1. Introduction: The Role of Culture in International HRM:

Culture is not simply a background variable, it is a constitutive force shaping how individuals experience authority, negotiate meaning, and respond to institutional norms. For international human resource management (IHRM), culture functions as both a constraint and a resource.

As multinational enterprises (MNEs) expand their operations across borders, the need to reconcile corporate objectives with culturally specific expectations becomes central to HRM strategy. What constitutes “effective leadership,” “performance,” or “loyalty” can differ significantly between contexts, requiring HR professionals to develop a culturally intelligent lens.

Within this context, Hofstede’s cultural dimensions provide a foundational framework for understanding how shared values influence work behavior, motivation, and organizational structure. His research offers a typological classification of national cultures that enables HR professionals to predict general tendencies in employee preferences and workplace expectations. However, the applicability of these dimensions is far from mechanical. Culture is not a fixed template; it is enacted and contested through practice. Thus, successful IHRM entails not only knowing cultural metrics but also interpreting how these dimensions manifest in local interactions and organizational routines.

Dowling, Festing, and Engle (2017) highlight the challenges HR professionals face in navigating cultural diversity, emphasizing that key HR functions which are staffing, performance evaluation, reward systems, and training are deeply embedded in cultural meaning systems. For instance, a merit-based promotion system that rewards individual performance may resonate in the U.S. context but provoke discomfort in collectivist cultures where group harmony is prioritized.

This article expands upon such insights by revisiting Hofstede’s model within the wider scholarly landscape of organizational behavior and cultural theory. We argue that MNEs cannot afford to treat culture as a static variable; instead, HRM must be reconceptualized as a practice of continuous cultural negotiation. In this view, managing cultural difference becomes less about compliance and more about co-constructing meaning across institutional boundaries.

We also take seriously the critique that Hofstede’s framework, while empirically grounded, risks reifying national cultures into essentialist categories. To address this limitation, we propose an adaptive and reflexive approach to applying cultural dimensions in IHRM. This approach privileges the lived experiences of employees, the evolving nature of work, and the multi-scalar challenges of organizing across geographies.

2. Revisiting Hofstede’s Dimensions Through the HRM Lens:

Hofstede’s six dimensions of culture, though often cited descriptively, offer fertile ground for strategic adaptation in IHRM. Rather than merely aligning HR policies with national tendencies, organizations must interpret these dimensions as frameworks for understanding divergent value systems and behavioral expectations. Each dimension can signal different forms of legitimacy, trust, and motivation, depending on the cultural context.

2.1. Power Distance Refers to How Societies Manage Inequality and Hierarchy:

In high power distance contexts like the Middle East or parts of Asia, authority is rarely questioned, and hierarchical structures dominate. HR professionals must recognize the importance of status, difference to seniority, and formalized communication channels. Promotions may be based less on performance metrics and more on seniority or familial ties, requiring a recalibration of Western-centric meritocracy assumptions.

In contrast, low power distance societies such as Sweden or New Zealand prioritize egalitarianism and expect participative management. Here, HR should encourage decentralized decision-making, open-door policies, and bottom-up feedback mechanisms. An expatriate manager from a high-power distance country may need training to adapt to flatter structures where direct reports actively challenge decisions.

2.2. Individualism vs. Collectivism Captures the Tension Between Personal Autonomy and Group Affiliation:

In individualistic cultures (e.g., USA, UK), self-initiative, mobility, and personal achievements are rewarded. HR strategies emphasize personal career development plans, flexible benefits, and individualized feedback.

In collectivist cultures (e.g., China, Indonesia), loyalty to the group is paramount. HR should promote team-based performance evaluations, emphasize social cohesion, and build long-term employment relationships. Misalignment in this area can lead to disengagement or attrition, particularly when Western management practices ignore collective norms.

2.3. Uncertainty Avoidance Relates to a Society’s Tolerance for Ambiguity and Change:

Countries high in uncertainty avoidance (e.g., Japan, Greece) value procedural clarity and risk aversion. HR must therefore invest in clear job descriptions, procedural manuals, and compliance frameworks. Training should focus on rules, predictability, and minimizing ambiguity.

