Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

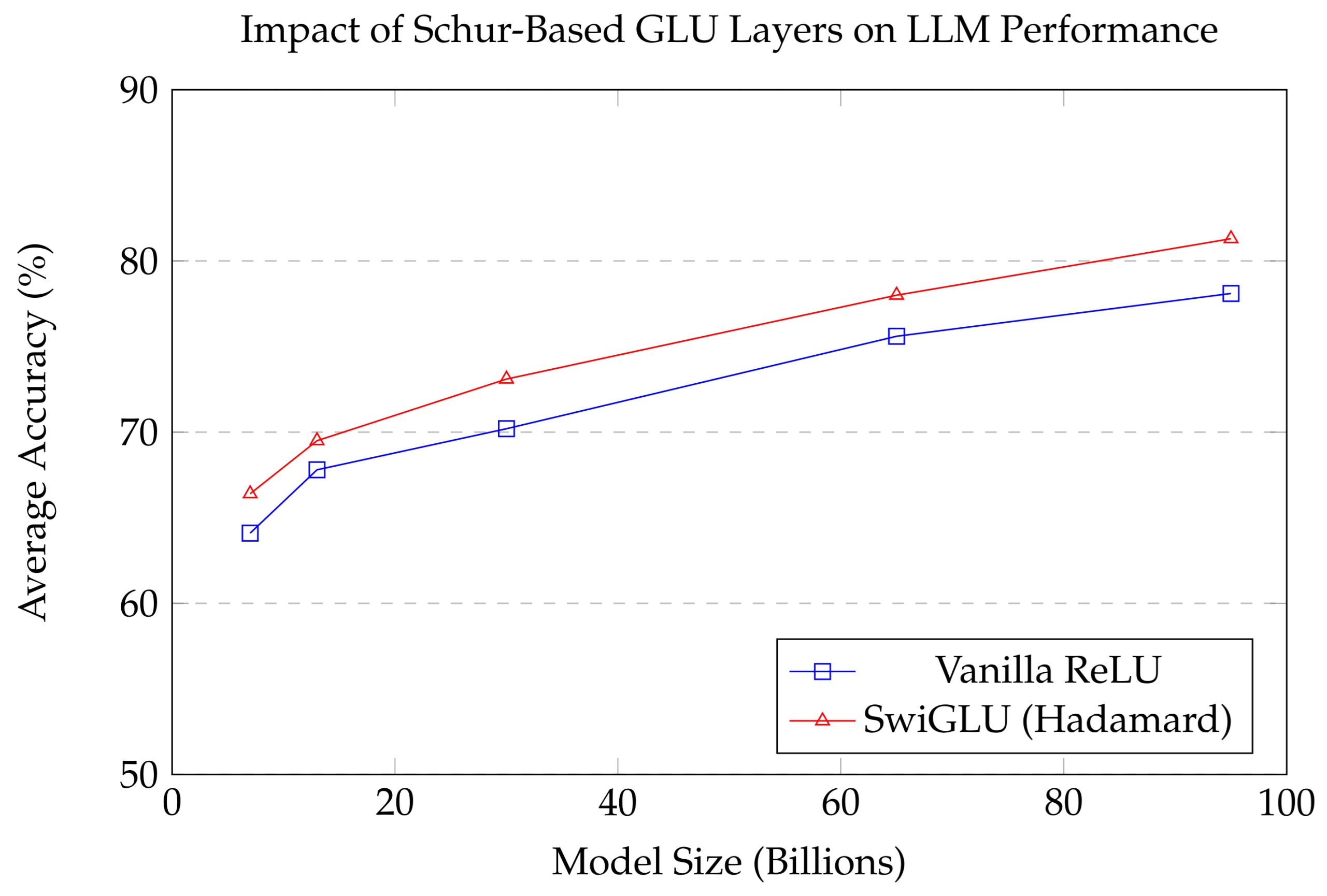

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

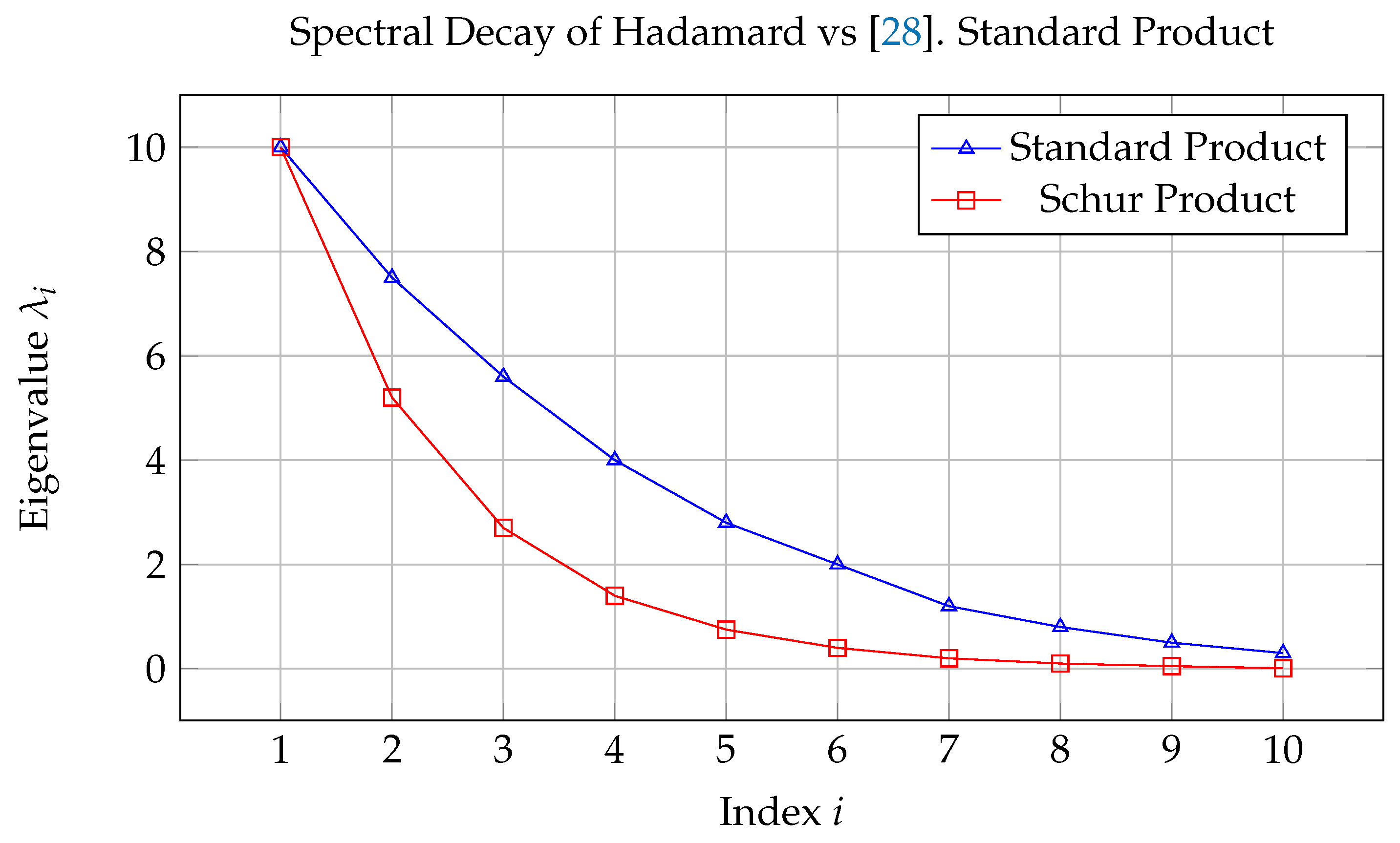

2. Mathematical Foundations of the Schur Product

3. Schur Product in Deep Learning Architectures

4. Schur Product in Computer Vision

5. Schur Product in Large Language Models

6. A Unified Framework and Theoretical Perspectives

7. Implications and Future Directions

- Neural Operator Algebras: Formalizing the class of neural networks closed under Hadamard multiplication yields insight into the structure of gate-based models and their compositional hierarchies [102]. For instance, one may study whether Hadamard-enriched architectures correspond to subclasses of multiplicative semigroup algebras with polynomial-time computable spectra [103].

