Submitted:

18 May 2025

Posted:

20 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10)

Nitrogen Dioxide (NO₂)

Ozone (O₃)

Sulfur Dioxide (SO₂) and Carbon Monoxide (CO)

Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs)

| Smog Component | Concentration | Cardiovascular Health Effects | References |

| Ozone (Ground-Level) | Acidic smog: 0.8–1.0 ppmPhotochemical smog: 0.4–0.8 ppm | Ozone promotes systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, arrhythmia and elevate the risk of myocardial infarction | [58–62] |

| Particulate Matter (PM2.5) | In Asian cities: ~10 µg/m³* (varies widely; reported ranges from 4.9 to 32.8ppm in some measurements, though most health studies use µg/m³) | PM2.5 is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, associated with heart attacks, stroke, and arrhythmias due to deep lung penetration and systemic inflammation | [63–68] |

| Nitrogen Dioxide (NO₂) | Approx. 75 to 175 ppb | Nitrogen dioxide causes vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, increased blood pressure and elevated risk of heart disease | [69–72] |

| Sulphur Dioxide (SO₂) | Approx. 0.75 ppm | Sulphur dioxide causes vasoconstriction and promotes inflammation. It can exacerbate pre-existing cardiovascular conditions and increase the risk of heart failure | [73] |

| Peroxyacetyl Nitrate (PAN) | Approx. 37 ppb | PAN contributes to overall smog toxicity, which may indirectly stress the cardiovascular system via respiratory pathways | [74,75] |

| Benzopyrene | 3.64–61.6 ng/m³ | Benzopyrene acts as a potent oxidant inducing systemic inflammation and it may accelerate atherosclerosis, indirectly affecting cardiovascular health | [76] |

| Phthalate Esters | 10–100 ng/m³ | Phthalate Esters influence cardiovascular risk indirectly through metabolic alterations and hormonal imbalances | [77] |

