1. Introduction

A

fullerene is a 2-connected cubic planar graph whose faces are only

length and 6-length. Došlić showed that all

fullerenes only exist for

, 3, 4 or 5 and are 1-extendable [

1]. A

fullerene is the usual fullerene as the molecular graph of a sphere carbon fullerene. A

fullerene is the molecular graph of a boron-nitrogen fullerene. The structural properties, such as connectivity, extendability, resonance, anti-Kekulé number, are very useful for studying the number of perfect matchings in a graph[

2,

3]. And the number of perfect matchings is closely related to the stability of molecular graphs[

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. Therefore, many articles have studied the structural properties of graphs in both mathematics and chemistry [

9,

10,

11]. Fullerene graphs are bicritical, cyclically 5-edge-connected, 2-extendable and 1-resonant [

12,

13,

14,

15]; Boron-nitrogen fullerene graphs are bipartite, 3-connected, 1-extendable, 2-resonant, and have the forcing number at least two [

16,

17]; A

fullerene is 1-extendable, 1-resonant and has the connectivity 2 or 3 [

18,

19]. This paper is mainly concerned with the structural properties of

fullerenes.

A fullerene F is a cubic planar graph such that every face is either length or length. A graph with two vertices and n parallel edges joining them is denoted by . The smallest fullerene is . A is a graph that can be embedded in the plane such that its edges intersect only at their ends. Any such embedding divides the plane into connected regions called . Two different faces are if their boundaries have an edge in common. A face is said to be the vertices and edges in its boundary, and vice versa. An edge is said to be the ends of the edge, and vice versa. Two vertices which are incident with a common edge are , and two distinct adjacent vertices are . If S is a set of vertices in a graph F, the set of all neighbours of the vertices in S is denoted by , and denotes the number of neighbours of S.

Let F be a fullerene graph with vertex-set and edge-set . We denote the number of vertices and edges in F by and . For , we let be the subgraph of F obtained from F by removing the elements in H. A of F is a set of disjoint edges M of F. A perfect matching of F is a matching M that covers all vertices of F. A perfect matching of a graph coincides with a Kekulé structure of some molecular graph in organic chemistry. A set of disjoint even faces of a graph F is a if F has a perfect matching M such that the boundary of each face in is an alternating cycle. F is said to be k-resonant () if any i () disjoint even faces of F form a resonant pattern. Moreover, F is called () if any matching of n edges is contained in a perfect matching of F. F is if F contains an edge and contains a perfect matching, for every pair of distinct vertices . In this paper, we show that every fullerene is 1-extendable, 1-resonant but not 2-extendable, bicritical.

The anti-Kekulé set of a fullerene F with perfect matchings is an edge set such that is connected and has no perfect matchings. The anti-Kekulé number of F, denoted by , is the cardinality of a smallest anti-Kekulé set of F. It is NP-complete to find the smallest anti-Kekulé set of a graph. Moreover, it has been shown that the anti-Kekulé set of a graph significantly affects the whole molecule structure by the valence bond theory. We have known the , , and fullerenes have the anti-Kekulé numbers 4, 4 and 3 respectively. In this paper, We show that every fullerene F has the anti-Kekulé number 4 with .

2. Main results

An edge-cut of F is a subset of edges such that is disconnected. An is an edge-cut with k edges. The of F, denoted by , is equal to the minimum cardinality of edge-cuts. F is if F cannot be separated into at least two components by removing less than k edges.

Lemma 1. The fullerene F has edge-connectivity 2, where .

Proof. Since every edge of F is incident with a 2-length face or a 6-length face, there is no cut edge in F. Therefore, F is 2-edge-connected. For one 2-length face C in F, denoted by . Then either or the two edges incident with x and y respectively other than form an 2-edge-cut of F. Therefore, , where . □

We call an edge e is a subgraph H if .

Lemma 2. Every 2-edge-cut of a fullerene isolates a 2-length face.

Proof. Let

F be a

fullerene. If

, then

, and the conclusion holds as

F has no 2-edge-cut. So next we suppose

. By Lemma 1,

F has an 2-edge-cut. Let

be an 2-edge-cut whose deletion separates

F into two components,

,

. Then

E is a matching of

F as

F is 3-regular and has edge-connectivity 2. Let every edge

has one endpoint, say

, on

, the other endpoint, say

, on

,

. Suppose the outer face of

is exactly the outer face of

F, thus

lies in some inner face of

. Then there are two hexagons, denoted by

,

, such that both

and

are incident with

,

,

,

. If one of

and

contains a cut edge, without losing generality, assume that

contains a cut edge

, then

has two connected components, say

,

. Then both

and

cannot be incident to the same component

(

), otherwise, there exists a cut edge

e in

F, a contradiction. Then

,

. That is, all of

,

and

are 2-length faces and we get a

fullerene with six vertices, thus the conclusion holds. If both

and

contain cut edges, then there is a face with length more than 6, a contradiction. If neither

