Submitted:

11 February 2024

Posted:

13 February 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

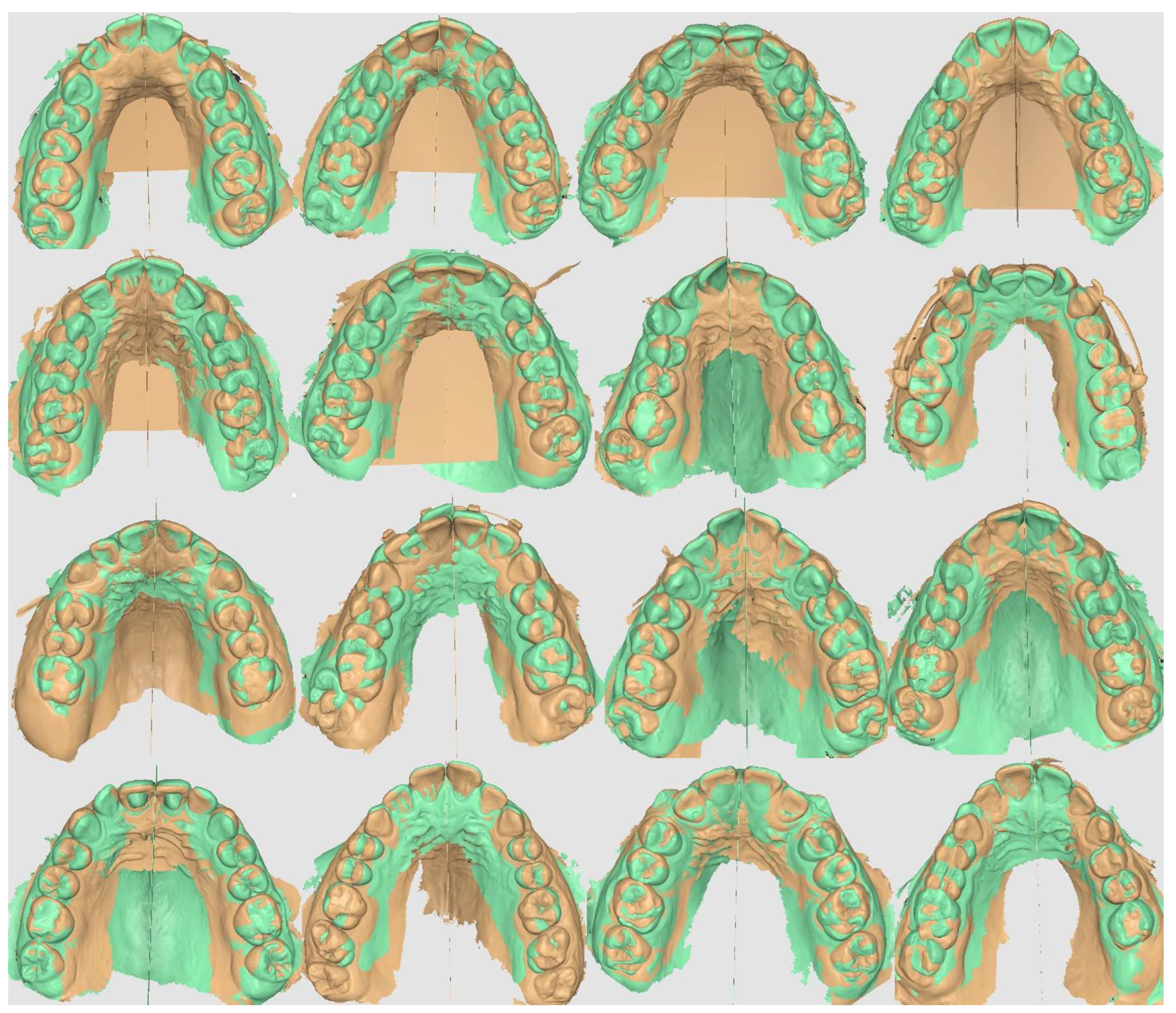

2. Materials and Methods

- Class II occlusion with no skeletal Class II values

- Skeletal cephalometric values of SNA = 81± 3º , SNB = 78 ± 3º , ANB = 3 ± 2º ;

- Patients were compliant with dental monitoring on a monthly basis;

