Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

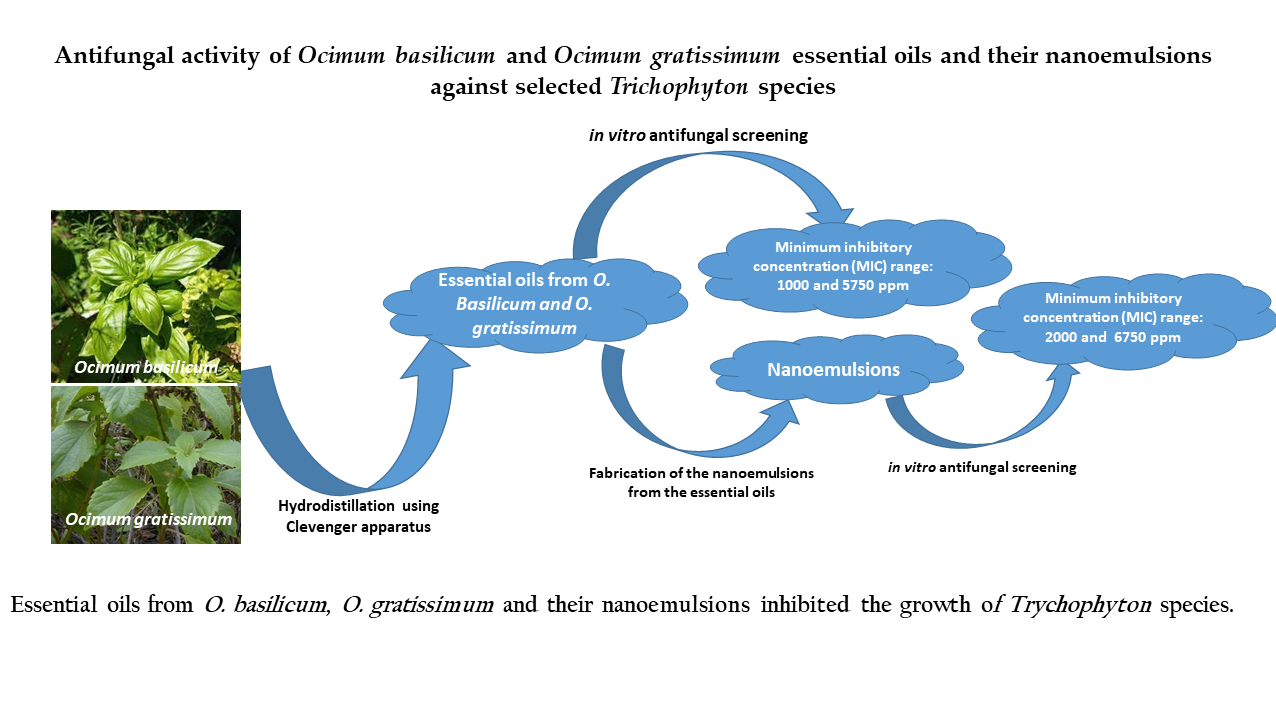

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Results

2.1.1. Yields of Extraction

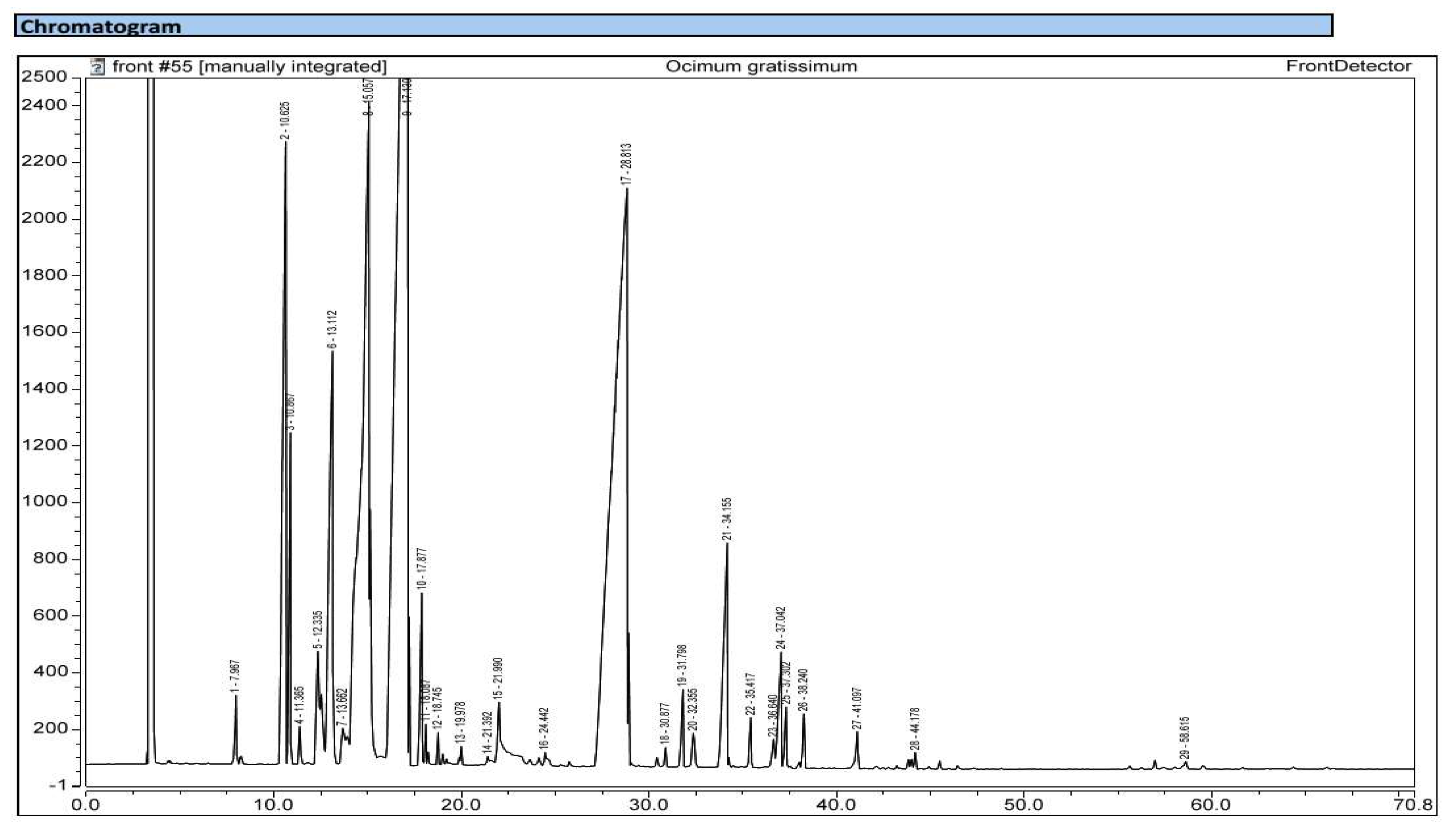

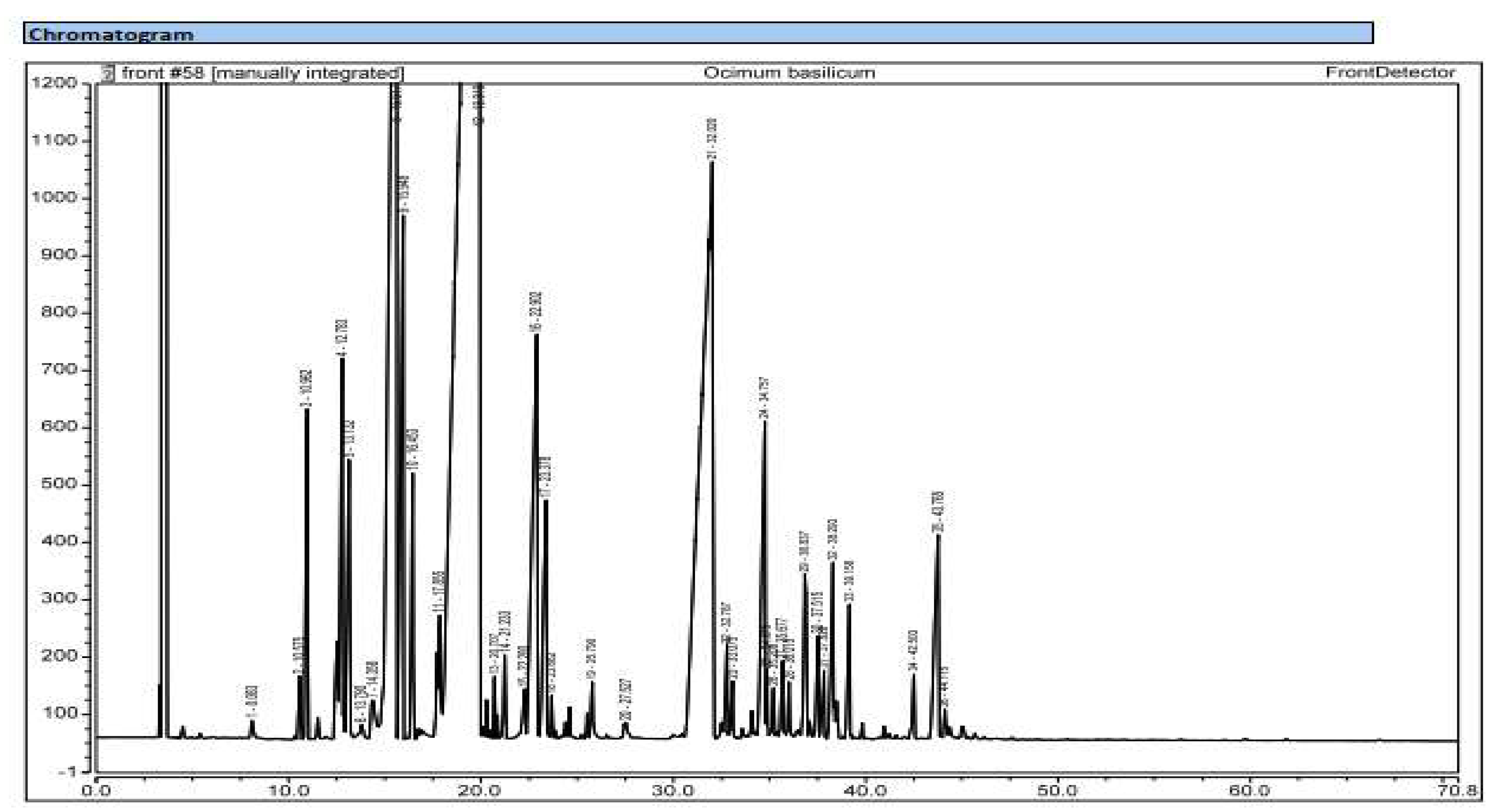

2.1.2. Chemical Composition of the Essential Oils

2.1.3. Characterization of the Nanoemulsions

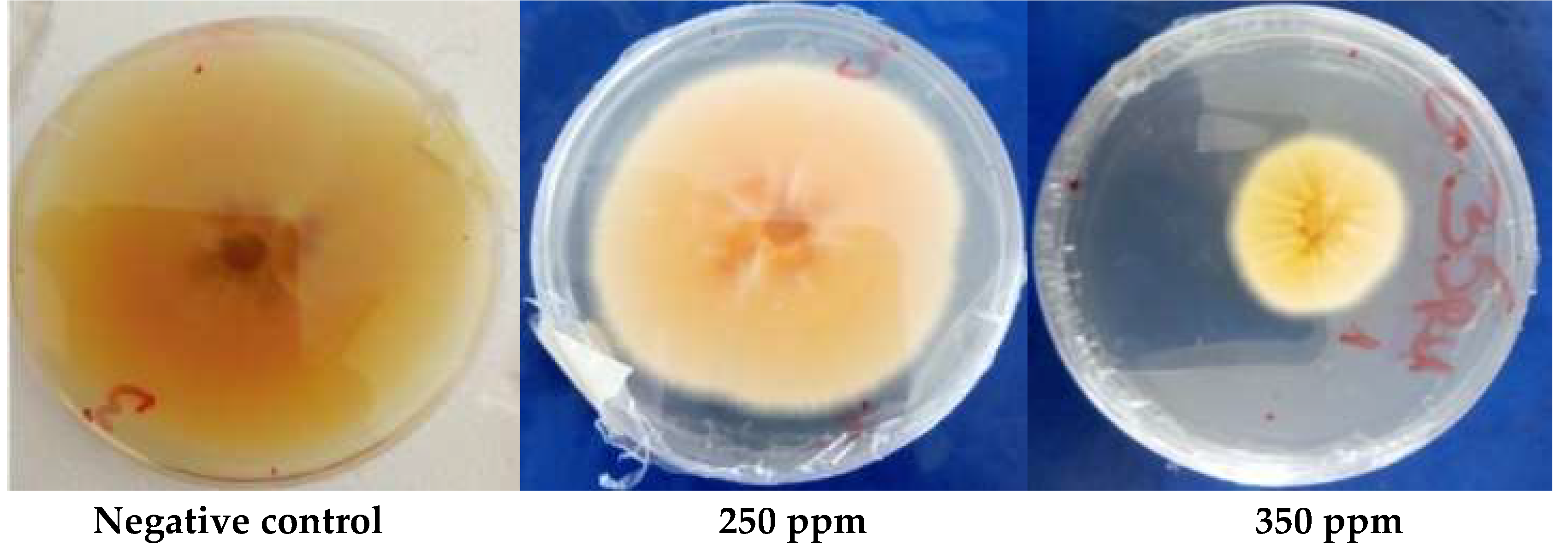

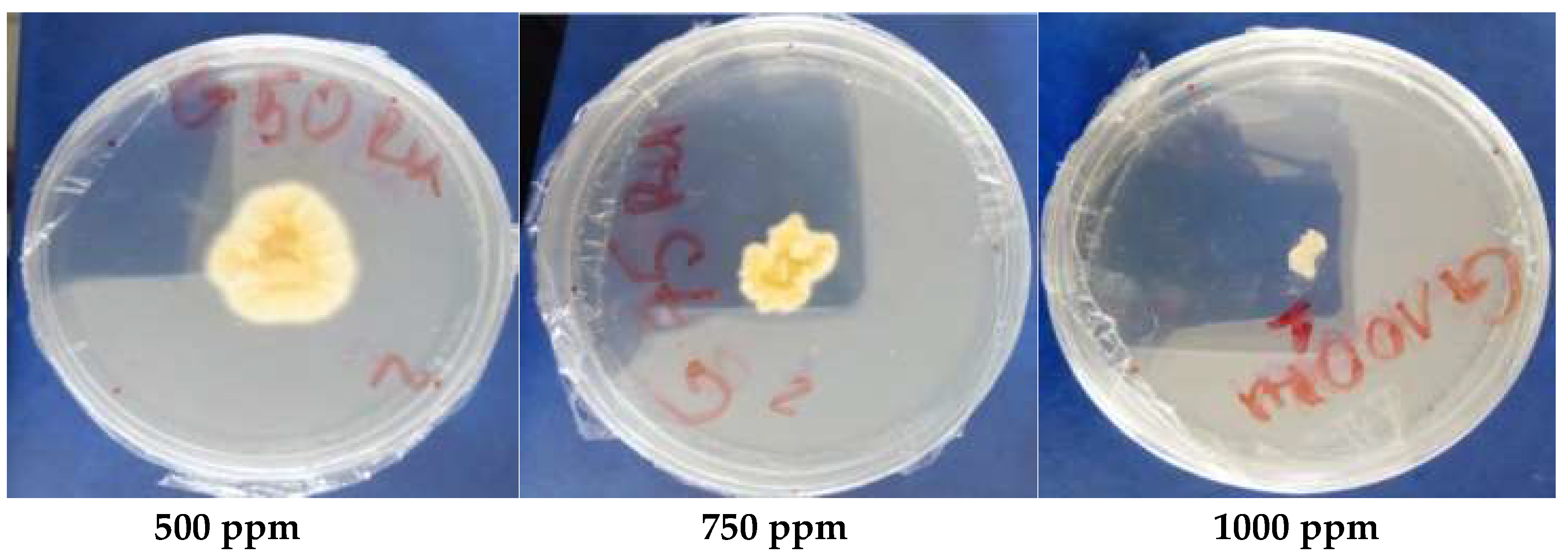

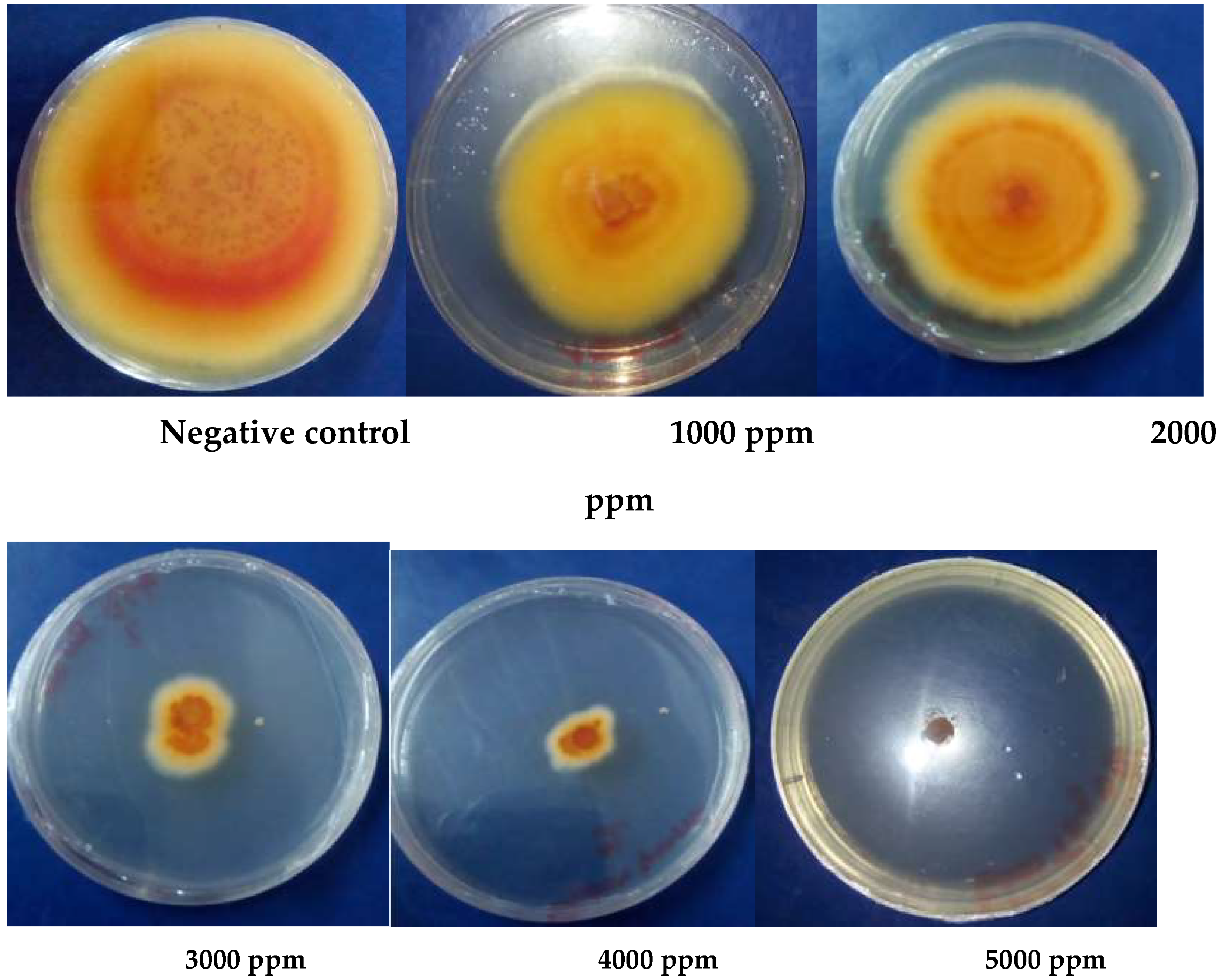

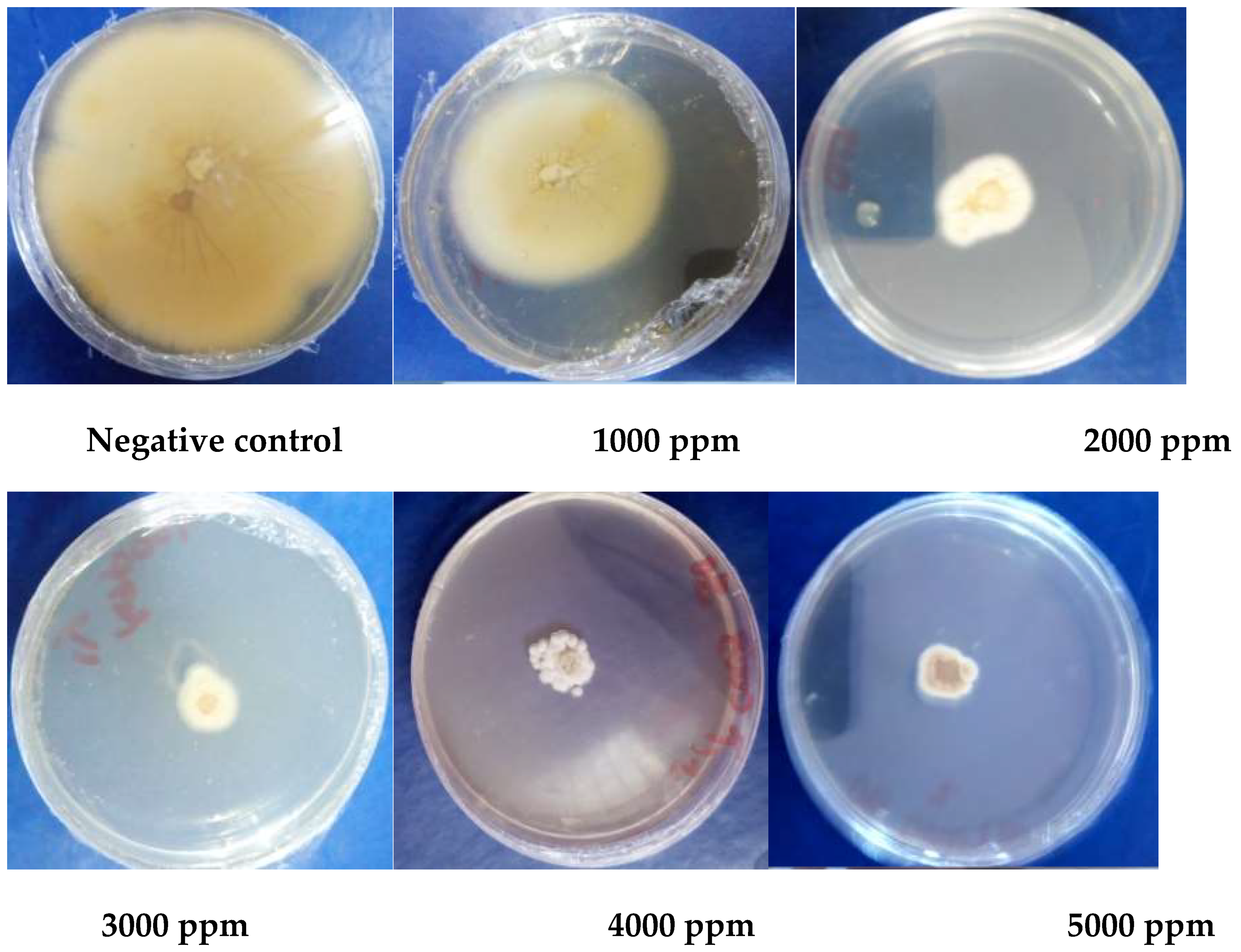

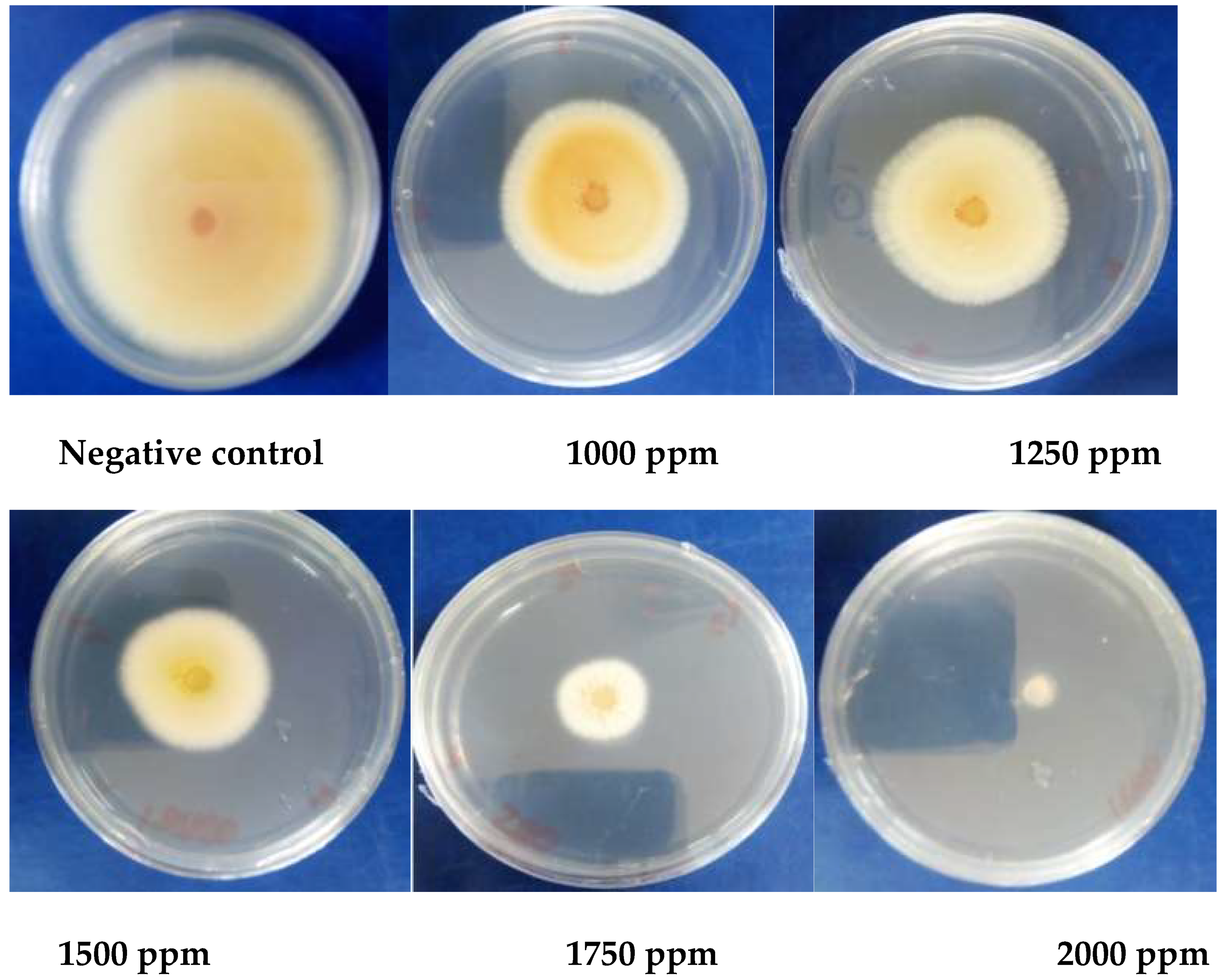

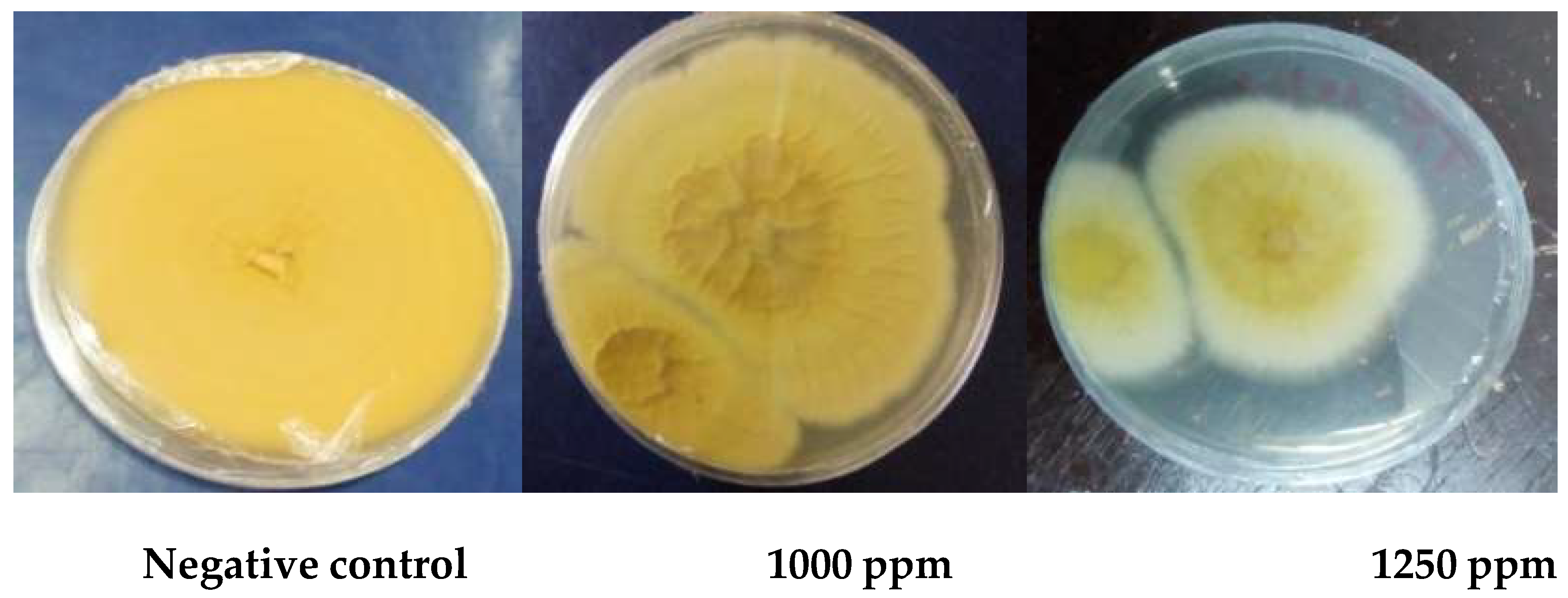

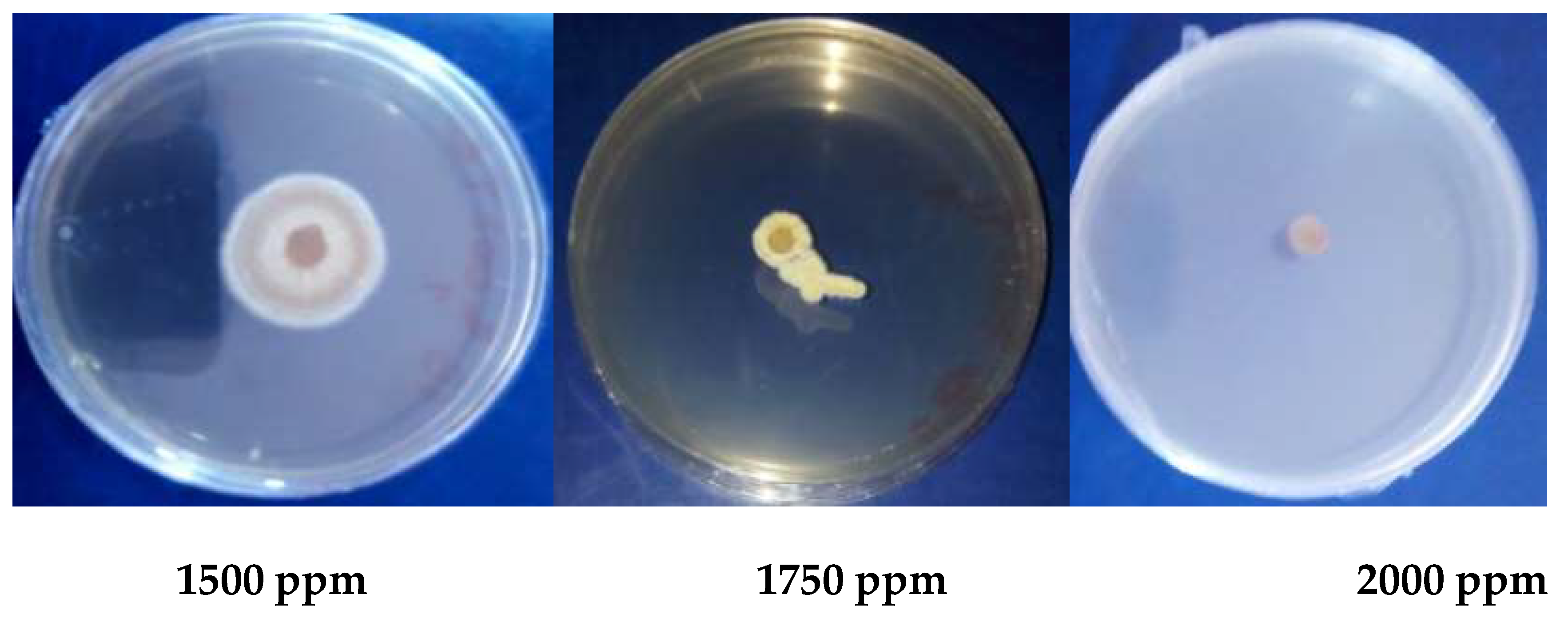

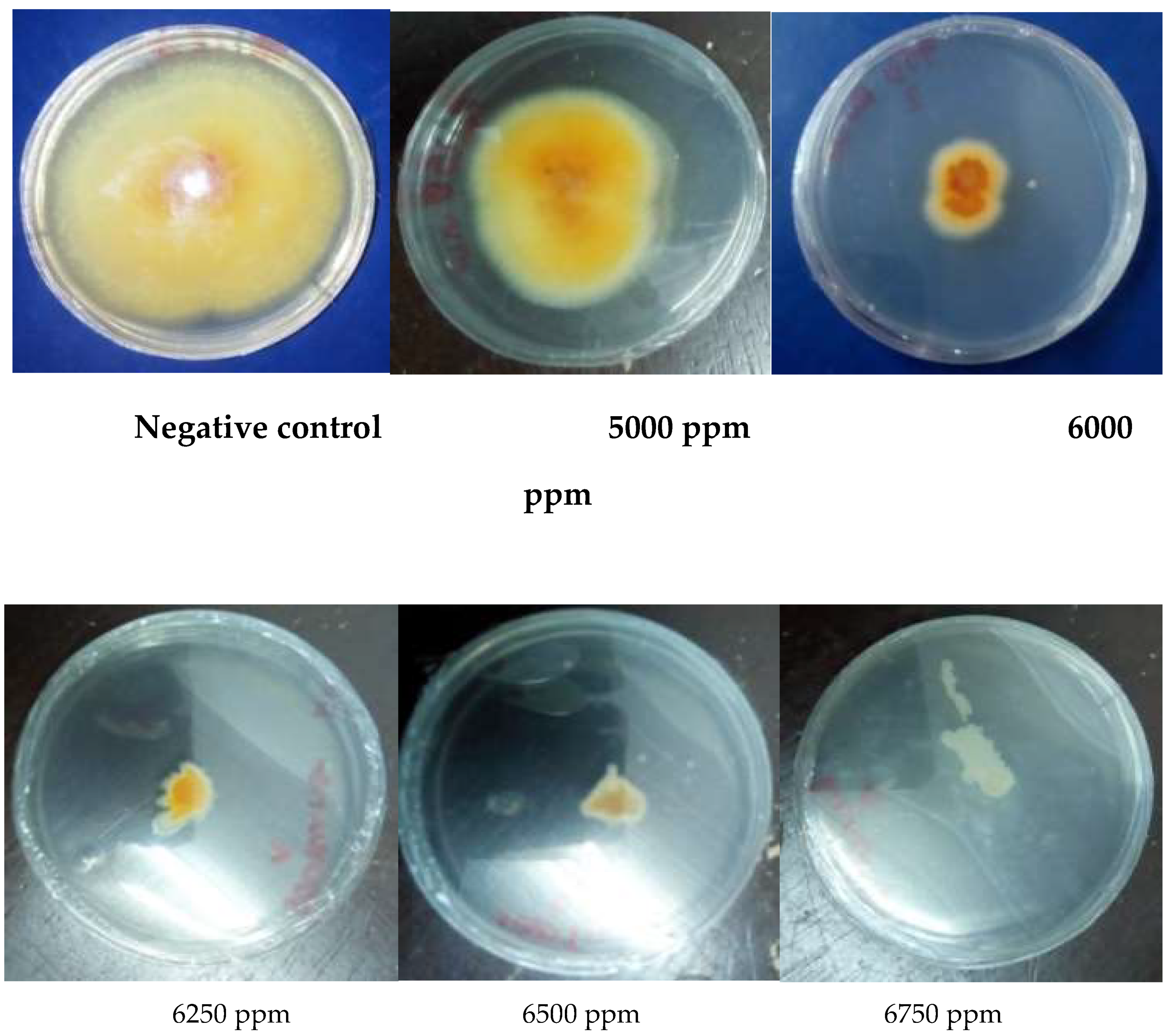

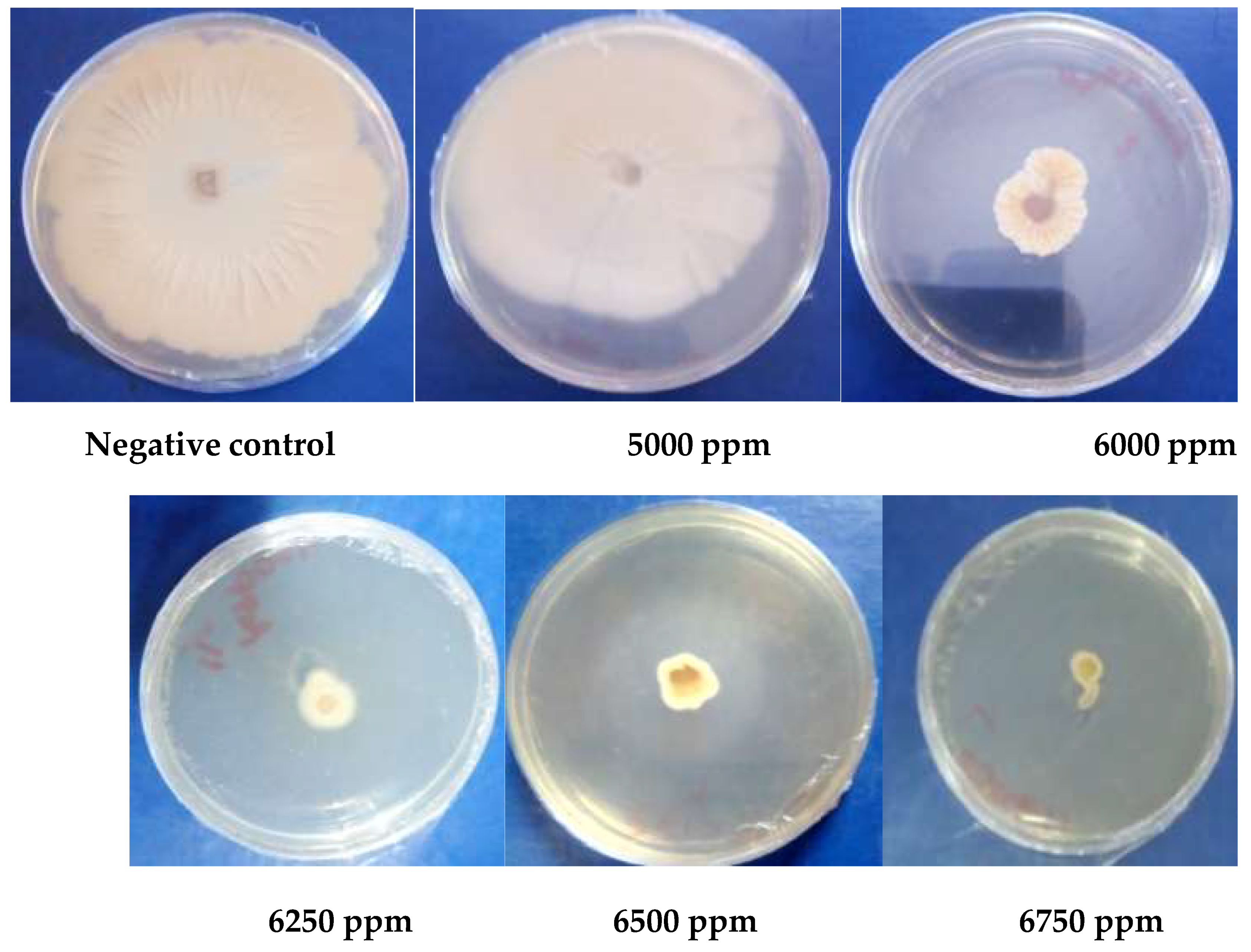

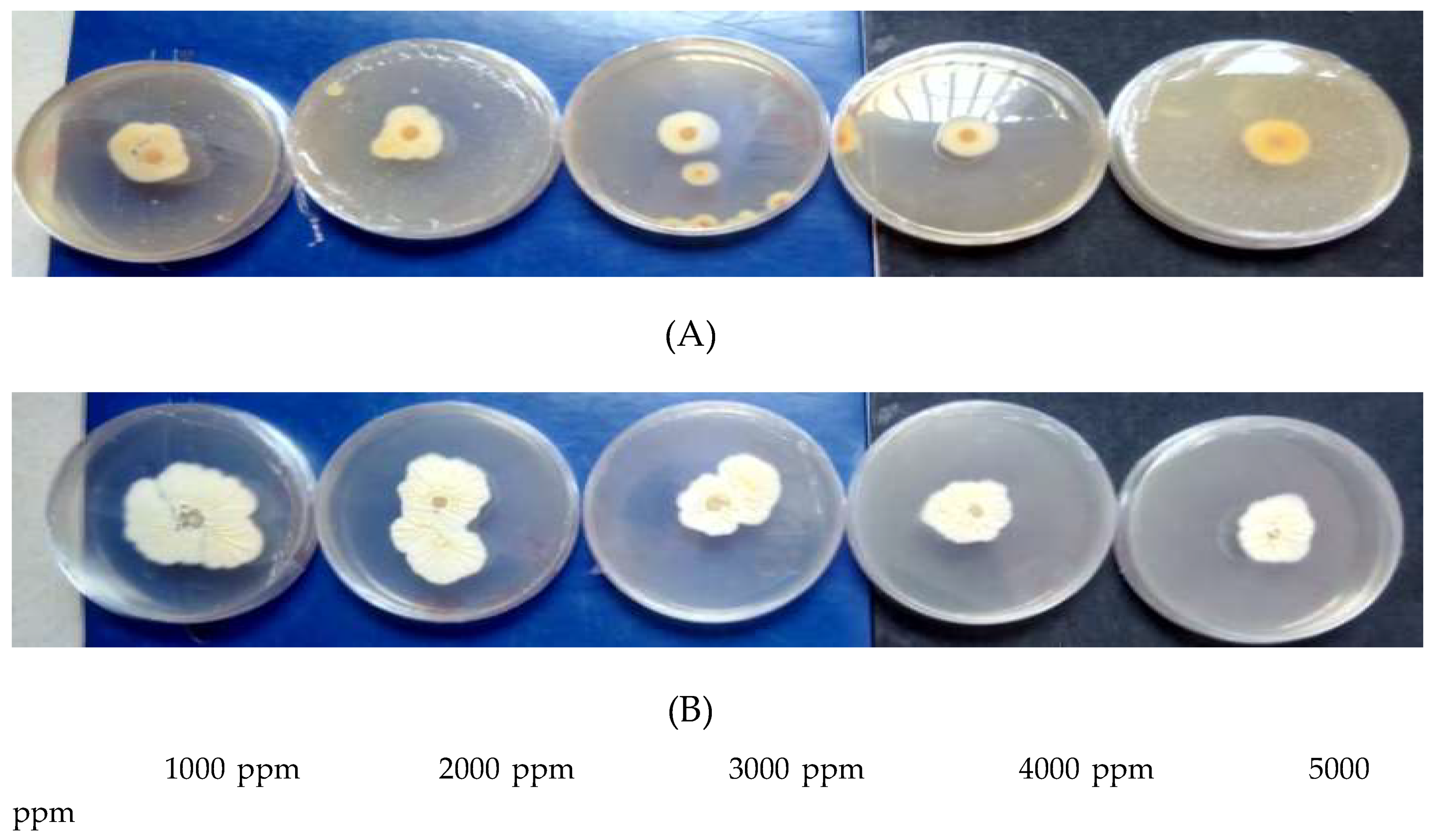

2.1.4. In Vitro Antifungal Activity

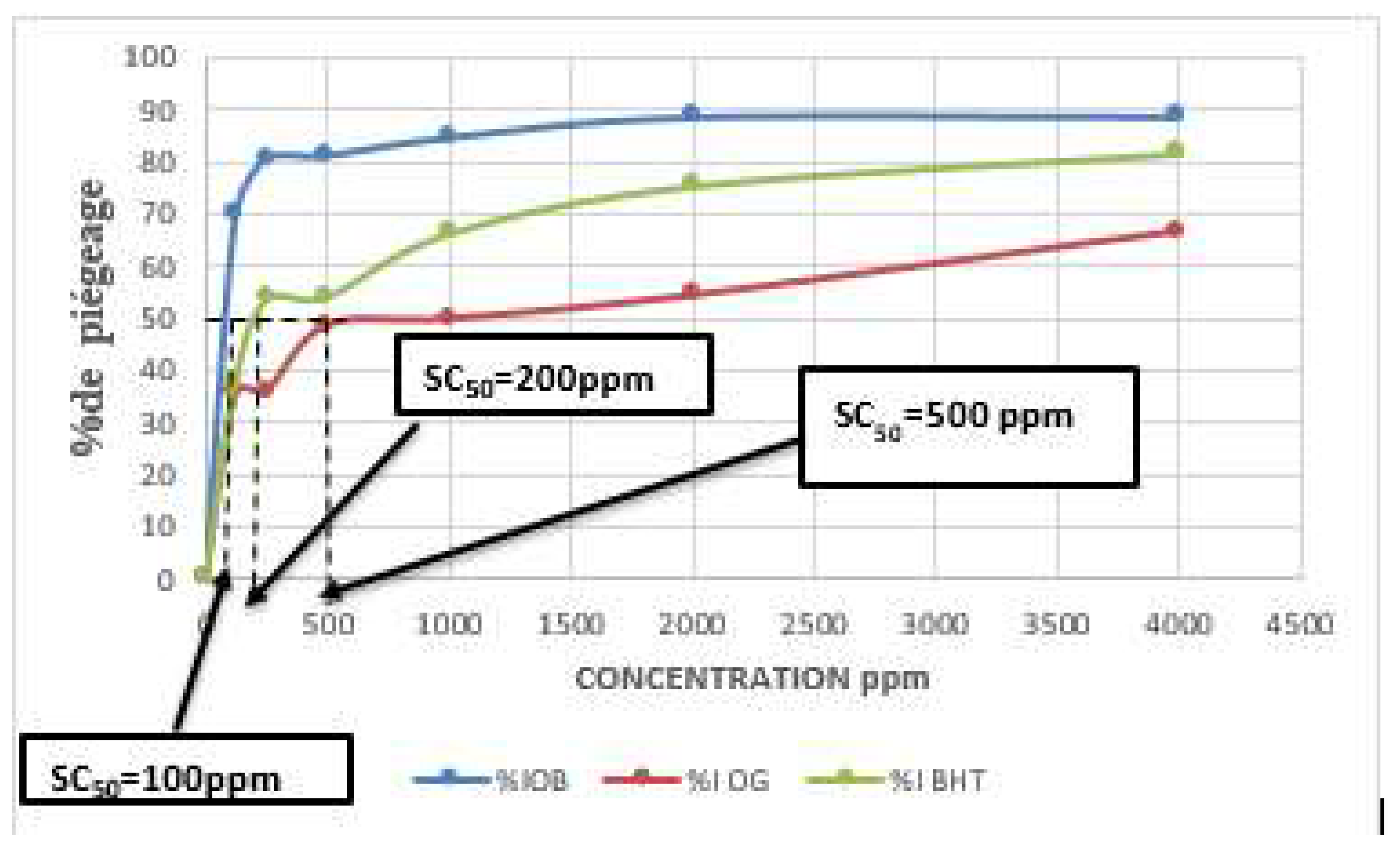

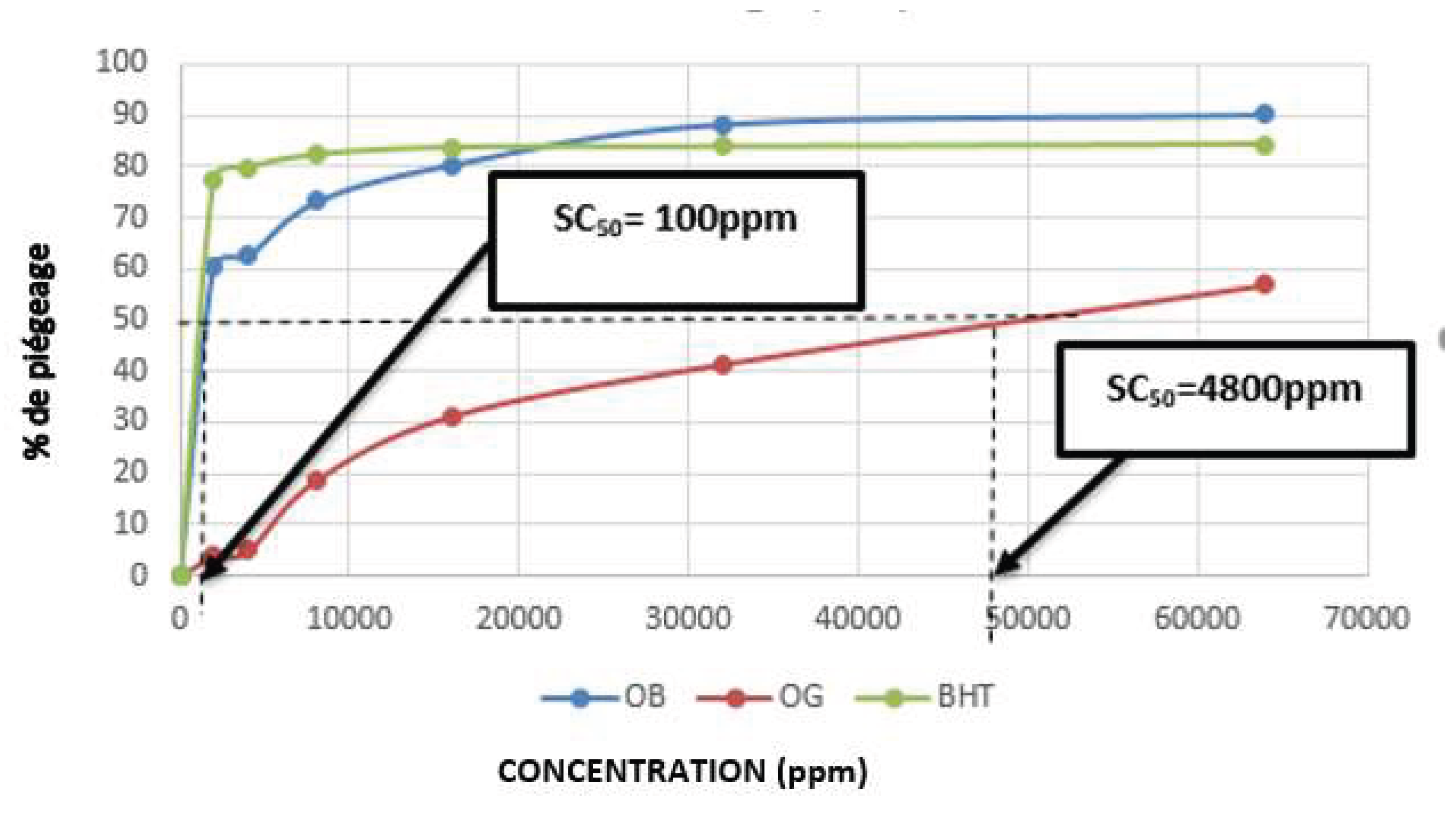

3.1.5. Antioxidant Activity

2.2. Discussion

3. Conclusions

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Material

3.1.1. Plant Material

3.1.2. Fungal Strains

3.1.3. Material for Fungal Cell Culture

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Extraction of the Essential Oils

3.2.2. GC-MS Analysis of Essential Oil of Ocimum Gratissimum and Ocimum basilicum

3.2.3. Preparation of the Nanoemulsions