nor

has a cut edge, then

and

are 2-edge-connected, and in each of them there is only one face that is not 2-length or 6-length, and we denote these two boundaries of the exceptional faces by

and

, respectively. Let

,

, and

be the number of vertices, edges and faces in

, respectively. Let

be the length of

, and

,

be the number of 2-length faces, 6-length faces in

, respectively. By Euler’s formula and the structure of

, it follows that

By (

1), we obtain that

Since

F has no face with length more than 6, the two faces

each has at most two additional vertices on

. Hence

. By (

2), we can get

. If

, we have

, which means that

is a 2-length face, thus the conclusion holds. If

, then

and there are no additional vertices on

, which implies that

is a 2-length face, thus the conclusion holds. Therefore, every 2-edge-cut of a

fullerene isolates a 2-length face.

□

In [

1], Došlić proved that the

fullerene is 1-extendable for

. In fact, we may observe that the conclusions remain valid for

.

Lemma 3 ([

1]).

Let F be a fullerene graph. Then F is 1-extendable.

The resonance of faces of a plane bipartite graph is closely related to 1-extendable property. It was revealed that every face (including the infinite one) of a plane bipartite graph

G is resonant if and only if

G is 1-extendable [

20]. Combing with Lemma 3, we can know every

fullerene is 1-resonant.

Corollary 1. Every fullerene is 1-resonant.

Moreover, we can know no fullerene is 2-extendable.

Theorem 1. No fullerene is 2-extendable.

Proof. Let F be a fullerene graph. Let f be a 2-length face of F with the boundary . By the definition of extendability, we know that . Then there exist two vertices of F which are different from such that and . Since the four vertices must be contained in the same hexagon of F, there is a vertex , of F such that . Obviously, is a matching and cannot be contained in a perfect matching of F. Thus no fullerene is 2-extendable.

□

Similarly, we can show no fullerene is bicritical.

Theorem 2. No fullerene is bicritical.

Proof. Let F be a fullerene graph. Let f be a 2-length face of F with the boundary . When , then has no perfect matchings. When , then there exists a vertex u of F which is different from such that . Then has a single vertex as a component. So has no perfect matchings. That is, F is not bicritical.

□

Theorem 3 (Tutte’s Theorem [

21]).

A graph G has a perfect matching if and only if for any , where is the number of odd components of .

Theorem 4 (Hall’s Theorem [

21]).

Let F be a bipartite graph with bipartition W and B. Then F has a perfect matching if and only if and for any , holds.

For the connected cubic simple bipartite graph, we can know its anti-Kekulé number is 4 [

22].

Theorem 5 ([

22]).

If G is a connected cubic simple bipartite graph, then .

The above result can be used to determine the anti-Kekulé numbers of some interesting graphs, such as,

fullerenes [

22], toroidal fullerenes [

22] etc. Theorem 5 is also valid for

fullerene when

.

Theorem 6. Let F be a fullerene graph with . Then .

