1. Introduction

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) have recently emerged as important regulators of gene expression in various organisms, including plants. Unlike linear RNAs, circRNAs possess a covalently closed loop structure, rendering them resistant to exonucleases and exhibiting remarkable stability. While circRNAs have been implicated in diverse biological processes, including development and stress responses, their role in plant-virus interactions remains poorly understood. Viral infections pose significant threats to plant health and agricultural productivity worldwide, making it imperative to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying these interactions.

In this study, we investigate the dynamics of circRNA expression in the plant model system Arabidopsis thaliana (A. thaliana) during viral infections, focusing on different distinct viruses: Turnip rosette virus (TRoV) as a host virus, the small circular satellite RNA of the Lucerne Transient Streak Virus (scLTSV) and Rice yellow mottle virus (RYMV) as a non-host virus. By characterizing changes in circRNA expression profiles and analyzing their potential regulatory functions, we aim to shed light on the intricate interplay between circRNAs and viral pathogens in plants.

We hypothesize that viral RNA influences plant circRNA profiles by potentially modulating regulatory processes, including transcription. We evaluate circRNAs and their predicted impact on the dysregulation of plant cellular genes in response to viral infectious processes. We profile plant circRNAs induced by different plant viruses and circular virusoid RNA, determine which circRNAs react in response to virus infection, viral components, and circular satellite RNAs. We propose that the induced circRNAs could be potentially involved in viral replication, plant defense mechanisms against viruses, and viral disease symptoms. We catalog other virus/viral component-induced circRNAs involved in regulatory functions such as gene transcription, RNA splicing, etc. We examine the impact of the circular satellite RNA of the scLTSV virusoid on the plant endogenous circRNA profile and regulatory processes. We investigate the impact of a non-host virus (RYMV) on the profile and nature of induced plant circRNAs, and finally we determine whether the expression of an exogenous circRNAs, such as a virusoid, influences the expression of endogenous circRNAs in the host plant.

Our study offers a unique contribution to our understanding of plant circRNAs, particularly regarding their interactions in the context of viral infections.

2. Materials and Methods

Host Plant and Virus Model Systems Used in the Current Study

A. thaliana is an ideal host model system for studying circRNAs due to its well-characterized genome, short life cycle, and amenability to genetic manipulation. Furthermore, our understanding of circRNAs in plants, although limited, primarily stems from studies conducted in A. thaliana. TRoV and the scLTSV were chosen as model systems in this study due to their compatibility with A. thaliana. TRoV infects and replicates in A. thaliana, while scLTSV acts as a circular satellite RNA. Additionally, RYMV was selected as a non-host virus to elucidate host-specific responses to viral infections.

Plant Propagation, Inoculation with Virus, RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

A. thaliana seeds were pre-germinated on minimal agar plates (0.8%) for 2 days at 4°C in the dark, followed by growth in a greenhouse under a 16-hour light/8-hour dark cycle at 23°C. Seedlings at the 2-leaf stage with root length approximately 1 mm were transferred to soil. Four-week-old A. thaliana plants were inoculated with TRoV inoculum, and leaves were harvested at 5-, 10-, and 15-18-days post-inoculation to track viral systemic movement.

Total RNA was extracted from healthy and infected A. thaliana plants under RNase-free reaction conditions as specified in (Sambrook & William Russell, 2001). 30 mg of Arabidopsis leaves was used per RNA sample and each sample was subjected to phenol / chloroform extraction using TES buffer (200 mM Tris pH 7.4 and 25 mM EDTA) followed by ethanol precipitation in the presence of 1/10th volume 3M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 2.5 volumes of 95% ethanol. The extracted RNA samples were dissolved in nuclease-free water followed by treatment with DNase for the removal of contaminating genomic DNA as per the following reaction conditions: 15 μl of total RNA, 2.5 μl of 10X reaction buffer, 2 μl of RNase inhibitor (40 units), 1 μl of DNase (2000 units/mL), and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25 μl. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 30 min and subsequently, the DNase was removed by phenol/chloroform extraction followed by ethanol precipitation of the remaining total RNA. The total RNA was dissolved in nuclease-free water, and the purity of the RNA extracts was estimated by measuring the ratio of A260/280 absorption with a Nanodrop-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., USA). Quality and integrity of the RNA were validated by 1% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis using Tris/borate/EDTA (TBE) buffer. Subsequently, RNA samples were subjected to RT-PCR.

Total RNA samples purified as described above (200 ng) were used as templates for cDNA synthesis. A 10 μM reverse primer specific to the 3' end of the coat protein ORF of TRoV (

Table 1) was used for the reverse transcriptase reaction as follows: samples containing the template and primer mixtures were denatured at 75°C for 2 minutes and then quickly chilled on ice for 1-2 minutes. The following reagents were then added to each sample: 2.5 μl of 10x AMV Reverse Transcriptase (RT) buffer (NEB), 1 μl of (10 mM) dNTPs, 1 μl of ribonuclease inhibitor (40 U/μl), and 2.5 μl of AMV RT (200 units) in a 20 μl reaction. The mixture was then incubated for 1 hour at 42°C. Subsequently, 2 μl of the prepared cDNA generated as described above was used as template for the next PCR step wherein it was subjected to PCR amplification to detect the desired PCR product specific for the virus in question. The PCR reaction contained the following components: 12.5 μl of 2x Taq froggamix (PCR master mix), 2 picomoles each of reverse and forward primers, 2 μl of cDNA, and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25 μl. The reaction mix was overlaid with mineral oil and subjected to PCR in a thermal cycler (Illumina Novaseq

TM 6000) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes (1 cycle), followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 45 seconds, annealing at the specific primer annealing temperature for 45 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 1 minute, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 minutes (1 cycle). After amplification, PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis.

Total Plant Protein Extraction, SDS-PAGE and Western Analysis

0.15g of Arabidopsis leaf (fresh) samples were added to autoclaved mortars with liquid nitrogen and ground to a fine powder. The powder was transferred to Eppendorf tubes containing 200 μl protein extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 15 mM MgCl2, 18% glycerol, 0.1 mM PMSF, 7M urea, 2% Triton X-100, and 0.5% NP40). Samples were thoroughly mixed by vortexing and then heated with 5x SDS-PAGE loading dye to 90-100°C for 7 minutes. The samples were permitted to equilibrate to room temperature for a few minutes before loading. Estimation of total protein concentrations was performed using Bradford assay.

SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (PAGE) was conducted using a 4-20% glycine precast gel (BioRad), as specified in Sambrook et al., 2001. A volume of 35 μl of each prepared sample, containing between 14.35 µg and 17.15 µg of protein based on the Bradford assay, was loaded into each well. The gel was subsequently subjected to electrophoresis under a constant voltage of 200V for a duration of 50 minutes. Subsequent to SDS-PAGE, the protein samples were transferred onto nitrocellulose membrane as per the procedure stated in Sambrook et al., 2001. 1:1000 dilution of the primary antibody sample raised in rabbits was used followed by treatment with 1:3000 dilution of the goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody conjugated to alkaline phosphatase. Detection was performed by incubation with alkaline phosphatase substrate solution in the dark for 3-5 minutes.

Methodology for Observation of Morphological Symptoms A. thaliana Plants in Response to Viral/Viral Component Infection

Analyses of A. thaliana symptoms were conducted to monitor plant growth and discern morphological distinctions among three different groups: healthy, transgenic, and infected plants. All plants were simultaneously grown under the same conditions. First, all seeds were grown on 1/2 x MS medium plates for germination and placed in the growth chamber with 16 hours of light and a 22°C growth chamber program. Once the plants developed roots, they were transferred to soil. Then, the plants were examined under the magnifying stereo microscope to capture images and identify any visible symptoms. Additionally, plant height was measured across six different plants for each sample.

3. Bioinformatic Analysis

Library Construction and Sequencing by LC Sequencing Company

Total RNA was extracted from Arabidopsis leaves, and its quantity and purity were assessed using the Bioanalyzer 2100 with an RNA 6000 Nano LabChip Kit (Agilent, CA, USA). Only samples with an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) greater than 7.0 were used for further processing. Approximately 5 μg of total RNA underwent ribosomal RNA depletion following the Ribo-Zero Plant Removal Kit (Illumina, CA, USA) protocol. The remaining RNA was treated with RNase R (Epicentre Inc, Madison, WI, USA) at 37°C for 30 minutes to remove linear RNAs, thus enriching for circular RNAs (circRNAs). The enriched circRNA fractions were then fragmented using the NEBNext® Magnesium RNA Fragmentation Module (NEB, USA). The fragmented RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript™ II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, USA). The second strand was synthesized using E. coli DNA polymerase I (NEB, USA), RNase H (NEB, USA), and a dUTP solution (Thermo Fisher, USA). An A-base was added to the blunt ends to facilitate adapter ligation. Single- or dual-index adapters with T-base overhangs were ligated to the A-tailed DNA fragments, and size selection (300-600 bp) was performed using AMPureXP beads. The ligated products were PCR amplified under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 minutes, followed by 8 cycles of 98°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 15 seconds, and 72°C for 30 seconds, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes. The average insert size was 300±50 bp. The cDNA library was then sequenced using the Illumina Novaseq™ 6000 platform, generating 2×150 bp paired-end reads.

Initial sequencing produced millions of paired-end reads, which were filtered using Cutadapt (version: cutadapt-1.9) to remove adapter sequences, polyA/polyG stretches, reads with more than 5% unknown nucleotides (N), and reads with more than 20% low-quality bases (Q-value ≤ 20). Sequence quality metrics, including Q20, Q30, and GC-content, were evaluated using FastQC (version 0.11.9). Filtered reads were mapped to the Arabidopsis genome using Bowtie2 and Tophat2 (version 2.0.4). Unmapped reads were further analyzed with Tophat-fusion (version 2.1.0) to identify back-splicing junctions indicative of circRNAs. De novo assembly of mapped reads into circRNAs was performed using CIRCexplore2 (version 2.2.6) and CIRI (version 2.0.2). Differential expression analysis was conducted using the R package edgeR. CircRNA expression levels were estimated using the number of back-spliced reads, normalized as spliced reads per billion mappings (SRPBM). Twelve circRNAs were selected for qPCR validation based on their relevance in plant development and virus infection. Each 10 μl qPCR reaction contained 2 μl cDNA (50 ng), 400 nM primer mix, 2 μl nuclease-free water, and 5 μl of 2× Luna Universal qPCR Master Mix (NEB, USA) SYBER green. Real-time RT-PCR was performed to compare expression levels across different plant lines and infection conditions.

Bioinformatics Software Used.

| Analysis Item |

Software |

Version |

| Quality control |

FastQC |

0.10.1 |

| Adapter removal |

Cutadapt |

1.10 |

| Genome mapping |

Tophat |

2.0.4 |

| Back-splicing junction reads filter |

Tophat-fusion |

2.1 |

| circRNA identification |

CIRCexplore, CIRI |

2.2.6, 2.0.2 |

| Differential expression analysis |

edgeR |

NA |

| Interaction with miRNA |

Targetmimics |

NA |

This comprehensive approach ensured the accurate identification and quantification of circRNAs, facilitating subsequent functional analyses.

circRNA Classification Based on Genomic Origins

CIRCexplore and CIRI, renowned circRNA detection tools, were utilized in this study. CIRCexplore employs unmapped reads from Tophat processed through Tophat-fusion (version 2.1) to identify back-splice junction reads, while CIRI2 specializes in datasets containing circRNA species. Both tools were used to detect circRNAs, leveraging their respective strengths. Tophat version 2.0.4 aligned reads to the reference genome (

www.plants.ensembl.org), followed by de novo assembly of circRNA reads using CIRCexplore version 2.2.6. Back-splicing junction reads were identified among unmapped reads using TopHat-Fusion and CIRCexplore. Each sample yielded unique circRNAs. Categorization included circRNAs from exonic regions designated as circRNAs, those from intronic regions labeled as ciRNAs, and those from intergenic regions designated as intergenic circRNAs.

4. Results Obtained

Symptom Development in A. thaliana Plants Due to Viral Infection

Our investigation began with an assessment of symptom development in A. thaliana plants infected with TRoV (host), plants transgenic for TRoV capsid protein gene (CP-TRoV), and plants transgenic for the RYMV genome (non-host). Observations of plant morphology revealed notable differences between healthy and infected/transgenic plants. CP-TRoV transgenic plants exhibited reduced height compared to healthy controls, with characteristic black spots on leaf edges. TRoV-infected plants displayed stunted growth and leaf discoloration, progressing from white spots at 10 days post-inoculation (dpi) to purple spots and dry leaves by 15 dpi. Transgenic circ-LTSV and RYMV-infected plants with TRoV showed no visible symptoms but exhibited variations in plant height compared to controls. Having observed the above symptoms, we proceeded to investigate the circular RNA profiles of these plants to identify their putative molecular interactions in the context of viral infection.

Constructs Prepared in the Current Study

Detailed procedures for construct preparation, including cloning of CP-TRoV, RYMV, and circ-LTSV genes into binary vectors, are provided in the Supplementary Section. Successful cloning for each of the above constructs was confirmed through rigorous validation steps documented in the supplementary material.

Detection of CP-TRoV, RYMV, and circ-LTSV Genes in Transgenic A. thaliana Plants

Total RNA was extracted from transgenic A. thaliana plants expressing CP-TRoV, RYMV, or circ-LTSV genes. RNA integrity was verified, and time-course experiments revealed the early presence of TRoV in the TRoV-infected plants, with RT-PCR confirming viral gene expression.

