1. Introduction

The constraints related to the difficulties of carrying out activities in mountain areas, especially in Southeastern Europe, require sustainable decisions and actions that support these regions. The economy of mountainous areas, practiced under harsh conditions, is difficult to sustain and faces persistent demographic decline. All sectors and fields of the mountain economy are slow to develop compared to other regions. Mountain entrepreneurship follows the same pattern as the mountain economy, and the construction sector — present across the primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary sectors — is not detached from the other domains of high-altitude areas.

In a study conducted by a team of researchers from Portugal on mountain entrepreneurship in Southern Europe, spatially contextualized across five Mediterranean countries, some active entrepreneurs considered that the main factors that ensure sustainability or hinder business development are focused on disadvantageous realities. The study’s findings highlight the need to promote and support non-agricultural activities for the development of rural areas, as well as the establishment of recent policy options within the EU framework. Several EU initiatives aim to promote these activities, with the understanding that agriculture can no longer be merely an extension of rural industry, solely responsible for the socio-economic development of rural areas. (Moreira et al., 2000)

Another issue facing mountain construction entrepreneurship is the territorial illegality it often confronts. Some mountain constructions are built illegally, precisely due to the difficulties encountered in these regions. A telling example is Tara Mountain in western Serbia, where for a long period, numerous constructions were carried out without legal authorization. Temporally, as in any post-communist country, there has been a progressive move toward more coherent regulation, evolving from the socialist period to the current era of individual ownership. Spatially, entrepreneurial initiatives in construction have continuously improved, decisively contributing to the quality of life in the Tara Mountains area. There is a thin line between sustainable development and environmental degradation. Recently, local, regional, national, and European communities have been supporting initiatives aligned with the principles of sustainable development. Another important dimension of mountain entrepreneurship in construction is the balance between tourism appeal and practical utility for the local population. (Lukić et al., 2013)

Another relevant area for mountain entrepreneurship is the rural region of Georgia. A shift in policy paradigm can be observed, transitioning from agriculture to rural development, leading to a transformation of household-based economic activities. Mountain regions have become central points for promoting innovative approaches and practices. The reasons for increased focus on the differentiated development of mountainous areas, compared to lowland areas, are multiple, mainly referring to lack of market access, migration, climate change, etc. However, the most critical issue facing mountain entrepreneurship lies in the difficult conditions under which small businesses operate, destabilizing the SME segment — which is crucial for these areas. Many small businesses operate with limited access to necessary resources, making it hard to capitalize on new opportunities and benefits. In the Caucasus region, a reality frequently encountered in other mountainous areas worldwide, a significant influx of external reimbursable or non-reimbursable investments plays a key role in transforming the local landscape and creating previously unavailable services. (Salukvadze et al., 2024)

The construction industry, a key sector in any economy, holds substantial importance for the development of other sectors, particularly in mountainous regions. This industry, sensitive to changes in market conditions, compels entities operating in this field to constantly implement measures to increase competitiveness, including the introduction of innovative solutions. A study on construction entrepreneurship in Poland, conducted on 608 companies, identifies several factors that influence the level of innovation in maintaining firm competitiveness. To cope with investment and territorial challenges, the entrepreneurial environment in construction must be more competitive than in other mountain areas, as well as compared to entrepreneurship in non-mountainous regions. (Staniewski et al., 2016)

In the Netherlands, the construction industry — under considerable pressure due to sustainability requirements — mobilizes entrepreneurship by introducing new products and innovative business practices. As in most mountain countries, construction entrepreneurship is under pressure from the innovation imperative, which has become increasingly necessary in recent times. (Klein, 2010)

Another study indicates that, amid accelerated technological development in the construction field, mountain entrepreneurship has experienced exponential growth in recent years. However, the “flip side of the coin” is also evident in this field. Unemployment increasingly affects many sectors of national economies, and indirectly, the global economy. The construction sector was among the first to be impacted by the automation of economic activities. Additionally, construction entrepreneurship faces significant challenges due to a lack of financial resources, difficulties in teamwork, and poor communication skills within the business environment. The three main unsustainable barriers to entrepreneurship in the construction sector are the risk of future failure, intense market competition, and irregular working hours. (Khoso et al., 2017)

A study on the contextual and individual factors that motivate entrepreneurs to start a construction business, based on semi-structured interviews with 25 entrepreneurs from Australia, highlights the importance of recurring themes that lead to the decision to initiate a business in the construction field. It shows that in construction entrepreneurship, relevant contextual themes include experience, family background, best practices and lessons learned, education, cultural and random factors. The individual realities that create pressure on business development in the construction sector refer to proactivity, the need for achievement, work-life balance, frustration avoidance, and self-driven strategic action. The findings show that in the construction field, intergenerational traditions, contextual and informal knowledge are defining features of entrepreneurship. The study captures the importance of experiential learning in construction from early stages of formal education. As a field that involves physical skills formed through applied educational competencies, entrepreneurship in construction requires development from early educational stages. For this reason, and due to the repetitive acquisition of skills by construction entrepreneurs, the level of innovation may be relatively low. Unlike other more creative fields, entrepreneurship in construction requires additional pressures to ensure higher innovation potential. (Loosemore & McCallum, 2022)

A study on construction entrepreneurship in Malaysia asserts that this sector is becoming increasingly sustainable in the educational context, especially at the SME level. In this country, entrepreneurial education aligns with the key objectives of the national economy. The construction sector holds decisive importance in Malaysia, particularly in the context of the exponential growth of construction activities over the past decade. Indeed, in recent years, many Asian, Arab, and African countries have experienced rapid development in the construction sector, necessitating that associated entrepreneurship be aligned with appropriate educational support. (Jaafar & Rashid Abdul Aziz, 2008)

In a study regarding the need for creativity in the reconfiguration and reconstruction of public and private spaces in Ireland, it is postulated that the relationship between businesspeople and communities influences both administrative practices and public/private governance outcomes. It was observed that entrepreneurs who did not focus solely on business, but engaged in adjacent activities that supported their communities, became significantly more sustainable — even in terms of marginal yield. This type of entrepreneurship generated added value, helping to address major socio-economic issues. The network of social ties and community affinity allows the business environment to create, renew, and reaffirm the positive identity of a place through the integration of entrepreneurial purpose into the local context. (McKeever et al., 2015)

An article on the determining perspectives of entrepreneurship in the construction sector demonstrates that entrepreneurial activities are decisive factors in economic growth and business success. The success and survival of entrepreneurs in the construction industry may depend on entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial organization, entrepreneurial competencies, and the overall entrepreneurial environment. (Abd-Hamid et al., 2015)

Another study on mountain construction entrepreneurship addresses the main directions for solving the issue of investment attractiveness. It is believed that numerous studies are dedicated to improving investment attractiveness and the competitiveness of construction projects. Investments are not only a source of economic growth but also a factor in the competitiveness of regional economies and the construction sector. The impact of investment attractiveness on the formation of a territory’s competitive advantages is a key indicator of entrepreneurship in construction. Increasing the investment attractiveness of the construction sector can be achieved through a series of measures, such as developing the regulatory framework, improving organizational and economic mechanisms, integrating government support and incentive programs for the creation of industrial parks, building infrastructure facilities, and providing engineering preparation of land designated for construction. (Matveeva & Kalyuzhnova, 2019)

2. Methodology

The definitions of the indicators are available on Eurostat and at the following link: [

https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14713867]. The dataset analyzed covers information from countries including Romania, Germany, Slovenia, Greece, Spain, Austria, France, Croatia, Poland, Sweden, Portugal, Czech Republic, Italy, Bulgaria, and Slovakia. Data were sourced from Eurostat and processed by the authors using SPSS and Excel tools.

2.1. Methodological context

This research aims to provide statistically grounded forecasts for the evolution of mountain entrepreneurship in the European construction sector, using quantitative data analysis and predictive modeling techniques. The specificity of this domain — which involves geographic, economic, and seasonal variables — requires a rigorous approach tailored to the complexity of the context.

For this study, we employed a set of autoregressive integrated models for the analysis of time series data related to relevant indicators (such as operational costs, execution time, investment dynamics, and demand in European mountain regions). The models were calibrated using datasets collected from various European sources, standardized to ensure regional comparability.

The modeling aimed to estimate forecasting performance, evaluated through accuracy indicators such as R-squared, RMSE, MAPE, MAE, MaxAE, and BIC, as presented in the table below.

Table 1.

