1. Introduction

Tympanoplasty is a common surgical procedure in the ear, nose, and throat areas. The goal of successful tympanoplasty is to remove the existing pathology, to establish a sound-conducting mechanism in a well-ventilated, mucosa-lined middle ear cavity, and to sustain these successes over time [

1,

2,

3]. Graft success rates in tympanoplasty operations range from 65% to 90%. Numerous studies have looked into the factors that influence surgical outcome, such as the size and location of the perforation, infection, Eustachian tube function, smoking status, surgical technique, and local estrogen use [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

Most of the current understanding of tympanic membrane (TM) epithelial structure and its healing mechanisms is extrapolated from extensive research on cutaneous wound healing. However, emerging evidence indicates that TM wound healing differs significantly from that of the skin. Specifically, keratinocytes are the first cells to participate in sealing TM perforations, in contrast to skin wounds, where they are involved later in the healing process [

9].

The epidermal layer of the TM, due to its inherent migratory properties, is the initial layer responsible for closing the perforation. In contrast, repair of the fibrous layer occurs subsequently, and its regenerative response is influenced by the vascular distribution within the TM. A key element in TM healing is the centripetal migration of epithelial cells originating from a central proliferation zone, which plays a pivotal role in restoring membrane integrity [

10,

11,

12].

Estrogen has been shown to have a favorable influence on wound healing keratinocytes and the vascular network and fibrocytes in the connective tissue.

Although several earlier studies have investigated the effects of estrogen on wound healing, our literature search showed no prior research into the relationship between blood estrogen levels that fluctuate over the menstrual cycle and tympanoplasty outcomes in healthy women.

The goal of this study was to look at the impact of serum estrogen levels during the menstrual cycle on tympanoplasty surgery and hearing level results.

2. Materials and Methods

The goal of this prospective double-blind clinical experiment was to investigate the impact of blood estrogen levels on tympanoplasty success rate. The University of Health Sciences, Erzurum City Hospital’s ethical committee in Erzurum, Turkey, gave its approval. All data collection followed acceptable clinical standards and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written consent before the start of the study.

2.1. Patient Selection and Groups

The study comprised all patients with TM perforation who were referred to the Atatürk University Otolaryngology Clinic. All participants provided informed consent. After obtaining thorough medical histories and performing physical examinations, with special care devoted to relevant problems, such as sinonasal disorders and craniofacial anomalies, otomicroscopic examination and audiometric testing were performed. Perforations were classed as either minor (<50% of the TM) or large (>50%). The study covered patients with minor central perforations.

The study involved 100 patients. All participants were asked about their menstrual status, which was defined as either 3–11 days after the commencement of menstruation (follicular phase) or 21–27 days after the onset of menstruation (luteal phase) [

13,

14]. Blood samples were taken and delivered to the testing facility, where estrogen levels were measured using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. All tympanoplasties were done by the same surgeon. Both the patients and the otolaryngologist were unaware of the blood estrogen level results.

2.2. Exclusion Criteria

To ensure that the list of case notes would be homogeneous, patients with acute TM perforation, marginal perforation, contralateral ear pathologies (e.g., perforation, retraction pocket, and myringosclerosis), active otorrhea during the preceding three months, evidence of polyp, granulation tissue, or other observations suggestive of cholesteatoma at otomicroscopic examination, a history of myringoplasty/tympanoplasty in each ear, cleft palate (patent or submucosal) or a history of cleft palate repair, obstructive pathologies of the nose or nasopharynx, history of smoking, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or immunocompromised conditions, those refusing consent to surgery or to enter the study, with menstrual irregularities, infertility, or polycystic ovarian disease were excluded from the study.

Two principal outcome measures were recorded to address the study aims. First, establish whether the TM was closed following tympanoplasty (defined as success) or not (defined as failure).

