Introduction

Today, immunotherapy has emerged as a promising and innovative strategy that is widely used to treat a variety of diseases. Depending on whether it suppresses or activates the host immune response, it may be classified as immunosuppressive or immunostimulatory. Immunosuppressive therapies help treat various types of autoimmune diseases such as type 1 diabetes, obesity, atherosclerosis, and rheumatoid arthritis. On the other hand, immunostimulatory therapies refer to something that activates the immune response, thus helping to treat cancer and infectious diseases. In recent years, the use of immunotherapy has gained significant attention in the field of cancer treatment due to its milder side effects compared to conventional treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery. Our immune system can distinguish cancer cells from normal cells by recognizing tumor antigens. Tumor-specific antigens (TSAs), i.e., specific molecules produced exclusively by cancer cells, such as PSA or prostate-specific antigens, and tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), are two major targets in immunotherapy (1-3). TAAs are specific molecules produced in both normal and cancer cells, such as CEA or carcinoembryonic antigen. Activation of host immunity can be achieved by various methods, including the introduction of various cancer vaccines, monoclonal antibodies, immune blockers, and cell-based therapies, which have been proven to be effective in many patients. Cancer immunotherapy not only treats cancer by inducing a strong anti-tumor immune response, but also controls metastasis and prevents its recurrence. Hence, it represents a major advantage over conventional cancer therapies. However, some limitations are also associated with existing cancer immunotherapies, such as the induction of destructive autoimmune diseases and the failure to effectively deliver cancer antigens to immune cells (2-4). In 2018, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to James Allison and Tasuko Honjo for the discovery of immune checkpoint therapy. PD-1 acts as a T-cell brake, and PD-1/PD-L1 activation suppresses T-cell proliferation, survival, and activity in the tumor microenvironment. Clinical studies suggest that PD-1/PD-L1 blockade can effectively induce antitumor immune responses with less toxicity in many types of cancer. Currently, most inhibitors of this pathway are monoclonal antibodies, and while the development of small molecule inhibitors that directly block PD-1/PD-L1 interactions is still in its infancy. Over the past decade, with a better understanding of PD-1/PD-L1 interactions and the underlying mechanisms, there has been great interest in developing bioassays that can be used to screen small molecule inhibitors of PD-1/PD-L1 (5-7). Most monoclonal antibodies have inherent shortcomings compared with small molecule PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, including limited permeability, immunogenicity, and high cost. Small inhibitors typically have fewer side effects, shorter biological half-lives, and easier and less expensive routes of administration. Recently, several natural product-derived small molecules with blocking effects against PD-1/PD-L1 interactions have been reported (8-10).