3.2.4. Characterization of the Nanoemulsions

3.2.5. Antidermatophytic Assay

3.3. Statistical Analysis of Data

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith MB, McGinnis MR. Tropical Infectious Diseases: Principles, Pathogens and Practice (Third Edition) 2011, Pages 559-564. [CrossRef]

- Jartarkar SR, Patil A, Goldust Y, Cockerell CJ, Schwartz RA, Grabbe S, Goldust M. Pathogenesis, immunology and management of dermatophytosis. J Fungi (Basel) 2021 ; 8(1): 39. [CrossRef]

- Belmokhtar Z, Djaroud S, Matmour D, Merad Y. Atypical and unpredictable superficial mycosis presentations: A narrative review. J Fungi (Basel) 2024 ; 10(4) 295. [CrossRef]

- Denning, DW. Global incidence and mortality of severe fungal disease. Lancet Infect Dis 2024 ; 24 (7) : e428-e438.

- Chanyachailert P, Leeyaphan C, Bunyaratavej S. Cutaneous fungal infections caused by dermatophytes and non-dermatophytes: An updated comprehensive review of epidemiology, clinical presentations, and diagnostic testing. J Fungi (Basel) 2023 ; 9(6) : 669. [CrossRef]

- Stajich, JE. Fungal genomes and insights into the evolution of the kingdom. Microbiol Spectr 2017 ; 5(4) : 10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0055-2016.

- Gupta C, Das S, Gaurav V, Singh PK, Rai G, Datt S, Tigga RA, Pandhi D, Bhattacharya SN, Ansari MA, Dar SA. Review on host-pathogen interaction in dermatophyte infections. Med Mycol J 2023 ; 33 (1) : 101331. [CrossRef]

