1. Introduction

Audio transformation deals with the transformation of syntactic, acoustic, and semantic variations of one audio to another. It includes multiple applications such as voice conversion, timbre transfer, speaker morphing, emotion transformation, etc [

1]. One of the most widely studied applications of it is Voice Conversion (VC). Voice conversion deals with the transformation of paralinguistic features of the source audio with that of the target while preserving the linguistic features.

Most of the early VC approaches have focused upon statistical methods based on Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) to convert voice from source to target speaker[

2,

3]. It has also been approached with feed-forward Deep Neural Networks [

4] and an exemplar-based framework using non-negative matrix factorization[

5,

6]. Despite producing good results, these approaches often used complex feature pipelines consisting of domain-specific features and require parallel time-aligned source and target speech data, which is difficult and expensive to collect.

Recently there have been some approaches such as [

7,

8,

9] that overcome the requirement for parallel time-aligned data by using an attribute label along with the acoustic features to perform local conditioning to convert an attribute of source speech (e.g., speaker identity) to target attribute. In general, though the quality of the converted audio obtained with non-parallel methods is usually limited compared with that of audio obtained through statistical methods using parallel data, these can eliminate the need for parallel data which is costly to obtain. However, these approaches still suffer from the limitation of being training vocabulary dependent. These approaches because of the use of local conditioning mechanisms can only convert the voice to a target speaker which was present during the training phase.

There have been some attempts such as [

10,

11] which overcome the aforementioned limitation and perform voice conversion for any arbitrary speaker. These approaches use automatic speech recognition (ASR) systems to convert the input source speech to intermediate phonetic representations which are further synthesized as output target speech using text-to-speech systems. Although these systems can perform any-to-any voice conversion, they have some downsides to offer such as the performance of such methods is heavily dependent upon the accuracy of the ASR system used. Secondly, these approaches rely on intermediate phonetic transcriptions to train or finetune the ASR system used which are usually hard to obtain, thus decreasing the portability of such systems to newer languages or datasets[

12]. Lastly, these systems are primarily applicable only to the application of voice conversion.

Previous study [

13] uses pseudo-recurrent structures like self-attention models and quasi recurrent neural networks to build text-to-speech acoustic models, achieving a 11.2 times synthesis speedup on CPU and 3.3 times on GPU compared to the purely recurrent baseline model. It also preserves synthetic speech quality to the same level as the original recurrent model, competitive with state-of-the-art vocoder-based statistical parametric speech synthesis models. Another study [

14] presents a network that is trained end-to-end, learning to map speech spectrograms into target spectrograms in another language, corresponding to the translated content (in a different canonical voice). The study addresses the task of speech-to-speech translation (S2ST), which is highly beneficial for breaking down communication barriers between people who do not share a common language.

Despite their exceptional performance in prediction, machine learning models, as ‘black boxes’, encounter significant challenges in interpretability and transparency[

15]. The reliability of the predictive results of machine learning models is questionable due to the lack of a physical explanation for their learning processes and operational principles [

16]. Interpretability refers to the extent to which the behavior and decision-making process of machine learning models and algorithms can be understood and explained by humans [

17]. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) aims to enhance understanding of nonlinear machine learning models through two approaches: intrinsic and post-hoc explainability [

18].

To analyze the explainability of LSTMs, a research [

19] studies n-gram models to conclude that LSTMs’ performance improves on characters that require long-range reasoning. Another study [

20] suggested a novel interpretation framework inspired by computation theory. In [

21], the authors develop an inherently interpretable RNN, SISTA-RNN, based on the sequential iterative soft-thresholding algorithm and the idea of deep unfolding [

22]. Researchers [

23] proposed a new explainable convolutional neural network (XCNN) in an end-to-end network architecture. Another study [

24] investigates the possibility of using fine-grained information to help explain the decision made by an encoder-decoder network using CNNs and LSTMs.

Controversy has accompanied attention mechanisms since their introduction. While some attention weights can provide reliable explanations [

25]; some researchers showed that attention distributions are not easily interpretable and require further processing [

26,

27]. In an attempt to investigate these controversies, a study [

28] manually analyzed attention mechanisms on several NLP tasks. The experiments showed that attention weights are interpretable indeed and are correlated with feature importance measures capturing several linguistic notions. These methods, however, are specific to particular domains and linguistic notions and might not be easily extendable to higher-level knowledge structures.

In this paper, we address some of the limitations mentioned above and propose a fully differentiable end-to-end audio transformation network which does not require parallel time-aligned data, is training vocabulary agnostic and achieves one-shot audio transforms without using any intermediate phonetic representations or ASR systems. Our method operates on acoustic features such as spectrograms or mel-frequency cepstral coefficients and does not require any domain-specific complex feature pipelines. We evaluate our method on two audio transformation tasks: (a) voice conversion and (b) musical style transfer, and compare the performance of our method with three existing approaches.

