1. Introduction

Territorial Management Instruments (TMIs) are central to operationalizing public policies related to land use. In Portugal, the evolution of TMIs reflects broader shifts in planning philosophy (from hierarchical control to networked governance, from legal formalism to procedural streamlining, and from passive public consultation to ambitions of active civic participation). Yet, these transitions have produced new contradictions because institutional simplification has not always resulted in effectiveness, and increased participation has sometimes slowed or fragmented implementation.

This article focuses on two pivotal legal milestones - Decree-Law No. 380/1999 and Decree-Law No. 80/2015 - as entry points to explore how governance architecture, participatory design, and regulatory complexity interact in practice. The 1999 framework, grounded in Law No. 48/98, emphasized vertical integration and legal transparency, creating a coordinated yet procedurally dense planning regime. The 2015 reform, emerging from Law No. 31/2014, sought to modernize this landscape by introducing digital tools, redefining strategic-operational distinctions, and compressing public consultation timelines.

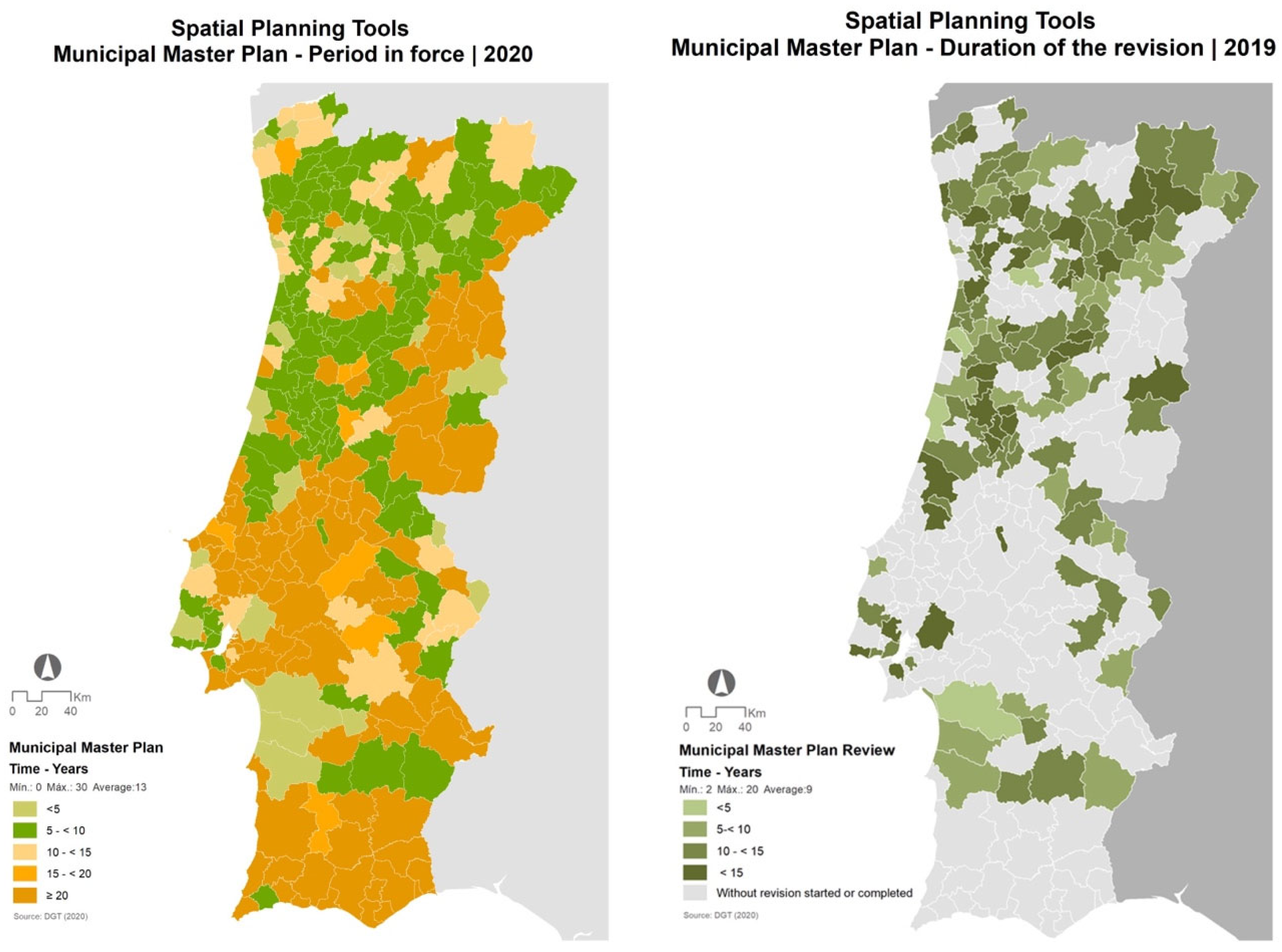

Although the two frameworks aimed to address different challenges, both struggled to strike a balance between efficiency and democratic legitimacy. In practice, planning processes often continue to be slow (see

Figure 1), conflict-laden, and susceptible to administrative inertia. While participation is required by law, it frequently swings between being merely symbolic and overwhelming in complexity, raising important concerns about whether it can truly drive meaningful change.

