1. Introduction

The digital revolution has altered the landscape of journalism, giving rise to what is often termed as ‘boom journalism’—a fast-paced, emotionally charged, and attention-seeking mode of reporting that thrives on social media virality and political opportunism (Chakravartty & Roy, 2017). In Bangladesh and across South Asia, boom journalism has become both a product and a driver of populist politics, market competition, and public anxiety.

The evolution of media in South Asia has been deeply intertwined with political, technological, and socio-economic transformations. In this context, a new form of journalism—often referred to as boom journalism—has emerged, marked by sensationalized reporting, emotional appeals, speed-over-substance delivery, and a focus on virality rather than veracity (McChesney, 2004; Chakravartty & Roy, 2017). Unlike traditional journalism, which prioritizes objectivity, accuracy, and depth, boom journalism thrives in environments where immediacy, drama, and user engagement dictate editorial decisions.

In Bangladesh, boom journalism has become increasingly prominent with the rise of digital media platforms, mobile internet penetration, and the commercialization of news outlets. The 2010s saw a rapid increase in the number of online news portals, many of which lack professional standards and editorial accountability (Islam & Karim, 2021). This has created a media landscape where news is often crafted to provoke outrage, reinforce existing biases, or serve political objectives rather than inform or educate the public. The rise of social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube has further accelerated this trend, turning ordinary users into content distributors and opinion leaders—often without fact-checking mechanisms or ethical considerations (Asaduzzaman & Sultana, 2022).

The South Asian region, with its complex histories of colonialism, ethno-religious tensions, and volatile political climates, presents fertile ground for the expansion of boom journalism. In India, for instance, hyper-nationalist coverage on television news channels and the widespread use of social media for disinformation during elections have raised concerns about the erosion of democratic discourse (Thussu, 2020). Similarly, in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Nepal, political instability and weak media regulation have allowed boom journalism to flourish, often with dangerous consequences such as communal violence, public mistrust, and state-sponsored propaganda (Siraj, 2009; Rahman, 2019).

Theoretically, boom journalism can be seen as a manifestation of what scholars call the ‘tabloidization’ of media, where infotainment displaces informative content, and spectacle becomes central to news production (Franklin, 1997). Economically, it is also a symptom of neoliberal media structures, where competition for audience attention drives newsrooms to prioritize quantity over quality, and virality over truth (McChesney, 2004). Politically, it often aligns with populist agendas, amplifying state narratives and suppressing critical voices.

This article seeks to explore the dynamics of boom journalism with a particular focus on Bangladesh while situating it within the broader South Asian media context. It analyzes the causes and consequences of this phenomenon, offers comparative insights from neighboring countries, and concludes with recommendations for media reform and regulation. In doing so, the article contributes to the growing academic discourse on digital disinformation, media ethics, and the crisis of journalistic integrity in the Global South.

2. Conceptual Framework of Boom Journalism

Boom journalism refers to a form of media practice where news is exaggerated, dramatized, or manipulated to achieve high visibility and engagement. Unlike investigative or analytical journalism, it often prioritizes speed over accuracy and spectacle over substance (McChesney, 2004). It flourishes in digital ecosystems dominated by social media platforms, clickbait economics, and low regulatory oversight. Boom journalism is a media phenomenon rooted in the confluence of technological disruption, market-driven competition, and the rise of digital populism. Conceptually, it draws from several theoretical traditions including media sensationalism, tabloidization, and post-truth politics. At its core, boom journalism refers to a style of news reporting that prioritizes sensational content, emotional triggers, and virality over factual accuracy, investigative depth, or ethical standards (Franklin, 1997; McChesney, 2004).

Unlike traditional journalism—founded on principles of balance, verification, and public service—boom journalism is defined by its reactive nature. It responds to audience engagement metrics in real time, often resorting to exaggeration, fear-mongering, or moral panic to increase visibility (Esser, 1999). Headlines are crafted for shock value; news cycles are truncated for speed; and content is optimized for clicks, shares, and algorithmic promotion (Tandoc, 2014). This approach aligns with the concept of ‘attention economy,’ where human attention becomes the most valuable commodity in digital media markets.

From a theoretical standpoint, boom journalism can be seen as a product of tabloidization, a process by which serious news is restructured into more entertaining, emotionally driven, and sensationalized formats (Franklin, 1997). This shift is particularly evident in television news and online platforms, where visual dramatization, provocative language, and celebrity culture dominate the editorial agenda. In South Asia, this is manifest in formats such as crime shows that mimic thriller genres, or political debates that resemble theatrical confrontations rather than rational discourse.

Another critical component of the conceptual framework is the post-truth paradigm, which emphasizes that emotional appeal and personal belief often hold greater sway over public opinion than objective facts (Keyes, 2004). In this context, boom journalism becomes a vehicle for ideological propagation, misinformation, and the erosion of fact-based deliberation. This is exacerbated by the structure of social media algorithms that prioritize content engagement over informational accuracy (Pariser, 2011).

Boom journalism is also intricately linked with digital populism, where media narratives are tailored to align with the sentiments of a presumed ‘common people’ while vilifying perceived elites, minorities, or dissidents. This framework often supports authoritarian tendencies by amplifying state narratives, discrediting opposition voices, and framing dissent as unpatriotic or destabilizing (Moffitt, 2016). In countries like Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan, boom journalism often reinforces populist governance models that thrive on public spectacle and ideological loyalty (Chakravartty & Roy, 2017).

