Submitted:

20 May 2025

Posted:

21 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Research on the Fire-Resistance of Beams

1.2. Calculation Method from GB 51249-2017

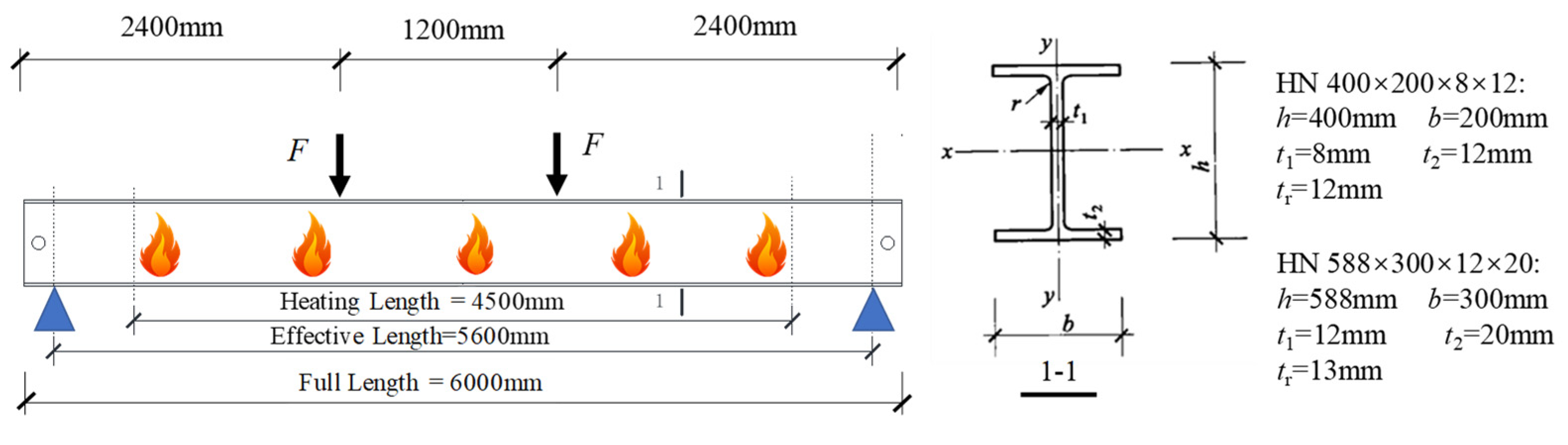

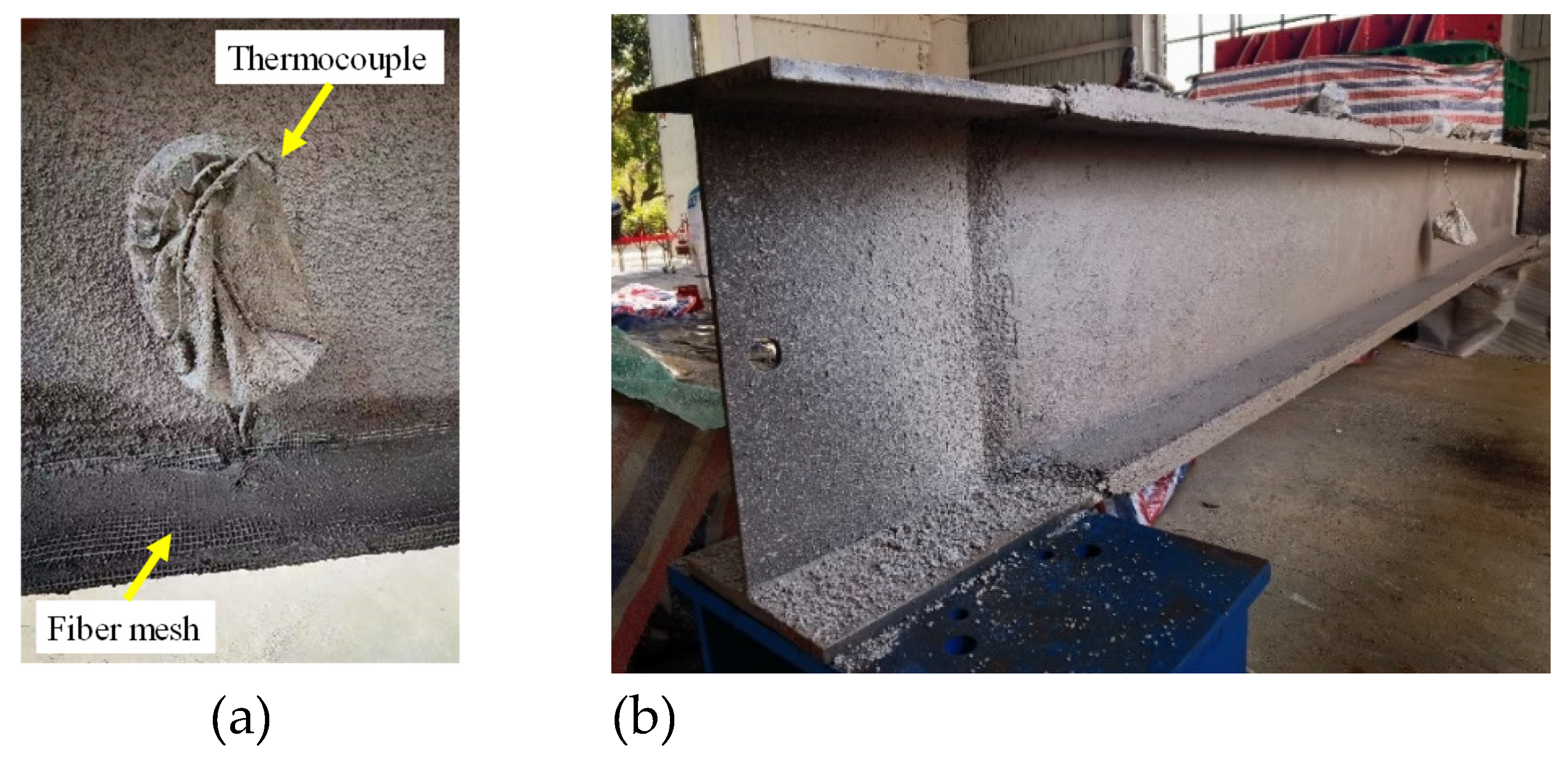

