1. Introduction

There is a global transition from petroleum-based plastics to bio-based and biocompostable plastics. Many countries have adopted relevant standards for the net zero carbon transition, and plastics have been shown to be low carbon throughout their life cycle [

1].

Polylactide is currently one of the most represented bio-based plastics on the commercial market (probably second only to the group of polyhydroxyalkanoates [

2]), and its production is being increased by several companies, such as Nature Works LLC, which will reach a capacity of 150 kt in 2021. The expected annual world production of PLA in 2027 is 6.6 million tons [

3]. However, this represents close to 1% of annual plastic production, indicating the growth potential to replace petroleum-based plastics.

Polylactide is currently used in packaging, biomedical devices, agricultural films, and additive manufacturing technologies, particularly 3D printing. However, its potential in the coatings industry, which is considered one of the most important polymer applications, is not yet realized, primarily as a film-forming agent. And there are several notable factors that limit this application. As is well known, the modern paint and coating industry works with several classes of systems: solvent-based systems (anticorrosion coatings and some wood coatings, plastic coatings, etc.), high-solids systems (without liquid carriers or with a significantly reduced quantity) and water-based systems (the polymer particles are dispersed and stabilized in water). The latter solution is the most ecological, helping to reduce the content of harmful volatile organic compounds. An obstacle to the use of polylactide in the composition of mortar paints is the relatively small number of solvents compatible with this polymer, which causes problems of adequate selection and impossibility of using traditional industrial systems of aromatic, medium-polar solvents with reduced toxicity. However, an obstacle to obtaining PLA dispersions is that PLA, unlike currently commercialized acrylic, polyurethane, or alkyd dispersions [

4,

5], cannot be synthesized in a similar way from a monomer using radical reactions. There is a global transition from petroleum-based plastics to bio-based and biocompostable plastics. Many countries have adopted relevant standards for the net zero carbon transition, and plastics have been shown to be low carbon throughout their life cycle [

1].

The method of solvent evaporation allows dispersions of polymer particles with a high solid content to be obtained and consists of successive preparation of a polylactide solution and its dispersion (mechanical and ultrasonic) in aqueous medium. It results in stabilization of the dispersion particles by surfactants and thickeners, and in the last step, the removal of solvent from the dispersion particles by continuous evaporation takes place [

6,

7]. Although this method uses a solvent, it can be captured and regenerated in analogy to the smoothing processes of printed 3D parts [

8,

9]. The dispersions obtained in this way can form films at elevated temperatures compared to room temperature, as the glass transition temperature (T

g) of modern polylactide grades is between 55 and 65 ° C [

10] and the minimum film formation temperature (MFFT) is between the T

g and the melting point of the polymer (T

m). For all applications of polylactide, from coatings that cure at elevated temperatures to those that do not require heating for film formation, reducing the MFFT is therefore an important challenge. Plasticizers are known to reduce T

g and Tm by reducing intermolecular interactions between polymer chains, so their introduction can be considered a promising tool for reducing MFFT.

There are several known ways to plasticize polylactide: 1) by combining it with other more elastic polymers, eg natural rubber [

11], polycaprolactone [

12] or poly-butylene succinate adipate [

11], both by melt compounding and chemical grafting; 2) by introducing monomeric or oligomeric plasticizers, eg polyethylene glycol (PEG) [

13], citrates [

14] and adipates [

15], or oligomeric lactic acid, which has been shown to decrease T

g of PLA by 35 °C at 25 wt. % content [

16]. The low-molecular-weight plasticizers are more technological because the additive concentration can be controlled according to the desired glass transition temperature reduction so that other important properties such as hardness, heat resistance, tackiness, etc. are not affected.

The best known and most studied plasticizer for PLA is polyethylene glycol [

17], but it is also water soluble, which can cause its transfer from dispersed PLA particles to the aqueous phase. The same is true for plasticizers such as glycerin, ethylene glycol, etc. Such a transition would not be a problem if the plasticizers were concentrated on the surface of the PLA particles after evaporation of the water, but because they are low-molecular-weight liquids, they can be absorbed by the substrate or coalesce into droplets separate from the polymer, forming macroheterogeneous regions. Another problem is the gradual migration of this plasticizer, especially in humid conditions [

18]. Thus, effective plasticizers for polylactide particles are derived from aqueous dispersions that are not water soluble.

The aim of this work is to improve the technology of obtaining coatings based on plasticized polylactide from its aqueous suspensions. For this purpose, aqueous dispersions of polylactide were obtained, the application process was developed, film formation was studied, and the influence of plasticizers on the film formation temperature was investigated. The efficiency of plasticizers for PLA based on water-insoluble epoxidized fatty acids (oleic and linoleic) was demonstrated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The polylactide used in this study was Ingeo Biopolymer 4060D (NatureWorks, USA) with a density of 1.24 g/cm3, a glass transition temperature of 55–60 °С, an average molecular weight (Mw) of 190 kD, and a D-lactide content of 12%. This grade was chosen for its relatively low glass transition point, which arises from the amorphous structure and exceeds its suitability for film applications.

PEG-400, dibutyl phthalate (DBP), ethylene glycol (EG), and glycerin were used as plasticizers. PEG-400 is one of the most widely used and effective plasticizers for PLA polymers [

19,

20,

21] it was chosen as a reference. Although DBP is a fossil-based phthalate plasticizer, it is known to be compatible with a wide range of polymers, so it was chosen as a historical reference. Ethylene glycol and glycerol have been used in some research [

22]. All named substances were purchased from the local supplier HLR Ukraine (Chemlaborreactiv LLC).

Oleic acid and linoleic acid were used for the synthesis of epoxy-oleic acid and epoxy-linoleic acid, respectively. The solvent used was dichloromethane (methylene chloride) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (m-CPBA) (Sigma-Aldrich), sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich), and anhydrous sodium sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich) were used for the synthesis of epoxy-oleic and epoxy-linoleic acids, respectively. High-performance liquid chromatography-grade hexane and ethyl acetate (Sigma-Aldrich) were used for chromatography.

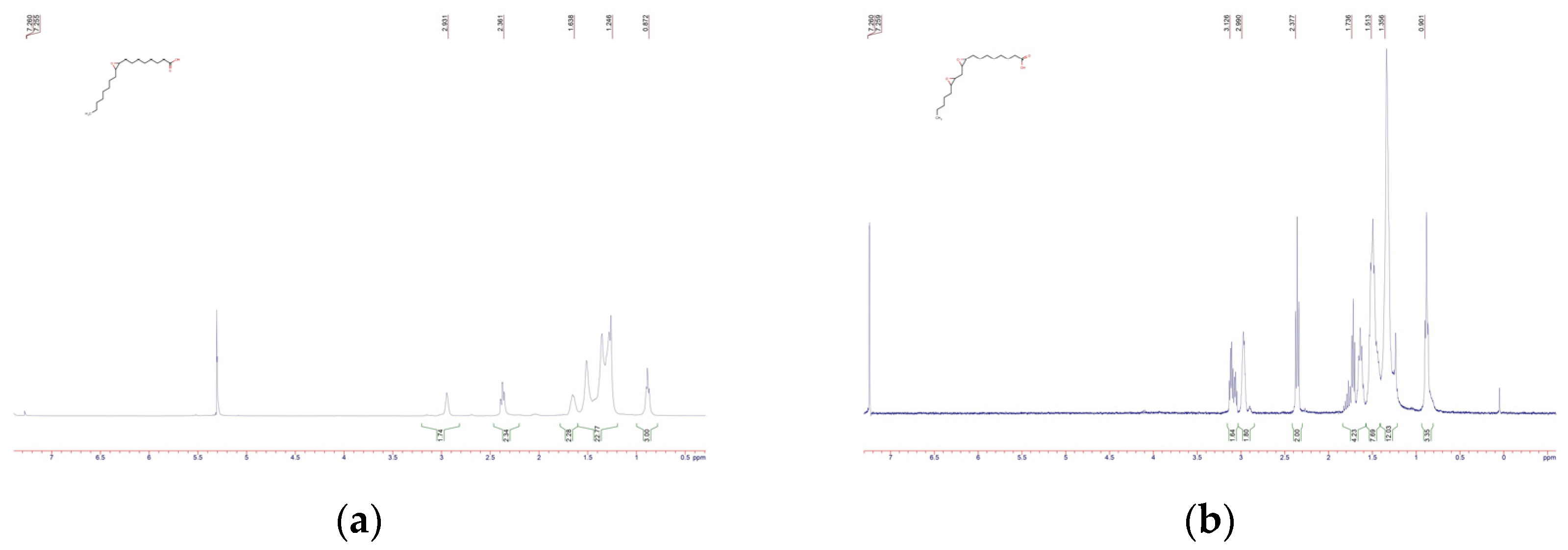

2.2. Epoxidized Plasticizers Synthesis and Characterization

Oleic acid (5 g, 0.018 mol, 1 eq.) was mixed with 50 mL of dry dichloromethane (CH

2Cl

2) in a three-necked flask at room temperature, followed by m-CPBA (4.6 g, 0.022 mol, 1.2 eq., 70 wt. %) under constant stirring. The reaction was left to stir for 16 hours at room temperature. After completion of the reaction, the mixture was washed with 50 mL of unsaturated NaHCO

3 solution and distilled water (3×30 mL), dried over anhydrous Na

2SO

4, filtered, and the solvent evaporated under vacuum. Purification was carried out by column chromatography (hexane/ethyl acetate 9:1) to give 4.1 g (80-90%) of oleic acid epoxide, which was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy (

Figure 1a): δ 2.91 (s, 2H), 2.37 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.7–1.58 (m, 3H), 1.5 (s, 7H), 1.43–1.15 (m, 23H), 0.94–0.87 (m, 3H). The same method was used to synthesize epoxy linoleic acid, and the result was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy (

Figure 1b).