By contrast, low uncertainty avoidance cultures (e.g., India, Singapore) thrive in dynamic, fast-paced environments. Flexibility, experimentation, and creative problem-solving are valued. HR can facilitate agility through agile project teams, innovation labs, and tolerance for failure.

2.4. Masculinity vs. Femininity Examines the Balance Between Competition and Care:

Masculine societies (e.g., USA, Germany) promote assertiveness, goal-orientation, and performance-based rewards. HRM should reinforce high-performance cultures through reward schemes and leadership development programs that stress competition.

Feminine cultures (e.g., Netherlands, Denmark) value work-life balance, nurturing environments, and cooperation. HR initiatives might include flexible work schedules, holistic wellness programs, and inclusive leadership models that promote empathy and collaboration.

2.5. Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation Underscores Whether a Culture Emphasizes:

Perseverance or immediate gains. Long-term oriented cultures (e.g., South Korea, Taiwan) invest in sustained growth and education. HR should prioritize employee retention, succession planning, and lifelong learning.

Short-term cultures (e.g., Nigeria, USA) focus on quarterly outcomes and rapid advancement. Performance bonuses, quick wins, and visible metrics become key tools for motivating employees.

2.6. Indulgence vs. Restraint Differentiates Between Cultures That Encourage the Gratification of Desires Versus Those That Suppress It.

Indulgent cultures promote leisure, expression, and emotional well-being. HR may develop recreation spaces, mental health initiatives, and flexible time-off policies.

Restrained cultures value discipline and social regulation. HR must manage expectations around personal expression, enforce formal codes of conduct, and structure career progression within well-defined boundaries.

To better understand how Hofstede’s cultural dimensions influence organizational behavior, the table below maps each dimension to specific HRM implications. This overview provides a foundational lens for interpreting cultural variance in staffing, performance evaluation, and leadership expectations.

Table 1.

1. HRM Implications of Hofstede’s Six Cultural Dimensions:.

Table 1.

1. HRM Implications of Hofstede’s Six Cultural Dimensions:.

| Cultural Dimension |

Definition |

Impact on HRM Practices |

| Power Distance |

The degree to which less powerful members accept unequal power distribution. |

High: Emphasizes hierarchical structures and top-down leadership. |

| Individualism vs. Collectivism |

The extent to which individuals are integrated into groups. |

Individualistic: Focus on autonomy, rewards for personal achievements. |

| |

|

Collectivist: Emphasis on group harmony, loyalty, and long-term job security. |

| Uncertainty Avoidance |

The degree to which a society tolerates ambiguity and uncertainty. |

High: Focus on structured environments and detailed policies. |

| |

|

Low: Encourages flexibility and innovation in problem-solving. |

| Masculinity vs. Femininity |

The degree to which societies value competitiveness, assertiveness, and achievement. |

Masculine: Focus on competition, achievement, performance-based rewards. |

| |

|

Feminine: Emphasis on work-life balance, equality, and social benefits. |

| Long-Term vs. Short-Term Orientation |

The extent to which a culture prioritizes long-term vs. short-term results. |

Long-Term: Focus on stability, career development, succession planning. |

| |

|

Short-Term: Emphasis on immediate performance and results. |

| Indulgence vs. Restraint |

The degree to which societies allow or restrict gratification of desires. |

Indulgent: Focus on work-life balance, leisure, and employee engagement. |

| |

|

Restrained: Focus on discipline, structured incentives, and formal expectations. |

This table underscores the value of Hofstede’s model in predicting cultural tendencies that shape human resource practices, while also highlighting the need for cultural sensitivity in HR design.

Regional contrasts in cultural orientation can significantly impact how HRM is practiced.

The following table compares key HR functions across Europe and the MENA region, highlighting how cultural expectations shape approaches to recruitment, training, and conflict resolution.

Table 1.

2. Comparative HRM Practices in Europe and the MENA Region:.

Table 1.