- Sonego B, Corio A, Mazzoletti V, Zerbato V, Benini A, di Meo N, Zalaudek I, Stinco G, Errichetti E, Zelin E. Trichophyton indotineae, an emerging drug-resistant dermatophyte : A review of the treatment options. J Clin Med 2024; 13 (12) 3558. [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organization (WHO, 2024). Traditional medicine has a long history of contributing to conventional medicine and continues to hold promise. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/traditional-medicine-has-a-long-history-of-contributing-to-conventional-medicine-and-continues-to-hold-promise#:~:text=For%20centuries%20across%20countries%2C%20people,traditional%20medicine%20by%20their%20populations., Accessed on 31st October 2024.

- Kpodekon M, Boko C, Mainil J, Farougou S, Sessou P, Yehouenou B, Gbenou J, Duprez J-N ; Bardiau M. « Composition chimique et test d’efficacité in vitro des huiles essentielles extraites de feuilles fraîches du basilic commun (Ocimum basilicum) et du basilic tropical (Ocimum gratissimum) sur Salmonella enterica sérotype Oakland et Salmonella enterica sérotype Legon » J Soc Ouest-Afr Chim 2013 ; 35 : 41–48.

- Zhakipbekov K, Turgumbayeva A, Akhelova S, Bekmuratova K, Blinova O, Utegenova G, Shertaeva K, Sadykov N, Tastambek K, Saginbazarova A, Urazgaliyev K, Tulegenova G, Zhalimova Z, Karasova Z. Antimicrobial and other pharmacological properties of Ocimum basilicum, Lamiaceae. Molecules 2024 ; 29(2) : 388. [CrossRef]

- Thakur P, Chawla R, Chakotiya AS, Tanwar A, Goel R, Narula A, Arora R, Sharma RK. Camellia sinensis ameliorates the efficacy of last line antibiotics against carbapenem resistant Escherichia coli. Phytother Res 2016 ; 30 : 314-322.

- Kpadonou Kpoviessi BG, Kpoviessi SD, Yayi Ladekan E, Gbaguidi F, Frédérich M, Moudachirou M, Quetin-Leclercq J, Accrombessi GC, Bero J. 2014. In vitro antitrypanosomal and antiplasmodial activities of crude extracts and essential oils of Ocimum gratissimum Linn from Benin and influence of vegetative stage. J Ethnopharmacol 2014 ; 155 (3) 1417-23.

- Ugbogu OC, Emmanuel O, Agi GO, Ibe C, Ekweogu CN, Ude VC, Uche ME, Nnanna RO, Ugbogu EA. A review on the traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological activities of clove basil (Ocimum gratissimum L.). Heliyon 2021 ; 7(11) e08404. [CrossRef]

- Aminian AR, Mohebbati R, Boskabady MH. The effect of Ocimum basilicum L. and its main ingredients on respiratory disorders: An experimental, preclinical, and clinical review. Front Pharmacol 2022 ; 12 : 805391. [CrossRef]

