Submitted:

17 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Patients

Establishment of Post-Operative Septic Event Diagnosis

Study Protocol

Inclusion Criteria

- I)

- Lack of microbiological evidence of SSI

- II)

- Refusal of the patient to attend the study

- III)

- Reoperation prior to postoperative day 3

- IV)

- Albumin infusion either preoperatively or within 2 postoperative days

- V)

- Known autoimmune disease under treatment or not

- VI)

- Incomplete laboratory data

- VII)

- Anemia of chronic disease

Blood Sampling

Data Collection

Control Group

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

Patient Characteristics

Establishment of Post-Operative Septic Event Diagnosis

Evaluation of the Correlation Between Patient Characteristics, Laboratory Tests and Post-Operative Septic Events

- Laboratory tests

- Multiparametric analysis

- Logistic regression analysis

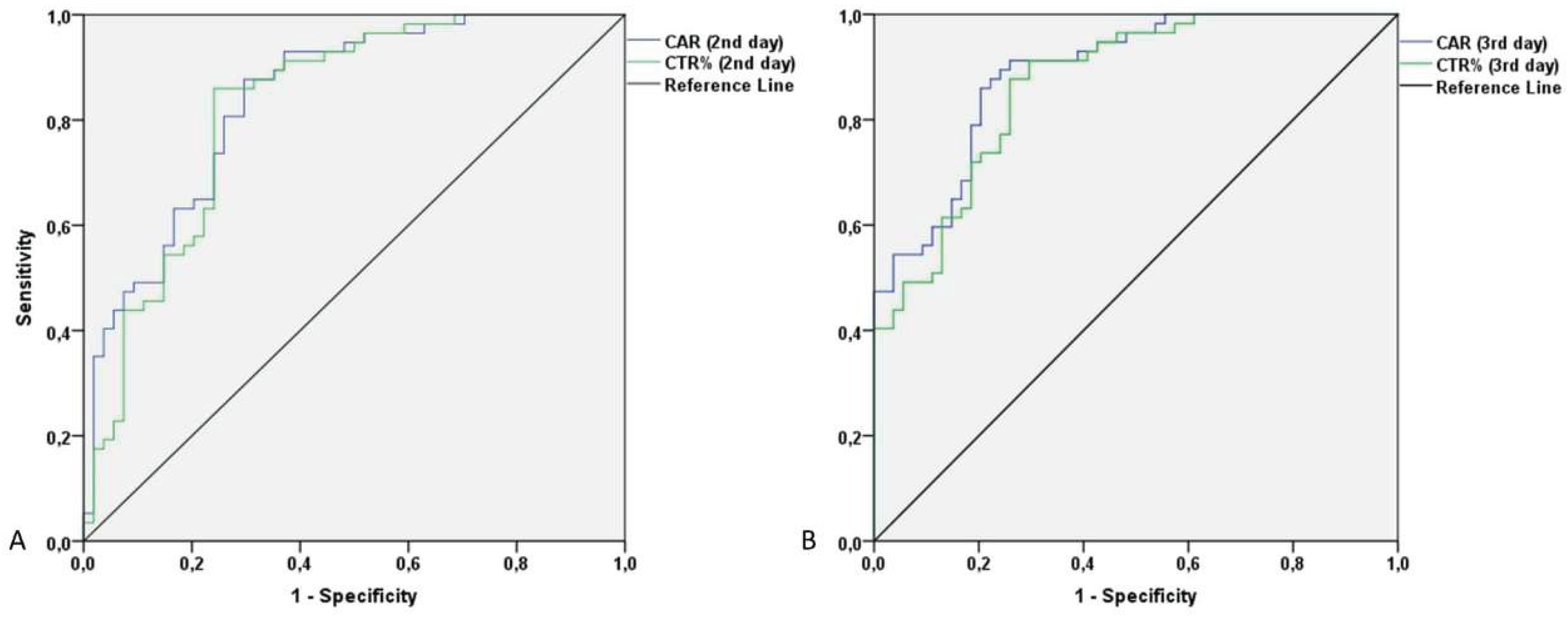

Predictive Value of CAR and CTR for Post-Operative Septic Complications

Correlation Between Examiner’s and CAR/CTR Diagnostic/Predictive Performance

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Caroff, D.A.; Chan, C.; Kleinman, K.; Calderwood, M.S.; Wolf, R.; Wick, E.C.; Platt, R.; Huang, S. Association of Open Approach vs Laparoscopic Approach With Risk of Surgical Site Infection After Colon Surgery. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, E1913570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jatoliya, H.; Pipal, R.K.; Pipal, D.K.; Biswas, P.; Pipal, V.R.; Yadav, S.; Verma, B.; Vardhan, V. Surgical Site Infections in Elective and Emergency Abdominal Surgeries: A Prospective Observational Study About Incidence, Risk Factors, Pathogens, and Antibiotic Sensitivity at a Government Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital in India. Cureus 2023, 15, e48071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Li, H.; Lv, P.; Peng, X.; Wu, C.; Ren, J.; Wang, P. Prospective multicenter study on the incidence of surgical site infection after emergency abdominal surgery in China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhangu, A.; Ademuyiwa, A.O.; Aguilera, M.L.; Alexander, P.; Al-Saqqa, S.W.; Borda-Luque, G.; Costas-Chavarri, A.; Drake, T.M.; Ntirenganya, F.; Fitzgerald, J.E.; et al. Surgical site infection after gastrointestinal surgery in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries: a prospective, international, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2018, 18, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegranzi, B.; Bischoff, P.; de Jonge, S.; Kubilay, N.Z.; Zayed, B.; Gomes, S.M.; Abbas, M.; Atema, J.J.; Gans, S.; van Rijen, M.; et al. New WHO recommendations on preoperative measures for surgical site infection prevention: an evidence-based global perspective. Lancet Infect Dis 2016, 16, e276–e287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, F.E.E.; Gans, S.L.; Solomkin, J.S.; Allegranzi, B.; Egger, M.; Dellinger, E.P.; Boermeester, M.A. Meta-analysis of lower perioperative blood glucose target levels for reduction of surgical-site infection. Br. J. Surg. 2017, 104, e95–e105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenks, P.J.; Laurent, M.; McQuarry, S.; Watkins, R. Clinical and economic burden of surgical site infection (SSI) and predicted financial consequences of elimination of SSI from an English hospital. J. Hosp. Infect. 