1. Introduction

Electrophilic aromatic substitution has been the object of an extensive work in the history of organic chemistry [

1]. Koerner (

Figure 1), a student of Cannizzaro in Palermo, studied in detail the electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction. Already in a first article published in 1869 [

2], Koerner identified the equivalence of the carbon atoms present in the benzene ring.

This work will find its maximum expression a few years later in a monumental article published by Koerner in the Gazzetta Chimica Italiana [

3]. In this article Koerner prepares hundreds of aromatic compounds derived from benzene at different degrees of substitution. Beyond the preparative aspect, in itself relevant, Koerner at the end of the article tries to draw some conclusions. Let us re-trace them using his words: «1. If chlorine, bromine, iodine or nitric acid act on chloro-, bromo-, or iodobenzene, on aniline, phenol or toluene, in such a way as to replace a single hydrogen atom in the aforementioned bodies, thus generating a bisubstituted derivative, a derivative belonging to the 1,4 series is always formed as the main derivative and at the same time a derivative of the 1,2 series originates as a secondary product. 2. Where the group already existing in the petrol is of an acid na-ture, being constituted by the residues COOH; NO2; SO3H, the action of the same agents […] results as the main derivative a body belonging to the 1,3 series […].» [

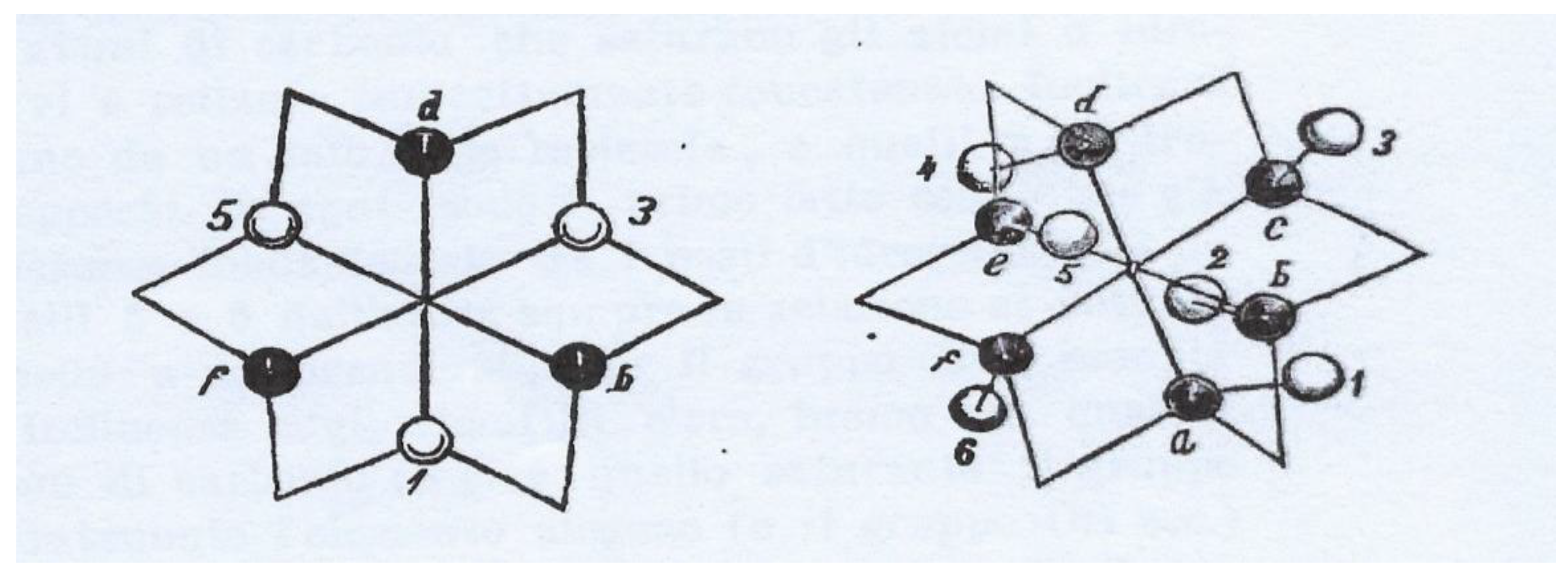

3]. Koerner therefore identifies the correct orienting effect of the substituents. He does not limit himself to this. He tries to explain the reasons for this reactivity. To do this, Koerner uses a model of the non-planar benzene molecule, a structure he had already proposed in his 1869 article (

Figure 2) [

2,

3]. In this structure, carbon atom 1 is directly bonded to carbons 2, 4 and 6. When carbon 1 is substituted, the substituent will influence the reactivity of the ortho and para carbons. The reason for the meta orientation is less clear.

It is obvious to note that the structure proposed by Koerner did not have a great future, also because we know that it is not realistic.

What remains of this great work over the following years? We have only been able to consult some teaching texts dating back to around the 1920s. The first is Parravano's lectures on General Chemistry There is a section in these lectures dedicated to organic chemistry. The orienting effect of substituents in the electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction is described, but no interpretative hypothesis is ventured. Another text that I was able to consult, Holleman's treatise on organic chemistry, translated into Italian by Plancher based on a text from the beginning of the twentieth century, with a preface by Ciamician (from 1905), is from 1927 [

4]. Also in this case, the orienting effects of substituents in the electrophilic aromatic substitution reaction are described. However, also in this case, no interpretative hypothesis of the reactivity of aromatic compounds is reported.

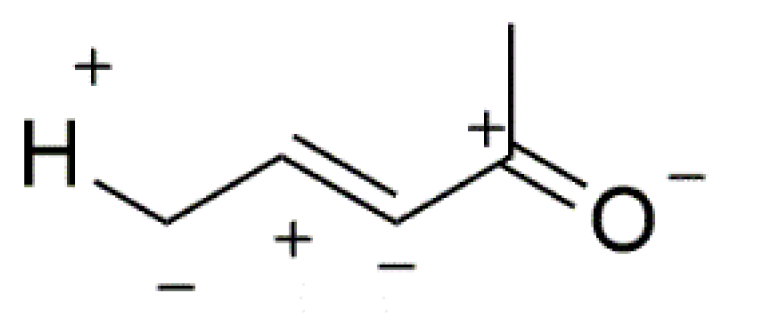

In those same years, things seem to change radically. Around the 1920s, Lapworth and Robinson formulated a first theory used to justify the progress of chemical reactions: the theory of alternating polarity [

5,

6,

7]. This theory marks the birth of studies on reaction mechanisms. What are the bases of this theory? The most electronegative atom induces a polarization of the bond that propagates to ad-jacent atoms (

Figure 3).

This type of approach has also been used in the case of electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions, as described in a book of organic chemistry written by Paul Karrer in 1942 but which had a certain success also in the following years [

8]. The Italian translation in our possession is from 1965; we can reasonably think that this text had a wide diffusion in the fifties of the twentieth century.

