1. Introduction

Olive trees, the most ancient cultivated trees globally, are currently cultivated on a large scale, involving approximately 9 million hectares worldwide [

1]. According to data from the International Olive Council (IOC) [

2] during the 2023–2024 agricultural campaign, global olive oil production remained heavily concentrated in Mediterranean regions, which collectively accounted for the vast majority of global output with Spain maintaining its position as the leading producer with an estimated 766,400 tons, despite ongoing climatic pressures that have affected yields (

Table 1). The second most important producer was Italy with approximately 288,900 tons, reflecting the country's sustained production capacity driven by a combination of traditional practices and high-value cultivars (

Table 1). Turkey, Greece, and Tunisia also contributed significantly, with outputs of 210,000 tons, 195,000 tons, and 200,000 tons respectively. Portugal was the 6th main producer with a reported production of 150,000 tons, higher than the 126,000 tons of 2022-2023 campaign [

2]. This figure reinforces Portugal’s growing significance in the global olive oil sector, attributed to substantial investments in super-intensive cultivation systems, modernization of milling infrastructure, and adherence to high-quality production standards. These factors have not only increased volume but have also elevated the international profile of Portuguese olive oils, especially in export markets.

The expansion of the olive oil industry has led to an increase in its environmental footprint, including aspects such as energy and water usage, greenhouse gas emissions, and waste generation. Amongst the various waste products, olive leaves emerge as the primary contributor, being a plentiful byproduct resulting from the pruning of olive trees during oil production [

1] The production yield of olive leaves from pruning amounts to approximately 25 kg per olive tree, with an additional 5% of the weight of the harvested olives gathered at the oil mill [

3]. Addicionally, olive trees crown have to be pruned annually or at least every two years [

4] which produces significant amounts of olive wastes that include both olive leaves and olive branches. Velázquez-Martí et al. [

5] reported no significant differences in residual biomass between annual and biennial pruning, with an average of 33 kg of leftover biomass per tree. Their study was made in Mediterranean region with emphasis in Spain, Italy and Greece and they found that olive pruning typically produces an average of 1.31 t/ha with annual pruning and 3.02 t/ha with biennial pruning. Avraamides and Fatta [

6] reported that for every liter of olive oil produced, approximately 6.23 kilograms of pruning residues, consisting of branches and leaves, are generated.

The chemical composition of olive leaves exhibits variability on various factors such as origin, the ratio of branches present on the sample, storage conditions, climatic elements, moisture levels, and the extent of contamination with soil and oils [

7]. On the other hand, the chemical composition of olive branches depends mainly on the bark to wood ratio.

The extractive content of olive leaves varies significantly among cultivars, as evidenced by the differences in both aqueous and ethanolic extractive yields reported before for Mediterranean cultivars, Arbequina, Royal, and Picual, where Picual exhibited the highest total extractive content (45.07 ± 1.49%), which was significantly greater than that of Arbequina (40.76 ± 0.79%) and Royal (40.56 ± 0.27%), indicating a richer chemical profile in this variety [

8]. These results suggest cultivar-dependent variations in metabolite composition and polarity, which may have implications for their bioactivity and potential applications in phytochemical or pharmacological research [

8]. In accordance to Espeso et al [

9] olive leaves are a rich source of bioactive compounds, many of which are unique to the

Olea europaea species. Among these, polyphenolic compounds such as oleuropeosides (oleuropein and verbascoside), various flavones (including luteolin-7-glucoside, apigenin-7-glucoside, and diosmetin-7-glucoside), flavonols (e.g., rutin), flavan-3-ols, and catechin-substituted phenolics (such as tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol, vanillin, vanillic acid, and caffeic acid) are of particular interest [

9]. Oleuropein is the major secoiridoid glycoside found in olive leaves, reaching up to 24.5% of the leaf dry weight, compared to 14% in unripe olive fruits [

9,

10]. Secoiridoids are molecules that belong to the class of secondary metabolites with both terpenoid and hydroxy-aromatic characteristics, and their structures are defined by elenolic acid and its related derivatives[

11]. Similar results were presented by Khelouf et al. [

12] that studied eight different Tunisian and Algerian cultivars and oleuropein was the most significant compound found in extracts. Oleuropein possesses a high antioxidant activity that has been partly attributable to its metal-chelating properties, particularly with copper (Cu) and iron (Fe) ions, which are known to catalyze free radical-generating reactions [

9,

13]. The prominent presence of oleuropein highlights its significance as a marker compound in olive leaf extract and as a potential therapeutic agent due to its antioxidative, antimicrobial, and antiviral properties [

9,

14]. Other phenolic compounds, such as hydroxytyrosol and verbascoside are also present in high amounts [

12] while smaller amounts of other compounds like epigallocatechin, epicatechin-3-O-gallate, tyrosol, myricetin, catechol, and chlorogenic, sinapic, ferulic, and ellagic acids are also found [

12]. The composition and concentration of polyphenols in olive leaves are influenced by several variables. Technological factors associated with the extraction process, such as the type and composition of the solvent, solid-to-solvent ratio, particle size of the plant material, extraction temperature and pH, and extraction duration can significantly affect the yield and profile of the extracted compounds. Agronomic variables, including leaf age, degree of ripeness, geographic origin, cultivation methods, and the phenological stage at sampling, also play a crucial role in determining the final polyphenolic content [

9,

15]. Changes in polyphenolic composition during leaf maturation have also been reported. Specifically, the concentration of oleuropein decreases with leaf aging, while levels of hydroxytyrosol increase due to ongoing chemical and enzymatic transformations [

9,

16]. This dynamic shift in compound abundance is essential to consider when selecting raw material as it can influence both the extract’s potency and its intended use. These compounds are not only important for plant defense against abiotic stressors such as UV radiation and biotic threats like insect herbivory, but they also hold significant potential for human health applications due to their pharmacological properties. Olive leaves (OL) contain moderate levels of structural carbohydrates, with cellulose at 12.0% and hemicellulose at 10.5% [

17]. OL also have a relatively high protein content of 6.9%, supporting its role in the plant’s metabolic and nutritional processes [

17]. The lignin content is also significant, with 15.1% insoluble lignin, and around 2% soluble, indicating some degree of structural rigidity [

17].

There is not much information about the chemical composition of small branches alone since most of the studies include pruning (a mixture of leaves and small branches), wood or bark. Gullón et al. [

17] presented the chemical analysis of olive tree pruning (OTP) and olive leaves (OL) and reported differences in their composition, reflecting their distinct structural and functional roles in the tree. OTP exhibited a higher proportion of structural carbohydrates, with notably greater cellulose (21.6%) and hemicellulose (14.5%) contents compared to OL (12.0% and 10.5%, respectively). In contrast, OL shows a much higher content of total extractives (41.9%) than OTP (28.6%), particularly ethanol-soluble extractives (14.8% in OL vs. 5.1% in OTP), which suggests a richer presence of secondary metabolites like waxes, oils, and other lipophilic compounds typically associated with leaf tissue [

17]. Both materials contain similar levels of phenolics, indicating potential antioxidant activity in both fractions. Moreover, OL is characterized by a higher ash content (6.9% vs. 3.9%). Protein content is also significantly greater in OL (6.9%) than in OTP (3.1%), further supporting the nutritional and metabolic function of leaves. Insoluble lignin content is comparable between OTP (15.4%) and OL (15.1%), though slightly higher in OTP, aligning with its woody nature.

Polyalcohol liquefaction has proven to be an efficient method to convert solid lignocellulosic materials into a usable liquid, particularly for the production of polymer precursors. One of the first attempts to liquefy wood at moderate temperatures was made by Seth [

18] that tested several simple and polyhydric alcohols such as methanol, ethanol, propanol, ethylene glycol, glycerol, phenol and catechol with temperatures of 170ºC and 250ºC and concluded that catechol, phenol and ethylene glycol were the most efficient in solubilizing wood under acidic conditions. Acid catalysis have shown to be more efficient in liquefaction except for barks with high suberin content where basic catalysis is preferred [

19]. In subsequent studies other polyalcohol’s such as polyethylene glycol (PEG) were tested [

20], but this PEG-based liquefaction system yielded 10–30% solid residues even under optimal reaction parameters, attributed to insufficient hydroxyl group content that facilitated re-condensation reactions of liquefied wood (LW) intermediates. However, incorporation of 10 wt% glycerol into the PEG matrix effectively minimized the formation of unconverted residues. Therefore, co-solvent mixtures with glycerol have been proven to be the best option for the liquefaction of most of the lignocellulosic materials like wood [

21], kenaf [

22], cork [

19], bagasse and cotton stalks [

23], orange peel wastes [

24] and walnut shells [

25].