- Sparse and Interpretable Models: Since Schur products are inherently element-wise, they lend themselves to sparsity and pruning [106]. Leveraging this, we can construct interpretable models where each feature dimension is conditionally controlled, enabling token-wise routing and interpretable modular computation [107].

- Unification of Attention and Gating: By viewing softmax-based attention and GLU-like gating as instances of generalized Schur operations under appropriate normalizations, it may be possible to design hybrid models that interpolate between discrete and continuous attention, offering both interpretability and flexibility.

8. Conclusions

References

- Cheng, J.; Tian, S.; Yu, L.; Lu, H.; Lv, X. Fully convolutional attention network for biomedical image segmentation. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2020, 107, 101899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glorot, X.; Bengio, Y. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. 2010, pp. 249–256.

- Ni, Z.L.; Zhou, X.H.; Wang, G.A.; Yue, W.Q.; Li, Z.; Bian, G.B.; Hou, Z.G. SurgiNet: Pyramid Attention Aggregation and Class-wise Self-Distillation for Surgical Instrument Segmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 76, 102310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Tam, D.; Muqeeth, M.; Mohta, J.; Huang, T.; Bansal, M.; Raffel, C. Few-shot parameter-efficient fine-tuning is better and cheaper than in-context learning. 2022.

- Dong, X.; Huang, J.; Yang, Y.; Yan, S. More is less: A more complicated network with less inference complexity. 2017, pp. 5840–5848.

- Rodriguez-Opazo, C.; Marrese-Taylor, E.; Fernando, B.; Li, H.; Gould, S. DORi: discovering object relationships for moment localization of a natural language query in a video. 2021, pp. 1079–1088.

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Efficient tensor decomposition-based filter pruning. Neural Networks 2024, 178, 106393. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.R.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv, 2023; arXiv:2307.09288 . [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, L.; Liu, C.; Qiao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Tian, Q.; Yuille, A. Sort: Second-order response transform for visual recognition. 2017, pp. 1359–1368.

- Rusch, T.K.; Mishra, S. UnICORNN: A recurrent model for learning very long time dependencies. 2021, pp. 9168–9178.

- Lu, J.; Shan, C.; Jin, K.; Deng, X.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, J.; Guo, Y. ONavi: Data-driven based Multi-sensor Fusion Positioning System in Indoor Environments. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 12th International Conference on Indoor Positioning and Indoor Navigation (IPIN); 2022; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tulyakov, S.; Liu, M.Y.; Yang, X.; Kautz, J. Mocogan: Decomposing motion and content for video generation. 2018, pp. 1526–1535.

- Ji, T.Y.; Chu, D.; Zhao, X.L.; Hong, D. A unified framework of cloud detection and removal based on low-rank and group sparse regularizations for multitemporal multispectral images 2022. 60, 1–15.

- Ging, S.; Zolfaghari, M.; Pirsiavash, H.; Brox, T. Coot: Cooperative hierarchical transformer for video-text representation learning 2020. 33, 22605–22618.

- Nguyen, B.X.; Do, T.; Tran, H.; Tjiputra, E.; Tran, Q.D.; Nguyen, A. Coarse-to-Fine Reasoning for Visual Question Answering. 2022, pp. 4558–4566.

- Labach, A.; Salehinejad, H.; Valaee, S. Survey of dropout methods for deep neural networks. arXiv, 2019; arXiv:1904.13310. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Z.; Yang, S.; Sun, W.; Shen, X.; Li, D.; Sun, W.; Zhong, Y. HGRN2: Gated Linear RNNs with State Expansion. In Proceedings of the First Conference on Language Modeling; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Simon-Gabriel, C.J.; Chrysos, G.; Cevher, V. Robust NAS under adversarial training: benchmark, theory, and beyond. 2024.