2. Comparative HRM Practices in Europe and the MENA Region:.

| HR Function |

Europe (France, Germany) |

MENA (Tunisia, Saudi Arabia) |

| Recruitment Style |

Competency-based, open applications |

Network-based, referrals, wasta (influence) |

| Training Approaches |

Continuous learning, skill certification |

Value-based training, on-the-job mentorship |

| Reward Systems |

Performance-linked, individual bonuses |

Status-based, seniority-driven rewards |

| Conflict Management |

Constructive confrontation encouraged |

Harmony-seeking, conflict avoidance preferred |

| Decision-Making Style |

Participative |

Centralized, authority-respecting |

This comparison highlights the contextual diversity facing international HR professionals and the necessity of tailoring practices to regional socio-cultural dynamics.

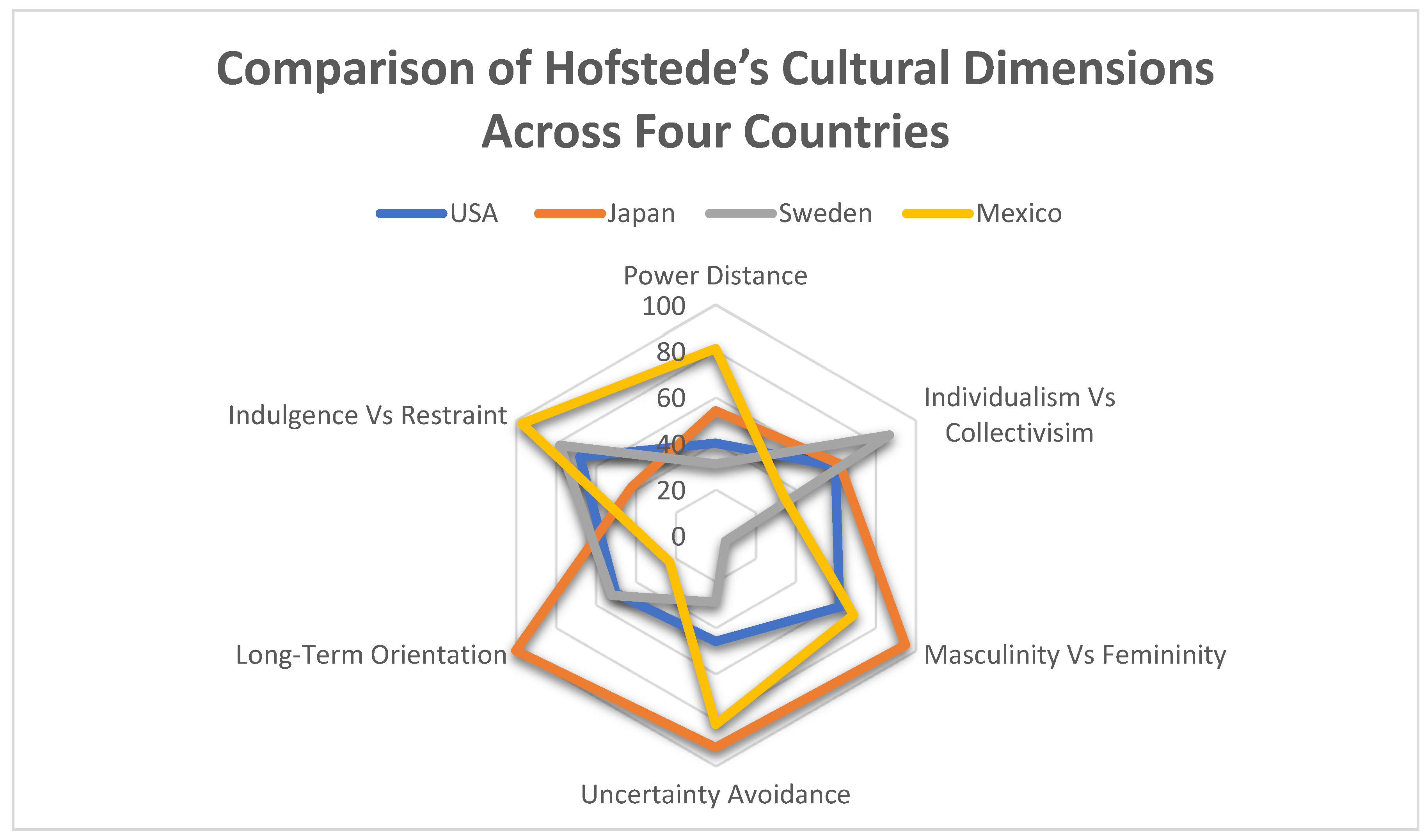

To illustrate the variation across national cultures, the graph below visualizes Hofstede’s six dimensions for four countries: the United States, Japan, Sweden, and Mexico. These countries represent distinct cultural regions and demonstrate how differently values such as hierarchy, individualism, and uncertainty are emphasized.

