1. Introduction

Precision pesticide application in orchard environments is increasingly critical for reducing chemical overuse, environmental contamination, and exposure to non-target species [

1]. Conventional spraying methods often result in excessive pesticide use, leading to ecological degradation and the development of pesticide resistance. To address these limitations, intelligent agricultural systems that leverage robotics, sensor fusion, and machine learning have emerged as viable alternatives. Autonomous spraying robots equipped with real-time perception modules enable selective application by identifying tree structures and environmental conditions. These systems integrate multimodal sensing, including visual, infrared, and LiDAR data, to support adaptive spraying control [

2,

3]. The use of embedded AI algorithms further improves decision-making accuracy, allowing precise targeting and significant reductions in pesticide usage. A Fin Ray-inspired soft gripper with integrated force feedback and ultrasonic slip detection was developed for apple harvesting, achieving a 0% fruit damage rate when force feedback was enabled, compared to 20% without it, and demonstrating effective non-destructive picking in orchard trials [

37]. Beyond manipulation systems, these developments represent a practical advancement in smart agricultural technology within the context of industrial informatics. Recent work [

4] emphasizes the role of computer vision in automating agricultural practices such as fruit picking, disease monitoring, and spraying, which align closely with the goals of this study.

Recent advances in deep learning have significantly improved pest detection and precision pesticide application in agriculture [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Lightweight segmentation models and optimized YOLO architectures have enabled real-time inference with reduced computational complexity, facilitating deployment on edge devices in resource-constrained environments [

9,

10]. To improve small-target detection, techniques such as hybrid SGD-GA optimization and enhanced feature extraction layers have been incorporated into models like YOLOX and YOLOv7, achieving high accuracy in field conditions [

11,

12,

13]. An improved YOLOv4-based detection method was proposed for recognizing apples in complex orchard environments, significantly enhancing detection accuracy and reducing model size for efficient deployment in real-world scenarios [

27]. A high-efficiency target detection algorithm, Seedling-YOLO, was developed based on YOLOv7-Tiny to assess broccoli seedling transplanting quality, achieving a mean Average Precision (mAP@0.5) of 94.3% and a detection speed of 29.7 frames per second in field conditions [

9]. Using a ZED 2 stereo camera and YOLO V4-Tiny, a potted flower detection and localization system was implemented, yielding a mean average precision of 89.72%, a recall rate of 80%, and an average detection speed of 16 FPS, with a mean absolute localization error of 18.1 mm [

16]. Similarly, an apple detection framework integrating ShufflenetV2 and YOLOX-Tiny, enhanced with attention and adaptive feature fusion modules, achieved 96.76% average precision and operated at 65 FPS in complex orchard environments [

36]. An improved YOLOX-based method utilizing RGB-D imaging was developed for real-time apple detection and 3D localization, achieving a mean average precision of 94.09%, F1 score of 93%, and spatial positioning errors under 7 mm in X and Y axes and under 5 mm in Z axis [

38]. Advanced frameworks such as CEDAnet and Transformer-based modules have been applied to UAV-based orchard monitoring, achieving precise tree segmentation in dense canopies [

14]. Additionally, multi-sensor fusion systems integrating LiDAR, vision, and IMUs have shown promise for dynamic tree localization and pose estimation in semi-structured orchards [

15,

40]. A deep learning-based variable rate agrochemical spraying system was developed for targeted weed control in strawberry crops, utilizing VGG-16 for real-time classification of spotted spurge and shepherd’s purse, achieving a 93% complete spray rate on target weeds [

41]. These developments highlight the importance of real-time, adaptable solutions for intelligent pesticide management in modern orchard environments.

Recent advancements in deep learning have significantly enhanced plant disease and pest detection in precision agriculture. Lightweight models such as ResNet50 and MobileNetv2 have shown efficiency in image classification tasks, while YOLO-based detectors, particularly YOLOv5 and YOLOv8, have achieved high accuracy in real-time object detection [

16,

17,

18]. For tomato crops, an improved Faster R-CNN model incorporating ResNet-50, K-means clustering for anchor box optimization, and Soft-NMS achieved a mean average precision of 90.7% in detecting flowers and fruits in complex environments [

39]. Similarly, a CNN enhanced with attention mechanisms yielded 96.81% accuracy in classifying tomato leaf diseases [

23,

28], while a hybrid model combining Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling (CARS) and CatBoost algorithms estimated tomato transpiration rates with an

of 0.92 and RMSE of 0.427 g·

·

[

34]. Furthermore, a comprehensive review on CNN-based vegetable disease detection emphasized the dominance of VGG models and underscored challenges in data limitations and generalization performance [

35]. Complementary work reviewed nondestructive quality assessment in tomatoes using mechanical, electromagnetic, and electrochemical sensing integrated with deep learning [

43]. In parallel, deep learning-based approaches for apple quality assessment have achieved promising results. A multi-dimensional view processing method leveraging Swin Transformer and an enhanced YOLOv5s framework attained 94.46% grading accuracy and 96.56% defect recognition at 32 FPS [

29]. Another YOLOv5-based model incorporating Mish activation, DIoU loss, and Squeeze-and-Excitation modules reached a grading accuracy of 93% with throughput of four apples per second on an automatic grading machine [

33]. In addition, a CNN-VGG16-based system classified apple color and deformity with 92.29% accuracy [

31], and recent reviews have reported that deep learning combined with spectral imaging can achieve up to 98.7% mean average precision in apple maturity estimation [

32]. Across both crop types, architectural innovations such as multi-scale feature fusion, Receptive Field Attention Convolution, and advanced loss functions like WIoUv3 have further enhanced detection robustness in field conditions [

18,

19]. Techniques including transfer learning and mini-batch k-means++ clustering have also proven effective in reducing training overhead and improving bounding box precision in low-data regimes [

20]. Meanwhile, data augmentation and semantic segmentation strategies have contributed to better handling of small, occluded, or overlapping targets in dense crop environments [

21,

22]. [

24] demonstrated early use of YOLO for pest detection in greenhouse settings, underscoring the long-term potential of real-time detection frameworks in integrated pest management. Collectively, these developments form a foundation for the design of scalable, edge-deployable detection systems in smart agricultural applications.

Despite recent advancements, several challenges remain. Whereas precision spraying technologies have shown promise in reducing pesticide usage, most current systems still face significant limitations in real-time deployment, particularly in complex orchard environments. Dense tree canopies, variable lighting, and occlusions present serious obstacles for reliable pest detection and precise spraying. Existing YOLO architectures, including YOLOv9, often face challenges with computational complexity, limiting their applicability on resource-constrained industrial robotics platforms such as autonomous orchard spraying robots. To directly address these challenges, we propose YOLOv9-SEDA, featuring depthwise separable convolutions, Efficient Channel Attention (ECA), Swish activation, and Lookahead-AdamW optimization. This combination explicitly addresses real-time performance and reliability requirements, crucial for industrial robotics applications.