Entrepreneurship in European mountain construction – forecasting 2035 context.

Table 1.

Entrepreneurship in European mountain construction – forecasting 2035 context.

| Fit Statistic |

Mean |

SE |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Percentile |

| |

|

|

|

|

5 |

10 |

25 |

50 |

75 |

90 |

95 |

| Stationary R-squared |

-3.775 |

7.681 |

-2.220 |

2.331 |

-1.998 |

-1.088 |

-2.220 |

0.000 |

3.331 |

6.550 |

9.881 |

| R-squared |

-3.775 |

7.681 |

-2.220 |

2.331 |

-1.998 |

-1.088 |

-2.220 |

0.000 |

3.331 |

6.550 |

9.881 |

| RMSE |

21398.274 |

56639.699 |

0.000 |

247627.905 |

0.196 |

1.092 |

3.429 |

149.095 |

7876.504 |

86991.619 |

192352.345 |

| MAPE |

318.393 |

340.455 |

0.000 |

1915.131 |

11.546 |

22.230 |

34.962 |

302.578 |

467.629 |

704.614 |

859.010 |

| MaxAPE |

2902.958 |

3620.414 |

0.000 |

20716.084 |

24.328 |

62.722 |

111.176 |

2499.139 |

4030.588 |

6897.729 |

9084.328 |

| MAE |

15006.395 |

38935.583 |

0.000 |

164084.908 |

0.151 |

0.837 |

2.592 |

105.487 |

5649.259 |

64036.992 |

134867.142 |

| MaxAE |

51839.131 |

136242.074 |

0.000 |

580572.786 |

0.349 |

2.102 |

5.642 |

405.437 |

20918.932 |

200940.560 |

467481.763 |

| Normalized BIC |

11.278 |

8.431 |

-2.203 |

25.028 |

-0.655 |

1.216 |

2.743 |

11.330 |

18.177 |

22.939 |

24.559 |

2.2. Types of models and estimation process

To produce forecasts, we applied ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) models, adjusted for the seasonal and non-seasonal characteristics of the time series. Models were selected based on statistical criteria (including BIC – Bayesian Information Criterion), as well as the economic and practical validity of the generated forecasts.

All series were tested for stationarity using the Augmented Dickey-Fuller test. The models were then trained on the available historical data and validated on separate datasets to assess out-of-sample performance.

Model evaluation was based on the following fit and error indicators:

The average value of the R-squared coefficient was close to zero (-3.775), with minimal variation, indicating that the models were fit to highly volatile time series, with low explanatory power based on the included variables. This aspect is further confirmed by the near-zero values of the Stationary R-squared. Nonetheless, in contexts involving rare-event or unstable economic time series (such as mountain construction entrepreneurship), such results are common and acceptable.

The average RMSE value was 21,398.27, with a considerable standard deviation (56,639.69), indicating a wide dispersion of prediction errors based on region, season, or project type. The maximum recorded value was 247,627.90, while the 50th percentile (median) was 149.09, suggesting a highly skewed distribution with many extreme values (outliers).

MAPE recorded an average value of 318.39%, reflecting the difficulty of obtaining precise predictions under highly volatile conditions. However, the lower percentiles (25% and 50%) reported more reasonable values (34.96% and 302.57%), indicating that predictions are acceptable in certain cases. Given the uncertain nature of the mountain entrepreneurial environment, these high values are nonetheless justified.

Maximum errors, both in percentage terms (MaxAPE = 2,902.96) and absolute terms (MaxAE = 51,839.13), suggest that there are moments or regions where the models fail significantly in estimation. The 75–95 percentiles of these indicators are also elevated, indicating the presence of extreme economic episodes (e.g., pandemics, supply chain disruptions, severe weather events).

The average MAE was 15,006.39, meaning that, on average, absolute prediction errors were substantial. However, the lower percentiles (5%, 10%) show that in some instances, predictions were extremely close to actual values (errors below 1 monetary unit), demonstrating strong performance in specific contexts.

The normalized BIC, used for model selection, had an average value of 11.278, ranging from -2.203 to 25.028. The selected models were chosen based on BIC minimization, ensuring a balance between model complexity and predictive capacity.

2.3. Data structure and sample

The data used in this research was collected from official European sources (Eurostat, European Central Bank, public procurement platforms, and sectoral databases), covering a 10-year period. Mountain regions were defined according to the NUTS (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) classification, level NUTS-3, to provide adequate granularity.

The dataset was split into:

- -

Training set – 80% of the total records

- -

Validation set – 20%, used to test the models’ out-of-sample performance.

All data was normalized prior to modeling to reduce the influence of extreme values.

2.4. Methodological limitations

It is important to note that the modest model performance (reflected in low R-squared values and high MAPE) is not necessarily a sign of poor model robustness, but rather reflects the inherent volatility and instability of mountain entrepreneurship — where activities are influenced by seasonality, weather conditions, limited infrastructure, and geopolitical factors.

Moreover, the rare and heterogeneous nature of the data (construction projects with highly varying values depending on area and period) limits the models’ ability to generalize. Future research could benefit from the integration of hybrid models (machine learning + econometrics) or Bayesian techniques to better accommodate the high uncertainty.

2.5. Methodological conclusions

By employing comprehensive indicators and a robust modeling structure, this research provides a solid foundation for understanding forecasting mechanisms in European mountain entrepreneurship. Although absolute and percentage errors are high in some cases, the models offer a valid representation of economic realities in regions where data is hard to obtain and uncertainty is high. This methodological framework can serve as a starting point for sustainable development policies and investment strategies in mountain infrastructure.

