1. Introduction

Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) has transformed the educational landscape, promoting significant changes both in teaching methodologies and in students’ learning experiences [Adewale et al. 2024]. One of AI’s main objectives in education is to provide personalized learning, adapting to each student’s knowledge level, difficulties, and study style [Hwang et al. 2020]. Much of the research in this area focuses on optimizing teaching and learning processes, while the impacts of GenAI on students’ academic performance have still received less attention [Adewale et al. 2024].

Among the most impactful innovations are Large Language Models (LLMs), which, through their integration in various domains, have revolutionized the AI field [Jošt et al. 2024]. They are redefining natural language processing, content generation, and text comprehension, paving the way for promising innovations and significantly impacting various areas of knowledge [Ferreira 2024]. LLMs are trained with an enormous amount of textual data and possess advanced natural language comprehension capabilities, allowing the resolution of complex tasks autonomously [Zhao et al. 2023]. In software development, these models have demonstrated their effectiveness by assisting with tasks such as identifying errors, proposing enhancements, and generating code snippets, thereby boosting productivity and minimizing human mistakes [Guo et al., 2024].

However, the growing influence of LLMs in the educational environment also raises concerns. A study conducted by Hernandez et al. [2023] demonstrated that adaptive technologies, adjusting to students’ learning styles and paces, can increase their confidence and enhance their ability to master content at their own pace. Nevertheless, excessive reliance on GenAI in the learning process can compromise the development of problem-solving skills and reduce students’ sense of autonomy. Consequently, some students have displayed anxiety, questioning their own abilities and feeling inferior compared to AI-based technologies [Asio and Suero 2024].

This insecurity related to GenAI is not limited to the academic environment but also extends to students’ professional future. With the growing adoption of this technology in various fields, many students fear that the careers they are preparing for may become obsolete [Chan and Hu 2023]. Moreover, its increasing use may raise recruitment standards. In this context, the ability to successfully enter the job market may depend not only on formal qualifications but also on AI literacy—an area where students from disadvantaged and international backgrounds are often at a disadvantage due to the persistent digital divide.

As highlighted by Zhou, Fang, and Rajaram [2025], disparities in digital literacy, access to institutional support, and familiarity with technological tools tend to widen over the course of undergraduate studies, limiting students’ capacity to engage in digital learning environments and to develop the competencies increasingly demanded by employers. From a connectivist perspective, this unequal access to digital networks and resources not only hinders educational progress but also places certain students at a disadvantage when transitioning into digitally driven professional contexts.

In light of these widening disparities, recent discussions around educational policy have emphasized the importance of fostering AI literacy among students. The Artificial Intelligence Literacy Act of 2023 (H.R.6791), introduced in the U.S. Congress, defines AI literacy as the skills associated with the ability to comprehend the basic principles, concepts, and applications of artificial intelligence, as well as the implications, limitations, and ethical considerations associated with the use of artificial intelligence. According to the bill, maintaining technological leadership in AI is a matter of economic and national security, which demands a workforce that combines both technical experts (e.g., engineers and data scientists) and nontechnical professionals who understand the capabilities and consequences of AI.

However, despite these policy efforts to promote AI literacy, many students still feel unprepared to navigate a job market increasingly shaped by generative AI technologies. The rapid evolution of these tools introduces an additional layer of concern for students—not only as a technological challenge, but as a perceived threat to their future employability. Among the main concerns of students is the potential of GenAI to replace human labor, increasing the risk of large-scale unemployment. For students in training, the exponential advance of this technology represents a concrete threat, increasing uncertainty about the job market and amplifying concerns about unemployment [Wang et al. 2022].

1.1. Objectives

Based on the previous discussion, this study aims to identify which groups of students show greater concern regarding replacement by GenAI in the job market. In addition, it seeks to map the characteristics of these students, analyzing factors such as time in the program, learning strategies, AI technology anxiety and difficulties in using LLMs for comprehension and problem-solving. By outlining the profile of students most susceptible to this fear, the intention is to contribute to a better understanding of the impacts of GenAI on academic training and on the professional expectations of computing students.

1.2. Related Works

Recent studies have explored the complexities surrounding students’ and professionals’ perceptions of GenAI integration in educational and occupational contexts. Nkedishu and Okonta [2024], for instance, found contrasting attitudes between students from different academic backgrounds: while those in Computer Science generally viewed AI as an opportunity, students in the humanities expressed deeper concerns regarding social implications, job displacement, and the need for ongoing retraining.