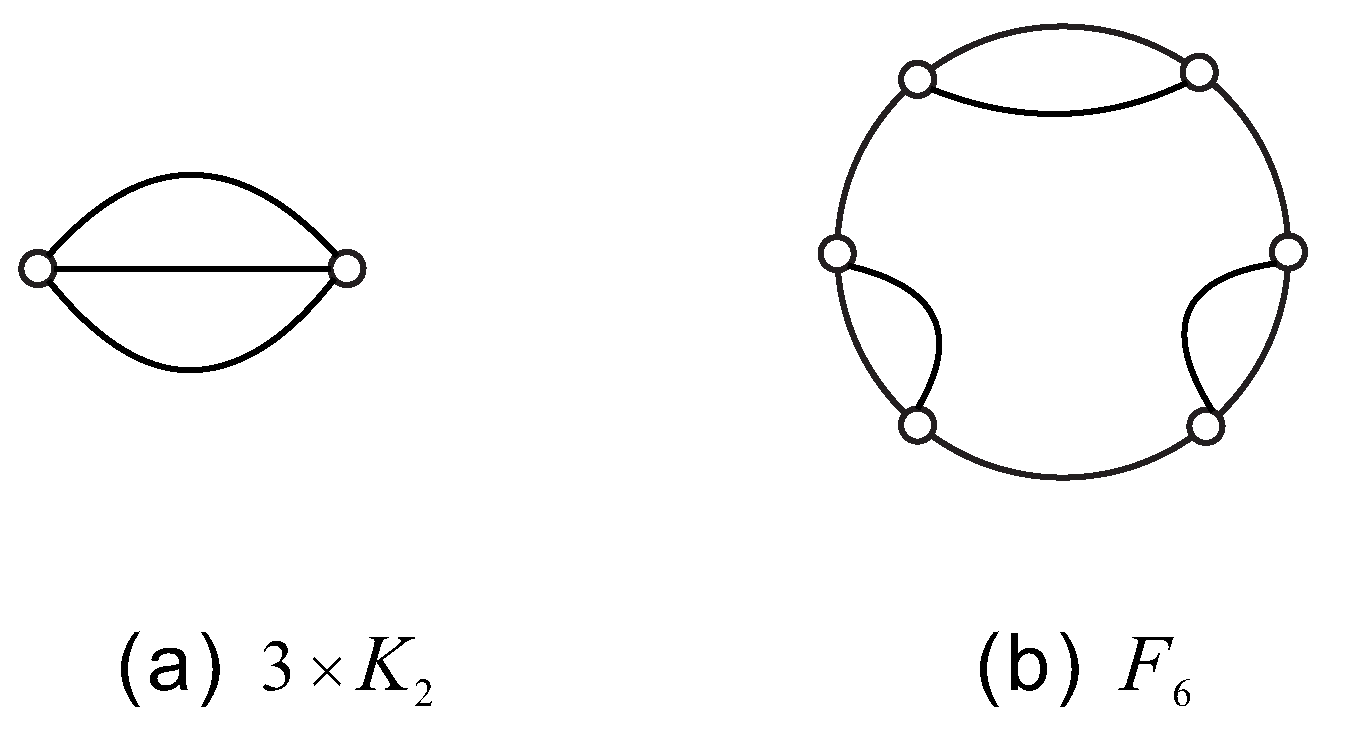

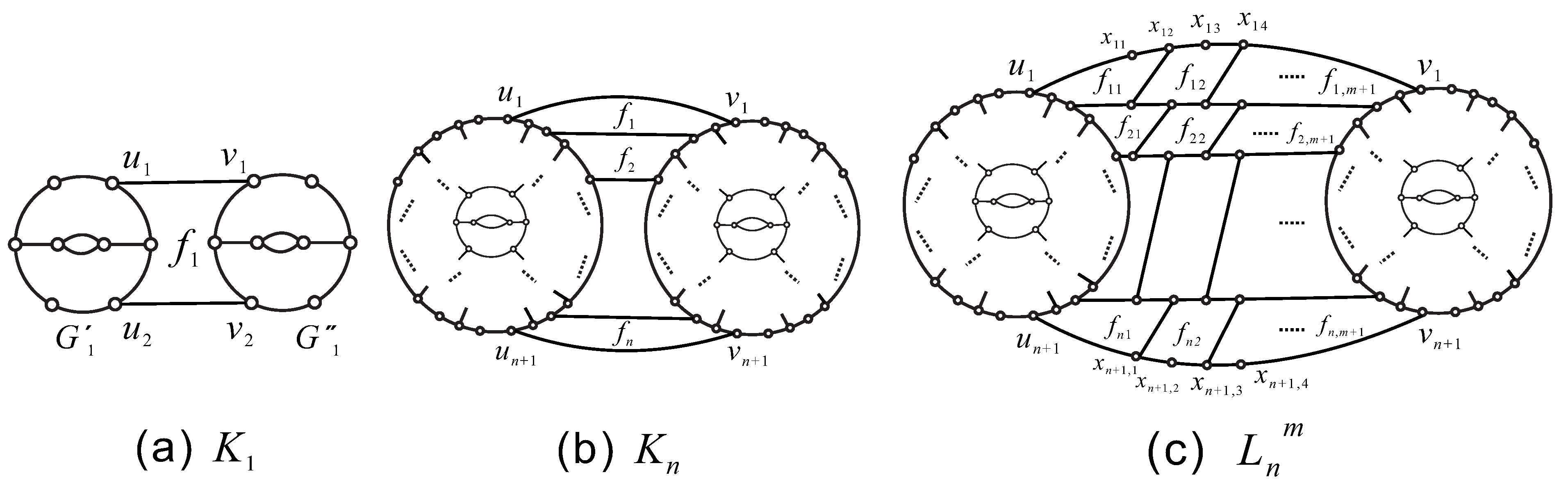

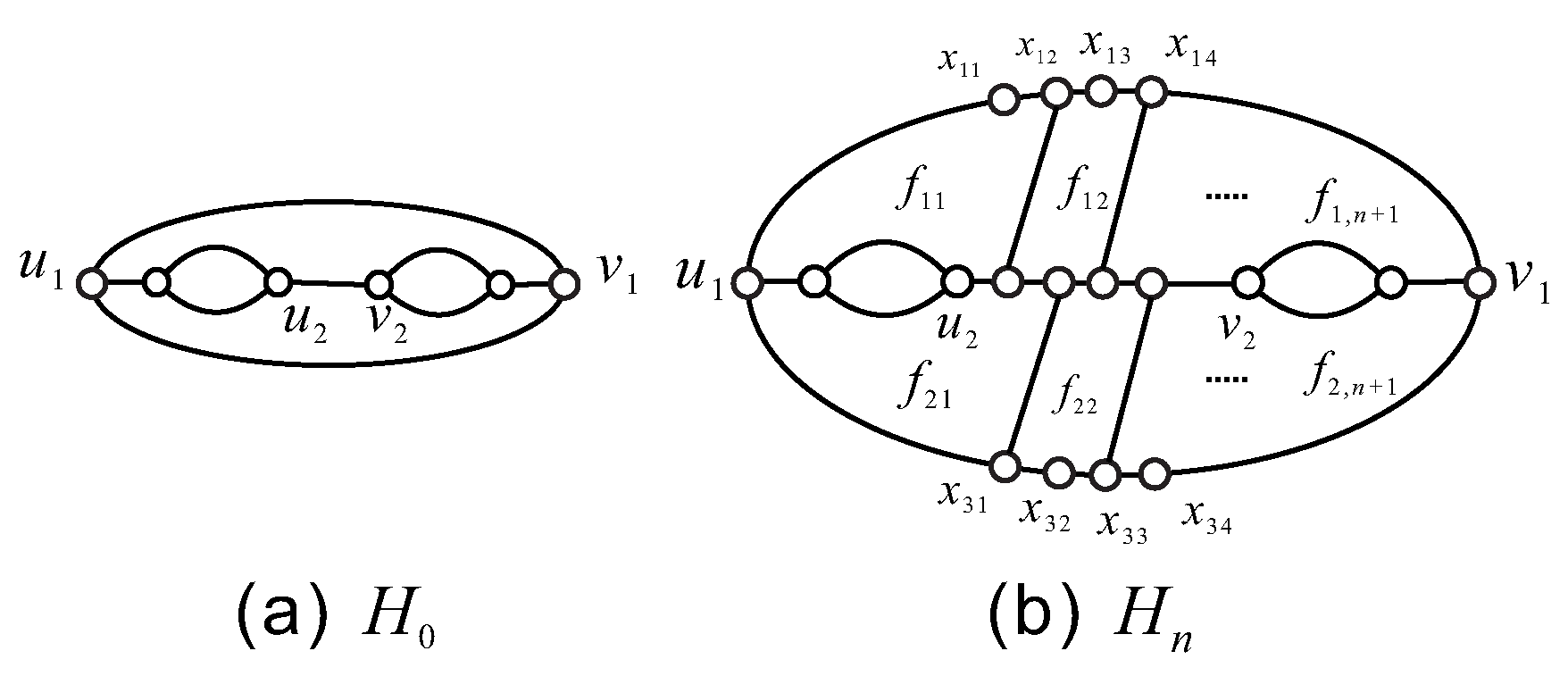

Proof. Let

F be a

fullerene. For any vertex

u in

F, if

, then

(see

Figure 1(a) the graph

). For any vertex

u in

F, if

, then

(see

Figure 1(b) the graph

). We can easily know that both

and

cannot exist anti-Kekulé set. On the other hand, if we let

n and

be the number of vertices and the hexagons of

F, respectively, then by the Euler’s formula and the formula of degree sum, we can get

. Thus if

, then

and

. If

, then

, which is impossible as every hexagonal face must contain six vertices. If

, then

and

(see

Figure 1(b) the graph

). Therefore, when

, there is no anti-Kekulé set in

F.

Next, we discuss the anti-Kekulé number of F with . Then there is a vertex u in F and . Let x, y, z be the three neighbors of u. Let and be two edges incident with x other than , and let and be two edges incident with y other than . Since every face of F is 2-length or 6-length and F is 2-edge-connected, the four edges are pairwise different. We claim that is an anti-Kekulé set. It is obvious that has no perfect matchings as the two vertices x, y cannot be contained in the same perfect matching. If is no connected, then we obtain a cut edge in F, contradicting Lemma 1. Then we find an anti-Kekulé set of size 4 and so .