To deepen this analysis, the article introduces the concept of temporal governance as the idea that planning time is not a neutral backdrop but a strategic variable that shapes institutional adaptability. By considering this perspective, we move beyond binary debates (fast vs. slow; inclusive vs. efficient) and toward a more nuanced understanding of governance under complexity.

Thus, this article investigates how the institutional framework has changed over time and what these shifts reveal about the dynamics of governance in spatial planning. A central concern of the research is the impact of institutional complexity on the efficiency and legitimacy of planning processes. Specifically, it examines whether intricate institutional arrangements slow down planning procedures and how they influence perceptions of procedural fairness and transparency. The study also delves into the role of public participation in territorial planning. It considers how citizen involvement shapes both the quality of planning outcomes and the overall efficiency of decision-making processes. Finally, the article proposes a critical reframing of procedural delays. Rather than viewing them solely as obstacles, it explores whether these delays can be seen as opportunities to better integrate environmental considerations into the planning process, potentially leading to more sustainable and just outcomes.

By answering these questions through legal analysis, documentary review, and theoretical synthesis, the article contributes for the ongoing heated debates on adaptive governance, procedural design, and the strategic role of time in planning.

2. Consequences of Delays in Spatial Planning Beyond Bureaucratic Inefficiencies

2.1. Spatial Planning Governance and Institutional Complexity

Governance in spatial planning has undergone a profound transformation in response to increasingly complex challenges. Traditionally characterized by a top-down, hierarchical structure dominated by state actors, planning systems in Europe have gradually evolved toward more polycentric, participatory, and adaptive forms of governance (Swyngedouw, 2005; Albrechts, 2012). This paradigmatic shift reflects broader societal trends as decentralization and digitalization, that redefine how territorial strategies are conceptualized and implemented.

In Portugal, this evolution is evident in the legal and institutional reforms introduced through the spatial planning framework Laws of 1999 and 2015. These reforms marked a departure from rigid planning hierarchies and introduced mechanisms for horizontal coordination, more stakeholder engagement, and better spatial integration across governance levels (Teles, 2016). The 2015 reform, in particular, emphasized simplification and procedural streamlining, aligning with EU directives on subsidiarity and the more recent digital governance agenda (OECD, 2020). While the move toward digital platforms and decentralized decision-making enhances local responsiveness and administrative efficiency, it also introduces new risks, such as uneven institutional capacity and increased coordination complexity (Allmendinger & Haughton, 2010). Empirical studies, such as Grave & Pereira (2016), identified more than 20 formal steps in some MPSP (municipal plans for spatial planning) review processes, many of which do not add substantive value but are mandatory due to excessive regulations or legal interpretation.

Crucially, as Healey (2006) and Innes & Booher (2010) argue, governance in complex planning environments cannot rely solely on institutional design or legal instruments. Instead, it demands relational and adaptive capacities as the ability to co-produce knowledge, manage interdependencies, and respond to emergent spatial dynamics in real time. This view aligns with resilience thinking in planning, where uncertainty and contested values require continuous negotiation and learning among diverse actors (Davoudi, 2012).

The Portuguese experience illustrates this tension vividly. Despite efforts to modernize and rationalize planning, the practical implementation often reveals persistent challenges as fragmented stakeholder engagement, jurisdictional overlaps, and conflicts between efficiency-oriented planning and the need for legitimacy, inclusiveness, and place-based nuance (Medeiros, 2021). In some cases, the emphasis on procedural efficiency and digital governance may inadvertently marginalize less technologically equipped municipalities or actors with lower institutional capital, reinforcing spatial and social inequalities.

Thus, governance in spatial planning must be seen not merely as a set of institutional arrangements, but as an ongoing, context-sensitive process shaped by power relations, and evolving socio-environmental conditions. The Portuguese case provides a valuable lens through which to examine the promises and pitfalls of governance reform in the face of complex territorial challenges.

2.2. Participatory Planning: Promise and Pitfalls

Participatory planning has emerged as a normative ideal in contemporary spatial governance, grounded in the principles of deliberative democracy. Rooted in Arnstein’s (1969) “Ladder of Citizen Participation” and Forester’s (1999) emphasis on communicative ethics, the paradigm seeks not merely to inform citizens but to empower them as co-creators in the planning process. This shift is driven by both democratic imperatives, enhancing legitimacy, transparency, and trust, and pragmatic considerations, such as harnessing local knowledge and fostering place-based solutions (Healey, 1997; Innes & Booher, 2004).