The objective of this study is to compare the chemical composition and liquefaction behavior of olive leaves (OL) and olive branches (OB) in order to evaluate their potential for valorization. By examining differences in ash, extractives, structural carbohydrates, lignin content, and liquefaction performance under varying operational parameters (temperature, reaction time, particle size, and material/solvent ratio), the study aims to identify optimal processing conditions and highlight distinct advantages of each by-product for bio-based applications such as biofuels, biocomposites, or nutrient recovery.

3. Results

The chemical composition of olive branches (OB) and olive leaves (OL) reveals distinct differences that reflect their functional roles within the plant. The ash content is higher in leaves (4.08%) compared to branches (2.79%), suggesting that leaves accumulate a greater proportion of inorganic minerals. Similar results were presented before for several energy crops such as four perennial (

Miscanthus sinensis X Giganteus Greef & Deuter, Arundo donax L., Cynara cardunculus L. and

Panicum virgatum L.) and two annual

(sweet and fibre sorghum, Sorghum bicolor Moench) [

33], where ash contents were in some cases, as for example,

Arundo donax almost four times higher (113 g/kg in leaves against 32 g/kg in stems). The extractive fractions obtained with dichloromethane, ethanol, and hot water, are also considerably higher in leaves (5.80%, 20.11%, and 15.82%, respectively) than in branches (1.22%, 11.24%, and 10.00%). These elevated values in leaves indicate a richer presence of non-structural, potentially bioactive compounds, which are often associated with secondary metabolism and defense mechanisms. Similar results of total extractives (43.73%) were presented before for olive leaves from different cultivars with Picual exhibiting the highest total extractive content (45.07 ± 1.49%), greater than that of Arbequina (40.76 ± 0.79%) and Royal (40.56 ± 0.27%) [

8]. Picual's aqueous extractives (29.46%) and ethanolic extractives (15.61%) were significantly greater than those of Arbequina and Royal, indicating cultivar-specific differences in the distribution and composition of bioactive compounds in olive leaves. The different values in ethanol and water extractives obtained here can be due to the previous extraction with dichloromethane followed by ethanol while in the study by Lama-Muñoz et al. [

8] it was made with water followed by ethanol. Similar results were presented for Tunisian and Algerian varieties where ethanol extractives ranged from 12.02 to 26.61 [

12]. Smaller amounts of extractives (25.5%) have been reported for olive leaves (from Chemlali variety) collected in the region of Sfax (center of Tunisia) [

34].

Structural carbohydrate analysis shows the contrasting compositions. Olive branches exhibit a substantially higher α-cellulose content (30.47%) and hemicellulose fraction (27.88%) compared to leaves (18.56% and 14.00%, respectively). The α-cellulose and hemicellulose content obtained was higher than the reported before with 5.7% for cellulose and 3.8% hemicelluloses [

35]. Nevertheless, these values were estimations using the anhydro correction of sugars determined by GC. Another study [

17] reported for olive tree pruning, composed largely of woody branches, 21.6% cellulose and 14.5% hemicellulose while for leaves it was 12.0% and 10.5% respectively. Mabrouk et al. [

34] reported higher values of polysaccharides with 37% hemicelluloses and 12.4% cellulose for olive leaves harvested in Tunisia. While the absolute values differ between studies, likely due to variations in sampling and analytical methods, the trend remains consistent: branch-derived biomass contains more structural polysaccharides than leaves. A similar work was presented before for different olive tree residues such as olive leaves, small branches(as in this study) and big branches [

36]. Olive leaves contained slightly lower amounts of cellulose (11%) compared to the 18% obtained here, but very similar hemicellulose content (14.73% vs. 14.00%), while OB showed a slightly higher cellulose content (39% vs. 31%) and slightly lower hemicellulose levels (24% vs. 28% obtained here).

Klason lignin was higher in leaves (21.64%) than in branches (16.40%), implying that leaves may require additional rigidity or protection against biotic and abiotic stress factors. Similarly in the work by Alshammari et al. [

36] OL had a higher lignin content (16.33%) than OB (13.26%). Gullón et al. [

17] reported lignin content (acid-insoluble plus acid-soluble) relatively similar between olive tree pruning (17.7%) and leaves (17.1%) which is slightly lower than the obtained here. Similar results were presented before by Mabrouk et al. [

34] with 17% lignin for olive leaves of the Chemlali variety. However, Mateo et al. [

37] reported lignin values of 25.9% for olive leaves which is higher than the obtained here. These differences have important implications for valorization pathways: branch-based materials are better suited for applications requiring high structural carbohydrate content (e.g., biofuels, biocomposites), while leaf biomass may offer advantages for extracting bioactive compounds and nutrients.

The ash content, which reflects the inorganic mineral composition of biomass, consistently appears higher in olive leaves compared to woody fractions. In the present study, olive leaves (OL) show a significantly higher ash content (4.08%) than olive branches at 2.79%, supporting the idea that leaves accumulate more inorganic nutrients. This trend is also evident in earlier data, where olive leaves had an ash content of 6.9% compared to just 3.9% in olive pruning [

17]. Even higher values were presented for the Chemlali variety with 7% ash content [

34]. Although the absolute values differ, the relative relationship remains consistent across both studies. This elevated mineral content in leaves further supports their role in nutrient transport and storage and suggests their potential utility in applications where mineral-rich biomass is desirable, such as soil amendments or as feedstock for nutrient recovery processes. On the other hand, the high amount of ashes in leaves makes them inappropriate for pellets production.

