Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

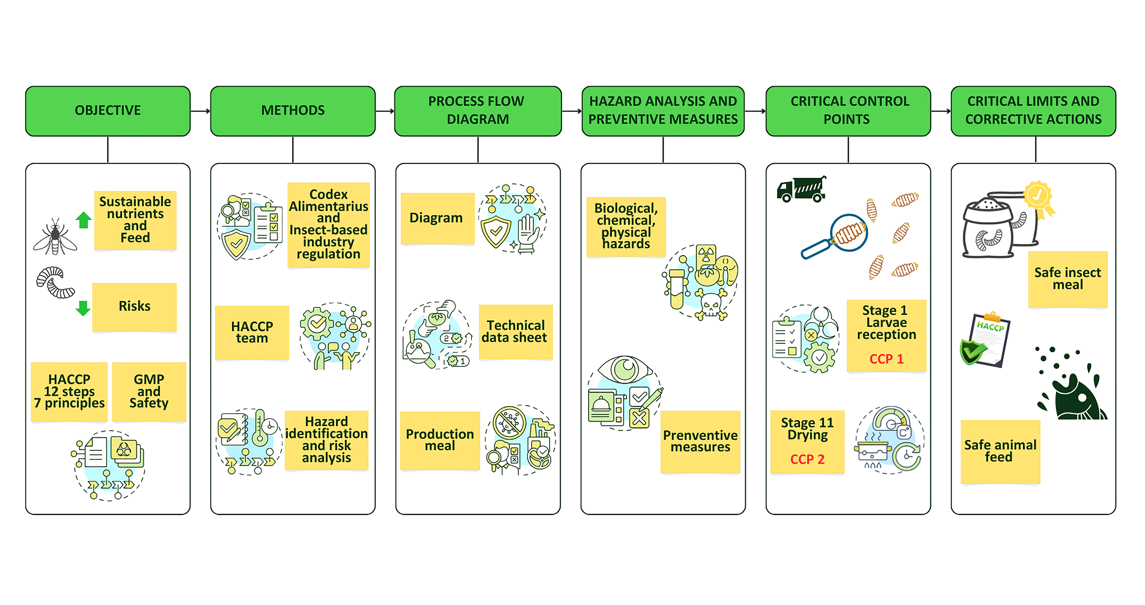

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context and Data Sources

2.2. HACCP Team Formation

2.3. Review of HACCP Prerequisites

2.4. Product Identification, Intended Use, and Process Description

2.5. Hazard Identification, Risk Analysis, and Preventive Measures

2.6. Identification of Critical Control Points, Critical Limits, Monitoring System, and Corrective Actions

2.7. Validation of Control Measures and Verification of the HACCP System

2.8. Documentation and Record-Keeping

3. Results

3.1. Final Product Description

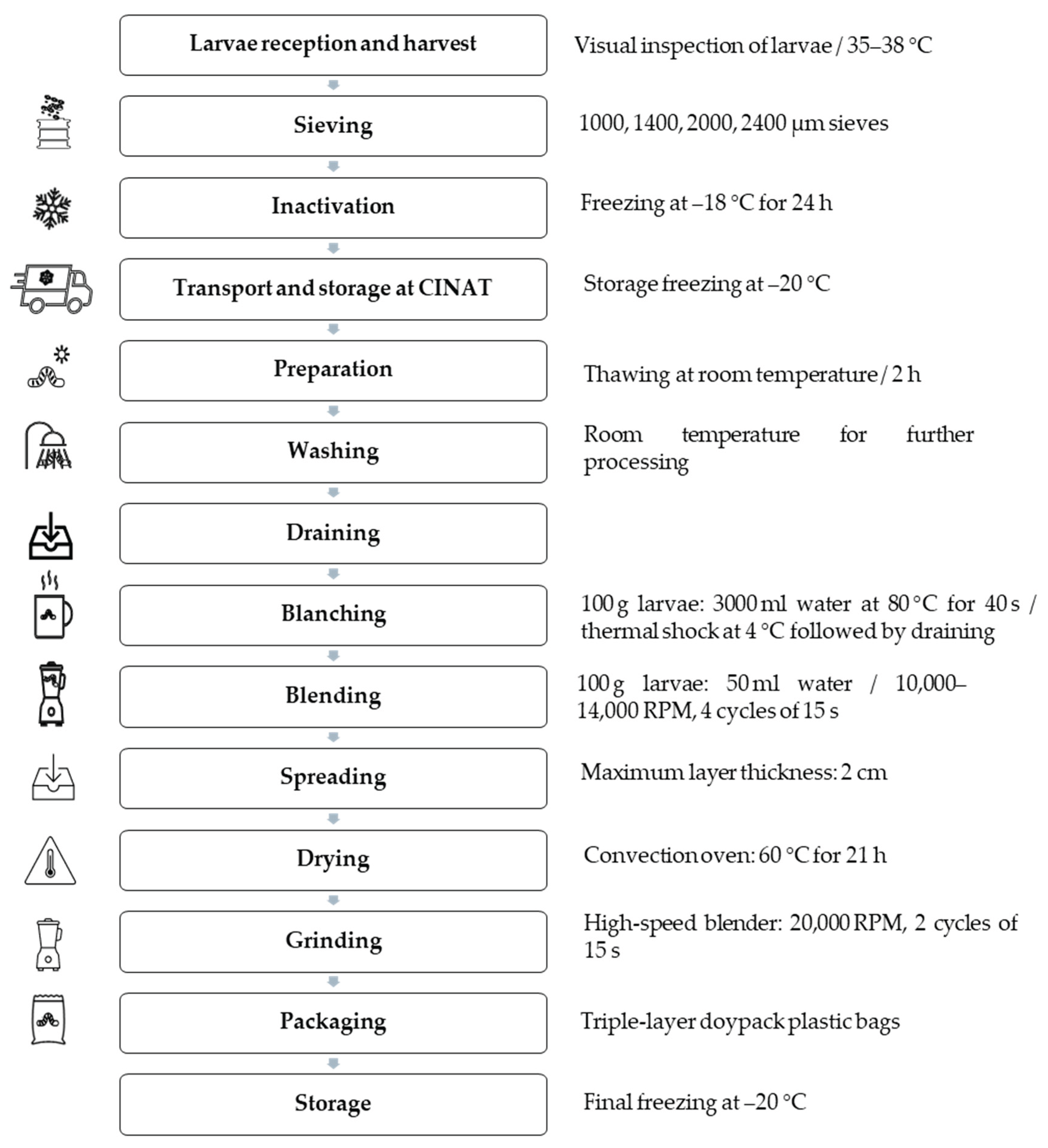

3.2. Flow Diagram to Produce BSFL Meal

3.3. Hazard Analysis and Preventive Measures

3.4. Identification of CCPs

3.5. Establishment of Critical Limits, Monitoring System, and Corrective Actions

3.6. Validation and Verification of HACCP System

3.8. Required Documentation for HACCP Implementation

4. Discussion

4.1. Product Technical Specification

4.2. Interpretation of the Results of the Hazard Analysis

4.3. Effectiveness of the HACCP System and Challenges in Implementation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BSFLM | Black soldier fly larvae meal |

| HACCP | Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points |

| CCP | critical control points |

| FSIS | Food Safety and Inspection Service |

| PPR | Prerequisite Program |

| EFSA | European Food Safety Authority |

| CINAT | Centre for Terrestrial Arthropod Research (Spanish acronym) |

| IPIFF | International Platform of Insects for Food and Feed |

| GMPAF | Good Manufacturing Practices for Animal Feed |

| BPM | Good Manufacturing Practices |

References

- Van Huis, A. , Van Itterbeeck J., Klunder H., Mertens E., Halloran A., Muir G., Vantomme P. Edible insects: Future prospects for food and feed security. FAO; /: from: https, 3253. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, G. , Fels-Klerx H., Rijk T., Oonincx D. Aflatoxin B1 Tolerance and Accumulation in Black Soldier Fly Larvae (Hermetia illucens) and Yellow Mealworms (Tenebrio molitor). Toxins 2017, 9, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rumpold, B.A. , Schlüter, O.K. Potential and challenges of insects as an innovative source for food and feed production. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2013, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkifli, N.F.N.M. , Seok-Kian, A.Y., Seng, L.L., Mustafa, S., Kim, Y.S., Shapawi, R. Nutritional value of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) larvae processed by different methods. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0263924 Available from:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poma, G. , Cuykx, M., Amato, E., Calaprice, C., Focant, J.F., Covaci, A. Evaluation of hazardous chemicals in edible insects and insect-based food intended for human consumption. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 100, 70–79 Available from:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau, T. , Vilcinskas, A., Joop, G. Sustainable farming of the mealworm Tenebrio molitor for the production of food and feed. Z. Naturforsch. C 2017, 72, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooh, P. , Jury, V., Laurent, S., Audiat-Perrin, F., Sanaa, M., Tesson V., et al. Control of Biological Hazards in Insect Processing: Application of HACCP Method for Yellow Mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) Powders. Foods 2020, 9, 1528–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Platform of Insects for Food and Feed (IPIFF). Guide on good hygiene practices for European Union producers of insects as food and feed [Internet]. Brussels: IPIFF; 2022 [cited 2025 ]. Available from: https://ipiff. 12 May.

- EFSA Scientific Committee. Risk profile related to production and consumption of insects as food and feed. EFSA J. 2015, 13, 4257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, H.A. , Menjura Rojas, E.M., Barragán Fonseca, K.B., Vásquez Mejía, S.M. Implementation of the HACCP system for production of Tenebrio molitor larvae meal. Food Control, Available from, 1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO, WHO. General principles of food hygiene. Codex Alimentarius Code of Practice No. CXC 1-1969. Rome: Codex Alimentarius Commission; 2023. Available from. [CrossRef]

- International Platform of Insects for Food and Feed (IPIFF). Guide on Good Hygiene Practice. 2022. Available from: https://ipiff.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/IPIFF-Guide-on-Good-Hygiene-Practices.

- International Platform of Insects for Food and Feed (IPIFF). Guide on Good Hygiene Practice: For European Union (EU) producers of insects as food and feed. 2024.

- Wallace, C. A. , & Mortimore, S. E. Chapter 3 - HACCP. Lelieveld, H., Holah, J. and Gabrić, D. In Handbook of Hygiene Control in the Food Industry. 2016. A volume in Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition Second Edition. Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario - ICA. Resolución 061252 de 2020. 2020. Available from: https://www.ica.gov. 2020.

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. Section 2 - Recommended international code of practice - General principles of food hygiene. Fao.org. /: from: https, 8088.

- Codex Alimentarius Commission. Directrices para la validación de medidas de control de la inocuidad de los alimentos cac/GL 69-2008. Editing changes in 2013. Available from: https://www.fao.

- Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Compliance guideline: HACCP systems validation. Washington (DC): FSIS; /: Available from: https.

- Kamau, E. , Mutungi, C., Kinyuru, J., Imathiu, S., Tanga, C., Affognon, H., et al. Moisture adsorption properties and shelf-life estimation of dried and pulverized edible house cricket Acheta domesticus (L.) and black soldier fly larvae Hermetia illucens (L. ). Food Research International 2018, 106, 420–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unión Europea. Reglamento (UE), 3: del Parlamento Europeo y del Consejo. Available from: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/ES/ALL/?uri=CELEX, 3201.