Portugal’s planning reforms reflect these global trends. The 1999 legal framework represented a significant institutional commitment to participatory democracy, introducing extended public consultation periods of 60 days, mandatory public exhibitions, and in-person deliberative events. Participation was thus embedded not only as a procedural step but as a legal right, institutionalizing the citizen’s role in shaping territorial futures (Silva, 2020). However, this model also revealed structural challenges as low engagement rates, excessive procedural formalism, and strong limitations in inclusivity, especially in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas (Teles, 2016).

The 2015 reform marked a paradigmatic turn toward digitalization and procedural efficiency. Consultation periods were halved to 30 days, and platforms for online participation became the primary interface between planners and citizens. While this transition improved accessibility in urban and digitally literate contexts - enabling asynchronous participation, broader outreach, and real-time feedback - it also accentuated structural inequalities. Many non-urban or metropolitan municipalities lacked the necessary digital infrastructure or civic digital literacy, leading to uneven participation geographies and reinforcing existing power asymmetries (Hernández-Partal, 2020; OECD, 2020).

Empirical research underscores a key paradox: efforts to streamline participation for efficiency often risk reducing its depth, and transformative potential. Shortened timelines can disproportionately exclude marginalized or time-poor groups, turning participation into a symbolic exercise rather than a substantive deliberation (Quick & Bryson, 2016). In such cases, public input may be acknowledged procedurally but sidelined substantively, resulting in what Fung (2015) terms “participation without redistribution”.

However, when participatory processes are carefully structured (with sufficient timeframes, inclusive facilitation, and meaningful feedback loops) they can significantly enhance planning outcomes. They contribute to empower communities, and improve the legitimacy and resilience of planning decisions (Shipley & Utz, 2012). Participatory governance thus functions best not as an isolated step, but as a continuous, dialogical process integrated across planning cycles.

Portugal’s mixed experience reveals that participation is not inherently empowering; its effectiveness hinges on how, for whom, and under what conditions it is operationalized. The challenge is to balance efficiency with inclusivity, ensuring that, for instance, digital innovations do not compromise the democratic ethos at the heart of participatory planning.

Modern spatial planning operates within an increasingly intricate regulatory landscape, where multiple legal instruments, institutional layers, and policy frameworks converge. This regulatory complexity is especially pronounced in systems like Portugal’s, where EU directives, national legislation, regional frameworks, and municipal plans intersect, often with overlapping mandates and competing temporalities (Allmendinger & Haughton, 2012; Teles, 2016). While such density is frequently critiqued as bureaucratic overreach, it may also signal deliberate efforts to reconcile normative goals - economic development, environmental protection, and social equity - within a pluralistic governance framework (Sager, 2009).

It often happens that public bodies, such as municipalities, end up eschewing territorial planning instruments, opting for other ways of transforming urban territories that are more invisible and have far fewer formal requirements for public participation. However, it also happens that what was designed to be quicker and faster ends up taking longer because of popular protest (Gonçalves, 2022; Gonçalves et al., 2025).

From this perspective, regulatory complexity is not intrinsically dysfunctional. Rather, it reflects the normative ambition of planning to mediate conflicting interests and value systems. However, when coordination mechanisms are weak or absent, this multiplicity can devolve into institutional inertia, and in a paradox administrative opacity (Clifford et al., 2013). In the Portuguese context, successive reforms have introduced new legal tiers - such as sectoral plans, inter-municipal strategies, and integrated territorial investments - without always ensuring coherence or clarity in their implementation (Silva & Syrett, 2006). The result is a planning environment that, while comprehensive, often suffers from procedural overload and conflicting statutory obligations.

Importantly, planning delays, typically framed as inefficiencies or symptoms of dysfunction, can also serve as strategic instruments. Scholars like Broitman (2020) and Enoguanbhor et al. (2019) argue that temporal flexibility allows for adaptive learning, and more inclusive stakeholder engagement. Delays can be especially valuable in contexts involving Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEA), where comprehensive cumulative impact analyses, and public consultations require extended timelines to ensure more robustness and transparency (Therivel, 2010).

In Portugal, SEA-linked delays have, in several cases, been utilized not as bureaucratic stalling but as opportunities to embed ecological intelligence into planning. For example, environmental objections raised during SEA processes have led to the reconsideration of infrastructure alignments, redesign of urban development areas, or incorporation of ecosystem services into zoning decisions (Medeiros, 2021). These delays, while politically contentious, reflect a more deliberative and precautionary approach to territorial transformation.