Pinto et al. [2023] conducted an empirical investigation with computer science students to explore the relationship between frequent interaction with LLMs and rising anxiety about AI-driven changes in the job market. The study employed validated psychometric scales to assess emotional and cognitive responses. While familiarity with these tools can enhance academic productivity, it may also heighten fears of professional obsolescence. Their findings underscore the importance of developing metacognition, highlighting the role of emerging skills such as prompt engineering and advanced digital literacy.

Further contributing to this debate, da Silva et al. [2024] conducted a mixed-methods survey focused on ethics and responsibility among students in computing-related programs. Their results reveal that while many students acknowledge the benefits of generative AI tools, a significant proportion also express ethical concerns about privacy, algorithmic transparency, and dependency. The lack of formal instruction on AI ethics in many curricula further exacerbates this tension, pointing to an urgent need for structured ethical education.

Carvalho et al. [2024] broaden the conversation by surveying attitudes toward AI across sectors including education, healthcare, and creative industries. Employing the ATAI scale and ensuring psychometric quality in their measurements, the study found moderate trust in AI, high perceived benefits, and relatively low fear, yet a persistent concern about job displacement — especially in Latin American contexts. Many participants were unaware of how AI already influenced their daily lives, which underscores the need for increased AI literacy and awareness in both public and educational spheres.

Most recently, Delello et al. [2025] surveyed over 330 educators from around the world, focusing on AI’s integration in classrooms, its perceived benefits, and its impacts on both teaching and mental health. While educators acknowledged AI’s potential for increasing efficiency, personalization, and student motivation, many also raised concerns about reduced interpersonal interaction, increased technostress, and the absence of institutional policies to guide ethical AI use. The study also identified a pressing need for professional development, particularly training on ethical usage, privacy, and strategies for mental health support in AI-mediated educational environments.

2. Methodology

2.1. Procedures and Participants

The dataset used in this study was retrieved from Kaggle, where it was made publicly available by Pinto [2025] for future analysis and research reuse. This dataset is notable for its richness, comprising both detailed sociodemographic information and responses to five psychometric scales that have been previously validated for use in Brazil. The data were originally collected through a probability-based survey conducted in 2023, using Google Forms. A total of 178 students participated in the survey, with a gender distribution of 143 male respondents (80.3%) and 35 female respondents (19.7%). In terms of academic background, the majority were undergraduate students enrolled in Computer Science and related programs.

2.2. Instruments

The dataset includes five psychometric scales, all of which have been previously validated for use in the Brazilian context [Pinto et al., 2023]. These instruments assess a range of constructs relevant to students' experiences with GenAI. Each item was rated on a 7-point Likert scale, with response options ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree” and from “Never” to “Always,” depending on the construct being measured. This format allows for a nuanced assessment of participants’ positions across multiple dimensions.

However, rather than applying a traditional psychometric framework based on pre-established factors or constructs, the authors adopted a Machine Learning (ML) based exploratory approach. The goal was to identify latent patterns and associations between items across different scales without the rigidity typically associated with confirmatory psychometric analysis. This strategy enabled a more flexible and data-driven investigation of the psychological and educational dynamics involved in students’ interactions with GenAI tools.

2.3. Data Analysis

The dataset were analyzed with the aim of identifying patterns among students, using the unsupervised learning algorithm K-means, listed among the 10 most frequently used clustering algorithms for data analysis [Ahmed et al. 2020]. Two distinct clusterings were carried out. The first clustering used the variables “I worry that programmers will be replaced by artificial intelligence models” and “I feel as if I cannot keep up with the changes brought about by artificial intelligence models”. The second clustering considered the variables “I worry that programmers will be replaced by artificial intelligence models” and “I am afraid that artificial intelligence models will make the content I learned in college obsolete”.

The K-means algorithm requires the prior definition of the number of clusters, which determines how many groups are formed in data segmentation [Hamerly and Elkan 2003]. For this analysis, the number of clusters was set to 4 in both clusterings, using the Elbow Method, which identifies the optimal point of intra-cluster inertia reduction to determine the ideal number of groups. In the first clustering, although four clusters were generated, only three were considered relevant for the study and were selected for the final dataset: students concerned about AI replacement, students who do not exhibit this concern, and students who find it difficult to keep up with the technological changes brought about by GenAI. In the second clustering, two main profiles were selected: students concerned about GenAI replacement and students who do not exhibit concern about this replacement.