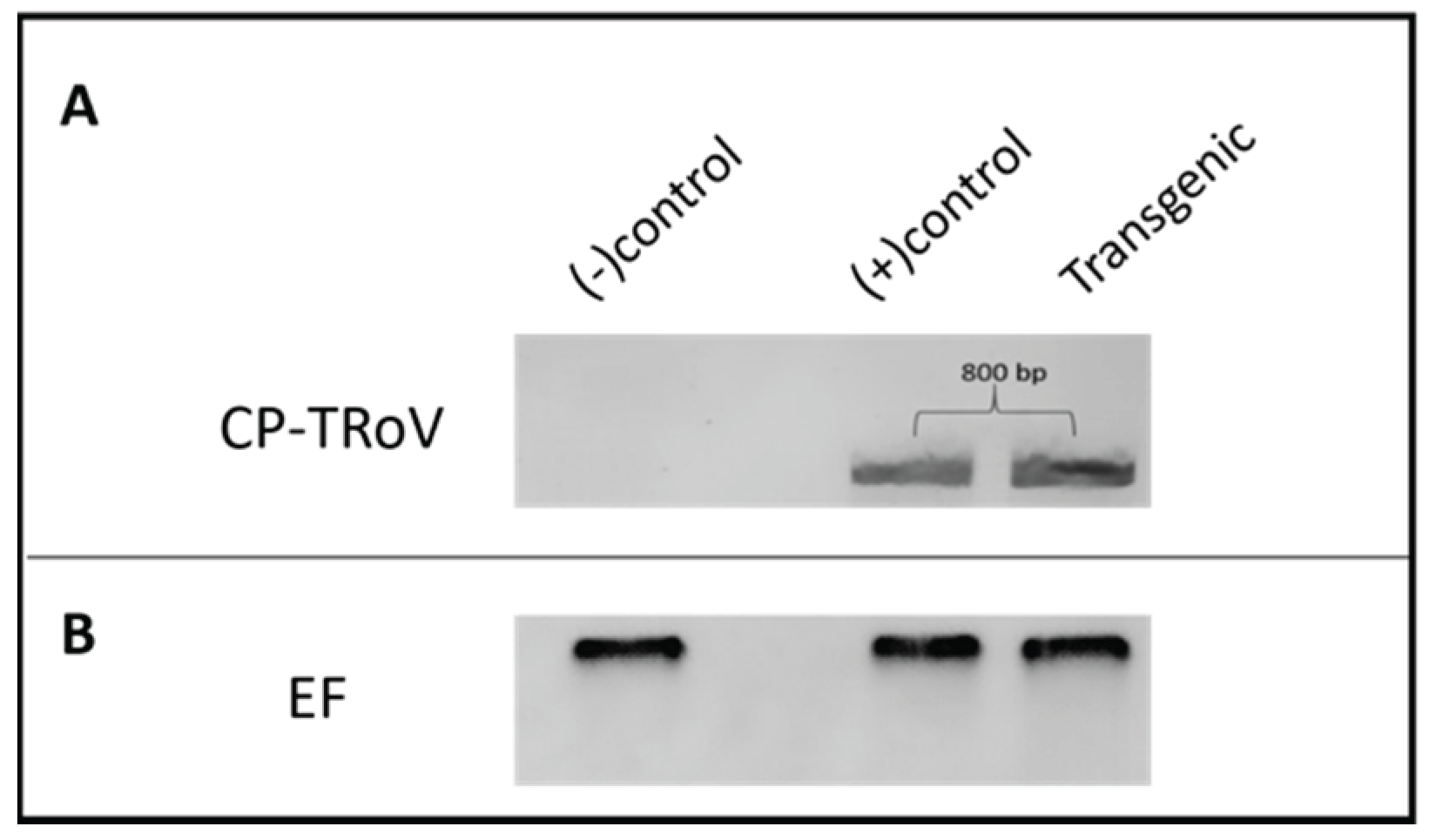

Presence of CP-TRoV in Transgenic CP-TRoV A. thaliana

To validate the presence of the CP-TRoV transgene in transgenic

A. thaliana plants, an RT-PCR experiment was conducted (

Figure 1). Forward primer (CP-TRoV_F) and reverse primer (CP-TRoV_R) specific to the CP gene were utilized for PCR amplification (

Table 1). An 800-base pair (bp) product was detected exclusively in the transgenic plants, indicating the successful integration of the CP-TRoV transgene into the

A. thaliana genome. In contrast, healthy

A. thaliana plants (negative control) did not exhibit the presence of the 800 bp band. As a positive control, TRoV-infected

A. thaliana plants yielded an RT-PCR product at the expected size (800 bp). These results confirm the intact expression of CP mRNA under the control of the 35S CaMV promoter in the pBI121 vector, in which it was cloned. Elongation factor was employed as a loading control to ensure the accuracy of the RT-PCR results.

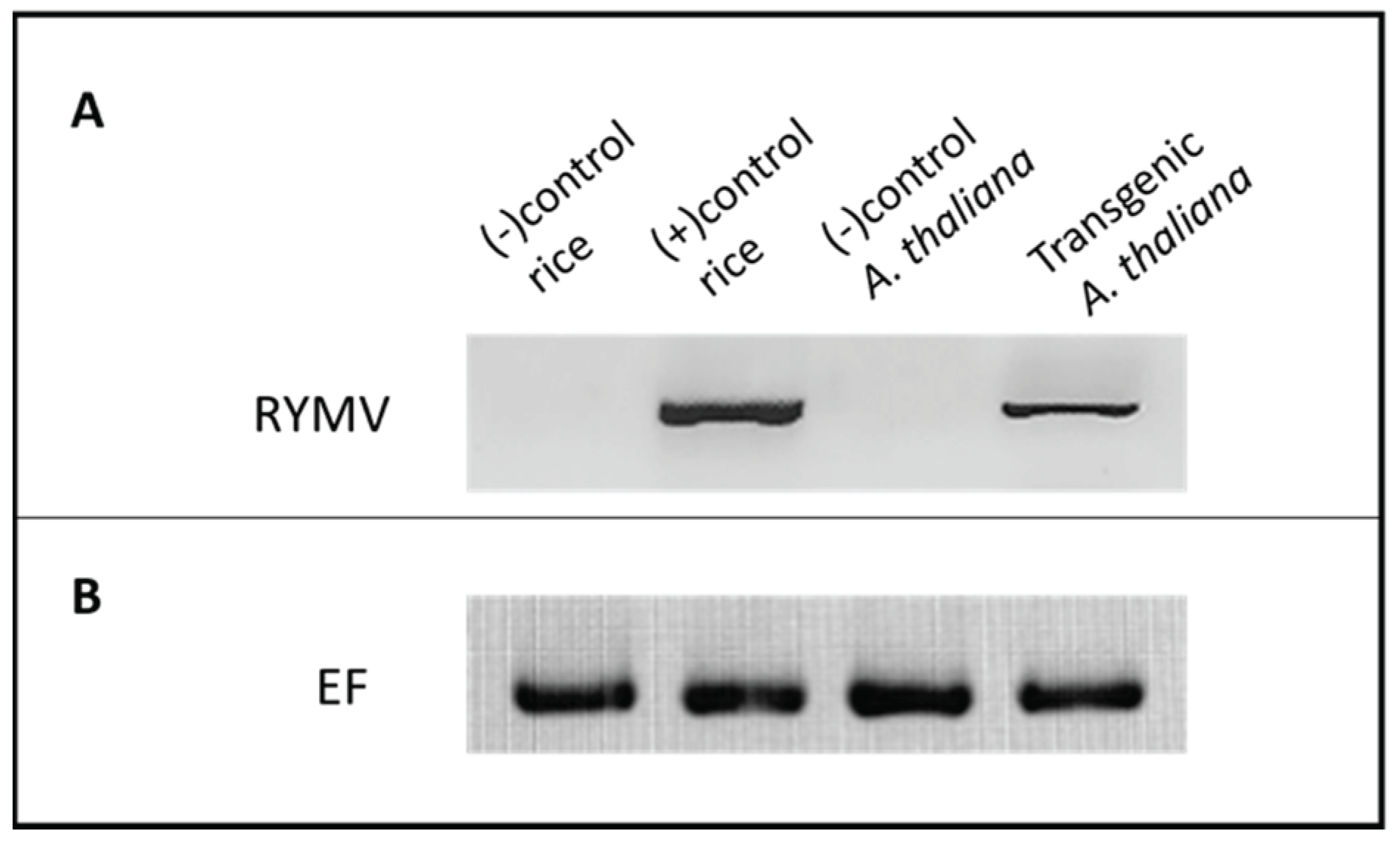

Presence of Genomic RYMV Transgene in RYMV Transgenic A. thaliana

An RT-PCR experiment was conducted to verify the presence of the genomic RYMV transgene in transgenic

A. thaliana plants (

Figure 2). Forward primer (CP-RYMV_F) and reverse primer (CP-RYMV_R) specific to the CP-RYMV gene were employed for PCR amplification (

Table 1). A 720-base pair (bp) product was detected exclusively in the transgenic plants, indicating the successful integration of the genomic RYMV transgene into the

A. thaliana genome. In contrast, healthy

A. thaliana plants (negative control) did not exhibit the presence of the 720 bp band. Similarly, healthy rice plants (negative control) did not demonstrate the presence of the 720 bp band. As a positive control, RYMV-infected rice plants yielded an RT-PCR product at the expected size (720 bp).

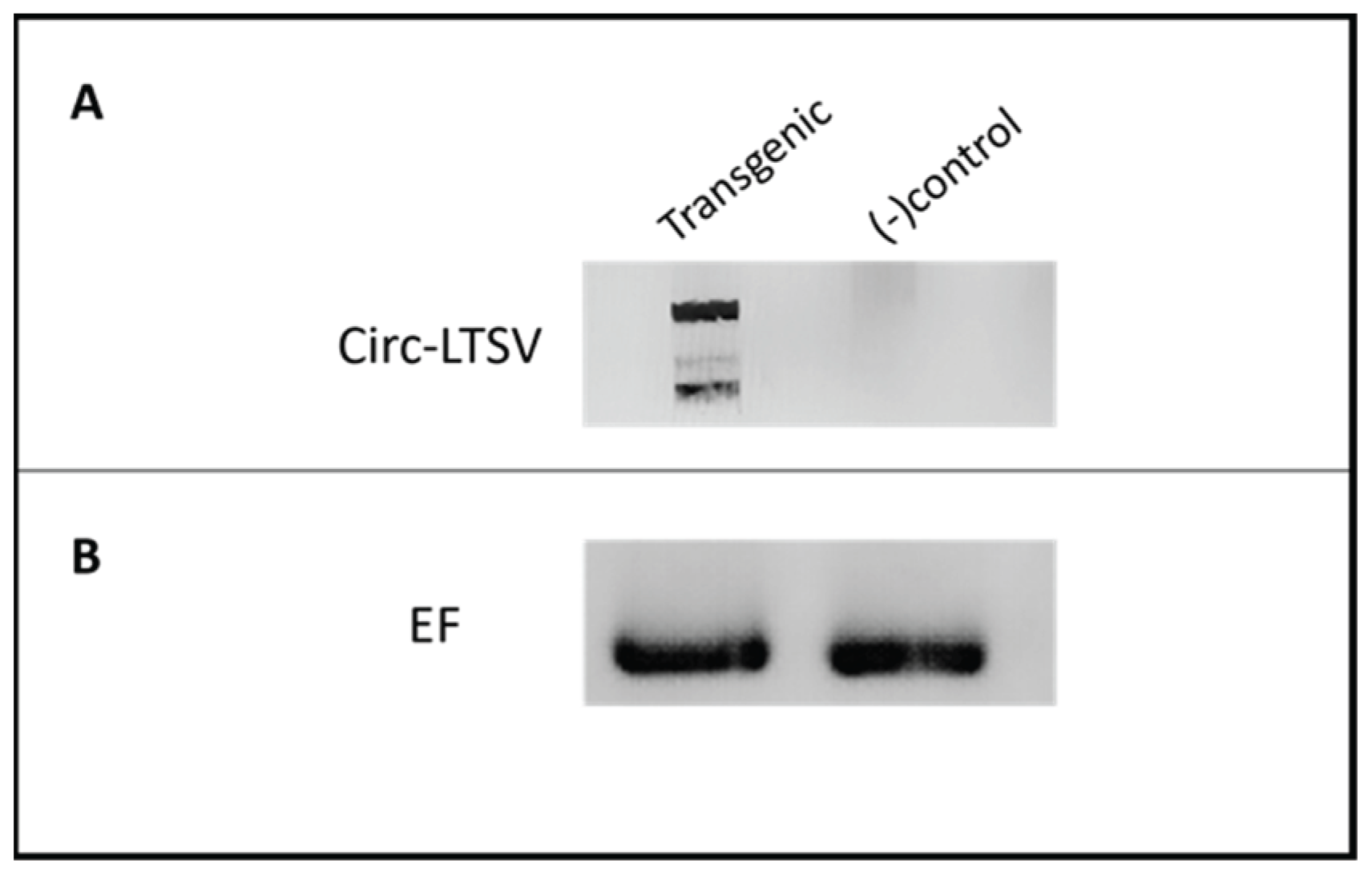

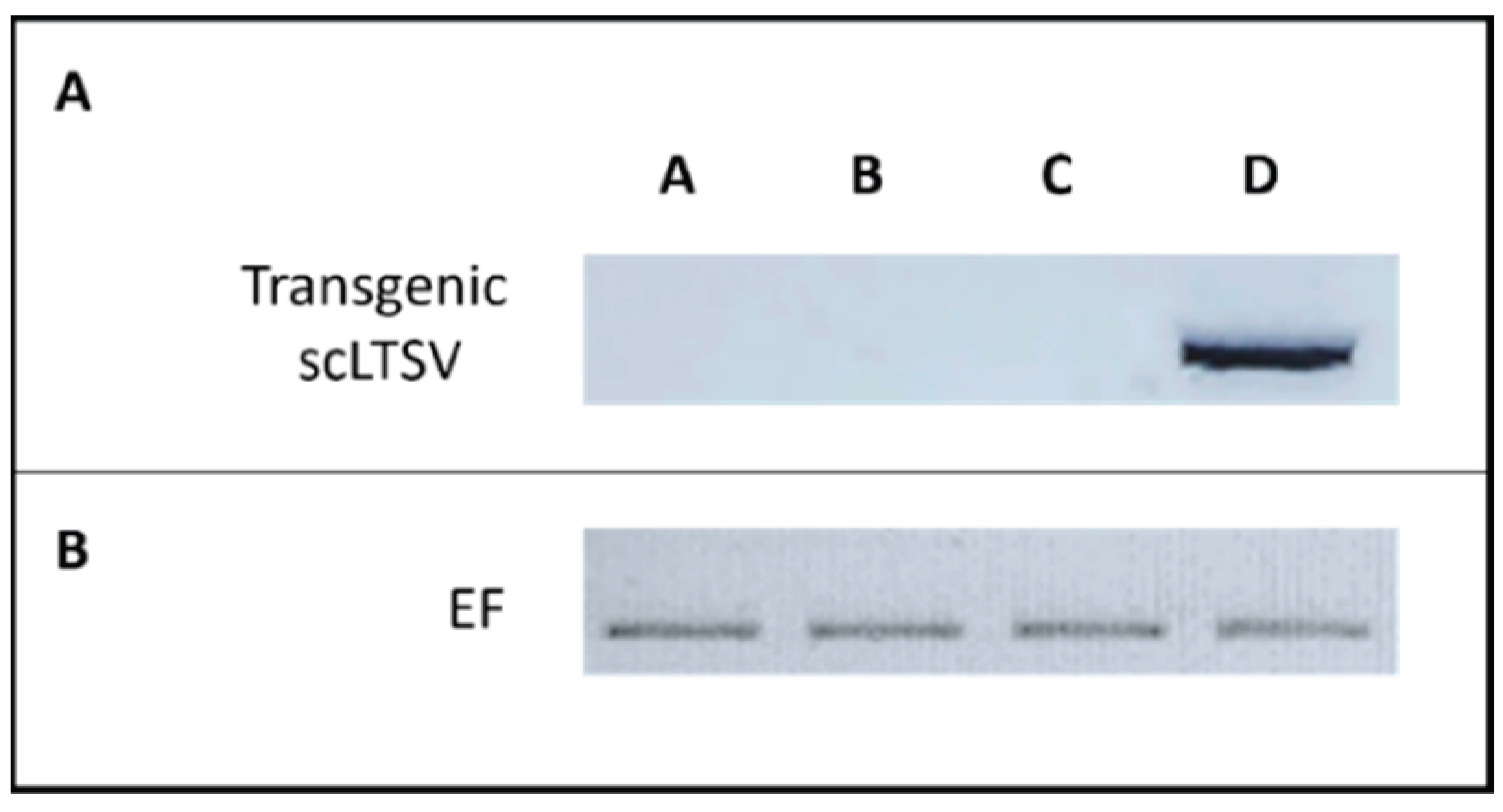

Confirmation of Circular scLTSV (circ-LTSV) in Transgenic A. thaliana Infected with TRoV

An RT-PCR experiment was conducted to verify the presence of head-to-tail circ-LTSV in transgenic

A. thaliana plants infected with TRoV (

Figure 3). Forward primer (circ-LTSV-F) and reverse primer (circ-LTSV-R) specific to circ-LTSV were utilized for PCR amplification (

Table 1). A 322-base pair (bp) product corresponding to circ-LTSV was detected in transgenic

A. thaliana plants infected with TRoV as well as in positive control samples. Additionally, bands at 522 bp and 844 bp were observed, representing concatamers resulting from the production of circ-LTSV dimer and trimer forms at 322 bp intervals due to the rolling circle replication of scLTSV. The presence of a head-to-tail dimer of sc-LTSV is crucial and a minimum requirement for expressing the circular scLTSV genomic RNA in transgenic plants, facilitated by its self-cleaving ribozyme action through rolling circle replication (Abouhaidar & Paliwal, 1988). Hence, cloning of dimer sc-LTSV was preferred over the monomer form. Elongation factor was used as a loading control to ensure the accuracy of the RT-PCR results.