However, the ambivalence of delay must be acknowledged. Poorly managed or politically motivated delays can impose significant costs because they discourage private investment, and reduce the credibility of planning institutions (Ball, 2010; Lai et al., 2016). Moreover, in competitive urban and regional markets, prolonged uncertainty can exacerbate land speculation, drive up development costs, and create disincentives for long-term planning. The challenge lies in distinguishing constructive delay, which enhances planning quality, from dysfunctional delay, which merely signals governance breakdown.

In sum, regulatory complexity and temporal slowness are not inherently pathological features of spatial planning. When designed and governed with intent, they can be tools for accountability, and sustainability. Yet, without institutional capacity, inter-agency coordination, and political will, they risk becoming obstacles rather than enablers of effective territorial governance.

2.3. Consequences of Planning Delays: Evidences from Portugal

2.3.1. Empirical Evidence from Almada’s PDM Revision as a Typology of Planning Delays

The revision of Almada’s Municipal Master Plan (PDM), a municipal territory in Lisbon Metropolitan Area, provides a compelling empirical window into the complex temporalities of spatial planning in Portugal. Officially initiated in December 2008, nearly a decade after the original 1997 plan, the process remained incomplete more than seventeen years later. Rather than a linear progression, Almada’s revision unfolded in phases marked by distinct types of delay, which exemplify the analytical categories proposed in this article’s temporal governance framework.

- i.

Procedural delays (2009–2011)

The early stages of the revision, marked by the establishment of a Monitoring Commission (CA), initiation of public participation under the RJIGT framework, and development of baseline territorial characterization studies, reflected legally induced procedural delay. These steps, although time-consuming, were largely driven by compliance requirements and environmental assessment obligations. The need to align with statutory norms, conduct SEA scoping, and engage with multiple state actors resulted in predictable but extended timelines.

- ii.

Negotiated delays (2012–2015, 2022-2025)

Between 2012 and 2015, the process entered in a more deliberative phase, characterized by targeted engagement with local stakeholders, such as parish councils, civic groups, and thematic actors in education, culture, and economy. Events like the Congress "Almada: Thinking about the future " (2015), involving 11 thematic sessions across the municipality, reflected a conscious extension of planning time to incorporate divergent perspectives and co-produce a shared vision. This period exemplifies a negotiated delay, in which time was used as a resource to enhance legitimacy and collective learning. The second period (2022-2025) has been marked by intense negotiation with entities with institutional and technical influence in the territory to reach a consensus on the final document, so that it is truly a Master Plan co-created by all those involved in the development of the municipality of Almada.

- iii.

Strategic delays (2016–2017)

Following the participatory cycle, the revision team leveraged the outcomes of the Congress to update key analytical outputs: projections to 2031, urban centrality maps, the delimitation of consolidated urban areas, and the integration of new legal frameworks (e.g., Law on Soils, Land Use, and Urbanism). These activities constituted strategic delays as intentional extensions of planning time to incorporate new knowledge, ecological criteria, and evolving institutional requirements. Although technically productive, they required calibration against shifting legal and political conditions.

- iv.

Pathological delays (2018–2021)

Despite progress, from 2018 onwards the process exhibited features of pathological delay. The transition from the Monitoring Commission to the new Consultative Commission in 2019, combined with institutional turnover, political ambiguity, and disruptions linked to the COVID-19 pandemic, led to a loss of momentum. The overlapping of planning cycles, lack of a clear timeline for approval, and administrative silos across agencies contributed to a phase marked by institutional drift, with limited visible output and diminishing public engagement.

The protracted timeline of Almada’s PDM revision, spanning over 17 years, should not be viewed as an isolated anomaly but rather as symptomatic of a broader national pattern. A comprehensive study by Grave & Pereira (2016), based on multiple municipal planning processes across Portugal, found that the average duration for revising Municipal Master Plans (PMOTs) ranged between 7 and 10 years, with several cases extending well beyond that threshold. These delays often occurred despite the existence of legal deadlines and procedural streamlining efforts. The Almada case, with its multiple phases of procedural, negotiated, and strategic delays, thus mirrors the systemic issues highlighted in the national data, particularly the accumulation of shifting institutional responsibilities, and recurring interruptions linked to legal and political cycles. As such, Almada should be understood not as an exception, but as a microcosm of structural inefficiencies that continue to affect spatial planning processes throughout Portugal.

2.3.2. Credibility and Legitimacy Loss

One of the most critical and recurring consequences of planning delays in Portugal has been the erosion of public trust in planning institutions. The 2015 reform's reduction of participation timelines, from 60 to 30 days, along with digitalization, often translated into superficial consultation practices, especially in municipalities with limited digital capacity (Hernández-Partal, 2020). This shift contributed to a perception of tokenism, where citizen input was seen as a procedural obligation rather than a substantive dialogue. As Fung (2015) notes, participatory mechanisms that lack transparency and feedback loops tend to degrade institutional legitimacy and reinforce civic disengagement over time.

