Submitted:

19 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- to develop a coupled heat and mass transfer model for predicting the micro-environment.

- to determine acceptable macro-environment for obtaining associated range of the relaxing control.

- to train an ANN model for real-time conformity monitoring of the micro-environment.

2. Methodology

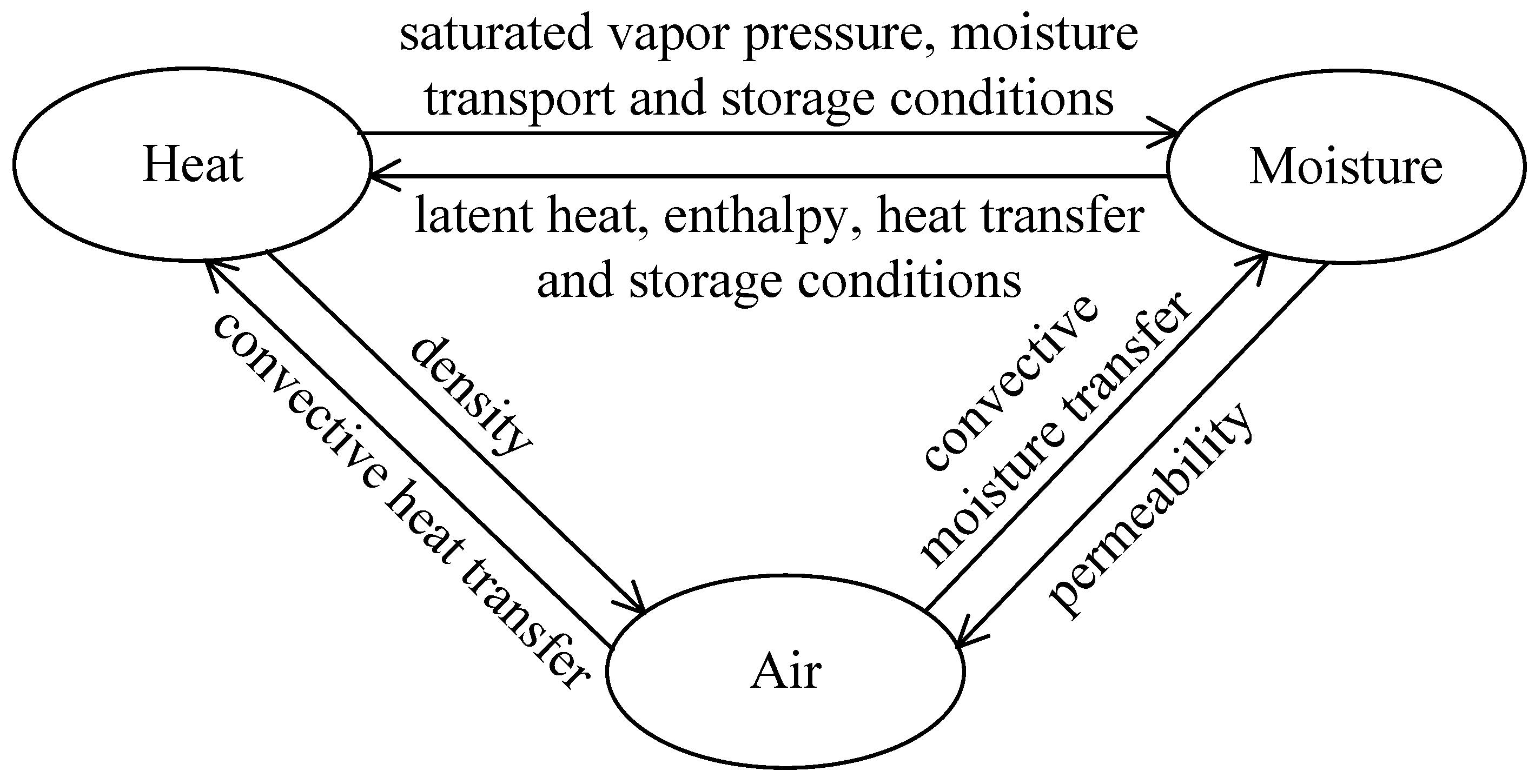

2.1. Numerical Simulation of Heat and Mass Transfer

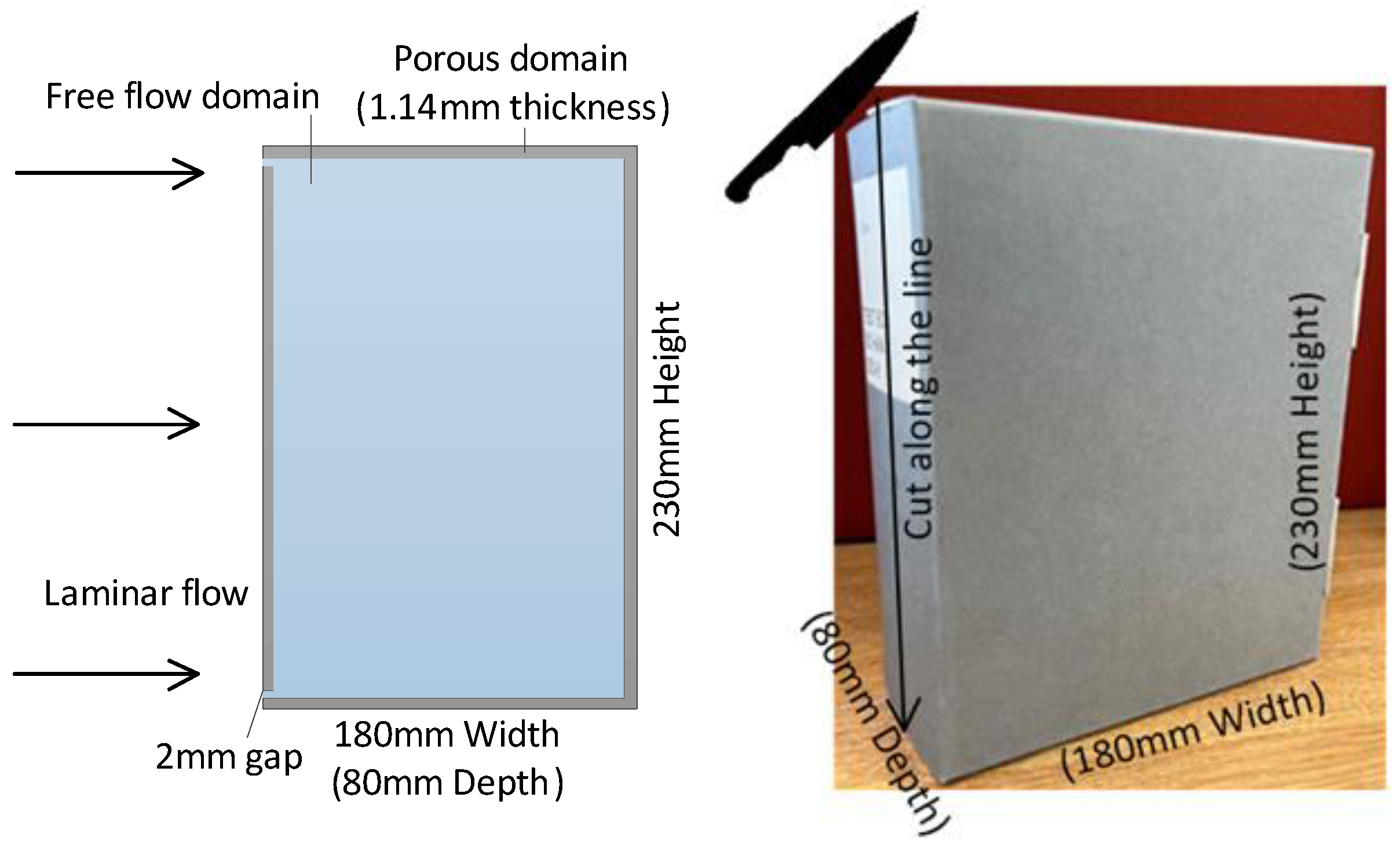

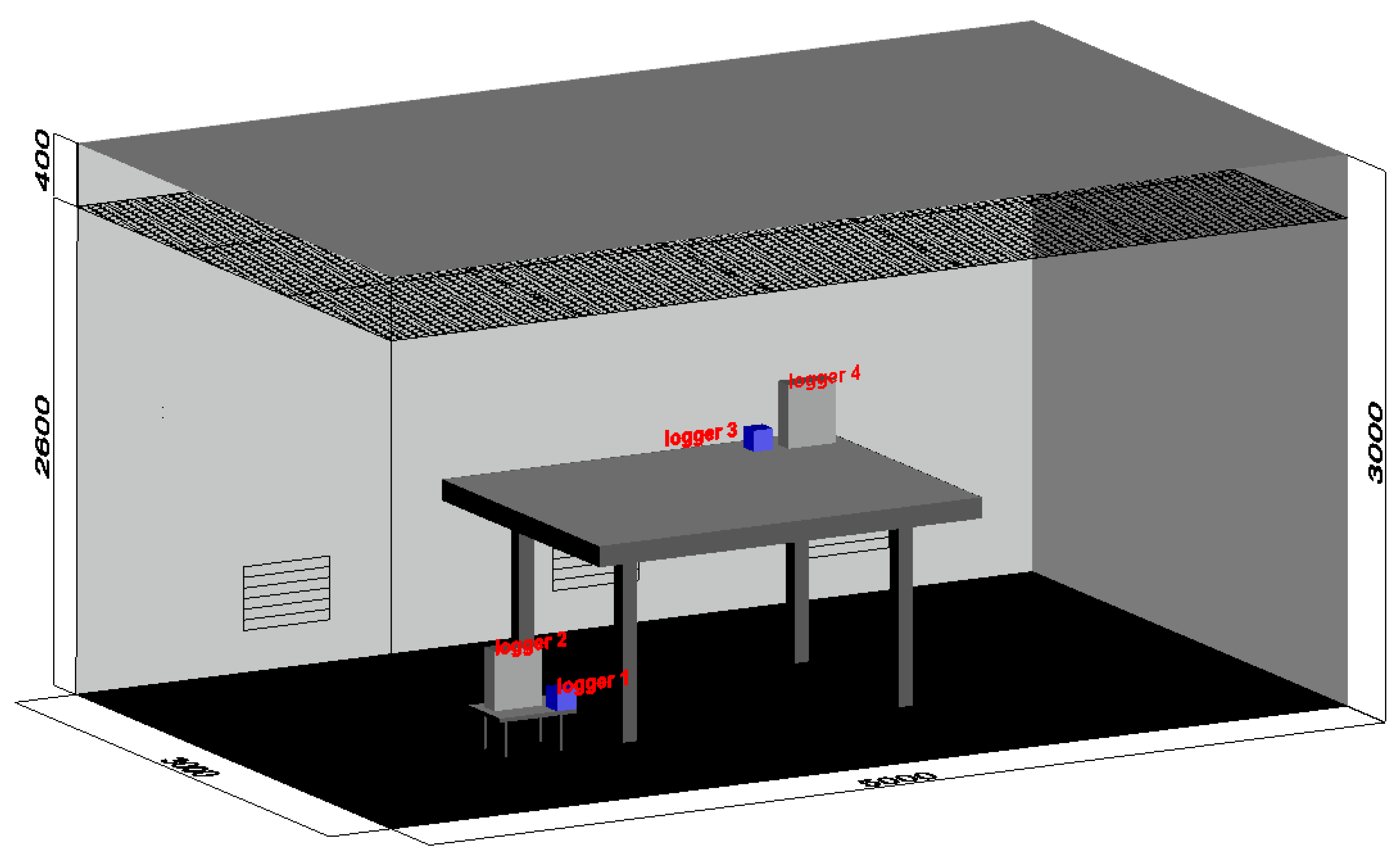

2.1.1. Model Setting

2.1.2. Model Validation

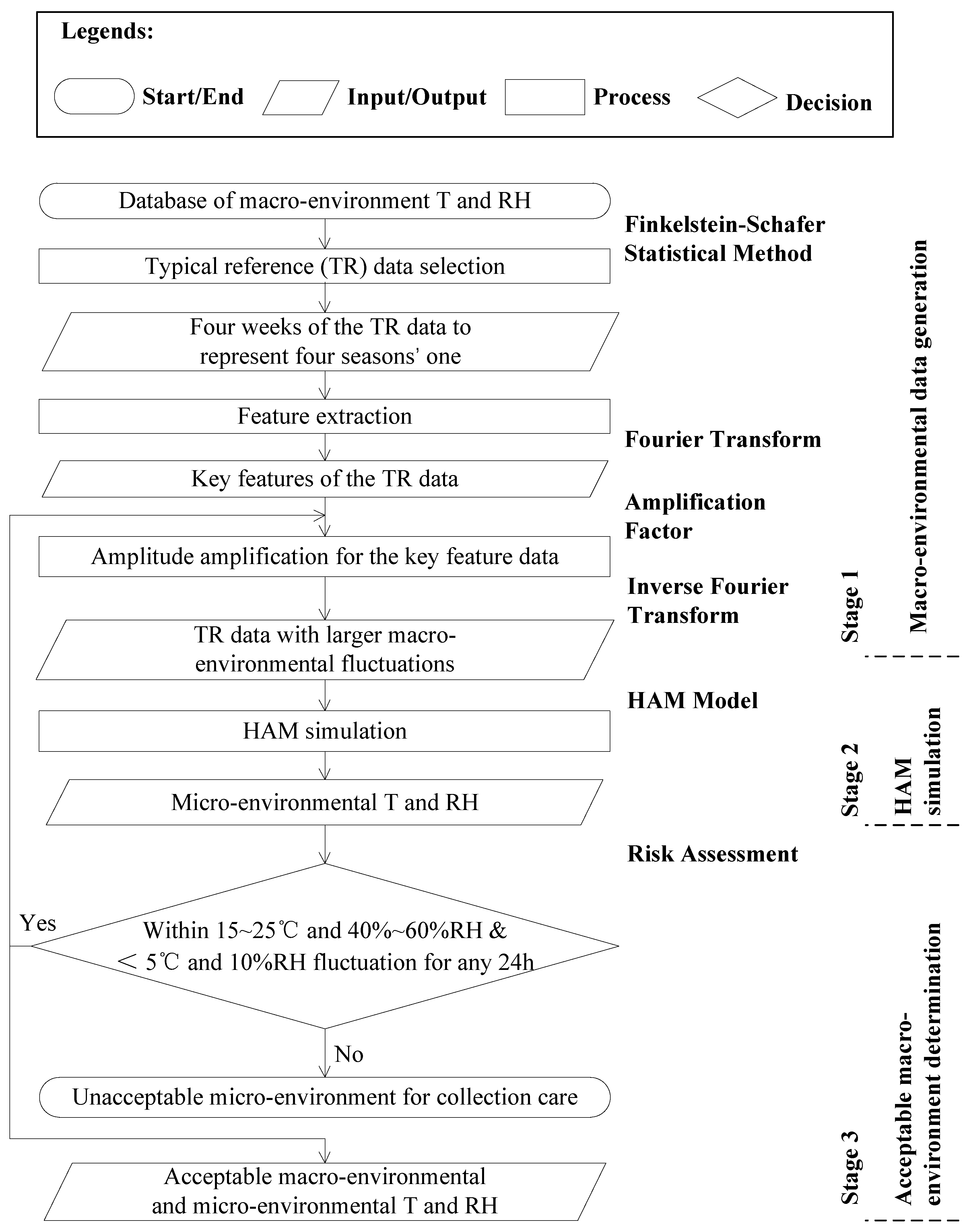

2.2. Determination of Acceptable Macro-Environment

2.2.1. Typical Reference Data Selection

