1. Introduction

Transformer-based architectures are currently at the forefront of methods for sequential modeling and generation. This paper examines the role of vocabulary size in the tokenization of musical harmony in symbolic music. Harmony—particularly melodic harmonization—is a well-suited domain for studying tokenization, as it encompasses concepts that can be either condensed into a few abstract symbols or expanded in a more analytical manner. Additionally, context plays a significant role at both the local level (chords before and after a given point) and the global level (structural repetitions or harmonic relationships with other musical components such as melody), making the transformer architecture a natural candidate for harmony modeling. Although the vocabulary size in harmony, as shown in the literature and in this study, is trivially small compared to that used in large language models (LLMs) for natural language, it still offers meaningful insights. Despite the small vocabulary size, the importance of context remains critical, thereby exposing the trade-offs involved in using fewer versus more tokens.

Generally, in both natural language and harmonic modeling, smaller vocabulary sizes lead to longer tokenized sequences (i.e., more tokens per sentence), requiring more transformer steps per sequence, albeit with smaller embedding matrices (reducing memory and computation). Conversely, larger vocabulary sizes yield shorter sequences and require fewer transformer steps, but with larger embedding matrices (increasing memory and computation). Vocabulary size also impacts generalization and rare word handling. Smaller vocabularies, as in subword-based methods like Byte-Pair Encoding [

1] or SentencePiece [

2], are better at handling rare or out-of-vocabulary (OOV) words by breaking them into smaller units. Larger vocabularies improve efficiency for common words but often struggle with rare or unseen terms, such as domain-specific vocabulary, and may lead to inefficient training due to the enlarged embedding matrix.

Summarizing the literature on LLMs, smaller vocabularies tend to improve generalization but necessitate deeper networks to process longer sequences. Larger vocabularies can improve training efficiency for common tokens but are prone to overfitting and may handle rare words poorly. These trade-offs have been evaluated in major model developments. For example, the T5 paper [

3] advocated for smaller vocabularies (32K subwords) to achieve a balance between generalization and efficiency, while GPT-3 [

4] used a 50K BPE vocabulary to balance computational efficiency and rare word coverage. Similarly, [

5] examined scaling laws and found that increased vocabulary size raises memory demands without necessarily improving perplexity, indicating that model depth and sequence length often have a greater impact.

In the context of harmony, chords can be represented in several ways. At one extreme, each chord is treated as a unique symbol, yielding a "large" vocabulary (436 tokens, including melody and structural tokens), where each chord is independent and orthogonal to all others. This method ignores potential relationships between chords—e.g., shared roots or pitch classes. At the other extreme, chords are represented as sets of pitch classes, omitting higher-level information such as root or chord type. This produces a minimal vocabulary of just 12 pitch classes, with all chords formed through combinations of these. This paper explores several intermediate approaches that preserve some higher-level features while maintaining moderate vocabulary sizes between these extremes.

Regarding the current literature on chord-to-chord generation [

6] and melodic harmonization, the most common representation involves chord symbols, where each chord is assigned a unique, orthogonal token. Such approaches have been used in models employing Hidden Markov Models with a small chord vocabulary (35 symbols) [

7], or in data-derived representations using the General Chord Type (GCT) format [

8,

9,

10]. Deep learning models, including BiLSTM-based architectures, have used limited vocabularies of 24 [

11] or 48 chord symbols [

12,

13], while others use larger vocabularies of chord symbols [

14,

15], up to 1462 unique tokens [

16]. Chord symbols have also been used as auxiliary representations for tasks such as four-part harmonization [

17] and piano accompaniment generation [

18].

Chord symbol tokenization remains popular in transformer-based architectures. For instance, [

19] explored controllable harmonic sequence generation with a vocabulary of 72 chords (12 roots × 6 chord types). A similar setup with 49 chords (12 roots × 4 chord types + one `no chord’ symbol) was used for four-part harmonization in [

20]. A broader vocabulary involving 11 chord types was adopted in [

21], where chords were modeled as functional harmony scale degrees

1. A transformer with a T5 encoder-decoder architecture also used chord symbols in a multitask framework, including melodic harmonization [

22].

At the other end of the spectrum, harmony has been modeled by decomposing chords into their constituent pitch classes or even individual pitches with octave information [

23], typically using LSTM-based architectures. These chord “spelling” approaches have also been applied in transformer models [

24]. Some methods further annotate pitch-class tokens with root and inversion information, as seen in BiGRU-based generation [

25], diffusion-based systems [

26], and LSTM reinforcement learning for melodic harmonization [

27]. Other studies represent root and quality separately for melodic harmonization using BiLSTM [

28] or for emotion-conditioned harmonization using hierarchical VAE models [

29].

This paper investigates the effects of different tokenization strategies for symbolic harmony in basic transformer-based sequence modeling tasks, namely masked language modeling and melody-conditioned harmony generation.

Section 2 describes the tokenization methods examined.

Section 3 outlines the experimental setup, including datasets, training analysis using information-theoretic measures, and evaluation of generated sequences using token-level, symbolic, and audio-based metrics. Results are presented in

Section 4, and conclusions are discussed in

Section 5. The code of the paper is available online

2.

2. Harmony Tokenization Methods

The symbolic chord representations examined in this study are based on information from lead sheet music. Lead sheets encode harmony using chord symbols and melody using standard Western notation. This study focuses on how harmonic content can be tokenized more effectively for use in common tasks with standard transformer-based models. All tokenization methods follow well-established principles for symbolic music representation (e.g., bar-based tokenization, position annotation at fixed time resolutions). The key differences lie in how the chord symbols themselves are tokenized and the extent to which chord information is decomposed into constituent components.

2.1. Melody and Harmony Tokenization Foundations

In Western lead sheet music, harmonic and melodic information are closely intertwined. The tasks studied here—masked language modeling and melodic harmonization—incorporate melodic context. However, since the primary focus is on harmony, a simple tokenization scheme is used for the melody. Additionally, chord position information is shared across all tokenization methods.

Beyond the standard special tokens for sequence start, end, mask, unknown, and padding, melody tokenization includes:

<bar> to indicate a new bar,

<rest> to indicate a rest,

position_BxSD for note onset time,

P:X for MIDI pitch.

The onset position format

BxSD encodes the beat within the bar (

B) and the subdivision of the beat (

SD), quantized into eight parts

3. A single time signature is assumed per piece, with tokens of the form

ts_NxD, where

N and

D denote the numerator and denominator, respectively. In the employed dataset, numerators range from 1 to 10, and denominators are either 4 or 8.

All harmony tokenizations are built on a shared base scheme. They borrow special tokens (e.g., unknown, padding, mask) and position tokens from melody tokenization. In addition, all harmony sequences begin with a special token <h> to mark the start of harmony.

2.2. Harmony Tokenization

The harmony tokenizers differ in how they represent chords – specifically, how much information is included within each token. Four tokenization methods are evaluated:

ChordSymbol: Each token directly encodes the chord symbol as it appears in the lead sheet, e.g.,

C:maj7. To ensure homogeneity between different representations of the same chord symbols (e.g., Cmaj and C

▵) all chords are transformed into their equivalent MIR_eval [

30] symbol according to their pitch class correspondence.