2.3.3. Outdated Planning Instruments

The long approval cycles inherent in both the 1999 and 2015 planning systems have consistently resulted in the production of plans that are obsolete by the time they are ratified or implemented. This misalignment between planning horizons and decision-making cycles undermines the ability of spatial plans to remain adaptive and responsive to emerging socio-economic or environmental conditions (Allmendinger & Haughton, 2012). In a rapidly changing context marked by urban sprawl, climate change, and all kind of transitions (digital, energy, demographic, …), static plans produced through lengthy processes fail to provide actionable strategic guidance, thereby diminishing planning's anticipatory function (Healey, 2009).

2.3.4. Economic Costs and Investment Deterrents

Prolonged uncertainty caused by regulatory or procedural delays generates significant economic opportunity costs. In both pre- and post-2015 frameworks, investors and developers frequently reported challenges in navigating unpredictable approval timelines, and unclear responsibilities (Ball, 2010; Lai et al., 2016). These conditions not only deter capital inflow but also increase the transaction costs of land development, slowing down project implementation and reducing the competitiveness of local and regional economies. Additionally, uncertainty can provoke land speculation and inflated prices, further distorting spatial development outcomes (Needham, 2007).

Another source of delay in Portuguese spatial planning stems from judicialization and legal ambiguity, which often prompt public authorities to adopt overly cautious, risk-averse behaviors. As Grave & Pereira (2016) observe, the fear of litigation, exacerbated by the complex and sometimes contradictory legal framework, frequently leads to administrative paralysis, where planning actors delay decisions or engage in repetitive consultations to avoid future legal challenges. This results in planning timelines being extended not due to technical complexity, but due to a perceived need for legal defensibility. Municipalities, uncertain about how courts might interpret vague or evolving legislation, tend to overcompensate with procedural formalism and redundant documentation. The cumulative effect is a planning environment where legal risk management eclipses strategic territorial vision, imposing indirect economic costs through project stagnation, uncertainty, and diminished investor confidence.

2.3.5. Environmental Trade-Offs and Gains

Conversely, one positive externality of strategic delays, particularly those linked to Strategic Environmental Assessments (SEA), has been the deeper integration of ecological concerns into planning decisions. SEA processes often necessitate comprehensive environmental evaluations, stakeholder consultations, and inter-sectoral alignment, which naturally extend planning timelines (Therivel, 2010). In Portugal, several municipalities used these delays to re-evaluate project boundaries, integrate green infrastructure, and apply the precautionary principle more rigorously (Broitman, 2020; Enoguanbhor et al., 2019). In this context, slowness is not inefficiency but a form of temporal reflexivity that promotes long-term ecological resilience.

2.3.6. Governance Fragmentation and Bottlenecks

The cumulative impact of delay-prone planning has been a fragmentation of governance structures, especially following the 2015 reforms. The introduction of new layers (such as inter-municipal plans and digitized procedures) was not always accompanied by clear role delineation or institutional coordination mechanisms. As Swyngedouw (2005) and Brenner (2004) argue, fragmented governance landscapes often produce institutional bottlenecks, where overlapping competences and unclear mandates inhibit effective policy delivery. In Portugal, this fragmentation has at times reduced actor diversity, limited horizontal coordination, and intensified administrative silos, ultimately constraining innovation and responsiveness in territorial management.

2.3.7. Bypassing Formal Planning: Informality as a Response to Delay

One of the most significant yet under-acknowledged consequences of persistent delays in formal spatial planning is the gradual proliferation of informal or semi-formal planning practices. Faced with lengthy and unpredictable MPSP revision cycles, some municipalities have increasingly opted to bypass the rigid formal instruments, resorting instead to more flexible, project-based urban interventions. These often include isolated urban operations, ad hoc land-use adjustments, or planning exceptions justified on the basis of “public interest” or “strategic opportunity.”

This phenomenon, identified in several empirical studies (e.g., Grave & Pereira, 2016), reflects a pragmatic response to institutional inertia and legal complexity. In contexts where formal plans are outdated, misaligned with contemporary needs, or entangled in prolonged approval procedures, local authorities feel compelled to act outside, or around, the statutory frameworks. While such actions may address immediate development pressures or investment opportunities, they often weaken the coordinating and regulatory function of the planning system as a whole.