2014, 86, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobel, R.M.; Leonhardt, M.; Förster, F.; Neumann, K.; Lobbes, L.A.; Seifarth, C.; Lee, L.D.; Schineis, C.H.W.; Kamphues, C.; Weixler, B.; et al. The impact of surgical site infection—a cost analysis. Langenbeck’s Arch. Surg. 2022, 407, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, R.; Bausch, Di. Anastomotic Leakage after Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery: Surgical Treatment. Visc. Med. 2017, 33, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telem, D.A.; Chin, E.H.; Nguyen, S.Q.; Divino, C.M. Risk factors for anastomotic leak following colorectal surgery: A case-control study. Arch. Surg. 2010, 145, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litchinko, A.; Buchs, N.; Balaphas, A.; Toso, C.; Liot, E.; Meurette, G.; Ris, F.; Meyer, J. Score prediction of anastomotic leak in colorectal surgery: a systematic review. Surg. Endosc. 2024, 38, 1723–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karliczek, A.; Harlaar, N.J.; Zeebregts, C.J.; Wiggers, T.; Baas, P.C.; van Dam, G.M. Surgeons lack predictive accuracy for anastomotic leakage in gastrointestinal surgery. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2009, 24, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klose, J.; Tarantino, I.; von Fournier, A.; Stowitzki, M.J.; Kulu, Y.; Bruckner, T.; Volz, C.; Schmidt, T.; Schneider, M.; Büchler, M.W.; et al. A Nomogram to Predict Anastomotic Leakage in Open Rectal Surgery—Hope or Hype? J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2018, 22, 1619–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenna, N.P.; Bews, K.A.; Cima, R.R.; Crowson, C.S.; Habermann, E.B. Development of a Risk Score to Predict Anastomotic Leak After Left-Sided Colectomy: Which Patients Warrant Diversion? J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2020, 24, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornmann, V.; van Ramshorst, B.; van Dieren, S.; van Geloven, N.; Boermeester, M.; Boerma, D. Early complication detection after colorectal surgery (CONDOR): study protocol for a prospective clinical diagnostic study. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2016, 31, 459–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zaher, H.A.; Ghareeb, W.M.; Fouad, A.M.; Madbouly, K.; Fathy, H.; Vedin, T.; Edelhamre, M.; Emile, S.H.; Faisal, M. Role of the triad of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and white blood cell count in the prediction of anastomotic leak following colorectal resections. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.D.W.; Kwik, C.; Shanmugalingam, A.; Allan, L.; Khoury, T. El; Pathmanathan, N.; Toh, J.W.T. C-Reactive Protein as a Predictive Marker for Anastomotic Leak Following Restorative Colorectal Surgery in an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Program. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2023, 27, 2604–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, D.E.; Peterknecht, E.; Hajibandeh, S.; Hajibandeh, S.; Torrance, A.W. C-reactive protein can predict anastomotic leak in colorectal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2021, 36, 1147–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paliogiannis, P.; Deidda, S.; Maslyankov, S.; Paycheva, T.; Farag, A.; Mashhour, A.; Misiakos, E.; Papakonstantinou, D.; Mik, M.; Losinska, J.; et al. C reactive protein to albumin ratio (CAR) as predictor of anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 38, 101621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Cao, Y.; Wang, H.; Ding, C.; Tian, H.; Zhang, X.; Gong, J.; Zhu, W.; Li, N. Diagnostic accuracy of the postoperative ratio of C-reactive protein to albumin for complications after colorectal surgery. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparreboom, C.L.; Wu, Z.; Dereci, A.; Boersema, G.S.A.; Menon, A.G.; Ji, J.; Kleinrensink, G.J.; Lange, J.F. Cytokines as early markers of colorectal anastomotic leakage: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajong, R.; Newme, K.; Nath, C.; Moirangthem, T.; Dhal, M.; Pala, S. Role of serum C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 as a predictor of intra-abdominal and surgical site infections after elective abdominal surgery. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2021, 10, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzini, A.M.; Dorizzi, R.M.; Sette, P.; Vecchi, M.; Coledan, I.; Righi, E.; Tacconelli, E. A 2020 review on the role of procalcitonin in different clinical settings: an update conducted with the tools of the Evidence Based Laboratory Medicine. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 610–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desborough, J.P. The stress response to trauma and surgery. Br. J. Anaesth. 2000, 85, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, K.; Ogawa, E.; Wada, H.; Hirata, T. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome and surgical stress in thoracic surgery. J. Crit. Care 2006, 21, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmor, M.; Hydo, L.; Barie, P.S. Relationship of Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome to Organ Dysfunction, Length of Stay, and Mortality in Critical Surgical Illness: Effect of Intensive Care Unit Resuscitation. Arch. Surg. 1999, 134, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Pantapalangkoor, P.; Tan, B.; Bruhn, K.W.; Ho, T.; Nielsen, T.; Skaar, E.P.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, R.; Wang, A.; et al. Transferrin Iron Starvation Therapy for Lethal Bacterial and Fungal Infections. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 210, 254–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claise, C.; Saleh, J.; Rezek, M.; Vaulont, S.; Peyssonnaux, C.; Edeas, M. Low transferrin levels predict heightened inflammation in patients with COVID-19: New insights. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 116, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Ginoya, S.; Tandon, P.; Gohel, T.D.; Guirguis, J.; Vallabh, H.; Jevenn, A.; Hanouneh, I. Malnutrition: laboratory markers vs nutritional assessment. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2016, 4, 272–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Giraddi, G.; Krishnan, G.; Shahi, A.K. Efficacy of Serum Prealbumin and CRP Levels as Monitoring Tools for Patients with Fascial Space Infections of Odontogenic Origin: A Clinicobiochemical Study. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2014, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogun, A.S.; Adeyinka, A. Biochemistry, Transferrin; StatPearls Publishing, 2018.

