Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

2.1. Data and variables

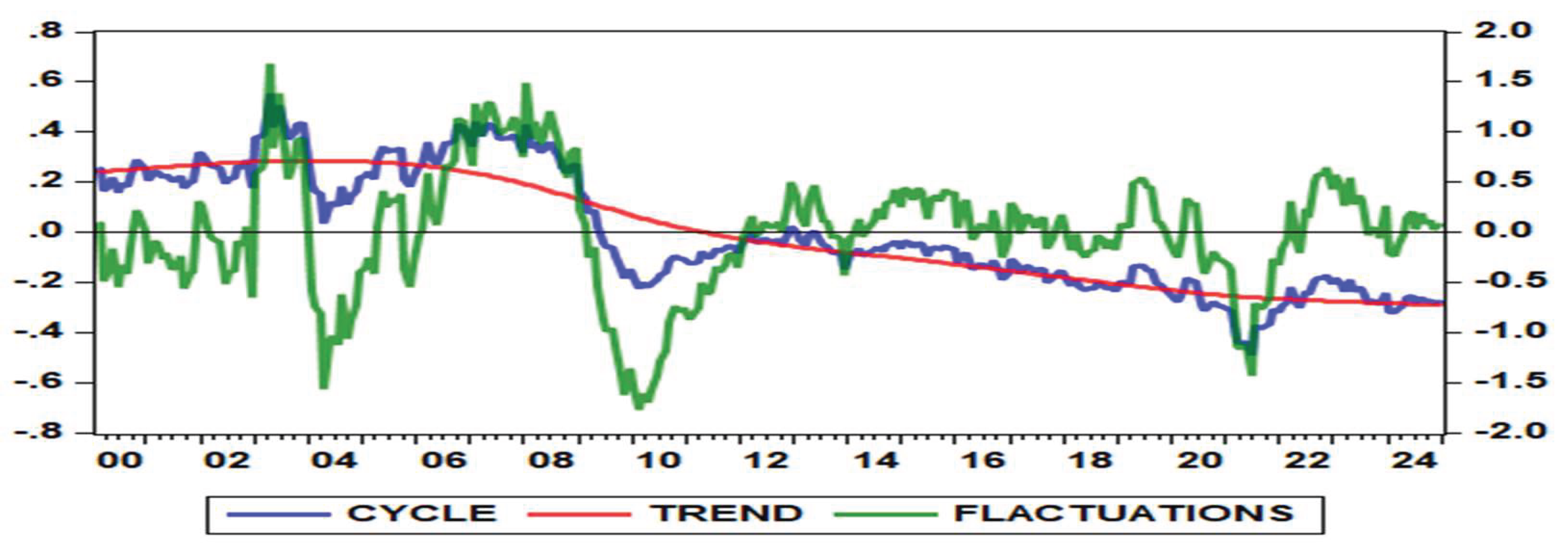

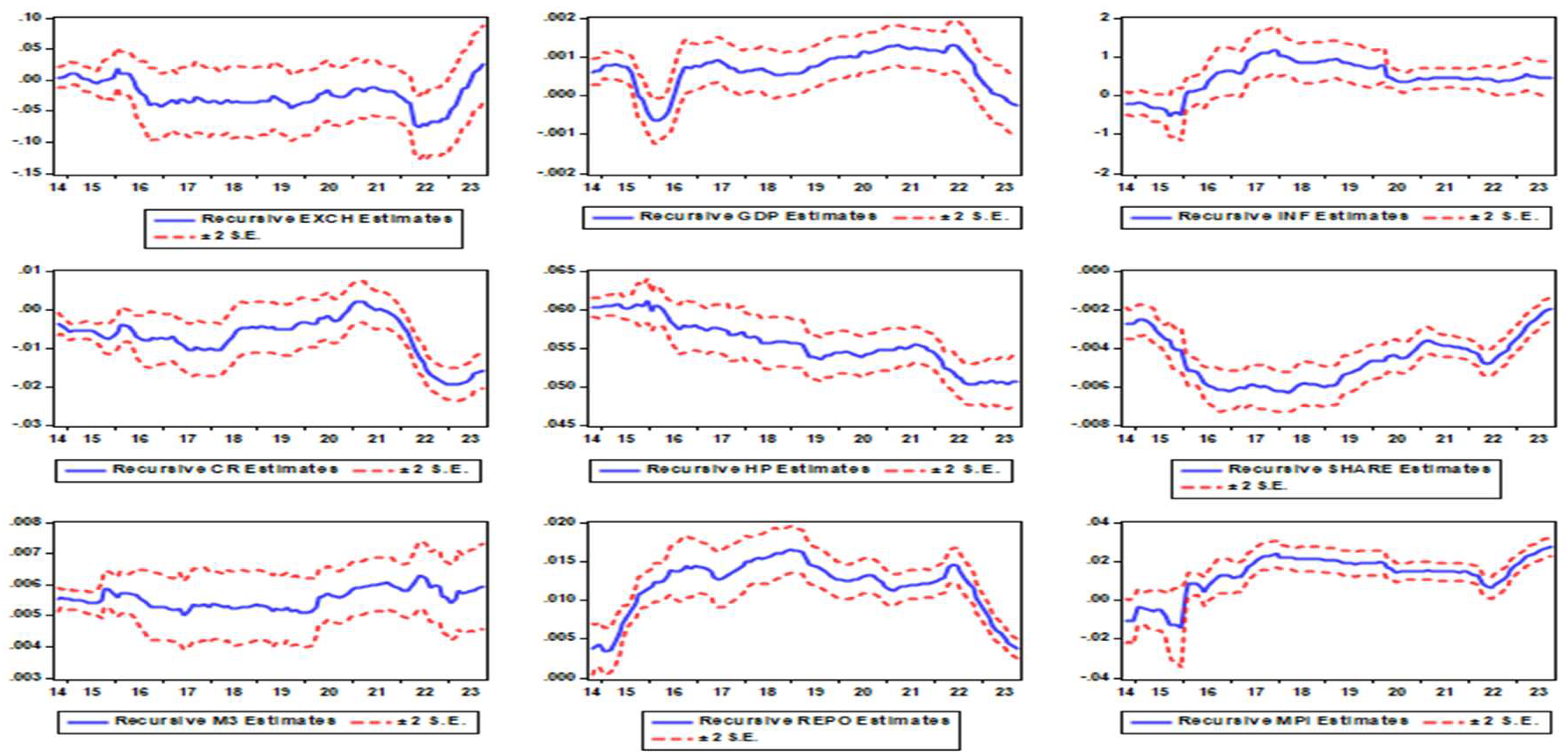

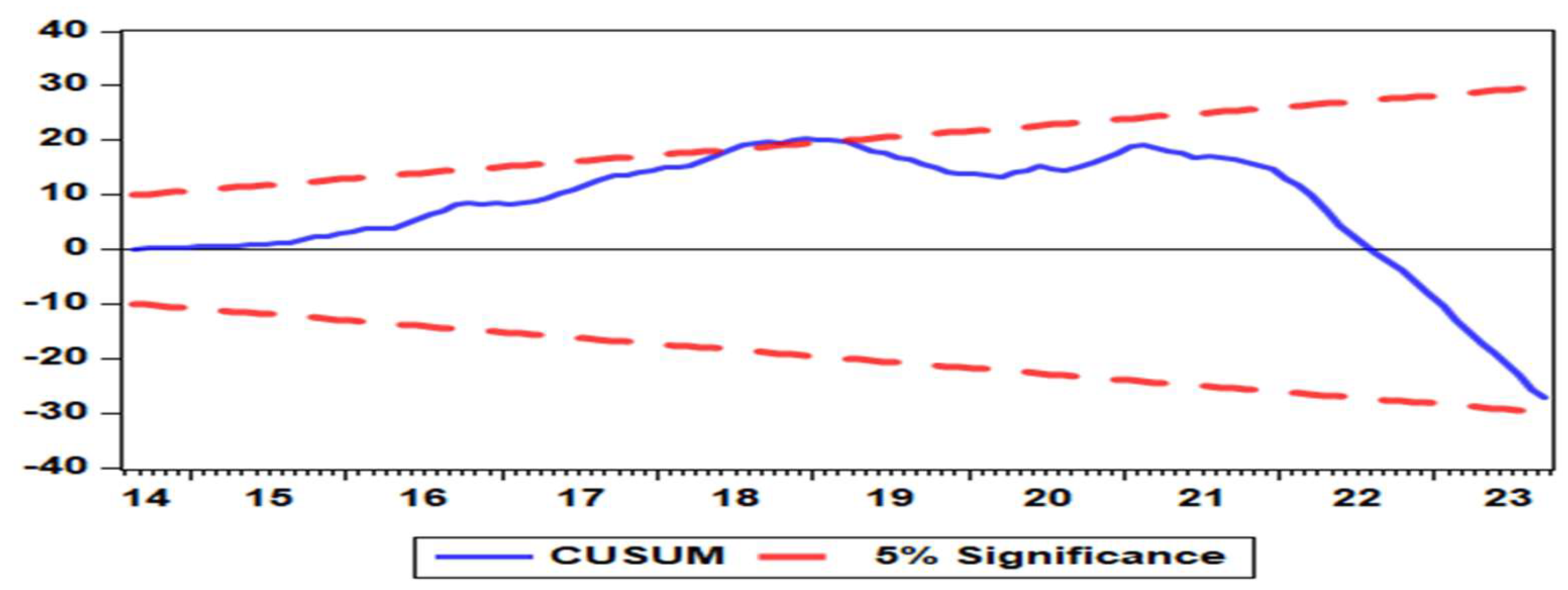

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADF | Augmented Dickey-Fuller |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| ARDL | Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| CUSUM | Cumulative Sum (of Recursive Residuals) Test |