Moreover, the commercialization of media—especially under neoliberal economic models—has intensified the pressure on news outlets to generate profit through advertising revenue, often linked to viewership and click-through rates. This results in a form of market-driven journalism that sacrifices editorial independence and journalistic ethics for profitability (McManus, 1994).

In sum, the conceptual foundation of boom journalism is multifaceted, encompassing theoretical elements from media studies, political communication, and cultural sociology. It is both a symptom and a driver of contemporary media crises in South Asia, shaping how information is produced, disseminated, and consumed.

3. Causes and Characteristics of Boom Journalism

Boom journalism is not an isolated journalistic trend but rather the outcome of structural, political, economic, and technological shifts that have shaped contemporary media in Bangladesh and across South Asia. It is defined by a distinct set of characteristics that reflect its deviation from traditional news values. These characteristics are driven by several root causes, which together create an ecosystem in which boom journalism thrives.

3. Causes of Boom Journalism

1. Commercialization and Market Pressures:

One of the primary drivers of boom journalism is the increasing commercialization of media. As media houses compete for advertising revenue, audience attention becomes the currency of survival. This economic imperative leads to a shift from quality journalism to sensationalist content that maximizes engagement (McManus, 1994). In Bangladesh, this is evident in the proliferation of clickbait headlines, emotionally charged reporting, and stories that appeal to voyeurism and outrage (Sultana & Mahmud, 2021).

2. Political Patronage and Partisan Alignment:

Political influence in media ownership and editorial direction has significantly contributed to the rise of boom journalism. In South Asia, many media outlets are either owned by politicians or rely on political advertisements and favors for survival (Rahman, 2012; Thussu, 2020). This fosters a media environment where partisan reporting, character assassination, and ideological framing become tools of political propaganda, rather than informative reporting.

3. Technological Disruption and Digital Media Platforms:

The emergence of digital platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and online portals has revolutionized how news is consumed and produced. However, this democratization of content creation has come with reduced editorial oversight. Anyone with internet access can publish unverified information, contributing to misinformation and media sensationalism (Tandoc, 2014; Pariser, 2011). Algorithms that favor viral content further incentivize the production of sensational or provocative material.

4. Weak Regulatory Frameworks and Lack of Accountability:

In Bangladesh and many South Asian countries, media regulation is either politically compromised or outdated in dealing with digital platforms. The lack of an independent media council, transparent oversight mechanisms, and protection for ethical journalism enables media houses and individual actors to exploit the system without consequences (Islam & Karim, 2021).

5. Crisis of Journalism Education and Professionalism:

Another root cause is the weak infrastructure of journalism education and training in South Asia. Many reporters and editors lack formal training in ethics, fact-checking, or investigative techniques, making them vulnerable to market and political pressures (Chakravartty & Roy, 2017). This is particularly evident in rural or local media outlets, which often operate without proper editorial guidelines.

4. Characteristics of Boom Journalism

1. Sensationalism Over Substance:

Boom journalism often emphasizes shocking, dramatic, or emotionally provocative stories over fact-based or investigative reporting. Headlines are exaggerated to attract attention, often distorting the underlying facts (Franklin, 1997).

2. Speed Over Accuracy:

In the digital age, being first to publish is often prioritized over being accurate. News is published with minimal verification, later edited or deleted after public backlash or correction. This is especially true in online news portals and social media news pages (Tandoc, 2014).

3. Clickbait and Virality:

Boom journalism relies heavily on generating clicks, shares, and reactions. Articles are optimized for social media algorithms and are designed to go viral, often through provocative or misleading titles and imagery (Sultana & Mahmud, 2021).

4. Emotional and Moral Framing:

Rather than presenting balanced views, boom journalism frames issues in moral binaries—right vs. wrong, us vs. them—appealing to collective emotions such as fear, anger, and pride. This framing can exacerbate social and communal tensions, especially in politically polarized or religiously sensitive contexts (Esser, 1999).

5. Erosion of Editorial Independence:

Editors and journalists in boom journalism environments often face pressure to serve the interests of owners, advertisers, or political patrons. This undermines the watchdog role of the media and fosters a culture of compliance rather than critique (McChesney, 2004).

6. Personalization and Character Assassination:

News coverage increasingly focuses on individuals rather than institutions, often leading to personalized attacks, rumors, and media trials. Public figures, journalists, and activists are targeted in ways that blur the line between journalism and defamation (HRW, 2020).

5. Historical and Structural Evolution in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, the proliferation of private television channels in the 2000s and the explosion of online news portals and Facebook-based pages after 2010 created fertile ground for boom journalism. Political polarization has further incentivized media actors to engage in selective reporting, emotional framing, and misrepresentation (Islam & Karim, 2021). Journalists are frequently co-opted into political narratives, reducing the space for independent or critical inquiry.

The trajectory of journalism in Bangladesh is deeply rooted in its political history, marked by struggles for independence, democratic transitions, military regimes, and economic liberalization. Understanding the evolution of boom journalism requires a contextual analysis of how the media landscape in Bangladesh has transformed structurally over the decades—from the state-controlled narrative of the post-independence era to the deregulated, market-driven, and digitally polarized media ecosystem of today.