2. The Specimens

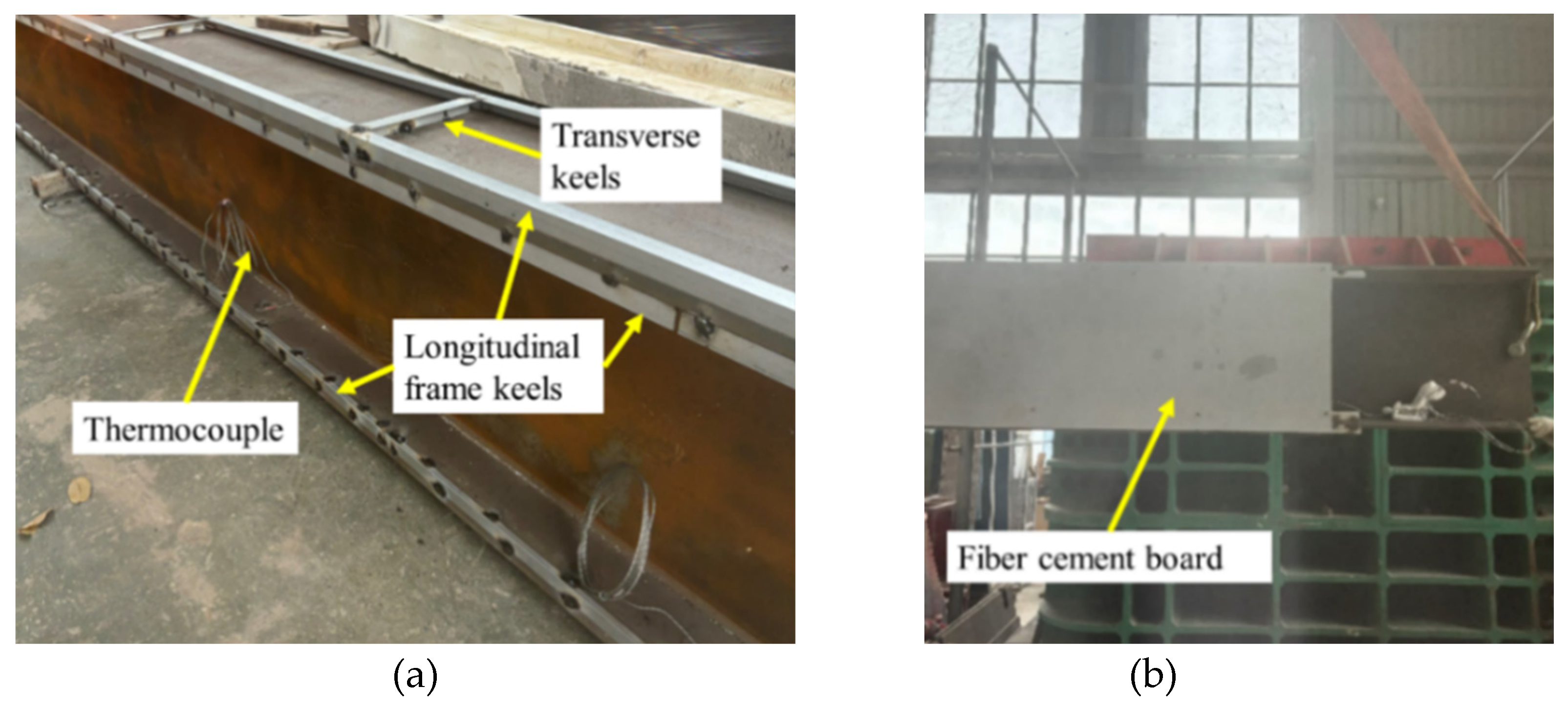

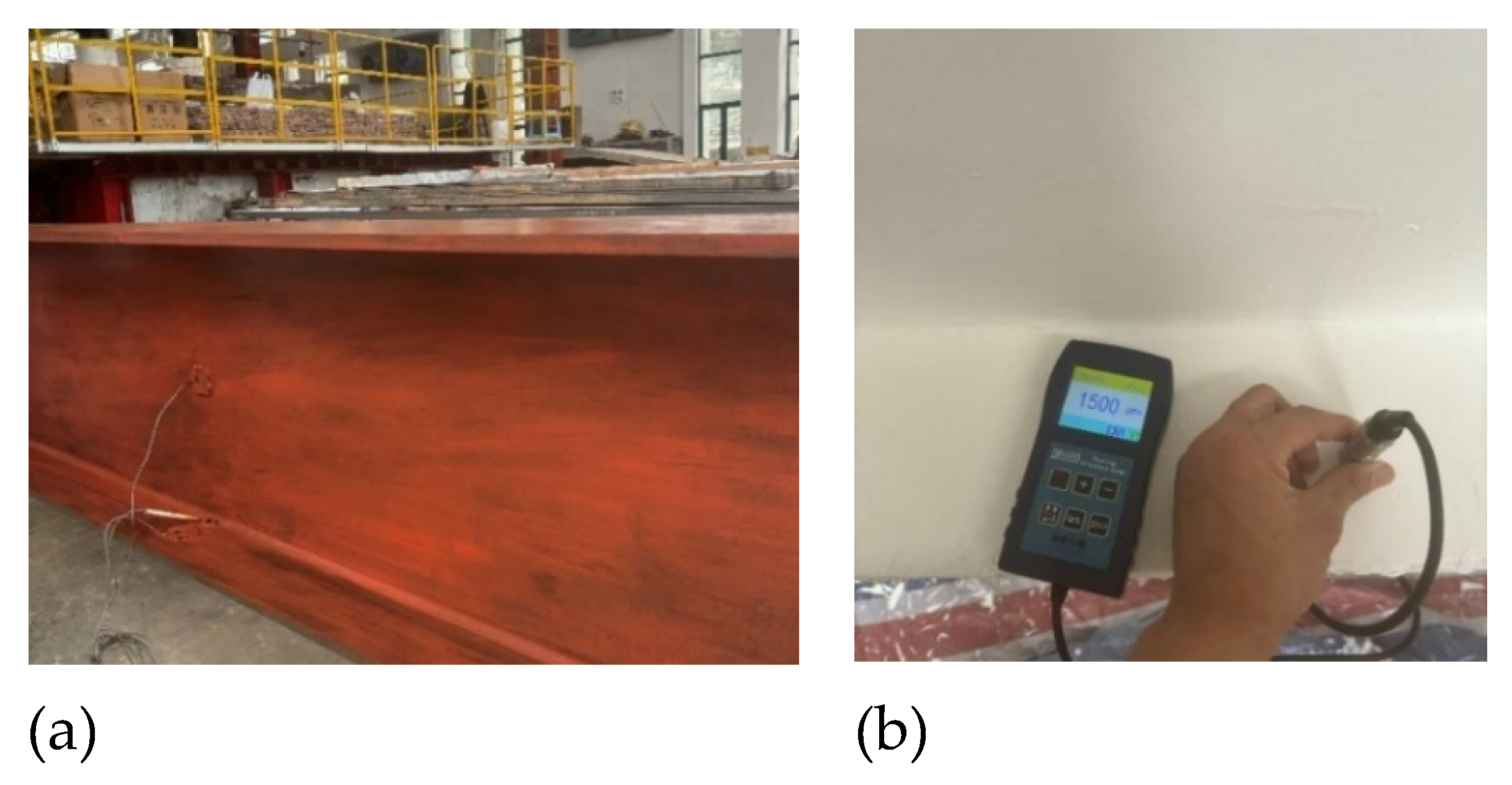

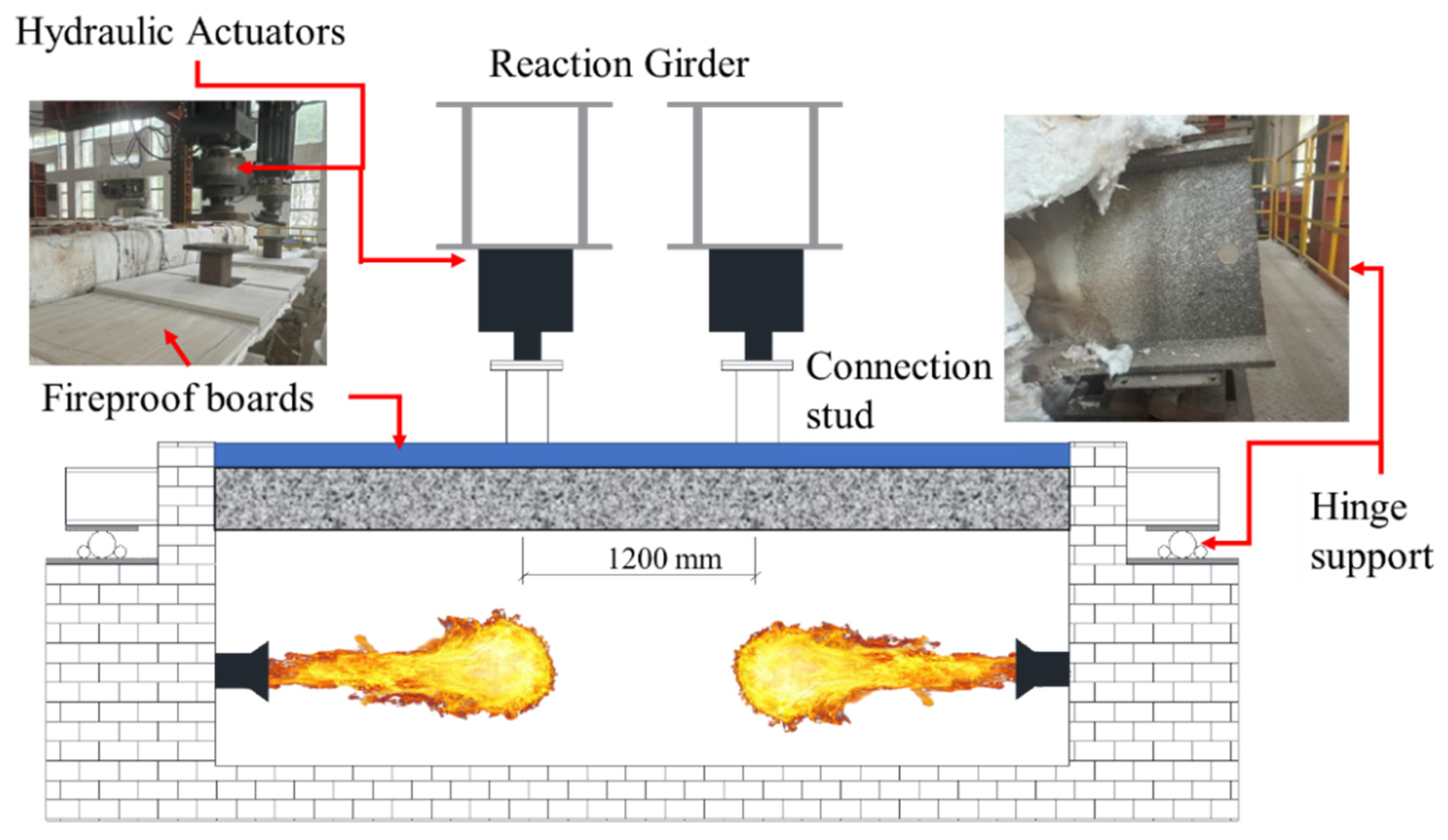

3. Test Set-Up

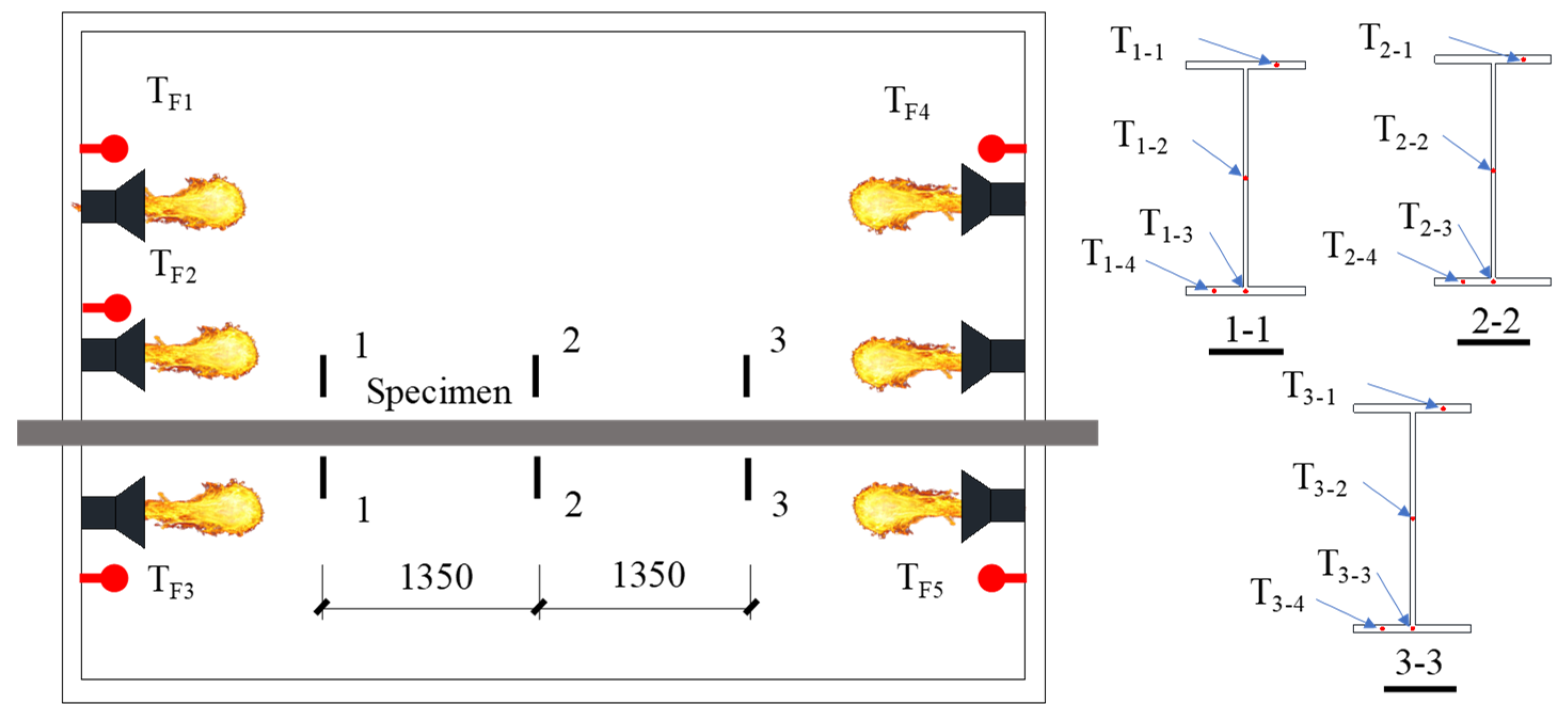

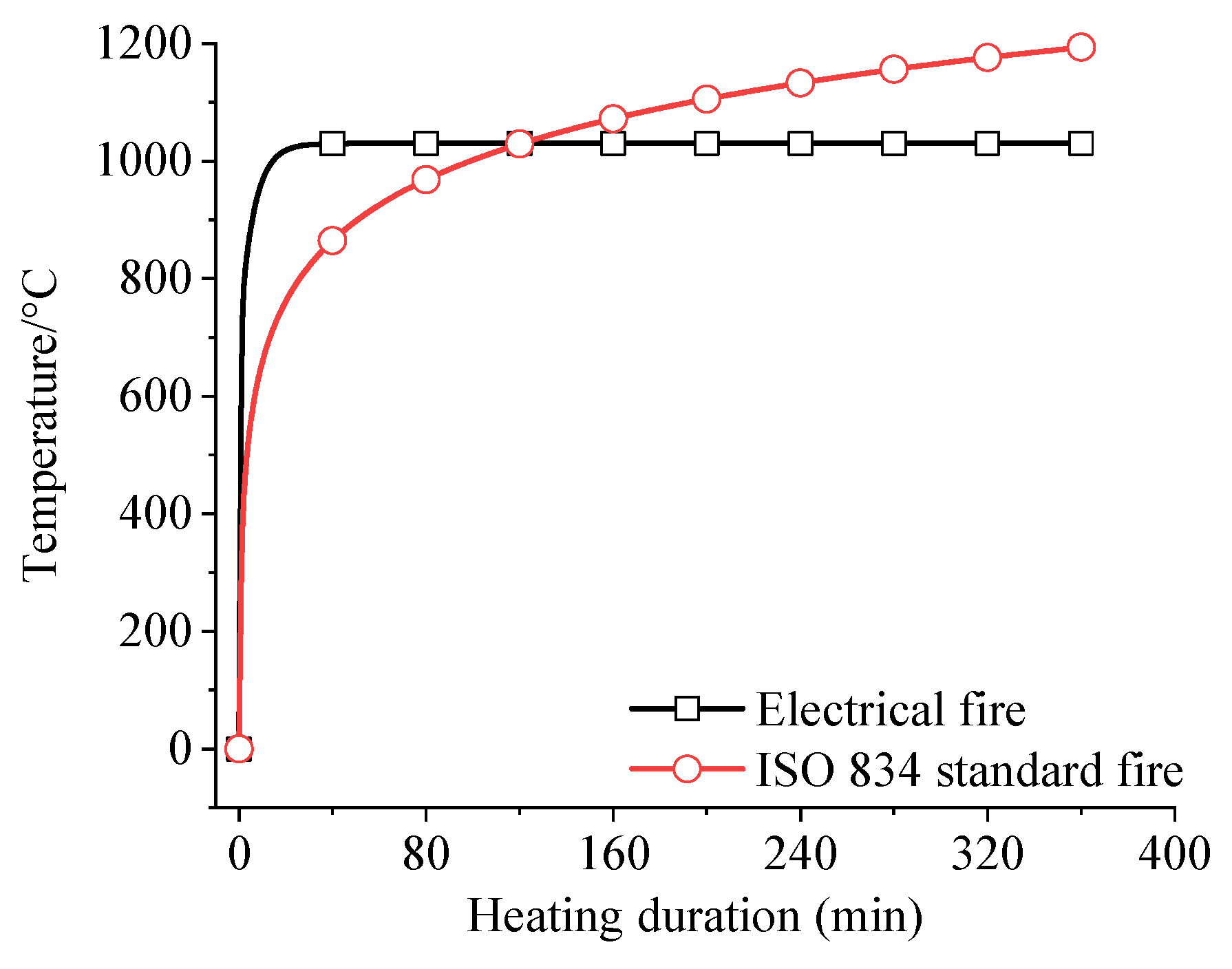