2.2.2. Data Amplification

2.2.3. Determination Process of Acceptable Macro-Environment

2.3. ANN Modelling

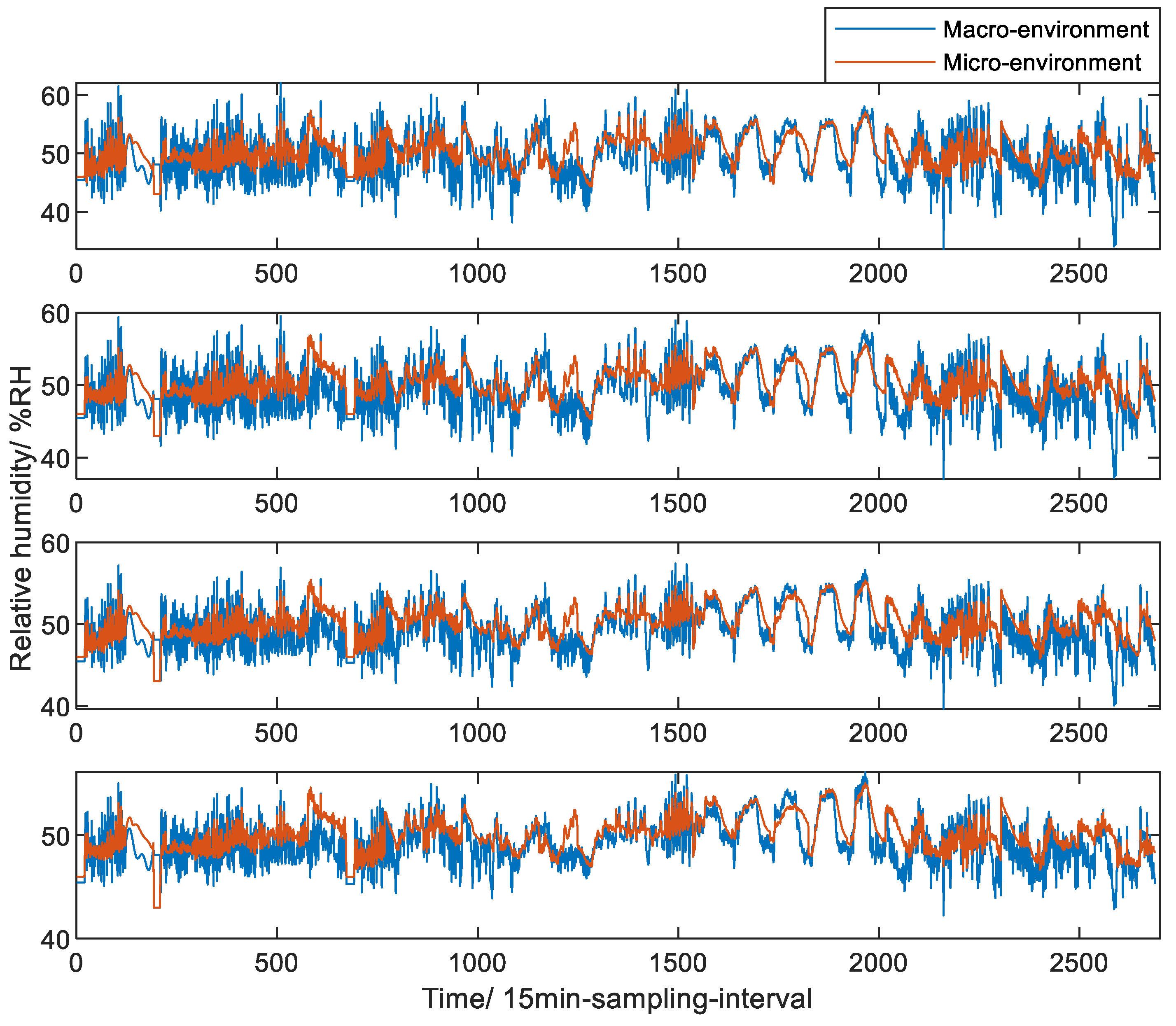

2.3.1. Data Preparation

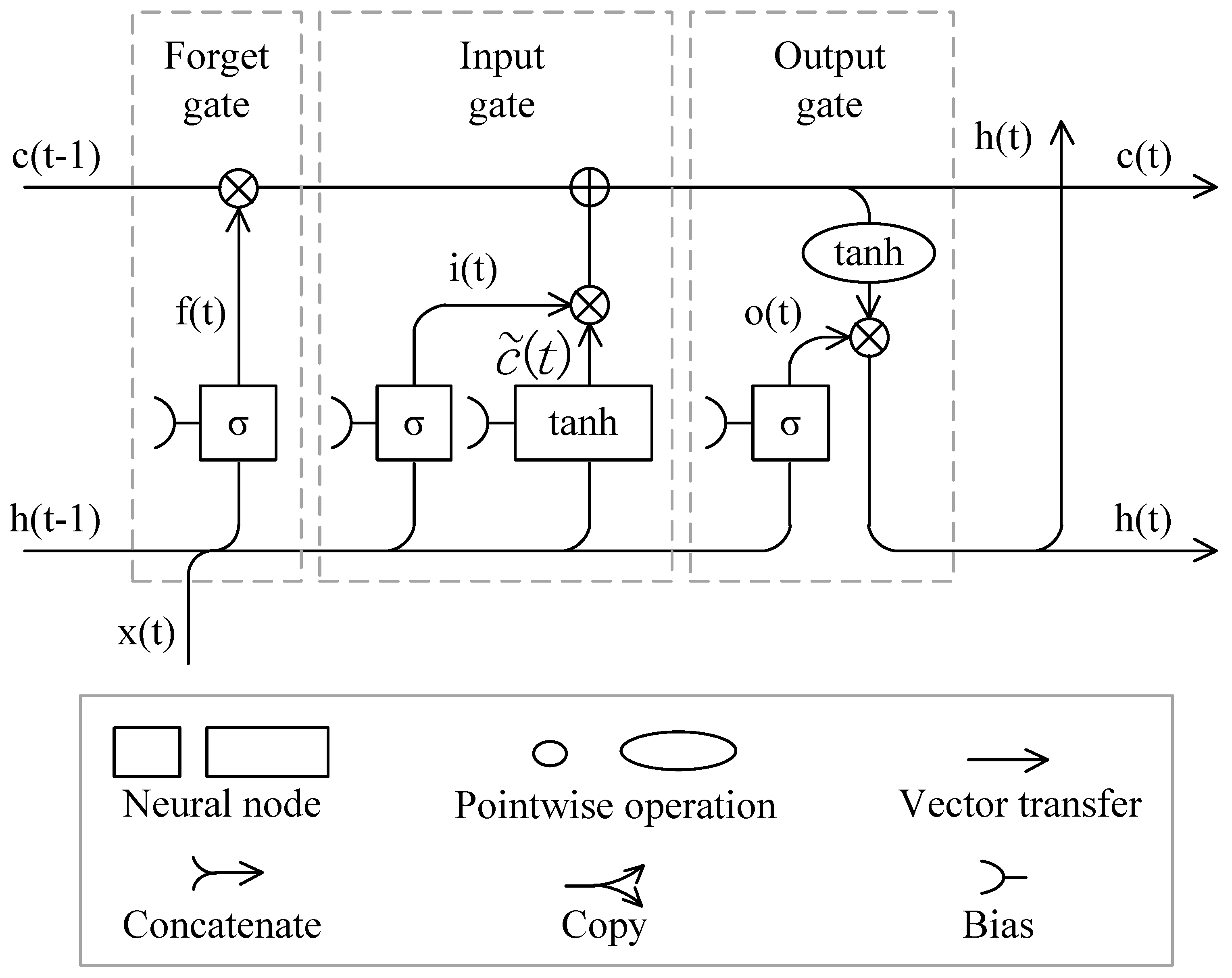

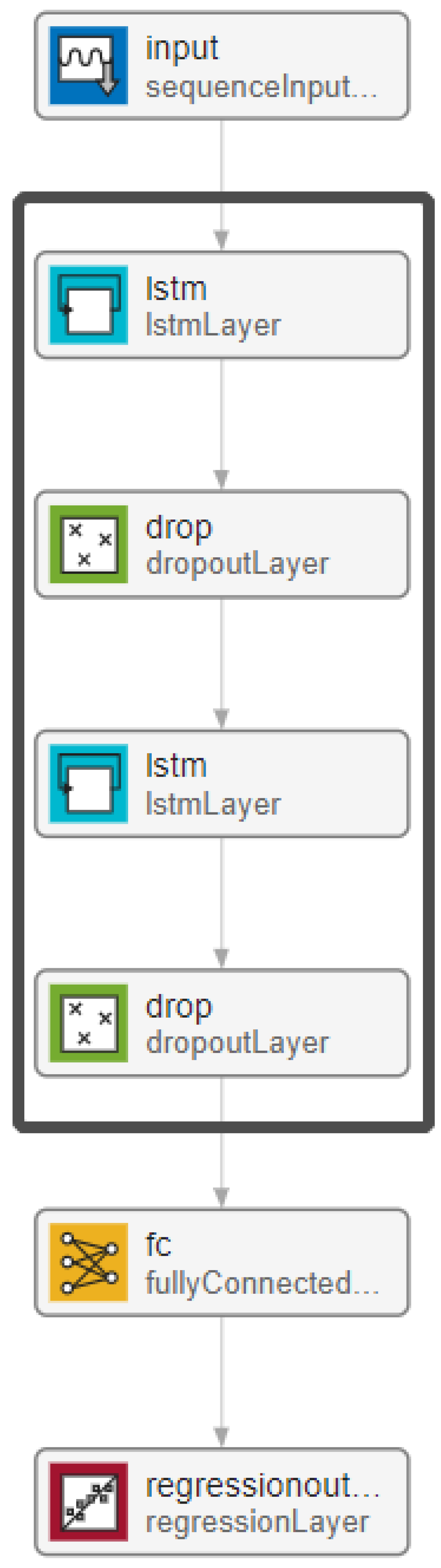

2.3.2. Architecture of the ANN

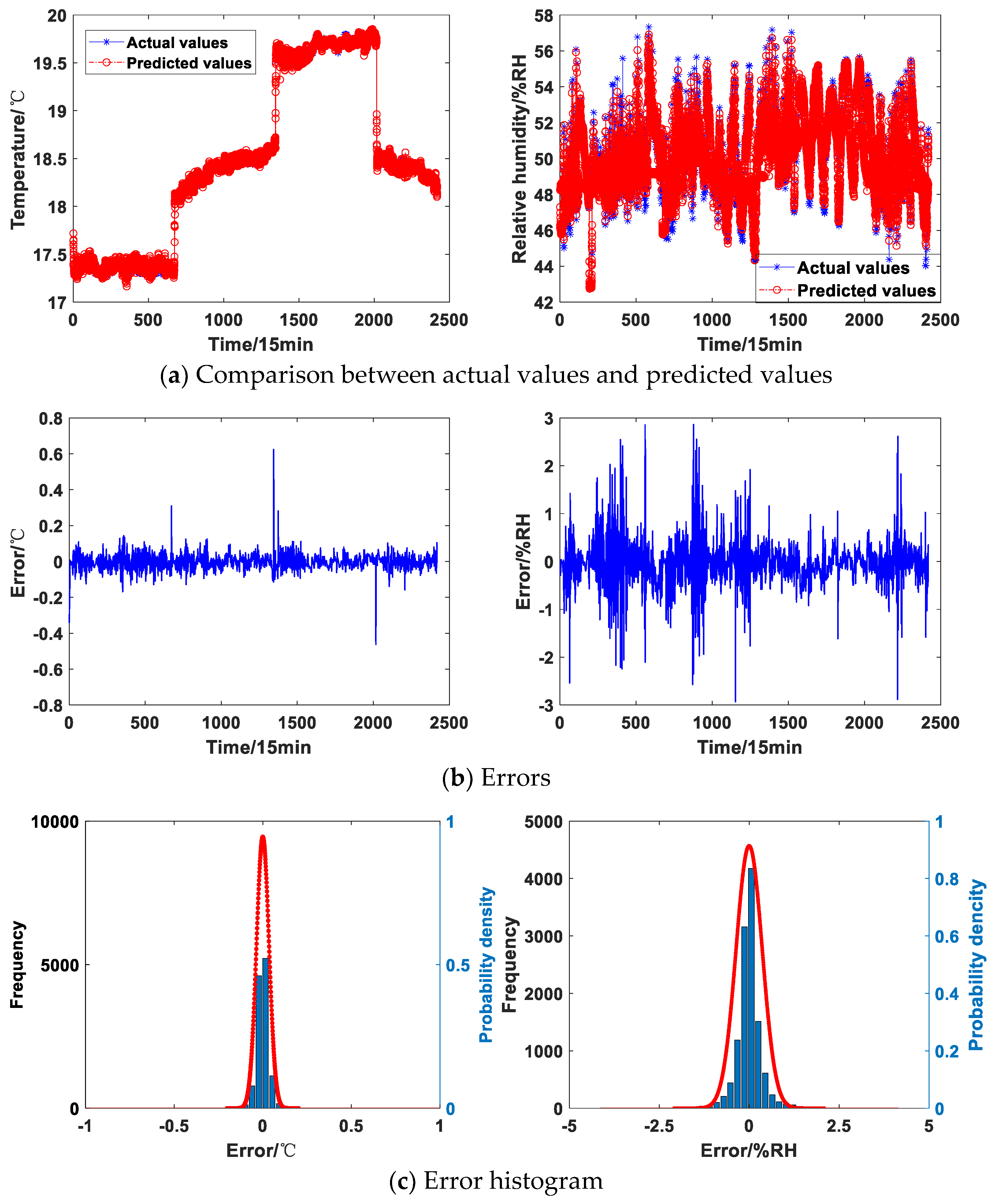

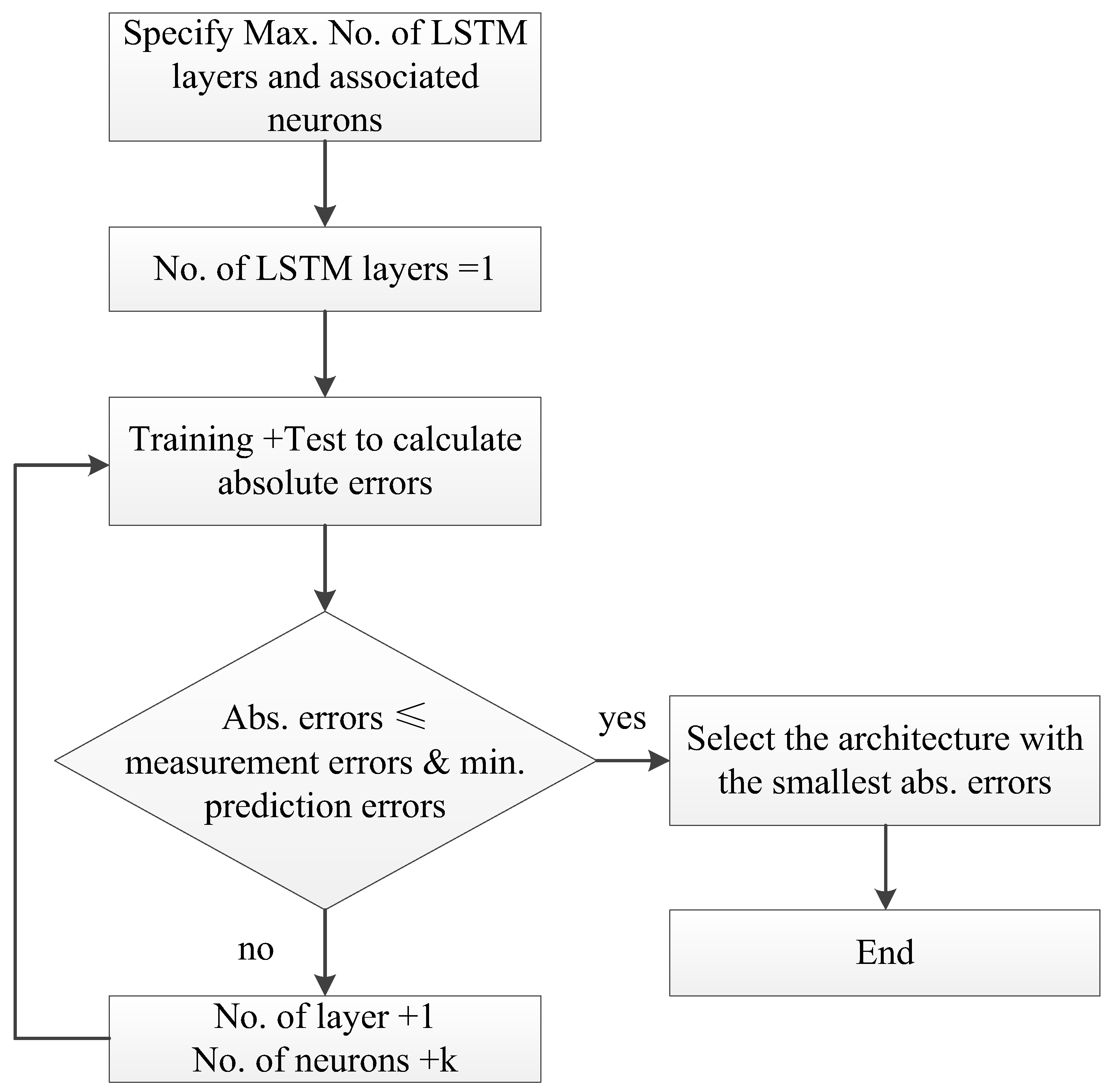

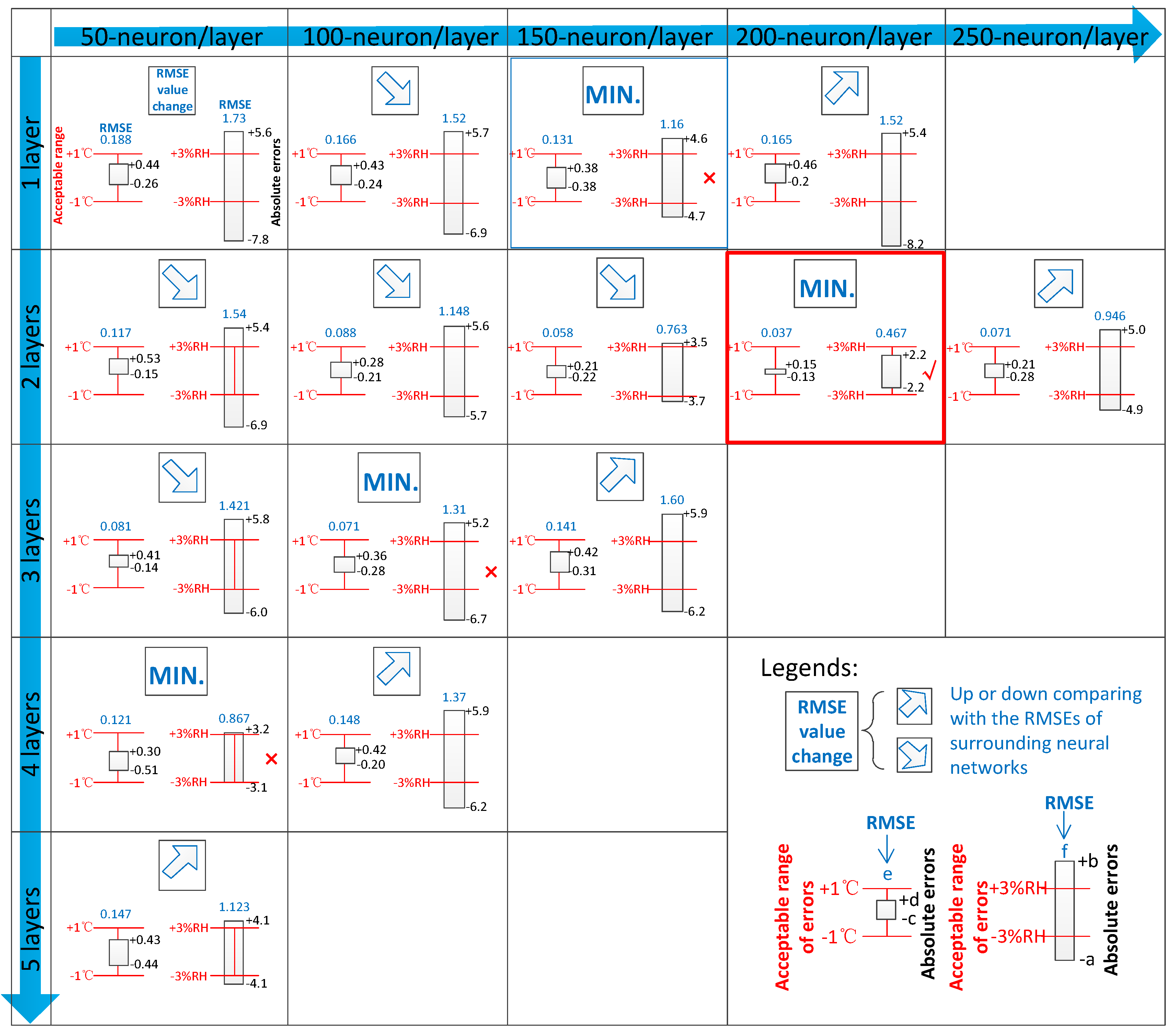

2.3.3. Evaluation of the Optimal LSTM Network

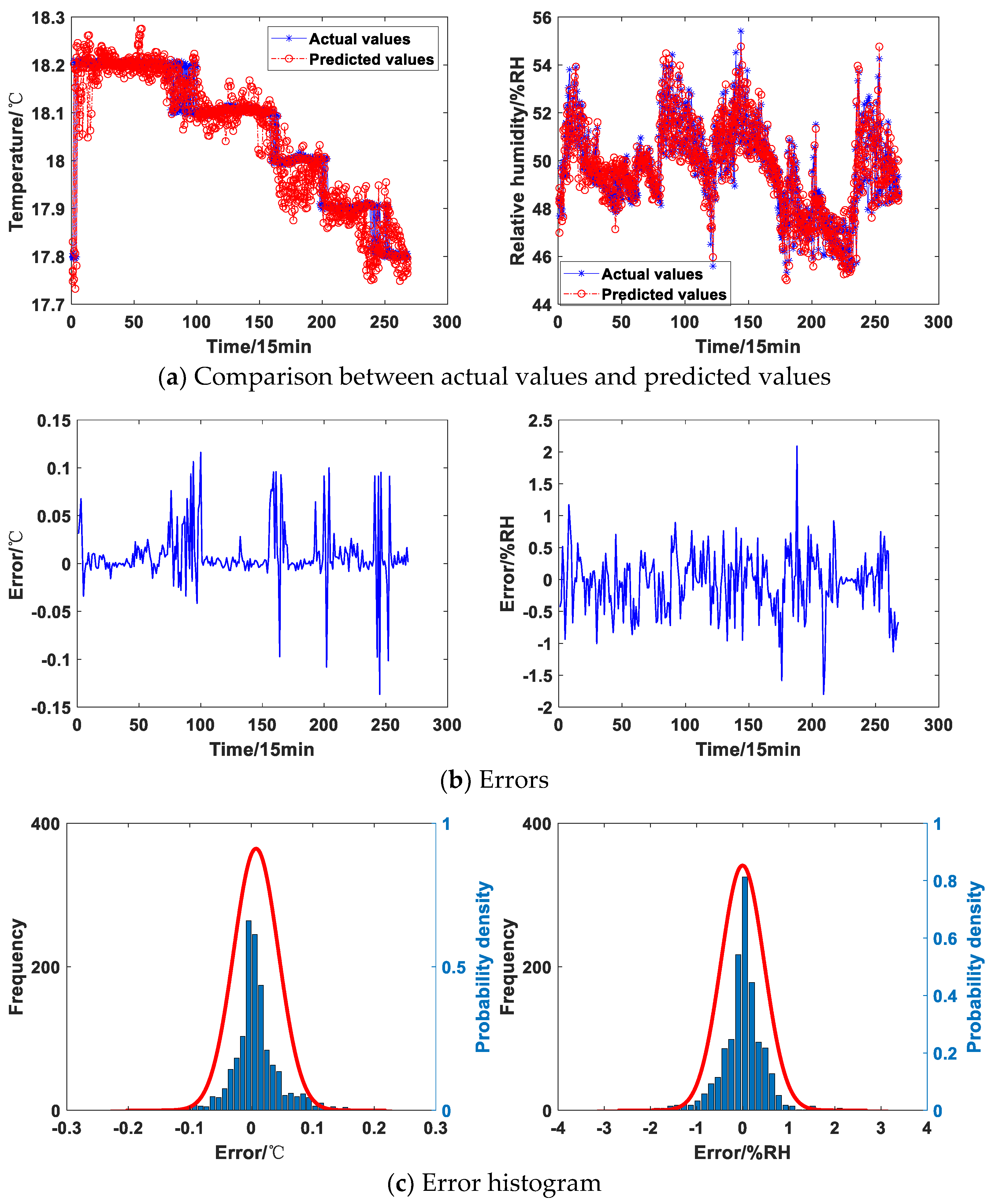

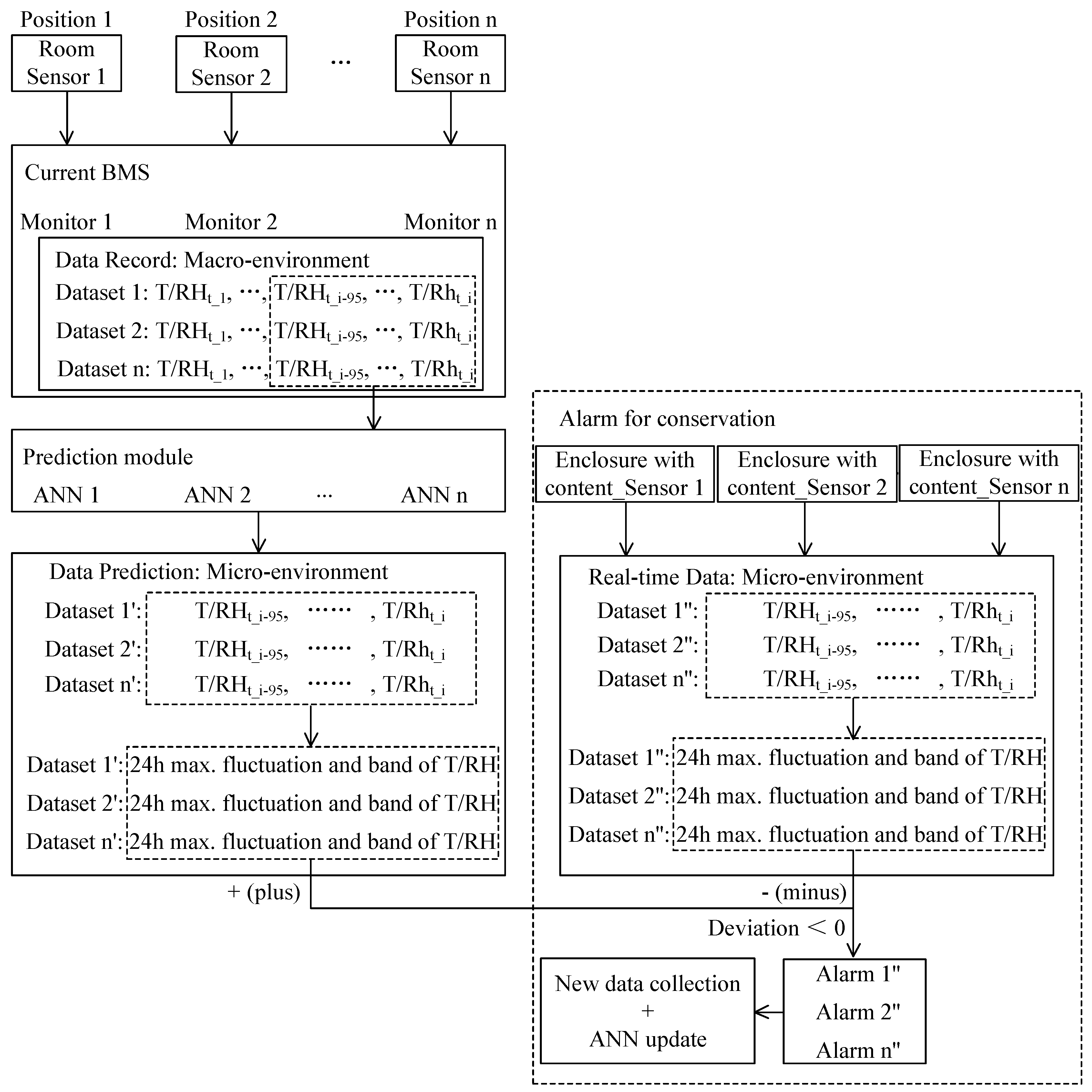

2.3.4. Practical Application of Real-Time Conformity Monitoring

Validation Experiment

Parallel Prediction

3. Results and Discussion

