Background

The burden of disease caused by fragility fractures is increasing in most high-income countries [

1,

2]. Of these, hip fractures (syn. Proximal Femoral Fractures - PFF) are the most common and often the most severe injury type, with an estimated 30-day mortality rate up to 10 % [

3]. Along with pre-existing comorbidities, hip fractures are also common causes for care home admissions affecting around 10 % of all hip fracture survivors [

4]. However, it is often neglected that the majority of them will return to their homes and have a life expectancy of several years [

5,

6]. Thus, regaining sufficient mobility, self-care capacity, and getting adequate pain control can make a pivotal difference to survival and post-surgery care needs and quality of life. However, frequent problems such as fear of falling, depression, pain and fatigue need to be recognized and addressed [

7]. By many experts, the frequent loss of independence following a hip fracture is considered inevitable rather than a consequence of insufficient rehabilitation content, duration, frequency and intensity. Even high-income countries have widely disparate post-fracture services that range from almost none to moderate intensity rehabilitation. Thus, there is a need to focus on postoperative mobility to optimize disability free survival perspectives [

8,

9].

The most recent Cochrane Review evaluating the effect of rehabilitation programs for patients with PFF concluded that robust data on mortality and care home admissions are available. However, valid data on physical mobility and other core patient outcomes are missing or incomplete [

10]. Emerging digital technologies such as inertial wearable devices enable granular measurement of mobility in patients with PFF in their real-world environment [

11,

12]. Recent developments in movement sensor algorithms led by the Mobilise-D consortium [

13,

14] allow the measurement of temporo-spatial parameters, such as walking speed, cadence and stride length in walking bouts of different durations. In total, 24 digital mobility outcomes (DMOs) were technically validated, encompassing five domains of walking: amount, pattern, pace, rhythm, and bout-to-bout-variability [

15]. This expands the available data assessed in real-world environments and opens a new arena for evaluating the outcomes of surgical treatment, orthogeriatric co-management, and rehabilitation strategies such as home vs. in-patient rehabilitation. Further options include patient monitoring, stratification and predictive modeling [

16].

This paper presents the results of real world DMOs and supervised clinical outcomes assessed at baseline in a large sample of PFF participants recruited within a year from surgery as part of the Mobilise-D Clinical Validation study (CVS) [

17]. Also, patient-reported outcomes and characteristics are described, and considerations about the feasibility of digital mobility assessment in this clinical population are discussed.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

The Mobilise-D CVS is a multicentre observational cohort study which included participants who had a PFF, Parkinson’s disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and multiple sclerosis. The study protocol for the Mobilise-D CVS was registered within the ISRCTN registry in December 2020 (Reference number: 12051706) and published [

17]. All eligible participants were invited for a first visit (baseline assessment) and follow-up visits every 6 months for up to 24 months. This paper reports on baseline data of the 564 PFF participants included (database version 6.2).

Recruitment of PFF participants took place between May 2021 and June 2023 across five clinical sites: the Fracture Liaison Service of Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Montpellier (CHUM) in France; Robert Bosch Hospital, Stuttgart and Heidelberg University Medical Center in Germany; St. Olavs Hospital, Trondheim University Hospital and Oslo University Hospital in Norway.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were: surgical treatment for a low-energy fracture of the proximal femur (International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) codes S72.0, S72.1, S72.2) within the previous year, 45 years of age or older, community dwelling prior to the hip fracture, able to walk 4 meters independently at the time of baseline assessment, and ability to comply with study procedures including providing informed consent and being able to read and write in the first language of the respective country. Those who had major heart surgery, stroke, active treatment for malignancy, major psychiatric disorders including severe dementia or delirium, or continued substance abuse within 3 months prior to study entry were excluded.

Participants were allowed to enter the study at any time point during the first postoperative year, although efforts were made to include them as soon as possible after surgery. Based on setting (in- or outpatient) and evidence from an existing longitudinal observational study on functional recovery [

