1. Introduction

Bone fractures occur when an external load surpasses the physiological limits, generating stresses that exceed the bone’s strength, which has been developed through adaptation during growth and development. The ability of bones to absorb these forces is influenced by several factors, including their mineral content, underlying pathological conditions, and the species, age, and sex of the animal. These fractures are primarily caused by two factors: an external impact, such as a fall, or fractures that occur ‘spontaneously’ due to muscular contraction without direct trauma [

1,

2].

This case tells the story of a domestic dog, involved in a fierce fight with a wayward dog leaving it with a traumatic bilateral mandibular body fracture. In a setting where resources were limited, the severity of the injury painted a grim picture. Had it been left untreated; the consequences could have been fatal. Yet, in this challenge, humanity and expertise came together. A dedicated team, comprising a veterinary doctor, oral and maxillofacial surgeon, and dental surgeons, united not just by their skills, but by a shared commitment to preserving life proving that even in the most difficult circumstances, compassion and collaboration can work miracles.

2. Case Presentation

History:

A 4-year-old male dog of local indigenous breed was presented to the local veterinary clinic after being involved in a fight with a wayward dog. The dog showed signs of significant trauma and was in acute distress. The owner reported no prior history of trauma or chronic conditions.

Clinical Examination:

On clinical examination, there was a hanging fractured segment in the mandibular region, causing continuous bleeding. The functionality of the mandible was completely halted, preventing normal jaw movement. (Figure 1) The dog was in extreme pain and unable to close its mouth. No other injuries were noted in the body, though the mandibular fracture was the primary concern.

Figure 1.

Preoperative photograph showing the hanging fracture segment in the mandibular region.

Figure 1.

Preoperative photograph showing the hanging fracture segment in the mandibular region.

Diagnostic Findings:

On examination, there was a bilateral body fracture of the mandible, resembling a bucket handle fracture typically seen in edentulous human mandibles. The fracture segments were displaced, and the fractured part was hanging, contributing to the bleeding and dysfunction.

Treatment Plan:

Due to the severity of the injury and the risk of death if left untreated, the decision was made to perform open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with intraosseous wiring under IV anesthesia. The goal was to stabilize the fracture, control bleeding, and restore mandibular function.

Treatment Done:

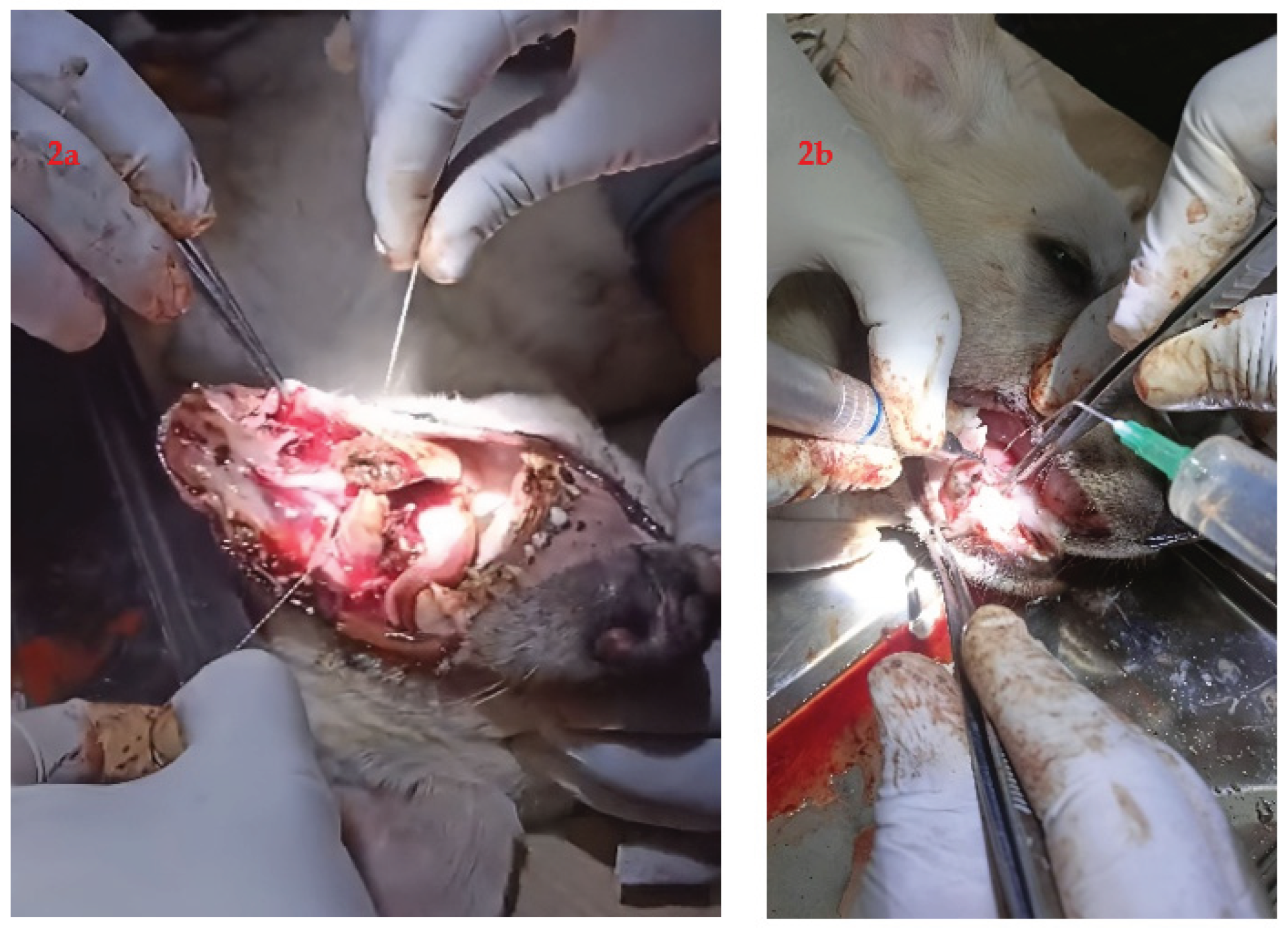

Under intravenous anesthesia, the dog underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the bilateral mandibular body fractures. Intraosseous wiring was used to stabilize the fractures. The fractured segment was repositioned and fixed in place to stop the continuous bleeding and restore the function of the mandible (Figure 2a,b).

Due to scarce resources at the local veterinary clinic and with no surgical facility and any veterinary surgeons nearby for the referral, the veterinary doctor reached out to an oral and maxillofacial surgeon for assistance. Understanding the gravity of the situation and the need for specialized care, the veterinary team, in consultation with the team of maxillofacial surgeons and dental surgeons, decided to proceed with a multidisciplinary approach. The oral and maxillofacial surgeon’s expertise was crucial in determining the best course of action for stabilizing the mandibular fracture and restoring the dog’s function (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

(a,b) Intraoperative photograph.

Figure 2.

(a,b) Intraoperative photograph.

Figure 3.

Postoperative photograph with functional rehabilitation.

Figure 3.

Postoperative photograph with functional rehabilitation.

4. Discussion

Mandibular fractures in dogs are nine times more common than maxillary fractures, particularly in cases involving trauma from fights, often resulting in severe injuries to the craniofacial region accounting for 2.5-2.7% of all the fractures in dogs. Spontaneous fractures may also occur due to bone loss from severe periodontal or endodontic infections. The mandibular body, especially the molar region, is the most frequently affected site, accounting for 41%–47.1% of cases [

3].

Fracture morphology depends on etiology, patient factors, and force characteristics. In humans, anatomical features such as bone strength, size, shape, and muscle attachments influence fracture patterns. Similarly, the direction, rate, magnitude, and spatial relationship of the force play a role. In dogs, mandibular fractures are most common in males under 12 months of age, with the mandibular body being the most frequently affected site [

4,

5,

6].