In the following, we show . Let A be an anti-Kekulé set of size . Then is connected and has no perfect matchings. According to Theorem 3, there exists such that . If we choose such an S with the maximum size, then has no even components. On the contrary, suppose that has an even component H. For any vertex , . Let , then , which is a contradiction to the choice of S.

Since is even, then by parity. For any edge , adding e to will connect at most two odd components, then . Since A is the smallest anti-Kekulé set of F, then has a perfect matching for any edge . Hence, by Theorem 3, for the above subset S, . Therefore, . We obtain , and the edge e connects exactly two components of .

Let

be the odd components of

, where

. For

, let

denote the number of the set of edges with one end in

and the other end in

. Denote the number of edges between

S and the odd components by

N. Since

F is cubic,

S sends out at most

to

N. In addition,

sends out exactly

edges to

N. Hence

Because

F is 2-edge-connected,

for every

i. On the other hand, since

, which implies that

and

are of the same parity. Every

sends odd number edges, hence

. Substituting it into (

3), we have

the above inequality gives

.

We find that the anti-Kekulé number of

F is either 3 or 4. Suppose by the contrary that

. Then there exists an anti-Kekulé set

of cardinality three in

F, such that

is connected and has no perfect matchings. Assume

W and

B are the bipartition of

F. By Hall’s theorem, there exists

such that

where

means

in

. Moreover, for

, since

A is the smallest anti-Kekulé set,

has a perfect matching. Immediately by Theorem 4, for the above subset

U,

for

and 3, where

means

in

. In addition, the neighbors of

U will be increased by at most one if we add an edge

to

. Hence

Combining inequalities (

4), (

5) and (

6), we have

, and

is incident with the vertices of

U and

in

. Thus the edges going out from

either goes into

A or goes into the edges going out from

. Then the number of edges between

U and

is

. Since

,

, that is, there is no edge between

and

in

. As a result,

A is an edge-cut, which is a contradiction to the definition of anti-Kekulé set.

□

In [

23], Grünbaum and Motzkin showed that (5,6)-fullerene and (4,6)-fullerene having

n hexagonal faces exist for every non-negative integer

n satisfying

, and gave a similar result for (3,6)-fullerene. Therefore, we consider whether (2,6)-fullerene having

n hexagonal faces also exists for any

n. We tried to give a positive answer to this question, but we found that the conclusion seems quite elusive. Therefore, in this part, we mainly prove that there exists a

fullerene

F having

hexagonal faces where

is related to the two parameters

n,

m.

Let F be a fullerene. A H of F is a subgraph of F consisting of a cycle together with its interior and every inner face of H is also a face of F. We define as the of the exterior face of H. A face f of F is a of H if f is not a face of H and f has at least one edge in common with H. A path of length k (the number of edges) is called a k-. Denote by the number of hexagons of H.

Proposition 1. In all the (2,6)-fullerenes, there exists a fragment, say , such that , .