This paper proposes YOLOv9-SEDA (referred to as SEDA), an enhanced object detection framework tailored for real-time pesticide application in orchard environments. A systematic literature review [

25] supports the growing use of YOLO-based models in agricultural object detection, particularly in scenarios requiring real-time decision making. The main contributions of this work are as follows:

Model Architecture Enhancement: SEDA integrates depthwise separable convolutions and Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) to improve feature extraction while significantly reducing computational complexity.

Improved Training Stability and Non-Linearity Handling: The Lookahead optimizer combined with AdamW is employed to enhance convergence speed and stability, while the Swish activation function mitigates vanishing gradients and improves non-linear representation.

Edge Device Optimization: The framework is designed for real-time operation on resource-constrained edge devices, enabling practical deployment in field scenarios.

Robust Detection in Complex Environments: SEDA is particularly effective at detecting small and overlapping targets under variable environmental conditions, addressing challenges common in dense orchards.

Sustainable Agricultural Impact: By improving detection precision, the system supports targeted pesticide application, leading to significant reductions in chemical usage and environmental impact.

Comprehensive Validation: Extensive experimental evaluations demonstrate that SEDA outperforms YOLOv9 and other state-of-the-art models in both accuracy and inference speed, validating its effectiveness for intelligent agricultural spraying systems.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Evaluation of Individual Modification Enhancements

Table 4 presents a comparative analysis of various object detection architectures and enhancements, including Depthwise Separable, Efficient Channel Attention, AdamW (Lookahead), Swish Activation, and the proposed SEDA model. Performance is evaluated using Precision (P), Recall (R), mAP@0.5, mAP@0.5:0.95, F1-score, and inference time.

SEDA achieves the highest P (89.5%), R (91.1%), mAP@0.5 (94.2%), mAP@0.5:0.95 (84.6%), and F1-score (90.3%), demonstrating superior accuracy and robustness. Although its inference time (15.3 ms) is slightly higher, it remains suitable for real-time applications.

Depthwise Separable offers faster inference (11.8 ms) with moderate accuracy. Efficient Channel Attention improves feature representation but incurs a higher computational cost (22.1 ms) and reduced mAP. AdamW (Lookahead) and Swish Activation enhance optimization and non-linearity handling, yielding balanced performance but falling short of SEDA in aggregate metrics.

Overall, SEDA outperforms all evaluated models, offering state-of-the-art accuracy while maintaining practical inference efficiency for high-precision detection tasks.

4.2. Comparison with Baseline Models

To evaluate SEDA’s performance, we conducted a comparative analysis against baseline models, including YOLOv9, YOLOv5, YOLOv7, and other state-of-the-art detectors such as ATSS, RetinaNet, and RCNN. As shown in

Table 5, SEDA consistently outperforms all compared models across key metrics, including Precision, Recall, mAP, F1-score, and model efficiency.

SEDA achieved the highest precision (89.5%) and recall (91.1%), outperforming YOLOv9 (84.4%, 86.6%) and YOLOv5 (83.9%, 88.8%). Its mAP reached 94.2% at IoU@0.5 and 84.6% at IoU@0.5:0.95, notably higher than YOLOv9 (91.1%, 76.1%) and YOLOv5 (91.9%, 71.5%). SEDA also achieved the highest F1-score (90.3%), indicating well-balanced precision and recall.

In terms of model size, SEDA has 39.6M parameters and an 80.7MB weight file, which is more compact than YOLOv9 (50.7M, 102.7MB). Although its inference time (15.3 ms) is slower than YOLOv5 (11.3 ms) and YOLOv9 (9.4 ms), the trade-off is justified by superior accuracy and robustness.

These results confirm SEDA’s effectiveness in real-time object detection, demonstrating improved accuracy, reduced model complexity, and strong generalization performance across diverse detection tasks.

4.3. Performance Analysis of SEDA: Precision-Recall Curve and Detection Accuracy

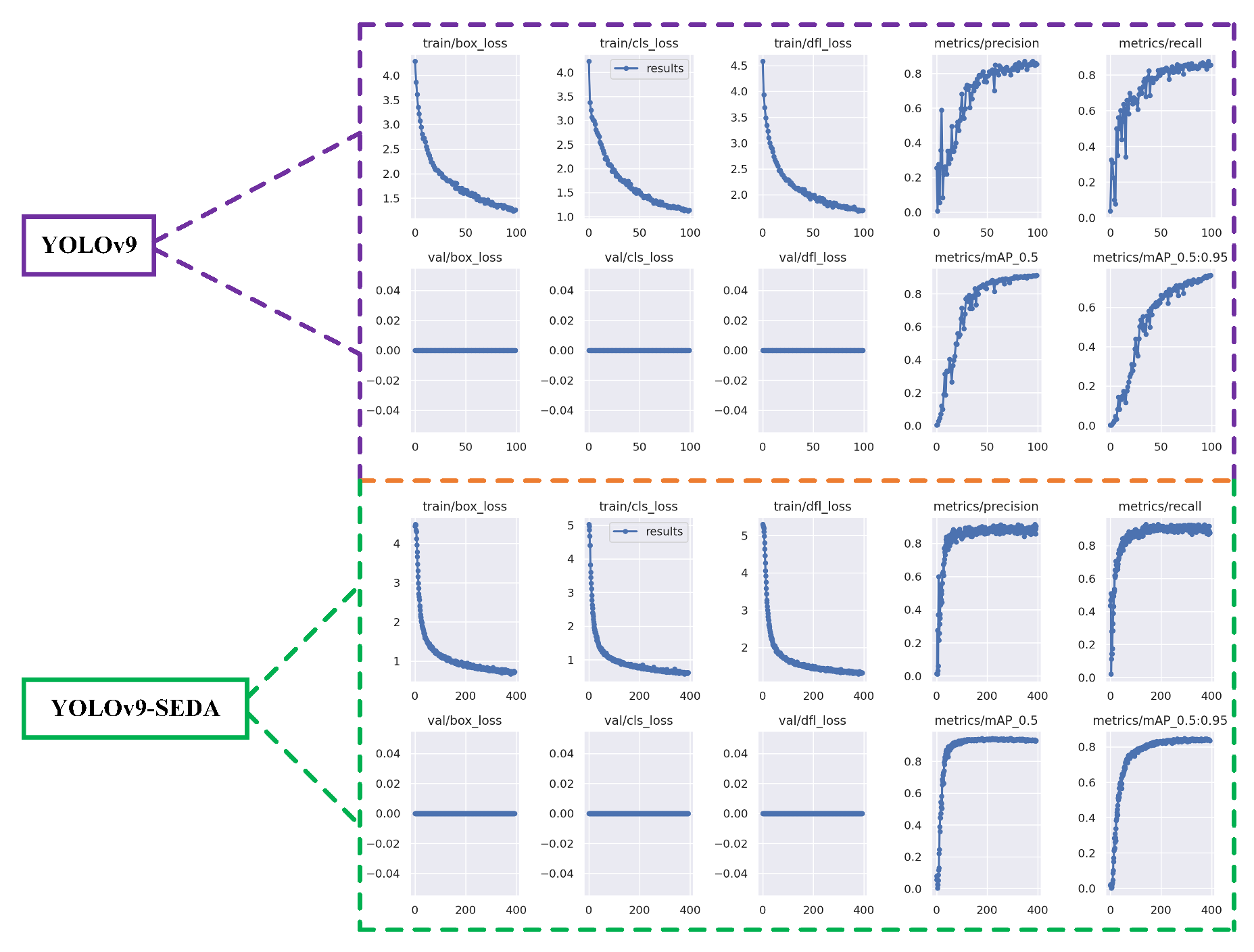

To evaluate the performance of YOLOv9 and its improved variant SEDA, we conducted a comparative analysis focusing on precision, recall, and mAP.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 illustrate training trends and model performance.