- Azizah NS, Irawan B, Kusmoro J, Safriansyah W, Farabi K, Oktavia D, Doni F, Miranti, M. Sweet Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.)-A review of its botany, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, and biotechnological development. Plants (Basel) 2023 ; 12(24) : 4148. [CrossRef]

- Chukwuma IF, Uchendu NO, Asomadu RO, Ezeorba WFC, Prince T, Ezeorba C. African and Holy Basil-a review of ethnobotany, phytochemistry, and toxicity of their essential oil: Current trends and prospects for antimicrobial/antiparasitic pharmacology. Arab J Chem 2023 ; 16 (7) : 104870. [CrossRef]

- Angu TC, Ngwasiri PN, Navti LK, Yimta Y, Angaba FFA. Preservation potentials of essential oils of Ocimum basilicum and Ocimum gratissimum from two agro-ecological zones on freshwater smoke-dried Oreochromis niloticus fish sold in some Local Markets in Cameroon. Adv Biol Chem 2023 ; 13 : 5. [CrossRef]

- Małgorzata N, Katarzyna G. 2016. Antibacterial activity of Ocimum basilicum L. essential oil against Gram-negative bacteria. Postępy Fitoterapii 2016 ; 17 (2) : 80-6.

- Araújo Silva V, Pereira da Sousa J, de Luna Freire Pessôa H, Fernanda Ramos de Freitas A, Douglas Melo Coutinho, H, Beuttenmuller Nogueira Alves L, Oliveira Lima E. 2016. Ocimum basilicum : Antibacterial activity and association study with antibiotics against bacteria of clinical importance. Pharm Biol 2016 ; 54(5) 863-7.