- Aisen, P.; Enns, C.; Wessling-Resnick, M. Chemistry and biology of eukaryotic iron metabolism. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2001, 33, 940–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, E.D. Iron availability and infection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj. 2009, 1790, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, K.; Uqaili, A.A.; Memon, S.; Shah, T.; Shaikh, S.N.; Memon, A.R. Association of Serum Albumin, Globulin, and Transferrin Levels in Children of Poorly Managed Celiac Disease. Biomed Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 5081303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogle, C.K.; Wesley Alexander, J.; Macmillan, B.G. The relationship of bacteremia to levels of transferrin, albumin and total serum protein in burn patients. Burns 1981, 8, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC Surgical Site Infection Event (SSI) Introduction. Natl. Healthc. Saf. Netw. 2022, 1–39.

- Macefield, R.; Blazeby, J.; Reeves, B.; Brookes, S.; Avery, K.; Rogers, C.; Woodward, M.; Welton, N.; Rooshenas, L.; Mathers, J.; et al. Validation of the Bluebelle Wound Healing Questionnaire for assessment of surgical-site infection in closed primary wounds after hospital discharge. Br. J. Surg. 2019, 106, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, A.; Clymo, J.; Dorudi, Y.; Moonesinghe, S.R.; Dorudi, S. Scoping review: The terminology used to describe major abdominal surgical procedures. World J. Surg. 2024, 48, 574–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtney, A.; Dorudi, Y.; Clymo, J.; Cosentino, D.; Cross, T.; Moonesinghe, S.R.; Dorudi, S. Novel approach to defining major abdominal surgery. Br. J. Surg. 2024, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, J.F.; Fuller, G.W.; Griffiths, B. Cohort study to characterise surgical site infections after open surgery in the UK’s National Health Service. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e076735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Collinsworth, A.; Hasa, F.; Griffin, L. Incidence and impact of surgical site infections on length of stay and cost of care for patients undergoing open procedures. Surg. Open Sci. 2023, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, M.T.; Wibe, A.; Norstein, J.; Haffner, J.; Wiig, J.N. Anastomotic leakage following routine mesorectal excision for rectal cancer in a national cohort of patients. Color. Dis. 2005, 7, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidelman, J.L.; Mantyh, C.R.; Anderson, D.J. Surgical Site Infection Prevention: A Review. JAMA 2023, 329, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicky, S.N.; Gloor, S.; Tschan, F.; Candinas, D.; Demartines, N.; Weber, M.; Beldi, G. Impact of gender on surgical site infections in abdominal surgery: A multi-center study. Br. J. Surg. 2022, 109, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghdassi, S.J.S.; Schröder, C.; Gastmeier, P. Gender-related risk factors for surgical site infections. Results from 10 years of surveillance in Germany. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2019, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offner, P.J.; Moore, E.E.; Biffl, W.L. Male gender is a risk factor for major infections after surgery. Arch. Surg. 1999, 134, 935–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagen, B.; Hall, C. Preventing Surgical Site Infections in Emergency General Surgery: Current Strategies and Recommendations. Curr. Surg. Reports 2024, 12, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellino, G.; Sciaudone, G.; Selvaggi, F.; Canonico, S. Prophylactic negative pressure wound therapy in colorectal surgery. Effects on surgical site events: current status and call to action. Updates Surg. 2015, 67, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, C.I.; Ratnayake, C.B.B.; Perrin, J.; Pandanaboyana, S. Prophylactic Negative Pressure Wound Therapy in Closed Abdominal Incisions: A Meta-analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. World J. Surg. 2019, 43, 2779–2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, K.A.; Minei, J.P.; Laronga, C.; Harbrecht, B.G.; Jensen, E.H.; Fry, D.E.; Itani, K.M.F.; Dellinger, E.P.; Ko, C.Y.; Duane, T.M. American College of Surgeons and Surgical Infection Society: Surgical Site Infection Guidelines, 2016 Update. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2017, 224, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, B.; Sartelli, M.; Coccolini, F.; Ball, C.G.; Brambillasca, P.; Chiarugi, M.; Campanile, F.C.; Nita, G.; Corbella, D.; Leppaniemi, A.; et al. Intraoperative surgical site infection control and prevention: A position paper and future addendum to WSES intra-abdominal infections guidelines. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Du, Y.; Tan, Z.; Tang, H. Association between malnutrition and surgical site wound infection among spinal surgery patients: A meta-analysis. Int. Wound J. 2023, 20, 4061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfield, R.D.; Reese, S.; Bochicchio, K.; Mazuski, J.E.; Bochicchio, G. V. Obesity and the risk for surgical site infection in abdominal surgery. In Proceedings of the American Surgeon; Vol. 82; SAGE PublicationsSage CA: Los Angeles, CA, 2016; pp. 331–336. [Google Scholar]

