1. Introduction

In recent years, DNA has taken on a new role far beyond its traditional identity as the genetic blueprint of life. Scientists are now using it as a powerful tool to build programmable devices—tiny biological machines that can sense their surroundings and respond accordingly. These programmable DNA devices are designed to detect specific molecules or environmental signals and trigger a controlled action, such as producing a protein, changing shape, or releasing a chemical signal [

1,

2]. What makes these DNA-based systems particularly exciting is their potential to revolutionize how we monitor and respond to changes in health, agriculture, and the environment. Unlike conventional biosensors that often rely on proteins or electronics, DNA devices can be precisely engineered, are highly adaptable, and can function in complex biological settings. They can be designed to respond in real-time, making them incredibly useful for rapid diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and even crop management [

3,

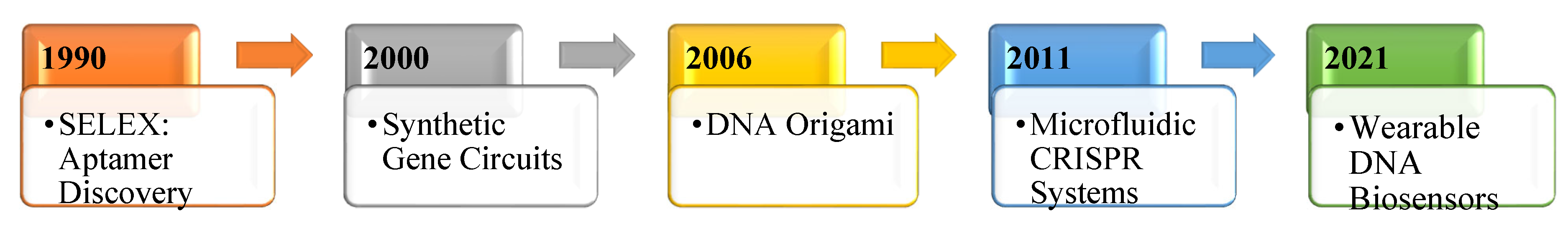

4]. The idea of using DNA in this way isn't entirely new, but it has gained serious momentum over the past two decades. Breakthroughs like DNA origami, where scientists fold strands of DNA into intricate nanostructures, and synthetic gene circuits, which function like programmable logic gates in cells, have opened the door to a new generation of smart biological tools [

5,

6]. With these innovations, DNA is no longer just the code of life—it's becoming a platform for building responsive, intelligent systems, see

Figure 1.