Graph 1.

Comparative Hofstede Cultural Dimension Scores by Country.

Graph 1.

Comparative Hofstede Cultural Dimension Scores by Country.

This graph reinforces the need for culturally aware HR strategies, as even globally integrated firms must account for national cultural profiles when designing management systems.

3. Culture as a Dynamic Construct in Organizational Contexts:

The traditional application of Hofstede’s framework in IHRM has often been criticized for its static and deterministic character. While national culture remains a useful reference point, organizational actors do not passively inherit these cultural values; they interpret, negotiate, and even challenge them through everyday practice. As such, culture in the organizational setting should be viewed as dynamic, contested, and continually reconfigured by interactions at multiple levels: individual, organizational, and institutional.

Recent contributions in organization theory support a more constructivist approach to understanding culture. Scholars such as DiMaggio (1997) and Giddens (1984) remind us that culture is not merely “absorbed” but enacted shaped through structures of meaning, power, and identity. This has critical implications for IHRM. For example, while a corporate headquarters in Germany may endorse egalitarian HR practices based on a low power distance orientation, a subsidiary in Morocco may simultaneously negotiate these practices through a cultural lens that prioritizes hierarchy and seniority. The resulting practices are neither fully “German” nor “Moroccan”, but a hybrid form shaped by the interaction of local actors and global imperatives.

Furthermore, cross-cultural interactions in MNEs often produce emergent cultural forms that cannot be predicted by Hofstede’s categories. Employees from diverse cultural backgrounds may develop shared norms that transcend their national origins, particularly when collaborating in transnational teams. In such settings, HR’s role becomes less about managing “national differences” and more about cultivating intercultural fluency, psychological safety, and reflexivity. Cultural intelligence (CQ) and global mindset thus become vital capabilities for both employees and HR leaders.

The use of cultural archetypes, while helpful in framing HR policies, risks oversimplifying the lived experience of cultural identity. Individuals may embody multiple, overlapping cultural identities depending on their education, profession, religion, gender, and migration history. This complexity challenges the idea that an “American” or “Saudi” employee will conform to any singular set of expectations. IHRM policies should therefore be designed with room for customization, sensitivity, and iterative feedback.

Moreover, organizational culture itself often mediates national culture. The internal norms, values, and symbols cultivated within a company may supersede or reconfigure external cultural norms. A case in point is the international success of companies like Google or Unilever, whose organizational cultures emphasize innovation, inclusion, and adaptability. Such firms invest heavily in cross-cultural training, onboarding rituals, and HR systems that embed desired values across borders. These practices not only enable knowledge transfer but also create coherence across geographies.

Digital transformation and remote work have added further layers of complexity. Asynchronous communication, digital collaboration tools, and virtual onboarding reduce face-to-face cues that traditionally help interpret cultural signals. This necessitates new HR protocols to maintain cultural connectedness, prevent miscommunication, and foster team cohesion. For instance, virtual cross-cultural training, storytelling platforms, and culturally adapted onboarding modules are gaining popularity in global HRM.

To remain effective, HRM must move from a logic of compliance treating culture as an obstacle to a logic of co-creation, viewing culture as an evolving resource. This requires HR professionals to operate as cultural intermediaries who bridge expectations, reframe conflicts, and facilitate mutual understanding. Integrating anthropological methods such as ethnography or participatory observation can enhance cultural diagnosis and policy design.

In sum, reconceptualizing culture as a dynamic and interactional phenomenon not only aligns with contemporary organization theory but also equips IHRM to better navigate the cultural heterogeneity of today’s global workforce. It invites a shift from managing diversity as difference to leveraging it as a developmental capacity.