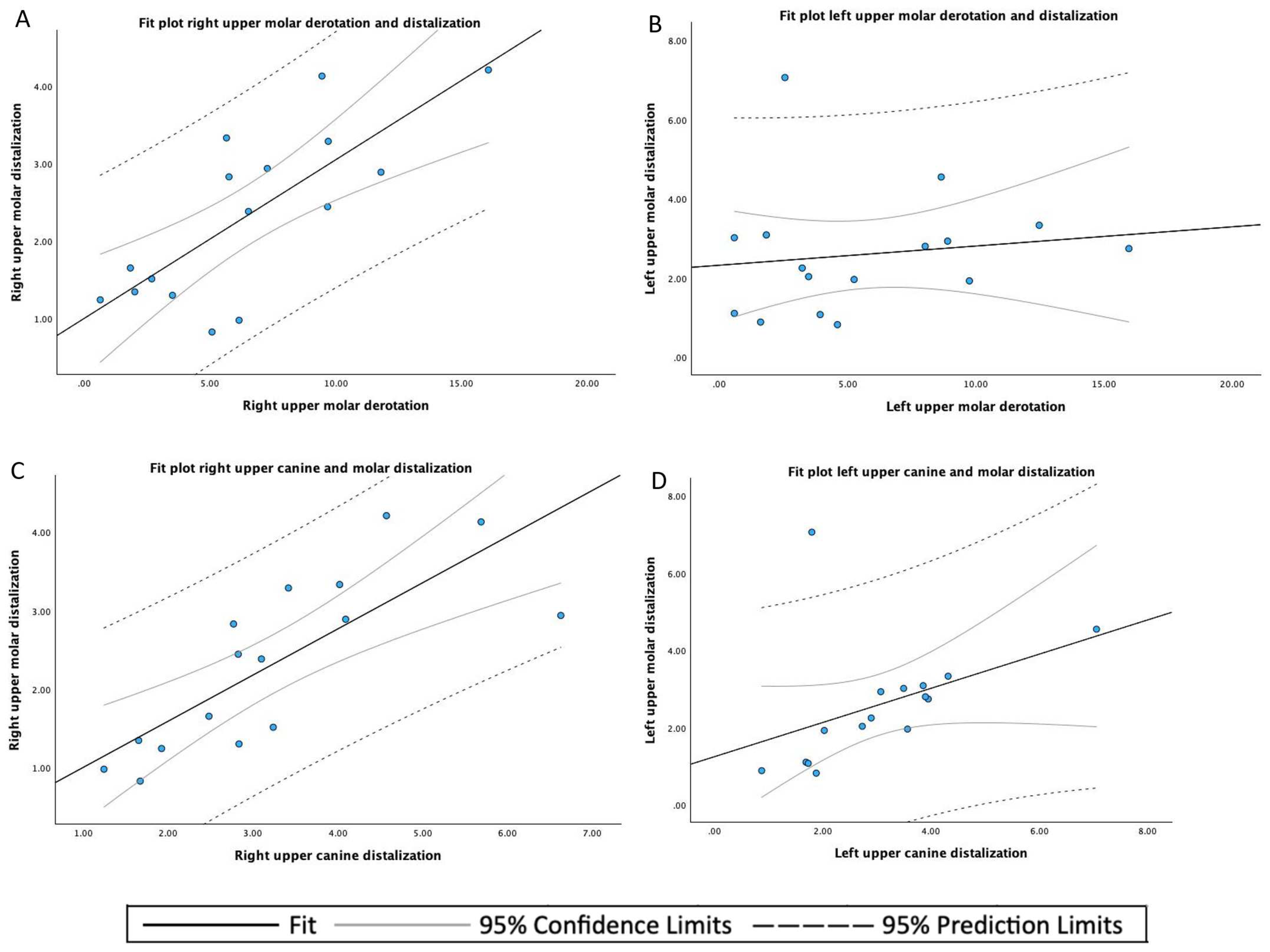

3. Results

| n | Mean | SD 1 | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper canine displacement | 32 | 3.157 | 1.453 | 0.88 | 7.06 |

| Upper molar displacement | 32 | 2.465 | 1.336 | 0.82 | 7.06 |

| Upper molar derotation angle | 32 | 6.098 | 4.250 | 0.58 | 16.08 |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| CMA | Carriere motion appliance |

