1. Introduction

The increasing demand for electric vehicles (EVs) and energy storage systems has led to a surge in the production and use of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), particularly lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries [1,2]. LFP batteries have gained widespread adoption in large electric buses and cars due to their safety, long cycle life, and cost-effectiveness [3]. However, this growth will result in a significant increase in spent LIBs, with estimates suggesting that up to 340,000 tons of spent LFPs from EVs will be available for recycling annually by 2040 [1].

The recycling of spent LFP batteries is crucial from both environmental and resource recovery perspectives[4]. These batteries contain valuable metals such as lithium and phosphorous, as well as harmful materials like organic electrolytes and binders like Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) that pose serious threats to ecosystems and human health if improperly disposed of [3,5,6].

Current recycling methods for LFP batteries can be broadly categorized into physical and chemical processes. Physical methods, such as mechanical separation, are often used as pretreatment steps to separate electrode materials from other battery components [7,8,9]. Chemical methods include pyrometallurgical and hydrometallurgical processes, each with its own advantages and limitations[10].

Pyrometallurgical processes involve high-temperature treatment to recover metals, but they often result in the loss of valuable materials like graphite and lithium, leading to significant carbon emissions [2,11,12]. Hydrometallurgical processes, on the other hand, use acid or alkaline leaching to dissolve cathode and anode materials, followed by purification steps [13,14,15]. While more selective, these processes can be chemically intensive and may face challenges in separating residues from leach solutions [7,16].

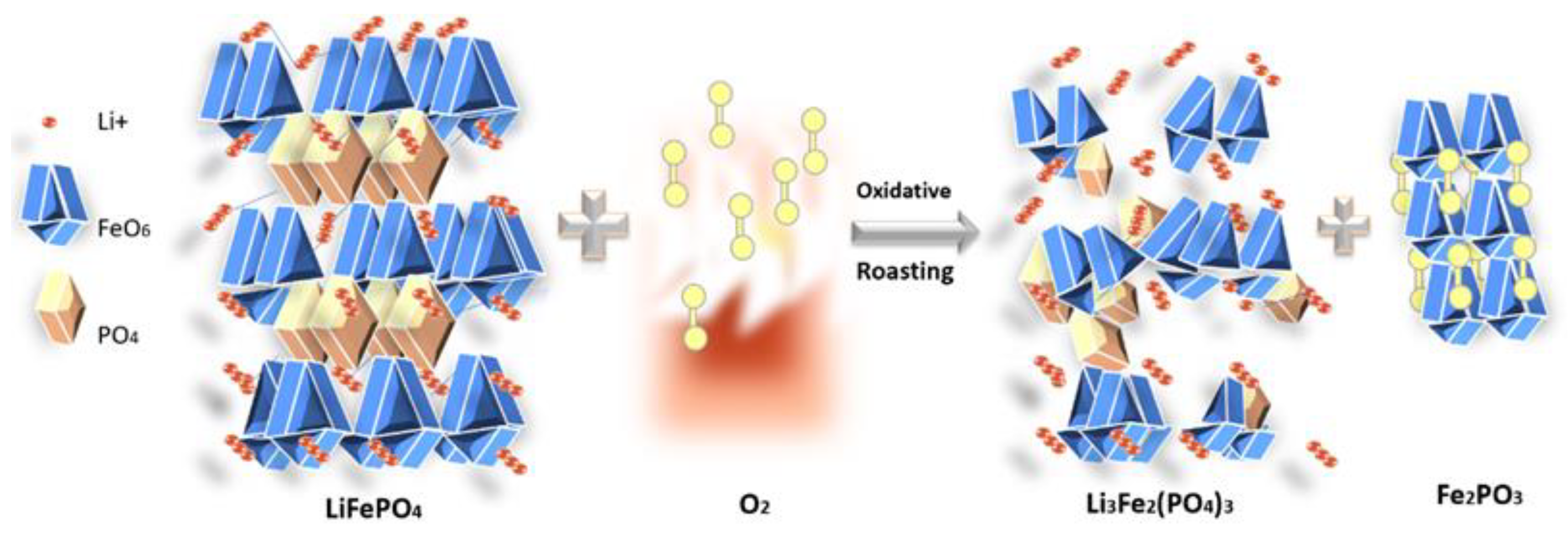

Recent research [17,18,19] has focused on improving the efficiency and sustainability of LFP battery recycling. Thermal pretreatment, or roasting, has emerged as a promising approach to enhance the recovery of valuable metals. Roasting can remove organic binders and modify the chemical structure of cathode materials, potentially improving subsequent leaching or separation processes. However, the effects of thermal treatment on industrially shredded LFP blackmass (BM) are not yet fully understood. Factors such as roasting temperature, duration, and atmosphere can significantly impact the physical and chemical properties of the LFP blackmass [12,20]. Moreover, the optimal conditions for thermal pretreatment may vary depending on the subsequent recovery process employed. Studies indicate oxidative pre-treatment of LFP Blackmass at 650°C aim to enhance lithium leaching efficiency and selectivity in a subsequent low pH water leaching process, due to the decomposition of LFP and the formation of water-soluble lithium compounds, while simultaneously reducing the dissolution of impurities like aluminum, copper and fluorides from binder removal [12,21]. Another study [22] submitted LFP cathode material to TGA and DSC analysis under air flow and reported a weight loss of 6.68% up to 600°C. The exothermic peaks (DSC analysis) corresponded to binder and carbon decomposition at 475°C and 579°C respectively. A color change from dark to reddish brown was also observed due to the oxidation of Fe (II) to Fe (III), which is pointed as the formation of Fe2O3 and Li3Fe2(PO4)3, confirmed by XRD standard spectra and XPS analysis. This mixture was then subjected to 2.5 mol/L H2SO4 leaching for 2h, 60°C, and 100 g/L resulting in a leaching efficiency of 97% and 98% for Li and Fe respectively, therefore not selective[23]. The roasted LFP virgin cathode powder in air flow for 1h at 550°C formed Fe2O3 and Li3Fe2(PO4)3, in which a further leaching with H2SO4 (0.5 M) at 60°C for 2h and 80 g/L has yielded more than 97% of Li recovery. This study [7] indicated that the Fe is highly leached because of the air roasting.

To achieve selective leaching, the understanding the Pourbaix diagram is also demonstrated by Jing et al (2019) [7] revealing that E-pH diagrams can effectively guide the selective extraction of lithium from spent LiFePO₄. By optimizing conditions, such as high temperature, neutral pH, low redox potential, and the use of H₂O₂ as an oxidant, it was achieved up to 95.4% Li recovery while minimizing Fe dissolution. This method eliminates the need for large amounts of acids or bases, offering a commercially promising and environmentally friendly approach for lithium recovery.

Therefore, the metallurgical approach of combining thermal pretreatment to better condition impurities and remove binder, electrolyte which contain F and separators from LFP BM followed by selective hydrometallurgical leaching has shown its way forward for both effective and highly selective against FePO4 in spent LFP systems.

The objectives of this study are: (1) to evaluate the impact of roasting as pre-treatment on lithium leaching efficiency and selectivity; (2) to characterize the changes in the composition and morphology of the black mass during roasting; and (3) to compare conventional acid-based leaching with mild-acid based leaching to assess the greener route. By examining these factors, we seek to develop a more efficient and environmentally friendly method for recycling spent LFP batteries, contributing to the circular economy of battery materials and addressing the growing challenge of battery waste management [24,25,26].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Characterization

The input material was Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) blackmass generated from an industrially inert shredder, in which particles greater than 1 mm were separated by sieving. All characterizations, before and after each process, consisted of:

Chemical composition - determined by ICP-OES (Spectro CIROS Vision, Spectro Analytical Instruments GmbH, Kleve, Germany) after digestion in aqua regia;

Carbon content – determined by combustion method for carbon analysis (ELTRA CS 2000, ELTRA GmbH, Haan, Germany);

Fluorine content – determined by Ion Chromatography (811 Compact IC pro, Deutsche Metrohm GmbH & Co. KG, Filderstadt, Germany);

Phases/compounds - determined by X-Ray Diffractometry (Rigaku SmartLab 9kW, Bangkok, Thailand) with measurements each 0.5° with radiation Cu Kα;

Morphology of particles – determined by Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (JEOL model JSM-6610 LV, Bangkok, Thailand).