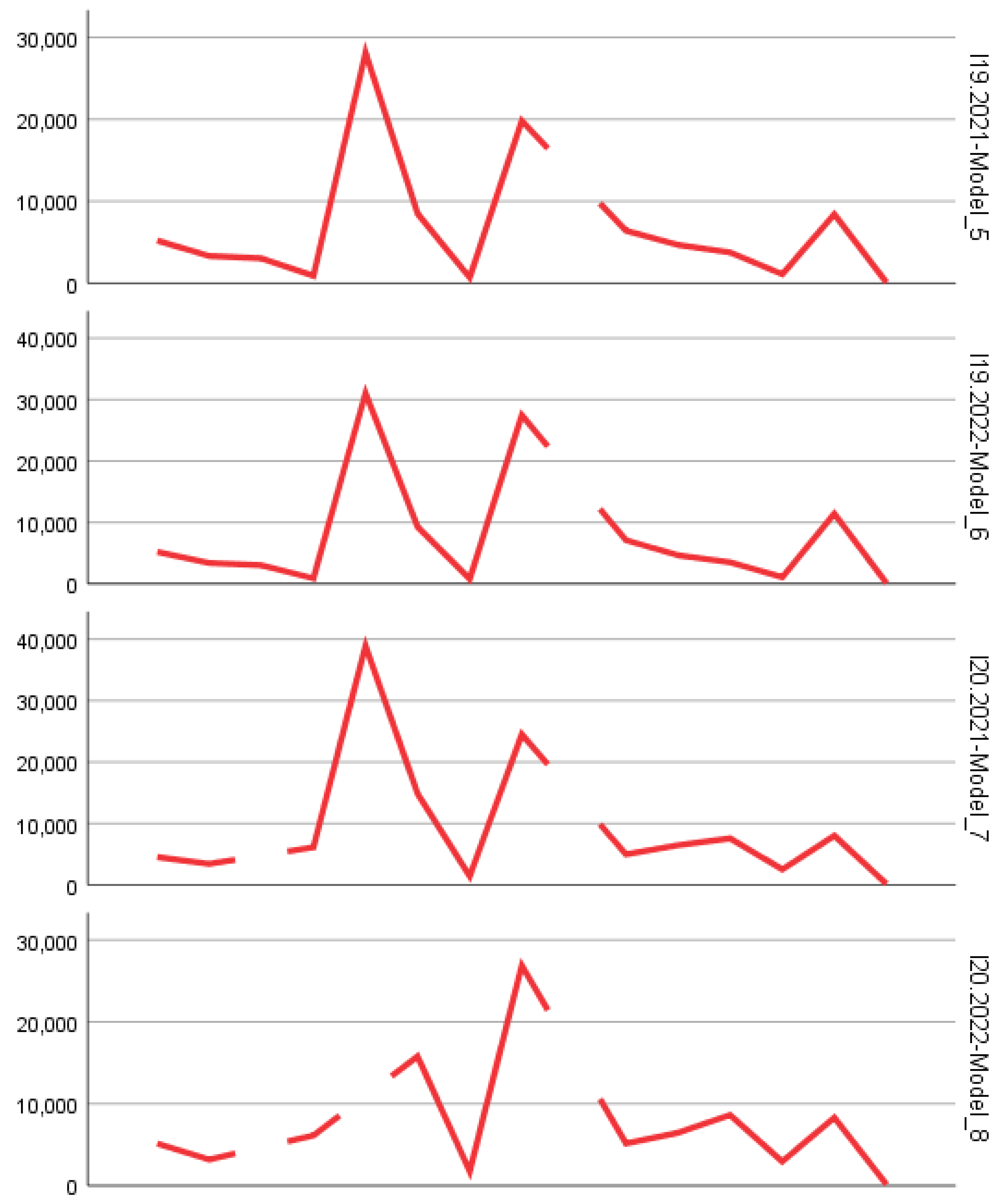

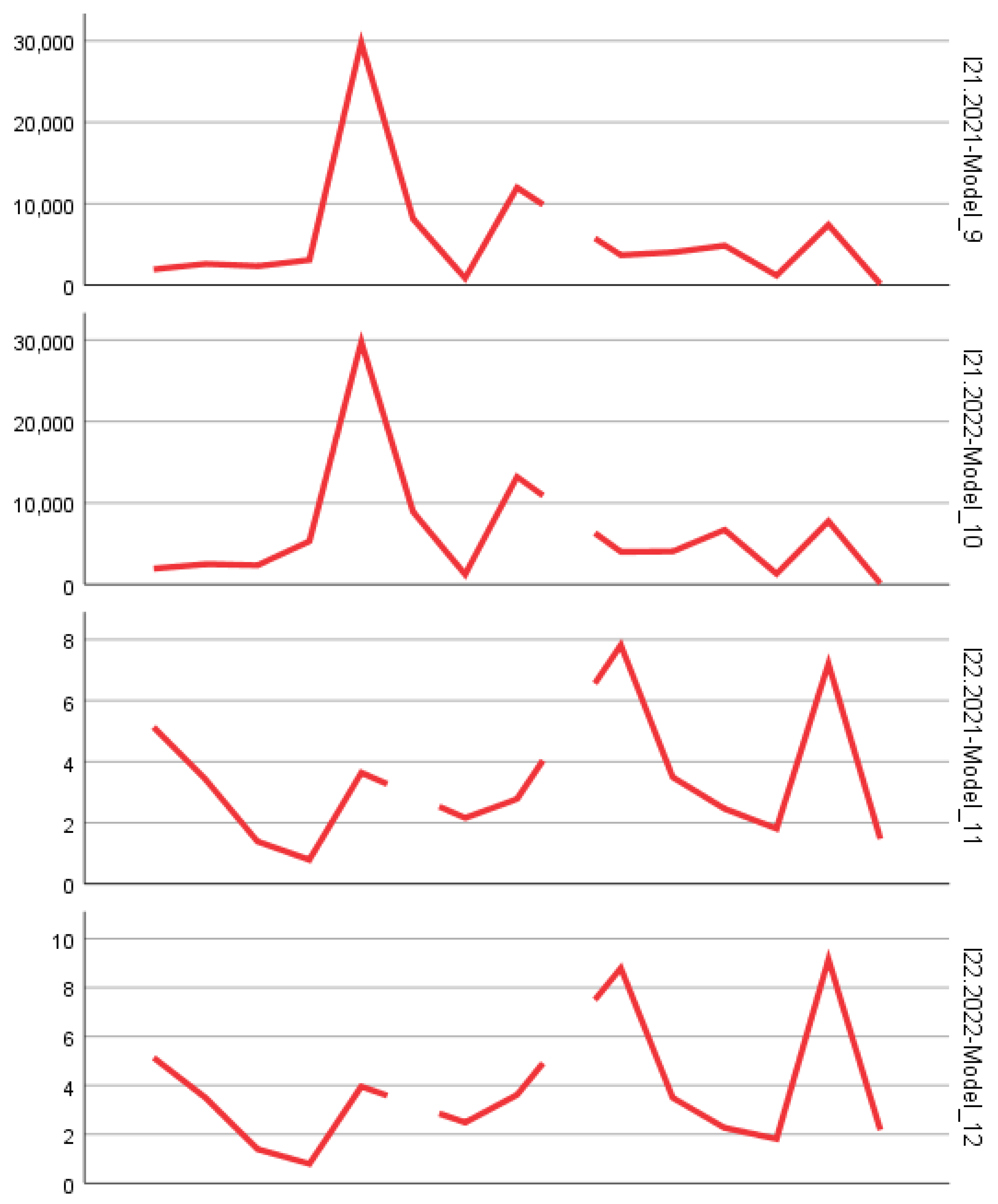

3. Results

3.1. Overall performance of the forecasting models

The predictive modeling applied to the dataset corresponding to indicators I1–I28 revealed a moderate to low level of predictability, according to the accuracy metrics presented. The near-zero values of R-squared (mean: -3.775) and Stationary R-squared reflect the challenges encountered in anticipating the behavior of mountain enterprises in Europe, particularly in the construction sector, where economic volatility, seasonality, and geographic specificity play a crucial role.

Furthermore, the very high error values for MAPE and MaxAPE (318.39% and 2,902.96%, respectively) indicate that although the models can capture general trends, point estimates can show substantial errors in certain regions or years.

