Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Baseline Methods for Data Reduction

2.2. Sensor Setup and Experimental Environment

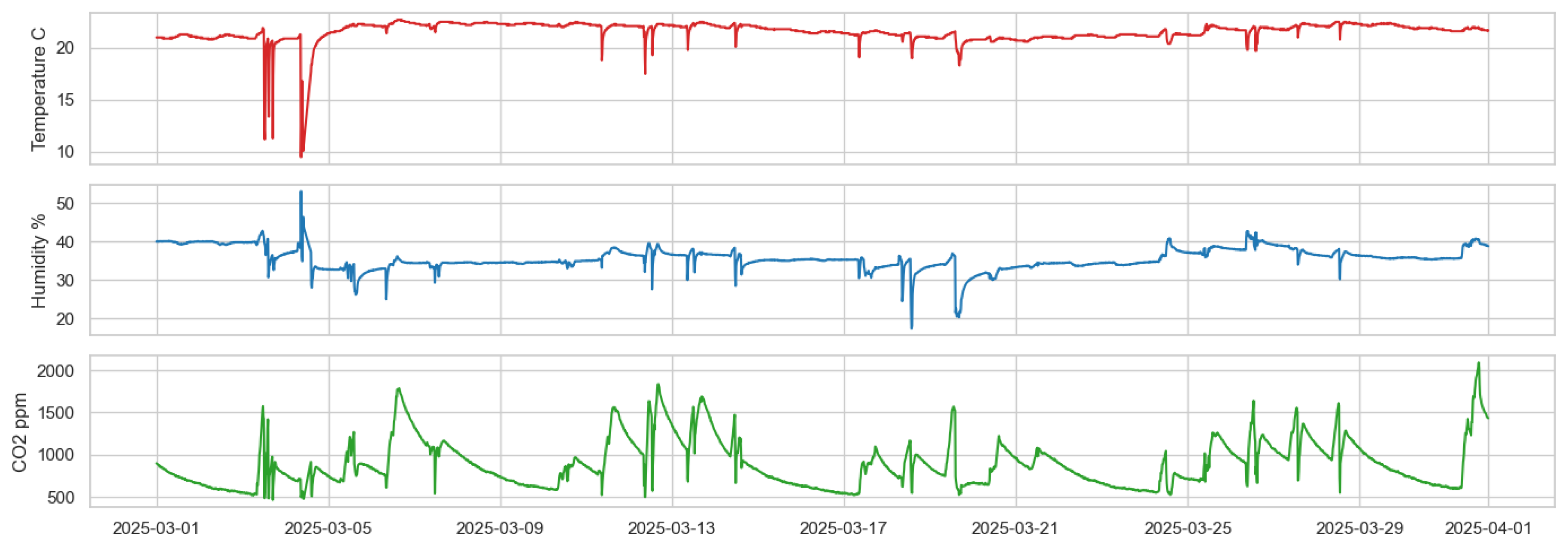

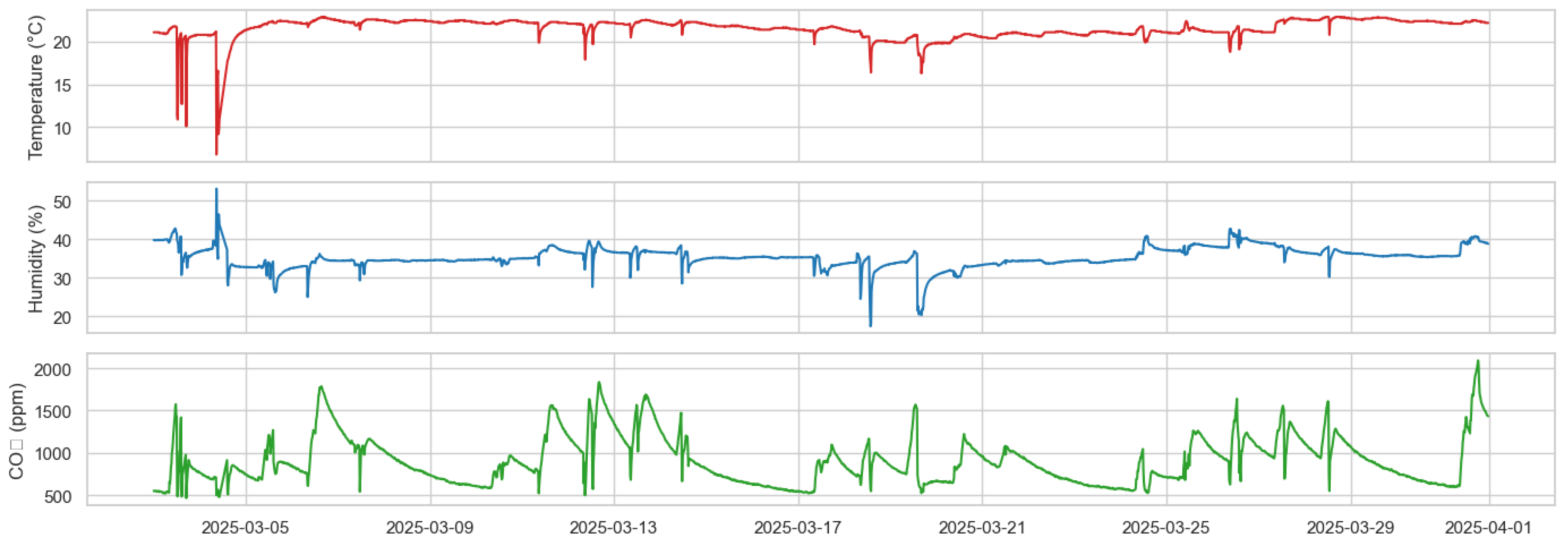

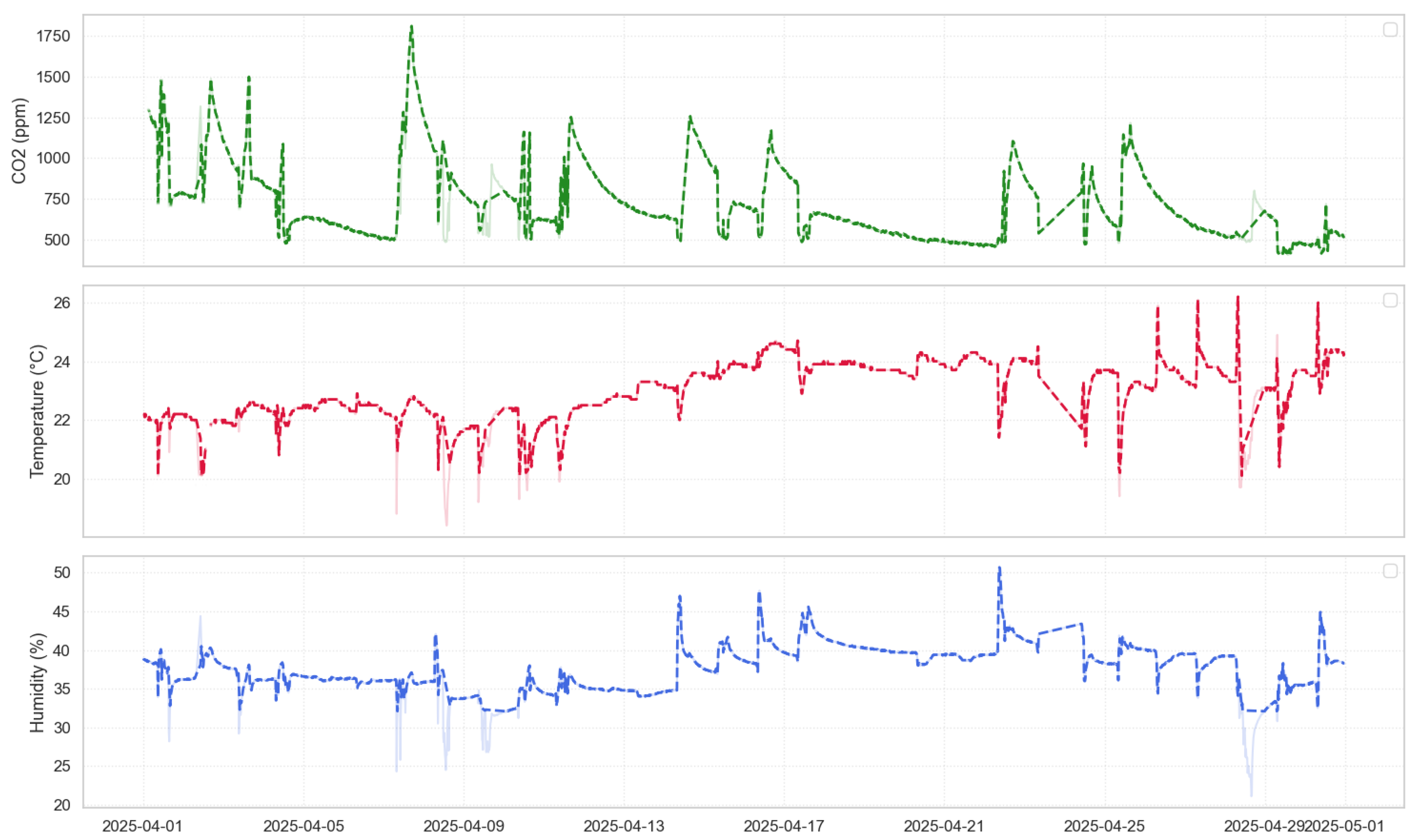

2.3. Data Acquisition

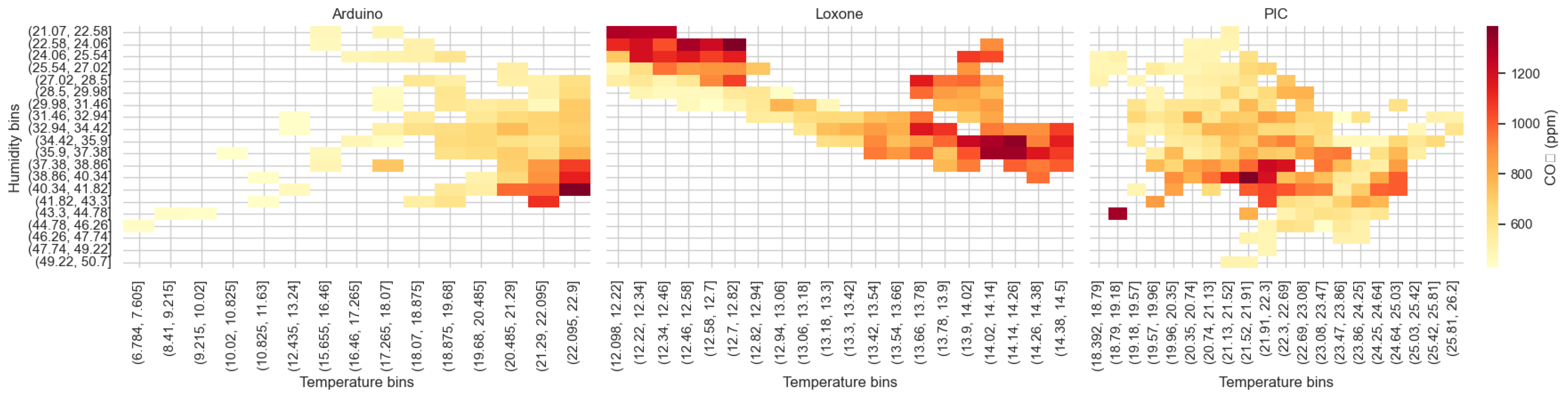

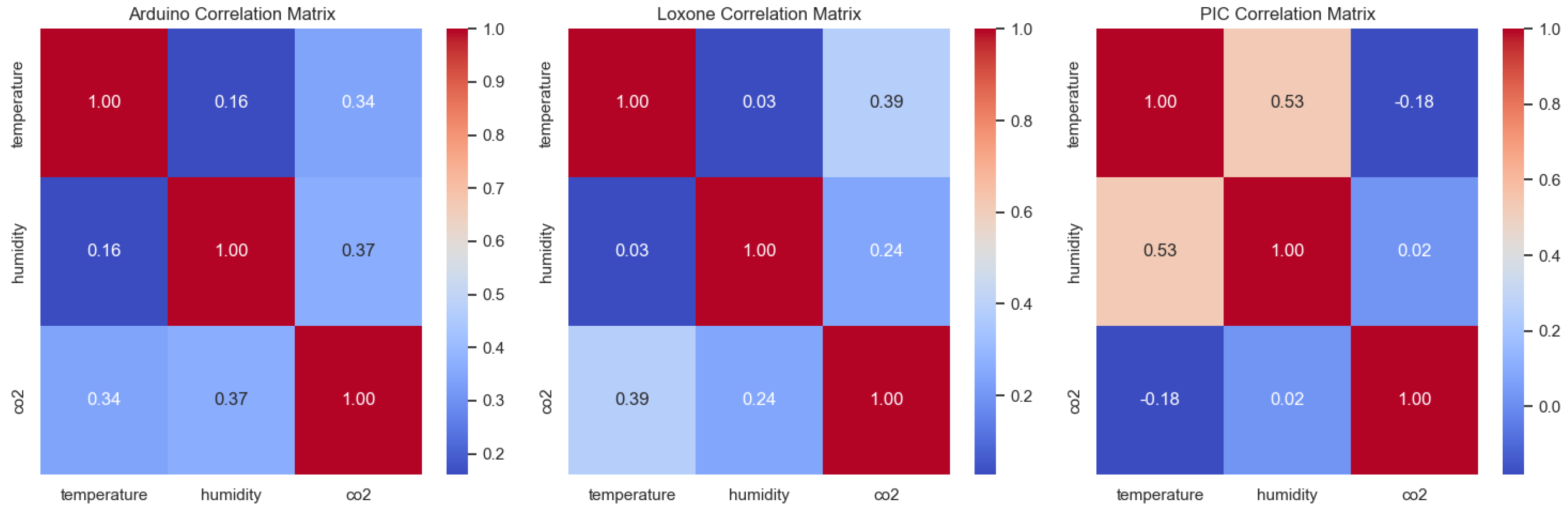

2.4. Correlation

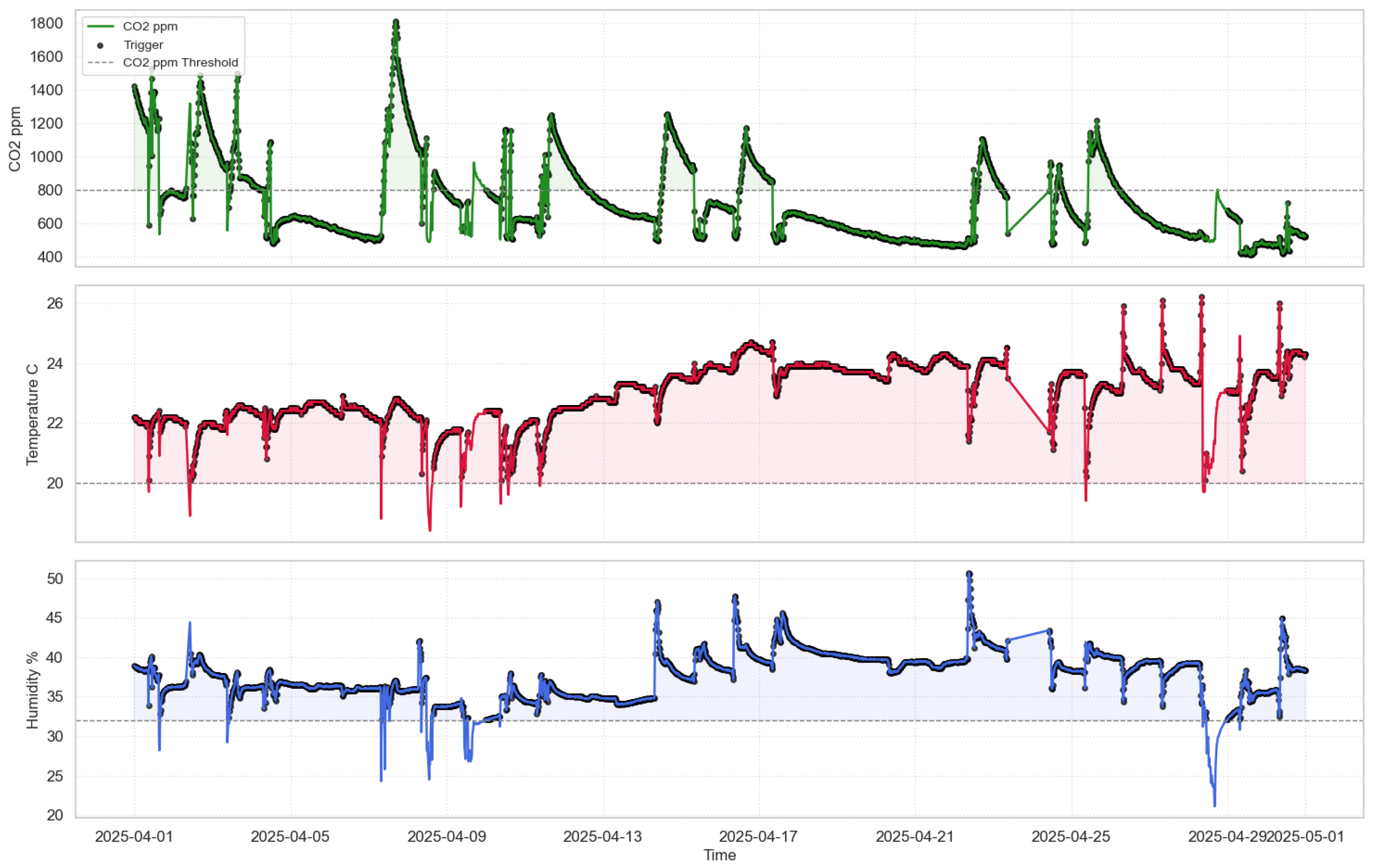

2.5. Trigger Justification

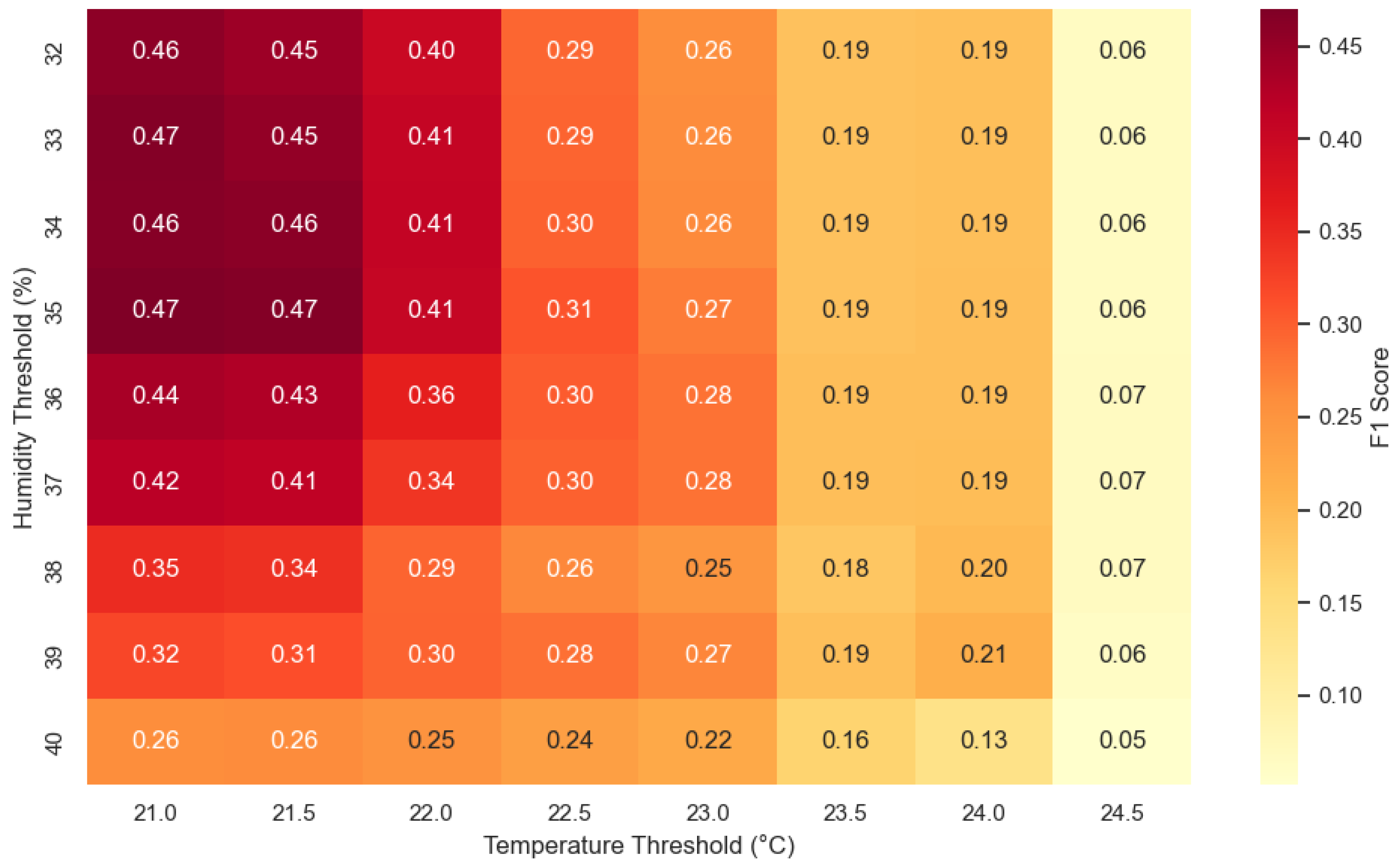

2.6. Threshold Selection

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, P.