1. Introduction

In this study we deal with topological properties of 2D polyhexes, i.e. surfaces of 3D and 4D objects tiled by sole hexagons. Like polyhedrons, which are solids covered by various kinds of polygons, the external surface of a 3D object is described by a graph with a given number of faces , vertices , edges respectively. Good examples are represented by the five regular polyhedrons which are tiled by identical regular faces like triangles (tetrahedron, octahedron, icosahedron), squares (cube), pentagons (dodecahedron). Graph G for the cube is made of faces, vertices (in which 3 faces touch each other) and edges (each of those touching 2 faces).

The graph shows a remarkable topological invariant called Euler Characteristic defined as:

(1)

Invariant (1) assumes the value for the cube and the other polyhedrons including the dodecahedron that, from the chemistry angle, represents the molecular structure of the smallest possible fullerene, the carbon molecule with vertices, pentagonal faces and leading again to . This value holds for all fullerenes (in the following the number of graph nodes will be labeled by or ) and for any graph drown on a closed surface topologically equivalent to the sphere (closed surfaces are surfaces without boundaries). Things drastically change for non-spherical surfaces whose Euler characteristics values are different from 2. Tori and Klein bottles both have the same Euler Characteristic

[

1,

2] despite their crucial differences, being tori (

) and Klein bottles (

) respectively

orientable (

) and

non-orientable (

). A non-orientable surface does not have a proper inside or outside volume. The best-known example is the Möbius strip (

). The famous Escher’s ant walking on the strip, after the first lap returns in the original position but with a mirror reversed orientation, two laps being in fact required for restoring both, initial position, and orientation. Möbius band has a boundary that “can be sewn up (in two diverse ways) to produce non-orientable surfaces (the Klein bottle and the projective plane) without boundary” [

2].

are truly fascinating structures derivable by closing in the parallel (cylindrical) way the boundaries of the Möbius strip, in the same way in which a rectangle gets transformed in a cylinder.

and

lattices both show Euler characteristics

[

1,

2] and

(2)

may be tiled by sole hexagons, a notable example of polyhex surfaces called toroidal and Klein bottle fullerenes adding the relevant constraint:

(3)

Euler, who first discovered in 1758 chirality

(1) and its universal properties for convex polyhedra [

2], was pleasantly “surprised” that no one before him noticed

role in classifying the topological behaviors of distinct types of closed surfaces.

Euler chirality is a

fundamental topological invariant for surfaces’ classification. In a recent original communication [

3], a novel implication rooted in the

common value has been established for Tori and Klein bottles.

The heuristic interpretation of that mathematical discovery sounds like this:

When the size of the cylindrical edge of the KB exceeds a

certain threshold, KB polyhex graphs show toroidal features, namely: i) KB

graphs become transitive, and ii) distance-based graph descriptors of both

graphs are equal. Within the symmetry region therefore, an observer walking on

the two surfaces along the edges is unable to distinguish between them: KB and

Tori are topologically symmetric and indistinguishable as the ultimate

consequence of common value.

As described in the next section, it is worth to remember that this relevant symmetry has been discovered [

3] for zig-zag KB graphs and it holds when the (integer) lengths of lattices’ edges respect the constraint:

(4)

where the zig-zag Möbius edges and the cylindrical edge have lengths

and

, respectively (see

Figure 1). In this paper, new topological features are presented for a deeper understanding of the mechanism including the connections between the two polyhexes outside the symmetry region. Lastly, we will introduce here a new phenomenon, we have named

enhanced-by-topology-expansion that is an original topological effect still rooted in the Toroidal / Klein-bottle symmetry.

2. Topological Features of Polyhex Tori and Klein Bottles

Just a short comment about the nomenclature. We aim to keep Deza’s and co-workers’ [

4] definition of fullerenes as “finite trivalent graphs made of pentagons and hexagons tiling four kinds of surfaces: sphere, torus, Klein bottle, and projective (elliptic) plane”. In the following we will therefore call torus and Klein bottle polyhex as

and Klein-bottle

zig-zag fullerenes with sizes

.