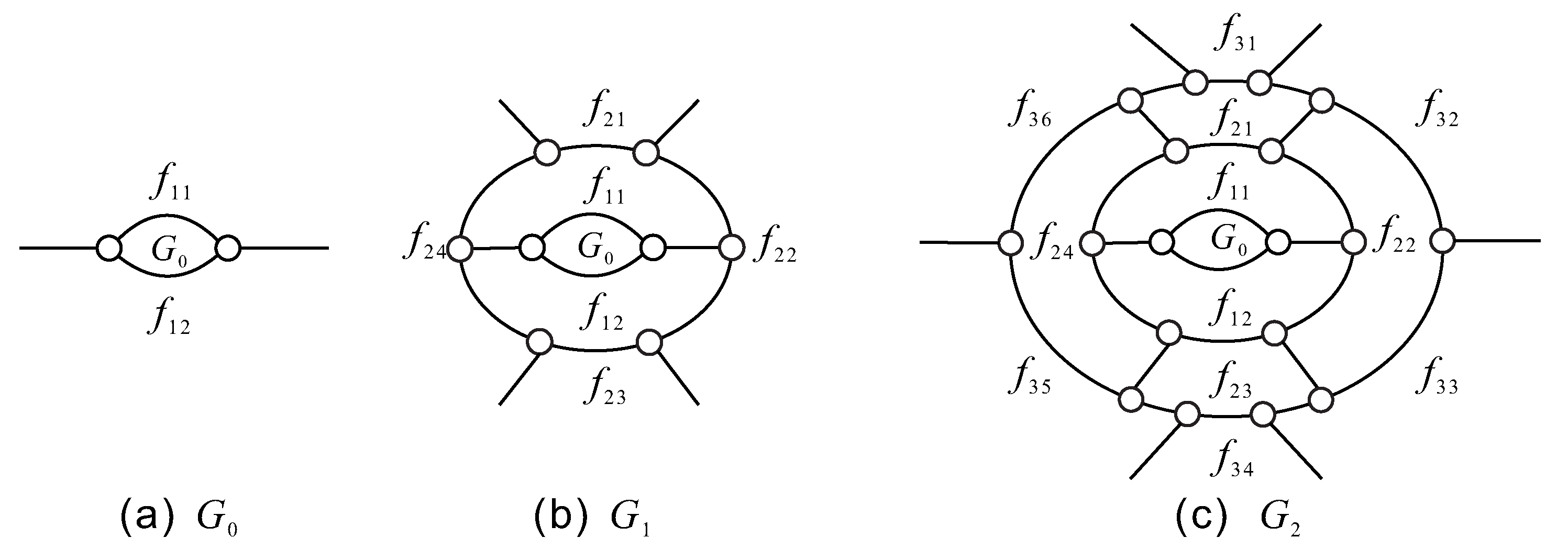

Proof. Let

be a 2-length face and

be two neighboring faces of

(see

Figure 2(a)). Then

. Suppose that

,

are hexagons. Set

, suppose both

and

are inner faces of

and let

be four neighboring faces of

along the clockwise direction such that

is incident with the two consecutive 2-degree vertices on

(see

Figure 2(b)). Then

. Suppose that

are hexagons, pairwise different, and intersecting if and only if

,

are intersecting at only one edge for

,

. Set

. Suppose

are the inner faces of

and let

be six neighboring faces of

along the clockwise direction such that

is incident with the two consecutive 2-degree vertices on

(see

Figure 2(c)). Then

.