The analysis of proton magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra revealed significant changes in the chemical environment of hydrogen atoms, confirming the successful course of the epoxidation reaction. In the spectrum of the initial unsaturated carboxylic acid (compound C18H34O2), characteristic signals are recorded in the range of δ ~ 5.3 ppm, corresponding to the protons of the alkene group (–CH=CH–). After the reaction to form the compound (C18H34O3), these signals disappear completely, indicating the disappearance of the multiple bonds. Instead, new peaks in the range of δ ~2.7-3.2 ppm appear in the product spectrum, typical of protons associated with the epoxy fragment (–CH–O–CH–). A similar synthesis and characterization of linoleic acid was performed. Also, FTIR spectra were obtained for synthesized epoxidized organic acids (Appendix A.1).

2.3. Polylactide Dispersions Obtaining

Initially, 0.17 g of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) was dissolved in 42.86 ml of distilled water at 25 °C using a top-drive stirrer at a speed of no more than 40 rpm. Maintaining a low stirring speed was critical to prevent heavy foaming, which made it difficult to distribute the components evenly. After the surfactant (SDS) was completely dissolved, 40 ml of a 15 wt. % solution of PLA 4060D in dichloromethane was gradually added to the mixture. Dichloromethane was chosen as the solvent because of its optimal evaporation rate. The stirring process lasted for 3 hours with a gradual increase of the water bath temperature from 25 to 60 °C by 5 °C every 15 minutes, after which the system was held at 60 °C for the rest of the time. The dispersion was then stirred at low speed and vacuumed to remove residual dichloromethane. Dry particles from the dispersion were obtained by centrifugation followed by drying on an adhesive coating at room temperature. This process resulted in micrometer-sized PLA particles suitable for further research and modification for film materials.

2.4. Characterization Methods

Chemical analysis was performed by ¹H NMR spectroscopy (400 MHz, CDCl3; Bruker Avance III HD 400 MHz, equipped with a 5 mm broadband probe).

The surface topography of the obtained films was studied using a MIRA3 LMU scanning electron microscope (Tescan, Brno, Czech Republic) at 10 kV acceleration voltage and 12 pA current. To reduce the surface charge, the samples were coated with a 10 nm thick tungsten layer using a precision coating and etching system (682 PECS, Gatan, Inc., Pleasanton, CA, USA). Optical microscopy images were obtained on a Konus Academy-2 upright optical microscope using a calibrated UCMOS 1300 digital camera (Sigeta Optics, Kiev, Ukraine) and ToupView software (ToupTek, Zhejiang, China).

Hansen solubility parameters for PLA and epoxidized plasticizers were determined using the following solvents: water, dichloromethane, isopropyl alcohol, hexane, ethyl acetate, n-butanol, cyclohexane, dimethylformamide, o-xylene, and dimethyl sulfoxide or their mixtures. To determine the solubility parameters of PLA, dichloromethane and tetrahydrofuran were used as solvents. Ethyl acetate and isopropyl alcohol were used as solvents to determine the solubility parameters of epoxy-oleic acid and epoxy-linoleic acid. All these solvents except water were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck).

The coordinates of the solubility points and centers in D, P, H coordinates (Hansen sphere calculation) were calculated with Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, USA) using the HSP Excel spreadsheet prepared by Dr. Diaz de los Rios [

23,

24].

3. Results and Discussion

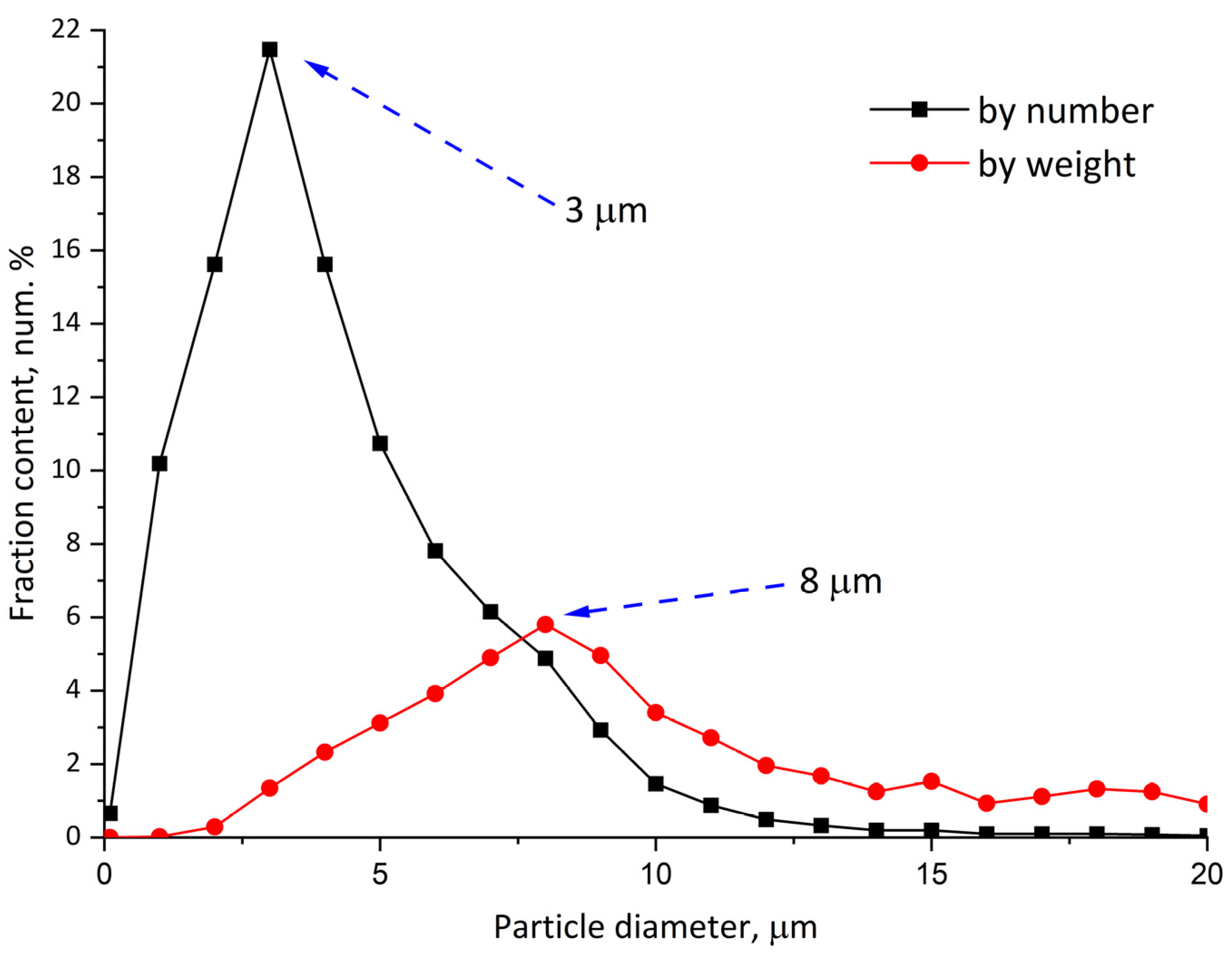

3.1. Re-Dispersable PLA Particles Characterization

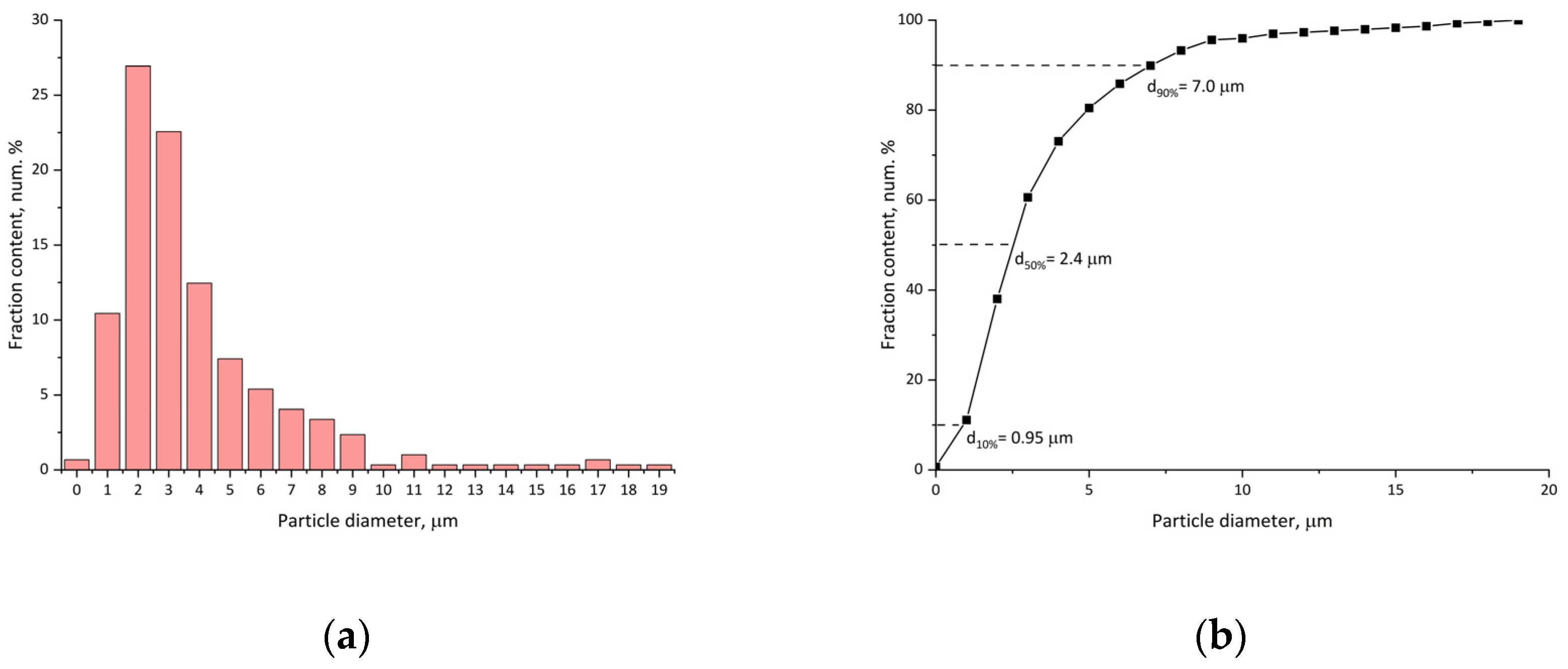

The obtained stabilized dispersion of polylactide solution in dichloromethane has an average particle size of about 3 μm and an average mass of about 8 μm (