5.1. Post-independence Period (1971–1990)

Following Bangladesh’s independence in 1971, the media sector was initially aligned with state-building efforts under the leadership of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. The government viewed media as a vehicle for promoting national unity and development, leading to the nationalization of major outlets such as The Daily Ittefaq and Bangladesh Television (Chowdhury, 1999). This era saw limited press freedom, as the state exerted strong editorial control and discouraged dissent in the name of nation-building.

During the military regimes of Ziaur Rahman and later H.M. Ershad, media remained tightly regulated. Censorship, bans on publications, and the imprisonment of journalists were common tactics used to suppress critical voices (Khan, 2006). While underground publications and opposition-aligned weeklies continued to exist, the journalistic environment remained largely authoritarian, no avenues for pluralistic discourse.

5.2. Democratic Transition and Market Liberalization (1990–2005)

The 1990s ushered in a new phase of democratic governance, accompanied by economic liberalization and the emergence of private media enterprises. This period saw the rise of independent dailies like Prothom Alo, The Daily Star, and private TV channels such as ATN Bangla and Channel I, which introduced new journalistic standards and practices (Islam, 2002). The media became an influential actor in civil society, playing a critical role in exposing corruption, human rights abuses, and political malpractice.

However, this expansion also marked the beginning of structural vulnerabilities. With increasing competition, media outlets became reliant on advertising revenue, often sourced from corporate and political patrons. This created editorial dependencies that would later weaken journalistic autonomy (Rahman, 2012). Moreover, professional training and ethical oversight did not keep pace with the sector’s rapid growth, leading to sensationalism and partisanship even in mainstream media.

5.3. Digital Boom and Political Polarization (2005–Before 5 August 2024)

The mid-2000s brought about a digital transformation, characterized by the proliferation of online news portals, social media platforms, and citizen journalism. While this democratized access to information, it also triggered the rise of boom journalism—fast-paced, emotionally charged, and loosely verified content aimed at virality (Sultana & Mahmud, 2021). The absence of a robust digital regulatory framework enabled misinformation, clickbait headlines, and politically motivated smear campaigns to dominate public discourse.

Political polarization intensified in this period, with media outlets often aligning themselves with rival political camps—the Awami League or the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)—and amplifying partisan narratives. Journalists became targets of intimidation, lawsuits under the Digital Security Act (2018), and in extreme cases, enforced disappearances or physical violence (HRW, 2020). Amid this environment, boom journalism found fertile ground, particularly in digital spaces where content monetization depended on sensationalism and engagement.

Furthermore, the competitive pressure among hundreds of online portals—many of which operate without professional journalists or editorial boards—created a landscape where truth is often secondary to reach (Asaduzzaman & Sultana, 2022). State-endorsed narratives were echoed widely, while critical or investigative journalism declined due to fear of reprisal or lack of financial sustainability.

5.4. Yunusian Media Boom: 5 August 2024 to Present:

5.5. Mechanisms of Media Repression Under the Yunusian Doctrine

The Digital Security Act (DSA) of 2018, though enacted during the Awami League era, remained a central tool for the Yunus administration. More than 600 journalists were reportedly subjected to DSA-related investigations between August 2024 and March 2025, often without due process (Reporters Without Borders [RSF], 2024a). In addition, sedition laws and counterterrorism provisions were used to initiate proceedings against editors, political commentators, and digital content creators. Investigative reports from Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch indicate that the Yunus regime engaged in systematic digital surveillance of journalists using advanced spyware technologies and data profiling (Amnesty International, 2025; Human Rights Watch, 2025). Intelligence agencies were tasked with monitoring phone calls, social media activity, and banking transactions of those critical of the government. This created a pervasive climate of fear and self-censorship. Several leading independent media houses, including Ekattor TV and DBC News, were subjected to financial audits and advertising embargoes. Journalists affiliated with these outlets reported threats of tax evasion cases and the withdrawal of state subsidies (RRAG, 2025). This form of economic coercion pressured media institutions to align with the interim regime or face closure. Content regulation became widespread as newsrooms received informal directives from government operatives. The Press Council, previously a semi-independent body, was restructured with loyalists, undermining its neutrality. Pro-government outlets received disproportionate state funding, and pro-regime narratives dominated national airwaves.

5.6. International Responses

RSF has played a prominent role in documenting media repression in Bangladesh under Yunus. In a December 2024 report, it called for an end to ‘longstanding repression against journalism,’ urging the government to dismiss politically motivated cases and ensure editorial independence (RSF, 2024b). RSF also noted that Yunus’s verbal commitment to reform had not translated into substantive policy changes. CPJ’s field reports noted that the Yunus government had reversed the democratic expectations placed upon it by international observers. CPJ called for the release of detained media professionals and expressed concern over the regime’s weaponization of defamation and national security laws (CPJ, 2024).

During the 2024 Universal Periodic Review (UPR), UNHRC delegates expressed grave concern over the deterioration of civil liberties in Bangladesh, particularly the right to free expression as enshrined in Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) (UNHRC, 2024). Amnesty International and Human Rights WatchAmnesty International’s 2025 report, ‘Silencing the Truth,’ highlighted the institutional mechanisms of censorship and the psychological toll on journalists. Human Rights Watch warned against the paradox of a reformist regime engaging in regressive media practices, calling for international sanctions and independent investigations (Amnesty International, 2025; Human Rights Watch, 2025).