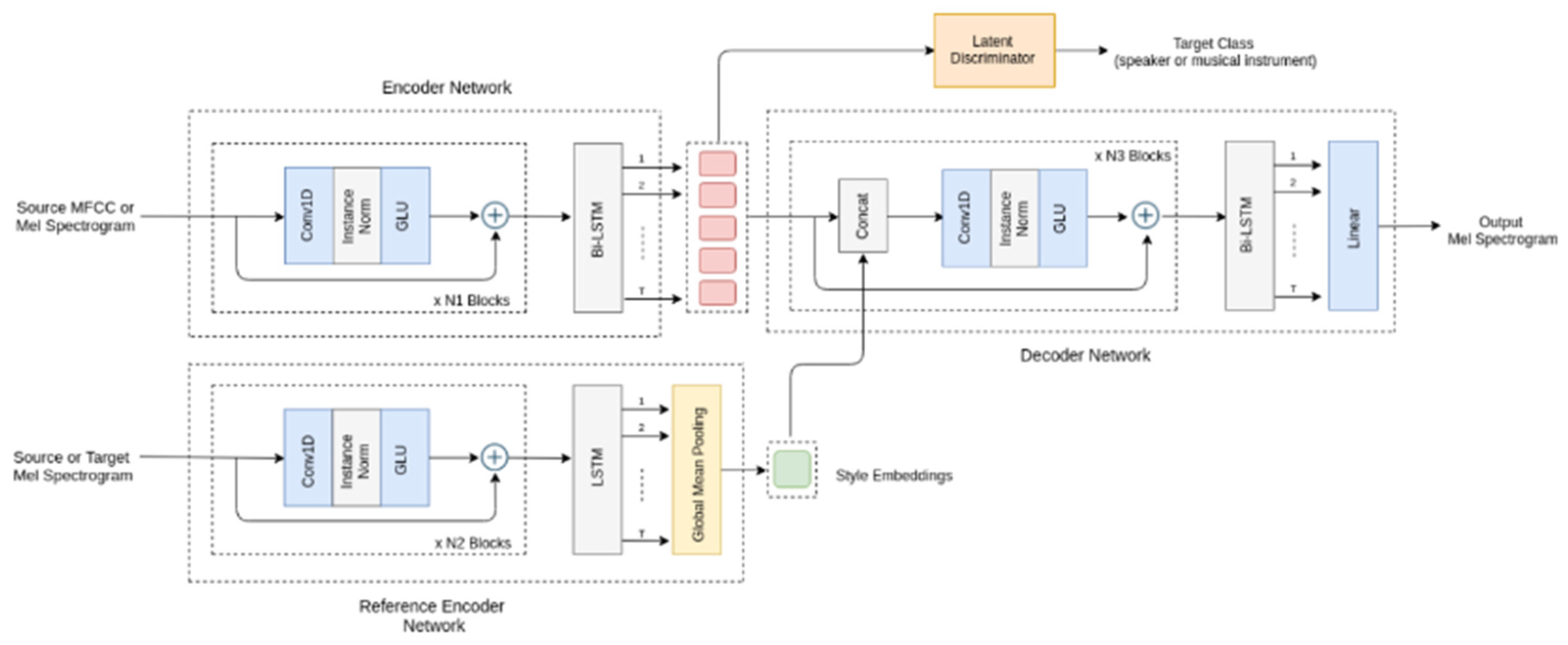

2. Method

We use an encoder-decoder based architecture along with a reference encoder to reconstruct the input acoustic feature sequence during the training phase and perform audio style transform by conditioning the input source audio sequence with the target-specific style embeddings computed from the reference encoder during the testing phase. We also employ a GAN based fine tuning scheme similar to [

29], to get rid of any noisy artifacts and improve upon the naturalness of the generated audio. The network architecture for our method is shown in

Figure 1 and explained below.

2.1. Encoder/Decoder Networks

We use a combination of one-dimensional (1D) convolutional layers with gated linear unit [

30] and bidirectional LSTMs[

31] to design the encoder and the decoder networks. The gated convolutional layers capture the spectral relationship among the input acoustic features sequences while preserving the temporal characteristics. The bidirectional LSTMs, on the other hand, model the temporal characteristics of those acoustic sequences. Inspired by recent works [

32,

33], we also include residual connections and instance normalization in both the encoder and decoder networks. These inclusions help in stabilizing the training process and the generation of high-resolution output audio sequences.

2.2. Reference Encoder

To remove the training vocabulary dependence and the requirement for intermediate phonetic representations, we train a reference encoder jointly with our encoder-decoder networks. The reference encoder is trained to capture target specific style embeddings, where target corresponds to a speaker or a musical instrument in our case.