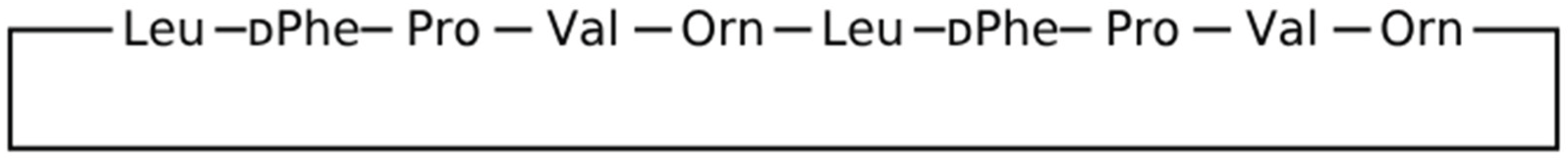

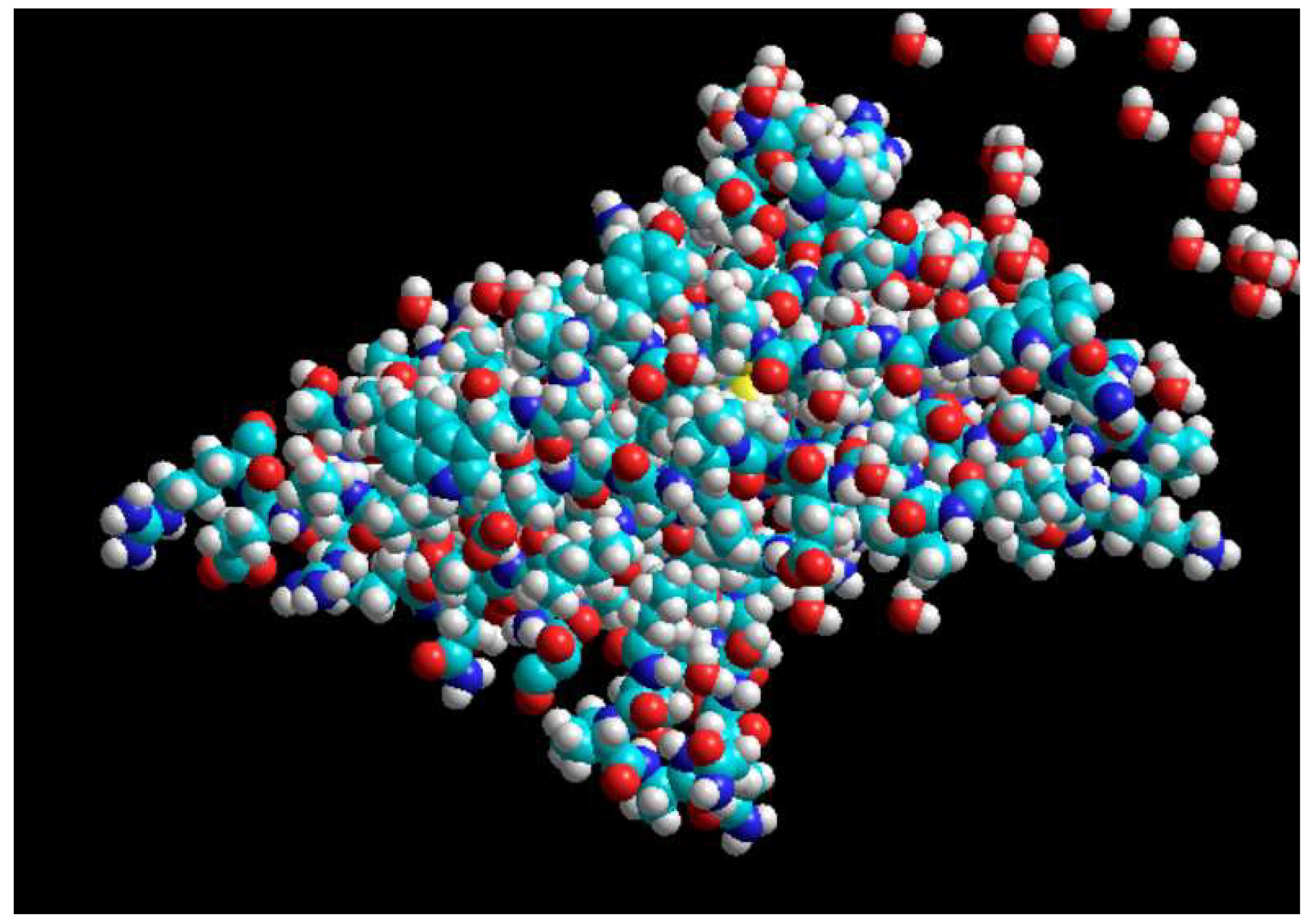

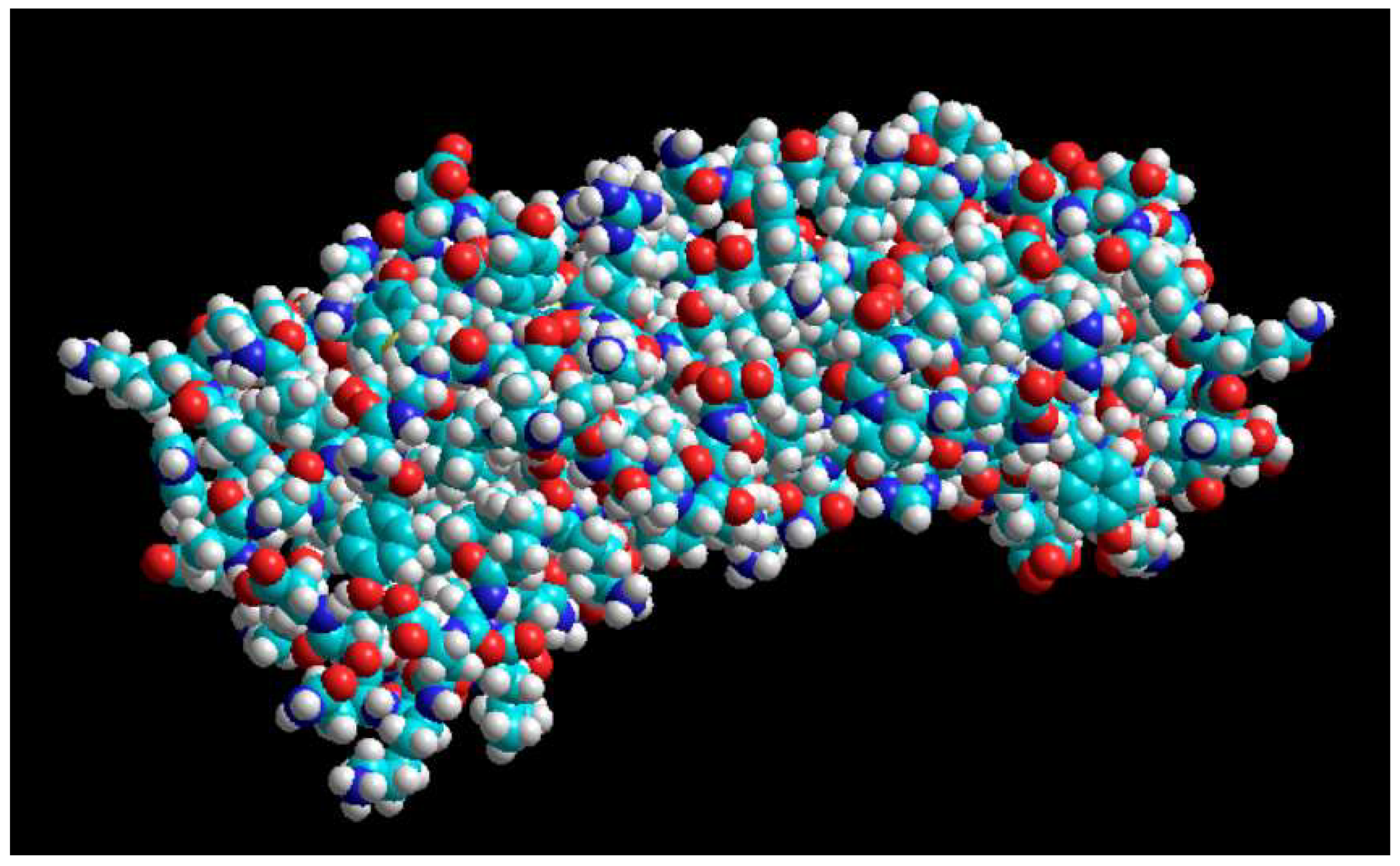

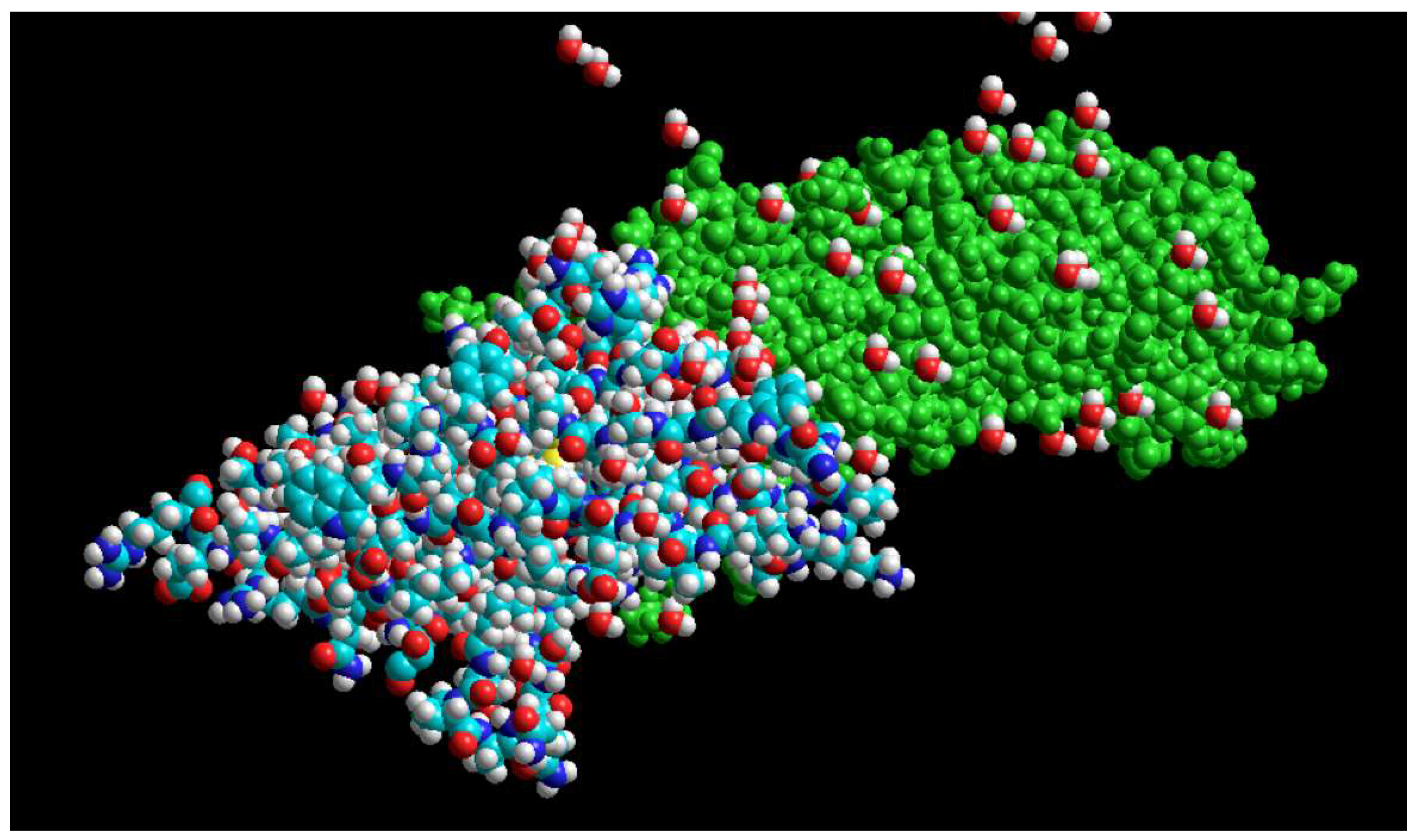

Gramicidin S is a natural decacyclopeptide consisting of two repeating pentapeptides as cyclo((-Val-Orn-Leu-D-Phe-Pro-)2), which have a unique structure with hydrophilic and hydrophobic parts. Sun and colleagues hypothesized that the amphiphilic structure of gramicidin S could complement the PD-L1/PD-L1 interface, thereby facilitating their binding capacity. Intraperitoneal (IP) injection of this substance with anti-CD8 antibody suppressed tumor volume (54.8%) and tumor weight (64.9%) in an animal model bearing B16F10 tumors. Immunohistochemical staining showed that Cyclo(-Leu-DTrp-Pro-Thr-Asp-Leu-DPheLys(Dde)-Val-Arg treatment increased the percentage of CD3+ T cells and CD8+ T cells in tumor tissues (10). PD-1 acts as a T-cell brake, and PD-1/PD-L1 activation suppresses T-cell proliferation, survival, and activity in the tumor microenvironment. Clinical studies have shown that PD-1/PD-L1 blockade can effectively induce antitumor immune responses. Currently, most inhibitors of this pathway are monoclonal antibodies, and the development of small molecule inhibitors that directly block PD-1/PD-L1 interactions is still in its infancy (1-7). Most monoclonal antibodies have inherent shortcomings compared to small molecule PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors, such as These include limited permeability, immunogenicity, and high cost. Small inhibitors usually have fewer side effects, longer biological half-lives, and easier and less expensive administration routes. Although several small molecules derived from natural products have recently been reported to have blocking effects against PD-1/PD-L1 interactions (8-9), their efficacy has not yet been proven.

The new generation of anticancer compounds are peptide sequences that can lead to possible inhibition of PD-1 and PD-L-1 molecules. The objective of this study was to evaluate the antitumor effects of peptide sequences based on gramicidin molecule as potential inhibitors of PD-1 and PD-L-1 molecules in computerized and in vitro conditions.