Both models exhibit steady convergence over 400 epochs, with SEDA showing consistently lower training losses, including box, classification, and DFL loss. The reduced box loss indicates improved bounding box regression, while lower classification and DFL losses reflect enhanced object recognition and distribution learning, respectively. These results highlight the effectiveness of SEDA’s architectural modifications in reducing training errors.

In terms of detection capability, SEDA achieves higher precision and recall throughout training, reflecting improved performance in minimizing both false positives and false negatives. Additionally, SEDA outperforms YOLOv9 in mAP@0.5 and mAP@0.5:0.95, demonstrating superior localization accuracy across IoU thresholds. The performance gap is particularly evident at the stricter mAP@0.5:0.95 level, indicating SEDA’s robustness in high-accuracy detection scenarios.

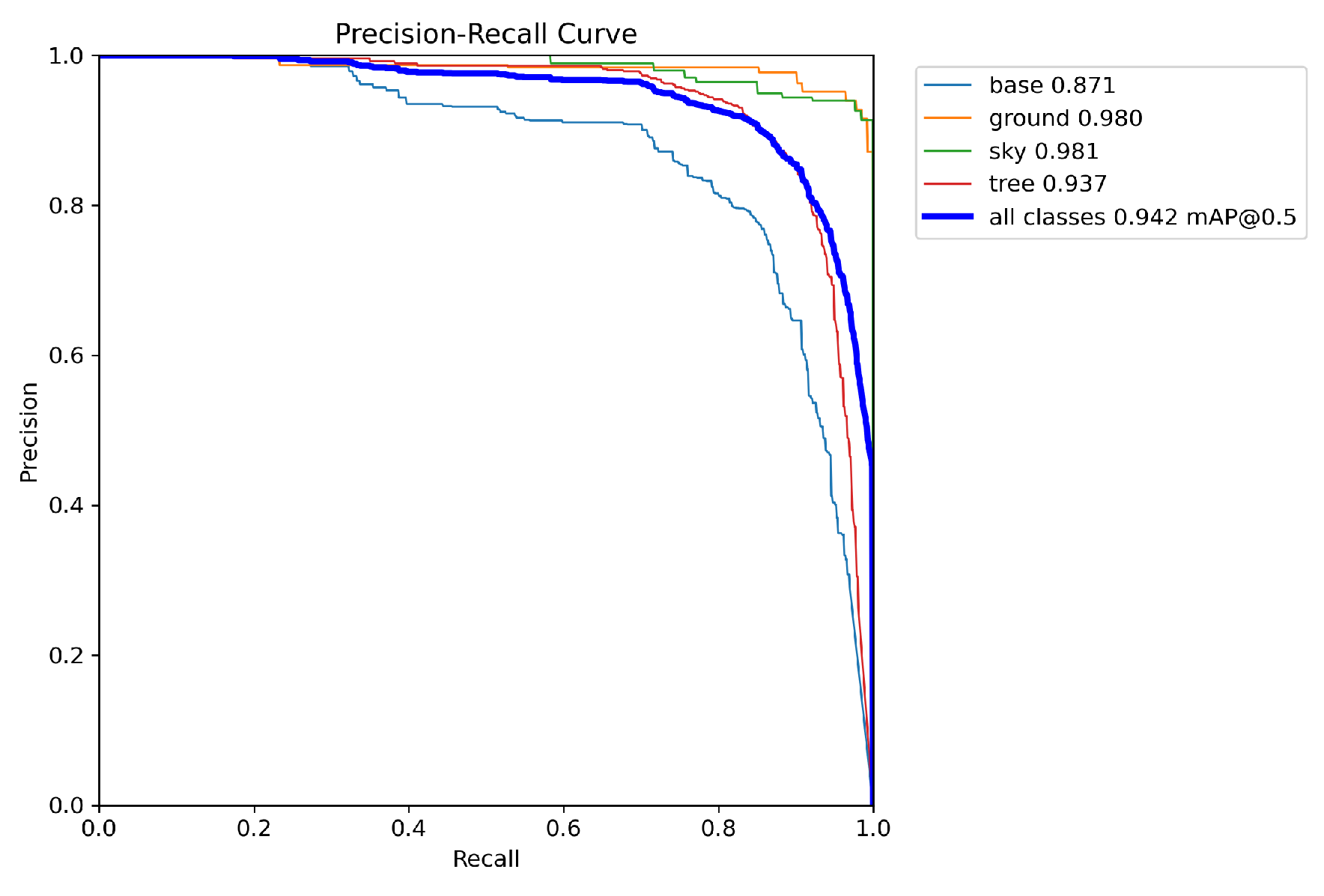

Figure 11, depicts the Precision-Recall (PR) curve for SEDA, providing a visual evaluation of its detection performance across different confidence thresholds. The curves represent the precision-recall tradeoff for individual classes such as "tree," "base," "ground," and "sky," as well as the overall mAP@0.5 for all classes. SEDA achieves consistently high precision and recall values across all classes, with particularly strong performance for "sky" (0.981) and "ground" (0.980). The overall mAP@0.5 of 0.942 highlights the model’s robustness and reliability in detecting objects in diverse and complex scenarios.

The "tree" class achieves a slightly lower precision-recall performance (0.937) compared to other classes, which might be attributed to the higher variability in object appearance and occlusion within the dataset. However, the PR curve for the "tree" class still demonstrates high precision at varying recall levels, indicating the model’s ability to maintain accurate detections even as it identifies more objects. This analysis underscores the effectiveness of SEDA in maintaining high performance across multiple object categories.

4.4. Object Detection Image Analysis: Evaluation of YOLOv9 and SEDA Results

Figure 12, compares object detection results from the dataset images, YOLOv9, and the improved SEDA algorithm. The top row presents raw dataset images, showcasing potted trees in a natural environment. The middle row shows detection results using YOLOv9, with bounding boxes for detected objects such as "tree," "base," and "ground," along with their associated confidence scores. However, YOLOv9 exhibits certain limitations. As can be seen, in the first and second images of the second row, red dotted triangles indicate areas where YOLOv9 places bounding boxes inconsistently, highlighting inaccurate detections.

The third row depicts the results of the proposed SEDA algorithm, showing significant improvements in detection accuracy and consistency. SEDA demonstrates enhanced precision, with well-defined and correctly localized bounding boxes around the objects. Confidence scores for the detected objects are generally higher than in YOLOv9, especially for the base and ground objects. The third-row images further demonstrate how SEDA addresses YOLOv9’s shortcomings, providing more robust and reliable detection outcomes.