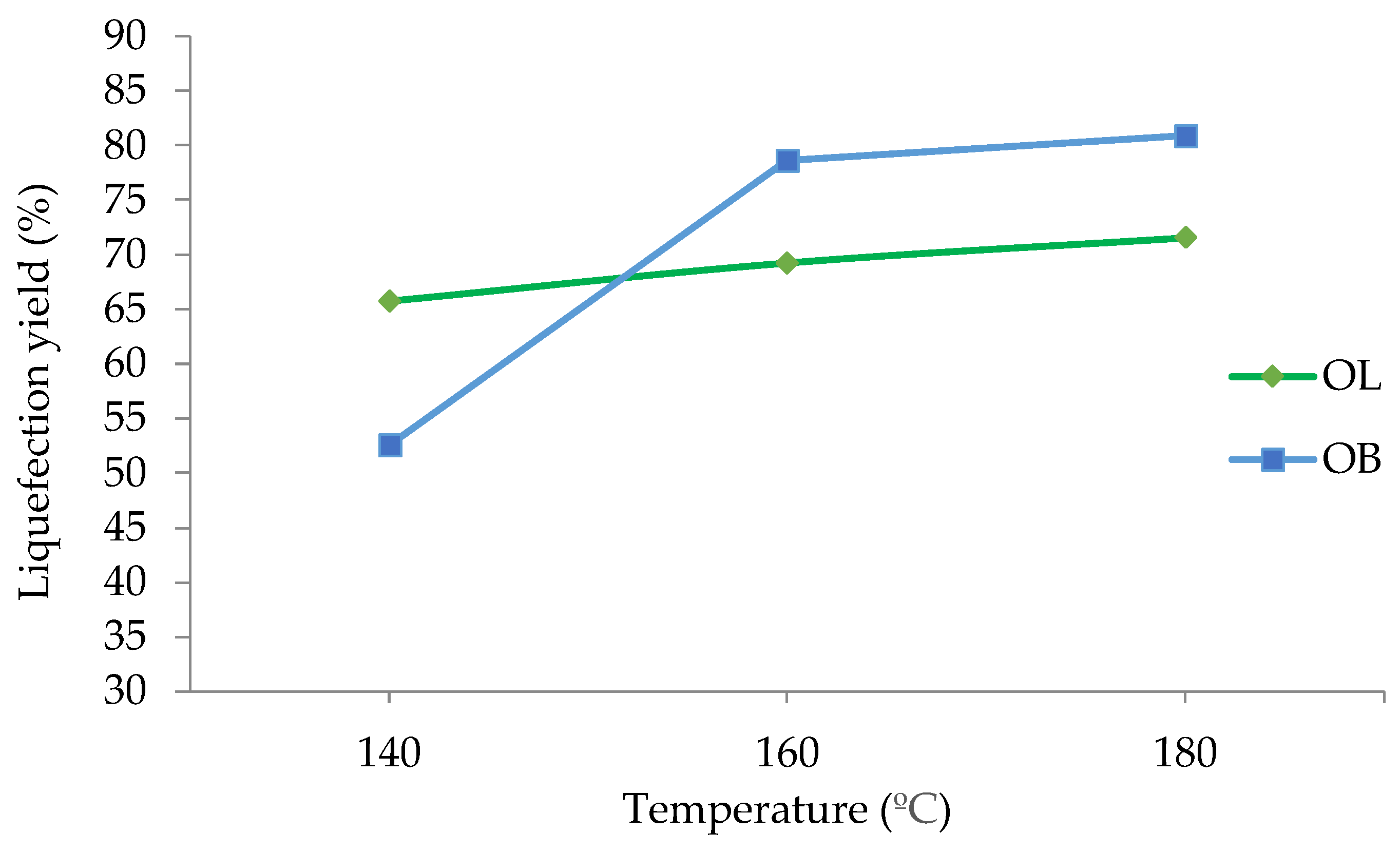

The results presented in

Figure 1 indicate the effect of temperature on the liquefaction percentages of the two olive tree by-products, olive leaves (OL) and olive branches (OB). The data reveals a clear trend whereby increasing the temperature from 140°C to 180°C leads to higher liquefaction percentages for both materials. Similar results were presented before for different lignocellulosic materials such as corncob [

38], wheat straw [

39], cork [

19,

40] or wood [

41]. Nevertheless, in some cases the liquefaction percentage decreases for higher temperatures due to condensation reactions as for example in the liquefaction of

Eucalyptus pellita [

42] or cork [

43].

At 140°C, olive leaves exhibit a liquefaction percentage of 66%, while olive branches are noticeably lower at 52.5%. As the temperature increases to 160°C, olive tree leaves rise to 69%, whereas olive branches show a marked increase to 78.6%. At 180°C, olive leaves reached 72%, and olive branches further increased to 80.9%.

These results suggest that temperature exerts a critical influence on liquefaction, likely by decreasing viscosity which is very important since glycerol and ethylene glycol are very viscous, and by facilitating molecular mobility helping the breakdown process of the complex structure of biomass. Notably, olive branches undergo a more pronounced change between 140°C and 160°C, where their liquefaction percentage increases by approximately 26%. Beyond 160°C, the rate of increase diminishes, implying the existence of a threshold temperature at which the most significant structural breakdown occurs. By contrast, the liquefaction of olive leaves follows a more gradual trend, indicating a comparatively stable response to thermal processing.

The distinct behaviors of olive leaves and olive branches can be attributed to differences in their compositional and structural properties. Olive branches contain a higher percentage of structural components (74.7%) against (54.2%), which could explain the steeper rise in liquefaction under higher temperatures. From a practical standpoint, these findings suggest that temperatures above 160°C deliver weakening yields in liquefaction efficiency for olive branches, highlighting a potential temperature range where energy input is optimized relative to liquefaction output.

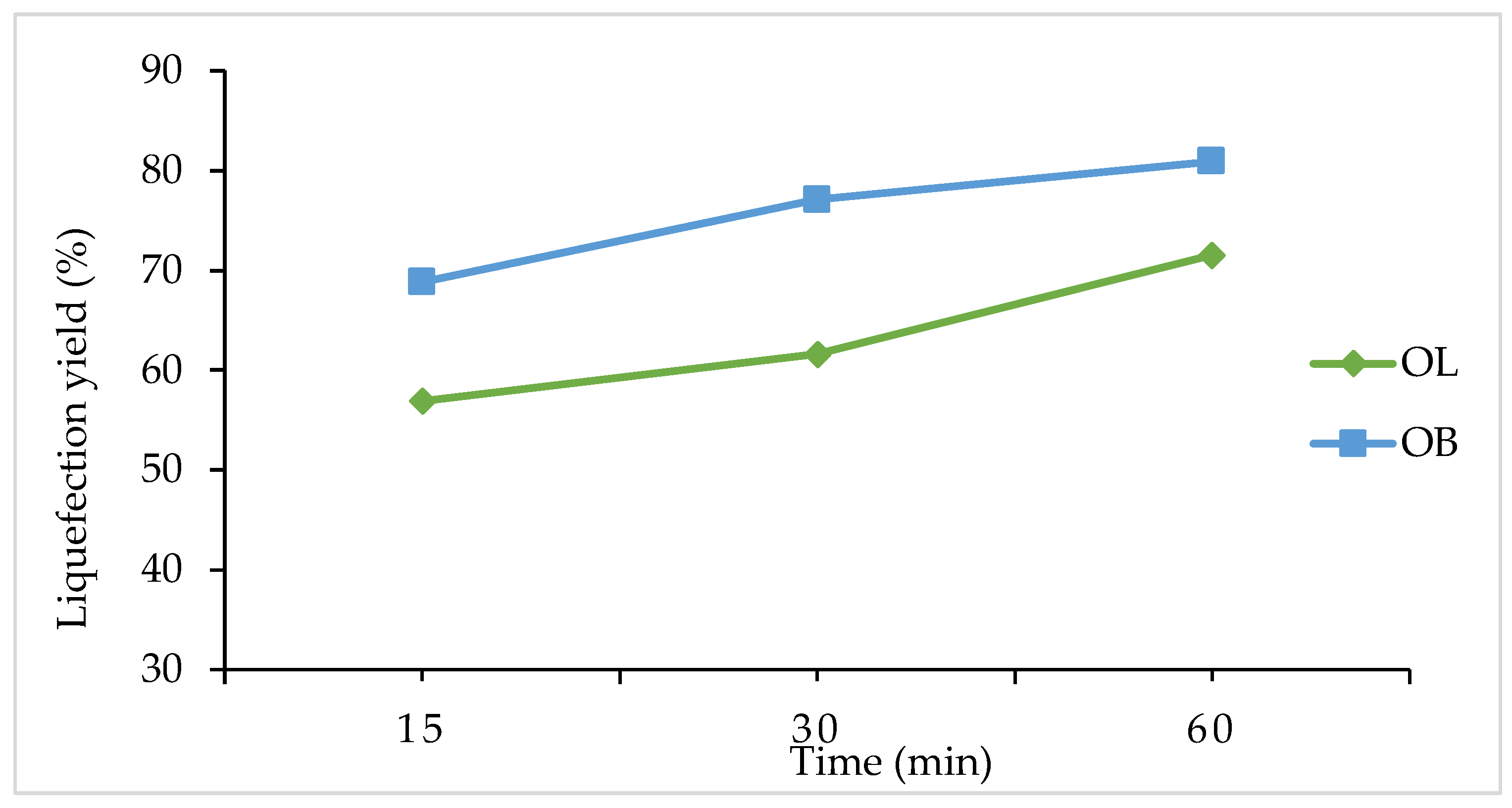

Figure 2 shows the impact of varying reaction times on the liquefaction percentages of olive leaves (OL) and olive branches (OB). At 15 minutes, OL exhibits a liquefaction percentage of 57%, while OB is higher at 68.8%. As the reaction proceeds to 30 minutes, OL increases to 62%, whereas OB shows a more pronounced rise to 77. 1%. Extending the reaction time to 60 minutes leads to a further increase for both materials, with OL reaching 72% and OB reaching 80.9%.

These findings indicate that prolonging the reaction time enhances liquefaction for both olive leaves and olive branches. Although OL demonstrates a steady upward trend, OB consistently maintains higher liquefaction values, indicating a faster or more complete breakdown under the same reaction times. These results underscore the importance of optimizing reaction time to balance energy inputs against the degree of liquefaction desired, particularly when working with different olive by-products.