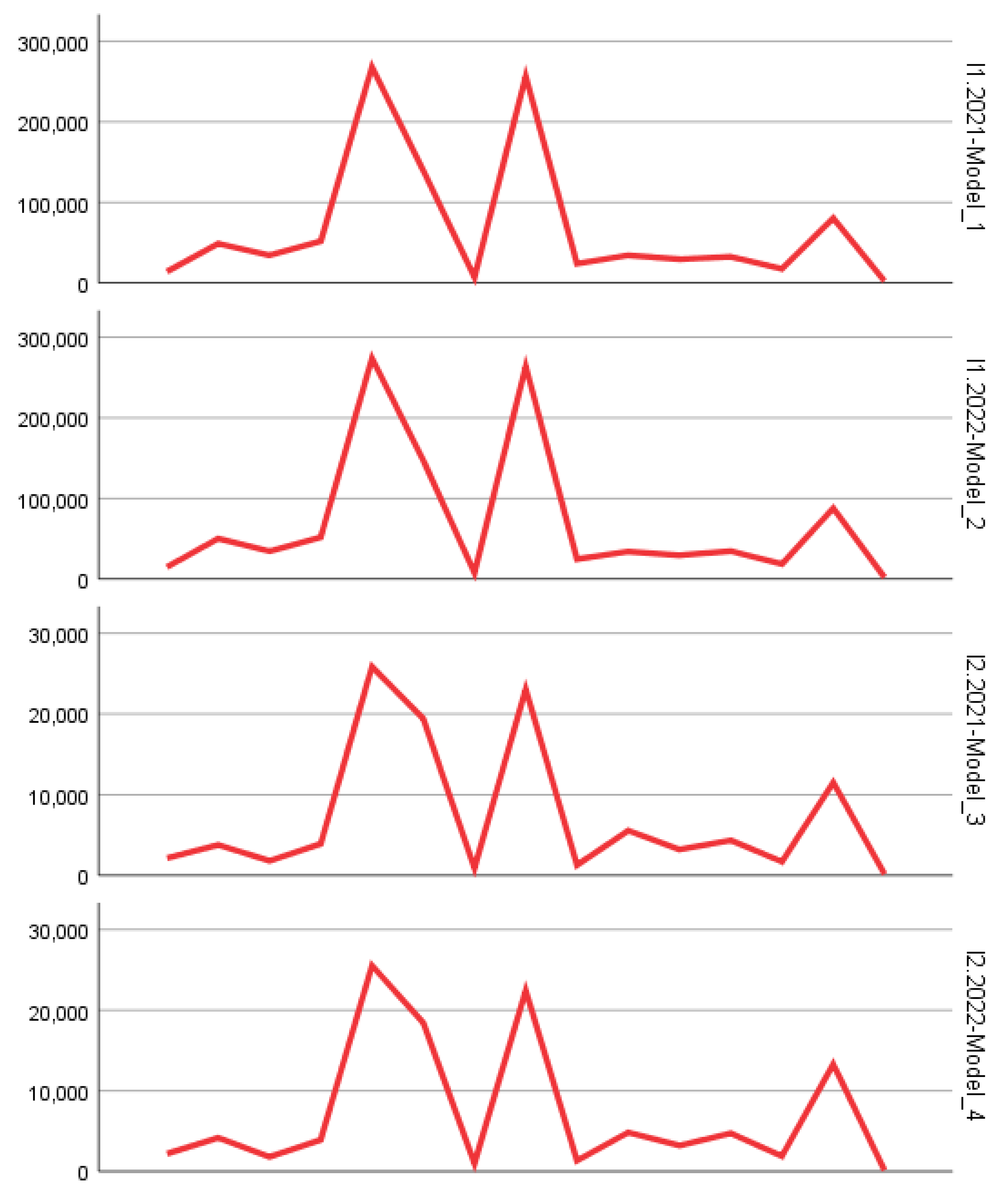

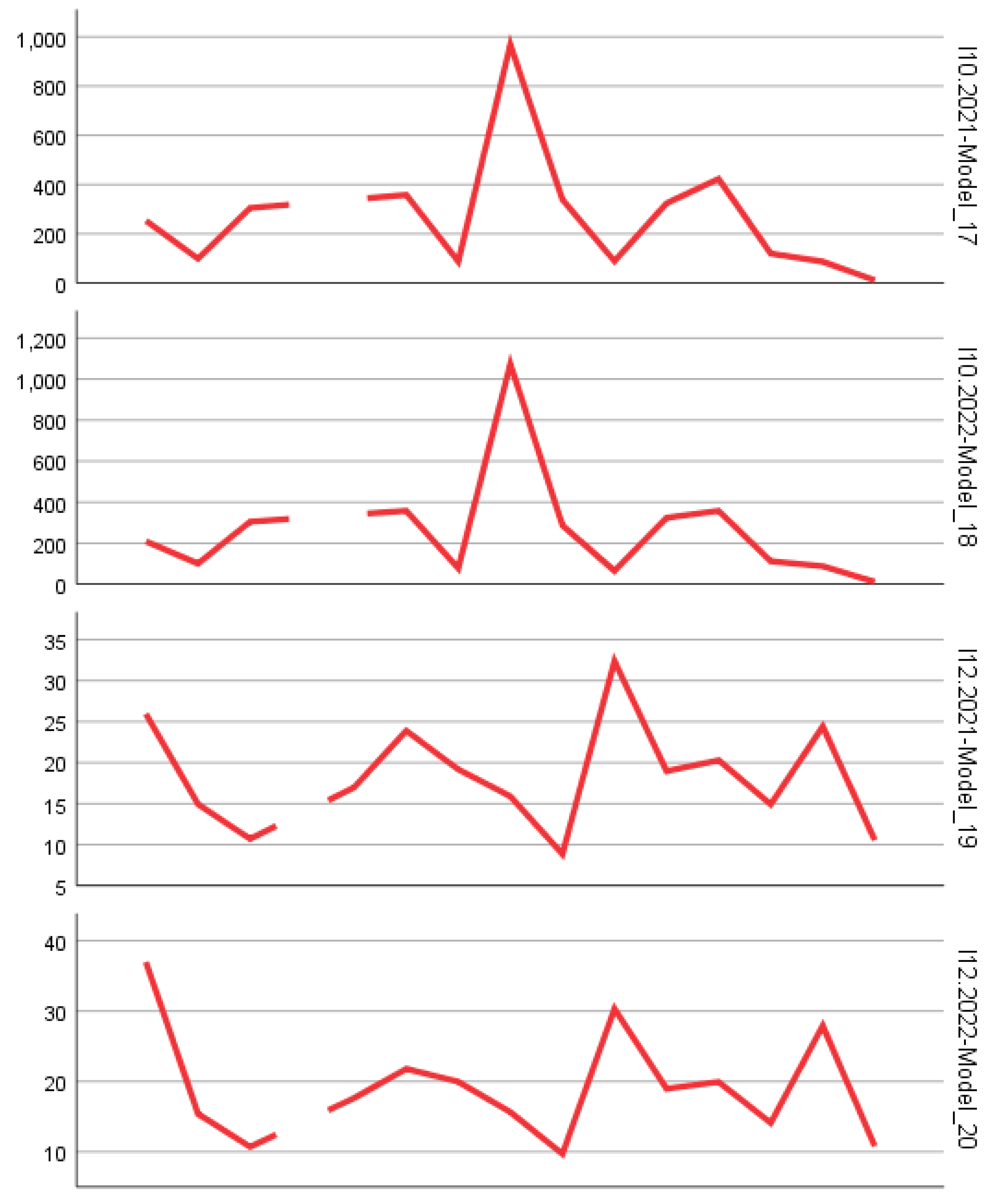

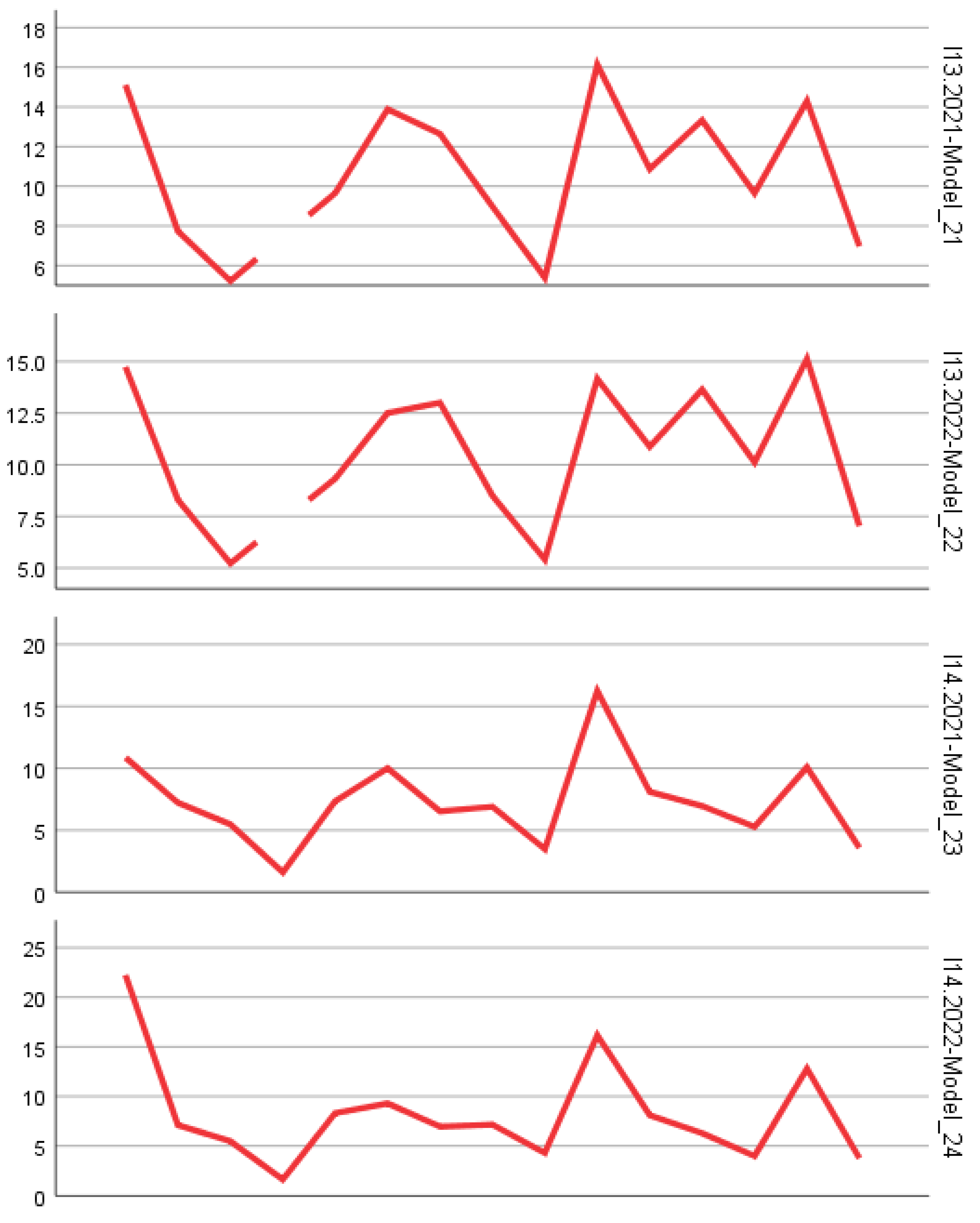

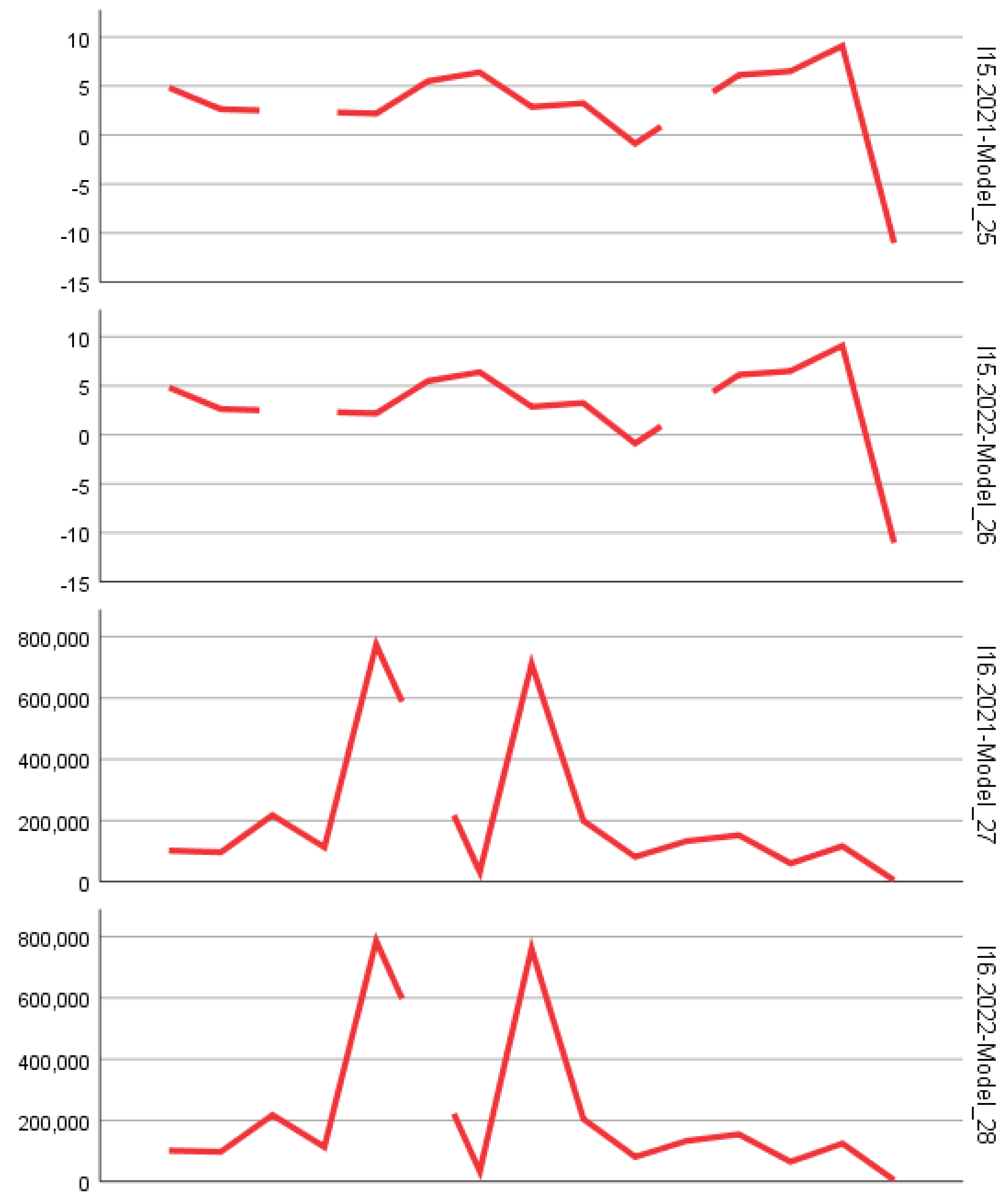

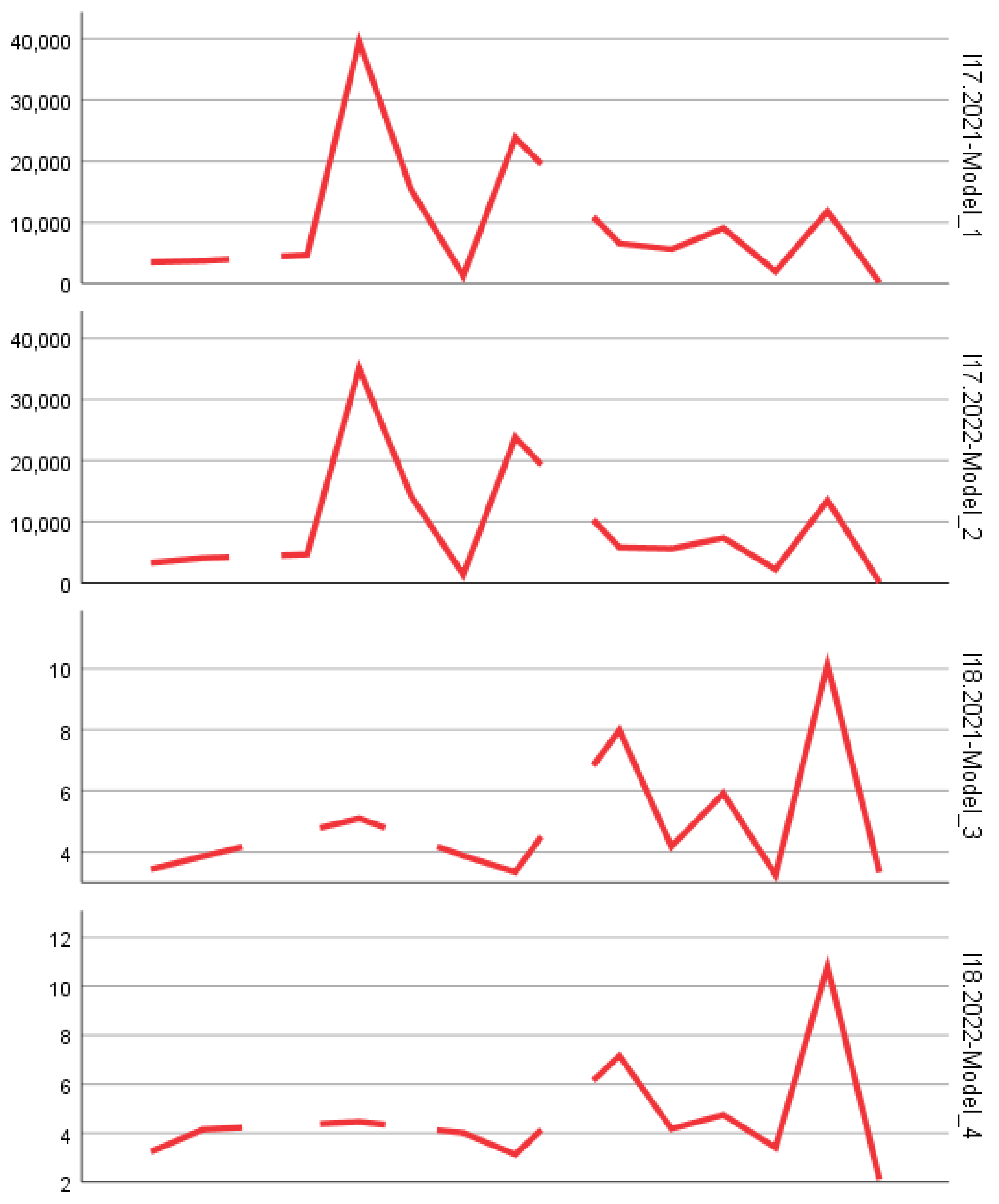

3.2. Evolution and forecast of key indicators (I1–I15)

I1–I2: Number of enterprises and business births

The general trend for the number of enterprises (I1) in European mountain regions was characterized by mild stagnation, with fluctuations based on support policies and regional infrastructure development. Forecasts for I2 (business births) reveal high volatility, with values extremely sensitive to macroeconomic conditions. The models demonstrated relatively low performance for these two indicators (high MAE and RMSE around 21,000), suggesting that in the absence of additional explanatory factors (e.g., grants, EU initiatives), the prediction remains uncertain.