Moreover, the increasing reliance on these parallel mechanisms raises serious concerns about transparency, and democratic oversight. These discretionary practices tend to concentrate decision-making power within a narrow circle of political and technical elites, reducing opportunities for public scrutiny and participation, potentially provoking civic backlash (Gonçalves, 2022). Over time, this can contribute to a dual-track planning culture (Gonçalves, Freitas & Arnaut, 2025) where formal instruments are symbolically maintained but substantively sidelined.

For example, in Lisbon’s Sant’Ana Hill urban regeneration process, municipal authorities bypassed formal plan revisions and instead relied on exceptional planning mechanisms and urban rehabilitation operations. These actions, while legally justifiable under discretionary clauses, were not accompanied by robust participatory processes or transparent public debate. The result was significant civil society mobilization and contestation, highlighting the risks of planning informality in contested urban contexts (Gonçalves, Freitas & Arnaut, 2025).

Paradoxically, the very rigidity of formal planning, intended to guarantee legality and transparency, may be accelerating the drift toward informality. The more burdensome and time-consuming the formal procedures become, the greater the incentives to bypass them. This logic undermines the strategic role of spatial planning as a platform for collective visioning and long-term coordination, and risks turning it into an administrative formality detached from actual territorial transformation.

Therefore, delays should not only be analyzed in terms of their direct temporal impact, but also in terms of the institutional behaviors and planning cultures they generate. Bypassing formal planning is a symptom of deeper structural dysfunctions in the Portuguese planning system, and highlights the urgent need for reforms that balance legal robustness with procedural agility, and strategic foresight with operational responsiveness.

2.4. Rethinking Time in Planning

Conventional planning paradigms often treat time as an external constraint, something to be minimized in favor of efficiency, predictability, and delivery. However, this perspective overlooks the qualitative dimensions of time in governance. Drawing from recent shifts in planning theory and temporal political economy, we propose re-conceptualizing time not merely as a cost or burden but as a strategic and structuring resource. When time is managed with intent and aligned with broader governance goals, it can enhance the legitimacy, and adaptability of planning outcomes (Olesen, 2014; Davoudi, 2012).

This rethinking starts with a distinction between pathological delays and productive delays. Pathological delays arise from bureaucratic inertia, institutional fragmentation, or adversarial conflict. They reflect systemic dysfunctions that hinder responsiveness and erode trust in public institutions. By contrast, productive delays represent deliberate temporal stretches used to allow for environmental due diligence, inclusive deliberation, and conflict mediation. Such delays are not inefficiencies but investments in planning quality, akin to temporal buffers that safeguard public interest and long-term resilience (Broitman, 2020; Rydin, 2011).

The recognition of time as a resource also opens up a richer conversation around temporal justice. Different actors and communities experience time differently because what is a delay for a developer may be a window of negotiation for marginalized groups. Similarly, intergenerational equity (central to sustainability) requires planners to account for future temporalities, ensuring decisions today do not compromise ecological or social viability tomorrow (Davoudi, 2012). Thus, time becomes not just an operational factor but a political and ethical dimension of planning.

In the Portuguese context, this reconceptualization invites planners to move beyond binary views of fast versus slow planning. Instead, it calls for temporal calibration - designing planning processes with differentiated timeframes based on complexity, stakeholder diversity, and risk profiles. For instance, routine urban interventions may benefit from accelerated timelines, whereas large-scale strategic projects (particularly those with environmental or cultural sensitivities) require slower, deliberative pathways.

Operationalizing this perspective entails building institutional capacities for temporal reflexivity - the ability to adapt, and strategically use time within planning cycles. It also requires reforming legal and procedural norms that treat time rigidly, and instead promoting flexible, context-sensitive temporalities grounded in principles of equity, sustainability, and democratic participation.

2.5. A Framework for Temporal Governance in Spatial Planning

To move beyond binary discussions of delay as either dysfunction or virtue, we propose a conceptual framework that repositions time as a governable dimension of planning. This framework integrates the following interrelated components: (1) typologies of planning time, (2) delay differentiation, (3) temporal calibration, and (4) temporal justice. It aims to support planners and policymakers in designing more context-sensitive, and strategically timed planning processes.

This framework reframes time as a governance variable, not merely an operational constraint. It integrates insights from planning theory, systems thinking, and institutional design to support context-sensitive temporal strategies. The model is structured across four interrelated dimensions:

- i.