- Yang, X.; Gao, C.; Zhang, H.; Cai, J. Auto-parsing network for image captioning and visual question answering. 2021, pp. 2197–2207.

- Hong, D.; Gao, L.; Yao, J.; Zhang, B.; Plaza, A.; Chanussot, J. Graph convolutional networks for hyperspectral image classification 2020. 59, 5966–5978.

- Guo, S.; Lin, Y.; Feng, N.; Song, C.; Wan, H. Attention based spatial-temporal graph convolutional networks for traffic flow forecasting. 2019, Vol. 33, pp. 922–929.

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Mi, L.; Chen, Z. AFNet: Adaptive fusion network for remote sensing image semantic segmentation 2020. 59, 7871–7886.

- Duke, B.; Taylor, G.W. Generalized hadamard-product fusion operators for visual question answering. In Proceedings of the 2018 15th Conference on Computer and Robot Vision (CRV). IEEE; 2018; pp. 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.B.; Huang, T.Z.; Shen, S.Q.; Li, H. Lower bounds for the minimum eigenvalue of Hadamard product of an M-matrix and its inverse. Linear Algebra and its applications 2007, 420, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiros, R.; Zhu, Y.; Salakhutdinov, R.R.; Zemel, R.; Urtasun, R.; Torralba, A.; Fidler, S. Skip-thought vectors 2015. 28.

- Nova, A.; Dai, H.; Schuurmans, D. Gradient-free structured pruning with unlabeled data. PMLR, 2023, pp. 26326–26341.

- Deng, C.; Wu, Q.; Wu, Q.; Hu, F.; Lyu, F.; Tan, M. Visual grounding via accumulated attention. 2018, pp. 7746–7755.

- Wadhwa, G.; Dhall, A.; Murala, S.; Tariq, U. Hyperrealistic image inpainting with hypergraphs. 2021, pp. 3912–3921.

- Sun, L.; Zheng, B.; Zhou, J.; Yan, H. Some inequalities for the Hadamard product of tensors. Linear and Multilinear Algebra 2018, 66, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.A.; Zhai, Y.; Xu, N.; Nie, W.; Li, W.; Zhang, Y. Region-Aware Image Captioning via Interaction Learning. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wu, T. Image synthesis from reconfigurable layout and style. 2019, pp. 10531–10540.

- Zhan, F.; Yu, Y.; Wu, R.; Zhang, J.; Cui, K.; Xiao, A.; Lu, S.; Miao, C. Bi-level feature alignment for versatile image translation and manipulation. 2022, pp. 224–241.

- Jayakumar, S.M.; Czarnecki, W.M.; Menick, J.; Schwarz, J.; Rae, J.; Osindero, S.; Teh, Y.W.; Harley, T.; Pascanu, R. Multiplicative Interactions and Where to Find Them. 2020.

- Du, S.; Lee, J. On the power of over-parametrization in neural networks with quadratic activation. 2018.

- Vinograde, B. Canonical positive definite matrices under internal linear transformations. Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 1950, 1, 159–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Liu, L.; Hao, F.; He, F.; Cheng, J. Text-to-Image Synthesis based on Object-Guided Joint-Decoding Transformer. 2022, pp. 18113–18122.

- Chen, J.; Gao, C.; Meng, E.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, S. Reinforced Structured State-Evolution for Vision-Language Navigation. 2022, pp. 15450–15459.

- Kumar, A.; Irsoy, O.; Ondruska, P.; Iyyer, M.; Bradbury, J.; Gulrajani, I.; Zhong, V.; Paulus, R.; Socher, R. Ask me anything: Dynamic memory networks for natural language processing. 2016, pp. 1378–1387.

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, X.; Dong, J.; Cheng, T.; Liang, J. SwinBTS: A method for 3D multimodal brain tumor segmentation using swin transformer. Brain Sciences 2022, 12, 797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livni, R.; Shalev-Shwartz, S.; Shamir, O. On the computational efficiency of training neural networks. 2014, pp. 855–863.