This comparison underscores SEDA’s effectiveness in enhancing detection performance in complex environments by improving detection precision and confidence. The visual distinction between the model outputs highlights the advancements made through structural enhancements.

4.5. Industrial Deployment and Real-World Testing

In this study, we present a comparison between the SEDA method, and the Uncontrolled method. The key advantage of the SEDA method is its ability to spray only where trees are detected, ensuring that the spray is applied efficiently, targeting areas where it is most needed. As a result, it does not excessively spray non-tree areas, reducing waste. Additionally, SEDA adjusts the spray volume based on tree density, spraying more in areas with higher tree concentration and less in areas with fewer trees. This targeted spraying not only increases the overall efficiency of the spraying process but also ensures that resources are utilized more effectively. In contrast, the Uncontrolled method, while providing more uniform coverage, sprays indiscriminately across all regions, leading to excessive spray in non-tree areas and potentially wasting resources.

Table 6 presents a detailed comparison of regional spray coverage between the proposed SEDA framework and the uncontrolled spraying method. The table reports spray coverage percentages across six predefined spatial zones (top-left, top-right, middle-left, middle-right, bottom-left, and bottom-right), representing different regions of the canopy or field. As shown, the SEDA method consistently achieves lower coverage in most regions compared to the uncontrolled approach. Notably, SEDA reduces coverage in the bottom-right region from 47.84% to 29.50%, indicating more precise targeting and minimal overspray in peripheral areas. Similar reductions are observed in the top-left (27.73% vs. 39.74%) and middle-left (19.75% vs. 34.98%) regions, further demonstrating SEDA’s ability to focus spraying only on relevant areas. Although the bottom-left and middle-right zones show comparable coverage, the overall average spray coverage is reduced from 38.42% in the uncontrolled method to 30.47% with SEDA. This 20.74% reduction in average coverage highlights the effectiveness of the proposed system in minimizing chemical usage, thereby enhancing operational efficiency and environmental sustainability in precision agriculture.

This shows that the SEDA method has reduced spray coverage by approximately 20.75% compared to the Uncontrolled method. This reduction in spray coverage highlights the efficiency of the SEDA method in minimizing waste, ensuring that only the necessary areas are sprayed. This experiment demonstrates how SEDA’s intelligent spraying not only optimizes coverage but also leads to a significant reduction in resource consumption, achieving a more sustainable and cost-effective spraying solution.

Table 7 presents a quantitative comparison of spray wastage in selected non-target spots using the proposed SEDA framework and the uncontrolled spraying method. The evaluated spots represent areas where pesticide application is not required—such as open ground, sky, or tree-free regions—thus, lower spray coverage indicates more effective waste reduction.

As shown, the uncontrolled method exhibits substantial spray deposition in these non-target zones, with coverage values of 29.92%, 35.74%, and 40.74% across Spot-1 to Spot-3, yielding an average wastage of 35.47%. In contrast, SEDA demonstrates significantly lower spray coverage of only 0.81%, 0.51%, and 0.89%, respectively, resulting in an average wastage of just 0.74%.

This represents a reduction in non-target spray deposition of over 97.9%, confirming SEDA’s effectiveness in minimizing chemical waste. The results validate that SEDA achieves high-precision spraying by activating the nozzle only when target trees are detected, thereby improving environmental safety and resource efficiency in orchard management.

In addition to detection accuracy and spray precision, practical deployment requires high inference speed, compact model size, and robustness in unstructured environments.

Table 8 presents a comparative evaluation of YOLOv9-SEDA against baseline models, including YOLOv5, YOLOv7, YOLOv9, ATSS, RetinaNet, and Double Head, when deployed on the Jetson Xavier NX platform. The comparison highlights differences in real-time inference speed, model size, accuracy, and robustness, providing insights into their practical suitability for deployment in orchard environments.

As illustrated in

Table 8, YOLOv9-SEDA significantly outperforms state-of-the-art industrial baselines in detection accuracy while maintaining competitive inference speed. Despite having a slightly lower FPS than YOLOv5 and YOLOv9, it offers enhanced robustness and a compact model size, making it well-suited for real-world deployment in agricultural environments. These findings confirm the potential of YOLOv9-SEDA as a practical and scalable solution for intelligent spraying systems, delivering high precision and reliability while satisfying the real-time constraints of embedded platforms.

5. Conclusion

This study proposed YOLOv9-SEDA, an enhanced and computationally efficient object detection framework tailored for real-time, targeted pesticide spraying in orchard environments. The model integrates depthwise separable convolutions to reduce computational complexity, ECA to improve feature representation, the Swish activation function to facilitate smoother gradient propagation, and a Lookahead-AdamW optimization strategy to accelerate and stabilize convergence. Comprehensive experiments conducted on high-resolution orchard datasets demonstrated the superior performance of YOLOv9-SEDA compared to existing state-of-the-art models, achieving a precision of 89.5%, recall of 91.1%, mAP@0.5 of 94.2%, and mAP@0.5:0.95 of 84.6%, with an inference latency of 15.3 ms, thereby validating its suitability for edge deployment.

The practical utility of the proposed method was further validated through deployment on an autonomous robotic platform operating in real-world orchard conditions. The system achieved a 20.75% reduction in overall spray coverage and a 97.91% reduction in non-target area spraying, underscoring its potential to enhance operational efficiency, minimize agrochemical usage, and promote sustainable agricultural practices.

From an industrial informatics perspective, the lightweight nature and high inference speed of YOLOv9-SEDA make it well-suited for integration into broader Industry 4.0 and Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) frameworks. Its capabilities extend beyond agriculture, offering applicability in various domains such as automated quality inspection, logistics, and industrial surveillance.

Future research will focus on expanding the model’s generalization capability across diverse agricultural environments, incorporating multi-modal sensory inputs, and extending the framework to include semantic segmentation and disease classification modules. Furthermore, integration with automated aerial platforms such as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and industrial mobile robots will be explored to facilitate scalable deployment across large-scale agricultural and industrial sites. These efforts aim to advance the development of robust, autonomous vision systems for intelligent environmental interaction in next-generation automation ecosystems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.S., Z.K.; methodology, Z.K.; software, Z.Y. and Z.K.; validation, Y.S., Z.K., H.L.; formal analysis, Y.S., Z.K., and H.L.; investigation, Z.Y. and Z.K.; resources, Z.K. and H.L.; data curation, Z.K.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.K.; writing—review and editing, Z.K., and H.L.; visualization, Z.K.; supervision, Y.S.; project administration, Y.S., Z.K., and H.L.; funding acquisition, H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