To consolidate the results, a final dataset was created by combining the five identified groups and removing possible duplicate samples. Bar charts were then generated to identify characteristics associated with students who are most apprehensive about being replaced by GenAI in the job market. All analyses were conducted using the Python language and open-source libraries, including pandas [McKinney 2010], matplotlib [Hunter 2007], and scikit-learn [Pedregosa et al. 2011].

2.4. GenAI Usage Statement

The translation of this article into English was carried out with the assistance of ChatGPT-4o, ensuring accuracy and fidelity to the original content. The authors remain fully responsible for the integrity, interpretation, and originality of the content presented.

4. Discussion

4.1. AI as Threat or Ally? The Impact of Educational Trajectories on Students’ Confidence Toward AI Integration

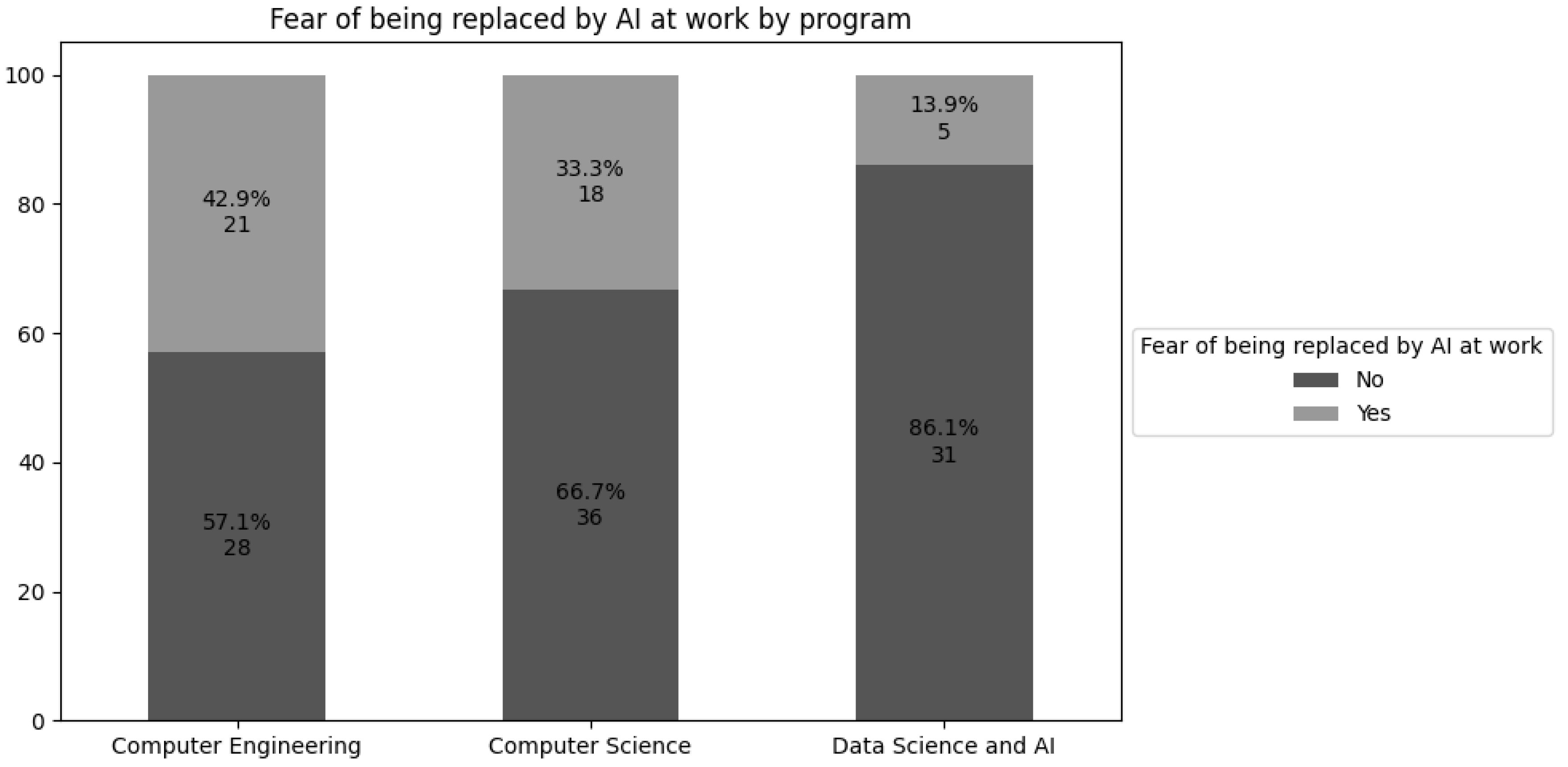

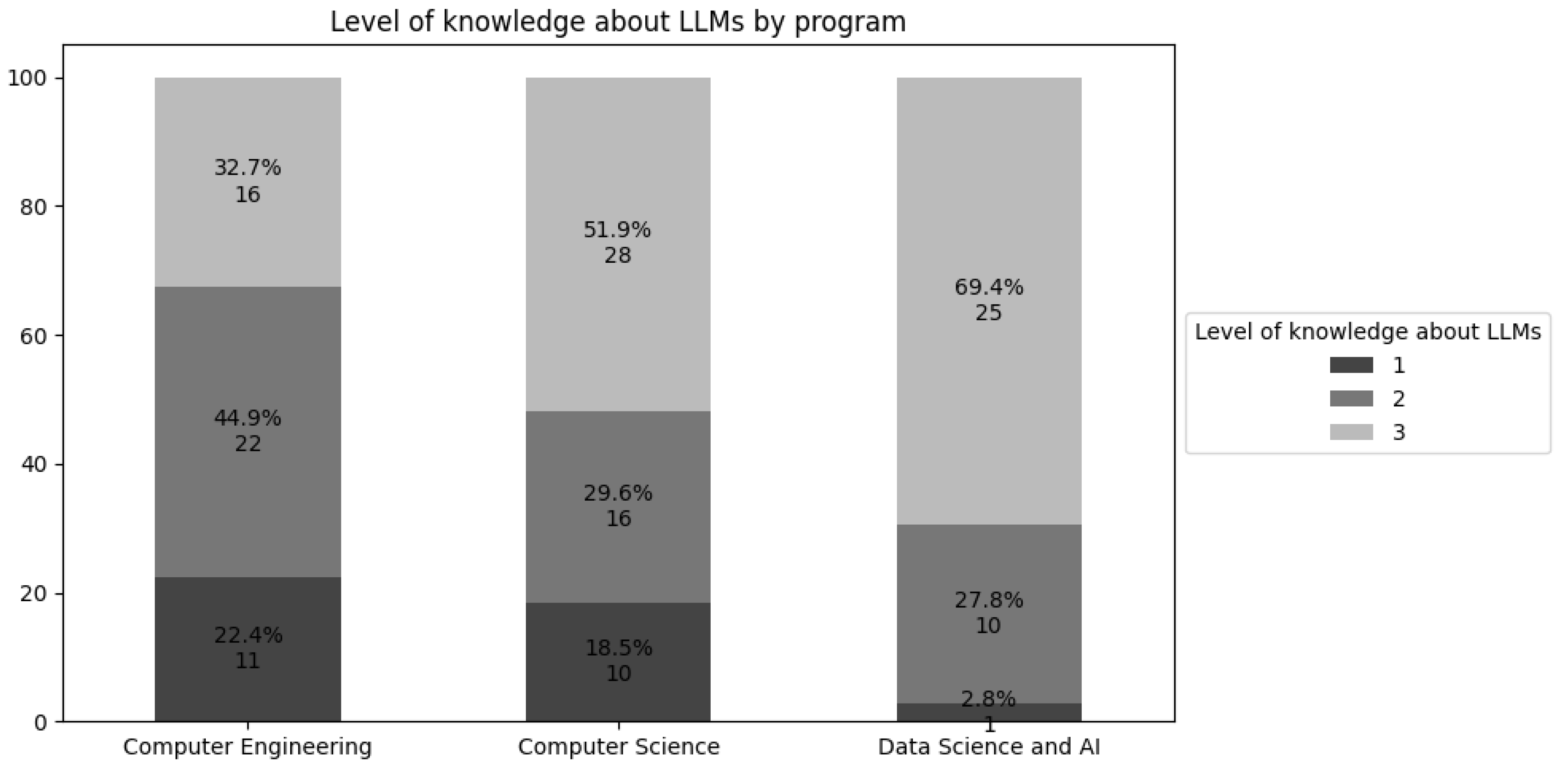

Analyses point to intriguing patterns about information technology students who experience apprehension regarding GenAI’s impact on their careers. Computer Engineering students express the highest concern about being supplanted by these systems, whereas individuals in Data Science and Artificial Intelligence report comparatively lower unease.

One explanation for this difference lies in the curriculum structures of each program. The Computer Engineering course includes only one mandatory subject focusing on AI — Introduction to Artificial Intelligence, administered in the 8th semester. Meanwhile, Data Science and Artificial Intelligence offers three compulsory courses — Introduction to Artificial Intelligence (4th semester), Machine Learning (5th semester), and Deep Learning (6th semester) — and one elective: Natural Language Processing (7th semester). The Computer Science course features two mandatory AI-related classes — Introduction to Artificial Intelligence (4th semester) and ML Paradigms (6th semester) — and two electives: Applied Artificial Intelligence in Health (5th semester) and Deep Learning (7th semester).

This difference in training directly influences the students’ level of familiarity with AI [Marrone et al. 2024]. Since the Computer Engineering program offers only one required course in the field, and even that in a later semester, it is natural for its students to have less contact with AI concepts and applications throughout the program. This limited involvement results in a narrower understanding of LLMs, which, in turn, increases insecurity regarding these technologies’ impact on the job market [Chan and Hu 2023]. On the other hand, students in Data Science and Artificial Intelligence, in addition to having greater exposure to the topic during the program, are trained to develop these technologies, contributing to a more positive perception of AI as an allied tool rather than a threat [Chan and Hu 2023].

