1. Introduction

Malnutrition due to inadequate nutritional intake is frequently observed in hospitalized patients. It is prevalent in geriatric, oncologic, and gastroenterological patients, and those with chronic or severe diseases [

1]. However, this condition involves also well-nourished patients who experience a decline in nutrition status during hospitalization in 30% - 38% of the cases [

2].

Malnutrition significantly impacts clinical outcomes, including increased mortality, morbidity, length of hospital stay, and overall healthcare costs. International guidelines from the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN) and the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) strongly recommend early nutritional screening within the first 24-48 hours of hospital admission to initiate timely and appropriate nutritional interventions [

3,

4].

Artificial nutrition (AN), whether enteral or parenteral, is a critical intervention to ensure adequate caloric and protein intake in patients unable to meet their nutritional requirements orally. Despite detailed recommendations provided by international scientific societies, numerous studies highlight substantial variability and deficiencies in clinical practice, notably delays in initiating AN, inadequate caloric and protein dosing, and disparities in treatment across patient groups [

5,

6,

7].

Nutrition therapy for diseased patients is often complex, as it should not only satisfy patients’ nutritional needs but also address the specific disease-related requirements. This is challenging for healthcare providers who don’t have specific nutrition training. Moreover, clinical nutrition education remains inconsistent within university medical curricula, leading to inadequate knowledge among healthcare professionals, exacerbating this issue [

8].

Recent studies underline the necessity for improved and standardized nutrition education in medical schools to enhance clinician awareness and competency regarding the importance of nutritional management in clinical practice [

9,

10].

In this report, we present the results obtained by collecting data on hospitalized patients undergoing AN across 35 medical and surgical wards and the intensity care unit in a university hospital in Southern Italy. This study aims to describe the implementation of AN in real-world hospital settings, paying particular attention to adherence to international guidelines and optimal standards of nutritional care, and identifying critical issues and areas for improvement in clinical practice.

2. Patients and Methods

This observational study was conducted over a single day and evaluated patients receiving artificial nutrition (AN) at the Bari Polyclinic University Hospital. The nutritional treatment consisted of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or enteral nutrition (EN) or EN plus supportive parenteral nutrition (SPN). Patients were allocated to 35 medical and surgical wards or the intensity care unit (ICU). For each patient, we collected data on anthropometric measurements, underlying medical conditions, comorbidities, and all relevant information concerning their AN. These data were collected by a team of trained medical doctors and dietitians specialized in this field. Patients' body weight was measured, whereas, in most cases, height was calculated using the length of the ulna, as reported in the literature [

11]. We assessed the appropriateness of nutritional treatment to determine whether it met the patients' medical conditions and caloric-protein needs. The total caloric intake was calculated based on the nutritional bag or enteral product as well as the duration of the infusion. Caloric requirements were calculated using the most accurate prediction formula suggested for a specific body mass index (BMI) range. The Harris-Benedict was used for BMI values >18.5 and <25 kg/m

2, WHO equation for a BMI ≥25 and <30 kg/m

2, Mifflin for a BMI 30–39.9 kg/m

2, and Henry for a BMI ≥40 kg/m

2 [

12]. The basal metabolic rate calculated from these formulas was then multiplied by a factor of 1.2-1.6, depending on the patient’s clinical condition, except for ICU patients. For those in the ICU, appropriate nutrition was considered either ”trophic nutrition” (10–20 kcal/h or up to 500 kcal/day) or “full nutrition” (>80% of estimated or calculated energy and protein requirements), depending on the timing of their admission to the ICU [

13].

The study was conducted in agreement with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Ethic Committee (Prot. 373; 12/06/2024).

2.1. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) based on the distribution verified by the Shapiro-Wilk test. All statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel 2021 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WD, USA).