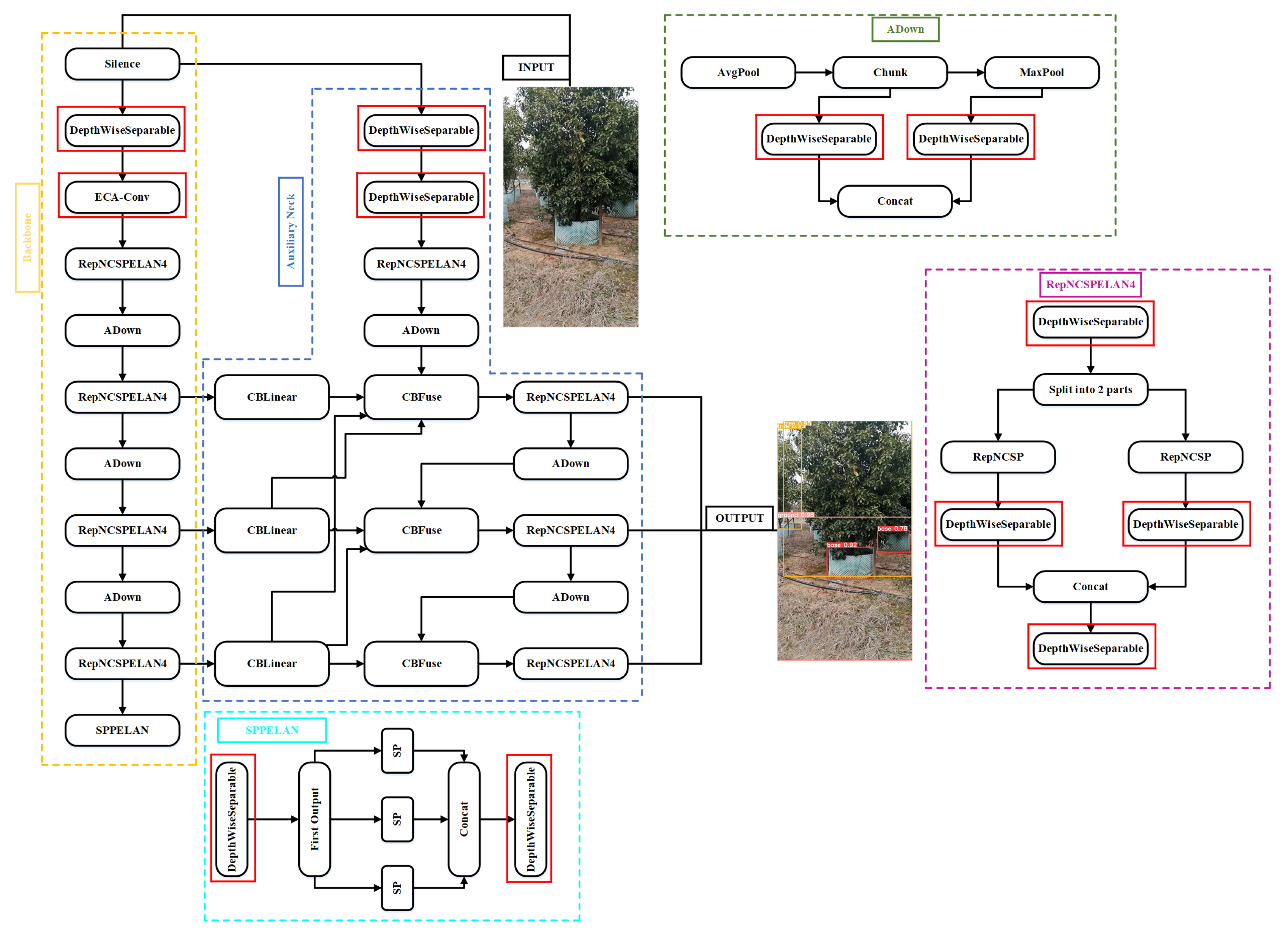

Figure 1.

YOLOv9-SEDA: A novel architecture for precision object detection.

Figure 1.

YOLOv9-SEDA: A novel architecture for precision object detection.

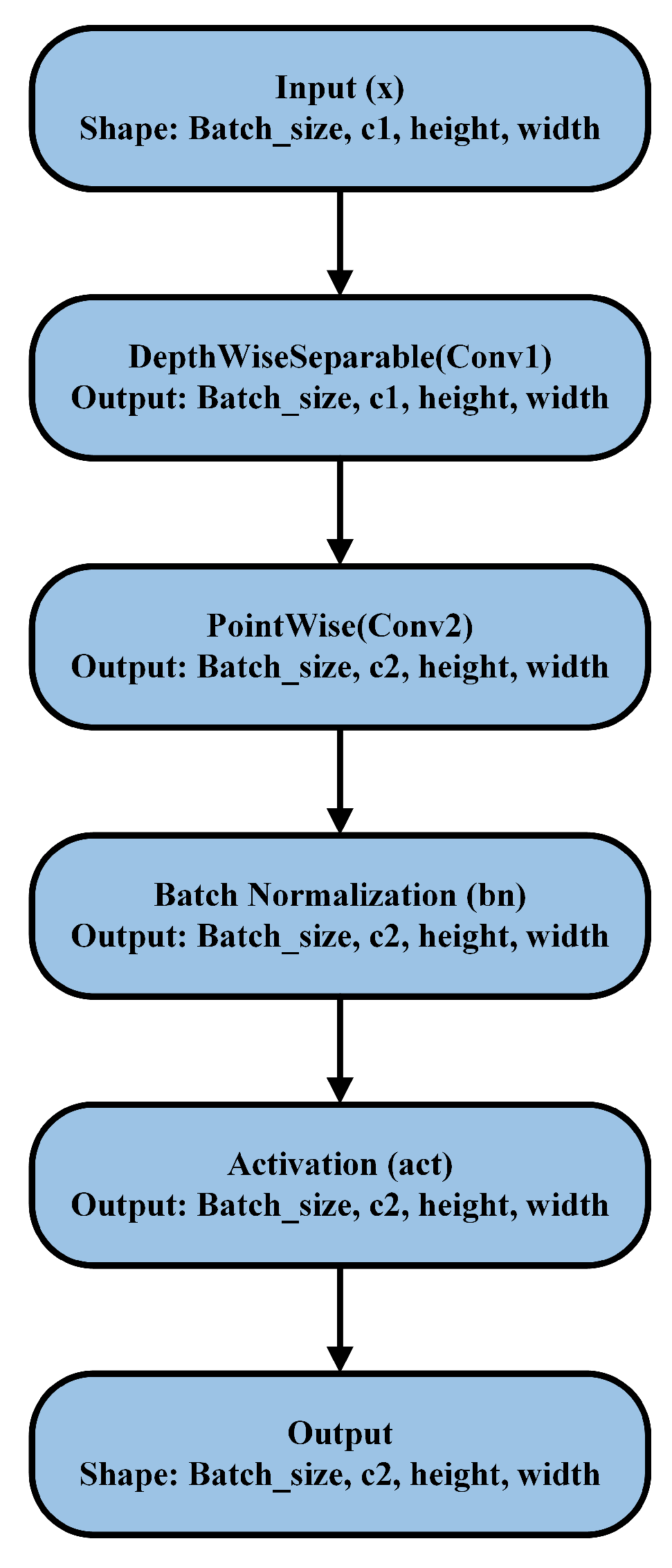

Figure 2.