Figure 2). The particles are stable in the purification and washing process; no coalescence is observed during the processing.

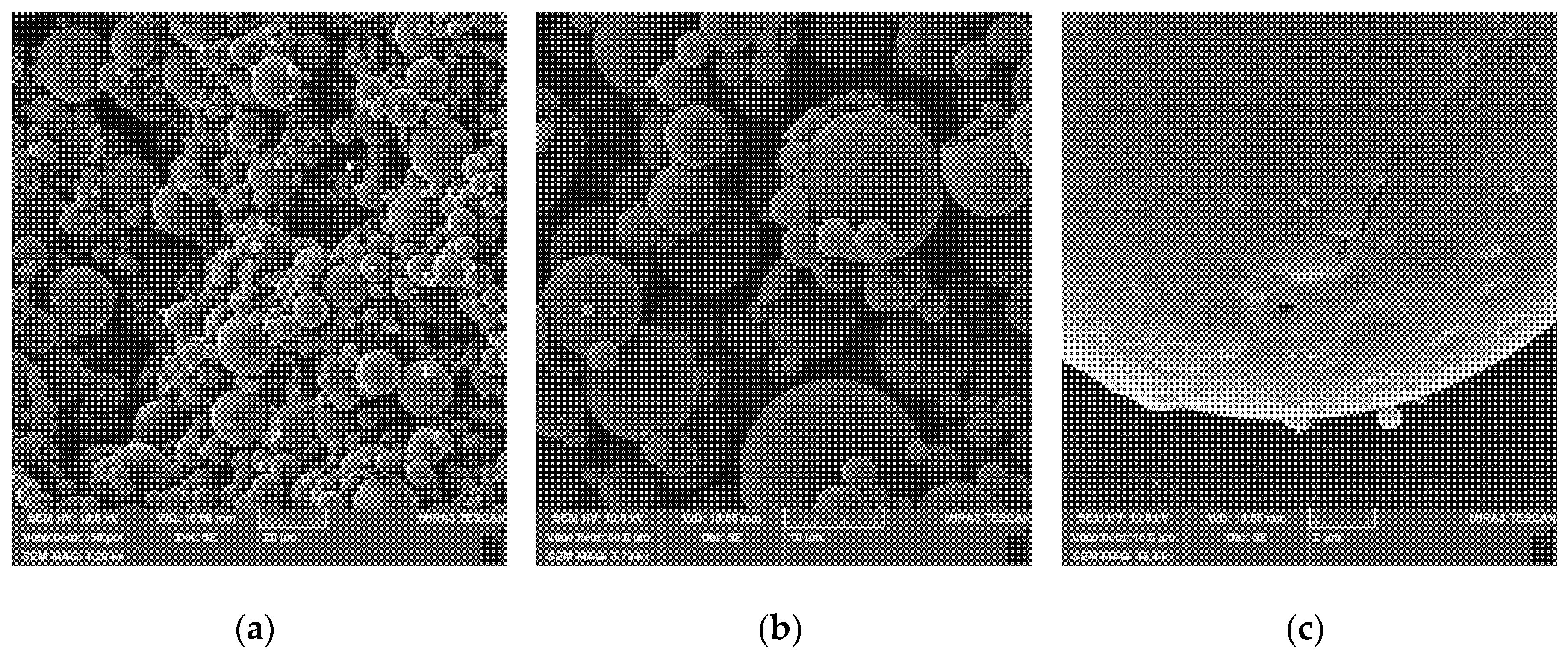

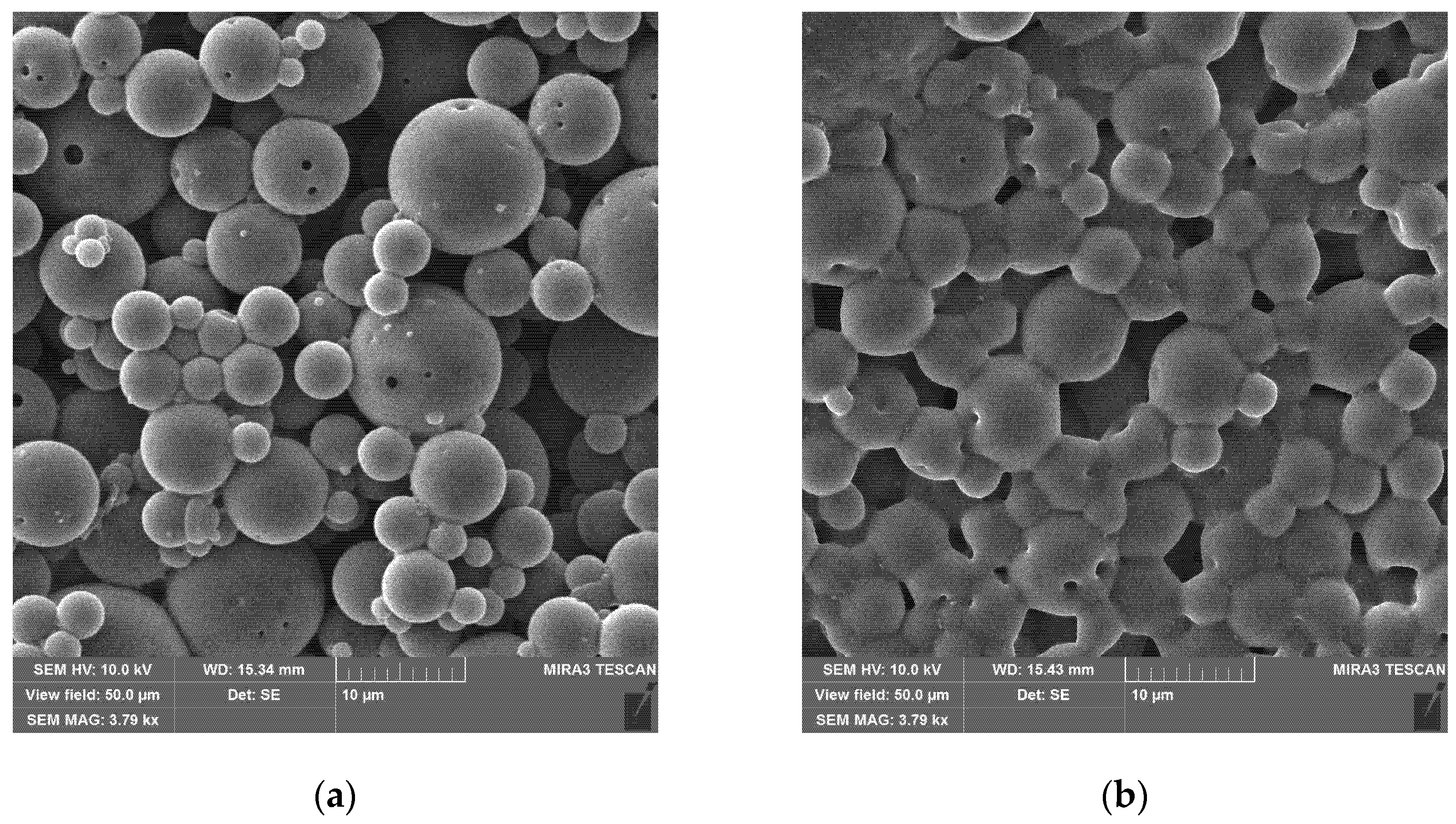

The particles obtained from the synthesis are spherical with a rather high degree of polydispersity (

Figure 3a). The size of the primary particles varies from 0.3 to 20 μm, they are significantly aggregated but without visible interstices, indicating the possibility of redispersion in the liquid.

At least some of the large particles obtained by this method are hollow (

Figure 3b, upper right) with a wall thickness of 0.2–0.4 μm. This may be due to the peculiarities of the process of removing the solvent, dichloromethane, from the emulsion droplets during particle formation. The polymer from the solution concentrates and precipitates at the interface, forming a shell, while the solvent occupies the core of the particle, which remains hollow after removal. The method of synthesizing hollow particles by evaporating the solvent from the emulsion is mentioned in some reviews [

25,

26,

27] and experimental works [

28,

29]. The surface of large particles is less uniform than that of small particles and contains thin spots, craters, in which sometimes holes are formed (

Figure 3c).

