Submitted:

21 May 2025

Posted:

22 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

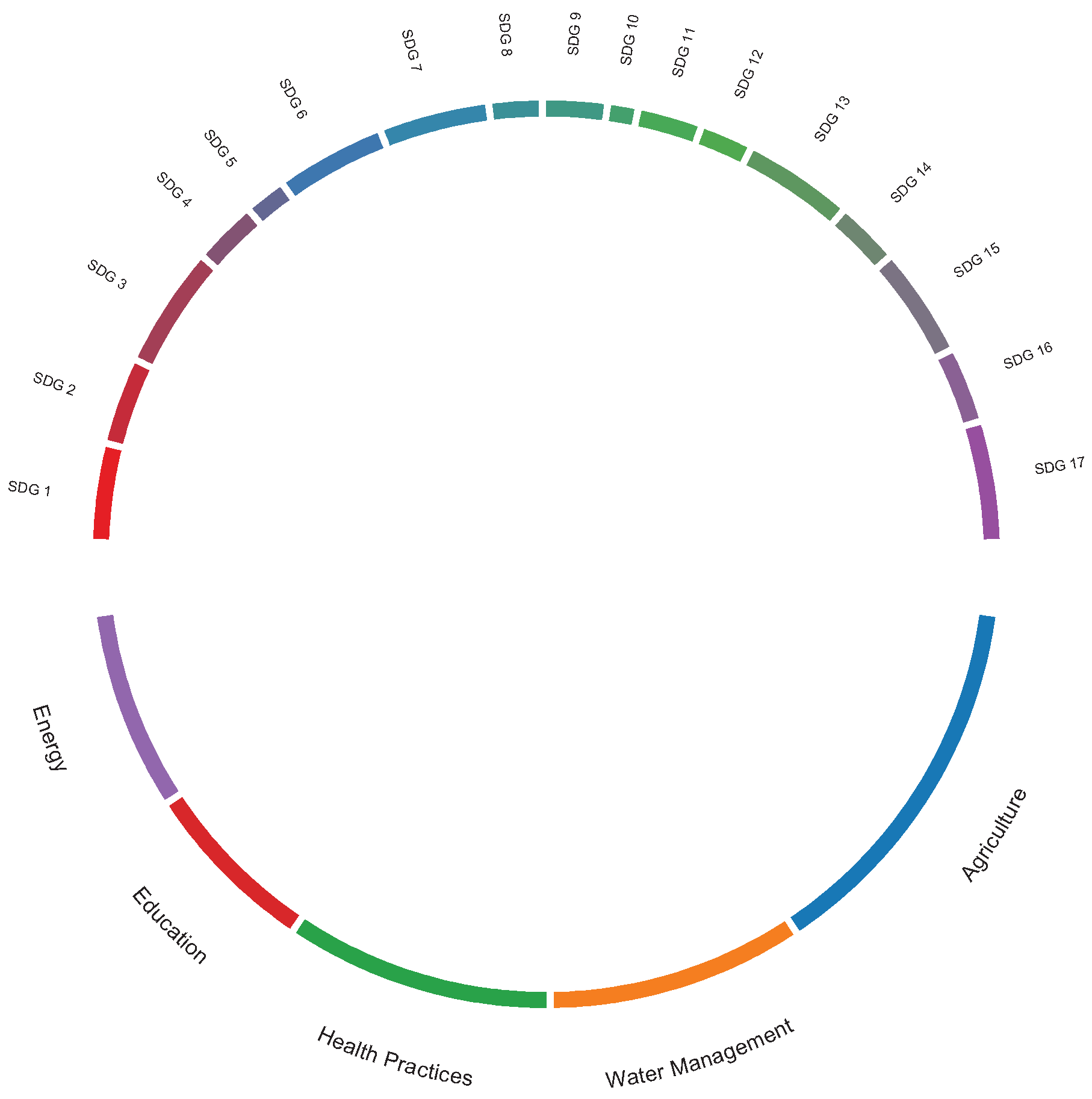

Linking Traditional Ecological Knowledge to Sustainable Development Goals

Conclusion

References

- Abdurahman, A. (2019). The Gada system and the Oromo’s (Ethiopia) culture of peace. Skhid, 0(2(160)), 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. (1995). Dismantling the divide between indigenous and scientific knowledge. Development and Change, 26(3), 413-439. [CrossRef]