RootType: Separate tokens are used for the root and the quality of the chord, e.g., C and maj7.

PitchClass: Chord symbols are not used; instead, the chord is represented as a set of pitch classes. For example, a Cmaj7 chord is tokenized as chord_pc_0, chord_pc_4, chord_pc_7, and chord_pc_11.

RootPC: Similar to the previous method, but includes a dedicated token for the root pitch class, e.g., root_pc_0, chord_pc_4, chord_pc_7, chord_pc_11. This helps disambiguate chords with similar pitch class sets (e.g., Cmaj6 vs. Am7).

Table 1 provides an example of how the first two bars of a harmonic sequence are tokenized using each of the four methods.

3. Experimental Setup, Models, Data and Evaluation Approach

This section describes the experimental framework designed to evaluate the effectiveness of the examined tokenizers across transformer-based learning tasks. We focus on masked language modeling (MLM) and melody harmonization using encoder-decoder and decoder-only architectures. The evaluation spans token-level, symbolic music, and audio metrics, with an emphasis on the ability of each tokenizer to support the generation of outputs that closely resemble ground-truth data.

Specifically, the following tasks are considered:

Masked Language Modeling (MLM) is a self-supervised learning objective used to train transformer-based encoders like BERT [

31] and RoBERTa [

32]. In MLM, a portion of the input tokens is randomly masked (typically 15% in BERT) and replaced with a special

<mask> token, while the model is trained to predict the original tokens based on the surrounding context. Unlike traditional left-to-right language models, MLM allows bidirectional context learning, enabling deeper semantic understanding. In the current study we employ the RoBERTa strategy, which removes the Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) task and focus only on predicting the

<mask> tokens.

Encoder-decoder melody harmonization performed by BART [

33]. In this task the melody is used as input in the encoder and the harmony is generated autoregressively in the decoder until a stopping criterion (end-of-sentence token is generated or maximum number of tokens is achieved).

Decoder-only melody harmonization performed by GPT-2 [

34]. This follows an autoregressive approach where harmony tokens are generated sequentially from left to right. Given an initial prompt of melody tokens, the model predicts the next harmony token based on previous tokens, iterating until a stopping criterion (end-of-sentence token is generated or maximum number of tokens is achieved). All transformer architectures for melodic harmonization in the literature so far are encoder-decoder architectures, but we want to generalize the study to the possibilities offered by decoder-only architectures.

We examine the following three tasks:

Masked Language Modeling (MLM) A self-supervised objective for training encoder-based models such as BERT [

31] and RoBERTa [

32]. MLM randomly masks a subset of input tokens (typically 15%) and trains the model to recover the original tokens using contextual cues. We follow the RoBERTa strategy, removing the Next Sentence Prediction (NSP) component and focusing solely on predicting

<mask> tokens.

Encoder-Decoder Melody Harmonization Using BART [

33], this task encodes a melody and generates a corresponding harmony sequence autoregressively until an end-of-sequence token or a token limit is reached.

Decoder-Only Melody Harmonization Modeled using GPT-2 [

34], harmony tokens are generated from left to right, conditioned on a melody prompt. While prior work typically uses encoder-decoder models for harmonization, we explore the applicability of decoder-only models in this context.

In the MLM task, both melody and harmony tokens are included in the input sequence, and masked tokens are sampled from either component. This setup evaluates the contextual support each tokenizer provides for modeling the interaction between melody and harmony. All tasks enforce a maximum of 512 tokens each for the melody and harmony. To ensure alignment across bars, if either component exceeds the limit, tokens corresponding to the last bar of both the melody and harmony are iteratively removed until both sequences fall within the limit. This guarantees bar-level correspondence across tasks.

We use 17,476 lead sheets from the HookTheory dataset [

12], stored in musicXML format. Since pieces vary in key, we apply a key normalization strategy to reduce tonal imbalance: major-mode pieces are transposed to C major and minor-mode pieces to A minor, based on the Krumhansl key-finding algorithm [

35]. This mirrors approaches from prior work [

19,

21], while also considering the shared pitch-class roles between C major and A minor [

7]. We split the data into 90% training and 10% testing/validation, yielding 15,956 training and 1,520 validation/test pieces.

To assess how tokenizer design influences generation quality (in BART and GPT-2) we evaluate harmonization outputs from the test set using two main categories of metrics:

Token-Based Metrics: Measure internal consistency and structural validity of generated token sequences.

Symbolic Music Metrics: Capture harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic attributes of the generated sequences, independent of exact token alignment with ground truth.

We evaluate 1,520 validation examples to quantitatively compare the tokenizer strategies and address the following questions:

How closely do generated token sequences align with the ground truth?

Are the generated chord progressions musically coherent, harmonically accurate, and rhythmically appropriate?

How effectively do BART and GPT-2 leverage different tokenizations to generate high-quality harmonizations?

3.1. Token Metrics

To evaluate how well each tokenizer structures its output, we use two token-based metrics that do not directly rely on matching tokens to a single ground-truth reference. Since each of the four proposed tokenizers maps the data to a distinct vocabulary and format, a one-to-one token-level alignment with a common ground truth is not straightforward. Instead, these metrics focus on the internal validity and coherence of each generated token sequence.

Duplicate Ratio (DR)

The first metric measures the ratio of duplicate tokens within each generated output. For melodic harmonization, redundant or erroneously repeated tokens can indicate structural problems in the model’s output. A lower duplicate ratio generally implies better quality outputs, as it signifies that the model avoids producing consecutive or repetitive tokens with no musical justification. While our tokenizer designs inherently limit duplication, this metric still provides a useful indication of how consistently each baseline model adheres to the token constraints in practice.

Token Consistency Ratio (TCR)

Inspired by

Tokenization Syntax Error (TSE) of Fradet et al. [

36] and by edit-distance ideas such as

Token Error Rate (TER) [

37], we propose the

Token Consistency Ratio (TCR). While TSE reports the proportion of

syntax errors in note-level streams and TER measures the distance to a ground-truth sequence, TCR instead reports the proportion of

valid tokens in a generated chord sequence, independent of any reference. For each of our four tokenizers (Chord Symbol, Root Type, Pitch Class, and Root Pitch Class) we automatically derive a finite-state grammar that encodes legal successions of token types (e.g., <bar> → <pos> → <chord tokens> → <pos> or <bar> etc.). Given a generated token list, we count how many tokens respect this grammar and compute

so higher values denote greater internal consistency and therefore a better grasp of the tokenizer’s musical syntax.

3.2. Symbolic Music Metrics

We employ a set of musical-based metrics that evaluate the generated harmonies according to key musical attributes. Specifically, the first two categories for

chord progressions and

chord-to-melody harmonicity proposed by [

12] have been widely used in the literature [

14,

19,

21] and show how well the chords fit both the harmonic and the melodic context. The final category,

harmonic rhythm [

16], focuses on the rhythmic placement of chords (and therefore on the position tokens which is an important aspect of the examined tokenizers) to ensure that the chord changes align musically with the underlying melody.