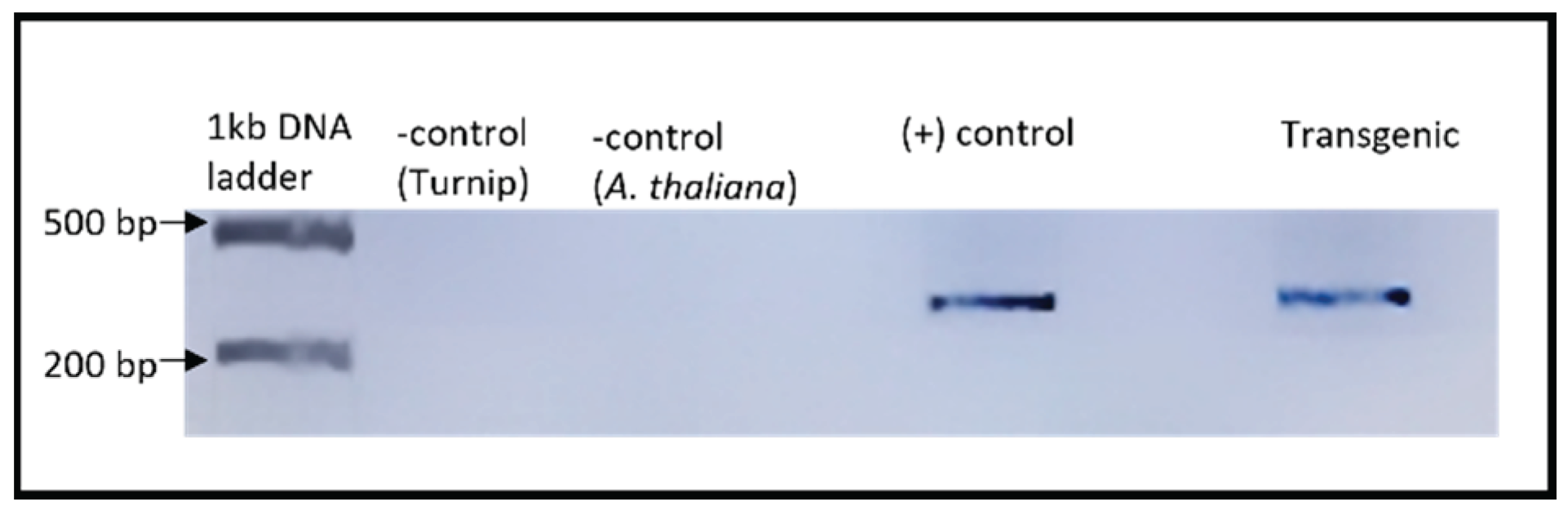

Confirmation of scLTSV (circ-LTSV) in Transgenic A. thaliana

An RT-PCR experiment was conducted to verify the presence scLTSV in transgenic

A. thaliana plants (

Figure 4). Forward primer (LTSV_sat_F) and reverse primer (LTSV_sat_R) specific to sc-LTSV were utilized for PCR amplification (

Table 1). A 322-base pair (bp) product corresponding to scLTSV was detected in transgenic

A. thaliana plants as well as in positive control samples.

Confirmation of the Absence of CP-TRoV in scLTSV Transgenic A. thaliana

Since the scLTSV transgenic were generated using a construct harboring both CP-TRoV and scLTSV, an RT-PCR experiment was conducted to verify the absence of CP-TRoV in sc-LTSV transgenic

A. thaliana plants (

Figure 5). Forward primer (CP-TRoV_F) and reverse primer (CP-TRoV_R) specific to CP-TRoV were utilized for PCR amplification (

Table 1). No 800-base pair (bp) product corresponding to CP-TRoV was detected from the transgenic plants, indicating the absence of CP-TRoV in the scLTSV transgenic

A. thaliana. As expected, positive control samples (TRoV-infected

Arabidopsis plants) showed a band at the expected size (800 bp). Additionally, scLTSV transgenic

A. thaliana plants and healthy

A. thaliana plants (used as negative controls) did not exhibit the presence of the 800 bp CP-TRoV PCR product. Elongation factor was used as a loading control to ensure the accuracy of the RT-PCR results.

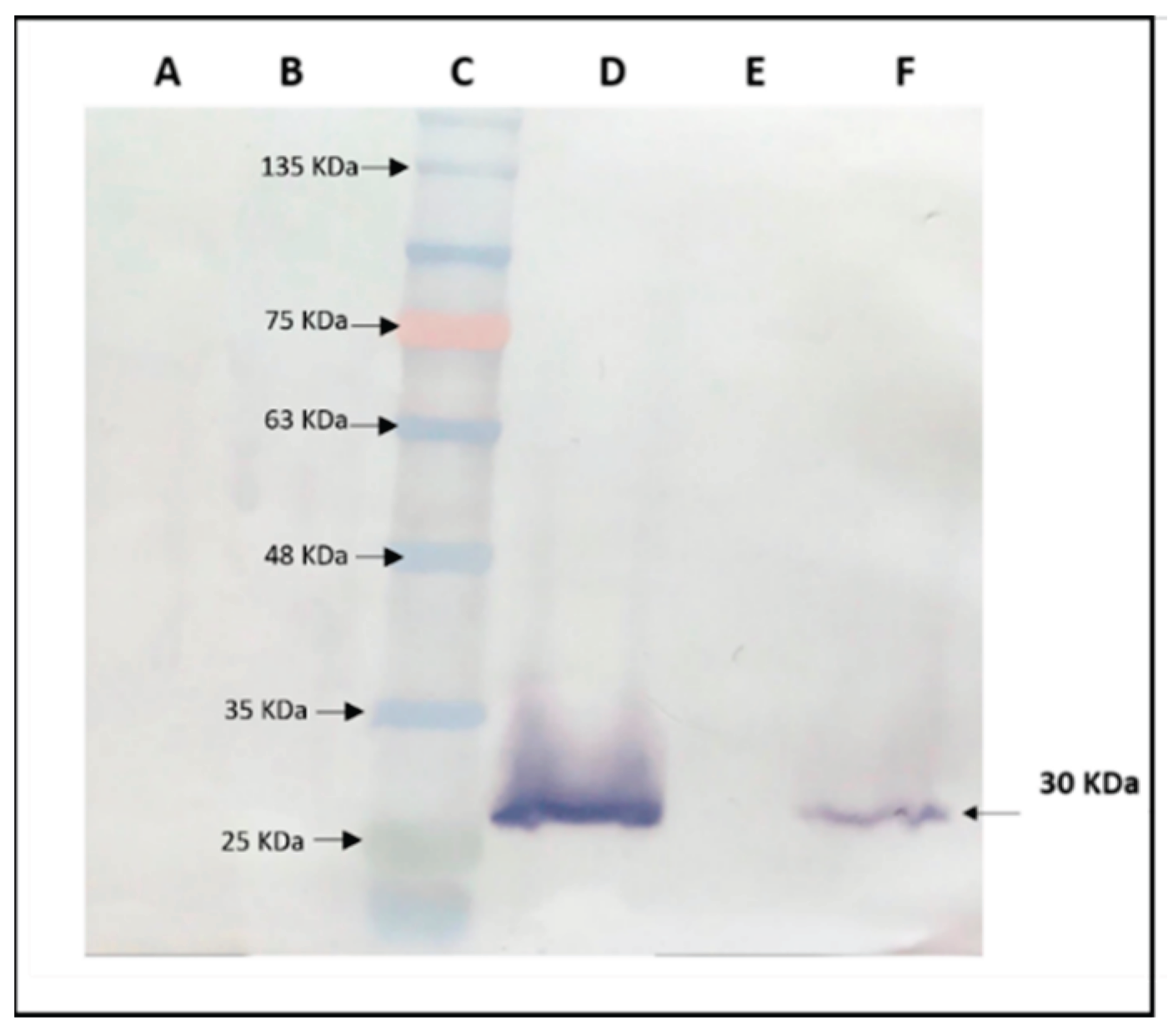

Western Analysis for the Detection of CP Expression in Plants Transgenic for CP-TRoV

A Western blot analysis was conducted to evaluate the expression of the capsid protein (CP) of TRoV in transgenic

A. thaliana plants (

Figure 6). The results revealed the presence of a distinct 30 kDa CP-TRoV band in the virus-infected positive control sample, demonstrating the specificity and efficacy of the TRoV polyclonal antibody in detecting CP-TRoV expression. The Western blot results indicated that the protein extraction method and Western blotting conditions were optimized for accurate detection. Notably, CP-TRoV transgenic

A. thaliana plants also exhibited the CP-specific 30 kDa band, confirming the expression of TRoV capsid protein under the control of the CaMV 35S promoter. In contrast, negative control samples (healthy plants) displayed no equivalent band, further validating the specificity of the CP-TRoV detection.

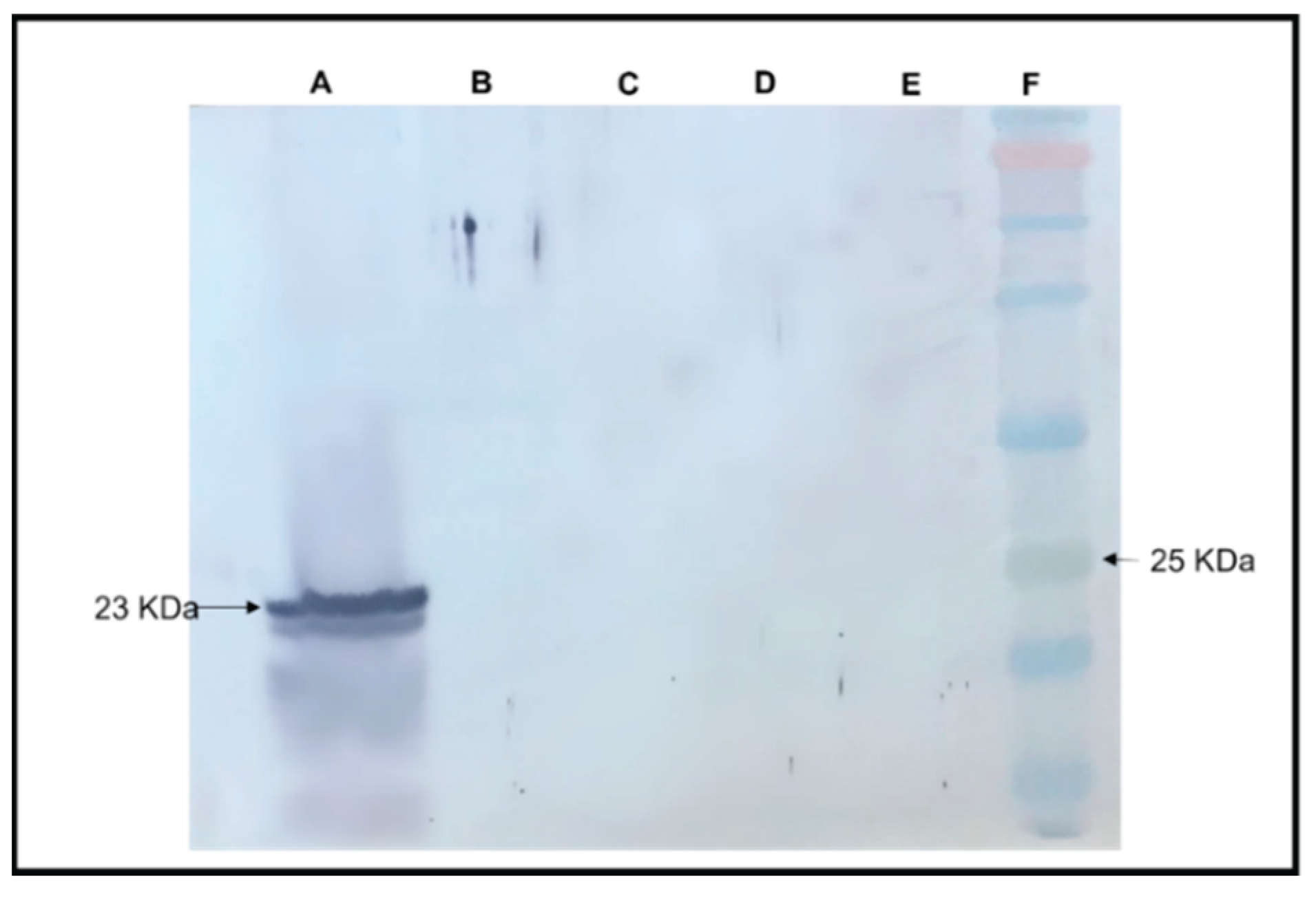

Absence of RYMV Capsid Protein Expression in Transgenic A. thaliana as Demonstrated by Western Analysis

A Western blot analysis was conducted to assess the expression of the Rice yellow mottle virus (RYMV) capsid protein in transgenic RYMV

A. thaliana plants, wherein

A. thaliana servs which serve as a non-host for RYMV (

Figure 7). Protein samples extracted from RYMV transgenic

Arabidopsis plants and RYMV-infected rice plants (used as a positive control) were subjected to Western blotting. The results revealed a specific CP band at 30 kDa in the protein extract from RYMV-infected rice plants, indicative of CP expression and RYMV genome replication in its natural host. In contrast, the protein extract from RYMV transgenic

Arabidopsis plants did not exhibit this CP-specific band, suggesting the absence of RYMV CP-protein expression. This observation implies the lack of RYMV replication in transgenic

Arabidopsis plants, consistent with their status as non-hosts for RYMV. Negative control samples, including protein extracts from wild-typ

e Arabidopsis thaliana and healthy rice plants, displayed no detectable CP band, further validating the specificity of the Western blot analysis.

CircRNA Sequencing

The advent of high-throughput sequencing (HTS) technology has revolutionized transcriptomic analysis by enabling the detection and characterization of various RNA species, including circular RNAs (circRNAs). CircRNAs, being non-polyadenylated RNA molecules, require specialized HTS methodologies for their accurate identification. Notably, the application of linear rRNA depletion strategies, such as RiboZero, has significantly facilitated circRNA sequencing (Salzman et al., 2012). In this study, we conducted comprehensive bioinformatic analyses to explore the potential functions of circRNAs in Arabidopsis plants under different conditions. Differential gene expression analysis, functional annotation, and pathway enrichment analysis were performed to elucidate the roles of circRNAs in response to various stimuli. Additionally, we present the results of circRNA sequencing and bioinformatic analyses, followed by detailed sequence mapping.