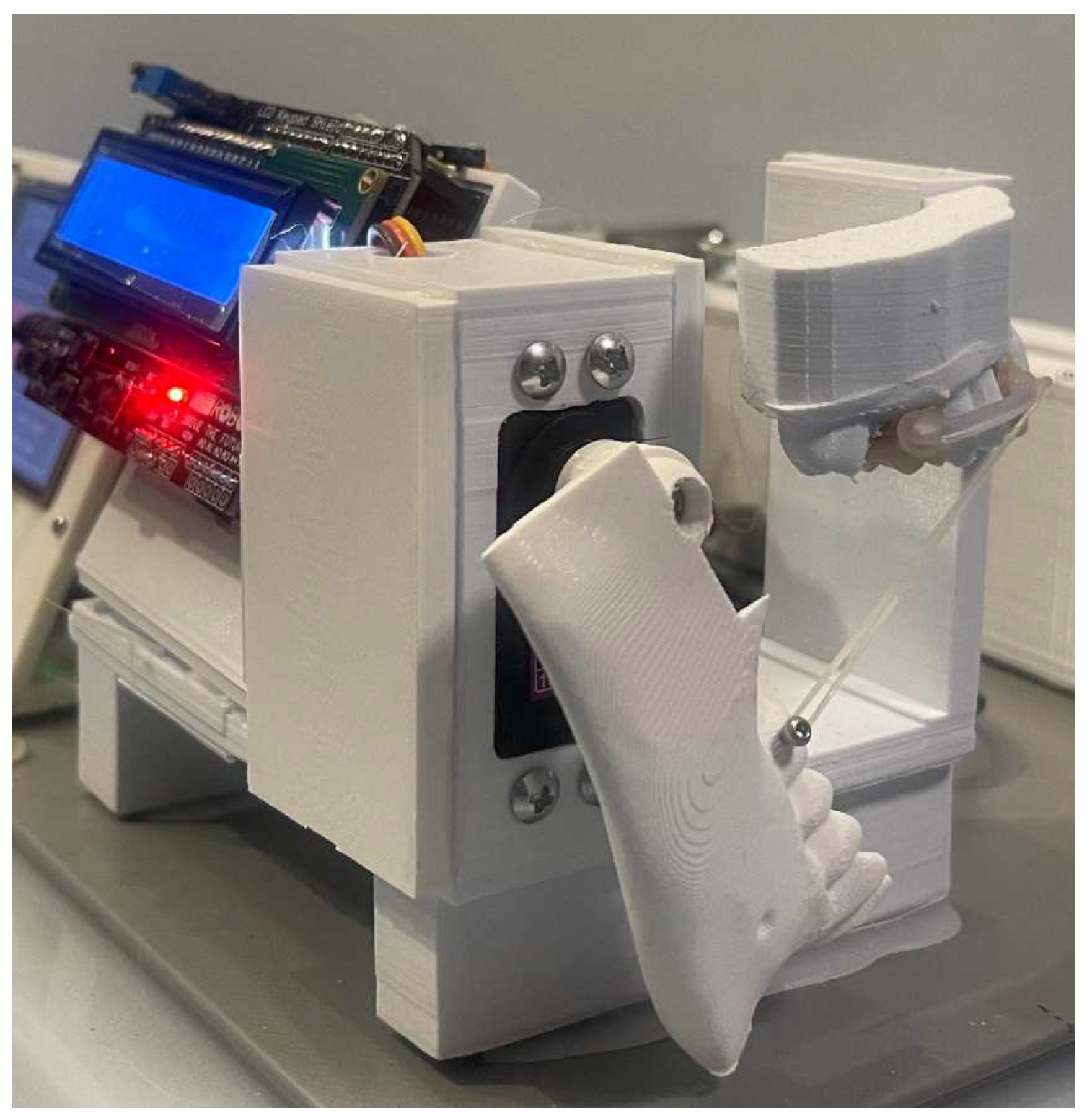

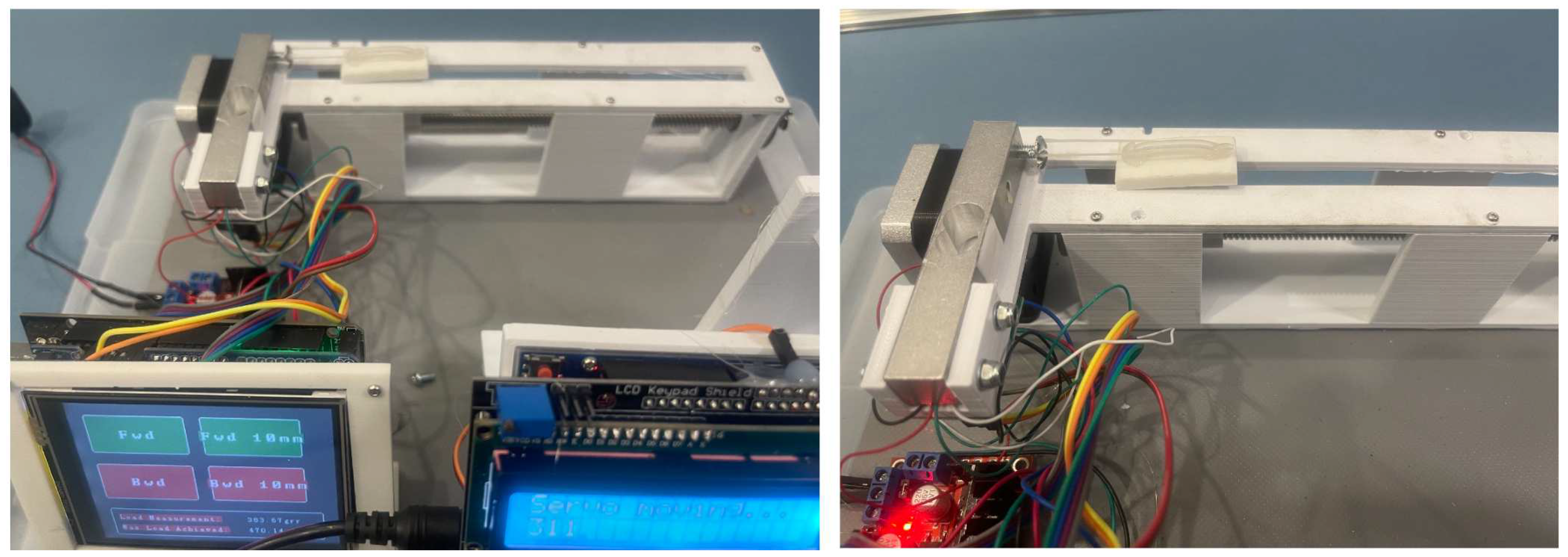

| AM | Additive Manufacturing |

| ICC | Intraclass Correlation Coefficients |

References

- Schmid-Herrmann, C.U.; Delfs, J.; Mahaini, L.; Schumacher, E.; Hirsch, C.; Koehne, T.; Kahl-Nieke, B. Retrospective investigation of the 3D effects of the Carriere Motion 3D appliance using model and cephalometric superimposition. Clin Oral Investig 2023, 27, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliades, T.; Zinelis, S. Three-dimensional printing and in-house appliance fabrication: Between innovation and stepping into the unknown. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2021, 159, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tartaglia, G.M.; Mapelli, A.; Maspero, C.; Santaniello, T.; Serafin, M.; Farronato, M.; Caprioglio, A. Direct 3D printing of clear orthodontic aligners: Current state and future possibilities. Materials 2021, 14, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Yan, B.; Jiang, M.; Xu, B.; Xu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Ma, T.; Wang, H. Enhanced Adhesion-Efficient Demolding Integration DLP 3D Printing Device. Applied sciences 2022, 12, 7373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradowska-Stolarz, A.; Malysa, A.; Mikulewicz, M. Comparison of the Compression and Tensile Modulus of Two Chosen Resins Used in Dentistry for 3D Printing. Materials 2022, 15, 8956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsolakis, I.A.; Papaioannou, W.; Papadopoulou, E.; Dalampira, M.; Tsolakis, A.I. Comparison in Terms of Accuracy between DLP and LCD Printing Technology for Dental Model Printing. Dentistry journal 2022, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, S.M.; Demoly, F.; Zhou, K.; Qi, H.J. Pixel-Level Grayscale Manipulation to Improve Accuracy in Digital Light Processing 3D Printing. Advanced functional materials 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradowska-Stolarz, A.; Wieckiewicz, M.; Kozakiewicz, M.; Jurczyszyn, K. Mechanical Properties, Fractal Dimension, and Texture Analysis of Selected 3D-Printed Resins Used in Dentistry That Underwent the Compression Test. Polymers 2023, 15, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revilla-León, M.; Cascos-Sánchez, R.; Zeitler, J.M.; Barmak, A.B.; Kois, J.C.; Gómez-Polo, M. Influence of print orientation and wet-dry storage time on the intaglio accuracy of additively manufactured occlusal devices. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vlasa, A.; Bocanet, V.I.; Muntean, M.H.; Bud, A.; Dragomir, B.R.; Rosu, S.N.; Lazar, L.; Bud, E. Accuracy of Three-Dimensional Printed Dental Models Based on Ethylene Di-Methacrylate-Stereolithography (SLA) vs. Digital Light Processing (DLP). Applied sciences 2023, 13, 2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcel, R.; Reinhard, H.; Andreas, K. Accuracy of CAD/CAM-fabricated bite splints: milling vs 3D printing. Clinical oral investigations 2020, 24, 4607–4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, S.; Neri, P.; Paoli, A.; Razionale, A.V.; Tamburrino, F. Development of a DLP 3D printer for orthodontic applications. Procedia Manufacturing 2019, 38, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Hu, P.; Wu, Z.; Liu, W.; Lv, Q.; Nie, Z.; Zhengdi, H. Comparison of accuracy and precision of various types of photo-curing printing technology. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 2020, 1549, 32151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, A.Z.; Galatanu, S.V.; Nagib, R. The Influence of Printing Layer Thickness and Orientation on the Mechanical Properties of DLP 3D-Printed Dental Resin. Polymers 2023, 15, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Turecek, C.; Mateos, A.; Stampfl, J.; Liska, R.; Varga, F. Evaluation of Biocompatible Photopolymers II: Further Reactive Diluents. Monatshefte fur Chemie 2007, 138, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alifui-Segbaya, F.; Varma, S.; Lieschke, G.; George, R. Biocompatibility of Photopolymers in 3D printing. Addit. Manuf. 2017, 4, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurzo, A.; Sufliarsky, B.; Urbanova, W.; Cverha, M.; Strunga, M.; Varga, I. Pierre Robin Sequence and 3D Printed Personalized Composite Appliances in Interdisciplinary Approach. Polymers 2022, 14, 3858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goracci, C.; Juloski, J.; D’Amico, C.; Balestra, D.; Volpe, A.; Juloski, J.; Vichi, A. Clinically Relevant Properties of 3D Printable Materials for Intraoral Use in Orthodontics: A Critical Review of the Literature. Materials 2023, 16, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yang, J.; Jia, Y.G.; Lu, B.; Ren, L. Study of a 3D-Printable Reinforced Composite Resin: PMMA Modified with Silver Nanoparticles Loaded Cellulose Nonocrystal. Materials 2018, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aretxabaleta, M.; Xepapadeas, A.B.; Poets, C.F.; Koos, B.; Spintzyk, S. Fracture load of an orthodontic appliance for robin