3.2.1. Chord Progression Coherence and Diversity

We first evaluate each chord sequence as a standalone entity, focusing on the variety and smoothness of its progression.

Chord Histogram Entropy (CHE)

Given a chord sequence, we form a histogram of chord occurrences and normalize these counts to obtain a probability distribution. We then calculate the entropy of this distribution:

where

is the normalized frequency of the

k-th chord in the sequence, and

C is the total number of distinct chord bins. A higher CHE value suggests a more uniform (and thus more varied) distribution of chords, whereas a lower CHE value indicates stronger repetition of a small set of chords.

Chord Coverage (CC)

This metric counts the distinct chord types within a piece, reflecting the richness of the overall harmonic vocabulary. A higher CC value indicates greater chord variety and, consequently, potentially more interesting or exploratory progressions.

Chord Tonal Distance (CTD)

To assess the smoothness between consecutive chords, we compute the average

tonal distance [

38] between every pair of adjacent chords in a sequence. First, each chord is converted into its pitch class profile (PCP) representation and projected into a 6-D tonal space. We then calculate the Euclidean distance between each pair of adjacent chord vectors. A lower CTD value signifies smoother, more closely related chord transitions, while a higher value indicates more abrupt harmonic changes.

3.2.2. Chord/Melody Harmonicity

We next evaluate how effectively the generated chord progressions support a given melody.

Chord Tone to non-Chord Tone Ratio (CTnCTR)

This metric compares the number of chord tones in the melody (

) to the number of non-chord tones (

) and “proper” non-chord tones (

) that lie within two semitones of the immediately following note:

Chord tones are melody notes whose pitch classes match those in the corresponding chord. Non-chord tones lie outside the chord pitches, while “proper” non-chord tones are closer in pitch to the next note. Higher CTnCTR values indicate stronger chord-to-melody alignment, as more melody notes fit harmonically into the chord.

Pitch Consonance Score (PCS)

For each melody note, we first identify the active chord and “raise” each chord tone to an octave immediately below or equal to the melody note’s pitch. We then measure the semitone interval between the melody note and each chord tone: intervals of 0, 3, 4, 7, 8, or 9 semitones receive a score of +1, a perfect fourth (5 semitones) scores 0, and all other intervals score -1. To obtain the final metric, melody notes are grouped into 16th-note windows; the consonance scores within each window are averaged, and then these window-level averages are further aggregated over the entire piece. A higher PCS indicates more consonant intervals between the melody and chord tones overall.

Melody-Chord Tonal Distance (MCTD)

The calculation is similar with CTD; first we represent each melody note by a PCP vector (in this case becomes a one-hot encoding). Then, this vector along with chord’s PCP are projected into a 6-D tonal space, and the Euclidean distance between is computed. MCTD is the average of these distances over all melody notes, weighted by each note’s duration. A lower MCTD value indicates that the chord progression remains harmonically close to the melody, while a higher value suggests more distant and potentially dissonant chord-melody pairings.

3.2.3. Harmonic Rhythm Coherence and Diversity

Although the metrics discussed so far capture chord diversity and chord–melody alignment, they do not address the temporal distribution of chord changes. To fill this gap, we include a set of harmonic rhythm metrics that consider only the positioning tokens from the proposed tokenizers and evaluate how chords align with the underlying beat and how varied their placements are throughout a piece.

Harmonic Rhythm Histogram Entropy (HRHE)

This metric parallels

Chord Histogram Entropy, but focuses on the frequency distribution of harmonic rhythm types rather than chord types. Specifically, we construct a histogram of all chord-change placements, normalize them, and compute the entropy:

where

is the normalized frequency of the

u-th distinct harmonic rhythm pattern, and

U is the total number of such patterns. A higher HR-HE indicates a more uniform and varied distribution of chord placements across beats.

Harmonic Rhythm Coverage (HRC)

Similarly to Chord Coverage, this metric counts the number of distinct harmonic rhythm types in a sequence. Each unique pattern of chord change (e.g., which beats receive new chords) is treated as a “type.” A higher HRC indicates that the model uses a broader range of chord placement patterns.

Chord Beat Strength (CBS)

In this metric, each chord is assigned a “beat strength” score based on the position of its onset in the bar. Specifically, we apply the following scoring scheme:

Score 0 if a chord occurs exactly at the start of the measure (onset 0.0).

Score 1 if it coincides with any other strong beat (e.g., onsets 1.0, 2.0, 3.0 in a 4/4 measure).

Score 2 if placed on a half-beat (e.g., 0.5, 1.5, etc.).

Score 3 if on an eighth subdivision (e.g., 0.25, 0.75).

Score 4 otherwise.

To calculate the overall CBS, we take a piece’s average beat strength across all chord onsets. A lower CBS implies that chords often fall on strong or half-beats, while a higher CBS indicates more frequent off-beat or irregular chord placements (i.e., more syncopated rhythm).

3.2.4. Fréchet Audio Distance Evaluation

In addition to comparing generative results on melodic harmonization with the test set, the generated results are also compared with a set of pop songs but in terms of their audio rendering through the Fréchet Audio Distance (FAD). FAD, introduced by Kilgour et al. (2019) [

39], is an adaptation of the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) for audio evaluation. FAD compares the statistical distributions of embeddings extracted from real and generated audio samples, using pretrained models to capture perceptually relevant features. It serves as a reference-free metric that assesses overall audio realism, making it well-suited for evaluating generative music tasks where token-level accuracy may be insufficient. The metric assumes the embeddings follow multivariate Gaussian distributions, and the FAD score quantifies the distance between these distributions. A FAD score between two embedding distributions is computed by:

In this study, FAD is used to evaluate the quality of chord accompaniments generated for given melodies by GPT-2 and BART-based models. To compute validation scores, we extracted chunked audio embeddings for each model-tokenizer pair from both external (POP909 dataset [

40]) and internal reference sets, with all MIDI files transposed to C major or A minor. For external validation, embeddings were computed using 15-second chunks with a 7.5-second hop size; for internal validation, 5-second chunks with a 2.5-second hop size were used, ensuring 50% overlap in both cases. Embeddings were derived from the 4th layer of the pretrained

m-a-p/MERT-v1-95M model [

41], selected for its strong correlation with Music Quality (MQ) as demonstrated by Gui et al. [

42]. This choice ensures that the resulting representations capture musically relevant characteristics for quality assessment.

4. Results

This section presents the experimental findings. It begins with an analysis of training convergence and how it is influenced by the characteristics of each tokenizer. Subsequently, the performance of the models is evaluated on the test set using token-based, symbolic music, and audio-level metrics. These evaluations are conducted with respect to both ground-truth sequences and a broader corpus of pop music, providing insights into how different tokenization strategies affect the ability of transformer-based models to generate harmonizations that resemble real-world musical examples.