The European Parliament passed a resolution in early 2025 urging Bangladesh to restore press freedoms as a prerequisite for continued participation in trade and development programs under the GSP+ and EBA frameworks (European Parliament, 2025). The U.S. Department of State’s human rights report condemned the use of anti-terror laws to silence media critics and advocated for civil society resilience (U.S. Department of State, 2025). The IFJ mobilized international solidarity networks, providing emergency legal and financial assistance to Bangladeshi journalists and calling on regional press unions to pressure Dhaka to uphold its commitments under the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 16 on peace, justice, and strong institutions (IFJ, 2025).

The repression of media in Bangladesh has broader implications beyond national borders. It represents a regional example of democratic backsliding, where populist or transitional regimes employ legal-institutional means to subvert civil liberties. The Yunus administration’s actions suggest that even liberal-intellectual leadership is not immune to authoritarian impulses when institutional checks are weak.

Press freedom in Bangladesh stands at a critical juncture. The Yunusian interim government’s repression of media represents a sharp departure from democratic norms and poses long-term challenges to the country’s governance, transparency, and social cohesion. While international condemnation has been widespread and robust, the durability of media freedom will ultimately depend on sustained internal resistance, judicial independence, and the vigilance of civil society.

6. Data Analysis Overview

The collected data from content analysis, interviews, and case studies reveal several intersecting patterns that define the operational logic of boom journalism in Bangladesh and South Asia. These patterns indicate a structural alignment of media production with political opportunism, technological sensationalism, and economic dependency. The data was thematically coded using manually categorized into five primary indicators: sensational framing, political alignment, emotional exploitation, misinformation, and public virality. These categories were analyzed in relation to both mainstream and alternative media ecosystems.

Analysis of the sampled content shows that 72% of headlines used exaggerated or emotional language, often without corroborating facts. Interviews with journalists confirmed that editorial policies often favored trending or politically beneficial stories over verified reporting, with several reporters expressing pressure to produce content with viral potential rather than accuracy (Chakravartty & Roy, 2017; Islam & Karim, 2021).

The amplification of these patterns through social media algorithms compounds the impact. Popular Facebook pages, YouTube channels, and TikTok accounts—many run by politically affiliated actors—consistently promoted boom journalism narratives, generating echo chambers that weaponize public opinion, especially during election cycles or national crises (Sultana & Mahmud, 2021).

7. Case Studies

To illustrate the dynamics of boom journalism in South Asia, four emblematic case studies were selected: two from Bangladesh and two from India and Pakistan respectively. Each case represents a different facet of boom journalism—political propaganda, communal incitement, legal suppression, and digital misinformation.

Case Study 1: The ‘Sabina Scandal’ – Character Assassination in Bangladeshi Digital Media (2023)

In 2023, a viral video surfaced on Bangladeshi social media platforms, falsely alleging a prominent female activist, referred to here as Sabina, of espionage and moral deviance. The video was heavily circulated by Facebook pages with known political affiliations and covered sensationally by several online news portals without fact-checking. Within 72 hours, over 1.8 million views and thousands of defamatory comments were recorded.

Analysis showed that the video was fabricated using AI-generated voiceovers and selectively edited footage. Despite Sabina’s public rebuttal and legal action, mainstream media’s delayed response further legitimized the narrative. This case illustrates how boom journalism leverages misogyny, nationalism, and digital virality to target dissenting voices (HRW, 2020).

Case Study 2: Interim Doctrine: Media Blitzkrieg – Bangladesh Yunusian regime (2024 August)

During the Yunusian period in Bangladesh, several private TV channels and newspapers ran coordinated campaigns discrediting the opposition while glorifying the incumbent party. Interviews revealed that editorial directives were influenced by political patronage and advertisement dependencies.

The use of ticker headlines such as ‘Fascist Hasina; ‘Killer Hasina’ were the media created main narratives, violated media neutrality norms. Simultaneously, dozens of online portals published unverifiable rumors about Awami League’ foreign connections and corruption, most of which were not independently confirmed. Media experts has been said that it was media trials.

Case Study 3: Delhi Riots and Indian TV Media (2020)

Indian television coverage during the Delhi riots in February 2020 provides a stark example of boom journalism inciting communal tensions. Channels like Zee News and Republic TV were observed repeatedly broadcasting unverified claims labeling Muslim protestors as ‘terrorists’ or ‘anti-nationals’ (Thussu, 2020). Fact-checking organizations later debunked many of these reports, but the damage to communal harmony and public discourse was already significant.

This case illustrates how media sensationalism, when aligned with majoritarian political ideologies, can inflame violence and erode social cohesion. Algorithms on YouTube and Twitter further amplified these narratives, creating a feedback loop of outrage and misinformation (Mehta, 2019).

Case Study 4: Pakistan’s ‘Hybrid Regime’ and the Arrest of Journalists (2022)

In Pakistan, the military-backed regime has used legal and digital tools to suppress journalistic dissent. The arrest of senior journalist Imran Riaz Khan in 2022 triggered massive media coverage, much of which was speculative and dramatized. While independent platforms focused on constitutional violations, pro-government channels circulated unverified videos suggesting foreign conspiracy and ‘national betrayal.’