Second, we assessed the improvement in audiometric air conduction hearing after successful tympanoplasty. The preoperative and postoperative air conduction audiometric thresholds for each individual were determined using four frequencies (0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz), and the participants were classified according to the World Health Organization classification of normal hearing, mild hearing loss, and moderate hearing loss. Patients with hearing threshold levels of ≤25 dB were classified as having normal hearing, those with thresholds between 26 and 40 dB as having mild hearing loss, and those between 41 and 60 dB as having moderate hearing loss [

15].

All unsuccessful tympanoplasty instances were eliminated from this phase of the study. The average preoperative and postoperative air conduction audiometric thresholds at the four thresholds indicated above for all successful tympanoplasty in each category were calculated and compared.

A standard endoscopic transcanal tympanoplasty protocol was followed, and tragus perichondrium grafts were used in all instances. Every patient received type 1 tympanoplasty. The underlay approach was used for graft implantation. Following graft implantation, gel foam was used to support the middle ear and external auditory canal.

All patients were discharged the day after surgery. Follow-up sessions were scheduled for the seventh and 21st days postoperatively. Otomicroscopic tests were performed after 12 weeks to assess the graft’s condition. Hearing thresholds were also assessed using audiometric exams. A hearing threshold level of ≤25 dB was considered the criterion for audiological success.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The data was analyzed using the SPSS 20.0 program (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). To analyze the study’s sustainability, continuous variables were defined as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables were defined as frequency and percentage. As the data were normally distributed based on the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, parametric tests were applied for statistical analysis. For pairwise comparisons of continuous variables between two independent groups, the independent samples t test was used. The chi-square test was employed to evaluate associations between categorical variables.

The Pearson correlation test was used to assess the relationship between estrogen levels and gain. Using logistic regression analysis, indicators suggesting perforation closure were identified and given as 95% confidence intervals, odds ratios, and β coefficients. The factors suggesting increased success were identified using linear regression analysis. A p value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant throughout the study.

3. Results

The study originally included 100 patients. However, only 80 case notes from the 100 successful tympanoplasty included both preoperative and postoperative audiometry results. As a result, only the data from these 80 case notes were used to determine the audiological improvement after successful tympanoplasty due to TM perforation. Out of the 80 patients, 40 were in the follicular phase (age, 28.15 ± 6.84 yr; height, 160.93 ± 4.29 cm; weight, 61.46 ± 4.13 kg; and body mass index [BMI], 23.72 ± 1.11 kg/m

2), and 40 were in the luteal phase (age, 27.45 ± 6.83 yr; height, 158.90 ± 3.95 cm; weight, 61.55 ± 2.93 kg; and BMI, 24.40 ± 1.26 kg/m

2).

Table 1 shows hormone concentrations during both menstrual phases. Serum estrogen levels increased significantly from the follicular phase (33.83 ± 1.04 pg/mL) to the luteal phase (108.33 ± 0.54 pg/mL;

p < 0.001).