The number of pentagons is 12 for the usual ball-shaped C

n fullerenes, 6 for elliptic fullerenes, and

zero for toroidal

and Klein-bottle

zig-zag fullerenes. The present study aims to provide some more details about the deep topological connection between toroidal and Klein-bottle fullerenes that have been discovered in 2020 [

3]. This original result demonstrated that Klein Bottle may be “transformed” into Toroidal fullerenes for certain critical sizes, summarized herewith.

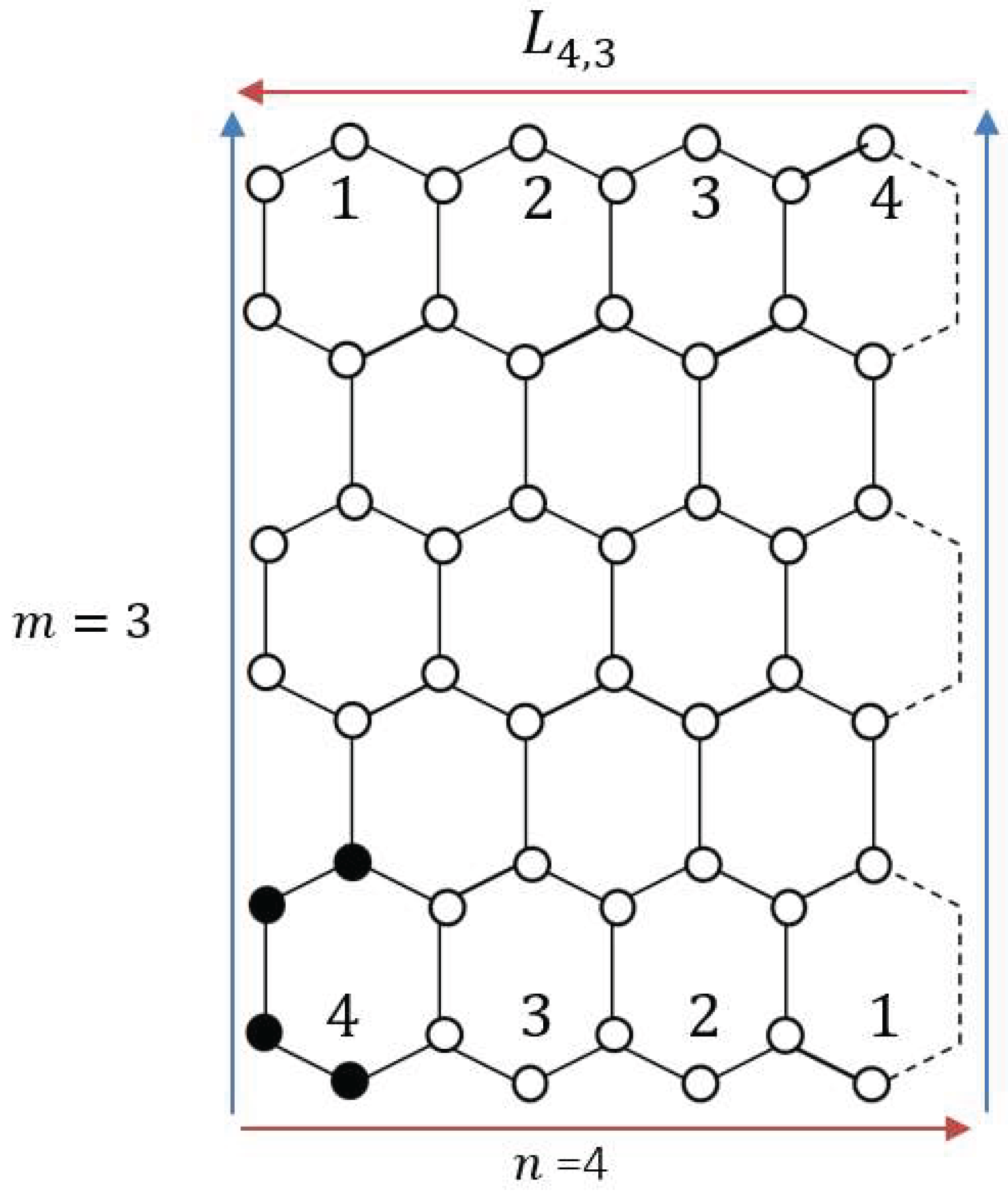

To make the visualization of this symmetry clear, let’s start from a standard hexagonal lattice

