Submitted:

17 May 2025

Posted:

19 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

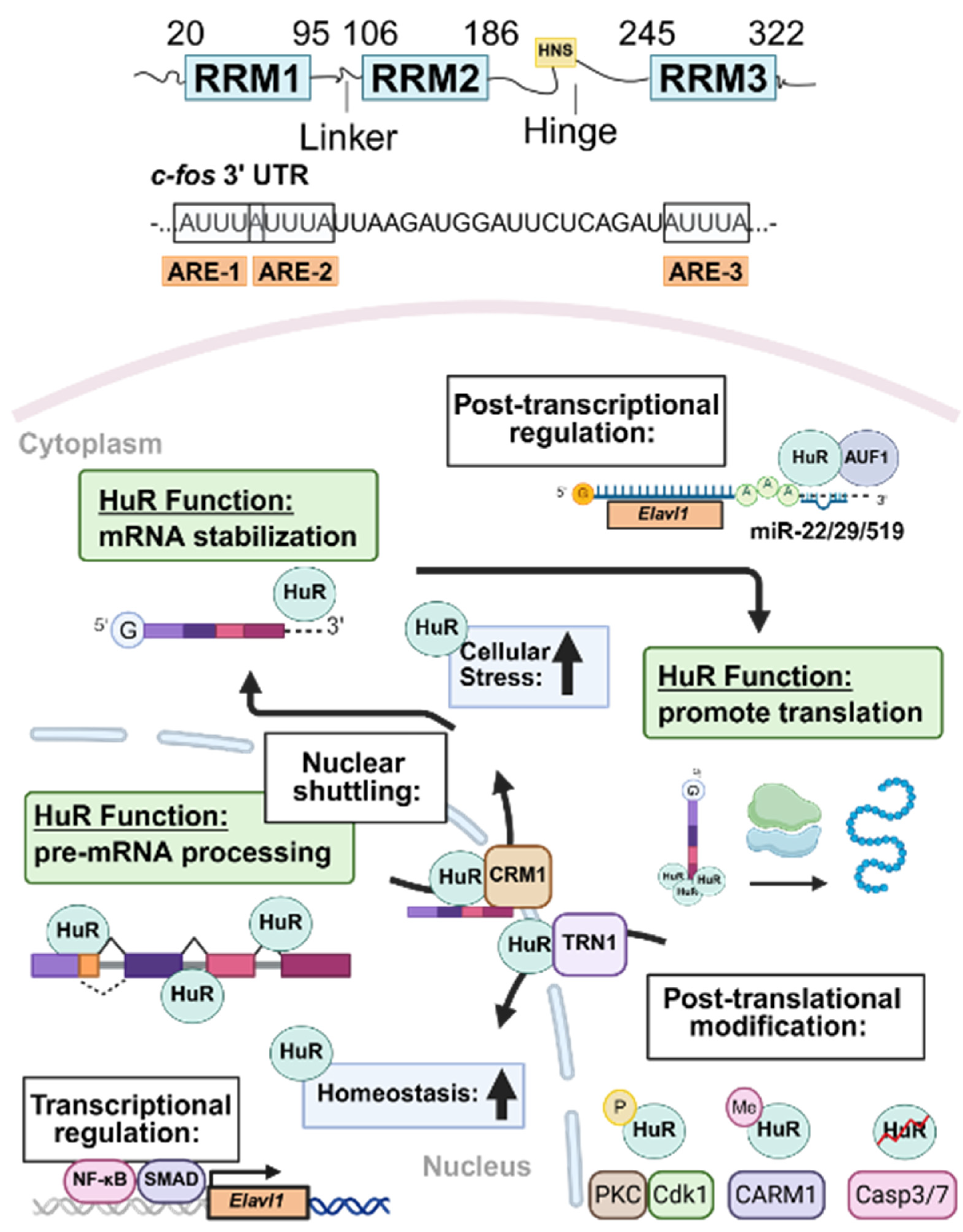

2. HuR Structure and Subcellular Localization

3. Regulation of HuR Expression

4. Overview of HuR Function During Physiological and Pathological Conditions

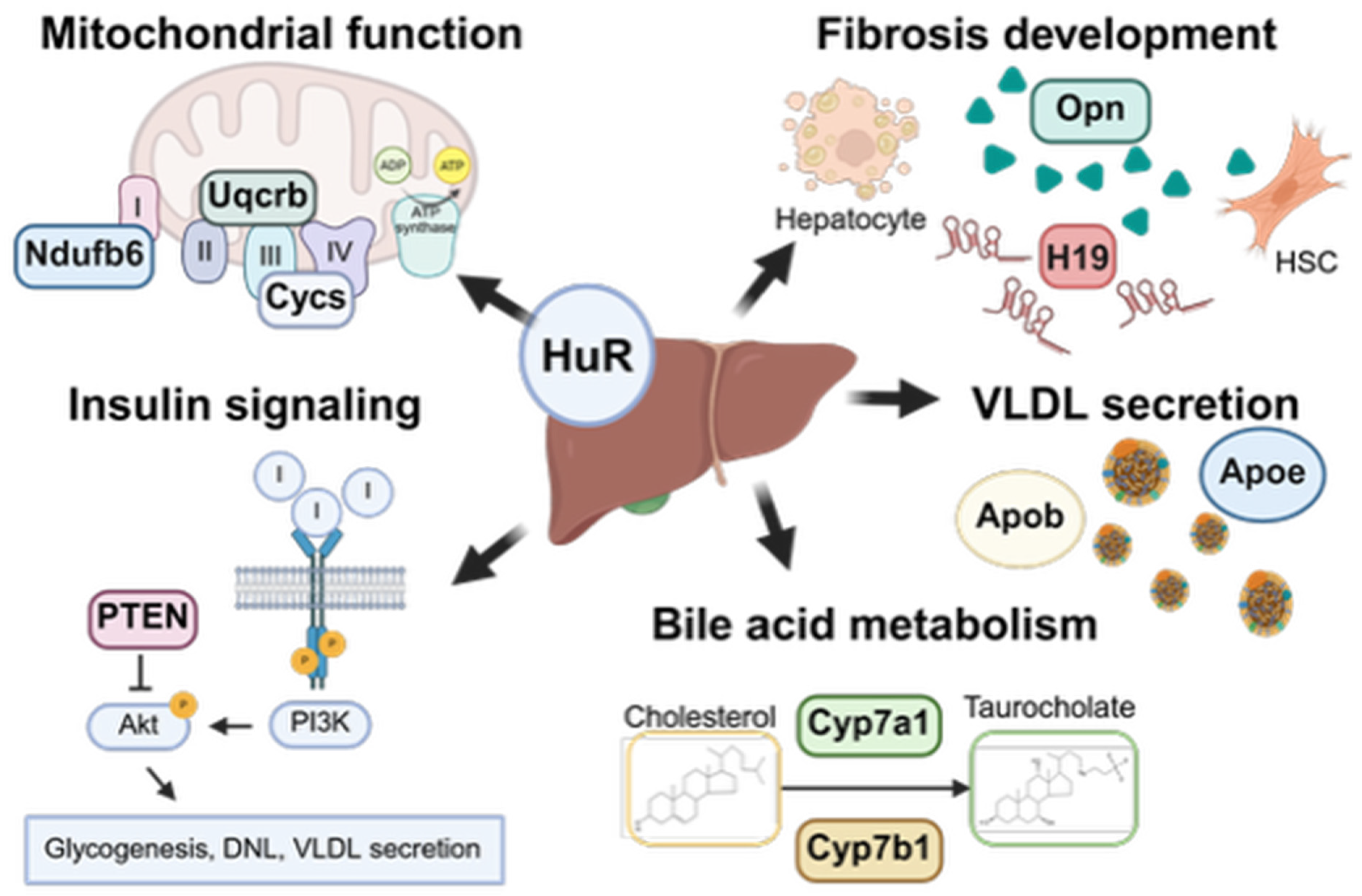

5. Role of HuR in Liver Homeostasis and MASLD

5.1. MASLD Epidemiology and Prevalence

5.2. Role of HuR in Hepatic Steatosis

5.2.1. HuR Regulates Insulin Signaling and Hepatic Steatosis

5.2.2. HuR Regulation of Very Low-Density Lipoprotein Secretion

5.3. Role of HuR in Cholesterol Metabolism

5.4. Role of HuR in Bile Acid Metabolism

5.5. HuR Regulates Mitochondrial Function and Oxidative Stress

5.6. Role of HuR in Autophagy

5.7. HuR Regulates Apoptosis and Cell Survival

5.8. HuR in Hepatic Inflammation

5.9. HuR in Liver Fibrosis

6. Role of HuR in Extrahepatic Metabolic Comorbidities

6.1. Obesity

6.1.1. Overview of Obesity and Its Association with MASLD

6.1.2. Role of HuR in Adipocyte Differentiation and Obesity

6.2. Cardiovascular Disease and Type II Diabetes Mellitus

6.2.1. Overview of Cardiovascular Disease, Diabetic Cardiomyopathy and Their Link to MASLD

6.2.2. Role of HuR in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Cardiovascular Disease

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Wong, V.W.S.; Ratziu, V.; Bugianesi, E.; Francque, S.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Valenti, L.; Roden, M.; Schick, F.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Gastaldelli, A.; et al. EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Journal of Hepatology 2024, 81, 492–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Golabi, P.; Paik, J.M.; Henry, A.; Van Dongen, C.; Henry, L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology 2023, 77, 1335–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Blissett, D.; Blissett, R.; Henry, L.; Stepanova, M.; Younossi, Y.; Racila, A.; Hunt, S.; Beckerman, R. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology 2016, 64, 1577–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, J.P.; Arrese, M.; Trauner, M. Recent Insights into the Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. In Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease, Vol 13, Abbas, A.K., Aster, J.C., Eds.; Annual Review of Pathology-Mechanisms of Disease; 2018; Volume 13, pp. 321-350.

- Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tilg, H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut 2024, 73, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Csermely, A.; Petracca, G.; Beatrice, G.; Corey, K.E.; Simon, T.G.; Byrne, C.D.; Targher, G. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2021, 6, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promrat, K.; Kleiner, D.E.; Niemeier, H.M.; Jackvony, E.; Kearns, M.; Wands, J.R.; Fava, J.L.; Wing, R.R. Randomized Controlled Trial Testing the Effects of Weight Loss on Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010, 51, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golabi, P.; Paik, J.M.; Kumar, A.; Al Shabeeb, R.; Eberly, K.E.; Cusi, K.; Gundurao, N.; Younossi, Z.M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and associated mortality in individuals with type 2 diabetes, pre-diabetes, metabolically unhealthy, and metabolically healthy individuals in the United States. Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental 2023, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyzos, S.A.; Kountouras, J.; Mantzoros, C.S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: From pathophysiology to therapeutics. Metabolism-Clinical and Experimental 2019, 92, 82–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.J.; Cheng, S.; Campbell, C.; Wright, A.; Furneaux, H. Cloning and characterization of HuR, a ubiquitously expressed Elav-like protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1996, 271, 8144–8151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, A.R.; Grossman, D.; White, K. Mutant alleles at the locus elav in Drosophila melanogaster lead to nervous system defects. A developmental-genetic analysis. J Neurogenet 1985, 2, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hasman, R.A.; Barron, V.A.; Luo, G.B.; Lou, H. A nuclear function of Hu proteins as neuron-specific alternative RNA processing regulators. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2006, 17, 5105–5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebedeva, S.; Jens, M.; Theil, K.; Schwanhäusser, B.; Selbach, M.; Landthaler, M.; Rajewsky, N. Transcriptome-wide Analysis of Regulatory Interactions of the RNA-Binding Protein HuR. Molecular Cell 2011, 43, 340–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakheet, T.; Hitti, E.; Khabar, K.S.A. ARED-Plus: an updated and expanded database of AU-rich element-containing mRNAs and pre-mRNAs. Nucleic Acids Research 2018, 46, D218–D220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabar, K.S.A. The AU-rich transcriptome: More than interferons and cytokines, and its role in disease. Journal of Interferon and Cytokine Research 2005, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinman, M.N.; Lou, H. Diverse molecular functions of Hu proteins. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2008, 65, 3168–3181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikantan, S.; Gorospe, M. HuR function in disease. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2012, 17, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myer, V.E.; Fan, X.H.C.; Steitz, J.A. Identification of HuR as a protein implicated in AUUUA-mediated mRNA decay. Embo Journal 1997, 16, 2130–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Connick, M.C.; Vanderhoof, J.; Ishak, M.A.; Hartley, R.S. MicroRNA-16 Modulates HuR Regulation of Cyclin E1 in Breast Cancer Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2015, 16, 7112–7132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haga, Y., et al. Increased expression of long non-coding RNA FIRRE promotes hepatocellular carcinoma by HuR-CyclinD1 axis signaling. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2024, 300. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.G.; Caldwell, M.C.; Lin, S.K.; Furneaux, H.; Gorospe, M. HuR regulates cyclin A and cyclin B1 mRNA stability during cell proliferation. Embo Journal 2000, 19, 2340–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gantt, K.; Cherry, J.; Tenney, R.; Karschner, V.; Pekala, P.H. An early event in adipogenesis, the nuclear selection of the CCAAT enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ) mRNA by HuR and its translocation to the cytosol. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 24768–24774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, M.; Aguila, H.L.; Michaud, J.; Ai, Y.X.; Wu, M.T.; Hemmes, A.; Ristimaki, A.; Guo, C.Y.; Furneaux, H.; Hla, T. Essential role of the RNA-binding protein HuR in progenitor cell survival in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2009, 119, 3530–3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazroui, R.; Di Marco, S.; Clair, E.; von Roretz, C.; Tenenbaum, S.A.; Keene, J.D.; Saleh, M.; Gallouzi, I.E. Caspase-mediated cleavage of HuR in the cytoplasm contributes to pp32/PHAP-I regulation of apoptosis. Journal of Cell Biology 2008, 180, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Roretz, C.; Lian, X.J.; Macri, A.M.; Punjani, N.; Clair, E.; Drouin, O.; Dormoy-Raclet, V.; Ma, J.F.; Gallouzi, I.E. Apoptotic-induced cleavage shifts HuR from being a promoter of survival to an activator of caspase-mediated apoptosis. Cell Death and Differentiation 2013, 20, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, L.J.; Tian, H.Y.; Chang, N.; Yi, J.; Xue, L.X.; Jiang, B.; Gorospe, M.; Zhang, X.W.; Wang, W.G. Loss of CARM1 is linked to reduced HuR function in replicative senescence. Bmc Molecular Biology 2013, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Chang, N.; Liu, X.W.; Guo, G.; Xue, L.X.; Tong, T.J.; Gorospe, M.; Wang, W.G. Reduced nuclear export of HuR mRNA by HuR is linked to the loss of HuR in replicative senescence. Nucleic Acids Research 2010, 38, 1547–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsanou, V.; Milatos, S.; Yiakouvaki, A.; Sgantzis, N.; Kotsoni, A.; Alexiou, M.; Harokopos, V.; Aidinis, V.; Hemberger, M.; Kontoyiannis, D.L. The RNA-Binding Protein Elavl1/HuR Is Essential for Placental Branching Morphogenesis and Embryonic Development. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2009, 29, 2762–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhoo, A.; Iruarrizaga-Lejarreta, M.; Beraza, N.; García-Rodríguez, J.L.; Embade, N.; Fernández-Ramos, D.; Martínez-López, N.; Gutiérrez-De Juan, V.; Arteta, B.; Caballeria, J.; et al. Human antigen R contributes to hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. Hepatology 2012, 56, 1870–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.J.; Chang, N.; Zhao, Z.X.; Tian, L.; Duan, X.H.; Yang, L.; Li, L.Y. Essential Roles of RNA-binding Protein HuR in Activation of Hepatic Stellate Cells Induced by Transforming Growth Factor-β1. Scientific Reports 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Y.; Gong, L.; Liu, S.Z.; Zhang, Y.J.; Zhang, C.M.; Tian, M.; Lu, H.X.; Bu, P.L.; Yang, J.M.; Ouyang, C.H.; et al. Adipose HuR protects against diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Nature Communications 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siang, D.T.C.; Lim, Y.C.; Kyaw, A.M.M.; Win, K.N.; Chia, S.Y.; Degirmenci, U.; Hu, X.; Tan, B.C.; Walet, A.C.E.; Sun, L.; et al. The RNA-binding protein HuR is a negative regulator in adipogenesis. Nature Communications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, N.; Corcoran, D.L.; Nusbaum, J.D.; Reid, D.W.; Georgiev, S.; Hafner, M.; Ascano, M.; Tuschl, T.; Ohler, U.; Keene, J.D. Integrative Regulatory Mapping Indicates that the RNA-Binding Protein HuR Couples Pre-mRNA Processing and mRNA Stability. Molecular Cell 2011, 43, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pabis, M.; Popowicz, G.M.; Stehle, R.; Fernández-Ramos, D.; Asami, S.; Warner, L.; García-Mauriño, S.M.; Schlundt, A.; Martínez-Chantar, M.L.; Díaz-Moreno, I.; et al. HuR biological function involves RRM3-mediated dimerization and RNA binding by all three RRMs. Nucleic Acids Research 2019, 47, 1011–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zeng, F.X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, H.H.; Liu, Z.X.; Niu, L.W.; Teng, M.K.; Li, X. The structure of the ARE-binding domains of Hu antigen R (HuR) undergoes conformational changes during RNA binding. Acta Crystallographica Section D-Structural Biology 2013, 69, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreau, C.; Paillard, L.; Osborne, H.B. AU-rich elements and associated factors: are there unifying principles? Nucleic Acids Research 2005, 33, 7138–7150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenan, D.J.; Query, C.C.; Keene, J.D. RNA recognition: towards identifying determinants of specificity. Trends Biochem Sci 1991, 16, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.J.; Chung, S.; Furneaux, H. The Elav-like proteins bind to AU-rich elements and to the poly(A) tail of mRNA. Nucleic Acids Research 1997, 25, 3564–3569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, C.M.; Gallouzi, I.E.; Steitz, J.A. Protein ligands to HuR modulate its interaction with target mRNAs in vivo. Journal of Cell Biology 2000, 151, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.C.; Steitz, J.A. Overexpression of HuR, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein, increases the in vivo stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. EMBO J 1998, 17, 3448–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallouzi, I.E.; Brennan, C.M.; Stenberg, M.G.; Swanson, M.S.; Eversole, A.; Maizels, N.; Steitz, J.A. HuR binding to cytoplasmic mRNA is perturbed by heat shock. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2000, 97, 3073–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.H.C.; Steitz, J.A. HNS, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling sequence in HuR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1998, 95, 15293–15298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.H.; Hoelz, A. The Structure of the Nuclear Pore Complex (An Update). In Annual Review of Biochemistry, Vol 88, Kornberg, R.D., Ed.; Annual Review of Biochemistry; 2019; Volume 88, pp. 725-783.