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Z. Effects of temperature, relative humidity and carbon dioxide concentration on concrete carbonation. Mag. Concr. Res. 2019, 72, 936–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Ameeri, A.S.; Rafiq, M.I.; Tsioulou, O.; Rybdylova, O. Impact of climate change on the carbonation in concrete due to carbon dioxide ingress: Experimental investigation and modelling. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 102594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leemann, A.; Moro, F. Carbonation of concrete: The role of CO2 concentration, relative humidity and CO2 buffer capacity. Mater. Struct. 2016, 50, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, P.; Yu, Z. Effects of environmental factors on concrete carbonation depth and compressive strength. Materials 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, A.; Zeeshan, M. Indoor temperature, relative humidity and CO2 monitoring and air exchange rates simulation utilizing system dynamics tools for naturally ventilated classrooms. Build. Environ. 2020, 180, 106980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedoni, R.; Romani, M.; Santangelo, P.E. A hybrid model for the assessment of indoor environmental quality in buildings: An insight into mold growth. Energy Rep. 2025, 13, 4114–4125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Cao, L.-X.; Lv, J.-R.; Wen, H.-Y.; Mao, L.-X.; Wang, X.-Q.; He, Z.-Z. Self-powered flexible sensor network for continuous monitoring of crop micro-environment and growth states. Measurement 2025, 242, 116002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofi, A.; Regita, J.J.; Rane, B.; Lau, H.H. Structural health monitoring using wireless smart sensor network – An overview. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 163, 108113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, V.P.; Reis, A.; Alves Salvador Filho, J.A. Assessing the evolution of structural health monitoring through smart sensor integration. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 64, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solórzano, A.; Eichmann, J.; Fernández, L.; Ziems, B.; Jiménez-Soto, J.M.; Marco, S.; Fonollosa, J. Early fire detection based on gas sensor arrays: Multivariate calibration and validation. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 352, 130961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshmiry, A.; Hassani, S.; Mousavi, M.; Dackermann, U. Effects of environmental and operational conditions on structural health monitoring and non-destructive testing: A systematic review. Buildings 2023, 13(4), 918, https://www.mdpi.com/2075-5309/13/4/918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; Wang, P. A method for compressing AIS trajectory based on the adaptive core threshold difference Douglas–Peucker algorithm. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Seman, M.T.; Abdullah, M.N.; Ishak, M.K. Monitoring temperature, humidity and controlling system in industrial fixed room storage based on IoT. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2020, 15, 3588–3600. [Google Scholar]