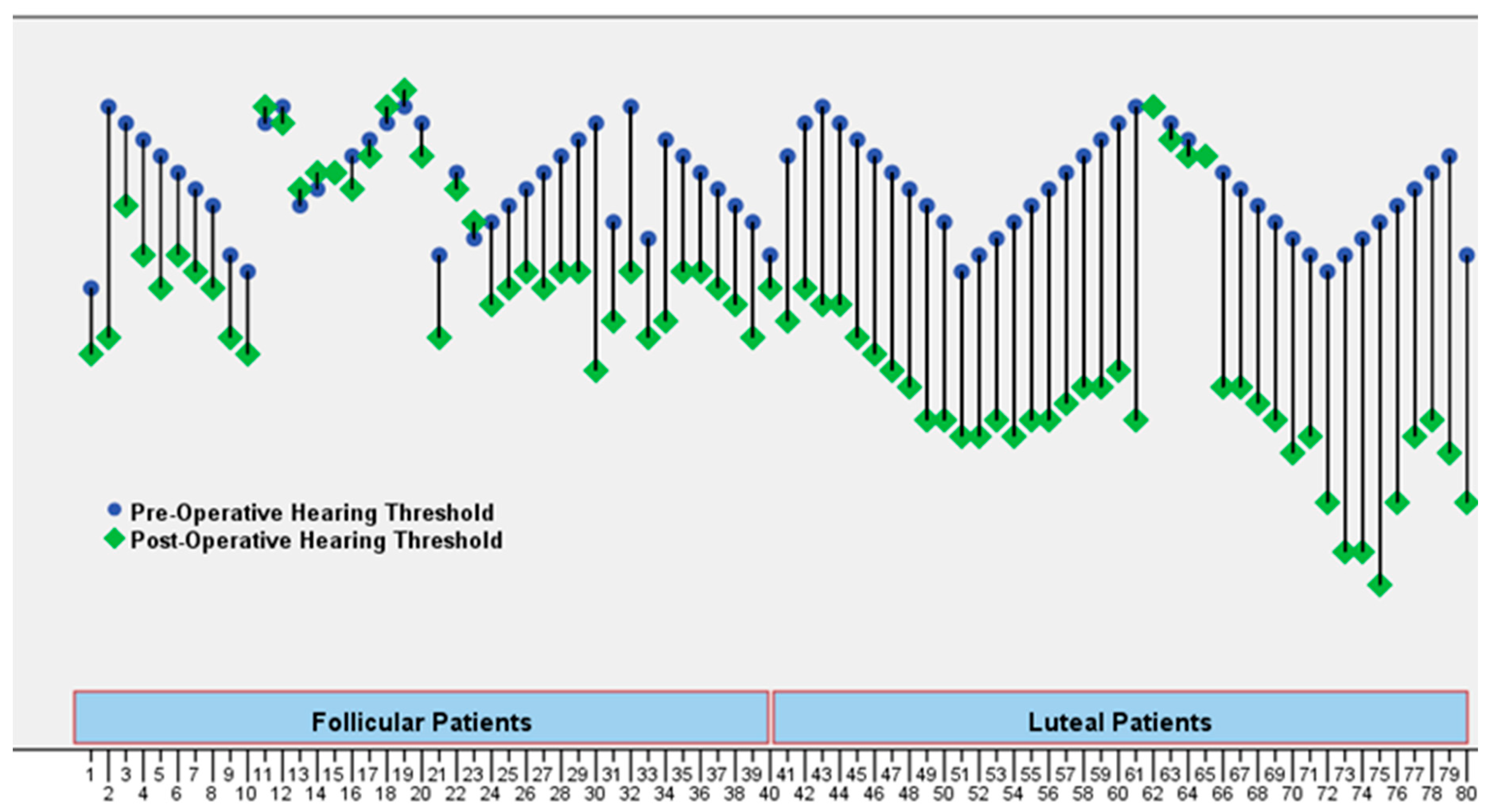

Two primary outcome measures were recorded to address the study’s objectives. First, we determined whether the TM was closed after tympanoplasty (designated as success) or not (considered as failure). Perforation closure was seen in 28 (70%) patients in the follicular phase and 36 (90%) in the luteal phase. The difference between the two was quite significant (

p = 0.025). After successfully closing all perforations, the mean air conduction decreased from 34.65 ± 3.05 to 29.95 ± 4.63 in the patients in the follicular phase and from 34.18 ± 2.30 to 21.83 ± 6.45 in the luteal phase group. Audiometric gains of 4.70 ± 3.92 and 12.35 ± 4.84 dB were determined. This was highly significant (

p < 0.001) as demonstrated in

Table 1 and preoperative and postoperative hearing threshold values of the patients (

Figure 1). Audiological success was achieved in the luteal group (

p < 0.001).