Results Obtained from RNA-SEQ Bioinformatic Analyses: Identification and Characterization of circRNAs: Analysis of Circular RNA Abundance Across Samples and GC Content

Analysis of circRNA sequencing data revealed the generation of more than 40 million valid reads for each sample/run of Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. The GC content was approximately 47%, and the Q30 (quality score) exceeded 92%. Using CIRI2, CIRCexplore and the R package edgeR, a total of 760 circRNAs were predicted from the sequencing data. We analyzed the count of circRNAs across all samples, including healthy Arabidopsis thaliana, TRoV-infected plants, and transgenic plants expressing CP-TRoV, scLTSV, and RYMV wherein varying counts were observed.

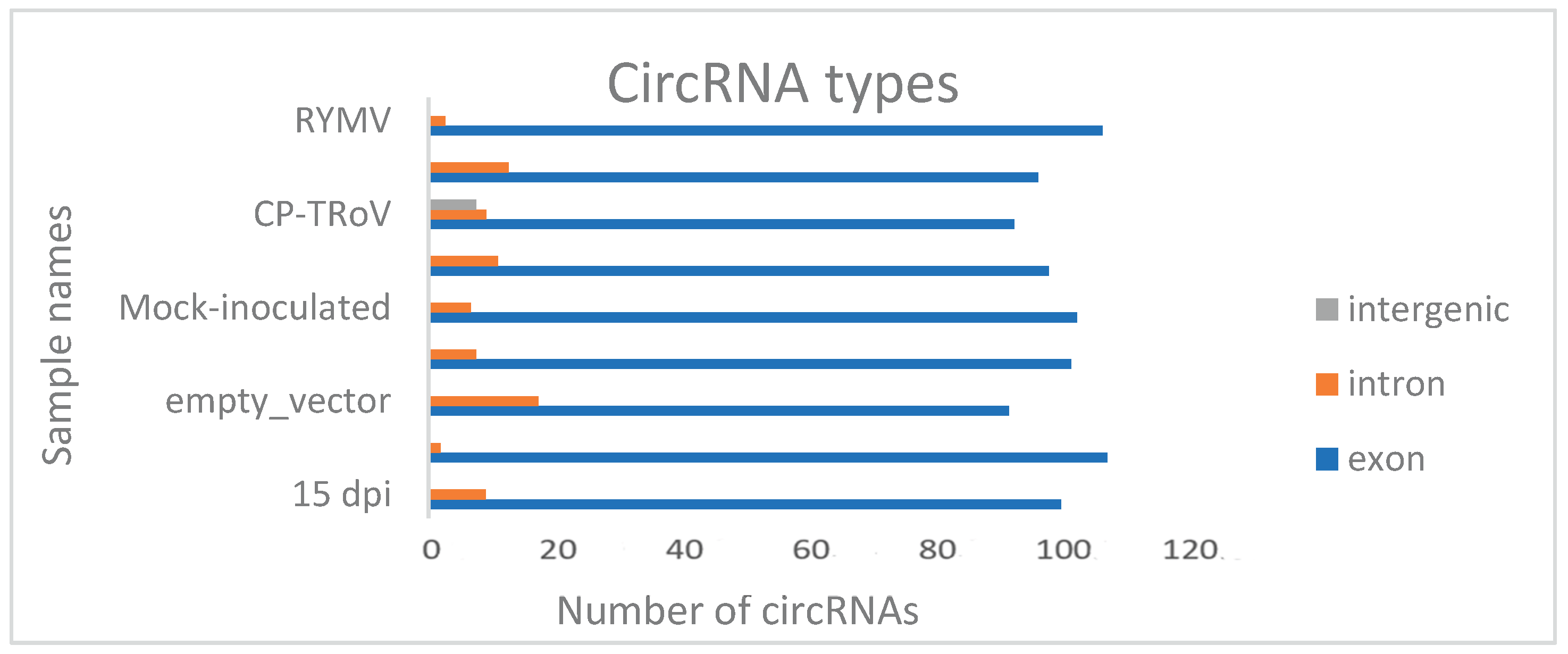

Genomic Distribution of Identified circRNAs

circRNAs were categorized based on their start and end positions in the genome, distinguishing between exonic, intronic, and intergenic origins. Predominantly, circRNAs originated from exons, with fewer arising from introns, suggesting that mRNA-producing regions are primary sources of circRNA generation. Among the samples, empty vector samples exhibited the highest count of genes generating intron circRNAs. In contrast, TRoV-infected, circ-LTSV, CP-TRoV, and control samples predominantly produced circRNAs exclusively from exonic or intronic regions. CP-TRoV uniquely produced intergenic circRNAs among the samples.

Figure 8 shows the approximate number of circRNAs originating from the exonic, intronic and intergenic regions of the plant genome. For instance, RYMV exhibits approximately 16 SRPBM circRNAs from exonic regions and around 3 circRNAs from intronic regions.

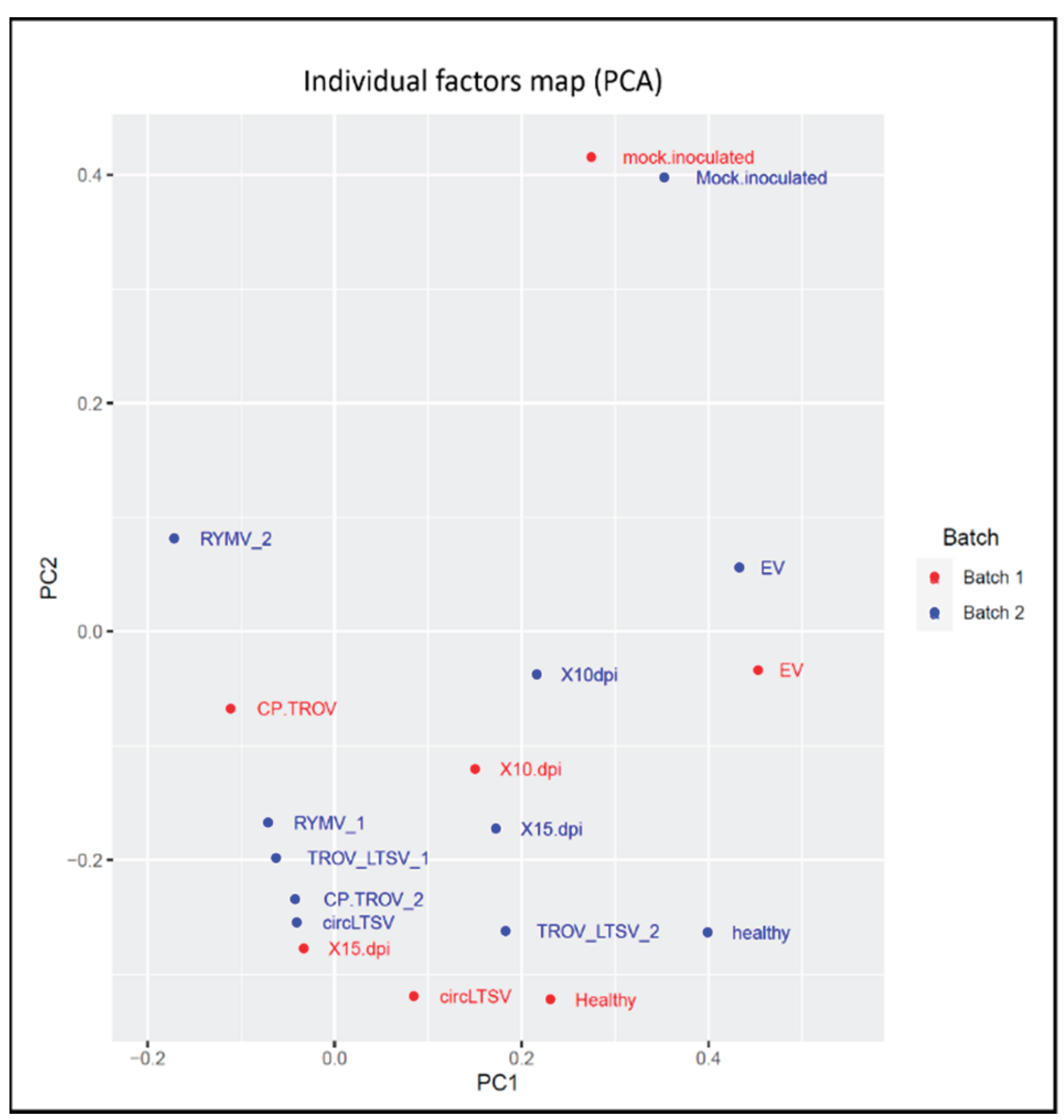

Principal Components Analysis

All samples underwent circRNA sequencing with two replicates, and comparative analysis revealed no significant differences between the two sequencing runs for all nine samples. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted on the normalized RNA-seq data encompassing 760 differentially expressed circRNAs across all nine samples. The resulting PCA plot provides a comprehensive representation of the conditions for all samples, demonstrating consistent representation across the two sequencing runs (

Figure 9). To explore the overall expression patterns and relationships within these samples, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted on the normalized RNA-seq data encompassing 760 differentially expressed circRNAs across all nine samples. The resulting PCA plot (

Figure 9) is instrumental in distinguishing negative controls (healthy, EV, and mock-inoculated samples) from the remaining samples within both batches. Overall, the plot provides a comprehensive representation of the conditions for all samples, demonstrating their consistent representation across the two sequencing runs.

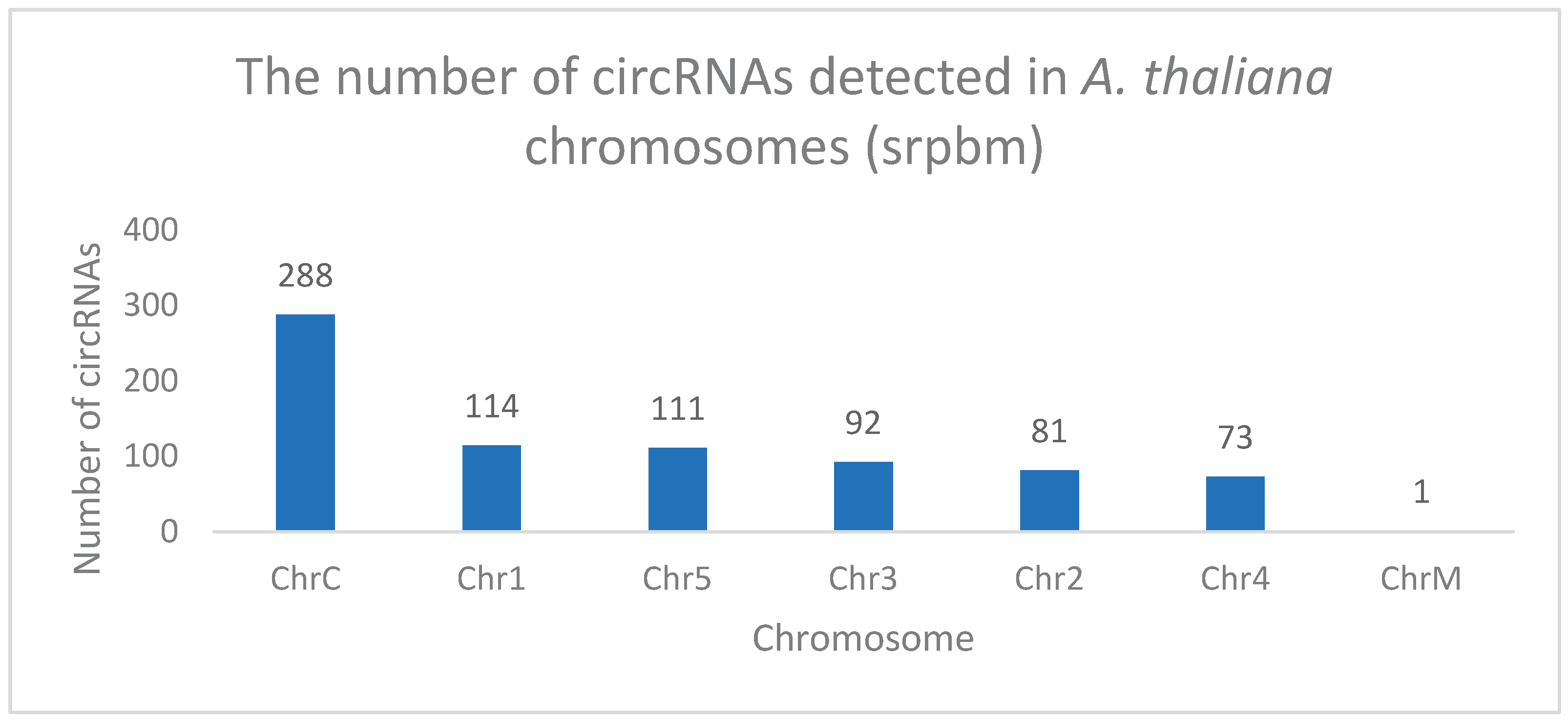

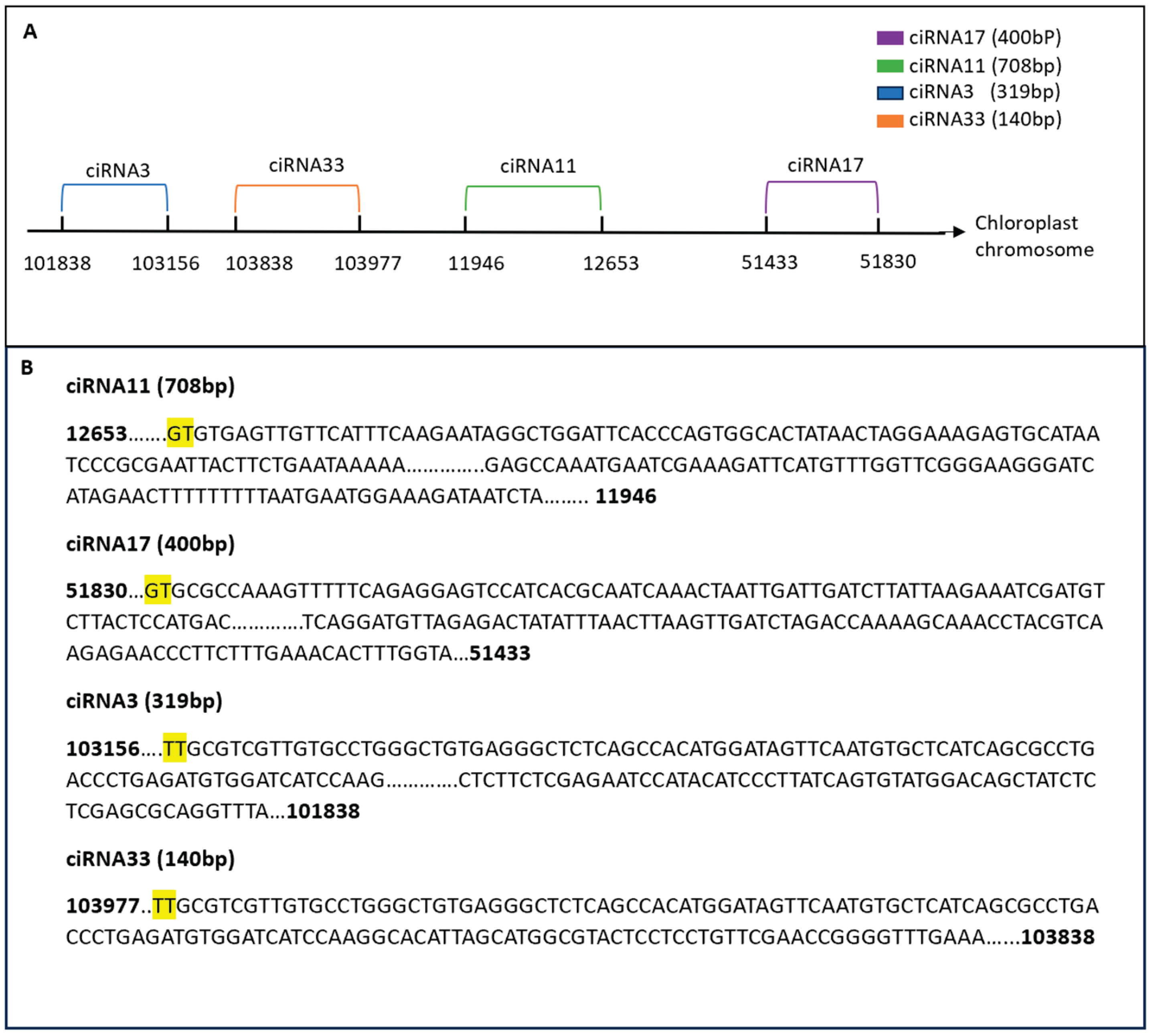

Chromosomal Distribution of circRNAs

Analysis revealed circRNA distribution originating from across chromosomes 1 to 5, with a limited presence in mitochondria (

Figure 10). Notably, the chloroplast chromosome expressed the highest number of circRNAs.