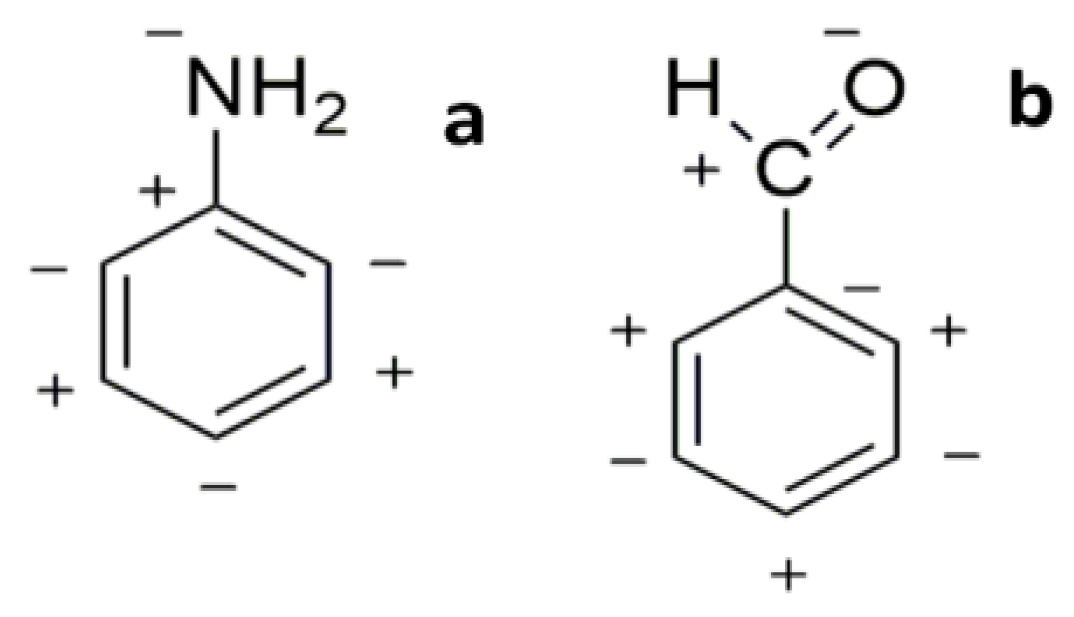

In accordance with this theory, the carbon atoms of the benzene ring are positively and negatively charged in alternation as a function of the electronegativity of the atoms bonded to it. If the benzene ring contains

ortho-para orienting substituents, the carbon atoms in

ortho and

para are negatively charged: this will cause the electrophile to attack mainly in those positions (

Figure 4a).

If the ring contains

meta-directing substituents, the negative charge will be found essentially on the carbon atoms in

meta (

Figure 4b). In this case, therefore, the electrophile will attack mainly in the

meta position. It is worth noting that there is no correspondence with the results obtained using modern computational techniques. Furthermore, this theory is not able to explain the activating or deactivating nature of the substituents. On the other hand, at that time the kinetic studies of the reactions had not yet been done.

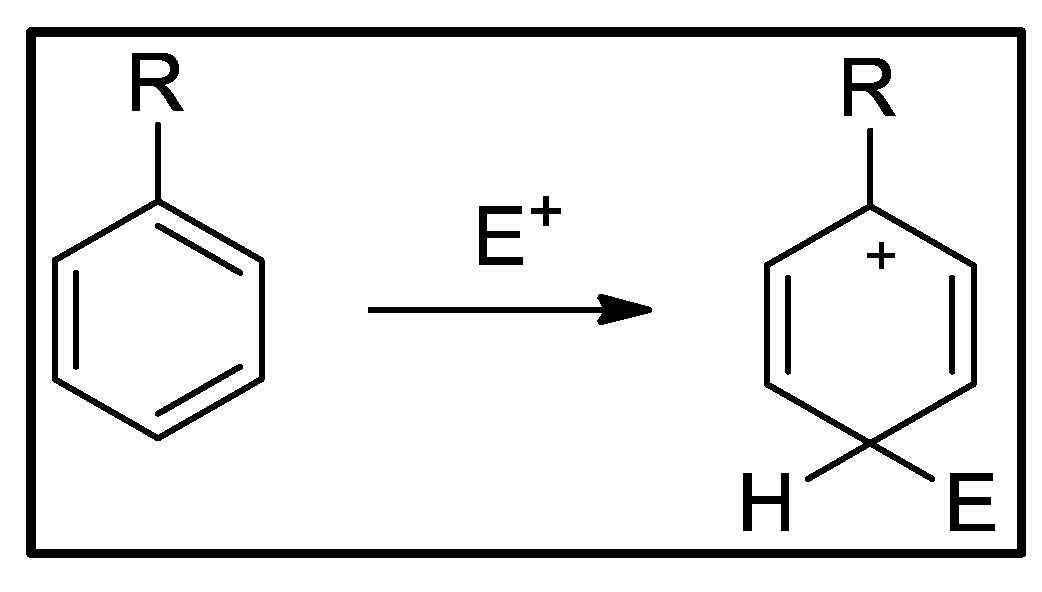

In 1942 Wheland proposed, on the basis of quantum mechanical calculations, the formation of an arenium ion as an intermediate in electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions (

Figure 5) [

9]. On the basis of the different stability of this intermediate, preceded or not by the formation of π complexes and/or by single-electron transfers, in relation to the substitution model present in the molecule, it was possible to interpret the reactivity of various aromatic compounds. The formation of the arenium ion has been demonstrated in some cases both via NMR [

10,

11,

12] and by trapping reactions [

13,

14].