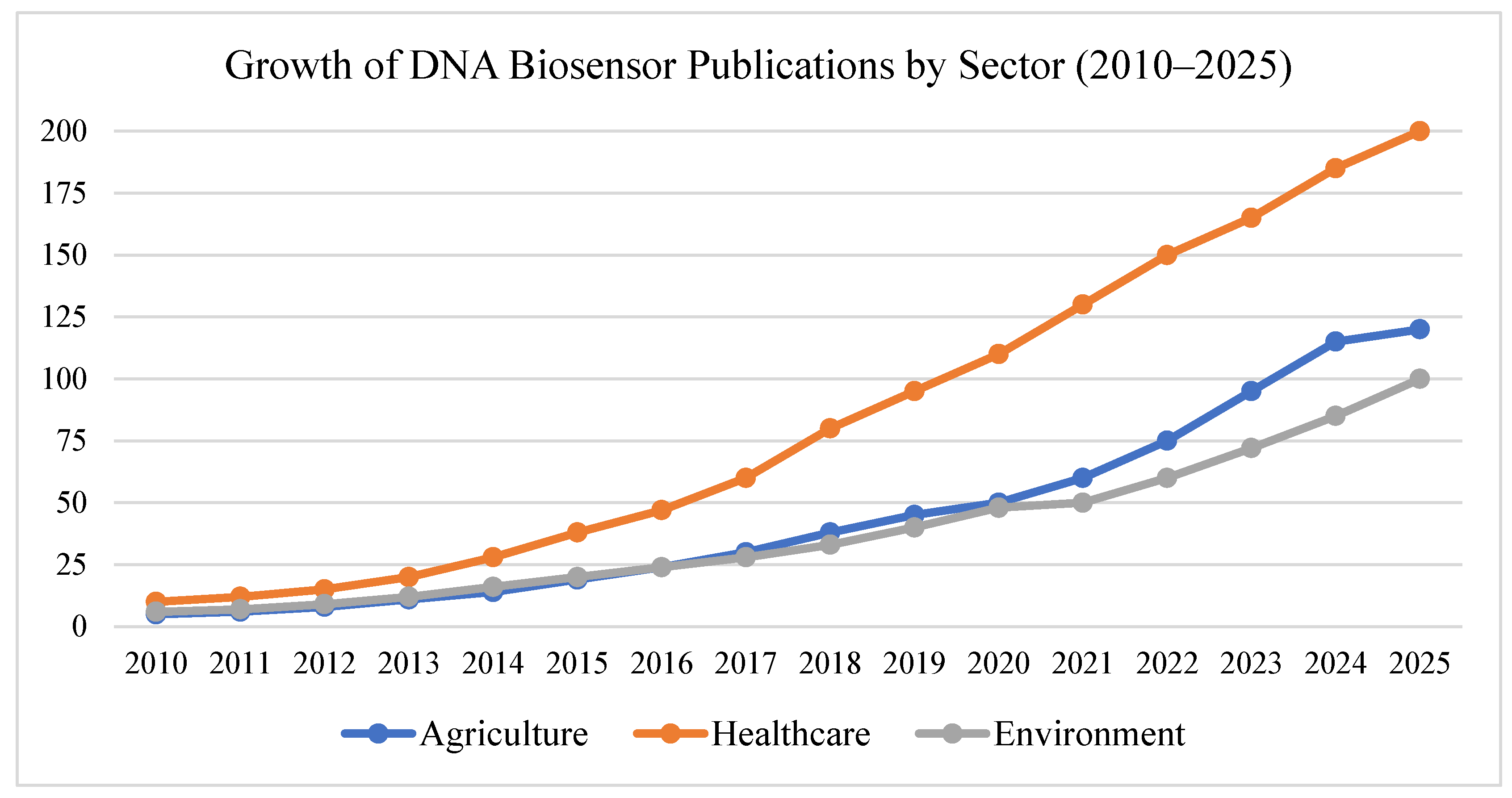

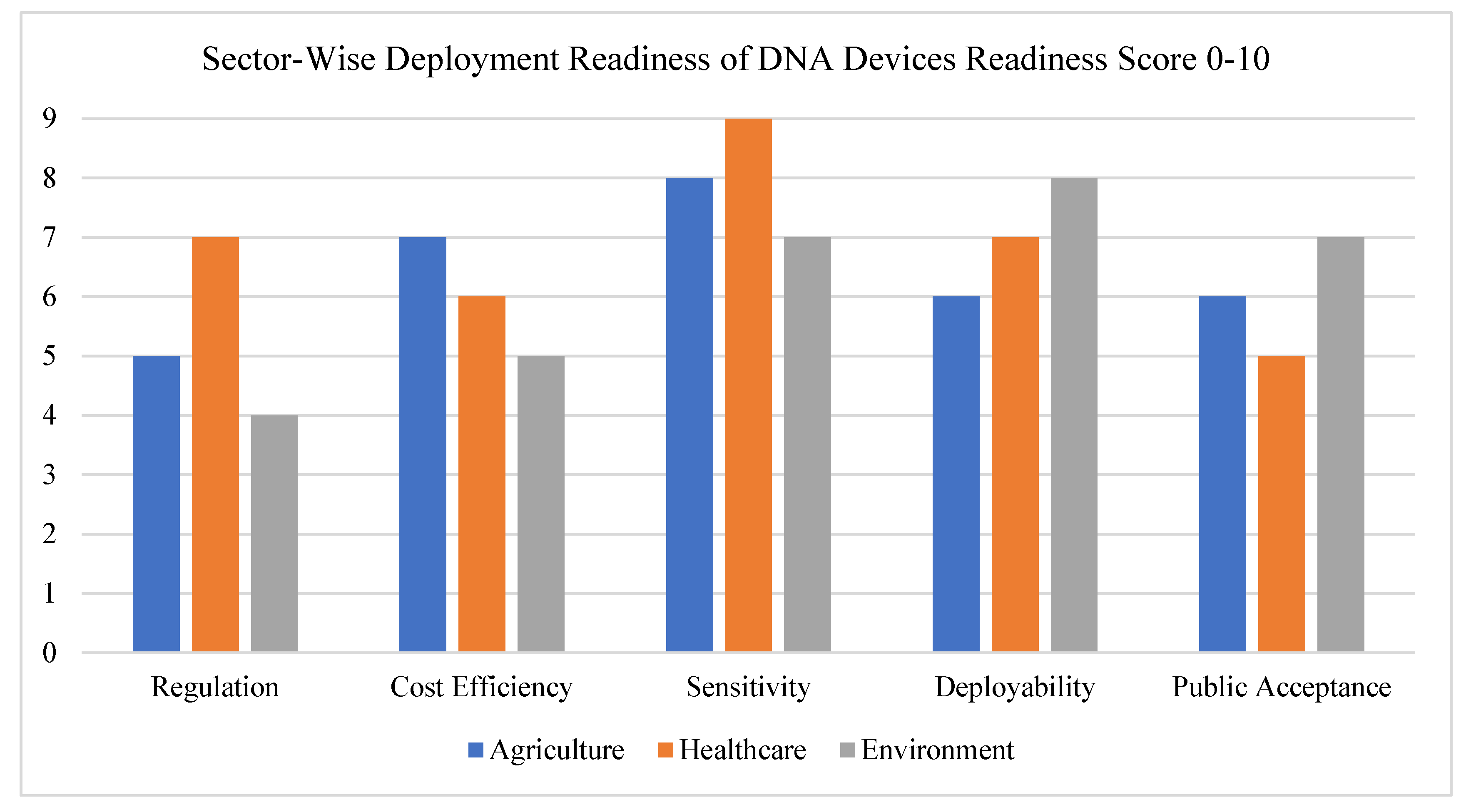

Today, these programmable DNA devices are being explored in a wide range of areas. In agriculture, they could help detect plant pathogens or nutrient imbalances in soil. In healthcare, they’re enabling fast, low-cost diagnostics that don’t require lab equipment. In environmental science, researchers are pairing them with environmental DNA (eDNA) to monitor biodiversity or detect pollutants in water and soil [

7,

8]. Despite all these promising applications, research in this field has largely remained siloed. Most studies focus on one specific sector—medicine, agriculture, or the environment—without considering how these tools could work together across disciplines. But the real promise lies in integrating these systems to create a unified platform of living, DNA-powered sensors that can tackle global challenges in a smarter, more connected way, see

Figure 2.

In this review, we’ll take a closer look at the current landscape of programmable DNA devices: how they work, where they’re being used, what limitations they still face, and what the future might hold. Our goal is to highlight not just the technical advances, but the broader potential of these systems to transform how we interact with the living world.

2. Core Technologies Behind Programmable DNA Devices

The ability to design DNA that not only stores information but also senses, computes, and acts is at the heart of programmable DNA devices. Several foundational technologies make this possible. Each of these tools harnesses different aspects of DNA’s structure and behavior to create highly specific and controllable biosensing systems.

2.1. DNA Aptamers

DNA aptamers are short, synthetic strands of DNA (or RNA) that can fold into precise three-dimensional shapes to bind specific targets, such as proteins, small molecules, or even metal ions [

9]. Think of them as the nucleic acid version of antibodies—only easier to produce and modify in the lab. Because they can be tailored to recognize a wide variety of molecules, aptamers are widely used in applications like pathogen detection, hormone sensing, and monitoring environmental pollutants. Their stability, low cost, and ability to function in diverse environments make them ideal for field-deployable biosensors, including wearable and paper-based formats [

10], see

Figure 3.