made by

cells along direction x (

the zig-zag edge) and

cells along y (

the armchair edge), naming x and y axis the Möbius and cylindrical axis, with length

respectively. Polyhex lattice with

hexagons in the

case considered in

Figure 1 as a useful example.

The unit cell has the “C” shape with 4 nodes (black circles); in such a way the honeycomb lattices with a total number of nodes , are easily composed just by translations of the unit cell. By closing both edges, the torus is built, with nodes and edges. It is now straightforward to check that toroidal graphs are transitive with all nodes showing the same coordination numbers set , the set of integers counting the vertices placed at distance from the starting node. indicates the graph diameter that is the longest chemical distance in the graph. Some obvious identities characterize the coordination numbers set, such as: and, for present fullerenes-like graphs (cubic graphs case). The open graph may be closed to form the torus as well as the Klein Bottle fullerenes .

We consider in this study zig-zag Klein Bottle fullerenes which are closed,

in the antiparallel way, along the x axis, as see the

example reported in

Figure 1. Along the y axis the

lattice is closed to form a cylinder as in the tori.

Let’s summarize here the main result reported in our previous study:

Proposition 1. Tori-Klein Bottles symmetry (Putz, Ori 2020 [3]). Coordination numbers for every node of and fullerenes are equal iff the lengths of Möbius and cylindrical edges obey to the condition .

Proposition 1 may be interpreted something like “when the cylindrical toroidal edge exceeds the Möbius one, the Klein Bottle graph behaves as a Torus”. This is the correct bit of heuristics beyond this interesting result which sheds light on the graph symmetry.

In other words, the two hexagonal systems are topologically symmetric, same set for every node, in the region of symmetry defined by condition (4). The existence of that specific size-threshold holds for any length of the zigzag edge. In fact, the topological symmetry does occur for the size of the cylindrical edge which equals or exceeds the threshold size :

(5)

Symmetry region (4) is therefore redefined as :

(6)

Inside the symmetrical region Eqs. (4,5,6), both Tori and zig-zag Klein Bottles fullerenes are topologically indistinguishable (Proposition 1 above). Therefore any “explorer” that, starting from a vertex

, walking along the graph edges till all the remaining

nodes are reached, will count exactly the same number of vertices

in any of the

coordination shell of vertex

(

) no matter of which type of fullerene, Torus

or Klein Bottle

, he is walking on. In the opinion of the authors this is a profound consequence of the

of value shared by the two polyhexes lattices. In our example in

Figure 1, Torus

or on the Klein Bottle

already belong to the symmetry region that for

, starts at

according to Eqs.(4,6). Both graphs are

transitive sharing moreover

the same coordination numbers {

}={3 6 9 11 11 6 1}. Heuristically, the symmetry holds for hexagonal systems where the “cylindrical” dimension

exceeds the length

of the zig-zag Möbius edge.

It’s worth noticing that, according to numerical

simulations conducted so far, Klein Bottles graphs are transitive in the

symmetry region only.

Two original relevant new properties featured by Klein Bottles fullerenes in the proximity of the symmetry region (6) are provided in the following paragraphs.