4.1. Training Analysis

The training analysis investigates the impact of each tokenizer on model learning behavior and representational efficiency. It includes an information-theoretic assessment of how effectively each tokenizer compresses harmonic content. Furthermore, the progression of model confidence over training epochs is examined to understand how certainty evolves with different tokenizations. The analysis also explores whether certain aspects of musical harmony—such as high-level structural patterns or local chord content—are more accurately learned depending on the tokenizer employed.

4.1.1. Information-Theoretic Considerations

Table 2 presents key statistics for the tokenizers, including vocabulary size and sequence compressibility. Tokenizers with larger vocabularies are associated with shorter average and maximum sequence lengths, which aligns with expectations. Larger vocabularies can encode higher-level or compound concepts, allowing them to express the same musical content using fewer tokens. In contrast, tokenizers with smaller, more atomic vocabularies generate longer sequences, as they require more tokens to represent the same information. This illustrates the trade-off between vocabulary granularity and sequence length in symbolic music representation.

The “Total Compression” column in

Table 2 reports the ratio of the compressed to uncompressed sizes of tokenized sequences, expressed in bytes, after converting sequences into streams of 64-bit token IDs. Compression is performed using the DEFLATE algorithm [

43], which combines the LZ77 algorithm [

44] and Huffman coding [

45]. As a byte-level compression method, DEFLATE is particularly effective at reducing redundancy in sequences with frequent symbol repetition. Lower compression ratios indicate higher redundancy, suggesting that the tokenized sequences contain more repeatable byte patterns that the algorithm can exploit.

While DEFLATE operates at the byte level, the “Hypothetical Compressed Length” column attempts to project the compressed length of each token sequence, calculated as the product of the original sequence length and the compression ratio. This value should be interpreted cautiously: it does not reflect meaningful compression in terms of token semantics or musical structure, but rather serves as an exploratory indicator of repetition at the byte-representation level. It highlights which tokenizations yield sequences that, when serialized, are more amenable to byte-level pattern substitution. For reference, values for the MelodyPitch tokenizer are included in the table, although no direct comparison is made with the harmony-focused tokenizers that are the main subject of this study.

From this perspective, one could imagine a symbolic compression strategy for the PitchClass tokenizer: recurring pitch class sequences could first be abstracted into chord symbols (as in the ChordSymbol tokenizer), and then subjected to standard byte-level compression. This two-step process would essentially replicate the ChordSymbol representation, suggesting that musically informed abstractions can serve as a kind of “semantic compression” based on domain expertise. However, it is important to recognize that this analogy should not be taken as a literal equivalence. Whereas DEFLATE operates serially and without context, music theory abstractions encode structural knowledge that may not always align with optimal byte-level redundancy.

Despite the improved compressibility of the ChordSymbol sequences, this does not imply that such tokenizations are inherently more suitable for training transformer models. Byte-level compressibility is not a direct measure of learnability or task effectiveness. In fact, overly compressed sequences may strip away low-level detail that could be useful for certain modeling objectives. Consequently, while compression analysis can provide insights into the redundancy and structure of tokenized sequences, its implications for model performance must be established with specific task-related metrics, which is performed in the reminder of this section.

4.1.2. Training Convergence Analysis

This section investigates how the choice of tokenization method influences model convergence and learning effectiveness. One direct metric for evaluating model performance is token-level accuracy, which reflects the proportion of correctly predicted tokens in the validation set – i.e., tokens assigned the highest probability given the context. However, token-level accuracy alone may not offer a complete picture due to inherent differences in vocabulary size and sequence length across tokenizers. Models using larger vocabularies face a more challenging prediction task at each step, whereas those using smaller vocabularies must process longer sequences, increasing cumulative error.

To provide a more balanced evaluation, two additional metrics are considered alongside accuracy. First, perplexity, which accounts for the model’s uncertainty normalized over sequence length, offers a measure of predictive confidence that is independent of absolute token count. Second, normalized token entropy provides a measure of distributional uncertainty adjusted for vocabulary size, allowing for fairer comparisons across models with differing output spaces. Together, these metrics help disentangle the effects of token vocabulary and sequence structure on learning dynamics.

Perplexity is computed for each tokenized sequence as follows:

where

N is the number of tokens in the sequence, and

denotes the probability assigned by the model to the correct token

given its context. Perplexity quantifies the model’s average uncertainty when predicting each token. A value of 1 indicates perfect certainty and correctness at every step, while a value of, for example, 4 implies that the model’s predictions are as uncertain as choosing uniformly among four equally likely options.

Normalized token entropy is computed for each sequence as:

where

is the vocabulary size and

is the model’s predicted probability of token

at position

i, given the context. This measure captures the average entropy of the model’s full predictive distribution across all positions, normalized by the maximum possible entropy

. A value of 0 indicates that the model is entirely confident in its predictions (assigning all probability mass to a single token), whereas a value of 1 suggests that the model is maximally uncertain

