Submitted:

04 June 2025

Posted:

04 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

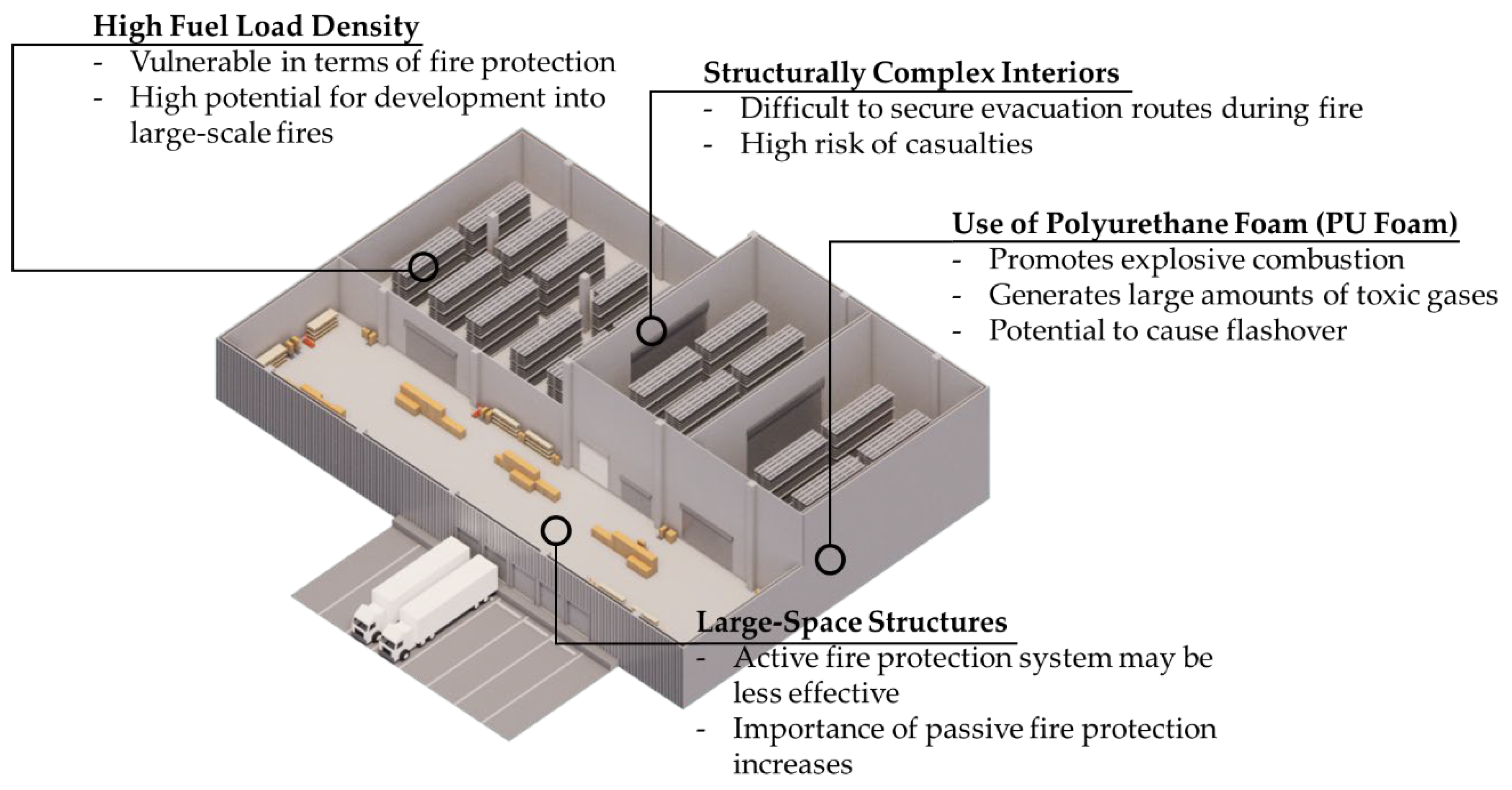

2. Importance of Fire Compartmentation According to the Fire Characteristics of Logistics Facilities and Problems with Existing Extended Application Methods