The reference encoder is designed similar to the encoder network, with the main difference being the use of unidirectional LSTMs instead of bidirectional LSTMs. We also add a global mean pooling layer on top of the unidirectional LSTMs to capture the global style specific features from the input audio while ignoring the local phonetic specific features. The global mean pooling layer ensures that the learned style embeddings are independent of local features such as phonetic content.

Before training the reference encoder jointly with the encoder-decoder network, we first pre-train it on a simple classification task to predict the target audio class from the input acoustic feature sequences. This pre-training ensures that the reference encoder can learn a mapping from the global style specific features of the input audio sequence to a fixed length vector, which we denote as audio style embeddings. These style embeddings are then further fine tuned by jointly training the reference encoder with the encoder-decoder networks. These target specific style embeddings provide global conditioning and help in transforming the audio from source to target class.

2.3. Training Process

During the training phase, we use the acoustic features of the ground truth audio, i.e., Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients and Mel Spectrograms, as input to the encoder and the reference encoder networks. The reference encoder compresses the input acoustic features into a fixed-length vector, style embeddings. These style embeddings are concatenated along with the latent representation obtained from the encoder network and are fed to the decoder to reconstruct the input acoustic features of the input audio sequence.

We use a combination of Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Pearson Correlation Coefficient r

yy′ as our reconstruction loss function as given in (1). The value of r

yy′ ranges from −1 to 1, with 1 being a perfect correlation. Since we want to maximize r

yy′, we, therefore, minimize the negative of it.

2.4. Latent Discriminator

We employ a latent discriminator based adversarial training scheme to ensure that the encoder learns target class independent latent representations. We use an auxiliary classifier as our discriminator, to predict the target class from the encoded representation of an input audio utterance. The objective of the latent discriminator is to minimize the negative log-likelihood of the target class, while on the other hand, the encoder aims to fool the discriminator by maximizing the negative log-likelihood of the target class. Equation (2) and (3) gives the loss functions that both the discriminator and encoder try to optimize.

We devise the latent discriminator using a bank of gated convolutional layers along with instance normalization and dropout layers. The discriminator takes the encoded latent representations of an acoustic feature sequence as input and predicts the probability distribution over the target class. This latent discriminator based adversarial training scheme is essential since it enforces a regularization over the encoded latent representations and ensures that the learned representations are target class independent.

2.5. WGAN Based Fine Tuning

We also apply an adversarial based fine tuning scheme to remove any noisy artifacts and buzzy sound effects present in the generated audio and to improve upon its naturalness. Since GAN is notoriously hard to train, we use a variant of it, WGAN with gradient penalty[

34], which is relatively stable to train and easy to converge. We use the decoder of our network as the generator in this fine-tuning scheme. For the discriminator, we devise it using a bank of two dimensional (2D) convolutional layers to distinguish a real input acoustic feature sequence from one generated by our model. The output of the discriminator network is a scalar indicating how real an input feature sequence

x is, the larger the scalar value; the more real is

x. The discriminator is trained to maximize the adversarial loss, while on the other hand the generator is trained to fool the discriminator by minimizing both the adversarial and the reconstruction loss.

2.6. Process of Conversion

During the inference phase, audio transformation can be achieved by feeding the acoustic features of the target audio whose style is to be transferred as an input to the reference encoder while feeding the acoustic features of the source audio as input to the base encoder. The output from the decoder is the transformed audio sequence with local phonetic specific features from the source audio and global style specific features from the target audio respectively.

3. Experiments

3.1. Datasets

We evaluate our method on two audio transformation tasks: voice conversion and musical style transfer. For voice conversion, we use two datasets, CMU Arctic[

35] and L2 Arctic[

36]. The CMU Arctic consists of around 1150 utterances spoken by seven speakers from US English accents as well as other accents. The L2 Arctic is an extension to the CMU Arctic, which consists of recordings from twenty non-native speakers of English whose first languages (L1s) are Hindi, Korean, Mandarin, Spanish, and Arabic. Each speaker speaks the same set of utterances that were recorded in the CMU Arctic dataset. For musical style transfer, we use the IRMAS dataset[

37]. It consists of musical audio excerpts of ten different musical instruments, such as cello, acoustic guitar, piano, etc. We select a subset of 12 speakers, six females and six males, across six different nationalities, i.e., English, Hindi, Korean, Mandarin, Spanish, and Arabic respectively for voice conversion task. While for musical style transfer, we select a subset of 6 musical instruments, namely piano, saxophone, violin, flute, trumpet, and acoustic guitar respectively. The dataset is randomly split into training and testing sets in a 5:1 split ratio for each task.