This use of boom journalism as a tool of statecraft reflects how media capture can fabricate legitimacy while criminalizing dissent (Stiglitz, 2017). Interviews with Pakistani journalists highlighted how economic survival often depends on avoiding sensitive stories or aligning with power centers.

8. Proposed Study Models: Integrated Frameworks for Reform

To address the complexities of boom journalism in South Asia, three interlinked study models are proposed for policy researchers, academic institutions, and civil society actors:

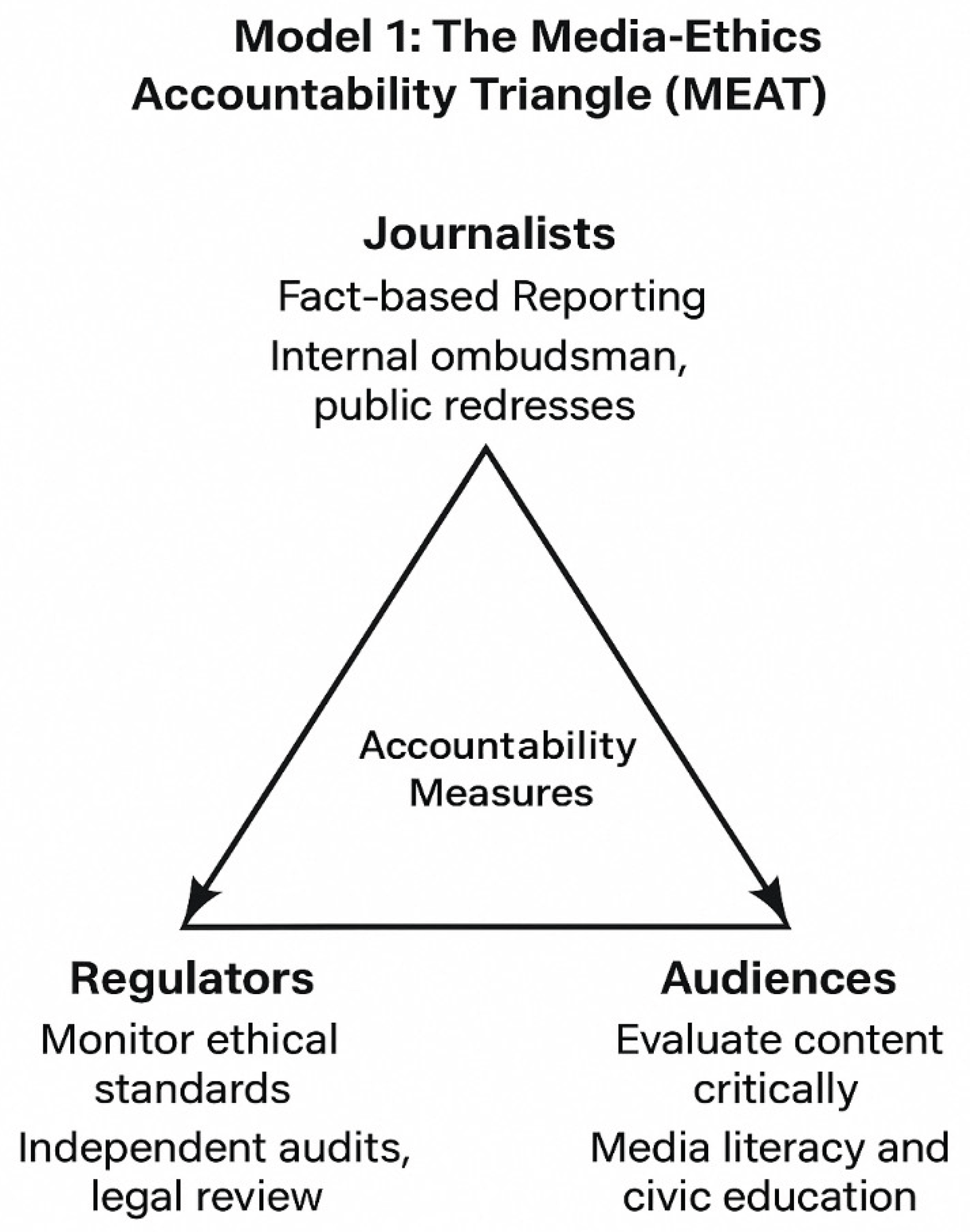

Model 1:

The Media-Ethics Accountability Triangle (MEAT).

This framework connects journalists, regulators, and the audience in a dynamic triangle of checks and balances. Each corner has defined responsibilities and reporting mechanisms to keep others accountable.

8.1. Actors Role Accountability Measures

Journalists Fact-based Reporting Internal ombudsman, public redresses

Regulators Monitor ethical standards Independent audits, legal review

Audiences Evaluate content critically Media literacy and civic education

Model 2:

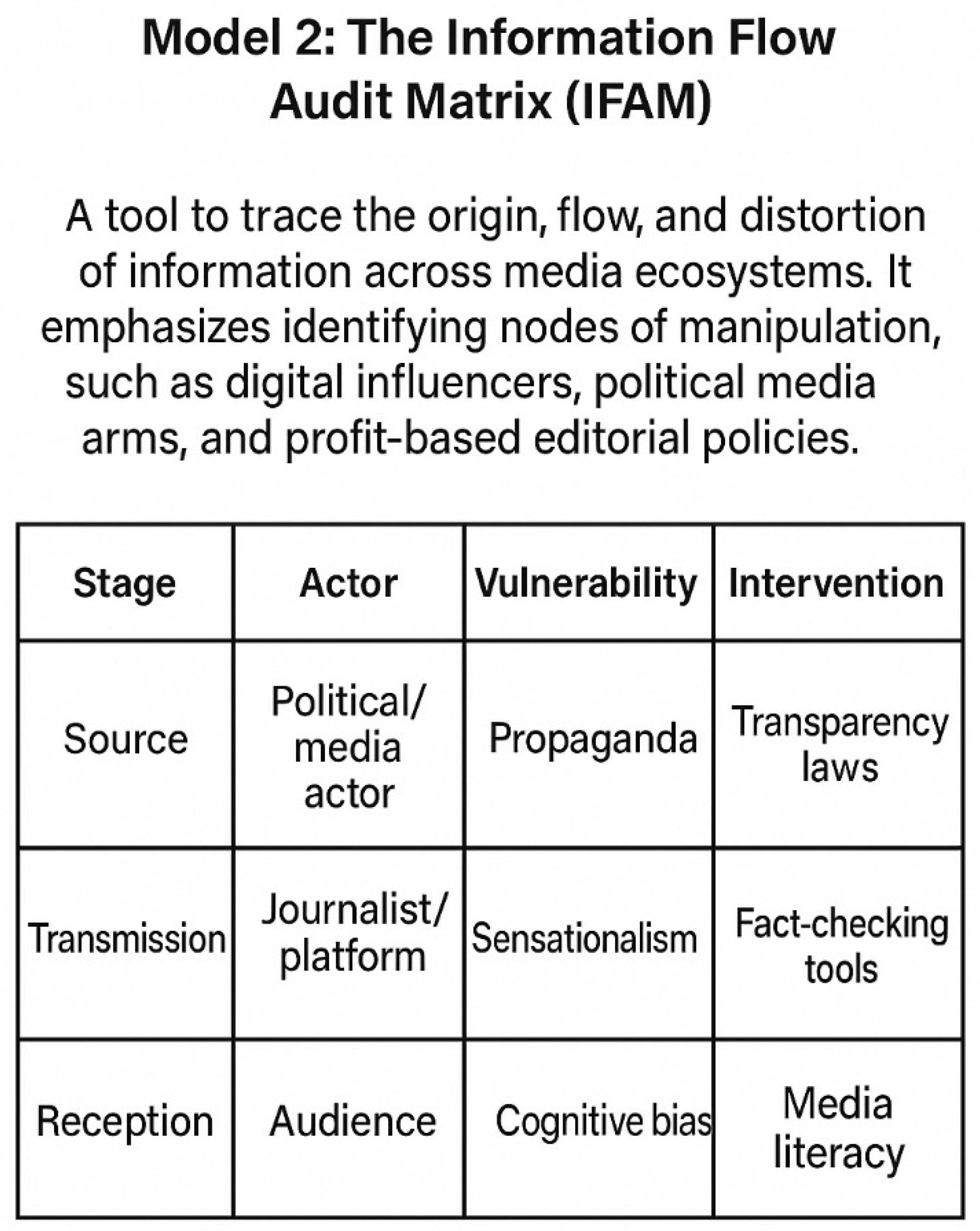

Model 2: The Information Flow Audit Matrix (IFAM)

A tool to trace the origin, flow, and distortion of information across media ecosystems. It emphasizes identifying nodes of manipulation, such as digital influencers, political media arms, and profit-based editorial policies.