sequence treatment in a digital workflow. Materials 2021, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurzo, A.; Urbanová, W.; Novák, B.; Waczulíková, I.; Varga, I. Utilization of a 3D Printed Orthodontic Distalizer for Tooth-Borne Hybrid Treatment in Class II Unilateral Malocclusions. Materials 2022, 15, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.; Chung, C.J.; Choi, Y.; Kim, S.J.; J-Y, C. Thermo-mechanical properties of 3D printed photocurable shape memory resin for clear aligners. Sci Rep 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou, S.; Polychronis, G.; Panayi, N.e.a. New aesthetic in-house 3D-printed brackets: proof of concept and fundamental mechanical properties. Prog Orthod. 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cenzato, N.; Nobili, A.; Maspero, C. Prevalence of Dental Malocclusions in Different Geographical Areas: Scoping Review. Dent J (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Q.V., N.; Bezemer, P.; Habets, L.; Prahl-Andersen, B. A systematic review of the relationship between overjet size and traumatic dental injuries. Eur J Orthod.. 1999, 21, 503–15. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanda, R.; Garino, F.; Ojima, K.; Castroflorio, T.; Parrini, S. Chapter 12: The hybrid approach in class II malocclusions treatment. In Principles and Biomechanics of Aligner Treatment- E-Book, 1st ed.; Vol. 1, Elsevier Health Sciences, 2021; pp. 149–160.

- Hilgers, J.J. The pendulum appliance for Class II non-compliance therapy. J Clin Orthod 1992, 26, 706–14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kinzinger, G.S.; Diedrich, P.R. Biomechanics of a Distal Jet appliance. Theoretical considerations and in vitro analysis of force systems. Angle Orthod 2008, 78, 676–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayinsu, K.; Isik, F.; Allaf, F.; Arun, T. Unilateral molar distalization with a modified slider. European journal of orthodontics 2006, 28, 361–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, A.; Sayinsu, K. A new approach in maxillary molar distalization: Intraoral bodily molar distalizer. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics 2000, 117, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, P.; Ragini, R. The J-Molar Distalizer for bodily molar movement. Journal of clinical orthodontics 2014, 48, 312–315. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield, R.L. The Greenfield lingual distalizer. Journal of clinical orthodontics 2005, 39, 548–56. [Google Scholar]