3.2. Audio Formats

We use Mel-frequency cepstral coefficients (MFCCs) and Mel spectrograms in case of voice conversion and Mel spectrograms for musical style transfer as the input acoustic features. All the acoustic features are computed using the parameters given in

Table 1. Audio is synthesized from the predicted Mel spectrograms using Griffin-Lim algorithm [

38].

3.3. Training Details

We train the network using Adam optimizer with learning rate lr = 0.001, β1 = 0.9, β2 = 0.999 and with a batch size of 32. The network is trained for 100 epochs with a 30 epoch pre-training for the reference encoder. Finally, a 20 epoch GAN based fine tuning is performed.

3.4. Baselines

We compare the performance of our method with three different baselines. First two baselines are conditional variational autoencoder (CVAE)[

8] and conditional sequence-to-sequence network (CSeq2Seq)[

39], which use a local conditioning mechanism to perform audio transforms. The third baseline is an any-to-any voice conversion network proposed in [

10] which uses an SI-ASR system to compute intermediate phonetic transcriptions for performing audio transforms.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of our method with the baselines, we compute the mean opinion score (MOS), the higher, the better. We compute the score for both seen (speakers or musical instruments present in the training set) and unseen (speakers or musical instruments not present in the training set) targets. In addition to MOS, for the voice conversion task, we also evaluate the naturalness of the generated audio for four cases:

Intra-Gender voice conversions.

Inter-Gender voice conversions.

Intra-Nationality voice conversions.

Inter-Nationality voice conversions.

4. Results and Discussion

In

Table 2, we report the subjective evaluations (MOS) of all the baselines and our method for both the tasks. To compute the mean opinion score, we follow the standard procedure of rating the audio generated by our method and the baselines on a 5-point numeric scale: 1. bad, 2. poor, 3. fair, 4. good, and 5. excellent. Audios generated for all the experiments were rated by five normal-hearing human raters.

The results show that our method performs better than the conditional baselines for seen target identity and performs competitively well with the third baseline for both seen and unseen target identity. Though the third baseline, which uses an intermediate ASR system to do audio transformation, performs better than our method, it has some major disadvantages to offer such as lack of portability to a newer set because of the requirement for intermediate phonetic transcriptions which are usually costly to obtain. Our method, on the other hand, relies only on the acoustic features of the input audio sequence which can be obtained easily for any set. Our method thus offers the advantage of being able to perform any-to-any audio transformations without using any intermediate ASR system. Our model can capture both the fundamental phonetic properties and the style and identity of each speaker or instrument and apply these properties to the novel, previously unseen words, pitches or even target speaker or musical instruments with very less degradation in the quality of resultant audio.