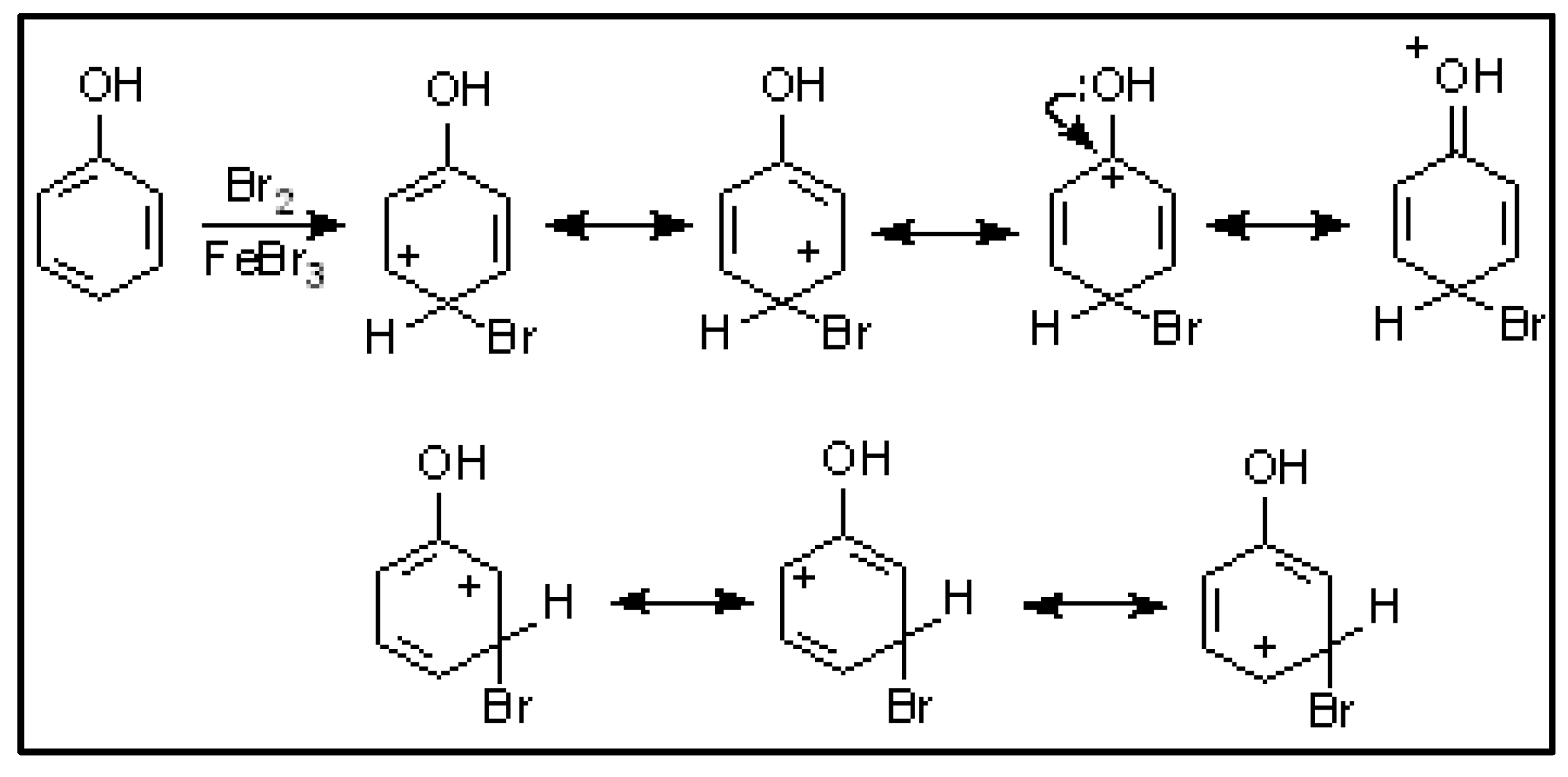

We move from a "static" to a "dynamic" theory. The formation of the arenium ion (or σ complex) is generally the slow stage of the reaction. This species has a high energy compared to the reagents, since it is not aromatic. It can be thought, on the basis of Hammond's postulate, that the factors that stabilize the σ complex also stabilize the transition state of the slow stage of the reaction. Therefore, all the isomers can be formed, and the respective reactions are in competition with each other: the factors that preferentially stabilize a transition state make this reaction faster than the others. The groups -OH, -OR, -NR

2 are all activating groups. The atom bonded to the ring is more electronegative than carbon: this makes these substituents electron-withdrawing, and therefore deactivating, by inductive effect. They also have a conjugative effect (

Figure 6), which, instead, is electron-donating and, therefore, activating. All these substituents, in fact, have a lone pair that they can share with the ring. The two effects are in contrast with each other; However, the conjugative effect is much more important than the inductive effect; overall, therefore, these substituents are electron donors and activators of electrophilic aromatic substitution. As we can see in

Figure 6, the attack in the

ortho and

para positions leads to intermediates that can be stabilized by resonance, through the formation of an additional resonance structure. These substituents are, therefore, all activating and

ortho-para orienting.

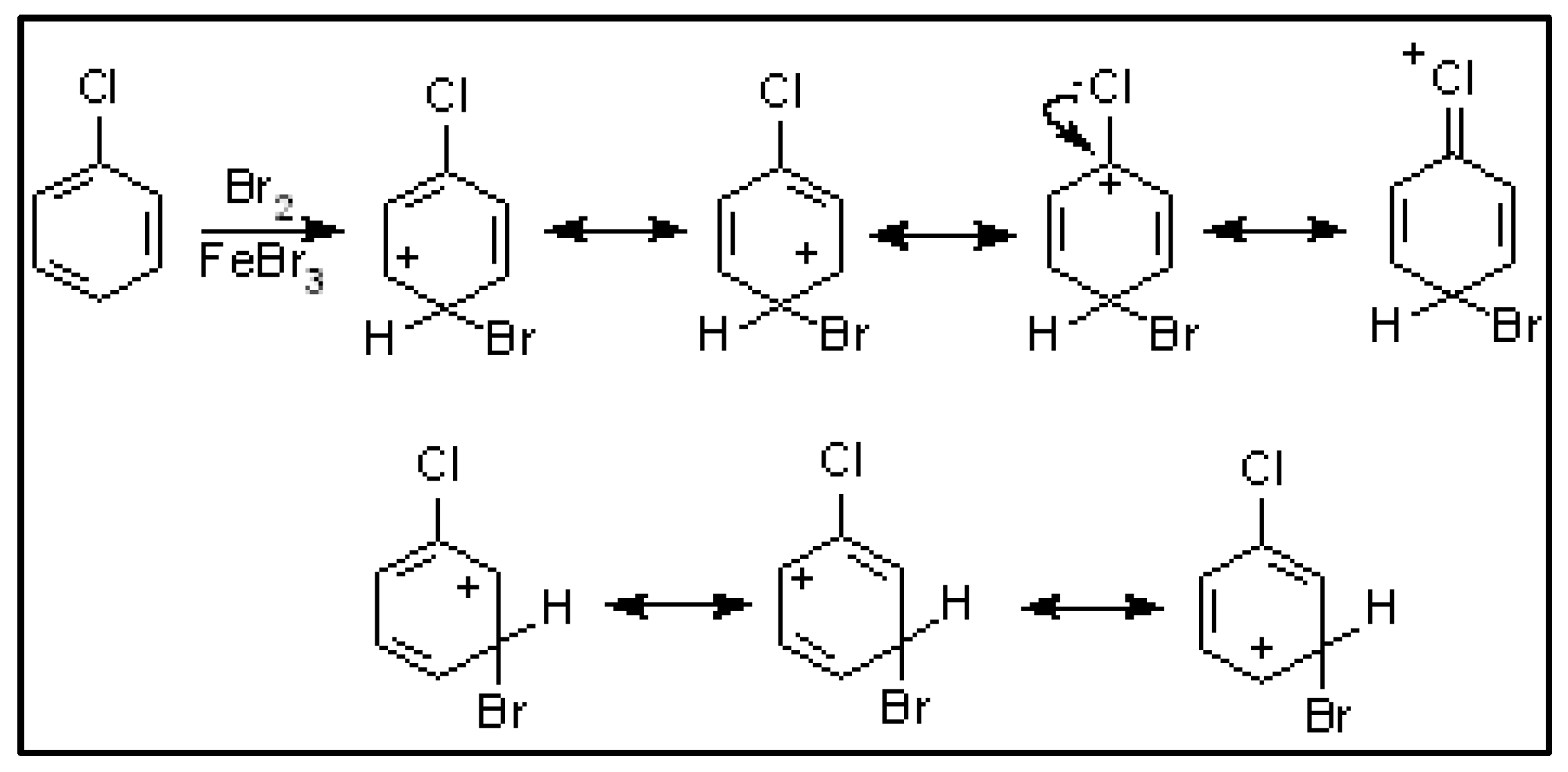

A still different case occurs when the substituent is a halogen. The halogen is clearly more electronegative than carbon: by the inductive effect, the halogen is an electron withdrawer. However, since all halogens have lone pairs, they are electron donors by the conjugative effect. Also in this case we have two contrasting effects: unlike the -OH group, however, in halogens the inductive effect prevails. Overall, halogens are electron withdrawing and, therefore, deactivating with respect to electrophilic aromatic substitution. Since the conjugative effect can stabilize the complex intermediates deriving from

ortho-para attack more than that deriving from

meta attack, these substituents are

ortho-para orienting (

Figure 7).

