Clinical Implications

This study establishes a novel, reliable preclinical method for assessing orthodontic aligner efficacy before clinical trials. Furthermore, it provides experimental confirmation that 3D-printed aligners can correct anterior tooth rotations of varying severities without attachments. Moreover, aligner thickness was shown to influence the rate—but not the final extent—of correction, allowing clinicians to tailor treatment pacing (e.g., faster initial movement versus steadier progression) to individual patient needs.

Introduction

A clear orthodontic aligner is a custom-made plastic device used to correct mild to moderate tooth misalignments gradually [

1]. Due to the rigidity of the plastic, each aligner can only achieve small tooth movements. Therefore, a series of multiple aligners is required for effective realignment, each showing slight incremental movements [

2]. This method becomes labor-intensive and impractical for cases requiring an excessive number of aligners and consuming a large amount of plastic [

3]. With the advent of digital scanning, 3D printing, and CAD-CAM technology, orthodontic aligners have become more precise [

4]. Researchers are continually working to enhance treatment effectiveness through various improvements, breakthroughs, and advancements aimed at simplifying the procedure and reducing both its duration and cost [

5].

In spite of the extensive research on aligner biomechanics, discrepancies between planned and actual results persist [

6,

7]. Moreover, a definitive geometry for optimizing aligner modifications to accommodate various tooth movements has not been endorsed. Hence, further studies are needed to enhance the evidence and predictability of bodily movement and torque control with aligners [

8]. The accuracy of orthodontic aligners treatment was reported to be affected by many factors such as aligner material [

9], activation and staging [

10,

11,

12], thickness [

13], as well as edge extension and trimming design [

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, considering the mechanisms governing orthodontic aligner functionality, not all forms of tooth movement can be feasibly achieved solely through the application of aligners [

7,

8].

The properties of the aligner materials are crucial in determining their mechanical and clinical characteristics [

18,

19]. Traditional manufacturing methods using thermoforming have been found to negatively affect the mechanical properties of aligner materials [

20,

21]. Hence, the 3D-printing of aligners has recently been introduced to eliminate the cumulative errors associated with the conventional thermoforming workflow [

22,

23,

24,

25], enhance precision, offer greater control over aligner design and thickness [

16], reduce material waste, and decrease production costs [

26].

The orthodontic aligners have been investigated via several numerical and experimental strategies, including finite element analysis [

27], direct force measurements with sensors [

28], pressure-sensitive films [

29], and customized biomechanical setup [

30]. Additional evaluation techniques include photoelastic stress analysis [

31], digital image correlation for full-field strain mapping [

32], and optical-tracking systems on typodonts [

33]. Typodonts act as sensor-free pre-clinical models for screening the performance of sequential orthodontic aligners [

34].

The current study introduced a novel methodology utilizing an electrically controlled typodont to evaluate the performance of 3D-printed aligners in achieving controlled tooth movements. This advanced electric typodont offers several practical advantages for orthodontic simulation. Unlike traditional models, it eliminates the need for hot water baths and allows real-time visualization of tooth movement. Moreover, electrically controlled heating begins at the root level, simulating natural tooth displacement more accurately. Furthermore, its wax system mimics anatomical structures by using harder wax for cortical bone and softer wax for spongiosa. This clean, quick, and user-friendly device is ideal for experimental research purposes and provides flexible setup options, making it efficient to operate.