- Mahendran G, Vimolmangkang S. Chemical compositions, antioxidant, antimicrobial, and mosquito larvicidal activity of Ocimum americanum L. and Ocimum basilicum L. leaf essential oils. BMC Complement Med Ther 2023 ; 23 (1) 390. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura CV, Ueda-Nakamura T, Bando E, Melo AFN, Cortez DAG, Filho BPD. Antibacterial activity of Ocimum gratissimum L. essential oil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 1999 ; 94 (5) 675-8.

- Amengialue OO, Edobor O, Egharevba AP. 2013. Antibacterial activity of extracts of Ocimum gratissimum on bacteria associated with diarrhoea. BAJOPAS 2013 ; 6(2) : 143-5.

- Melo RS, Albuquerque Azevedo ÁM, Gomes Pereira AM, Rocha RR, Bastos Cavalcante RM, Carneiro Matos MN, Ribeiro Lopes PH, Gomes GA, Soares Rodrigues, TH, Santos HSD, Ponte IL, Costa RA, Brito GS, Catunda Júnior FEA, Carneiro VA. Chemical composition and antimicrobial effectiveness of Ocimum gratissimum L. essential oil against multidrug-resistant isolates of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Molecules 2019 ; 24(21) : 3864. [CrossRef]

- Onaebi C, Onyeke C, Osibe D, Ugwuja F, Okoro A, Onyegirim P. Antimicrobial activity of Ocimum gratissimum L. and Carica papaya L. against postharvest pathogens of avocado pear (Persea americana Mill.). Plant Pathol J 2020 ; 102 : 319–25.