- Ajitha, S., Reshma, K. J., & Huxley, S. (2025). Indigenous Knowledge and Sustainable Development: Bridging Traditional Practices with Modern Climate Solutions. In Community Climate Justice and Sustainable Development (pp. 147-180). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Akther, S. (2025). Bridging the Gaps: Climate Justice and SDGs Implementation in Indigenous Communities. In Community Climate Justice and Sustainable Development (pp. 369-390). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Aluko, Y. A. (2018). Women’s use of indigenous knowledge for environmental security and sustainable development in Southwest Nigeria. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 9(3), 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Bang, H. N. (2024). Sustainable development goals, disaster risk management, and indigenous knowledge: a critical assessment of the interlinkages. Sustainable Earth Reviews, 7(1), 29. [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. (2017). Sacred Ecology. Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Bhuker, A., Mor, V., Raj, P., & Jakhar, S. (2022). Potential Use of Medicinal Plant Gokhru: A Review. Journal of Ayurvedic and Herbal Medicine, 8(2), 101-106. [CrossRef]

- Brant, J., Peterson, S. S., & Friedrich, N. (2023). Partnership Research with Indigenous Communities: Fostering Community Engagement and Relational Accountability. Brock Education Journal, 32(1), 99–118. [CrossRef]

- Chanza, N., & Musakwa, W. (2022). Revitalizing indigenous ways of maintaining food security in a changing climate: review of the evidence base from Africa. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 14(3), 252-271. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P., Evans, L., & Govan, H. (2015). Community-based, co-management for governing small-scale fisheries of the Pacific: A Solomon Islands’ case study. In Interactive governance for small-scale fisheries: Global reflections (pp. 39-59). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Cronkleton, P., Bray, D. B., & Medina, G. (2011). Community forest management and the emergence of multi-scale governance institutions: Lessons for REDD+ development from Mexico, Brazil and Bolivia. Forests, 2(2), 451-473. [CrossRef]

- Das, A., Gujre, N., Devi, R. J., & Mitra, S. (2021). A review on traditional ecological knowledge and its role in natural resources management: North East India, a cultural paradise. Environmental Management, 72 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Debisa, N. G. (2022). Building peace by peaceful approach: The role of Oromo Gadaa system in peace-building. Cogent Social Sciences, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, P. M. (2020). Fire Country: How Indigenous Fire Management Could Help Save Australia. International Journal of Wildland Fire, 29(11), 1052–1052. [CrossRef]

- Fickel, L., Abbiss, J., Brown, L., & Astall, C. (2018). The importance of community knowledge in learning to teach: Foregrounding Māori cultural knowledge to support preservice teachers’ development of culturally responsive practice. Peabody Journal of Education, 93(3), 285-294. [CrossRef]

- Foggin, J. M. (2021). We still need the wisdom of Ubuntu for successful nature conservation. Ambio, 50(3), 723-725. [CrossRef]

- Georgeson, L., & Maslin, M. (2018). Putting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals into practice: A review of implementation, monitoring, and finance. Geo: Geography and Environment, 5(1), e00049. [CrossRef]

- Harcourt, N., Awatere, S., Hyslop, J., Taura, Y., Wilcox, M., Taylor, L., Rau, J., & Timoti, P. (2022). Kia manawaroa kia puawai: Enduring Māori livelihoods. Sustainability Science, 17(2), 391-402. [CrossRef]

- Harisha, R. P., Padmavathy, S., & Nagaraja, B. C. (2016). Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and its importance in south India: perspective from local communities. Applied Ecology and Environmental Research, 14(1), 311-326. [CrossRef]

- Heredia-R, M., Torres, B., Cayambe, J., Ramos, N., Luna, M., & Diaz-Ambrona, C. G. (2020). Sustainability assessment of smallholder agroforestry indigenous farming in the Amazon: A case study of Ecuadorian Kichwas. Agronomy, 10(12), 1973. [CrossRef]

- Huntington, H. P. (2000). Using Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Science: Methods and Applications. Ecological Applications, 10(5), 1270–1270. [CrossRef]

- Huntington, H. P., Carey, M., Apok, C., Forbes, B. C., Fox, S., Holm, L. K., Ivanova, A., Jaypoody, J., Noongwook, G., & Stammler, F. (2019). Climate change in context: putting people first in the Arctic. Regional Environmental Change, 19(4), 1217–1223. [CrossRef]

- Isaac, G., Finn, S., Joe, J. R., Hoover, E., Gone, J. P., Lefthand-Begay, C., & Hill, S. (2018). Native American perspectives on health and traditional ecological knowledge. Environmental Health Perspectives, 126(12), 125002. [CrossRef]

- Johannes, R. E. (2002). The renaissance of community-based marine resource management in Oceania. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 33(1), 317-340. [CrossRef]

- Joji, V. S., & Jacob, R. S. (2023). Traditional Rainwater Harvesting Structures. Springer. [CrossRef]

- King, D. N., Goff, J., & Skipper, A. (2007). Māori environmental knowledge and natural hazards in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 37(2), 59-73. [CrossRef]

- Kong, X., & Jia, F. (2023). Intergenerational transmission of environmental knowledge and pro-environmental behavior: A dyadic relationship. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 89, 102058. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A., Kumar, S., Komal, Ramchiary, N., & Singh, P. (2021). Role of traditional ethnobotanical knowledge and indigenous communities in achieving sustainable development goals. Sustainability, 13(6), 3062. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. (2024). Traditional and Modern Disaster Resistant House Construction Techniques. Journal of Progress in Engineering and Physical Science, 3(1), 13-22.