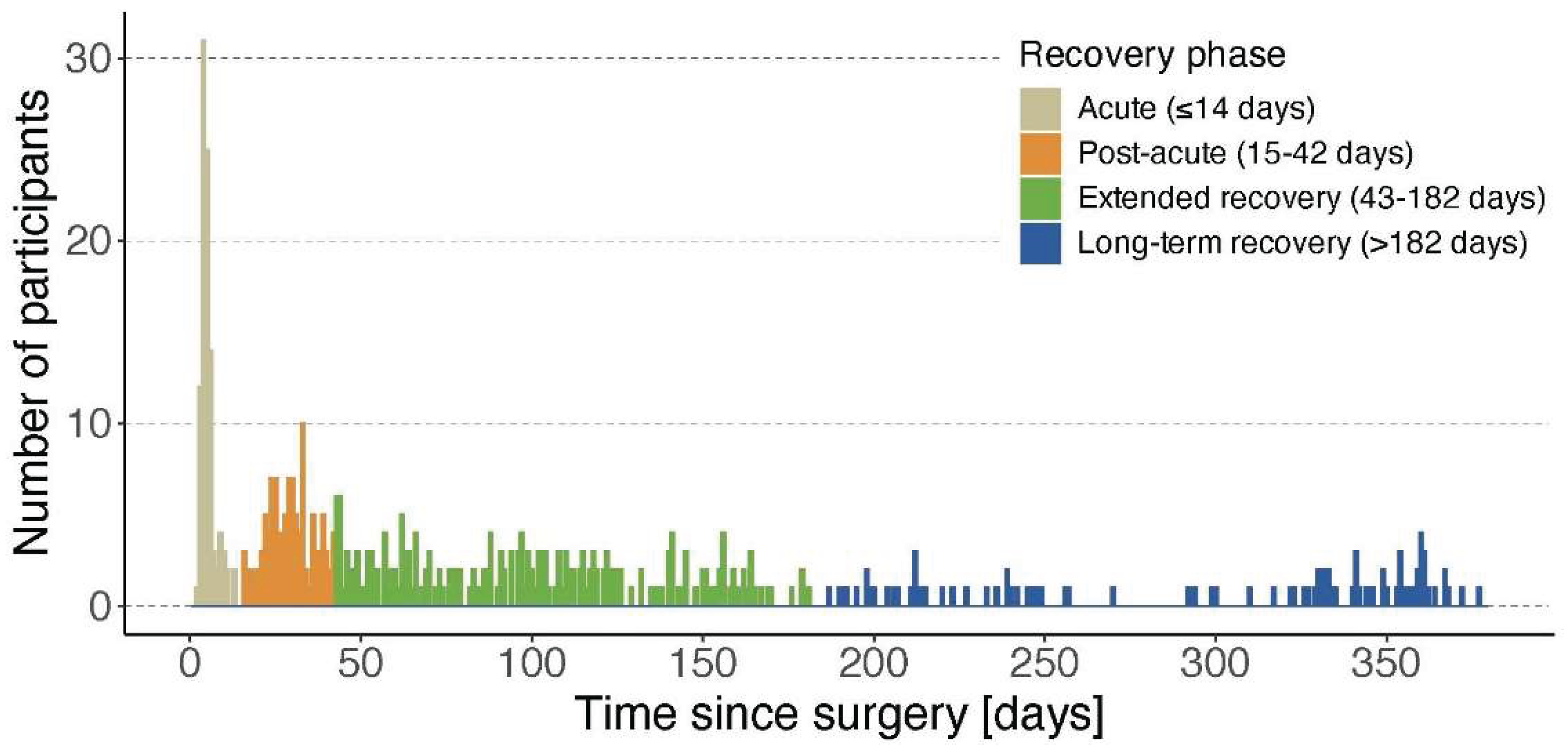

18], participants were categorized into four phases according to the assessment time after surgery: the acute phase (≤14 days post-surgery, in-hospital stay), the post-acute recovery phase (15 to 42 days post-surgery, most often rehabilitation), the extended recovery phase (43 – 182 days post-surgery, typically post-discharge at home) and the long-term recovery phase (183 – 365 days post-surgery, representing the second half of the first year). The participants’ inclusion timeline according to these different phases is shown in

Figure 1.

Study Procedure

Participants were recruited during their hospital stay after surgery, at rehabilitation wards after hospital discharge, and through patient lists. After identification of potential participants, the first screening for eligibility was performed through medical note reviews. Those potentially eligible were approached either in person or by phone and provided with the patient information sheet and details about the study. Interested persons provided written informed consent and underwent a face-to-face screening appointment to determine eligibility. If included into the study, the baseline assessment took place within two weeks after the initial screening.

On-site baseline assessment took around three hours and could be split into two sessions if participants became fatigued. All data were entered directly to a tablet device that contained appropriate software applications designed to match the workflow of the protocol, and data were subsequently transferred to a centralised database for processing and analysis. At the end of the baseline assessment, participants were provided with a single wearable device attached to the lower back. All assessors were trained prior to study start via a series of webinars and standardized materials. A detailed description of the study procedures and assessment battery was provided in the study protocol (Mikolaizak 2022).

Assessment Battery

Participants’ characteristics collected included sociodemographic, i.e., age, sex, education, living situation and residence, pre-fracture functional status measured using the Nottingham Extended Activity of Daily Living Index (NEADL, range 0 – 66, higher scores indicate greater independence) [

19] and pre-surgical health status measured by the American Society of Anaesthesiologists score (ASA, range I – V, higher scores indicate worse health status) [

20]. Clinical characteristics included fracture type, days since surgery, and use of walking aids indoors and outdoors.

Supervised clinical outcome assessment was performed to assess physical capacity, including the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB, range 0 - 12, higher scores indicate better physical capacity) [

21], comprising a static balance test, a 4-meter walk test and a five-repetition chair rise test (5CRT). Additionally, the Timed-up-and-Go test (TUG) [

22] and the 6-minute walk test (6MinWT) [

23] were performed. The cognitive status at baseline was determined using the short Mini-Mental State Examination (sMMSE, range 0 – 6, higher scores indicate better cognitive status) [

24].

Patient-reported outcomes included perceived function and disability measured by the Late-Life Function and Disability Instrument (LLFDI, range 0 – 100, higher scores indicate better functional level) [

25], the Life-Space Assessment (LSA, range 0 – 120, higher scores indicate larger life space) [

26], the Short Falls Efficacy Scale-International (Short FES-I, range 0 – 28, higher scores indicate greater concerns of falling) [

27], the Pain Visual Analogue Scale (VAS, range 0 – 100, higher scores indicate greater pain levels) [

28], the Euro-QoL (EQ-5D) VAS score (range 0 – 100, higher scores indicate better health status) [

29], and the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy Fatigue Scale (FACIT, range 0 – 52, higher scores indicate less fatigue) [

30].

Acute PFF participants required some protocol adaptations due to their post-surgical state. In this group, the LLFDI was administered to assess pre-fracture function instead of the ‘current status’ since this questionnaire has not been validated for acute patients. Also, acute participants did not carry out the 5CRT as part of the SPPB due to safety concerns. The 6 MinWT and the TUG were not feasible for most participants in the first postoperative days due to pain and physical limitations.

Digital Mobility Outcome Assessment

Digital assessment of real-world mobility was recorded over seven consecutive days using a single wearable device. The wearable device used was either the McRoberts MoveMonitor+ (McRoberts B.V., The Hague, The Netherlands) or the Axivity AX6 (Axivity Ltd., Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK).

In total, 24 DMOs were technically validated in a prior study which included PFF participants, covering the domains of walking amount, pace, pattern, rhythm and bout-to-bout-variability [

31]. For this paper, we limit the reporting to the most commonly used DMOs, namely walking amount, pace and pattern [

32]. Parameters related to rhythm and bout-to-bout variability will be reported in an upcoming paper on construct validity of all DMOs.

Data from the single wearable device were first standardised according to the data structure outlined elsewhere [

33]. Walking bouts (WB) were identified [

34], and gait features such as initial foot contact, cadence, and stride length were extracted using the validated Mobilise-D computational pipeline [

14,

35]. Six DMOs were calculated for each WB: duration, number of steps, cadence, walking speed, stride length, and stride duration. Days or weeks that did not meet the predefined minimum wear time, i.e., >12 hours required for a valid day (during waking time from 07:00 to 22:00 hours) and ≥3 valid days for a reliable week (no weekday/weekend restrictions), were removed [

36]. Bout level DMOs were aggregated at the weekly level: number of steps (n), walking duration (minutes), walking speed (m/s) in shorter (10-30s) and longer (>30s) WBs, 90th percentile (P90) walking speed (m/s) in WBs of >10s and >30s, stride length in WBs of 10-30s and >30s (cm), number of WBs (all, > 10s, > 30s, > 60s), WB duration (s), and P90 WB duration (s) [

31].

The technical validation also demonstrated that patients with low physical function and very slow walking speed < 0.5 m/s, had a higher error rate for the spatial parameters such as stride length and thereby walking speed [

15,

37]. It was anticipated that this bias would affect measurements in acute participants to a greater extent compared to participants in other phases due to a short stride length and thereby a lower walking speed.