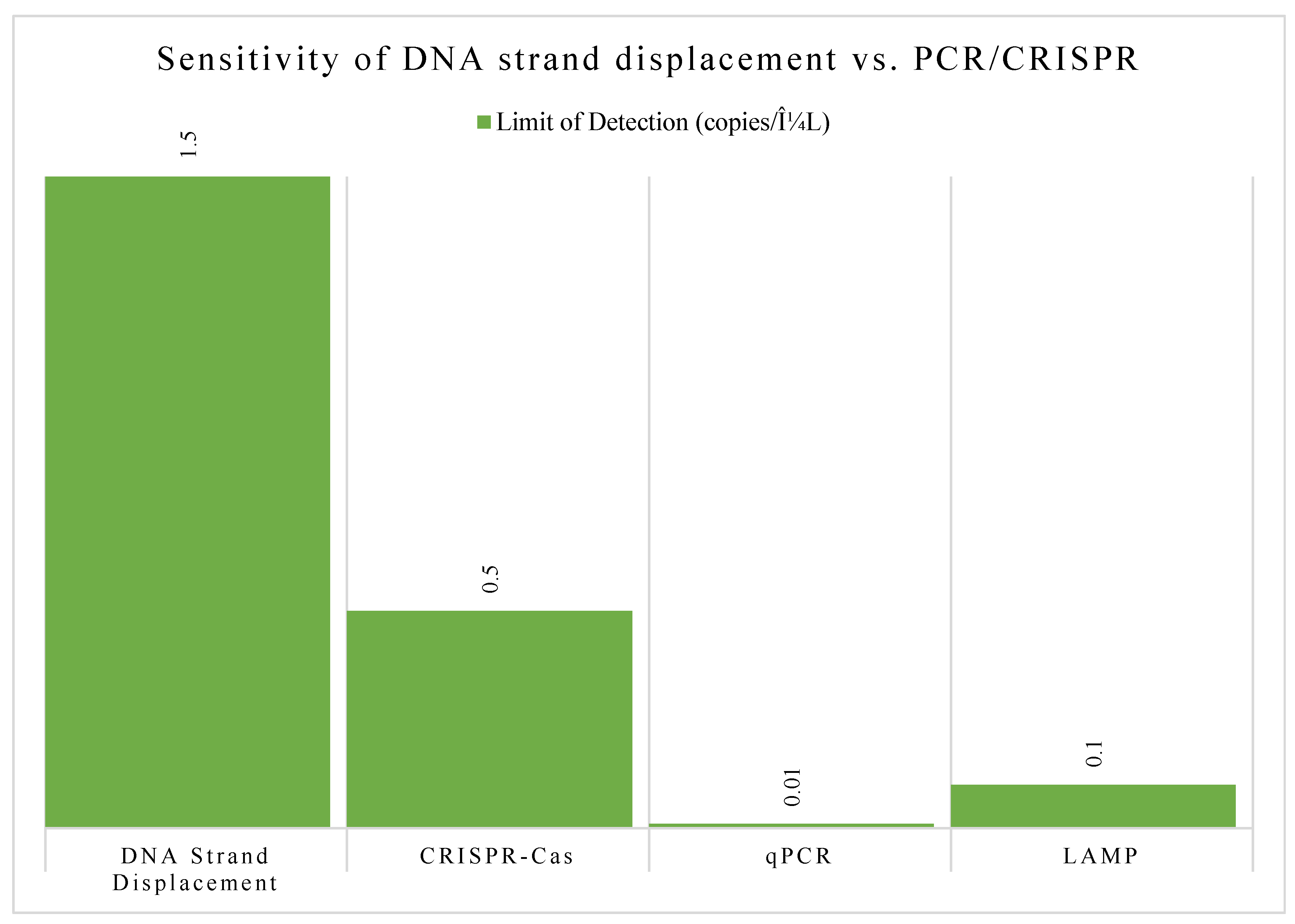

2.2. DNA Strand Displacement Systems

Strand displacement is a clever trick where a single strand of DNA can "invade" a double-stranded DNA molecule and displace one of the original strands. This dynamic interaction can be designed to act like a switch or a gate, allowing for the creation of DNA-based logic circuits that perform calculations or control signal flow [

11], see

Figure 4.

These systems are now being used to build diagnostic tools that light up in the presence of specific biomarkers, as well as smart drug delivery platforms that release therapeutic molecules only under defined conditions [

12]. The beauty of strand displacement is that it brings computation into the realm of molecular biology—with no need for enzymes or electronic components.

2.3. DNA Origami and Nanostructures

DNA origami takes advantage of the predictable base-pairing rules of DNA to fold long strands into precise 2D or 3D shapes, much like paper origami but at the nanoscale [

13]. These structures can act as molecular scaffolds or delivery vehicles, offering incredible precision when targeting cells or tissues.

Researchers are using DNA nanostructures in targeted drug delivery, where they can carry therapeutic agents and release them in response to specific triggers. They’re also being explored for environmental applications, such as detecting toxins in water or serving as nanoscale platforms for capturing pollutants [

14].

2.4. Synthetic Gene Circuits

Synthetic gene circuits are engineered networks of DNA sequences that function like biological computer programs. They’re introduced into living cells—bacterial, plant, or human—and can be designed to sense internal or external stimuli, process that information, and produce a functional response [

15], see

Table 1.

For example, a gene circuit might detect inflammation markers in the body and trigger the production of anti-inflammatory proteins. Or it could sense nutrient levels in soil and cause a plant root to express specific transporters. These circuits bring together sensing and actuation in one seamless system, enabling powerful applications in smart therapeutics, biosustainable agriculture, and environmental remediation [

16].

3. Applications in Agriculture

As global food systems face growing pressure from climate change, emerging diseases, and soil degradation, there is an urgent need for smarter, more responsive agricultural technologies. Programmable DNA devices offer a promising new toolkit—capable of sensing plant health, soil conditions, and environmental stressors in real time. By embedding molecular-level intelligence into crops and farming systems, these technologies could help pave the way toward more sustainable, resilient agriculture.

3.1. Pathogen Detection in Plants

Early detection of plant pathogens is critical for minimizing crop loss and preventing outbreaks. Traditional diagnostics, however, often rely on lab-based testing and arrive too late to stop the spread of infection. This is where aptamer-based and CRISPR-based DNA biosensors come into play. Aptamers can be engineered to bind specific molecules secreted by pathogens, while CRISPR systems can detect pathogen DNA or RNA directly at the site of infection [

17,

18]. These programmable sensors can be embedded directly into plant tissues—such as roots or leaves— where they act as sentinels, detecting threats before visible symptoms appear. In some designs, the detection of a pathogen automatically triggers a response, such as activating a defense gene or releasing a protective molecule.

This kind of real-time, in vivo monitoring system could significantly reduce the need for broad-spectrum pesticides and enable precision agriculture at the molecular level.

3.2. Soil and Nutrient Monitoring

Soil health is the foundation of productive agriculture, yet monitoring its chemical composition—like levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, or heavy metals—is still a major challenge for many farmers. DNA-based sensors offer an elegant solution. These sensors can be engineered to recognize specific ions or molecules and provide a measurable signal, such as fluorescence or color change, in response [

19]. For instance, a DNA strand might be designed to fold into a particular shape only in the presence of nitrate, acting as a biological switch. Other sensors use strand displacement reactions or aptamer binding to report the presence of toxic metals like lead or cadmium [

20].

Such tools can be integrated into soil probes, seed coatings, or even microbial biosensors living in the rhizosphere, giving farmers real-time data on soil nutrient levels and potential contaminants. This opens the door to precision fertilization, reducing both costs and environmental impact.

3.3. Stress-Responsive Crops

Extreme temperatures, drought, and salinity are major threats to global food security, especially in arid and semi-arid regions. Through synthetic biology, researchers are beginning to design crops equipped with DNA-based genetic circuits that help them sense and respond to these stresses automatically. For example, a synthetic circuit might detect rising salt concentrations in soil and activate genes that protect plant cells from osmotic damage [

21]. Others might sense oxidative stress during drought and trigger the expression of antioxidants or water-conserving proteins.

These systems work much like a thermostat, turning protective mechanisms on or off as needed, and could be tailored for specific regional climates or soil conditions. While still in the early stages, this approach has the potential to create crops that can adapt in real time to environmental challenges, reducing the need for external inputs and boosting long-term resilience [

22]. By embedding intelligence into the biological fabric of crops and soils, programmable DNA devices have the potential to transform agriculture—from reactive to proactive, precise, and adaptive. As these tools become more robust and field-ready, they could be key to building a more sustainable and food-secure future.