Materials and Methods

Summary of the Work Process

In this study, the gramicidin sequence was used as the base molecule and simpler derivatives were designed by adding or subtracting polar amino acids. For this, the sequences were first created using the Askaloff software and then the structure was optimized. Then, using the molecular docking method (with the HDOCK online site), the interaction of all derivatives with PD1 and PDL1 molecules was evaluated individually, and their docking energy and RMSD were noted and compared. For the final selection of the best derivative, the toxicity (with the Toxinpred database), allergenicity (with the Allertop database), and antigenicity (with the ABCpred database) parameters were also considered using online databases. In the experimental part, to evaluate the selected peptide in vitro, the best peptide identified in the computational part was selected and synthesized and purified using a solid phase technique by the French company Proteogenics. To prove the involvement of the synthesized peptide in the binding between PD1 and PDL1 molecules, an ELISA kit was used. For this, first, the PD1 molecule was coated in the ELISA wells, and then PDL1 molecules were exposed to them, and the amount of color produced at a wavelength of 630 was evaluated by enzymatic method. Then, different concentrations of the selected peptide were added to the coated wells, and after incubation, PDL1 molecules were added, and the amount of color produced at a wavelength of 630 was evaluated as in the previous step. Finally, the percentage of effectiveness of the selected peptide compared to the control was calculated. To understand the anticancer effect of the selected peptide on cancer cells, a toxicity test using the MTT method was used. For this, serial concentrations (100, 50, and 25 mg/ml) were exposed to MFC-7 cancer cells, and after 12, 24, and 48 hours, the rate of cell death was calculated compared to the control.

Computational Part

First, the sequence of gramicidin S peptide (

Figure 1), which is a cyclic peptide, was extracted using the PubMed site

.

We then identified the polar amino acids (

Table 1) using the information included in IMGT, which shows that out of the twenty amino acids, five have a side chain that can carry a charge, and at pH 7, two of them, aspartic acid and glutamic acid, have a negative charge, and the other three, including lysine, arginine, and histidine, carry a positive charge. In the next step, we added these polar amino acid derivatives in different states and in different orders and sequences to both sides of the cyclic gramicidin S sequence (which we considered to be open). In this process, a capital Latin letter was used as a symbol to represent each amino acid in the peptide sequence

.

To each side of this opened peptide ring, we added from one to a maximum of three of these polar amino acid derivatives, resulting in forty different peptide combinations of gramicidin S and five polar amino acids (

Table 2)

.

Then, we arranged these forty different peptide sequences that we obtained by adding polar amino acid derivatives to gramicidin S in a table in a Word file, and then we examined each of these peptide sequences separately on the AllerTOP sites (to examine the allergenicity and sensitization of the peptide to the body) (

https://www.ddg-pharmfac.net/AllerTOP/) and ToxinPred (to examine the toxicity of the peptide to the body (

https://webs.iiitd.edu.in/raghava/toxinpred/) and the PubMed site (

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to examine the degree of peptide homology (higher homology is desirable because it shows that the synthesized peptide is more similar to the body's own peptides and, as a result, there is a lower probability of it being recognized by the immune system and causing a reaction in the body). In this way, we examined the values obtained from these sites for allergenicity and antigenicity and We entered toxicity and homology into the table created in the Word file against each peptide. Given that antigenicity is our first and most important criterion in peptide selection, we calculated it using the Alertup site for all forty peptide combinations made, and we examined the remaining parameters only for peptides that obtained the smallest numbers below one on the Alertup site and were acceptable in terms of antigenicity. In the next step, we examined these obtained numbers and selected three of the peptides that had received the best and most appropriate numbers, and in the HDOCK site, the quality of their interaction with PD1 and PDL1 was examined separately, and we obtained the energy and RMSD for each. Then, finally, according to the results obtained from the H-Doc site, we selected one of these three peptides as the selected peptide after performing the following calculations and introduced it to the peptide synthesis company to synthesize it and provide it to us for conducting the relevant experiments. In the calculations performed to select the peptide from these three final peptides, the absolute value of the total energy resulting from the interaction of each peptide with PD1 and PDL1 was considered as the main selection criterion, and the peptide for which this value was the highest was selected. Based on the above calculations, the peptide with the sequence KKKVRLFPVRLFPDD was selected

.

Experimental Part

To prove the involvement of the synthesized peptide in the binding between PD1 and PDL1 molecules, an ELISA kit was used. For this, first, the PD1 molecule was coated in the ELISA wells, and then PDL1 molecules were exposed to them, and the amount of color produced at a wavelength of 630 was evaluated by enzymatic method. Then, different concentrations of the selected peptide were added to the coated wells, and after incubation, PDL1 molecules were added, and the amount of color produced at a wavelength of 630 was evaluated as in the previous step. Finally, the percentage of effectiveness of the selected peptide compared to the control was calculated. To understand the anticancer effect of the selected peptide on cancer cells, a toxicity test using the MTT method was used. For this, serial concentrations (100, 50, and 25 mg/ml) were exposed to MFC-7 cancer cells, and after 12, 24, and 48 hours, the amount of cell death was calculated compared to the control.