Statistics

For sociodemographic, clinical, patient-reported outcomes, and DMOs, time interval-based participant characteristics are presented as means and standard deviations (SD) or median and 25th and 75th percentiles (P25-P75) depending on their distribution. Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages. Boxplots were used to visualize the distribution of DMOs across the four recovery phases. The statistical software R (v4.4.0; R Core Team 2024) was used for the analyses.

Results

Main Characteristics

Table 1 presents the demographic and pre-fracture status of the sample. In total, 564 participants (mean (SD) age: 77.5 (9.6) years) were included, of which the majority were females (66.3%). Participants had relatively independent pre-fracture physical function with a median (P25-P75) NEADL score of 60.0 (51.0 – 64.0), reflecting a sample with little to moderate impairment. Also, more than half were classified with ASA scores of III and IV (52.3%) indicating major to severe systemic comorbidities (

Table 1).

The adherence to the digital mobility outcome assessment was high, with a total of 505 participants (88.9%) providing valid data (i.e., at least 12 hours during waking hours and ≥3 valid days wear time).

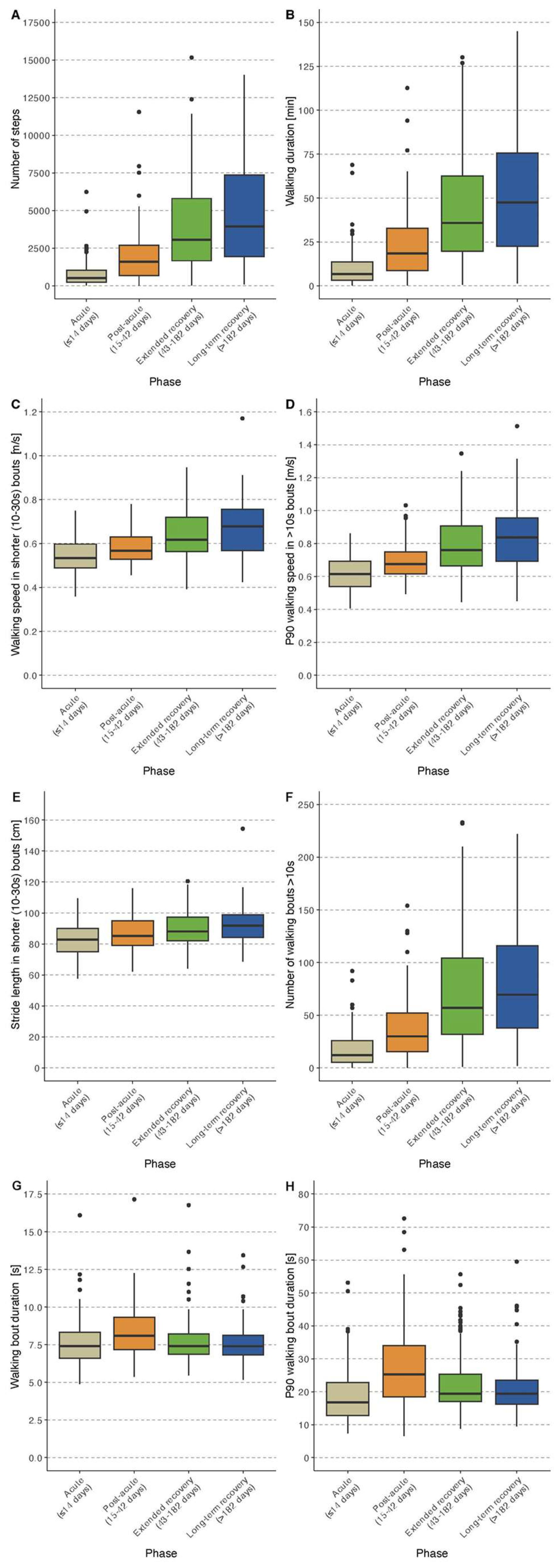

Results for patient-reported outcomes, clinical outcome assessment, and DMOs are described for each recovery phase separately below and are reported in

Table 2 and 3. Selected DMOs stratified by the four recovery phases are shown in boxplot in

Figure 2.

Acute Phase Participants (≤14 Days Post-Operatively)

Acute participants (n=117, mean (SD) age 78.4 (9.2) years, 69% women) were mostly recruited in Trondheim. Eighty-four percent had a femoral neck fracture (

Table 2).

Patient-Reported Outcomes and Clinical Outcome Assessment

The mean (SD) s-FESI was 11.6 (5.2) indicating moderate concerns about falling. Participants reported severe pain while walking (median (P25 – P75) VAS: 50.0 (28.5 – 70.0)) and rated their overall health on the EQ-5D VAS as 52.2 (21.1) reflecting a moderately impaired quality of life. The mean (SD) FACIT score was 34.8 (10.0) indicating moderate levels of fatigue. Cognitive status was robust with a mean (SD) sMMSE of 5.2 (1.1), which translates to a MMSE score in the range of 26 points or above [

38]. The post-operative assessments of mobility showed a very low physical capacity in this group (mean (SD) supervised 4-meter gait speed: 0.35 (0.20) m/s) and mean (SD) for the SPPB of 3.3 (2.0) (

Table 2).

DMOs

The median (P25-P75) step count was 515 (233 – 1,038) steps/day and walking time was 6.6 (3.0 – 13.8) minutes. For short WBs (10-30 s), the median (P25-P75) walking speed was 0.53 (0.49 – 0.60) m/s and P90 walking speed was 0.62 (0.54 – 0.69) m/s. The median (P25-P75) walking speed for walking bouts of >30s was 0.56 (0.51-0.60) m/s. For bout distribution, a median (P25-P75) number of 35 WBs (21 – 76) was identified with a median (P25-P75) duration of 7.4 (6.6 – 8.3) s and P90 duration of 16.8 (12.7 – 22.8) s. Further details are given in

Table 3.

Post-Acute Phase Participants (15-42 Days Post-Operatively)

Post-acute participants (n=126, mean (SD) age 80.0 (9.3) years, 65% women) were mostly recruited in Stuttgart. In this group, nearly two thirds had a femoral neck fracture (60.3%). More than 90% used walking aids indoors and outdoors (

Table 2).

Patient-Reported Outcomes and Clinical Outcome Assessment

The mean (SD) s-FESI was 12.0 (4.4), indicating persistent moderate concerns about falling. Participants reported mild pain while walking (median (P25 – P75) VAS: 22.5 (8.0 – 50.0)) and rated their overall health on average as 60.5 (17.0). A mean (SD) LLFDI functional score of 45.4 (10.4) and a median (P25-P75) LSA score of 18.0 (8.0 – 30.0) indicated a low functional level and restricted life-space in this group. The cognitive status and fatigue score were similar to the acute phase (mean (SD) sMMSE: 5.0 (1.1) and mean (SD) FACIT: 35.2 (11.2), respectively).

