Submitted:

16 May 2025

Posted:

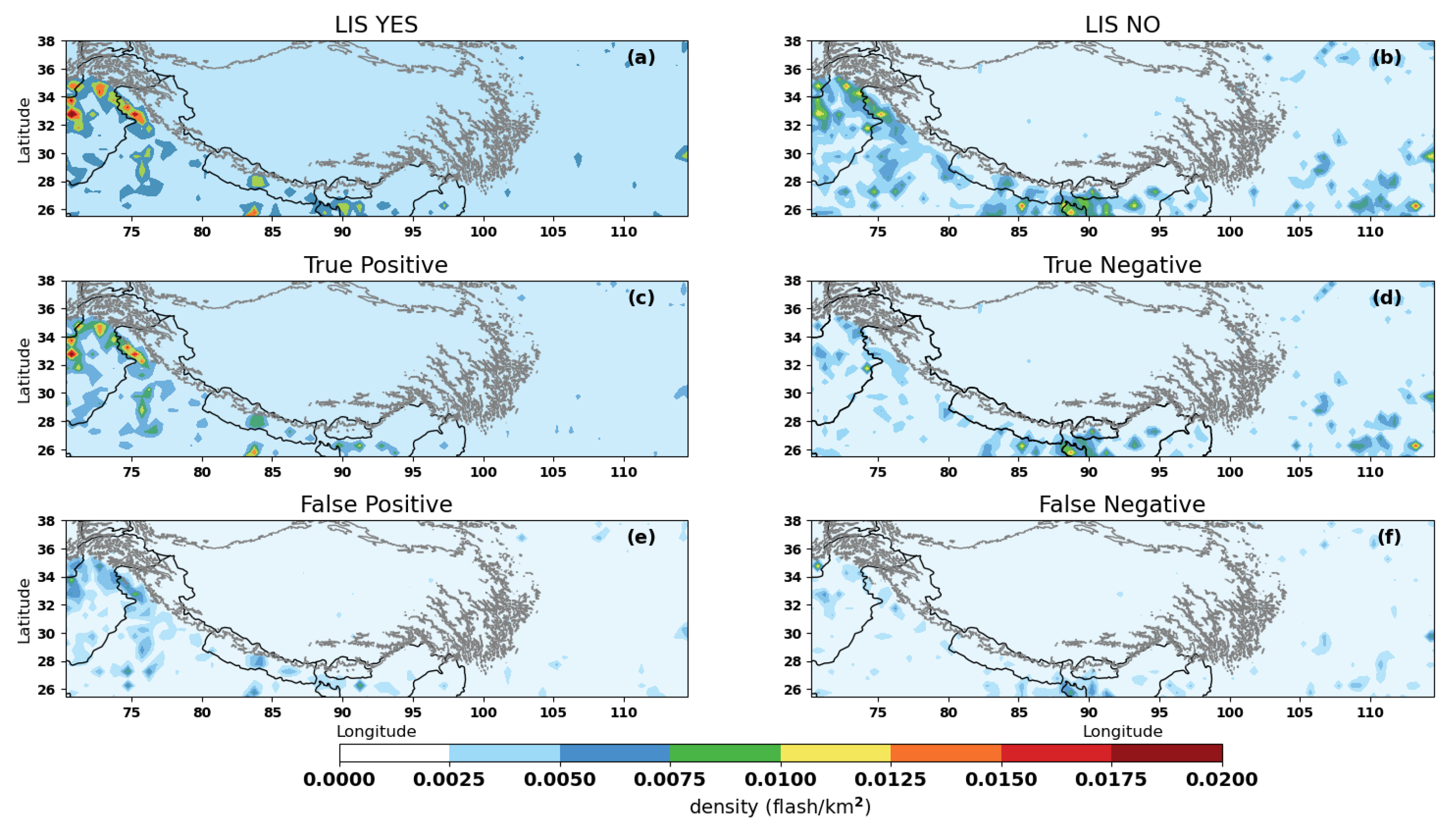

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methodology

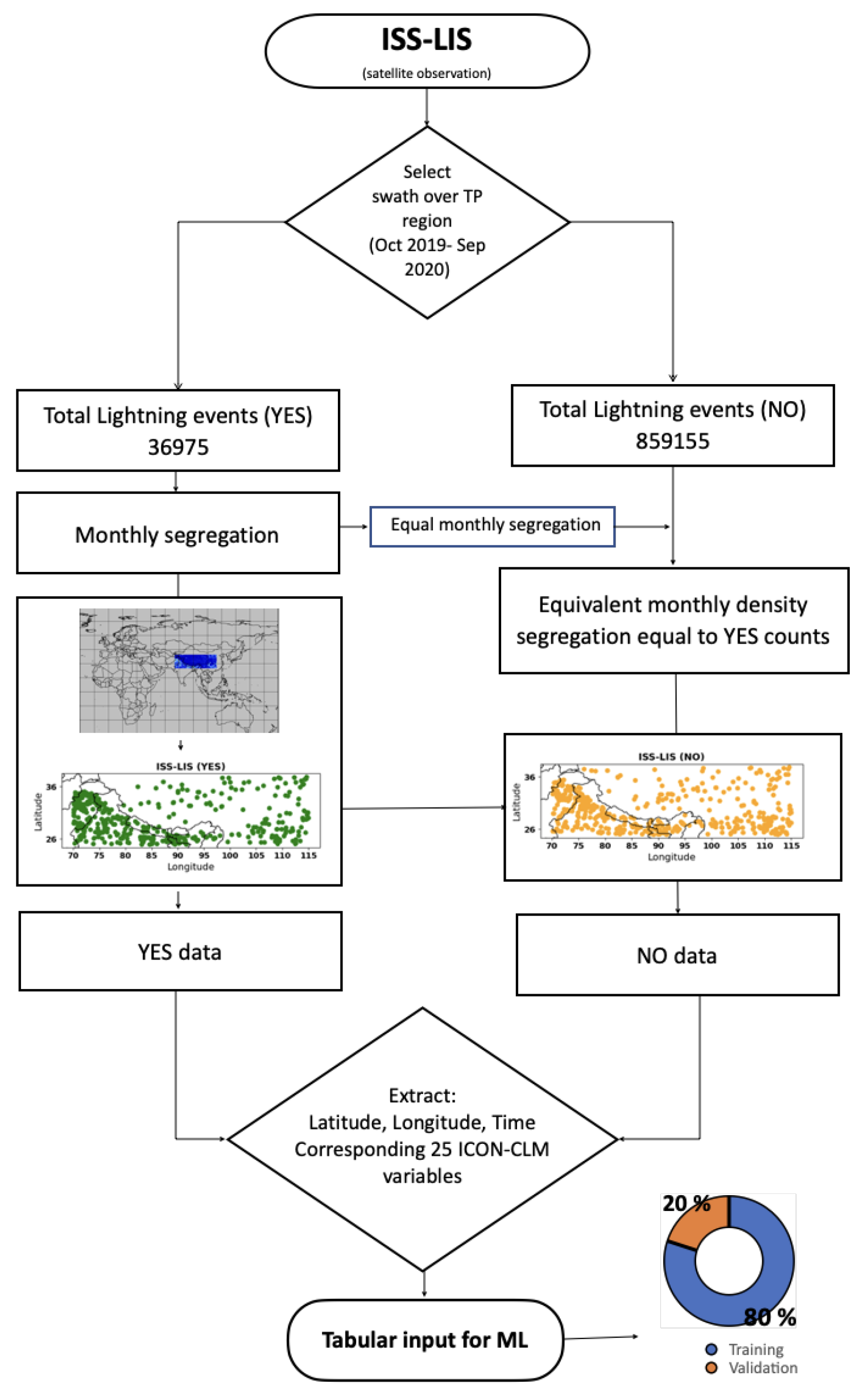

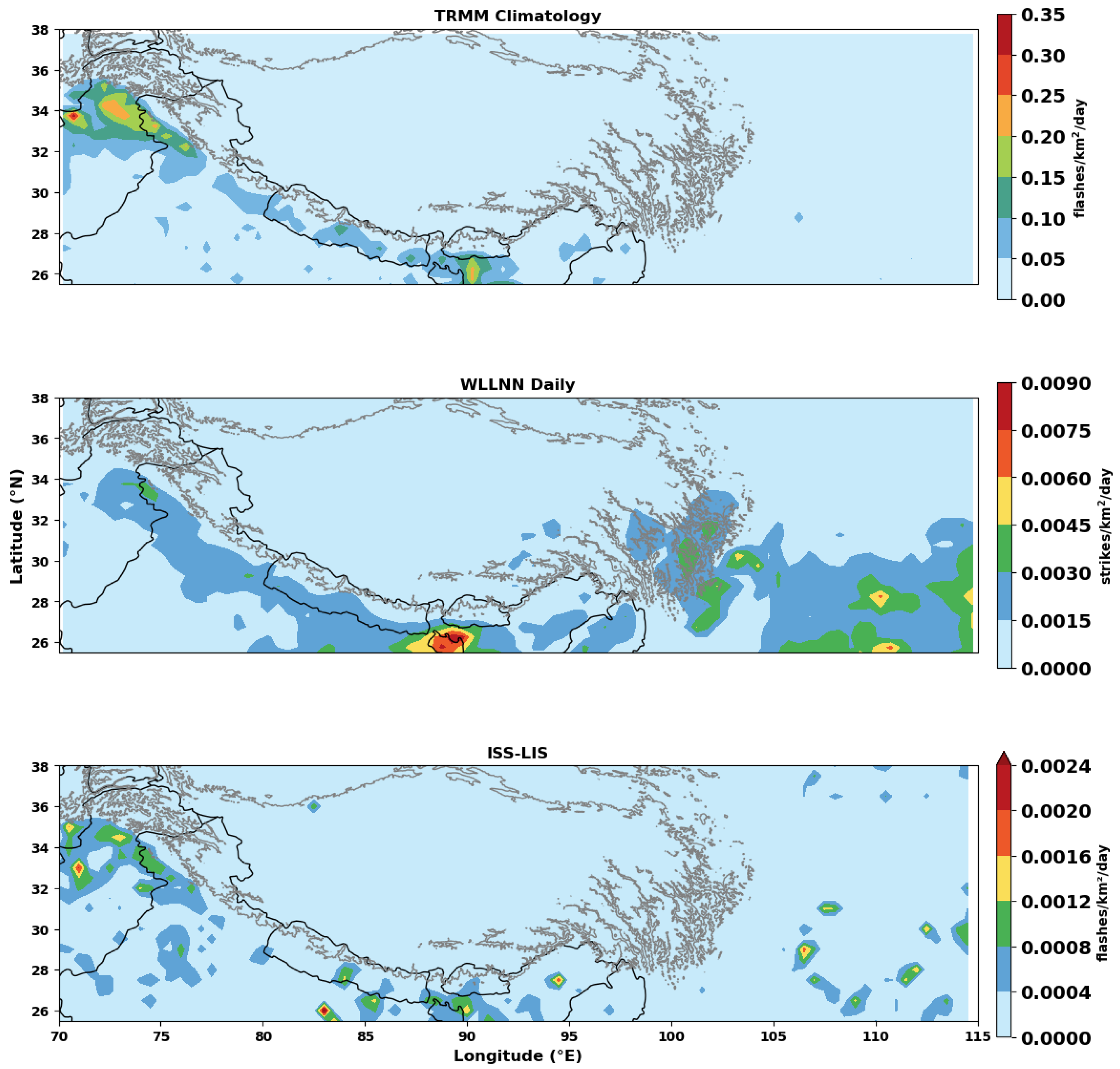

2.1. Lightning Observation

2.2. Numerical Model Setup

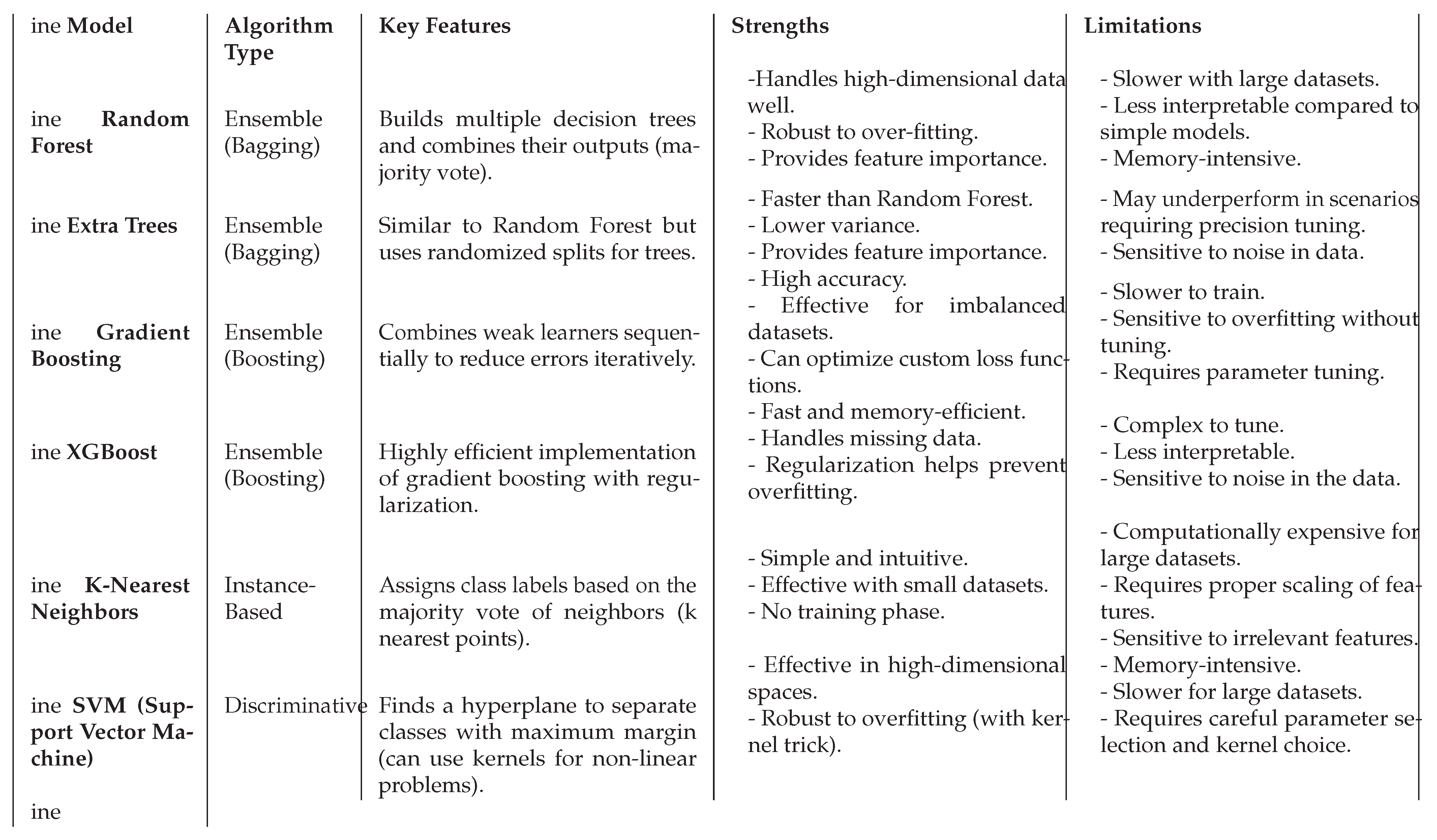

2.3. Machine Learning Models

2.4. Experimental Setup

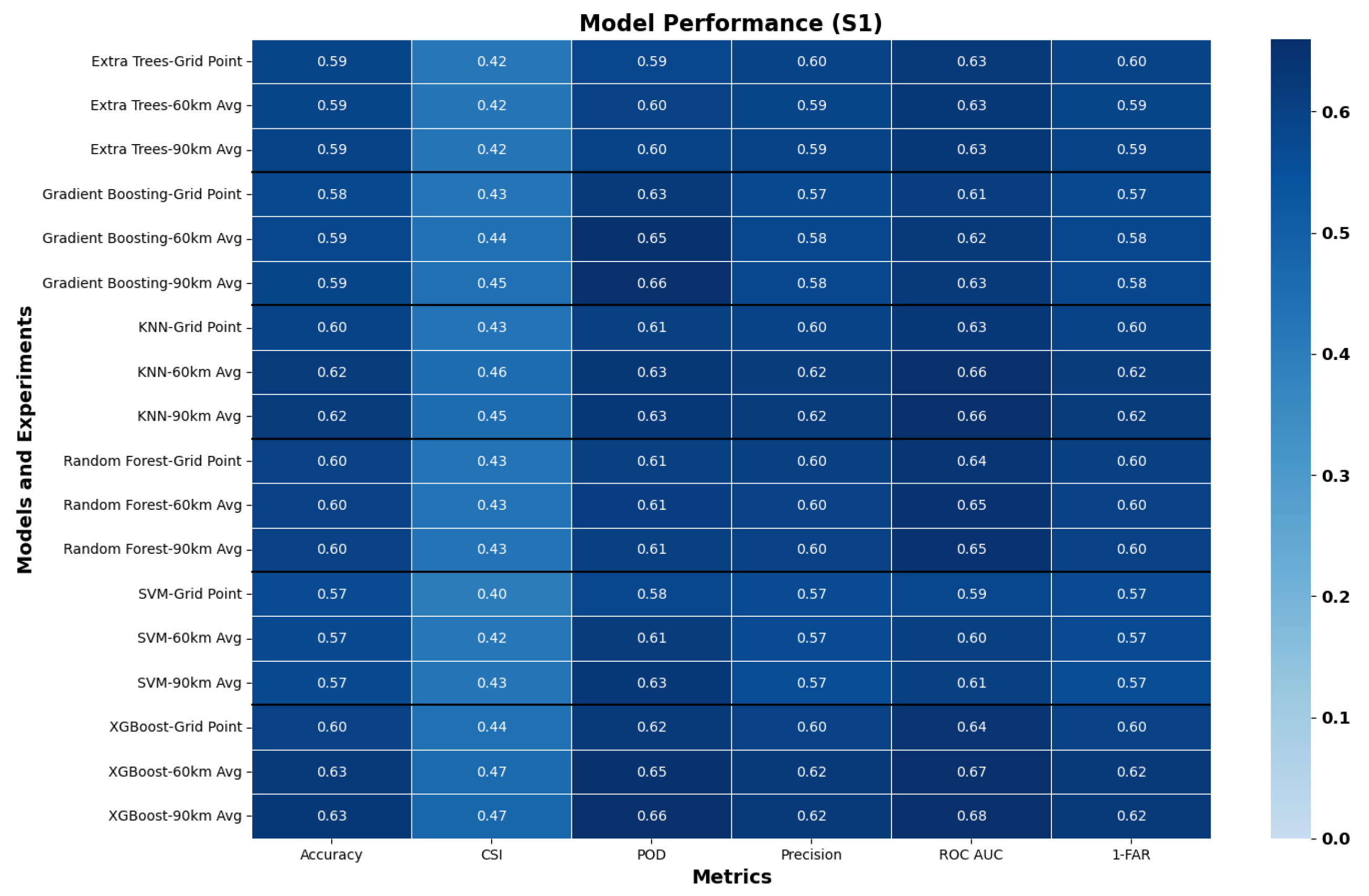

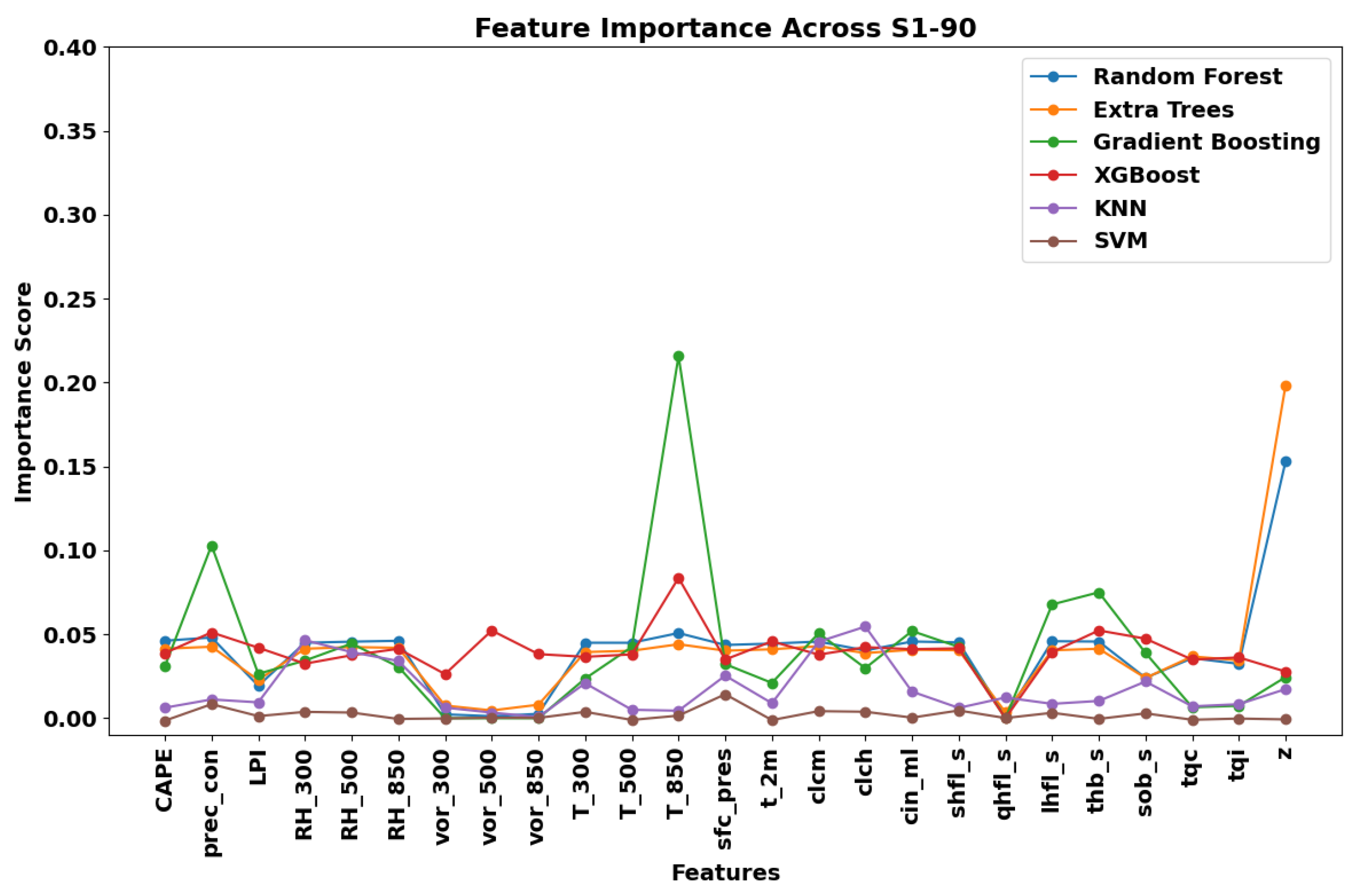

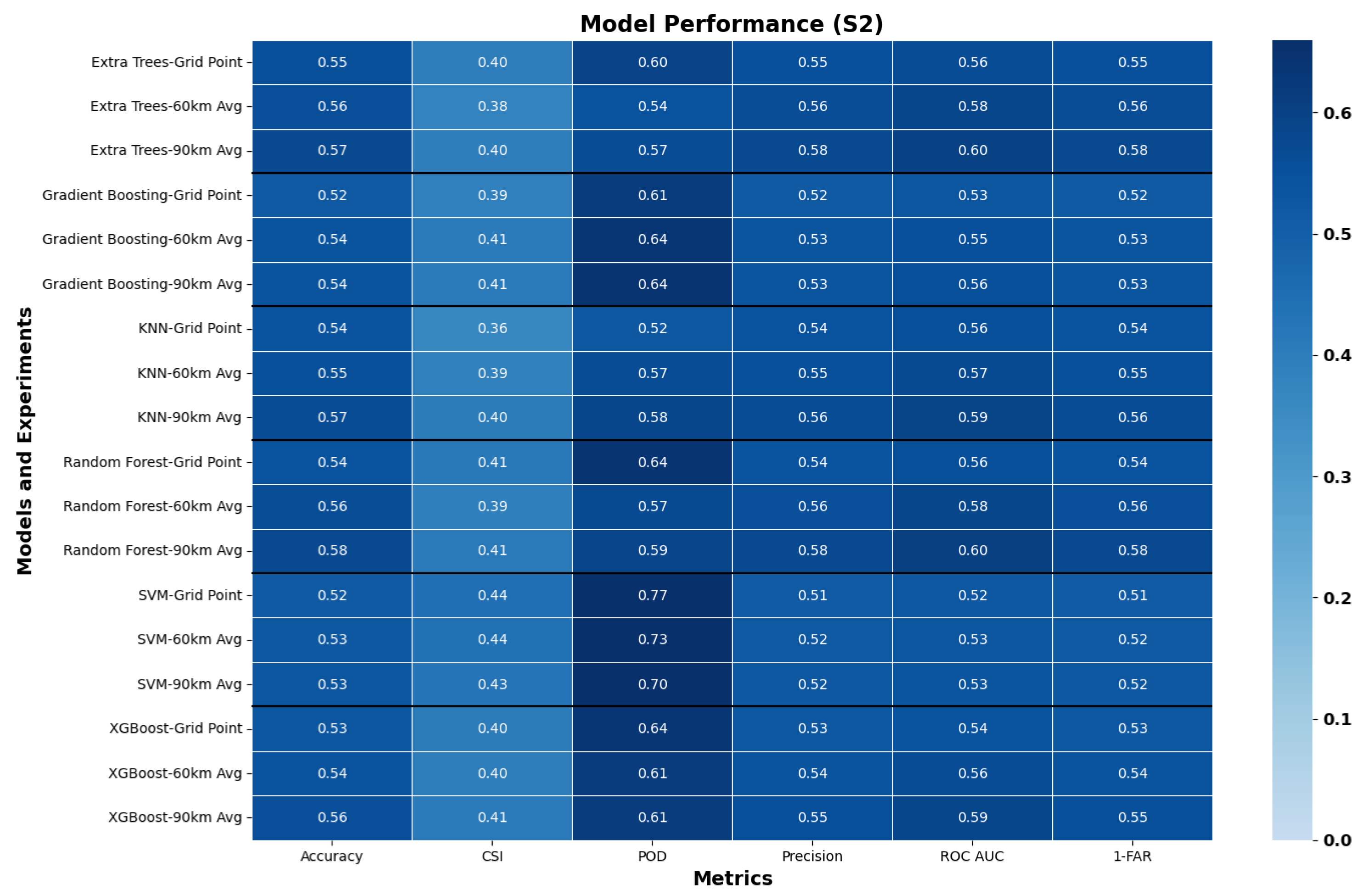

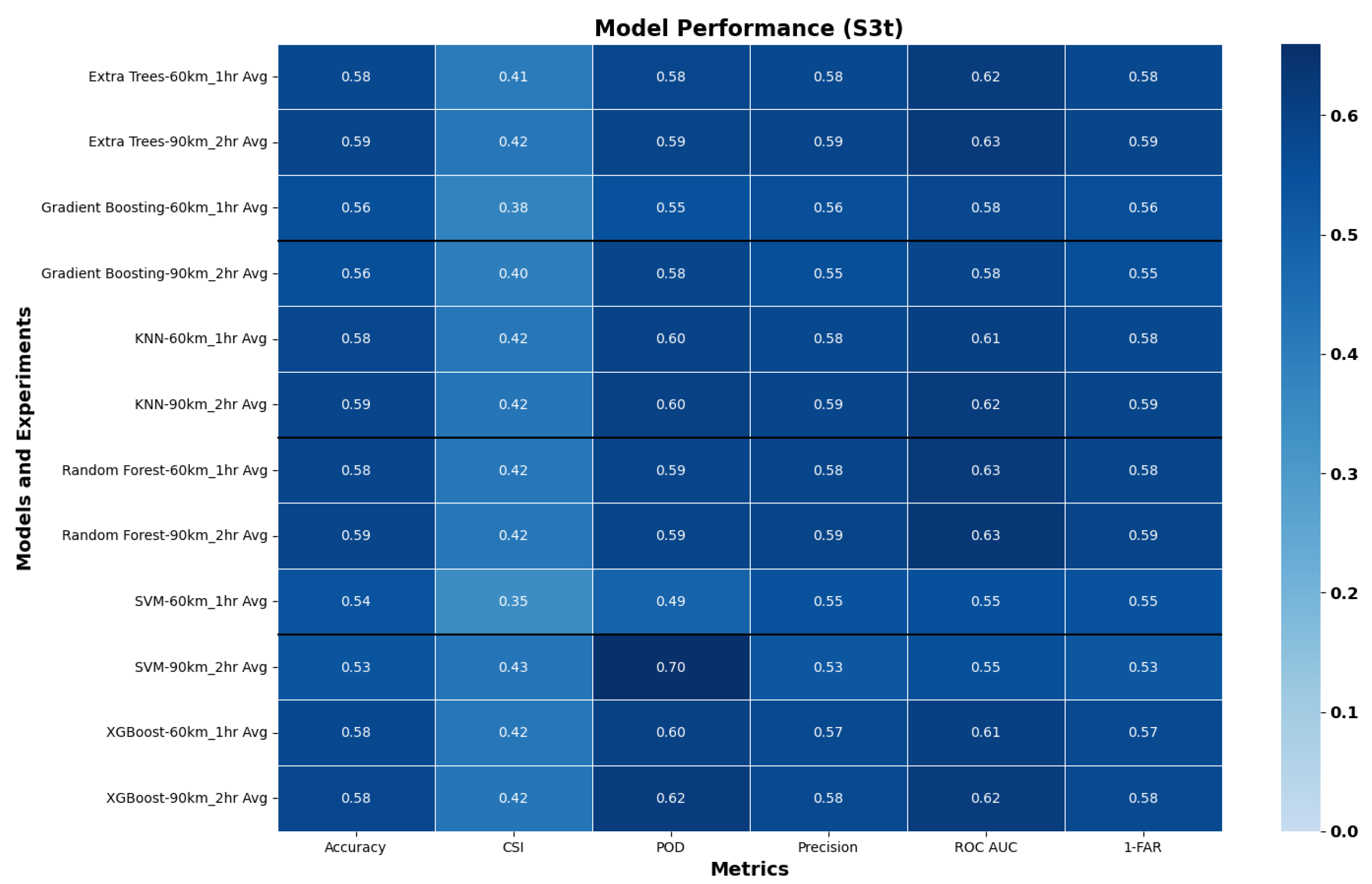

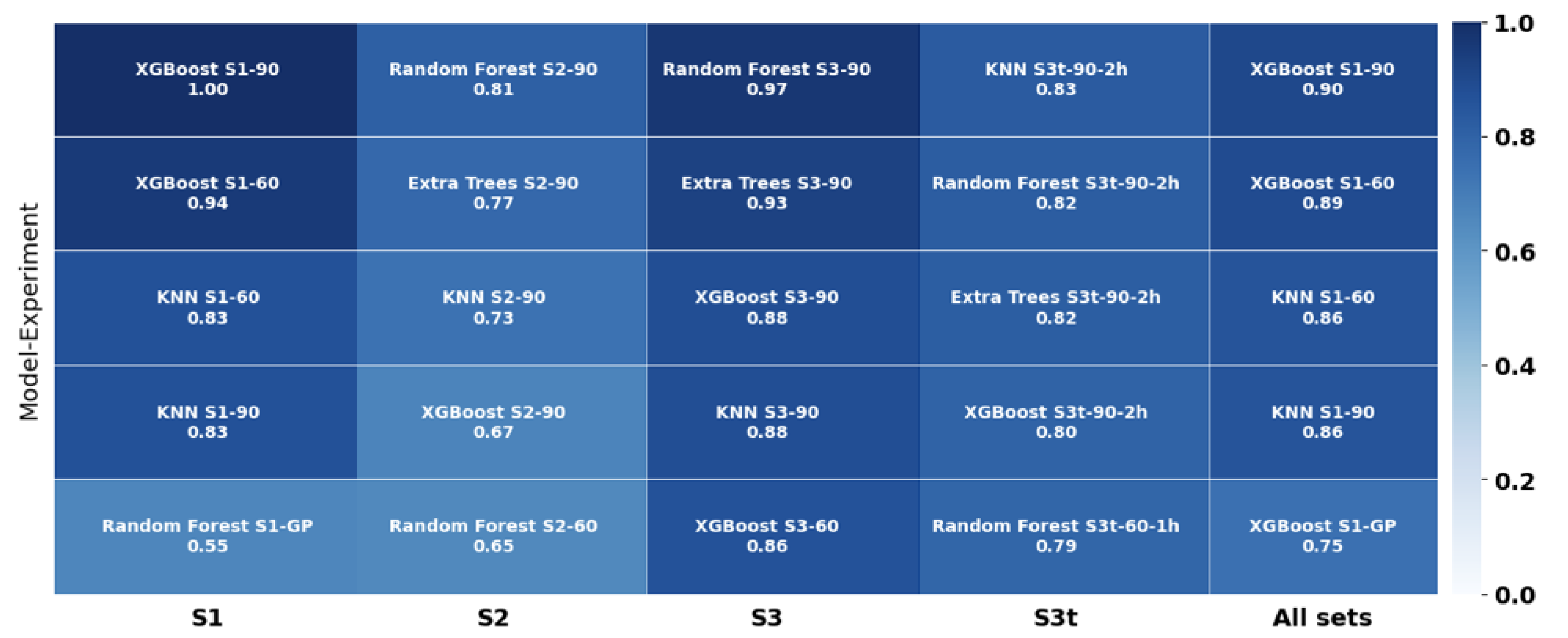

