Nordic Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2015, 30, 350–360. [CrossRef]

- Emilsson, P.; Larsson, T.; Järnström, L. Multiple barrier application for improved overall efficiency. In Proceedings of the PTS Coating Symposium, Papiertechnische Stiftung PTS, Munich, Germany, 16–17 September 2015; pp. 343–359.

- Olsson, E.; Johansson, C.; Järnström, L; Montmorillonite for starch-based barrier dispersion coating — Part 1: The influence of citric acid and poly(ethylene glycol) on viscosity and barrier properties. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 97–98, 160–166. [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, W. Drying of Functional Coatings. In Proceedings of the PTS Coating Symposium, Papiertechnische Stiftung PTS, Bamberg, Germany, 13–14 September 2023; p. 1.8.

- Alam, A.; Thim, J.; Manuilskiy, A.; O’Nils, M.; Westerlind, C.; Lindgren, J.; Lidén, J. MECHANICAL PULPING: Investigation of the surface topographical differences between the Cross Direction and the Machine Direction for newspaper and paperboard. Nordic Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2011, 26, 468-475. [CrossRef]

- Nyflött, Å.; Axrup, L.; Carlsson, G.; Järnström, L.; Lestelius, M.; Moons, E.; Wahlström, T. Influence of kaolin addition on the dynamics of oxygen mass transport in polyvinyl alcohol dispersion coatings. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2015, 30, 385–392. [CrossRef]

- Larsen, H., Kohler, A., Magnus, E.M. Ambient oxygen ingress rate method — An alternative method to Ox-Tran for measuring oxygen transmission rate of whole packages, Packag. Technol. Sci. 2000, 13, 233-241. [CrossRef]

- Lourdin, D.; Colonna, P.; Ring, S.G. Volumetric behaviour of maltose-water, maltose-glycerol and starch-sorbitol-water systems mixtures in relation to structural relaxation. Carbohydr. Res. 2003, 338, 2883-2887. [CrossRef]

- Uddin, F. Clays, Nanoclays, and Montmorillonite Minerals. Metall Mater Trans A 2008, 39, 2804–2814. [CrossRef]

- Jäder, J.; Engström, G. Frequency analysis evaluation of base sheet structure in a pilot coating trial using different thickener systems. Nordic Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2004, 19(3), 360-365. [CrossRef]

- Larsson, T.; Emilsson, P. Optimization of coating with water-based barriers. Tappi J. 2019, 18(2), 111–118.

- Hedman, A.; Gron, J.; Rigdahl, M. Coating layer uniformity as affected by base paper characteristics and coating method. Nordic Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2003, 18(3), 333-343. [CrossRef]

- Trinh, B.M.; Chang, B.P.; Mekonnen, T.H. The barrier properties of sustainable multiphase and multicomponent packaging materials: A review. Prog. Mater Sci. 2023, 133, 101071. [CrossRef]

| Component |

Dry Solid Content (%) |

Dry Mass (kg) |

Coating Formulation (pph) |

| Bentonite, aqueous suspension | 8.5 | 26.6 | 100 |

| Bentonite, powder | 92.5 | 3.8 | |

| Starch, aqueous solution | 26 | 76.7 | 252 |

| PEG 600 (liquid) | 100 | 15.3 | 50 |

| Symbol | Name | Description |

| Sa | Average roughness over a measurement area | Arithmetic mean of the absolute values of the surface departures from the mean plane. |

| Sc | Core void volume | This parameter is derived from bearing analyses and expresses the volume (e.g., of a fluid filling the core surface) that the surface would support from 10% to 80% of the bearing area ratio. |

| Sv | Surface void volume | This parameter is derived from bearing analyses and expresses the volume (e.g., of a fluid filling the valleys) that the surface would support from 80% to 100% of the bearing area ratio. |