- Walde, K.C. The simplified molar distalizer. Journal of clinical orthodontics 2003, 37, 616–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, J.; Nanda, R.S. Evaluation of an intraoral maxillary molar distalization technique. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1996, 110, 639–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byloff, F.K.; Darendeliler, M.A.; Clar, E.; Darendeliler, A. Distal molar movement using the pendulum appliance. Part 2: The effects of maxillary molar root uprighting bends. Angle Orthod 1997, 67, 261–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarenbach, T.H.; Wilmes, B.; Ihssen, B.; Vasudavan, S.; Drescher, D. Hybrid hyrax distalizer and mentoplate for rapid palatal expansion, class III treatment, and upper molar distalization. Journal of clinical orthodontics 2017, 51, 317–325. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, S.; Vasudavan, S.; Wilmes, B. CAD/CAM Metallic Printing of a Skeletally Anchored Upper Molar Distalizer. Journal of clinical orthodontics 2020, 54, 140–150. [Google Scholar]

- Longerich, U.J.J.; Thurau, M.; Grill, F.; Stimmer, H.; Gahl, C.M.; Kolk, A. Does molar distalization by the Beneslider have skeletal and dental impacts? A prospective 3D analysis. Oral surgery, oral medicine, oral pathology and oral radiology 2022, 134, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longerich, U.J.J.M.D.D.D.S.; Thurau, M.M.D.D.D.S.; Kolk, A.M.D.D.D.S.P. Development of a new device for maxillary molar distalization with high pseudoelastic forces to overcome slider friction: the Longslider—a modification of the Beneslider. ORAL SURGERY ORAL MEDICINE ORAL PATHOLOGY ORAL RADIOLOGY 2014, 118, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrière, L. A new Class II distalizer. Journal of clinical orthodontics 2004, 38, 224–231. [Google Scholar]

- Luca, L.; Francesca, C.; Daniela, G.; Alfredo, S.G.; Giuseppe, S. Cephalometric analysis of dental and skeletal effects of Carriere Motion 3D appliance for Class II malocclusion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2022, 161, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nercellas Rodriguez, A.; Colino Gallardo, P.; Zubizarreta-Macho, A.; Colino Paniagua, C.; Alvarado Lorenzo, A.; Albaladejo Martinez, A. A New Digital Method to Quantify the Effects Produced by Carriere Motion Appliance. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, H.L. Long-Term Stability of Two-Phase Class II Treatment with the Carriere Motion Appliance. J Clin Orthod 2019, 53, 481–487. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, B.; Konstantoni, N.; Kim, K.B.; Foley, P.; Ueno, H. Three-dimensional cone-beam computed tomography comparison of shorty and standard Class II Carriere Motion appliance. Angle Orthod 2021, 91, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Areepong, D.; Kim, K.B.; Oliver, D.R.; Ueno, H. The Class II Carriere Motion appliance. Angle Orthod 2020, 90, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A.S.; Attia, K.H.; Abouelezz, A.M.; El-Ghafour, M.A.; Aboulfotouh, M.H. Anchorage control using miniscrews in comparison to Essix appliance in treatment of postpubertal patients with Class II malocclusion using Carriere Motion Appliance. Angle Orthod 2022, 92, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clermont, A.; Albert, A.; Bruwier, A. Effects of the Class II Carriere motion appliance in phase I treatment: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Orthod 2022, 56, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Areepong, D.; Kim, K.B.; Oliver, D.R.; Ueno, H. The Class II Carriere Motion appliance. Angle Orthod 2020, 90, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouda, A.S.; Aboulfotouh, M.H.; Attia, K.H.; Aboulezezz, A.M. Carriere Motion Appliance with Miniscrew Anchorage for Treatment of Class II, Division 1 Malocclusion. J Clin Orthod 2020, 54, 633–641. [Google Scholar]

- Barakat, D.; Bakdach, W.M.M.; Youssef, M. Treatment effects of Carriere Motion Appliance on patients with class II malocclusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Orthod 2021, 19, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, L.; Cremonini, F.; Oliverio, T.; Cervinara, F.; Siciliani, G. Class II correction with Carriere Motion 3D Appliance and clear aligner therapy. J Clin Orthod 2022, 56, 187–193. [Google Scholar]