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ISS-LIS | International Space Station - Lightning Imagining Sensors |

| WWLLN | World Wide Lightning Location Network |

| LPI | Lightning Potential Index |

| CP | CAPE times Precipitation |

| RH_850,500,300 | relative humidity at (850, 500, 300) hPa |

| vor_850,500,300 | vorticity at (850, 500, 300) hPa |

| clcm and clch | medium and high cloud cover |

| cin_ml | convective inhibition of mean surface layer parcel |

| lhfl_s and shfl_s | surface latent and sensible heat flux |

| qhfl_s | surface moisture flux |

| sob_s and thb_s | shortwave and longwave net flux at surface |

| tqc and tqi | total column integrated cloud water and ice |

Appendix A

References

- Lal, D. M., & Pawar, S. D. (2009). Relationship between rainfall and lightning over central Indian region in monsoon and premonsoon seasons. Atmospheric Research, 92(4), 402-410.

- Albrecht, R. I. , Goodman, S. J., Buechler, D. E., Blakeslee, R. J., & Christian, H. J. (2016). Where are the lightning hotspots on Earth?. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 97(11), 2051-2068.

- Damase, N. P. , Banik, T., Paul, B., Saha, K., Sharma, S., De, B. K., & Guha, A. (2021). Comparative study of lightning climatology and the role of meteorological parameters over the Himalayan region. Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics, 219, 105527.

- Saunders, C. P. R., Bax-Norman, H., Emersic, C., Avila, E. E., & Castellano, N. E. (2006). Laboratory studies of the effect of cloud conditions on graupel/crystal charge transfer in thunderstorm electrification. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society: A journal of the atmospheric sciences, applied meteorology and physical oceanography, 132(621), 2653-2673.

- Mostajabi, A., Finney, D. L., Rubinstein, M., & Rachidi, F. (2019). Nowcasting lightning occurrence from commonly available meteorological parameters using machine learning techniques. Npj Climate and Atmospheric Science, 2(1), 41.

- Singh, P., & Ahrens, B. (2023). Modeling Lightning Activity in the Third Pole Region: Performance of a km-Scale ICON-CLM Simulation. Atmosphere, 14(11), 1655.

- Adhikari, B. R. (2021). Lightning fatalities and injuries in Nepal. Weather, climate, and society, 13(3), 449-458.

- Adhikari, P. B. (2022). People Deaths and Injuries Caused by Lightning in Himalayan Region, Nepal. International Journal of Geophysics, 2022(1), 3630982.

- Bishop, C. M. , & Nasrabadi, N. M. (2006). Pattern recognition and machine learning (Vol. 4, No. 4, p. 738). New York: springer.

- Geng, Y. A. , Li, Q., Lin, T., Yao, W., Xu, L., Zheng, D.,... & Zhang, Y. (2021). A deep learning framework for lightning forecasting with multi-source spatiotemporal data. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 147(741), 4048-4062.

- Price, C., & Rind, D. (1992). A simple lightning parameterization for calculating global lightning distributions. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 97(D9), 9919-9933.

- Simon, T. , Mayr, G. J., Umlauf, N., & Zeileis, A. (2019). NWP-based lightning prediction using flexible count data regression. Advances in Statistical Climatology, Meteorology and Oceanography, 5(1), 1-16.

- Uhlířová, I. B., Popová, J., & Sokol, Z. (2022). Lightning Potential Index and its spatial and temporal characteristics in COSMO NWP model. Atmospheric Research, 268, 106025.

- Müller, R. , & Barleben, A. (2024). Data-Driven Prediction of Severe Convection at Deutscher Wetterdienst (DWD): A Brief Overview of Recent Developments. Atmosphere, 15(4), 499.

- Brodehl, S. , Müller, R., Schömer, E., Spichtinger, P., & Wand, M. (2022). End-to-End Prediction of Lightning Events from Geostationary Satellite Images. Remote Sensing, 14(15), 3760.