- Entezami, A.; Sarmadi, H.; Behkamal, B. Long-term health monitoring of concrete and steel bridges under large and missing data by unsupervised meta learning. Eng. Struct. 2023, 279, 115616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plageras, A.P.; Psannis, K.E.; Stergiou, C.; Wang, H.; Gupta, B.B. Efficient IoT-based sensor BIG Data collection–processing and analysis in smart buildings. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2018, 82, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofianidis, I.; Konstantakos, V.; Nikolaidis, S. Reducing Energy Consumption in Embedded Systems Applications. Technologies 2025, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Somagattu, P.; Singh, V.; Kalra, M. IoT-Based Data Storage for Cloud Computing Applications. In Advances in Artificial Intelligence and Data Engineering; Chiplunkar, N.N., Fukao, T., Eds.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Singapore, 2021; Volume 1133, pp. 1455–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Sobral, V.A.; Nelson, J.; Asmare, L.; Mahmood, A.; Mitchell, G.; Tenkorang, K.; Todd, C.; Campbell, B.; Goodall, J.L. A Cloud-Based Data Storage and Visualization Tool for Smart City IoT: Flood Warning as an Example Application. Smart Cities 2023, 6, 1416–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Na, J.; Zhang, B. Autonomous Internet of Things (IoT) Data Reduction Based on Adaptive Threshold. Sensors 2023, 23, 9427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.-H.; Kim, K.-M.; Kim, S.; Kwak, J.W. Lossless Data Compression for Time-Series Sensor Data Based on Dynamic Bit Packing. Sensors 2023, 23, 8575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Alsheikh, M.; Lin, S.; Niyato, D.; Tan, H.P. Machine Learning in Wireless Sensor Networks: Algorithms, Strategies, and Applications. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2014, 16, 1996–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Li, H.; Pan, D. An Improved Piecewise Aggregate Approximation Based on Statistical Features for Time Series Mining. Adv. Data Min. Appl. 2010, 6440, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.-H.; Kang, Y.-S. Distance- and Momentum-Based Symbolic Aggregate Approximation for Highly Imbalanced Classification. Sensors 2022, 22, 5095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Huang, Z.; Ge, P.; Gao, F.; Gao, F. Adaptive De-noising of Photoacoustic Signal and Image Based on Modified Kalman Filter. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.10262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Frusque, G.; Li, Q.; Fink, O. Acceleration-Guided Acoustic Signal Denoising Framework Based on Learnable Wavelet Transform Applied to Slab Track Condition Monitoring. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.05365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, J.; Smith, L.; Thompson, R. R Field Phase Shift Defect Signal Peak-to-Peak vs. Excitation Frequency. NDT E Int. 2022, 130, 102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweinzer, P. Variance Compression Leads to Participation Under Sufficient Variance Aversion. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 291, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyaya, V.; Salim, M. Compressive Sensing: Methods, Techniques, and Applications. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1099, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, G.; Chehri, A. Entropy-Based Algorithms for Signal Processing. Entropy 2020, 22, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Microchip Technology. PIC16(L)F19155/56/75/76/85/86 Data Sheet; Microchip Technology Inc.: Chandler, AZ, USA, 2017; Available online: https://ww1.microchip.com/downloads/en/DeviceDoc/PIC16LF19155-56-75-76-85-86-Data-Sheet-40001923B.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Hu, W.; Chen, Y. Revisiting PCA for Time Series Reduction in Temporal Dimension. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.19423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, M.-S.; Kwak, J.-H.; Lee, C.-H. Fast Shape Matching Algorithm Based on the Improved Douglas–Peucker Algorithm. KIPS Trans. Softw. Data Eng. 2016, 5, 497–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofianidis, I.; Konstantakos, V.; Nikolaidis, S. Reducing Energy Consumption in Embedded Systems Applications. Technologies 2025, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Method | Description | Reduced | MAE |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDP [12] | Keeps only the key points that form the waveform. | 68% | 0.0091 |

| PAA [22] | Reduces the signal dimension by dividing it into segments of equal length. | 62% | 0.0103 |

| vSAX [23] | Converts PAA values to discrete characters. | 65% | 0.0125 |

| Wavelet Tr. [25] | Decomposes a signal into components and removes small signal coefficients. | 70% | 0.0082 |

| Kalman Filter [24] | Smoothes and reduces noise | 60% | 0.0069 |

| Compressive Sensing [28] | Reconstructs signals from fewer samples. | 72% | 0.0073 |

| Delta Encoding [] | Reduces the redundancy of similar values | 50% | 0.0132 |

| Peak-to-Peak [26] | Keeps only significant peaks and valleys of the signal. | 59% | 0.0108 |

| Entropy-Based [29] | Preserves those signal segments with high information content. | 64% | 0.0099 |

| Variance-Based [27] | Compresses data to a value exceeding the threshold. | 61% | 0.0106 |

| T thresh. (°C) | H thresh. (%) | Precision | Recall | F1 | Trigger % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20.5 | 31 | 0.311 | 0.990 | 0.473 | 95.4 |

| 20.0 | 31 | 0.310 | 0.996 | 0.473 | 96.3 |

| 20.5 | 35 | 0.329 | 0.842 | 0.473 | 76.8 |

| 20.0 | 35 | 0.328 | 0.847 | 0.473 | 77.3 |

| 19.5 | 35 | 0.327 | 0.848 | 0.472 | 77.6 |

| Method | Description | Reduced (%) | MAE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 to 1 | CO2 active, if T > 20.5 °C and H > 31% | 41.9% | 0.0089 | 0.0117 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).