Typology of planning time.

| Type of Time |

Description |

Purpose |

| Chronological Time |

Measured by clock/calendar (e.g., 30-day consultations) |

Ensures predictability and legal compliance |

| Political Time |

Influenced by electoral cycles, administrative mandates, and strategic political considerations (e.g., conflict avoidance, negotiation with key actors). |

Shapes windows of opportunity; can delay or accelerate planning for political gain or risk management. |

| Deliberative Time |

Time required for meaningful participation and negotiation |

Builds legitimacy and social resilience |

| Reflective/Adaptive Time |

Time for learning, revision, and integrating feedback |

Enhances adaptive capacity and long-term fit |

While this typology organizes planning time into ideal types, each category interacts dynamically with the institutional and political context. In particular, Political Time often extends beyond simple electoral cycles. It may include deliberate manipulations of the planning timeline to postpone conflict, secure favorable conditions, or accommodate negotiations with powerful actors. For example, local governments may delay plan approvals to avoid public backlash during sensitive periods, or fast-track projects to showcase policy success ahead of elections. These strategic uses of time illustrate how temporal control becomes a political resource, shaping who participates, when, and under what conditions. As such, Political Time demands further scrutiny, as it can both enable and obstruct democratic and sustainable planning outcomes.

- ii.

Delay differentiation matrix.

| Delay Type |

Causal Factors |

Outcome |

Strategic Value |

| Pathological Delay |

Inefficiency, conflict, fragmentation |

Institutional bottlenecks, trust erosion |

Low |

| Procedural Delay |

Legal requirements, inter-agency review |

Compliance and risk management |

Moderate |

| Negotiated Delay |

Stakeholder engagement, social contestation |

Enhanced legitimacy and consensus |

High |

| Strategic Delay |

Intentional pause for better design/data |

Improved environmental or social integration |

Very High |

This matrix helps planners and policymakers diagnose delay causes and choose whether to expedite or strategically extend timelines.

- iii.

Temporal calibration tool. A decision-support tool that helps planners match project complexity with appropriate temporal strategies.

| Project Complexity |

Suggested Temporal Strategy |

| Low (e.g., zoning revision) |

Chronological/Accelerated |

| Medium (e.g., inter-municipal plan) |

Hybrid with structured stakeholder phases |

| High (e.g., large infrastructure + SEA) |

Slow planning + adaptive timelines |

Encourages adaptive temporalities, ensuring that time investments are proportionate to impact, uncertainty, and value conflict.

iv. Temporal justice lens

This normative lens asks: Who controls time? (Planners, politicians, communities, …?); Whose time is prioritized or excluded? (Investors vs. marginalized groups?); Are future generations accounted for (for instance, intergenerational equity)?

Applying this lens ensures that equity and justice are embedded into the temporal design of planning processes.

By embracing this temporal governance framework, spatial planning systems can move beyond binary debates (fast vs. slow; efficient vs. participatory) and instead optimize time use based on stakeholder needs, and systemic complexity. Time, when treated as a flexible and governable dimension, becomes a strategic asset, a lever for sustainability, and institutional resilience.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Evolution of Governance Structures and Legal Design

The transition from the 1999 to the 2015 spatial planning framework in Portugal illustrates a foundational shift in the design logic of governance. The 1999 Decree-Law emphasized top-down coordination, mandatory vertical harmonization across planning levels, and formal participatory rights. While normatively robust, this system suffered from over-regulation and procedural rigidity. In contrast, the 2015 Decree-Law introduced institutional streamlining, separating strategic “programs” from binding “plans” and reinforcing municipal autonomy.

Despite these intentions, the shift toward networked and digitalized governance introduced new coordination burdens. Fewer actors were formally involved, and public consultation chains were compressed, often at the cost of institutional coherence. As Allmendinger & Haughton (2010) suggest, such reforms may trade institutional inclusivity for speed and predictability, undermining long-term legitimacy.

These tensions between reform intentions and practical outcomes are clearly illustrated by the prolonged revision of Almada’s Municipal Master Plan. The attempt to comply with the 2015 framework required reconfiguration of planning diagnostics, institutional realignments, and legal reinterpretation, significantly extending the process and revealing the inertia embedded in legal transitions.

4.2. Participation: Between Efficiency and Inclusion

A key divergence between the two legal frameworks concerns the structure and temporality of public participation. The 1999 framework institutionalized extended and face-to-face engagement, while the 2015 reform reduced participation windows to 30 days and shifted consultation online. This change aligned with broader e-governance goals (OECD, 2020) but unintentionally exacerbated the digital divide and reduced accessibility in less digitally developed regions and socio-demographic groups (Hernández-Partal, 2020; Fan & Zhang, 2022; Abreu & Pinho, 2014).

Participation became more procedural than substantive, fulfilling legal requirements without necessarily enhancing deliberative depth. This resonates with Fung’s (2015) critique of “participation without redistribution,” where stakeholder input is symbolically acknowledged but substantively marginalized. The compressed timelines and digitalization undermined the relational and discursive elements central to deliberative democracy (Forester, 1999; Healey, 1997).

The case of Almada’s thematic participatory congress in 2015 exemplifies how planning time was deliberately extended to foster collective visioning and deeper legitimacy. While time-consuming, this phase represented a negotiated delay that enhanced the social embeddedness of the plan, contrasting with the procedural compression embedded in the 2015 legal reform.