Depthwise separable convolution module with batch normalization and activation for enhanced feature extraction.

Figure 2.

Depthwise separable convolution module with batch normalization and activation for enhanced feature extraction.

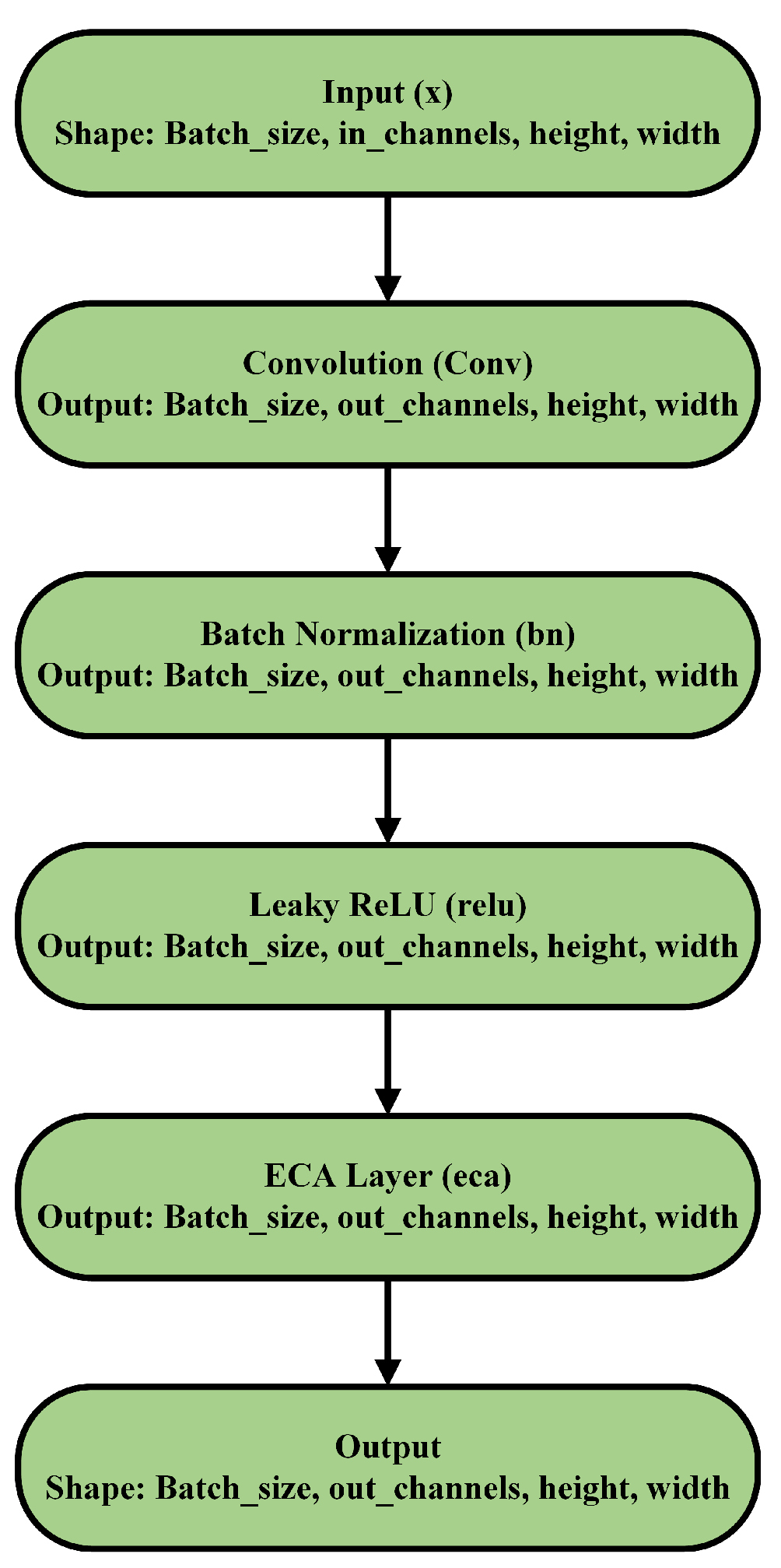

Figure 3.

Convolutional block with ECA attention for enhanced feature representation.

Figure 3.

Convolutional block with ECA attention for enhanced feature representation.