The main etiologies of mandibular fractures were road traffic accidents, falls from height, projectile injuries, dog fights, and undocumented trauma. Kitshoff et al. [

7] found that dog fights accounted for 62% of mandibular fractures in their retrospective study of 109 dogs, a higher incidence than previously reported (19–43%) by Umphlet et al. [

5] and Lopes et al. [

6].

Canine aggression frequently targets the head and neck region during confrontation. The severity of bite wounds correlates with the size disparity between animals as the larger dogs exert greater biting forces increasing fracture risk in smaller dogs. Unsupervised outdoor access combined with roaming activity common in males as they are considered to be more territorial and aggressive compared with females [

8], elevates the incidence of traumatic injury, including mandibular fractures. Owner negligence further contributes to the high prevalence of fractures with undocumented causes [

6].

Treatment of jaw fractures has a high complication rate of 34%, with nearly two-thirds involving malocclusion or osteomyelitis. Diagnosis is typically straightforward, and the primary treatment goal is restoring proper dental occlusion and jaw function.

Plate fixation provides the greatest stability for mandibular and maxillary fractures but carries risks of damaging tooth roots and neurovascular structures due to limited screw placement options. In young dogs, avoiding unerupted teeth is particularly difficult. A key challenge is that the tension side of the mandible is the alveolar border, requiring plate placement near critical structures for optimal stability. However, placing the implant slightly away from this region often remains effective, as jaw forces are moderate compared to implant strength [

2,

9,

10].

A bucket handle fracture, common in edentulous human mandibles [

11], is a rare but significant type of injury in animals, as seen in this case. These fractures can cause functional impairment and lead to life-threatening conditions if not promptly managed. The hanging fractured segment caused continuous bleeding, and the loss of function could have led to serious complications, including shock and death. Open reduction and internal fixation are standard procedures for stabilizing such fractures in animals, and intraosseous wiring has proven to be an effective method for ensuring proper fixation in cases of complex mandible fractures [

1,

2,

3,

4,

7,

10].

In a world where interventional medicine is often compartmentalized, for example with human medicine for humans and veterinary medicine for animals, this case challenges the conventional boundaries of ethical care. The prompt decision by the maxillofacial surgeon, dental surgeons, and veterinary personnel to intervene and repair the dog’s mandible in a resource-limited setting was not merely a clinical improvisation but a philosophical assertion that life’s worth is not defined by species but by the depth of connection it shares with others.

In Nepal, the practice of animal dentistry remains largely unexplored, with neither veterinary professionals nor dental surgeons formally engaging in this field. This gap points to a significant oversight in both veterinary and dental curricula. To address the oral health needs of animals and promote interdisciplinary collaboration, it is imperative to incorporate animal dentistry into the academic framework. Such curricular reforms would not only enhance the competency of future professionals but also contribute to the overall well-being of animals in Nepal.

In Hindu culture, dogs are worshipped [

12]. There has long been debate in Western philosophy about whether animals have intrinsic value or only instrumental worth [

13]. But in moments of crisis, such ideas often lose significance. The dog in this case wasn’t just an animal but rather a beloved companion, deeply valued by those who cared for it. This resonates with Donna Haraway’s concept of companion species, which highlights the interdependent relationships between humans and animals sharing a close, caring bond [

14]. The surgeon’s decision to operate showed respect for that bond and its moral importance.

Animals cannot consent to treatment or advocate for their care, which makes them vulnerable and constantly dependent on human moral responsibility. This idea aligns with Emmanuel Levinas’ concept of the ’Face of the Other’ [

15], where seeing vulnerability in another being creates a moral responsibility to respond.