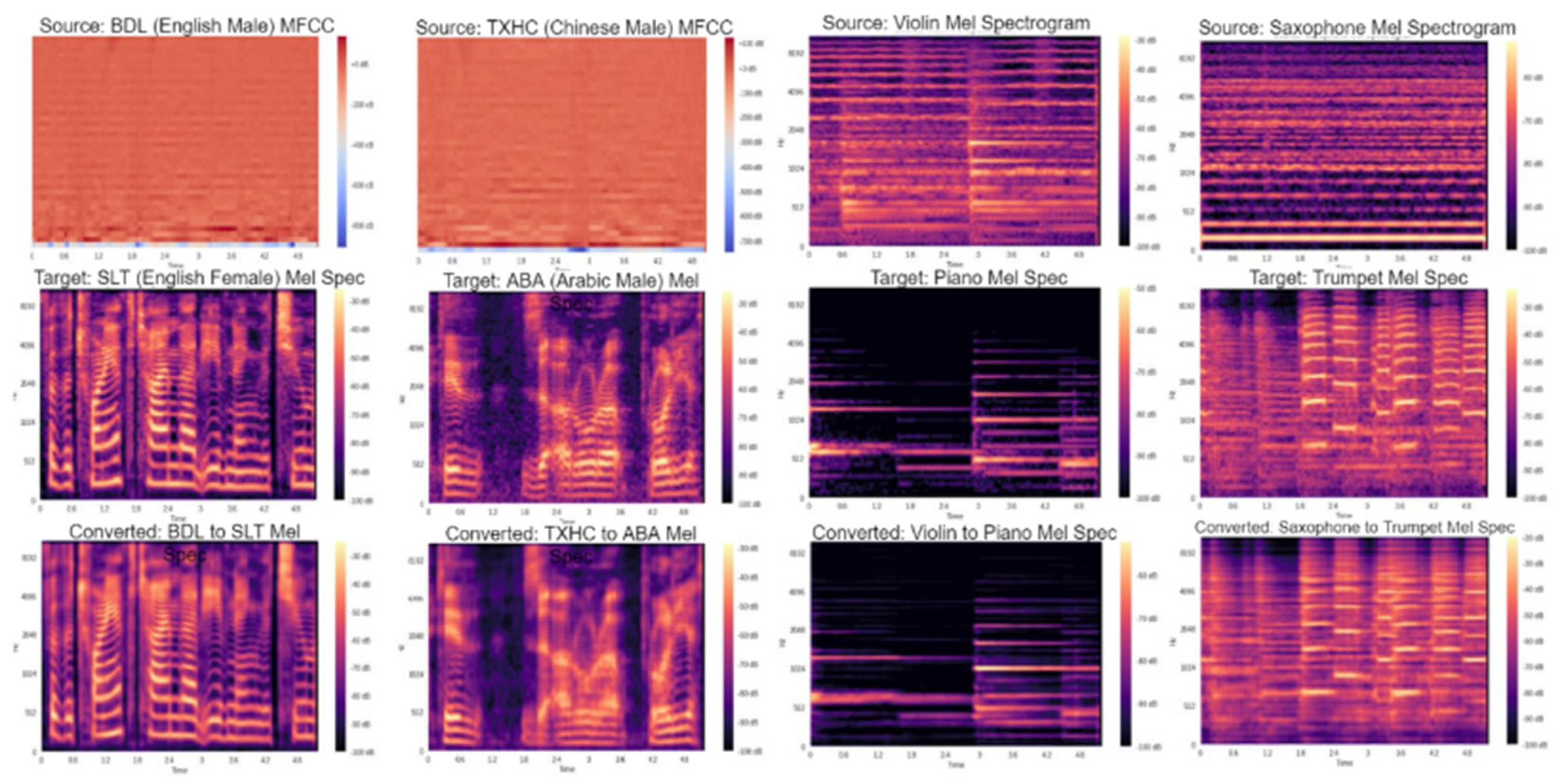

In addition to the subjective evaluation, we also show a set of examples generated by our method in

Figure 2, to observe the sharpness of the spectra generated by our proposed approach.

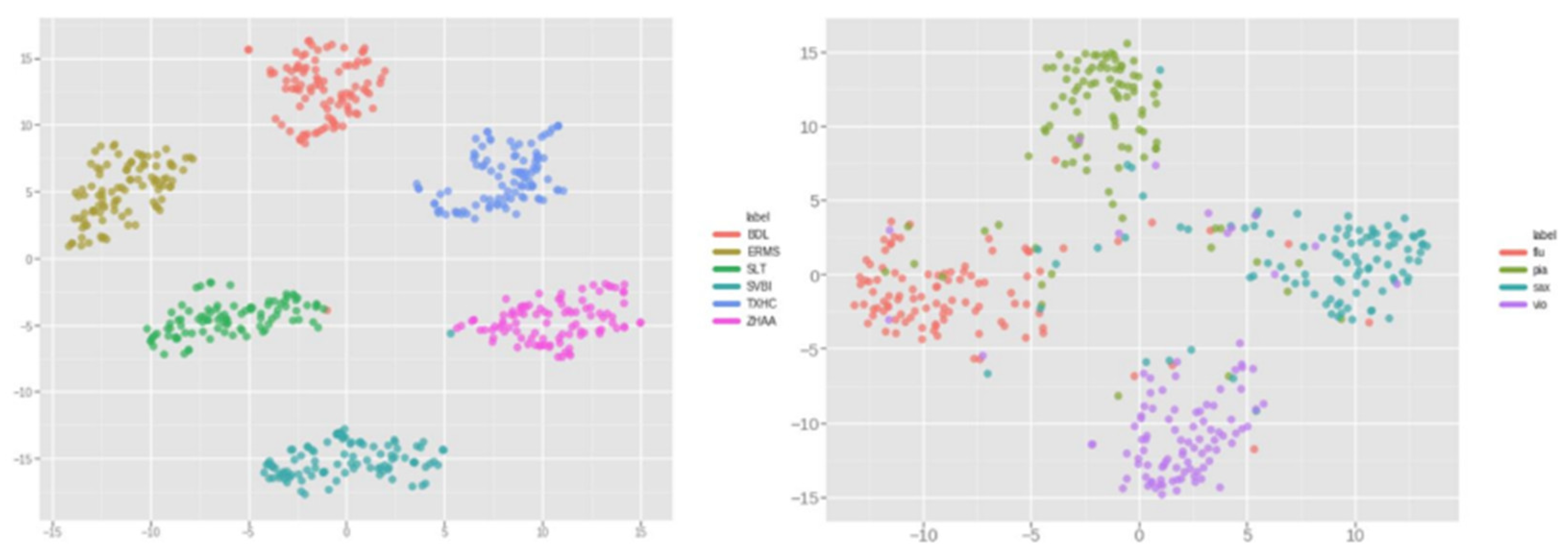

Further in our study, to confirm the validity of the representations encoded by the reference encoder, in

Figure 3, we show the learned style embeddings for both voice conversion and musical style transfer tasks. The style embeddings are visualized using the t-SNE algorithm with perplexity=30 and number of iterations=300 respectively. The t-SNE plots show that the reference encoder is successfully able to cluster sounds belonging to same target identity classes together, thus confirming that the reference encoder can capture and encode the global style specific features and the target identity in the style embeddings.