- Xie Y, Zhang C, Mei J, Xie J. Antimicrobial effect of Ocimum gratissimum L. essential oil on Shewanella putrefaciens : Insights based on the cell membrane and external structure. Int J Mol Sci 2023 ; 24(13) 11066. [CrossRef]

- Silva JC, Pereira RLS, de Freitas TS, Rocha JE, Macedo NS, Nonato C de FA, Linhares ML, Tavares DSA, da Cunha FAB, Coutinho HDM, de Lima SG, Pereira-Junior FN, Maia FPA, Neto ICP, Rodrigues FFG, Santos GJG. Evaluation of antibacterial and toxicological activities of essential oil of Ocimum gratissimum L. and its major constituent eugenol. Food Biosci 2022 ; 50 : Part B, 102128. [CrossRef]

- Sharma S, Rolta R, Salaria D, Dev K. In vitro antibacterial and antifungal potentials of Ocimum tenuiflorum and Ocimum gratissimum essential oil. Pharmacological Research - Natural Products. 2024 ; Volume 4, 100065. [CrossRef]

- Hao PM, Quoc Le PT. Chemical profile and antimicrobial activity of Ocimum gratissimum L. essential oil from Dak Lak province, Vietnam. J Plant Biotechnol 2024 ; 51: 50-4. [CrossRef]

- Mohr FB, Lermen C, Gazim ZC, Gonçalves JE, Alberton O. Antifungal activity, yield, and composition of Ocimum gratissimum essential oil. Genet Mol Res 2017 ; 16 (1). [CrossRef]

- Akpo AF, Silué Y, Nindjin C, Tano K, Kouamé KA, Tetchi FA, Lopez-Laur F, In vitro antifungal activity of aqueous extract and essential oil of African basil (Ocimum gratissimum L.). NAJFNR, 2023 ; 7 (16) 136-45.

- Prabhu KS, Lobo R, Shirwaikar AA, Shirwaikar A. Ocimum gratissimum : A review of its chemical, pharmacological and ethnomedicinal properties. Open Complement Med J 2009 ; 1: 1-15.

- Nakamura CV, Ishida K, Faccin LC, Filho BPD, Diógenes AG, Cortez DAG, Rozental S, de Souza W, Ueda-Nakamura. In vitro activity of essential oil from Ocimum gratissimum L. against four Candida species. Research in Microbiology 2004 ; 155, 579-86.

- Fokou JBH, Dongmo PMJ, Boyom FF, Menkem EZ, Bakargna-Via I, Tsague IFK, Marguerite SK, Paul Henri AZ, Chantal M. Antioxidant and antifungal activities of the essential oils of Ocimum gratissimum from Yaoundé and Dschang (Cameroon). J Pharm Pharmacol 2014 ; 2 : 257-68.

- Pandey, S. Antibacterial and antifungal activities of Ocimum gratissimum L. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci 2017; 9 (12) : 26-31.

- Lambers H, Piessens S, Bloem A, Pronk H, Finkel P. Natural skin surface pH is on average below 5, which is beneficial for its resident flora. Int J Cosmet Sci 2006 ; 28 (5) : 359-70.

- Nguyen NNT, Nguyen TTD, Vo DL, Than DTM, Tien GP, Pham DT. Microemulsion-based topical hydrogels containing lemongrass leaf essential oil (Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf) and mango seed kernel extract (Mangifera indica Linn) for acne treatment : Preparation and in-vitro evaluations. PLoS One 2024 ; 19 (10) : e0312841. [CrossRef]

- Jeon JM, Park SJ, Choi TR, Park JH, Yoon JJ. Biodegradation of polyethylene and polypropylene by Lysinibacillus species JJY0216 isolated from soil grove. Polym Degrad Stab 2021 ; 191 (2021), Article 109662.

- Boothe WD, Tarbox JA, Tarbox MB. Atopic dermatitis : Pathophysiology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2024 ; 1447, 21-35.

- Firacative, C. Invasive fungal disease in humans : are we aware of the real impact? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 2020 ; 115 : e200430. [CrossRef]

- Fisher MC, Gurr SJ, Cuomo CA, Blehert DS, Jin H, Stukenbrock EH, Stajich JE, Kahmann R, Boone C, Denning DW, Gow NAR, Klein BS, Kronstad JW, Sheppard DC, Taylor JW, Wright GD, Heitman J, Casadevall A, Cowen LE. Threats posed by the fungal kingdom to humans, wildlife, and agriculture. mBio 2020 ;11(3): e00449-20. [CrossRef]

- Loh JT, Lam KP. Fungal infections : Immune defense, immunotherapies and vaccines. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2023 ; 196: 114775. [CrossRef]

- Osset-Trénor P, Pascual-Ahuir A, Proft M. 2023. Fungal drug response and antimicrobial resistance. J Fungi (Basel) 2023 ; 9(5) : 565. [CrossRef]

- Kruithoff C, Gamal A, McCormick TS, Ghannoum MA. Dermatophyte infections worldwide : Increase in incidence and associated antifungal resistance. Life (Basel). 2023 ; 14(1): 1. [CrossRef]

- Aschale Y, Wubetu M, Abebaw A, Yirga T, Minwuyelet A, Toru M. A systematic review on traditional medicinal plants used for the treatment of viral and fungal infections in Ethiopia. J Exp Pharmacol 2021 ; 13 : 807-15.

- Mei A, Ricciardo B, Raby E, Kumarasinghe SP. Plant-based therapies for dermatophyte infections. Tasman Med Journal 2022 ; 3 : 21-37.

- Chanthaboury M, Choonharuangdej S, Shrestha B, Srithavaj T. Antimicrobial properties of Ocimum species : An in vitro study. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 2022 ; 12 (6) : 596-602.

- Okoye FBC, Obonga WO, Onyegbule FA, Ndu OO, Ihekwereme CP. 2014. Chemical composition and anti-inflammatory activity of essential oils from The leaves of Ocimum basilicum L. and Ocimum gratissimum L. (Lamiaceae). Int J Pharm Sci Res 2014 ; 5 (6) : 2174-80.

- Dossoukpevi, R., Ahanhanzo, C., Gbaguidi, F., Agbangla, C., Agbidinoukoun, A., Cacai, G., 1997. « Incidence des plantes régénérées in vitro sur les huiles essentielles de deux espèces de Ocimum cultvées au Bénin. » Journal of Applied Biosciences 99, 9441-9449.

- Saliu BK, Usman LA, Sani A, Muhammad NO, Akolade JO. Chemical composition and antibacterial (oral isolates) activity of leaf essential oil of Ocimum gratissimum L. grown in north central Nigeria. Int J Curr Res 2011; 33: 22–28.

- Khalid AK, El-Gohary AE. Effect of seasonal variations on essential oil production and composition of Plectranthus amboinicus (Lour.) grow in Egypt. Int Food Res J 2014 ; 21(5) 1859-62.

- Tchoumbougnang F, Jazet DPM, Sameza ML, Mbanjo EGN, Fotso GBT, Amvam-Zollo PH, Menut C. « Activité larvicide sur Anopheles gambiae Giles et composition chimique des huiles essentielles extraites de quatre plantes cultivées au Cameroun ». Biotechnology, Agronomy, Society and Environment 2009 ; 13 (1) : 77-84.

- Agnaniet A, Mounzeo H, Menut C, Bessiere JM, Criton M. The essential oils of Rinorea subintegrifolia O ktze and Drypetes gosweileri S Moore occurring in Gabon. Flavour Fragr J 2003 ; 18 (3):207–10.

- Tursun, AO. 2022. Impact of soil types on chemical composition of essential oil of purple basil. Saudi J Biol Sci 2022 ; 29(7) : 103314. [CrossRef]

- Hoch CC, Petry J, Griesbaum L, Weiser T, Werner K, Ploch M, Verschoor A, Multhoff G, Bashiri Dezfouli A, Wollenberg B. 2023. 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) : A versatile phytochemical with therapeutic applications across multiple diseases. Biomed Pharmacother 2023 ; 167 : 115467. [CrossRef]

- Ghazi Mirsaid, R., Falahati, M., Farahyar, S., Ghasemi, Z., Roudbary, M., Mahmoudi, S., 2024. In vitro antifungal activity of eucalyptol and its interaction with antifungal drugs against clinical dermatophyte isolates including Trichophyton indotineae. Discover Public Health 21, 73. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Pereira, F., Mendes, J.M., de Oliveira Lima, E., 2013. Investigation on mechanism of antifungal activity of eugenol against Trichophyton rubrum. Med Mycol J 2013 ; 51 (5) : 507-13.

- de Oliveira Lima MI, Araújo de Medeiros AC, Souza Silva KV, Cardoso GN, de Oliveira Lima E, de Oliveira Pereira F. Investigation of the antifungal potential of linalool against clinical isolates of fluconazole resistant Trichophyton rubrum. Med Mycol J 2017 ; 27 (2) : 195-202.

- Aliabasi S, Shams-Ghahfarokhi M, Razzaghi-Abyaneh M. 2023. Eugenol effectively inhibits Trichophyton rubrum growth via affecting ergosterol synthesis, keratinase activity, and SUB3 gene expression. J Herb Med 2023 ; 42 :100768. [CrossRef]

- Medeiros CIS, Sousa MNA, Filho GGA, Freitas FOR, Uchoa DPL, Nobre MSC, Bezerra ALD, Rolim LADMM, Morais AMB, Nogueira TBSS, Nogueira RBSS, Filho AAO, Lima EO. Antifungal activity of linalool against fluconazole-resistant clinical strains of vulvovaginal Candida albicans and its predictive mechanism of action. Braz J Med Biol Res 2022 ; 5 : e11831. [CrossRef]

- Shahina Z, Al Homsi R, Price JDW, Whiteway M, Sultana T, Dahms TES. Rosemary essential oil and its components 1,8-cineole and α-pinene induce ROS-dependent lethality and ROS-independent virulence inhibition in Candida albicans. PLoS ONE 2022 ; 17 : e0277097. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy R, Gassem MA, Athinarayanan J, Periyasamy VS, Prasad S, Alshatwi AA. Antifungal activity of nanoemulsion from Cleome viscosa essential oil against food-borne pathogenic Candida albicans. Saudi J Biol Sci 2021 ; 28 (1) : 286-93.