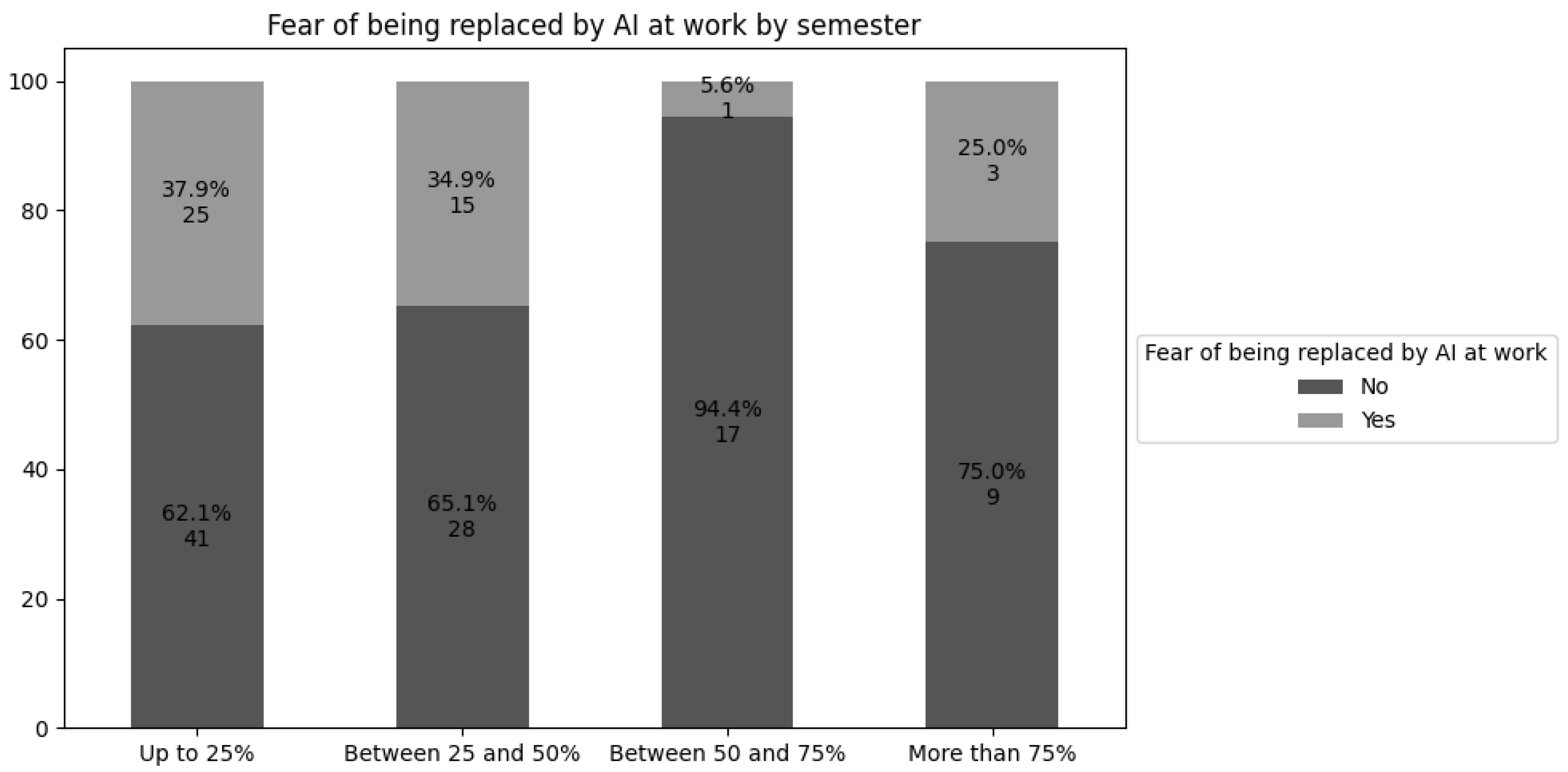

Furthermore, it is observed that most of the students who express this fear are in the initial semesters of their program, particularly in the first half of the course. This is directly related to the fact that, over time, students become more capable and gain familiarity with the technologies and tools they will use in their careers [Marrone et al. 2024]. However, this concern rises again in the final semesters, since, at the time of the questionnaire, the soon-to-graduate students had little contact with this technology. The lack of familiarity generates insecurity about how GenAI will affect their job opportunities, as they do not fully understand its potential and limitations [Tu et al. 2024].