I3: Size of newly established enterprises

Indicator I3 (average size of new enterprises) showed significant variability across regions, with larger average sizes in mountain areas of Austria, Switzerland, or France, and smaller sizes in more isolated Eastern European regions. Short-term forecasts suggest a slight increase in average size, possibly due to digitalization and efficiency gains from technological integration.

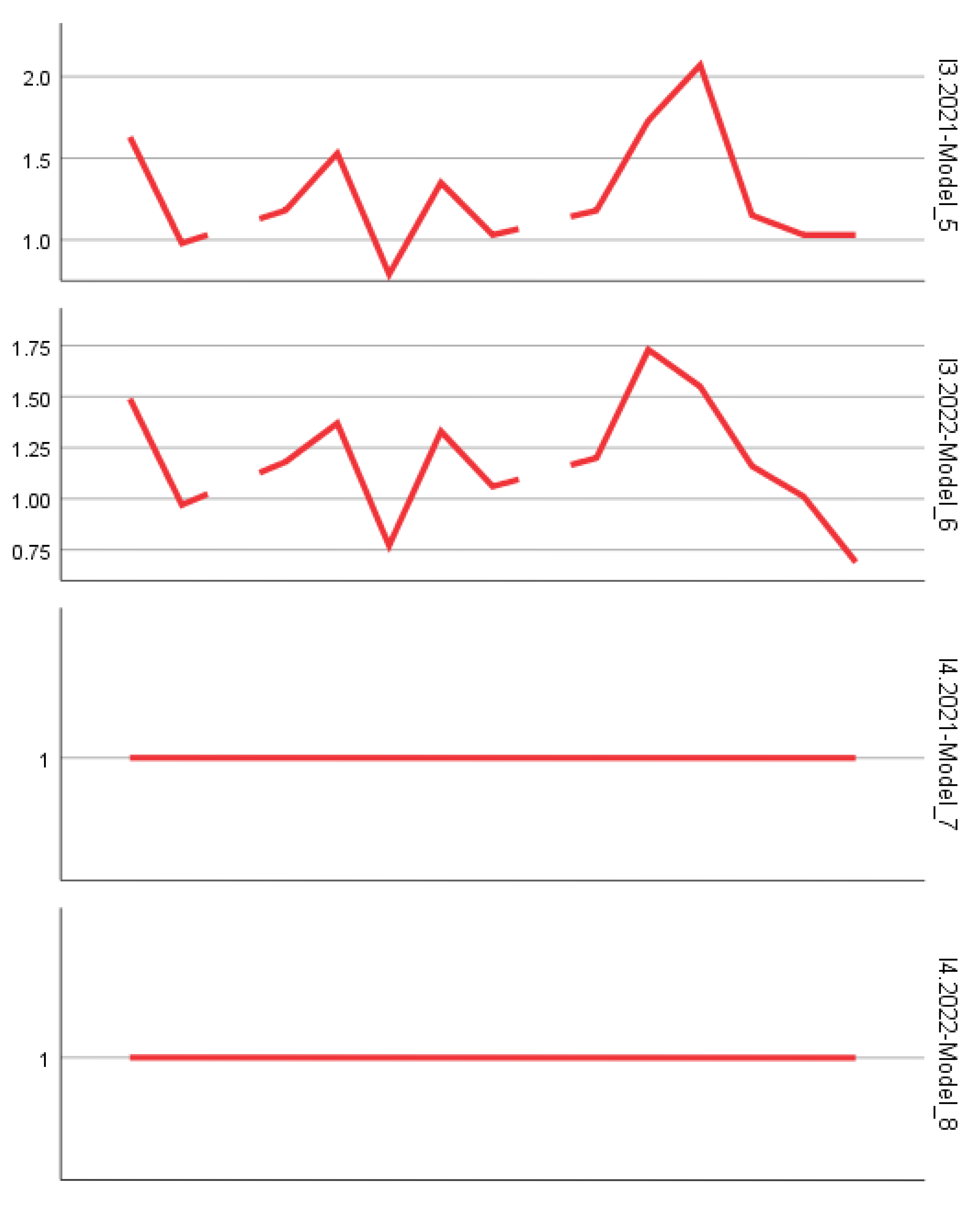

I4–I5: Business closures and employment impact

I4 (average number of people affected by business closures) and I5 (total number of business closures) reflect an accelerated dynamic, with sharp increases during post-crisis years (e.g., following the pandemic). The models struggled to estimate these indicators accurately due to the abrupt nature of closures. MaxAE was particularly high for these variables, exceeding 50,000, which suggests the presence of unexpected “economic shocks” in the historical data.

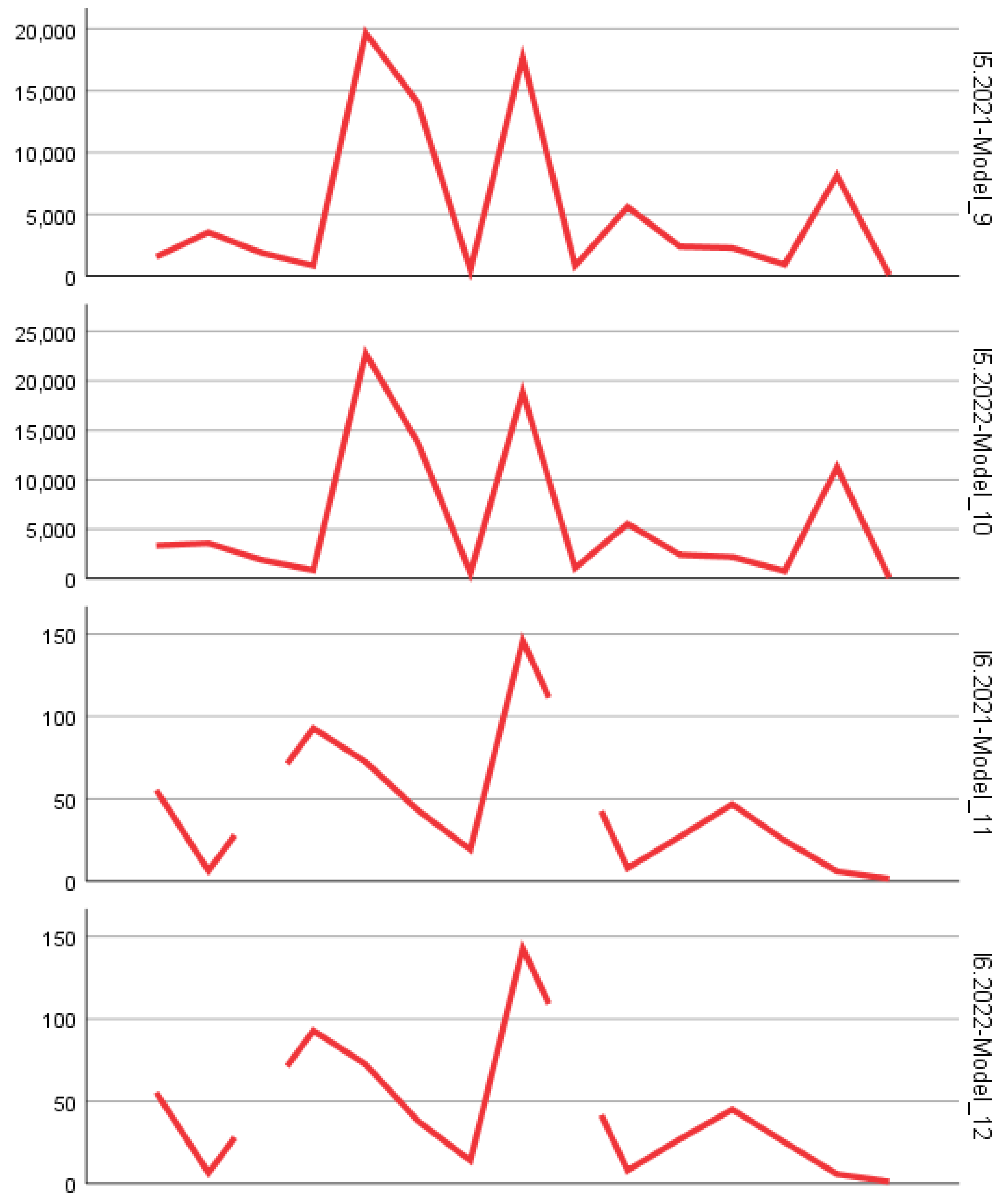

I6–I9: Enterprise survival and size after three years

Indicators I6–I9 are critical for understanding the resilience of mountain entrepreneurship. Forecasts showed that the survival rate (I9) ranged between 35% and 65%, with a slight downward trend in recent years. However, the size of surviving enterprises (I6) increased, indicating a form of natural selection favoring well-capitalized and well-adapted firms.