- Leal Filho, W., Tripathi, S. K., Andrade Guerra, J. B. S. O. D., Giné-Garriga, R., Orlovic Lovren, V., & Willats, J. (2019). Using the sustainable development goals towards a better understanding of sustainability challenges. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology, 26(2), 179-190. [CrossRef]

- Lemi, T. (2019). The role of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) for climate change adaptation. International Journal of Environmental Sciences & Natural Resources, 18(1), 28-31.

- Ludwig, D., & Macnaghten, P. (2019). Traditional ecological knowledge in innovation governance: a framework for responsible and just innovation. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 7(1), 26–44. [CrossRef]

- Lüttringhaus, S., Pradel, W., Suarez, V., Manrique-Carpintero, N. C., Anglin, N. L., Ellis, D., ... & Gómez, R. (2021). Dynamic guardianship of potato landraces by Andean communities and the genebank of the International Potato Center. CABI Agriculture and Bioscience, 2, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Mathur, A., Bagul, A., & Rajhans, K. (2024). Indigenous Practices for Achieving Sustainable Construction. Current World Environment, 19(2), 716.

- McKemey, M., Ens, E., Rangers, Y. M., Costello, O., & Reid, N. (2020). Indigenous Knowledge and Seasonal Calendar Inform Adaptive Savanna Burning in Northern Australia. Sustainability, 12(3), 995–995. [CrossRef]

- Mtshali, M. N. G., Raniga, T., & Khan, S. (2014). Indigenous knowledge systems, poverty alleviation and sustainability of community-based projects in the Inanda region in Durban, South Africa. Studies of Tribes and Tribals, 12(2), 187-199.

- Nadasdy, P. (1999). The politics of TEK: Power and the “integration” of knowledge. Arctic Anthropology, 1-18.

- Nepal, T. K. (2023a). The Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Environmental Stewardship: Beyond Poverty and Necessity. Journal of Resources, Energy and Development, 20(2), 86-96. [CrossRef]

- Nepal, T. K. (2023b). Traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) and its importance in the Himalayan Kingdom of Bhutan. In Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Resource Management in Asia (pp. 317-332). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Nepal, T. K. (2024). Aligning Gross National Happiness, Sustainable Development Goals, and Traditional Ecological Knowledge: A Path to Holistic Well-being. Indonesian Journal of Social and Environmental Issues (IJSEI), 5(1), 42-49. [CrossRef]

- Ngamprapasom, P. (2010). Renewable energy technology in Buddhist monasteries (Doctoral dissertation, Murdoch University).

- Nikolakis, W., & Nelson, H. W. (2018). Trust, institutions, and indigenous self-governance: An exploratory study. Governance, 32(2), 331–347. [CrossRef]

- Pauletto, D., Guerreiro Martorano, L., de Sousa Lopes, L. S., Pinheiro de Matos Bentes, M., Vieira, T. A., Gomes de Sousa Oliveira, T., Santos de Sousa, V., Fernandes da Silva, Á., da Silva Ferreira de Lima, P., Santos Tribuzy, A., & Pinto Guimarães, I. V. (2023). Plant Composition and Species Use in Agroforestry Homegardens in the Eastern Amazon, Brazil. Sustainability, 15(14), 11269. [CrossRef]

- Pearce, T., Ford, J., Willox, A. C., & Smit, B. (2015). Inuit traditional ecological knowledge (TEK), subsistence hunting and adaptation to climate change in the Canadian Arctic. Arctic, 233-245. [CrossRef]

- Phungpracha, E., Kansuntisukmongkon, K., & Panya, O. (2016). Traditional ecological knowledge in Thailand: Mechanisms and contributions to food security. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 37(2), 82-87. [CrossRef]

- Popova, U. (2013). Conservation, Traditional Knowledge, and Indigenous Peoples. American Behavioral Scientist, 58(1), 197–214. [CrossRef]