As can be seen from the particle size distribution curves (

Figure 4), despite the presence of visually coarse particles of 20 μm, the number-average particle size (d50%) is 2.4 μm and the main particle fraction is 1–7 μm. This distribution is close to that of dispersion particles, which contradicts the fact that a significant amount of particle volume (solvent) was evaporated during the preparation. Such size stability may be explained by the formation of a particle’s shell with a hollow (or porous) inner volume.

The particles obtained from the synthesis are spherical with a rather high degree of polydispersity (

Figure 4a). The size of the primary particles varies from 0.3 to 20 μm, they are significantly aggregated but without visible interstices, indicating the possibility of redispersion in the liquid.

The resulting emulsions were centrifuged, and the precipitate from the particles was washed several times with deionized water. The particles were then dried on a filter and additionally at 60 °C and sieved through a 44 μm sieve. The powder obtained is rather hygroscopic and was therefore stored in a desiccator.

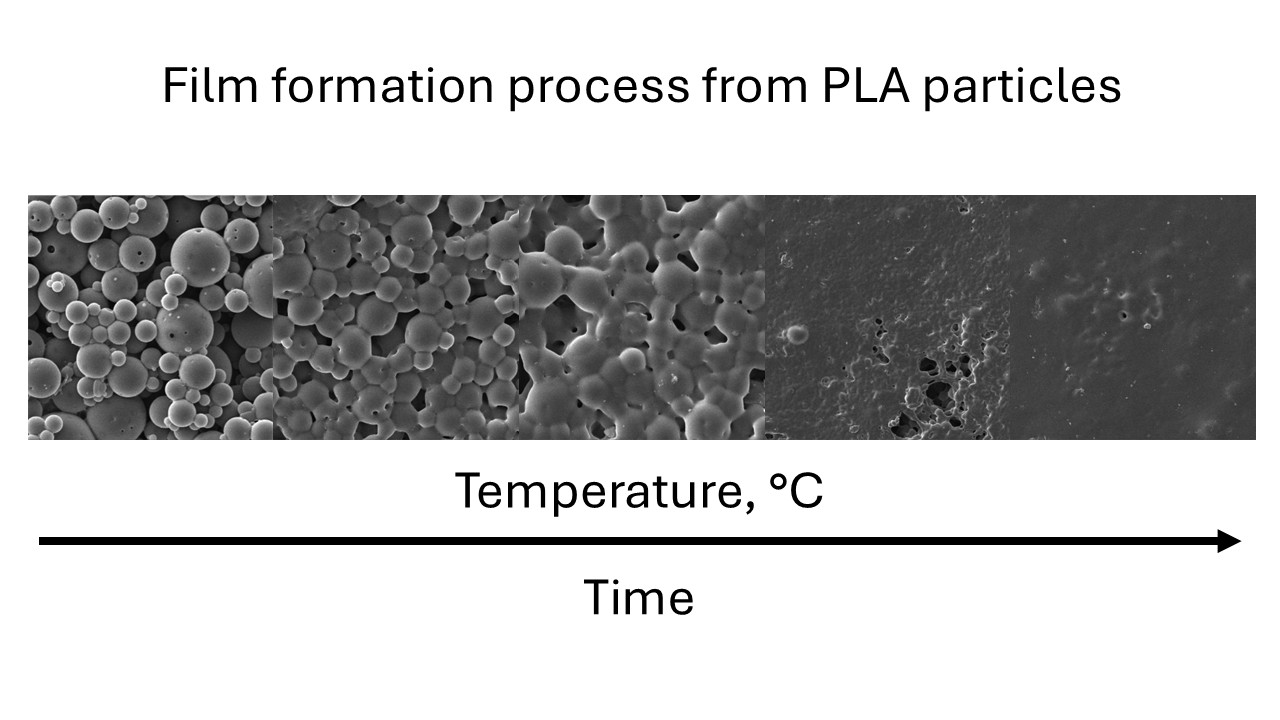

3.2. Film Formation

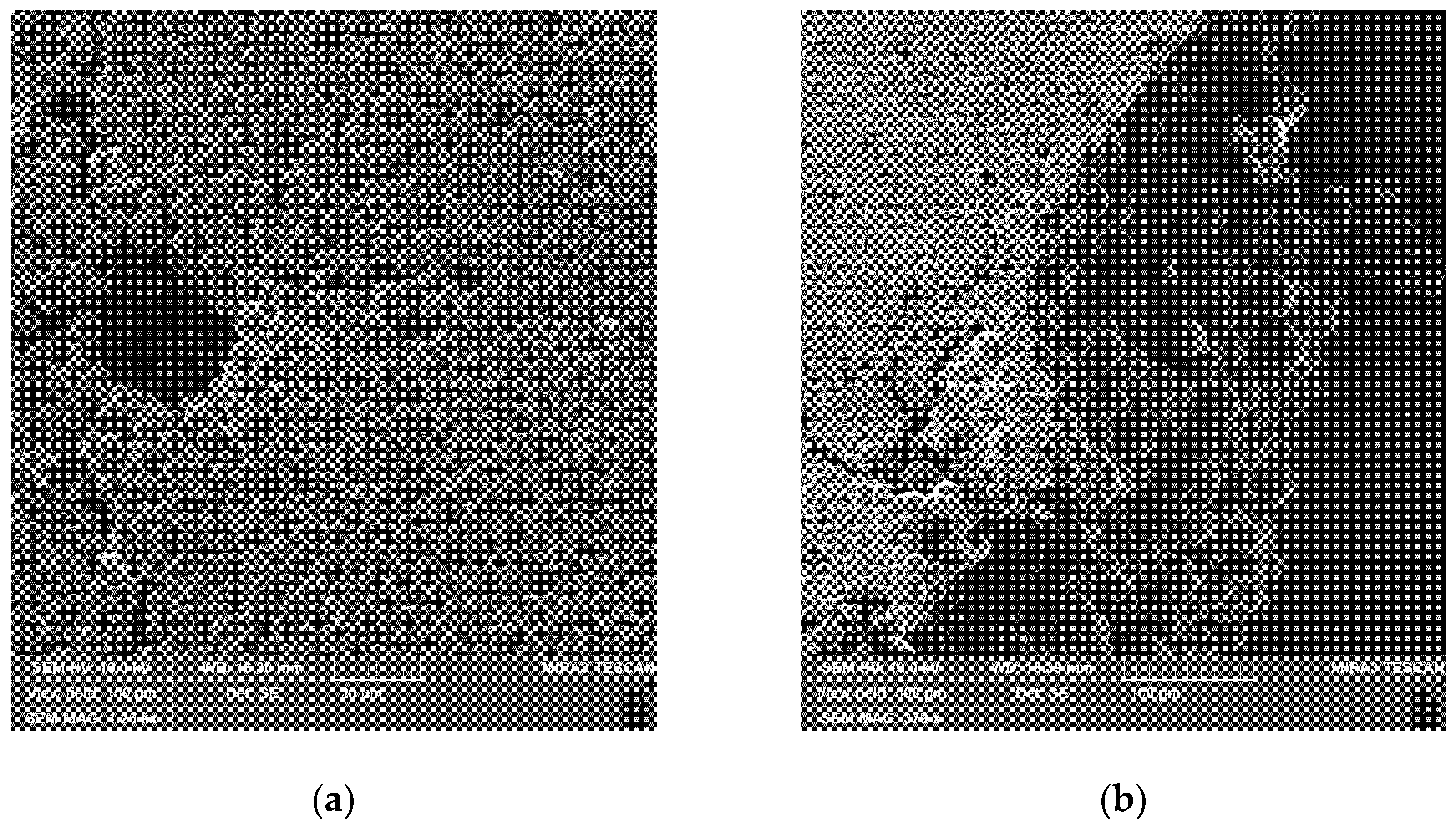

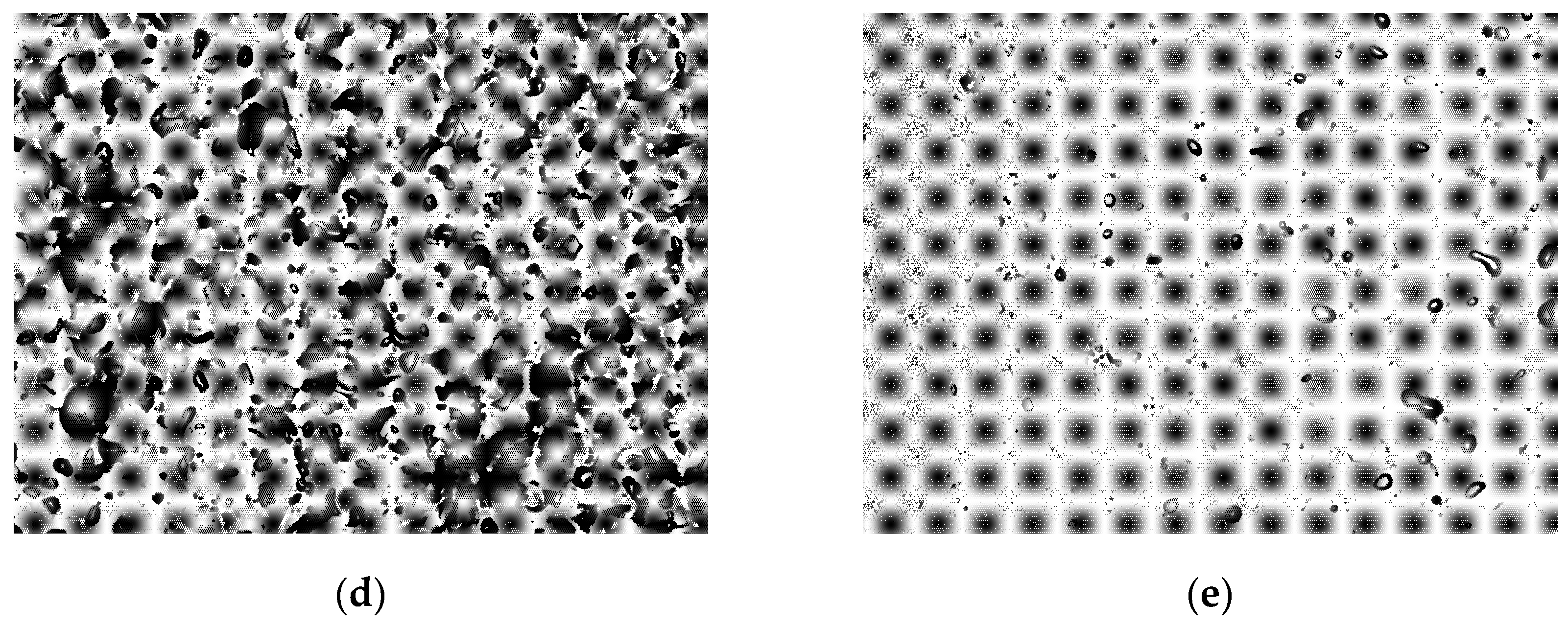