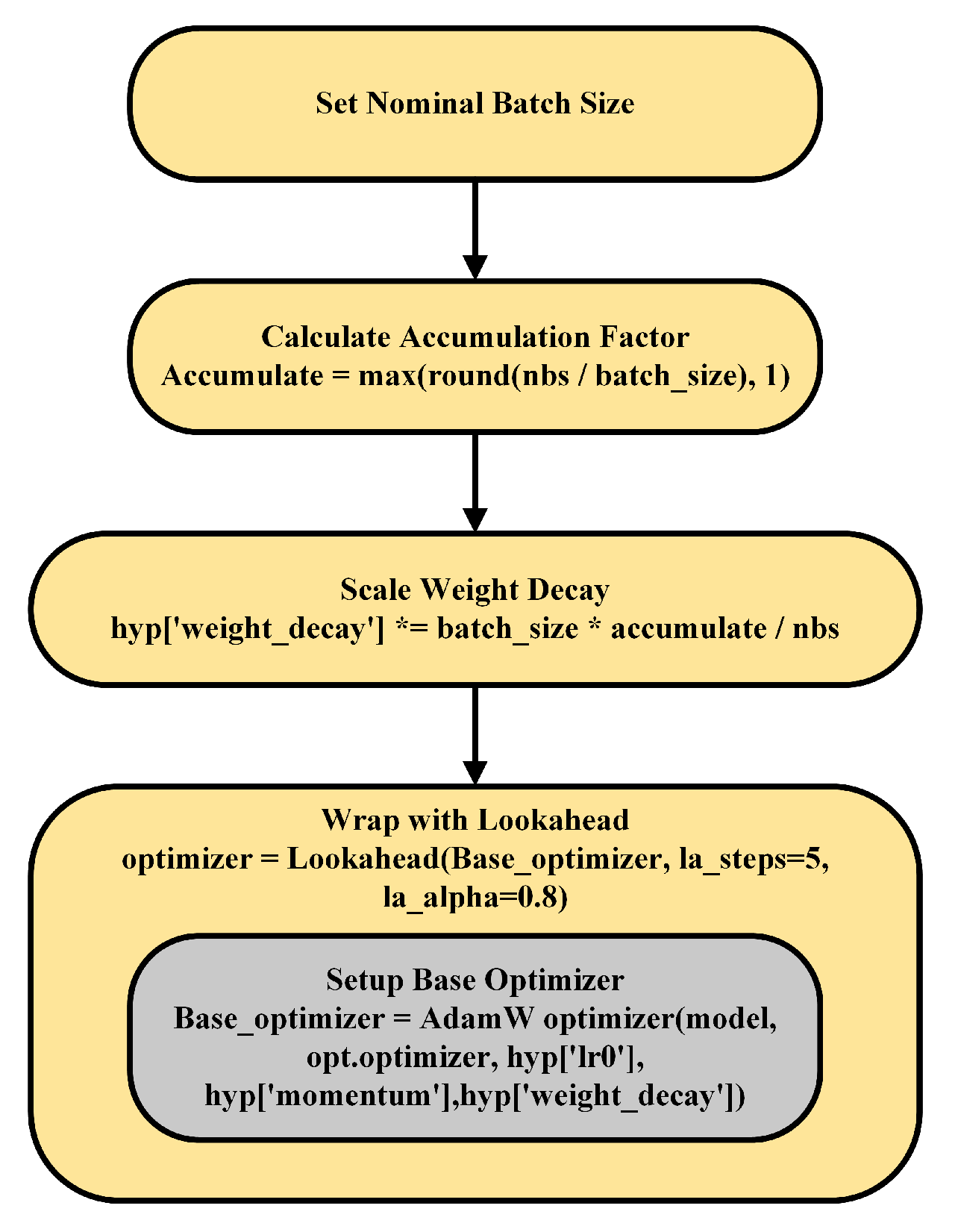

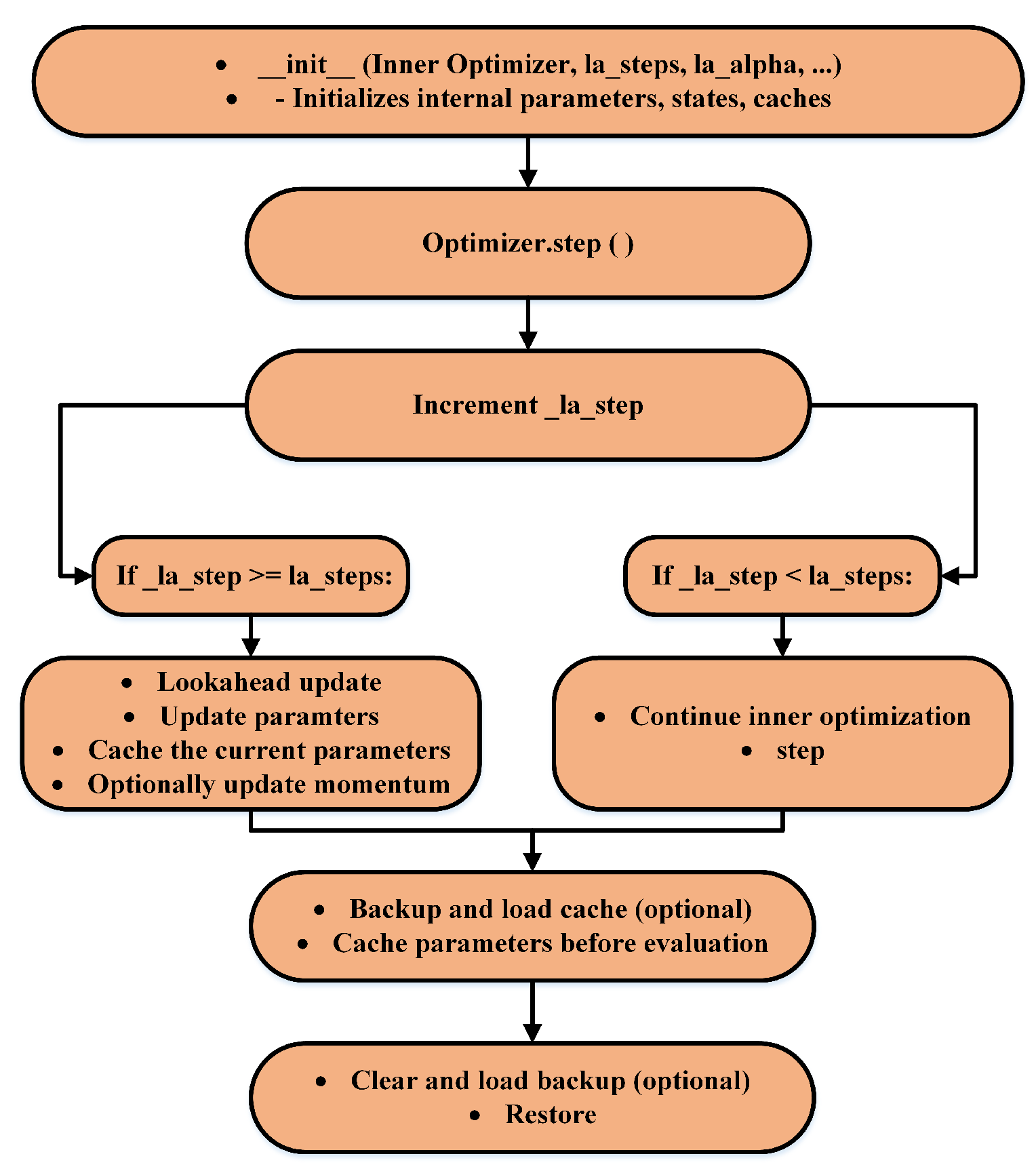

Figure 4.

Lookahead-enhanced AdamW optimization flow for improved model training stability.

Figure 4.

Lookahead-enhanced AdamW optimization flow for improved model training stability.

Figure 5.

Lookahead optimizer flowchart: progressive parameter update mechanism for enhanced gradient descent stability.

Figure 5.

Lookahead optimizer flowchart: progressive parameter update mechanism for enhanced gradient descent stability.

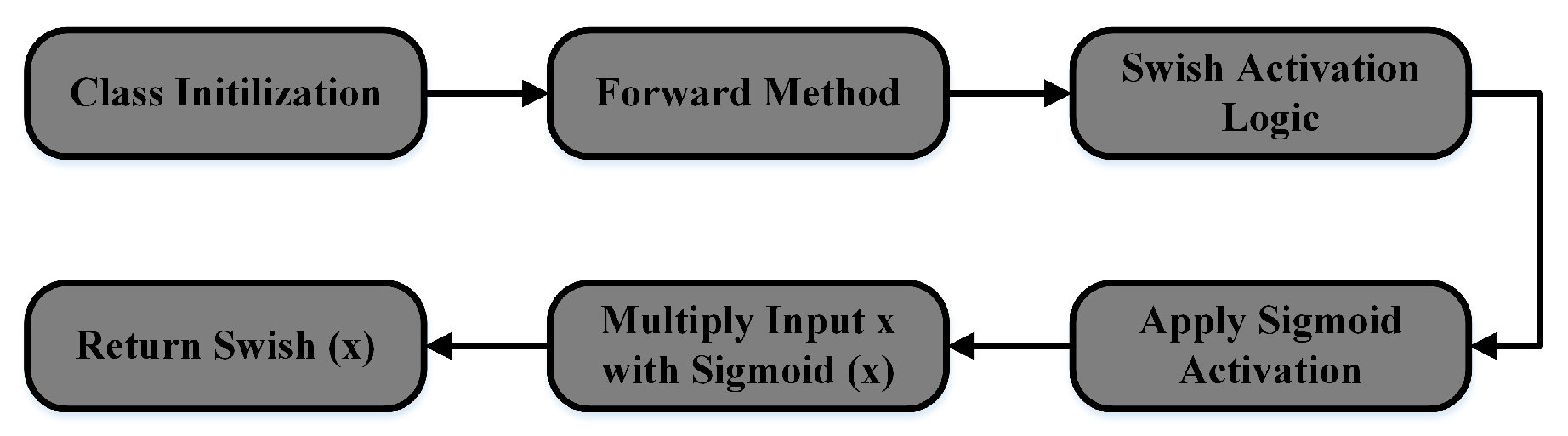

Figure 6.