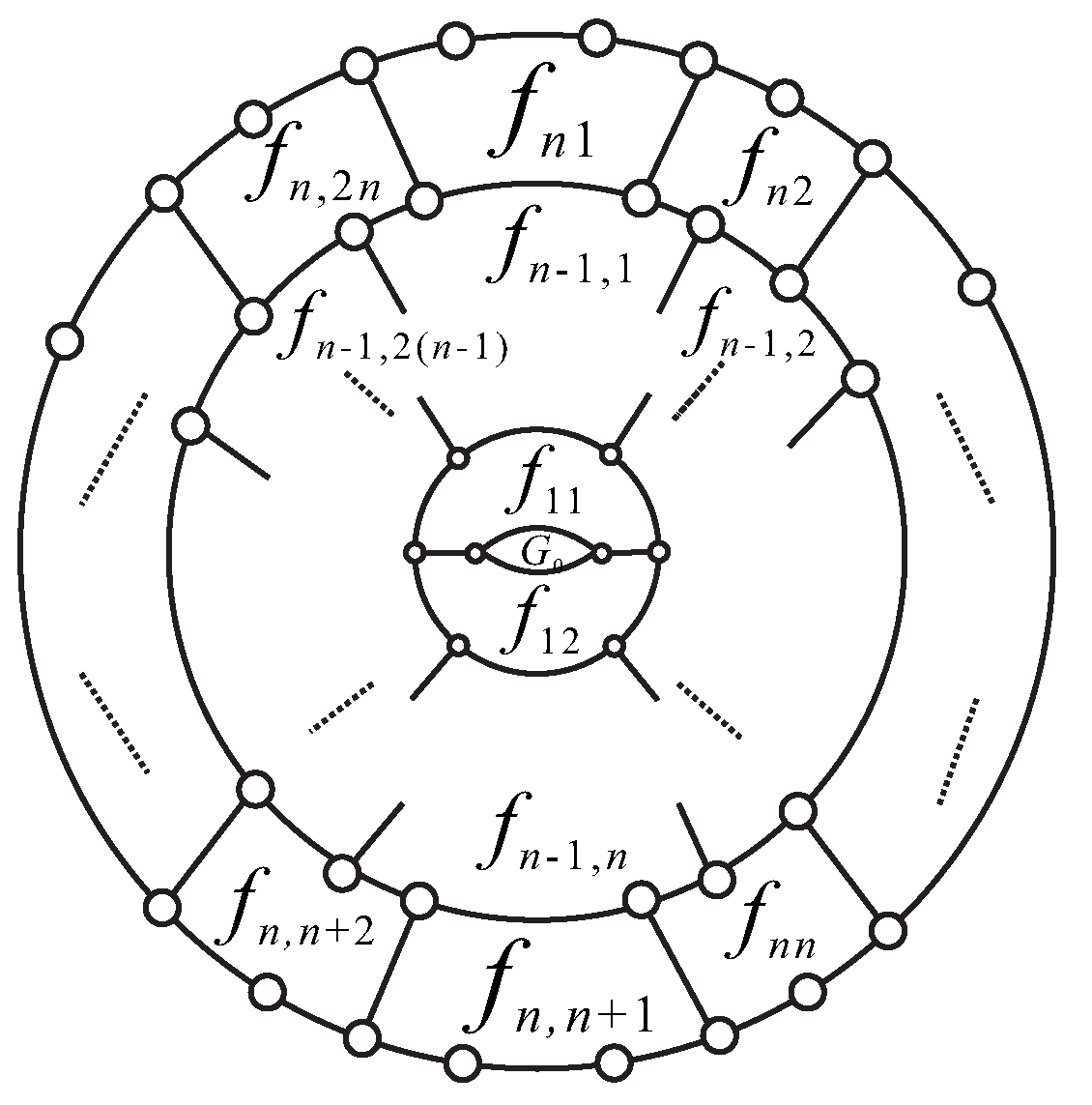

Suppose that the proposition holds for any integer less than

n, where

. According to the induction hypothesis,

and

be

neighboring faces of

along the clockwise direction such that

is incident with the two consecutive 2-degree vertices on

. Suppose that

are hexagons, pairwise different, and intersecting if and only if

,

are intersecting at only one edge for

,

. Set

. Suppose

are all inner faces of

(see

Figure 3). Then

,

.

□

Proposition 2. In all the (2,6)-fullerenes, there exists a fragment, say , such that , .