2.2. Roasting in Air Atmosphere

The LFP blackmass underwent an air roasting process in a rotary kiln (Carbolite Gero, TS01 11/400, Neuhausen, Germany), where the flow rate was maintained at a constant 5 L/min. A sample of 200 g of LFP blackmass was placed in a quartz tube and heated to 650°C at a rate of 250°C/h, and this temperature was sustained for one hour. Following the roasting process, the material was cooled to room temperature within the furnace before being removed and weighed.

2.3. Leaching Procedure

The leaching trials were conducted according to a general full factorial design, utilizing the analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistical method to evaluate the leaching efficiencies of the metals lithium (Li), iron (Fe), phosphorus (P), aluminum (Al), and copper (Cu).

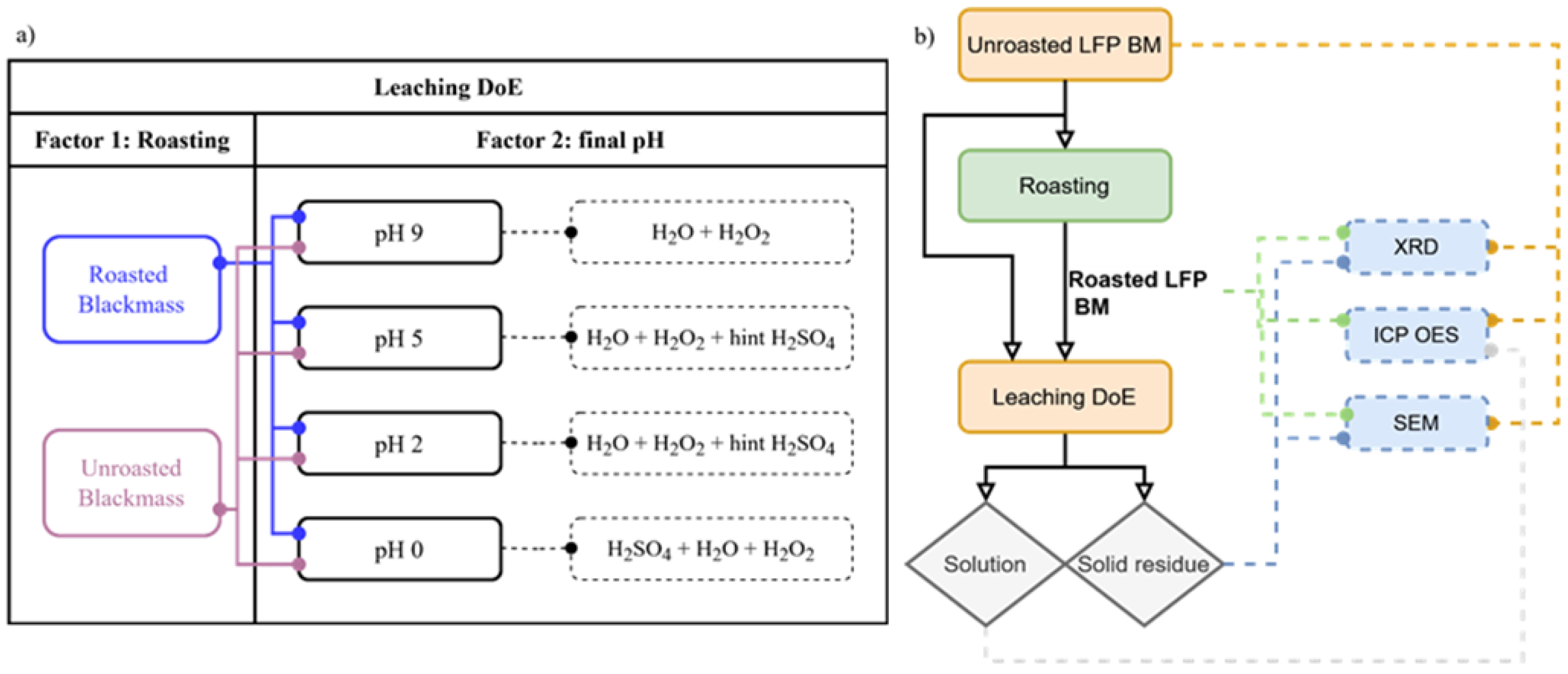

Figure 1 (a) summarizes the experimental design, which considered two factors: roasting and final pH, obtained according to the leaching agent/conditions of each trial. The complete design of experiments resulted in 8 runs, each duplicated, yielding a total of 16 experiments. Both roasted and unroasted black mass with a particle size of less than 90 µm were leached in a 250 mL glass reactor equipped with a sealed three-neck lid. Agitation was performed using a mechanical stirrer, maintained at a constant speed of 350 rpm throughout all trials. The solid/liquid ratio was set at 40 g/L, with temperature maintained at 20°C and a duration of 90 minutes. The concentration of sulfuric acid (H2SO4) was kept constant at 2 mol/L, representing 10-times the stoichiometric excess, while hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) was maintained at a concentration of 2.7 mol/L. All these factors were selected based on prior assessments. The pH was monitored using a Mettler Toledo device during the leaching processes and served as the basis for decision-making when necessary. Following the leaching process, the solid residue and solution were separated by filtration and washed once using 200 mL of distilled water. Washing after leaching removes any residual soluble impurities, ensuring the purity of the filtrate and precipitate. Both the filtrate and residue were collected for chemical analysis. The latter was dried overnight at 95°C.

Figure 1 (b) shows a sketch of the process flow and analysis of this study.

The lithium leaching efficiency was calculated using the following equation;

Where:

Amount of Li in Blackmass= Li concentration in leach solution (mg/L) * Volume of leach solution (L)

Initial amount of Li dissolved in Leach Solution = Li content in black mass (wt.%) * Mass of black mass used in leaching (g)