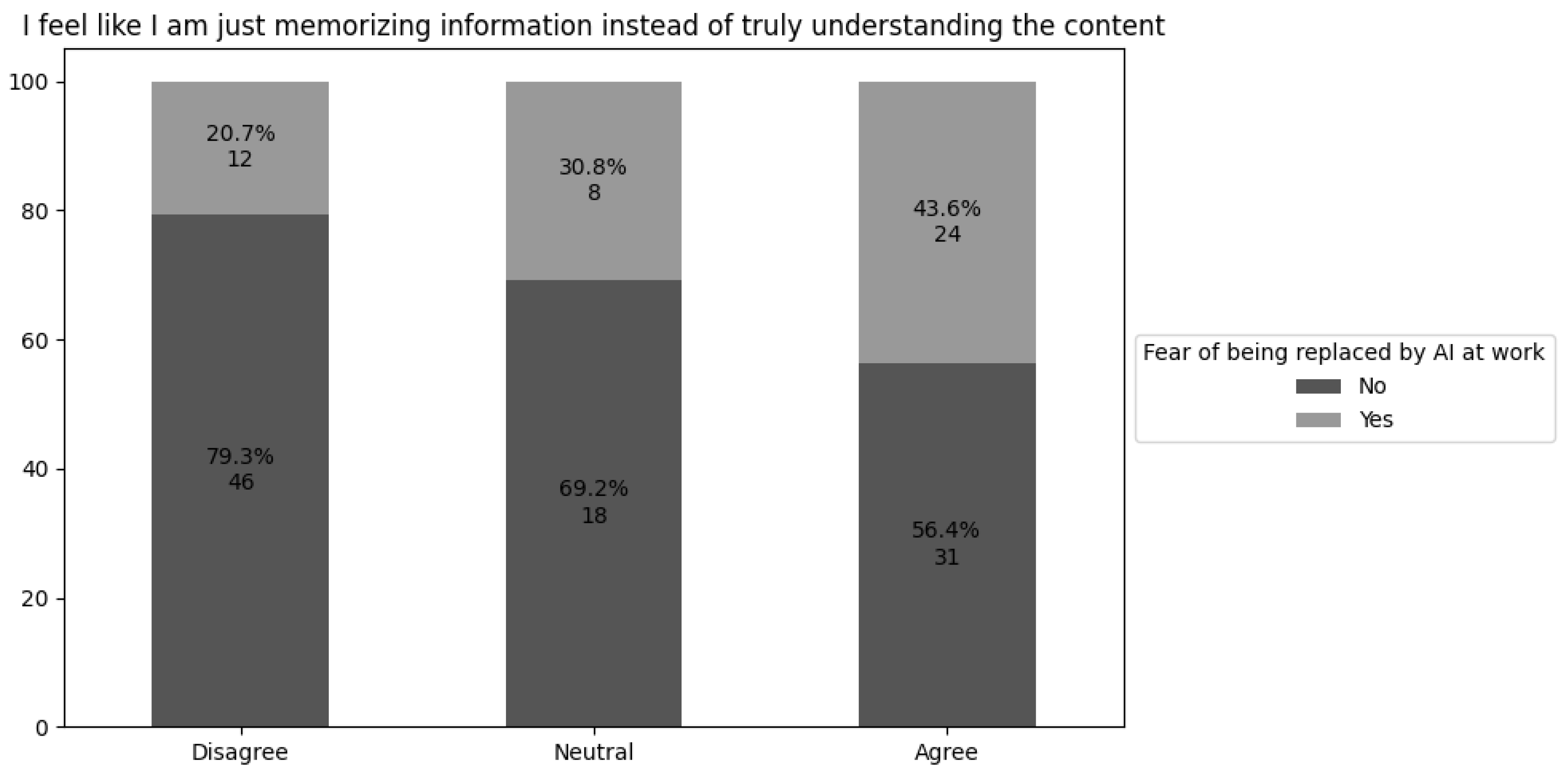

Another relevant aspect concerns the depth of learning and the development of critical technical skills. Data suggest that students who rely primarily on memorization — possibly focusing only on passing exams — tend to experience significantly greater fear of being replaced by GenAI in the job market. This pattern reflects lower levels of mastery and self-confidence in using technologies required in professional settings, making these students more vulnerable to uncertainty and automation threats [Chan and Hu, 2023].