- Attia, K.H.; Aboulfotouh, M.F.A. Three-dimensional computed tomography evaluation of airway changes after treatment with Carriere Motion 3D Class II appliance. J Dent Maxillofacial Res. 2019, 2, 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Malinowski, K.; Chodur, M.; Majewski, M.; Malinowski, J. Age dependent treatment response to the Carriere Motion 3D appliance for the correction of Class II malocclusion. Journal of Education, Health and Sport 2022, 12, 169–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, A.S. Thre dimensional assessment of the long-term treatment stability after maxillary first molar distalisation with Carriere distalizer appliance. Life Sci J 2020, 17, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Nasef, A.; Refai, W. Application of a New Three Dimensional Method of Analysis for Comparison between the Effects of Two Different Methods of Distalisation of the Maxillary First Molar. Egypt Dent J 2015, 61, 4195–4201. [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Berman, H.; McNamara, J.A..J.; JP, L.; McMullen, C.; Franchi, L. Treatment effects of the Carriere Motion 3D appliance for the correction of Class II maloccludion in adolescents. Angle Orthod. 2019, 89, 839–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghozy, E.A.; Albelasy, N.F.; Shamaa, M.S.; El-Bialy, A.A. Cephalometric and digital model analysis of Dentoskeletal effects of Infrazygomatic miniscrew vs. Essix- anchored Carriere Motion appliance for distalization of maxillary buccal segment: A randomized clinical trial. BMC Oral Health. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, K.; Han, E.; Guo, J.; Yasumura, T.; Grauer, D.; Sameshima, G. Evaluating the treatment effectiveness and efficiency of Carriere Distalizer: a cephalometric and study model comparison of Class II appliances. Prog Orthod 2019, 20, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Xie, D.; Liu, F.; Zhao, J.; Shen, L.; Tian, Z. DLP-Based 3D Printing for Automated Precision Manufacturing. Mobile information systems 2022, 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- liqcreate. Explained & tested: Anti-Aliasing (AA) and Blur in resin 3D-printing, 2023.

- Federici Canova, F.; Oliva, G.; Beretta, M.; Dalessandri, D. Digital (R)Evolution: Open-Source Softwares for Orthodontics. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formlabs Form 3B+ printer. https://media.formlabs.com/m/759db40c7c05b049/original/-ENUS-Form-3B-manual.pdf.

- Sarker, S.; Colton, A.; Wen, Z.; Xu, X.; Erdi, M.; Jones, A.; Kofinas, P.; Tubaldi, E.; Walczak, P.; Janowski, M.; et al. 3D-Printed Microinjection Needle Arrays via a Hybrid DLP-Direct Laser Writing Strategy. Advanced materials technologies 2023, 8, n. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Form Wash Manual. https://media.formlabs.com/m/11c8523a56138d6/original/-ENUS-Form-Wash-Manual.pdf.

- Form Cure Time and Temperature Settings. https://s3.amazonaws.com/servicecloudassets.formlabs.com/med ia/Finishing/Post-Curing/115001414464-Formettings.pdf.

- Espinar-Escalona, E.; Barrera-Mora, J.M.; Llamas-Carreras, J.M.; Solano-Reina, E.; Rodriguez, D.; Gil, F.J. Improvement in adhesion of the brackets to the tooth by sandblasting treatment. J Mater Sci Mater Med 2012, 23, 605–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scribante, A.; Gallo, S.; Turcato, B.; Trovati, F.; Gandini, P.; Sfondrini, M.F. Fear of the Relapse: Effect of Composite Type on Adhesion Efficacy of Upper and Lower Orthodontic Fixed Retainers: In Vitro Investigation and Randomized Clinical Trial. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Kara, M.; Seker, E.; Yenidunya, D. Do we know how much force we apply with latex intermaxillary elastics? Apos Trends in Orthodontics 2021, 11, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castroflorio, T.; Sedran, A.; Spadaro, F.; Rossini, G.; Cugliari, G.; Quinzi, V.; Deregibus, A. Analysis of Class II Intermaxillary Elastics Applied Forces: An in-vitro Study. Frontiers in Dental Medicine 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saccomanno, S.; Quinzi, V.; Paskay, L.; Caccone, L.; Rasicci, L.; Fani, E.; Di Giandomenico, D.; Marzo, G. Evaluation of the Loss of Strength, Resistance, and Elasticity in th Different Types of Intraoral Orthodontic Elastics (IOE): A Systematic Review of the Literature of In Vitro Studies. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubovska, I.; Lickova, B.; Voborna, I.; Urbanova, W.; Kotova, M. Force of Intermaxillary Latex Elastics from Different Suppliers: A Comparative In Vitro Study. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medit Link Software. https://www.meditlink.com/home.