Looking at the parameters influencing perforation closure situation, the luteal group had a higher perforation closure rate than the follicular group (

p = 0.004), and when BMI decreased, the rate of perforation closure increased, as indicated in

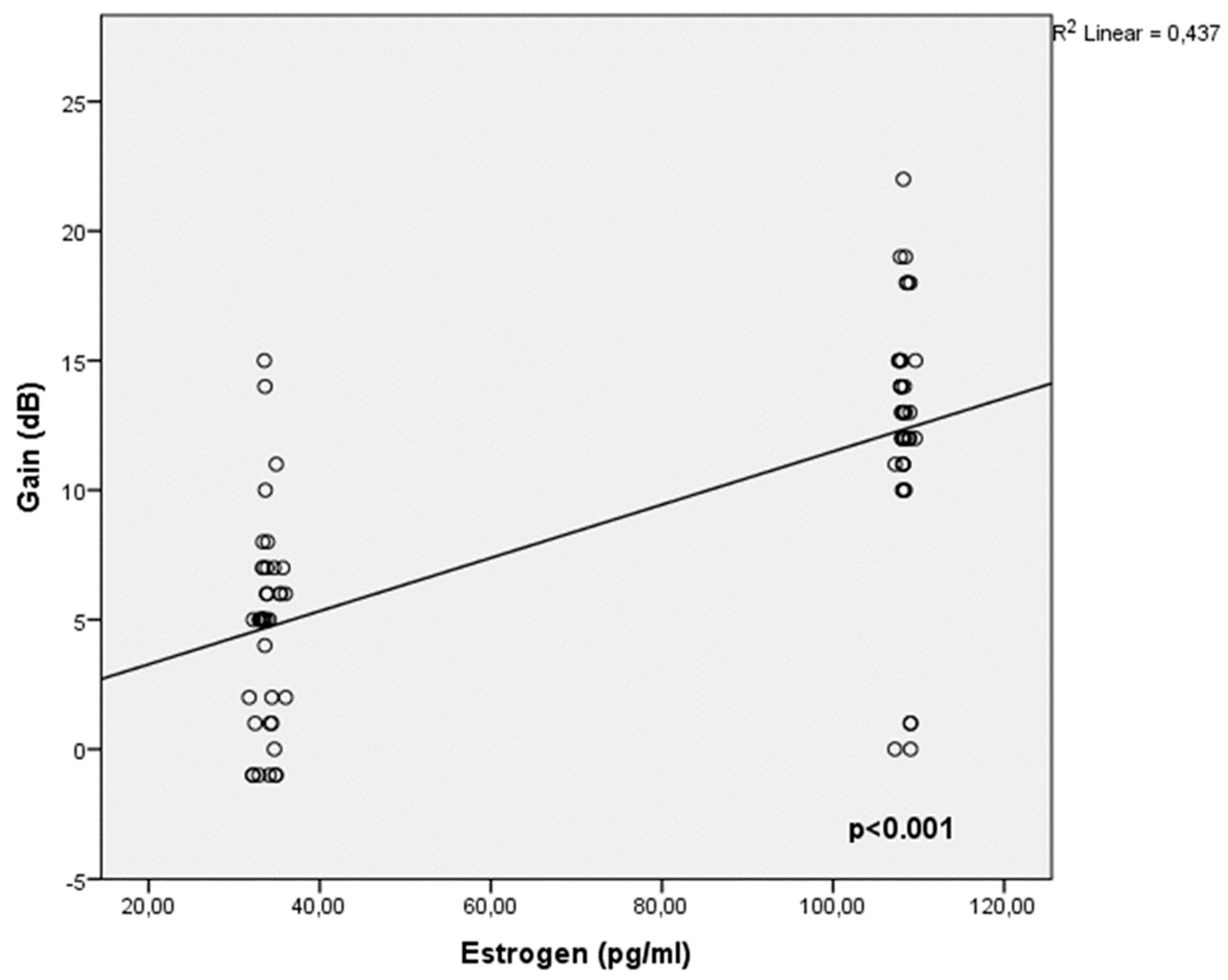

Table 2. In terms of factors influencing audiometric gain status, it has been shown that as estrogen levels rise and BMI falls, gain increases, as indicated in

Table 3 and (

Figure 2).