- Caligiani, A. , Marseglia, A., Sorci, A., Bonzanini, F., Lolli, V., Maistrello, L., et al. Influence of the killing method of the black soldier fly on its lipid composition. Food Res. Int. 2018, 116, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danieli, P.P. , Lussiana, C., Gasco, L., Amici, A., Ronchi, B. The Effects of Diet Formulation on the Yield, Proximate Composition, and Fatty Acid Profile of the Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens L.) Prepupae Intended for Animal Feed. Animals 2019, 9, 178–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuel, M. , Kreuzer, M., Sandrock, C., Leiber, F., Mathys, A., Gold, M., et al. Transfer of Lauric and Myristic Acid from Black Soldier Fly Larval Lipids to Egg Yolk Lipids of Hens Is Low. Lipids 2021, 56, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroeckel, S. , Harjes, A.G., Roth, I., Katz, H., Wuertz, S., Susenbeth, A., et al. When a turbot catches a fly: Evaluation of a pre-pupae meal of the Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) as fish meal substitute. Growth performance and chitin degradation in juvenile turbot (Psetta maxima). Aquaculture, Available from. [CrossRef]

- Klunder, H.C. , Wolkers-Rooijackers, J., Korpela, J.M., Nout, M.J.R. Microbiological aspects of processing and storage of edible insects. Food Control 2012, 26, 628–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawski, M. , Mazurkiewicz, J., Kierończyk, B., Józefiak, D. Black Soldier Fly Full-Fat Larvae Meal Is More Profitable Than Fish Meal and Fish Oil in Siberian Sturgeon Farming: The Effects on Aquaculture Sustainability, Economy and Fish GIT Development. Animals 2021, 11, 604–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K. , Liu, T., Awasthi, S.K., Duan, Y., Pandey, A., Zhang, Z. Manure pretreatments with black soldier fly Hermetia illucens L. (Diptera: Stratiomyidae): A study to reduce pathogen content. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessa, L.W. , Pieterse, E., Marais, J., Dhanani, K., Hoffman, L.C. Food Safety of Consuming Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae: Microbial, Heavy Metal and Cross-Reactive Allergen Risks. Foods 2021, 10, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, U. , Broadbent, J.A., Juhász, A., Karnaneedi, S., Johnston, E.B., Stockwell, S., et al. Comparison of protein extraction protocols and allergen mapping from black soldier fly Hermetia illucens. J. Proteomics 2022, 269, 104724–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulé, L. , Misery, B., Baudouin, G., Yan, X., Guidou, C., Trespeuch, C., et al. Evaluation of the Microbial Quality of Hermetia illucens Larvae for Animal Feed and Human Consumption: Study of Different Type of Rearing Substrates. Foods 2024, 13, 1587–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacchiarelli, C. , Fratini, F., Puccini, M., Vitolo, S., Paci, G., Mancini, S. Effects of different blanching treatments on colour and microbiological profile of Tenebrio molitor and Zophobas morio larvae. LWT 2022, 157, 113112–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camenzuli, L. , Dam, R.V., Rijk, T.D., Andriessen, R., Van Schelt, J. Tolerance and Excretion of the Mycotoxins Aflatoxin B1, Zearalenone, Deoxynivalenol, and Ochratoxin A by Alphitobius diaperinus and Hermetia illucens from Contaminated Substrates. Toxins 2018, 10, 91–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smet, J. , Wynants, E., Cos, P., Van Campenhout, L. Microbial Community Dynamics during Rearing of Black Soldier Fly Larvae (Hermetia illucens) and Impact on Exploitation Potential. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. from. [CrossRef]

- Delfino, D. , Prandi, B., Calcinai, L., Ridolo, E., Dellafiora, L., Pedroni, L., et al. Molecular Characterization of the Allergenic Arginine Kinase from the Edible Insect Hermetia illucens (Black Soldier Fly). Mol. Nutr. Food Res. from. [CrossRef]

- Diener, S. , Zurbrügg, C., Tockner, K. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens and effects on its life cycle. J. Insects Food Feed 2015, 1, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, M. C. , Islam, M., Sheppard, C., Liao, J., Doyle, M.P. Reduction of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella enterica Serovar Enteritidis in Chicken Manure by Larvae of the Black Soldier Fly. J. Food Prot. 2004, 67, 685–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, M. , Liu, N., Wu, X., Zhang, J., Cai, M. Tolerance and Removal of Four Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Compounds (PAHs) by Black Soldier Fly (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Environ. Entomol. 2020, 49, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorrens, E. , Van Looveren, N., Van MolL., Van Deweyer, D., Lachi, D., De Smet, J., et al. Staphylococcus aureus in Substrates for Black Soldier Fly Larvae (Hermetia illucens) and Its Dynamics during Rearing. Gralnick JA, editor. Microbiol. Spectr. from. [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, N.T. , Klein, G. Microbiology of processed edible insect products – Results of a preliminary survey. International Food Microbiol. 2017, 243, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grisendi, A. , Defilippo, F., Lucchetti, C., Listorti, V., Ottoboni, M., Dottori, M., et al. Fate of Salmonella enterica Typhimurium and Listeria monocytogenes in Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae Reared on Two Artificial Diets. Foods 2022, 11, 2208–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, C. E. , Taipe, G. L. Inocuidad de Biomasa de Larva de Mosca para uso Pecuario Sostenible. Ecuador. Universidad Técnica de Cotopaxi; 2019. Available from: https://repositorio.utc.edu. 5621. [Google Scholar]