- Kanda, H.; Tateya, S.; Tamori, Y.; Kotani, K.; Hiasa, K.I.; Kitazawa, R.; Kitazawa, S.; Miyachi, H.; Maeda, S.; Egashira, K.; et al. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J. Clin. Invest. 2006, 116, 1494–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.A.; Favelyukis, S.; Nguyen, A.K.; Reichart, D.; Scott, P.A.; Jenn, A.; Liu-Bryan, R.; Glass, C.K.; Neels, J.G.; Olefsky, J.M. A subpopulation of macrophages infiltrates hypertrophic adipose tissue and is activated by free fatty acids via toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and JNK-dependent pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 35279–35292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauterbach, M.A.R.; Wunderlich, F.T. Macrophage function in obesity-induced inflammation and insulin resistance. Pflugers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2017, 469, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugliese, G.; Liccardi, A.; Graziadio, C.; Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Colao, A. Obesity and infectious diseases: pathophysiology and epidemiology of a double pandemic condition. Int. J. Obes. 2021 463 2022, 46, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralph, N.; Brown, L.; McKillop, K.L.; Duff, J.; Osborne, S.; Terry, V.R.; Edward, K.L.; King, R.; Barui, E. Oral nutritional supplements for preventing surgical site infections: Protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst. Rev. 2020, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucataru, A.; Balasoiu, M.; Ghenea, A.E.; Zlatian, O.M.; Vulcanescu, D.D.; Horhat, F.G.; Bagiu, I.C.; Sorop, V.B.; Sorop, M.I.; Oprisoni, A.; et al. Factors Contributing to Surgical Site Infections: A Comprehensive Systematic Review of Etiology and Risk Factors. Clin. Pract. 2024, Vol. 14, Pages 52-68 2023, 14, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, R.H.; Al-Humadi, N. Types of acute phase reactants and their importance in vaccination (Review). Biomed. Reports 2020, 12, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruys, E.; Toussaint, M.J.M.; Niewold, T.A.; Koopmans, S.J. Acute phase reaction and acute phase proteins. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. 2005, 6 B, 1045–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, S.; Kushner, I.; Samols, D. C-reactive Protein. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 48487–48490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabro, P.; Chang, D.W.; Willerson, J.T.; Yeh, E.T.H. Release of C-reactive protein in response to inflammatory cytokines by human adipocytes: linking obesity to vascular inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2005, 46, 1112–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Gautam, V.; Naseem, S. Acute-phase proteins: As diagnostic tool. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2011, 3, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pepys, M.B.; Hirschfield, G.M. C-reactive protein: a critical update. J. Clin. Invest. 2003, 111, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.L.; Jiang, B.H.; Rue, E.A.; Semenza, G.L. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995, 92, 5510–5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganz, T.; Nemeth, E. Iron Sequestration and Anemia of Inflammation. Semin. Hematol. 2009, 46, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Poll, T.; Van De Veerdonk, F.L.; Scicluna, B.P.; Netea, M.G. The immunopathology of sepsis and potential therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollier, A.; DiPersio, C.M.; Cereghini, S.; Stevens, K.; Tronche, F.; Zaret, K.; Weiss, M.C. Regulation of albumin gene expression in hepatoma cells of fetal phenotype: dominant inhibition of HNF1 function and role of ubiquitous transcription factors. Mol. Biol. Cell 1993, 4, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabay, C.; Kushner, I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 448–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlon, N.E.; Mohan, H.; Free, R.; Elbaghir, B.; Soric, I.; Fleming, C.; Balasubramanian, I.; Ivanovski, I.; Schmidt, K.; Mealy, K. Predictive value of CRP/albumin ratio in major abdominal surgery. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2020, 189, 1465–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goulart, A.; Ferreira, C.; Estrada, A.; Nogueira, F.; Martins, S.; Mesquita-Rodrigues, A.; Sousa, N.; Leão, P. Early Inflammatory Biomarkers as Predictive Factors for Freedom from Infection after Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Prospective Cohort Study. Surg. Infect. (Larchmt). 2018, 19, 446–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Study | ||||||||