To obtain a uniform layer of particles on the glass substrate, the particles were redispersed in water, and the suspension was applied to the glass surface. After slow evaporation of the excess moisture at 80 °C, a uniform layer of densely packed particles (

Figure 5) with a thickness of 120 μm was obtained. In this layer, the presence of pores and cracks (

Figure 5a) caused by the contraction of the wet suspension during water removal is noticeable.

Figure 5b shows that at the surface of the layer, there are mainly small particles, which can be explained by the action of Stokes’ law during the sedimentation of polymer particles in water.

This effect is an artifact of the deposition technique and will be absent if, for example, a layer is obtained by air spraying.

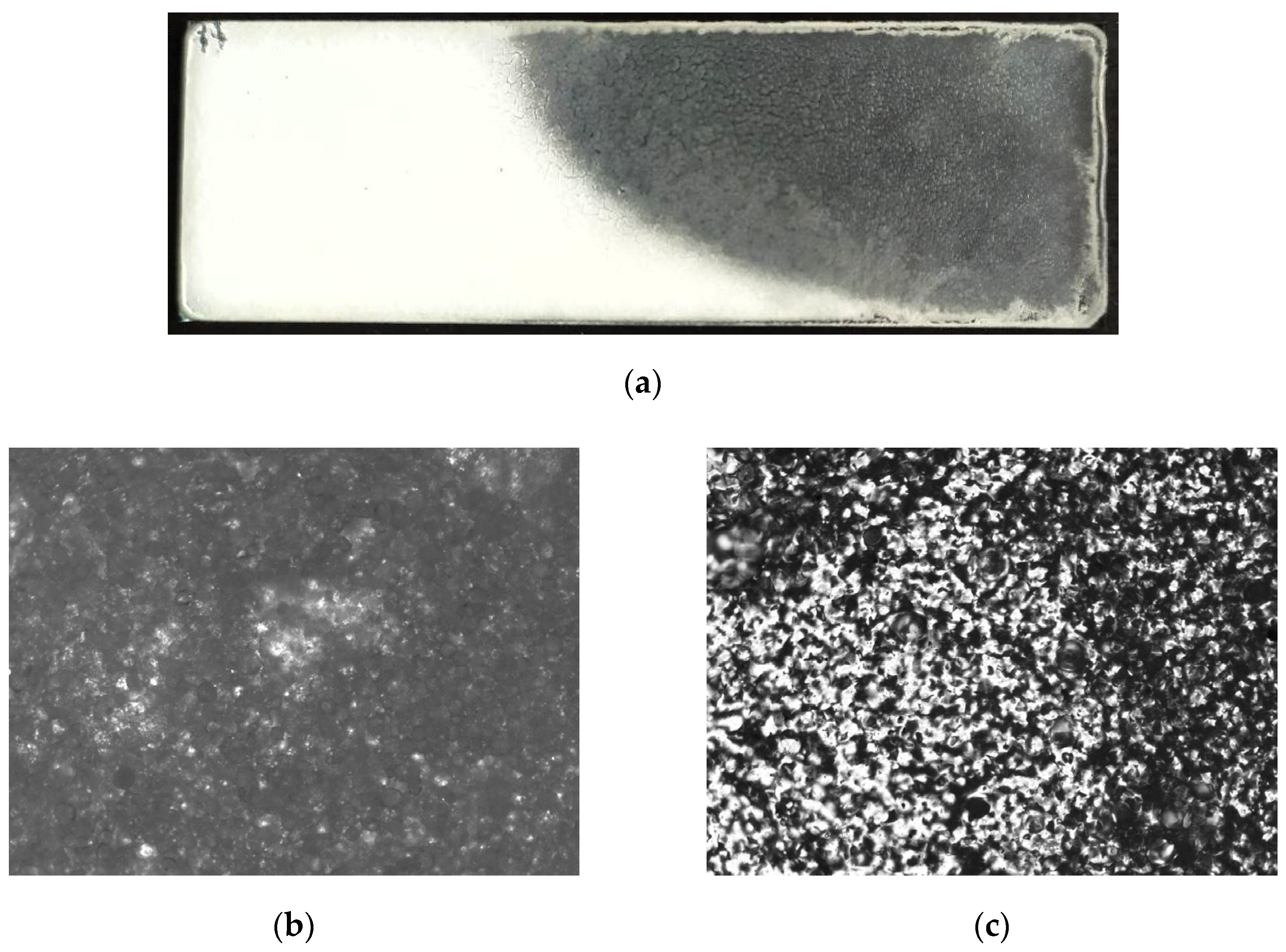

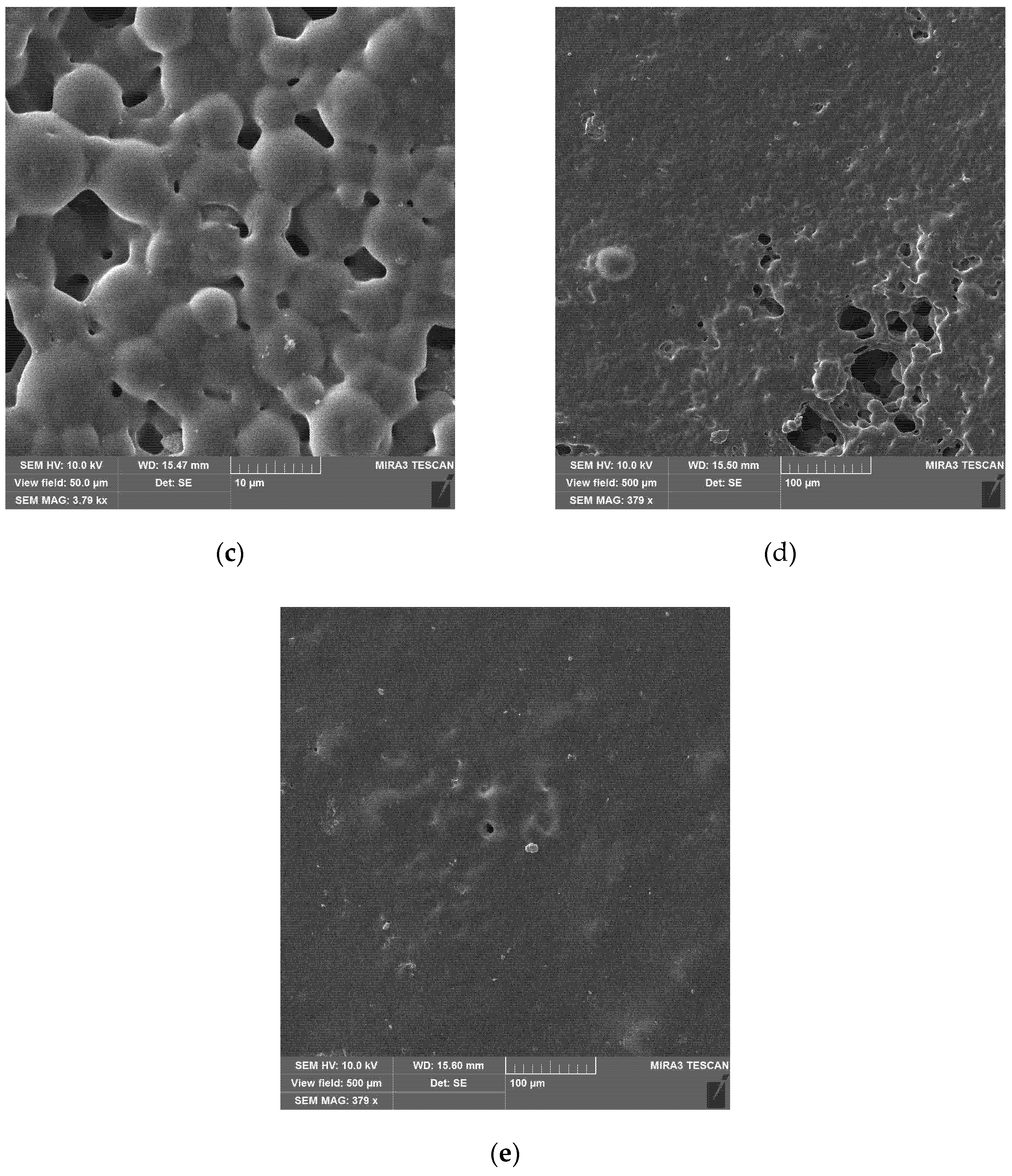

To study the process of particle fusion and the formation of a continuous layer at elevated temperatures, the glass sample obtained from the suspension was placed on a metal surface heated to 160 °C on one side, while the other side was in contact with air. This made it possible to create a temperature gradient in the sample (

Figure 6a) and to record different stages of the transition from particles to a continuous film.