3. Results

3.1. LFP Blackmass Characterization and Roasting Effect

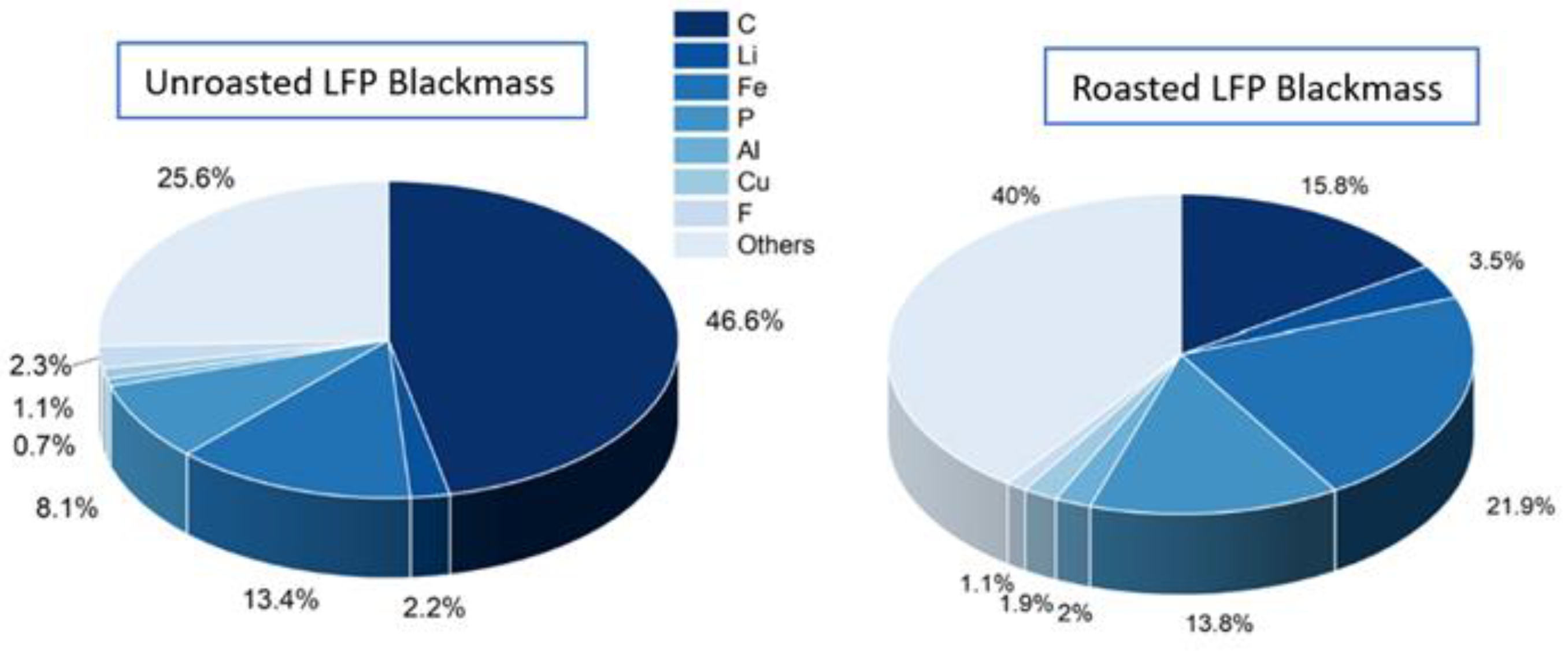

The chemical composition of unroasted and roasted blackmass is shown in

Figure 2. In comparison with the different literature [24,27], the composition is similar. The “others” label in both roasted and unroasted LFP blackmass comprehends oxygen content and unknown metals/oxides. Based on the Li-, Fe-, and Al- content, it is possible to estimate theoretically the oxygen content. Following the assumption that all Li in the sample is in the form of LiFePO4, then the O-content is 20.1% for unroasted blackmass, which leaves 5.51% of unidentified compounds. For the roasted blackmass, the oxygen is divided into three molecules, Li3Fe2(PO4)3, Fe2O3, and AlPO4 according to the literature and the XRD from this study (

Figure 3). This means that, theoretically, the O-content is 37.9%, which leaves ~2% of unidentified compounds.

The elemental composition analysis of the unroasted LFP/Graphite blackmass reveals significant carbon content (46.6%) alongside key battery components including iron (13.4%), phosphorus (8.1%), and lithium (2.2%). The presence of aluminum (0.7%), copper (1.1%), and fluorine (2.3%) indicates industrially shredded blackmass with residual binder materials (PVDF) and possibly traces of electrolyte. Following oxidative roasting, the carbon content dramatically decreases to 15.8% due to the conversion of graphite and carbon coatings from LFP structures. Simultaneously, the relative concentrations of active material components increase substantially, with phosphorus rising to 13.8%, iron to 21.9%, and lithium to 3.5%. The reduction in fluorine content (from 2.3% to 1.1%) demonstrates partial decomposition of PVDF binders during thermal treatment, while the compositional shifts overall reflect successful thermal preprocessing of the blackmass for subsequent hydrometallurgical lithium extraction.

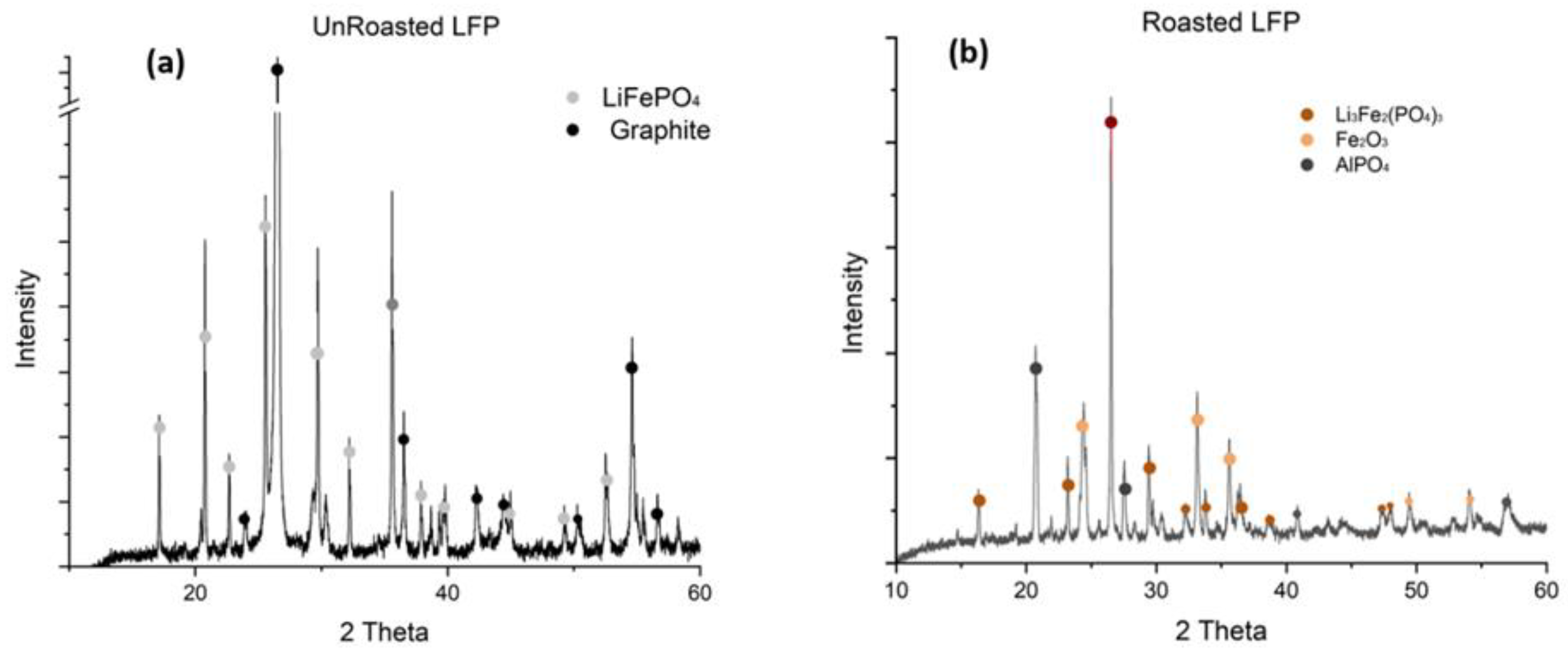

The mineralogical composition of the unroasted and roasted blackmass was analyzed by X-ray diffraction shown in Fig. 3.