| Prospective | Retrospective | Total | p | |||||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||||

| Sex | Female | 48 (55.8%) | 38 (44.2%) | 86 (43%) | 0.938 | |||

| Male | 63 (55.3%) | 51 (44.7%) | 114 (57%) | |||||

| Age groups | <= 40 | 8 (66.7%) | 4 (33.3%) | 12 (6%) | 0.685 | |||

| 41 - 50 | 8 (53.3%) | 7 (46.7%) | 15 (7.5%) | |||||

| 51 - 60 | 17 (58.6%) | 12 (41.4%) | 29 (14.5%) | |||||

| 61 - 70 | 38 (61.3%) | 24 (38.7%) | 62 (31%) | |||||

| 71 - 80 | 27 (49.1%) | 28 (50.9%) | 55 (27.5%) | |||||

| 81+ | 13 (48.1%) | 14 (51.9%) | 27 (13.5%) | |||||

| Elective Operation | Yes | 62 (60%) | 40 (39.2%) | 102 (51%) | 0.125 | |||

| No | 49 (40%) | 49 (60.8%) | 98 (49%) | |||||

| Post-Operative complications | No | 54 (48.6%) | 27 (30.3%) | 81 (40.5%) | 0,002 | |||

| 1 | 34 (30.6%) | 37 (41.6%) | 71 (35.5%) | |||||

| 2 | 10 (9%) | 21 (23.6%) | 31 (15.5%) | |||||

| 3 | 9 (8.1%) | 4 (4.5%) | 13 (6.5%) | |||||

| 4 | 4 (3.6%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (2%) | |||||

| Wound Infection | No | 54 (48.6%) | 27 (30.3%) | 81 (40.5%) | 0,009 | |||

| Yes | 57 (51.4%) | 62 (69.7%) | 119 (59.5%) | |||||

| Wound dehiscence | No | 92 (82.9%) | 72 (80.9%) | 164 (82%) | 0,717 | |||

| Yes | 19 (17.1%) | 17 (19.1%) | 36 (18%) | |||||

| Intrabdominal Abscess | No | 99 (89.2%) | 77 (86.5%) | 176 (88%) | 0,563 | |||

| Yes | 12 (10.8%) | 12 (13.5%) | 24 (12%) | |||||

| Anastomotic /stump Leak | No | 64 (85.9%) | 61 (100%) | 125 (95.4%) | 0,006 | |||