Smog and Cardiovascular Disease in Punjab, Pakistan: A Case Example

Discussion

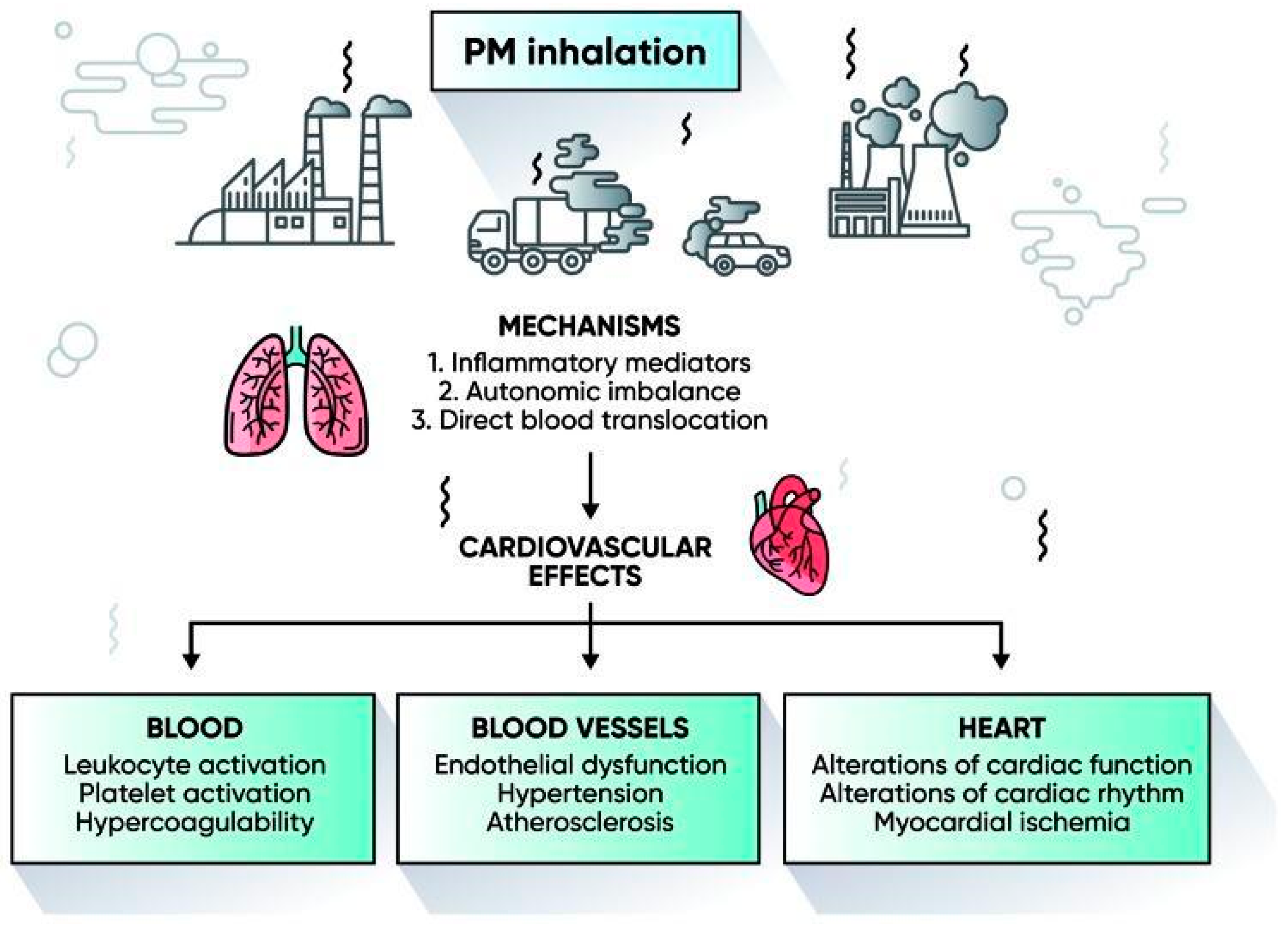

Mechanisms of Impact

Disparities in Exposure and Vulnerability

Punjab, Pakistan – A Regional Case Example

Comparison with International Findings

Gaps in Literature and Research Limitations

Conclusion

| Pollutant | Source | Cardiovascular Effects |

| PM2.5 | Combustion, vehicles, biomass | Stroke, IHD, systemic inflammation |

| PM10 | Dust, construction, traffic | Atherosclerosis, heart failure |

| Nitrogen Dioxide (NO₂) | Traffic, power plants | Autonomic dysfunction, vascular damage |

| Ozone (O₃) | Photochemical reactions | Arrhythmias, oxidative stress |

| Carbon Monoxide (CO) | Incomplete combustion | Reduced oxygen delivery, ischemia |

| Sulphur Dioxide (SO₂) | Fossil fuel burning | Vasoconstriction, increased CVD admissions |

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | Biomass, traffic | Atherosclerosis, inflammation |

| Carbon Black | Diesel exhaust | Endothelial dysfunction |

| Location | Study Type | Key Finding |

| USA | Review | PM2.5 strongly linked to myocardial infarction |

| Italy | Time-series | PM10 exposure increased daily CVD hospital visits |

| Global | Meta-analysis | Smog exposure increases stroke risk |

| China | Cohort | Long-term NO₂ exposure increases CVD mortality |

| Lahore, Pakistan | Observational | Increased cardiac admissions during smog season |

| Global | Global burden study | LMICs bear 90% of CVD deaths linked to air pollution |

List of Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Form |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| CVD | Cardiovascular Disease |

| IHD | Ischemic Heart Disease |

| PM | Particulate Matter |

| PM₂.₅ | Particulate Matter ≤ 2.5 micrometers in diameter |

| PM₁₀ | Particulate Matter ≤ 10 micrometers in diameter |

| NO₂ | Nitrogen Dioxide |

| SO₂ | Sulphur Dioxide |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide |

| PAHs | Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons |

| O₃ | Ozone |

References

- Anderson, J.O., Thundiyil, J.G. and Stolbach, A., 2012. Clearing the air: a review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human health. Journal of Medical Toxicology, 8(2), pp.166–175. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourdrel, T., Bind, M.A., Béjot, Y., Morel, O. and Argacha, J.F., 2017. Cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases, 110(11), pp.634–642.