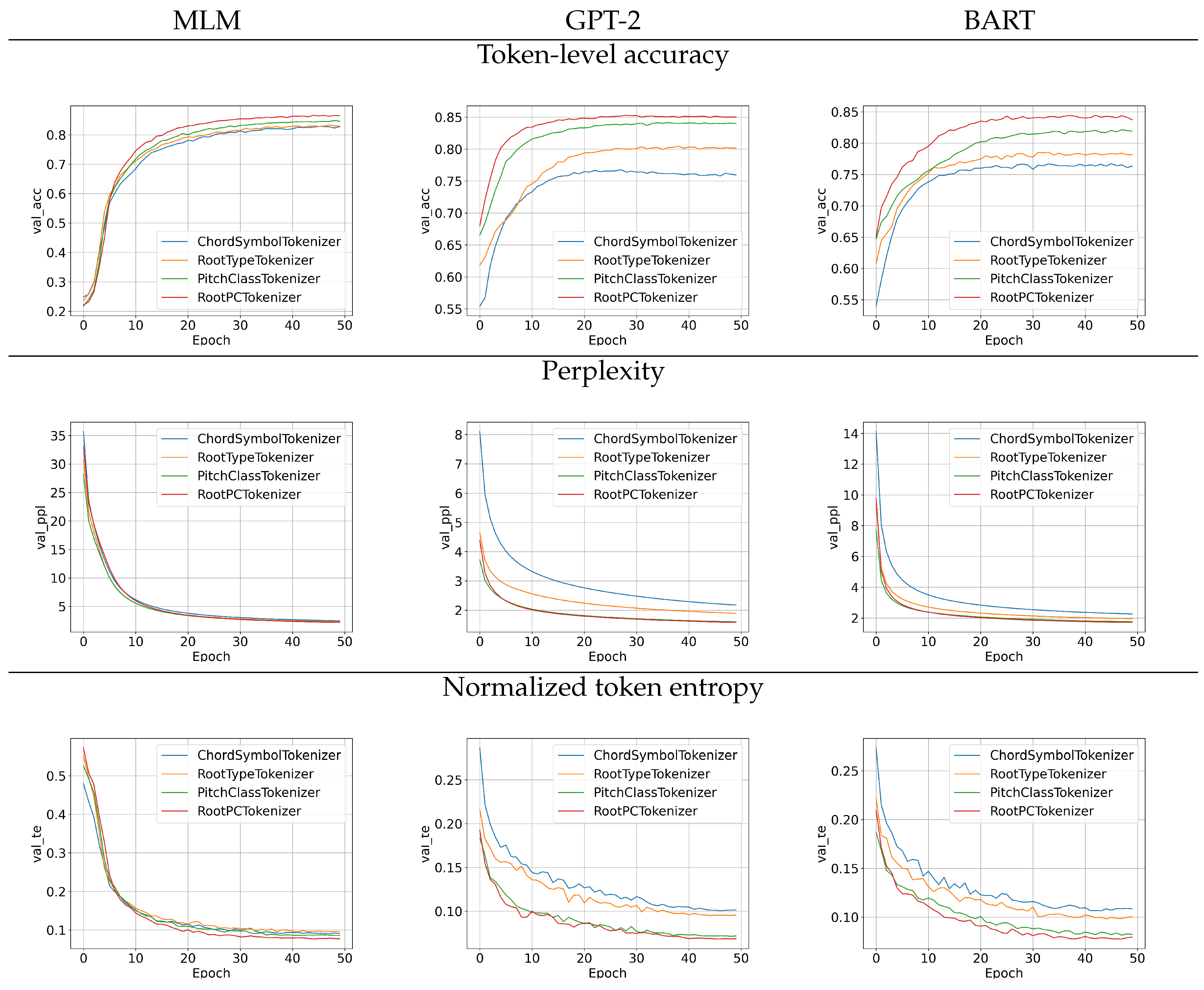

Figure 1 presents validation metrics across 50 training epochs for both the MLM and melodic harmonization tasks, using the GPT-2 and BART models. The figure is organized into three rows: the top row shows token-level accuracy, the middle row shows average model perplexity, and the bottom row displays normalized token entropy. All values are computed on the validation set. For token-level accuracy (top row), the MLM task measures the proportion of correctly predicted tokens among those that were masked during training. In the case of melodic harmonization with GPT-2 and BART, accuracy reflects the percentage of times the model assigns the highest probability to the correct next token, given the preceding context (which includes melody and/or harmony tokens, depending on the setup).

The perplexity and normalized entropy results (middle and bottom rows of

Figure 1) show how model certainty evolves during training. In particular, these metrics reveal that model confidence increases over time—as evidenced by decreasing perplexity and entropy – even as token-level accuracy begins to decline. This divergence indicates overfitting, where the model becomes increasingly confident but less generalizable. Across all visualizations, the spelling-based tokenizers (

PitchClass and

RootPC) exhibit higher accuracy and lower uncertainty than other tokenization schemes. These results suggest that such tokenizers enable the models to make more confident and correct predictions, independent of differences in sequence length or vocabulary size.

As a complement to the accuracy trends shown in

Figure 1,

Table 3 provides a detailed analysis of how prediction errors are distributed across different token types in the validation set. This breakdown is important because different tokenization methods may excel at different aspects of harmony modeling. For example, one method may be more accurate at predicting individual chord symbols, while another may be better at reconstructing complete chords. This distinction is particularly critical for chord “spelling” tokenizers, where a token-level accuracy of 50% does not necessarily imply that half of the chords were predicted correctly. It is possible that no chord was predicted in its entirety, and instead, every chord was partially predicted—resulting in zero full-chord accuracy.

To address this ambiguity, the full-chord structures for each tokenization method are extracted from the token-level predictions, and the accuracy of each structural component is evaluated separately as follows:

correct bar: The bar tokens are predicted correctly.

correct new chord: A position_X token is correctly placed, regardless of the specific position value. This indicates that the model correctly identified the onset of a new chord (rather than a new bar or additional pitch), irrespective of the precise timing.

correct position: The model correctly identifies both the presence and the timing of a new chord.

correct chord: The complete chord structure is accurately predicted. For the PitchClass tokenizer, which lacks root information, this refers to correctly predicting the full set of pitch classes that constitute the chord.

correct root: The root note of the chord is correctly predicted. This criterion is not applicable to the PitchClass tokenizer.

Table 3 primarily demonstrates that both generative models under evaluation (BART and GPT-2) exhibit similar accuracy profiles across tokenizers when predicting the next token. Structural elements – such as bar delimiters, new chord onsets, and chord positions – are predicted with higher accuracy (ranging from 85% to 93%) than harmonic content, namely chord identities and root notes (ranging from 53% to 65%). This suggests that, regardless of the tokenizer, models consistently struggle with the fine-grained prediction of chord content in the validation set—an outcome that aligns with the general difficulty of melody harmonization, even for human musicians working with unfamiliar material.

Another notable observation from

Table 3 is that the higher overall accuracy of the spelling-based tokenizers (as shown in the top row of

Figure 1) does not translate into superior performance on any specific chord-related component. Although these tokenizers achieve higher total accuracy – approximately 85% compared to below 80% for others – they do not consistently outperform alternative tokenizers on individual aspects such as chord onset or root prediction. In fact, they are significantly outperformed in predicting new bar tokens. This pattern indicates that the improved token-level accuracy of spelling tokenizers stems primarily from their ability to partially match the pitch-class content of chords, without necessarily capturing the chord as a coherent unit. The relatively poor performance on bar prediction further suggests that these tokenizers may overpredict chord extensions (i.e., additional pitch classes), rather than signaling the conclusion of harmonic segments.

4.2. Melodic Harmonization Generation Results

To evaluate autoregressively generated melodic harmonizations, the melody lines from the test set (1,520 pieces) were used as input prompts for the models. Harmonies were generated using beam search with five beams. Sampling-based strategies, including those incorporating various temperature values, were also explored; however, they produced inconsistent results across multiple runs under identical configurations. To ensure reproducibility and assess near-optimal model behavior under controlled conditions, a greedy decoding approach was adopted. The goal of this study is to analyze the idealized behavior of the models in relation to the choice of tokenizer; thus, investigating stylistic variation due to different sampling temperatures lies beyond the scope of this work.

4.2.1. Token and Symbolic Music Metrics

In the

token-based evaluation, the results presented in

Table 4 reveal a strong correlation between

vocabulary size and

syntactic reliability. The

ChordSymbol tokenizer, with its large vocabulary encompassing several hundred distinct chord labels, exhibits the lowest Token Consistency Ratio (TCR)—96.2 % with BART and 98.0 % with GPT-2—alongside the highest Duplicate Ratio (DR ≈ 0.02). In contrast, the compact tokenizers

PitchClass and

RootPC, which use minimal vocabularies, achieve near-perfect syntactic validity (TCR ≥ 99.5 %) and eliminate redundant tokens entirely (DR = 0.00). The

RootType tokenizer occupies a middle ground, maintaining a TCR above 98.8 % and a DR of 0.03 or lower. These results suggest that a moderately sized vocabulary, combined with shorter token sequences, can support both syntactic integrity and compact representation. At the model level, GPT-2 generally outperforms BART in TCR for all tokenizers except

PitchClass, where BART occasionally generates spurious

<bar> tokens.