- Wing, C.E.; Fung, H.Y.J.; Chook, Y.M. Karyopherin-mediated nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2022, 23, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallouzi, I.E.; Brennan, C.M.; Steitz, J.A. Protein ligands mediate the CRM1-dependent export of HuR in response to heat shock. Rna 2001, 7, 1348–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güttinger, S.; Mühlhäusser, P.; Koller-Eichhorn, R.; Brennecke, J.; Kutay, U. Transportin2 functions as importin and mediates nuclear import of HuR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 2918–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.G.; Yang, X.L.; Kawai, T.; de Silanes, I.L.; Mazan-Mamczarz, K.; Chen, P.L.; Chook, Y.M.; Quensel, C.; Köhler, M.; Gorospe, M. AMP-activated protein kinase-regulated phosphorylation and acetylation of importin α1 -: Involvement in the nuclear import of RNA-binding protein HuR. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 48376–48388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmadi, W.; Al-Ghamdi, M.; Al-Haj, L.; Al-Saif, M.; Khabar, K.S.A. Alternative polyadenylation variants of the RNA binding protein, HuR: abundance, role of AU-rich elements and auto-Regulation. Nucleic Acids Research 2009, 37, 3612–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraju, S.; Lee, B.S. Kruppel -Like Factor 8 is a Stress-Responsive Transcription Factor that Regulates Expression of HuR. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2014, 34, 519–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyaraj, S.C.; Dakhlallah, D.; Hill, S.R.; Lee, B.S. Expression and distribution of HuR during ATP depletion and recovery in proximal tubule cells. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2006, 291, F1255–F1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, P.H.; Fuller, J.J.; Nabors, L.B.; Detloff, P.J. Analysis of the 5’ end of the mouse Elavl1 (mHuA) gene reveals a transcriptional regulatory element and evidence for conserved genomic organization. Gene 2000, 242, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.J.; Ryu, B.K.; Lee, M.G.; Han, J.; Lee, J.H.; Ha, T.K.; Byun, D.S.; Chae, K.S.; Lee, B.H.; Chun, H.S.; et al. NF-κB Activates Transcription of the RNA-Binding Factor HuR, via PI3K-AKT Signaling, to Promote Gastric Tumorigenesis. Gastroenterology 2008, 135, 2030–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayupova, D.A.; Singh, M.; Leonard, E.C.; Basile, D.P.; Lee, B.S. Expression of the RNA-stabilizing protein HuR in ischemia-reperfusion injury of rat kidney. American Journal of Physiology-Renal Physiology 2009, 297, F95–F105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pullmann, R.; Kim, H.H.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Lal, A.; Martindale, J.L.; Yang, X.L.; Gorospe, M. Analysis of turnover and translation regulatory RNA-Binding protein expression through binding to cognate mRNAs. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2007, 27, 6265–6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Xiao, L.; Wang, J.Y. HuR and Its Interactions with Noncoding RNAs in Gut Epithelium Homeostasis and Diseases. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, A.; Mazan-Mamczarz, K.; Kawai, T.; Yang, X.L.; Martindale, J.L.; Gorospe, M. Concurrent versus individual binding of HuR and AUF1 to common labile target mRNAs. Embo Journal 2004, 23, 3092–3102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Q.; Chen, X.R.; Cheng, R.J.; Yang, F.; Yu, M.C.; Wang, C.; Cui, S.F.; Hong, Y.T.; Liang, H.W.; Liu, M.H.; et al. The Jun/miR-22/HuR regulatory axis contributes to tumourigenesis in colorectal cancer. Molecular Cancer 2018, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.J.; Wu, W.; Chen, Q.Q.; Liu, S.H.; Zheng, Z.Y.; Cui, Z.L.; Xu, J.P.; Xue, Y.; Lin, D.H. miR-29b-3p suppresses the malignant biological behaviors of AML cells via inhibiting NF-κB and JAK/STAT signaling pathways by targeting HuR. Bmc Cancer 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Srikantan, S.; Kuwano, Y.; Gorospe, M. miR-519 reduces cell proliferation by lowering RNA-binding protein HuR levels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2008, 105, 20297–20302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grammatikakis, I.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Gorospe, M. Posttranslational control of HuR function. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Rna 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Rao, J.N.; Zou, T.T.; Xiao, L.; Wang, P.Y.; Turner, D.J.; Gorospe, M.; Wang, J.Y. Polyamines Regulate c-Myc Translation through Chk2-dependent HuR Phosphorylation. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2009, 20, 4885–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Pullmann, R.; Lai, A.; Kim, H.H.; Galban, S.; Yang, X.L.; Blethrow, J.D.; Walker, M.; Shubert, J.; Gillespie, D.A.; et al. Phosphorylation of HuR by Chk2 regulates SIRT1 expression. Molecular Cell 2007, 25, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doller, A.; Huwiler, A.; Müller, R.; Radeke, H.H.; Pfeilschifter, J.; Eberhardt, W. Protein kinase Cα-dependent phosphorylation of the mRNA-stabilizing factor HuR:: Implications for posttranscriptional regulation of cyclooxygenase-2. Molecular Biology of the Cell 2007, 18, 2137–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernau, N.S.; Fugmann, D.; Leyendecker, M.; Reimann, K.; Grether-Beck, S.; Galban, S.; Ale-Agha, N.; Krutmann, J.; Klotz, L.O. Role of HuR and p38MAPK in ultraviolet B-induced post-transcriptional regulation of COX-2 expression in the human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT. J Biol Chem 2010, 285, 3896–3904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafarga, V.; Cuadrado, A.; Lopez de Silanes, I.; Bengoechea, R.; Fernandez-Capetillo, O.; Nebreda, A.R. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase- and HuR-dependent stabilization of p21(Cip1) mRNA mediates the G(1)/S checkpoint. Mol Cell Biol 2009, 29, 4341–4351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Khalaf, H.H.; Aboussekhra, A. ATR controls the UV-related upregulation of the CDKN1A mRNA in a Cdk1/HuR-dependent manner. Mol Carcinog 2014, 53, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyabal, P.; Thandavarayan, R.A.; Joladarashi, D.; Babu, S.S.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Bhimaraj, A.; Youker, K.A.; Kishore, R.; Krishnamurthy, P. MicroRNA-9 inhibits hyperglycemia-induced pyroptosis in human ventricular cardiomyocytes by targeting ELAVL1. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2016, 471, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, P.S.; Tanveer, R.; Port, J.D. FRET-detectable interactions between the ARE binding proteins, HuR and p37AUF1. Rna 2007, 13, 1453–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fialcowitz-White, E.J.; Brewer, B.Y.; Ballin, J.D.; Willis, C.D.; Toth, E.A.; Wilson, G.M. Specific protein domains mediate cooperative assembly of HuR oligomers on AU-rich mRNA-destabilizing sequences. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, 282, 20948–20959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.B. RNPC1 modulates the RNA-binding activity of, and cooperates with, HuR to regulate p21 mRNA stability. Nucleic Acids Research 2010, 38, 2256–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silanes, I.L.; Zhan, M.; Lal, A.; Yang, X.L.; Gorospe, M. Identification of a target RNA motif for RNA-binding protein HuR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 2987–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.H.; Kim, K.M.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Yoon, J.H.; Panda, A.C.; Munk, R.; Kim, J.; Curtis, J.; Moad, C.A.; Wohler, C.M.; et al. HuR and GRSF1 modulate the nuclear export and mitochondrial localization of the lncRNA RMRP. Genes Dev 2016, 30, 1224–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Munoz, M.D.; Bell, S.E.; Fairfax, K.; Monzon-Casanova, E.; Cunningham, A.F.; Gonzalez-Porta, M.; Andrews, S.R.; Bunik, V.I.; Zarnack, K.; Curk, T.; et al. The RNA-binding protein HuR is essential for the B cell antibody response. Nature Immunology 2015, 16, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.Q.; Xu, L. The RNA-binding protein HuR in human cancer: A friend or foe. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2022, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dery, K.J.; Nakamura, K.; Kadono, K.; Hirao, H.; Kageyama, S.; Ito, T.; Kojima, H.; Kaldas, F.; Busuttil, R.W.; Kupiec-Weglinski, J.W. Human Antigen R (HuR): A New Regulator of Heme Oxygenase-1 Cytoprotection in Mouse and Human Liver Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation 2020, 20, 721–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsye, P.; Zheng, L.; Si, Y.; Kim, S.; Luo, W.Y.; Crossman, D.K.; Bratcher, P.E.; King, P.H. HuR promotes the molecular signature and phenotype of activated microglia: Implications for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other neurodegenerative diseases. Glia 2017, 65, 945–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.D.; Furuuchi, N.; Aslanukova, L.; Huang, Y.H.; Brown, S.Z.; Jiang, W.; Addya, S.; Vishwakarma, V.; Peters, E.; Brody, J.R.; et al. Elevated HuR in Pancreas Promotes a Pancreatitis-Like Inflammatory Microenvironment That Facilitates Tumor Development. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2018, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Chen, Y.; Hu, W.R.; Liu, X.Y.; Hao, W.J.; Xing, J.; Ding, J.; Xu, Y.C.; Yao, F.; Zhao, Y.J.; et al. TRPM7 facilitates fibroblast-like synoviocyte proliferation, metastasis and inflammation through increasing IL-6 stability via the PKCα-HuR axis in rheumatoid arthritis. International Immunopharmacology 2024, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.X.; Zheng, H.Y.; Zhou, K.; Xie, H.L.; Ren, Z.; Liu, H.T.; Liu, H.; Zhou, Z.X.; Jiang, Z.S. Multifaceted Nature of HuR in Atherosclerosis Development. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou-Vafeiadou, E.; Ioakeimidis, F.; Andreadou, M.; Giagkas, G.; Stamatakis, G.; Reczko, M.; Samiotaki, M.; Papanastasiou, A.D.; Karakasiliotis, I.; Kontoyiannis, D.L. Divergent Innate and Epithelial Functions of the RNA-Binding Protein HuR in Intestinal Inflammation. Frontiers in Immunology 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durie, D.; Lewis, S.M.; Liwak, U.; Kisilewicz, M.; Gorospe, M.; Holcik, M. RNA-binding protein HuR mediates cytoprotection through stimulation of XIAP translation. Oncogene 2011, 30, 1460–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullmann, M.; Göpfert, U.; Siewe, B.; Hengst, L. ELAV/Hu proteins inhibit p27 translation via an IRES element in the p27 5′UTR. Genes & Development 2002, 16, 3087–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.Q.; Gardashova, G.; Lan, L.; Han, S.; Zhong, C.C.; Marquez, R.T.; Wei, L.J.; Wood, S.; Roy, S.; Gowthaman, R.; et al. Targeting the interaction between RNA-binding protein HuR and FOXQ1 suppresses breast cancer invasion and metastasis. Communications Biology 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, R.; Srivastava, O.P.; Pfister, R.R. Downregulation of β-actin and its regulatory gene HuR affect cell migration of human corneal fibroblasts. Molecular Vision 2014, 20, 593–605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tian, M.; Wang, J.J.; Liu, S.M.; Li, X.Y.; Li, J.Y.; Yang, J.M.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.C. Hepatic HuR protects against the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by targeting PTEN. Cell Death & Disease 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, P.; Gargani, S.; Palladini, A.; Chatzimike, M.; Grzybek, M.; Peitzsch, M.; Papanastasiou, A.D.; Pyrina, I.; Ntafis, V.; Gercken, B.; et al. The RNA binding protein human antigen R is a gatekeeper of liver homeostasis. Hepatology 2022, 75, 881–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Y.; Tai, Y.L.; Way, G.; Zeng, J.; Zhao, D.; Su, L.Y.; Jiang, X.X.; Jackson, K.G.; Wang, X.; Gurley, E.C.; et al. RNA binding protein HuR protects against NAFLD by suppressing long noncoding RNA H19 expression. Cell and Bioscience 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, J.M.; Henry, L.; Younossi, Y.; Ong, J.; Alqahtani, S.; Younossi, Z.M. The burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is rapidly growing in every region of the world from 1990 to 2019. Hepatology Communications 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, M.S.; Liu, Z.Q.; Yuan, H.B.; Wu, X.F.; Shi, T.T.; Chen, X.D.; Zhang, T.J. Increasing prevalence of NAFLD/NASH among children, adolescents and young adults from 1990 to 2017: a population-based observational study. Bmj Open 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, K.; Hind, J.; Hegarty, R. Updates in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease (MAFLD) in Children. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2023, 77, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Lazarus, J.V.; Ratziu, V.; Francque, S.M.; Sanyal, A.J.; Kanwal, F.; Romero, D.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arab, J.P.; et al. A multisociety Delphi consensus statement on new fatty liver disease nomenclature. Journal of Hepatology 2023, 79, 1542–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagstroem, H.; Vessby, J.; Ekstedt, M.; Shang, Y. 99% of patients with NAFLD meet MASLD criteria and natural history is therefore identical. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2024, 56, E76–E77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Stepanova, M.; Ong, J.; Trimble, G.; AlQahtani, S.; Younossi, I.; Ahmed, A.; Racila, A.; Henrys, L. Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Is the Most Rapidly Increasing Indication for Liver Transplantation in the United States. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2021, 19, 580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keam, S.J. Resmetirom: First Approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 729–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Zong, C.; Jiang, M.Y.; Hu, H.; Cheng, X.L.; Ni, J.H.; Yi, X.; Jiang, B.; Tian, F.; Chang, M.W.; et al. Hepatic HuR modulates lipid homeostasis in response to high-fat diet. Nature Communications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, J.; Scheja, L. Metabolic-associated fatty liver disease and lipoprotein metabolism. Molecular Metabolism 2021, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donnelly, K.L.; Smith, C.I.; Schwarzenberg, S.J.; Jessurun, J.; Boldt, M.D.; Parks, E.J. Sources of fatty acids stored in liver and secreted via lipoproteins in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2005, 115, 1343–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchesini, G.; Brizi, M.; Morselli-Labate, A.M.; Bianchi, G.; Bugianesi, E.; McCullough, A.J.; Forlani, G.; Melchionda, N. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with insulin resistance. American Journal of Medicine 1999, 107, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.E.L.; Ang, C.Z.; Quek, J.; Fu, C.E.; Lim, L.K.E.; Heng, Z.E.Q.; Tan, D.J.H.; Lim, W.H.; Yong, J.N.; Zeng, R.B.C.; et al. Global prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in type 2 diabetes mellitus: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2023, 72, 2138–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titchenell, P.M.; Lazar, M.A.; Birnbaum, M.J. Unraveling the Regulation of Hepatic Metabolism by Insulin. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 2017, 28, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomonaco, R.; Ortiz-Lopez, C.; Orsak, B.; Webb, A.; Hardies, J.; Darland, C.; Finch, J.; Gastaldelli, A.; Harrison, S.; Tio, F.; et al. Effect of adipose tissue insulin resistance on metabolic parameters and liver histology in obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2012, 55, 1389–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, K.F.; Dufour, S.; Savage, D.B.; Bilz, S.; Solomon, G.; Yonemitsu, S.; Cline, G.W.; Befroy, D.; Zemany, L.; Kahn, B.B.; et al. The role of skeletal muscle insulin resistance in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2007, 104, 12587–12594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, J.T.; Kim, P.T.W.; Peacock, J.W.; Yau, T.Y.; Mui, A.L.F.; Chung, S.W.; Sossi, V.; Doudet, D.; Green, D.; Ruth, T.J.; et al. Pten (phosphatase and tensin homologue gene) haploinsufficiency promotes insulin hypersensitivity. Diabetologia 2007, 50, 395–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiles, B.; Wang, Y.; Stahl, A.; Bassilian, S.; Lee, W.P.; Kim, Y.J.; Sherwin, R.; Devaskar, S.; Lesche, R.; Magnuson, M.A.; et al. Live-specific deletion of negative regulator Pten results in fatty liver and insulin hypersensitivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2004, 101, 2082–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.H.; Ginsberg, H.N. Increased very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 2011, 22, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adiels, M.; Taskinen, M.R.; Packard, C.; Caslake, M.J.; Soro-Paavonen, A.; Westerbacka, J.; Vehkavaara, S.; Hakkinen, A.; Olofsson, S.O.; Yki-Jarvinen, H.; et al. Overproduction of large VLDL particles is driven by increased liver fat content in man. Diabetologia 2006, 49, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, S.; Bartlett, K.; Pourfarzam, M. Mammalian mitochondrial beta-oxidation. Biochemical Journal 1996, 320, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Y.; Cohen, D.E. Mechanisms of hepatic triglyceride accumulation in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Gastroenterology 2013, 48, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, A.D. Apolipoprotein E in lipoprotein metabolism, health and cardiovascular disease. Pathology 2019, 51, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welty, F.K. Hypobetalipoproteinemia and abetalipoproteinemia: liver disease and cardiovascular disease. Current Opinion in Lipidology 2020, 31, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, M.; Kamzolas, I.; Harder, L.M.; Oakley, F.; Trautwein, C.; Hatting, M.; Ross, T.; Bernardo, B.; Oldenburger, A.; Hjuler, S.T.; et al. An unbiased ranking of murine dietary models based on their proximity to human metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Nature Metabolism 2024, 6, 1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C.P.; James, O.F.W. Steatohepatitis: A tale of two “hits”? Gastroenterology 1998, 114, 842–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilg, H.; Moschen, A.R. Evolution of Inflammation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: The Multiple Parallel Hits Hypothesis. Hepatology 2010, 52, 1836–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, C.L.; Morales, A.L.; Savard, C.; Farrell, G.C.; Ioannou, G.N. Role of Cholesterol-Associated Steatohepatitis in the Development of NASH. Hepatology Communications 2022, 6, 12–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, G.N. The Role of Cholesterol in the Pathogenesis of NASH. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 2016, 27, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonen, P.; Kotronen, A.; Hallikainen, M.; Sevastianova, K.; Makkonen, J.; Hakkarainen, A.; Lundbom, N.; Miettinen, T.A.; Gylling, H.; Yki-Järvinen, H. Cholesterol synthesis is increased and absorption decreased in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease independent of obesity. Journal of Hepatology 2011, 54, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, R. Sterol metabolism and SREBP activation. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2010, 501, 177–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botham KM, M.P. Harper’s Illustrated Biochemistry, 31 ed.; Rodwell, V., Bender, DA, Botham, KM, Kennelly PJ, Weil P., Ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: 2018.