2.1. Fire Characteristics of Logistics Facilities and Performance of Fire Shutters

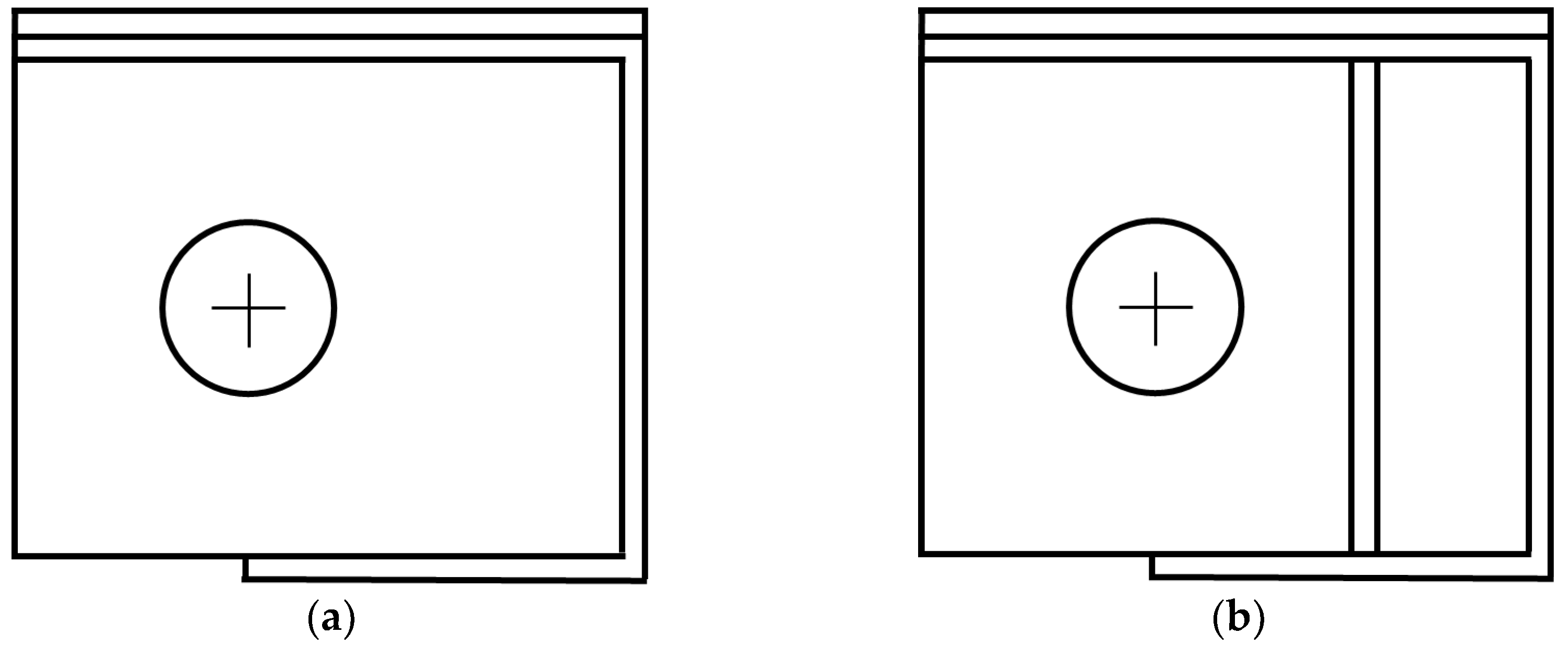

2.2. Issues in Performance Evaluation of Existing Large Fire Shutters and Proposal for Incorporating Deflection Criteria

2.3. Stress Analysis Incorporating Deflection Compared to the Conventional Calculation Method

3. Comparison of Deflection by Bracket Type and Optimal Deflection Design through Regression Analysis

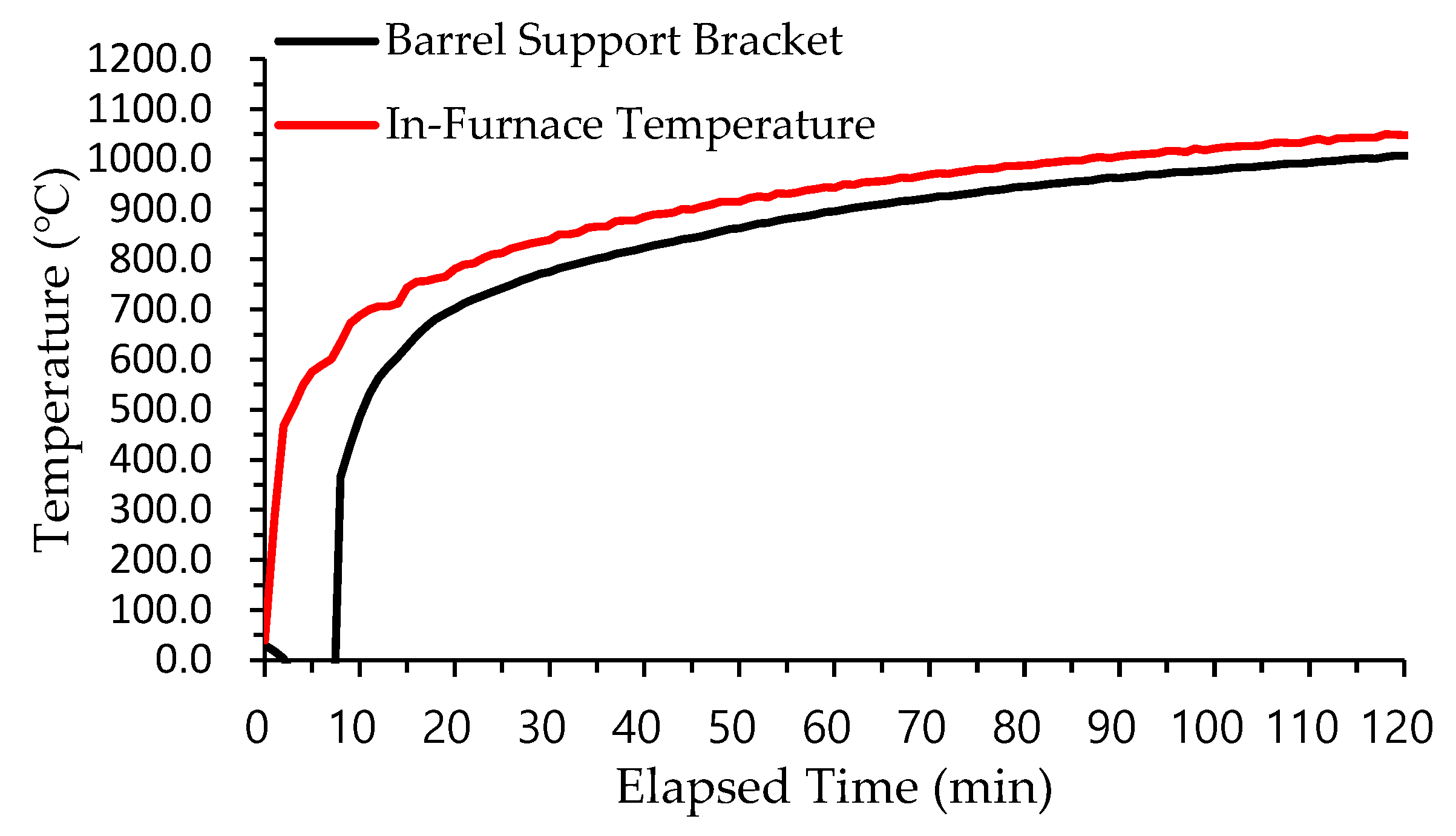

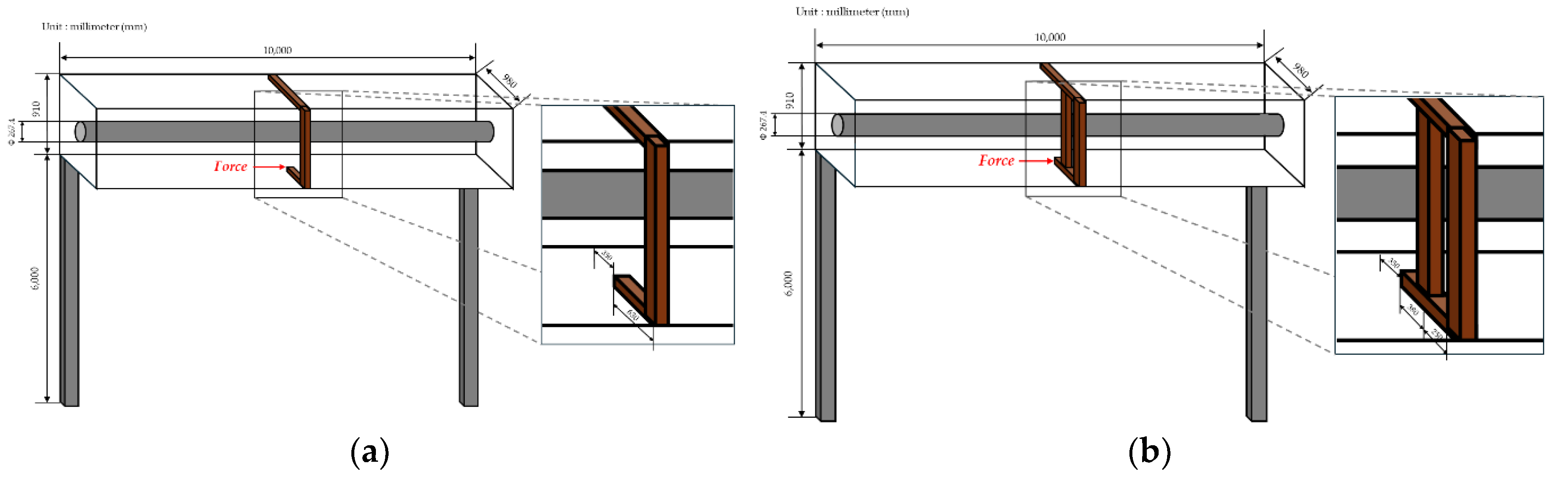

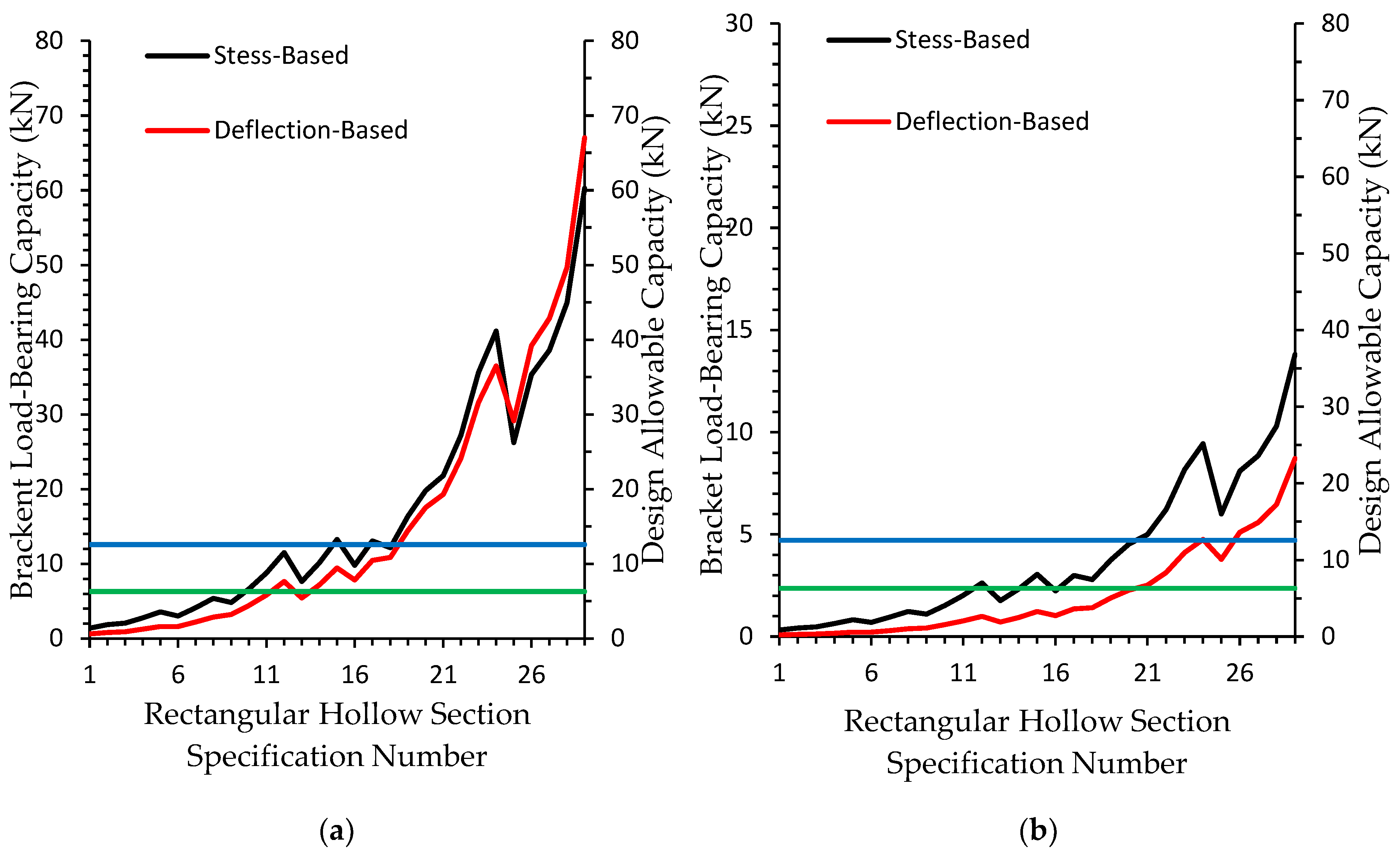

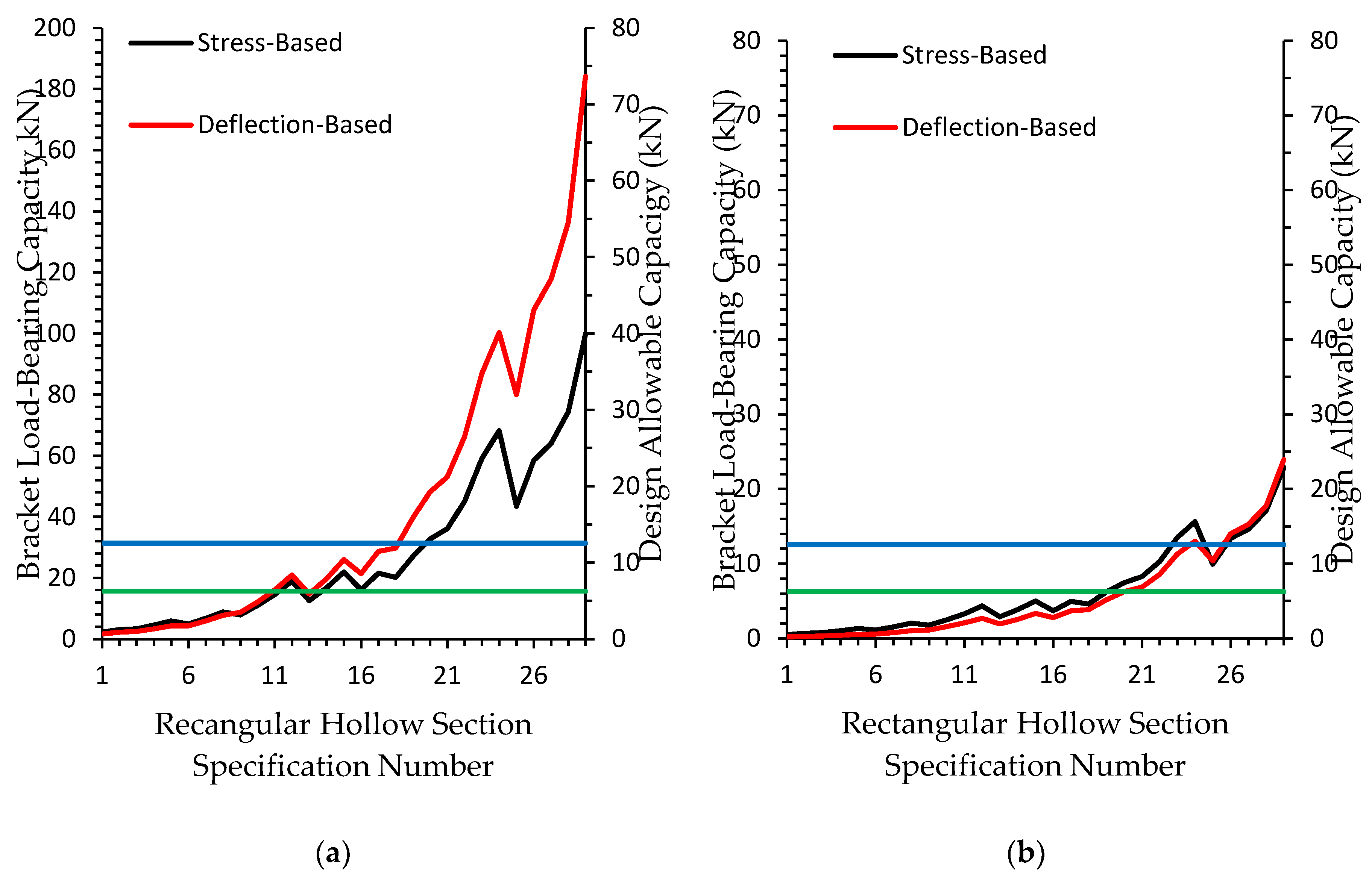

3.1. Comparison of Stress and Deflection at Ambient Temperature and 700 °C in Type - 1

3.2. Comparison of Stress and Deflection at Ambient Temperature and 700 °C in Type - 2

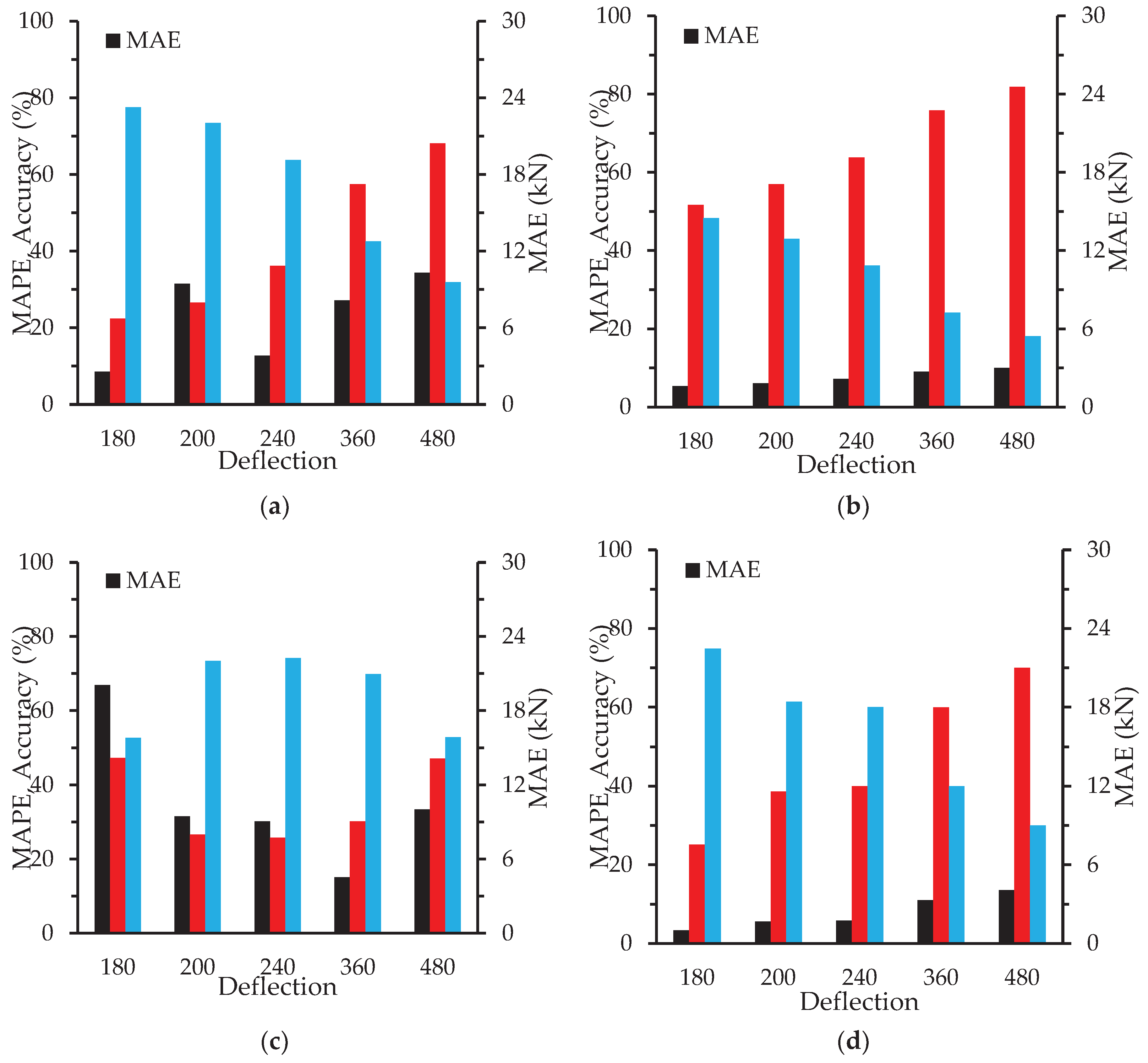