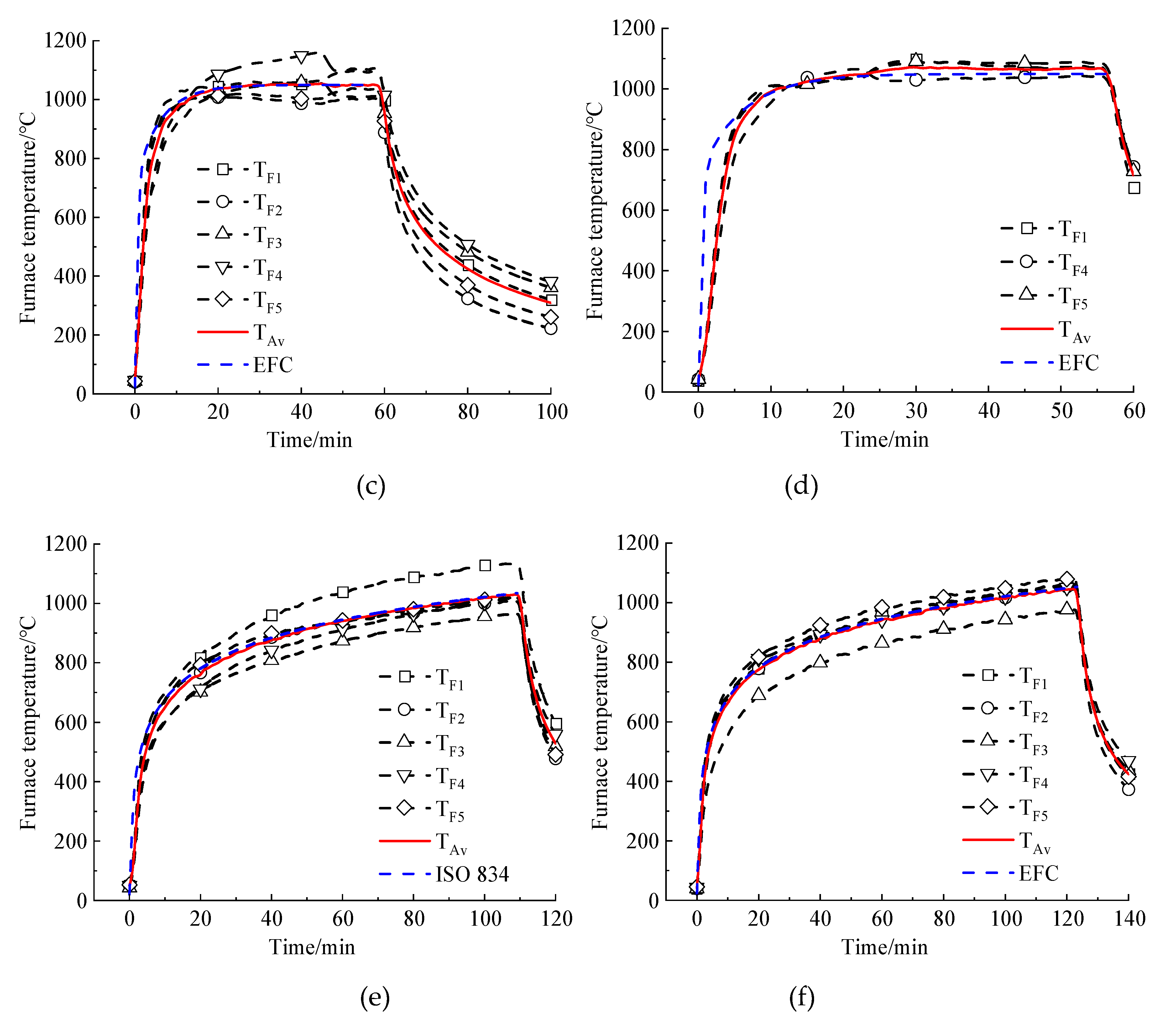

4. Test Program

5. Test Results

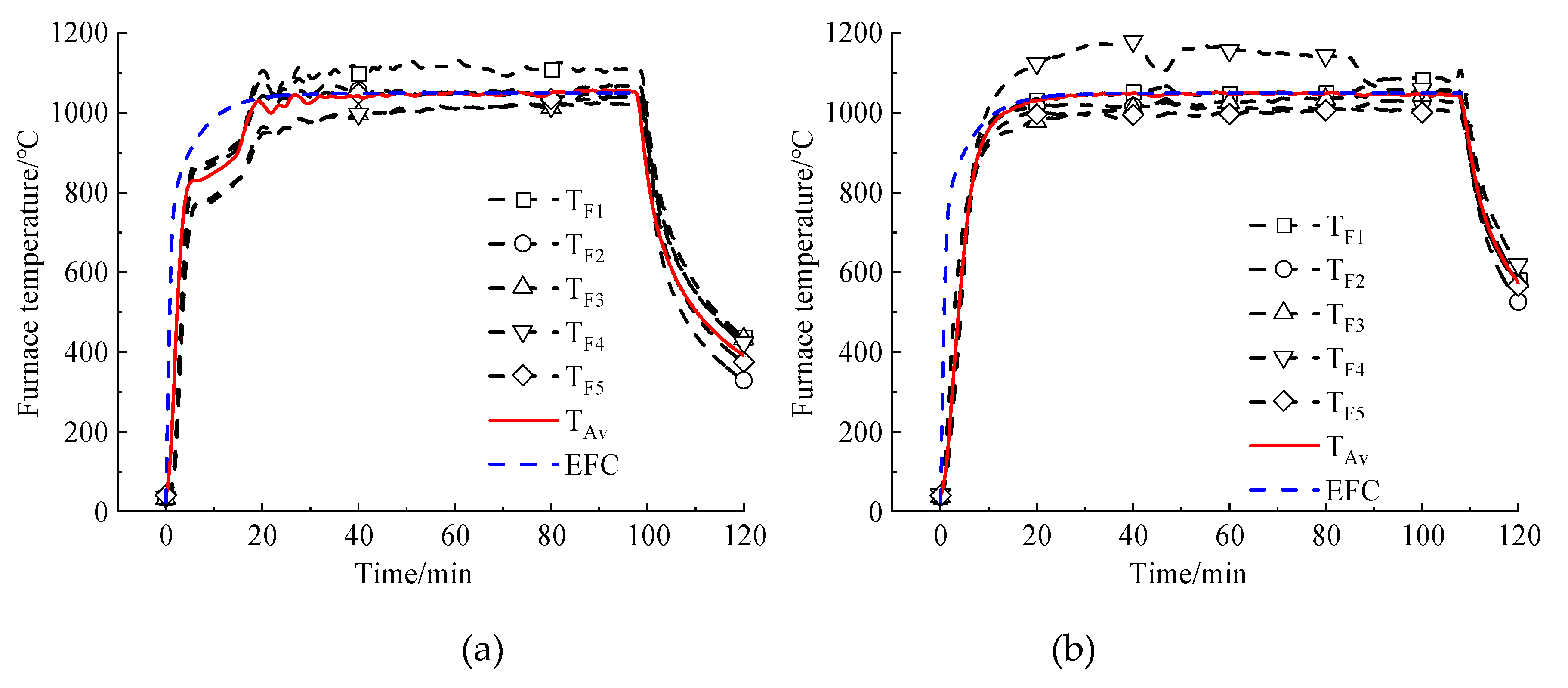

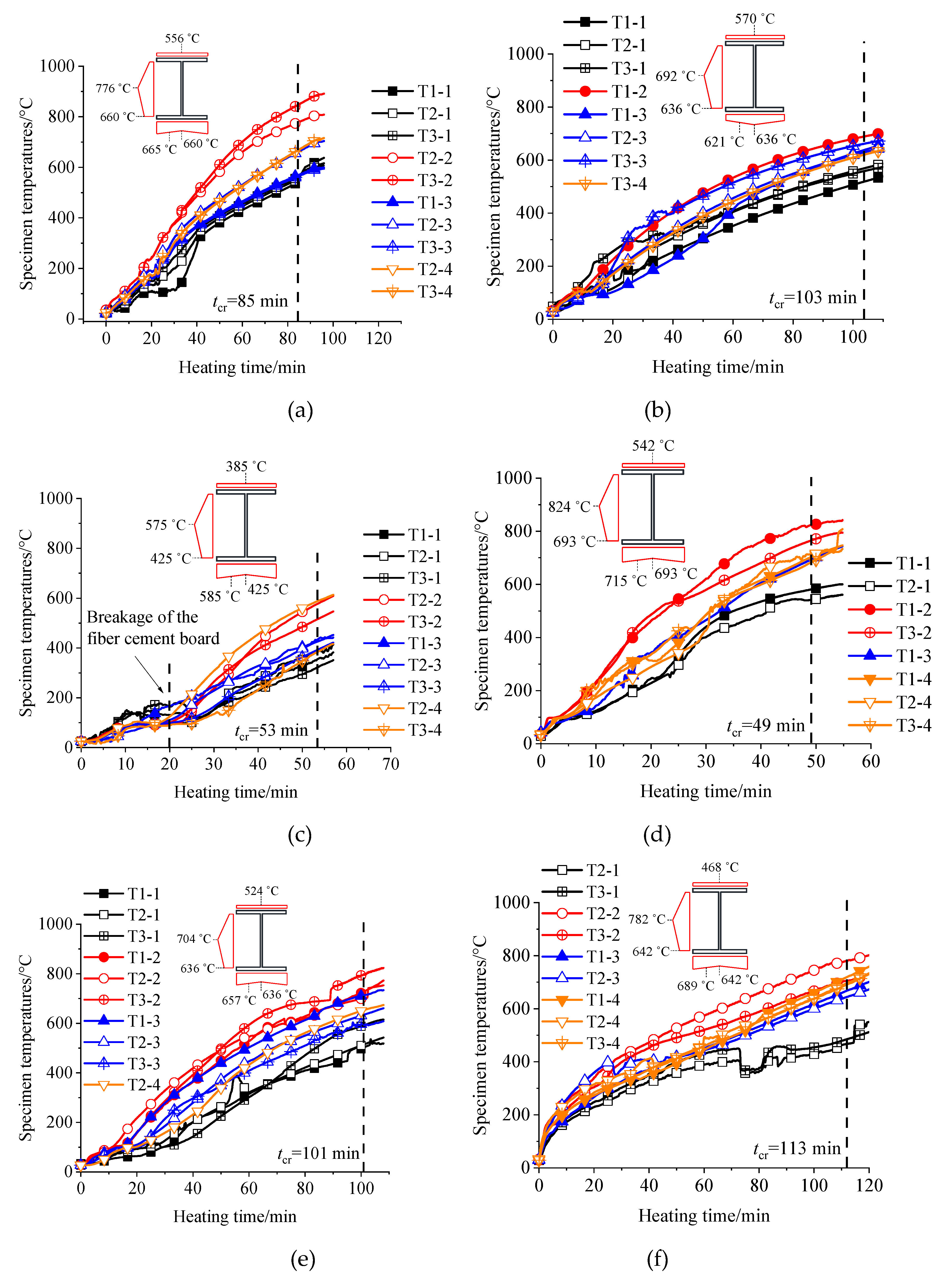

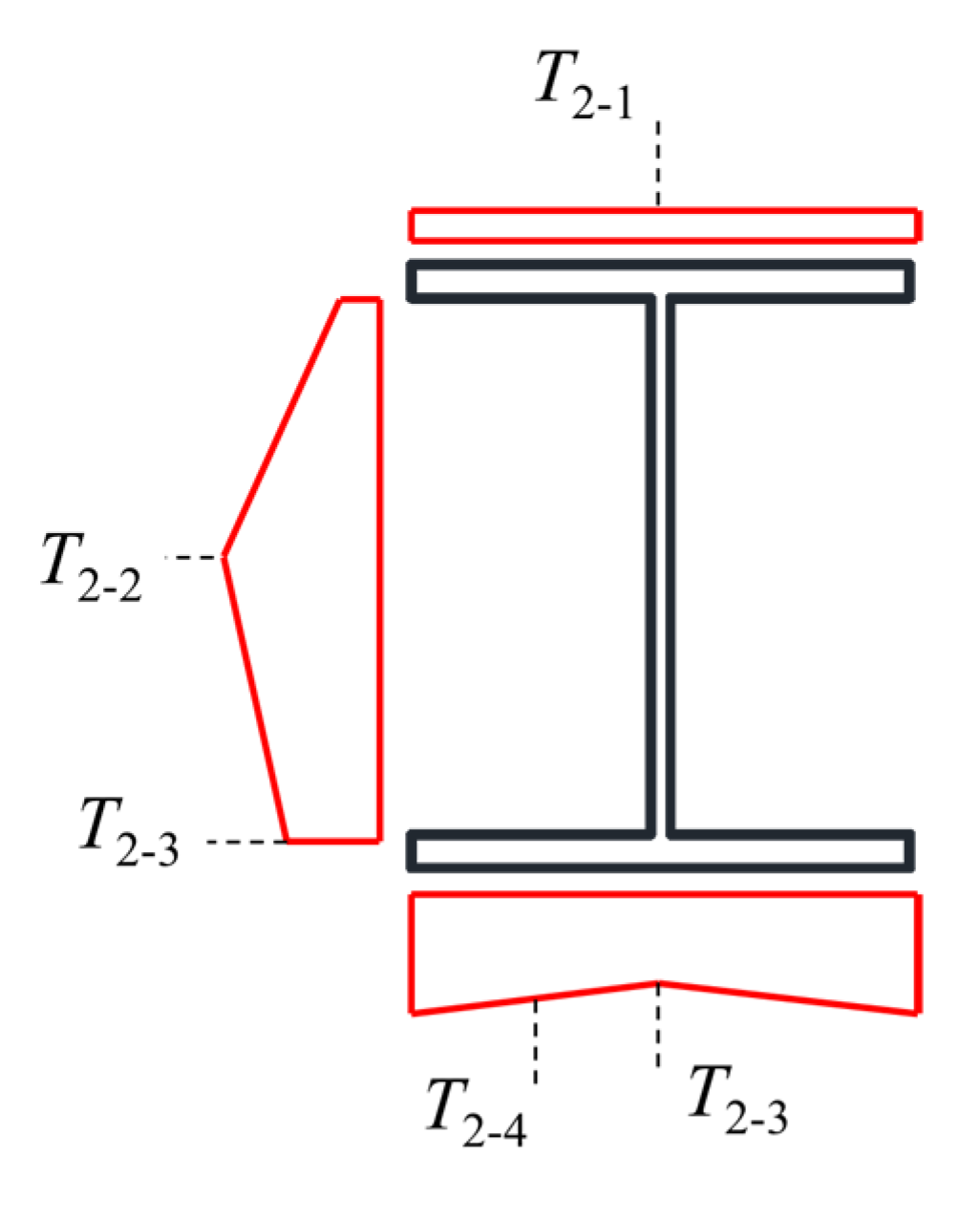

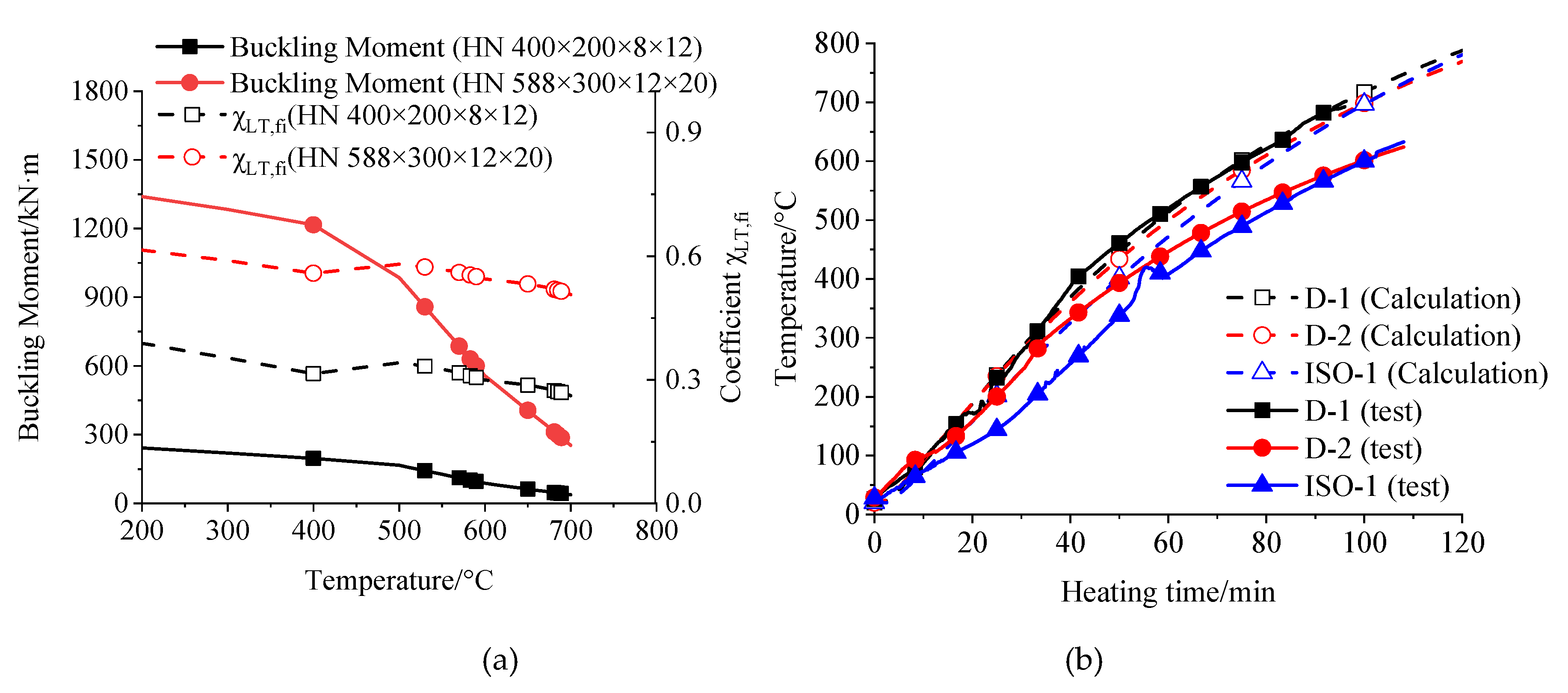

5.1. Temperature Results