- Cisse, M.; Bojanowski, P.; Grave, E.; Dauphin, Y.; Usunier, N. Parseval networks: Improving robustness to adversarial examples. 2017.

- Hitchcock, F.L. The Expression of a Tensor or a Polyadic as a Sum of Products. J. of Math. and Phys. 1927, 6, 164–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.; Gu, A. Transformers are SSMs: Generalized models and efficient algorithms through structured state space duality. 2024.

- Nguyen, Q.; Mondelli, M.; Montufar, G.F. Tight bounds on the smallest eigenvalue of the neural tangent kernel for deep relu networks. 2021, pp. 8119–8129.

- Sumby, W.H.; Pollack, I. Visual contribution to speech intelligibility in noise. The journal of the acoustical society of america 1954, 26, 212–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, X.; Yang, W.; Ouyang, W.; Ma, C.; Yuille, A.L.; Wang, X. Multi-context attention for human pose estimation. 2017, pp. 1831–1840.

- Gao, P.; You, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Li, H. Multi-modality latent interaction network for visual question answering. 2019, pp. 5825–5835.

- Rocamora, E.A.; Sahin, M.F.; Liu, F.; Chrysos, G.G.; Cevher, V. Sound and Complete Verification of Polynomial Networks. 2022.

- Bae, J.; Kwon, M.; Uh, Y. FurryGAN: High Quality Foreground-Aware Image Synthesis. 2022, pp. 696–712.

- Li, Y.; Tarlow, D.; Brockschmidt, M.; Zemel, R. Gated graph sequence neural networks. arXiv, 2015; arXiv:1511.05493 . [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Zeng, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. Logish: A new nonlinear nonmonotonic activation function for convolutional neural network. Neurocomputing 2021, 458, 490–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.L.; Li, M.; Wang, F.; Lai, R.; Wang, G. Expressivity and trainability of quadratic networks. arXiv, 2021; arXiv:2110.06081 . [Google Scholar]

- Chu, P.; Bian, X.; Liu, S.; Ling, H. Feature space augmentation for long-tailed data. 2020, pp. 694–710.

- Misra, D. Mish: A self regularized non-monotonic neural activation function. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1908.08681 4, 10–48550. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Kang, P.; Liu, X. Hierarchical gating networks for sequential recommendation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining, 2019, pp. 825–833.

- Vinyals, O.; Toshev, A.; Bengio, S.; Erhan, D. Show and tell: A neural image caption generator. 2015, pp. 3156–3164.

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Shlens, J.; Szegedy, C. Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples. 2015.

- Zhang, C.; Lin, G.; Lai, L.; Ding, H.; Wu, Q. Calibrating Class Activation Maps for Long-Tailed Visual Recognition. arXiv, 2021; arXiv:2108.12757 . [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Tian, S.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Z. SBDF-Net: A versatile dual-branch fusion network for medical image segmentation. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2022, 78, 103928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kyaw, Z.; Yu, J.; Chang, S.F. Ppr-fcn: Weakly supervised visual relation detection via parallel pairwise r-fcn. 2017, pp. 4233–4241.

- Srivastava, R.K.; Greff, K.; Schmidhuber, J. Training very deep networks 2015. 28.

- Cao, T.; Kreis, K.; Fidler, S.; Sharp, N.; Yin, K. Texfusion: Synthesizing 3d textures with text-guided image diffusion models. 2023, pp. 4169–4181.

- CAO, Q.; KHANNA, P.; LANE, N.D.; BALASUBRAMANIAN, A. MobiVQA: Efficient On-Device Visual Question Answering. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. 2017, pp. 5998–6008.

- Su, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Niu, C.; Liu, R.; Sun, W.; Pei, D. Robust anomaly detection for multivariate time series through stochastic recurrent neural network. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery & data mining, 2019, pp. 2828–2837.

- Chung, J.; Gulcehre, C.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Empirical evaluation of gated recurrent neural networks on sequence modeling. arXiv, 2014; arXiv:1412.3555 . [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Zhu, X.; Clifton, D.A. Multimodal learning with transformers: A survey 2023. 45, 12113–12132.