On the other hand,

Table 5 paints a more nuanced picture than the purely syntactic analysis.

Chord-related metrics (CHE, CC, CTD) favour the larger–vocabulary encodings:

RootType attains the highest entropy and coverage, while

ChordSymbol yields the smoothest step-to-step motion (CTD) compared to the ground-truth profile. Across all four tokenizers, BART model scores consistently higher than GPT-2 on these three metrics, suggesting that its architecture with an encoder capturing the conditional melody sequence contributes better at capturing long-range harmonic context even if it occasionally sacrifices syntactic neatness.

Table 5 offers a more nuanced perspective, shifting the focus from syntactic to musical relevance.

Chord-related metrics – including Chord Histogram Entropy (CHE), Chord Coverage (CC), and Chord Transition Distance (CTD) – favor tokenizers with richer chord-level vocabularies.

RootType achieves the highest CHE and CC, while

ChordSymbol leads in CTD, producing smoother harmonic progressions when compared to the ground-truth sequences. Notably, BART consistently surpasses GPT-2 across all three metrics, suggesting that its encoder-decoder architecture more effectively captures long-range harmonic dependencies, even if this occasionally comes at the expense of syntactic precision.

When examining chord–melody harmonicity, differences across tokenizers narrow considerably. The PitchClass tokenizer paired with GPT-2 achieves the highest scores across all three harmonic alignment metrics—CTnCTR, PCS, and MCTD. By explicitly encoding each chord as a set of pitch classes, this tokenizer provides GPT-2 with rich local harmonic context, enhancing its ability to select notes that support the melody. BART exhibits relatively stable performance across all tokenizers in these metrics, with the exception of the ChordSymbol tokenizer when used with GPT-2, which consistently yields the weakest results.

In terms of harmonic rhythm, the most effective configuration is the PitchClass tokenizer combined with BART. Despite producing longer sequences, this tokenizer’s smaller vocabulary concentrates the model’s learning capacity on a limited set of shared positional tokens. BART’s encoder-decoder structure further capitalizes on this by placing chords more uniformly within bars – evidenced by higher HRHE and HRC values – while also reducing clutter from off-beat placements (lower CBS). Nonetheless, all model–tokenizer combinations still fall short of matching the rhythmic profile of ground-truth harmonizations, indicating an opportunity for further refinement in modeling stylistically authentic harmonic rhythm.

In summary, no single tokenizer excels across all nine music-based evaluation metrics. RootType and ChordSymbol tokenizers generate the most structurally plausible chord progressions; PitchClass offers superior melodic support – especially with GPT-2 – and yields the most natural chord placements when paired with BART. The RootPC tokenizer also performs competitively across several dimensions. The next evaluation section complements these objective findings with perceptual metrics derived from audio-based FAD scores, offering a broader view of how tokenization impacts musical quality in end-to-end generation.

4.2.2. FAD Results

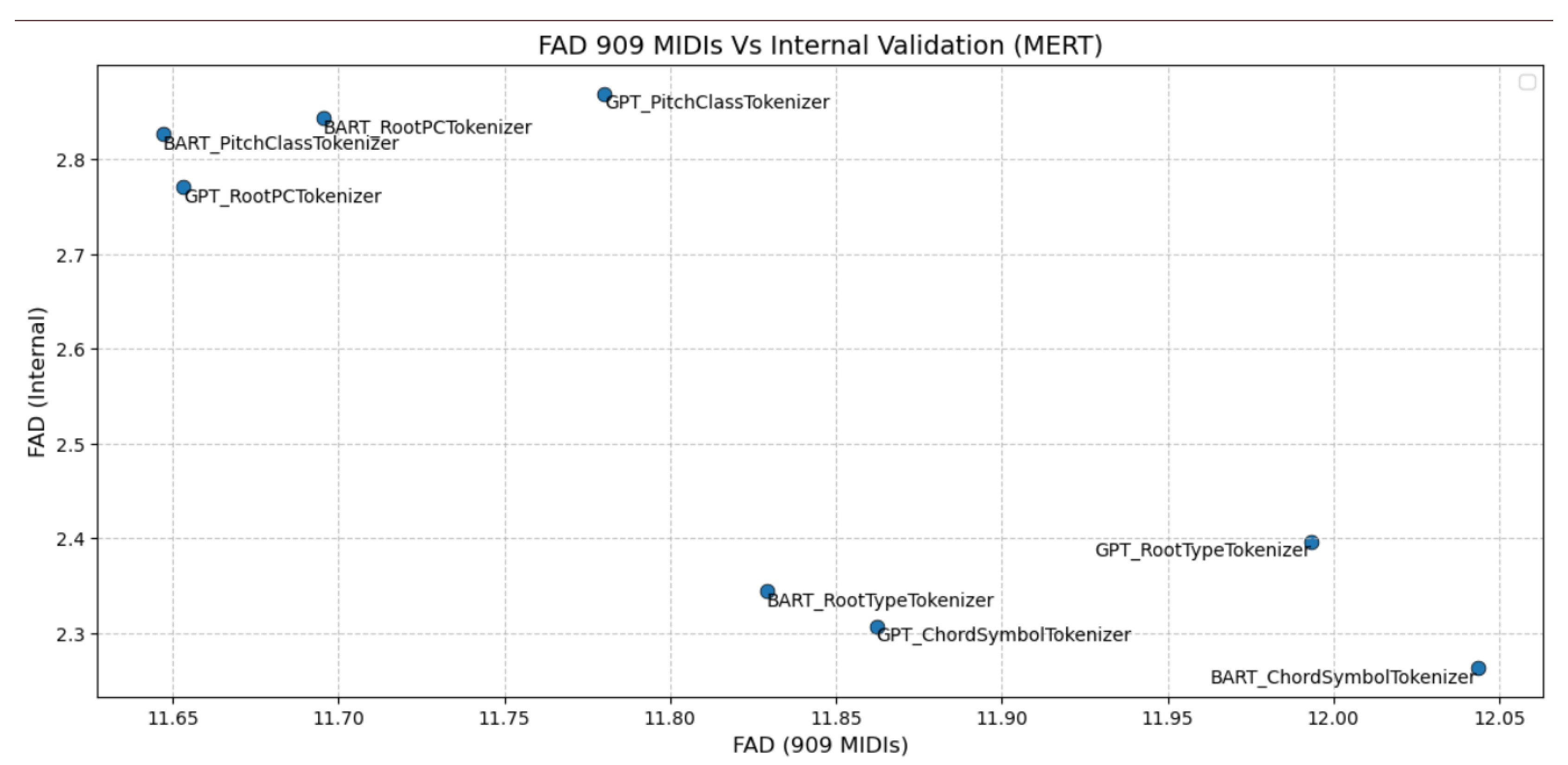

With respect to Fréchet Audio Distance (FAD), models using the PitchClass and RootPC tokenizations achieved slightly lower external FAD scores, indicating closer alignment with the distribution of the unseen reference corpus (i.e., more stylistically similar to generic pop music). However, these same models yielded higher internal FAD values, suggesting weaker consistency with the ground-truth harmonizations from the test set. In contrast, models trained with the ChordSymbol and RootType tokenizations exhibited lower internal FAD, reflecting stronger preservation of structured harmonic relationships present in the training data, albeit at the expense of slightly higher external FAD scores.