- Donsi F, Sessa M, Ferrari G. Nanoencapsulation of essential oils to enhance their antimicrobial activity in foods. LWT-Food Sci Technol 2011 ; 44 (9) : 1908-14.

- Gülçin, İ. Antioxidant activity of eugenol : a structure-activity relationship study. Journal of Medicinal Food 2011 ; 14 (9) : 975-85.

- Mahizan NA, Yang SK, Moo CL, Song AA, Chong CM, Chong CW, Abushelaibi A, Lim SE, Lai KS. Terpene derivatives as a potential agent against antimicrobial resistance (AMR) pathogens. Molecules 2019 ; 24 : 2631. [CrossRef]

- Arbab IA, Abdul AB, Aspollah M, Abdullah R, Abdelwahab SI, Ibrahim MY, Ali LZ. A review of traditional uses, phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of selected members of Clausena genus (Rutaceae). J Med Plants Res 2012 ; 6 : 5107–18.

- da Silva LYS, Paulo CLR, Moura TF, Alves DS, Pessoa RT, Araújo IM, de Morais Oliveira-Tintino CD, Tintino SR, Nonato CdFA, da Costa JGM, Ribeiro-Filho J, Coutinho HDM, Kowalska G, Mitura P, Bar M, Kowalski R, Menezes IRAd. Antibacterial activity of the essential oil of Piper tuberculatum Jacq. fruits against multidrug-resistant strains: Inhibition of efflux pumps and β-lactamase. Plants 2023 ; 12(12) : 2377. [CrossRef]

- Prinderre P, Piccerelle P, Cauture E, Kalantzis G, Reynier J, Joachim J. Formulation and evaluation of o/w emulsions using experimental design. Int J Pharm 1998; 163, 73-9.

- Soussy CJ, Carret G, Cavallo JD, Chardon H, Chidiac C, Choutet P, Courvalin P, Dabernat H, Drugeon H, Dubreuil L, Goldstein F, Jarlier V, Leclercq R, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Philippon A, Quentin C, Rouveix B, Sirot J. « Comité de l'antibiogramme de la Société française de microbiologie. Communiqué 2000--2001 [Antibiogram Committee of the French Microbiology Society. Report 2000-2001] ». Pathologie Biologie (Paris) 2000 ; 48 (9) : 832-71.

- Lahlou, M. Methods to study the phytochemistry and bioactivity of essential oils. Phytother Res 2004 ; 18 (6) : 435-48.

| Plant species | Organs | Yield of extraction | Color | Density |

| Ocimum gratissimum | Leaves and twigs | 1.12±0.02 | Bright yellow | 0.89 |

| Ocimum basilicum | Leaves and twigs | 0.62±0.01 | Dark yellow | 0.88 |

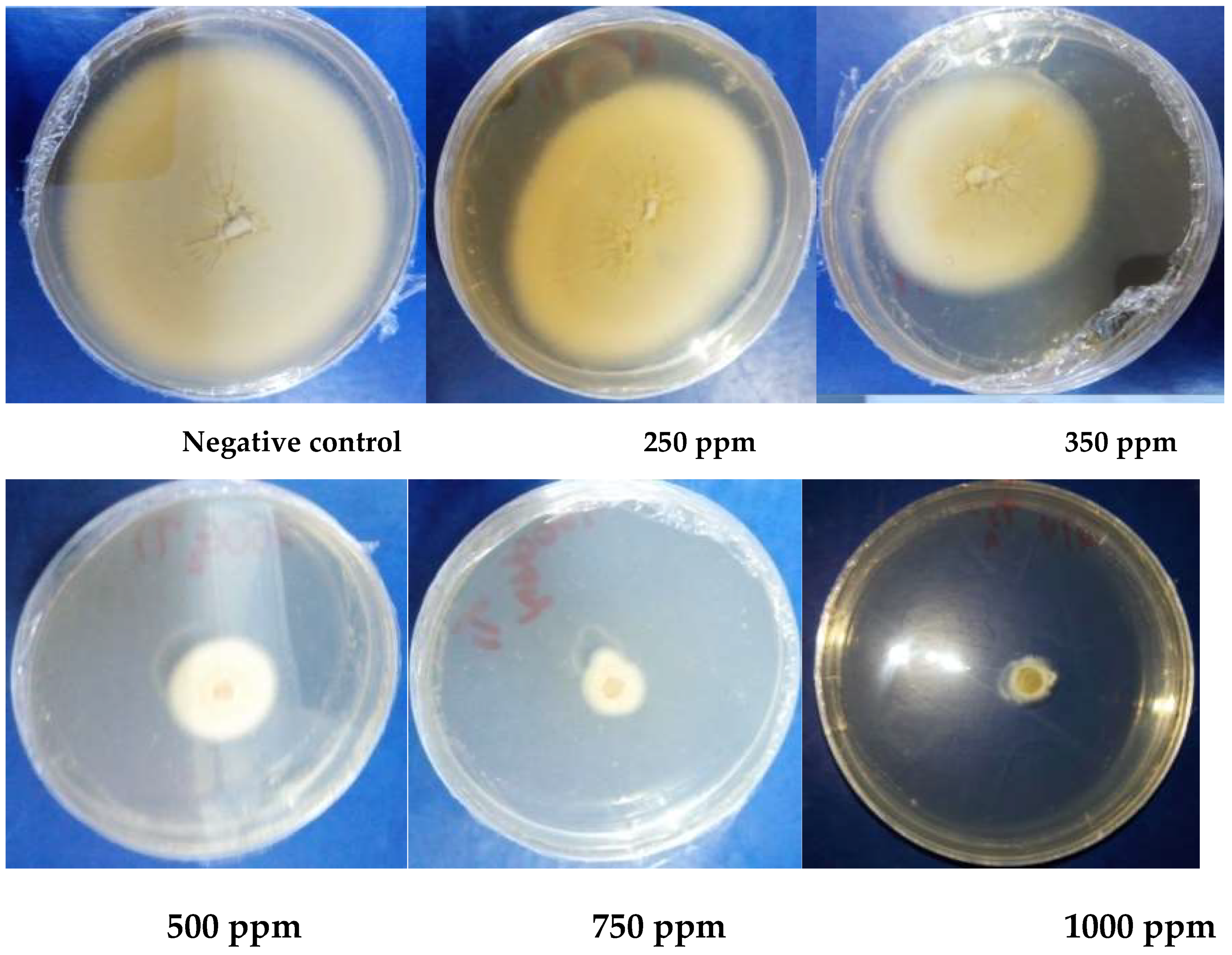

| Kovats’ indices | Name of the compound | Ocimum gratissimum | Ocimum basilicum | ||

| Monoterpenes | 93.87 | 92.51 | |||

| Hydrocarbonated monoterpenes | 48.22 | 7.93 | |||

| 1 | 812 | α-pinene | 1.55 | 1.20 | |

| 2 | 825 | β-pinene | - | 2.30 | |

| 3 | 828 | α-myrcene | 4.73 | 1.34 | |

| 4 | 848 | α-ocimene | - | 1.96 | |

| 5 | 926 | α-thujene | 6.05 | - | |

| 6 | 945 | Camphene | 0.18 | - | |

| 7 | 969 | Sabinene | 1.43 | - | |

| 8 | 1002 | α-terpinene | 0.42 | - | |

| 9 | 1076 | γ-terpinene | 33.73 | 1.13 | |

| 10 | 1097 | Terpinolene | 0.13 | - | |

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | 45.65 | 84.58 | |||

| 11 | 843 | Eucalyptol | - | 16.78 | |

| 12 | 865 | Fenchone | - | 1.09 | |

| 13 | 1032 | 1,8-cineole | 16.65 | - | |

| 14 | 1092 | Linalol | 0.97 | 55.32 | |

| 15 | 1110 | Trans-thujone | 0.11 | - | |

| 16 | 1135 | Isocitral exo | 0.09 | - | |

| 17 | 1164 | Borneol | 0.08 | - | |

| 18 | 1176 | Terpinen-4-ol | 1.08 | 3.94 | |

| 19 | 1226 | Thymol methyléther | 0.14 | - | |

| 20 | 1314 | Thymol | 26.44 | - | |

| 21 | 1360 | Eugenol | 0.09 | 7.45 | |

| Sesquiterpenes | 5.8 | 7.46 | |||

| Hydrocarbonated sesquiterpenes | 5.37 | 5.26 | |||

| 20 | 1015 | (-)-endo-α- bergamotene | - | 2.75 | |

| 21 | 1036 | Bicyclogermacrene | - | 0.67 | |

| 22 | 1042 | ϒ muurolene | - | 0.97 | |

| 23 | 1380 | β-cubebene | 0.47 | - | |

| 24 | 1393 | β-elemene | 0.27 | - | |

| 25 | 1432 | β-caryophyllene | 2.64 | - | |

| 26 | 1460 | α-humulene | 0.26 | - | |

| 27 | 1487 | Germacreme D | 0.13 | 0.87 | |

| 28 | 1496 | α-curcumene | 0.88 | - | |

| 29 | 1502 | α-selimene | 0.36 | - | |

| 30 | 1524 | d-cadinene | 0.36 | - | |

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 0.43 | 2.20 | |||

| 31 | 1080 | Tau-cardinol | - | 2.20 | |

| 32 | 1591 | β-6-elemene | 0.25 | - | |

| 33 | 1665 | Hydroxycaryophyllene | 0.18 | - | |

| TOTAL | 99.67 | 99.97 | |||

| Sample (OG) | Essential oil | Nanoemulsion | Griseofulvin | |||

| TR | TI | TR | TI | TR | TI | |

| MIC (ppm) | 1000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | ˃5000 | |

| MFC (ppm) | 1000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | ||

| Sample (OB) | Essential oil | Nanoemulsion | Griseofulvin | |||

| TR | TI | TR | TI | TR | TI | |

| MIC (ppm) | 5750 | / | 6750 | / | ˃5000 | |

| MFC (ppm) | 5750 | / | 6750 | / | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).