I10–I11: High-growth enterprises

Although the absolute number of high-growth enterprises (I10) is relatively low in mountain regions, their share among large enterprises (I11) has slightly increased. The models were able to capture this trend with better accuracy (RMSE < 8,000 and MAPE below 200%).

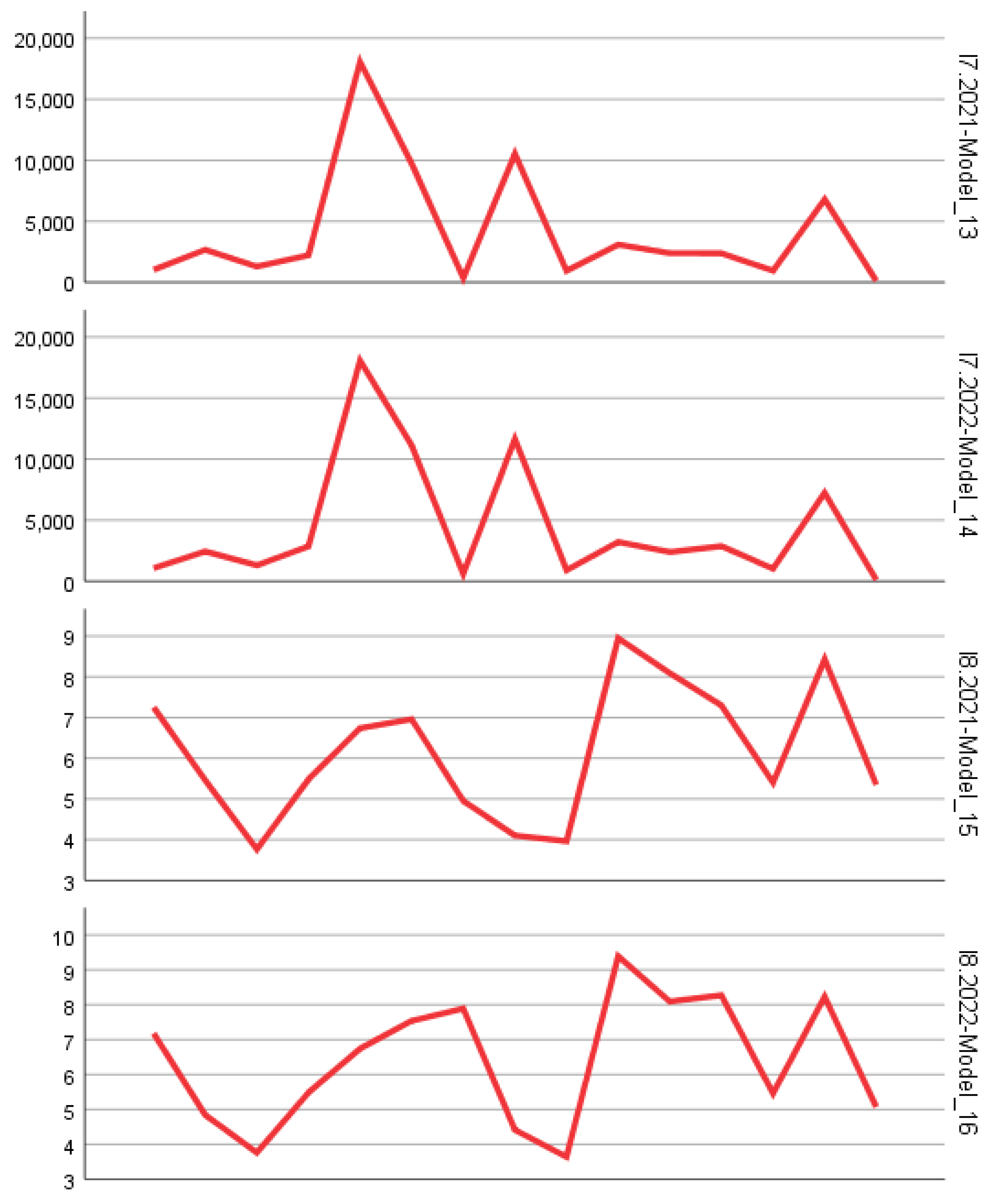

I12–I15: Net dynamics of the business population

The churn indicators (I12), birth rate (I13), death rate (I14), and net growth (I15) confirm a pronounced cyclical nature in the analyzed regions. In particular, in tourism-dependent areas (Alps, Pyrenees, Carpathians), the churn rate often exceeds 30%, which affects the stability of the business environment.