| CR | Total Domestic Credit (as % of GDP) |

| EXCH | Real Effective Exchange Rate |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| GFC | Global Financial Crisis |

| HP | Real House Price Index |

| I(0) | Integrated of order 0 (stationary) |

| I(1) | Integrated of order 1 (non-stationary) |

| IMF | International Monetary Fund |

| INF | Inflation Rate |

| M3 | Broad Money Supply |

| MPI | Macroprudential Policy Index |

| OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| QARDL | Quantile Autoregressive Distributed Lag |

| REPO | Repo Rate |

| SARB | South African Reserve Bank |

| SHARE | Real All Share Price Index |

| VECM | Vector Error Correction Model |

References

- Adrian, T.; Shin, H.S. Liquidity, monetary policy, and financial cycles. Current issues in economics and finance 2008, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Adrian, T.; Boyarchenko, N.; Shin, H.-S. The cyclicality of leverage. Tech. rep.

- Adusei, M. Financial development and economic growth: Evidence from Ghana. The International Journal of Business and Finance Research 2013, 7, 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Agénor, P.-R.; da Silva, L.A. (2019). Integrated inflation targeting-Another perspective from the developing world.

- Aikman, D.; Haldane, A. G. , & Nelson, B. D. Curbing the credit cycle. The Economic Journal 2015, 125, 1072–1109. [Google Scholar]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE transactions on automatic control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldasoro, I.; Avdjiev, S.; Borio, C. E. , & Disyatat, P. (2020). Global and domestic financial cycles: variations on a theme.

- Amador-Torres, J. S. , Gomez-Gonzalez, J. E., Ojeda-Joya, J. N., Jaulin-Mendez, O. F., & Tenjo-Galarza, F. Mind the gap: Computing finance-neutral output gaps in Latin-American economies. Economic Systems 2016, 40, 444–452. [Google Scholar]

- Angelini, P.; Neri, S.; Panetta, F. The interaction between capital requirements and monetary policy. Journal of money, credit and Banking 2014, 46, 1073–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, A.; Sharif, A.; Fatima, S.; Ahmad, P.; Sinha, A.; Khan, S. A. , & Jermsittiparsert, K. The asymmetric effect of public private partnership investment on transport CO2 emission in China: Evidence from quantile ARDL approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 288, 125282. [Google Scholar]

- Arcand, J.L.; Berkes, E.; Panizza, U. Too much finance? Journal of economic growth 2015, 20, 105–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, J.; Muellbauer, J. Wealth, credit conditions, and consumption: Evidence from South Africa. Review of Income and Wealth 2013, 59, S161–S196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, J.; Muellbauer, J. Modelling and forecasting mortgage delinquency and foreclosure in the UK. Journal of Urban Economics 2016, 94, 32–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, J.; Muellbauer, J.; Prinsloo, J. (2006). Estimating household-sector wealth in South Africa. Quarterly Bulletin (South African Reserve Bank).

- Aron, J.; Muellbauer, J.; Prinsloo, J. (2012). South African reserve Bank working paper.

- Bai, Y.; Kehoe, P. J. , & Perri, F. World financial cycles. 2019 meeting papers 2019, 1545. [Google Scholar]

- Bakar, H. O. , & Sulong, Z. The role of financial sector on economic growth: Theoretical and empirical literature reviews analysis. Journal of Global Economics 2018, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, R.; Georgiadis, G.; Straub, R. The finance and growth nexus revisited. Economics Letters 2014, 124, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R. Stock markets, banks, and growth: Panel evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance 2004, 28, 423–442. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Loayza, N. Finance and the Sources of Growth. Journal of financial economics 2000, 58, 261–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, M. C. , & Knudsen, T. Schumpeter 1911: farsighted visions on economic development. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 2002, 61, 387–403. [Google Scholar]

- Beirne, J. Financial cycles in asset markets and regions. Economic Modelling 2020, 92, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, B.S. The real effects of disrupted credit: Evidence from the global financial crisis. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2018, 2018, 251–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernanke, B. S. , & Gertler, M. Inside the black box: the credit channel of monetary policy transmission. Journal of Economic perspectives 1995, 9, 27–48. [Google Scholar]

- Bernanke, B. S., Gertler, M., & Gilchrist, S. (1994). The financial accelerator and the flight to quality. The financial accelerator and the flight to quality. National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge, Mass., USA.