4. Discussion

In this study, both surgical results and hearing threshold levels were positively influenced by tympanoplasties performed during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, when healthy women’s blood estrogen levels are elevated.

In tympanoplasty surgeries, the perforation borders are abraded to cause acute trauma. A graft that covers the perforated borders from above or below is implanted to close the perforation in the TM with healing tissue.

Histopathologically, the TM perforation closure process is commonly divided into three phases: inflammatory, proliferative, and remodeling [

16].

The initial step of TM wound healing is the inflammatory phase, during which the squamous epithelium at the perforation margin becomes hyperplastic and procedures an abundance of keratin. During this time, an exudative reaction involving interstitial fluid, lymph, and blood has been observed to collect in the perforation margin. Researchers believe that during the inflammatory period, the layered epithelial cells at the perforation edge enlarge within 10 h, and that mitotic activity can be seen between 10 and 12 h after perforation. It has also been claimed that the increase in the number of cells in the perforation margin during the first 48 h is caused by proliferation rather than migration or by increased mitotic activity [

17,

18,

19].

The second stage is the proliferative stage, during which the squamous epithelium grows and migrates. This stage is characterized by increasing fibroblast activity and vascular proliferation [

20].

Following closure, healing progresses to the renovation stage. During this phase, the epithelium is three or four layers thick, then reduces to a single layer within 2 months. The fibrous layer remained thicker than typical at the second month. A macroscopic scar remains apparent for up to 6 months following perforation. The epithelium appeared normal, but the connective tissue layer was still thicker than normal. The TM finally takes its final form after being covered in two layers, rather than three [

16].

Perforations typically close between the fifth, seventh, and 32nd days in the laboratory setting, whereas point perforations close in less than 4 days [

21].

Studies on the effects of estrogen on wound healing in animal models have revealed that it has a mitogenic effect on keratinocytes and increases postinjury epithelialization rates. Exogenous systemic or topical estrogen treatment has been found to promote healing by stimulating matrix deposition and reducing inflammation [

22].

Furthermore, the preventive benefits of estrogen have been shown at the cellular level. It has been found to diminish age-dependent oxidative stress and apoptosis in human fibroblasts, guarding against H

2O

2 oxidative damage and allowing normal collagen synthesis while preserving cellular proliferation [

23,

24].

Topical 17β-estradiol or oral hormone replacement treatment can improve skin elasticity and hydration, wrinkle reduction collagen synthesis [

24]. Another study found that estrogen improved keratinocyte and fibroblast functions, increased matrix deposition, and supported anti-inflammatory macrophage activities, as well as lowering inflammation and wound protease levels by lowering proinflammatory cytokines.

The topical use of estrogen to old acute wounds reduces inflammation, neutrophil counts, and elastase production, promoting wound healing and collagen buildup after 7 days [

26].

Several investigations have indicated that the hormone estrogen regulates cellular migration, which is a critical phase in both cutaneous wound healing and TM repair [

27,

28].

Another study investigated the possible effect of patch coating covered with 1% estrogen on TM healing. These authors discovered that patients who received a paper patch coated with 1% estrogen ointment had a considerably higher percentage of perforation closure [

29]. The authors revealed substantial good findings, both in terms of TM healing and hearing levels. This study looked at the favorable benefits of topical and systemic estrogen on TM healing.

Estrogen levels vary throughout the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. While estrogen concentrations are low throughout the follicular phase, they gradually increase as the phase advances. Estrogen levels were significantly higher during the luteal phase than the follicular phase. Standard estrogen deviations were also larger during the luteal period. This demonstrated the occurrence of increased fluctuation or dispersion in the estrogen levels during that phase [

13,

30].

The study found that estrogen levels average 108.02 pg/mL during the luteal phase and 33.59 pg/mL during the follicular phase (p = 0.01).

The study findings also revealed that the increase in estrogen concentrations is followed by a shift in the tympanoplasty success rate, with the dominance of the luteal phase giving way to the follicular phase.

5. Conclusion

Future studies on women undergoing tympanoplasty should also take the menstrual cycle into account.