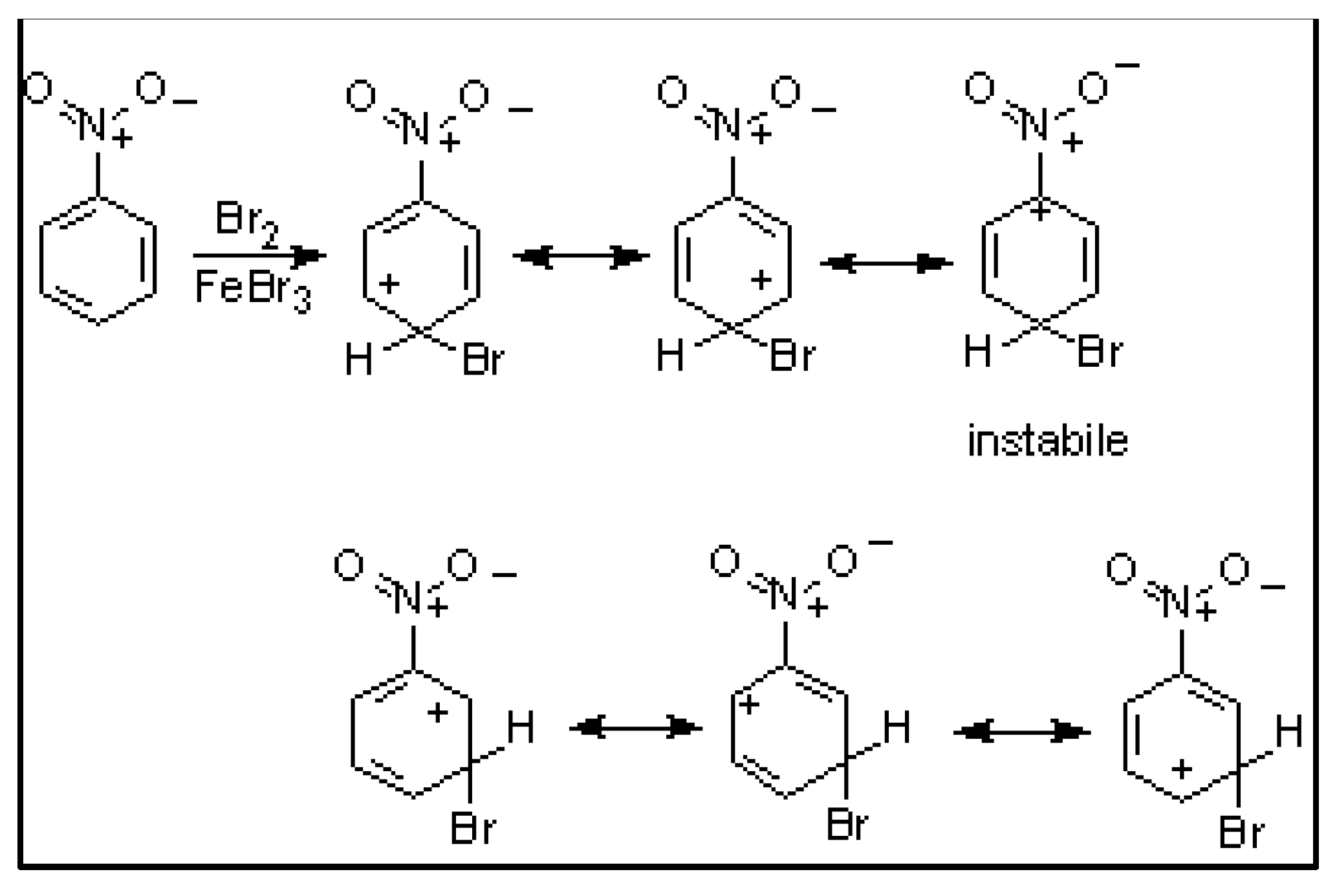

Other substituents such as -CONR

2, -CO

2R, -SO

3H, -NO

2 have the characteristic that the atom directly bonded to the ring has at least a partial positive charge. These substituents are inductively electron withdrawing; the conjugative effect is also electron withdrawing, since these substituents, being deficient in electrons on the atom bonded to the ring, will tend to attract them from the ring and are able, given their structure, to host the excess of electrons (

Figure 8). The two effects are consistent and both define these substituents as electron withdrawers and deactivators of electrophilic aromatic substitution.

This description of the reactivity of aromatic compounds is not free from limitations. It does not allow to distinguish the reactivity of benzofuran and indole. If the resonance structures of the respective σ complexes are written, no substantial difference between the two compounds is observed and both should orient the electrophilic substitution in the α position, while indole essentially gives the β substitution product. Furthermore, the approach followed to describe the electrophilic aromatic substitution does not assign any role to the electrophile: often in the graphics it is not specified at all which electrophile is being used and, in any case, no role of the entering group in the stabilization of the complex is assumed: this assumption is different from reality where significant variations can also be observed depending on the type of reaction to which the substrate is subjected. The role of the electrophile has been explained, more recently, by admitting that, with reactive electrophiles, the transition state is reached in an initial state (early). In this way the transition state will not present a real positive charge on the ring and therefore will not be affected by the presence of substituents: the result will be a poor selectivity in the reaction. On the contrary, when the electrophile is not very reactive, the transition state will be reached when the bond of the electrophile on the aromatic ring is almost formed, the positive charge on the ring will be clear, and the reaction will be greatly affected by the presence of substituents, with a consequent increase in selectivity.[

15]

During 1952 Fukui proposed frontier orbitals control in the aromatic substitution reactions [

16,

17,

18]. A few decades ago, a theoretical hypothesis was formulated that allows us to describe the energy variation of a reaction along the reaction coordinate. The equation that describes energy variation is called the Klopman-Salem equation [

19,

20,

21]. In 2016, Domingo proposed the Molecular Electron Density Theory, where the changes in the electron density are responsible for the reactivity of organic molecules [

22]. The mechanism of aromatic substitution has been discussed by using DFT calculation [

23,

24]. In 2014, charges were considered as the determining factor in

ortho/para and

meta directing effects in aromatic substitutions [

25].

In this article, we want to discuss the role of frontier orbitals and charges in some monosubstituted aromatic compounds, with particular attention to compounds showing deactivating properties.

3. Results

Nitrobenzene is a compound deactivated towards electrophilic aromatic substitution and

meta orienting compound. Nitration of nitrobenzene gave the following results:

ortho-dinitrobenzene 0.81%,

meta-dinitrobenzene 90.1%, and

para-dinitrobenzene 1.7% [

29]. Chlorination of nitrobenzene gave

ortho-chloronitrobenzene 24.1%,

meta-choronitrobenzene 68.7%,

para-chloronitrobenzene 7.1% [

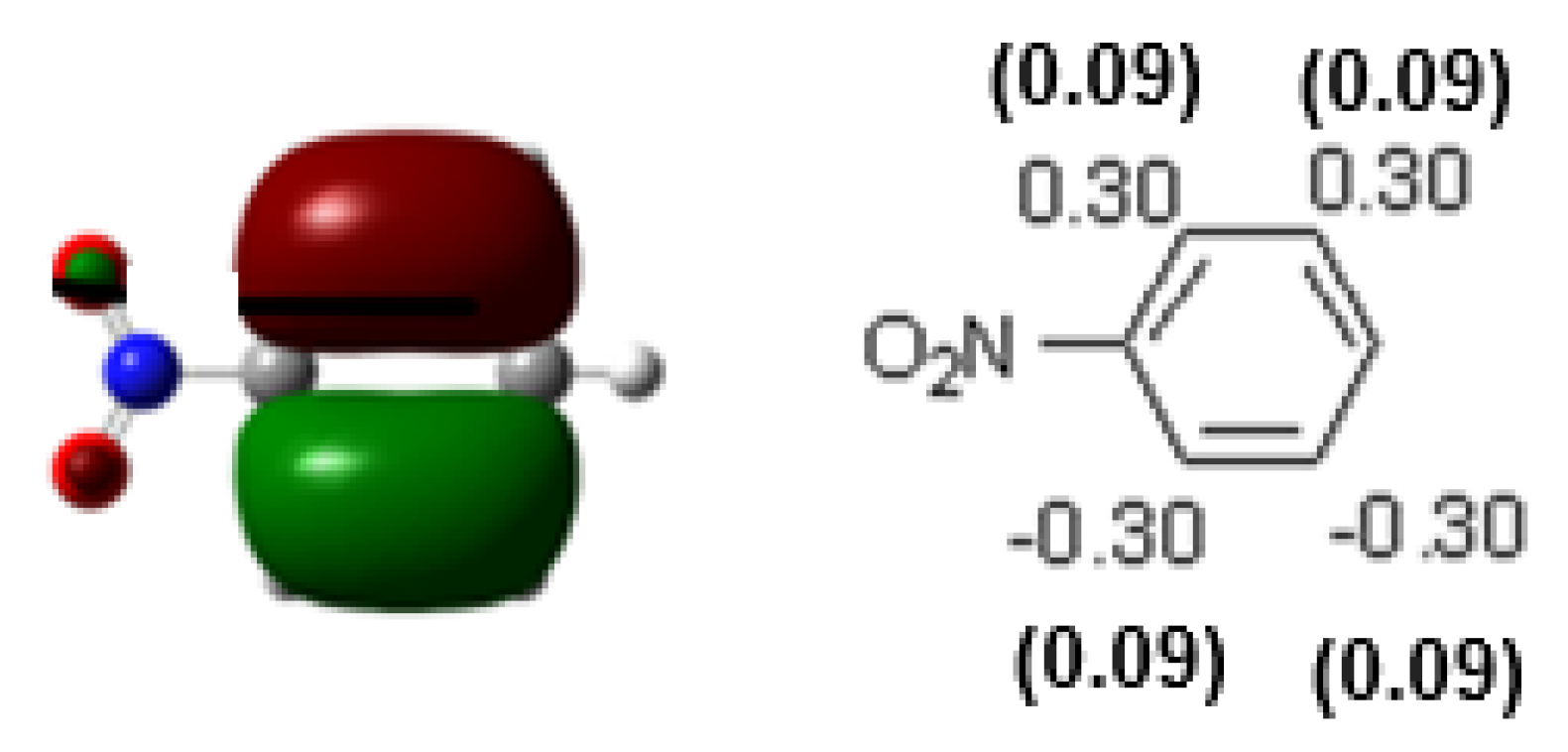

30]. We performed DFT calculations at B3LYP/aug-cc-pVDZ level of theory on Gaussian09 and the HOMO was found at -7.90 eV (

Figure 9). The atomic coefficients are not in agreement with the

meta directing behavior of this compound. The atomic coefficients are the same in

ortho and in

meta position.

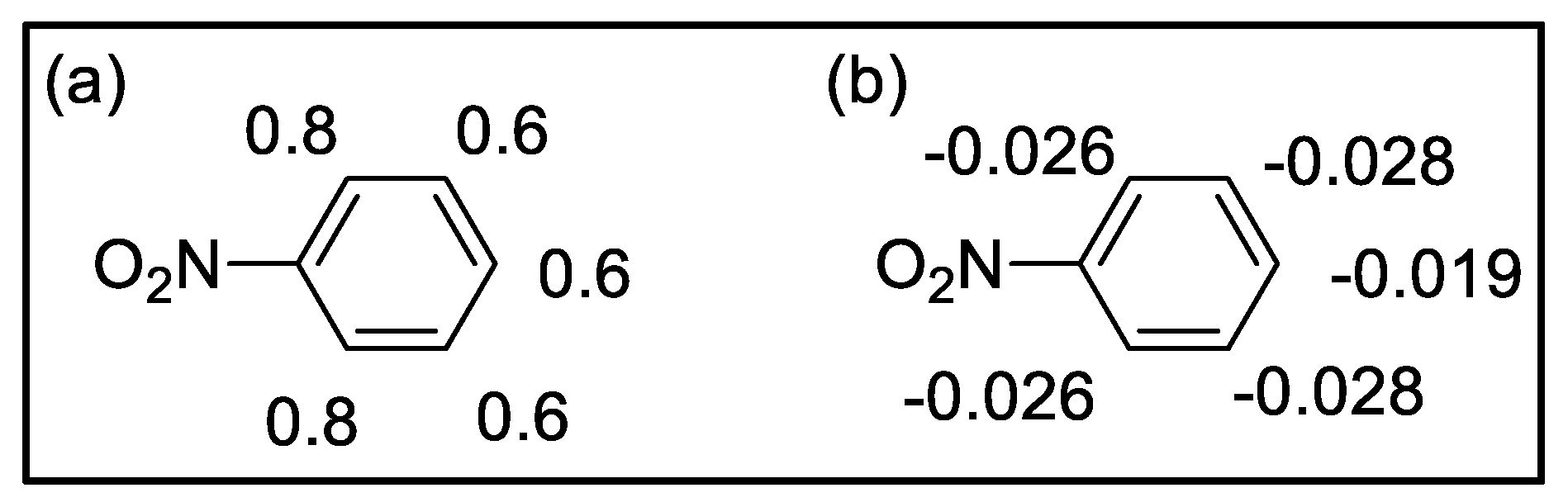

The analysis of Mulliken charges gave the distribution of charges represented in

Figure 10. All the atoms have a positive charge and this result is not in agreement with the possibility to have an electrophilic substitution reaction.

However, the smallest charges on the ring are those in

meta position, in agreement with the experimental results. It is noteworthy that also

para position on the ring has the same positive charge than the carbon atoms in

meta position. This result is not in agreement with the experimental results. However, recently Mulliken charges have not considered appropriate in discussing properties [

31]. On the contrary, Hirshfeld charges describes well reactivities of aromatic compounds [

32]. If we consider Hirshfeld charges, all the carbon atoms have negative charges, the highest charges are in

meta position, in agreement with the experimental results. However, the difference between the charges in

ortho and in

meta position is very small.

Therefore, on the basis of these data, the observed reactivity of nitrobenzene when it is subjected to a nitration reaction can be explained considering a charge effect. Nevertheless, the increase of percent yields in the ortho substituted product observed when a chlorination reaction was performed could be explained assuming a role for the HOMO in the reaction considering that the atomic coefficient in ortho and meta position are the same. However, the observed increase of the yields for the para substitued product (o-chloronitrobenzene) in comparison with those observed for the formation of o-dinitrobenzene cannot be explained considering the absence of the atomic coefficient in para position in the HOMO of nitrobenzene.

Benzonitrile showed the same behavior of nitrobenzene. Nitration of nitrobenzene gave 16%