3. Distances Properties in Klein Bottles Fullerenes

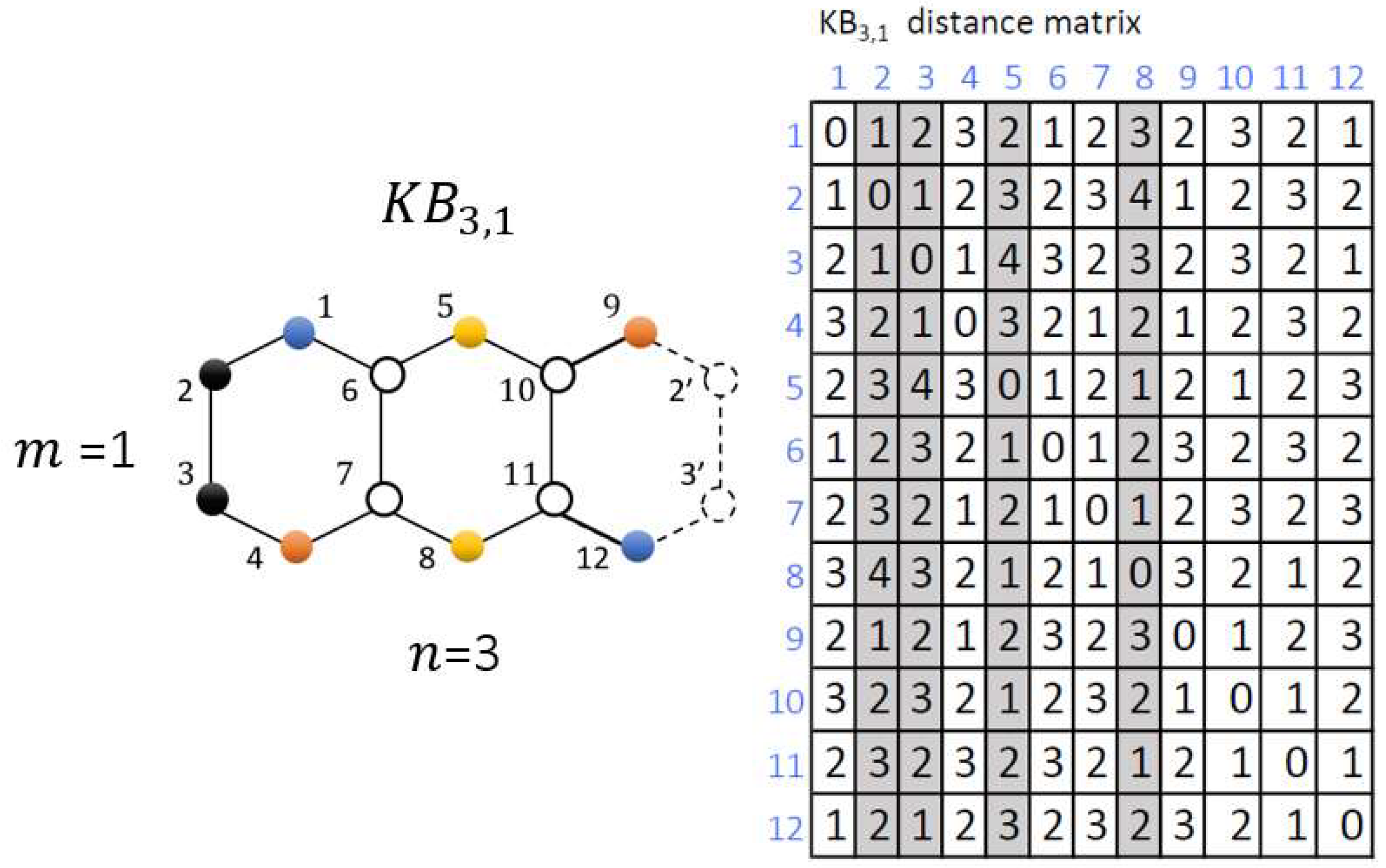

This section aims to provide more insights about the topological distances in Klein Bottles fullerenes

near the symmetry region (6). Numerical simulations evidence the presence of an interesting sort of residual symmetry (Proposition 2) outside the symmetry region conjectured to be valid for all polyhex

. Let’s consider, as a case study, Klein Bottle fullerenes of size just outside the symmetry region (6), namely

for

and so on. Focusing on the small

lattice, complete results are provided, see

Figure 2. Lattice has

nodes, closed along y in a cylindrical way by 2-2’ and 3-3’ bonds and with the Möbius twist along x to create 1-12 and 9-12 bonds. The first effect outside the symmetry region is that

graph loses the transitivity property.