- Chatterjee, C., Mandal, J., & Das, S. (2023). A machine learning approach for prediction of seasonal lightning density in different lightning regions of India. International Journal of Climatology, 43(6), 2862-2878.

- Rameshan, A. , Singh, P., & Ahrens, B. (2025). Cross-Examination of Reanalysis Datasets on Elevation-Dependent Climate Change in the Third Pole Region. Atmosphere, 16(3), 327.

- Lang, Timothy & National Center for Atmospheric Research Staff (Eds). Last modified 2023-09-04 "The Climate Data Guide: Lightning data from the TRMM and ISS Lightning Image Sounder (LIS): Towards a global lightning Climate Data Record.” Retrieved from https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/climate-data/lightning-data-trmm-and-iss-lightning-image-sounder-lis-towards-global-lightning on 2025-02-26.

- Mach, D. M. , Christian, H. J., Blakeslee, R. J., Boccippio, D. J., Goodman, S. J., & Boeck, W. L. (2007). Performance assessment of the optical transient detector and lightning imaging sensor. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 112(D9).

- Singh, P. , & Ahrens, B. (2023). Lightning Potential Index Using ICON Simulation at the km-scale over the Third Pole Region: ISS-LIS events and ICON-CLM simulated LPI. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

- Vahid Yousefnia, K. , Bölle, T., Zöbisch, I., & Gerz, T. (2024). A machine-learning approach to thunderstorm forecasting through post-processing of simulation data. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 150(763), 3495-3510.

- Tetko, I. V. , van Deursen, R., & Godin, G. (2024). Be aware of overfitting by hyperparameter optimization!. Journal of Cheminformatics, 16(1), 1-11.

- Cecil, D. J. , Buechler, D. E., & Blakeslee, R. J. (2014). Gridded lightning climatology from TRMM-LIS and OTD: Dataset description. Atmospheric Research, 135, 404-414.

- Rodger, C. J. , Brundell, J. B., Holzworth, R. H., & Lay, E. H. (2009, April). Growing detection efficiency of the world wide lightning location network. In AIP Conference Proceedings (Vol. 1118, No. 1, pp. 15-20). American Institute of Physics.

- Romps, D. M. , Charn, A. B., Holzworth, R. H., Lawrence, W. E., Molinari, J., & Vollaro, D. (2018). CAPE times P explains lightning over land but not the land-ocean contrast. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(22), 12-623.

- Saleh, N., Gharaylou, M., Farahani, M. M., & Alizadeh, O. (2023). Performance of lightning potential index, lightning threat index, and the product of CAPE and precipitation in the WRF model. Earth and Space Science, 10(9), e2023EA003104.

- Lynn, B. , & Yair, Y. (2010). Prediction of lightning flash density with the WRF model. *Advances in Geosciences, 23*, 11–16. [CrossRef]

- Natekin A, Knoll A. (2013). Gradient boosting machines, a tutorial. Front Neurorobot. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- El Alaoui, M. (2021). Fuzzy TOPSIS: Logic, Approaches, and Case Studies. CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Tippett, M. K. , & Koshak, W. J. (2018). A baseline for the predictability of US cloud-to-ground lightning. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(19), 10-719.

- Mansouri, E., Mostajabi, A., Tong, C., Rubinstein, M., & Rachidi, F. (2023). Lightning Nowcasting Using Solely Lightning Data. Atmosphere, 14(12), 1713.

- Leinonen, J. , Hamann, U., & Germann, U. (2022). Seamless lightning nowcasting with recurrent-convolutional deep learning. Artificial Intelligence for the Earth Systems, 1(4), e220043.

- Giannaros, T. M., Kotroni, V., & Lagouvardos, K. (2015). Predicting lightning activity in Greece with the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model. Atmospheric Research, 156, 1-13.

- Uhlířová Babuňková, I., Popová, J., & Sokol, Z. (2022). Lightning Potential Index and its spatial and temporal characteristics in COSMO NWP model. Atmospheric Research, 268, 106025. [CrossRef]

- Yair, Y. , Lynn, B., Price, C., Kotroni, V., Lagouvardos, K., Morin, E.,... & Llasat, M. D. C. (2010). Predicting the potential for lightning activity in Mediterranean storms based on the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) model dynamic and microphysical fields. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 115(D4).

- Zängl, G. , Reinert, D., Rípodas, P., & Baldauf, M. (2015). The ICON (ICOsahedral Non-hydrostatic) modelling framework of DWD and MPI-M: Description of the non-hydrostatic dynamical core. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 141(687), 563-579.

- Pham, T. V., Steger, C., Rockel, B., Keuler, K., Kirchner, I., Mertens, M., ... & Früh, B. (2021). ICON in Climate Limited-area Mode (ICON release version 2.6. 1): a new regional climate model. Geoscientific Model Development, 14(2), 985-1005.

- Poelman, D. R. , & Schulz, W. (2020). Comparing lightning observations of the ground-based European lightning location system EUCLID and the space-based Lightning Imaging Sensor (LIS) on the International Space Station (ISS). Atmospheric Measurement Techniques, 13(6), 2965-2977.

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | Overall correctness of the model | |

| Precision | Measures how many predicted events actually happened | |

| POD(Recall) | Measures how well the model detects actual events | |

| FAR | Measures how many predicted events were false alarms | |

| CSI | Balances between false alarms and missed events | |

| ROC-AUC | Measures model’s ability to distinguish classes (lightning and no-lightning) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).