For this, first, one ml of distilled water was added to the peptide vial and mixed well. Then, a concentration series of peptide solution was prepared in a 96-well microplate of the purchased ELISA kit. This was done in wells D-E-F from wells 1 to 12. Wells A-B-C also contained only distilled water. In wells D1-D2-E1-E2-F1-F2, 50 μl of the initial peptide solution was poured, and then distilled water was added to wells D2-E2-F2 to the end. Then, 50 μl was transferred from well D2 to well D3, and from D3 to D4, and so on. This was also done for E and F. Then, according to the kit instructions, the plate was placed at 37 degrees for half an hour, and then it was firmly turned upside down on the table to drain, and then 50 μl of washing solution was added to these 6 rows. In the next step, 20 μl of conjugate solution was added to all and placed at 37 degrees for half an hour. It was again firmly tapped on the table inverted to drain, and then 50 μl of substrate A solution and 50 μl of substrate B solution were added and incubated for 10 minutes at 37 degrees. Then, the optical density was immediately read with an ELISA reader (

Figure 2) at wavelengths of 630 and 450 and the plate and print were taken

.

To understand the anticancer effect of the selected peptide on cancer cells, a toxicity test using the MTT method was used. For this, serial concentrations of the peptide were exposed to MCF-7 cancer cells and after 24, 48 and 72 hours, the rate of cell death was calculated compared to the control. In 3 96-well microplates, first serial concentrations of the peptide solution were prepared in a volume of 50 μl, similar to the steps above. Then, a cell suspension with a concentration of one million cells/ml was added to all wells and allowed to stand for 24, 48 and 72 hours. After the incubation of each plate, 10 microliters of MTT solution was added to the wells, and after 3 hours, 50 microliters of DMSO solution was added and the optical density was read at a wavelength of 630 nm.

Results

Experimental Results

ELISA Test Results

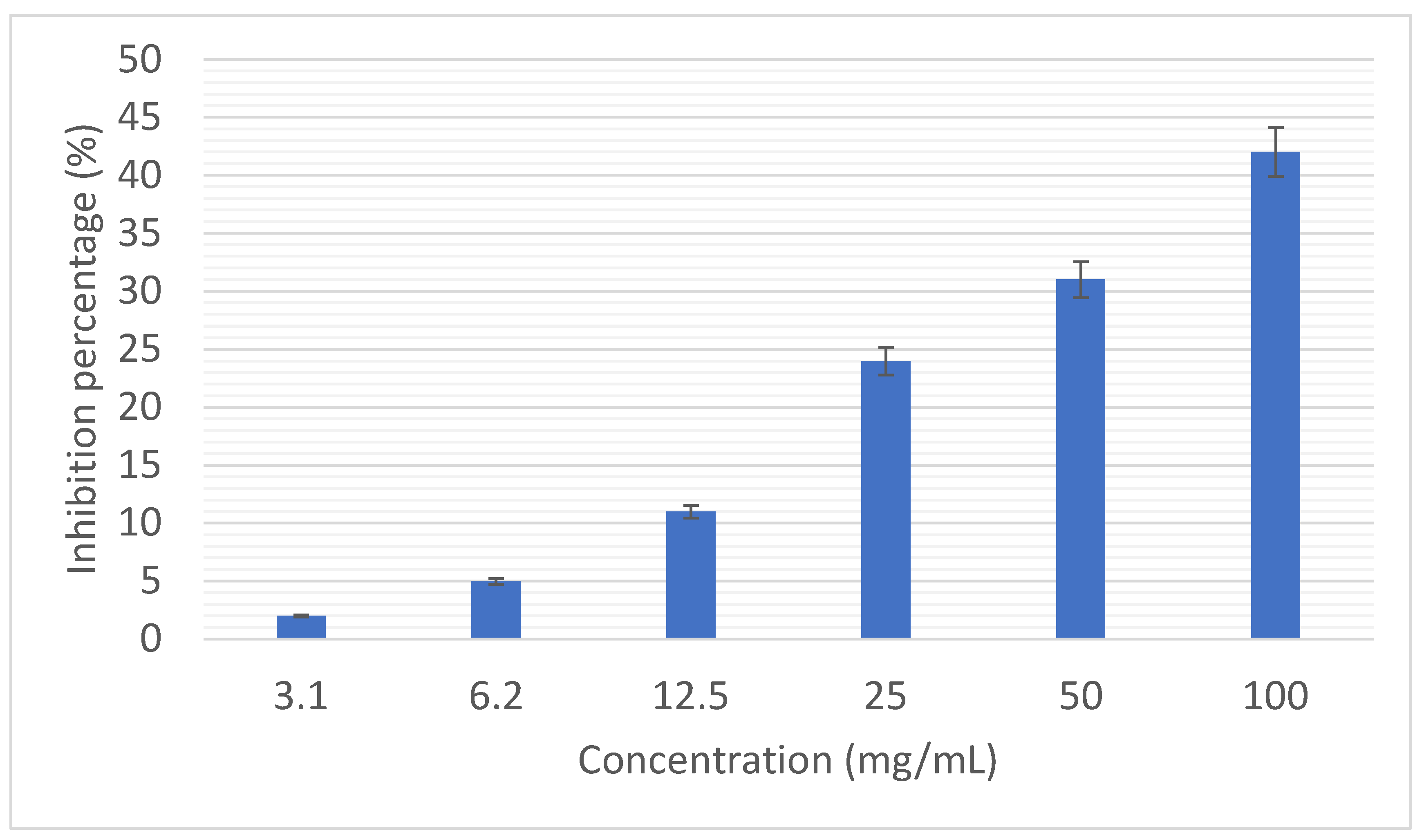

Figure 6 shows the percentage of inhibition of the interaction of PD1 with PDL1 by different concentrations of the selected peptide. It was clearly determined that by increasing the concentration of the selected peptide to 42%, inhibition of the interaction of PD1 with PDL1 occurs. Statistically, the inhibition rate of the concentration of 100 mg/ml was significantly different from the inhibition rate of other concentrations (P<0.05)

.