- Bertocco, G. The role of credit in a Keynesian monetary economy. Review of Political Economy 2005, 17, 489–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, D. N. , Federmair, K., Fink, G., & Haiss, P. R. (2002). The financial-real sector nexus: Theory and empirical evidence. Research Institute for European Affairs Working Paper.

- Borio, C. Implementing a macroprudential framework: Blending boldness and realism. Capitalism and society 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borio, C. (2014). The financial cycle and macroeconomics: what have we learned and what are the policy implications? In Financial Cycles and the Real Economy (pp. 10–35). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Borio, C. E. , & Drehmann, M. (2009). Assessing the risk of banking crises–revisited. BIS Quarterly Review, March.

- Borio, C. E. , & Lowe, P. W. (2002). Asset prices, financial and monetary stability: exploring the nexus.

- Borio, C. E. , Drehmann, M., & Xia, F. D. (2018). The financial cycle and recession risk. BIS Quarterly Review December.

- Borio, C. E. , Drehmann, M., & Xia, F. D. (2019). Predicting recessions: financial cycle versus term spread.

- Borio, C.; Zhu, H. Capital regulation, risk-taking and monetary policy: a missing link in the transmission mechanism? Journal of Financial stability 2012, 8, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch, A.; Koch, S.F. The South African financial cycle and its relation to household deleveraging. South African Journal of Economics 2020, 88, 145–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, J. H. , Levine, R., & Smith, B. D. The impact of inflation on financial sector performance. Journal of monetary Economics 2001, 47, 221–248. [Google Scholar]

- Breusch, T. S. , & Pagan, A. R. J: for heteroscedasticity and random coefficient variation. Econometrica, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brunnermeier, M. K. , & Sannikov, Y. A macroeconomic model with a financial sector. American Economic Review 2014, 104, 379–421. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchetti, S.G. (2000). Asset prices and central bank policy. Centre for Economic Policy Research.

- Cecchetti, S. G. , & Kharroubi, E. (2012). Reassessing the impact of finance on growth.

- Cerutti, E.; Claessens, S.; Laeven, L. The use and effectiveness of macroprudential policies: New evidence. Journal of financial stability 2017, 28, 203–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarella, C.; Di Guilmi, C. Monetary policy and debt deflation: some computational experiments. Macroeconomic Dynamics 2017, 21, 214–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chorafas, D.N. Financial cycles. In Financial Cycles: Sovereigns 2015, Bankers, and Stress Tests (pp. 1–24). Springer.

- Christensen, I.; Dib, A. The financial accelerator in an estimated New Keynesian model. Review of economic dynamics 2008, 11, 155–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimoli, M.; Lima, G. T. , & Porcile, G. The production structure, exchange rate preferences and the short-run—Medium-run macrodynamics. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2016, 37, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens, S. An overview of macroprudential policy tools. Annual Review of Financial Economics 2015, 7, 397–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, S.; Ghosh, S. R. , & Mihet, R. Macro-prudential policies to mitigate financial system vulnerabilities. Journal of International Money and Finance 2013, 39, 153–185. [Google Scholar]

- Claessens, S.; Kose, M. A. , & Terrones, M. E. Financial cycles: what? how? when? NBER international seminar on macroeconomics, 7, pp. 303–344.

- Claessens 2011, S.; Kose, M. A. , & Terrones, M. E. How do business and financial cycles interact? Journal of International economics, 87, 178–190.

- Coimbra, N.; Rey, H. (2024). Financial cycles with heterogeneous intermediaries. Review of Economic Studies 2012, 91, 817–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbet, S.; Hou, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lucey, B.; Oxley, L. Aye Corona! The contagion effects of being named Corona during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finance Research Letters 2021, 38, 101591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockett, A. The theory and practice of financial stability. De Economist 1996, 144, 531–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Torre, A.; Gozzi, J. C., & Schmukler, S. L. (2017). Innovative Experiences in Access to Finance: Market-Friendly Roles for the Visible Hand? World Bank Publications.

- De Wet, M. C. , & Botha, I. Constructing and characterising the aggregate South African financial cycle: A Markov regime-switching approach. Journal of Business Cycle Research 2022, 18, 37–67. [Google Scholar]

- Detken, C. , Weeken, O., Alessi, L., Bonfim, D., Boucinha, M., Castro, C.,... others. (2014). Operationalising the countercyclical capital buffer: indicator selection, threshold identification and calibration options. ESRB: Occasional Paper Series.

- Drehmann, M.; Borio, C. E. , & Tsatsaronis, K. (2012). Characterising the financial cycle: don't lose sight of the medium term!