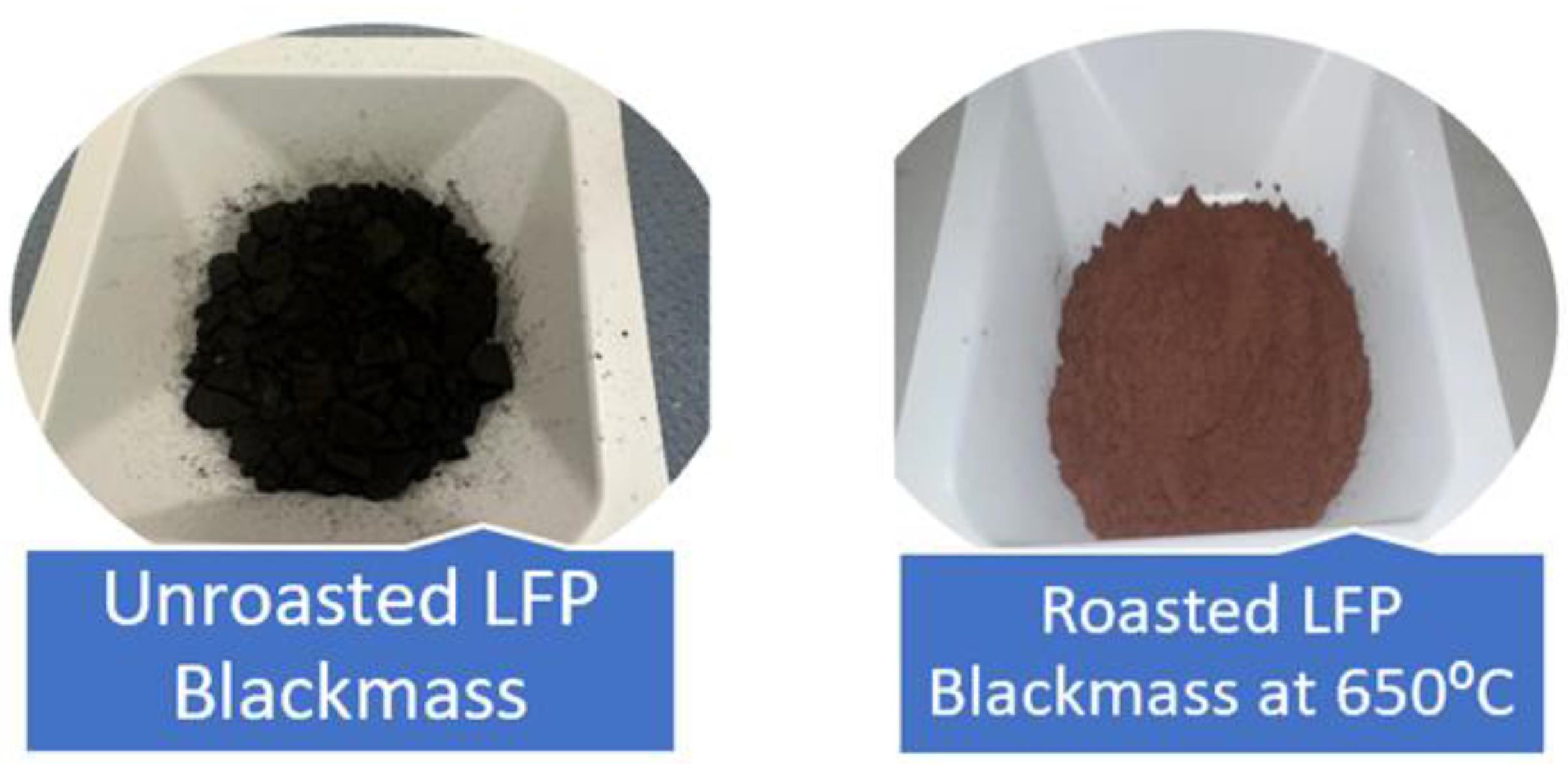

The XRD patterns reveal dramatic structural transformations in the blackmass following oxidative roasting treatment. In the unroasted blackmass, the diffractogram is dominated by an intense, sharp graphite reflection at approximately 26° 2θ, with relatively minor LiFePO₄ reflections, indicating the prevalence of graphite in the initial battery waste material. After roasting at 650°C, the graphite peak was taken over by the Lithium compound, confirming successful carbon removal. Concurrently, the olivine-type orthorhombic LiFePO₄ phase transforms into Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃, as evidenced by multiple new diffraction reflections. The formation of Fe₂O₃ reflections confirms the complete oxidation of Fe(II) to Fe(III), while the appearance of AlPO₄ reflections indicates reactions involving aluminum impurities during thermal treatment. These phase transformations, particularly the conversion to Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃, could be favorable for effective lithium extraction, as this phase is supposed to exhibit significantly enhanced lithium leachability compared to the original LiFePO₄ structure. The roasting was also confirmed with the color change (

Figure 4), just as reported by Wang et al 2024 [23] and Zhang et al [28]

The loss of weight was 11% up to 650°C, which is following the findings of Lai et al 2023 [17], Li et al, 2022 [29], and Müller et al 2024 [24]. The first study used LFP cathode mixed with graphite as input material from real batteries, where it was also shown some contaminants such as Al and Cu, which revealed, after 600°C of oxidation environment for 1h, the presence of Li3Fe2(PO4)3, Fe2O3, Graphite, and LiFePO4 un-decomposed.

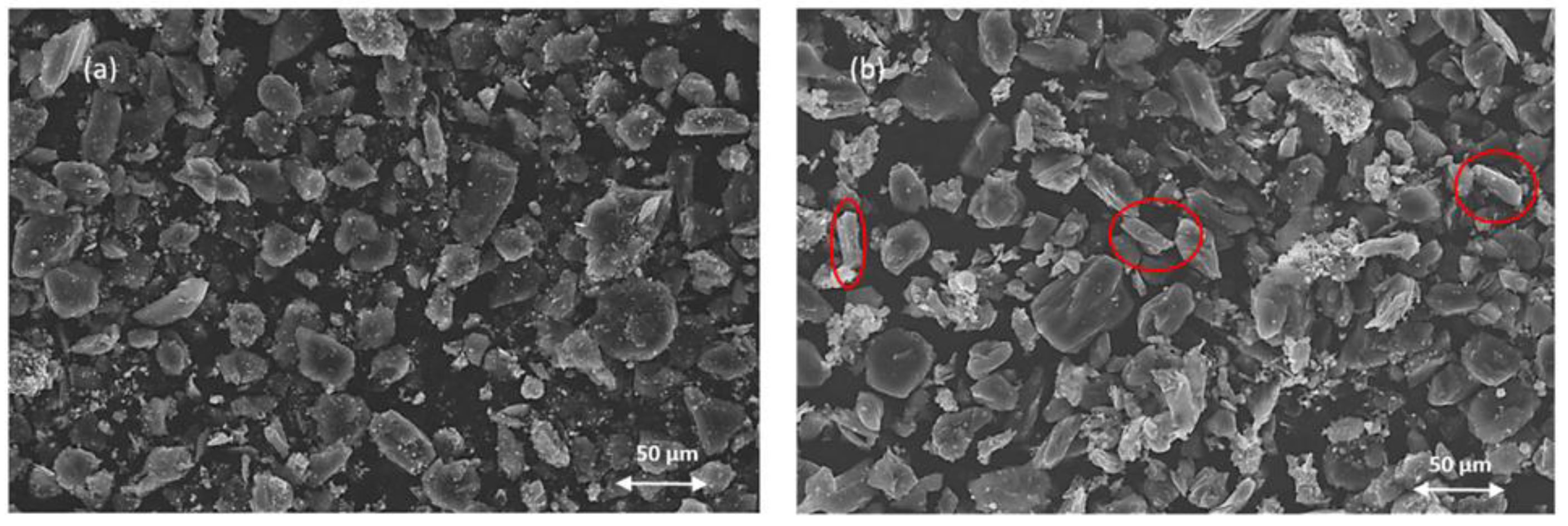

Figure 5(a) displays a heterogeneous mixture where angular, bright particles (representing LiFePO₄ cathode material) are distributed among darker, fine graphite particles (anode material). While most active materials appear well-liberated, notable graphite agglomeration is observed, with fine LiFePO₄ particles adhering to graphite surfaces due to PVDF binder interactions. The particle size distribution is notably varied, with LiFePO₄ generally exhibiting larger dimensions compared to graphite components. Following oxidative roasting (

Figure 5b), the microstructure demonstrates markedly improved particle liberation and reduced agglomeration, attributed to PVDF decomposition above 350°C. The formation of distinctive rod-like particles indicates the successful oxidation of iron to Fe₂O₃ (hematite), confirming the phase transformation observed in XRD analysis. The particles exhibit clearer boundaries and improved separation, facilitating enhanced accessibility to lithium-bearing phases during leaching. These morphological changes align with the compositional transformations previously identified and suggest improved leaching kinetics for lithium recovery.