In general, the effect can be divided into stages such as the fusion of particles into larger aggregates (

Figure 6b →

Figure 6c), which occurs due to the transition of the polymer into a viscous-fluid state and the surface tension of the melt. Collapse of interparticle voids and surface flattening due to melt spreading (

Figure 6c →

Figure 6d). Finally, the formation of a solid film due to the removal of residual trapped air (

Figure 6d →

Figure 6e). Both particle fusion and the removal of air from the melt are determined by the melt viscosity, which is a function of temperature. The removal of air bubbles is a time-dependent process and therefore requires that the material be held at elevated temperatures for some time. As can be seen in

Figure 6a, these process steps are accompanied by a transition of the material from opaque white to transparent white, which is caused by a change in the number of light scattering planes.

At the level of individual particles (

Figure 7), an increase in the number of holes in the craters (

Figure 7a) is observed even after a slight heating to 100 °C, which is caused by the coincidence of the increase in the molecular mobility of macromolecular segments and their highly oriented state in these meshes of the particle. Further holding at elevated temperature results in fusion of the particle shells (

Figure 7b), but the melt viscosity is still high at this stage. As the viscosity decreases, rounding of the pore walls between the particles is observed (

Figure 7c), then there is almost complete closure of the pores, except for large contract defects (

Figure 7d), which are further tightened and flattened along with surface irregularities (

Figure 7e).

The fusion process of these particles is similar to that used in powder bed fusion technologies (see e.g. [

30,

31]), with the main factors being melt viscosity and its surface tension [

32]. In addition to lowering the particle fusion temperature, the use of low-molecular-weight plasticizers will also reduce the melt viscosity and thus the film formation time.

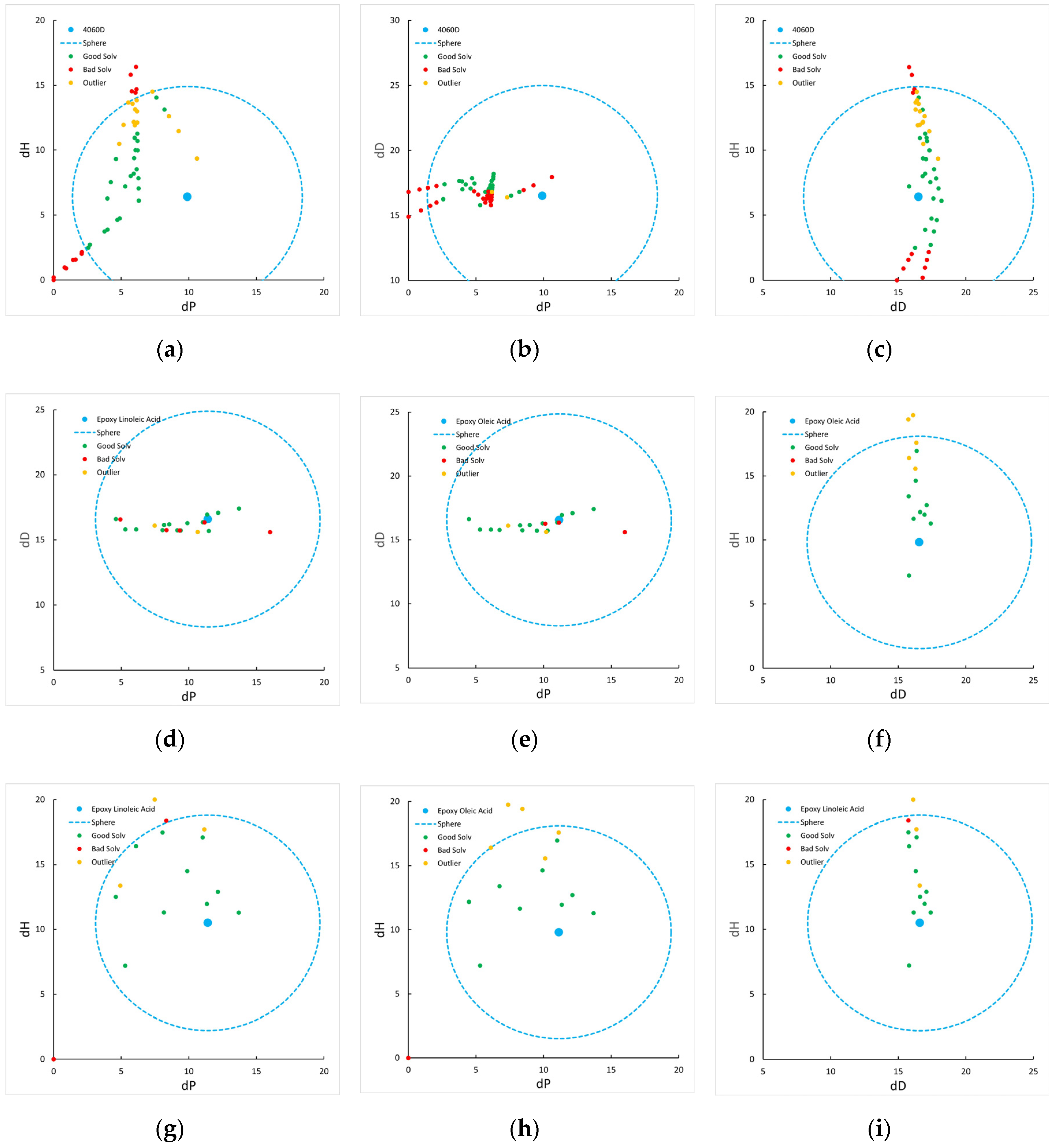

3.3. Plasticizer Effectiveness Assessment

The affinity of the plasticizer to the polymer was evaluated using the Hansen solubility parameter approach. For PLA 4060D, epoxidized acids, it was determined experimentally by cloud point technique, which allows for determining the solubility spheres (

Figure 8), and for other plasticizers, extracted from literature (

Table 1).

Since the Hansen model assumes that Ra>Ro is a condition for polymer-plasticizer compatibility, all these plasticizers are compatible with polylactide. At the same time, the epoxidized acids of all these samples are closest (except for dibutyl phthalate) to the center of the PLA solubility sphere.

The transparency temperature was determined for different polymer-plasticizer pairs. For this, the plasticizer and PLA particles were mixed in a stirrer in dry manner for 20 minutes. It was not possible to use an auxiliary solvent to disperse the plasticizer because liquids less polar than water (isopropyl alcohol, xylene, ethyl acetate) cause coagulation of the particles.

The prepared powder was sieved through a 44 μm sieve to ensure uniform plasticizer distribution. The resulting powder was then placed between two microscopic glasses on the surface of the heating table. The melting of PLA particles, as it is shown in

Figure 7 above, is a process that is accompanied by the decrease of the light scattering surfaces quantity and therefore it is visually seen when the system reaches the stage that is shown in

Figure 7d. It was noticed that the time of conditioning at each temperature is important because the particle sintering is a viscosity-dependent process and may require time at low temperatures. To account for this fact, the temperature gradually increased by 2 °C and left for 5 min before the next step.