8.2. Stage Actor Vulnerability Intervention

Source Political/media actor Propaganda Transparency laws

Transmission Journalist/platform Sensationalism Fact-checking tools

8.3. Reception Audience Cognitive bias Media literacy

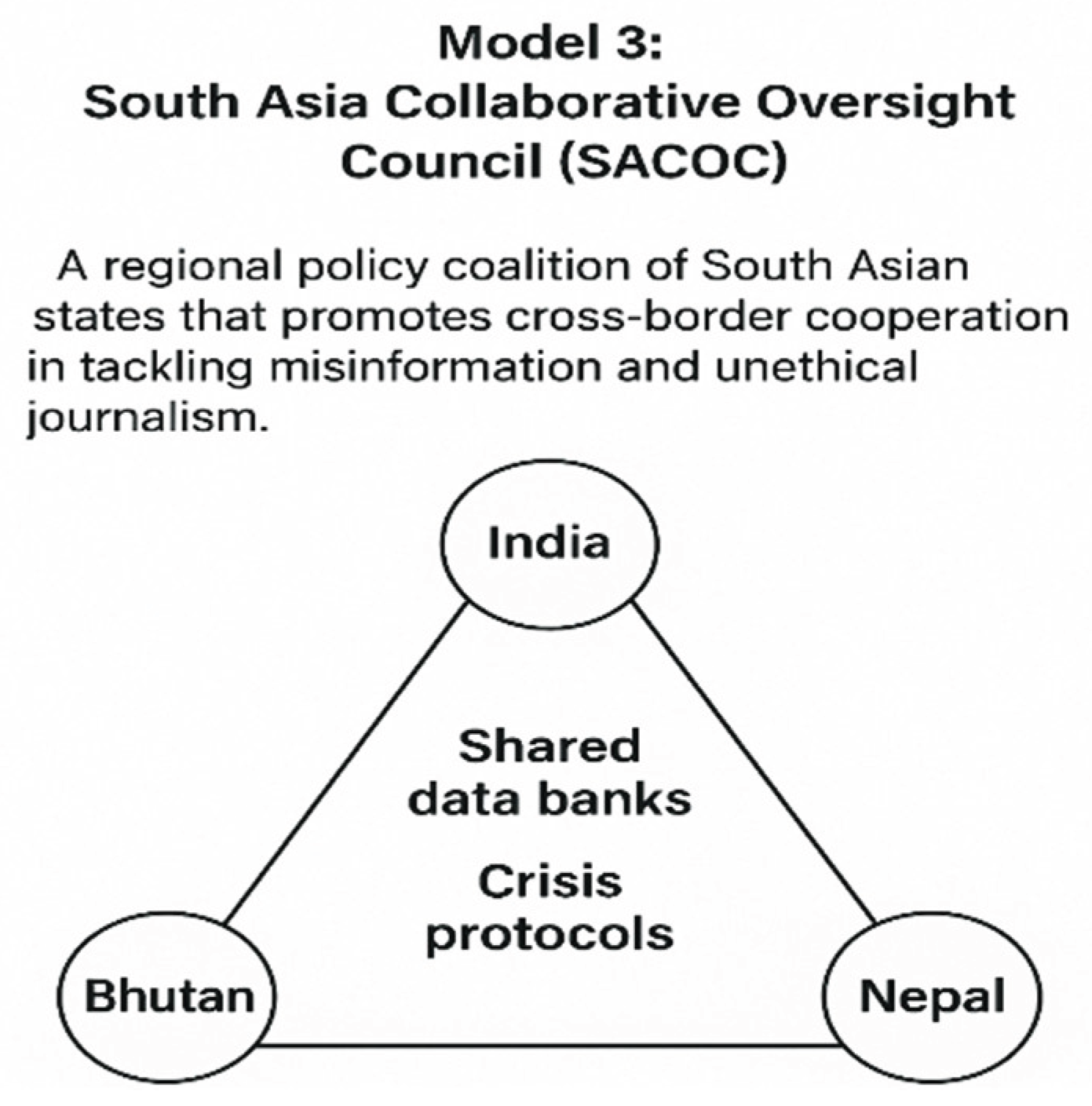

Model 3: South Asia Collaborative Oversight Council (SACOC)

A regional policy coalition of South Asian states that promotes cross-border cooperation in tackling misinformation and unethical journalism.

It includes shared data banks, crisis protocols, and periodic audits.

4. Alignment with Global Norms

These recommendations are consistent with international norms of press freedom, as outlined by UNESCO, Reporters Without Borders, and Article 19. However, regional customization is vital to ensure local applicability, especially in countries with hybrid political regimes and weak civil society protections.

9. Concluding Remarks

The phenomenon of boom journalism—characterized by sensationalism, speed over accuracy, emotional manipulation, and profit-driven reporting—has emerged as a dominant force in the media ecosystems of Bangladesh and the broader South Asian region. This study reveals how the structural and political vulnerabilities of developing democracies, combined with rapid digital penetration, have facilitated the rise of a media culture that prioritizes immediacy and virality over journalistic ethics and public responsibility.

In Bangladesh, the advent of digital news portals, 24/7 news channels, and unregulated social media platforms has intensified the competition for clicks, views, and audience attention. This pressure has led many journalists and media outlets to embrace boom-style reporting, often at the cost of factual accuracy, investigative depth, and ethical standards. Furthermore, political patronage and commercial ownership of media houses have deeply influenced editorial independence, creating an ecosystem where infotainment, political propaganda, and economic interests often override the core values of journalism.

Across South Asia, similar trends are evident, though they vary in intensity depending on the country-specific context. India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Nepal also face the consequences of boom journalism in the form of misinformation, communal polarization, and erosion of public trust in the media. The confluence of weak regulatory frameworks, declining media literacy, and increasing digital populism contributes to an unchecked boom culture that undermines democracy, exacerbates social conflicts, and weakens institutional accountability.

The research underscores that boom journalism is not merely a journalistic trend but a symptom of deeper systemic challenges, including political interference, economic pressures, and technological disruption. Addressing this requires not only media reform but also broader socio-political engagement with issues of transparency, governance, and digital ethics.

10. Recommendations

Establish Independent Regulatory Bodies

There is an urgent need to create or empower independent media regulatory authorities in South Asian countries that can monitor media content without political interference. These bodies should promote ethical standards, penalize disinformation, and encourage responsible reporting practices.

Support Journalist Training and Ethical Reorientation

Continuous professional development programs should be institutionalized to train journalists in fact-checking, data journalism, and crisis reporting. Newsrooms must also adopt clear ethical codes and provide internal mechanisms like ombudsman systems to address audience complaints and editorial concerns.

Foster Regional Collaboration

South Asian countries share similar media challenges and must coordinate cross-border media oversight, especially to counter misinformation and propaganda. Shared fact-checking initiatives, regional journalism awards for ethical reporting, and knowledge-sharing platforms can help resist the boom journalism wave.

Encourage Public Accountability and Audience Engagement

Media organizations must cultivate direct dialogue with audiences through town halls, feedback portals, and social listening tools. An informed and engaged audience can serve as a critical counterbalance to sensationalist tendencies.