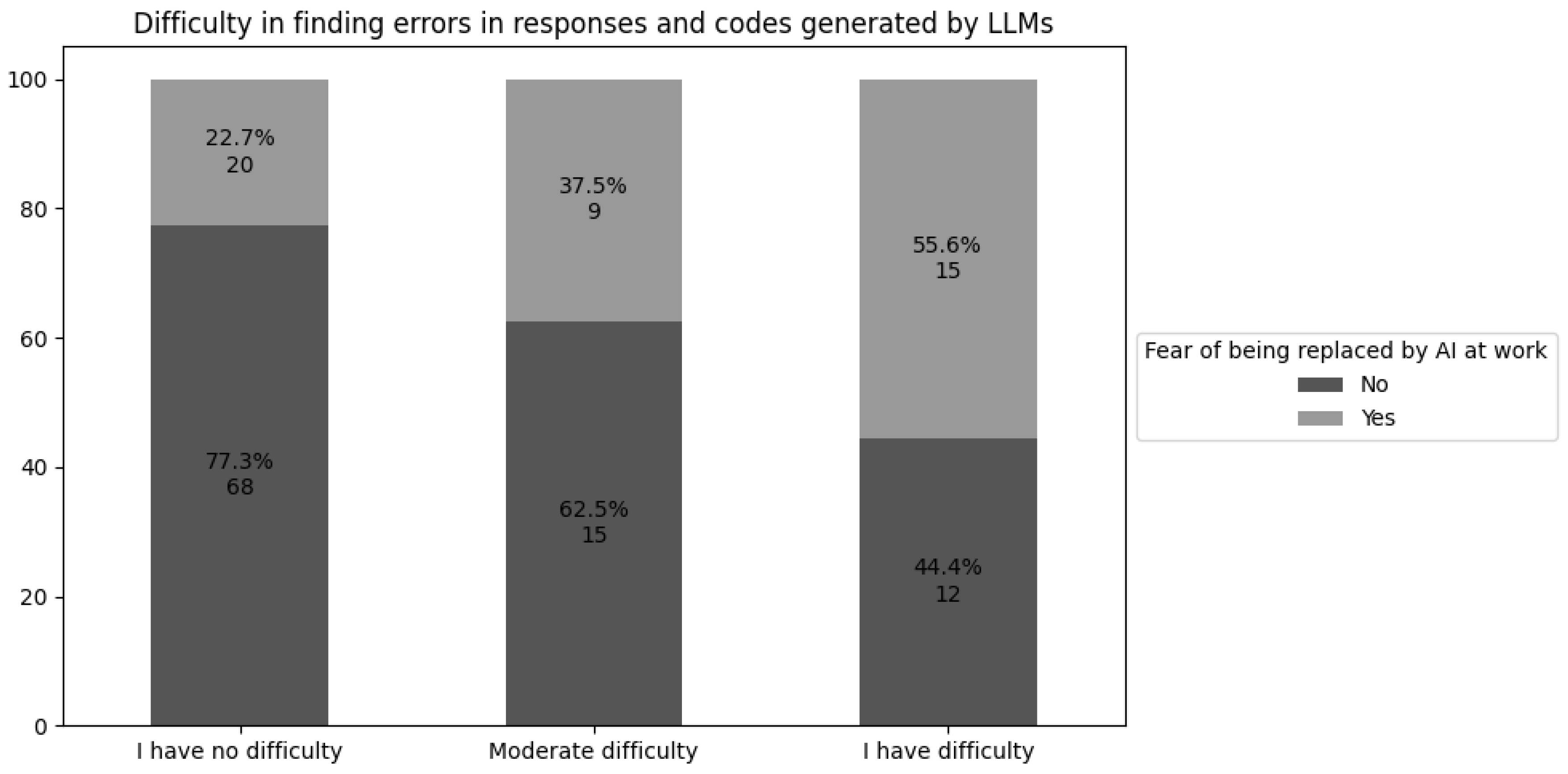

A specific example of this can be seen in the difficulty some students have in identifying errors in code generated by LLMs. This difficulty suggests a superficial understanding of programming logic, which directly impacts their perceived competence. As a result, over half of these students report concern about their future careers. In contrast, students who are able to detect and correct such errors tend to perceive GenAI not as a replacement, but as a collaborative tool that can enhance the software development process [Tu et al. 2024; Marrone et al. 2024].

4.2. Rethinking Evidence: Machine Learning and the Replicability Challenge in Cognitive and Behavioral Neuroscience

The increasing integration of ML algorithms into psychometric and educational research has expanded the analytical scope of these fields, enabling the identification of latent patterns in complex, multifactorial datasets [Sarker 2021]. In this study, such an approach was applied to a dataset composed of previously validated psychometric scales, aiming to investigate the psychological impact of GenAI, such as technology anxiety. Rather than relying solely on traditional confirmatory statistical methods, the unsupervised learning algorithm K-means was used — a widely adopted technique for data segmentation [Ahmed et al. 2020].