- Durusu-Ciftci, D.; Ispir, M. S. , & Yetkiner, H. Financial development and economic growth: Some theory and more evidence. Journal of policy modeling 2017, 39, 290–306. [Google Scholar]

- Epure, M.; Mihai, I.; Minoiu, C. ; Peydró; J-L Global financial cycle, household credit, and macroprudential policies. Management Science 2024, 70, 8096–8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, G.; Kemp, E. Measuring the financial cycle in South Africa. South African Journal of Economics 2020, 88, 123–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, G.; Haiss, P.; Mantler, H. (2004). Financial sector macro-efficiency. Financial Markets in Central and Eastern Europe, London, 61–98.

- Fisher, I. The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions. Revue de l'Institut International de Statistique/Review of the International Statistical Institute 1934, 1, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornari, F.; Lemke, W. (2010). Predicting recession probabilities with financial variables over multiple horizons. Tech. rep., ECB Working Paper.

- Foroni, C.; Gelain, P.; Marcellino, M.G. (2022). The financial accelerator mechanism: does frequency matter?

- Gammadigbe, V. Financial cycles synchronization in WAEMU countries: Implications for macroprudential policy. Finance Research Letters 2022, 46, 102281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, D.; Gaffeo, E.; Gallegati, M.; Giulioni, G.; Palestrini, A. (2008). Emergent macroeconomics: an agent-based approach to business fluctuations. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Geanakoplos, J. The leverage cycle. NBER macroeconomics annual 2010, 24, 1–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, M.; Karadi, P. A model of unconventional monetary policy. Journal of monetary Economics 2011, 58, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, S.; Bernanke, B.; Gertler, M. (1998). The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Giri, F.; Riccetti, L.; Russo, A.; Gallegati, M. Monetary policy and large crises in a financial accelerator agent-based model. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 2019, 157, 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Gonzalez, J. E. , Villamizar-Villegas, M., Zarate, H. M., Amador, J. S., & Gaitan-Maldonado, C. Credit and business cycles: Causal effects in the frequency domain. Ensayos sobre Polı́tica Económica 2015, 33, 176–189. [Google Scholar]

- Gorton, G.; Metrick, A. Securitized banking and the run on repo. Journal of Financial economics 2012, 104, 425–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, R. K. , & Malpezzi, S. (2003). A primer on US housing markets and housing policy. The Urban Insitute.

- Greenwood, J.; Jovanovic, B. Financial development, growth, and the distribution of income. Journal of political Economy 1990, 98, 1076–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurley, J. G. , & Shaw, E. S. Financial aspects of economic development. The American economic review 1955, 45, 515–538. [Google Scholar]

- \, *!!! REPLACE !!!*. Ha, J.; Kose, M. A., Otrok, C., & Prasad, E. S. (2020). Global macro-financial cycles and spillovers. Tech. rep., National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Harun, C. A. , Taruna, A. A., Nattan, R. R., & Surjaningsih, N. (2014). Financial Cycle of Indonesia—Potential Forward Looking Analysis. Tech. rep.

- Hashmi, S. M. , & Chang, B. H. Asymmetric effect of macroeconomic variables on the emerging stock indices: A quantile ARDL approach. International Journal of Finance & Economics 2023, 28, 1006–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Hashmi, S. M. , Chang, B. H., Huang, L., & Uche, E. Revisiting the relationship between oil prices, exchange rate, and stock prices: An application of quantile ARDL model. Resources Policy 2022, 75, 102543. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, M. K. , Sanchez, B., & Yu, J.-S. Financial development and economic growth: New evidence from panel data. The Quarterly Review of economics and finance 2011, 51, 88–104. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert, P.; Jaccard, I.; Schüler, Y. Contrasting financial and business cycles: Stylized facts and candidate explanations. Journal of Financial Stability 2018, 38, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, M. (2012). The road to debt deflation, debt peonage, and neofeudalism. Tech. rep., Working Paper.

- Ibrahim, M.; Alagidede, P. Effect of financial development on economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Policy Modeling 2018, 40, 1104–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immergluck, D. (2011). Foreclosed: High-risk lending, deregulation, and the undermining of America's mortgage market. Cornell University Press.

- Jordà; Ò; Schularick, M. ; Taylor, A.M. When credit bites back. Journal of money, credit and banking 2013, 45, 3–28.

- Jordà; Ò; Schularick, M. ; Taylor, A.M. The effects of quasi-random monetary experiments. Journal of Monetary Economics 2020, 112, 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordà, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Ò, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; Schularick, M.; Taylor, A. M. Jordà; Ò; Schularick, M.; Taylor, A. M., & Ward, F. (2018). Global financial cycles and risk premiums. Tech. rep., National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Khan, M. S. , Senhadji, A. S., & Smith, B. D. Inflation and financial depth. Macroeconomic Dynamics 2006, 10, 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Mehrotra, A. Examining macroprudential policy and its macroeconomic effects–some new evidence. Journal of International Money and Finance 2022, 128, 102697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindleberger, C.P. Manias, panics, and rationality. Eastern Economic Journal 1978, 4, 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kindleberger, C.P. Bubbles in history. Banking Crises: Perspectives from The New Palgrave Dictionary.