- Brook, R.D., Rajagopalan, S., Pope III, C.A., Brook, J.R., Bhatnagar, A., Diez-Roux, A.V., Holguin, F., Hong, Y., Luepker, R.V., Mittleman, M.A. and Peters, A., 2010. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: An update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 121(21), pp.2331–2378.

- Cesaroni, G., Badaloni, C., Gariazzo, C., Stafoggia, M., Sozzi, R., Davoli, M. and Forastiere, F., 2014. Long-term exposure to urban air pollution and mortality in a cohort of more than a million adults in Rome. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121(3), pp.324–331. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H., Burnett, R.T., Kwong, J.C., Villeneuve, P.J., Goldberg, M.S., Brook, R.D., van Donkelaar, A., Jerrett, M., Martin, R.V., Brook, J.R. and Kopp, A., 2013. Risk of incident diabetes in relation to long-term exposure to fine particulate matter in Ontario, Canada. Environmental Health Perspectives, 121(7), pp.804–810. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.J., Brauer, M., Burnett, R., Anderson, H.R., Frostad, J., Estep, K., Balakrishnan, K., Brunekreef, B., Dandona, L., Dandona, R. and Feigin, V., 2017. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. The Lancet, 389(10082), pp.1907–1918. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency), 2020. Integrated Science Assessment for Particulate Matter. EPA/600/R-19/188.

- Feng, S., Gao, D., Liao, F., Zhou, F. and Wang, X., 2016. The health effects of ambient PM2.5 and potential mechanisms. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 128, pp.67–74.

- Forouzanfar, M.H., Afshin, A., Alexander, L.T., Anderson, H.R., Bhutta, Z.A., Biryukov, S., Brauer, M., Burnett, R., Cercy, K. and Charlson, F.J., 2016. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks. The Lancet, 388(10053), pp.1659–1724. [CrossRef]

- GBD 2020 Risk Factors Collaborators, 2021. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet, 396(10258), pp.1223–1249.

- Gharibvand, L., Shavlik, D., Ghamsary, M., Beeson, W.L., Soret, S., Knutsen, R. and Knutsen, S.F., 2017. The association between ambient fine particulate air pollution and lung cancer incidence: Results from the AHSMOG-2 study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 125(3), p.378–384. [CrossRef]

- Hoek, G., Krishnan, R.M., Beelen, R., Peters, A., Ostro, B., Brunekreef, B. and Kaufman, J.D., 2013. Long-term air pollution exposure and cardio-respiratory mortality: a review. Environmental Health, 12(1), p.43. [CrossRef]

- Khan, S., Mahmood, A., Raza, A., Rehman, A. and Butt, Z.A., 2020. Acute health impacts of smog episodes on cardiovascular and respiratory admissions in Lahore, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 36(6), pp.1290–1295.

- Lelieveld, J., Klingmüller, K., Pozzer, A., Burnett, R.T., Haines, A. and Ramanathan, V., 2019. Effects of fossil fuel and total anthropogenic emission removal on public health and climate. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(15), pp.7192–7197. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C., Chen, R., Sera, F., Vicedo-Cabrera, A.M., Guo, Y., Tong, S., Coelho, M.S.Z.S., Saldiva, P.H.N., Lavigne, E., Matus, P. and Valdes Ortega, N., 2019. Ambient particulate air pollution and daily mortality in 652 cities. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(8), pp.705–715. [CrossRef]

- Mills, N.L., Donaldson, K., Hadoke, P.W., Boon, N.A., MacNee, W., Cassee, F.R., Sandström, T., Blomberg, A. and Newby, D.E., 2009. Adverse cardiovascular effects of air pollution. Nature Clinical Practice Cardiovascular Medicine, 6(1), pp.36–44.