3. Results

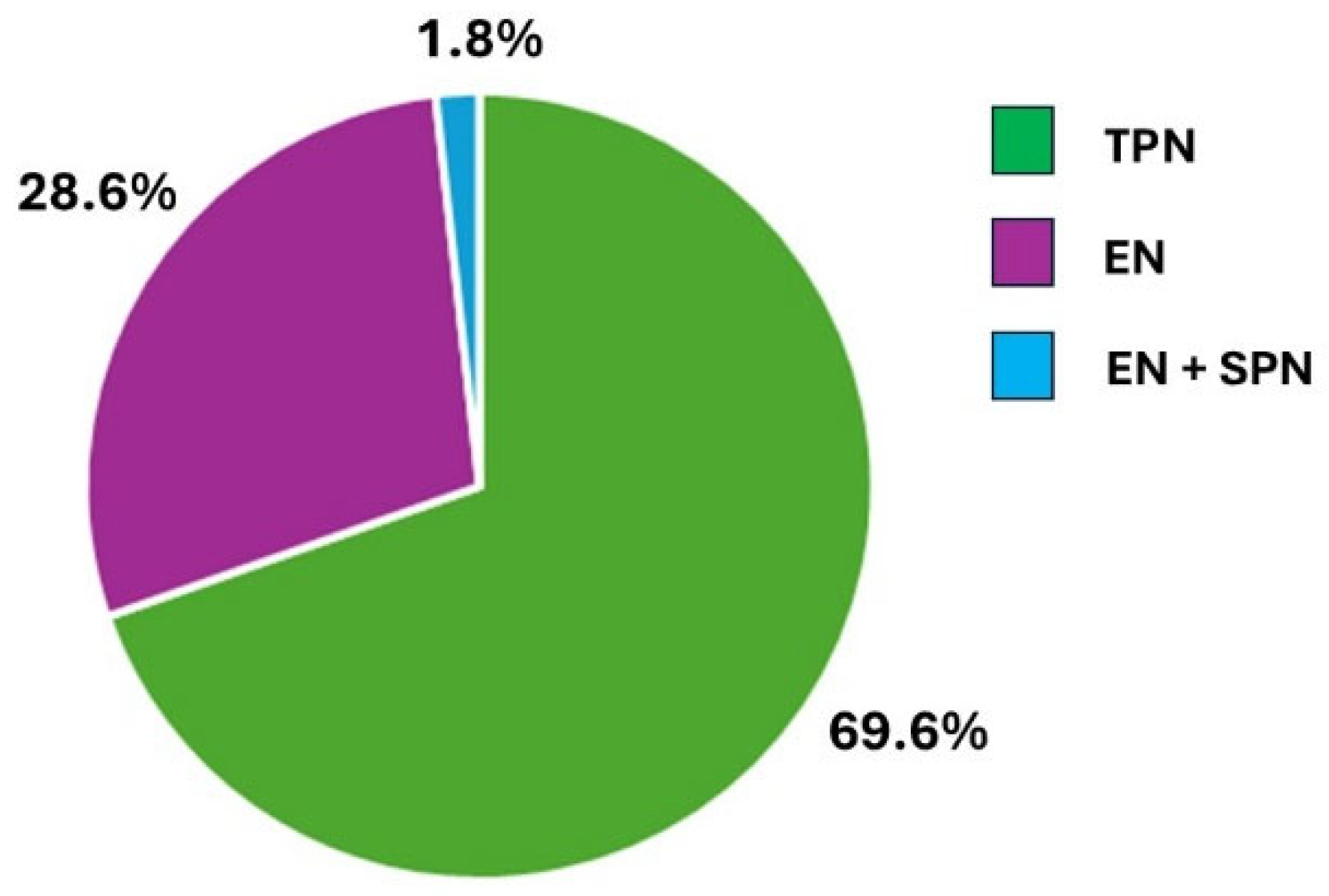

Among 578 hospitalized patients, 56 (9.7%; 30 males, 26 females), with a mean age of 67.1 ± 11.6 years, were receiving artificial nutrition (AN). The modalities of AN administration were as follows: total parenteral nutrition (TPN) in 39 patients, enteral nutrition (EN) in 16 patients, and EN plus supportive parenteral nutrition (SPN) in 1 patient (

Figure 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients receiving AN are described in table 1.