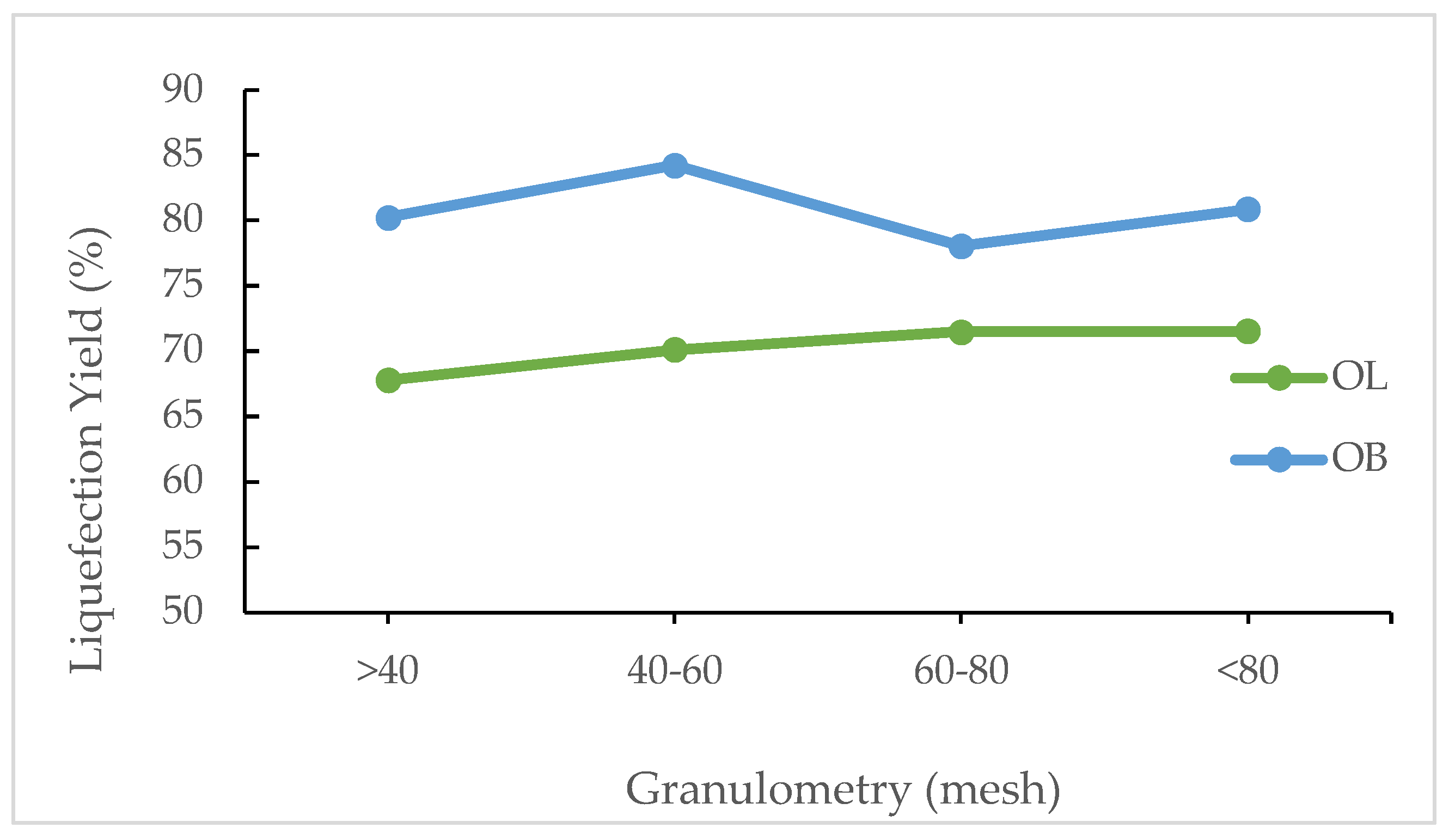

Figure 3 presents liquefaction percentages for olive leaves (OL) and olive branches (OB) as a function of particle size ranges, with categories defined as >40, 40–60, 60–80, and <80. In general, olive branches exhibit higher liquefaction values compared to olive leaves across all granulometries. For OB, the highest liquefaction is observed in the 40–60 fraction, reaching 84.253%, while the lowest is in the 60–80 range at 78.071%. Conversely, olive leaves show a more gradual increase in liquefaction with finer particle sizes, rising from 68% in the >40 category to 70% in the 40–60 range, and reaching a plateau of 72% for both the 60–80 and <80 fractions.

These results suggest that particle size plays a significant role in the liquefaction process and that generally higher liquefaction could be achieved with smaller particles. The higher performance of olive branches in the 40–60 fraction in relation to smaller particles can be due to a different chemical composition between the fractions since one might contain higher bark content than the other. Different chemical composition across granulometry was already reported for different materials [

44,

45,

46]. This difference could be due to variations in lignocellulosic content or other compositional factors between the two materials. Overall, the data emphasize that controlling granulometry is crucial for optimizing liquefaction, especially when processing olive branches, where the particle size distribution markedly influences the efficiency of the conversion process

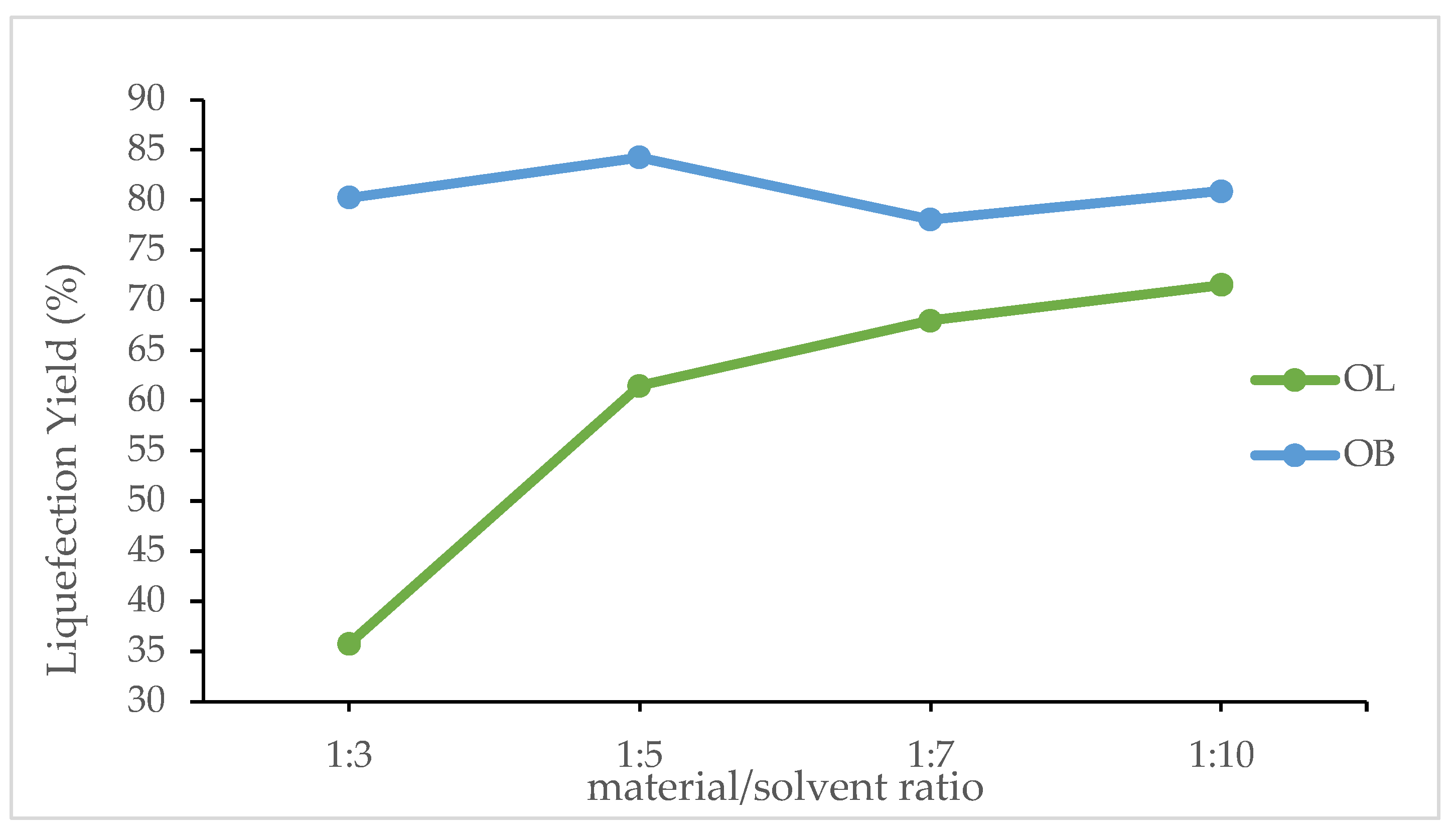

Figure 4 shows the effect of the material/solvent ratio on the liquefaction percentages of olive leaves (OL) and olive branches (OB). For olive leaves, the liquefaction percentage starts at a relatively low value of 36% at a 1:3 ratio and increases progressively to 61% at 1:5, 68% at 1:7, and finally reaching 72% at a 1:10 ratio. This steady improvement suggests that an increased amount of solvent relative to the material significantly enhances the breakdown of olive leaves, possibly by facilitating better heat transfer and more efficient solvation of the compounds responsible for the liquefaction process.