As discussed above, organizational culture interacts dynamically with national cultural values, producing hybrid practices in multinational enterprises (MNEs).

The following table illustrates how differing cultural logics can shape HR practices through negotiation between corporate norms and local expectations.

Table 2.

Interactions Between National and Organizational Culture in MNEs:.

Table 2.

Interactions Between National and Organizational Culture in MNEs:.

| Cultural Aspects |

National Culture Characteristic |

Organizational Culture Influence |

Resulting Hybrid Practice Example |

| Power Distance |

High in Morocco |

Low in German Headquarters |

Moderated hierarchy with participative local input |

| Individualism Vs Collectivism |

Collectivist (Japan) |

Innovative, Individualist tech firm culture |

Balanced team-based innovation initiatives |

| Uncertainty Avoidance |

High (Japan) |

Agile Startup Culture |

Formal risk protocols integrated with agile project teams |

This table illustrates how national cultural traits and organizational norms interact to form hybrid HR practices, showing that culturally responsive strategies emerge through negotiation rather than one-way implementation.

As shown in the previous table, the blending of organizational and national cultures creates hybrid work practices. This convergence also influences how employees perceive and construct their cultural identities.

The graph below offers a conceptual visualization of this trend, illustrating how a growing number of employees navigate multiple overlapping cultural affiliations in today’s global workplace.

Graph 2.

Conceptual Trend of Cultural Identity Complexity Among Global Employees.

Graph 2.

Conceptual Trend of Cultural Identity Complexity Among Global Employees.

This graph demonstrates that employee identities are increasingly layered and hybrid, reinforcing the need for flexible HRM approaches that can accommodate multicultural affiliations and evolving identity structures.

4. Toward an Adaptive Framework for Culturally Responsive HRM:

Building on the insights above, this section outlines a model for adaptive HRM in multicultural environments. The goal is not to replace Hofstede’s dimensions but to recontextualize them within a broader framework that emphasizes responsiveness, dialogue, and mutual transformation.

4.1. Interpretive Flexibility:

The adaptive model begins with the recognition that culture cannot be “read off” from national profiles. Instead, HRM must prioritize interpretive flexibility; the capacity to analyze how cultural dimensions are locally interpreted and embedded in specific organizational settings. This requires active listening, context mapping, and continual sensemaking. For instance, “collectivism” in Tunisia may manifest through kinship networks and religious norms, while in Japan it may appear through institutional loyalty and group consensus.

4.2. Reflexive Design:

Second, HR strategies should be designed reflexively, with built-in mechanisms for cultural feedback. Rather than enforcing a uniform set of practices across subsidiaries, adaptive HRM embraces modularity allowing for local adaptation of training, evaluation, and incentive systems while maintaining core principles. Reflexivity also entails a critical awareness of the HR function’s own cultural biases, ensuring that strategy development is dialogical rather than top-down.

4.3. Culturally Situated Competency Models:

Third, global competency frameworks should be informed by local conceptions of leadership, success, and professionalism. For example, while Western models may prioritize assertiveness and innovation, cultures in the MENA region may emphasize wisdom, humility, and relational intelligence. Adaptive HRM encourages co-designed competency models that reflect both corporate values and local sensibilities.

4.4. Strategic Cultural Interventions:

Fourth, HR can act as a driver of organizational change by implementing cultural interventions that support long-term integration. This includes onboarding programs that emphasize cultural humility, mentorship initiatives across cultural lines, and leadership development paths that recognize intercultural achievements. HR professionals must also be equipped to mediate cultural tensions, for example, between expatriate managers and local staff, or between headquarters and regional units.

4.5. Institutional Embeddedness:

Fifth, HR policies must be embedded within local institutional contexts. Laws governing employment contracts, gender equality, unionization, and religious holidays vary significantly across regions. Effective HRM not only complies with these regulations but aligns them with organizational culture in ways that support legitimacy and employee trust. Collaboration with legal advisors, sociologists, and local community leaders can enhance the embeddedness and legitimacy of HR practices.