BMI in males ranged from normal to overweight (≥ 18.5 - < 30 kg/m

2), whereas some females were underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m

2) or obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m

2). The median time to initiate AN after hospital admission was 3 days (IQR 0-13.5 days). In detail, ICU patients received an earlier AN from admission compared to patients in other wards [median time 1 day (IQR 0-2) compared to 5 days (IQR 0-16), respectively]. Patients admitted to the ICU accounted for 15 (26.8%), whereas 37 (66.1%) were admitted to various medical wards, and 4 (7.1%) to surgical wards (

Table 1). The main cause of hospitalization was cancer (21.4%) (9 solid tumors, 3 hematological malignancies), followed by respiratory failure (17.8%) (7 acute and 3 acute on chronic). The remaining 34 patients were hospitalized for different pathologies, including 4 (7.1%) for malnutrition (

Table 1).

As shown in

table 2, among the 39 patients receiving TPN through a venous access, 21 had a peripheral catheter (PC), 8 had a midline catheter (MC), and 10 had a peripheral implanted central catheter (PICC). Only three patients with a PICC achieved the proper caloric intake through the infusion of a peripheral (low osmolarity) (1 patient) or a central (high osmolarity) (2 patients) nutritional bag. However, only 1 of them received an adequate protein intake (≥ 1g/kg b.w.).

Almost all patients on NGT feeding (11 out of 12) were in the ICU and their caloric and protein intake was 6-12 kcal/kg b.w. and 0.44 ± 0.16 g of proteins/kg b.w., respectively. The 5 patients fed through PEG were allocated to different medical and surgical wards. Only 1 of the 17 patients receiving EN received an adequate caloric and protein intake (1625 kcal/day and 1.38 g protein/kg b.w.). The patient receiving NGT plus SPN was admitted to the ICU after surgery and received a low caloric and protein intake.

4. Discussion

Our findings suggest an increased utilization of artificial nutrition in hospitalized patients compared to previous data from literature obtained in a similar contest [

14]. However, despite this increase, the adherence to evidence-based guidelines regarding the timing, the dosage, and the modality of nutritional support is still unsatisfactory.

One of our most relevant findings was the delay in initiating nutritional therapy. Except for patients admitted to ICU, nutritional treatment started 10 days after admission in about 50% of the patients. This delay is clinically relevant if we consider that early nutritional support has been associated with reduced morbidity and mortality in both general ward and ICU patients. Current ESPEN guidelines recommend starting nutritional therapy within 48 hours for high-risk or malnourished individuals, while our data reflect a suboptimal application of these clinical protocols.

Furthermore, we found that only three patients among those receiving total parenteral nutrition reached their energy requirements using prediction equations, as reported in the materials and methods section [

12], or simply applying the range 20-30 kcal/kg b.w. [15, 16]. Moreover, among them, only one met the correct protein target (> 0.8-1.0 g/kg b.w./day) [

16,

17]. Patients on enteral nutrition experienced similar unsatisfactory nutritional support, with only one achieving adequate energy and protein intake (> 0.8-1.0 g/kg b.w./day) [

16].

All the patients admitted to ICU received trophic nutrition (10–20 kcal/h or up to 500 kcal/day), i.e. a low intake of calories and proteins, which was maintained throughout their stay in the intensive care unit. However, trophic nutrition is considered appropriate when administered during the initial period of admission in ICU. Subsequently, critically ill patients should receive at least two-thirds of their prescribed caloric intake, as suggested by their lower risk of death compared to those receiving less than one-third of their prescribed amount (odds ratio 0.67; 95% confidence interval 0.56–0.79; p<0.0001) [

18,

19]. Furthermore, patients admitted to intensive care suffer from a persistent state of inflammation, catabolism, and immunosuppression that influence their prognosis so that 56% of them die before discharge or require a long period of rehabilitation following discharge [

20,

21].