- Hafez, H.H. , EL- A, Hamed, G.H. Studies on the effect of aluminum, aluminum foil and silicon baked cups on aluminum and silicon migration in cakes. Egypt. J. Agric. Res. 2018, 96, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konieczna, A. , Rutkowska, A., Rachoń, D. Health risk of exposure to Bisphenol A (BPA). Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. /: Available from: https, 2581. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, Y. Potential Pro-Tumorigenic Effect of Bisphenol A in Breast Cancer via Altering the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers 2022, 14, 3021–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larouche, J. , Deschamps, M.H., Saucier, L., Lebeuf, Y., Doyen, A., Vandenberg, G.W. Effects of Killing Methods on Lipid Oxidation, Colour and Microbial Load of Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) Larvae. Animals 2019, 9, 182–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. , Yang, X., Mai, L., Lin, J., Zhang, L., Wang, D., et al. Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Bacillus subtilis and Aspergillus niger in Black Soldier Fly Co-Fermentation. Fermentation 2022, 8, 593–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyet, M. , Morrill, H., Espinal, D.L., Bernard, E., Alyokhin, A. Early Growth Patterns of Bacillus cereus on Potato Substrate in the Presence of Low Densities of Black Soldier Fly Larvae. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1284–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niermans, K. , Van Hoek, E.F., Van de Fels, H.J., Loon, J.J.A. The role of larvae of black soldier fly and house fly and of feed substrate microbes in biotransformation of aflatoxin B1. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 279, 116449–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K. , Kwak, S., Nam, J., Choi, H., Lee, H., Kim, H. Antibacterial activity of larval extract from the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) against plant pathogens. J Entomol Zool Stud. 2015, 3, 176–179. [Google Scholar]

- Peguero, D.A. , Mutsakatira, E.T., Buckley, C.A., Foutch, G.L., Bischel, H.N. Evaluating the Microbial Safety of Heat-Treated Fecal Sludge for Black Soldier Fly Larvae Production in South Africa. Environ. Eng. Sci. 2021, 38, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J. , Correa, M., Castañeda-Sandoval, L.M.. Bacillus cereus un patógeno importante en el control microbiológico de los alimentos. Rev Fac Nac Salud Pública, from. [CrossRef]

- Saucier, L. , M’ballou, C., Ratti, C., Deschamps, M.H., Lebeuf, Y., Vandenberg, G.W. Comparison of black soldier fly larvae pre-treatments and drying techniques on the microbial load and physico-chemical characteristics. J. Insects Food Feed 2022, 8, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelomi, M. , Wu, M.K., Chen, S.M., Huang, J.J., Burke, C.G. Microbes Associated With Black Soldier Fly (Diptera: Stratiomiidae) Degradation of Food Waste. Environ. Entomol. 2019, 49, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, J. , Park, S.H., Jung, H.J., You, S.J., Kim, B.G. Effects of Drying Methods and Blanching on Nutrient Utilization in Black Soldier Fly Larva Meals Based on In Vitro Assays for Pigs. Animals 2023, 13, 858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tigreros, J.A. , Parra, S., Martínez, Girón, J., Eduardo, L. Diferentes métodos de escaldado y su aplicación en frutas y verduras. Rev Colomb Investig Agroind. 2021, 8, 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Fels-Klerx, H.J. , Meijer, N., Nijkamp, M.M., Schmitt, E., Van Loon, J.J.A. Chemical food safety of using former foodstuffs for rearing black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) for feed and food use. J Insects Food Feed. 2020, 6, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kessel, K. , Castelijn, G., Meijer, N. Investigation of Bacillus cereus growth and sporulation during Hermetia illucens larval rearing. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40912 Available from:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Looveren, N. , Verbaet, L., Frooninckx, L., Van Miert, S., Van Campenhout, L., Vandeweyer, D. Effect of heat treatment on microbiological safety of supermarket food waste as substrate for black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens). Waste Manag. 2023, 164, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitenberg, T. , Opatovsky, I. Assessing fungal diversity and abundance in the black soldier fly and its environment. J Insect Sci. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S. , Shelomi, M. Review of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) as animal feed and human food. Foods 2017, 6, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICONTEC. NTC 3687. Alimentos para animales. Alimento completo para gatos. 2018. Available from: https://tienda.icontec.org/gp-alimentos-para-animales-alimento-completo-para-gatos-ntc3687-2018.

- European Union. Regulation (EC) No 2002/32 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 7 May 2002 on undesirable substances in animal feed. Off J Eur Union. 7 May.

- European Union. Commission Regulation (EU) 2021/1317 of 9 August 2021 amending Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 as regards maximum levels of lead in certain foodstuffs. Off J Eur Union. 9 August.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Worldwide regulations for mycotoxins in food and feed in 2003 [Internet]. Rome: FAO; 2004 [cited 2025 ]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/3/y5499e/y5499e02. 7 May.

- Zozo, B. , Wicht, M.M., Mshayisa, V.V., van Wyk, J. The nutritional quality and structural analysis of black soldier fly larvae flour before and after defatting. Insects 2022, 13, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EFSA Statement on the requirements for whole genome sequence analysis of microorganisms intentionally used in the food chain. EFSA Journal, Available from. [CrossRef]

- Santori, D. , Gelli, A., Meneguz, M., Mercandino, S., Cucci, S., Sezzi, E. Microbiological stability of Hermetia illucens meal subjected to two different heat treatments. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2024, 109, 102440–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova, T.A. , Vecherskii, M.V., Khayrullin, D.R., Stepankov, A.A., Maximova, I.A., Kachalkin, A.V., et al. Dramatic effect of black soldier fly larvae on fungal community in a compost. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 102, 2598–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallaire-Lamontagne, M. , Lebeuf, Y., Saucier, L., Vandenberg, G.W., Lavoie, J., Prus, J.M.A., et al. Optimization of a hatchery residue fermentation process for potential recovery by black soldier fly larvae. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104946–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałęcki, R. , Bakuła, T., Gołaszewski, J. Foodborne Diseases in the Edible Insect Industry in Europe New Challenges and Old Problems. Foods 2023, 12, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association for Food Protection. Validation of Antimicrobial Interventions for Small and Very Small Processors: A How-to Guide to Develop and Conduct Validations. Food Prot Trends 2013, 33, 95–104. [Google Scholar]