- Chrysos, G.G.; Wang, B.; Deng, J.; Cevher, V. Regularization of polynomial networks for image recognition. 2023, pp. 16123–16132.

- Li, X.; Huang, J.; Deng, L.J.; Huang, T.Z. Bilateral filter based total variation regularization for sparse hyperspectral image unmixing. Information Sciences 2019, 504, 334–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Lampert, C.; Martius, G. Learning equations for extrapolation and control. 2018, pp. 4442–4450.

- Li, Y.; Long, S.; Yang, Z.; Weng, H.; Zeng, K.; Huang, Z.; Wang, F.L.; Hao, T. A Bi-level representation learning model for medical visual question answering. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2022, 134, 104183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Karras, T.; Garg, A.; Debnath, S.; Patney, A.; Patel, A.; Anandkumar, A. Semi-supervised stylegan for disentanglement learning. 2020, pp. 7360–7369.

- Xia, Q.; Yu, C.; Peng, P.; Gu, H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, K. Visual Question Answering Based on Position Alignment. In Proceedings of the 2021 14th International Congress on Image and Signal Processing, BioMedical Engineering and Informatics (CISP-BMEI). IEEE; 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.E.; Sejnowski, T.J. Optimal perceptual inference. 1983, Vol. 448, pp. 448–453.

- Dai, A.M.; Le, Q.V. Semi-supervised sequence learning. 2015, Vol. 28.

- Kim, Y.; Jernite, Y.; Sontag, D.; Rush, A.M. Character-aware neural language models. 2016.

- Glorot, X.; Bordes, A.; Bengio, Y. Deep sparse rectifier neural networks. 2011, pp. 315–323.

- Tan, K.; Huang, W.; Liu, X.; Hu, J.; Dong, S. A multi-modal fusion framework based on multi-task correlation learning for cancer prognosis prediction. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2022, 126, 102260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, W.; Jaitly, N.; Le, Q.; Vinyals, O. Listen, attend and spell: A neural network for large vocabulary conversational speech recognition. 2016, pp. 4960–4964.

- Tsuzuku, Y.; Sato, I.; Sugiyama, M. Lipschitz-margin training: Scalable certification of perturbation invariance for deep neural networks. 2018.

- Peng, Y.; Dalmia, S.; Lane, I.; Watanabe, S. Branchformer: Parallel mlp-attention architectures to capture local and global context for speech recognition and understanding. 2022, pp. 17627–17643.

- Wu, Y.; Chrysos, G.G.; Cevher, V. Adversarial audio synthesis with complex-valued polynomial networks. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2206.06811 . [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; She, Q.; Zhang, J. MaskNet: introducing feature-wise multiplication to CTR ranking models by instance-guided mask. arXiv, 2021; arXiv:2102.07619 . [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Kong, Q.; Wang, W.; Plumbley, M.D. Large-scale weakly supervised audio classification using gated convolutional neural network. 2018, pp. 121–125.

- Tang, C.; Salakhutdinov, R.R. Multiple futures prediction 2019. 32.

- Zhang, Z.; Cai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Learning hierarchy-aware knowledge graph embeddings for link prediction. 2020, Vol. 34, pp. 3065–3072.

- Srivastava, N.; Mansimov, E.; Salakhudinov, R. Unsupervised learning of video representations using lstms. 2015, pp. 843–852.

- Li, F.; Li, G.; He, X.; Cheng, J. Dynamic Dual Gating Neural Networks. 2021, pp. 5330–5339.

- Babiloni, F.; Marras, I.; Deng, J.; Kokkinos, F.; Maggioni, M.; Chrysos, G.; Torr, P.; Zafeiriou, S. Linear Complexity Self-Attention With 3rd Order Polynomials 2023. 45, 12726–12737.

- Rahaman, N.; Baratin, A.; Arpit, D.; Draxler, F.; Lin, M.; Hamprecht, F.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. On the spectral bias of neural networks. 2019.