In this case, the dog’s fractured jaw was more than a medical issue; it represented a silent moral appeal. The surgeon acted not only as a medical expert but also as someone guided by a sense of moral duty. Some might argue that using human medical expertise on animals in resource-poor settings to treat animals in low-resource settings is not practical, inefficient, and unethical. However, this viewpoint differs from Albert Schweitzer’s ‘Reverence for Life’ philosophy [

16], which teaches that all life has inherent value beyond utility. Saving this dog showed respect for the life of a vulnerable creature, reminding us that every life matters.

This case highlights the critical need for timely intervention in traumatic injuries involving the mandible, as well as the importance of specialized surgical techniques. Early surgical intervention can significantly improve the prognosis and ensure the survival and recovery of the animal.

5. Conclusions

This case highlights the importance of timely surgical intervention and interdisciplinary collaboration in managing complex mandibular fractures in animals, especially in resource-limited settings. The successful outcome underscores the need to integrate animal dentistry into veterinary and dental education in Nepal to address current gaps in care. Beyond clinical relevance, the case also reflects the ethical responsibility of healthcare professionals to respond to animal suffering, affirming the intrinsic value of all sentient life.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent for publication has been obtained from the caretaker of the dog.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ORIF |

open reduction and internal fixation |

References

- Doblaré, M.; García, J.M.; Gómez, M.J. Modelling bone tissue fracture and healing: A review. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2004, 71, 1809–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piermattei, D.L.; Flo, G.L.; DeCamp, C.E. Fractures and Luxations of the Mandible and Maxilla. In Brinker, Piermattei, and Flo’s Handbook of Small Animal Orthopedics and Fracture Repair, 4th ed.; Elsevier Saunders: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2006; pp. 717–736. [Google Scholar]

- Guzu, M.; Hennet, P.R. Mandibular Body Fracture Repair with Wire-Reinforced Interdental Composite Splint in Small Dogs. Vet. Surg. 2017, 46, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copcu, E.; Sisman, N.; Oztan, Y. Trauma and Fracture of the Mandible: Effects of Etiologic Factors on Fracture Patterns. Eur. J. Trauma 2004, 30, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umphlet, R.C.; Johnson, A.L. Mandibular Fractures in the Dog: A Retrospective Study of 157 Cases. Vet. Surg. 1990, 19, 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, F.M.; Gioso, M.A.; Ferro, D.G.; Leon-Roman, M.A.; Venturini, M.A.; Correa, H.L. Oral Fractures in Dogs of Brazil—A Retrospective Study. J. Vet. Dent. 2005, 22, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitshoff, A.M.; De Rooster, H.; Ferreira, S.M.; Steenkamp, G. A Retrospective Study of 109 Dogs with Mandibular Fractures. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 2013, 26, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scandurra, A.; Alterisio, A.; Di Cosmo, A.; D’Aniello, B. Behavioral and Perceptual Differences between Sexes in Dogs: An Overview. Animals 2018, 8, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harasen, G. Maxillary and Mandibular Fractures. Can. Vet. J. 2008, 49, 819–820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boudrieau, R.J.; Kudisch, M. Miniplate Fixation for Repair of Mandibular and Maxillary Fractures in 15 Dogs and 3 Cats. Vet. Surg. 1996, 25, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, N.; Singh, S.; Bhatnagar, S. Expanding Hematoma with Facial Nerve Palsy: An Unusual Complication of Mandibular Fracture. Int. J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2024, 10, 345–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahal, B.P. Dialectics of Sacrificing and Worshiping Animals in Hindu Festivals of Nepal. Adv. Anthropol. 2020, 10, 97–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsgaard, C.M. Kantian Ethics, Animals, and the Law. Oxf. J. Legal Stud. 2013, 33, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D.J. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness; Prickly Paradigm Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Trinh, K. Levinas’ Concept of the Face of Others and Its Ethical Responsibility Toward Strangers. Authorea Preprints 2024.

- Schweitzer, A. The Ethics of Reverence for Life. Christendom 1936, 1, 225–239. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).