3.2. Selectivity of Lithium Leaching

The purpose of H2O2 usage in combination with an acid is explained by the formation of an oxidative environment within an acidic leaching system, which several authors have already studied [7,25,28]. Such conditions allow Fe(II) from the LiFePO4 molecule, after dissolution, to be oxidized into Fe (III). Then the reaction with PO43- takes place, forming FePO4, which is not soluble in these conditions. Consequently, Li is selectively dissolved in solution whilst FePO4 precipitates. Besides the selectivity, the maximization of the Li leaching efficiency is also targeted. Both these aspects are evaluated in this section with the assistance of the analysis of variance (ANOVA) method. The leaching efficiency of the LFP BM main components was evaluated for roasted and unroasted BM in different final pH values.

The first outcome of such analysis is the significance of each factor and the interaction between them, in relation to the response, which is the leaching efficiency. The significance is measured by the calculated p-value, which is shown in

Table 1 for each component. In green are the p-values lower than 0.05 (i.e., 5%), which is the common standard value in statistical analysis that defines the significance aspect in the studied system. With that in mind, the evaluation allows the conclusion that the final pH was significant for all chemical elements, which was expected due to each individual chemical element’s hydrometallurgical behavior. However, even though the final pH is very different – acid vs. Low pH water leaching – the p-value provided an interesting insight: regardless of the change in this factor, the leaching efficiency of Fe, P, and Cu remains practically unchanged when the BM is roasted. The p-value of the interaction between factors also shows that Fe and Cu leaching efficiencies are not significant, which will be addressed with the analysis of the interaction plot. The complete ANOVA statistical analysis is detailed in the Supplementary Material.

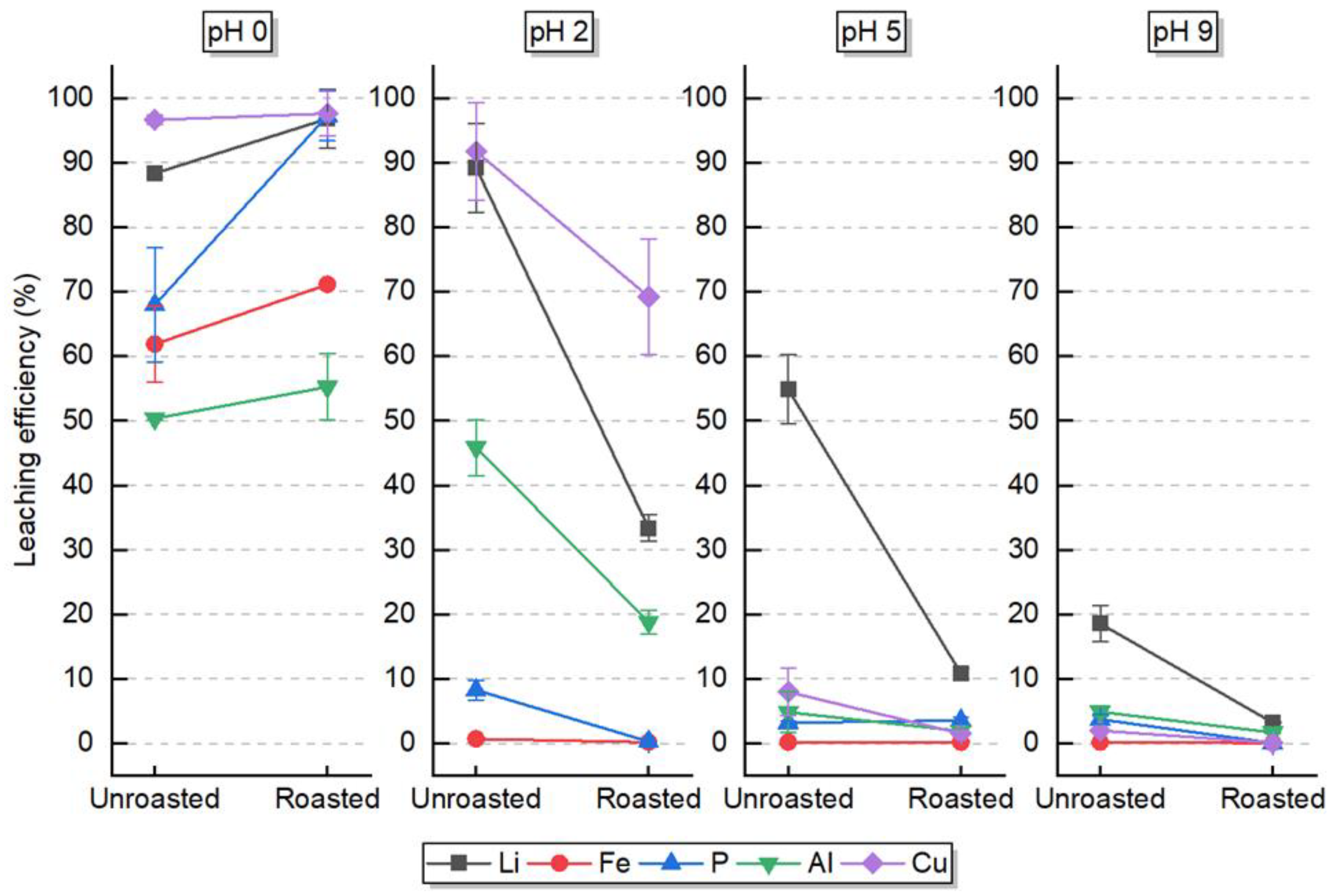

In

Figure 6 it is showed the effect of the interaction between both factors on the leaching efficiency for each LFP component is shown, where it is possible to observe in more detail what the p-values mean. For Fe and P, in red and blue respectively, it is possible to observe that when the BM is roasted, in three final pH values, the increase or decrease of leaching efficiency is practically negligible, with exception of the final pH 0, where a sharp decrease is observed for P in the unroasted BM. This is the reason both these components showed p-values higher than 0.05. The same is observed for Cu, but at the final pH of ~2.

The other interactions between factors show a p-value lower than 0.05, which is significant and can be seen in

Figure 6 with great variations of leaching efficiency. When both roasted and unroasted BM are leached at pH 9, a poor leaching efficiency of less than 20% is observed. Nonetheless, a slight selectivity of Li against other elements can be observed for unroasted BM. According to the E-pH diagram for the unroasted LPF system, Li3PO4 could be formed, which indeed presents solubility very low solubility [5,31,32]. Moreover, even though there is no information about the solubility of Li3Fe2(PO4)3, these results suggests that its solubility is not reached in such conditions of 40 g/L and 20°C, however it was reported that roasted virgin LFP material achieved 33% of Li leaching efficiency in water with higher S/L ratio (80 g/L) and temperature (60°C), whilst Fe leaching efficiency was negligible [23]. A similar behavior is observed in pH 5, where a hint of H2SO4 was used (approximately 5 mL 2 mol/L), but with a greater selectivity for the unroasted BM. However, the leaching efficiency of Li reached only 33% against less than 8% for Cu, which is still unsatisfactory for achieving the EU goals [30], for example.

At pH 0, the behavior of the five chemical elements is completely the opposite: leaching efficiencies higher than 50% for all chemical elements in both roasted and unroasted BMs, which demonstrates a poor level of selectivity of Li against the other elements. It can be though observed that the roasted BM showed higher leaching efficiency for all elements, especially for P. Cu is probably unaffected by the roasting, which is dissolved in pH 0 [33]. With unknown pH but 500°C roasted BM and leaching conditions of 100 g/L, 60°C for 40 min and 0.8 mol/L H2SO4, a study [18] showed a lower leaching efficiency, possibly due to the formation of more stable oxide structures at higher temperatures. Yang et al, 2021 [34] also reported a decrease in leaching efficiency when the roasting was performed in an oxidizing environment, although not significant, which suggests that the leaching of Fe became difficult.