- King, R. G. , & Levine, R. Finance, entrepreneurship and growth. Journal of Monetary economics 1993, 32, 513–542. [Google Scholar]

- Kiyotaki, N.; Moore, J. Credit cycles. Journal of political economy 1997, 105, 211–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knell, M. Schumpeter, Minsky and the financial instability hypothesis. Journal of evolutionary Economics 2015, 25, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, K.; Stockhammer, E. Growing differently? Financial cycles, austerity, and competitiveness in growth models since the Global Financial Crisis. Review of International Political Economy 2022, 29, 1314–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krugman, P. (2001). Crises: the next generation. Conference Honoring Assaf Razin, Tel Aviv.

- Krznar, M. I., & Matheson, M. T. (2017). Financial and business cycles in Brazil. International Monetary Fund.

- Kunovac, D.; Mandler, M.; Scharnagl, M. (2018). Financial cycles in euro area economies: A cross-country perspective. Bundesbank Discussion Paper.

- Lane, P.R. The European sovereign debt crisis. Journal of economic perspectives 2012, 26, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, P. R. , & McQuade, P. Domestic credit growth and international capital flows. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 2014, 116, 218–252. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, J. H. , & Welz, P. (2018). Semi-structural credit gap estimation. ECB Working Paper.

- Levine, R. Financial development and economic growth: views and agenda. Journal of economic literature 1997, 35, 688–726. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, R. Finance and growth: theory and evidence. Handbook of economic growth 2005, 1, 865–934. [Google Scholar]

- Magubane, K. Exploring causal interactions between macroprudential policy and financial cycles in South Africa. International Journal of Research in Business & Social Science.

- Magubane, K.; Nyatanga, P.; Nzimande, N. Financial cycle synchronization in the advanced and systemic middle-income economies: evidence from a dynamic factor model. International Journal of Research in Business & Social Science.

- Malkiel, B.G. (1989). Efficient market hypothesis. In Finance (pp. 127–134). Springer.

- McCulley, P. , & others. The shadow banking system and Hyman Minsky’s economic journey. Insights into the global financial crisis.

- McKinnon, R.I. The value-added tax and the liberalization of foreign trade in developing economies: a comment. The value-added tax and the liberalization of foreign trade in developing economies: a comment 1973, 11, 520–524. [Google Scholar]

- Mensi, W.; Shahzad, S. J. , Hammoudeh, S., Hkiri, B., & Al Yahyaee, K. H. Long-run relationships between US financial credit markets and risk factors: Evidence from the quantile ARDL approach. Finance Research Letters 2019, 29, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R. C., & Thakor, R. T. (2015). Customers and investors: A framework for understanding financial institutions. Tech. rep., National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Mian, A.; Sufi, A.; Verner, E. Household debt and business cycles worldwide. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2017, 132, 1755–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minsky, H.P. (1970). Financial instability revisited: The economics of disaster. Financial instability revisited: The economics of disaster. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System St. Louis.

- Minsky, H.P. (1992). The financial instability hypothesis. Tech. rep., Working paper.

- Minsky, H.P. (1994). Financial instability and the decline (?) of banking: public policy implications. Tech. rep., Working Paper.

- Miranda-Agrippino, S.; Rey, H. (2022). The global financial cycle. In Handbook of international economics (Vol. 6, pp. 1–43). Elsevier.

- Mishkin, F.S. Global financial instability: framework, events, issues. Journal of economic perspectives 1999, 13, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishkin, F.S. (2007). Housing and the monetary transmission mechanism. Housing and the monetary transmission mechanism. National Bureau of Economic Research Cambridge, Mass., USA.

- Mlachila, M.; Dykes, D.; Zajc, S.; Aithnard, P.-H.; Beck, T.; Ncube, M.; Nelvin, O. (2013). Banking in sub-Saharan Africa: Challenges and opportunities.

- Modigliani, F.; Miller, M.H. The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. The American economic review 1958, 48, 261–297. [Google Scholar]

- Munk, C. (2018). Financial markets and investments. Copenhagen, Denmark: Lecture notes.

- Narayan, P.K. The saving and investment nexus for China: evidence from cointegration tests. Applied economics 2005, 37, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T. (2011). The predictive content of financial cycle measures for output fluctuations. BIS Quarterly Review, June.

- Nkoro, E.; Uko, A. K. , & others. Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) cointegration technique: application and interpretation. Journal of Statistical and Econometric methods 2016, 5, 63–91. [Google Scholar]

- Nyati, M. C. , Tipoy, C. K., & Muzindutsi, P.-F. (2021). Measuring and testing a modified version of the South African financial cycle. Economic Research Southern Africa Cape Town.