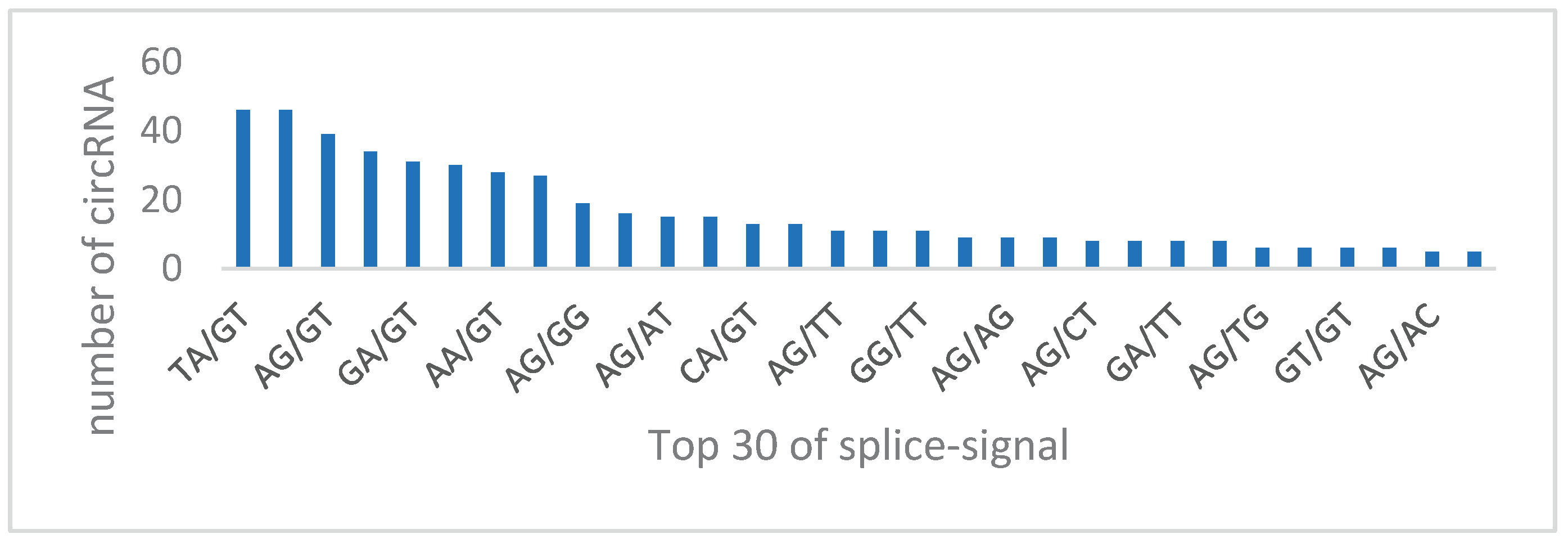

Diversity in circRNA Splicing Signals

The splicing signals at circRNA splice sites in our study exhibited diversity. Unlike the typical GT-AG splicing signal observed in animals, our sequencing results in Arabidopsis presented a variety of splicing signals, such as TA/GT and TT/GT, expressed in terms of AGCT due to the DNA sequencing method used (

Figure 11).

Patterns of circRNA counts

In this study, circRNA counts in each sample were analyzed using the R program version 3.6.3 package ggplot2. Our data revealed diverse circRNA counts across different samples. For instance, ciRNA9 exhibited 30 counts at 15 dpi, decreasing to 10 counts at 10 dpi, while the mock-inoculated sample showed 60 counts. Another circRNA, circRNA2, had 23 counts in the non-host sample (RYMV transgenic A. thaliana) and 100 counts in the host sample (CP-TRoV transgenic A. thaliana). Similarly, ciRNA11 showed varied counts across different samples, with the highest count in the CP-TRoV-scLTSV double transgenic A. thaliana. All samples exhibited zero counts of ciRNA17, while healthy controls showed a high count for this circRNA.

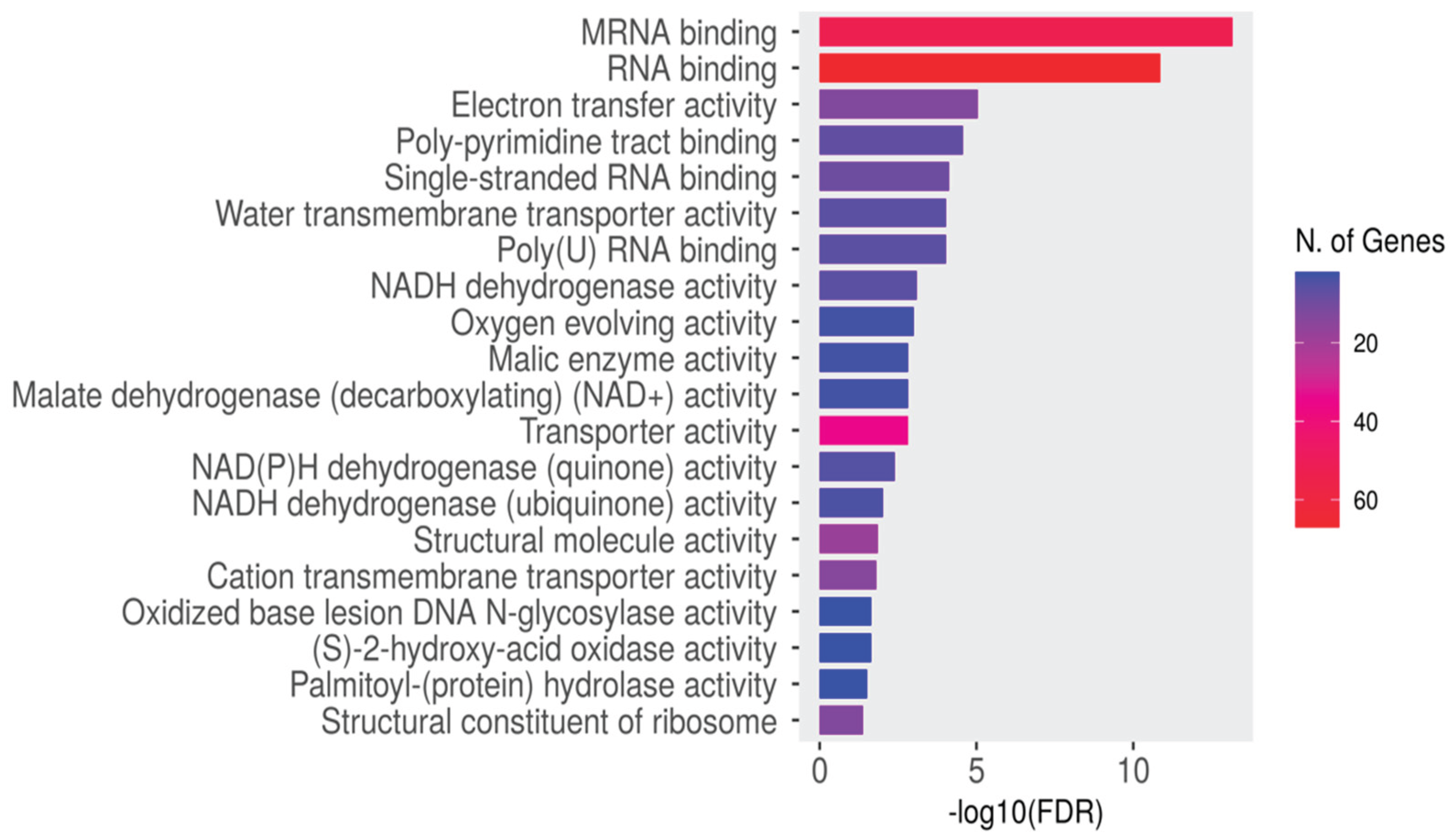

Gene Ontology (GO) Functional Analysis

GO enrichment analysis was conducted for host genes encoding dysregulated circRNAs. Most host genes were associated with plant development and protein binding activity, suggesting a regulatory role of circRNAs in host gene regulation.

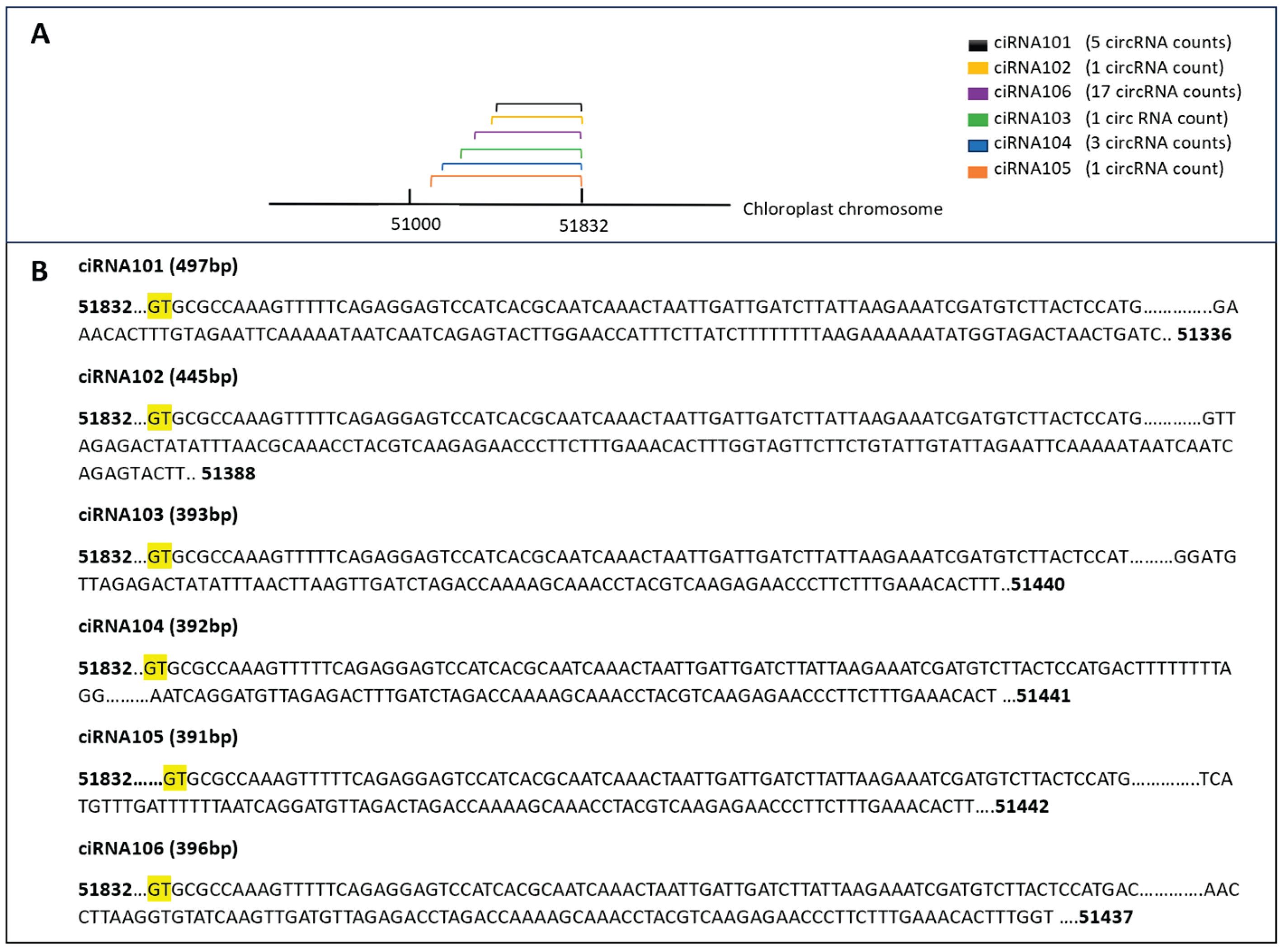

Characteristics of Chloroplast Derived circRNAs

In our study, the chloroplast chromosome exhibited the highest number of identified circRNAs, with a total of 288 circRNAs identified. To explore the diversity of these circRNAs, a subset was selected for further analysis. Notably, six circRNAs from this subset shared the same end position but differed in their start positions on the chloroplast chromosome. For example, ciRNA101 showed 5 counts in the circ-LTSV transgenic sample, while all other samples, including the control, showed zero counts. Similarly, ciRNA103 had 3 circRNA counts compared to the control's 8 circRNA counts. Despite these variations, all circRNAs shared the same ending position and differed by a few nucleotides in the start position (

Figure 12). Furthermore, selected circRNAs derived from the chloroplast were chosen for qPCR validation (

Figure 13). All selected circRNAs from the chloroplast for qPCR validation exhibited distinct start and end positions without any overlap.

Internal ORF Identification in circRNAs

Variations in circRNA2 counts were observed among transgenic and virus-infected groups. This circRNA exhibited elevated counts in all transgenic samples and reduced counts in TRoV-infected samples compared to the control group. Further analysis revealed that circRNA2 contains an open reading frame (ORF) with start and stop codons, suggesting its potential translatability to a protein. Similarly, circRNA205 (ATCG00020) showed count differences between non-host (RYMV) and host-virus samples. Notably, it exhibited 20 counts in the RYMV sample, while zero counts were recorded in the control and CP-TRoV/ scLTSV transgenic samples. Furthermore, circRNA205 contained an ORF region in its sequence, indicating potential translatability to a protein with similarities to a wheat protein known for monooxygenase activity.

Functional Insights of Identified circRNAs

This study profiled circRNAs from Arabidopsis thaliana in the presence of both host and non-host viruses for the first time. Several key findings include:

AT3G60240 (eIF4G): This gene generated circRNA expressed exclusively in the RYMV transgenic sample. The eIF4G protein, essential for translation initiation, reportedly also influences TCV multiplication (Yoshii et al., 2004)

AT4G21790 (TOM1): This gene generated circRNA expressed in the RYMV transgenics. TOM1 codes for a host factor necessary for TMV virus replication (Yamanaka et al., 2000).

AT3G05500 (SRP3): This gene showed low-level expression in the CP-TRoV transgenic sample compared to the negative control. Reportedly, overexpression of SRP3 results in improved drought stress tolerance and increased reproductive growth (Kim et al., 2016).