The selectivity of Li against Fe and P, combined with a high leaching efficiency of 90%, is only observed at pH 2 for unroasted BM, where a hint of H2SO4 was added controllably (approx. 10 mL). In this situation, Al and Cu also showed considerably high leaching efficiencies, however, the final concentration in solution of both these metals is 7 times lower than the concentration of Li, circa 180 mg/L, which could facilitate further refinement.

In general, unroasted BM showed higher leaching efficiencies than roasted BM for all components. Since no data were found for the solubility of Li3Fe2(PO4)3, it is suggested that this compound is insoluble at mild pH values. In addition, for the roasted BM, most of the Fe(II) from LiFePO4 is oxidized, forming Fe2O3, which is not leached easily even by strong acid media[35]. On the other hand, LiAlO2 could also be formed during the roasting of the BM, which is a compound known as indissoluble [27,28].

Another important aspect that adds errors is possibly the presence of binder, separators, and electrolyte of LFP batteries on the unroasted BM. The presence of residues of organic matter could encapsulate the LFP particles, hindering the leaching process. This is observed by the presence of Fluorine from the electrolyte. In the unroasted BM, the content is 2.26 wt.% against only 1.14 wt.% in the roasted BM.

3.3. Characterization of Solid Residues

The solid residues (cakes) obtained after leaching were analyzed using XRD and SEM techniques to understand phase composition changes resulting from the combined oxidative roasting and leaching treatments. This section compares the outcomes of selective mild-acid leaching (pH 2) versus strong acid leaching (pH 0).

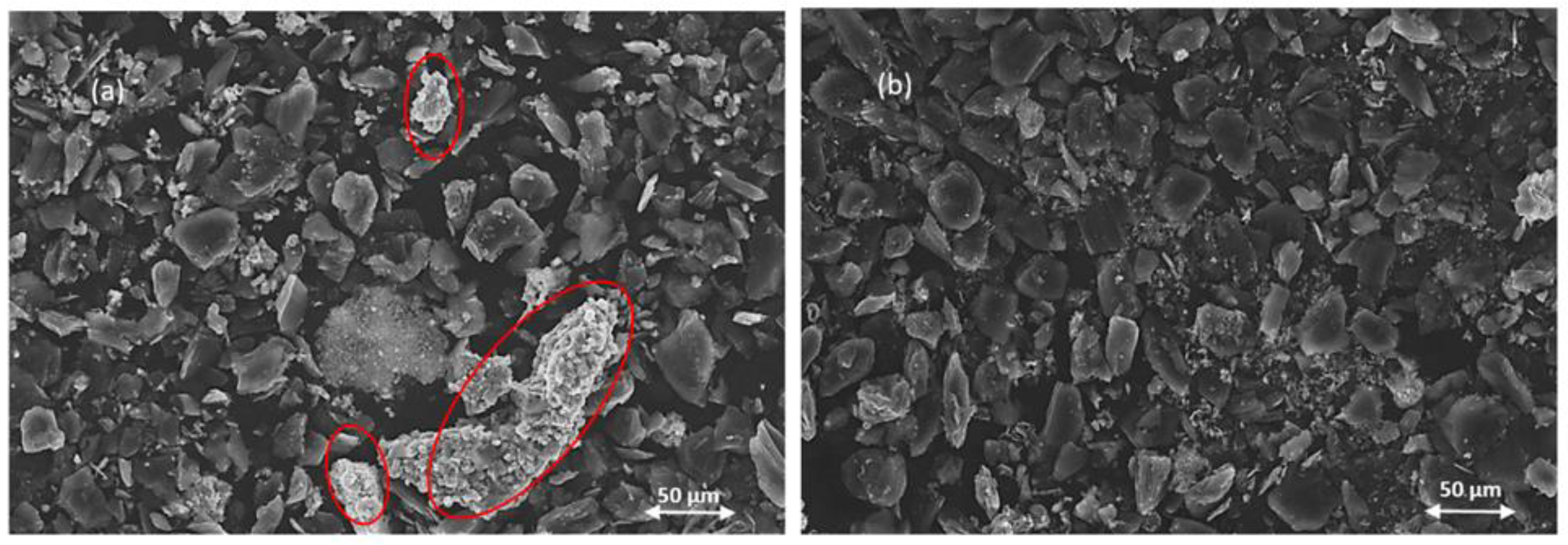

SEM analysis reveals striking differences in particle morphology between the two leaching methods. In the mild-acid leaching residue (pH 2), numerous fine white particles remain visible on the surfaces of larger particles, as shown in

Figure 7(a). This indicates that water-soluble lithium compounds, particularly Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃, persist in the residue after mild-acid leaching. In contrast, the acid-leached sample (pH 0) shows a cleaner surface with complete removal of these white particles. Instead, we observe the formation of distinctive rod-like spherical crystalline structures of Fe₂O₃ alongside graphite particles, which constitute most of the precipitate.

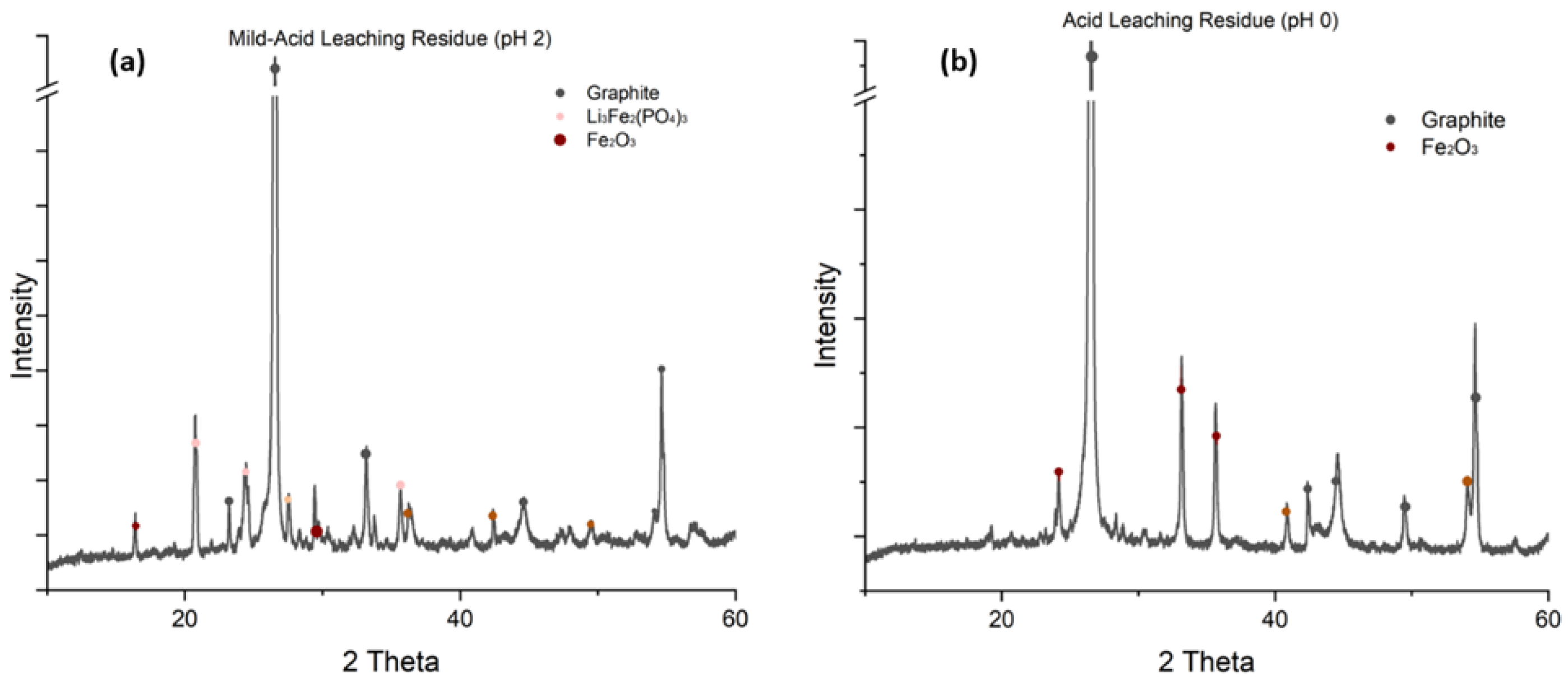

The XRD patterns provide further confirmation of these observations.