Results of MTT Test

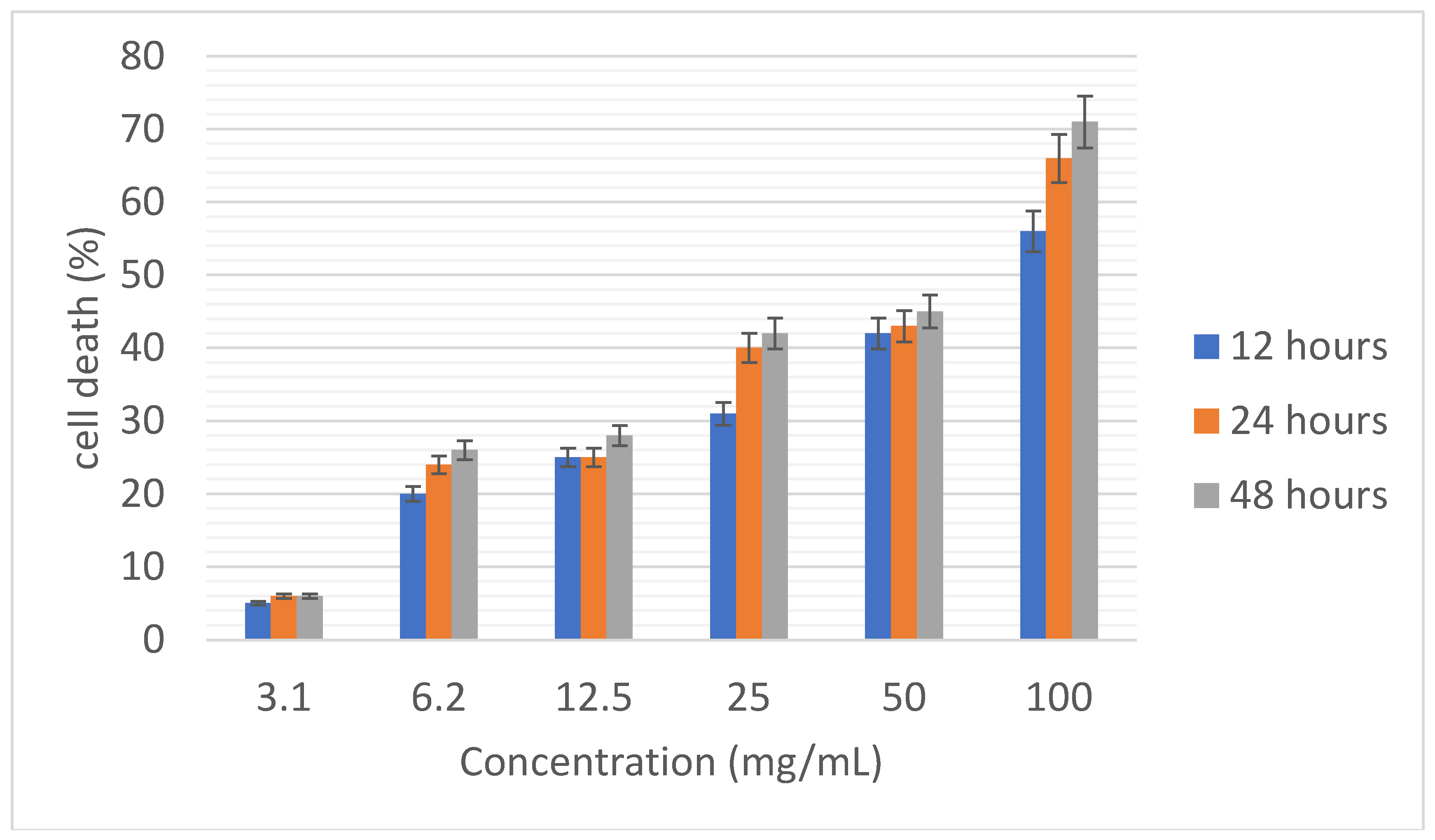

Figure 7 shows the percentage of breast cancer cell death (MCF-7) by different concentrations of the selected peptide at times of 12, 24 and 48 hours. Here too, the rate of cell death increased with increasing concentration and time. Statistically, the rate of cell death caused by the concentration of 100 mg/ml was significantly different from the rate of cell death caused by other concentrations (P<0.05)

.

Discussion

A new generation of anticancer compounds are peptide sequences that can lead to potential inhibition of PD-1 and PD-L-1 molecules. The aim of this study was to evaluate the antitumor effects of peptide sequences based on the gramicidin molecule as potential inhibitors of PD-1 and PD-L-1 molecules in computer and in vitro conditions. In the bioinformatics section, only 8 peptides had antigenicity less than one and were selected for the next stage. Also, by examining the antigenicity, allergenicity, toxicity and homology, only 3 peptides had all the necessary characteristics. In the experimental section, it was clearly determined that by increasing the concentration of the selected peptide up to 42%, the interaction of PD1 with PDL1 was inhibited. Also, examining the percentage of breast cancer cell death (MCF-7) by different concentrations of the selected peptide at times of 12, 24 and 48 hours showed that the rate of cell death increases with increasing concentration and time. This study demonstrated that by integrating bioinformatics and experimental tests, a suitable peptide can be designed to potentially inhibit PD-1 and PD-L-1 molecules. Further complementary tests should be performed to investigate the efficacy and potential side effects of the selected peptide, and then tested in animal models and in clinical trials.