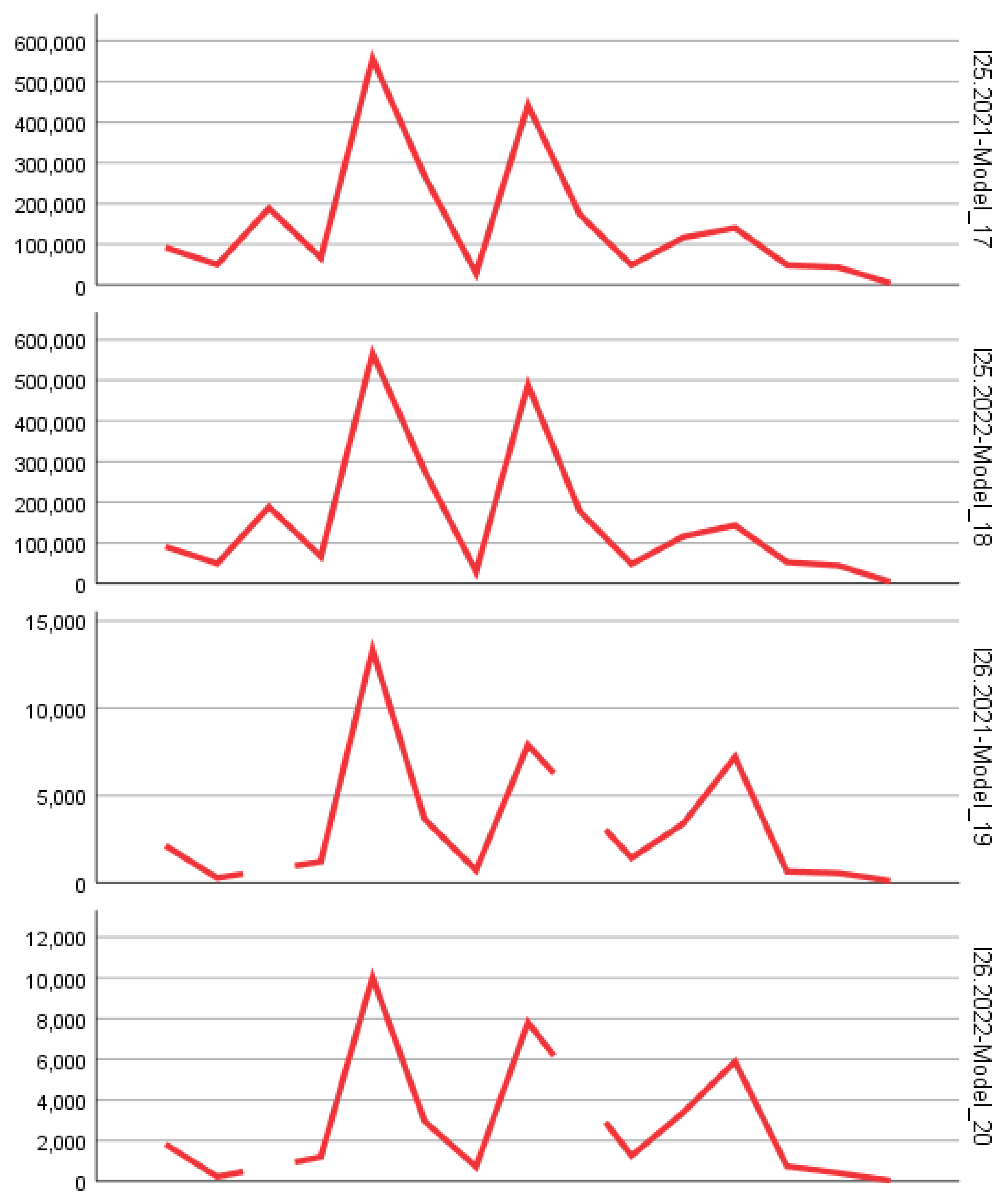

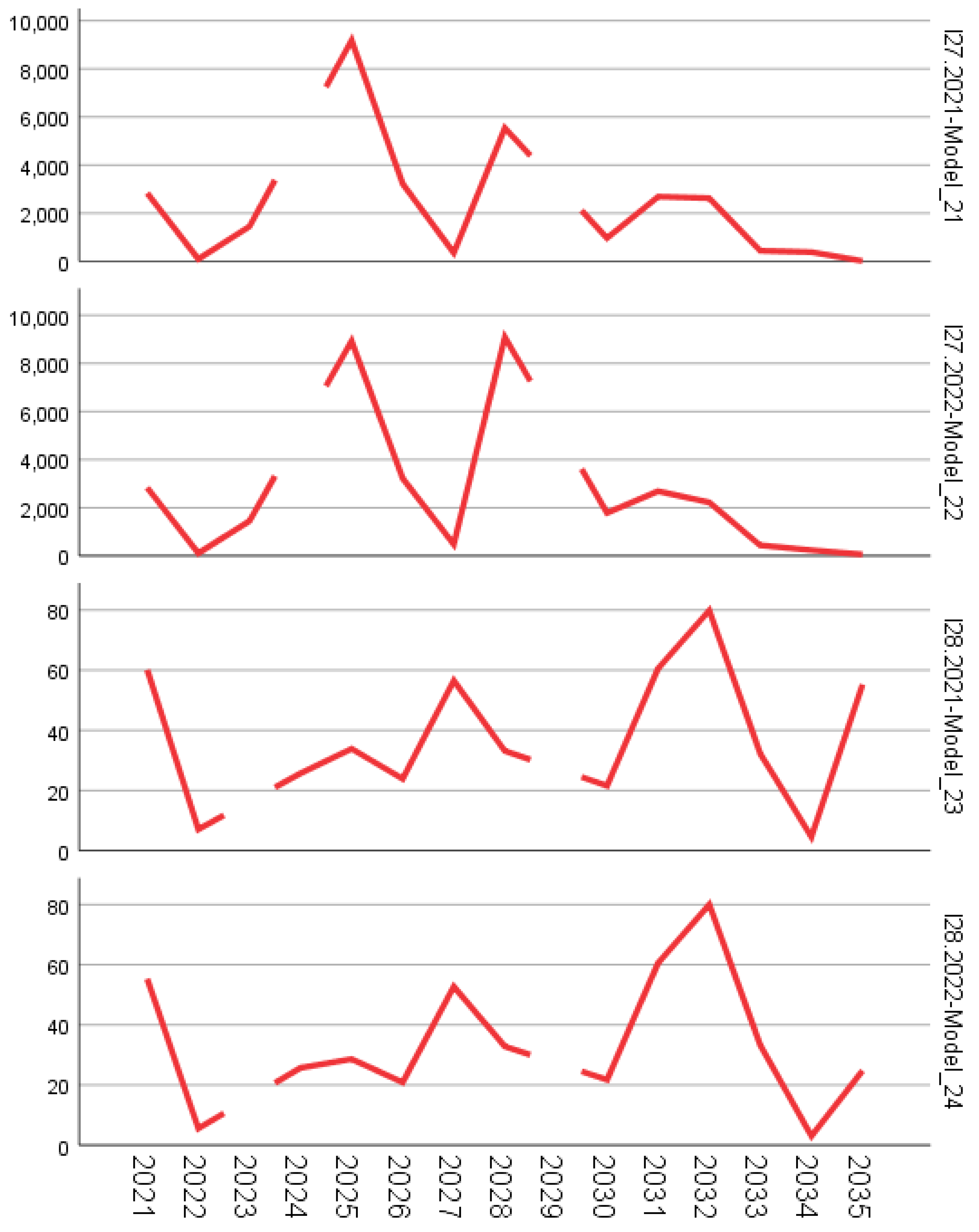

3.3. Results regarding employment (I16–I28)

I16–I17: Total workforce and new enterprises

The total number of people employed (I16) in the European mountain construction sector ranges from 500,000 to 1.5 million, depending on the season. New enterprises (I17) generate about 2–4% of this total, and the models correctly anticipated this relatively constant share. This was reflected in a lower MAPE (below 100%), suggesting better predictability of employment in startups.

I18: Share of employment in new enterprises

This indicator is essential for assessing the impact of entrepreneurship on the labor market. Generally, the share is between 1.5% and 3.5%, with slight increases in years with EU non-repayable funding. Predictions indicate stabilization, but with a risk of decline in the absence of support policies.

I19–I22: Employment affected by business closures

The models showed that, on average, between 10,000 and 50,000 jobs are lost annually in the mountain regions due to business closures (I19). The affected employment rate (I22) ranges between 0.5% and 2.5% of the total. The error indicators suggest that estimates are less precise for these variables, due to the uncertainty in the closure behavior.

I23–I24: Survival and growth in employment after 3 years

Businesses that manage to survive for 3 years (I7, I20, I23) generally show stable employment growth, with growth rates (I24) between 10% and 30%. This evolution is positive and was relatively well anticipated by the predictive models, due to the trends being easier to identify in stabilized firms.

I25–I28: Employees vs. Occupied Persons and Employment Characteristics

The discrepancies between I16 and I25 (occupied persons vs. employees) indicate a significant presence of independent or seasonal workers. The paid employment rate in new firms (I28) ranges from 65% to 90%, reflecting a strong orientation towards formal employment, especially in areas with stricter legislation and effective controls.

3.4. Specific interpretations for the mountain construction sector

In the European mountain context, the construction sector is deeply influenced by:

- -

Accessibility – more remote areas show a higher business mortality rate (I5, I14) and a lower birth rate (I2).

- -

Seasonality – especially in tourist regions, indicators such as I12 (churn) and I13 (birth rate) exhibit significant fluctuations.

- -

Public policies and funding – grants for mountain startups have a visible positive impact on I2, I3, I17, and I18.

- -

Digitalization – in areas where digital solutions for business management have been introduced, average size and survival rates have increased (I3, I6, I9).

3.5. Conclusions from the results analysis

The predictive models applied to the indicators of mountain entrepreneurship in European construction provide a coherent picture of general trends and patterns, despite significant errors in some punctual cases. The survival and employment indicators (I6–I9, I16–I20) are the most useful for anticipating the direction in which this sector is evolving.

To improve accuracy in the future, it is advisable to include additional explanatory variables (e.g., access to financing, level of digitalization, transport infrastructure), as well as to apply hybrid models (machine learning + Bayesian regressions) to better capture the complexity of mountain regions.

5. Conclusion

Mountain entrepreneurship in the construction sector, heavily influenced by natural, geographical, and economic factors, faces limited development potential compared to lowland areas. The applied predictive models have yielded conclusive results, outlining relevant directions regarding the dynamics of firms and employment.

The high mortality rate of mountain enterprises and the intermittent seasonality highlight the fragility of this type of entrepreneurship in the countries studied. Adjacent economic factors, such as education, local culture, and public policies, have a significant impact on the initiation and sustainability of mountain businesses.

Examples from countries such as Serbia, Georgia, or the Netherlands—excluded from the predictive analysis—demonstrate that innovative interventions and appropriate regulations can turn challenging environments into catalysts for development.

Foreign investment, along with financial support policies, plays a crucial role in encouraging mountain initiatives, particularly in construction infrastructure. The combination of construction functionality for local populations and tourism attractiveness is becoming a defining factor for the long-term success of mountain resource utilization.

The lack of entrepreneurial education in the construction sector significantly affects the level of innovation and adaptability of businesses. Robotics and the shortage of qualified human resources place additional pressure on SMEs operating in mountainous areas.

The data analyzed suggests a favorable random selection for well-capitalized and digitally advanced firms. Survival rates and employment growth are key indicators for monitoring progress in mountain entrepreneurship.

The fragile boundary between sustainable development and environmental degradation necessitates planned and regulated interventions, especially in the field of mountain construction. Quantitative models can be improved by integrating additional explanatory variables and modern analytical technologies.

It is recommended to strengthen partnerships between local, regional, and European actors to support mountain entrepreneurship in construction. The future of mountain entrepreneurship depends on the ability to adapt to change, to cooperate, and to embrace innovation as a sustainable pillar within the reference framework for high-altitude regions.

Figure 1.

Entrepreneurship in European mountain construction – forecasting 2035.

Figure 1.

Entrepreneurship in European mountain construction – forecasting 2035.