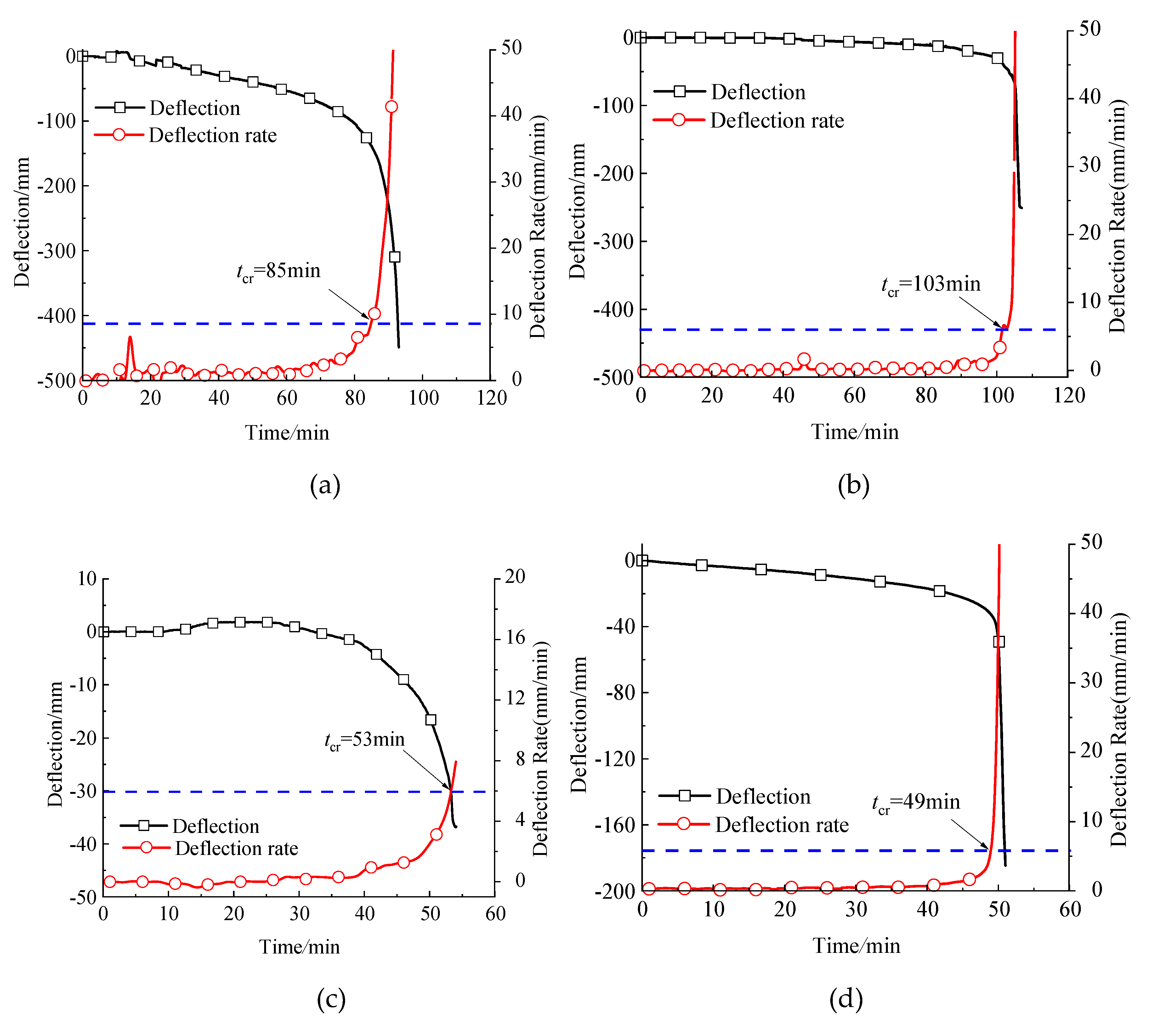

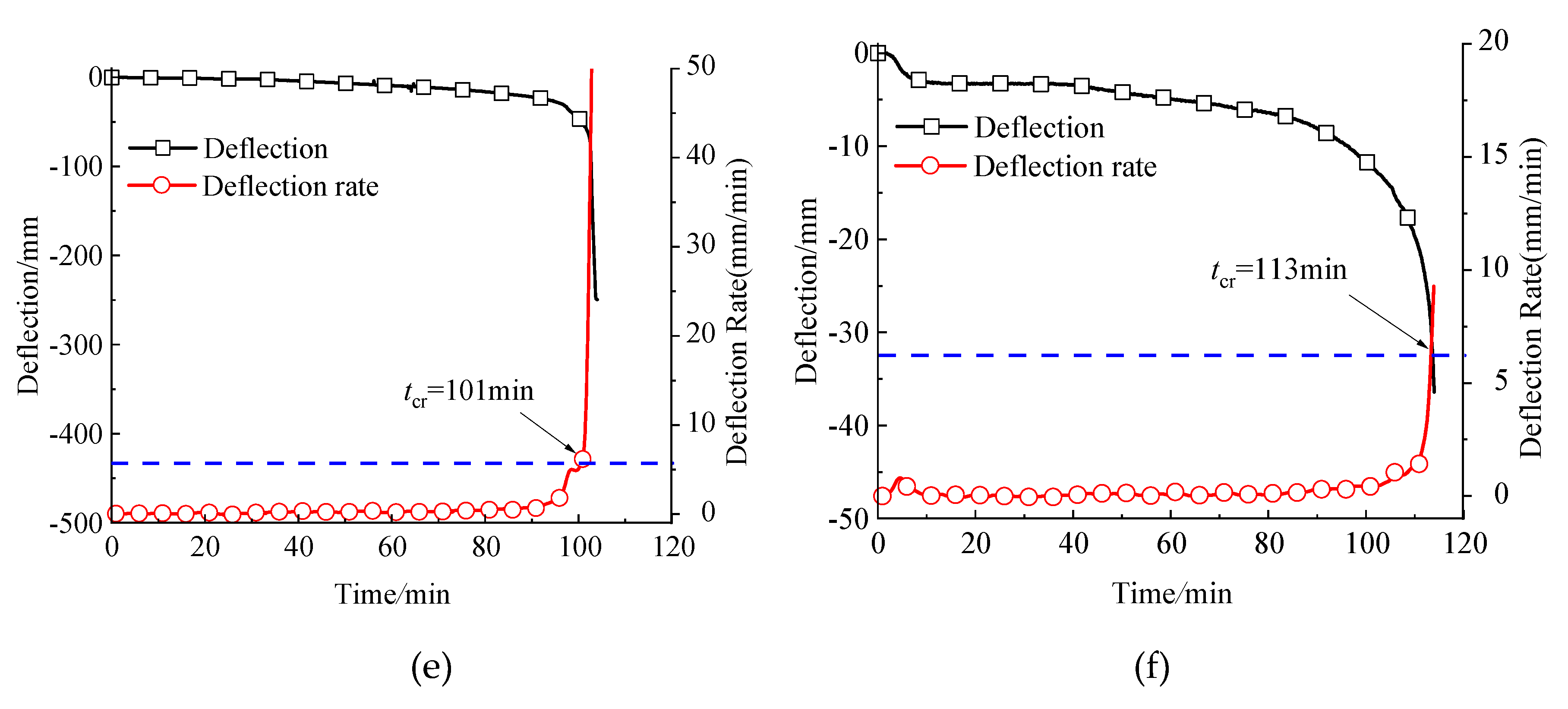

5.2. Displacement Results

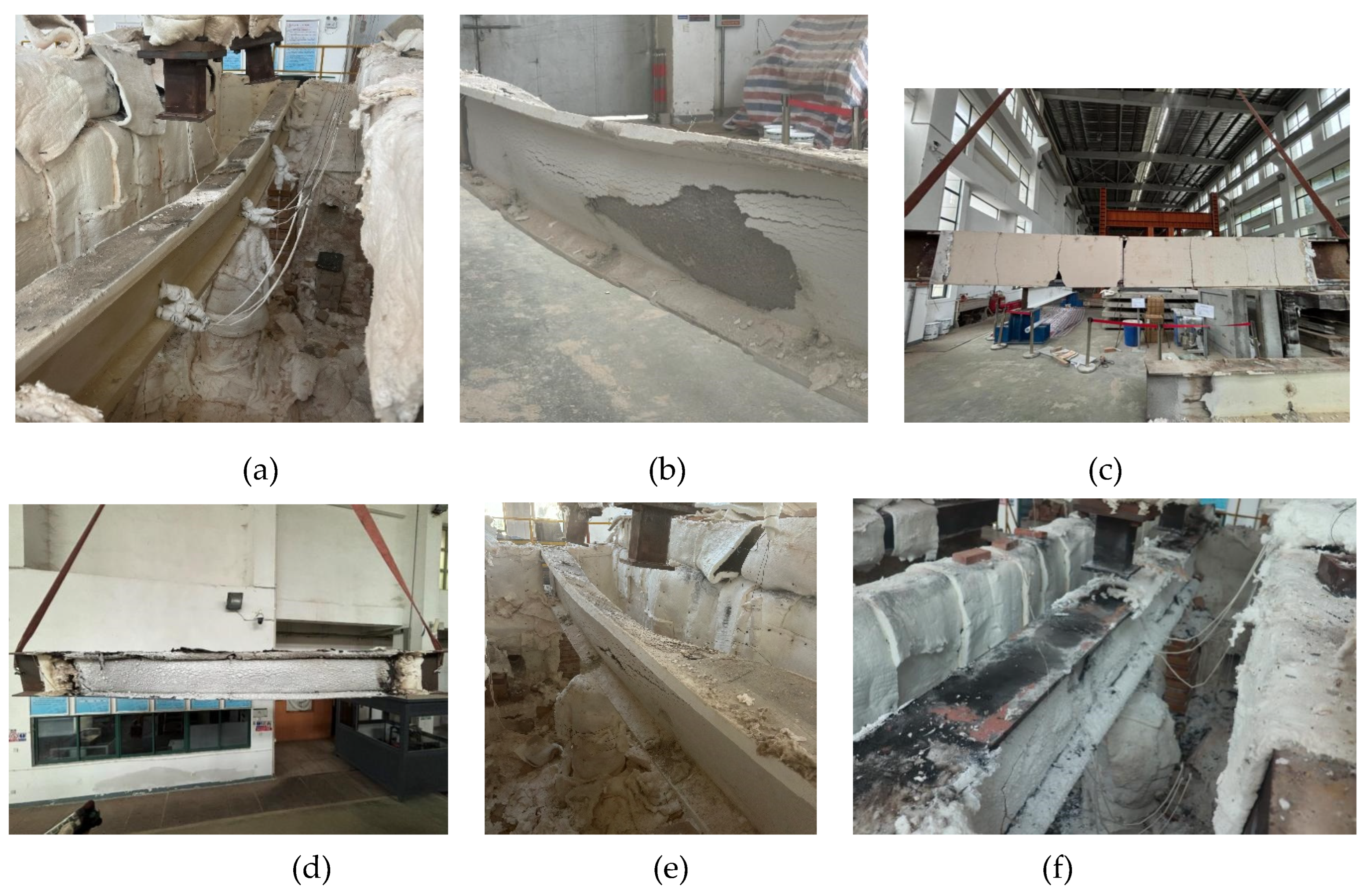

5.3. Test Phenomenon

5.4. Discussion of the Test Results

6. Evaluation of BS EN 1993-1-2

6.1. Critical Temperature