4.3. Planning Delays and Environmental Integration

The analysis reveals that delays were both strategic and systemic. The introduction of Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) under the 2015 framework aimed to mainstream ecological considerations but increased procedural complexity. As Broitman (2020) and Therivel (2010) argue, such delays can serve a productive regulatory function, enabling environmental due diligence and adaptive redesign.

Portuguese municipalities used SEA delays to integrate ecosystem services, risk maps, and biodiversity constraints more thoroughly into spatial plans, demonstrating that “slowness” can improve planning quality when aligned with robust deliberation and data-driven assessments. However, where institutional capacity was weak or fragmented, delays became pathological, producing gridlock and deterring investment (Ball, 2010; Lai et al., 2016).

Almada’s planning trajectory clearly demonstrates both types of delays. Strategic delays (2016–2017) were leveraged to integrate updated legal instruments and ecological dimensions into the plan. However, the post-2018 phase, marked by institutional turnover and pandemic-related disruptions, transitioned into a pathological delay characterized by inertia and disengagement.

4.4. Governance Fragmentation and Actor Roles

The shift from the Monitoring Commission to a newly formed Consultative Commission in Almada, without a coherent handover or timeline, illustrates the governance fragmentation and institutional drift described in the literature. This discontinuity obstructed coordination and diluted institutional memory, further delaying approval.

The decentralization and procedural simplification envisioned in the 2015 reform paradoxically amplified institutional fragmentation. With fewer actors in formal roles and reduced inter-agency coordination, responsibilities became diffused and ambiguous. Swyngedouw (2005) and Brenner (2004) describe this phenomenon as the “Janus-faced” nature of governance reform, where innovation can simultaneously erode accountability structures.

Fragmentation also led to non-linear planning sequences, increased reliance on exceptions and ad hoc mechanisms, and the sidelining of less powerful stakeholders. The absence of a clear governance architecture created bottlenecks, particularly in inter-municipal coordination and environmental review stages.

4.5. Temporal Calibration and Legitimacy Trade-Offs

The analysis confirms the relevance of the proposed Temporal Governance Framework. Projects with low complexity (e.g., minor zoning changes) benefited from accelerated processes. However, strategic and environmentally sensitive interventions required deliberative and reflective timeframes, which were often misaligned with legally prescribed deadlines.

The Almada case provides empirical validation for the Temporal Governance Framework. Each delay type, procedural, negotiated, strategic, and pathological, manifested in distinct phases, highlighting the importance of calibrated planning timelines. This example underscores the need to align planning temporality with project complexity, stakeholder engagement intensity, and institutional capacity.

This mismatch created a recurring legitimacy-speed trade-off (see

Table 1). While shorter processes delivered faster results, they frequently undermined the quality of stakeholder engagement, environmental assessment, and social buy-in. Conversely, slower processes, though contested for inefficiency, fostered greater resilience and community ownership, especially when delays were managed strategically.

5. Conclusions

This article has explored how governance frameworks, participatory mechanisms, and planning temporality interact to shape the effectiveness of TMIs in Portugal. By analyzing the evolution from Decree-Law No. 380/1999 to Decree-Law No. 80/2015, the study reveals a critical paradox: reforms intended to simplify and accelerate planning have, in many cases, introduced new complexities, diluted participatory depth, and challenged institutional coherence.

The comparative analysis underscores that governance quality in spatial planning cannot be reduced to either hierarchical control or procedural streamlining. Instead, it depends on the system’s capacity to foster inclusive participation, and manage time as a strategic planning resource. The introduction of digital platforms and streamlined timelines, while promoting efficiency, has also generated exclusions and weakened deliberative legitimacy, particularly in regions with limited institutional or technological capacity.

Planning delays, often perceived as governance failures, emerged in this study as ambivalent phenomena. While some delays result from administrative inertia or legal fragmentation, others function as strategic instruments that enable deeper stakeholder negotiation, environmental integration, and policy learning. The proposed Temporal Governance Framework supports this nuanced perspective by differentiating types of time and delay, and by offering tools for temporal calibration in complex governance environments.

The Portuguese experience reveals that neither speed nor inclusion alone guarantees effective spatial planning. What is required is an institutionally embedded capacity for reflexivity to distinguish when to accelerate and when to pause, when to consult broadly and when to act decisively. This balance is particularly vital in the face of climate challenges, urban inequality, and declining public trust in institutions.

As such, the study contributes to broader debates in planning theory by arguing for a temporalized understanding of governance, one that accounts for the political, procedural, and distributive dimensions of planning time. It invites scholars and practitioners alike to rethink time not as an external constraint, but as an internal variable that can (and must) be governed with care.