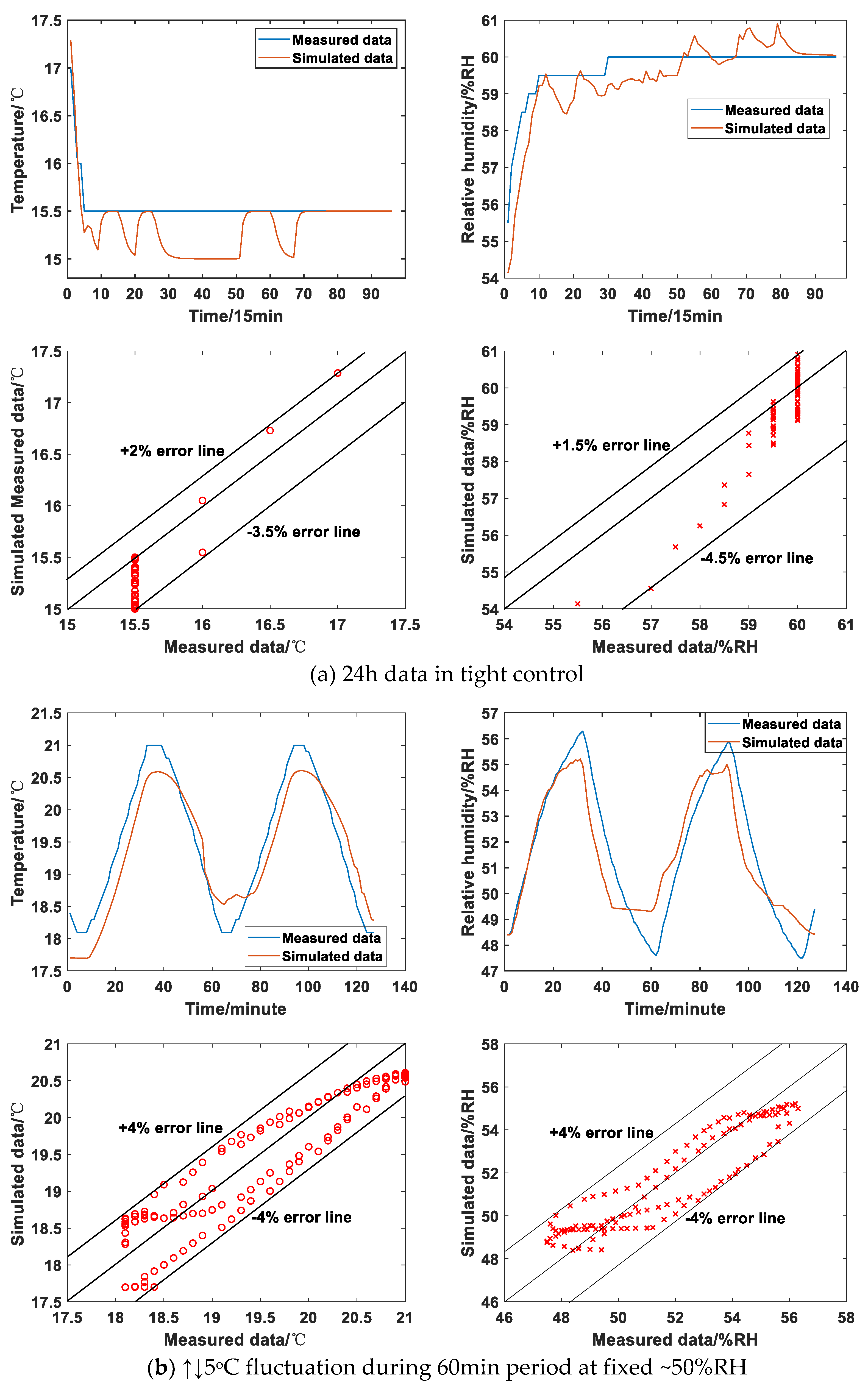

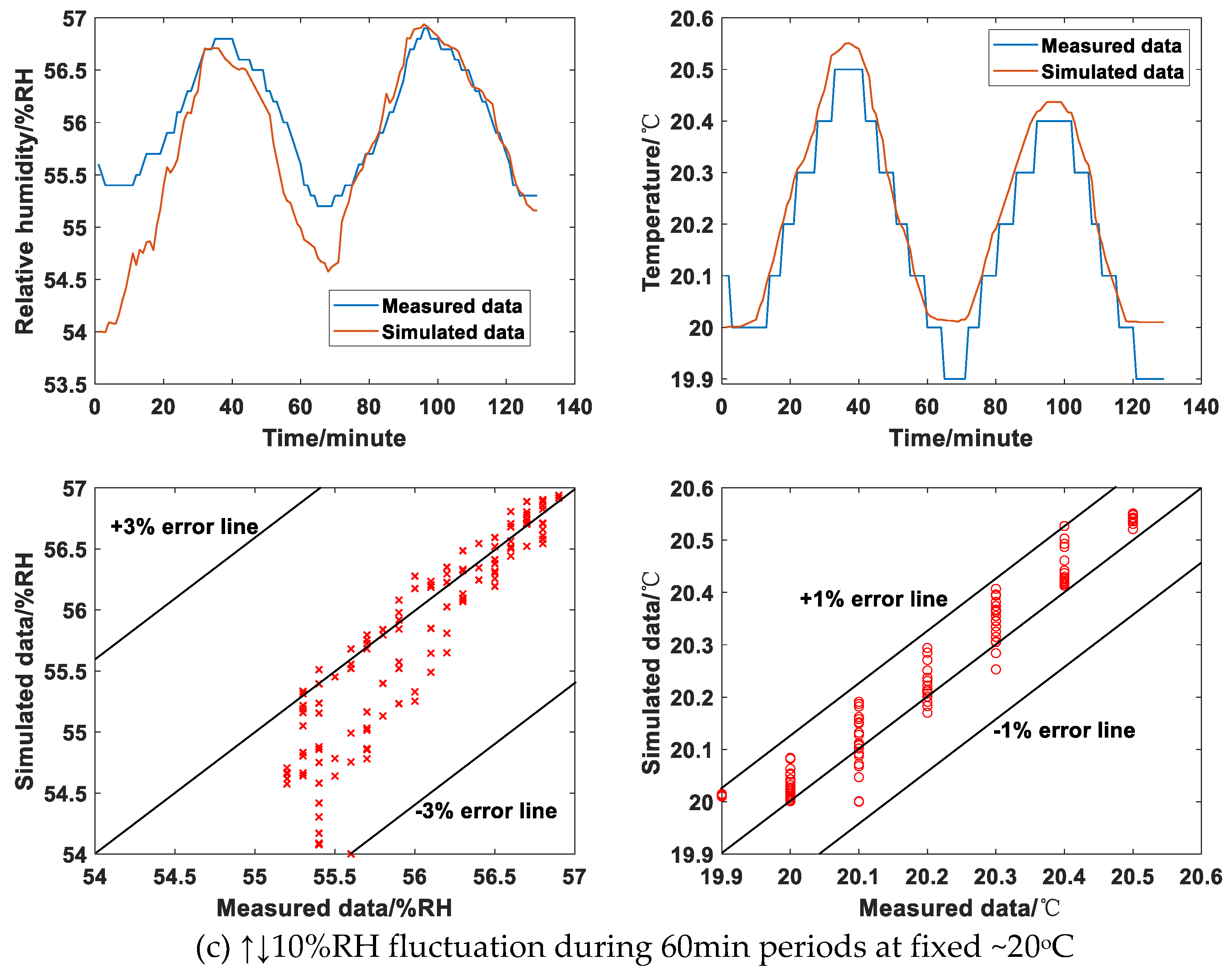

3.1. Comparison of Measured and Simulated Data in Heat and Mass Simulation

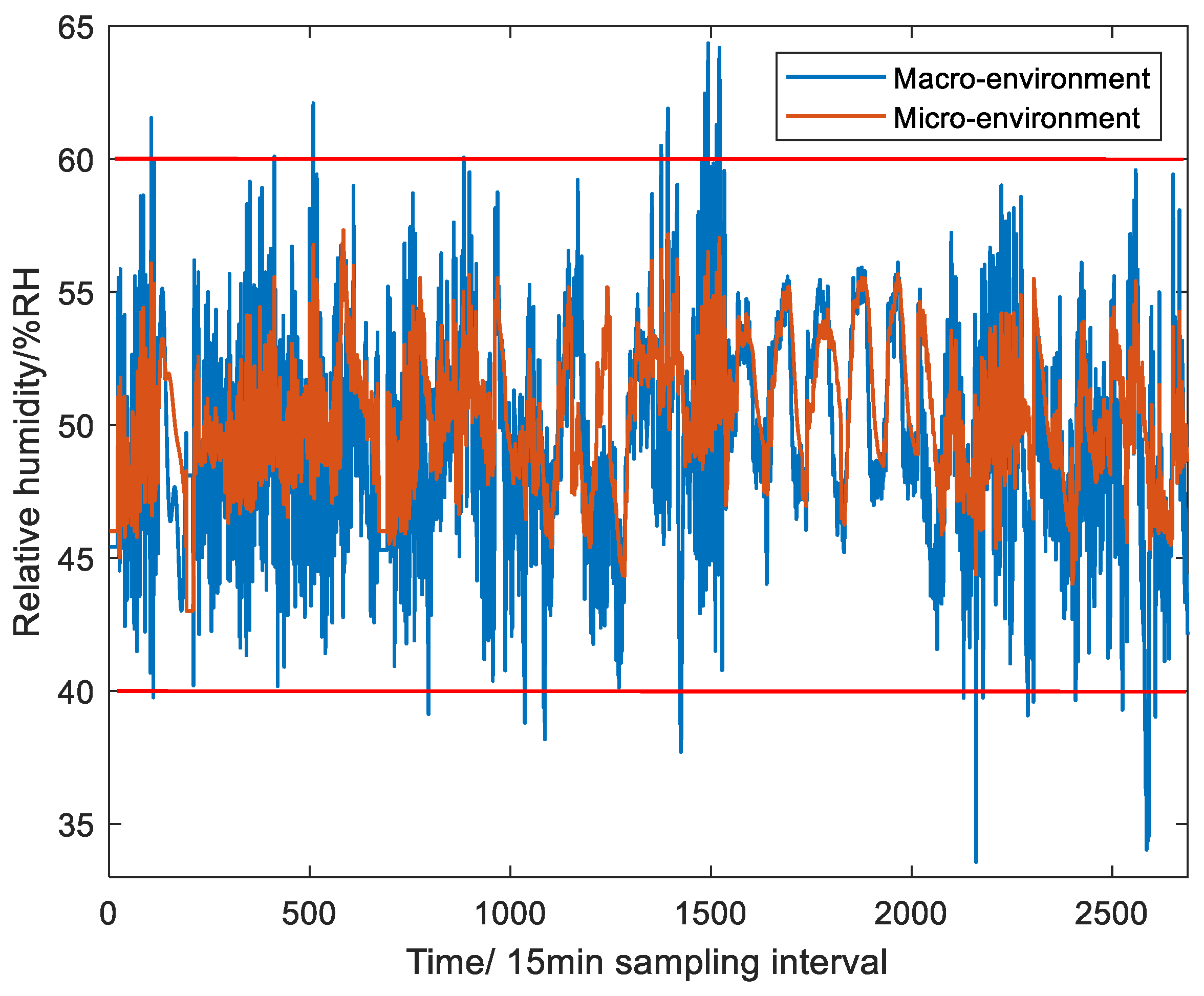

3.2. Acceptable Macro-Environment

3.3. Real-Time Prediction of Micro-Environment

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muñoz-Viñas, S. (2012). Contemporary theory of conservation. Routledge.

- Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Chen, Q., Lei, Y., & Tang, K. (2025). Identification, deterioration, and protection of organic cultural heritages from a modern perspective. Heritage Science, 13(1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Elnaggar, A., Said, M., Kraševec, I., Said, A., Grau-Bove, J., & Moubarak, H. (2024). Risk