The bonded pair (5,8), right in the middle of the graph, does not discriminate between cylindrical and Möbius closures, being this true for all odd length of edge x. These two nodes, together with other two cylindrical vertices 2 and 3, present coordination numbers } for and

=1,2,3,4. We call these

nodes

toroidal vertices, sinc e they have the same {

} sets of the nodes of the corresponding

torus. The total number of toroidal nodes

is twice the number

of toroidal nodes along the y edge, in our example

,

,

, see

Figure 2. Toroidal nodes have eccentricity

equal to graph diameter

, meaning that in the graph at least one node exists at distance

from the toroidal

vertices. For

value

indicates that in fact just one node stays at distance

from the toroidal vertices

and

obviously this node is also a toroidal node as reported by entries 4 the distance matrix in

Figure 2, where for example nodes 5 and 3 are at distance 4.

The remaining nodes define the so-called Möbius vertices set

whit reduced eccentricity

in respect to the toroidal nodes

. They have 3 nodes, two Möbius and one toroidal, in the most distant coordination shell

, see the number of entries 3 in the “white” columns of the distance matrix in

Figure 2.

Möbius vertices

have cardinality

. Back to our example

,

nodes have reduced eccentricity

, and are most of the nodes

(see

Figure 2). Lower eccentricity means that the Möbius vertices are deeply embedded in the systems.

Vertices

have coordination numbers

with

. Previous numerical studies on 1D Möbius hexagonal ribbons [

5] evidenced the same type of graph compression induced by one Möbius twist, therefore we are proposing here that:

The reduced eccentricity, with a compactification of the graph, is a constant feature of any non-orientable polyhex graph compared to its orientable counterpart (i.e. belts and Möbius belts; tori and Klein Bottles).

Table 1 summarizes distance properties for

hexagonal lattices whose basal features are:

i) Klein Bottles fullerenes lose the transitiveness they have inside the symmetry region;

ii)

nodes are now grouped in 2 classes (was 1 class in the symmetry region) with different cardinalities

,

(see

Table 1).

Other properties derive by topological transmission computation. This invariant in graph theory is in fact defined as the sum:

(7)

corresponding to the sum of entries in the

row (or column) of the distance matrix, converting the information contained in the string of integers

in an integer or semi-integer number. Quantity (7) is known by early studies [

6] to behave as a

polynomial where

is the length of the lattice edge. In our case D=2, the lattice is composed by

unit cells and

(

Table 1). The two classes of nodes composing

lattice in

Figure 2 have respectively

and

. It’s worth evidence here how the presence of

toroidal nodes is also true for Klein Bottles fullerenes

when

is an even integer. Exact results in

Table 1 are insensible to parity of integer size

, with

for polynomial exact interpolation.

Populations , in fullerenes scale for large graphs as:

(8a)

(8b)

Topological commonality between Tori and Klein Bottle produces an interesting remnant symmetry, based on the presence of toroidal nodes , present here as Proposition 2 arguably for the first time in literature.

Proposition 2. Tori-Klein Bottles remnant symmetry. Given a

graph outside the symmetry region , it still has toroidal nodes whose set are the same of the nodes of the same size Torus fullerene.