This trade-off reflects fundamental differences in representational focus. The

ChordSymbol and

RootType tokenizations explicitly encode chordal structure – such as roots and functional types – thereby imposing stronger internal harmonic regularity. In contrast, the

PitchClass and

RootPC tokenizations emphasize pitch-centric groupings, offering greater representational flexibility that facilitates generalization across diverse musical contexts but may dilute harmonic specificity. This balance between structural precision and expressive breadth is illustrated in

Figure 2. Since the FAD embeddings were computed over temporal audio segments using a pretrained musical model, we treat external FAD as a reliable proxy for a model’s ability to generalize stylistically. However, it primarily captures global distributional similarity rather than detailed musical coherence.

Notably, GPT-2 models tend to exhibit slightly higher external FAD values compared to BART models within each tokenizer group, suggesting an architectural influence on stylistic generalization. Still, tokenizer design remains the primary driver of both internal harmonic consistency and external stylistic alignment. Overall, the differences in FAD scores across models and tokenizations are moderate, indicating that all configurations produce harmonizations that are broadly coherent both within and beyond the distribution of the training data.

Table 6.

FAD scores per model-tokenizer combination using MERT embeddings.

Table 6.

FAD scores per model-tokenizer combination using MERT embeddings.

| Model + Tokenizer |

FAD (909, MERT) |

FAD (internal, MERT) |

| BART_PitchClassTokenizer |

11.6472 |

2.8262 |

| BART_RootPCTokenizer |

11.6954 |

2.8432 |

| BART_RootTypeTokenizer |

11.8291 |

2.3438 |

| BART_ChordSymbolTokenizer |

12.0435 |

2.2630 |

| GPT_PitchClassTokenizer |

11.7803 |

2.8694 |

| GPT_RootPCTokenizer |

11.6531 |

2.7705 |

| GPT_RootTypeTokenizer |

11.9934 |

2.3962 |

| GPT_ChordSymbolTokenizer |

11.8622 |

2.3069 |

5. Conclusions

This paper examines various approaches to symbolic music harmony tokenization for basic tasks handled by transformer models, specifically masked language modeling (MLM) and melodic harmonization generation. Four tokenization methods are tested, each differing in the level of detail used to represent chord content: ChordSymbol treats chord symbols as standalone tokens; RootType splits the chord into two separate tokens for the root and the type/quality; PitchClass uses the individual pitch classes that comprise each chord as tokens; and RootPC assigns a separate token to the pitch class corresponding to the chord’s root. A dataset of over 17,000 lead sheet music charts was collected, and a RoBERTa model was trained and evaluated for MLM-related tasks, while GPT-2 and BART models were trained and tested for harmony generation based on a given melody.

The results show that tokenizers employing chord spelling (i.e., describing chords as sequences of pitch-class tokens) achieve higher validation accuracy and demonstrate greater confidence in their predictions (as indicated by lower perplexity and normalized token entropy) across all tasks. Furthermore, although all methods result in a relatively low percentage of token-related errors—such as duplication and inconsistency—the chord spelling approaches consistently produce fewer errors.

In the context of melodic harmonization generation, each tokenization method exhibits distinct strengths and weaknesses. For music-based metrics related solely to chord properties (independent of the melody), the “chunkier” tokenizations – those that encode more chord information per token – tend to produce chord sequences that are more similar to the ground truth. In contrast, for metrics assessing melody-harmony relations and harmonic rhythm (i.e., structural aspects), the spelling-based tokenizers better reflect characteristics of the original data, likely due to their smaller vocabularies preserving more model capacity for learning positional patterns. Finally, an analysis of audio renderings of the generated symbolic harmonizations reveals a tendency for spelling-based methods to reflect the stylistic characteristics of more generic pop music, while chunkier tokenizers produce audio renderings more consistent with the dataset.

This study suggests that there is no universally superior tokenization strategy for symbolic music harmony. In general-purpose applications, any of the tested approaches can yield strong results. However, specialized tasks may benefit from tailored strategies. For example, in harmony classification – where inter-chord relationships are crucial – chunkier tokenizations may have an edge, as they retain more nuanced information across chord sequences. Conversely, in generative style transfer applications, spelling-based methods may be advantageous, as they allow the generated harmony to be more responsive to melodic detail and more exploratory in chord progression. Future work focusing on specific use cases could provide deeper insights into the distinct effects and potential advantages of the tokenization methods explored here.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M. Kaliakatsos-Papakostas and E. Cambouropoulos, V. Katsouros; methodology, M. Kaliakatsos-Papakostas, D. Makris, K. Soiledis, K.-T. Tsamis; software, M. Kaliakatsos-Papakostas, D. Makris, K. Soiledis; validation, D. Makris, K.-T. Tsamis.; formal analysis, D. Makris, K. Soiledis, K.T. Tsamis; resources, V. Katsouros, M. Kaliakatsos-Papakostas; data curation, D. Makris, K.-T. Tsamis; writing—original draft preparation, M. Kaliakatsos-Papakostas; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, M. Kaliakatsos-Papakostas. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used are subject to copyright and may become available upon request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT for the purposes of text refinement. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sennrich, R.; Haddow, B.; Birch, A. Neural machine translation of rare words with subword units. arXiv preprint arXiv:1508.07909 2015.

- Kudo, T.; Richardson, J. Sentencepiece: A simple and language independent subword tokenizer and detokenizer for neural text processing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.06226 2018.

- Raffel, C.; Shazeer, N.; Roberts, A.; Lee, K.; Narang, S.; Matena, M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, W.; Liu, P.J. Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of machine learning research 2020, 21, 1–67.

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901.

- Kaplan, J.; McCandlish, S.; Henighan, T.; Brown, T.B.; Chess, B.; Child, R.; Gray, S.; Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D. Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361 2020.

- Agosti, G. Transformer networks for the modelling of jazz harmony. Master’s thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy, 2021.

- Hahn, S.; Yin, J.; Zhu, R.; Xu, W.; Jiang, Y.; Mak, S.; Rudin, C. SentHYMNent: An Interpretable and Sentiment-Driven Model for Algorithmic Melody Harmonization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2024, pp. 5050–5060.

- Cambouropoulos, E.; Kaliakatsos-Papakostas, M.A.; Tsougras, C. An idiom-independent representation of chords for computational music analysis and generation. In Proceedings of the Joint 40th International Computer Music Conference (ICMC) and 11th Sound and Music Computing (SMC) Conference (ICMC-SMC2014), 2014.