- Feng, Y.; Xu, H.; Jiang, J.; Liu, H.; Zheng, J. ICIF-Net: Intra-Scale Cross-Interaction and Inter-Scale Feature Fusion Network for Bitemporal Remote Sensing Images Change Detection 2022. 60, 1–13.

- Murdock, C.; Li, Z.; Zhou, H.; Duerig, T. Blockout: Dynamic model selection for hierarchical deep networks. 2016.

- Pan, L.; Chen, X.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, H.; Yi, S.; Liu, Z. Variational relational point completion network. 2021, pp. 8524–8533.

- Katharopoulos, A.; Vyas, A.; Pappas, N.; Fleuret, F. Transformers are rnns: Fast autoregressive transformers with linear attention. PMLR, 2020, pp. 5156–5165.

- Watrous, R.; Kuhn, G. Induction of finite-state automata using second-order recurrent networks. 1991, Vol. 4.

- Wang, Z.; Wang, K.; Yu, M.; Xiong, J.; Hwu, W.m.; Hasegawa-Johnson, M.; Shi, H. Interpretable visual reasoning via induced symbolic space. 2021, pp. 1878–1887.

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, F.; Chrysos, G.G.; Cevher, V. Generalization Properties of NAS under Activation and Skip Connection Search. 2022.

- Drumetz, L.; Veganzones, M.A.; Henrot, S.; Phlypo, R.; Chanussot, J.; Jutten, C. Blind hyperspectral unmixing using an extended linear mixing model to address spectral variability 2016. 25, 3890–3905.

- MacKay, M.; Vicol, P.; Lorraine, J.; Duvenaud, D.; Grosse, R. Self-tuning networks: Bilevel optimization of hyperparameters using structured best-response functions. 2019.

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, H.; Sheng, L.; Yan, J.; Wang, X.; Shao, J. Camp: Cross-modal adaptive message passing for text-image retrieval. 2019, pp. 5764–5773.

- Kumaraswamy, S.K.; Shi, M.; Kijak, E. Detecting human-object interaction with mixed supervision. 2021, pp. 1228–1237.

- Hyeon-Woo, N.; Ye-Bin, M.; Oh, T.H. Fedpara: Low-rank hadamard product for communication-efficient federated learning. 2022.

- Hyeon-Woo, N.; Ye-Bin, M.; Oh, T.H. FedPara: Low-rank Hadamard Product for Communication-Efficient Federated Learning. 2022.

- Gallego, G.; Delbrück, T.; Orchard, G.; Bartolozzi, C.; Taba, B.; Censi, A.; Leutenegger, S.; Davison, A.J.; Conradt, J.; Daniilidis, K.; et al. Event-based vision: A survey 2020. 44, 154–180.

- Cho, K.; van Merriënboer, B.; Bahdanau, D.; Bengio, Y. On the Properties of Neural Machine Translation: Encoder–Decoder Approaches. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of SSST-8, Eighth Workshop on Syntax, Semantics and Structure in Statistical Translation, 2014, pp. 103–111.

- Fan, F.; Xiong, J.; Wang, G. Universal Approximation with Quadratic Deep Networks. Neural Netw. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Property | Standard Product | Schur Product | Kronecker Product |

|---|---|---|---|

| Notation | |||

| Dimensionality | |||

| Element-wise [25]? | No | Yes | No |

| Associative | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Distributive | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Commutative | No | Yes | No |

| Preserves PSD | Yes (under conditions) | Yes | No |

| Model | Modulation Layer | Conditioning Source | Hadamard Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| SENet | Channel-wise excitation | Global pooled features | Feature reweighting |

| CBAM | Channel + spatial attention | Convolutions + pooling | Axis-wise gating |

| FiLM-VQA | Feature-wise affine modulation | Language vector | Cross-modal conditioning |

| BAN (Bilinear Attention Net) | Bilinear attention maps | Question embedding | Modulated fusion |

| DETR | Transformer self-attention | Pairwise affinity matrix | Contextual weighting |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).