AT5G37475: This gene was expressed at low levels in the RYMV transgenic sample. It is involved in the formation of the eIF4G complex, which is crucial for initiating a subset of mRNAs involved in cell proliferation (TAIR, 2022).

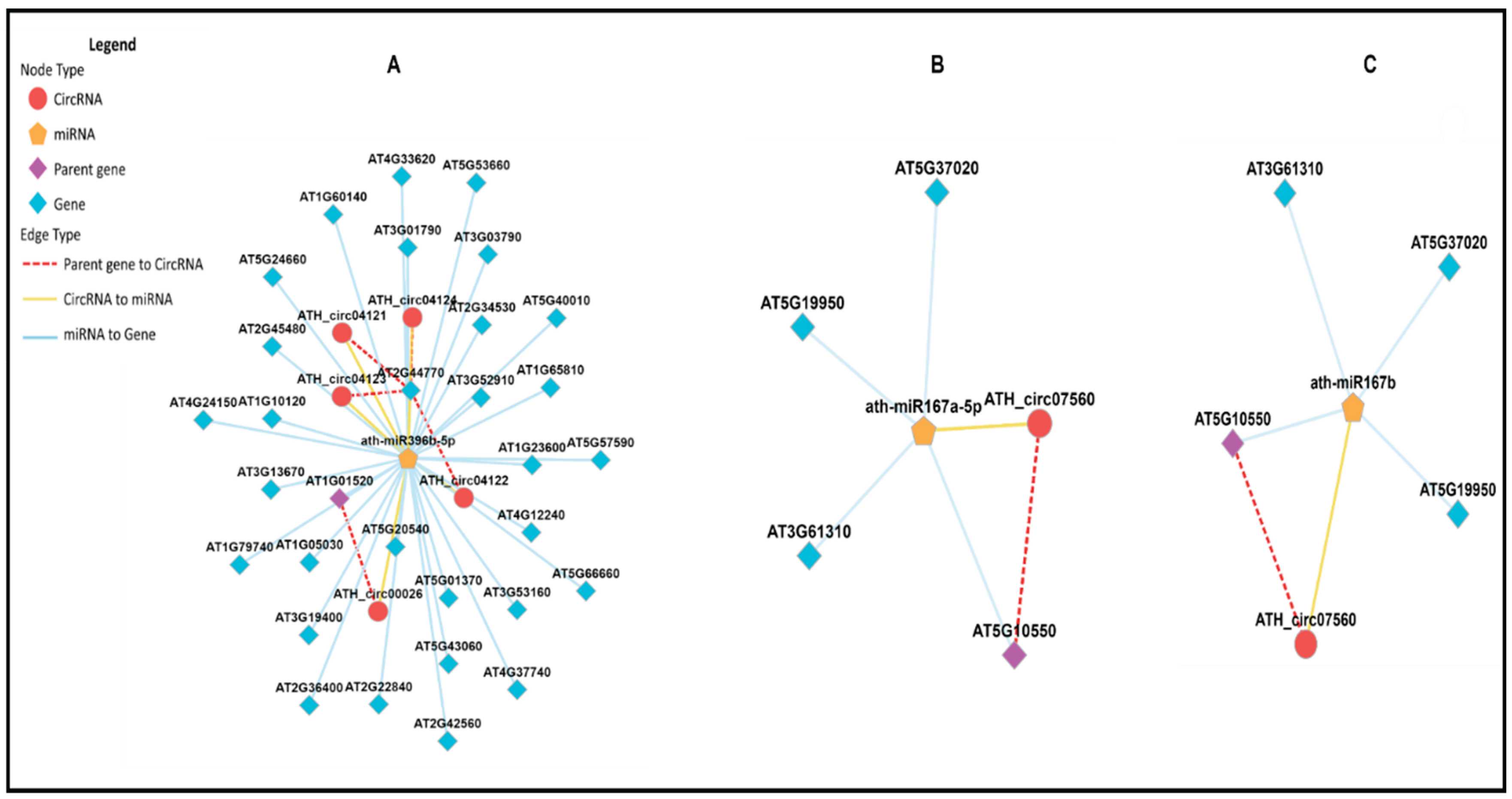

CircRNA-miRNA Interactions

In this study, we investigated whether identified circRNAs could act as miRNA sponges. Dysregulated circRNAs were predicted as miRNA target mimics using Targetfinder and Miranda. CircRNAs were found to have one or multiple decoy sites for miRNAs (

Figure 14). For example, circRNA291 (AT1G01520) might act as a decoy for miRNA ath-miR396b-5p. Similarly, circRNA236 (AT5G10550) might act as a decoy for two different miRNAs (ath-miR167a-5p and ath-miR167b). Multiple circRNAs from the same parental gene (AT1G01520) might act as decoys for one miRNA, such as circRNA ATH_circ04122, ATH_circ04121, and ATH_04124, all of which had miRNA ath-miR396b-5p binding sites.

Further examination revealed that mRNAs in the regulatory network of circRNA-miRNA-mRNA were mainly involved in plant growth and development. This suggests that circRNAs in plants respond to various stress conditions, including biotic and abiotic stresses, affecting miRNA expression profiles. While the circRNA-miRNA-mRNA network has been identified in plants, biochemical analyses are needed for further elucidation. Only one study reported the role of circRNA in plants, where exonic circRNA in A. thaliana was shown to regulate the splicing of its parental mRNA (Conn et al., 2017).

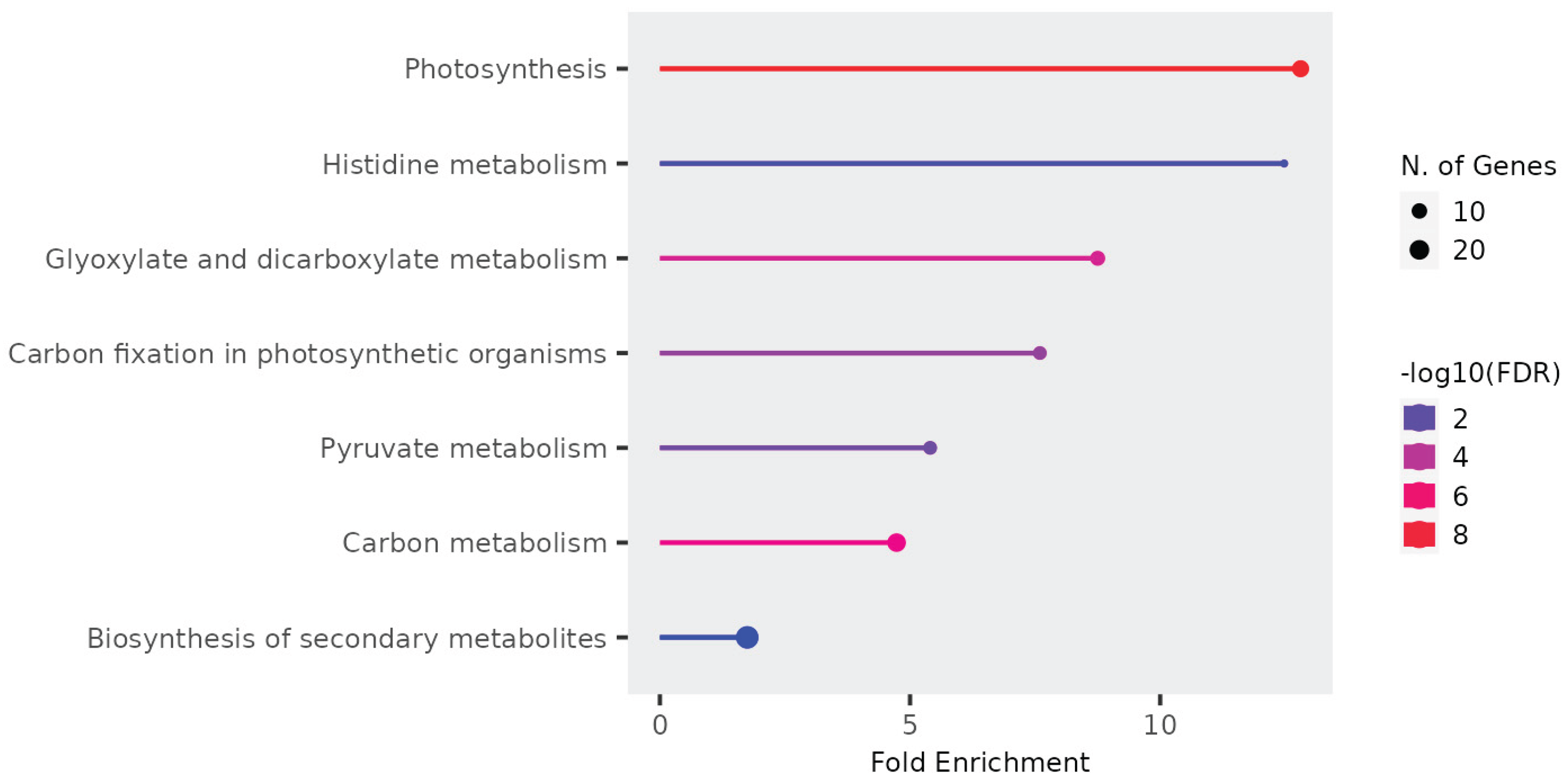

Enrichment Analysis

Enrichment analysis for all dysregulated genes was conducted using ShinyGO to extract essential biological processes, molecular functions, and KEGG pathways. Gene ontology and domain enrichment analyses were performed to elucidate the main biological functions of the identified circRNAs in our dataset. The analysis revealed expected biological functions, including plant development, RNA processing, and protein binding, with mRNA and RNA binding being the most significantly enriched function (

Figure 15 and

Figure 16).

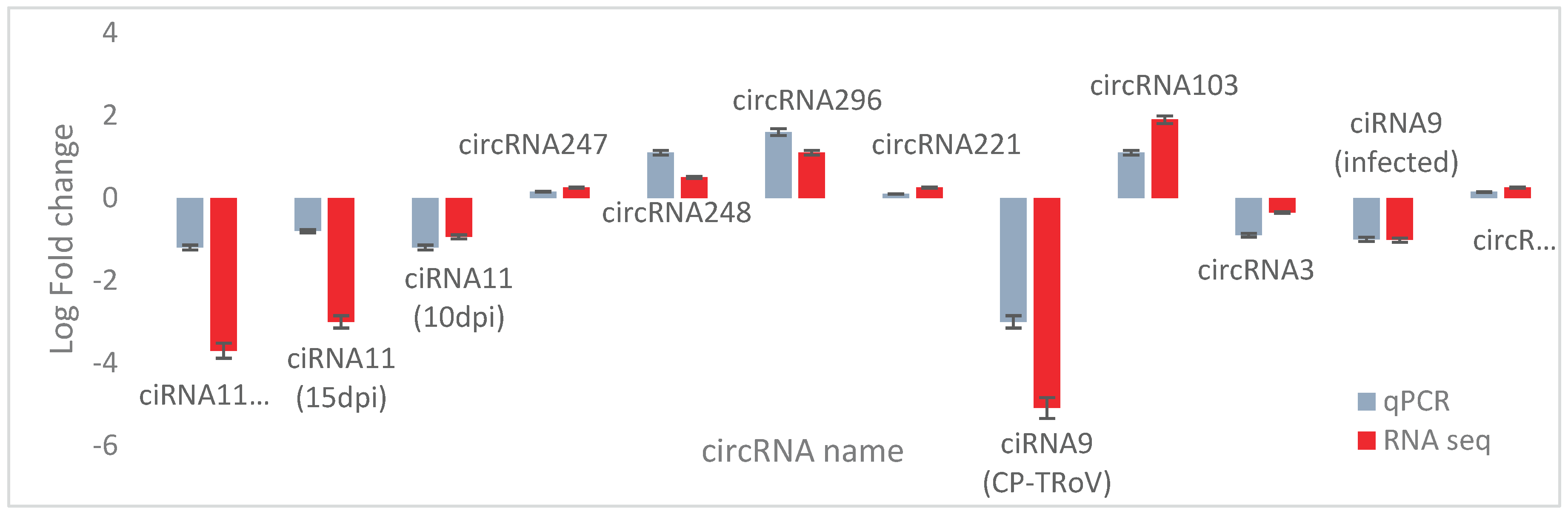

Validation of Identified circRNAs by RT-qPCR

To confirm the origin of selected circRNAs, RT-PCR followed by real-time quantitative qPCR was conducted. Primers were designed using Primer 3 software, ensuring the detection of authentic circRNAs with divergent primers and linear RNAs with convergent primers. RNase R treatment was applied to remove linear RNAs, and primer efficiency was validated before qPCR. Efficient primers (90-110% efficiency with R2 > 0.98) were selected for qPCR validation. Gene expression changes observed in qPCR aligned with RNA-seq analysis, confirming the dysregulation of selected circRNAs (

Figure 17). Strong correlation between qPCR and RNA-seq data validated the consistency of gene regulation patterns identified across both techniques.

5. Discussion

CircRNAs, emerging as vital gene regulators, encompass exogenous and endogenous types, yet their functions remain incompletely understood. While some roles, like miRNA "sponging," are recognized, much remains unclear, making differential expression analysis valuable. Our study sheds light on circRNA expression during virus infection and plant defense mechanisms. The escalating agricultural impact of plant viruses underscores the significance of understanding circRNA involvement. We explored circRNA profiles in virus-infected, uninfected, and transgenic plants expressing viral genes, revealing differential expression patterns across groups.

To elucidate A. thaliana's response to specific viral genes and non-host viruses, we employed transgenic plants. This novel approach unveils endogenous circRNA landscape alterations, providing insights into plant-virus interactions previously unexplored. Predictive analysis identified abundant and low-abundance circRNAs across experimental groups, revealing diverse origins in the A. thaliana genome. Dysregulated circRNAs, mainly from coding exons, underscored their potential regulatory roles in plant cells. GO enrichment analysis highlighted circRNA-associated host genes' involvement in diverse cellular processes, including stress response and mRNA binding. These findings suggest circRNAs' regulatory roles in plant defense mechanisms. Distinct circRNA expression patterns in virus-infected and transgenic plants point to potential plant genes implicated in infection processes. Notably, certain genes showed differential expression only in non-host plant samples, suggesting unique plant-virus interactions. PCA revealed distinct circRNA expression patterns among experimental groups, validating data reliability and highlighting circRNA alterations in response to viral infections. Dysregulated circRNAs identified in transgenic plants suggest exogenous circRNA (scLTSV) effects on endogenous circRNA expression, warranting further investigation into underlying mechanisms. Our data showed TA/GT and TT/GT as the highest splicing signals for the circRNAs, while Zhang et al. (2020) reported diverse splicing signals, with CT/AC and GT/AT being prominent. Another study on plant circRNAs, focusing on tomato plants under heat stress (Yang et al., 2020), found GU/AG as the predominant splice signal. Identification of dysregulated circRNAs with miRNA binding sites suggests potential miRNA sponging activity, implicating circRNAs in post-transcriptional gene regulation.

In our study, we found that circRNA2, involved in oxidoreductase and cytochrome complex assembly, showed varied expression patterns across different experimental conditions. Interestingly, it was upregulated in samples from RYMV, circ-LTSV, and CP-TRoV transgenic plants but downregulated in TRoV-infected samples compared to controls. The induction of circRNA2 seems to be triggered by various stressors on the plant, including mechanical stress induced by water inoculation and expression of scLTSV through the 35S promoter. This induction mechanism may involve RNA-RNA or RNA-DNA interactions, as scLTSV lacks coding capacity but can upregulate circRNA2, warranting experimental validation. Our findings suggest that transgenic circ-LTSV A. thaliana may induce resistance to helper virus TRoV infection, aligning with previous studies on viral satellite RNAs eliciting resistance to viral infections. Additionally, several cellular circRNAs, such as ATCG00030 (ciRNA106) and ATCG00130 (ciRNA11), are induced solely by the non-coding exogenous circLTSV.