- Odhiambo, N.M. Energy consumption and economic growth nexus in Tanzania: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Energy policy 2009, 37, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, N.M. Finance-investment-growth nexus in South Africa: an ARDL-bounds testing procedure. Economic change and restructuring 2010, 43, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oman, W. The synchronization of business cycles and financial cycles in the euro area. International Journal of Central Banking 2019, 15, 327–362. [Google Scholar]

- Padayachee, V.; Sherbut, G. Ideas and Power Academic Economists and the Making of Economic Policy. The South African Experience in Comparative Perspective (1985-2007). Cahiers d’études africaines 2011, 51, 609–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, M. Financial markets and growth: An overview. European economic review 1993, 37, 613–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parusel, M.; Viegi, N. (2009). Economic policy in turbulent times. Economic policy in turbulent times. Citeseer.

- Pesaran, M. H. , Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of applied econometrics 2001, 16, 289–326. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran, M. H. , Shin, Y., & Smith, R. P. Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of the American statistical Association 1999, 94, 621–634. [Google Scholar]

- Potjagailo, G.; Wolters, M.H. Global financial cycles since 1880. Journal of International Money and Finance 2023, 131, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabheesh, K. P. , Anglingkusumo, R., & Juhro, S. M. The dynamics of global financial cycle and domestic economic cycles: Evidence from India and Indonesia. Economic Modelling 2021, 94, 831–842. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Škare, M. ; Porada-Rochoń; M Financial cycles in the economy and in economic research: A case study in China. Technological and Economic Development of Economy 2021, 27, 1250–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, J.B. Tests for specification errors in classical linear least-squares regression analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 1969, 31, 350–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranciere, R.; Tornell, A.; Westermann, F. Systemic crises and growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 2008, 123, 359–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. (1979). The generalisation of the general theory. In The generalisation of the general theory and other essays (pp. 1–76). Springer.

- Rünstler, G. , Balfoussia, H., Burlon, L., Buss, G., Comunale, M., De Backer, B.,... others. (2018). Real and financial cycles in EU countries: Stylised facts and modelling implications. ECB Occasional Paper.

- Sahay, M. R. , Cihak, M., N'Diaye, M. P., Barajas, M. A., Pena, M. D., Bi, R.,... others. (2015). Rethinking financial deepening: Stability and growth in emerging markets. International Monetary Fund.

- Schularick, M.; Taylor, A.M. Credit booms gone bust: monetary policy, leverage cycles, and financial crises, 1870–2008. American Economic Review 2012, 102, 1029–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schüler, Y. S. , Hiebert, P. P., & Peltonen, T. A. Financial cycles: Characterisation and real-time measurement. Journal of International Money and Finance 2020, 100, 102082. [Google Scholar]

- Schüler, Y. S. , Hiebert, P., & Peltonen, T. (2017). Coherent financial cycles for G-7 countries: Why extending credit can be an asset.

- Sharif, A.; Godil, D. I. , Xu, B., Sinha, A., Khan, S. A., & Jermsittiparsert, K. Revisiting the role of tourism and globalization in environmental degradation in China: Fresh insights from the quantile ARDL approach. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 272, 122906. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.S. Global banking glut and loan risk premium. IMF Economic Review 2012, 60, 155–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škare, M.; Porada-Rochoń, M. Forecasting financial cycles: can big data help? Technological and Economic Development of Economy 2020, 26, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiglitz, J.E. A re-examination of the Modigliani-Miller theorem. The American Economic Review 1969, 59, 784–793. [Google Scholar]

- Stremmel, H. (2015). Capturing the financial cycle in Europe. ECB Working paper.

- Swamy, V.; Dharani, M. The dynamics of finance-growth nexus in advanced economies. International Review of Economics & Finance 2019, 64, 122–146. [Google Scholar]

- Tilly, C. Trust networks in transnational migration. Sociological forum 2007, 22, pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermann, A.; Granger, C.W. Efficient market hypothesis and forecasting. International Journal of forecasting 2004, 20, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, F. Financing failure: bankruptcy lending, credit market conditions, and the financial crisis. Yale J. on Reg. 2020, 37, 651. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Merwe, E.J. (2004). Inflation targeting in South Africa. South African Reserve Bank Pretoria.