Materials and Methods

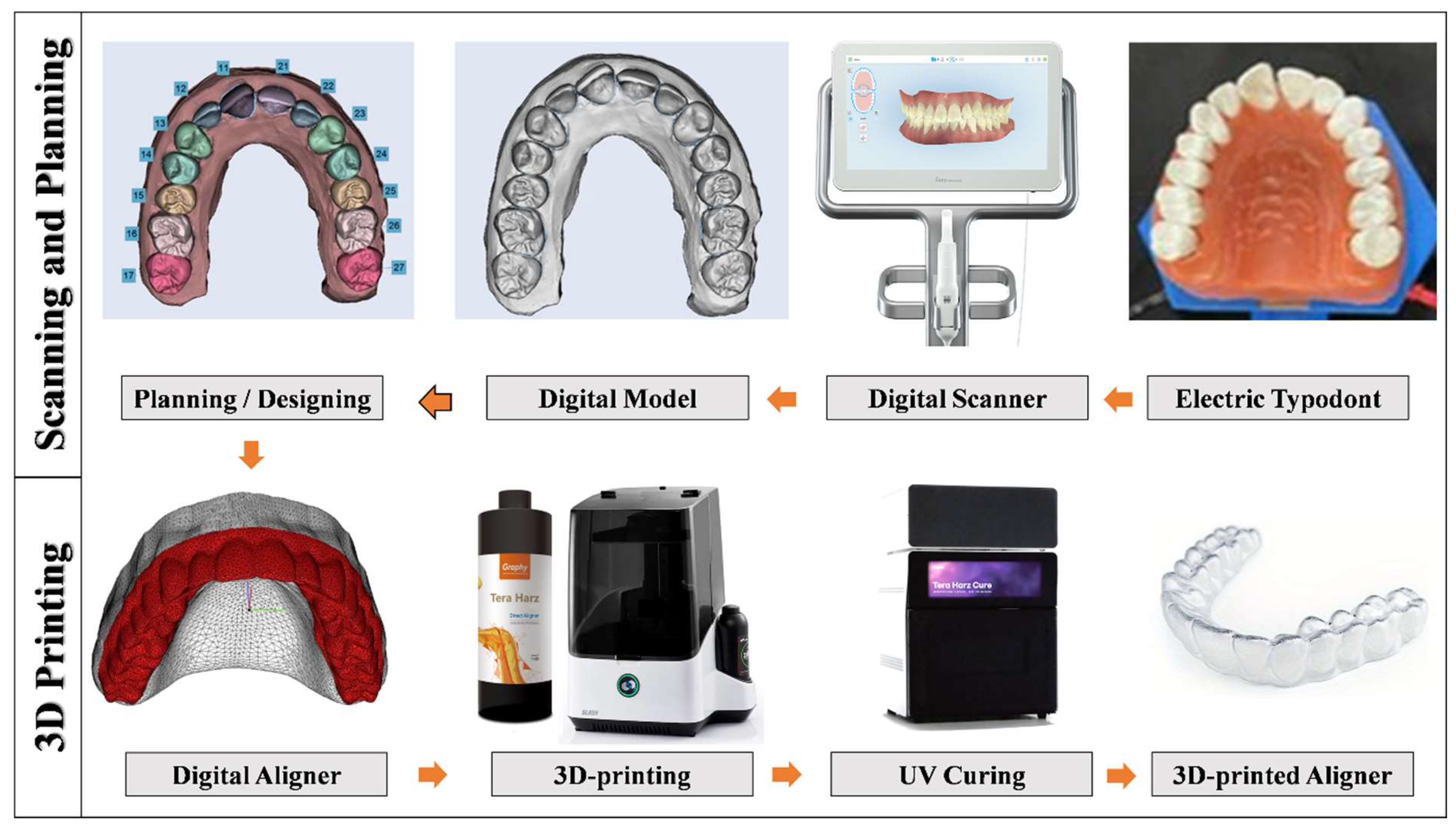

An electric typodont (Electro-Dont; Savaria-Dent, Budapest, Hungary) (

Figure 1) was used to simulate the different degrees of rotation of the upper right central incisor (Tooth 11) as selected in the current study. This electric typodont consists of upper and lower full arches of acrylic teeth embedded in wax, each tooth is surrounded by an electric coil connected to an external electric circuit controlled by an adjustable timer. When the circuit is turned on, the electrical power is transferred into heat to melt the wax around the teeth slowly and allow for pre-planned movement. Then a cooling cycle (same duration as the heating cycle) is automatically starting to slowly allow the wax around the teeth to harden and keep the teeth in their new positions.

The typodont was then scanned using an iTero scanner (Align Technology, San Jose, CA, USA) to create a digital replica in a standard tessellation format (STL). The STL file was exported to Maestro 3D Ortho Studio software (AGE Solutions, Pontedera, Italy) for virtual setup and digital planning of the desired tooth movement with each aligner. Using Maestro software, the degree of rotation, tip, torque, and center of rotation were adjusted as per the desired tooth movement and treatment plan, and then the design of the clear aligner was performed.