3.3. Application of Optimal Deflection Limits through Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, S.W. Characteristics & Fire Hazard Analysis of Logistics Warehouse and a Study on the Optimal Fire Detection Method - Focusing on the Air Sampling Detector -. 2023, Master’s thesis, Gachon University Graduate School of Industrial Environment. Seongnam, South Korea.

- You, H.J. A Study on the Fire Risk Analysis and Fire Fighting System of Large Logistis Warehouse. 2020, Master’s thesis, Gachon University Graduate School of Industrial Environment. Seongnam, South Korea.

- Kim, B.H. A Study on the Application of the Fire Shutter Detector according to the Height of the Ceiling in Warehouse. 2018, Master’s thesis, Seoul National University of Science and Technology.

- Causes and Safety Measures of Fire Accidents at Construction Sites; Standard Guidelines for Performance-Based Design Assessment of Fire Protection Facilities. Korea National Fire Agency, Seoul, Korea, 2023.

- Lee, S. B, Seo, H.W, Kim, D.H, Lee, G.Y. Study on Fire Load and Duration of Fire in Logistics Facilities. Journal of the Korea Society of Hazard Mitigation 2023, 23, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, T.H.; Park, S.H.; Kim, H.K. (2008). “A study on enhancing institutionalization on the fire analysis of the warehouse at Icheon City.” Proceedings of 2008 Spring Annual Conference of the Korean Institute of Fire Science and Engineering, pp. 80–84.

- Kim, M.S. A Study on the Fire Simulation of Refrigerated Warehouse for the Analysis of the Relationship between Oxygen Concentration and Fire Risk. 2023, Master’s thesis, Gachon University.

- Lee, Y.W. A Study on Performance Criteria for Fire Compartment and Fire Door. 2017, Master’s thesis, University of Korea.

- Lee, J.G.; Min, S.H. A Study on the Operational Characteristics and Adaptability of Sprinkler Systems in Frozen Warehouses. Journal of the Society of Disaster Information 2025, 21, 300–309. [Google Scholar]