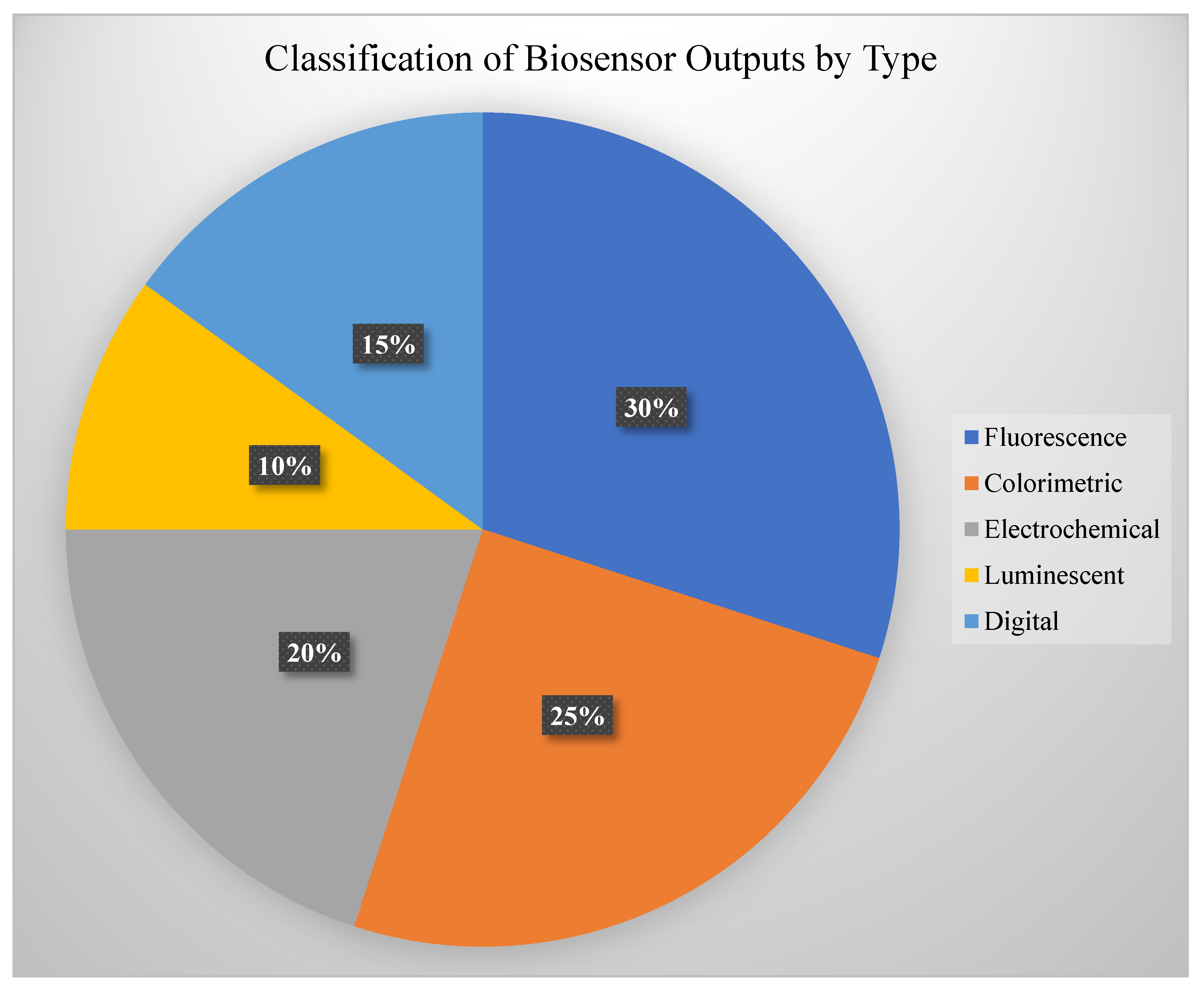

4. Applications in Healthcare

Healthcare is rapidly evolving toward a more personalized, responsive, and accessible future—and programmable DNA devices are at the heart of this transformation. These tools enable sensitive detection, intelligent drug delivery, and dynamic monitoring of health conditions, all at the molecular level. From diagnostics that fit in your pocket to implantable gene circuits that act only when needed, DNA-based technologies are opening the door to a new generation of smart healthcare systems, see

Figure 5.

4.1. Smart Point-of-Care Diagnostics

One of the most impactful uses of DNA devices in medicine is in rapid, point-of-care diagnostics. Paper-based tests that integrate DNA sensors—often using aptamers or CRISPR-based detection tools—are now able to detect viruses like Zika, HIV, and SARS-CoV-2 with high sensitivity and accuracy, even outside of laboratory settings [

23,

24]. These sensors are typically designed so that when they encounter a target—such as a viral RNA sequence or a cancer-specific biomarker—they produce a visible color change or fluorescence. Some systems even amplify the signal using DNA strand displacement reactions or isothermal amplification, making the devices both simple and powerful.

Importantly, many of these platforms are low-cost, portable, and fast, making them ideal for use in rural clinics, emergency settings, or even at home. They also show promise for detecting therapeutic drug levels, enabling on-the-spot monitoring for patients on chemotherapy, anticoagulants, or other critical treatments [

25].

4.2. Implantable DNA Devices

Beyond external diagnostics, researchers are designing implantable DNA-based systems that operate within the body. These typically involve synthetic gene circuits engineered into living cells—such as probiotic bacteria or human-derived cells—that reside in tissues and act only when certain disease conditions arise [

26]. For example, a synthetic circuit might detect an inflammatory cytokine associated with Crohn’s disease and trigger the production of an anti-inflammatory protein. Another system could sense hypoxic conditions in tumors and release therapeutic agents to target cancer cells [

27].

These DNA devices function like “molecular watchdogs,” constantly scanning the internal environment and acting only when needed. This minimizes off-target effects and reduces the need for continuous drug administration. While still under development, implantable gene circuits have the potential to revolutionize how we treat chronic diseases, infections, and cancer—from reactive care to responsive, self-regulated therapy.

4.3. Personalized Medicine

Perhaps the most exciting frontier for programmable DNA technology lies in personalized medicine. Advances in cell-free DNA circuits—meaning systems that operate outside of living cells—are enabling real-time metabolic monitoring tailored to individual patients [

28]. These devices can analyze specific biomarkers in blood, saliva, or sweat and respond dynamically. For instance, a DNA sensor might detect elevated glucose levels in a diabetic patient and wirelessly signal a device to deliver insulin. Others could monitor cancer markers, hormone levels, or immune responses in real time, helping doctors make data-driven decisions with unprecedented speed and accuracy.

Such technologies bring us closer to a vision of medicine where treatment is no longer “one-size-fits-all,” but custom-built and constantly updated based on each person’s molecular profile. With DNA devices acting as the interface between biology and technology, the future of healthcare becomes more precise, proactive, and personal. By harnessing the power of DNA not just as genetic material but as an intelligent, programmable tool, these innovations are redefining the landscape of medicine. As DNA devices continue to evolve, they hold immense promise for transforming healthcare into a system that is faster, smarter, and deeply personalized.

5. Applications in Environmental Monitoring

As our ecosystems face mounting pressures from climate change, pollution, and biodiversity loss, the need for sensitive, real-time environmental monitoring has never been more critical. Programmable DNA devices are emerging as powerful tools for assessing and responding to these environmental challenges. Whether embedded in soil, suspended in water, or living within microbial communities, these devices offer a way to “listen in” on the molecular signals of the environment—and even intervene when necessary.