o-nitrobenzonitrile, 80%

m-nitrobenzonitrile, and 4%

p-nitrobenzonitrile [

33,

34] On the other hand, chlorination of benzonitrile gave 34%

o-chlorobenzonitrile, 55%

m-chlorobenzonitrile, and 11%

p-chlorobenzonitrile [

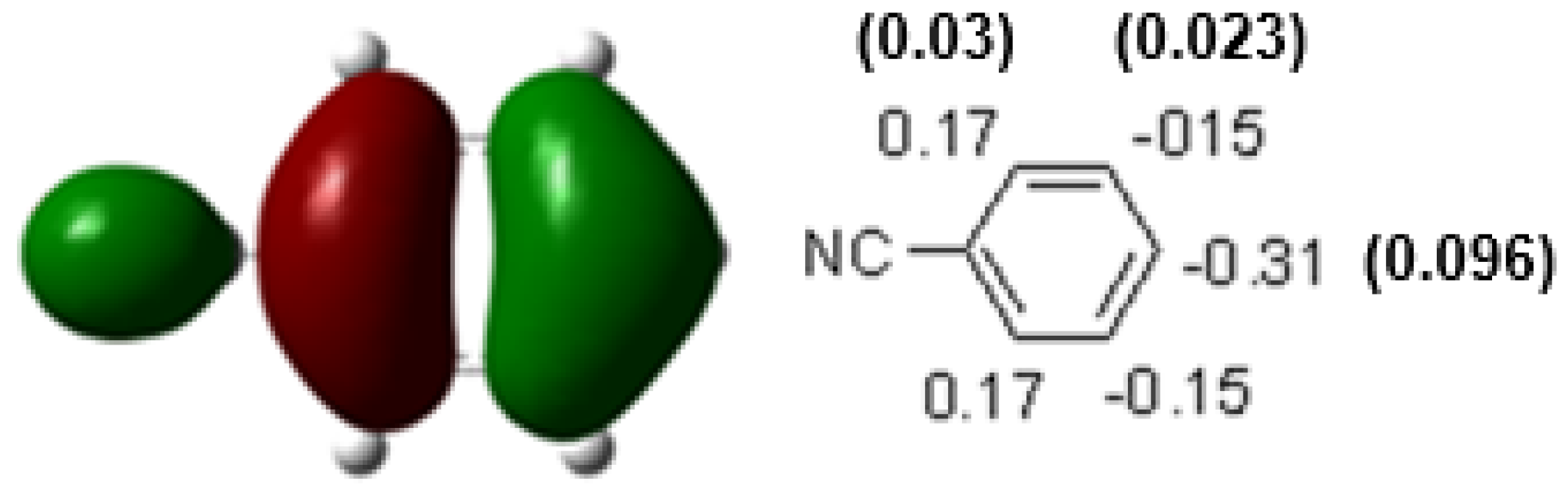

34]. The HOMO of benzonitrile has been observed at -7.59 eV (

Figure 11). These data are not in agreement with the experimental results. In fact, the HOMO favored the

ortho-para substitution. The highest atomic coefficients and the highest electronic density are in

para position.

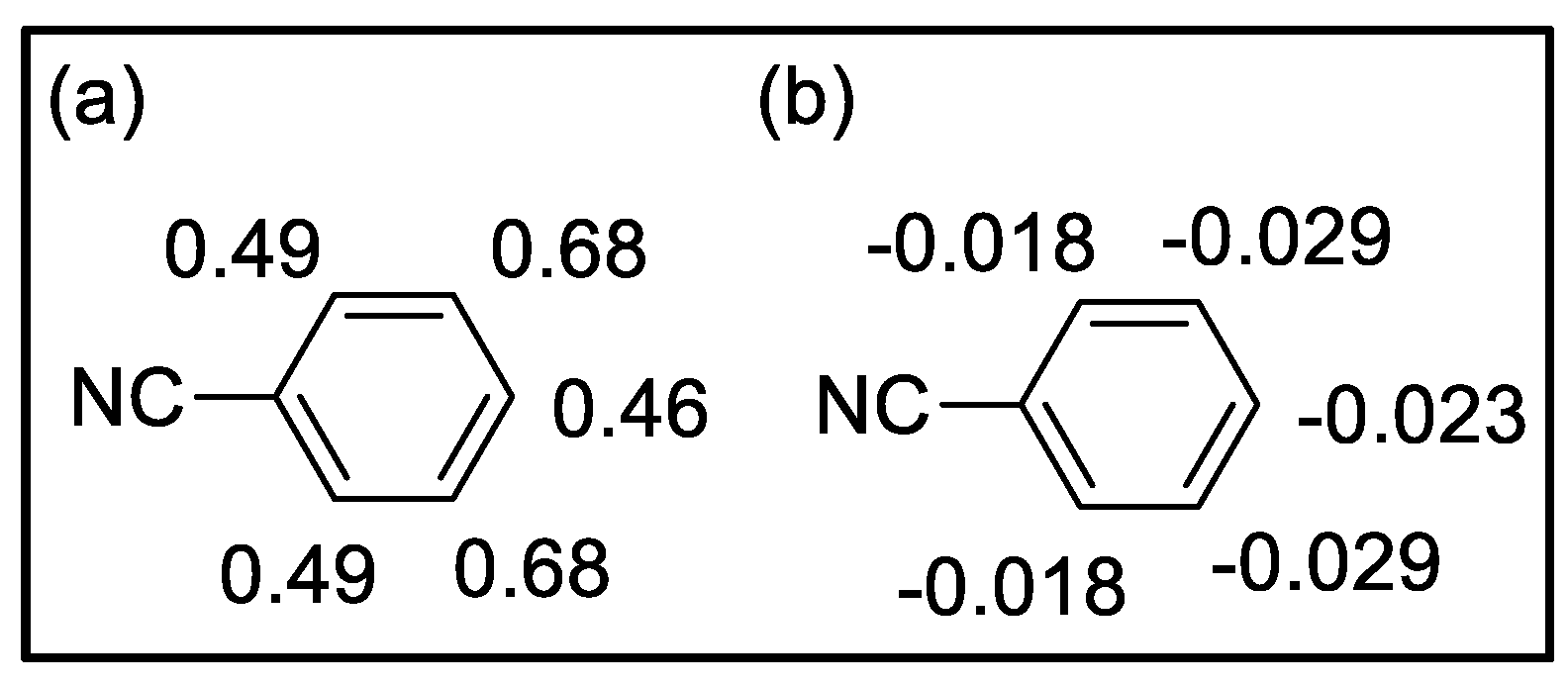

The distribution of the Mulliken charges confirms this behavior (

Figure 12a). All the carbon atoms show positive charges, and the smallest charges are in

ortho-para position. In conclusion, both frontier orbital control and charge control of the reaction cannot explain the observed behavior. On the contrary, Hirshfeld charges are in agreement with the experimental results (

Figure 12b). All the carbon atoms have negative charges and the highest charges are in

meta position. The increase of

ortho and

para substituted derivatives when chlorination was performed could be due to the contribution of the HOMO in determining the substitution sites in the reaction.

Some other deactivating

meta directing compounds have been examined. Nitration of benzaldehyde gave

m-nitrobenzaldehyde in 80% yields [

35]. Nitration of benzoic acid gave 22%

o-nitrobenzoic acid, 76%

m-nitrobenzoic acid, and 2%

p-nitrobenzoic acid [

36]. Nitration of methylbenzoate gave methyl

m-nitrobenzoate in 81% yields [

37]. Chlorination of benzoic acid gave 50%

m-chlorobenzoic acid [

38] while bromination of methyl benzoate afforded methyl

m-bromobenzoate in 85% yields [

39].

The results of calculations are reported in

Table 1. The HOMO of the benzaldehyde is a

n orbital and, then, it is not involved in the aromatic substitution. The next HOMO is a

p orbital. However, the atomic coefficients and electronic densities in

ortho and

para are the same. These data are not in agreement with the experimental results where the main reaction occurs in

meta position. Mulliken charges do not allow to have a better criterion able to explain the chemical behavior of this compound. All the carbon atoms show positive charges, and the smallest charges are in

ortho and

para position. Only Hirshfeld charges gave results that could justify the observed behavior. In fact, all the carbon atoms show negative charges, and the highest charges are in

meta position.

The HOMO of benzoic acid showed that both the highest atomic coefficients and electronic densities are in ortho and meta position. Clearly, the HOMO does not allow to justify the meta directing property of this compound. Considering Mulliken charges, all the carbon atoms show positive charges, and the smallest charges are in ortho and para position. Also Mulliken charges cannot be used to justify the orientation of benzoic acid substitution. On the contrary, Hirshfeld charges allow us to justify the observed results. In fact, all the carbon atoms show negative charges and the highest ones are in meta position, in agreement with the experimental results.

Methyl benzoate gave a HOMO where the highest atomic coefficients and electronic densities are in ortho and meta position, showing a potential chemical behavior not in agreement with the experimental results. On the contrary, both Mulliken and Hirshfeld charges are in agreement with the observed behavior. In fact, considering Mulliken charges, all the carbon atoms show positive charges, and the smallest one is in meta position. Furthermore, considering Hirshfeld charges, all the carbons atoms in the aromatic ring show negative charges, and the highest ones are in meta position.