- An, B.K.; Kim, W.H.; Yang, S.J.; Ham, E.G. A study on the improvement of field activity for firemen in sandwich panel warehouse. Journal of the Society of Disaster Information 2020, 16, 421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.S. Methodology for Predicting Fire Growth Curves Using Combustibles Based on Fire Risk Classification of Commodities in Rack Storage Warehouse. 2025, Doctoral thesis, Daejeon University, Daejeon, South Korea.

- Campbell, R. Warehouse Structure Fires. National Fire Protection Association NFPA, Research, Data and Analytics Division: Quincy, MA, USA, 2022.

- Nadile, L. The problem with big. National Fire Protection Association NFPA - 192 - Journal (March/April 2009), Quincy, MA, USA. 2009.

- Harrington, JL. Lessons learned from understanding warehouse fires. Fire Protection Engineering, Winter. 2006.

- Seo, H.W. A Study on the Standard Improvement of the Firestop System installed in the Penetration within the Fire Separating Element. 2020, Doctoral thesis, University of Seoul.

- Lee, E.C. Case Analysis of Warehouse Fire by Fire Dynamic Simulation. 2012, Master’s thesis. Chungbuk National University Graduate School of Industry.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). Standards for Automatic Fire Shutters and Fire Doors, Article 2(2). MOLIT Notification No. 2019-592, Sejong, Korea, 2019.

- Woo. Y.J. A Suggested Method for Performance Evaluation of Large Scale Fireproof Shutters. Journal of the Korea Society of Hazard Mitigation 2020, 20, 111–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN 15269-10: Extended Application of Test Results for Fire Resistance and/or Smoke Control for Door, Shutter and Openable Window Assemblies—Part 10: Fire Resistance for Steel Hinged and Pivoted Doorsets. BSI, London, UK, 2011.