- Stefanelli, L.; Franchina, A.; Pranno, A.; Pellegrino, G.; Ferri, A.; Pranno, N.; Di Carlo, S.; De Angelis, F. Use of Intraoral Scanners for Full Dental Arches; Could Different Strategies or Overlapping Software Affect Accuracy. Int. Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2021, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurzo, A.; Kociš, F.; Novák, B.; Czako, L.; Varga, I. Three-Dimensional Modeling and 3D Printing of Biocompatible Orthodontic Power-Arm Design with Clinical Application. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, D. The Carriere Distalizer: simple and efficient. Int J Orthod Milwaukee 2012, 23, 63–6. [Google Scholar]

| ID | Age in Decimals | Time Worn | Size Right | Size Left | Failure | Failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | [years] | [weeks] | [mm] | [mm] | # | # |

| 1 | 14.95 | 16.71 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 14.95 | 16.71 | 25 | 25 | 1 | 0 |

| 3 | 12.62 | 11.57 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 15.41 | 17.71 | 26 | 27 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | 11.74 | 17.57 | 26 | 26 | 0 | 1 |

| 6 | 14.28 | 9.14 | 24 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 17.91 | 13.57 | 24 | 24 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 49.34 | 14.00 | 26 | 26 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | 12.94 | 11.29 | 19 | 19 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | 14.92 | 17.14 | 27 | 27 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | 14.11 | 10.00 | 26 | 26 | 0 | 1 |

| 12 | 11.89 | 24.86 | 26 | 26 | 1 | 0 |

| 13 | 15.41 | 10.29 | 25 | 25 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | 14.06 | 19.57 | 24 | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 13.07 | 9.86 | 18 | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | 15.34 | 13.29 | 24 | 24 | 0 | 1 |

| Variable | Statistics or Category | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Age [years] | mean ± SD 1 | 16.43 ± 8.91 |

| median (range) | 14.60 (11.74 - 49.34) | |

| Size [mm] | median (range) | 25.00 (18.00 - 27.00) |

| Time worn [weeks] | mean ± SD | 14.58 ± 4.31 |

| median (range) | 13.79 (9.14 - 24.86) | |

| Total failures 2 | mean | 0.94 |

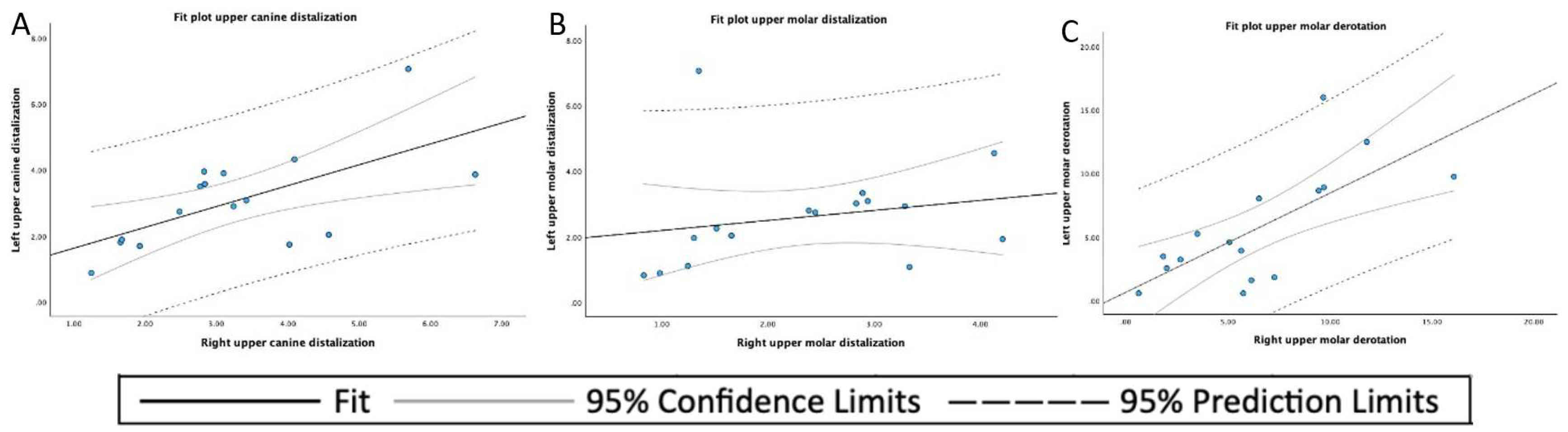

| Mean | SD 1 | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left upper canine displacement | 3.054 | 1.476 | 0.88 | 7.06 |

| Right upper canine displacement | 3.620 | 1.471 | 1.24 | 6.63 |

| Left upper molar displacement | 2.597 | 1.565 | 0.82 | 7.06 |

| Right upper molar displacement | 2.333 | 1.097 | 0.83 | 4.21 |

| Left upper molar derotation angle | 5.711 | 4.488 | 0.58 | 15.98 |

| Right upper molar derotation angle | 6.484 | 4.108 | 0.63 | 16.08 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).