Figure 8(a) shows that the mild-acid leaching residue still contains significant amounts of water-soluble Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃, demonstrating incomplete lithium extraction under mild pH 2 conditions. The presence of Fe₂O₃ reflections confirms that the roasting treatment at 650°C for 1 hour successfully oxidized Fe (II) to Fe (III), transforming the original LiFePO₄ structure. In contrast,

Figure 8(b) shows that the acid leaching residue contains only graphite and minor Fe₂O₃ reflections, with no detectable lithium-containing compounds, indicating highly efficient lithium recovery through acid leaching of the roasted blackmass.

4. Discussion

This study reveals a critical paradox in lithium iron phosphate (LFP) recycling: while oxidative roasting successfully transforms LiFePO₄ into water-soluble Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃ (Equation 1), its benefits are overshadowed by the complex reality of industrial blackmass. Our results challenge the assumption that thermal pretreatment universally enhances lithium recovery, particularly when applied to real-world battery waste rich in graphite (~46%) and impurities (Al, Cu, F).

4.1. Oxidative Roasting Mechanism and Phase Transformations

At 650°C in air, LiFePO₄ undergoes oxidation to form water-soluble Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃ and Fe₂O₃, as described by the following chemical equation(1)

Concurrently, graphite combusted (C + O

2 → CO

2), reducing carbon content from 46.6% to 18.4% (

Figure 2). This eliminates carbon coatings too, exposing Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃ for efficient leaching as seen in

Figure 9. Binder decomposition (PVDF) above 350°C also liberates adhered particles (

Figure 5), while residual fluorine drops from 2.3% to 1.3%, minimizing interference during leaching. At elevated temperatures, partial decomposition of Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃ occurs:

4.2. Selective Leaching Behavior

The effect of oxidative roasting on the leaching conditions (different pH values) was found to be beneficial for the maximization of Li leaching efficiency only at pH 0. In this situation, the concentration of H

2SO

4 is high, which enables the breaking of chemical bonds and promotes the liberation of each chemical element. The chemical reaction (4) occurs, and it is believed that a similar reaction involving the compound Li

3Fe

2(PO

4)

3 might also occur.

Although Fe is present in different compounds for roasted and unroasted, the leaching was considerably high, as well as for P, which means no Li selectivity was achieved. In addition, the presence of binders or any organic material is not hindered significantly at pH 0, however, it must be mentioned that the consumption of acid is high, which also brings a high concentration of sulfur to the wastewater. The sustainable and green approach is compromised in this alternative.

In both higher pH values of 5 and 9, the unroasted BM showed higher selectivity but poor Li extraction. According to the E-pH diagram of the pure LiFePO

4 compound, the region of pH 9 is not favorable for the formation of ions. At pH 5 and in a high oxidation environment, the selectivity is achieved, however, the leaching efficiency of Li is compromised, not reaching 60%. The chemical reaction (5) might occur, which allows the recombination of Fe and PO

4 to form insoluble FePO

4.

The best scenario is shown in pH 2, with a hint of H2SO4 and unroasted BM. In this case, the roasting of the LFP BM, while eliminating F and any possible binder or electrolyte that could hinder the leaching, shows a negative result in relation to the Li leaching efficiency but a good result in terms of selectivity, since Fe and P showed nearly zero percentage. The reason behind this might be connected to the compound Li3Fe2(PO4)3 or the formation of other Li-compounds undetected by XRD, which are insoluble. For a complete assessment, the thermodynamic behavior of these roasted phases must be investigated.

4.3. Impurity Behavior and Selectivity

Unroasted blackmass showed high Al/Cu leaching (up to 50%) due to PVDF-bound particles (

Figure 6). Roasting reduced their dissolution by 70–80%, as Al oxidized to aluminium Oxides and Cu formed stable oxides. This aligns with E-pH diagrams[31], where neutral-to-alkaline conditions favor FePO₄/Li₃PO₄ stability, suppressing impurity solubility.

Several factors help explain why roasting underperformed. First, the high graphite content (about 46%) in our blackmass, while reduced during roasting, created a porous and reactive matrix that physically trapped lithium phosphate particles. This encapsulation limited the exposure of Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃ to the leaching solution, reducing the effectiveness of subsequent lithium extraction. Second, although roasting reduced the fluorine content by breaking down PVDF binders, some binder residues persisted, likely forming hydrophobic coatings that further hindered water penetration and lithium dissolution. Our SEM images supported this, showing agglomerated particles and uneven surfaces in the roasted residues.

Another important factor is the complexity of industrial blackmass itself. Unlike laboratory-prepared LFP cathodes, our material contained notable amounts of aluminum and copper. During roasting, these impurities formed stable oxides that may have adsorbed or trapped lithium ions, effectively locking them in the solid phase and making them less accessible during leaching. This is supported by our leaching results, which showed that acid leaching could extract over 95% of the lithium but also dissolved significant amounts of iron and other impurities, undermining the selectivity and purity of the recovered lithium.

These findings challenge the common assumption that roasting always enhances lithium recovery, especially for real-world battery waste. Our results suggest that the benefits of roasting are highly dependent on the composition and structure of the feedstock. For high-graphite, impurity-rich blackmass, the energy and material costs of roasting may not be justified, especially when similar lithium recovery can be achieved through direct hydrometallurgical processing. This insight points to the need for recycling protocols that are tailored to the specific characteristics of the input material, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all approach.

5. Conclusions

Our work reveals a critical gap between lab-scale recycling studies and industrial reality. While roasting transformed LiFePO₄ into water-soluble Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃ (Eq I), reducing carbon content by 60% and fluorine (from PVDF) by 43%, its benefits were compromised by the black mass’s inherent complexity. In our research, under optimized conditions (40 g/L solid/liquid ratio, 20°C), water leaching (pH 2, water + H₂O₂ + Hint of H₂SO₄) achieved 33% lithium recovery much lower than unroasted LFP with 90%, while acid leaching (pH 0, 2M H₂SO₄ + H₂O₂) reached 95.4% efficiency, albeit with higher impurity dissolution.

These results highlight that the high graphite content, persistent PVDF residues, and the presence of aluminum and copper impurities can limit the effectiveness of roasting as a pretreatment step.

Our findings emphasize that recycling strategies must be tailored to the specific composition and complexity of real-world battery waste. For graphite-rich blackmass, direct hydrometallurgical processing may offer a more practical and sustainable solution than energy-intensive roasting.