This methodological choice reflects a paradigm shift: instead of testing predefined hypotheses based on rigid constructs, the use of K-means enabled a flexible, data-driven organization of students’ responses. This approach uncovered emergent psychological profiles based on patterns of technological anxiety, learning strategies, and familiarity with LLMs. Thus, the algorithm served as an alternative to traditional factor analysis, exploring how students internally structure their experiences within AI-mediated learning environments.

Nonetheless, as extensively discussed in the cognitive neuroscience and psychological sciences literature, the adoption of ML techniques is not without challenges — particularly with respect to reproducibility, statistical validity, and overfitting risks [McDermott et al. 2019; Szucs & Ioannidis 2017; Cumming 2008]. ML models such as K-means can be highly sensitive to input parameters — including the predefined number of clusters — and may be influenced by sample biases. To mitigate these issues, the present study employed the Elbow Method to determine the optimal number of clusters, offering a practical way to reduce intra-cluster inertia and promote more stable findings.

Furthermore, the convergence of ML and cognitive-behavioral modeling opens new avenues for building predictive systems that are not only statistically robust but also theoretically grounded and ethically interpretable [Franco 2021]. As this study shows, ML does not replace classical psychometrics but complements it. When applied with theoretical rigor, ethical oversight, and methodological transparency, ML can enhance the precision, generalizability, and depth of educational and psychological research [Franco 2021; Orrù et al. 2020].