Swish activation function flowchart: forward pass implementation using sigmoid and element-wise multiplication.

Figure 6.

Swish activation function flowchart: forward pass implementation using sigmoid and element-wise multiplication.

Figure 7.

Sample images from the orchard tree dataset.

Figure 7.

Sample images from the orchard tree dataset.

Figure 8.

Robot and spraying System: components for efficient and targeted spraying

Figure 8.

Robot and spraying System: components for efficient and targeted spraying

Figure 9.

Structured light depth-sensing camera for object detection and spatial awareness

Figure 9.

Structured light depth-sensing camera for object detection and spatial awareness

Figure 10.

Comparison of training and validation metrics between YOLOv9 and SEDA for real-time orchard detection.

Figure 10.

Comparison of training and validation metrics between YOLOv9 and SEDA for real-time orchard detection.

Figure 11.

Precision-Recall curve for multi-class object detection with mAP@0.5.

Figure 11.

Precision-Recall curve for multi-class object detection with mAP@0.5.

Figure 12.

Performance metrics comparison of object detection algorithms.

Figure 12.

Performance metrics comparison of object detection algorithms.

Table 1.

Summary of YOLOv9-SEDA architectural enhancements and their industrial benefits.

Table 1.

Summary of YOLOv9-SEDA architectural enhancements and their industrial benefits.

| Component |

YOLOv9 Limitation Addressed |

Benefit in Industrial Deployment |

| Depthwise Separable Convolutions |

High computational load in standard convolutions |

Reduces model size and computation, enabling real-time inference on embedded devices |

| Efficient Channel Attention (ECA) |

Weak channel-wise feature representation |

Enhances attention to key features without significant overhead |

| Swish Activation |

Poor gradient flow with ReLU/Leaky ReLU |

Improves gradient propagation and learning of complex patterns |

| AdamW + Lookahead Optimizer |

Unstable convergence in training |

Boosts optimization stability and generalization, critical for field variability |

Table 2.

Dataset attributes and preprocessing details.

Table 2.

Dataset attributes and preprocessing details.

| Attribute |

Details |

| Total images |

1265 images |

| Preprocessing applied |

Auto orientation |

| Augmentations applied |

Rotation: between and

|

| |

Grayscale: applied to 15% of images |

| |

Brightness: between and

|

| |

Noise: up to 6% of pixels |

Table 3.

Training environment setup.

Table 3.

Training environment setup.

| Category |

Configuration |

| CPU |

Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6226R CPU @ 2.90 GHz |

| GPU |

NVIDIA RTX 3090 |

| System environment |

Ubuntu 20.04.5 LTS |

| Framework |

PyTorch 1.12 |

| Programming language |

Python 3.8 |

Table 4.

Performance comparison of YOLOv9-SEDA components and the overall network.

Table 4.

Performance comparison of YOLOv9-SEDA components and the overall network.

| Network |

P (%) |

R (%) |

mAP@0.5 (%) |

mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) |

Inference Time (ms) |

F1 Score |

| Depthwise Separable |

87.5 |

90.1 |

93.2 |

81.4 |

11.8 |

88.9 |

| Efficient Channel Attention |

86.4 |

82.4 |

90.0 |

74.5 |

22.1 |

85.3 |

| AdamW (Lookahead) |

86.8 |

84.1 |

90.2 |

75.8 |

11.9 |

85.6 |

| Swish Activation |

85.1 |

86.6 |

90.6 |

75.7 |

12.5 |

85.5 |

| YOLOv9-SEDA (Ours) |

89.5 |

91.1 |

94.2 |

84.6 |

15.3 |

90.3 |

Table 5.

Performance comparison of object detection algorithms for real-time orchard detection.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of object detection algorithms for real-time orchard detection.

| Algorithm |

P (%) |

R (%) |

mAP@0.5 (%) |

mAP@0.5:0.95 (%) |

Inference Time (ms) |

F1 Score |

| YOLOv5 |

83.9 |

88.8 |

91.9 |

71.5 |

11.3 |

86.3 |

| YOLOv7 |

83.4 |

83.0 |

88.8 |

61.9 |

11.3 |

83.2 |

| YOLOv9 |

84.4 |

86.6 |

91.1 |

76.1 |

9.4 |

85.5 |

| ATSS |

69.9 |

71.3 |

70.0 |

65.1 |

– |

70.6 |

| RetinaNet |

56.9 |

69.6 |

68.2 |

58.5 |

– |

62.7 |

| Double Head |

65.4 |

72.5 |

69.5 |

63.8 |

– |

68.7 |

| YOLOv9-SEDA (Ours) |

89.5 |

91.1 |

94.2 |

84.6 |

15.3 |

90.3 |

Table 6.

Regional spray coverage comparison between SEDA and the uncontrolled method.

Table 6.

Regional spray coverage comparison between SEDA and the uncontrolled method.

| Method |

Top-Left |

Top-Right |

Middle-Left |

Middle-Right |

Bottom-Left |

Bottom-Right |

Average |

| SEDA |

27.73% |

31.86% |

19.75% |

35.89% |

38.12% |

29.50% |

30.47% |

| Uncontrolled |

39.74% |

39.58% |

34.98% |

34.31% |

34.07% |

47.84% |

38.42% |

Table 7.

Comparison of spray wastage in non-target spots: SEDA vs. uncontrolled method.

Table 7.

Comparison of spray wastage in non-target spots: SEDA vs. uncontrolled method.

| Method |

Spot-1 |

Spot-2 |

Spot-3 |

Average |

| SEDA |

0.81% |

0.51% |

0.89% |

0.74% |

| Uncontrolled |

29.92% |

35.74% |

40.74% |

35.47% |

Table 8.

Deployment performance comparison on Jetson Xavier NX.

Table 8.

Deployment performance comparison on Jetson Xavier NX.

| Method |

mAP (%) |

FPS |

Model size (MB) |

Robustness |

| YOLOv5 |

71.5 |

88.5 |

42.1 |

Medium |

| YOLOv7 |

61.9 |

88.5 |

74.8 |

Medium |

| YOLOv9 |

76.1 |

106.3 |

102.7 |

High |

| ATSS |

65.1 |

– |

408.9 |

Medium |

| RetinaNet |

58.5 |

– |

378.4 |

Low |

| Double Head |

63.8 |

– |

409.4 |

Low |

| YOLOv9-SEDA (Ours) |

84.6 |

65.3 |

80.7 |

High |