4.6. Learning Loops and Digital Integration:

Finally, adaptive HRM depends on continuous learning and digital integration. Feedback loops such as employee satisfaction surveys, cultural climate audits, and exit interviews can inform iterative policy adjustments. Digital platforms can facilitate cross-cultural learning through e-learning modules, intercultural simulations, and knowledge-sharing networks.

Ultimately, an adaptive framework does not view culture as a barrier to overcome but as a terrain to be engaged with curiosity, humility, and strategic foresight. It offers a pathway for HR professionals to become agents of inclusive globalization, supporting the development of resilient, innovative, and human-centered organizations.

The diagram below outlines a four-step process for integrating cultural awareness into HR practices within multinational enterprises. It highlights how cultural assessment, policy localization, cross-cultural training, and feedback mechanisms contribute to culturally responsive HR management.

To operationalize cultural adaptability in HR strategy, organizations can follow a structured yet flexible process. The diagram below outlines key steps ranging from cultural assessment to continuous feedback that support the creation of inclusive, responsive, and context-sensitive HR policies across borders.

This diagram outlines a proactive framework for integrating cultural awareness into HR practices, stressing the importance of iterative assessment and localization to maintain relevance across diverse cultural settings.

Translating adaptive HR principles into practice requires a strategic alignment between cultural insight and HR action.

The following table maps six core components of an adaptive HRM model to specific HR activities that can help organizations manage cultural complexity more effectively.

Graph 3.

Process for Building Culturally Adaptive HR Policies in MNEs.

Graph 3.

Process for Building Culturally Adaptive HR Policies in MNEs.

Table 2.

Key Components of Adaptive HRM and Their Practical Applications:.

Table 2.

Key Components of Adaptive HRM and Their Practical Applications:.

| Component |

Description |

HR Activities Example |

| Interpretive Flexibility |

Contextual understanding of cultural meanings |

Cultural audits, local context research |

| Reflexive Design |

Designing adaptable HR policies |

Modular training programs, feedback mechanisms |

| Culturally Situated Competency Models |

Leadership frameworks rooted in local values |

Co-designed competency frameworks, mentoring |

| Strategic Cultural Interventions |

HR-led initiatives supporting integration |

Cross-cultural onboarding, mentorship programs |

| Institutional Embeddedness |

Alignment with local laws and norms |

Legal compliance checks, partnerships with local orgs |

| Learning Loops and Digital Integration |

Continuous feedback and digital learning |

E-learning modules, cultural climate surveys |

This table identifies the building blocks of an adaptive HRM strategy, demonstrating how culturally sensitive design can be operationalized across core HR functions to enhance cross-cultural effectiveness.

5. Implications and Future Directions:

The reconceptualization of culture and HRM outlined in this article holds important theoretical and practical implications. From a theoretical perspective, it challenges the reductionist logic of mainstream cross-cultural management and invites a more situated, reflexive, and process-oriented approach. This resonates with broader trends in organization theory that emphasize pluralism, hybridity, and the role of agency in institutional environments (Kostova et al., 2008; Greenwood et al., 2010). It also aligns with the call to decolonize management knowledge by valuing local voices, indigenous practices, and Southern epistemologies (Jack & Westwood, 2009).

Practically, the adaptive framework offers IHRM professionals a toolkit for navigating cultural complexity in ways that are responsive, ethical, and developmentally oriented. It urges a departure from compliance-based HR templates toward designs that are dialogical and contextually embedded. This shift is particularly relevant for firms operating in regions like the MENA, where formal institutions may be weak or in flux, and informal networks (wasta, kinship, faith-based norms) significantly shape work dynamics.

The implications are especially critical for leadership development, talent management, and organizational learning. Companies that embrace adaptive HRM are better positioned to attract, retain, and empower culturally diverse talent. They are also more likely to innovate by leveraging the cognitive diversity of multicultural teams. In turn, this supports competitive advantage in the increasingly interconnected global economy.