A total of 240 3D-printed aligners were used. They were divided into three main groups (n=80 for each group) based on the thickness of each aligner: Group 1 (0.50 mm-thick), Group 2 (0.75 mm-thick), and Group 3 (1.00 mm-thick). Each group was further subdivided according to the degree of rotation of Tooth 11 into four equal subgroups (n=5 for each subgroup) (

Figure 2): simple rotation (22°), mild rotation (32°), moderate rotation (42°), and severe rotation (52°) (

Figure 3). Four aligners (Aligners 1-4) were then designed for each subgroup to fully correct the varying degrees of rotation of Tooth 11 by the end of using Aligner 4. Additionally, four rigid guiding stents were printed using a resin material (Grey Resin 1 L; Formlabs, Somerville, MA, USA) to adjust the initial rotation of Tooth 11 for each subgroup before beginning the test cycle.

All aligners were fabricated using Tera Harz TC-85

1 resin (Graphy, Seoul, South Korea) and 3D-printed using a DLP-type 3D printer (Uniz NBEE; Uniz, CA, USA), with a layer thickness of 100 µ, and using a 2-mm extended straight trimming line design. They were then photo-cured with UV light at a wavelength of 405 nm under nitrogen conditions for 25 minutes using Tera Harz Cure (Graphy, Seoul, South Korea), as per the manufacturer’s recommendations (

Figure 4).

After seating the aligner over the teeth, the ElectroDont was activated, initiating a 10-minute heating cycle followed by a 10-minute cooling cycle. Subsequently, the ElectroDont was immersed in room temperature water for an additional 2 minutes to ensure thorough cooling. Once the cooling cycle was complete, the aligner was carefully removed to avoid any unintended tooth movement, and the ElectroDont was scanned. At the end of each test cycle, the rotation of Tooth 11 was adjusted to its initial test position using the appropriate guiding stent.

To measure the degree of rotation, a straight stainless-steel wire was placed tangent to the incisal edge of the rotated Tooth 11, secured with a small drop of wax. A baseline was established by connecting the midpoint of the incisal edge of Tooth 11 with the mesial marginal ridge of Tooth 21 (marked with a pen point). The angle between the incisal edge of the rotated Tooth 11 and the baseline was measured using a protractor (

Figure 4). These steps were consistently repeated for each aligner in all case scenarios. For reliability assessment, the entire experimental procedure was repeated 5 times across all subgroups (n=5).

Figure 5.

Measurement of the degree of rotation of Tooth 11 using a protractor.

Figure 5.

Measurement of the degree of rotation of Tooth 11 using a protractor.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 28.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For comparisons of two related, normally distributed variables, paired t-tests were used. Repeated measures were evaluated by a General Linear Model (GLM) repeated-measures ANOVA, with post-hoc pairwise comparisons conducted using the least significant difference (LSD) method. All tests were two-tailed, and a P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Top of Form