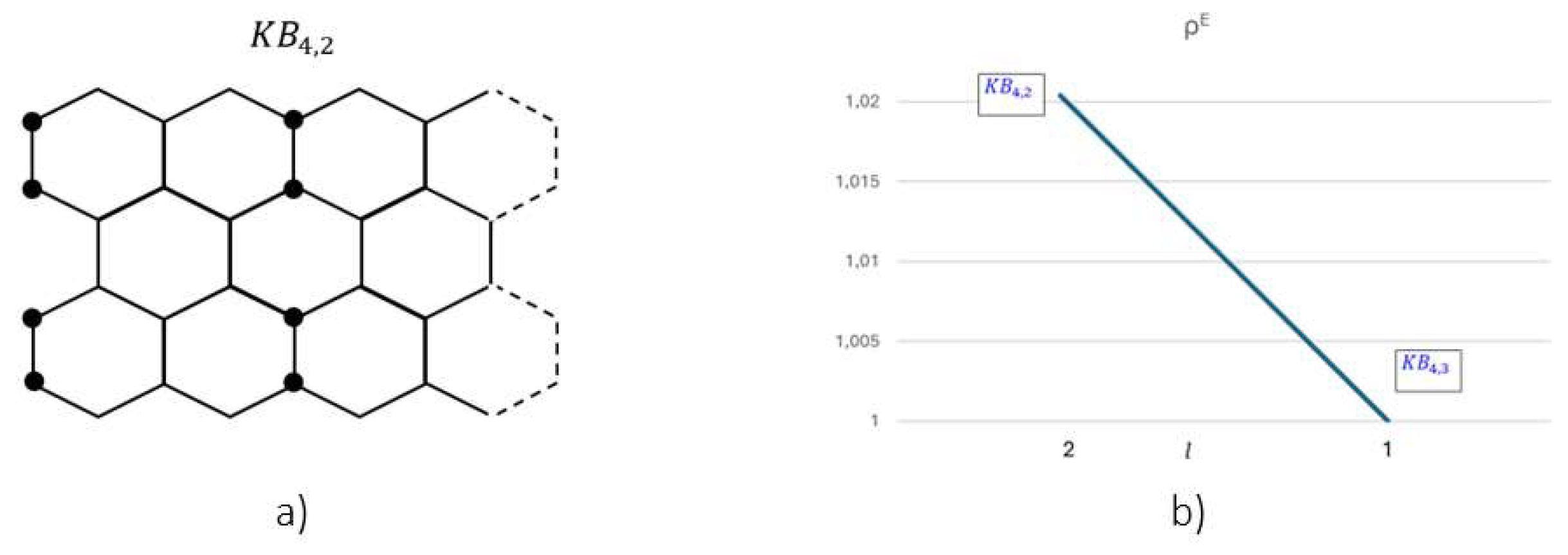

Numerical computations show that the

toroidal nodes are placed along two lines parallel to the cylindrical edge y, see

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 for odd and even

cases respectively.

4. Enhanced Expansion for Klein Bottle Fullerenes

We conclude this study by reporting an interesting topological effect observed in Klein Bottle fullerenes when they expand the size of the cylindrical edge by crossing the symmetry region boundary at the same time. This peculiar expansion effect driven by topology is summarized here for both graphs like in a dynamic evolution in time from time to .

At time we have and lattices that, for some “external” cause we are not discussing here, at will grow in their cylindrical size to create two expanded graphs and which are now just inside the symmetry region.

At time , the starting Klein Bottle fullerene lays just outside the symmetry region (6), and has Möbius nodes with eccentricity which is “one less” the eccentricity of the vertices of the same size Torus :

(9a)

At time , after the expansion of both systems along the cylindrical edge, the final graphs fall at in the symmetry region in which they become both transitive and indistinguishable with the same toroidal eccentricity value for all nodes:

(9b)

Our numerical simulations show that the new eccentricity on is “one more” the starting one for :

(9c)

Therefore, by combining relations (9), we see that from to we have a double increase of the eccentricity for the Möbius nodes:

(10)

reaching an interesting topological mechanism described in Proposition 3 herewith:

Proposition 3. Klein Bottles enhanced expansion. Klein Bottle fullerene expands twice the same-size Torus when the expanding cylindrical edge crosses the symmetry region threshold:

It is worth noticing that integer

in Proposition 3 represents the eccentricity of the

Möbius nodes which are the large majority - as described in Eq.(4) - in a Klein Bottle system outside the symmetry region. Based on this, Proposition 3 exactly holds for

nodes of the Klein Bottle system. To illustrate with some visual details these properties, let’s study

and structure which are just outside the symmetry region (6), see

Figure 3. On

at time

, the

Möbius nodes (

) have eccentricity

. The remaining toroidal nodes present eccentricity one-more . On the torus at time , all the vertices share the value (Proposition 2). At time , after the expansion along the cylindrical edge, all nodes of and share the same eccentricity . Therefore, for an observer the diameter of the torus just expanded by one, from to . On the contrary the observer over the expanding Klein Bottle universe will see that the eccentricity of the Möbius nodes passes from to . We may then observe that topology enhances the expansion of the Klein Bottle graphs.

We would like to complete this article by providing a topological description of the energy landscape involved in the passage of the symmetry threshold

(6). To achieve this goal, we will use the basic topological modeling methods (see a recent study [

5]) applied here to Tori and Klein bottles fullerenes, whose structures are described in terms of nodes in a chemical cubic and planar graph.

Despite this approximation, interesting theoretical conclusions may be derived concerning the chemical relative stability of such fullerenes when topological graph descriptors such as topological roundness is taken as topological potential governing the evolution of the nano-systems.

For any graph

G, its topological roundness

is defined on the transmission values set (7) of all graph nodes

as [

6,

7]:

with , (11)

By definition, with the lower limit reached in highly symmetric systems. Low values signal high topological roundness. Invariant (11) depends on node-to-node interactions at every distance in G, this derives from transmission sum (7), and it makes possible an effective and elegant scheme to sieve stable graph configurations by identifying the topological potential energy of the system with itself:

(12)

Potential is subject to the usual minimum energy principle and it varies by changing graph topology. In this case we are interested in changing vertices number N in the parallel and antiparallel periodic conditions in direction x. Readers are encouraged to search for more information about many other topological modeling applications in literature, articles [5-8] and more. Let’s now consider and fullerenes with horizontal and vertical sizes. Just outside symmetry region , the topological potential for is easily computed: . Torus shows an increased topological efficiency (i.e. lower When the vertical size of the system is increased , the two structures are both transitive and topologically symmetric. The decrease in topological potential , reported in Figure 4a, does signal the tendency of the Klein bottle system to become symmetric with the toroidal one, with a relative gain in the topological potential of about 2%.

Present results confirm the ability of topological methods to trace complex patterns to describe complex systems time evolution, confirming the power of topological modeling, an effective support to more sophisticated time-consuming computational methods, like ab-initio simulations.

5. Conclusions and Outlook Over Future Steps

This study provided new insights on the symmetry connecting Toroidal and zig-zag Klein-bottle fullerenes. The presence of residual toroidal nodes in the graphs of the Klein-bottle fullerenes outside the region of symmetry has been introduced here for the first time and will be subject of further investigations aiming to determine the conditions for synthesizing actual chemical structures with Klein-bottle topology. To this extent, the discovery, reported here, of a double expansion changing the Klein-bottle structure may play in facilitating the formation of non-orientable chemical nano systems.

Taking a more fundamental cut [

3], present topological interplay between orientable and non-orientable structures represents a powerful tool for the geometrization of the complexity space (of the cosmos, nature, and nano-materials) and is the optimal candidate for nano-topo unification of the quantum and relativity theories, to simulate space–time coupled (entangled) dynamics.

References

- Weeks, J.R. The Shape of Space; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey, L. C. Topology of surfaces; Springer Science & Business Media: 2012.