- Kieβling, M. , Franke, K., Heinz, V., Aganovic, K. Relationship between substrate composition and larval weight: a simple growth model for black soldier fly larvae. J. Insects Food Feed 2023, 9, 1027–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Description |

|---|---|

| Product name | Black Soldier Fly Larvae Meal (Hermetia illucens) |

| Raw materials (origin) | Final-instar larvae and prepupae of H. illucens provided by Insect Farming Technologies – EntoPro (La Miel Farm, Ibague municipality, Tolima, Colombia), reared on a substrate of cassava waste, carrot waste, guava flour, wheat bran, and coffee cherry. |

| Ingredients and additives | Citric acid (5%) added as an antioxidant during the blending stage. No other additives were used. IPIFF has not yet approved specific additives for insect feed. |

| Inputs | Food-grade plastic packaging. |

| Proximate composition (% dry matter) | Moisture (%): 7.0 ± 1.7 Dry matter (%): 93.0 ± 0.1 Gross energy: 5966.7 ± 1 kcal/kg Crude protein: 40.7 ± 0.8 Non-protein nitrogen (NPN): 6.5 ± 0.8 Ether extract: 32.7 ± 1.2 Crude fibre: 7.2 ± 4 Ash: 8.4 ± 5 |

| Heavy metal (mg/kg) | Lead (Pb): Not detected * Chromium (Cr) <1.0 Mercury (Hg) <0.02 |

| Microbiological characteristics | Aerobic mesophiles (CFU/g): 15,000 Moulds and yeasts (CFU/g): <100 Sulphite-reducing Clostridium (CFU/g): <10 Coagulase-positive S. aureus (CFU/g): <100 Total coliforms (CFU/g): 340 Escherichia coli (CFU/g): <10 Salmonella spp: Absent |

| Processing and Packaging | Produced via separation, washing, inactivation, blanching, emulsification, laminating, drying, and packaging. These steps enhance physicochemical properties, reduce compaction, and limit microbial contamination. See flow diagram for details. |

| Shelf Life | Under good manufacturing practices (GMP), expected shelf life is 7 months at 25 °C with 5% moisture and 80 μm polyethylene film. At 35 °C, cricket meal shelf life drops 3–4 times, and BSFL powder becomes unsuitable [19]. No shelf-life tests were conducted in the BioInsectonomy project. |

| Preservation | In the BioInsectonomy project, BSFL meal was frozen at –21 °C in triple-layer plastic bags with oxygen barrier and hermetic seal. |

| Regulations | EU Regulation 2015/2283 on novel foods [20]. IPIFF Hygiene Guide (Feb 2024) [13]. Colombia Resolution 061252 (2020) on feed manufacturing/import requirements [15]. |

| Intended Use | Ingredients for balanced animal diets (e.g., feed, pellets); in BioInsectonomy project, used for fish feed. |

| Stage | Hazards | Description | Probability | Severity | Risk | Preventive Control Measures Implemented at CINAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1. Larvae Reception | Biological | Aspergillus spp. | 5 | 4 | High (20) | Use high-quality substrates and potable water throughout. Train personnel in hygiene and handling. Apply strict cleaning and disinfection routines. Remove substrate residues and organic waste to prevent mould growth. Apply thermal treatment at any stage to control fungal contamination. Ensure substrates are mycotoxin-free before processing. |

| Bacillus cereus | 3 | 4 | High (12) | Implement good production (GAP) and manufacturing practices (GMP) from rearing to packaging. Control temperature and humidity. Use high-quality ingredients. Apply thermal treatment during processing. | ||

| Faecal coliforms | 1 | 2 | Low (2) | Maintain strict hygiene and quality control. Ensure potable water, robust cleaning, pest control, and well-maintained facilities. Use quality ingredients. Train personnel in GMP. Conduct regular lab testing. Apply thermal treatment to reduce contamination. | ||

| Total coliforms | 5 | 2 | Moderate (10) | Strict quality and hygiene controls from larval rearing to final packaging. Maintain robust cleaning/disinfection routines, pest control, potable water, and facility integrity. Use high-quality ingredients, reinforce GMP training for staff, and conduct routine lab testing. Apply heat treatment at some processing stage. | ||

| Enterococcus | 3 | 2 | Moderate (6) | Use clean, controlled-origin substrates to reduce initial microbial load. Avoid high-risk substrates like untreated manure. Enforce strict cleaning protocols in the reception area. Apply heat treatment at some stage to control the microorganism. | ||

| Escherichia coli – Shiga toxin | 1 | 5 | Moderate (5) | Ensure optimal hygiene from larval handling to final processing. This includes equipment and surface cleaning, and continuous staff training. Substrates (e.g., manure-based) must be pre-treated or controlled. Perform routine microbiological testing. | ||

| Escherichia coli | 3 | 4 | High (12) | Clean all equipment and surfaces in contact with larvae to prevent recontamination. Use clean, controlled substrates to reduce microbial load. Enforce strict cleaning in the reception area. Implement sorting to discard visibly contaminated larvae. Apply heat treatment to control microorganisms. | ||

| Listeria monocytogenes | 1 | 5 | Moderate (5) | Use substrates from controlled sources, free from known Listeria contamination. Apply pretreatments such as fermentation or thermal methods. Enforce rigorous cleaning protocols for facilities, equipment, and tools. Train staff in safe handling. Conduct frequent microbiological tests on incoming material and finished product. | ||

| Sthapylococcus aureus | 2 | 4 | Moderate (8) | Strengthen operator hygiene and biosecurity. Improve cleaning protocols during larval packaging and transport. Train staff in good handling practices. Implement strict sanitation routines for equipment and facilities. Use physical pest control methods and avoid chemical contamination. Ensure potable water use. Apply thermal treatment. Perform routine microbiological analyses. | ||

| Chemical | Mineral oil hydrocarbons, dioxins, PCBs, and PAHs | 3 | 3 | Moderate (9) | Use only feed-grade substrates free from chemical contaminants and additives. Locate rearing and processing facilities away from industrial or high-traffic areas. Ensure trays, containers, and tools in contact with larvae are made of food-grade materials that do not release chemical residues. | |