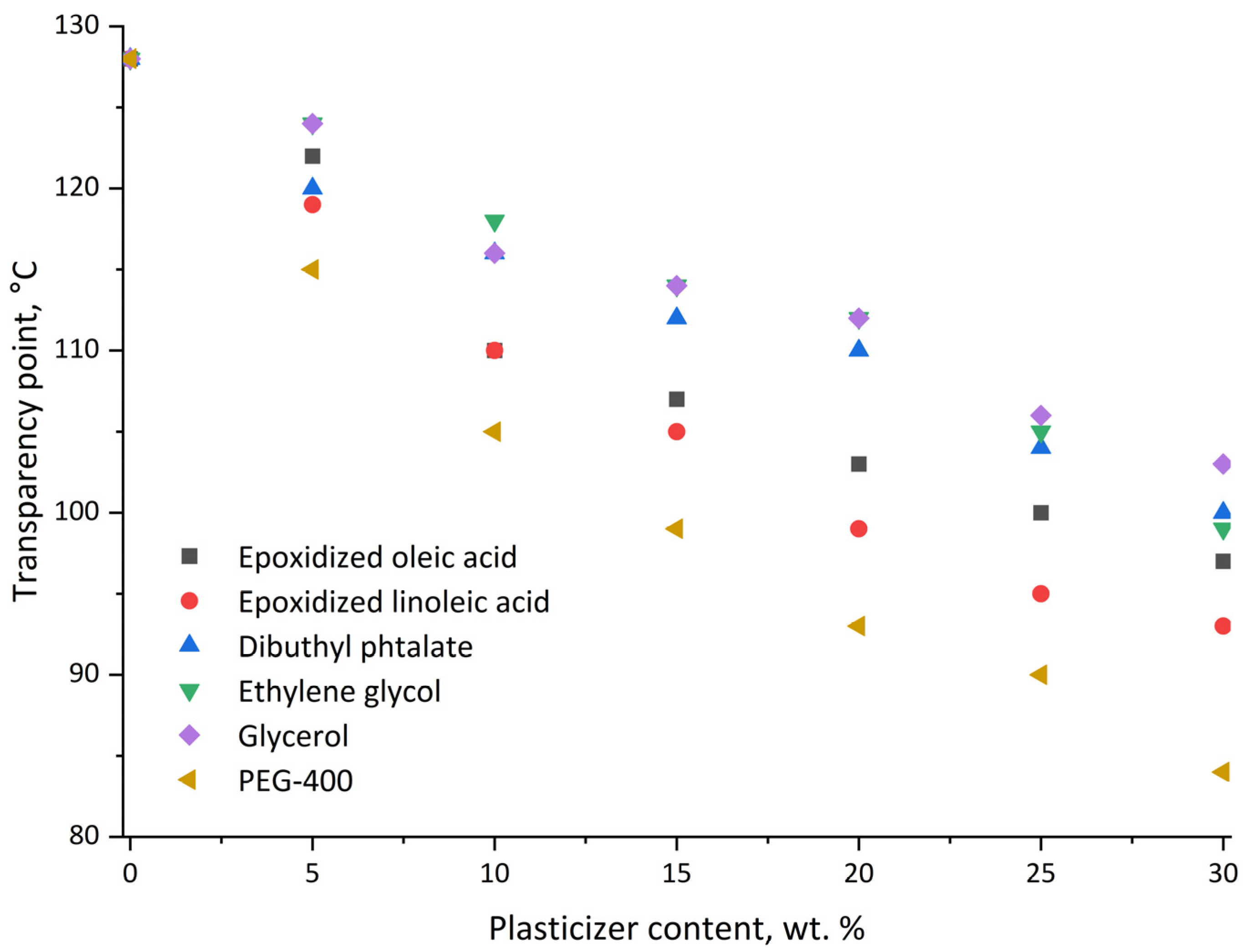

As shown in

Figure 9, all the plasticizers considered have some melting point suppression ability. The most effective is PEG 400: at an extremely high load of 30 wt. % the transparency point reaches 83 °C, at loads of 10 and 15 wt. % the melt film formation occurs around 100 °C. It's known that the introduction of plasticizers reduces the mechanical properties of polymers (and PLA in particular [

35]), so the minimum effective concentration should be chosen.

The synthesized epoxidized linoleic acid comes closest to PEG-400 efficiency. It achieves comparable efficiencies with 5 wt. % more loading. Epoxidized oleic acid is less effective in melting point suppression and requires 7-8 wt. % more to be comparable to PEG-400. Monomeric ethylene glycol and glycerin are significantly less effective than epoxidized plasticizers, which may be explained by a higher RED, indicating a lower affinity compared to other plasticizers. However, this assumption does not hold for dibutyl phthalate, which has a RED value of 0.44.

Thus, during the study, a dispersed material was obtained which can be the basis for the production of coatings by powder method or from aqueous dispersions. It is shown that the plasticizers (epoxidized fatty acids) synthesized in this work can reduce the film formation temperature by 20-30 °C compared to the unplasticized polymer, which puts them on a par with PEG. These plasticizers are insoluble in water, so they can potentially be incorporated into the particles at the synthesis stage in the polymer solution.

The ways to improve the results of the work are, of course, the use of more efficient dispersion methods, which will reduce the particle size and thus, in the long run, reduce the film formation temperature. As shown in [

36], at a particle size of 200–500 nm, film formation is observed at temperatures above 60 °C. Considering the possibilities of plasticizers, this temperature can be reduced at least to a temperature slightly above room temperature.

Alternatively, the technology can be adapted from the scenario of thermally cured coatings or powder coatings, which consists of sequentially applying the dispersion to the product by any suitable method, drying the aqueous phase, and then dosed heating, e.g., by infrared radiation. The amount of heat applied to the film can be adjusted to provide the required heating and cooling rates, as shown in [

37,

38], and can be used to regulate crystallization and, consequently, the mechanical properties of the polymer matrix. Plasticizers in the composition of coating particles will reduce the film formation temperature so that they can be used for 3D printed articles based on PLA.

Undoubtedly, to obtain a full-fledged technology of coatings based on polylactide, it is necessary to study the possibility of obtaining filled composites, more precise regulation of melt viscosity to increase flowability, as well as control of shrinkage during crystallization, which is not so critical in the production of free films, but a big problem in obtaining coatings on substrates.

4. Conclusions

The paper considers the method of obtaining polylactide films based on aqueous dispersions of redispersed powders, the process of film formation with additional heating, as well as the influence of plasticizers on this process.

It is shown that using only mechanical emulsification, it is possible to obtain a material with an average particle size of 2.4 µm. At least a fraction of the particles obtained by this method are hollow.

It was found that the introduction of synthesized plasticizers – epoxidized oleic and linoleic fatty acids on the temperature of film formation: the first at 20 wt. % concentration reduces this temperature by 25 °C, and the second by 30 °C, which is comparable to the effectiveness of the classical plasticizer – polyethylene glycol, reducing it by 36 °C at the same concentration. At the same time, these plasticizers are insoluble in water and completely bio-based.

The results of the study can be used to develop the technology of water-dispersion coatings based on polylactide, both those intended for curing at ambient temperature and those that require heating.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.M. and V.V.; methodology, O.M.; validation, O.M. and D.B.; formal analysis, O.M. and D.B.; investigation, O.M., D.B. and A.B.; resources, O.M. and V.V.; data curation, O.M., D.B., A.B., I.S., V.H., I.T.; writing—original draft preparation, O.M., D.B. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, O.M. and D.B.; visualization, D.B.; supervision, O.M.; project administration, O.M. and V.V.; funding acquisition, O.M. and V.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine, agreement number RN/53-2024 (26.09.2024) (European Union aid instrument for fulfilling Ukraine's obligations in the Framework Program of the European Union for Scientific Research and Innovation "Horizon 2020).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PLA |

Polylactide |

| PEG |

Minimum film forming temperature |

| DBP |

Dibutyl phthalate |

| EG |

Ethylene glycol |

| m-CPBA |

Meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid |

| SDS |

Sodium dodecyl sulfate |

| RED |

Relative energy difference |

Appendix A

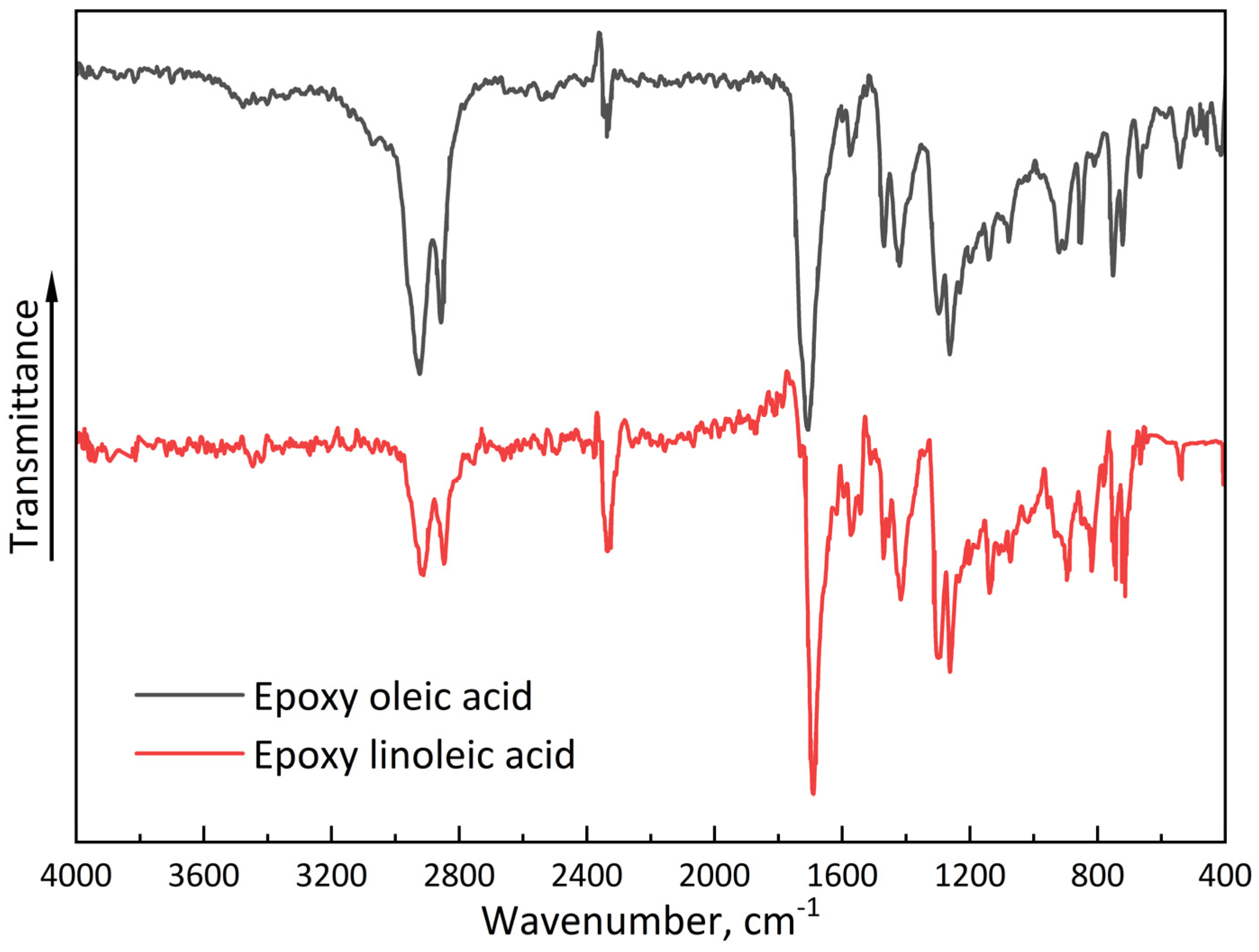

Figure A1.