- Münzel, T., Sørensen, M., Gori, T. and Schmidt, F.P., 2017. Effects of gaseous and solid constituents of air pollution on endothelial function. European Heart Journal, 38(20), pp.1590–1591.

- Nawaz, M., Ahmad, S., Saeed, M.A., Saleem, T. and Rana, I.A., 2021. Investigating the impact of smog on human health in Punjab: A spatio-temporal analysis. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 193(4), p.238.

- Pope III, C.A., Dockery, D.W., 2006. Health effects of fine particulate air pollution: lines that connect. Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 56(6), pp.709–742. [CrossRef]

- Pope III, C.A., Turner, M.C., Burnett, R.T., Jerrett, M., Gapstur, S.M., Diver, W.R. and Krewski, D., 2015. Relationships between fine particulate air pollution, cardiometabolic disorders, and cardiovascular mortality. Circulation Research, 116(1), pp.108–115. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajagopalan, S. and Brook, R.D., 2012. Air pollution and type 2 diabetes: mechanistic insights. Diabetes, 61(12), pp.3037–3045.

- Rajagopalan, S., Al-Kindi, S.G. and Brook, R.D., 2018. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 72(17), pp.2054–2070.

- Requia, W.J., Adams, M.D., Koutrakis, P., 2017. Association of PM2.5 with diabetes incidence in the elderly. Environment International, 104, pp.284–290.

- Shah, A.S.V., Langrish, J.P., Nair, H., McAllister, D.A., Hunter, A.L., Donaldson, K., Newby, D.E. and Mills, N.L., 2013. Global association of air pollution and heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet, 382(9897), pp.1039–1048. [CrossRef]

- Shaddick, G., Thomas, M.L., Mudu, P., Ruggeri, G. and Gumy, S., 2020. Half the world’s population are exposed to increasing air pollution. NPJ Climate and Atmospheric Science, 3(1), pp.1–5. [CrossRef]

- Simoni, M., Baldacci, S., Maio, S., Cerrai, S., Sarno, G. and Viegi, G., 2015. Adverse effects of outdoor pollution in the elderly. Journal of Thoracic Disease, 7(1), pp.34–45. [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, M., Andersen, Z.J., Nordsborg, R.B., Becker, T., Tjonneland, A., Overvad, K. and Raaschou-Nielsen, O., 2012. Road traffic noise and incident myocardial infarction: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One, 7(6), p.e39283. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonne, C., Elbaz, A., Beevers, S., Singh-Manoux, A. and Dugravot, A., 2014. Traffic-related air pollution in relation to cognitive function in older adults. Epidemiology, 25(5), pp.674–681. [CrossRef]

- Turner, M.C., Jerrett, M., Pope III, C.A., Krewski, D., Gapstur, S.M., Diver, W.R., Beckerman, B.S., Marshall, J.D. and Burnett, R.T., 2016. Long-term ozone exposure and mortality in a large prospective study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 193(10), pp.1134–1142.

- Vohra, K., Vodonos, A., Schwartz, J., Marais, E.A., Sulprizio, M.P. and Mickley, L.J., 2021. Global mortality from outdoor fine particle pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion: Results from GEOS-Chem. Environmental Research, 195, p.110754. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Aaron, C.P., Madrigano, J., Hoffman, E.A., Angelini, E., Yang, J., Laine, A., Shea, S. and Vedal, S., 2019. Association between long-term exposure to ambient air pollution and change in quantitatively assessed emphysema and lung function. JAMA, 322(6), pp.546–556. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO (World Health Organization), 2021. Air pollution. [online] Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ambient-(outdoor)-air-quality-and-health [Accessed 17 May 2025].