- Musso, G.; Gambino, R.; Cassader, M. Cholesterol metabolism and the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Progress in Lipid Research 2013, 52, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Chen, Y.X.; Tang, R.K.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Gong, J.P.; Huang, A.L.; Varghese, Z.; Moorhead, J.F.; Ruan, X.Z. Inflammatory stress exacerbates hepatic cholesterol accumulation via increasing cholesterol uptake and de novo synthesis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2011, 26, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Rooyen, D.M.; Larter, C.Z.; Haigh, W.G.; Yeh, M.M.; Ioannou, G.; Kuver, R.; Lee, S.P.; Teoh, N.C.; Farrell, G.C. Hepatic Free Cholesterol Accumulates in Obese, Diabetic Mice and Causes Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1393–U1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, E. Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2008, 9, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marí, M.; Caballero, F.; Colell, A.; Morales, A.; Caballeria, J.; Fernandez, A.; Enrich, C.; Fernandez-Checa, J.C.; García-Ruiz, C. Mitochondrial free cholesterol loading sensitizes to TNF- and Fas-mediated steatohepatitis. Cell Metabolism 2006, 4, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhuri, S.; Klaassen, C.D. Molecular Regulation of Bile Acid Homeostasis. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2022, 50, 425–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.G.; Chiang, J.Y.L. Bile Acid Signaling in Metabolic Disease and Drug Therapy. Pharmacological Reviews 2014, 66, 948–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandak, W.M., Kakiyama, G. The acidic pathway of bile acid synthesis: Not just an alternative pathway. Liver Research 2019, 3, 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Linnet, K. Postprandial plasma concentrations of glycine and taurine conjugated bile acids in healthy subjects. Gut 1983, 24, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Fukami, T.; Masuo, Y.; Brocker, C.N.; Xie, C.; Krausz, K.W.; Wolf, C.R.; Henderson, C.J.; Gonzalez, F.J. Cyp2c70 is responsible for the species difference in bile acid metabolism between mice and humans. Journal of Lipid Research 2016, 57, 2130–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falany, C.N.; Fortinberry, H.; Leiter, E.H.; Barnes, S. Cloning, expression, and chromosomal localization of mouse liver bile acid CoA:amino acid N-acyltransferase. Journal of Lipid Research 1997, 38, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, P.; Daita, K.; Joyce, A.; Mirshahi, F.; Santhekadur, P.K.; Cazanave, S.; Luketic, V.A.; Siddiqui, M.S.; Boyett, S.; Min, H.K.; et al. The presence and severity of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is associated with specific changes in circulating bile acids. Hepatology 2018, 67, 534–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzych, G.; Chávez-Talavera, O.; Descat, A.; Thuillier, D.; Verrijken, A.; Kouach, M.; Legry, V.; Verkindt, H.; Raverdy, V.; Legendre, B.; et al. NASH-related increases in plasma bile acid levels depend on insulin resistance. Jhep Reports 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez-Talavera, O.; Haas, J.; Grzych, G.; Tailleux, A.; Staels, B. Bile acid alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: what do the human studies tell? Current Opinion in Lipidology 2019, 30, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, N.; Baker, S.S.; Chapa-Rodriguez, A.; Liu, W.S.; Nugent, C.A.; Tsompana, M.; Mastrandrea, L.; Buck, M.J.; Baker, R.D.; Genco, R.J.; et al. Suppressed hepatic bile acid signalling despite elevated production of primary and secondary bile acids in NAFLD. Gut 2018, 67, 1881–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreuder, T.; Marsman, H.A.; Lenicek, M.; van Werven, J.R.; Nederveen, A.J.; Jansen, P.L.M.; Schaap, F.G. The hepatic response to FGF19 is impaired in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 2010, 298, G440–G445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lake, A.D.; Novak, P.; Shipkova, P.; Aranibar, N.; Robertson, D.; Reily, M.D.; Lu, Z.Q.; Lehman-McKeeman, L.D.; Cherrington, N.J. Decreased hepatotoxic bile acid composition and altered synthesis in progressive human nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2013, 268, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikegami, T.; Hyogo, H.; Honda, A.; Miyazaki, T.; Tokushige, K.; Hashimoto, E.; Inui, K.; Matsuzaki, Y.; Tazuma, S. Increased serum liver X receptor ligand oxysterols in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Gastroenterology 2012, 47, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raselli, T.; Hearn, T.; Wyss, A.; Atrott, K.; Peter, A.; Frey-Wagner, I.; Spalinger, M.R.; Maggio, E.M.; Sailer, A.W.; Schmitt, J.; et al. Elevated oxysterol levels in human and mouse livers reflect nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of Lipid Research 2019, 60, 1270–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromenty, B.; Roden, M. Mitochondrial alterations in fatty liver diseases. Journal of Hepatology 2023, 78, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koliaki, C.; Szendroedi, J.; Kaul, K.; Jelenik, T.; Nowotny, P.; Jankowiak, F.; Herder, C.; Carstensen, M.; Krausch, M.; Knoefel, W.T.; et al. Adaptation of Hepatic Mitochondrial Function in Humans with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Is Lost in Steatohepatitis. Cell Metabolism 2015, 21, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.P.; Cunningham, R.P.; Meers, G.M.; Johnson, S.A.; Wheeler, A.A.; Ganga, R.R.; Spencer, N.M.; Pitt, J.B.; Diaz-Arias, A.; Swi, A.I.A.; et al. Compromised hepatic mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation and reduced markers of mitochondrial turnover in human NAFLD. Hepatology 2022, 76, 1452–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancheva, S.; Kahl, S.; Pesta, D.; Mastrototaro, L.; Dewidar, B.; Strassburger, K.; Sabah, E.; Esposito, I.; Weiss, J.; Sarabhai, T.; et al. Impaired Hepatic Mitochondrial Capacity in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Associated With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care 2022, 45, 928–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Carreras, M.; Del Hoyo, P.; Martín, M.A.; Rubio, J.C.; Martín, A.; Castellano, G.; Colina, F.; Arenas, J.; Solis-Herruzo, J.A. Defective hepatic mitochondrial respiratory chain in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2003, 38, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam-Vizi, V.; Chinopoulos, C. Bioenergetics and the formation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2006, 27, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loboda, A.; Damulewicz, M.; Pyza, E.; Jozkowicz, A.; Dulak, J. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative stress response and diseases: an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2016, 73, 3221–3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrigno, A.; Campagnoli, L.I.M.; Barbieri, A.; Marchesi, N.; Pascale, A.; Croce, A.C.; Vairetti, M.; Di Pasqua, L.G. MCD Diet Modulates HuR and Oxidative Stress-Related HuR Targets in Rats. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.W.; McKeen, T.; Zhang, J.H.; Ding, W.X. Role and Mechanisms of Mitophagy in Liver Diseases. Cells 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, N.; Komatsu, M. Autophagy: Renovation of Cells and Tissues. Cell 2011, 147, 728–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filali-Mouncef, Y.; Hunter, C.; Roccio, F.; Zagkou, S.; Dupont, N.; Primard, C.; Proikas-Cezanne, T.; Reggiori, F. The menage a trois of autophagy, lipid droplets and liver disease. Autophagy 2022, 18, 50–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.H.; Palanisamy, K.; Sun, K.T.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.M.; Lin, F.Y.; Chen, K.B.; Wang, I.K.; Yu, T.M.; Li, C.Y. Human antigen R regulates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in renal tubular cells through PARKIN/BNIP3L expressions. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2021, 25, 2691–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, E.; Kim, C.; Kang, H.; Ahn, S.; Jung, M.; Hong, Y.; Tak, H.; Lee, S.; Kim, W.; Lee, E.K. RNA Binding Protein HuR Promotes Autophagosome Formation by Regulating Expression of Autophagy-Related Proteins 5, 12, and 16 in Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells (vol 39, e00508-18, 2020). Molecular and Cellular Biology 2021, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.L.; Chen, J.C.; Jiang, H.; Li, N.; Li, X.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Zong, C. Hepatocyte-Specific HuR Protects Against Acetaminophen-Induced Liver Injury in Mice. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2024, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, J.P.; Hernández-Rocha, C.; Morales, C.; Vargas, J.I.; Solís, N.; Pizarro, M.; Robles, C.; Sandoval, D.; Ponthus, S.; Benítez, C.; et al. Serum cytokeratin-18 fragment levels as noninvasive marker of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in the chilean population. Gastroenterologia Y Hepatologia 2017, 40, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simion, V.; Zhou, H.Y.; Haemmig, S.; Pierce, J.B.; Mendes, S.; Tesmenitsky, Y.; Pérez-Cremades, D.; Lee, J.F.; Chen, A.F.; Ronda, N.; et al. A macrophage-specific lncRNA regulates apoptosis and atherosclerosis by tethering HuR in the nucleus. Nature Communications 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Gorospe, M. Posttranscriptional regulation of cancer traits by HuR. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Rna 2010, 1, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, K.; Lal, A.; Kim, H.H.; Gorospe, M. Posttranscriptional orchestration of an anti-apoptotic program by HuR. Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 1288–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldstein, A.E.; Canbay, A.; Angulo, P.; Taniai, M.; Burgart, L.J.; Lindor, K.D.; Gores, G.J. Hepatocyte apoptosis and Fas expression are prominent features of human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2003, 125, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, F.; Fernández, A.; De Lacy, A.M.; Fernández-Checa, J.C.; Caballería, J.; García-Ruiz, C. Enhanced free cholesterol, SREBP-2 and StAR expression in human NASH. Journal of Hepatology 2009, 50, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, S.H.; Kohli, R.; Gores, G.J. Mechanisms of Lipotoxicity in NAFLD and Clinical Implications. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2011, 53, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhouri, N.; Carter-Kent, C.; Feldstein, A.E. Apoptosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2011, 5, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, H.; Barreyro, F.J.; Isomoto, H.; Bronk, S.F.; Gores, G.J. Free fatty acids sensitise hepatocytes to TRAIL mediated cytotoxicity. Gut 2007, 56, 1124–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, H.; Bronk, S.F.; Werneburg, N.W.; Gores, G.J. Free fatty acids induce JNK-dependent hepatocyte lipoapoptosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 12093–12101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.F.; Berkova, Z.; Mathur, R.; Sehgal, L.; Khashab, T.; Tao, R.H.; Ao, X.; Feng, L.; Sabichi, A.L.; Blechacz, B.; et al. HuR Suppresses Fas Expression and Correlates with Patient Outcome in Liver Cancer. Molecular Cancer Research 2015, 13, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachliotis, I.D.; Polyzos, S.A. The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Current Obesity Reports 2023, 12, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertunc, M.E.; Hotamisligil, G.S. Lipid signaling and lipotoxicity in metaflammation: indications for metabolic disease pathogenesis and treatment. Journal of Lipid Research 2016, 57, 2099–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beutler, B.; Cerami, A. The biology of cachectin/TNF--a primary mediator of the host response. Annu Rev Immunol 1989, 7, 625–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sedlyarov, V.; Fallmann, J.; Ebner, F.; Huemer, J.; Sneezum, L.; Ivin, M.; Kreiner, K.; Tanzer, A.; Vogl, C.; Hofacker, I.; et al. Tristetraprolin binding site atlas in the macrophage transcriptome reveals a switch for inflammation resolution. Molecular Systems Biology 2016, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedje, C.; Ronkina, N.; Tehrani, M.; Dhamija, S.; Laass, K.; Holtmann, H.; Kotlyarov, A.; Gaestel, M. The p38/MK2-Driven Exchange between Tristetraprolin and HuR Regulates AU-Rich Element-Dependent Translation. Plos Genetics 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, J.L.E.; Wait, R.; Mahtani, K.R.; Sully, G.; Clark, A.R.; Saklatvala, J. The 3′ untranslated region of tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA is a target of the mRNA-stabilizing factor HuR. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2001, 21, 721–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsam, S.S.; Ghanem, S.K.; Zahid, M.A.; Abunada, H.H.; Bader, L.; Raiq, H.; Khan, A.; Parray, A.; Djouhri, L.; Agouni, A. Human antigen R: Exploring its inflammatory response impact and significance in cardiometabolic disorders. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2024, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiakouvaki, A.; Dimitriou, M.; Karakasiliotis, I.; Eftychi, C.; Theocharis, S.; Kontoyiannis, D.L. Myeloid cell expression of the RNA-binding protein HuR protects mice from pathologic inflammation and colorectal carcinogenesis. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2012, 122, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, W.J.; Ni, C.W.; Zheng, Z.L.; Chang, K.; Jo, H.; Bao, G. HuR regulates the expression of stress-sensitive genes and mediates inflammatory response in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2010, 107, 6858–6863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.S.; Ishmael, F.T.; Fang, X.; Myers, A.; Cheadle, C.; Huang, S.K.; Atasoy, U.; Gorospe, M.; Stellato, C. Chemokine Transcripts as Targets of the RNA-Binding Protein HuR in Human Airway Epithelium. Journal of Immunology 2011, 186, 2482–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, K.; Chung, H.K.; Softic, S.; Moreno-Fernandez, M.E.; Divanovic, S. The bidirectional immune crosstalk in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Cell Metabolism 2023, 35, 1852–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syn, W.K.; Oo, Y.H.; Pereira, T.A.; Karaca, G.F.; Jung, Y.M.; Omenetti, A.; Witek, R.P.; Choi, S.S.; Guy, C.D.; Fearing, C.M.; et al. Accumulation of Natural Killer T Cells in Progressive Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology 2010, 51, 1998–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadaki, O.; Milatos, S.; Grammenoudi, S.; Mukherjee, N.; Keene, J.D.; Kontoyiannis, D.L. Control of Thymic T Cell Maturation, Deletion and Egress by the RNA-Binding Protein HuR. Journal of Immunology 2009, 182, 6779–6788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Martindale, J.L.; Abdelmohsen, K.; Kumar, G.; Fortina, P.M.; Gorospe, M.; Rostami, A.; Yu, S.G. RNA-Binding Protein HuR Promotes Th17 Cell Differentiation and Can Be Targeted to Reduce Autoimmune Neuroinflammation. Journal of Immunology 2020, 204, 2076–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, P.; Kleiner, D.E.; Dam-Larsen, S.; Adams, L.A.; Bjornsson, E.S.; Charatcharoenwitthaya, P.; Mills, P.R.; Keach, J.C.; Lafferty, H.D.; Stahler, A.; et al. Liver Fibrosis, but No Other Histologic Features, Is Associated With Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar-Gomez, E.; Calzadilla-Bertot, L.; Wong, V.W.S.; Castellanos, M.; Aller-de la Fuente, R.; Metwally, M.; Eslam, M.; Gonzalez-Fabian, L.; Sanz, M.A.Q.; Conde-Martin, A.F.; et al. Fibrosis Severity as a Determinant of Cause-Specific Mortality in Patients With Advanced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Multi-National Cohort Study. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angulo, P.; Machado, M.V.; Diehl, A.M. Fibrosis in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Seminars in Liver Disease 2015, 35, 132–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwabe, R.F.; Tabas, I.; Pajvani, U.B. Mechanisms of Fibrosis Development in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1913–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, C.R. Hepatology Snapshot: Hepatic stellate cell activation and pro-fibrogenic signals. Journal of Hepatology 2017, 67, 1104–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.Y.; Kim, K.; Wang, X.B.; Bartolome, A.; Salomao, M.; Dongiovanni, P.; Meroni, M.; Graham, M.J.; Yates, K.P.; Diehl, A.M.; et al. Hepatocyte Notch activation induces liver fibrosis in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Science Translational Medicine 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.J.Y.; Liu, R.P.; Yang, J.; Sun, L.X.; Zhang, L.Y.; Jiang, Z.Z.; Puri, P.; Gurley, E.C.; Lai, G.H.; Tang, Y.P.; et al. The Role of Long Noncoding RNA H19 in Gender Disparity of Cholestatic Liver Injury in Multidrug Resistance 2 Gene Knockout Mice. Hepatology 2017, 66, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.P.; Li, X.J.Y.; Zhu, W.W.; Wang, Y.Y.; Zhao, D.; Wang, X.; Gurley, E.C.; Liang, G.; Chen, W.D.; Lai, G.H.; et al. Cholangiocyte-Derived Exosomal Long Noncoding RNA H19 Promotes Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Cholestatic Liver Fibrosis. Hepatology 2019, 70, 1317–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.L.; Yao, Z.; Wang, L.; Ding, H.; Shao, J.J.; Chen, A.P.; Zhang, F.; Zheng, S.Z. Activation of ferritinophagy is required for the RNA-binding protein ELAVL1/HuR to regulate ferroptosis in hepatic stellate cells. Autophagy 2018, 14, 2083–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherry, J.; Karschner, V.; Jones, H.; Pekala, P.H. HuR, an RNA-binding protein, involved in the control of cellular differentiation. In Vivo 2006, 20, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, I.; Hur, J.; Jeong, S. HuR represses Wnt/β-catenin-mediated transcriptional activity by promoting cytoplasmic localization of β-catenin. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2015, 457, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2019, 15, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.P.; Wu, W.Y.; Ma, C.F.; Du, C.Y.; Huang, Y.R.; Xu, H.X.; Li, C.C.; Cheng, X.F.; Hao, R.J.; Xu, Y.J. RNA-Binding Proteins in the Regulation of Adipogenesis and Adipose Function. Cells 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.S.; Lee, W.J.; Hur, J.; Lee, H.G.; Kim, E.; Lee, G.H.; Choi, M.J.; Lim, D.S.; Paek, K.S.; Seo, H.G. Rosiglitazone-dependent dissociation of HuR from PPAR-γ regulates adiponectin expression at the posttranscriptional level. Faseb Journal 2019, 33, 7707–7720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, A.R.; Anthony, S.R.; Gozdiff, A.; Green, L.C.; Fleifil, S.M.; Slone, S.; Nieman, M.L.; Alam, P.; Benoit, J.B.; Owens, A.P.; et al. Adipocyte-specific deletion of HuR induces spontaneous cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2021, 321, H228–H241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Han, J.; Wang, H.Y.; Meng, Q.Y.; Chen, L.L.; Liu, Y.G.; Feng, Y.; Wu, G.H. Cachexia-related long noncoding RNA, CAAlnc1, suppresses adipogenesis by blocking the binding of HuR to adipogenic transcription factor mRNAs. International Journal of Cancer 2019, 145, 1809–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, E.; Marengo, A.; Mezzabotta, L.; Bugianesi, E. Systemic Complications of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: When the Liver Is Not an Innocent Bystander. Seminars in Liver Disease 2015, 35, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Corey, K.E.; Byrne, C.D.; Roden, M. The complex link between NAFLD and type 2 diabetes mellitus - mechanisms and treatments. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2021, 18, 599–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Day, C.P.; Bonora, E. Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients with Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2010, 363, 1341–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, E.D.; Lin, J.N.C.; Mahoney, T.; Ume, N.; Yang, G.C.; Gabbay, R.A.; ElSayed, N.A.; Bannuru, R.R. Economic Costs of Diabetes in the US in 2022. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, J.M.; Cooper, M.E. MECHANISMS OF DIABETIC COMPLICATIONS. Physiological Reviews 2013, 93, 137–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Zhang, Z.G.; Zheng, C.; Wintergerst, K.A.; Keller, B.B.; Cai, L. Mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy and potential therapeutic strategies: preclinical and clinical evidence. Nature Reviews Cardiology 2020, 17, 585–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Bruin, R.G.; Rabelink, T.J.; van Zonneveld, A.J.; van der Veer, E.P. Emerging roles for RNA-binding proteins as effectors and regulators of cardiovascular disease. European Heart Journal 2017, 38, 1380–1388D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Jiang, M.Y.; Cao, Y.P.; Zhang, Z.J.; Jiang, B.; Tian, F.; Feng, J.; Dou, Y.L.; Gorospe, M.; Zheng, M.; et al. HuR regulates phospholamban expression in isoproterenol-induced cardiac remodelling. Cardiovascular Research 2020, 116, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slone, S.; Anthony, S.R.; Green, L.C.; Parkins, S.; Acharya, P.; Kasprovic, D.A.; Reynolds, K.; Jaggers, R.M.; Nieman, M.L.; Alam, P.; et al. HuR inhibition reduces post-ischemic cardiac remodeling by dampening myocyte-dependent inflammatory gene expression and the innate immune response. Faseb Journal 2025, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.C.; Slone, S.; Anthony, S.R.; Guarnieri, A.R.; Parkins, S.; Shearer, S.M.; Nieman, M.L.; Roy, S.; Aube, J.; Wu, X.Q.; et al. HuR-dependent expression of Wisp1 is necessary for TGFβ-induced cardiac myofibroblast activity. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology 2023, 174, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindappa, P.K.; Patil, M.; Garikipati, V.N.S.; Verma, S.K.; Saheera, S.; Narasimhan, G.; Zhu, W.Q.; Kishore, R.; Zhang, J.Y.; Krishnamurthy, P. Targeting exosome-associated human antigen R attenuates fibrosis and inflammation in diabetic heart. Faseb Journal 2020, 34, 2238–2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, L.C.; Anthony, S.R.; Slone, S.; Lanzillotta, L.; Nieman, M.L.; Wu, X.Q.; Robbins, N.; Jones, S.M.; Roy, S.; Owens, A.P.; et al. Human antigen R as a therapeutic target in pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Jci Insight 2019, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, M.; Singh, S.; Dubey, P.K.; Tousif, S.; Umbarkar, P.; Zhang, Q.K.; Lal, H.; Sewell-Loftin, M.K.; Umeshappa, C.S.; Ghebre, Y.T.; et al. Fibroblast-Specific Depletion of Human Antigen R Alleviates Myocardial Fibrosis Induced by Cardiac Stress. Jacc-Basic to Translational Science 2024, 9, 754–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Lambers, E.; Verma, S.; Thorne, T.; Qin, G.J.; Losordo, D.W.; Kishore, R. Myocardial knockdown of mRNA-stabilizing protein HuR attenuates post-MI inflammatory response and left ventricular dysfunction in IL-10-null mice. Faseb Journal 2010, 24, 2484–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachiondo-Ortega, S.; Delgado, T.C.; Baños-Jaime, B.; Velázquez-Cruz, A.; Díaz-Moreno, I.; Martinez-Chantar, M.L. Hu Antigen R (HuR) Protein Structure, Function and Regulation in Hepatobiliary Tumors. Cancers 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, K.; Patel, M.M. Insights on drug and gene delivery systems in liver fibrosis. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, M.; Chakraborty, P.; Mohan, S.; Mehrotra, S.; Palanisamy, V. HuR as a molecular target for cancer therapeutics and immune-related disorders. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2022, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).