| Heavy metals | 2 | 3 | Moderate (6) | Use regulated, low-risk plant-based substrates. Locate facilities away from industrial/agricultural pollution. Conduct regular heavy metal analyses. Implement strict supplier control and traceability systems. Rotate substrates periodically to avoid accumulation. | ||

| Mycotoxins | 2 | 4 | Moderate (8) | Use fungus-free agro-industrial by-products (e.g., free of Aspergillus, Fusarium). Inspect substrates for mould or abnormal odour. Keep processing areas dry and dust-free. | ||

| Pesticides and insecticides | 3 | 4 | High (12) | Enforce strict supplier control. Ensure careful substrate selection to avoid chemical residues. | ||

| Allergens (tropomyosin, arginine kinase, chymosin) | 5 | 2 | Moderate (10) | Train staff on allergen handling and prevention of cross-contamination. Apply thermal blanching to reduce allergenicity. Enforce strict cleaning protocols between batches. Including allergen risk in labelling. | ||

| Physical | Small metal particles | 2 | 3 | Moderate (6) | Establish daily cleaning and inspection of sieves and screens. Train staff to detect wear or corrosion. Replace worn parts. Use high-grade stainless-steel materials | |

| Gravel, stones | 2 | 3 | Medio (6) | Perform visual and tactile checks and fine mesh sieving to remove coarse particles before larval feeding. Establish SOPs for substrate inspection upon entry. Train reception staff in identifying/removing physical contaminants. Maintain equipment (e.g., grinders, conveyors, sieves) regularly. | ||

| Insect parts, pest insects | 2 | 2 | Low (4) | Conduct visual/tactile checks and fine mesh sieving to remove insect parts. Establish SOPs for substrate inspection. Train reception staff to identify and remove physical contaminants. Inspect larvae at reception for pest contamination. | ||

| Plastic fragments and microplastics | 2 | 3 | Moderate (6) | Separate plastic waste from larval feed inputs. Train staff to spot foreign particles. Sieve and inspect substrates. Use approved gloves/aprons that don’t degrade. Regularly inspect tools and facilities for plastic debris. Use filtered water. Avoid single-use plastics. | ||

| Stage 2. Sieving | Biological | Aerobic mesophilic bacteria | 3 | 2 | Moderate (6) | Use substrates from trusted sources. Apply strict cleaning and disinfection protocols in processing areas. |

| Moulds and yeasts | 3 | 2 | Moderate (6) | Maintain clean production areas. Use airtight packaging to avoid moisture. Prefer modified atmosphere or desiccants. Store in cool, cross-contamination-free areas. | ||

| Aspergillus spp. | 3 | 4 | High (12) | Train staff on hygiene and handling to prevent contamination. Use clean work clothing and hand sanitisation (e.g., antibacterial gel). Clean equipment, surfaces, and facilities regularly. Remove organic waste and feed residues to prevent mould growth. | ||

| Total coliforms | 2 | 2 | Low (4) | Use substrates with low microbial load. Apply GMPs and strict hygiene. Ensure robust cleaning/disinfection, access control, and staff training. Dry the meal at high temperatures (>60 °C). Keep humidity low in processing/storage areas. Ensure proper ventilation and apply disinfectant sprays. | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 3 | 4 | High (12) | Strengthen worker hygiene and biosecurity. Reinforce cleaning and disinfection protocols in larval packaging and transport. Strict pest control: seal cracks, install air curtains, use mesh barriers, insect traps, and monitoring devices. | ||

| Chemical | Pesticides (insecticides, herbicides) | 3 | 4 | High (12) | Install physical barriers (closed walls and ceilings) around the sieving area to minimise contamination from neighbouring crop pesticide use. | |

| Physical | Metal fragments and particles | 2 | 3 | Medium (6) | Establish daily cleaning and inspection protocols for sieves. Train staff to visually detect mesh damage. Regularly inspect sieves for wear, corrosion, or breakage. Use stainless steel mesh. Inspect product for metal contamination. | |

| Stage 3. Inactivation | Biological | Non identified | ||||

| Chemical | Non identified | |||||

| Physical | Non identified | |||||

| Stage 4. Transport and Storage at CINAT | Biological | Non identified | ||||

| Chemical | Non identified | |||||

| Physical | Non identified | |||||

| Stage 5. Thawing | Biological | Aerobic mesophilic bacteria | 3 | 3 | Medium (9) | Use substrates from reliable sources. Implement strict cleaning and disinfection protocols for all areas. Maintain constant control of temperature, humidity, and ventilation to avoid bacterial proliferation. |

| Moulds and yeasts | 1 | 2 | Low (2) | Keep production areas clean and with low humidity. Regularly disinfect equipment to avoid contamination. Use pretreated substrates to reduce microbial load. Ensure final moisture content of meal is below 10% to inhibit microbial growth during storage. Apply heat treatment and hermetic packaging in later stages. | ||

| Chemical | Non identified | |||||

| Physical | Non identified | |||||

| Stage 6. Washing | Biological | Sthapylococcus aureus | 1 | 4 | Low (4) | Apply good handling practices, ensuring potable water at all processing sites. Provide robust food safety training to all staff. Reinforce operator biosecurity and hygiene protocols. |

| Chemical | Heavy metals | 2 | 3 | Medium (6) | Install specialised filters (e.g. activated carbon with resin or reverse osmosis). If water quality is uncertain, use distilled, demineralised or purified water for washing. Regularly inspect strainers and utensils for wear or corrosion; replace with stainless steel equipment. | |