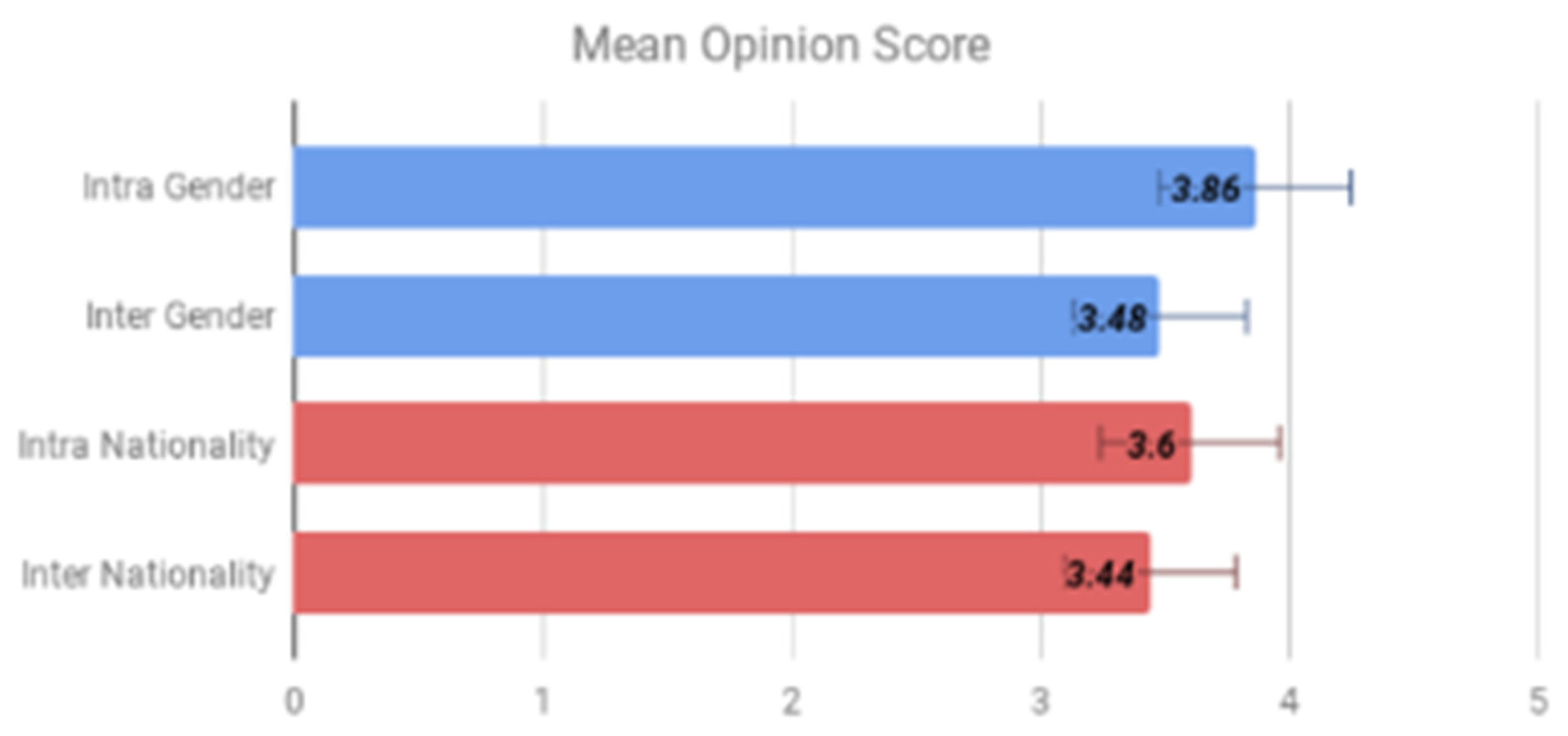

In

Figure 4, we show the MOS for naturalness, calculated on both seen and unseen speakers to evaluate our method over cross-gender and cross-nationality audio transformations. The results indicate that our method is able to generate intelligible and natural speech across gender as well as nationality.