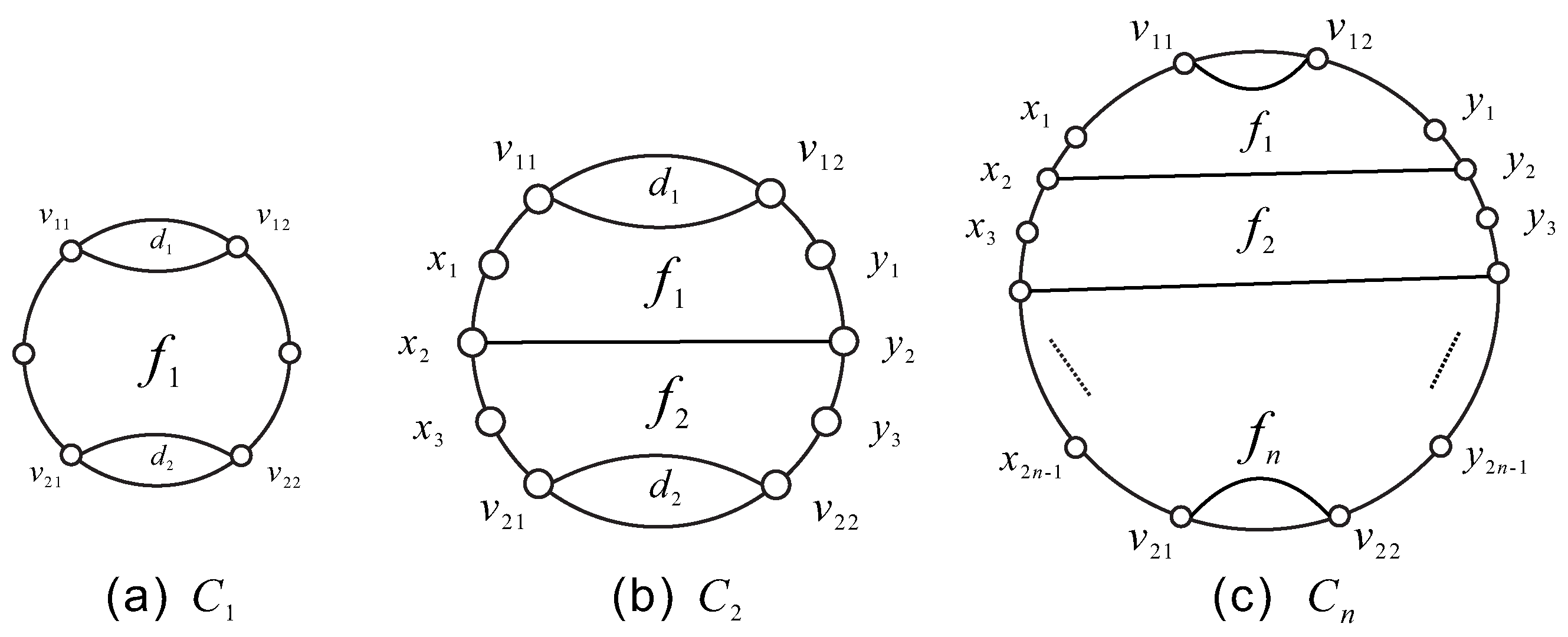

Proof. Let

be a

, then

. Let

and

be two 2-length faces. Its boundary

is labelled

,

(

). Let

be a path that connects two vertices

,

(

) and

. If both

,

are 2-paths, then as

F is 2-connected, there is a hexagon, say

, such that

contains the paths

,

and the edges

,

. Set

, without lose of generality, suppose

is the inner face of

(see

Figure 4(a)). Thus

. If both

,

are 4-paths, then all of whose internal vertices are denoted by

and

, respectively, such that

,

. Let

, then there are 2 hexagons, denoted by

, such that

,

. Set

, also suppose

are two inner faces of

(see

Figure 4(b)), then

. Suppose

,

are

-paths,

. Let

and

. Suppose that

(

), then there are

n hexagons between

and

, denoted by

. Set

such that

are the inner faces of

(see

Figure 4(c)). Therefore,

is a fragment and

,

. Thus there exists a fragment

such that

,

.

□

Proposition 3. In all the (2,6)-fullerenes, there exists a fragment, say , such that , , .

Proof. Let

,

be two fragments as indicated in

Figure 3. By Proposition 1, we know that

and

both have

hexagons. Suppose

n is a positive integer. Since there are

2-degree vertices on

, we can record them clockwise as

such that

and

are adjacent. Similarly,

2-degree vertices on

are denoted by

along the anticlockwise direction of

such that

and

are adjacent. For

and

. Let

, then

and

are contained in the hexagon, say

. Set

(see

Figure 5(a)), then

. For

and

. Let

,

, then

and

are contained in the hexagon, say

,

. Set

, suppose all of

are the inner faces of

(see

Figure 5(b), the embedding of

), then

.

Next, we construct the fragment

from

as follows. We replace each edge

by a path

such that

,

,

. Suppose that

be the edges of

F,

. Therefore, there are

hexagons between

and

, denoted by

,

. Set

,

(see

Figure 5(c), the embedding of

). Therefore,

is a fragment and

,

,

.

□

Proposition 4. In all the (2,6)-fullerenes, there exists a fragment, say , such that , .

Proof. Let

be the

-fullerene with six vertices. Without lose of generality, suppose the exterior face of

is a 2-length face with the boundary

, and the remaining two 2-length faces are connected by an edge

(see

Figure 6(a) the embedding of

and the labelling of

). Next, we construct the fragment

from

as follows: we replace the two parallel edges

and one edge

by two paths

,

and one path

such that

,

, and

,

. Suppose that

be the edges of

F,

. We construct

hexagons between

and

, denoted by

,

. Set

such that

are the inner faces of

,

(see

Figure 6(b)). Therefore,

is a fragment and

,

. Thus there exists a fragment

such that

,

.

□

By Propositions 1–4, we can find a fullerene F having hexagonal faces which related to the parameters n, m.

Theorem 7. There exists a fullerene F such that , .

Proof. Let

be a fragment of

F as shown in

Figure 3. Its boundary

is labelled

along the clockwise direction, where

and

are two consecutive 2-degree vertices. Let

be a fragment of

F as shown in

Figure 4(c). Its boundary

is labelled

along the clockwise direction, where

and

are two consecutive 3-degree vertices. Next assume the graphs

and

each drawn on a hemisphere, with the boundary as equator. If

, then set

. By Propositions 1 and 2, then

,

.

□

Theorem 8. There exists a fullerene F such that , , .

Proof. Let

be a fragment of

F as shown in

Figure 3. Its boundary

is labelled

along the clockwise direction, where

and

are two consecutive 2-degree vertices. Let

be a fragment of

F as shown in

Figure 5(c). Its boundary

is labelled

along the clockwise direction, where

and

are two consecutive 3-degree vertices. Next assume the graphs

and

each drawn on a hemisphere, with the boundary as equator. If

, then set

. By Propositions 1 and 3, then

,

,

.

□

Theorem 9. There exists a fullerene F such that , .

Proof. Let

be a fragment of

F as shown in

Figure 3. Its boundary

is labelled

along the clockwise direction, where

and

are two consecutive 2-degree vertices. Let

be a fragment of

F as shown in

Figure 6(b). Its boundary

is labelled

along the clockwise direction, where

and

are two consecutive 3-degree vertices. Next assume the graphs

and

each drawn on a hemisphere, with the boundary as equator. If

, then set

. By Propositions 1 and 4, then

,

.

□