As far as the modality of nutritional support, our findings indicate a clear prevalence of the use of total parenteral nutrition compared to enteral nutrition and the total absence of the use of food for special medical purposes. Several theoretical reasons, corroborated by numerous experimental data, strongly support the benefits of choosing EN over PN [

22,

23]. However, the advantage of enteral feeding seems limited to surrogate nutritional outcomes such as length of hospital stay and intestinal function recovery or other clinical outcomes such as risk of infections [

22,

24]. Therefore, the choice should depend on the availability of the gastrointestinal tract for feeding and the patient’s tolerance levels [

22,

23].

Finally, our analysis also reveals an unequal distribution of nutritional care based on the diagnosis of admission. Most patients were admitted with cancer or respiratory failure, whereas only 7.1% were hospitalized for primary malnutrition, reflecting a missed opportunity for early identification and proactive support. This insufficient nutritional engagement seems connected to the lack of systematic screening tools.

The use of screening tools to recognize patients at risk of malnutrition should be mandatory for hospitalized patients, in order to prevent or treat malnutrition. There are currently several malnutrition screening tools available, such as malnutrition universal screening tool (MUST), malnutrition screening tool (MST), nutritional risk screening 2002 (NRS-2002), and minimal nutritional assessment (MNA) short form. [

25]. They differ in their complexity depending on the number of parameters evaluated. Other widely validated screening tools for the diagnosis of malnutrition are the Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition (GLIM) criteria and the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA). [

26,

27].

Once patients at risk of malnutrition are identified, the application of the screening tools should be followed by diagnosis and appropriate treatment, which can range from simple dietary counseling to artificial nutrition. This should entail strict collaboration between dieticians and physicians with specific nutrition competencies. These tools are inconsistently applied, however, thus contributing to the under-detection of malnourished patients and delayed treatment.

Despite the NEMS (Nutrition Education in Medical Schools) initiative by ESPEN and existing postgraduate education via the Life-Long Learning (LLL) platform, clinical nutrition remains undervalued in medical education [

28,

29,

3].

This study reinforces the urgent need for systematic screening using validated tools on admission, standardized early activation protocols for AN, tailored educational programs to bridge existing knowledge gaps, and organizational models that include dietitians and clinical nutritionists in multidisciplinary teams.

Improving these areas is critical to reduce the burden of hospital-related malnutrition and ensure equitable, timely, and effective nutritional support.

5. Conclusions

All these data document a lack of specific nutritional training for healthcare providers and the absence or simply an undervaluation of the involvement of an expert nutritionist in the clinical care.

The persistent challenges in implementing artificial nutrition in a hospital setting despite the existence of comprehensive guidelines highlights the discrepancy between the growing awareness around the importance of nutritional support and the clinical practice.

The integration of trained nutrition professionals within care teams should become standard practice to guarantee a systematic screening for malnutrition with a timely initiation of nutritional support. Moreover, introducing undergraduate and postgraduate courses in clinical nutrition would empower healthcare providers with the necessary tools for an appropriate nutritional care.

Efforts to optimize nutritional therapy can improve patient outcomes, reduce healthcare costs, and reduce the gap between guidelines and practice. Prospective studies are still necessary to evaluate the impact of structured interventions in nutritional education and their effects on clinical care outcomes.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; data curation P.B., M.P., V.A., N.F., D.A., A.C., M.D.B., M.P., V.B., L.M., I.M., A.A., A.M.; review and editing, S.G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of (Prot. 373; 12/06/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