In contrast, olive branches show a different trend. At a 1:3 ratio, the liquefaction percentage is already high at 80.2%, and it reaches its maximum of 84. 3% at a 1:5 ratio. However, there is a slight decrease to 78. 1% at a 1:7 ratio, followed by a recovery to 80.9% at a 1:10 ratio. This pattern indicates that olive branches are less sensitive to changes in the material/solvent ratio than olive leaves, likely due to differences in their chemical composition and structural properties. The optimal solvent ratio for olive branches appears to be around 1:5, where the liquefaction is maximized, suggesting that beyond this point, additional solvent does not significantly improve, and may even slightly hinder, the conversion process.

These results emphasize the importance of tailoring the material/solvent ratio to the specific characteristics of feedstock. For olive leaves, increasing the solvent proportion leads to a marked enhancement in liquefaction, which may be attributed to improved penetration of the solvent into the leaf matrix and more effective reaction kinetics. For olive branches, the process seems to reach an optimum more quickly and further increases in solvent do not yield a proportional improvement in liquefaction efficiency. Understanding these differences is critical for optimizing processing conditions and achieving the most efficient conversion of these olive by-products.

The results obtained from varying operational parameters, temperature, reaction time, granulometry, and material/solvent ratio, offer a comprehensive view of the liquefaction behavior of two olive by-products: olive leaves (OL) and olive branches (OB).

An increase in temperature from 140°C to 180°C positively affects the liquefaction process for both materials. Olive leaves display a gradual improvement, with liquefaction rising from 66% at 140°C to 72% at 180°C. In contrast, olive branches respond more markedly to temperature changes; starting at 52.5% at 140°C, their liquefaction significantly increases to 80.9% at 180°C. This suggests that olive branches may be more susceptible to thermally induced structural breakdown, potentially due to differences in their lignocellulosic composition. Although the difference is slight, olive leaves have shown to exhibit a crystallinity of 64.1%, lower than the 65.4% observed in olive stems [

36]. The slightly higher crystalline structure in OB makes it generally more resistant to chemical and enzymatic degradation under mild conditions. However, under elevated temperatures, these crystalline regions break down rapidly once a critical threshold is reached. This behavior aligns with the observed sharp increase in liquefaction for OB at higher temperatures, suggesting that once sufficient thermal energy disrupts the crystalline domains, structural degradation accelerates significantly.

Reaction time is another critical factor influencing the conversion process. For olive leaves, extending the reaction from 15 to 60 minutes results in an increase in liquefaction from 57% to 72%. Olive branches also show improvement with longer reaction times, achieving liquefaction levels of 68.8% at 15 minutes and reaching 80.9% at 60 minutes. Notably, olive branches tend to reach high conversion levels faster, which may be attributed to their inherent material properties that favor quicker degradation under thermal conditions.

The effect of particle size, as assessed by granulometry, further highlights the distinct responses of the two materials. Olive leaves exhibit a modest increase in liquefaction with finer particles, rising from 68% for particles larger than 40 mesh to 72% for both the 60–80 and finer fractions. Olive branches, however, show an optimal response in the 40–60 mesh range, achieving a maximum liquefaction of 84.3%, while a slight decrease is observed with further reduction in particle size. This behavior indicates that an intermediate particle size may provide the best balance between available surface area and structural integrity for the efficient liquefaction of olive branches.

The material/solvent ratio also plays a pivotal role in the liquefaction process. For olive leaves, an increase in the solvent proportion from a 1:3 to a 1:10 ratio enhances liquefaction dramatically from 36% to 72%. This improvement likely results from better solvent penetration and more efficient interaction with the reactive components of the leaves. Conversely, olive branches achieve relatively high liquefaction even at a lower solvent ratio, starting at 80.2% for a 1:3 ratio and peaking at 84.3% for a 1:5 ratio. Further increases in the solvent ratio do not significantly improve the performance for olive branches, suggesting that their optimal liquefaction can be attained under less solvent-intensive conditions.

Overall, these integrated results demonstrate that the optimal liquefaction conditions are highly dependent on the specific characteristics of the feedstock. Olive branches, with their more rapid response to temperature and lower solvent requirements, contrast with olive leaves, which benefit from longer reaction times and higher solvent ratios. The interplay between temperature, time, particle size, and solvent availability underscores the need for tailored process optimization to maximize conversion efficiency in the liquefaction of diverse olive by-products.

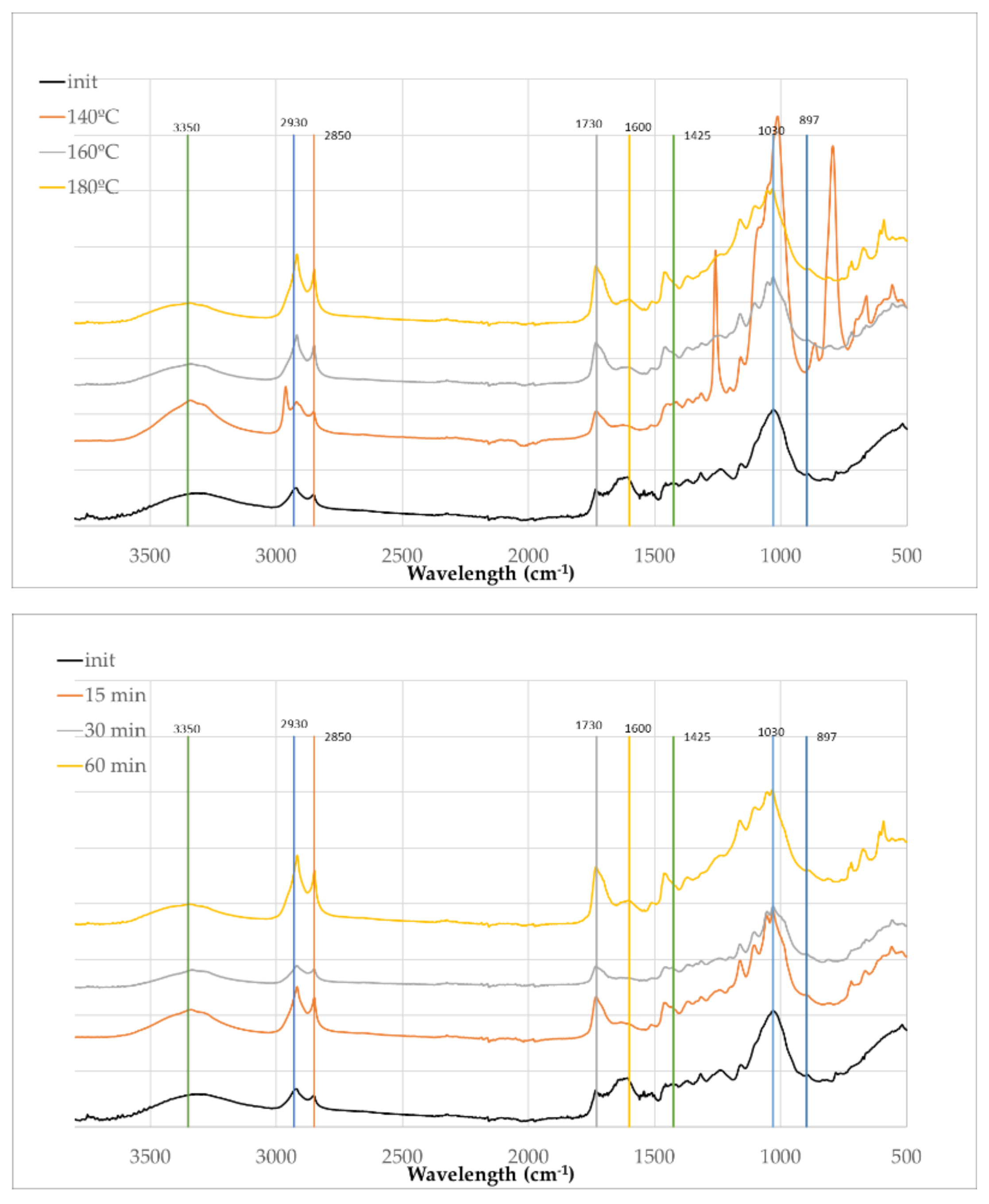

The FTIR spectra of the solid residues obtained after liquefaction of OB for 60 min at increasing temperatures (140°C, 160°C, and 180°C) and liquefied at 180ºC with different times (15, 30 and 60 min), respectively are presented in

Figure 5.