The post-acute assessments of mobility capacity showed a mean (SD) SPPB total score of 5.3 (2.6), indicating a low physical capacity, and a mean (SD) supervised 4-meter gait speed of 0.61 (0.23) m/s. The mean (SD) distance walked in the 6MinWT was 221 (105) meters (completers n=112, 88.9%), the mean (SD) time for completion of the 5 CRT was 17.3 (6.5) s (completers = 28, 22.2%); the TUG took on average 26.2 (16.1) s (completers = 116; 92.1%) (

Table 2).

DMOs

Participants recruited in the post-acute phase had a median (P25-P75) step count of 1,595 (681 - 2,704) steps/day and median (P25-P75) walking duration of 18.6 (8.4 – 32.4) minutes. For shorter WBs (10-30s), the median (P25-P75) walking speed was 0.57 (0.53 – 0.63) m/s and the P90 walking speed was 0.68 (0.62 – 0.75) m/s. Median (P25-P75) walking speed was somewhat higher during longer walking bouts (>30 s) compared to short WBs with 0.62 (0.56 – 0.70) m/s. The bout distribution identified a median (P25-P75) number of 83 WBs (37 – 143) with a median (P25-P75) duration of 8.1 (7.2 – 9.3) s and P90 duration of 25.2 (18.4 – 34.0) (

Table 3).

Extended Recovery Phase Participants (43-182 Days Post-Operatively)

Participants in this phase (n=214, mean (SD) age 75.8 (9.6) years, 65% women) were recruited across all sites. Nearly two-thirds (65%) had a femoral neck fracture. Most participants used walking aids indoors (56.1%) and outdoors (71.0%) (

Table 2).

Patient-Reported Outcomes and Clinical Outcome Assessment

The mean (SD) s-FESI was 10.8 (4.3), indicating moderate concerns about falling. Participants reported mild pain while walking (median (P25 – P75) VAS: 20.0 (3.0 – 44.8)) and rated their overall health on the EQ-5D VAS as 65.1 (18.9). The mean (SD) LLFDI functional score of 52.8 (12.4) indicated a reduced functional level and the median (P25-P75) LSA score of 43.5 (24.4 to 64.1) reflects a mostly homebound life-space in this group. The mean (SD) FACIT score was 38.8 (10.0) indicating moderate levels of fatigue. The cognitive status for this group was similar to the previous groups with a mean (SD) sMMSE: 5.3 (1.0).

The mean (SD) SPPB total score was 7.3 (2.9) indicating moderate functional limitations, and the mean (SD) supervised 4-meter gait speed was 0.79 (0.35) m/s. The mean (SD) distance walked in the 6MinWT was 299 (127) meters (completers = 199; 91.7%), the mean (SD) time for 5 CRT was 17.4 (7.1) s (completers n=143; 65.9%) and the TUG took on average 18.1 (10.3) s (completers = 208; 95.9%) (

Table 2).

DMOs

This group had a median (P25-P75) step count of 3,063 (1,669 – 5,805) steps/day and median (P25-P75) walking time of 36.0 (19.8 – 62.4) minutes. For short WBs (10-30s), the median (P25-P75) walking speed was 0.62 (0.56 – 0.72) m/s and the P90 walking speed was 0.76 (0.66 – 0.91) m/s. The median (P25-P75) walking speed was higher during longer walking bouts (>30 s) with 0.70 (0.60 – 0.84) m/s. For bout distribution, a median (P25-P75) number of 190 WBs (113 – 294) were identified with a median (P25-P75) duration of 7.4 (6.9 – 8.2) s and P90 duration of 19.4 (17.0 – 25.3) s (

Table 3).

Long-Term Recovery Phase Participants (183-365 Days Post-Operatively)

Participants in this group were recruited across all sites (n=107, mean (SD) age 77.2 (9.6) years, 68% women). More than two thirds (70.1%) had a femoral neck fracture. Fewer participants in this group used walking aids indoors (32.7%), but more than half used them outdoors (54.2%) (

Table 2).

Patient-Reported Outcomes and Clinical Outcome Assessment

The mean (SD) s-FESI was 10.1 (4.1), indicating moderate concerns about falling. Participants reported mild pain while walking (median (P25 – P75) VAS: 14.5 (1.0 – 35.3)). The overall health was rated on average as 70.6 (20.8), showing the highest value of the four groups. The mean (SD) LLFDI functional score of 57.4 (12.3) indicates a higher functional level than the extended recovery group. The median (P25-P75) LSA score of 59.0 (32.5 to 81.5) indicates a life space including more outdoor activities in this group. The mean (SD) FACIT score of 39.6 (9.9) still reflects moderate fatigue level. The cognitive status was similar to the other groups (mean (SD) sMMSE: 5.2 (1.1)).

The assessments of mobility capacity showed a mean (SD) SPPB score of 7.8 (3.3), indicating moderate functional limitation, and a mean (SD) supervised 4-meter gait speed of 0.91 (0.40) m/s. The mean (SD) distance walked in the 6MinWT was 320 (131) meters (completers = 103; 96.2%), the mean (SD) time for the 5 CRT was 15.1 (4.9) s (completers = 74; 69.2%), and the TUG took on average 17.0 (10.8) s (completers = 106; 99.1%) (

Table 2).

DMOs

Participants recruited in the long-term recovery phase had a median (P25-P75) step count of 3,949 (1,937 – 7,360) steps/day and a median (P25-P75) walking time of 47.4 (22.8 – 75.6) minutes. For short WBs (10-30s), the median (P25-P75) walking speed was 0.68 (0.42 – 0.57) m/s, and the P90 walking speed was 0.84 (0.69 – 0.96) m/s. The median (P25-P75) walking speed was higher during longer WBs (>30 s) compared to short WBs with 0.80 (0.66 – 0.88) m/s. For bout distribution, a median (P25-P75) number of 231 WBs (119 – 372) were identified with a median (P25-P75) duration of 7.4 (6.8 – 8.1) s and P90 duration of 19.4 (16.3 – 23.6) s (

Table 3).

Discussion

Main Findings and Lessons Learned

We successfully recruited more than 500 patients with PFF within a year from surgery and assessed their functional capacity and real-world mobility performance across four different recovery phases. Overall, we found that assessment of real-world mobility was highly feasible in this cohort, with nearly 90% of participants completing the 7-day digital mobility assessments. We also found that commonly used mobility assessments had limited feasibility during the acute and post-acute phases due to floor effects. This included the 5CRT, the TUG test and to a smaller degree the 6MinWT. Vice versa, some of these measures such as the 4-meter walk test or a 6MinWT could often not be performed in home environments which limits their usefulness in future trials requiring home visits or remote study designs.