Future work must prioritize kinetic studies to accelerate Li₃Fe₂(PO₄)₃ dissolution, low-temperature binder removal to avoid graphite pitfalls, and collaboration with manufacturers to reduce PVDF/Al in next-gen batteries. As LFP dominates the EV revolution, recycling innovation must embrace feedstock complexity-because sustainability is not just about chemistry, but adaptability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.M. and A.T.; Methodology, D.M., A.T.; Validation, D.M., A.T.; Formal Analysis, D.M., A.T.; Investigation, A.T.; Resources, D.M., A.T.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, D.M., A.T; Writing – Review & Editing, R.Y., A.B., B.F.; Visualization, D.M., A.T.; Supervision, D.M., B.F., R.Y.; Project Administration, A.B., R.Y.; Funding Acquisition, R.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the materials characterization facility (XRD, SEM) at TGGS, Bangkok. We would also like to thank the analytical laboratory (ICP-OES) of the institute for the great teamwork.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- F. Larouche et al., “Progress and Status of Hydrometallurgical and Direct Recycling of Li-Ion Batteries and Beyond,” Materials, vol. 13, no. 3, Art. no. 3, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Li et al., “Progress, challenges, and prospects of spent lithium-ion batteries recycling: A review,” J. Energy Chem., vol. 89, pp. 144–171, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. D. M. Gonzalez, M. Villen-Guzman, C. Vereda, J. Rodríguez-Maroto, and J. Paz-García, “Towards Sustainable Lithium-Ion Battery Recycling: Advancements in Circular Hydrometallurgy,” Processes, vol. 12, p. 1485, Jul. 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. Woeste et al., “A techno-economic assessment of two recycling processes for black mass from end-of-life lithium-ion batteries,” Appl. Energy, vol. 361, p. 122921, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. Forte, M. Pietrantonio, S. Pucciarmati, M. Puzone, and D. Fontana, “Lithium iron phosphate batteries recycling: An assessment of current status,” Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol., Jun. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Gaines, K. Richa, and J. Spangenberger, “Key issues for Li-ion battery recycling,” MRS Energy Sustain., vol. 5, no. 1, p. 12, Nov. 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Jin, J. Zhang, D. Wang, Q. Jing, Y. Chen, and C. Wang, “Facile and efficient recovery of lithium from spent LiFePO4 batteries via air oxidation–water leaching at room temperature,” Green Chem., vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 152–162, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu et al., “Advances and perspectives towards spent LiFePO4 battery recycling,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 434, p. 140077, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Ma et al., “The Recycling of Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries: Crucial Flotation for the Separation of Cathode and Anode Materials,” Molecules, vol. 28, no. 10, Art. no. 10, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Billmann, “Comparative study of Li-ion battery recycling processes,” 2020. Accessed: May 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Comparative-study-of-Li-ion-battery-recycling-Billmann/49296b1a532511330da4f7f90364eea5ad4af48f.

- C. Stallmeister and B. Friedrich, “Holistic Investigation of the Inert Thermal Treatment of Industrially Shredded NMC 622 Lithium-Ion Batteries and Its Influence on Selective Lithium Recovery by Water Leaching,” Metals, vol. 13, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “A Novel Pyrometallurgical Recycling Process for Lithium-Ion Batteries and Its Application to the Recycling of LCO and LFP.” Accessed: May 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4701/11/1/149.

- “Recovery of Lithium, Iron, and Phosphorus from Spent LiFePO4 Batteries Using Stoichiometric Sulfuric Acid Leaching System | ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering.” Accessed: May 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b01594.

- Z. Li, Q. Zheng, A. Nakajima, Z. Zhang, and M. Watanabe, “Organic Acid-Based Hydrothermal Leaching of LiFePO4 Cathode Materials,” Adv. Sustain. Syst., vol. 8, no. 4, p. 2300421, 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Liu, Z. Liu, J. Gu, H. Yuan, Y. Wu, and Y. Chen, “A facile new process for the efficient conversion of spent LiFePO4 batteries via (NH4)2S2O8-assisted mechanochemical activation coupled with water leaching,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 471, p. 144265, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “Hydrometallurgical Recovery of Spent Lithium Ion Batteries: Environmental Strategies and Sustainability Evaluation | ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering.” Accessed: May 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c00942.

- Y. Lai et al., “Recycling of spent LiFePO4 batteries by oxidizing roasting: Kinetic analysis and thermal conversion mechanism,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., vol. 11, no. 5, p. 110799, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Obuz, F. Tekmanlı, L. Mettke, M. Müller, and B. Yagmurlu, Investigation of Recycling Behavior of Lithium Iron Phosphate Batteries with Different Thermal Pre-Treatments. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang et al., “Recovery of LiFePO4 from used lithium-ion batteries by sodium-bisulphate-assisted roasting,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 379, p. 134748, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Biswas, S. Ulmala, X. Wan, J. Partinen, M. Lundström, and A. Jokilaakso, “Selective Sulfation Roasting for Cobalt and Lithium Extraction from Industrial LCO-Rich Spent Black Mass,” Metals, vol. 13, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Li, J. Zhang, W. Zhao, D. Lu, G. Ren, and Y. Tu, “Application of Roasting Flotation Technology to Enrich Valuable Metals from Spent LiFePO4 Batteries,” ACS Omega, vol. 7, no. 29, pp. 25590–25599, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. Zheng et al., “Optimized Li and Fe recovery from spent lithium-ion batteries via a solution-precipitation method,” RSC Adv., vol. 6, no. 49, pp. 43613–43625, Apr. 2016. [CrossRef]

- D.-F. Wang et al., “Revealing role of oxidation in recycling spent lithium iron phosphate through acid leaching,” Rare Met., vol. 44, no. 3, pp. 2059–2070, Mar. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Müller, H. E. Obuz, S. Keber, F. Tekmanli, L. N. Mettke, and B. Yagmurlu, “Concepts for the Sustainable Hydrometallurgical Processing of End-of-Life Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) Batteries,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 24, Art. no. 24, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhao et al., “Direct selective leaching of lithium from industrial-grade black mass of waste lithium-ion batteries containing LiFePO4 cathodes,” Waste Manag., vol. 171, pp. 134–142, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Greil, J. Chai, G. Rudelstorfer, S. Mitsche, and S. Lux, “Water as a Sustainable Leaching Agent for the Selective Leaching of Lithium from Spent Lithium-Ion Batteries,” ACS Omega, vol. 9, no. 7, pp. 7806–7816, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jie, S. Yang, Y. Li, D. Zhao, Y. Lai, and Y. Chen, “Oxidizing roasting behavior and leaching performance for the recovery of spent lifepo4 batteries,” Minerals, vol. 10, no. 11, Art. no. 11, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhang, X. Yuan, C. Y. Tay, Y. He, H. Wang, and C. Duan, “Selective recycling of lithium from spent lithium-ion batteries by carbothermal reduction combined with multistage leaching,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 314, p. 123555, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lai et al., “Recycling of spent LiFePO4 batteries by oxidizing roasting: Kinetic analysis and thermal conversion mechanism,” J. Environ. Chem. Eng., vol. 11, no. 5, p. 110799, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- “New EU regulatory framework for batteries: Setting sustainability requirements | Think Tank | European Parliament.” Accessed: May 15, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2021)689337.

- Y. Zhang, J. Ru, Y. Hua, M. Cheng, L. Lu, and D. Wang, “Priority Recovery of Lithium From Spent Lithium Iron Phosphate Batteries via H2O-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents,” Carbon Neutralization, vol. 4, no. 1, p. e186, 2025. [CrossRef]

- W. M. Haynes, Ed., CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 97th ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Kasuno, A. Kitada, K. Shimokawa, and K. Murase, “Suppression of Silver Dissolution by Contacting Different Metals during Copper Electrorefining,” J. MMIJ, vol. 130, pp. 65–69, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- C. Yang, J. Zhang, Q. Jing, Y. Liu, Y. Chen, and C. Wang, “Recovery and regeneration of LiFePO4 from spent lithium-ion batteries via a novel pretreatment process,” Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater., vol. 28, no. 9, pp. 1478–1487, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- B. Seo et al., “Selective leaching behavior of Nd from spent NdFeB magnets treated with combination of selective oxidation and roasting processes,” Hydrometallurgy, vol. 227, p. 106320, Aug. 2024. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).