Bromobenzene is a deactivating compound towards electrophilic substitution. However, it is

ortho-para orienting compound. Thus, nitration gave 37%

o-nitrobromobenzene, 1%

meta-nitrobromobenzene, and 62%

p-nitrobromobenzene. Chlorination gave 39%

o-chlorobromobenzene, and 61%

p-chlorobromobenzene [

34].

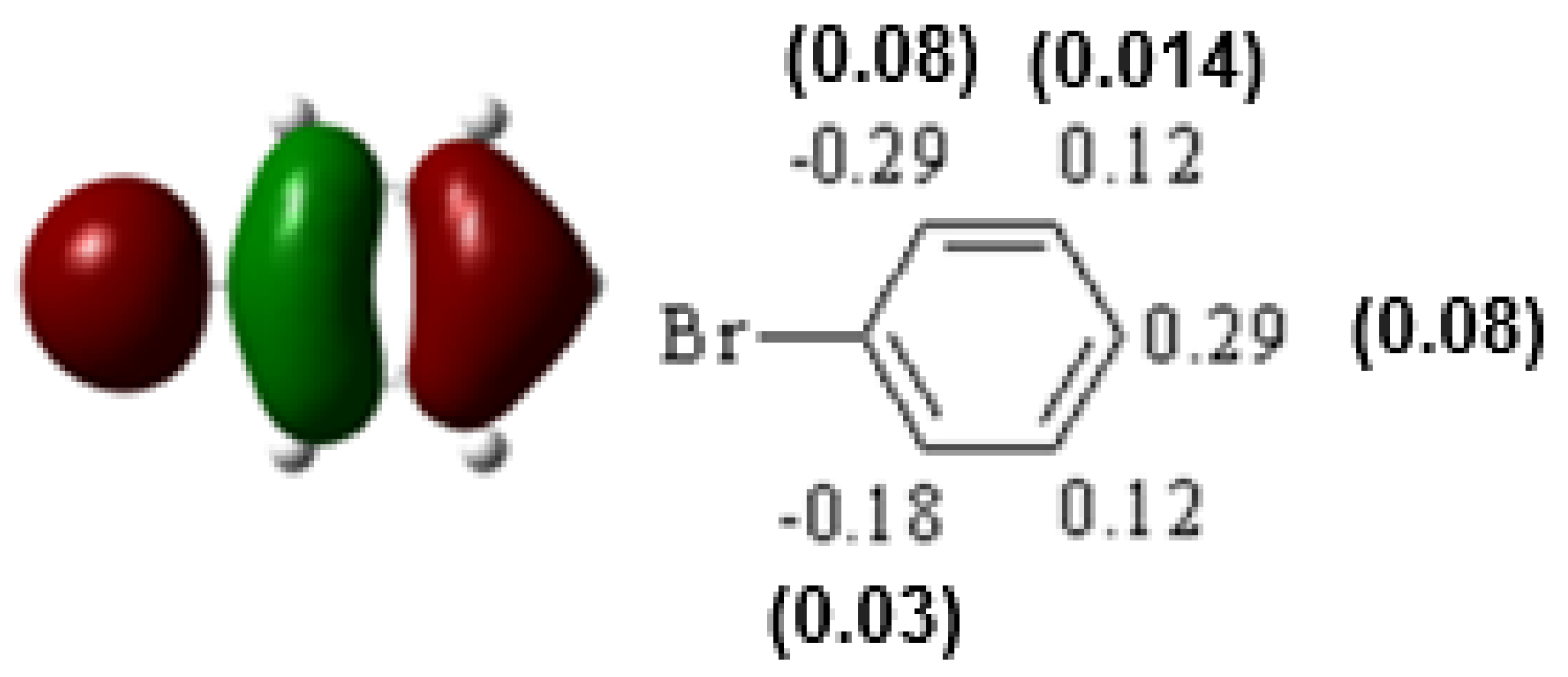

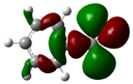

The HOMO of bromobenzene (-6.90 eV) is represented in

Figure 13. Both the atomic coefficients and electronic densities are in agreement with the formation of the

ortho-para bisubstituted compounds. In fact, highest atomic coefficients are in

ortho and

para position.

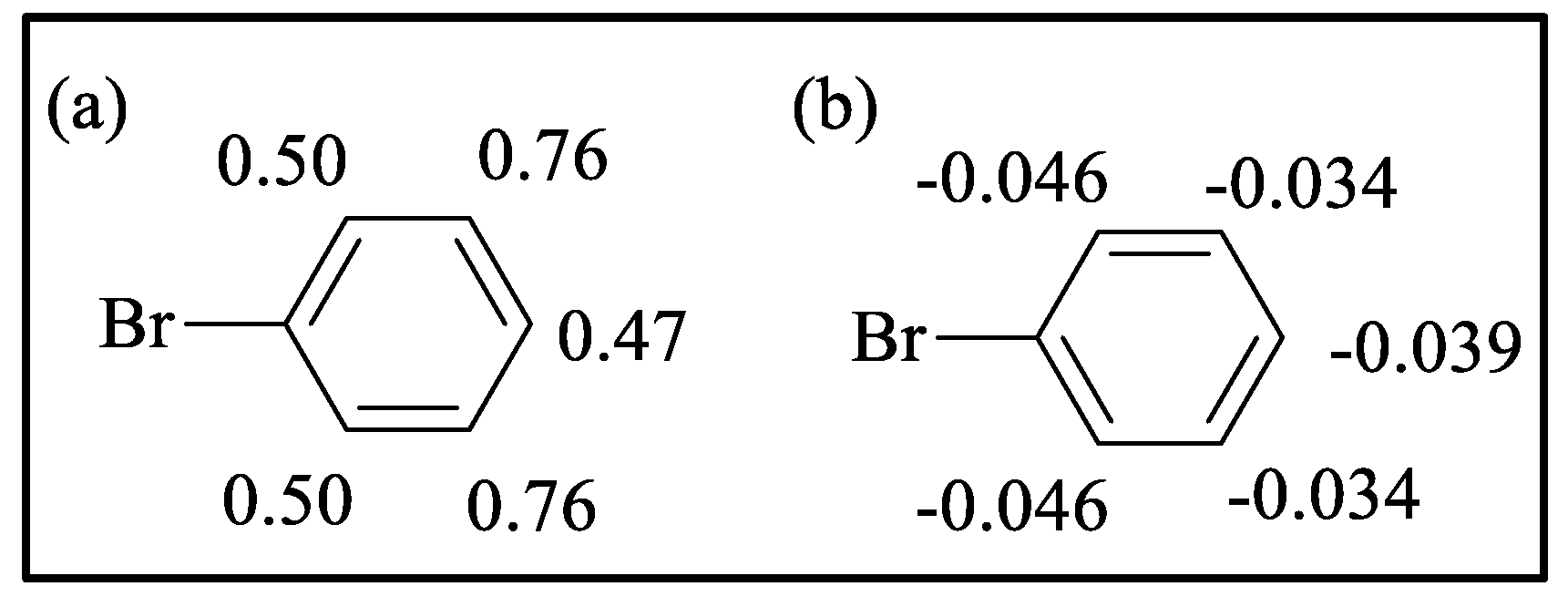

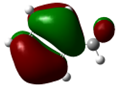

Mulliken and Hirshfeld charges in this case are in agreement with the observed behavior (

Figure 14). Considering Mulliken charges, all the carbon atoms show positive charges, and the smallest ones are in

ortho and

para position, while, considering Hirshfeld charges, all the carbon atoms show negative charges, and the highest one are in the same positions.