- Kaliakatsos-Papakostas, M.; Katsiavalos, A.; Tsougras, C.; Cambouropoulos, E. Harmony in the polyphonic songs of epirus: Representation, statistical analysis and generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 4th international workshop on folk music analysis, 2014, pp. 21–28.

- Kaliakatsos-Papakostas, M.A.; Zacharakis, A.I.; Tsougras, C.; Cambouropoulos, E. Evaluating the General Chord Type Representation in Tonal Music and Organising GCT Chord Labels in Functional Chord Categories. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Society for Music Information Retrieval (ISMIR) Conference, 2015, pp. 427–433.

- Costa, L.F.; Barchi, T.M.; de Morais, E.F.; Coca, A.E.; Schemberger, E.E.; Martins, M.S.; Siqueira, H.V. Neural networks and ensemble based architectures to automatic musical harmonization: a performance comparison. Applied Artificial Intelligence 2023, 37, 2185849.

- Yeh, Y.C.; Hsiao, W.Y.; Fukayama, S.; Kitahara, T.; Genchel, B.; Liu, H.M.; Dong, H.W.; Chen, Y.; Leong, T.; Yang, Y.H. Automatic melody harmonization with triad chords: A comparative study. Journal of New Music Research 2021, 50, 37–51.

- Chen, Y.W.; Lee, H.S.; Chen, Y.H.; Wang, H.M. SurpriseNet: Melody harmonization conditioning on user-controlled surprise contours. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.00378 2021.

- Sun, C.E.; Chen, Y.W.; Lee, H.S.; Chen, Y.H.; Wang, H.M. Melody harmonization using orderless NADE, chord balancing, and blocked Gibbs sampling. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2021, pp. 4145–4149.

- Zeng, T.; Lau, F.C. Automatic melody harmonization via reinforcement learning by exploring structured representations for melody sequences. Electronics 2021, 10, 2469.

- Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Sun, M. Generating chord progression from melody with flexible harmonic rhythm and controllable harmonic density. EURASIP Journal on Audio, Speech, and Music Processing 2024, 2024, 4.

- Wu, S.; Li, X.; Sun, M. Chord-conditioned melody harmonization with controllable harmonicity. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Yi, L.; Hu, H.; Zhao, J.; Xia, G. Accomontage2: A complete harmonization and accompaniment arrangement system. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.00353 2022.

- Rhyu, S.; Choi, H.; Kim, S.; Lee, K. Translating melody to chord: Structured and flexible harmonization of melody with transformer. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 28261–28273.

- Zhou, J.; Zhu, H.; Wang, X. Choir Transformer: Generating Polyphonic Music with Relative Attention on Transformer (2023).

- Huang, J.; Yang, Y.H. Emotion-driven melody harmonization via melodic variation and functional representation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.20176 2024.

- Wu, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, F.; Sun, M. Melodyt5: A unified score-to-score transformer for symbolic music processing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.02277 2024.

- Cholakov, V. AI Enhancer—Harmonizing Melodies of Popular Songs with Sequence-to-Sequence. Master’s thesis, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland, 2018.

- Huang, C.Z.A.; Vaswani, A.; Uszkoreit, J.; Shazeer, N.; Simon, I.; Hawthorne, C.; Dai, A.M.; Hoffman, M.D.; Dinculescu, M.; Eck, D. Music Transformer, 2018, [arXiv:cs.LG/1809.04281].

- Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, G. Learning interpretable representation for controllable polyphonic music generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2008.07122 2020.

- Min, L.; Jiang, J.; Xia, G.; Zhao, J. Polyffusion: A diffusion model for polyphonic score generation with internal and external controls. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.10304 2023.

- Ji, S.; Yang, X.; Luo, J.; Li, J. Rl-chord: Clstm-based melody harmonization using deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2023.

- Lim, H.; Rhyu, S.; Lee, K. Chord generation from symbolic melody using BLSTM networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.01011 2017.

- Ji, S.; Yang, X. Emotion-conditioned melody harmonization with hierarchical variational autoencoder. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 228–233.

- Raffel, C.; McFee, B.; Humphrey, E.J.; Salamon, J.; Nieto, O.; Liang, D.; Ellis, D.P.; Raffel, C.C. MIR_EVAL: A Transparent Implementation of Common MIR Metrics. In Proceedings of the ISMIR, 2014, Vol. 10, p. 2014.

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. Roberta: A robustly optimized bert pretraining approach. arXiv preprint arXiv:1907.11692 2019.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2019 conference of the North American chapter of the association for computational linguistics: human language technologies, volume 1 (long and short papers), 2019, pp. 4171–4186.

- Lewis, M.; Liu, Y.; Goyal, N.; Ghazvininejad, M.; Mohamed, A.; Levy, O.; Stoyanov, V.; Zettlemoyer, L. Bart: Denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.13461 2019.

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Child, R.; Luan, D.; Amodei, D.; Sutskever, I.; et al. Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 2019, 1, 9.

- Krumhansl, C.L. Cognitive foundations of musical pitch; Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Fradet, N.; Gutowski, N.; Chhel, F.; Briot, J.P. Byte pair encoding for symbolic music. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.11975 2023.

- Snover, M.; Dorr, B.; Schwartz, R.; Micciulla, L.; Makhoul, J. A study of translation edit rate with targeted human annotation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 7th Conference of the Association for Machine Translation in the Americas: Technical Papers, 2006, pp. 223–231.

- Harte, C.; Sandler, M.; Gasser, M. Detecting harmonic change in musical audio. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 1st ACM workshop on Audio and music computing multimedia, 2006, pp. 21–26.

- Kilgour, K.; Zuluaga, M.B.; Roblek, D.; Sharifi, M. Fréchet Audio Distance: A Reference-Free Metric for Evaluating Music Enhancement Algorithms. In Proceedings of the Interspeech 2019, 2019, pp. 2350–2354. [CrossRef]

- Wang*, Z.; Chen*, K.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, M.; Dai, S.; Bin, G.; Xia, G. POP909: A Pop-song Dataset for Music Arrangement Generation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of 21st International Conference on Music Information Retrieval, ISMIR, 2020.

- Li, Y.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Y.; Chen, X.; Yin, H.; Lin, C.; Ragni, A.; Benetos, E.; Gyenge, N.; et al. MERT: Acoustic Music Understanding Model with Large-Scale Self-supervised Training, 2023, [arXiv:cs.SD/2306.00107].

- Gui, A.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, Y. Adapting Fréchet Audio Distance for Generative Music Evaluation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2024 - 2024 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2024, pp. 1331–1335. [CrossRef]

- Deutsch, P. Rfc1951: Deflate compressed data format specification version 1.3, 1996.

- Ziv, J.; Lempel, A. A universal algorithm for sequential data compression. IEEE Transactions on information theory 1977, 23, 337–343.

- Huffman, D.A. A method for the construction of minimum-redundancy codes. Proceedings of the IRE 1952, 40, 1098–1101.

| 1 |

This is equivalent to transposing all pieces to C major or C minor. |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

The beat subdivisions used are: {0, 0.16, 0.25, 0.33, 0.5, 0.66, 0.75, 0.83}. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).