Enriched pathways associated with photosynthesis and chloroplast-related processes in dysregulated circRNAs indicate intricate virus-chloroplast interactions influencing plant-virus dynamics. The exploration of chloroplast-derived circRNAs in our study revealed intriguing characteristics, particularly regarding their differential regulation in circ-LTSV transgenic plants. This selective disruption suggests a potential regulatory role for circ-LTSV in chloroplast-derived circRNAs. Additionally, the targeted approach for qPCR validation of circRNAs provided valuable insights into their structural diversity and potential functional roles, indicating nuanced regulation possibly associated with chloroplast-related processes or responses. The dysregulation of circRNAs across various samples, including TRoV-infected plants, RYMV (non-host) plants, and plants expressing viral genes, suggests complex interactions between viral components and plant circRNA pathways. While the exact mechanisms remain to be elucidated, hypotheses such as RNA-RNA interactions, miRNA sponging activity, or sequence similarities with plant miRNA or circRNA may contribute to circRNA dysregulation.

Our study's findings on circRNA expression patterns, especially in the context of viral infections and transgenic influences, shed light on the intricate regulatory landscape of circRNAs in plants. The genomic distribution of circRNAs and their differential expression patterns across samples provide valuable insights into the potential roles of circRNAs in plant biology and response to viral infections. The observations on plant morphology further underscore the impact of different viral infections on Arabidopsis plants, with notable differences in growth and symptom progression among TRoV-infected, RYMV-transgenic, and CP-TRoV-infected plants. These findings contribute to our understanding of the interactions between viruses and their plant hosts, potentially informing strategies for managing viral diseases in crops.

Unlike other studies that analyze mRNA to detect changes in circRNAs, our research focused exclusively on circRNAs. This approach allowed us to explore specific circRNAs that lack complementary sequences to miRNA and mRNA, suggesting a novel regulatory mechanism potentially involving RNA-RNA or RNA-DNA interactions, especially in circRNAs dysregulated in transgenic plants expressing the non-coding virusoid, circ-LTSV. Remarkably, our findings reveal that the majority of these circRNAs are localized to the chloroplast chromosome and intricately linked to the photosynthesis pathway, as evidenced by KEGG analysis. This association suggests a significant role for circRNAs in regulating critical photosynthetic processes, including light capture and energy conversion. This research not only deepens our comprehension of the functional dynamics of circRNAs within plant virology but also lays the groundwork for novel agricultural biotechnological applications aimed at enhancing crop resilience to viral threats, thus supporting food security.

Overall, this study provides extensive insights into the role of circRNAs in plant-virus interactions, highlighting their potential as targets for further research in plant biology, virology, and agricultural biotechnology.

6. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study provides novel insights into the regulatory role of circRNAs in plant-virus interactions, particularly in A. thaliana. Our findings highlight the diverse functions of circRNAs in modulating host gene expression and cellular responses to viral infections. We propose that further investigation into circRNA-mediated mechanisms could lead to the development of innovative strategies for enhancing plant resistance to viral diseases, thereby contributing to sustainable agriculture and food security.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

GMH conceptualized, designed, conducted research experiments and performed extensive bioinformatic analyses; SV conceptualized, designed, conducted experiments, supervised and communicated the manuscript; TH, AZ, and XC performed extensive bioinformatics analyses.

Funding

GH has been supported by a scholarship from the Saudi Cultural Bureau in Canada.

Acknowledgements

This work was conducted in Prof. Abouhaidar’s laboratory, University of Toronto. We acknowledge his valuable guidance and kind support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdelmohsen, K., Panda, A. C., De, S., Grammatikakis, I., Kim, J., Ding, J., Noh, J. H., Kim, K. M., Mattison, J. A., de Cabo, R., & Gorospe, M. (2015). Circular RNAs in monkey muscle: Age-dependent changes. Aging, 7(11). [CrossRef]

- Abel, P. P., Nelson, R. S., De, B., Hoffmann, N., Rogers, S. G., Fraley, R. T., & Beachy, R. N. (1986). Delay of disease development in transgenic plants that express the tobacco mosaic virus coat protein gene. Science, 232(4751). [CrossRef]

- AbouHaidar, M. G., Venkataraman, S., Golshani, A., Liu, B., & Ahmad, T. (2014). Novel coding, translation, and gene expression of a replicating covalently closed circular RNA of 220 nt. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(40). [CrossRef]

- Adkar-Purushothama, C. R., & Perreault, J. P. (2020). Current overview on viroid–host interactions. In Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA (Vol. 11, Issue 2). [CrossRef]

- Ashwal-Fluss, R., Meyer, M., Pamudurti, N. R., Ivanov, A., Bartok, O., Hanan, M., Evantal, N., Memczak, S., Rajewsky, N., & Kadener, S. (2014). CircRNA Biogenesis competes with Pre-mRNA splicing. Molecular Cell, 56(1). [CrossRef]

- Badar, U., Venkataraman, S., AbouHaidar, M., & Hefferon, K. (2021). Molecular interactions of plant viral satellites. In Virus Genes (Vol. 57, Issue 1). [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, M., Kim, B.-S., Hutchens-Williams, H. M., & Loesch-Fries, L. S. (2014). The Photosystem II Oxygen-Evolving Complex Protein PsbP Interacts With the Coat Protein of Alfalfa mosaic virus and Inhibits Virus Replication. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions®, 27(10), 1107–1118. [CrossRef]

- Blackstock, J. M. K. (1978). Lucerne transient streak and lucerne latent, two new viruses of lucerne. Australian Journal of Agricultural Research, 29(2). [CrossRef]

- Bolha, L., Ravnik-Glavač, M., & Glavač, D. (2017). Circular RNAs: Biogenesis, Function, and a Role as Possible Cancer Biomarkers. International Journal of Genomics, 2017, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Bossi, F., Cordoba, E., Dupré, P., Mendoza, M. S., Román, C. S., & León, P. (2009). The Arabidopsis ABA-INSENSITIVE (ABI) 4 factor acts as a central transcription activator of the expression of its own gene, and for the induction of ABI5 and SBE2.2 genes during sugar signaling. The Plant Journal, 59(3), 359–374. [CrossRef]

- Bradford, M. M. (1976). A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Analytical Biochemistry, 72(1–2), 248–254. [CrossRef]

- Briddon, R., Ghabrial, S., Lin, N., Palukaitis, P., Scholthof, K., & Vetten, H. (2012). Satellites and other virus-dependent nucleic acids. Virus Taxonomy-Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses, 1209–1219.

- BROADBENT, L., & HEATHCOTE, G. D. (1958). PROPERTIES AND HOST RANGE OF TURNIP CRINKLE, ROSETTE AND YELLOW MOSAIC VIRUSES. Annals of Applied Biology, 46(4), 585–592. [CrossRef]

- Chen, I., Chen, C. Y., & Chuang, T. J. (2015). Biogenesis, identification, and function of exonic circular RNAs. In Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: RNA (Vol. 6, Issue 5). [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Yu, Y., Zhang, X., Liu, C., Ye, C., & Fan, L. (2016). PcircRNA_finder: a software for circRNA prediction in plants. Bioinformatics, 32(22), 3528–3529. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-L., & Yang, L. (2015). Regulation of circRNA biogenesis. RNA Biology, 12(4), 381–388. [CrossRef]

- Chu, Q., Zhang, X., Zhu, X., Liu, C., Mao, L., Ye, C., Zhu, Q. H., & Fan, L. (2017). PlantcircBase: A Database for Plant Circular RNAs. In Molecular Plant (Vol. 10, Issue 8). [CrossRef]

- Conn, V. M., Hugouvieux, V., Nayak, A., Conos, S. A., Capovilla, G., Cildir, G., Jourdain, A., Tergaonkar, V., Schmid, M., Zubieta, C., & Conn, S. J. (2017). A circRNA from SEPALLATA3 regulates splicing of its cognate mRNA through R-loop formation. Nature Plants, 3. [CrossRef]

- Converse, R., & Martin, R. (1990). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Serological methods for detection and identification of viral and bacterial plant pathogens. A Laboratory Manual. In A Laboratory Manual (pp. 179–196).

- Dall, D. J., Graddon, D. J., Randles, J. W., & Francki, R. I. B. (1990). Isolation of a Subterranean Clover Mottle Virus-like Satellite RNA from Lucerne Infected with Lucerne Transient Streak Virus. Journal of General Virology, 71(8), 1873–1875. [CrossRef]

- Dangl, J. L., & Jones, J. D. G. (2001). Plant pathogens and integrated defence responses to infection. In Nature (Vol. 411, Issue 6839). [CrossRef]

- Daròs, J. A., & Flores, R. (2002). A chloroplast protein binds a viroid RNA in vivo and facilitates its hammerhead-mediated self-cleavage. EMBO Journal, 21(4). [CrossRef]

- DeFalco, T. A., & Zipfel, C. (2021). Molecular mechanisms of early plant pattern-triggered immune signaling. In Molecular Cell (Vol. 81, Issue 17). [CrossRef]

- Di Serio, F., Flores, R., Verhoeven, J. Th. J., Li, S.-F., Pallás, V., Randles, J. W., Sano, T., Vidalakis, G., & Owens, R. A. (2014). Current status of viroid taxonomy. Archives of Virology, 159(12), 3467–3478. [CrossRef]

- DIAZ-PENDON, J. A., TRUNIGER, V., NIETO, C., GARCIA-MAS, J., BENDAHMANE, A., & ARANDA, M. A. (2004). Advances in understanding recessive resistance to plant viruses. Molecular Plant Pathology, 5(3), 223–233. [CrossRef]

- Diener, T. O. (1971). Potato spindle tuber “virus”. IV. A replicating, low molecular weight RNA. Virology, 45(2). [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.-W., & Voinnet, O. (2007). Antiviral Immunity Directed by Small RNAs. Cell, 130(3), 413–426. [CrossRef]

- Dou, Y., Li, S., Yang, W., Liu, K., Du, Q., Ren, G., Yu, B., & Zhang, C. (2017). Genome-wide Discovery of Circular RNAs in the Leaf and Seedling Tissues of Arabidopsis Thaliana. Current Genomics, 18(4). [CrossRef]

- Du, W. W., Yang, W., Liu, E., Yang, Z., Dhaliwal, P., & Yang, B. B. (2016). Foxo3 circular RNA retards cell cycle progression via forming ternary complexes with p21 and CDK2. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(6). [CrossRef]

- Dubrovina, A. S., Kiselev, K. V., & Zhuravlev, Yu. N. (2013). The Role of Canonical and Noncanonical Pre-mRNA Splicing in Plant Stress Responses. BioMed Research International, 2013, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Duprat, A., Caranta, C., Revers, F., Menand, B., Browning, K. S., & Robaglia, C. (2002). The Arabidopsis eukaryotic initiation factor (iso)4E is dispensable for plant growth but required for susceptibility to potyviruses. The Plant Journal, 32(6), 927–934. [CrossRef]

- Eiras, M., Nohales, M. A., Kitajima, E. W., Flores, R., & Daròs, J. A. (2011). Ribosomal protein L5 and transcription factor IIIA from arabidopsis thaliana bind in vitro specifically potato spindle tuber viroid RNA. Archives of Virology, 156(3). [CrossRef]

- Feki, S., Loukili, M. J., Triki-Marrakchi, R., Karimova, G., Old, I., Ounouna, H., Nato, A., Nato, F., Guesdon, J.-L., Lafaye, P., & Elgaaied, A. B. Ammar. (2005). Interaction between tobacco Ribulose-l,5-biphosphate Carboxylase/Oxygenase large subunit (RubisCO-LSU) and the PVY Coat Protein (PVY-CP). European Journal of Plant Pathology, 112(3), 221–234. [CrossRef]

- Fitchen, J. H., & Beachy, R. N. (1993). Genetically engineered protection against viruses in transgenic plants. Annual Review of Microbiology, 47(1). [CrossRef]

- Flores, R., Gago-Zachert, S., Serra, P., Sanjuán, R., & Elena, S. F. (2014). Viroids: Survivors from the RNA World? Annual Review of Microbiology, 68(1), 395–414. [CrossRef]

- Flores, R., Gas, M. E., Molina-Serrano, D., Nohales, M. Á., Carbonell, A., Gago, S., De la Peña, M., & Daròs, J. A. (2009). Viroid replication: Rolling-circles, enzymes and ribozymes. In Viruses (Vol. 1, Issue 2). [CrossRef]

- Flores, R., Serra, P., Minoia, S., Di Serio, F., & Navarro, B. (2012). Viroids: From genotype to phenotype just relying on RNA sequence and structural motifs. Frontiers in Microbiology, 3(JUN). [CrossRef]

- FORSTER, R. L. S., & JONES, A. T. (1979). Properties of lucerne transient streak virus, and evidence of its affinity to southern bean mosaic virus. Annals of Applied Biology, 93(2), 181–189. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Z., Li, J., Luo, M., Li, H., Chen, Q., Wang, L., Song, S., Zhao, L., Xu, W., Zhang, C., Wang, S., & Ma, C. (2019). Characterization and Cloning of Grape Circular RNAs Identified the Cold Resistance-Related Vv-circATS1. Plant Physiology, 180(2), 966–985. [CrossRef]

- Gellatly, D., Mirhadi, K., Venkataraman, S., & AbouHaidar, M. G. (2011). Structural and sequence integrity are essential for the replication of the viroid-like satellite RNA of lucerne transient streak virus. Journal of General Virology, 92(6), 1475–1481. [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, A., Izadpanah, K., Peters, J. R., Dietzgen, R. G., & Mitter, N. (2018). Detection and profiling of circular RNAs in uninfected and maize Iranian mosaic virus-infected maize. Plant Science, 274, 402–409. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A., Rutgers, T., Ke-Qiang, M., & Kaesberg, P. (1981). Characterization of the Coat Protein mRNA of Southern Bean Mosaic Virus and Its Relationship to the Genomic RNA. Journal of Virology, 39(1), 87–92. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, T. C., Nagel, L., Rappold, W., Klotz, G., & Riesner, D. (1984). Viroid replication: equilibrium association constant and comparative activity measurements for the viroid-polymerase interaction. Nucleic Acids Research, 12(15), 6231–6246. [CrossRef]

- Guiu-Aragonés, C., Sánchez-Pina, M. A., Díaz-Pendón, J. A., Peña, E. J., Heinlein, M., & Martín-Hernández, A. M. (2016). cmv1 is a gate for Cucumber mosaic virus transport from bundle sheath cells to phloem in melon. Molecular Plant Pathology, 17(6), 973–984. [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. U., Agarwal, V., Guo, H., & Bartel, D. P. (2014). Expanded identification and characterization of mammalian circular RNAs. Genome Biology, 1–14.

- Gupta, S. P. (2018). The Medicinal Chemistry of Antihepatitis Agents I. In Studies on Hepatitis Viruses (pp. 79–96). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Hadidi, A., Flores, R., Randles, J. W., & Palukaitis, P. (2017). Viroids and Satellites.