5.1. eDNA-Driven Sensing Systems

Environmental DNA (eDNA)—traces of genetic material left behind by organisms in soil, water, or air—has become an essential tool in biodiversity research. But beyond passive sampling, programmable DNA devices are pushing the boundaries of what eDNA can do. New sensing systems are being developed that can capture, decode, and analyze eDNA on-site to detect the presence of specific species, invasive organisms, or even microbial pathogens [

29]. These devices often use strand displacement or CRISPR-based systems to identify DNA sequences of interest with high specificity and speed. Unlike traditional lab-bound eDNA analysis, these programmable platforms are compact, field-deployable, and responsive—meaning they could one day provide real-time ecological surveillance in forests, oceans, or agricultural zones. Moreover, coupling eDNA sensing with signal amplification or wireless communication opens the door to autonomous, remote sensing networks [

30].

5.2. Living Biosensors in Microbial Consortia

Nature already uses microbes to break down pollutants, cycle nutrients, and maintain ecological balance. Now, synthetic biology is allowing us to reprogram microbial communities to do these jobs more precisely and transparently. By embedding DNA logic circuits into bacteria or other microbes, researchers can create living biosensors that fluoresce, change color, or even self-destruct in the presence of environmental toxins like heavy metals, pesticides, or industrial waste [

31]. These engineered microbes can be deployed in soil, rivers, or wastewater treatment facilities to monitor pollution levels continuously and locally.

Some of these systems are designed to be part of larger microbial consortia, where different species communicate using synthetic DNA-based signaling molecules. This allows for more robust and nuanced environmental sensing, as multiple signals can be interpreted simultaneously [

32].

5.3. Climate-Responsive Systems

One of the most forward-thinking applications of programmable DNA technology is the development of climate-responsive synthetic ecosystems. These systems involve engineered microbes or plants that can sense environmental changes—such as rising CO₂ levels, temperature shifts, or nitrogen imbalances—and then modulate their behavior to stabilize the ecosystem.

For example, synthetic microbes could be designed to fix nitrogen more efficiently under drought conditions, or to activate carbon-sequestering pathways in response to greenhouse gas fluctuations [

33]. DNA-based gene circuits serve as the “decision-making” units in these organisms, controlling when and how they respond to specific environmental signals, see

Table 2 and

Figure 6. While still largely in the experimental phase, these adaptive, DNA-programmed ecological interventions have the potential to support climate resilience in agricultural soils, forests, wetlands, and other vulnerable ecosystems [

34].

By turning DNA into a platform for sensing, interpreting, and responding to environmental signals, we are moving toward a future where ecosystems can monitor themselves and even heal in real-time. These advances not only enhance our ability to protect biodiversity and human health—but also reflect a shift toward a smarter, more integrated relationship with the natural world.

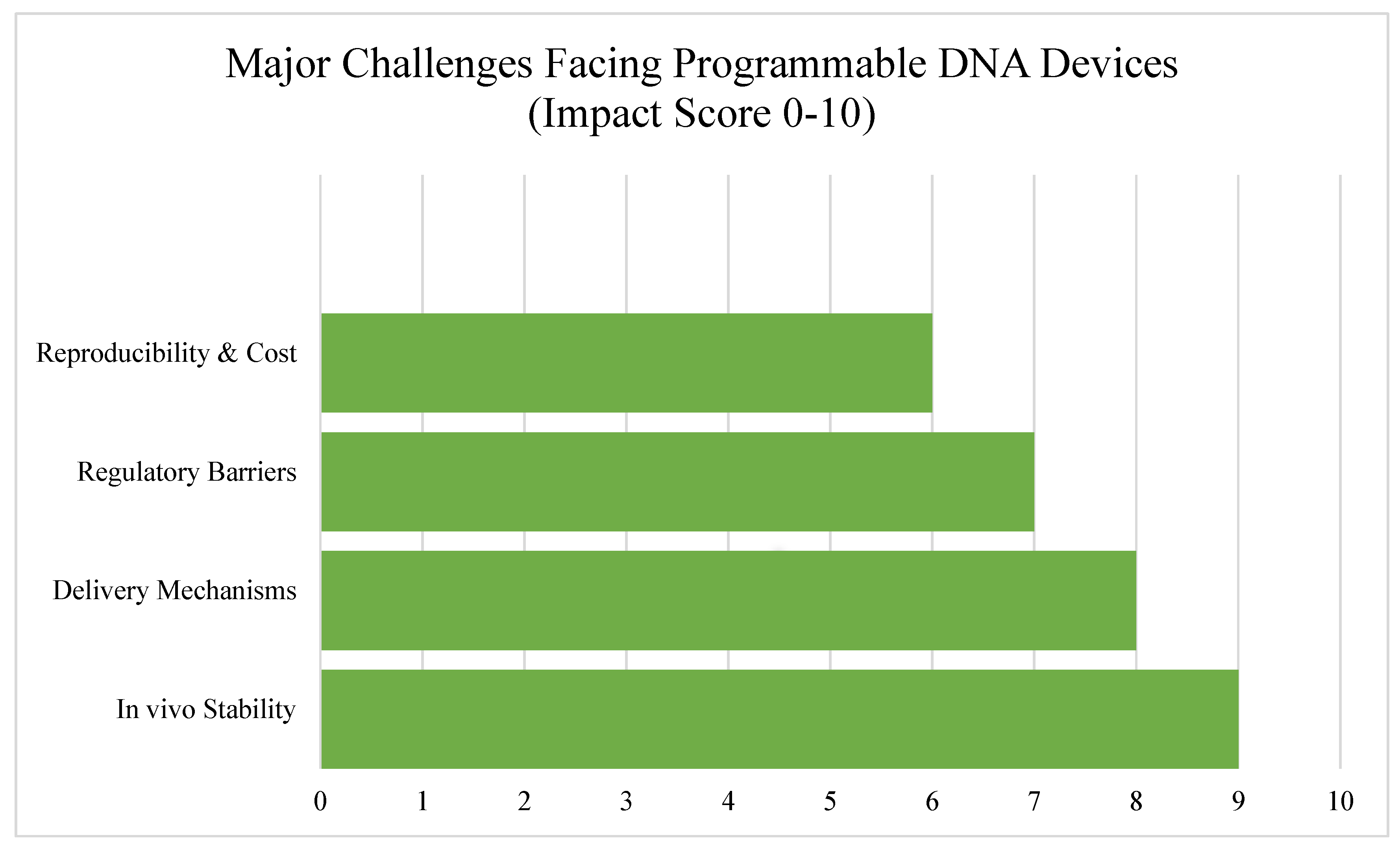

6. Challenges and Limitations

While programmable DNA devices hold enormous promise across agriculture, healthcare, and environmental science, several significant challenges still stand in the way of their widespread adoption. These issues span biological, technical, regulatory, and practical domains—each of which needs to be addressed to move these tools from proof-of-concept studies to real-world impact.