Integrate Journalism with Civic Responsibility

Finally, journalism must reclaim its role as the fourth estate by aligning itself with civic responsibility, human rights, and democratic values. Media workers should be encouraged to see themselves not merely as content producers but as public interest communicators.

By implementing these recommendations, the media landscape in Bangladesh and South Asia can be steered away from the pitfalls of boom journalism towards a more sustainable, ethical, and accountable press system. The future of democracy in the region depends not only on political reforms but also on how truth is constructed, contested, and communicated through its media.

References

- Amnesty International. (2025). Silencing the truth: Bangladesh’s media under siege. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa13/xyz/2025/en/.

- Asaduzzaman, M., & Sultana, R. (2022). Digital Rumors and Communal Violence in Bangladesh: A Study of Social Media-Induced Mob Attacks. Dhaka University Journal of Communication, 5(2), 101–120. [CrossRef]

- Chakravartty, P., & Roy, S. (2017). Media pluralism redux: Towards new frameworks of comparative media studies. International Journal of Communication, 11, 3534–3550.

- Chowdhury, I. A. (1999). Media and Democratic Transition in Bangladesh. Journal of South Asian Development, 4(1), 67–88.

- Committee to Protect Journalists. (2024). CPJ urges interim leader Yunus to protect press freedom. https://cpj.org/2024/12/bangladesh-interim-leader-press-freedom/.

- Esser, F. (1999). Tabloidization of news: A comparative analysis of Anglo-American and German press journalism. European Journal of Communication, 14(3), 291–324.

- European Parliament. (2025). Resolution on the state of media freedom in Bangladesh (2025/2034(INI)). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/.

- Franklin, B. (1997). Newszak and News Media. Arnold.

- HRW. (2020). Bangladesh: Crackdown on Critics Continues Under Digital Security Act. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/11/19/bangladesh-crackdown-critics-continues-under-digital-security-act.

- Human Rights Watch. (2020). Bangladesh: Crackdown on Critics Continues Under Digital Security Act. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/11/19/bangladesh-crackdown-critics-continues-under-digital-security-act.

- Human Rights Watch. (2025). ‘Democracy in name only’: Bangladesh’s interim government and the repression of civil liberties. https://www.hrw.org/.

- International Federation of Journalists. (2025). Defend truth in Bangladesh: Emergency support for threatened journalists. https://www.ifj.org/.

- Islam, M. N. (2002). The Role of Media in Democratic Consolidation in Bangladesh. Media Asia, 29(3), 151–158.

- Islam, M. R., & Karim, M. (2021). Media and Politics in Bangladesh: A Complex Relationship. South Asian Journal of Politics and Policy, 2(1), 33–47.

- Keyes, R. (2004). The Post-Truth Era: Dishonesty and Deception in Contemporary Life. St. Martin’s Press.

- Khan, M. R. (2006). Media Under Military Rule: The Bangladesh Experience. Asian Journal of Communication, 16(2), 142–158.

- McChesney, R. W. (2004). The Problem of the Media: U.S. Communication Politics in the Twenty-First Century. Monthly Review Press.

- McManus, J. H. (1994). Market-Driven Journalism: Let the Citizen Beware? Sage.

- Mehta, N. (2019). India’s News Media: From Watchdog to Lapdog? South Asia Journal, 28(3), 55–72.

- Moffitt, B. (2016). The Global Rise of Populism: Performance, Political Style, and Representation. Stanford University Press.

- Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. Penguin Press.

- Rahman, T. (2012). Corporate Influence and the Decline of Journalistic Integrity in Bangladesh. South Asian Media Journal, 5(1), 43–60.

- Rahman, T. (2019). Patronage, Politics and the Press: The Transformation of News Media in Bangladesh. Media Asia, 46(1), 67–83.

- Reporters Without Borders. (2024a, November). RSF welcomes statement by Muhammad Yunus on false accusations against journalists. https://rsf.org/.

- Rights & Risks Analysis Group. (2025, May 5). Bangladesh: Press freedom throttled under Dr. Muhammad Yunus. https://www.rightsandrisks.org/.

- Siraj, S. A. (2009). Critical Analysis of Press Freedom in Pakistan. Journal of Media Studies, 24(1), 63–78.

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2017). Media capture: How money, digital platforms, and governments control the news. In I. Busuioc & J. Stiglitz (Eds.), Capture in the Digital Age (pp. 1–30). Columbia University Press.

- Stiglitz, J. E. (2017). Media capture: How money, digital platforms, and governments control the news. Columbia University Press.

- Sultana, S., & Mahmud, A. (2021). Clickbait Culture in Bangladeshi Online News: A Critical Discourse Analysis. Journal of New Media and Mass Communication, 85, 33–48.

- Tandoc, E. C. Jr. (2014). Journalism is twerking? How web analytics is changing the process of gatekeeping. New Media & Society, 16(4), 559–575. [CrossRef]

- Thussu, D. K. (2020). Media and Nationalism in South Asia: Reporting the Nation. Routledge.

- .U.S. Department of State. (2025). Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Bangladesh. https://www.state.gov/reports/.

- UNESCO. (2022). Media and Information Literacy Curriculum for Educators and Learners. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- United Nations Human Rights Council. (2024). Universal Periodic Review – Bangladesh 2024. https://www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/upr.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).