As expected, we observed major differences in the amount, pace, and pattern of walking using wearable devices between participants in the four phases. Walking amount such as the number of steps and walking time, walking speed, and number of WBs were much higher in participants recruited at later post-operative phases compared to those in earlier phases. These differences became smaller but were still noticeable for those recruited in the second half of the year after surgery compared to the participants during the first six months. However, these differences were not found for all DMOs. The average walking bout duration was longer during the post-acute phase compared to the bout duration after discharge probably due to longer corridors during the in-patient rehabilitation phase. Therefore, some of the differences are likely to be caused by factors such as the built environment, neighborhood walkability, traffic, green space and environmental factors such as rain, heat, icy conditions or air pollution.

Compared to a community dwelling cohort of older adults in the InChianti study (Albites-Sanabria 2025 under review), the DMOs data demonstrate that there still is considerable gap in the amount and pattern of walking between even the best quartile of patients with PFF and healthy controls. The InChianti cohort with a mean age of 79 years had a median value of 8261 steps (vs 3949), a walking time of 90 minutes (vs. 48 minutes). Around 155 walking bouts of 10s-30s were detected (vs 70) and 26 walking bouts with a duration of 30 sec and longer were detected (vs 10). The gait speed parameters did not differ. The walking speed was 0.64 m/sec in shorter (vs. 0.68) and 0.79 m/sec in longer walking bouts (vs. 0.8).

Take Home Messages for Clinical Trialists and Regulators

Due to the pan-European decrease in length of stay post-operatively, it will be increasingly challenging to enroll patients with PFF in the acute phase particularly for randomized controlled studies. Most patients were requesting to talk to their family before entering the study. Many potential participants explained that they wanted to get back to their home environment before entering the study. Our data also show that the group recruited during the post-acute phase was somewhat older and had more comorbidities compared to the acute phase. This must be considered to maximize the external validity.

The ongoing preferred use of walking amount parameters (step counts and walking duration) is based on outdated technology and ignores the lack of spatiotemporal information (stride length, and walking speed) which is relevant from a regulatory, patient and clinical perspective. We therefore recommend reporting spatial and temporal information to describe cross-sectional and longitudinal trajectories of patients. We also recommend the use of mean and maximum pace information in longer (30s+) and shorter walking bouts (10-30s). Longer walking bouts represent mostly outdoor activities. Shorter walking bouts are more informative on indoor walking. Additional analyses and methods such as EMA (ecological momentary assessments) are needed for this ground truth-based validation. Maximum pace informs about capacity and the potential to adapt walking speed when needed, for example when navigating pedestrian crossings. The pattern recognition (bout frequency in shorter and longer bouts) gives insight into the functional recovery with an anticipated increase in the number of walking bouts with longer duration. The description of maximum walking bout duration informs about habit formation and capacity.

In a recent systematic review on all European Medicines Agency decisions that included bone health medication [

39], we could not identify any study that included supervised

or digital mobility assessments as part of the regulatory process. Physical mobility is impaired in most osteoporotic populations, with PFF being the most pronounced clinical example. The final acceptance of wearable technologies will need data from randomized controlled trials [

12]. In our discussions with Health Technology Assessment bodies, it has been questioned whether an improvement in physical mobility is a health care claim at this moment [

40]. Our data of the PFF cohort point in the opposite direction. It is undisputed that an increase in walking amount has numerous beneficial health effects [

41], making a strong case for its mandated assessment. The analysis of pace is needed since clinically measured gait speed was found to be a strong predictor of long-term rehabilitation success [

42]. An even higher predictive validity for clinical events is assumed for measures under real life conditions.

Take Home Messages for Clinical Experts and Patients

The challenge of using DMOs (and COAs) in clinical practice and the derived empowerment of patients lies in the interpretation of single results (n=1) and comparing the results with known groups of similar patients. The recovery phases presented in this study were chosen to give reasonable feedback to different professional groups that are in charge and involved with patients in these different timeframes, such as orthopedic surgeons, geriatricians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, nursing staff and general physicians. The (repeated) digital assessments can describe the performance based on walking amount, pace and pattern. This can provide guidance on whether reassurance, watchful waiting, or action such as training boosters is appropriate. The boxplot diagrams and the quartiles listed give an indication on how patients with PFF regain mobility post-operatively. When a repeated assessment is done, it can inform about a change in the expected trajectory, including improvement and worsening of the physical performance (Engdal et al. 2024).

From a patient and/or family caregiver perspective, it is clear that physical mobility is a core part of quality of life and determines the probability of an independent lifestyle and the fundamental question of the possibility to return to the pre-fracture state. The core domains of patient perspectives on mobility include ease and effort of walking, the perceived safety, pace and walking distance [

43]. The presented data provide insight into how this compares to other patients with PFF. Future longitudinal data analyses will also allow the identification of patients that do not follow expected trajectories. The DMOs can describe pace, pattern and amount whereas the perception of safety and effort of walking requires the administration of patient-reported outcome measures. This process will require further co-design work with patients and health care professionals [

44].

Limitations

The pre-pandemic ambition was to recruit an acute PFF population and follow as many as possible over a period of 24 months. When the Covid-19 pandemic hit, recruitment and assessment had to be postponed in order to adhere to the medical circumstances and comply with the legal obligations which resulted in a longer recruitment period. Further, our study did not include care home residents and patients with moderate to severe dementia and major delirium, thus our results are not fully generalizable to these PFF patients.

The current paper focuses on walking amount, pace, and pattern. The output of the full DMO matrix of Mobilise-D includes results on rhythm and bout-to-bout variability. As the investigation of the clinical usefulness of rhythm and bout-to-bout variability is ongoing and currently considered exploratory, these outcomes were not included.

Most of the walking bouts during the acute phase occurred during physiotherapy when participants had assistance or were accompanied by nursing staff. Hence, further technical validation of spatial parameters in acute PFF patients is needed to test their validity in this phase. This has not been done in the Mobilise-D technical validation study [

13] due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Perspectives

Several publications are in preparation. Upcoming papers will include construct validity of DMOs by describing the relationship with clinically relevant constructs. The assessment of the ability of DMOs and physical capacity measures to detect change and the estimation of Minimal Important Differences (MID) of DMOs to measure change in disease (worsening or improvement) is ongoing. Further work will cover the predictive capacity of DMOs on care home admission and mortality. We also plan to publish the longitudinal data as soon as possible. Qualitative data will be published on subjective experiences of patient journeys. Environmental data will be analysed to understand their impact on mobility.