Limitations

The primary limitations of this study include its hypothesis-generating design and relatively small sample size. Despite these constraints, the findings offer a valuable foundation for further research into the effect of menstrual cycle phases on tympanoplasty outcomes. Further studies involving larger patient cohorts are warranted to validate and expand upon these preliminary results.

Author Contributions

Nurcan Yoruk: Designed the research and wrote the paper; Ozgur Yoruk: Designed and performed the study and acquisition of data. Hazal Altunok: Designed the research. Erdi Özdemir: Designed and performed the study and acquisition of data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

Data may be provided on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Informed Consent

The authors declare that the patients included in the study signed informed consent forms to use their medical information in the studies.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Evman, M.D.; Cakil, T. Effect of type 1 tympanoplasty on health-related quality of life assessed by chronic otitis media questionnaire 12. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 34–38.

- Aslan, G.G.; Aghayarov, O.Y.; Pekçevik, Y.; Arslan, İ.B.; Çukurova, İ.; Aslan, A. Comparison of tympanometric volume measurement with temporal bone CT findings in the assessment of mastoid bone pneumatization in chronic otitis media patients. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 27, 6–10.

- Gutierrez, J.A. 3rd; Cabrera, C.I.; Stout, A.; Mowry, S.E. Tympanoplasty in the setting of complex middle ear pathology: A systematic review. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2023, 132, 1453–1466. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Lou, Z. Inside-out raising mucosal-tympanomeatal flap approach for the repair of large marginal perforations. BMC Surg. 2023, 23, 378. [CrossRef]

- Tahiri, I.; El Houari, O.; Hajjij, A.; Essaadi, M.; Benariba, F. Influence of the size and location of the perforation on the anatomical results of myringoplasty. Cureus 2023, 15, e37221. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onal, K.; Uguz, M.Z.; Kazikdas, K.C.; Gursoy, S.T.; Gokce, H. A multivariate analysis of otological, surgical and patient-related factors in determining success in myringoplasty. Clin. Otolaryngol. 2005, 30, 115–120. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gui, W.; Wu, C.; Wu, X. Analysis of the effect of reconstructing the ossicular chain under otoendoscopy with and without a stapes superstructure. Acta Otolaryngol. 2024, 144, 112–117. [CrossRef]

- Malafronte, G.; Fetoni, A.R.; Motta, G.; Presutti, L. The new semisynthetic TORP: A prosthesis for ossicular reconstruction both with the absence and the presence of the stapes superstructure. Otol. Neurotol. 2024, 45, 783–789. [CrossRef]

- Kasımay, Ö.; Şener, G.; Çakır, B.; Yüksel, M.; Çetinel, Ş.; Contuk, G.; Yeğen, B.Ç. Estrogen protects against oxidative multiorgan damage in rats with chronic renal failure. Ren. Fail. 2009, 31, 711–725. [CrossRef]

- Lou, Z.C. Healing mechanisms of human traumatic tympanic membrane perforations. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 149, 2S. [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Zhang, S.; Gong, X.; Wang, X.; Lou, Z.H. Endoscopic observation of different repair patterns in human traumatic tympanic membrane perforations. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 84, 545–552. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harvie, M.; Roy, C.F.; Gurberg, J. Traumatic tympanic membrane perforations. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2024, 196, E100. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekmekyapar, T.; Ozcan, C.; Ciftci, O. Relationships of total leukocyte, neutrophil and lymphocyte levels with the menstrual cycle in patients receiving fingolimod treatment. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 25, 447–454. [PubMed]

- Abidi, S.; Nili, M.; Serna, S.; Kim, S.; Hazlett, C.; Edgell, H. Influence of sex, menstrual cycle, and oral contraceptives on cerebrovascular resistance and cardiorespiratory function during valsalva or standing. J. Appl. Physiol. 2017, 123, 375–386. [CrossRef]

- Committee on Hearing and Equilibrium guidelines for the evaluation of hearing preservation in acoustic neuroma (vestibular schwannoma). American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, INC. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1995, 113, 179–180.