analysis for preventive conservation of heritage collections in Mediterranean museums: case study of the museum of fine arts in Alexandria (Egypt). Heritage Science, 12(1), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S., Wang, F., & Browne, M. (2019). Comparative methods to assess renovation impact on indoor hygrothermal quality in a historical art gallery. Indoor and Built Environment, 28(4), 492-505. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., & Ganguly, S. (2015). Effects of Renovation Solutions in a Historical Building of Cultural Significance.

- Fernandez-Cortes, A., Palacio-Perez, E., Martin-Pozas, T., Cuezva, S., Ontañon, R., Lario, J., & Sanchez-Moral, S. (2025). Defining the Optimal Ranges of Tourist Visits in UNESCO World Heritage Caves with Rock Art: The Case of El Castillo and Covalanas (Cantabria, Spain). [CrossRef]

- Harrestrup, Maria, and Svend Svendsen. “Internal insulation applied in heritage multi-storey buildings with wooden beams embedded in solid masonry brick façades.” Building and environment 99 (2016): 59-72. [CrossRef]

- Shiner, J. (2007). Trends in microclimate control of museum display cases. Museum Microclimates, 267-275.

- Cao, S., Ge, W., Yang, Y., Huang, Q., & Wang, X. (2022). High strength, flexible, and conductive graphene/polypropylene fiber paper fabricated via papermaking process. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C., Mark, L. H., Chang, E., Chu, R. K., Lee, P. C., & Park, C. B. (2020). Highly expanded, highly insulating polypropylene/polybutylene-terephthalate composite foams manufactured by nano-fibrillation technology. Materials & Design, 188, 108450. [CrossRef]

- Jose, J., Thomas, V., Raj, A., John, J., Mathew, R. M., Vinod, V., ... & Mujeeb, A. (2020). Eco-friendly thermal insulation material from cellulose nanofibre. Journal of Applied Polymer Science, 137(2), 48272. [CrossRef]

- Gane, P. A., & Ridgway, C. J. (2009). Moisture pickup in calcium carbonate coating structures: role of surface and pore structure geometry. Nordic Pulp & Paper Research Journal, 24(3), 298-308. [CrossRef]

- Derluyn, H., Janssen, H., Diepens, J., Derome, D., & Carmeliet, J. (2007). Hygroscopic behavior of paper and books. Journal of Building Physics, 31(1), 9-34. [CrossRef]

- Han, B., Li, X., Wang, F., Bon, J., & Symonds, I. (2024). The buffering effect of a paper-based storage enclosure made from functional materials for preventive conservation. Indoor and Built Environment, 33(1), 167-182. [CrossRef]

- Perino, M. (2018). Air tightness and RH control in museum showcases: Concepts and testing procedures. Journal of Cultural Heritage, 34, 277-290. [CrossRef]

- van Schijndel, A. W. M. (2007). Integrated heat air and moisture modeling and simulation.