Conclusions

The observed difference in walking amount, pace and pattern across recovery phases indicate that DMOs provide an in-depth analysis of real-world mobility of hip fracture survivors. When confirmed by longitudinal analyses, including results on minimal important differences, the use of selected DMOs will provide a novel approach for monitoring, predictive modeling, prognosis, stratification and evaluation of clinical trials and hip fracture services.

Availability of Data and Materials

Conflict of Interests

RM and DR are full-time employees of Novartis. All other authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Clemens Becker, Tobias Eckert, Jochen Klenk, Carl-Philipp Jansen, Martin Berge, Monika Engdal, Beatrix Vereijken, Niki Brenner, Jorunn Helbostad, Ingvild Saltvedt, Lars Gunnar Johnsen, Hubert Blain, Valerie Driss, Lene Solberg, Trine Strøm, Brian Caulfield, David Singleton, Judith Garcia-Aymerich, Laura Delgado-Ortiz, Sarah Koch, Joren Buekers, Paula Alvarez, Ram Miller , Daniel Rooks, Lynn Rochester, Silvia Del Din, Andrea Cereatti and Anna Marcuzzi; Data curation, Brian Caulfield, David Singleton, Judith Garcia-Aymerich, Laura Delgado-Ortiz, Sarah Koch, Joren Buekers and Paula Alvarez; Formal analysis, Tobias Eckert, Jochen Klenk, Carl-Philipp Jansen, Brian Caulfield, Judith Garcia-Aymerich, Laura Delgado-Ortiz, Sarah Koch and Joren Buekers; Funding acquisition, Clemens Becker, Beatrix Vereijken, Brian Caulfield, Judith Garcia-Aymerich and Lynn Rochester; Investigation, Clemens Becker, Tobias Eckert, Jochen Klenk, Carl-Philipp Jansen, Martin Berge, Monika Engdal, Beatrix Vereijken, Niki Brenner, Jorunn Helbostad, Ingvild Saltvedt, Lars Gunnar Johnsen, Hubert Blain, Valerie Driss, Lene Solberg, Trine Strøm and Anna Marcuzzi; Methodology, Clemens Becker, Tobias Eckert, Jochen Klenk, Carl-Philipp Jansen, Martin Berge, Monika Engdal, Beatrix Vereijken, Niki Brenner, Jorunn Helbostad, Ingvild Saltvedt, Lars Gunnar Johnsen, Hubert Blain, Valerie Driss, Lene Solberg, Trine Strøm, Brian Caulfield, David Singleton, Judith Garcia-Aymerich, Laura Delgado-Ortiz, Sarah Koch, Joren Buekers, Paula Alvarez, Ram Miller , Daniel Rooks, Lynn Rochester, Silvia Del Din, Andrea Cereatti and Anna Marcuzzi; Project administration, Clemens Becker, Carl-Philipp Jansen, Jorunn Helbostad, Hubert Blain, Valerie Driss, Lene Solberg, Trine Strøm and Anna Marcuzzi; Resources, Ram Miller and Daniel Rooks; Software, Brian Caulfield and David Singleton; Supervision, Clemens Becker, Brian Caulfield, Judith Garcia-Aymerich and Lynn Rochester; Visualization, Jochen Klenk; Writing – original draft, Clemens Becker, Tobias Eckert, Jochen Klenk, Carl-Philipp Jansen, Martin Berge, Monika Engdal, Beatrix Vereijken, Niki Brenner, Jorunn Helbostad, Ingvild Saltvedt, Lars Gunnar Johnsen, Lene Solberg and Anna Marcuzzi; Writing – review & editing, Clemens Becker, Tobias Eckert, Jochen Klenk, Carl-Philipp Jansen, Martin Berge, Monika Engdal, Beatrix Vereijken, Niki Brenner, Jorunn Helbostad, Ingvild Saltvedt, Lars Gunnar Johnsen, Hubert Blain, Valerie Driss, Lene Solberg, Trine Strøm, Brian Caulfield, David Singleton, Judith Garcia-Aymerich, Laura Delgado-Ortiz, Sarah Koch, Joren Buekers, Paula Alvarez, Ram Miller , Daniel Rooks, Lynn Rochester, Silvia Del Din, Andrea Cereatti and Anna Marcuzzi.

Funding

This study was part of the Mobilise-D project, which was funded by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (JU) under grant agreement No. 820820. This JU receives support from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program and the European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA). SDD and LR were also supported by the IDEA-FAST project that has received funding from the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (JU) under grant agreement No. 853981. SDD and LR were supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) based at The Newcastle upon Tyne Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle University and the Cumbria, Northumberland and Tyne and Wear (CNTW) NHS Foundation Trust. SDD and LR were also supported by the NIHR/Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility (CRF) infrastructure at Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. SDD was supported by the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) (Grant Ref: EP/X031012/1 and Grant Ref: EP/X036146/1). LR is supported by an NIHR Senior Investigators Award. For JGA, LDO, JB and SK: ISGlobal acknowledges support from the grant CEX2023-0001290-S funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and support from the Generalitat de Catalunya through the CERCA Programme. All opinions are those of the authors and not the funders. The content in this publication reflects the authors’ views and neither IMI nor the European Union, EFPIA, NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care are responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained herein.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and ethical approval was obtained at each study site by the Committee of the Protection of Persons, South-Mediterranean II, Montpellier (ref.: 221BO8), the EC of the Medical Faculty of Eberhard-Karls-University Tubingen, Stuttgart (ref.: 976/2020BO2), the EC of the Medical Faculty at Heidelberg University (ref.: S-719/2021), and the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Trondheim (ref.: 216069).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided written informed consent before entering the study.

Acknowledgements

We thank our assessors, clinical site leads and supporting orthopedic surgeons in Trondheim, Oslo, Stuttgart/Heidelberg and Montpellier for their work, spirit and humour. In Germany the staff included Martha Gierka, Clarissa Huber, Vanessa Zoller, Elena Litz, Jana Krespach, Carmen Lamparter, Dr. Ulrich Liener, Dr. Bernd Kinner, Dr. Markus Aarand. In Trondheim and Oslo, we would like to thank and acknowledge Erika Skaslien, Mari Odden, Ingalill Grøtta Midtsand, Karoline Blix Grønvik, Kjersti Opdal, Ola Grimstad, Hege Thrygg, Elise Berg Vesterhus. We greatly thank Lou Sutcliffe, David Singleton, Isabel Neatrour and Stefanie Mikolaizak for their support in data management, monitoring, training and supervision.