Results

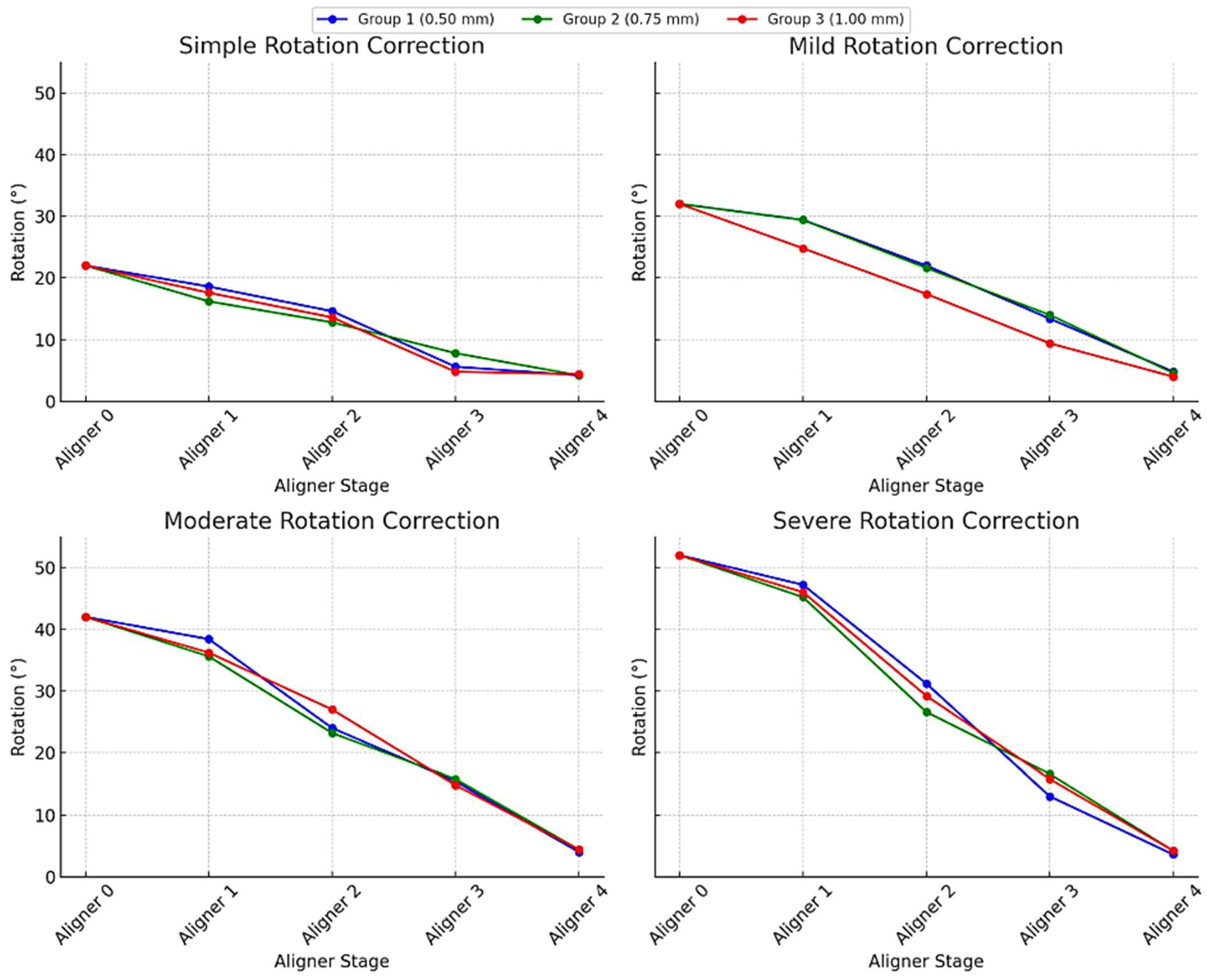

As presented in

Figure 6, by the final aligner stage (Aligner 4), all three thicknesses achieved nearly complete correction, with residual rotations narrowed to just 4–5°. However, the pathways they took to get there differed slightly depending on aligner thickness and the severity of the initial rotation.

For the mildest cases (initial 22° rotation), the 0.50 mm and 1.00 mm aligners delivered larger early gains, reducing angular displacement to 14.6° and 13.6° respectively by Aligner 2, whereas the 0.75 mm aligner reached only 12.8° at the same point. Midway through treatment, the thinnest (0.50 mm) aligner made the most dramatic single-stage jump, dropping to 5.6° by Aligner 3, while the 0.75 mm and 1.00 mm aligners trailed slightly behind at 7.8° and 4.8°. Despite these differences, all three converged at roughly 4.0–4.4° residual rotation by Aligner 4.

In mild and moderate rotations (initial 32° and 42°), a similar pattern emerged. For a 32° start, the 0.50 mm and 0.75 mm aligners moved the tooth down to about 22° by Aligner 2, leaving the 1.00 mm aligner behind at 17.4°. By mid-treatment, the thinner aligners had reduced rotation by around 9°, whereas the thicker aligners gained 7.4°. In the 42° cases, the 1.00 mm aligner outpaced the others early on, dropping to 27.0° at Aligner 2 compared to 24.0° and 23.2° for the 0.50 mm and 0.75 mm aligners, yet ultimately all three reached the same 4.0–4.4° degrees.

Even severe rotations (initial 52°) followed this convergence pattern. The thinnest aligner again made the biggest early move, lowering rotation to 31.2° by Aligner 2, versus 29.2° and 26.6° for the 1.00 mm and 0.75 mm aligners. The medium-thickness aligner was then caught up by Aligner 3, and by the end, all aligners achieved residual rotations within a tight 3.6–4.4° range. In short, while the ultimate outcomes were equivalent, the 0.50 mm and 1.00 mm aligners produced faster early-stage correction, and the 0.75 mm aligners delivered a steadier, more uniform progression.

Discussion

Clear orthodontic aligners have emerged as a compelling alternative to fixed braces, offering superior aesthetics and greater patient comfort. A range of numerical and experimental approaches has been used to assess orthodontic aligner efficacy, including sensor-free typodont experiments that serve as reliable pre-clinical screening models for sequential aligner performance [

34]. In the electric wax-block typodont introduced in the present study, each tooth is seated in a heat-activated wax analogue that softens during a controlled heating cycle—mimicking the compliance of the periodontal ligament—and then rehardens during cooling, allowing the aligner’s programmed force to produce measurable tooth movement. Rapid repositioning of the tooth using rigid guiding stents enables multiple, repeatable trials, establishing the system as a reliable and efficient tool for comparing aligner designs, such as thickness or staging protocols, prior to clinical application.