- Lou, Z.C.; Lou, Z.H. A moist edge environment aids the regeneration of traumatic tympanic membrane perforations. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2017, 131, 564–571. [CrossRef]

- Guneri, E.A.; Tekin, S.; Yilmaz, O.; Ozkara, E.; Erdağ, T.K.; Ikiz, A.O.; Sarioğlu, S.; Güneri, A. The effects of hyaluronic acid, epidermal growth factor, and mitomycin in an experimental model of acute traumatic tympanic membrane perforation. Otol. Neurotol. 2003, 24, 371–376. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schart-Morén, N.; Mannström, P.; Rask-Andersen, H.; von Unge, M. Effects of mechanical trauma to the human tympanic membrane: An experimental study using transmission electron microscopy. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017, 137, 928–934. [CrossRef]

- Makuszewska, M.; Cieślińska, M.; Winnicka, M.M.; Skotnicka, B.; Niemczyk, K.; Bonda, T. Enhanced expression of plasminogen activators and inhibitor in the healing of tympanic membrane perforation in rats. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2023, 24, 159–170. [CrossRef]

- Liew, L.J.; Wang, A.Y.; Dilley, R.J. Isolation of epidermal progenitor cells from rat tympanic membrane. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 2029, 247–255.

- Lou, Z.C. Spontaneous healing of traumatic eardrum perforation: Outward epithelial cell migration and clinical outcome. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2012, 147, 1114–1119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastar, I.; Stojadinovic, O.; Yin, N.C.; Ramirez, H.; Nusbaum, A.G.; Sawaya, A.; Patel, S.B.; Khalid, L.; Isseroff, R.R.; Tomic-Canic, M. Epithelialization in wound healing: A comprehensive review. Adv. Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2014, 3, 445–464. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savoia, P.; Raina, G.; Camillo, L.; Farruggio, S.; Mary, D.; Veronese, F. Anti-oxidative effects of 17 beta-estradiol and genistein in human skin fibroblasts and keratinocytes. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2018, 92, 62–77. [CrossRef]

- Tresguerres, J.A.; Kireev, R.; Tresguerres, A.F.; Borrás, C.; Vara, E.; Ariznavarreta, C. Molecular mechanisms involved in the hormonal prevention of aging in the rat. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 108, 318–326. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, M.J. Estrogens and aging skin. Dermatoendocrinology 2013, 5, 264–270. [CrossRef]

- Rzepecki, A.K.; Murase, J.E.; Juran, R.; Fabi, S.G.; McLellan, B.N. Estrogen-deficient skin: The role of topical therapy. Int. J. Womens Dermatol. 2019, 5, 85–90. [CrossRef]

- Zhuge, Y.; Regueiro, M.M.; Tian, R.; Li, Y.; Xia, X.; Vazquez-Padron, R.; Elliot, S.; Thaller, S.R.; Liu, Z.J.; Velazquez, O.C. The effect of estrogen on diabetic wound healing is mediated through increasing the function of various bone marrow-derived progenitor cells. J. Vasc. Surg. 2018, 68, 127S–135S. [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Chen, Y.; Guo, D.; Deng, Y.; Guo, W.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Lu, H.; Liu, A.; Zhu, J.; Li, F. Rhein promotes the proliferation of keratinocytes by targeting oestrogen receptors for skin ulcer treatment. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2022, 22, 209. [CrossRef]

- Barati, B.; Abtahi, S.H.; Hashemi, S.M.; Okhovat, S.A.; Poorqasemian, M.; Tabrizi, A.G. The effect of topical estrogen on healing of chronic tympanic membrane perforations and hearing threshold. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013, 18, 99–102.

- Stickford, A.S.L.; Vangundy, T.B.; Levine, B.D.; Fu, Q. Menstrual cycle phase does not affect sympathetic neural activity in women with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome. J. Physiol. 2015, 593, 2131–2143. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).