The success of antibodies targeting immune checkpoints such as programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) has changed the landscape of cancer therapy. Although these antibodies show significant durable clinical activity, low response rates and immune-related side effects are increasingly evident in antibody-based approaches. For further steps in cancer immunotherapy, new therapeutic strategies, including combination therapies and alternative therapies, are highly warranted. In line with this discovery and development of small molecules, checkpoint inhibitors are being actively pursued, and ongoing efforts have culminated in clinical trials of highly bioavailable oral checkpoint inhibitors. This review focuses on small molecule agents that target the cancer immunotherapy pathway, highlighting various chemotypes/scaffolds and their properties, including binding and function, along with the reported mechanism of action. Lessons learned from clinical trials of small molecules and important points to consider for their clinical development are also discussed. Checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized cancer therapy by harnessing the power of the immune system to fight cancer, and this development is now considered one of the most exciting discoveries of the 21st century (1). Among the various types of cancer immunotherapies such as immunotherapies, adoptive T cell transfer, oncolytic viruses, and cancer vaccines, immunotherapies have shown remarkable response in clinical trials and are currently considered the most successful class of cancer immunotherapies. Since the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the anti-CTLA-4 antibody ipilimumab in 2011, several antibodies targeting the PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune pathway have also been approved for the treatment of cancer in various indications, among many others (2). In this review, we highlight the progress in the discovery and development of small molecule agents that interfere with the PD-1 pathway, with the majority of reported compounds targeting PDL1, along with their mechanisms of action and specific considerations relevant for their advanced development (1-3).

While these antibody-based therapies show significant clinical activity, they suffer from serious treatment-related toxicities known as immune-related adverse events (irAEs), largely due to immune system imbalance (3). A wide range of irAEs have been reported to involve virtually any tissue or organ, with the most severe complications manifesting as skin rashes, pneumonitis, hypothyroidism, pancreatitis, encephalopathy, hepatitis, myocarditis, and immune cytopenias. Antibodies targeting PD-1 pathways have been reported to have a lower incidence of adverse events than drugs targeting the CTLA-4 pathway (5), whereas combination therapy with antibodies targeting both CTLA-4 and PD-1 has a higher rate of irAEs with a higher number of grade 3 and 4 treatment-related adverse events and treatment discontinuation (6, 7). Even though irAEs can be resolved by appropriate management of immunosuppression with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents such as infliximab, it may place patients at higher risk of infection (8). Persistent target inhibition due to a long half-life (>15–20 days) and 70% target occupancy for months likely contributes to severe irAEs (9–11). Apart from toxicity, one of the major drawbacks of approved PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies is that they respond only in a subset of the patient population, which may be due in part to compensatory mechanisms such as upregulation of alternative immune checkpoints such as T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing 3 (TIM-3) and Ig suppressor of T-cell activation domain (VISTA) (12, 13). Physiological barriers to antibodies (14) limit their exposure to the tumor, and the large size of these agents warrants their intravenous dosing in a hospital setting. The cost of treatment with a single agent can exceed US$100,000 per year per patient. In addition, However, the need for rational combination with other therapeutic agents to achieve a greater response is expected to make checkpoint antibody therapy very expensive (15).

Although the lack of PD-1/PD-L1 antibody-based targeted agents underscores the need for alternative approaches, the development of small molecule inhibitors has lagged significantly, despite their great potential. The advantages of small molecule agents over antibodies for targeting PD-1 and other safe pathways are summarized in

Table 1. However, small molecule agents also have limitations, including shorter half-lives and widespread drug distribution leading to on- and off-target toxicity, the potential for reduced specificity and selectivity, and species-specific activity in some cases, making it very challenging to find suitable preclinical pharmacology models. These shortcomings may have contributed to the initial lack of enthusiasm in the scientific community compared to monoclonal antibody-based inhibitors, as reflected in the much less preclinical and clinical efforts focused on small molecule-based approaches. Lessons learned from the highly successful development of small molecule therapeutics against specific targets including protein tyrosine kinases, growth factor receptors, and cell cycle regulatory proteins can be adapted to fully exploit the distinct advantages of small molecule approaches (16-18)

.