FTIR spectra of epoxy oleic acid and epoxy linoleic acid.

Figure A1.

FTIR spectra of epoxy oleic acid and epoxy linoleic acid.

References

- Ghomi, E.R.R.; Khosravi, F.; Ardahaei, A.S.S.; Dai, Y.; Neisiany, R.E.; Foroughi, F.; Wu, M.; Das, O.; Ramakrishna, S. The Life Cycle Assessment for Polylactic Acid (PLA) to Make It a Low-Carbon Material. Polymers 2021, 13, 1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balla, E.; Daniilidis, V.; Karlioti, G.; Kalamas, T.; Stefanidou, M.; Bikiaris, N.D.; Vlachopoulos, A.; Koumentakou, I.; Bikiaris, D.N. Poly(Lactic Acid): A Versatile Biobased Polymer for the Future with Multifunctional Properties—From Monomer Synthesis, Polymerization Techniques and Molecular Weight Increase to PLA Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, L.V.; Bomtempo, J.V.; De Almeida Oroski, F.; De Andrade Coutinho, P.L. The Diffusion of Bioplastics: What Can We Learn from Poly(Lactic Acid)? Sustainability 2023, 15, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaria-Echart, A.; Fernandes, I.; Barreiro, F.; Corcuera, M.A.; Eceiza, A. Advances in Waterborne Polyurethane and Polyurethane-Urea Dispersions and Their Eco-Friendly Derivatives: A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ge, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, T.; Lin, J.; Zhao, C.X.; Wang, B.; Zhu, G.; Guo, Z. Waterborne Acrylic Resin Modified with Glycidyl Methacrylate (GMA): Formula Optimization and Property Analysis. Polymer 2018, 143, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandera, D.; Meyer, V.; Prevost, D.; Zimmermann, T.; Boesel, L. Polylactide/Montmorillonite Hybrid Latex as a Barrier Coating for Paper Applications. Polymers 2016, 8, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xiang, S.; Luan, Q.; Bao, Y.; Deng, Q.; Zheng, M.; Liu, S.; Song, J.; Tang, H.; Huang, F. Development of Poly (Lactic Acid) Microspheres and Their Potential Application in Pickering Emulsions Stabilization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 108, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.; Kishore, S.R.; Tomy, A.T.; Sugavaneswaran, M.; Scholz, S.G.; Elkaseer, A.; Wilson, V.H.; Rajan, A.J. Vapour Polishing of Fused Deposition Modelling (FDM) Parts: A Critical Review of Different Techniques, and Subsequent Surface Finish and Mechanical Properties of the Post-Processed 3D-Printed Parts. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizon, J.R.C.; Gache, C.C.L.; Cascolan, H.M.S.; Cancino, L.T.; Advincula, R.C. Post-Processing of 3D-Printed Polymers. Technologies 2021, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G.; Vogel, E.; Smith, M. Glass Transitions in Polylactides. Polym. Rev. 2008, 48, 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, I.; Ronkay, F.; Lendvai, L. Highly Toughened Blends of Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) and Natural Rubber (NR) for FDM-Based 3D Printing Applications: The Effect of Composition and Infill Pattern. Polym. Test. 2021, 99, 107205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddeo, M.; Sorrentino, A.; Pappalardo, D. Thermo-Rheological and Shape Memory Properties of Block and Random Copolymers of Lactide and Ε-Caprolactone. Polymers 2021, 13, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafie, M.; Marsilla, K.K.; Hamid, Z.; Rusli, A.; Abdullah, M. Enhanced Mechanical Properties of Plasticized Polylactic Acid Filament for Fused Deposition Modelling: Effect of in Situ Heat Treatment. Prog. Rubber Plast. Recycl. Technol. 2019, 36, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gálvez, J.; Aguirre, J.C.; Salazar, M.H.; Mondragón, B.V.; Wagner, E.; Caicedo, C. Effect of Extrusion Screw Speed and Plasticizer Proportions on the Rheological, Thermal, Mechanical, Morphological and Superficial Properties of PLA. Polymers 2020, 12, 2111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirai, M.A.; Grossmann, M.V.E.; Mali, S.; Yamashita, F.; Garcia, P.S.; Müller, C.M.O. Development of Biodegradable Flexible Films of Starch and Poly(Lactic Acid) Plasticized with Adipate or Citrate Esters. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 92, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos, N.; Martino, V.P.; Jiménez, A. Characterization and Ageing Study of Poly(Lactic Acid) Films Plasticized with Oligomeric Lactic Acid. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2012, 98, 651–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Ren, J.; Cao, E.; Fu, X.; Guo, W. Plasticizing Effect of Poly(Ethylene Glycol)s with Different Molecular Weights in Poly(Lactic Acid)/Starch Blends. Journal of Applied Polymer Science 2015, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliotta, L.; Vannozzi, A.; Panariello, L.; Gigante, V.; Coltelli, M.-B.; Lazzeri, A. Sustainable Micro and Nano Additives for Controlling the Migration of a Biobased Plasticizer from PLA-Based Flexible Films. Polymers 2020, 12, 1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-M.; Choi, M.-C.; Han, D.-H.; Park, T.-S.; Ha, C.-S. Plasticization of Poly(Lactic Acid) (PLA) through Chemical Grafting of Poly(Ethylene Glycol) (PEG) via in Situ Reactive Blending. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 2356–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Weng, Y.; Zhang, C. Recent Advancements in Bio-Based Plasticizers for Polylactic Acid (PLA): A Review. Polymer Testing 2024, 108603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septevani, A.A.; Bhakri, S. Plasticization of Poly(Lactic Acid) Using Different Molecular Weight of Poly(Ethylene Glycol). AIP Conf. Proc. 2017, 1904, 020038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belyamani, I.; Najemi, L.; Wilson, K.; Abdullah, M.; Al-Badi, N. Influence of Glycerol and Clove Essential Oil on the Properties and Biodegradability of Poly(Lactic Acid)/Poly(Hydroxybutyrate-Co-Hydroxyvalerate) Blends. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, 142698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Ríos, M.D.; Belmonte, R.M. Extending Microsoft Excel and Hansen Solubility Parameters Relationship to Double Hansen’s Sphere Calculation. SN Applied Sciences 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Ríos, M.D.; Ramos, E.H. Determination of the Hansen Solubility Parameters and the Hansen Sphere Radius with the Aid of the Solver Add-in of Microsoft Excel. SN Applied Sciences 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulingam, T.; Foroozandeh, P.; Chuah, J.-A.; Sudesh, K. Exploring Various Techniques for the Chemical and Biological Synthesis of Polymeric Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramli, R.A. Hollow Polymer Particles: A Review. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 52632–52650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuji, M.; Han, Y.S.; Takai, C. Synthesis and Applications of Hollow Particles. KONA Powder Part. J. 2013, 30, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raichur, A.; Nakajima, Y.; Nagaoka, Y.; Maekawa, T.; Kumar, D.S. Hollow Polymeric (PLGA) Nano Capsules Synthesized Using Solvent Emulsion Evaporation Method for Enhanced Drug Encapsulation and Release Efficiency. Mater. Res. Express 2014, 1, 045407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Yu, Y.; Han, W.; Zhu, L.; Si, T.; Wang, H.; Li, K.; Sun, Y.; He, Y. Solvent Evaporation Self-Motivated Continual Synthesis of Versatile Porous Polymer Microspheres via Foaming-Transfer. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 615, 126239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivadas, B.O.; Ashcroft, I.; Khlobystov, A.N.; Goodridge, R.D. Laser Sintering of Polymer Nanocomposites. Adv. Ind. Eng. Polym. Res. 2021, 4, 277–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, F.; Yuan, S.; Chua, C.K.; Zhou, K. Development of Process Efficiency Maps for Selective Laser Sintering of Polymeric Composite Powders: Modeling and Experimental Testing. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2017, 254, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahloul, A.; Doghri, I.; Adam, L. Mesoscale Modelling of Polymer Powder Densification Due to Thermal Sintering. Appl. Math. Model. 2022, 114, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqarni, M.H.; Haq, N.; Alam, P.; Abdel-Kader, M.S.; Foudah, A.I.; Shakeel, F. Solubility Data, Hansen Solubility Parameters and Thermodynamic Behavior of Pterostilbene in Some Pure Solvents and Different (PEG-400 + Water) Cosolvent Compositions. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 331, 115700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, C.M. Hansen Solubility Parameters: A User’s Handbook,, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Solubility Parameters, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Litauszki, K.; Petrény, R.; Haramia, Z.; Mészáros, L. Combined Effects of Plasticizers and D-Lactide Content on the Mechanical and Morphological Behavior of Polylactic Acid. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belletti, G.; Buoso, S.; Ricci, L.; Guillem-Ortiz, A.; Aragón-Gutiérrez, A.; Bortolini, O.; Bertoldo, M. Preparations of Poly(Lactic Acid) Dispersions in Water for Coating Applications. Polymers 2021, 13, 2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Santis, F.; Volpe, V.; Pantani, R. Effect of Molding Conditions on Crystallization Kinetics and Mechanical Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid). Polym. Eng. Sci. 2016, 57, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tábi, T.; Ageyeva, T.; Kovács, J.G. The Influence of Nucleating Agents, Plasticizers, and Molding Conditions on the Properties of Injection Molded PLA Products. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 32, 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).