- Putz, M.V.; Ori, O. Topological symmetry transition between toroidal and Klein bottle graphenic systems. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deza, M.; Fowler, P.W.; Rassat, A.; Rogers, K.M. Fullerenes as tilings of surfaces. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2000, 40, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bultheel, A.; Ori, O. Topological modeling of 1-Pentagon carbon nanocones – topological efficiency and magic sizes. Fullerenes, Nanotubes and Carbon Nanostructures 2018, 26, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cataldo, F.; Ori, O.; Iglesias-Groth, S. Topological lattice descriptors of graphene sheets with fullerene-like nanostructures. Mol. Simul. 2010, 36, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putz, M.V.; De Corato, M.; Benedek, G.; Sedlar, J.; Graovac, A.; Ori, O. Topological invariants of Moebius-like graphenic nanostructures. In Topological Modelling of Nanostructures and Extended Systems; Ashrafi, A.R., Cataldo, F., Iranmanesh, A., Ori, O., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; pp. 229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Cataldo, F.; Ori, O.; Graovac, A. Graphene topological modifications. International Journal of Chemical Modeling reprinted in : M. V. Putz (Ed.), Advances in Chemical Modeling (Chemistry Research and Applications, Vol. 3) Nova, New York, 2013, pp. 241–26. 2011, 3, 45–63. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

N=48 nodes cubic lattice is represented. The unit cell, black circles, is copied times along x the Möbius axis and times in y, the cylindrical axis. Once it is closed on both directions, the torus is obtained, whose nodes show coordination numbers {}={3 6 9 11 11 6 1}. By sewing same-label nodes, one obtains instead of the zig-zag Klein Bottle fullerene graph , still transitive and with the same {bk} for each vertex. This system lays inside symmetry region with threshold and .

Figure 1.

N=48 nodes cubic lattice is represented. The unit cell, black circles, is copied times along x the Möbius axis and times in y, the cylindrical axis. Once it is closed on both directions, the torus is obtained, whose nodes show coordination numbers {}={3 6 9 11 11 6 1}. By sewing same-label nodes, one obtains instead of the zig-zag Klein Bottle fullerene graph , still transitive and with the same {bk} for each vertex. This system lays inside symmetry region with threshold and .

Figure 2.

lattice, N=12 nodes, closes y edge like in a torus by 2-2’ and 3-3’ bonds and Möbius-way the vertices along the zig-zag edge x, bonds 1-12, 9-4. Bond 5-8 also closes toroidal-like: these 4 toroidal nodes , in gray in the distance matrix, have eccentricity 4 and coordination numbers {}={3 4 3 1}. Möbius nodes instead show reduced eccentricity 3 with .

Figure 2.

lattice, N=12 nodes, closes y edge like in a torus by 2-2’ and 3-3’ bonds and Möbius-way the vertices along the zig-zag edge x, bonds 1-12, 9-4. Bond 5-8 also closes toroidal-like: these 4 toroidal nodes , in gray in the distance matrix, have eccentricity 4 and coordination numbers {}={3 4 3 1}. Möbius nodes instead show reduced eccentricity 3 with .

Figure 3.

a) closed lattice with , N=32 nodes in total of which toroidal nodes (black circles) positioned along two vertical lines. This holds for lattices with odd and even size . Toroidal and Möbius nodes have respectively eccentricities , and transmissions , ; b) Topological efficiency for fullerenes with . The passage to the symmetry region, , implies the fullerene to behave like the same size torus, a more efficient topological system.

Figure 3.

a) closed lattice with , N=32 nodes in total of which toroidal nodes (black circles) positioned along two vertical lines. This holds for lattices with odd and even size . Toroidal and Möbius nodes have respectively eccentricities , and transmissions , ; b) Topological efficiency for fullerenes with . The passage to the symmetry region, , implies the fullerene to behave like the same size torus, a more efficient topological system.

Table 1.

Distance-based topological invariants for the fullerenes in function of zig-zag edge length . Number of nodes , toroidal and Möbius nodes , and their eccentricities , and transmissions , are expressed in term of exact polynomials in .

Table 1.

Distance-based topological invariants for the fullerenes in function of zig-zag edge length . Number of nodes , toroidal and Möbius nodes , and their eccentricities , and transmissions , are expressed in term of exact polynomials in .

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).