| Physical | None identified | |||||

| Stage 7. Draining | Biological | Non identified | ||||

| Chemical | Non identified | |||||

| Physical | Non identified | |||||

| Stage 8. Blanching | Biological | Survival of microorganisms from previous stages | 2 | 3 | Medium (6) | Keep scalding water at 85 °C; calibrate thermometers regularly. Continuously monitor scalding temperature. Ensure cold shock water stays at 4 °C and is clean. Filter or treat water to reduce microbial load. Train staff on time-temperature controls during scalding and chilling. |

| Chemical | None identified | |||||

| Physical | None identified | |||||

| Stage 9. Blending | Biological | Staphylococcus aureus | 2 | 4 | Medium (8) | Train personnel in proper handling of larvae and equipment sanitation during blending. Clean and disinfect blender and tools before each use with effective disinfectants (e.g., hydrogen peroxide or quaternary ammonium). Apply heat treatment afterwards. |

| Salmonella spp. | 3 | 5 | High (15) | Avoid using larvae from animal faeces or faecal-contaminated waste. Train personnel in safe handling and disinfection procedures. Thoroughly clean and disinfect the blender, tools, surrounding surfaces, and nearby equipment before use to prevent cross-contamination. | ||

| Chemical | None identified | |||||

| Physical | Metal fragments and splinters | 1 | 3 | Low (3) | Establish a cleaning and inspection protocol for the blender before and after each production day. Train staff to visually detect blade damage. Regularly inspect blender blades for wear, corrosion, or cracks. Replace blades before reaching critical wear. Use high-quality stainless-steel blades. Conduct regular product inspections to detect metal contamination. | |

| Stage 10. Spreading | Biological | Moulds and yeasts | 1 | 2 | Low (3) | Keep production areas clean and dry. Disinfect equipment regularly. Use hygienic or pretreated substrates to lower initial microbial load. Ensure meal moisture content remains below 10% to inhibit growth. Apply heat treatment afterwards. |

| Chemical | None identified | |||||

| Physical | Aluminium foil particles | 1 | 2 | Low (2) | Avoid using aluminium foil to cover trays. Use food-safe materials like stainless steel trays that are easy to clean and do not shed particles. Prefer non-stick coated trays. Visually inspect foil before each cycle; if damaged, replace with suitable materials. | |

| Stage 11. Drying | Biological | Survivors of previously mentioned microorganisms | 2 | 4 | Medium (8) | Ensure previous steps reduce microbial load: use substrates free of spores, thoroughly clean larvae, maintain strict hygiene in processing areas to prevent cross-contamination, improve air quality in drying area with ventilation, and use additional treatments such as powdered natural antimicrobials, lactic or citric acid. |

| Chemical | Traces of sodium aluminate and aluminium phosphate | 3 | 2 | Medium (6) | Perform strict visual inspection of tray-lining materials before each use to ensure no contamination or damage (e.g., flaking aluminium foil). | |

| Physical | Aluminium foil particles | 2 | 2 | Low (4) | Use non-stick coated trays instead of foil. Inspect trays to ensure no damage or loose materials that may shed during drying. Confirm trays and foil are in good condition (no tears or breaks). Perform a visual inspection before drying to remove any visible contaminants. | |

| Stage 12. Grinding | Biological | Moulds and yeasts | 1 | 2 | Low (2) | Keep production areas clean and dry. Regularly disinfect equipment. Use hygienic or pretreated substrates to lower microbial load. Ensure final meal moisture is below 10% to inhibit growth. Apply heat treatment to eliminate microorganisms without affecting product quality. Use hermetic, moisture- and air-resistant packaging (e.g., modified atmosphere). Store in dry, cool, contamination-free areas. |

| Chemical | None identified | |||||

| Physical | Metal fragments and splinters | 2 | 3 | Medium (6) | Check the blender’s container, blades, screw fittings, and base before each batch. Conduct maintenance of every fixed number of usage hours (e.g., every 20 hours or 30 batches). Replace blades according to the manufacturer’s lifespan recommendations. Control grinding time and batch load to avoid motor strain and excessive vibrations. Use fine sieves or filters after grinding to capture any metal particles. | |

| Stage 13. Packaging | Biological | Moulds and yeasts | 1 | 2 | Low (2) | Keep production areas clean and dry. Regularly disinfect equipment. Ensure the meal is dried to below 10% moisture. Use hermetic packaging that prevents moisture and air entry. Store product in dry, cool areas, free from cross-contamination. |

| Chemical | Bisphenols | 1 | 4 | Low (4) | Ensure packaging materials are BPA-free and food-grade. Avoid contact with old, reused, or deteriorated plastics. Store BSF meal in cool, dry conditions. | |

| Physical | Foreign particles or metal fragments | 1 | 3 | Low (3) | Conduct regular product inspections for metallic contamination. Install a metal detector at the end of the packaging line if possible. | |

| Stage 14. Storage | Biological | Microorganisms viable at freezing temperatures | 1 | 3 | Low (3) | Use high-precision sensors for continuous freezing temperature monitoring. Establish SOPs to prevent fluctuations. Conduct preventive maintenance on freezing equipment and ensure proper function. |

| Chemical | None identified | |||||

| Physical | None identified |

| Stage | Hazard Type | Hazard Description | Significance | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Larvae reception | Biological | Aspergillus spp. | High | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP |

| Bacillus cereus | High | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| Total coliforms | Medium | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| Enterococcus | Medium | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| E. coli – Shiga toxin | Medium | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| E. coli | High | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| Listeria monocytogenes | Medium | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | Medium | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| Chemical | Mineral oil hydrocarbons, dioxins, PCBs, PAHs | Medium | Yes | — | — | — | PRP | |

| Heavy metals | Medium | No | Yes | No | Yes | CCP | ||

| Mycotoxins | Medium | No | Yes | No | Yes | CCP | ||

| Pesticides and insecticides | High | No | Yes | No | Yes | CCP | ||

| Allergens (tropomyosin, arginine kinase, chymosin) | Medium | No | Yes | No | Yes | CCP | ||