References

- Borgstrom, F.; Karlsson, L.; Ortsater, G.; Norton, N.; Halbout, P.; Cooper, C.; Lorentzon, M.; McCloskey, E. V.; Harvey, N. C.; Javaid, M. K.; et al. Fragility fractures in Europe: burden, management and opportunities. Arch Osteoporos 2020, 15 (1), 59. [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, N.; Tsilidis, K. K.; Orfanos, P.; Benetou, V.; Ntzani, E. E.; Soerjomataram, I.; Künn-Nelen, A.; Pettersson-Kymmer, U.; Eriksson, S.; Brenner, H.; et al. Burden of hip fracture using disability-adjusted life-years: a pooled analysis of prospective cohorts in the CHANCES consortium. Lancet Public Health 2017, 2 (5), e239-e246. [CrossRef]

- Patel, R.; Judge, A.; Johansen, A.; Marques, E. M. R.; Griffin, J.; Bradshaw, M.; Drew, S.; Whale, K.; Chesser, T.; Griffin, X. L.; et al. Multiple hospital organisational factors are associated with adverse patient outcomes post-hip fracture in England and Wales: the REDUCE record-linkage cohort study. Age and Ageing 2022, 51 (8). [CrossRef]

- Rapp, K.; Rothenbacher, D.; Magaziner, J.; Becker, C.; Benzinger, P.; Konig, H. H.; Jaensch, A.; Buchele, G. Risk of Nursing Home Admission After Femoral Fracture Compared With Stroke, Myocardial Infarction, and Pneumonia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015, 16 (8), 715 e717-715 e712. [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.; Xi, I. L.; Ahn, J.; Bernstein, J. Median survival following geriatric hip fracture among 17,868 males from the Veterans Health Administration. Front Surg 2023, 10, 1090680. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, J.; Lee, A.; Xi, I. L.; Ahn, J. Estimating Median Survival Following Hip Fracture Among Geriatric Females: (100 - Patient Age) ÷ 4. Cureus 2022, 14 (6), e26299. [CrossRef]

- Auais, M.; Sousa, T. A. C.; Feng, C.; Gill, S.; French, S. D. Understanding the relationship between psychological factors and important health outcomes in older adults with hip fracture: A structured scoping review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2022, 101, 104666. [CrossRef]

- Fairhall, N. J.; Dyer, S. M.; Mak, J. C.; Diong, J.; Kwok, W. S.; Sherrington, C. Interventions for improving mobility after hip fracture surgery in adults. Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2022, (9). [CrossRef]

- Papanicolas, I.; Figueroa, J. F.; Schoenfeld, A. J.; Riley, K.; Abiona, O.; Arvin, M.; Atsma, F.; Bernal-Delgado, E.; Bowden, N.; Blankart, C. R.; et al. Differences in health care spending and utilization among older frail adults in high-income countries: ICCONIC hip fracture persona. Health Serv Res 2021, 56 Suppl 3 (Suppl 3), 1335-1346. [CrossRef]

- Handoll, H. H. G.; Cameron, I. D.; Mak, J. C. S.; Panagoda, C. E.; Finnegan, T. P. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for older people with hip fractures. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2021, (11). [CrossRef]

- Jansen, C.-P.; Engdal, M.; Peter, R. S.; Helbostad, J. L.; Taraldsen, K.; Vereijken, B.; Pfeiffer, K.; Becker, C.; Klenk, J. Sex differences in mobility recovery after hip fracture: a time series analysis. Frontiers in Public Health 2024, 12, 1434182. [CrossRef]

- Engdal, M.; Taraldsen, K.; Jansen, C.-P.; Peter, R. S.; Vereijken, B.; Becker, C.; Helbostad, J. L.; Klenk, J. Real-world mobility recovery after hip fracture: secondary analyses of digital mobility outcomes from four randomized controlled trials. Age and Ageing 2024, 53 (10). [CrossRef]

- Mazzà, C.; Alcock, L.; Aminian, K.; Becker, C.; Bertuletti, S.; Bonci, T.; Brown, P.; Brozgol, M.; Buckley, E.; Carsin, A. E.; et al. Technical validation of real-world monitoring of gait: a multicentric observational study. BMJ Open 2021, 11 (12), e050785. [CrossRef]

- Kirk, C.; Küderle, A.; Micó-Amigo, M. E.; Bonci, T.; Paraschiv-Ionescu, A.; Ullrich, M.; Soltani, A.; Gazit, E.; Salis, F.; Alcock, L.; et al. Mobilise-D insights to estimate real-world walking speed in multiple conditions with a wearable device. Sci Rep 2024, 14 (1), 1754. [CrossRef]

- Micó-Amigo, M. E.; Bonci, T.; Paraschiv-Ionescu, A.; Ullrich, M.; Kirk, C.; Soltani, A.; Küderle, A.; Gazit, E.; Salis, F.; Alcock, L.; et al. Assessing real-world gait with digital technology? Validation, insights and recommendations from the Mobilise-D consortium. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2023, 20 (1), 78. [CrossRef]

- González de Villaumbrosia, C.; Sáez López, P.; Martín de Diego, I.; Lancho Martín, C.; Cuesta Santa Teresa, M.; Alarcón, T.; Ojeda Thies, C.; Queipo Matas, R.; González-Montalvo, J. I.; On Behalf Of The Participants In The Spanish National Hip Fracture, R. Predictive Model of Gait Recovery at One Month after Hip Fracture from a National Cohort of 25,607 Patients: The Hip Fracture Prognosis (HF-Prognosis) Tool. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18 (7). [CrossRef]

- Mikolaizak, A. S.; Rochester, L.; Maetzler, W.; Sharrack, B.; Demeyer, H.; Mazzà, C.; Caulfield, B.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; Vereijken, B.; Arnera, V. Connecting real-world digital mobility assessment to clinical outcomes for regulatory and clinical endorsement–the Mobilise-D study protocol. PLoS One 2022, 17 (10), e0269615. [CrossRef]

- Magaziner, J.; Chiles, N.; Orwig, D. Recovery after Hip Fracture: Interventions and Their Timing to Address Deficits and Desired Outcomes--Evidence from the Baltimore Hip Studies. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser 2015, 83, 71-81.

- Nouri, F.; Lincoln, N. An extended activities of daily living scale for stroke patients. Clinical rehabilitation 1987, 1 (4), 301-305. [CrossRef]

- Dripps, R. American Society of Anesthesiologists. New classification of physical status. Anesthesiology 1963, 24 (1), 111.

- Guralnik, J. M.; Simonsick, E. M.; Ferrucci, L.; Glynn, R. J.; Berkman, L. F.; Blazer, D. G.; Scherr, P. A.; Wallace, R. B. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol 1994, 49 (2), M85-94. [CrossRef]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991, 39 (2), 142-148.

- Guyatt, G. H.; Sullivan, M. J.; Thompson, P. J.; Fallen, E. L.; Pugsley, S. O.; Taylor, D. W.; Berman, L. B. The 6-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J 1985, 132 (8), 919-923.