| Yes | 9 (14.1%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (4.6%) | |||||

| Re-operation | No | 109 (98.2%) | 83 (93.3%) | 192 (96%) | 0,076 | |||

| Yes | 2 (1.8%) | 6 (6.7%) | 8 (4%) | |||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| Age | 63.9 | 15 | 66.6 | 14.6 | 65.1 | 14.8 | 0.204 | |

| BMI | 27 | 3.8 | 27.5 | 3.6 | 27.2 | 3.7 | 0.399 | |

| Length of Stay (Days) | 8.9 | 4.7 | 13.9 | 8.0 | 11.1 | 6.8 | <0.001 | |

| Laboratory Test | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | df1. df2 | F | p | ||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| WBCs (10^3) | Total | 11.8 | 4.5 | 10.9 | 3.9 | 9.7 | 3.3 | 2. 588 | 24.28 | <0.001 |

| N/I | 11.9 | 4.4 | 10.7 | 3.9 | 9.5 | 3. | 3. 585 | 0.86 | 0.461 | |

| Inf | 11.7 | 4.5 | 11 | 4 | 9.9 | 3.4 | ||||

| CRP (mg/dl) | Total | 11.55 | 8.33 | 17.53 | 8.92 | 16.47 | 8.42 | 2. 398 | 66.73 | <0.001 |

| N/I | 7.99 | 6.06 | 11.76 | 7.24 | 10.76 | 6.01 | 2. 396 | 7.24 | 0.001 | |

| Inf | 13.98 | 8.79 | 21.46 | 7.75 | 20.35 | 7.59 | ||||

| Alb (g/dl) | Total | 3.3 | 0.5 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 3.1 | 0.4 | 2. 398 | 99.66 | <0.001 |

| N/I | 3.5 | 0.4 | 3.4 | 0.4 | 3.3 | 0.3 | 2. 396 | 3.13 | 0.052 | |

| Inf | 3.2 | 0.5 | 3.0 | 0.4 | 2.9 | 0.4 | ||||

| Transferrin (mg/dl) | Total | 171.5 | 44.8 | 158.6 | 41.2 | 150.9 | 37.7 | 2. 220 | 76.11 | <0.001 |

| N/I | 182.8 | 43.7 | 172.7 | 41.9 | 163.0 | 37.2 | 2. 218 | 76.05 | 0.272 | |

| Inf | 160.7 | 43.5 | 145.3 | 36.2 | 139.4 | 34.7 | ||||

| CRP/ Alb | Total | 3.7 | 3.0 | 5.8 | 3.2 | 5.6 | 3.1 | 2. 398 | 72.19 | <0.001 |

| N/I | 2.4 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 2.3 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 2. 396 | 10.97 | <0.001 | |

| Inf | 4.6 | 3.2 | 7.3 | 2.9 | 7.1 | 2.9 | ||||

| CRP/ Trans | Total | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 2. 220 | 39.36 | <0.001 |

| N/I | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 2. 218 | 15.12 | <0.001 | |

| Inf | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.07 | ||||

| Post-Operative complications | ||||

| Parameter | No | Yes | p | |

| N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Sex | Female | 44 (54.3%) | 42 (35.3%) | 0.008 |

| Male | 37 (45.7%) | 77 (64.7%) | ||

| Type of Study | Prospective | 54 (66.7%) | 57 (47.9%) | 0.009 |

| Retrospective | 27 (33.3%) | 62 (52.1%) | ||

| Elective Operation | No | 52 (64.2%) | 46 (38.7%) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 29 (35.8%) | 73 (61.3%) | ||