6.1. Stability and Degradation in Complex Environments

One of the biggest hurdles facing DNA-based systems is their stability outside controlled laboratory conditions. DNA molecules are inherently fragile and can be degraded by enzymes (like nucleases), temperature fluctuations, UV radiation, or contaminants in soil, water, and bodily fluids [

35].

In agricultural fields or environmental settings, where conditions are variable and often harsh, maintaining the functionality of DNA sensors over time is especially difficult. Researchers are exploring solutions such as chemical modifications, protective coatings, and encapsulation in nanoparticles to improve resilience, but these approaches are still under active development [

36].

6.2. Delivery Mechanisms in Plants and Humans

Getting DNA devices to the right place in a living system—whether it's a human tissue, a plant root, or a microbial colony—is another complex challenge. In medical applications, delivery often requires safe and efficient vectors that can enter cells without triggering immune responses or toxicity. Traditional methods like viral vectors and lipid nanoparticles have shown some success, but they carry risks and limitations [

37]. In plants, delivering synthetic DNA circuits to specific tissues—such as roots for nutrient sensing or leaves for pathogen detection—remains a technical bottleneck. Conventional transformation methods (e.g., Agrobacterium-mediated delivery) are not always effective or scalable for field use [

38].

New methods such as sprayable gene circuits, nanocarriers, or transient expression systems are emerging, but more work is needed to improve delivery precision, efficiency, and biosafety.

6.3. Regulatory and Safety Concerns

Because many DNA devices involve genetically modified organisms (GMOs) or synthetic biology, they are subject to strict regulatory scrutiny. This is particularly true for devices used in food systems, healthcare, or open environments. Public acceptance is another challenge. Concerns around gene editing, biosafety, and unintended ecological effects often lead to hesitancy in both policymakers and the public—even when the technology poses minimal risk [

39].

Developing transparent, standardized safety protocols and robust bio-containment strategies (such as kill switches or gene flow barriers) will be essential for building trust and gaining regulatory approval for these advanced biosensing systems.

6.4. Cost, Reproducibility, and Field Deployment

Finally, while many programmable DNA tools are relatively low-cost at the lab scale, scaling them up for widespread deployment remains a challenge. Issues such as batch-to-batch variability, sensitivity to production conditions, and the need for cold-chain storage in some cases can hinder commercial viability, see

Table 3. Deploying these technologies in rural clinics, farms, or conservation zones often requires rugged, self-powered, and easy-to-use systems—something that’s not always easy to achieve with current designs [

40].

To make programmable DNA devices practical, researchers must focus on improving manufacturing consistency, simplifying user interfaces, and ensuring that devices can function without the need for high-end lab infrastructure, see

Figure 7.

In summary, while the field of programmable DNA devices is advancing rapidly, real-world implementation still faces a number of obstacles. Solving these challenges will require close collaboration between synthetic biologists, engineers, regulatory bodies, and end-users—and a sustained commitment to turning brilliant ideas into robust, deployable technologies.

7. Future Directions

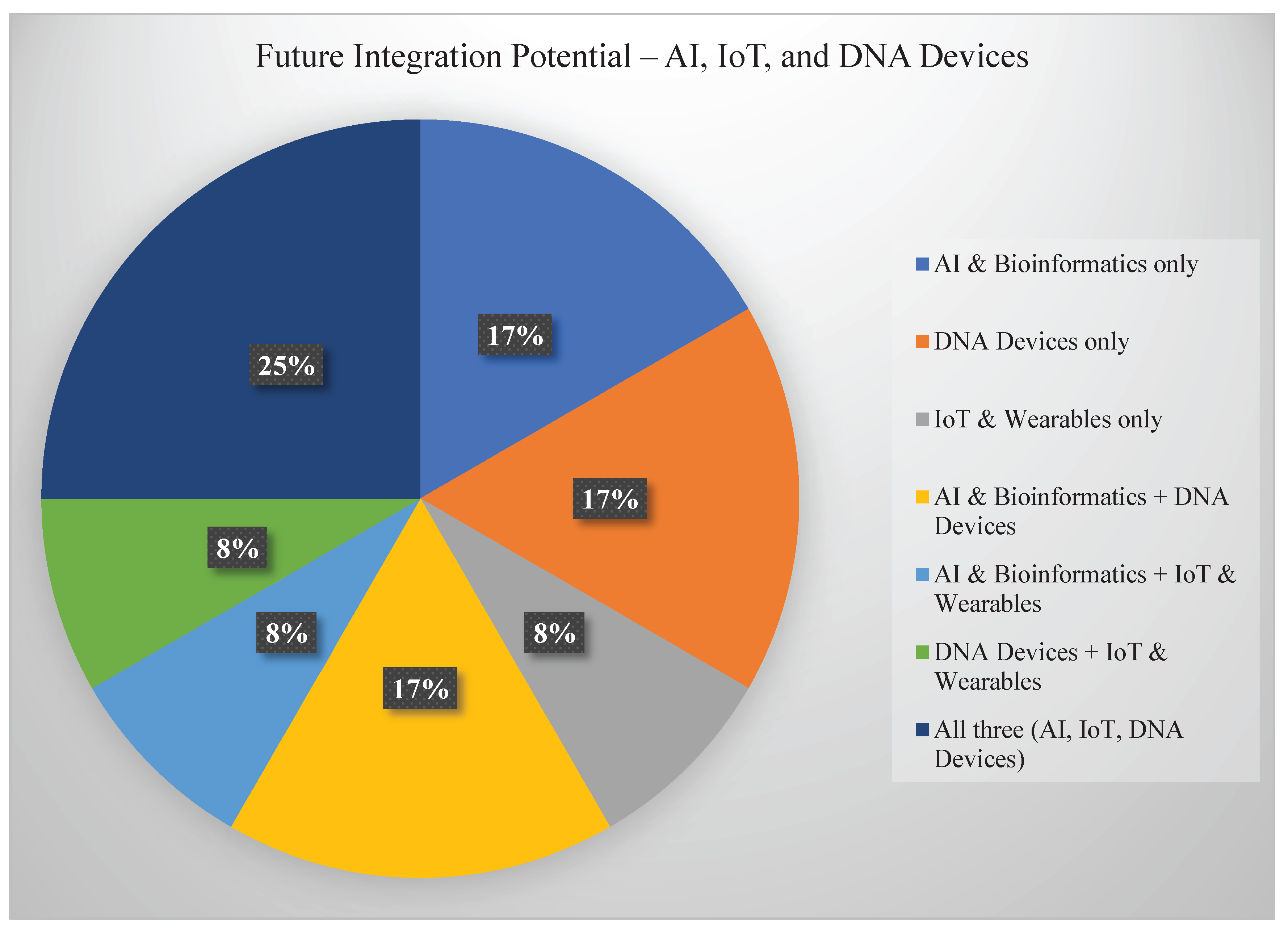

The potential of programmable DNA devices is only beginning to unfold. As technology advances and disciplines continue to converge, these molecular tools are poised to become even more intelligent, connected, and impactful. Looking ahead, several exciting directions are emerging that could redefine how we use DNA-based biosensors in science, healthcare, and society.