| Sample name |

Roughness (ml/min) |

Pinholes (number/dm2) |

| Base paperboard | ||

| BASE | 1119±139 | >30 |

| Series A—IR 20% | ||

| A1 | 883±165 | >30 |

| A2 | 765±141 | 19.0±3.6 |

| A3 | 691±151 | 4.6±2.0 |

| A4 | 676±152 | 1.6±1.2 |

| A5 | 495±64 | 0.0±0.0 |

| A6 | 490±134 | 0.0±0.0 |

| Modified Series A—IR 80% | ||

| MA2 | 881±134 | >30 |

| MA3 1 | Not measured | Not measured |

| Series B—IR 40% | ||

| B1 | 861±135 | >30 |

| B2 | 770±148 | >30 |

| B3 | 687±112 | >30 |

| B4 | 584±156 | >30 |

| B5 | 585±100 | >30 |

| B6 | 496±126 | 9.4±3.4 |

| Modified Series B—IR 40%—half of the IR elements are active | ||

| MB6 | 482±82 | 0.0±0.0 |

| Reference thick single coating | ||

| RSA1 | 527±89 | >30 |

| RSB1 | 689±135 | >30 |

| Reference thick double coating | ||

| RDA1 | 526±51 | >30 |

| RDA2 | 662±129 | >30 |

| RDB1 | 474±93 | >30 |

| RDB2 | 431±90 | >30 |

| Sample name |

Sa unfiltered (μm) |

Sa filtered (μm) |

Sc (cm3/m2) |

Sv (cm3/m2) |

Sc/Sv |

(cm3/m2) |

| Base paperboard | ||||||

| BASE | 6.70±0.35 | 4.42±0.21 | 10.10±0.63 | 0.92±0.06 | 11.1±0.9 | 11.02±0.65 |

| Series A—IR 20% | ||||||

| A5 | 5.85±1.02 | 3.32±0.04 | 8.45±1.19 | 0.82±0.13 | 10.3±0.7 | 9.27±1.31 |

| A6 | 6.05±1.48 | 2.99±0.21 | 8.45±1.63 | 1.01±0.30 | 8.5±1.0 | 9.46±1.93 |

| Series B—IR 40% | ||||||

| B5 | 6.02±0.70 | 3.48±0.10 | 8.81±1.00 | 0.89±0.04 | 9.9±0.7 | 9.70±1.04 |

| B6 | 6.43±0.99 | 3.23±0.33 | 9.60±1.49 | 0.87±0.07 | 11.0±0.8 | 10.48±1.56 |

| Modified Series B—IR 40%—half of the IR elements are active | ||||||

| MB6 | 4.99±0.52 | 2.99±0.08 | 7.29±0.63 | 0.76±0.12 | 9.6±0.8 | 8.06±0.75 |

| Reference thick single coating | ||||||

| RSA1 | 7.60±2.03 | 4.83±0.27 | 11.80±4.35 | 0.97±0.05 | 12.0±3.8 | 12.80±4.40 |

| RSB1 | 7.34±0.87 | 5.07±0.29 | 10.98±1.64 | 0.99±0.04 | 11.0±1.3 | 11.96±1.67 |

| Reference thick double coating | ||||||

| RDA1 | 6.41±0.34 | 4.60±0.19 | 9.25±0.26 | 0.98±0.09 | 9.5±0.6 | 10.22±0.35 |

| RDA2 | 5.74±0.60 | 4.06±0.43 | 8.35±0.88 | 0.87±0.10 | 9.7±0.7 | 9.22±0.96 |

| RDB2 | 6.57±1.09 | 4.08±0.18 | 9.95±2.10 | 0.89±0.05 | 11.2±1.9 | 10.84±2.14 |

| Sample name | Paperboard entering the coater |

Vs (cm3/m2) |

Incremental coat weight (g/m2) |

Vwet (cm3/m2) |

| A1 | BASE | 11.02±0.65 | 1.5 | 7.2 |

| A6 | A5 | 9.27±1.31 | 0.5 | 2.4 |

| B1 | BASE | 11.02±0.65 | 1.4 | 6.7 |

| B6 | B5 | 9.70±1.04 | 0.45 | 2.1 |

| MB6 | B5 | 9.70±1.04 | 0.45 | 2.1 |

| RSA1 | BASE | 11.02±0.65 | 5.4 | 25.8 |

| RSB1 | BASE | 11.02±0.65 | 5.4 | 25.8 |

| RDA1 | BASE | 11.02±0.65 | 3.7 | 17.7 |

| RDA2 | RDA1 | 10.22±0.35 | 3.1 | 14.8 |

| RDB1 | BASE | 11.02±0.65 | 3.9 | 18.6 |

| Sample name |

AOIR (mL/day) |

OTR (cm3/m2day atm) |

Kit Rating Number |

| Base paperboard | |||

| BASE | 663±15 | ||

| Series A—IR 20% | |||

| A1 | 337±44 | ||

| A2 | 43.1±2.1 | ||

| A3 | 13.3±9.4 | ||

| A4 | 5.9±1.9 | 5 | |

| A5 | 9.0±4.2 | 12 | |

| A6 | 11.3±1.9 | 511±267 | 12 |

| Series B—IR 40% | |||

| B6 | 22.9±6.4 | 8 | |

| Modified Series B—IR 40%—half of the IR elements are active | |||

| MB6 | 6.7±0.8 | 12 | |

| Reference thick single coating | |||

| RSB1 | 254±38 | >1000 | |

| Reference thick double coating | |||

| RDB1 | 253±30 | ||

| RDB2 | 135±9 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).