Finally, to ensure that the latent representations from the encoder are independent of the target identity after the latent discriminator based adversarial training, we train a target class verification system that takes the latent representations from the encoder as input to predict the target class identity. The verification accuracies for both the tasks, with and without the latent adversarial training are reported in

Table 3. The drop-in verification accuracies after latent discriminator based adversarial training confirm that the encoder is able to learn latent representations which are independent of the target identity.

ExAI in NLP is mostly focused on understanding the inner workings of the underlying models rather than understanding a particular output of classification. Authors [

40] summarizes the work done on the interpretability of word embeddings, inner workings of RNNs and transformers, the model’s decision, and the different visualization methods while highlighting the interconnections between the different methods. LSTMs and CNNs are relatively more inherently interpretable, and further analysis is required for complete transparency in attention-based models.

This work can find applications where audio transformation is made accessible to everyone. Like, in voice conversion, our proposed method would allow easy voice changes without needing special datasets or complex alignments, which are usually hard to get and use. This would facilitate for example, creation of personalized voice assistants, dubbing for movies, and tools for people with speech difficulties. In music, the proposed method would help change the style of songs, allowing musicians and producers to experiment with new genres and creative ideas. Also, this could be find applicability in entertainment industry, like making video games and virtual environments more realistic with better voice and sound changes. By removing the need for specialized tools, the proposed method can lead to improving user experience by making audio technologies more accessible and personalized.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper introduces a fully differentiable end-to-end method for one-shot audio transformations, addressing the challenges in voice conversion and musical style transfer. Our approach is vocabulary agnostic, capable of transforming audio for both seen and unseen target classes by learning target-specific audio style embeddings. Crucially, it operates without the need for parallel data or intermediate phonetic representations, bypassing the limitations of speaker-independent ASR networks. Subjective evaluations confirm the high quality of audio generated by our method.

Furthermore, our encoder-decoder network integrates neural network models known for their explainability in natural language processing tasks, contributing to the growing field of explainable AI. By enhancing the interpretability of machine learning models in audio processing, our work not only advances theoretical understanding but also offers practical implications across various applications in artificial intelligence.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank students of the Computer Department, NSUT for participating in subjective experiments.

References

- Liz-López, H.; Keita, M.; Taleb-Ahmed, A.; Hadid, A.; Huertas-Tato, J.; Camacho, D. Generation and detection of manipulated multimodal audiovisual content: Advances, trends and open challenges. Inf. Fusion 2023, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianou, Y.; Cappe, O.; Moulines, E. Continuous probabilistic transform for voice conversion. IEEE Trans. Speech Audio Process. 1998, 6, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, T.; Black, A.W.; Tokuda, K. Voice Conversion Based on Maximum-Likelihood Estimation of Spectral Parameter Trajectory. IEEE Trans. Audio, Speech Lang. Process. 2007, 15, 2222–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.H.; Kain, A. Voice conversion using deep neural networks with speaker-independent pre-training. 2014 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 19–23.

- Takashima, R.; Takiguchi, T.; Ariki, Y. Exemplar-Based Voice Conversion Using Sparse Representation in Noisy Environments. IEICE Trans. Fundam. Electron. Commun. Comput. Sci. 2013, E96.A, 1946–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Virtanen, T.; Chng, E.S.; Li, H. Exemplar-Based Sparse Representation With Residual Compensation for Voice Conversion. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio, Speech, Lang. Process. 2014, 22, 1506–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.; Guo, M.; Verma, P. 2018. Conditional End-to-End Audio Transforms. In Proc. Iterspeech. 2295–2299.

- Chin-Cheng Hsu, Hsin-Te Hwang, Yi-Chiao Wu, Yu Tsao, and Hsin-Min Wang. 2016. Voice conversion from non-parallel corpora using Variational Auto-encoder. Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC).

- Hirokazu Kameoka, Takuhiro Kaneko, Kou Tanaka, and Nobukatsu Hojo. 2018. StarGAN-VC: Non-parallel many-to-many voice conversion with star generative adversarial networks. arXiv:1806.02169 (2018).

- Liu, S.; Zhong, J.; Sun, L.; Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Meng, H. 2018. Voice Conversion Across Arbitrary Speakers Based on a Single Target-Speaker Utterance. In Proc. Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (Interspeech).

- Xie, F.-L.; Soong, F.K.; Li, H. A KL Divergence and DNN-Based Approach to Voice Conversion without Parallel Training Sentences. Interspeech 2016. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 287–291.

- Bogach, N.; Boitsova, E.; Chernonog, S.; Lamtev, A.; Lesnichaya, M.; Lezhenin, I.; Novopashenny, A.; Svechnikov, R.; Tsikach, D.; Vasiliev, K.; et al. Speech Processing for Language Learning: A Practical Approach to Computer-Assisted Pronunciation Teaching. Electronics 2021, 10, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago Pascual. 2020. Efficient, end-to-end and self-supervised methods for speech processing and generation.