- WHO, 2018. Ambient air pollution: Health impacts. Geneva: World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/airpollution/ambient/health-impacts/en/ [Accessed 17 May 2025].

- World Bank, 2020. Air Quality Management in Pakistan. [online] Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org [Accessed 17 May 2025].

- Xie, Y., Bowe, B., Yan, Y., Al-Aly, Z., 2019. Burden of cause-specific mortality associated with PM2.5 air pollution in the United States. JAMA Internal Medicine, 179(11), pp.1521–1529.

- Yang, W.S., Zhao, H., Wang, X., Deng, Q., Fan, W.Y. and Wang, Y., 2014. An evidence-based review of the relationship between long-term exposure to air pollution and cardiovascular disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 11(7), pp.6840–6860.

- Yin, P., Brauer, M., Cohen, A., Burnett, R.T., Liu, J., Liu, Y., Liang, R., Wang, W., Qi, J., Wang, L. and Zhou, M., 2017. The effect of air pollution on deaths, disease burden, and life expectancy across China and its provinces. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(39), pp.10384–10389.

- Zhang, Z., Laden, F., Forman, J.P., Hart, J.E., 2016. Long-term exposure to particulate matter and self-reported hypertension: a prospective analysis in the Nurses’ Health Study. Environmental Health Perspectives, 124(9), pp.1414–1420. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Wang, J., Shen, L., Yang, Y. and Wu, J., 2020. Assessing the impact of air pollutants on hospital admissions for cardiovascular disease in Wuhan, China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), p.2452.

- Zhou, M., Wang, H., Zhu, J., Chen, W., Wang, L., Liu, S., Li, Y., Wang, L., Yang, G., Wang, Y. and Liang, X., 2016. Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990–2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet, 387(10015), pp.251–272. [CrossRef]

- Brook, R.D., Newby, D.E., Rajagopalan, S., 2017. The global threat of outdoor ambient air pollution to cardiovascular health: time for intervention. JAMA Cardiology, 2(4), pp.353–354.

- Nawaz, M., Rana, I.A., Sadiq, M.A. and Mahmood, A., 2019. Public perception and response to smog in Lahore: A case of environmental hazard in Pakistan. Sustainability, 11(7), p.1939.

- Manisalidis, I., Stavropoulou, E., Stavropoulos, A. and Bezirtzoglou, E., 2020. Environmental and health impacts of air pollution: a review. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, p.14. [CrossRef]

- Dominici, F., Peng, R.D., Bell, M.L., Pham, L., McDermott, A., Zeger, S.L. and Samet, J.M., 2006. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA, 295(10), pp.1127–1134. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghauri, B., Lodhi, A. and Mansha, M., 2007. Development of baseline (air quality) data in Pakistan. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 127(1–3), pp.237–252. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knol, A.B., de Hartog, J.J., Boogaard, H., Slottje, P., van der Sluijs, J.P., Lebret, E., Cassee, F.R., Wardekker, J.A. and Kruize, H., 2009. Expert elicitation on ultrafine particles: likelihood of health effects and causal pathways. Particle and Fibre Toxicology, 6(1), p.19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, 2021. Punjab Environmental Profile 2020–21. Government of Pakistan. Available at: https://www.pbs.gov.pk [Accessed 17 May 2025].

- Rasheed, A., Khoso, A.R., Butt, Q. and Sheikh, S.A., 2023. Urban smog in Pakistan: sources, health risks and mitigation strategies. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30, pp.54521–54535.

- Salim, W., Sheikh, R. and Kazmi, S.J.H., 2022. Association of ambient air quality with cardiovascular disease: a case study from Lahore, Pakistan. Pakistan Journal of Public Health, 12(3), pp.99–104.

- Ali, M., Ahmed, M. and Yousaf, A., 2020. Evaluation of air quality in urban areas of Pakistan during winter months: A case study of Lahore. International Journal of Environmental Studies, 77(6), pp.997–1010.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).