Patil et al. used the AlphaL-ISA assay to screen the inhibitory effects of FDA-approved macrocyclic drugs against PD-1/PD-L1 interactions. A panel of 20 macrocyclic compounds including actinomycin D, amphotericin B, bacitracin, brivastatin, candididine, clarithromycin, cyclosporine A, cyanocobalamin, erythromycin, everolimus, danamycin gel, ivermectin B1a, macbesin, monochromostalini, ricksa, monocorin furlini, rimlon, cyanocobalamin, and troleandomycin were screened at a concentration of 50 μM using the AlphaL-ISA assay. Among these macrocyclics, only rifampin effectively blocked the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 (18-20). Furthermore, molecular docking demonstrated that rifabutin is able to form a stable ligand-protein complex facilitated by several molecular forces including π-π stacking interactions and hydrogen bonding (11). Kaempferol and its glycosides, including kaempferol-3,7-dirhamnoside and kaempferol-7-O-rhamnoside, flavonoids from Geranium thunbergia (Geranii Herba extract) have been reported to have antitumor activity (12). In vitro assays have also been performed to demonstrate that kaempferol is able to inhibit PD-1/PD-L1 interactions. Choi et al. reported that Salvia plebeia R. Br extract (SPE) blocked the interactions between PD-1 and PD-L1. Two flavonoids, apigenin and cosmocin, extracted from SPE showed inhibitory effects against the interactions between PD-1 and PD-L1 in a cell-based assay and a competitive ELISA. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of SPE on PD-1 and PD-L1 was further supported by in vivo assays using an animal model bearing human PD-L1 MC38 tumor (13). Li et al. screened 800 plant extracts for PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory capacity, leading to the identification of Rhus verniciflua Stokes extract as an active inhibitor using a competitive ELISA. Four phenolic compounds, including eriodictyol, fisetin, quercetin, and liquoiritigenin, were isolated from Rhus verniciflua Stokes extract with PD-1/PD-L1 blocking activity (14). Bao et al. reported the isolation of a flavonoid, glycyrrhiza uralensis, and its PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitory activity using a commercially available homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF) assay. The isolated compounds showed PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition ratios ranging from 30 to 65% at 100 μM (15). Kim et al. reported that black raspberry (Rubus core-anus Miquel) extract (RCE) inhibited PD-1 and PD-L1 binding with an IC50 value of 83.8 ± 4.7 μg/mL (16). Caffeoylquinic acid and its derivatives with a caffeoyl group attached to the -3, -4, and -5 positions of quinic acid, respectively, were identified as PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors using SPR spectroscopy. Compared with dicaffeoylquinic acids, monocaffeoylquinic acid derivatives had a stronger binding affinity for PD-1 and PD-L1 (17).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the antitumor effects of peptide sequences based on the gramicidin molecule as potential inhibitors of PD-1 and PD-L-1 molecules in computer and in vitro conditions. In the bioinformatics section, only 8 peptides had antigenicity less than one and were selected for the next stage. Also, by examining the antigenicity, allergenicity, toxicity and homology, only 3 peptides had all the necessary characteristics. In the experimental section, it was clearly determined that by increasing the concentration of the selected peptide up to 42%, the interaction of PD1 with PDL1 was inhibited. Also, the percentage of breast cancer cell death (MCF-7) by different concentrations of the selected peptide at 12, 24 and 48 hours showed that the rate of cell death increases with increasing concentration and time. This study showed that by integrating bioinformatics and experimental tests, a suitable peptide can be designed for the possible inhibition of PD-1 and PD-L-1 molecules. To investigate the efficacy and identify possible side effects of the selected peptide, further complementary tests should be performed and then tested in an animal model and in a clinical trial. It is suggested that the efficacy of the selected peptide be investigated in another independent study on an animal model and then on humans. It is suggested that the possible side effects of this peptide be investigated in an independent study.

References

- Wang SH, Yu J. Structure-based design for binding peptides in anti-cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2018;156:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Zhang L, Ding N, Yang X, Zhang J, He J, Li Z, Sun LQ. Identification and characterization of DNAzymes targeting DNA methyltransferase I for suppressing bladder cancer proliferation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;461:329–333. [CrossRef]

- Ingram JR, Blomberg OS, Rashidian M, Ali L, Garforth S, Fedorov E, Fedorov AA, Bonanno JB, Le Gall C, Crowley S, et al. Anti-CTLA-4 therapy requires an Fc domain for efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115:3912–3917. [CrossRef]

- Di JX, Zhang HY. C188-9 a small-molecule STAT3 inhibitor, exerts an antitumor effect on head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Drugs. 2019;30:846–853. [CrossRef]

- Brun S, Bassissi F, Serdjebi C, Novello M, Tracz J, Autelitano F, Guillemot M, Fabre P, Courcambeck J, Ansaldi C, et al. GNS561, a new lysosomotropic small molecule, for the treatment of intrahe-patic cholangiocarcinoma. Invest New Drugs. 2019;37:1135–1145. [CrossRef]

- Jahangirian H, Kalantari K, Izadiyan Z, Rafiee-Moghaddam R, Shameli K, Webster TJ. A review of small molecules and drug delivery applications using gold and iron nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019;14:1633–1657. [CrossRef]

- Tyagi A, Tuknait A, Anand P, Gupta S, Sharma M, Mathur D, Joshi A, Singh S, Gautam A, Raghava GP. CancerPPD: A database of anticancer peptides and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database Issue):D837–D843. [CrossRef]

- Thundimadathil J. Cancer treatment using peptides: Current therapies and future prospects. J Amino Acids. 2012;2012:967347. [CrossRef]

- Vlieghe P, Lisowski V, Martinez J, Khrestchatisky M. Synthetic therapeutic peptides: Science and market. Drug Discov Today. 2010;15:40–56. [CrossRef]

- Otvos L., Jr Peptide-based drug design: Here and now. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;494:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Hoskin DW, Ramamoorthy A. Studies on anticancer activities of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:357–375. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues EG, Dobroff AS, Taborda CP, Travassos LR. Antifungal and antitumor models of bioactive protective peptides. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2009;81:503–520. [CrossRef]

- Droin N, Hendra JB, Ducoroy P, Solary E. Human defensins as cancer biomarkers and antitumour molecules. J Proteomics. 2009;72:918–927. [CrossRef]

- Simons K, Ikonen E. How cells handle cholesterol. Science. 2000;290:1721–1726. [CrossRef]

- Sok M, Sentjurc M, Schara M. Membrane fluidity characteristics of human lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 1999;139:215–220. [CrossRef]

- Zwaal RF, Schroit AJ. Pathophysiologic implications of membrane phospholipid asymmetry in blood cells. Blood. 1997;89:1121–1132. [CrossRef]

- Schweizer F. Cationic amphiphilic peptides with cancer-selective toxicity. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:190–194. [CrossRef]

- Utsugi T, Schroit AJ, Connor J, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Elevated expression of phosphatidylserine in the outer membrane leaflet of human tumor cells and recognition by activated human blood monocytes. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3062–3066.

- Harris F, Dennison SR, Singh J, Phoenix DA. On the selectivity and efficacy of defense peptides with respect to cancer cells. Med Res Rev. 2013;33:190–234. [CrossRef]

- Li G, Huang Y, Feng Q, Chen Y. Tryptophan as a probe to study the anticancer mechanism of action and specificity of alpha-helical anticancer peptides. Molecules. 2014;19:12224–12241. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).