Correcting incisor rotation remains one of the most unpredictable and challenging movements in orthodontics, and it is consistently more difficult with aligners than with fixed appliances [

35]. This underscores the need to understand and optimize the many factors that influence aligner performance in rotational correction. One of the controlling factors of aligner mechanical behavior is their thickness [

36]. Aligner thickness directly influences the magnitude of rotational force and, therefore, the degree of tooth movement [

30,

37]. Some clear-aligner protocols deliberately vary aligner thickness, either by prescribing different materials for specific treatment phases or by alternating thicknesses, to modulate force levels much like fixed appliances do [

30,

38,

39,

40,

41]. However, the thermoforming process itself can unpredictably alter the intended material thickness [

16] and negatively affect the mechanical and physical properties of the aligner material [

42]. To address this, advanced materials with enhanced properties have been explored to improve aligner performance [

3]. Additionally, sequential aligner systems often result in reduced efficiency, higher costs, and increased plastic waste due to the limited movement achieved per aligner, necessitating more splints per treatment. This raises both financial and environmental concerns [

5]. The integration of shape memory polymers (SMPs) and 3D printing offers a promising alternative, providing greater accuracy, cost-efficiency, and sustainability [

39,

43].

The 3D-printed aligners in this study were produced in a horizontal orientation. However, recent studies [

44,

45] reported that printing orientation has no significant effect on the mechanical properties of aligners. Moreover, all three thicknesses were UV-cured for 25 minutes following the manufacturer’s guidelines. Bleilöb et al. [

46] demonstrated that a 20-minute UV-curing protocol is sufficient to ensure biocompatibility and thus patient safety, up to 6 mm thick. Furthermore, they featured a 2 mm straight trimming line. In line with Elshazly et al.’s experimental and numerical work [

16,

37,

47], the extended straight-line design enhanced the control of tooth movement by distributing stress more evenly and delivering greater force nearer the gingival region, closer to the tooth’s center of resistance.

The results demonstrated that the novel electric typodont effectively simulates tooth derotation achieved by orthodontic aligners. Additionally, all three aligner thicknesses (0.50 mm, 0.75 mm, and 1.00 mm) effectively reduced tooth rotation across all severity levels (simple, mild, moderate, and severe) to a final residual rotation of approximately 4–5°. However, differences emerged in the early stages of treatment: the 0.50 mm and 1.00 mm aligners produced more rapid initial corrections, while the 0.75 mm aligner achieved a more gradual and consistent reduction. Despite these early differences, all groups ultimately reached comparable outcomes, with no statistically significant difference in final rotational correction. These findings contrast with previous studies [

36,

42] suggesting that increased aligner thickness results in greater contact forces and more prolonged force delivery compared to thinner aligners. However, our results align with other investigations that have reported no statistically significant differences in force generation across different thicknesses [

30,

38,

48]. This suggests that aligner thickness may have a limited impact on the overall efficacy of rotational correction, at least in the context of 3D-printed aligners. This may also reflect the inherent variability in aligner thickness caused by printing inaccuracies, exhibiting deviations between the digitally designed thickness and the actual printed outcome, as reported by Edelmann et al. [

40].

Contrary to the recommendations of some aligner companies and previous reports [

49,

50,

51,

52], the current study demonstrates the effectiveness of aligners in correcting rotated incisors with a high degree of success (up to 90%) without the use of attachments. These findings are consistent with recent studies [

47,

53,

54] indicating that clear aligners can achieve effective results without attachments, emphasizing alternative approaches such as high straight trimming line designs [

47] and varying aligner thicknesses [

55] as viable options. Moreover, the shape memory characteristics of the 3D-printed aligner material, as previously reported [

5,

56], contribute to improved adaptability [

57], prolonged force application, and the potential for greater incremental tooth movement per aligner [

43], which enhances the control of tooth movement.