- Jia, Y.; Weiss, R.J.; Biadsy, F.; Macherey, W.; Johnson, M.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y. 2019. Direct speech-to-speech translation with a sequence-to-sequence model. ISCA.

- Hassija, V.; Chamola, V.; Mahapatra, A.; Singal, A.; Goel, D.; Huang, K.; Scardapane, S.; Spinelli, I.; Mahmud, M.; Hussain, A. Interpreting Black-Box Models: A Review on Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Cogn. Comput. 2024, 16, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adadi, A.; Berrada, M. Peeking Inside the Black-Box: A Survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). IEEE Access 2018, 6, 52138–52160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.V.; Pereira, E.M.; Cardoso, J.S. Machine Learning Interpretability: A Survey on Methods and Metrics. Electronics 2019, 8, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; Garcia, S.; Gil-Lopez, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Inf. Fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrej Karpathy, Justin Johnson, and Li Fei-Fei. 2015. Visualizing and Understanding Recurrent Networks.

- Hou, B.-J.; Zhou, Z.-H. Learning With Interpretable Structure From Gated RNN. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 2020, PP, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott Wisdom, Thomas Powers, James Pitton, and Les Atlas. 2016. Interpretable Recurrent Neural Networks Using Sequential Sparse Recovery.

- John, R. Hershey, Jonathan Le Roux, and Felix Weninger. 2014. Deep Unfolding: Model-Based Inspiration of Novel Deep Architectures.

- Amirhossein Tavanaei. 2020. Embedded Encoder-Decoder in Convolutional Networks Towards Explainable AI.

- Liu, H.; Yin, Q.; Wang, W.Y. 2019. Towards Explainable NLP: A Generative Explanation Framework for Text Classification. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- 2020. Staying True to Your Word: (How) Can Attention Become Explanation? Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Representation Learning for NLP (2020), 131-142.

- Gino Brunner, Yang Liu, Damian Pascual, Oliver Richter, Massimiliano Ciaramita, and Roger Wattenhofer. 2020. On Identifiability in Transformers.

- Sarthak Jain and Byron, C. Wallace. 2019. Attention is not Explanation. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Shikhar Vashishth, Shyam Upadhyay, Gaurav Singh Tomar, and Manaal Faruqui. 2019. Attention Interpretability Across NLP Tasks.

- Chou, J.-C.; Yeh, C.-C.; Lee, H.-Y.; Lee, L.-S. 2018. Multi-target Voice Conversion without Parallel Data by Adversarially learning Disentangled Audio Representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.02812 (2018).

- Yann N. Dauphin, Angela Fan, Michael Auli, and David Grangier. 2017. Language Modeling with Gated Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Machine Learning-Volume 70. JMLR. org. 933–941.

- Zhiheng Huang, Wei Xu, and Kai Yu. 2015. Bidirectional LSTM-CRF Models for Sequence Tagging. arXiv:1508.01991 (2015).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. CoRR 2015, abs/1512.03385.

- Johnson, J.; Alahi, A.; Fei-Fei, L. Perceptual losses for real-time style transfer and super-resolution. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Amsterdam, The Netherland, 8–16 October 2016; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 694–711. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, C.-C.; Hwang, H.-T.; Wu, Y.-C.; Tsao, Y.; Wang, H.-M. 2017. Voice Conversion from Unaligned Corpora using Variational Autoencoding Wasserstein Generative Adversarial Networks. In Proc. Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (Interspeech). 3364–3368.

- John Kominek and Alan Black. 2004. The CMU Arctic Speech Databases. In Fifth ISCA workshop on speech synthesis.

- Zhao, G.; Sonsaat, S.; Silpachai, A.; Lucic, I.; Chukharev-Hudilainen, E.; Levis, J.; Gutierrez-Osuna, R. 2018. L2-ARCTIC: A Non-Native English Speech Corpus. Perception Sensing Instrumentation Lab (2018).

- Juan Bosch, Jordi Janer, Ferdinand Fuhrmann, and Perfecto Herrera. 2012. A Comparison of Sound Segregation Techniques for Predominant Instrument Recognition in Musical Audio Signals.. In ISMIR. 559–564.

- D. Griffin and Jae Lim. 1984. Signal estimation from modified short-time fourier transform. Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, IEEE Transactions 32, 2 (1984), 236–243.

- Biao Zhang, Deyi Xiong, and Jinsong Su. 2016. Cseq2seq: Cyclic Sequence-to-Sequence Learning. arXiv:1607.08725 (2016).

- El Zini, J.; Awad, M. On the Explainability of Natural Language Processing Deep Models. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 55, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).