6.2. Fire Resistance

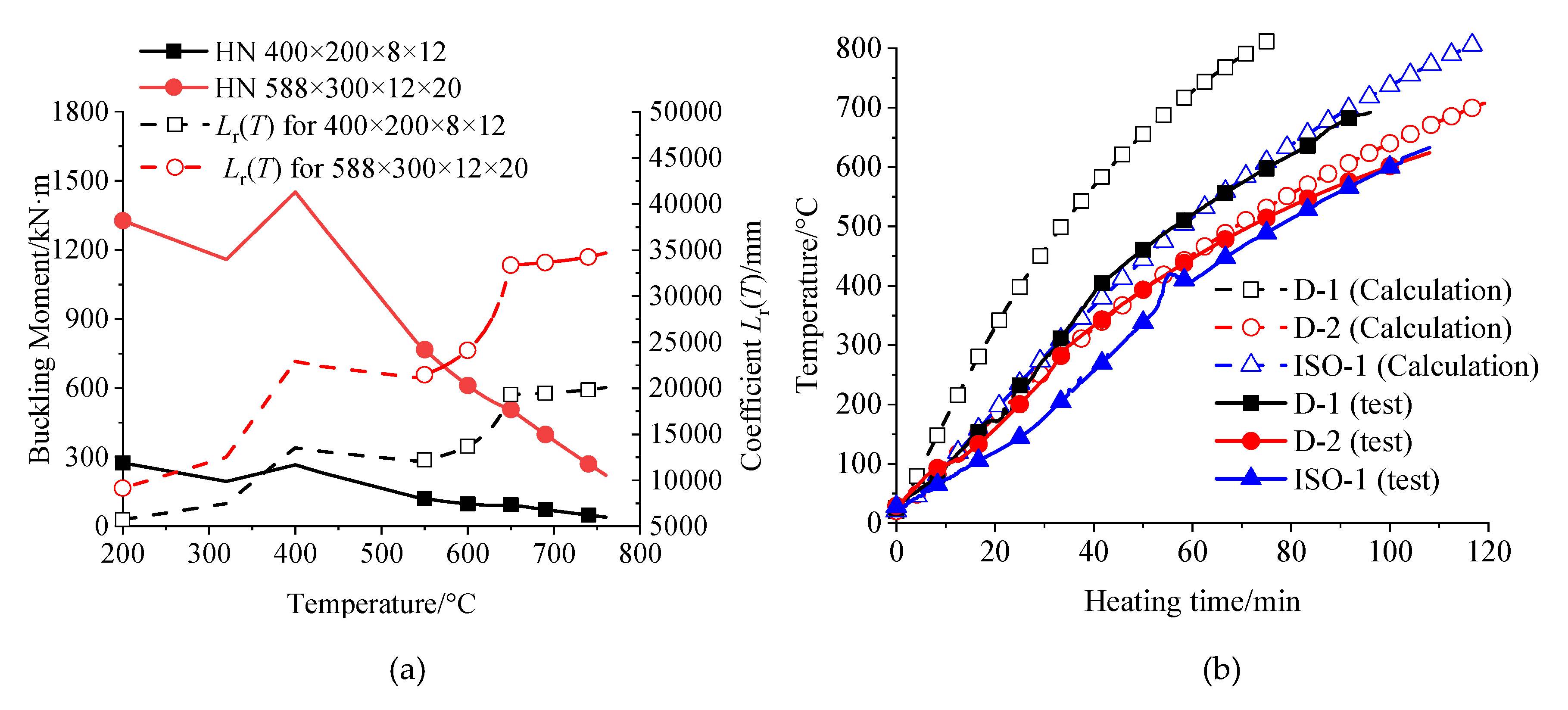

7. Evaluation of ANSI/AISC 360-22

7.1. Critical Temperature

7.2. Fire Resistance

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Burgess I W, Rimawi J E, Plank R J. Studies of the Behaviour of Steel Beams in Fire[J]. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 1991(19):285-312. [CrossRef]

- Liu T C H, Fahad M K, Davies J M. Experimental investigation of behaviour of axially restrained steel beams in fire[J]. Journal of constructional steel research, 2002,58(9):1211-1230. [CrossRef]

- Yin Y Z, Wang Y C. A numerical study of large deflection behaviour of restrained steel beams at elevated temperatures[J]. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 2004,60(7):1029-1047.