This typodont experimental study has many limitations and cannot fully replicate the complex conditions of the oral environment. Factors like fluctuating temperature, salivary flow, and occlusal forces are absent and may influence aligner performance. Likewise, virtual setup and 3D printing demand specialized expertise and a rigorously standardized digital workflow. Any variation in key steps, such as tooth segmentation, aligner design, support placement, print timing, or curing, could introduce inconsistencies that alter the mechanical properties of the final aligners.

Measuring the forces and torques generated by aligners is planned in future studies. Moreover, further in vivo studies are warranted to confirm these results under clinical conditions.

Conclusion

The current in vitro study showed the following observations:

The electric typodont proved to be a reliable and cost-effective preclinical model for simulating tooth movement induced by orthodontic aligners.

3D-printed aligners successfully corrected rotated anterior teeth across varying severities in the typodont model, even without the use of auxiliary attachments.

All aligner thicknesses achieved similar final correction but differed in timing: 0.50 mm and 1.00 mm aligners showed faster early-stage movement, while 0.75 mm aligners provided more gradual, consistent correction.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement: Ammar Al Shalabi: Writing – review & editing, Investigation, Data curation. Shaima Malik: Writing – review & editing, Data curation. Hoon Kim: Writing – review & editing. Abdulaziz Alhotan: Writing – review & editing. Tarek Elshazly: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Data curation. Ahmed Ghoneima: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Resources, Data curation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from Hamdan Bin Mohammed College of Dental Medicine (HBMCDM), Mohammed Bin Rashid University of Medicine and Health Sciences (MBRU), Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Researchers Supporting Project Number (RSPD2025R790), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

This article does not contain any studies on human or animal subjects.

Notes

| 1 |

Tera Harz TC-85 resin is certified by the FDA, KFDA, and CE. |

References

- Tamer I, Öztas E, Marsan G. Orthodontic treatment with clear aligners and the scientific reality behind their marketing: a literature review. Turk J Orthod. 2019;32(4):241.

- Upadhyay M, Arqub SA. Biomechanics of clear aligners: hidden truths & first principles. J World Fed Orthod. Published online 2021.

- Elshazly TM, Keilig L, Alkabani Y, et al. Potential Application of 4D Technology in Fabrication of Orthodontic Aligners. Front Mater 8: 794536. Published online 2022. [CrossRef]

- Moutawakil A. Biomechanics of Aligners: Literature Review. Advances in Dentistry & Oral Health. 2021;13. [CrossRef]

- Atta I, Bourauel C, Alkabani Y, et al. Physiochemical and mechanical characterisation of orthodontic 3D printed aligner material made of shape memory polymers (4D aligner material). J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. Published online 2023:106337.

- Ayidauga C, Kamilouglu B. Effects of Variable Composite Attachment Shapes in Controlling Upper Molar Distalization with Aligners: A Nonlinear Finite Element Study. J Healthc Eng. 2021;2021.

- Papageorgiou SN, Koletsi D, Iliadi A, Peltomaki T, Eliades T. Treatment outcome with orthodontic aligners and fixed appliances: a systematic review with meta-analyses. Eur J Orthod. 2020;42(3):331-343.

- Elkholy F, Weber S, Repky S, Jäger R, Schmidt F, Lapatki BG. Are aligners capable of inducing palatal bodily translation or palatal root torque of upper central incisors? A biomechanical in vitro study. Clin Oral Investig. Published online 2023:1-12.

- Li F. A Standardized Characterization of the Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Orthodontic Clear Aligners. UCLA; 2020.

- Min S, Hwang CJ, Yu HS, Lee SB, Cha JY. The effect of thickness and deflection of orthodontic thermoplastic materials on its mechanical properties. The korean journal of orthodontics. 2010;40(1):16-26.

- Li X, Ren C, Wang Z, Zhao P, Wang H, Bai Y. Changes in force associated with the amount of aligner activation and lingual bodily movement of the maxillary central incisor. The Korean Journal of Orthodontics. 2016;46(2):65-72.

- Jedliński M, Mazur M, Greco M, Belfus J, Grocholewicz K, Janiszewska-Olszowska J. Attachments for the Orthodontic Aligner Treatment—State of the Art—A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5):4481.

- Liu DS, Chen YT. Effect of thermoplastic appliance thickness on initial stress distribution in periodontal ligament. Advances in Mechanical Engineering. 2015;7(4):1687814015578362.

- Gao L, Wichelhaus A. Forces and moments delivered by the PET-G aligner to a maxillary central incisor for palatal tipping and intrusion. Angle Orthod. 2017;87(4):534-541.