- Quisumbing, A., Heckert, J., Faas, S., Ramani, G., Raghunathan, K., & Malapit, H. (2021). Women’s empowerment and gender equality in agricultural value chains: evidence from four countries in Asia and Africa. Food Security, 13, 1101-1124. [CrossRef]

- Rameka, L., & Stagg Peterson, S. (2021). Sustaining indigenous languages and cultures: Māori medium education in Aotearoa New Zealand and Aboriginal head Start in Canada. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 16(2), 307-323. [CrossRef]

- Rani, J., Gulia, V., Sangwan, A., Dhull, S. S., & Mandzhieva, S. (2025). Synergies of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Biodiversity Conservation: A Paradigm for Sustainable Food Security. In Ecologically Mediated Development: Promoting Biodiversity Conservation and Food Security (pp. 27-49). Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Sakakibara, C. (2016). People of the Whales: Climate Change and Cultural Resilience Among Iñupiat of Arctic Alaska. Geographical Review, 107(1), 159–184. [CrossRef]

- Sanabria, C., & Achury, R. (2022). Amazonian indigenous territories as reservoirs of biodiversity: The army ants of Santa Sofia (Amazonas—Colombia). Caldasia, 44(2), 345–355. [CrossRef]

- Sawant, V. (2025). Synergizing Artificial Intelligence and Traditional Ecological Knowledge for Water Resource Optimization. International Journal for Multidisciplinary Research, 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Saylor, C. R., Alsharif, K. A., & Torres, H. (2017). The importance of traditional ecological knowledge in agroecological systems in Peru. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management, 13(1), 150-161. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M. V. C., Ikpeng, Y. U., Kayabi, T., Sanches, R., Ono, K. Y., & Adams, C. (2021). Indigenous Knowledge and Forest Succession Management in the Brazilian Amazon: Contributions to Reforestation of Degraded Areas. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 4. [CrossRef]

- Sears, R. R., & Steward, A. M. (2011). Education, Ecology and Poverty Reduction. In Integrating Ecology and Poverty Reduction: The Application of Ecology in Development Solutions (pp. 17-37). New York, NY: Springer New York. [CrossRef]

- Shawoo, Z., & Thornton, T. F. (2019). The UN local communities and Indigenous peoples’ platform: A traditional ecological knowledge-based evaluation. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 10(3), e575. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M. K., Mahapatra, S., & Atreya, S. K. (2011). Solar passive features in vernacular architecture of North-East India. Solar Energy, 85(9). [CrossRef]

- Singh, P., Tabe, T., & Martin, T. (2022, January). The role of women in community resilience to climate change: A case study of an Indigenous Fijian community. In Women’s Studies International Forum (Vol. 90, p. 102550). Pergamon. [CrossRef]

- Sinthumule, N. I. (2023). Traditional ecological knowledge and its role in biodiversity conservation: a systematic review. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11, 1164900. [CrossRef]

- Stori, F. T., Peres, C. M., Turra, A., & Pressey, R. L. (2019). Traditional ecological knowledge supports ecosystem-based management in disturbed coastal marine social-ecological systems. Frontiers in Marine Science, 6, 571. [CrossRef]

- Swiderska, K., Reid, H., Song, Y., Li, J., Mutta, D., Ongugo, P., Pakia, M., Oros, R., & Barriga, S. (2011). The Role of Traditional Knowledge and Crop Varieties in Adaptation to Climate Change and Food Security in SW China, Bolivian Andes and coastal Kenya. International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), London, United Kingdom.

- Tang, R., & Gavin, M. C. (2010). Traditional ecological knowledge informing resource management: Saxoul conservation in inner Mongolia, China. Society and Natural Resources, 23(3), 193-206. [CrossRef]

- Tengö, M., Brondizio, E. S., Elmqvist, T., Malmer, P., & Spierenburg, M. (2014). Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: the multiple evidence base approach. Ambio, 43, 579-591. [CrossRef]

- Van Norren, D. E. (2020). The sustainable development goals viewed through gross national happiness, Ubuntu, and Buen Vivir. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 20(3), 431-458. [CrossRef]

- Walters, B. (2003). Indigenous Environmental Knowledge and Its Transformations: Critical Anthropological Perspectives. American Anthropologist, 105(2), 406.

- Wilson, E. (2019). What is benefit sharing? Respecting indigenous rights and addressing inequities in Arctic resource projects. Resources, 8(2), 74. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S. (2023). Traditional rain water harvesting systems in Rajasthan: water resources conservation and its sustainable management –a review. Sustainability, Agri, Food and Environmental Research, 11(X). [CrossRef]

- Yli-Pelkonen, V., & Kohl, J. (2005). The role of local ecological knowledge in sustainable urban planning: perspectives from Finland. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 1(1), 3-14. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).