- Schultz-Larsen, K.; Lomholt, R. K.; Kreiner, S. Mini-Mental Status Examination: a short form of MMSE was as accurate as the original MMSE in predicting dementia. J Clin Epidemiol 2007, 60 (3), 260-267. [CrossRef]

- Haley, S. M.; Jette, A. M.; Coster, W. J.; Kooyoomjian, J. T.; Levenson, S.; Heeren, T.; Ashba, J. Late Life Function and Disability Instrument: II. Development and evaluation of the function component. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002, 57 (4), M217-222. [CrossRef]

- Baker, P. S.; Bodner, E. V.; Allman, R. M. Measuring life-space mobility in community-dwelling older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003, 51 (11), 1610-1614.

- Kempen, G. I.; Yardley, L.; van Haastregt, J. C.; Zijlstra, G. A.; Beyer, N.; Hauer, K.; Todd, C. The Short FES-I: a shortened version of the falls efficacy scale-international to assess fear of falling. Age Ageing 2008, 37 (1), 45-50. [CrossRef]

- Farrar, J. T.; Young, J. P. J.; LaMoreaux, L.; Werth, J. L.; Poole, M. R. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. PAIN 2001, 94 (2), 149-158. [CrossRef]

- EuroQol, G. EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16 (3), 199-208.

- Webster, K.; Cella, D.; Yost, K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003, 1, 79.

- Koch, S.; Buekers, J.; Cobo, I.; Lemos, J.; Marchena, J.; Bonci, T.; Caulfield, B.; Del Din, S.; Demeyer, H.; Frei, A.; et al. From high-resolution time series to a single, clinically-interpretable value - considerations for the aggregation of real world walking speed assessed by wearable sensors in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). European Respiratory Journal 2023, 62 (suppl 67), PA1595.

- Polhemus, A.; Delgado-Ortiz, L.; Brittain, G.; Chynkiamis, N.; Salis, F.; Gaßner, H.; Gross, M.; Kirk, C.; Rossanigo, R.; Taraldsen, K.; et al. Walking on common ground: a cross-disciplinary scoping review on the clinical utility of digital mobility outcomes. NPJ Digit Med 2021, 4 (1), 149. [CrossRef]

- Palmerini, L.; Reggi, L.; Bonci, T.; Del Din, S.; Micó-Amigo, M. E.; Salis, F.; Bertuletti, S.; Caruso, M.; Cereatti, A.; Gazit, E.; et al. Mobility recorded by wearable devices and gold standards: the Mobilise-D procedure for data standardization. Sci Data 2023, 10 (1), 38. [CrossRef]

- Kluge, F.; Del Din, S.; Cereatti, A.; Gaßner, H.; Hansen, C.; Helbostad, J. L.; Klucken, J.; Küderle, A.; Müller, A.; Rochester, L. Consensus based framework for digital mobility monitoring. PloS one 2021, 16 (8), e0256541. [CrossRef]

- Salis, F.; Bertuletti, S.; Bonci, T.; Caruso, M.; Scott, K.; Alcock, L.; Buckley, E.; Gazit, E.; Hansen, C.; Schwickert, L. A multi-sensor wearable system for the assessment of diseased gait in real-world conditions. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2023, 11, 1143248. [CrossRef]

- Buekers, J.; Chernova, J.; Marchena, J.; Koch, S.; Lemos, J.; Becker, C.; Bonci, T.; Braun, J.; Caulfield, B.; Del Din, S.; et al. Reliability of real-world walking activity and gait assessment in people with COPD. How many hours and days are needed? European Respiratory Journal 2024, 64 (suppl 68), PA791.

- Berge, M.; Paraschiv-Ionescu, A.; Kirk, C.; Küderle, A.; Micó-Amigo, E.; Becker, C.; Cereatti, A.; Del Din, S.; Engdal, M.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; et al. Walking Towards Recovery: Accuracy and Reliability of Real-World Digital Mobility Outcomes in Older Adults After Hip Fracture. JMIR Preprints.

- Stein, J.; Luppa, M.; Kaduszkiewicz, H.; Eisele, M.; Weyerer, S.; Werle, J.; Bickel, H.; Mösch, E.; Wiese, B.; Prokein, J.; et al. Is the Short Form of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) a better screening instrument for dementia in older primary care patients than the original MMSE? Results of the German study on ageing, cognition, and dementia in primary care patients (AgeCoDe). Psychol Assess 2015, 27 (3), 895-904. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, S. U.; Wohlrab, M.; Schoene, D.; Tremmel, R.; Chambers, M.; Leocani, L.; Corriol-Rohou, S.; Klenk, J.; Sharrack, B.; Garcia-Aymerich, J.; et al. Mobility endpoints in marketing authorisation of drugs: what gets the European medicines agency moving? Age and Ageing 2022, 51 (1). [CrossRef]

- Wohlrab, M.; Klenk, J.; Delgado-Ortiz, L.; Chambers, M.; Rochester, L.; Zuchowski, M.; Schwab, M.; Becker, C.; Jaeger, S. U. The value of walking: a systematic review on mobility and healthcare costs. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity 2022, 19 (1), 31. [CrossRef]

- Paluch, A. E.; Gabriel, K. P.; Fulton, J. E.; Lewis, C. E.; Schreiner, P. J.; Sternfeld, B.; Sidney, S.; Siddique, J.; Whitaker, K. M.; Carnethon, M. R. Steps per Day and All-Cause Mortality in Middle-aged Adults in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4 (9), e2124516. [CrossRef]

- Gherardini, S.; Biricolti, C.; Benvenuti, E.; Almaviva, M. G.; Lombardi, M.; Pezzano, P.; Bertini, C.; Baccini, M.; Di Bari, M. Prognostic Implications of Predischarge Assessment of Gait Speed After Hip Fracture Surgery. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2019, 42 (3), 148-152. [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ortiz, L.; Polhemus, A.; Keogh, A.; Sutton, N.; Remmele, W.; Hansen, C.; Kluge, F.; Sharrack, B.; Becker, C.; Troosters, T.; et al. Listening to the patients’ voice: a conceptual framework of the walking experience. Age and Ageing 2023, 52 (1). [CrossRef]

- Keogh, A.; Mc Ardle, R.; Diaconu, M. G.; Ammour, N.; Arnera, V.; Balzani, F.; Brittain, G.; Buckley, E.; Buttery, S.; Cantu, A.; et al. Mobilizing Patient and Public Involvement in the Development of Real-World Digital Technology Solutions: Tutorial. J Med Internet Res 2023, 25, e44206.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).