- Brown BE. Effect of Gingival Margin Design on Clear Aligner Material Strain and Force Delivery. University of Minnesota; 2021.

- Elshazly TM, Keilig L, Salvatori D, Chavanne P, Aldesoki M, Bourauel C. Effect of Trimming Line Design and Edge Extension of Orthodontic Aligners on Force Transmission: An in vitro Study. J Dent. Published online 2022:104276. [CrossRef]

- Elshazly TM, Salvatori D, Elattar H, Bourauel C, Keilig L. Effect of trimming line design and edge extension of orthodontic aligners on force transmission: A 3D finite element study. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. Published online 2023:105741. [CrossRef]

- Cremonini F, Vianello M, Bianchi A, Lombardo L. A Spectrophotometry Evaluation of Clear Aligners Transparency: Comparison of 3D-Printers and Thermoforming Disks in Different Combinations. Applied Sciences. 2022;12(23):11964.

- Momtaz P. The Effect of Attachment Placement and Location on Rotational Control of Conical Teeth Using Clear Aligner Therapy. Published online 2016.

- Golkhani B, Weber A, Keilig L, Reimann S, Bourauel C. Variation of the modulus of elasticity of aligner foil sheet materials due to thermoforming. Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics/Fortschritte der Kieferorthopädie. 2022;83(4):233-243.

- Dalaie K, Fatemi SM, Ghaffari S. Dynamic mechanical and thermal properties of clear aligners after thermoforming and aging. Prog Orthod. 2021;22:1-11.

- Koenig N, Choi JY, McCray J, Hayes A, Schneider P, Kim KB. Comparison of dimensional accuracy between direct-printed and thermoformed aligners. The Korean Journal of Orthodontics. Published online 2022.

- Shivapuja P kumar, Shah D, Shah N, Shah S. Direct 3D-printed orthodontic aligners with torque, rotation, and full control anchors. Published online 2019.

- Lee SY, Kim H, Kim HJ, et al. Thermo-mechanical properties of 3D printed photocurable shape memory resin for clear aligners. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1-10.

- Tartaglia GM, Mapelli A, Maspero C, et al. Direct 3D printing of clear orthodontic aligners: Current state and future possibilities. Materials. 2021;14(7):1799.

- Peeters B, Kiratli N, Semeijn J. A barrier analysis for distributed recycling of 3D printing waste: Taking the maker movement perspective. J Clean Prod. 2019;241:118313.

- Elshazly TM, Bourauel CP, Aldesoki M, et al. Computer-aided finite element model for biomechanical analysis of orthodontic aligners. Clin Oral Investig. 2023;27(1). [CrossRef]

- Xiang B, Wang X, Wu G, et al. The force effects of two types of polyethylene terephthalate glyc-olmodified clear aligners immersed in artificial saliva. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1-10.

- Elshazly TM, Bourauel CP, Ismail AM, et al. Effect of material composition and thickness of orthodontic aligners on the transmission and distribution of forces: an in vitro study. Clin Oral Investig. 2024;28(5). [CrossRef]

- Elkholy F, Schmidt F, Jäger R, Lapatki BG. Forces and moments applied during derotation of a maxillary central incisor with thinner aligners: an in-vitro study. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics. 2017;151(2):407-415.

- Hamanaka T, Nakamura Y. Photoelastic analysis of clear aligner stress distribution. Angle Orthodontist. 2016;86(3):342-347.

- Maia M ~M., França K ~M. Digital image correlation for full-field strain mapping of orthodontic aligners. J Biomech. 2020;98:109518.

- Li W, Wang L. Optical tracking of tooth movement in in vitro typodont models. Dental Materials. 2018;34(10):1487-1494.

- Elshazly TM, Keilig L, Alkabani Y, et al. Primary evaluation of shape recovery of orthodontic aligners fabricated from shape memory polymer (A typodont study). Dent J (Basel). 2021;9(3). [CrossRef]

- Bowman SJ. Drastic plastic: Enhancing the predictability of clear aligners. In: Controversial Topics in Orthodontics: Can We Reach Consensus?. ; 2020:219-249.

- Ghoraba O, Bourauel CP, Aldesoki M, et al. Effect of the Height of a 3D-Printed Model on the Force Transmission and Thickness of Thermoformed Orthodontic Aligners. Materials. 2024;17(12). [CrossRef]

- Elshazly TM, Bourauel CP, Chavanne P, Elattar HS, Keilig L. Numerical biomechanical finite element analysis of different trimming line designs of orthodontic aligners: An in silico study. J World Fed Orthod. 2024;13(2). [CrossRef]

- Bucci R, Rongo R, Levatè C, et al. Thickness of orthodontic clear aligners after thermoforming and after 10 days of intraoral exposure: a prospective clinical study. Prog Orthod. 2019;20(1):1-8.