- Vercelli, A. A perspective on Minsky moments: revisiting the core of the financial instability hypothesis. Review of Political Economy 2011, 23, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villamil, A.P. The Modigliani-Miller Theorem. The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, Second Edition. Eds. Steven N. Durlauf and Lawrence E. Blume. Palgrave Macmillan 2008, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer, U. Monetary policy or macroprudential policies: What can tame the cycles? Journal of Economic Surveys 2022, 36, 1510–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F. The impact of financial development on economic growth in middle-income countries. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money 2019, 59, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, G. Debt Deflation and the Company Sector: the economic effects of balance sheet adjustment. National Institute Economic Review 1993, 144, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | First difference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-Statistic | P-value | t-Statistic | P-value | |

| CYCLE | -3.753 | 0.004 | -8.291 | 0.000 |

| EXCH | -2.541 | 0.107 | -14.025 | 0.000 |

| GDP | -2.831 | 0.055 | -5.841 | 0.000 |

| INF | -2.664 | 0.082 | -6.575 | 0.000 |

| CR | -1.847 | 0.357 | -6.679 | 0.000 |

| HP | -1.927 | 0.320 | -2.818 | 0.057 |

| SHARE | -13.707 | 0.000 | -12.163 | 0.000 |

| M3 | 3.148 | 1.000 | -7.039 | 0.000 |

| Repo | -2.876 | 0.049 | -5.166 | 0.000 |

| MPI | -1.109 | 0.711 | -9.476 | 0.000 |

| Long-run quantile ARDL results | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T | Exch | GDP | INF | CR | HP | SP | M3 | REPO | MPI |

| 0.1 | -0.022** | -0.022 | -0.002*** | -0.002*** | 0.001*** | -0.024* | -0.060*** | 0.020*** | -0.027 |

| 0.2 | -0.024*** | -0.050** | -0.002*** | -0.002*** | 0.001*** | -0.028*** | -0.059*** | 0.022*** | -0.024 |

| 0.3 | -0.024*** | -0.044** | -0.002*** | -0.002*** | 0.001*** | -0.032*** | -0.054*** | 0.0256*** | -0.022 |

| 0.4 | -0.024*** | -0.044** | -0.002*** | -0.002*** | 0.001*** | -0.032** | -0.054*** | 0.026*** | -0.022 |

| 0.5 | -0.024*** | -0.044** | -0.002*** | -0.002*** | 0.001*** | -0.032** | -0.054*** | 0.0256*** | -0.022 |

| 0.6 | -0.024*** | -0.035* | -0.001*** | -0.003*** | 0.002*** | -0.001*** | -0.062*** | 0.039*** | -0.085*** |

| 0.7 | -0.026*** | -0.036* | -0.001*** | -0.003*** | 0.002*** | -0.001*** | -0.060*** | 0.037*** | -0.075*** |

| 0.8 | -0.022*** | -0.041* | -0.001** | -0.003*** | 0.001 | -0.001*** | -0.049*** | 0.037*** | -0.054** |

| 0.9 | -0.018 | -0.082 | -0.001** | -0.003*** | 0.001 | -0.001*** | -0.057** | 0.036*** | -0.056*** |

| Short-run quantile ARDL results | |||||||||

| T | Exch | GDP | INF | CR | HP | SP | M3 | REPO | MPI |

| 0.1 | -8.38E-05 | 0.022 | -0.014* | 0.060*** | -0.034*** | 0.005*** | -0.007 | 0.006 | -0.052 |

| 0.2 | -0.011*** | 0.047 | -0.017*** | 0.060*** | -0.032*** | 0.005*** | -0.005 | 0.013 | -0.057** |

| 0.3 | -0.010 | 0.047 | -0.017*** | 0.060*** | -0.026*** | 0.005*** | -0.005 | 0.017 | -0.063** |

| 0.4 | -0.010** | 0.047 | -0.017*** | 0.060*** | -0.026*** | 0.005*** | -0.005 | 0.017 | -0.063** |

| 0.5 | -0.010** | 0.0467 | -0.017*** | 0.060*** | -0.026*** | 0.005*** | -0.005 | 0.017 | -0.063** |

| 0.6 | -0.013* | -0.069 | -0.008** | 0.060*** | -0.018*** | 0.005*** | -0.005* | 0.006 | -0.064*** |

| 0.7 | -0.012* | 0.026 | -0.008* | 0.060*** | -0.018*** | 0.005*** | -0.056* | 0.004 | -0.001*** |

| 0.8 | -9.76E-05 | -0.012 | -0.004 | 0.060*** | -0.015** | 0.005*** | -0.038 | 0.001 | -0.008 |

| 0.9 | -5.63E-05 | -0.035 | -0.001 | 0.060*** | -0.022*** | 0.005*** | -0.024 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Bounds Test F-Stats | 72.265*** | ||||||||

| Breusch-Pagan-Godfrey Heteroscedasticity F- Stats | 1.265 | ||||||||

| Breusch-Godfrey LM F-Stats | 38.079*** | ||||||||

| T Wald Test F-Stats | 9.194 | ||||||||

| Ramsey Test F-Stats | 10.011*** | ||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).