data can be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AN |

Artificial nutrition |

| ICU |

Intensive care unit |

| TPN |

Total parenteral nutrition |

EN

SPN

PICC

PC

MC

NGT

PEG

MUST

MST

NRS-2002

MNA

GLIM

PG-SGA |

Enteral nutrition

Supportive parenteral nutrition

Peripheral implanted central catheter

Peripheral catheter

Midline catheter

Naso-gastric tube

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

Malnutrition universal screening tool

Malnutrition screening tool

Nutritional risk screening 2002

Minimal nutritional assessment

Global leadership initiative on malnutrition

Patient-generated – subjective global assessment |

References

- Pirlich, M., Schütz, T., Norman, K., Gastell, S., Lübke, H.J., Bischoff, S.C., Bolder, U., Frieling, T., Güldenzoph, H., Hahn, K., et al. The German hospital malnutrition study. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 25, 563–572. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolado Jiménez, C., Fernádez Ovalle, H., Muñoz Moreno, M.F., Aller de la Fuente, R., de Luis Román, D.A. Undernutrition measured by the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) test and related risk factors in older adults under hospital emergency care. Nutrition 2019, 66, 142–146. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cederholm T, Barazzoni R, Austin P, Ballmer P, Biolo G, Bischoff SC, Compher C, Correia I, Higashiguchi T, Holst M, et al. ESPEN guidelines on definitions and terminology of clinical nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 36, 49–64. [CrossRef]

- McClave, S.A., Taylor, B.E., Martindale, R.G., Warren, M.M., Johnson, D.R., Braunschweig, C., McCarthy, M.S., Davanos, E., Rice, T.W., Cresci, G.A., et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2016, 40, 159–211. [CrossRef]

- Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Alhazzani W, Calder PC, Casaer MP, Hiesmayr M, Mayer K, Montejo JC, Pichard C, Preiser JC, van Zanten ARH, Oczkowski S, Szczeklik W, Bischoff SC. ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2019 Feb;38(1):48-79. [CrossRef]

- Singer P, Blaser AR, Berger MM, Calder PC, Casaer M, Hiesmayr M, Mayer K, Montejo-Gonzalez JC, Pichard C, Preiser JC, Szczeklik W, van Zanten ARH, Bischoff SC. ESPEN practical and partially revised guideline: Clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2023 Sep;42(9):1671-1689. [CrossRef]

- Correia MI, Hegazi RA, Higashiguchi T, Michel JP, Reddy BR, Tappenden KA, Uyar M, Muscaritoli M. Evidence-based recommendations for addressing malnutrition in health care: an updated strategy from the feedM.E. Global Study Group. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014 Aug;15(8):544-50. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S., Sytsma, T., Wischmeyer, P.E. Addressing the Urgent Need for Clinical Nutrition Education in PostGraduate Medical Training: New Programs and Credentialing. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100321. [CrossRef]

- Adams K.M., Butsch W.S., Kohlmeier M. The state of nutrition education at US medical schools. J. Biomed. Edu. 2015, 357627. [CrossRef]

- Devries, S. , Willett, W. , Bonow, R.O. Nutrition Education in Medical School, Residency Training, and Practice. JAMA. 2019, 321, 1351–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.uhs.nhs.uk/Media/Southampton-Clinical-Research/Procedures/BRCProcedures/Procedure-for-adult-ulna-length.pdf.

- Madden, A.M. , Mulrooney, H.M., Shah, S. Estimation of energy expenditure using prediction equations in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 29 458-476. [CrossRef]

- McClave, S.A., Taylor, B.E., Martindale, R.G., Warren, M.M., Johnson, D.R., Braunschweig, C., McCarthy, M.S., Davanos, E., Rice, T.W., Cresci, G.A., et al. Guidelines for the Provision and Assessment of Nutrition Support Therapy in the Adult Critically Ill Patient: Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM) and American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (A.S.P.E.N.). J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2016, 40, 159–211. [CrossRef]

- Amato, V., De Caprio, C., Santarpia, L., De Rosa, A., Bongiorno, C., Stella, G., De Rosa, E., Iacone, R., Scanzano, C., Pasanisi, F., et al. Time trend prevalence of artificial nutrition counselling in a university hospital. Nutrition. 2019, 58, 181–186. [CrossRef]

- https://nutritioncare.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/Appropriate-Dosing-for-PN.pdf.