- Jindal P, Worcester F, Siena FL, Forbes C, Juneja M, Breedon P. Mechanical behaviour of 3D printed vs thermoformed clear dental aligner materials under nonlinear compressive loading using FEM. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2020;112:104045.

- Edelmann A, English JD, Chen S -J., Kasper FK. Analysis of the thickness of 3-dimensional-printed orthodontic aligners. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2020;158(5):e91--e98.

- Iliadi A, Koletsi D, Eliades T. Forces and moments generated by aligner-type appliances for orthodontic tooth movement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2019;22(4):248-258.

- Ryu JH, Kwon JS, Jiang HB, Cha JY, Kim KM. Effects of thermoforming on the physical and mechanical properties of thermoplastic materials for transparent orthodontic aligners. The Korean Journal of Orthodontics. 2018;48(5):316-325.

- Sharif M, Bourauel C, Ghoneima A, Schwarze J, Alhotan A, Elshazly TM. Force system of 3D-printed orthodontic aligners made of shape memory polymers: an in vitro study. Virtual Phys Prototyp. 2024;19(1):e2361857.

- McCarty MC, Chen S -J., English JD, Kasper FK. Effect of print orientation and duration of ultraviolet curing on the dimensional accuracy of a 3-dimensionally printed orthodontic clear aligner design. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 2020;158(6):889-897.

- Camenisch L, Polychronis G, Panayi N, et al. Effect of printing orientation on mechanical properties of 3D-printed orthodontic aligners. Journal of Orofacial Orthopedics/Fortschritte der Kieferorthopädie. Published online 2024:1-8.

- Bleilöb M, Welte-Jzyk C, Knode V, Ludwig B, Erbe C. Biocompatibility of variable thicknesses of a novel directly printed aligner in orthodontics. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):3279.

- Elshazly TM, Bourauel CP, Aldesoki M, et al. Effect of attachment configuration and trim line design on the force system of orthodontic aligners: A finite element study on the upper central incisor. Orthod Craniofac Res. Published online 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gao L, Wichelhaus A. Forces and moments delivered by the PET-G aligner to a maxillary central incisor for palatal tipping and intrusion. Angle Orthod. 2017;87(4):534-541.

- Cortona A, Rossini G, Parrini S, Deregibus A, Castroflorio T. Clear aligner orthodontic therapy of rotated mandibular round-shaped teeth: a finite element study. Angle Orthod. 2020;90(2):247-254.

- Jones ML, Mah J, O’Toole BJ. Retention of thermoformed aligners with attachments of various shapes and positions. J Clin Orthod. 2009;43(2):113-117.

- Jedliński M, Mazur M, Greco M, Belfus J, Grocholewicz K, Janiszewska-Olszowska J. Attachments for the Orthodontic Aligner Treatment—State of the Art—A Comprehensive Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(5):4481.

- Gomez JP, Peña FM, Martinez V, Giraldo DC, Cardona CI. Initial force systems during bodily tooth movement with plastic aligners and composite attachments: A three-dimensional finite element analysis. Angle Orthod. 2015;85(3):454-460.

- Kravitz ND, Kusnoto B, Agran B, Viana G. Influence of attachments and interproximal reduction on the accuracy of canine rotation with Invisalign: a prospective clinical study. Angle Orthod. 2008;78(4):682-687.

- Simon M, Keilig L, Schwarze J, Jung BA, Bourauel C. Treatment outcome and efficacy of an aligner technique–regarding incisor torque, premolar derotation and molar distalization. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14(1):1-7.

- Putrino A, Abed M -R., Lilli C. Clear aligners with differentiated thickness and without attachments—A case report. J Clin Exp Dent. 2022;14(6):e514.

- Lee SY, Kim H, Kim HJ, et al. Thermo-mechanical properties of 3D printed photocurable shape memory resin for clear aligners. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):1-10.

- Koenig N, Choi JY, McCray J, Hayes A, Schneider P, Kim KB. Comparison of dimensional accuracy between direct-printed and thermoformed aligners. The Korean Journal of Orthodontics. Published online 2022.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).