| Age (years) | <= 40 | 5 (6.2%) | 7 (5.9%) | 0.343 |

| 41 - 50 | 3 (3.7%) | 12 (10.1%) | ||

| 51 - 60 | 10 (12.3%) | 19 (16.0%) | ||

| 61 - 70 | 25 (30.9%) | 37 (31.1%) | ||

| 71 - 80 | 23 (28.4%) | 32 (26.9%) | ||

| 81+ | 15 (18.5%) | 12 (10.1%) | ||

| Hypertension | No | 35 (43.2%) | 50 (42.0%) | 0.867 |

| Yes | 46 (56.8%) | 69 (58.0%) | ||

| Diabetes Type II | No | 61 (75.3%) | 86 (72.3%) | 0.633 |

| Yes | 20 (24.7%) | 33 (27.7%) | ||

| COPD | No | 67 (82.7%) | 97 (81.5%) | 0.828 |

| Yes | 14 (17.3%) | 22 (18.5%) | ||

| Chronic Renal Disease | No | 75 (92.6%) | 106 (89.1%) | 0.405 |

| Yes | 6 (7.4%) | 13 (10.9%) | ||

| Cancer | No | 40 (49.4%) | 58 (48.7%) | 0.929 |

| Yes | 41 (50.6%) | 61 (51.3%) | ||

| Metastatic Cancer | No | 75 (92.6%) | 111 (93.3%) | 0.952 |

| Yes | 6 (7.4%) | 8 (6.7%) | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Age (years) | 67.16 (14.61) | 63.76 (14.86) | 0.092 | |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 26.98 (3.4) | 27.37 (3.89) | <0.001 | |

| Post Op CRP D2 | 11.76 (7.24) | 21.46 (7.75) | <0.001 | |

| Post Op Alb D2 | 3.37 (0.36) | 3 (0.41) | <0.001 | |

| Post Op WBCs D2 | 10.54 (3.86) | 10.99 (3.97) | 0.351 | |

| CAR DAY 2 | 3.59 (2.32) | 7.31 (2.89) | <0.001 | |

| CTR DAY 2 | 0.08 (0.06) | 0.15 (0.07) | <0.001 | |

| CTR DAY2 x100 | 7.56 (6.01) | 14.92 (6.96) | <0.001 | |

| Parameter | OR | 95%LL | 95%UL | p |

| Age (years) | 0.98 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.166 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 0.90 | 0.79 | 1.02 | 0.101 |

| Female Sex | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0.68 | 0.008 |

| Elective Operation | 0.86 | 0.29 | 2.54 | 0.781 |

| Hypertension | 1,07 | 0,45 | 2,54 | 0,870 |

| Diabetes Type II | 1,52 | 0,61 | 3,78 | 0,372 |

| COPD | 1,20 | 0,37 | 3,91 | 0,764 |

| Chronic Renal Disease | 0,99 | 0,19 | 5,25 | 0,992 |

| Presence of Cancer | 1,70 | 0,69 | 4,21 | 0,251 |

| Post Op TRF D2 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 0.137 |

| Post Op Alb D2 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.002 |

| CTR DAY 2 x 100 | 1.23 | 1.10 | 1.39 | 0.000 |

| CTR DAY 3 x 100 | 1,40 | 1,21 | 1,61 | <0,001 |

| CAR DAY 2 | 1.73 | 1.32 | 2.29 | <0.001 |

| CAR DAY 3 | 2,02 | 1,63 | 2,51 | 0,000 |

| FORWARD | OR | 95%LL | 95%UL | p |

| Female Sex | 0.26 | 0.09 | 0.71 | 0.009 |

| Post Op Alb D2 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.52 | 0.005 |

| CTR DAY 2 x 100 | 1.18 | 1.07 | 1.29 | <0.001 |

| CTR DAY 3 x 100 | 1,42 | 1,24 | 1,63 | <0,001 |

| CAR DAY 2 | 1.68 | 1.31 | 2.17 | <0.001 |

| CAR DAY 3 | 2,02 | 1,65 | 2,48 | <0,001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).