The FTIR spectra of the initial olive branches and the residues obtained from polyalcohol liquefaction under varying temperatures and reaction times reveal significant chemical transformations indicative of progressive biomass breakdown. The initial sample displays characteristic absorption bands associated with lignocellulosic materials, including broad O–H stretching near 3350 cm⁻¹, C–H stretching vibrations around 2930 cm⁻¹ and 2850 cm⁻¹, and distinct bands at 1730 cm⁻¹, 1600 cm⁻¹, and 1425 cm⁻¹ corresponding to carbonyl and aromatic skeletal vibrations typically associated with lignin and hemicelluloses. In relation to O-H stretching band there are no consistent changes with temperature, with an increase for 140ºC and a decrease afterwards which can be due to some unreacted solvents (glycerol and ethylene-glycol) present in the solid residue. As temperature and reaction time increase, the intensities of the peaks at 2930 cm⁻¹ and 2850 cm⁻¹ become progressively stronger, indicating the incorporation or generation of aliphatic chains, likely due to the presence of polyalcohols and the fragmentation of the biomass into more reduced, saturated compounds [

47]. This is consistent with the known behavior of glycerol and ethylene glycol under acidic or thermal conditions, where they can participate in transesterification or esterification reactions and contribute to the formation of new C–H bonds [

48]. Simultaneously, the carbonyl band at 1730 cm⁻¹ becomes more prominent with both temperature and time, suggesting the formation of esters and other oxygenated degradation products, possibly through oxidative cleavage of hemicellulose or lignin side chains. This increase has been reported before for example the residues in the polyalcohol liquefaction of Lodgepole Pine bark [

49]. In contrast, the band at 1600 cm⁻¹, attributed to aromatic C=C stretching in lignin, diminishes steadily, pointing to the degradation or transformation of the aromatic backbone of lignin.

In the fingerprint region (1300–1030 cm⁻¹), a general increase in absorbance is observed, particularly with longer reaction times and higher temperatures. This region is mostly associated with C–O stretching vibrations in glycosidic linkages in cellulose and hemicellulose or aliphatic alcohols such as ethylene glycol and glycerol [

50] and therefore supports the increasing presence of alcohols, ethers, and esters. These signals are consistent with the contribution of glycerol and ethylene glycol as reactants and carriers of hydroxyl functionalities. In accordance to Kobayashi et al. [

51] the bands at 1100–1200 cm⁻¹ are originated from the liquefaction solvent, indicating that it was incorporated into the residue.

Overall, the spectral evolution indicates that the solid residue is not unreacted material but rather undergoes extensive chemical modification during liquefaction. One peculiar observation arises at the reaction condition of 140°C, that shows a strong absorption at 1030 cm

-1 and where three additional peaks at 2960 cm

-1, 1240 cm⁻¹ and 793 cm⁻¹ are evident but not observed in other spectra at higher temperatures or longer reaction durations. These peaks may represent intermediate compounds formed during the early stages of lignin or hemicellulose degradation, possibly phenolic ethers or substituted aromatic rings that are unstable and further react under more severe conditions. While contamination cannot be completely excluded, the disappearance of these bands under more advanced reaction conditions suggests they are more likely associated with incomplete reactions rather than external impurities. Another factor supporting this conclusion is the liquefaction percentage shown in

Figure 1, which clearly indicates that the liquefaction percentage of olive branches is significantly lower than that of olive leaves at 140ºC.

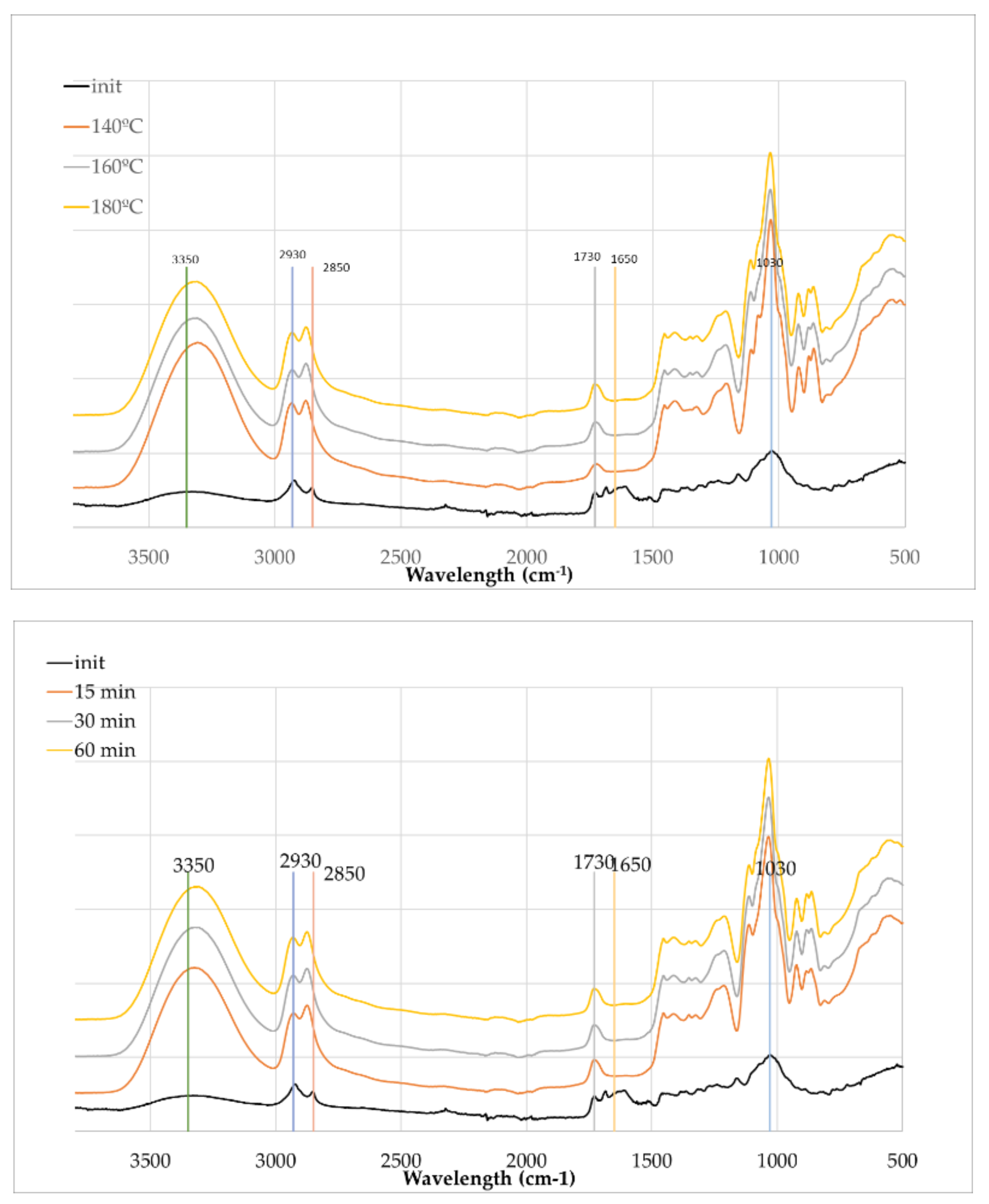

Figure 6 presents the initial olive branches and the liquefied materials at different temperatures and liquefaction times. It is important to consider that the initial material is in solid form, while the liquefied samples are primarily liquid. As a result, the initial spectrum displays lower absorption intensities, which is a known characteristic of FTIR-ATR when comparing solids to liquids due to differences in contact efficiency and penetration depth at the ATR crystal interface as stated before [

52].