- Li G, Guo S. Experiment on restrained steel beams subjected to heating and cooling[J]. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 2008,64(3):268-274. [CrossRef]

- Tan K, Huang Z. Structural Responses of Axially Restrained Steel Beams with Semirigid Moment Connection in Fire[J]. Journal of structural engineering (New York, N.Y.), 2005,131(4):541-551. [CrossRef]

- Huang Z, Tan K. Structural response of restrained steel columns at elevated temperatures. Part 2: FE simulation with focus on experimental secondary effects[J]. Engineering Structures, 2007,29(9):2036-2047. [CrossRef]

- Dwaikat M, Kodur V. Engineering Approach for Predicting Fire Response of Restrained Steel Beams[J]. Journal of engineering mechanics, 2011,137(7):447-461. [CrossRef]

- Kodur V K R, Dwaikat M M S. Effect of high temperature creep on the fire response of restrained steel beams[J]. Materials and Structures, 2010,43(10):1327-1341.

- Al-azzani H, Yang J, Sharhan A, et al. A Practical Approach for Fire Resistance Design of Restrained High-Strength Q690 Steel Beam Considering Creep Effect[J]. Fire Technology, 2021,57(4):1683-1706. [CrossRef]

- Shakil S, Lu W, Puttonen J. Behaviour of vertically loaded steel beams under a travelling fire[J]. Structures, 2022,44:1-17. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen T Q, Nguyen X T, Nguyen T N M, et al. Buckling strength of steel I-beams subjected to simultaneous transverse loads and negative end moments under elevated temperature[J]. Structures, 2024,67:106934.

- Laím L, Rodrigues J P C. Experimental and numerical study on the fire response of cold-formed steel beams with elastically restrained thermal elongation[J]. Journal of Structural Fire Engineering, 2016,7(4):388-402.

- Couto C, Vila Real P, Lopes N. Local-global buckling interaction in steel I-beams—A European design proposal for the case of fire[J]. Thin-Walled Structures, 2025,206:112664. [CrossRef]

- Xie B, Dai W, Zhang S, et al. Experimental and numerical investigation on fire resistance of stainless steel core plate beams[J]. Thin-Walled Structures, 2023,190:110948. [CrossRef]

- Kucukler, M. Kucukler M. Stainless steel I-section beams at elevated temperatures: Lateral–torsional buckling behaviour and design[J]. Thin-Walled Structures, 2025,208:112720. [CrossRef]

- Pournaghshband A, Afshan S, Theofanous M. Elevated temperature performance of restrained stainless steel beams[J]. Structures, 2019,22:278-290. [CrossRef]

- Shaheen M A, Afshan S, Foster A S. Performance of axially restrained carbon and stainless steel perforated beams at elevated temperatures[J]. Advances in Structural Engineering, 2021,24(15):3564-3579. [CrossRef]

- GB 51249-2017. Code for fire safety of steel structures in buildings [S]. China Planning Press, 2017, Beijing. (In Chinese).

- GB 50017-2017. Standard for design of steel structures [S]. China Architecture & Building Press, 2017, Beijing. (In Chinese).

- ISO-834. Fire-resistance tests - Elements of building construction [S]. International Organization for Standardization, 1975, Geneva.

- GB/T 26784-2011. Fire resistance test for elements of building construction - Alternative and additional procedures [S]. Standards Press of China, 2011, Beijing. (In Chinese).

- GB9978.1-2008. Fire-resistance tests - Elements of building construction - Part 1: General requirements [S]. Standards Press of China, 2008, Beijing. (In Chinese).

- BS EN 1993-1-2:2024. Eurocode 3 - Design of steel structures. Part 1-2: Structural fire design [S]. British Standards Institution, 2024, London.

- ANSI/AISC 360-22. Specification for Structural Steel Buildings [S]. American Institute of Steel Construction, 2022, Washington.

| Labels | Yield strength /MPa |

Average Yield strength/MPa | Ultimate strength /MPa |

Average ultimate strength /MPa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-8-1 | 401.6 | 401.7 | 549.4 | 549.6 |

| C-8-2 | 402.5 | 549.6 | ||

| C-8-3 | 401.0 | 549.7 | ||

| C-12-1 | 403.0 | 406.0 | 542.6 | 539.6 |

| C-12-2 | 410.3 | 538.2 | ||

| C-12-3 | 404.8 | 538.1 | ||

| C-20-1 | 405.9 | 404.5 | 564.6 | 563.8 |

| C-20-2 | 398.2 | 563.9 | ||

| C-20-3 | 409.3 | 562.8 |

| Labels | Dimensions /mm |

Heating curves |

Fire Protections |

Thickness /mm |

Applied load /kN |

Tcr /˚C |

tcr /min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-1 | HN 400×200×8×12 | EFC | FRC | 20 | 36 | 676 | 120 |

| D-2 | HN 588×300×12×20 | EFC | FRC | 15 | 120 | 661 | 120 |

| D-3 | HN 588×300×12×20 | EFC | FCB | 20 | 120 | 661 | 120 |

| D-4 | HN 588×300×12×20 | EFC | IC | 1.5 | 120 | 661 | 60 |

| ISO-1 | HN 588×300×12×20 | ISO-834 | FRC | 12 | 120 | 661 | 120 |

| ISO-2 | HN 588×300×12×20 | ISO-834 | IC | 2.5 | 120 | 661 | 120 |

| Lables |

Tcr,d (˚C) |

T2-1 (˚C) |

T2-2 (˚C) |

T2-3 (˚C) |

T2-4 (˚C) |

Tcr,t (˚C) |

tcr,d (min) |

tcr,t (min) |

(Tcr,d-Tcr,t)/ Tcr,t | (tcr,d-tcr,t)/ tcr,t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-1 | 676 | 556 | 776 | 660 | 665 | 648 | 120 | 85 | 4.3% | 41% |

| D-2 | 661 | 570 | 692 | 636 | 621 | 610 | 120 | 103 | 8.3% | 17% |

| D-3 | 661 | 385 | 575 | 425 | 586 | 487 | 120 | 53 | 35.7% | 126% |

| D-4 | 661 | 542 | 824 | 693 | 715 | 663 | 60 | 49 | -0.3% | 22% |

| ISO-1 | 661 | 524 | 704 | 636 | 657 | 610 | 120 | 101 | 8.4% | 19% |

| ISO-2 | 661 | 468 | 782 | 642 | 689 | 612 | 120 | 113 | 8.0% | 6% |

| Lables | Tcr,t (˚C) | Tcr,EC3 (˚C) | tcr,t (˚C) | tcr,EC3 (˚C) | (Tcr,EC3-Tcr,t)/ Tcr,t | (tcr,EC3-tcr,t)/ tcr,t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-1 | 648 | 615 | 85 | 81 | -5% | -5% |

| D-2 | 610 | 697 | 103 | 101 | 14% | -2% |

| D-3 | 487 | - | 53 | - | ||

| D-4 | 663 | 697 | - | - | 5% | |

| ISO-1 | 610 | 697 | 101 | 100 | 14% | -1% |

| ISO-2 | 612 | 697 | - | - | 14% |

| Lables | Tcr,t (˚C) | T2-4 (˚C) | Tcr,ANSI (˚C) | (Tcr, ANSI -T2-4)/ T2-4 | (Tcr, ANSI -Tcr,t)/ Tcr,t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-1 | 648 | 665 | 675 | 1.5% | 4% |

| D-2 | 610 | 621 | 743 | 19.6% | 22% |

| D-3 | 487 | 586 | - | ||

| D-4 | 663 | 715 | 743 | 3.9% | 12% |

| ISO-1 | 610 | 657 | 743 | 13.1% | 22% |

| ISO-2 | 612 | 689 | 743 | 7.8% | 21% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).