- Thibault R, Abbasoglu O, Ioannou E, Meija L, Ottens-Oussoren K, Pichard C, Rothenberg E, Rubin D, Siljamäki-Ojansuu U, Vaillant MF, Bischoff SC. ESPEN guideline on hospital nutrition. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5684–5709. [CrossRef]

- Berlana D. Parenteral Nutrition Overview. Nutrients. 2022, 14, 4480. [CrossRef]

- Mira, J.C., Cuschieri, J., Ozrazgat-Baslanti, T., Wang, Z., Ghita, G.L., Loftus, T.J., Stortz, J.A., Raymond, S.L., Lanz, J.D., Hennessy, L.V., et al. The Epidemiology of Chronic Critical Illness After Severe Traumatic Injury at Two Level-One Trauma Centers. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 1989–1996. [CrossRef]

- Heyland, D.K., Cahill, N., Day, A.G. Optimal amount of calories for critically ill patients: depends on how you slice the cake! Crit. Care Med. 2011, 39, 2619–2626. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Y., Dai, T., Song, G., Li, X., Liu, X., Liu, Z., Yang, Q., Jia, R., Yang, Q., Peng, X., et al. Associations between Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment criteria and all-cause mortality among cancer patients: Evidence from baseline and longitudinal analyses. Nutrition 2024, 127, 112551. [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, M.D., Bala T, Wang Z, Loftus T, Moore F. Chronic Critical Illness Patients Fail to Respond to Current Evidence-Based Intensive Care Nutrition Secondarily to Persistent Inflammation, Immunosuppression, and Catabolic Syndrome. J. Parenter. Enteral Nutr. 2020, 44, 1237–1249. [CrossRef]

- Seres DS, Valcarcel M, Guillaume A. Advantages of enteral nutrition over parenteral nutrition. Therap. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2013, 6, 157–167. [CrossRef]

- Jeejeebhoy KN. Enteral nutrition versus parenteral nutrition--the risks and benefits. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepato. 2007, 4, 260–265. [CrossRef]

- Papanikolaou P, Theodoridis X, Papaemmanouil A, Papageorgiou NN, Tsankof A, Haidich AB, Savopoulos C, Tziomalos K. Enteral Nutrition Versus a Combination of Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition in Critically Ill Adult Patients in the Intensive Care Unit: An Overview of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 991. [CrossRef]

- Totland, T.H., Krogh, H.W., Smedshaug, G.B., Tornes, R.A., Bye, A., Paur, I. Harmonization and standardization of malnutrition screening for all adults - A systematic review initiated by the Norwegian Directorate of Health. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 2022, 52, 32–49. [CrossRef]

- Cederholm, T., Jensen, G.L., Correia, M.I.T.D., Gonzalez, M.C., Fukushima, R., Higashiguchi, T., Baptista, G., Barazzoni, R., Blaauw, R., Coats, A., et al. GLIM criteria for the diagnosis of malnutrition - A consensus report from the global clinical nutrition community. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 38, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Cuerda, C., Muscaritoli, M., Krznaric, Z., Pirlich, M., Van Gossum, A., Schneider, S., Ellegard, L., Fukushima, R., Chourdakis, M., Della Rocca, C., et al. Nutrition education in medical schools (NEMS) project: Joining ESPEN and university point of view. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 2754–2761. [CrossRef]

- Cuerda, C,. Muscaritoli, M., Chourdakis, M., Krznaric, Z., Archodoulakis, A., Gürbüz, S., Berk, K., Aapro, M., Farrand, C., Patja, K., et al. Nutrition education in medical schools (NEMS) project: Promoting clinical nutrition in medical schools - Perspectives from different actors. Clin. Nutr. 2023, 42, 54–59. [CrossRef]

- https://www.espen.org/education/lll-programme.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).