7.1. Integration with AI and the Internet of Things (IoT)

One of the most promising paths forward is combining programmable DNA devices with artificial intelligence (AI) and Internet of Things (IoT) networks. In this vision, DNA sensors deployed in remote fields, clinics, or natural habitats could transmit real-time data wirelessly to cloud platforms, where AI algorithms analyze trends, predict anomalies, and trigger automated responses [

41], see

Figure 8.

For example, a network of DNA biosensors in an agricultural field could detect early signs of fungal infection or soil imbalance and alert farmers through mobile apps. Similarly, wearable DNA sensors could monitor a patient's health and adjust treatment based on continuous feedback—all without human intervention. This kind of integration could enable responsive, decentralized monitoring systems that work smarter the more data they collect.

7.2. Multiplexed, Self-Learning Sensing Systems

Another exciting area of growth is in multiplexed sensing, where a single DNA device can detect multiple targets at once—from different pathogens and pollutants to multiple biomarkers in a single drop of blood or soil sample. Future systems may go a step further by incorporating machine learning components that allow DNA circuits to "learn" from repeated exposures, adapt to noisy environments, and improve accuracy over time [

42]. This concept is still largely theoretical, but it brings synthetic biology into the realm of adaptive, intelligent sensing—devices that evolve and optimize like biological systems.

7.3. Cross-Sector Convergence: One Health Approach

We’re also entering an era where boundaries between sectors—health, agriculture, and environment—are becoming increasingly blurred. The “One Health” approach, which recognizes that human, animal, and environmental health are deeply interconnected, provides a perfect framework for applying programmable DNA devices across domains [

43]. Imagine a single sensing platform that monitors zoonotic disease risks in wildlife, tracks antibiotic resistance in farm runoff, and screens for emerging pathogens in human populations. Such cross-sector integration could dramatically improve disease surveillance, environmental management, and food safety. Programmable DNA technologies are uniquely suited for this convergence because of their adaptability, portability, and ability to function in diverse biological contexts.

7.4. Biocompatible DNA Computing and Wearables

Finally, as DNA-based computation becomes more sophisticated, we may soon see wearable biosensors powered by DNA logic. These devices would operate without batteries or complex electronics, instead using molecular signals to compute simple tasks and provide readouts on things like hydration levels, nutrient deficiencies, or immune activity [

44]. Biocompatibility will be key here—future sensors must function safely in or on the body, without triggering immune responses or degrading too quickly. Advances in DNA nanomaterials, protective scaffolding, and low-cost manufacturing are making this vision more realistic than ever.

In all these future directions, one theme stands out: programmable DNA devices are becoming more integrated, intelligent, and personalized. Whether used to manage crops, monitor ecosystems, or track human health, these molecular systems offer a glimpse into a future where biology itself is a programmable platform—and sensing the world becomes as seamless as breathing.

8. Conclusions

Programmable DNA devices are redefining what it means to sense and interact with the biological world. With their unique ability to combine molecular precision, biological compatibility, and synthetic programmability, these tools offer powerful new ways to monitor, diagnose, and respond to challenges across healthcare, agriculture, and the environment. What sets them apart is not just their sensitivity or customizability, but their potential to operate autonomously, in real-time, and often directly within living systems. From detecting pathogens in plants and pollutants in soil, to delivering therapies in the human body or decoding biodiversity through eDNA, DNA-based devices are quickly transitioning from experimental platforms to real-world solutions.

However, realizing their full potential will require more than just technological advancement. It demands cross-disciplinary collaboration—between molecular biologists, engineers, environmental scientists, clinicians, and regulatory experts. We also need open dialogue with policymakers and the public to ensure these tools are developed and deployed responsibly. As this review has highlighted, programmable DNA devices are not a distant vision—they are already taking shape across multiple fields. By continuing to innovate, integrate, and scale these systems, we have the opportunity to build a future where biology itself becomes a programmable interface—capable of sensing, computing, and acting for the benefit of both people and the planet.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest related to this study. No competing financial interests or personal relationships could have influenced the content of this research review

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the support and resources provided by Prince Sattam Bin Abdulaziz University, particularly the Common First Year and Basic Science Department. Appreciation is extended to colleagues and peers whose insights and feedback enriched the scope of this review. The author also thanks the global scientific community whose innovative research in synthetic biology, nanotechnology, and environmental DNA provided the foundation for this work. Special recognition is given to the open-access platforms and databases that facilitated comprehensive literature retrieval essential for the development of this article.

AI Declaration

No artificial intelligence (AI) tools or automated writing assistants were used in the research, drafting, or editing of this manuscript. The content, including the literature review, analysis, and writing, was entirely produced by the authors. All conclusions and interpretations are based on human expertise, critical evaluation of the literature, and independent scholarly work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As this is a review article, no new human or animal data were collected, and thus, ethical approval was not required.

Data Availability Statement

No new datasets were generated or analyzed during this study. All data supporting this review are derived from previously published sources, which have been appropriately cited.

References

- McKeague, M., & DeRosa, M. C. (2012). Challenges and opportunities for small molecule aptamer development. Journal of Nucleic Acids, 2012, 748913. [CrossRef]

- Seelig, G., Soloveichik, D., Zhang, D. Y., & Winfree, E. (2006). Enzyme-free nucleic acid logic circuits. Science, 314(5805), 1585–1588. [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, J. N., Steenberg, C. D., Bois, J. S., Wolfe, B. R., Pierce, M. B., Khan, A. R., Dirks, R. M., & Pierce, N. A. (2011). NUPACK: Analysis and design of nucleic acid systems. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 32(1), 170–173. [CrossRef]

- Yin, P., Choi, H. M. T., Calvert, C. R., & Pierce, N. A. (2008). Programming biomolecular self-assembly pathways. Nature, 451(7176), 318–322. [CrossRef]

- Rothemund, P. W. K. (2006). Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature, 440(7082), 297–302. [CrossRef]

- Elowitz, M. B., & Leibler, S. (2000). A synthetic oscillatory network of transcriptional regulators. Nature, 403(6767), 335–338. [CrossRef]

- Pardee, K., Green, A. A., Takahashi, M. K., Braff, D., Lambert, G., Lee, J. W., Ferrante, T., Ma, D., Donghia, N., Fan, M., Daringer, N. M., Bosch, I., Dudley, D. M., O'Connor, D. H., Gehrke, L., & Collins, J. J. (2016). Rapid, low-cost detection of Zika virus using programmable biomolecular components. Cell, 165(5), 1255–1266. [CrossRef]

- Deiner, K., Bik, H. M., Mächler, E., Seymour, M., Lacoursière-Roussel, A., Altermatt, F., Creer, S., Bista, I., Lodge, D. M., de Vere, N., Pfrender, M. E., & Bernatchez, L. (2017). Environmental DNA metabarcoding: Transforming how we survey animal and plant communities. Molecular Ecology, 26(21), 5872–5895. [CrossRef]