- BS EN 15269-11: Extended Application of Test Results for Fire Resistance and/or Smoke Control for Door, Shutter and Openable Window Assemblies—Part 11: Fire Resistance for Rolling Shutters. BSI, London, UK, 2018.

- EN 1993-1-2: Eurocode 3: Design of Steel Structures—Part 1-2: General Rules—Structural Fire Design. CEN, Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

- Kim, S.Y.; Chu, D.S.; Lee, H.D.; Shin, K.J. Mechanical Properties of Structural Steel at Elevated Temperature. Journal of Korean Society of Steel Construction 2018, 30, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daw, T. A, Daw, A.M.(2020).”Stress and Deflection Analysis of Cantilever Mean by Numerically”. International Journal of Inovative Science and Research Technology. no. 5, Issue 4, pp.

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT). Standards of Structural Design for Buildings. MOLIT Notification No. 2016-317, Sejong, Korea, 2016.

- International cod council. International Building code 2015, USA, 2014.

- KS D 3568: Hot-rolled Structural Rectangular Hollow Sections of Non-alloy and Fine Grain Steels. Korean Agency for Technology and Standards, Eumseong, Korea, 2023.

- Lee, H.J.; Shon, J.G. Non-Integral AC Capacitor Voltage Calculation Method for Shunt Hybrid Active Power Filter. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 67968–67978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Park, K.J.; Cho, J.T.; Kim, J.Y.; Son, S.Y. Novel monitoring system for low-voltage DC distribution network using deep-learning-based disaggregation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 185266–185273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