However, this approach is not without challenges. Adaptive HRM requires substantial investment in training, cultural mediation, and iterative policy design. It also demands organizational structures that support flexibility, such as decentralized decision-making, cross-cultural task forces, and open communication channels. Moreover, the tension between global standardization and local adaptation remains a central dilemma, requiring constant negotiation and alignment between headquarters and subsidiaries.

Future research could extend this work in several directions. First, empirical studies are needed to test the efficacy of adaptive HRM models across different regions and industries. Longitudinal case studies, action research, and ethnographic methods can provide deeper insights into how cultural responsiveness unfolds over time. Second, the intersection of culture with other identity markers such as gender, religion, and migration warrants closer attention, particularly in regions characterized by high social stratification.

Third, the growing influence of digitalization and AI in HRM opens up new avenues for culturally adaptive technologies, such as AI-driven intercultural coaching or algorithmic bias audits in recruitment platforms.

In all these directions, the core insight remains culture in HRM should be treated not as a static input but as a dynamic field of interaction, contestation, and possibility.

Looking ahead, a stronger understanding of culture in IHRM will depend on rigorous, context-sensitive research.

The table below outlines key questions and methodological avenues that can guide future studies on cultural negotiation, hybridization, and digital mediation in HR practices.

Table 4.

Future Research Directions for IHRM and Culture:.

Table 4.

Future Research Directions for IHRM and Culture:.

| Research Focus Area |

Key Questions |

Methodological Questions |

| Dynamic cultural negotiation |

How do employees

co-construct culture in real time? |

Ethnography, participatory observation |

| Hybrid organizational cultures |

What are emergent cultural forms in MNEs? |

Comparative case studies, cross-cultural interviews |

| Digital mediation of culture |

How does remote work impact cultural transmission? |

Surveys, digital ethnography, longitudinal studies |

| Culturally adaptive HR frameworks |

What are the best practices for reflexive HR design? |

Action research, intervention based longitudinal studies |

This table offers a forward-looking research roadmap for IHRM, encouraging methodological innovation and deeper inquiry into how culture is negotiated and transformed within global HR contexts.

6. Conclusion:

This article argued for a reimagining of culture and HRM in international settings. While Hofstede’s framework has provided a valuable foundation for understanding cultural variation, it falls short in capturing the lived complexity, fluidity, and constructed nature of culture in global organizations. Relying solely on dimensional models risks reifying stereotypes and missing the richness of cultural negotiation that characterizes contemporary workplaces.

By embracing an adaptive, reflexive, and context-sensitive approach, HRM can evolve beyond managing difference to enabling development, inclusion, and organizational transformation. The proposed framework emphasizes interpretive flexibility, modularity, reflexive design, and strategic cultural interventions all grounded in institutional and local realities. It positions HR professionals not as enforcers of global templates but as cultural mediators who facilitate co-creation and shared meaning across diverse settings.

In the face of global crises, migration flows, digital disruption, and shifting power dynamics, such an approach is not only desirable but necessary. As organizations become increasingly transnational, their capacity to cultivate inclusive, flexible, and culturally intelligent work environments will determine both their ethical legitimacy and strategic resilience.

Ultimately, this article calls for a more nuanced, theory-informed, and practice-oriented understanding of culture in international HRM one that reflects the multiplicity of voices, identities, and narratives that shape today’s organizations. It is through this lens that we can build workplaces that are not only globally connected but also locally resonant and socially responsive.

References

- Dowling, P. J. , Festing, M., & Engle, A. D. (2017). International human resource management (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- DiMaggio, P. (1997). Culture and cognition. Annual Review of Sociology, 23(1), 263–287. [CrossRef]

- Dowling, P. J. , Festing, M., & Engle, A. D. (2017). International human resource management (7th ed.). Cengage Learning.

- Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. University of California Press.

- Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., & Lounsbury, M. (2011). Institutional complexity and organizational responses. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1), 317–371. [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture's consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Jack, G. , & Westwood, R. (2009). International and cross-cultural management studies: A postcolonial reading. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kostova, T. , Roth, K., & Dacin, M. T. (2008). Institutional theory in the study of multinational corporations: A critique and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 994–1006. [CrossRef]

- https://www.theculturefactor.com/country-comparison-tool?countries=.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).