| Physical | Metal fragments/splinters | Medium | Yes | — | — | — | PRP | |

| Gravel, stones | Medium | Yes | — | — | — | PRP | ||

| Plastic/microplastics | Medium | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| 2. Sieving | Biological | Aerobic mesophiles | Medium | No | No | Yes | No | PRP |

| Moulds and yeasts | Medium | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| Aspergillus spp. | High | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | High | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| Chemical | Pesticides | High | No | Yes | No | No | PRP | |

| Physical | Metal particles | Medium | Yes | — | — | — | PRP | |

| 5. Thawing | Biological | Aerobic mesophiles | Medium | Yes | — | — | — | PRP |

| 6. Washing | Chemical | Heavy metals | Medium | Yes | — | — | — | PRP |

| 8. Blanching | Biological | Microorganism survival | Medium | No | Yes | Yes | — | PRP |

| 9. Blending | Biological | Staphylococcus aureus | Medium | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP |

| Salmonella spp. | High | No | Yes | Yes | No | PRP | ||

| 11. Drying | Biological | Surviving microorganisms | Medium | No | Yes | No | Yes | CCP |

| Chemical | Sodium aluminate/phosphate traces | Medium | Yes | PRP | ||||

| 14. Grinding | Physical | Metal fragments and splinters | Medium | Yes | — | — | — | PRP |

| Stage | Hazard Type | Critical limits | Monitoring | Corrective actions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | What | How | When | |||

| Stage 1. Larvae reception | Heavy metals | Absence | 0.50 (for crustaceans) Cd: 2 ppm Pb: 10 ppm Hg: 0.1 ppm |

Concentrations of Pb, Cd, Hg, As in mg/kg | Send samples to a laboratory for detection tests | Random batches according to the sampling plan | Reject the affected batch and prevent its use or distribution. Notify the supplier immediately, conduct an audit, and re-evaluate the supplier to ensure compliance with quality and safety standards. Increase the stringency of quality sampling protocols for future batches. |

| Mycotoxins | Absence |

Aflatoxin: 0.02 ppm Ochratoxin A: 5 ppm |

Mycotoxin analysis in substrates (HPLC or ELISA) | Reject the batch and confirm contamination with a secondary analysis. Determine whether the product can be reprocessed or must be destroyed. Investigate the root cause and update preventive measures in the HACCP plan. | |||

| Pesticides and insecticides | Absence | 0.01 mg/kg DDT: 0.2 mg/kg Glyphosate: 300 mg/kg Endosulfan: 0.1 mg/kg Chlorpyrifos: 0.05 mg/kg |

Pesticide residue analysis (GC or HPLC) | Reject the batch, perform confirmatory testing, and decide on reprocessing or destruction. Identify contamination sources and strengthen control strategies in the HACCP plan. | |||

| Allergens (Tropomyosin, Arginine kinase, and Chymosin) | Absence | Gluten: 20 ppm) | Allergen detection tests (ELISA) | If distributed, notify authorities and consider a product recall. Revalidate the allergen control program, evaluate labelling effectiveness, and apply fasting to larvae to reduce allergen levels. Improve the product recall system. | |||

| Stage 11. Drying | Microorganisms identified in hazard analysis and surviving this process | 60°C / 21 hours | 63°C / 21 hours | Process temperature verification | Using a thermocouple installed in the drying oven, connected to monitoring software. Alarm system in place | Each batch | Segregate the batch, test for microbial load, and adjust drying parameters as needed. If the maximum temperature was exceeded, assess product quality. Calibrate thermal equipment to ensure process reliability. |

| CCP | Hazard | Control measure | Critical parameters | Validation factors | Logistical considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larvae reception | Heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Hg, As) | Use of regulated substrates and supplier control | Concentrations of Pb, Cd, Hg, As (mg/kg) | Substrate type; analysis frequency | Accredited laboratories; cost considerations |

| Mycotoxins (Aflatoxins, Ochratoxin A) | Use of fungus-free substrates; visual inspection and frequent testing | Mycotoxin levels (µg/kg) | Substrate type; storage conditions | Environmental control; visual inspection | |

| Pesticides and insecticides | Supplier control; proper substrate selection | Residue levels (mg/kg) | Substrate type; agricultural history | Substrate history; supporting documentation | |

| Allergens | Staff training; proper cleaning between batches; labelling | Presence/absence or ppm level | Allergen types; cleaning effectiveness | Kit availability; staff training | |

| Drying | Microbiological control through thermal processing (60°C for 21 h) | Pre-processing reduction of microbial load; larval cleaning; hygienic processing conditions; ventilation; use of natural antimicrobials and organic acids before drying | Log reduction of pathogens (e.g., Salmonella, E. coli) | Drying temperature/time; use of additional treatments | Temperature and humidity control; equipment availability; staff training |

| Stage | Hazard | Type | What is verified | How | When | Responsible |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Larvae reception | Chemical | Heavy metals | Presence/absence of heavy metals | Randomly select samples from different batches and send them to an accredited lab for testing. Conduct an internal audit programme to review the full HACCP system, including prerequisite programmes, staff training, food safety policies, and food safety culture. |

Quarterly | Quality assistant |

| Mycotoxins (Aflatoxins, Ochratoxin A) | Mycotoxins | Presence/absence of aflatoxins and ochratoxins | Substrate type; storage conditions | Monthly | Quality assistant | |

| Pesticides and insecticides | Pesticides and insecticides | Presence/absence of pesticide and insecticide residues | Substrate type; agricultural history | Quarterly | Quality assistant | |

| Allergens | Allergens (tropomyosin, arginine kinase, chymosin) | Presence/absence of specific allergens | Allergen types; cleaning effectiveness | Monthly | Quality assistant | |

| Drying | Biological | Microorganisms (as identified in hazard analysis) | Proper functioning of the drying oven to eliminate microbial hazards | Drying temperature/time; use of additional treatments | Weekly | Quality assistant and laboratory |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).