In

Figure 6 (left), which examines the influence of temperature after 60 minutes of reaction time, a progressive change in spectral features is observed with increasing temperature (140°C, 160°C, and 180°C). One of the most notable transformations is the broad O–H stretching band centered around 3320 cm⁻¹ for the liquefied material and 3350 cm

-1 for the initial material, which becomes significantly more intense in liquefied material. This enhancement is attributed not only to the improved signal due to the liquid state but also to the cleavage of ether and ester bonds in the biomass matrix, leading to the release or formation of additional hydroxyl-containing species such as alcohols and polyols from glycerol and partially degraded lignocellulosic fragments.

The aliphatic C–H stretching bands near 2930 cm⁻¹ and 2870 cm⁻¹ (2850 in initial material) show slight shifts and increased intensity, indicating the accumulation of alkyl fragments resulting from the breakdown of lignin and other aliphatic components of the biomass. This effect becomes more pronounced at 180°C, suggesting more extensive degradation. At around 1730 cm⁻¹, the sharpening of the carbonyl peak is evident with increasing temperature, pointing to the formation of esters, aldehydes, or carboxylic acids, likely products of cellulose and hemicellulose oxidation and esterification reactions. According to Kobayashi et al. [

51] this increase can be attributed to levulinic acid produced from the degradation of cellulose that has a strong absorption around 1724 cm

-1.

Near 1600 cm⁻¹, the spectra display changes indicative of aromatic ring vibrations. These changes suggest partial degradation or chemical transformation of lignin structures. The peak around 1030 cm⁻¹ becomes more intense in liquefied material, consistent with the generation of C–O stretching vibrations from alcohols, ethers, and esters formed during the liquefaction process.

Meanwhile, the peak near 897 cm⁻¹, commonly associated with β-glycosidic linkages in cellulose seems to reduce significantly as temperature increases. This reduction is a clear indication of cellulose depolymerization, which is a central aspect of the liquefaction process. At the same time, the appearance of new peaks at 861 cm⁻¹, 883 cm⁻¹, and 923 cm⁻¹ in the FTIR spectra of liquefied olive branches suggests the formation of new chemical structures during the liquefaction process. These bands fall within the 900–850 cm⁻¹ region, which is commonly associated with C–H out-of-plane bending vibrations in substituted alkenes, aromatic compounds, and carbohydrate-derived structures. Particularly the peak at around 923 cm⁻¹ is often associated with C–O stretching and C–C stretching in aliphatic ethers or sugar ring breathing modes in structures derived from cellulose degradation products like levoglucosan or oligomeric carbohydrates. A strong absorption on 923 cm

-1 was found for on the FTIR spectrum of water-insoluble pyrolytic cellulose from cellulose pyrolysis oil [

53]. On the other hand this peak at 923 cm

-1 has also been attributed to the C–H in-plane benching of aromatic compounds [

54]. The peak at 860.4 cm

-1 has been attributed before to hydroxyacetaldehyde from cellulose thermal degradation [

55]

Figure 6 (right) focuses on the effect of reaction time at a constant temperature of 180°C. Over time (15, 30, and 60 minutes), similar trends are observed. The O–H stretching band near 3350 cm⁻¹ intensifies, reflecting the ongoing breakdown of biomass and formation of hydroxylated species. Likewise, the C–H stretching bands around 2930 cm

-1 and 2850 cm⁻¹ become more defined, supporting the notion of increasing aliphatic content from degradation products. The carbonyl band at 1730 cm⁻¹ also strengthens with time of liquefaction similarly to temperature. The 1030 cm⁻¹ band continues to grow in intensity with prolonged reaction time, reinforcing the accumulation of oxygenated functionalities. As in the temperature study, the 897 cm⁻¹ cellulose peak decreases and several peaks appear in this region, confirming time-dependent cellulose degradation.

Overall, the spectral evolution in both sets of experiments demonstrates the effectiveness of acid-catalyzed liquefaction in transforming solid biomass into a more reactive, oxygenated liquid phase.

In the FTIR-ATR spectra of liquefied lignocellulosic materials, several peaks are shifted such as the O–H stretching band shifting from 3350 cm⁻¹ to 3320 cm⁻¹ and the C–H stretching band shifting from 2850 cm⁻¹ to 2870 cm⁻¹, which are indicative of changes in the chemical environment and molecular interactions resulting from the liquefaction process. The shift of the O–H stretching band from 3350 to 3320 cm⁻¹ suggests an increase in hydrogen bonding. In the initial solid material, O–H groups may be engaged in relatively weak hydrogen bonds or remain partially free. After liquefaction, due to depolymerization, exposure of internal hydroxyl groups, or the formation of polyol-rich structures, the number and strength of hydrogen bonds often increase. Stronger hydrogen bonding leads to a red shift (lower wavenumber) in the O–H stretching vibration, as the bond becomes longer and weaker due to greater interaction with adjacent electronegative atoms [

56]. The shift of the C–H stretching band from 2850 to 2870 cm⁻¹, in contrast, is a blue shift (to higher wavenumber). This can result from a change in the chemical environment of aliphatic –CH₂– or –CH₃ groups. During liquefaction, the decomposition of biopolymers and formation of new, shorter-chain aliphatic compounds or branched structures can reduce steric hindrance or electron-withdrawing effects, making the C–H bonds vibrate at slightly higher frequencies. In some cases, this may also reflect phase changes (e.g., from crystalline to amorphous) or interactions with newly formed polar groups, which alter the electron density around the C–H bonds.

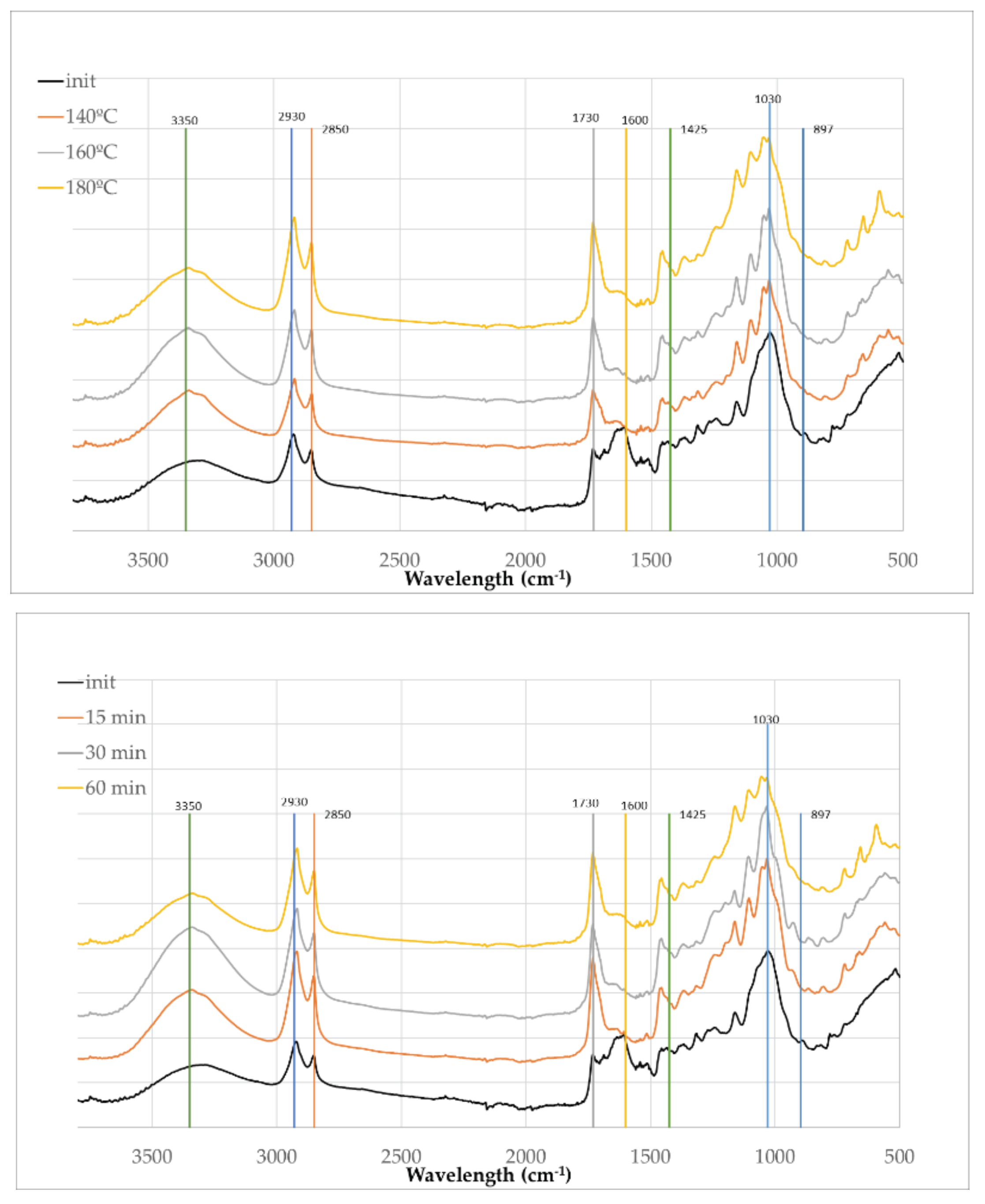

The FTIR-ATR spectra of olive leaves and the solid residues after acid-catalyzed liquefaction at varying temperatures (140°C, 160°C, and 180°C for 60 minutes) and times (15 min, 30 min and 60 min at 180ºC) (