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Finally, we tested our approach on the basis of DFT calculations on an activating

ortho-para orienting compound, anisole. Nitration of anisole gave 44%

o-nitroanisole an 56%

p-nitroanisole. Chlorination gave 21%

o-chloroanisole and 79%

p-chloroanisole [

34].

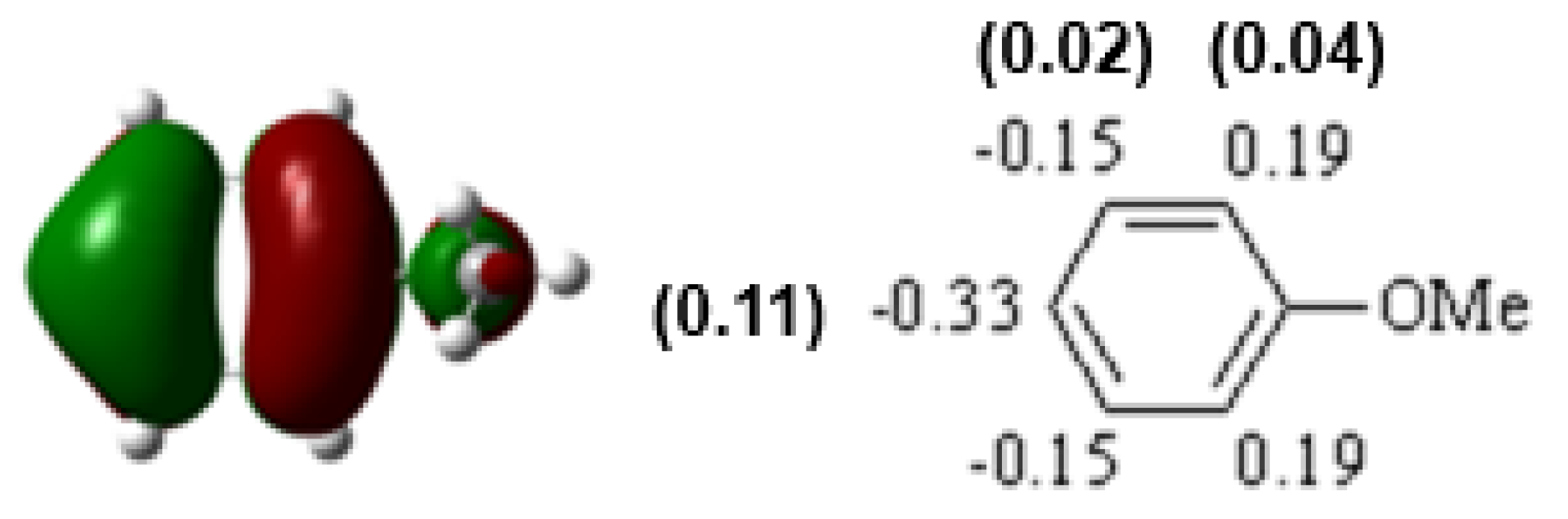

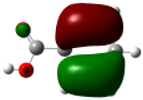

The HOMO of anisole was found at -6.92 eV (

Figure 15). The highest atomic coefficients and electronic densities are in

ortho-

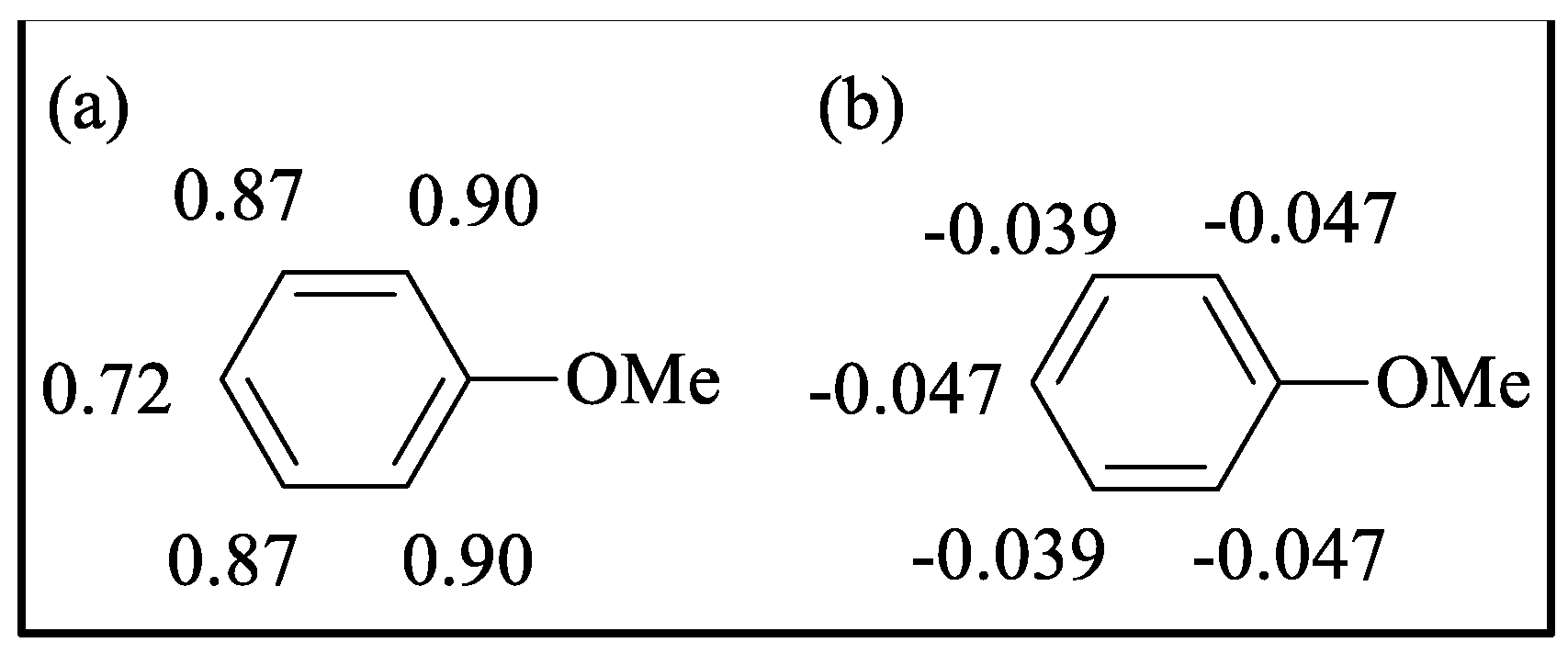

para position, in agreement with the experimental results. Mulliken charges are not in agreement with experimental behavior (

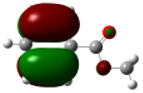

Figure 16). Considering Mulliken charges, all the carbon atoms show positive charges and the smallest is in

para. Considering Hirshfeld charges, all the carbon atoms in the aromatic ring show a negative charges, and the highest one are in

ortho-para position. Furthermore, the increase of

para isomer when chlorination had been performed clearly indicates a significant role of the HOMO in this reaction. In fact, the Hirshfeld charges are the same in

ortho and

para, while the atomic coefficient in

para position is very different from that in

ortho.

In conclusion, our analysis of the electrophilic aromatic substitution showed that, when activating, ortho-para directing or deactivating, ortho-para directing substrates are considered, the description of the reaction using Hirshfeld charges when hard electrophile (nitronium ion) is used works well. When a softer electrophile is used (chlorine) a role of the HOMO has to be considered. On the contrary, in the presence of deactivating, meta directing substrates are considered, both frontier orbital and charges approaches failed, sometimes for one factor, sometime for another.