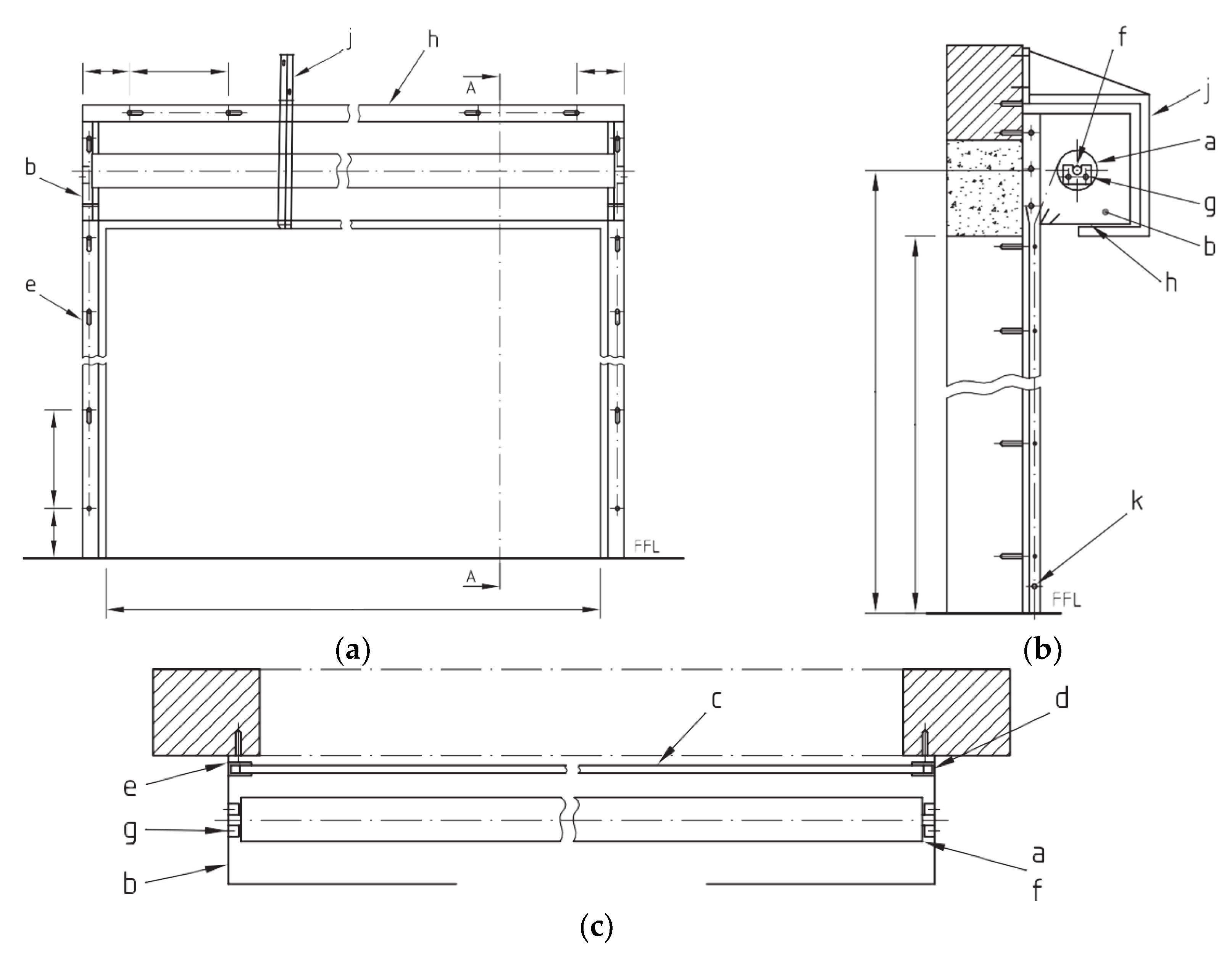

| Component Names | ||

|---|---|---|

| a : Barrel | b : End Plate/Bracket | c : Curtain |

| d : Guide g : Shaft Cup/Support k : Bottom rail |

e : Guide Fixing Angle h : Coil Casing/Hood |

f : Shaft j : Barrel Support Bracket |

| Reduction Factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Steel Temperature ɵa |

Linear Elastic Range kE, ɵ = Ea, ɵ / Ea |

Effective Yield Strength K y, ɵ = f y, ɵ / fy (f u, ɵ / f y, ɵ)* |

| 20 ℃ | 1.000 | 1.000 (1.25) |

| 100 ℃ | 1.000 | 1.000 (1.25) |

| 200 ℃ | 0.900 | 1.000 (1.25) |

| 300 ℃ | 0.800 | 1.000 (1.25) |

| 400 ℃ | 0.700 | 1.000 (1.00) |

| 500 ℃ | 0.600 | 0.780 (1.00) |

| 600 ℃ | 0.310 | 0.470 (1.00) |

| 700 ℃ | 0.130 | 0.230 (1.00) |

| 800 ℃ | 0.090 | 0.110 (1.00) |

| 900 ℃ | 0.0675 | 0.060 (1.00) |

| 1000 ℃ | 0.0450 | 0.040 (1.00) |

| 1100 ℃ | 0.0225 | 0.020 (1.00) |

| 1200 ℃ | 0.0000 | 0.000 (1.00) |

| Construction | Live Load | Snow or Wind Load | Dead + Live Load |

|---|---|---|---|

| Roof Members Supporting Plaster or Stucco Ceiling Supporting Non-Plaster Ceiling Not Supporting Ceiling Floor Members |

|||

| //360 //240 //180 |

//360 //240 //180 |

//240 //180 //120 |

|

| //360 | - | //240 | |

| Exterior Walls With Plaster or Stucco Finishes With Other Brittle Finishes With Flexible Finishes |

|||

| - - - |

//360 //240 //120 |

- - - |

|

| Interior Partition With Plaster or Stucco Finishes With Other Brittle Finishes With Flexible Finishes Farm Buildings Greenhouses |

|||

| //360 //240 //120 - - |

- - - - - |

- - - //180 //120 |

| Rectangular Hollow Section Specification Number | Side Length A×B, mm |

Thickness mm |

Area moment of Inertia Ix, Iy, cm4 |

Section Modulus Zx, Zy, cm3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 50×30 | 1.6 | 7.96, 6.3 | 3.18, 2.4 |

| 2 | 50×30 | 2.3 | 10.6, 4.7 | 4.25, 3.17 |

| 3 | 50×50 | 1.6 | 11.7 | 4.68 |

| 4 | 50×50 | 2.3 | 15.9 | 6.34 |

| 5 | 50×50 | 3.2 | 20.4 | 8.16 |

| 6 | 60×60 | 1.6 | 20.7 | 6.89 |

| 7 | 60×60 | 2.3 | 28.3 | 9.44 |

| 8 | 60×60 | 3.2 | 36.9 | 12.3 |

| 9 | 75×75 | 1.6 | 41.3 | 11 |

| 10 | 75×75 | 2.3 | 57.1 | 15.2 |

| 11 | 75×75 | 3.2 | 75.5 | 20.1 |

| 12 | 75×75 | 4.5 | 98.6 | 26.3 |

| 13 | 80×80 | 2.3 | 69.9 | 17.5 |

| 14 | 80×80 | 3.2 | 92.7 | 23.2 |

| 15 | 80×80 | 4.5 | 122 | 30.4 |

| 16 | 90×90 | 2.3 | 101 | 22.4 |

| 17 | 90×90 | 3.2 | 135 | 29.9 |

| 18 | 100×100 | 2.3 | 140 | 27.9 |

| 19 | 100×100 | 3.2 | 187 | 37.5 |

| 20 | 100×100 | 4 | 226 | 45.3 |

| 21 | 100×100 | 4.5 | 249 | 49.9 |

| 22 | 100×100 | 6 | 311 | 62.3 |

| 23 | 100×100 | 9 | 408 | 81.6 |

| 24 | 100×100 | 12 | 471 | 94.3 |

| 25 | 125×125 | 3.2 | 376 | 60.1 |

| 26 | 125×125 | 4.5 | 506 | 80.9 |

| 27 | 125×125 | 5 | 553 | 88.4 |

| 28 | 125×125 | 6 | 641 | 103 |

| 29 | 125×125 | 9 | 865 | 138 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).