Figure 7) reveal significant structural and compositional changes, many of which resemble those observed for olive branches, yet with notable differences reflective of the distinct biochemical makeup of leaves. The FTIR spectrum of initial olive leaves is like olive branches with a higher absorption at 2930 cm

-1, possible due to the large amount of extractives and weaker absorptions at 1030 cm

-1 which is probably due to the lower amount of polysaccharides (

Table 2).

The FTIR spectra reveals significant chemical changes in olive leaves after liquefaction with polyalcohols at increasing temperatures and times, similarly to olive branches. The broad O–H stretch around 3350 cm⁻¹ intensifies, indicating the formation or exposure of hydroxyl groups. Enhanced C–H stretching bands at 2930 and 2850 cm⁻¹ suggest increased aliphatic content. A sharp C=O peak at 1730 cm⁻¹ appears in liquefied samples, especially at 160°C and 180°C, reflecting degradation of polysacharides and formation of carbonyl-rich compounds. Aromatic ring vibrations at 1600 cm⁻¹ diminish, pointing to lignin modification, while the weakening of peaks at 1030 cm⁻¹ and 897 cm⁻¹ confirms extensive breakdown of cellulose and hemicellulose.

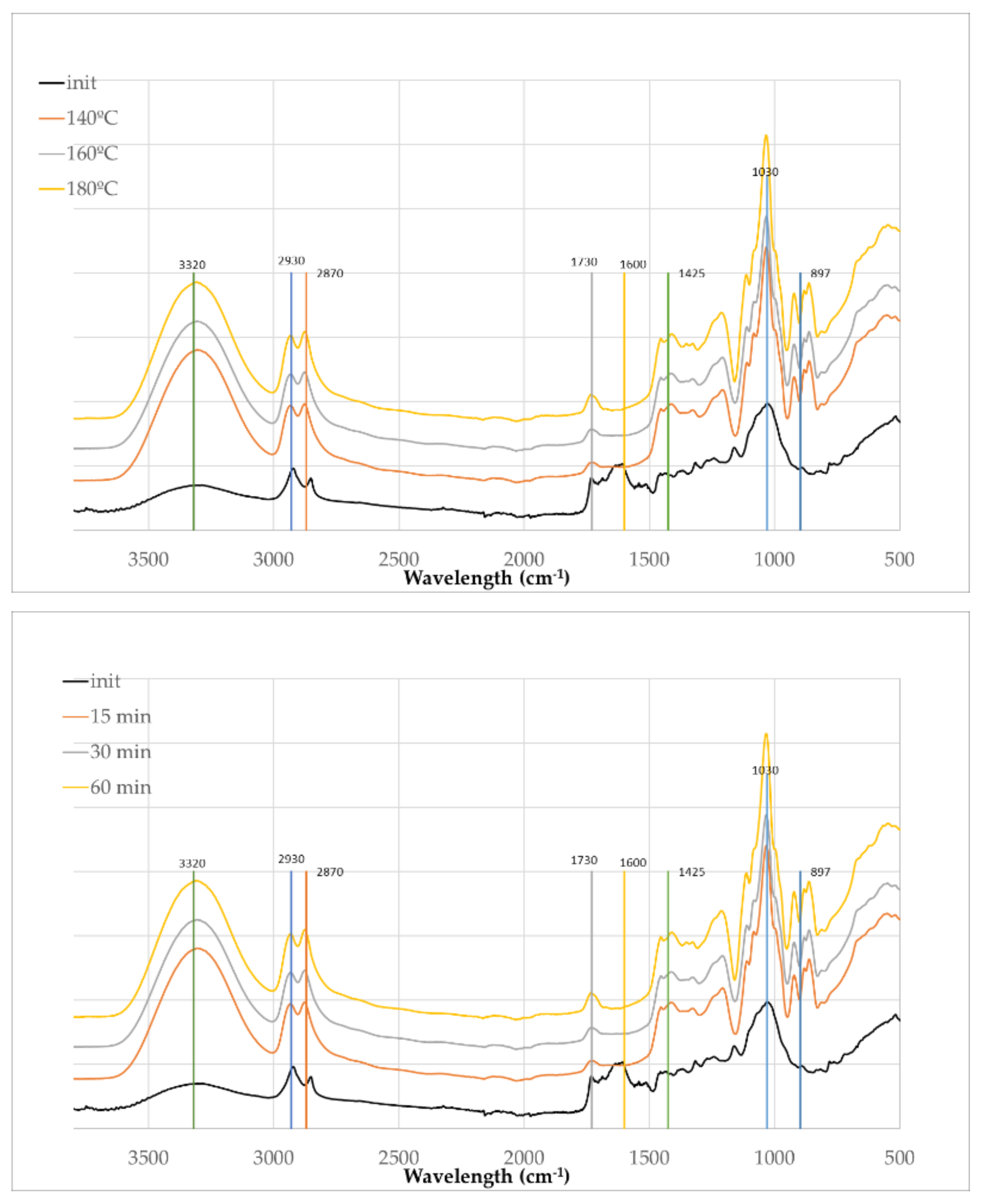

The FTIR-ATR spectra presented in

Figure 8 provides insight into the structural and chemical transformations occurring during the liquefaction of olive leaf biomass using polyalcohols. As with the branches samples, the initial (solid) olive leaves spectrum displays relatively lower absorption intensities due to the inherent limitations of ATR on solid materials. Upon liquefaction, the increase in absorbance across all regions is not only a result of improved contact with the ATR crystal in the liquid state but also indicative of chemical transformations occurring in the biomass

Similarly to olive branches the broad and intense peak at around 3320 cm⁻¹, attributed to O–H stretching vibrations, increases in intensity after liquefaction. This enhancement suggests the formation or exposure of hydroxyl functionalities, likely resulting from the depolymerization of lignin and polysaccharides and the interaction with polyalcohol solvents. Likewise, the peaks at 2930 cm⁻¹ and 2870 cm⁻¹, corresponding to C–H stretching vibrations in aliphatic chains, become more pronounced, indicating an increase in alkyl group content as a result of thermal cleavage and reorganization of biomass components.

The distinct band at 1730 cm⁻¹, characteristic of C=O stretching vibrations from esters, aldehydes, or carboxylic acids intensifies with increasing temperature and time. This suggests oxidative degradation and cleavage of ester linkages within hemicellulose and lignin structures, leading to the formation of carbonyl-containing compounds. The peaks at 1600 cm⁻¹, typically associated with aromatic skeletal vibrations from lignin, also decreases, implying partial preservation and transformation of aromatic moieties during liquefaction.

Of particular note is the band around 1030 cm⁻¹, attributed to C–O stretching vibrations in alcohols and ethers, which shows substantial growth in intensity, especially at higher temperatures and longer reaction times. This observation highlights the extensive breakdown of polysaccharides such as cellulose and hemicellulose into smaller polyol and ether-containing compounds. Concurrently, there is a decrease in the intensity of the peak at 897 cm⁻¹ and the appearance of new peaks in this region as seen for olive branches.

The results demonstrate that both temperature and time play critical roles in driving the chemical transformation, with 180°C for 60 minutes representing the most efficient condition for achieving extensive breakdown of the biomass and generation of polyol-rich liquefied products.