- Simonson, C. J., Salaonvaara, M., & Ojanen, T. (2004). Heat and mass transfer between indoor air and a permeable and hygroscopic building envelope: part II–verification and numerical studies. Journal of Thermal Envelope and Building Science, 28(2), 161-185. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W., Chen, Y., Bao, Y., & Fang, A. (2020). A validation of dynamic hygrothermal model with coupled heat and moisture transfer in porous building materials and envelopes. Journal of Building Engineering, 32, 101484. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., & Abbassi, H. (2018). 1D/3D transient HVAC thermal modeling of an off-highway machinery cabin using CFD-ANN hybrid method. Applied Thermal Engineering, 135, 406-417. [CrossRef]

- Darvishvand, L., Safari, V., Kamkari, B., Alamshenas, M., & Afrand, M. (2022). Machine learning-based prediction of transient latent heat thermal storage in finned enclosures using group method of data handling approach: a numerical simulation. Engineering Analysis with Boundary Elements, 143, 61-77. [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, S., Ahmed, A., & Wang, F. (2020). Optimised building energy and indoor microclimatic predictions using knowledge-based system identification in a historical art gallery. Neural Computing and Applications, 32(8), 3349-3366. [CrossRef]

- Steeman, H. J., Van Belleghem, M., Janssens, A., & De Paepe, M. (2009). Coupled simulation of heat and moisture transport in air and porous materials for the assessment of moisture related damage. Building and Environment, 44(10), 2176-2184. [CrossRef]

- CEN, E. (2007). 15026: Hygrothermal Performance of Building Components and Building Elements–Assessment of Moisture Transfer by Numerical Simulation. CEN, Brussels, Belgium.

- Tariku, F., Kumaran, K., & Fazio, P. (2010). Transient model for coupled heat, air and moisture transfer through multilayered porous media. International journal of heat and mass transfer, 53(15-16), 3035-3044. [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Zhang, C., Xu, X., Yu, J., Wang, F., Gang, W., & Wang, J. (2022, July). Simulation study of a dual-cavity window with gravity-driven cooling mechanism. In Building Simulation (pp. 1-14). Tsinghua University Press. [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. (2020). A rational performance criterion for hydrological model. Journal of Hydrology, 590, 125488. [CrossRef]

- Knoben, W. J., Freer, J. E., & Woods, R. A. (2019). Inherent benchmark or not? Comparing Nash–Sutcliffe and Kling–Gupta efficiency scores. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 23(10), 4323-4331.

- Lee, K., Yoo, H., & Levermore, G. J. (2010). Generation of typical weather data using the ISO Test Reference Year (TRY) method for major cities of South Korea. Building and Environment, 45(4), 956-963. [CrossRef]

- International Organization for Standardization (2005). ISO 15927–4: Hourly data for assessing the annual energy use for heating and cooling. ISO, Geneva,Switzerland.

- Grass, A. M., & Gibbs, F. A. (1938). A Fourier transform of the electroencephalogram. Journal of neurophysiology, 1(6), 521-526.

- Sanei, S., & Chambers, J. A. (2013). EEG signal processing. John Wiley & Sons.

- Sawant, H. K., & Jalali, Z. (2010). Detection and classification of EEG waves. Oriental Journal of Computer Science and Technology, 3(1), 207-213.

- Nussbaumer, H. J., & Nussbaumer, H. J. (1982). The fast Fourier transform (pp. 80-111). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- British Standards Institution. (2012). Specification for Managing Environmental Conditions for Cultural Collections: PAS 198: 2012. British Standards Limited.

- Qiao, D., Li, P., Ma, G., Qi, X., Yan, J., Ning, D., & Li, B. (2021). Realtime prediction of dynamic mooring lines responses with LSTM neural network model. Ocean Engineering, 219, 108368. [CrossRef]

- Granata, F., Di Nunno, F., & de Marinis, G. (2022). Stacked machine learning algorithms and bidirectional long short-term memory networks for multi-step ahead streamflow forecasting: A comparative study. Journal of Hydrology, 613, 128431.

- Arslan, N., & Sekertekin, A. (2019). Application of Long Short-Term Memory neural network model for the reconstruction of MODIS Land Surface Temperature images. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics, 194, 105100. [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S., & Schmidhuber, J. (1997). Long short-term memory. Neural computation, 9(8), 1735-1780.

- Yu, Y., Si, X., Hu, C., & Zhang, J. (2019). A review of recurrent neural networks: LSTM cells and network architectures. Neural computation, 31(7), 1235-1270. [CrossRef]

- Gal, Y., & Ghahramani, Z. (2016). A theoretically grounded application of dropout in recurrent neural networks. Advances in neural information processing systems, 29.

- Srivastava, N., Hinton, G., Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Salakhutdinov, R. (2014). Dropout: a simple way to prevent neural networks from overfitting. The journal of machine learning research, 15(1), 1929-1958.

- Ma, W., & Lu, J. (2017). An equivalence of fully connected layer and convolutional layer. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.01252.

- Muppidi, S., & PG, O. P. (2023). Dragonfly political optimizer algorithm-based rider deep long short-term memory for soil moisture and heat level prediction in iot. The Computer Journal, 66(6), 1350-1365. [CrossRef]

- Song, W., Gao, C., Zhao, Y., & Zhao, Y. (2020). A time series data filling method based on LSTM—Taking the stem moisture as an example. Sensors, 20(18), 5045.

- Jabbar, H., and Rafiqul Zaman Khan. “Methods to avoid over-fitting and under-fitting in supervised machine learning (comparative study).” Computer Science, Communication and Instrumentation Devices 70 (2015): 163-172.

- Bilbao, I., & Bilbao, J. (2017, December). Overfitting problem and the over-training in the era of data: Particularly for Artificial Neural Networks. In 2017 eighth international conference on intelligent computing and information systems (ICICIS) (pp. 173-177). IEEE.

- Althelaya, K. A., El-Alfy, E. S. M., & Mohammed, S. (2018, April). Evaluation of bidirectional LSTM for short-and long-term stock market prediction. In 2018 9th international conference on information and communication systems (ICICS) (pp. 151-156). IEEE.

- Perles, A., Fuster-López, L., & Bosco, E. (2024). Preventive conservation, predictive analysis and environmental monitoring. Heritage Science, 12(1), 11. [CrossRef]

| Description | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| ① Carboard material | ||

| Density | 662 | kg/m³ |

| Thermal conductivity | 0.055 | W/(m·K) |

| Heat capacity at constant pressure | 1.028 | J/(kg·K) |

| Diffusion coefficient | 1.49E-10 | m²/s |

| Water content | kg/m³ | |

| Vapor resistance factor | 95.63 | - |

| ② Boundary condition | ||

| Laminar air flow | 0.2 | m/s |

| Temperature | Macro-environmental temperature | oC |

| RH | Macro-environmental RH | %RH |

| Upper and lower gaps of the enclosure | open boundary | - |

| Initial conditions | ||

| Temperature and RH in both domains | Macro-environmental temperature and RH at the first second |

oC and %RH |

| Velocity in both domains | 0.2 | m/s |

| Pressure in both domains | (Ambient pressure – reference pressure) | Pa |

| ③ Meshing | ||

| Element types | triangular or quadrilateral | - |

| No. of layers in porous media | 2~4 | - |

| Mesh density | dense in the porous domain and gradually course toward the centre of free flow domain | - |

| Maximum element growth rate | 1.05 | - |

| Maximum curvature factor | 0.2 | - |

| ④ Solver | ||

| Time stepping | second-order BDF | - |

| Maximum step | 0.25 | h |

| Solving method | automatic Newton | - |

| tolerance factor | 0.01 | - |

| maximum No. of iterations | 4 | - |

| Level | 24h Fluctuation (band) in macro-environment | 24h Fluctuation (band) in micro-environment | Amplification factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ±10 (42.2~56.1) %RH | ±7.1 (45.5~55) %RH | 10 |

| 2 | ±12 (39.6~57.4) %RH | ±7.9 (44.7~55.4) %RH | 11.6 |

| 3 | ±14 (37~59.4) %RH | ±8.1 (43.8~56.8) %RH | 13.4 |

| 4 | ±16 (33~65) %RH | ±9.1 (43~57.3) %RH | 15 |

| Tigh-control | ↑↓5oC @50%RH | ↑↓10%RH @20oC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| KGE for temp. | 0.51 | 0.84 | 0.97 |

| KGE for RH | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.63 |

|

| R2 | RMSE | MSE | MAE | StD | |

| Training data (temperature) | 0.999 | 0.035 | 0.001 | 0.023 | 0.035 |

| Training data (RH) | 0.984 | 0.364 | 0.132 | 0.230 | 0.364 |

| Testing data (temperature) | 0.965 | 0.037 | 0.001 | 0.025 | 0.037 |

| Testing data (RH) | 0.963 | 0.468 | 0.219 | 0.313 | 0.468 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).