- Odah, M.A.A. From the Double Helix to Precision Genomics: A Comprehensive Review of DNA and Its Transformative Role in Biomedical Sciences. African Research Journal of Biosciences 2024, 1, 72–88. [CrossRef]

- Song, K. M., Lee, S., & Ban, C. (2012). Aptamers and their biological applications. Sensors, 12(1), 612–631. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., Campbell, A. S., de Ávila, B. E.-F., & Wang, J. (2019). Wearable biosensors for healthcare monitoring. Nature Biotechnology, 37(4), 389–406. [CrossRef]

- Gootenberg, J. S., Abudayyeh, O. O., Kellner, M. J., Joung, J., Collins, J. J., & Zhang, F. (2018). Multiplexed and portable nucleic acid detection platform with Cas13, Cas12a, and Csm6. Science, 360(6387), 439–444. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., & Liu, J. (2007). Smart nanomaterials inspired by biology: Dynamic assembly of error-free nanomaterials in response to multiple stimuli. Accounts of Chemical Research, 40(5), 315–323. [CrossRef]

- Chen, A., & Yang, S. (2015). Replacing antibodies with aptamers in lateral flow immunoassay. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 71, 230–242. [CrossRef]

- Schaumberg, K. A., Antunes, M. S., Kassaw, T. K., Xu, W., Zalewski, C. S., & Medford, J. I. (2016). Quantitative characterization of genetic parts and circuits for plant synthetic biology. Nature Methods, 13(1), 94–100. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., & Stewart, C. N. (2015). Plant synthetic biology. Trends in Plant Science, 20(5), 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Fozouni, P., Son, S., de León Derby, M., Knott, G. J., Gray, C. N., D'Ambrosio, M. V., & Ott, M. (2021). Amplification-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 with CRISPR-Cas13a and mobile phone microscopy. Cell, 184(2), 323–333.e9. [CrossRef]

- Odah, M.A.A. Beyond the Double Helix: Unraveling the Intricacies of DNA and RNA Networks. African Research Journal of Biosciences 2024, 1, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Slomovic, S., Pardee, K., & Collins, J. J. (2015). Synthetic biology devices for in vitro and in vivo diagnostics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(47), 14429–14435. [CrossRef]

- Din, M. O., Danino, T., Prindle, A., Skalak, M., Selimkhanov, J., Allen, K., & Hasty, J. (2016). Synchronized cycles of bacterial lysis for in vivo delivery. Nature, 536(7614), 81–85. [CrossRef]

- Ma, D., Shen, L., Wu, K., Diehnelt, C. W., & Green, A. A. (2018). Cell-free synthetic biology: Engineering in an open world. Synthetic and Systems Biotechnology, 3(2), 90–99. [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H., Oura, A., Kashiwagi, A., & Saito, H. (2021). Real-time environmental monitoring with portable CRISPR-based biosensing. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 192, 113486. [CrossRef]

- Kotula, J. W., Kerns, S. J., Shaket, L. A., Siraj, L., Collins, J. J., Way, J. C., & Silver, P. A. (2014). Programmable bacteria detect and record an environmental signal in the mammalian gut. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(13), 4838–4843. [CrossRef]

- Odah, M. A. A. (2024). Exploring the role of DNA methylation in regulating gene expression and adaptation in plants: A case study on the impact of environmental stress on gene regulation. Preprints. https://www.preprints.org/manuscript/202403.0155/v2.

- Odah, M. (2024). Deciphering Epigenetic Mechanisms: The Role of DNA Methylation in Driving Phenotypic Diversity and Evolutionary Adaptation in Chickpea (Cicer arietinum). Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Karkaria, B. D., Fedorec, A. J. H., & Barnes, C. P. (2021). Automated design of synthetic microbial ecosystems. Nature Communications, 12(1), 672. [CrossRef]

- Rusk, N. (2015). DNA nanotechnology goes live. Nature Methods, 12(1), 25. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., Chen, F., Li, Q., Wang, L., & Fan, C. (2015). Isothermal amplification of nucleic acids. Chemical Reviews, 115(22), 12491–12545. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X., Jha, R. K., Duncan, B., Ko, D. H., Liu, D., & Rotello, V. M. (2012). Nanotechnology approaches for delivering DNA and RNA in mammalian systems. Biotechnology Advances, 30(4), 811–821. [CrossRef]

- Odah, M. (2025). Ultra-Short DNA Satellites as Environmental Sensing Elements in Soil Microbiomes: A Frontier Review. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Kuzma, J. (2016). Regulating gene-edited crops. Nature Biotechnology, 34(5), 475–477. [CrossRef]

- Pardee, K., Slomovic, S., Nguyen, P. Q., Lee, J. W., Donghia, N., Burrill, D., & Collins, J. J. (2016). Portable, on-demand biomolecular manufacturing. Cell, 167(1), 248–259.e12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wu, D., Wu, G., & Wu, J. (2021). Smart biosensors for real-time biomarker detection and patient monitoring. Biosensors and Bioelectronics, 176, 112924. [CrossRef]

- Odah, M.A.A. Exploring the Role of Circulating Cell-Free DNA in Disease Diagnosis and Therapy. African Research Journal of Medical Sciences 2024, 1, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Destoumieux-Garzón, D., Mavingui, P., Boetsch, G., Boissier, J., Darriet, F., Duboz, P., & Voituron, Y. (2018). The One Health concept: 10 years old and a long road ahead. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5, 14. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., Ghaffari, R., Baker, L. B., & Rogers, J. A. (2018). Skin-interfaced systems for sweat collection and analytics. Science Advances, 4(2), eaar3921. [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R., Wang, R., & Seelig, G. (2018). A molecular multi-gate circuit for autonomous analysis of orthogonal inputs. Nature Nanotechnology, 13(8), 657–664. [CrossRef]

- Destoumieux-Garzón, D., Mavingui, P., Boetsch, G., Boissier, J., Darriet, F., Duboz, P., & Voituron, Y. (2018). The One Health concept: 10 years old and a long road ahead. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5, 14. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J., Ghaffari, R., Baker, L. B., & Rogers, J. A. (2018). Skin-interfaced systems for sweat collection and analytics. Science Advances, 4(2), eaar3921. [CrossRef]

- Rothemund, P. W. K. (2006). Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature, 440(7082), 297–302. [CrossRef]

- Odah, M. (2025). Artificial Intelligence Meets Drug Discovery: A Systematic Review on AI-Powered Target Identification and Molecular Design. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, A. A. K., & Voigt, C. A. (2014). Multi-input CRISPR/Cas genetic circuits that interface host regulatory networks. Molecular Systems Biology, 10(11), 763. [CrossRef]

- Brophy, J. A. N., & Voigt, C. A. (2014). Principles of genetic circuit design. Nature Methods, 11(5), 508–520. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D. Y., & Seelig, G. (2011). Dynamic DNA nanotechnology using strand-displacement reactions. Nature Chemistry, 3(2), 103–113. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).