- Hansen, T. B., Kjems, J., & Damgaard, C. K. (2013). Circular RNA and miR-7 in Cancer. In Cancer Research (Vol. 73, Issue 18). [CrossRef]

- Harwig, A., Landick, R., & Berkhout, B. (2017). The Battle of RNA Synthesis: Virus versus Host. Viruses, 9(10), 309. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. J., Jeong, S. C., Gore, M. A., Yu, Y. G., Buss, G. R., Tolin, S. A., & Maroof, M. A. S. (2004). Recombination Within a Nucleotide-Binding-Site/Leucine-Rich-Repeat Gene Cluster Produces New Variants Conditioning Resistance to Soybean Mosaic Virus in Soybeans. Genetics, 166(1), 493–503. [CrossRef]

- Hébrard, E., Poulicard, N., Gérard, C., Traoré, O., Wu, H.-C., Albar, L., Fargette, D., Bessin, Y., & Vignols, F. (2010). Direct Interaction Between the Rice yellow mottle virus (RYMV) VPg and the Central Domain of the Rice eIF(iso)4G1 Factor Correlates with Rice Susceptibility and RYMV Virulence. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions®, 23(11), 1506–1513. [CrossRef]

- Hofius, D., Maier, A. T., Dietrich, C., Jungkunz, I., Börnke, F., Maiss, E., & Sonnewald, U. (2007). Capsid Protein-Mediated Recruitment of Host DnaJ-Like Proteins Is Required for Potato Virus Y Infection in Tobacco Plants. Journal of Virology, 81(21), 11870–11880. [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.-C., Hsu, Y.-H., & Lin, N.-S. (2009). Satellite RNAs and Satellite Viruses of Plants. Viruses, 1(3), 1325–1350. [CrossRef]

- Huang, A., Zheng, H., Wu, Z., Chen, M., & Huang, Y. (2020). Circular RNA-protein interactions: functions, mechanisms, and identification. Theranostics, 10(8), 3503–3517. [CrossRef]

- Hull, R. (1995). Sobemovirus. Classification and Nomenclature of Viruses. Sixth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses.Eds.Murphy FA, Fauquet CM, Bishop DHL, Ghabrial SA, Jarvis AW, Martelli GP, Mayo MA, and MD Summers.Vienna: Springer Publishing, 376–378.

- Hull, R. (2014). Ecology, Epidemiology, and Control of Plant Viruses. In Plant Virology (pp. 809–876). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Izadpanah, K., Ahmadi, A. A., Parvin, S., & Jafari, S. A. (1983). Transmission, Particle Size and Additional Hosts of the Rhabdovirus Causing Maize Mosaic in Shiraz, Iran 1. Journal of Phytopathology, 107(3), 283–288. [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C., Pilat, M. L., Bentley, P. J., & Timmis, J. (2005). Artificial immune systems (Banff AB, 14-17 August 2005). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer.

- Jones, A. T., & Mayo, M. A. (1984). Satellite Nature of the Viroid-like RNA-2 of Solanum Nodiflorum Mottle Virus and the Ability of Other Plant Viruses to Support the Replication of Viroid-like RNA Molecules. Journal of General Virology, 65(10), 1713–1721. [CrossRef]

- Katsarou, K., Rao, A. L. N., Tsagris, M., & Kalantidis, K. (2015). Infectious long non-coding RNAs. Biochimie, 117, 37–47. [CrossRef]

- Kim, E. Y., Park, K. Y., Seo, Y. S., & Kim, W. T. (2016). Arabidopsis Small Rubber Particle Protein Homolog SRPs Play Dual Roles as Positive Factors for Tissue Growth and Development and in Drought Stress Responses . Plant Physiology, 170(4), 2494–2510. [CrossRef]

- Lai, X., Bazin, J., Webb, S., Crespi, M., Zubieta, C., & Conn, S. J. (2018). CircRNAs in Plants (pp. 329–343). [CrossRef]

- Lasda, E., & Parker, R. (2014). Circular RNAs: diversity of form and function. RNA, 20(12), 1829–1842. [CrossRef]

- Legnini, I., Di Timoteo, G., Rossi, F., Morlando, M., Briganti, F., Sthandier, O., Fatica, A., Santini, T., Andronache, A., Wade, M., Laneve, P., Rajewsky, N., & Bozzoni, I. (2017). Circ-ZNF609 Is a Circular RNA that Can Be Translated and Functions in Myogenesis. Molecular Cell, 66(1), 22-37.e9. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Shen, H., Wang, T., & Wang, X. (2015). ABA Regulates Subcellular Redistribution of OsABI-LIKE2, a Negative Regulator in ABA Signaling, to Control Root Architecture and Drought Resistance in Oryza sativa. Plant and Cell Physiology, 56(12), 2396–2408. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q. F., Zhang, Y. C., Chen, Y. Q., & Yu, Y. (2017). Circular RNAs roll into the regulatory network of plants. In Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications (Vol. 488, Issue 2). [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Cui, H., Cui, X., & Wang, A. (2016). The altered photosynthetic machinery during compatible virus infection. Current Opinion in Virology, 17, 19–24. [CrossRef]

- Liang, D., & Wilusz, J. E. (2014). Short intronic repeat sequences facilitate circular RNA production. Genes & Development, 28(20), 2233–2247. [CrossRef]

- Lightfoot, S., Salowsky, R., & Buhlmann, C. (2005). RNA integrity number: towards standardization of RNA quality assessment for better reproducibility and reliability of gene expression experiments. Breast Cancer Research, 7(S2), P7.05. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. H., Chang, M. F., Baker, S. C., Govindarajan, S., & Lai, M. M. (1990). Characterization of hepatitis delta antigen: specific binding to hepatitis delta virus RNA. Journal of Virology, 64(9), 4051–4058. [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.-Y., & Lin, N.-S. (2017). Interfering Satellite RNAs of Bamboo mosaic virus. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8. [CrossRef]

- Livak, K. J., & Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods, 25(4), 402–408. [CrossRef]

- Lu, T., Cui, L., Zhou, Y., Zhu, C., Fan, D., Gong, H., Zhao, Q., Zhou, C., Zhao, Y., Lu, D., Luo, J., Wang, Y., Tian, Q., Feng, Q., Huang, T., & Han, B. (2015). Transcriptome-wide investigation of circular RNAs in rice. RNA, 21(12), 2076–2087. [CrossRef]

- Lukiw, W. J. (2013). Circular RNA (circRNA) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Frontiers in Genetics, 4. [CrossRef]

- Maniataki, E., Tabler, M., & Tsagris, M. (2003). Viroid RNA systemic spread may depend on the interaction of a 71-nucleotide bulged hairpin with the host protein VirP1. RNA, 9(3). [CrossRef]

- Maniatis, T., Fritsch, E. F., & J. Sambrook. (1982). Molecular cloning. A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

- Martínez de Alba, A. E., Sägesser, R., Tabler, M., & Tsagris, M. (2003). A Bromodomain-Containing Protein from Tomato Specifically Binds Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid RNA In Vitro and In Vivo. Journal of Virology, 77(17), 9685–9694. [CrossRef]

- Massah, A., Izadpanah, K., Afsharifar, A. R., & Winter, S. (2008). Analysis of nucleotide sequence of Iranian maize mosaic virus confirms its identity as a distinct nucleorhabdovirus. Archives of Virology, 153(6), 1041–1047. [CrossRef]

- McClintock, K., Lamarre, A., Parsons, V., Laliberté, J.-F., & Fortin, M. G. (1998). Identification of a 37 kDa plant protein that interacts with the turnip mosaic potyvirus capsid protein using anti-idiotypic-antibodies. Plant Molecular Biology, 37(2), 197–204. [CrossRef]

- Memczak, S., Jens, M., Elefsinioti, A., Torti, F., Krueger, J., Rybak, A., Maier, L., Mackowiak, S. D., Gregersen, L. H., Munschauer, M., Loewer, A., Ziebold, U., Landthaler, M., Kocks, C., le Noble, F., & Rajewsky, N. (2013). Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature, 495(7441), 333–338. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X., Li, X., Zhang, P., Wang, J., Zhou, Y., & Chen, M. (2016). Circular RNA: an emerging key player in RNA world. Briefings in Bioinformatics, bbw045. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X., Zhang, P., Chen, Q., Wang, J., & Chen, M. (2018). Identification and characterization of ncRNA-associated ceRNA networks in Arabidopsis leaf development. BMC Genomics, 19(1), 607. [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, H., Okade, H., Muto, S., Suehiro, N., Nakashima, H., Tomoo, K., & Natsuaki, T. (2008). Turnip mosaic virus VPg interacts with Arabidopsis thaliana eIF(iso)4E and inhibits in vitro translation. Biochimie, 90(10), 1427–1434. [CrossRef]

- Musidlak, O., Nawrot, R., & Goździcka-Józefiak, A. (2017). Which Plant Proteins Are Involved in Antiviral Defense? Review on In Vivo and In Vitro Activities of Selected Plant Proteins against Viruses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 18(11), 2300. [CrossRef]

- Nassar, F. J., Talhouk, R., Zgheib, N. K., Tfayli, A., El Sabban, M., El Saghir, N. S., Boulos, F., Jabbour, M. N., Chalala, C., Boustany, R.-M., Kadara, H., Zhang, Z., Zheng, Y., Joyce, B., Hou, L., Bazarbachi, A., Calin, G., & Nasr, R. (2017). microRNA Expression in Ethnic Specific Early Stage Breast Cancer: an Integration and Comparative Analysis. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 16829. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.-A., Vera, A., & Flores, R. (2000). A Chloroplastic RNA Polymerase Resistant to Tagetitoxin Is Involved in Replication of Avocado Sunblotch Viroid. Virology, 268(1), 218–225. [CrossRef]

- Nigro, J. M., Cho, K. R., Fearon, E. R., Kern, S. E., Ruppert, J. M., Oliner, J. D., Kinzler, K. W., & Vogelstein, B. (1991). Scrambled exons. Cell, 64(3), 607–613. [CrossRef]

- Notarte, K. I., Senanayake, S., Macaranas, I., Albano, P. M., Mundo, L., Fennell, E., Leoncini, L., & Murray, P. (2021). MicroRNA and Other Non-Coding RNAs in Epstein–Barr Virus-Associated Cancers. Cancers, 13(15), 3909. [CrossRef]

- Orjuela, J., Deless, E. F. T., Kolade, O., Chéron, S., Ghesquière, A., & Albar, L. (2013). A Recessive Resistance to Rice yellow mottle virus Is Associated with a Rice Homolog of the CPR5 Gene, a Regulator of Active Defense Mechanisms. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions®, 26(12), 1455–1463. [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, Y. C. (1983). Identification and distribution in eastern Canada of lucerne transient streak, a virus newly recognized in North America. Canadian Journal of Plant Pathology, 5(2), 75–80. [CrossRef]

- Palukaitis, P. (2014). What has been happening with viroids? Virus Genes, 49(2), 175–184. [CrossRef]

- Pan, T., Sun, X., Liu, Y., Li, H., Deng, G., Lin, H., & Wang, S. (2018). Correction to: Heat stress alters genome-wide profiles of circular RNAs in Arabidopsis. Plant Molecular Biology, 96(3), 231–231. [CrossRef]

- Panda, A. C., Abdelmohsen, K., & Gorospe, M. (2017). RT-qPCR Detection of Senescence-Associated Circular RNAs (pp. 79–87). [CrossRef]

- Patop, I. L., Wüst, S., & Kadener, S. (2019). Past, present, and future of circ <scp>RNA</scp> s. The EMBO Journal, 38(16). [CrossRef]

- Patrick, R. M., & Browning, K. S. (2012). The eIF4F and eIFiso4F Complexes of Plants: An Evolutionary Perspective. Comparative and Functional Genomics, 2012, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Po, T. (1985). VIROIDS AND VIROID DISEASES IN CHINA. In Subviral Pathogens of Plants and Animals: Viroids and Prions (pp. 123–136). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- PRINS, M., LAIMER, M., NORIS, E., SCHUBERT, J., WASSENEGGER, M., & TEPFER, M. (2008). Strategies for antiviral resistance in transgenic plants. Molecular Plant Pathology, 9(1), 73–83. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y., Dou, P., Hu, M., Xu, J., Xia, W., & Sun, H. (2019). circRNA-CER mediates malignant progression of breast cancer through targeting the miR-136/MMP13 axis. Molecular Medicine Reports. [CrossRef]

- Quesada, V., Ponce, M. R., & Micol, J. L. (2000). Genetic analysis of salt-tolerant mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics, 154(1). [CrossRef]

- Rao, A. L. N., & Kalantidis, K. (2015). Virus-associated small satellite RNAs and viroids display similarities in their replication strategies. In Virology (Vols. 479–480). [CrossRef]

- Raza, A., Al-Shahwan, I. M., Abdalla, O. A., Al-Saleh, M. A., & Amer, M. A. (2017). Lucerne transient streak virus; a recently detected virus infecting alfafa (Medicago sativa) in central Saudi Arabia. Plant Pathology Journal, 33(1), 43–52. [CrossRef]

- Revers, F., & Nicaise, V. (2014). Plant Resistance to Infection by Viruses. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M. D., McCarthy, D. J., & Smyth, G. K. (2010). <tt>edgeR</tt> : a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics, 26(1), 139–140. [CrossRef]

- Roossinck, M. J., Sleat, D., & Palukaitis, P. (1992). Satellite RNAs of plant viruses: structures and biological effects. Microbiological Reviews, 56(2), 265–279. [CrossRef]

- Rutgers, T., Salerno-rife, T., & Kaesberg, P. (1980). Messenger RNA for the coat protein of southern bean mosaic virus. Virology, 104(2). [CrossRef]

- Salzman, J., Gawad, C., Wang, P. L., Lacayo, N., & Brown, P. O. (2012). Circular RNAs are the predominant transcript isoform from hundreds of human genes in diverse cell types. PLoS ONE, 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Sanfaçon, H. (2015). Plant translation factors and virus resistance. In Viruses (Vol. 7, Issue 7). [CrossRef]

- Sanger, H. L., Klotz, G., Riesner, D., Gross, H. J., & Kleinschmidt, A. K. (1976). Viroids are single stranded covalently closed circular RNA molecules existing as highly base paired rod like structures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 73(11). [CrossRef]

- Sapan, C. V., Lundblad, R. L., & Price, N. C. (1999). Colorimetric protein assay techniques. Biotechnology and Applied Biochemistry, 29(2), 99–108. [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, O. P., Sinha, R. C., Gellatly, D. L., Ivanov, I., & AbouHaidar, M. G. (1993). Replication and encapsidation of the viroid-like satellite RNA of lucerne transient streak virus are supported in divergent hosts by cocksfoot mottle virus and turnip rosette virus. Journal of General Virology, 74(4). [CrossRef]

- Sels, J., Mathys, J., De Coninck, B. M. A., Cammue, B. P. A., & De Bolle, M. F. C. (2008). Plant pathogenesis-related (PR) proteins: A focus on PR peptides. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 46(11), 941–950. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P., Guria, A., Natesan, S., & Pandi, G. (2021). Generation of Transgenic Rice Expressing CircRNA and Its Functional Characterization (pp. 35–68). [CrossRef]

- Shimura, H., & Masuta, C. (2016). Plant subviral RNAs as a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA): Analogy with animal lncRNAs in host-virus interactions. Virus Research, 212. [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. A., Eamens, A. L., & Wang, M. B. (2011). Viral small interfering RNAs target host genes to mediate disease symptoms in plants. PLoS Pathogens, 7(5). [CrossRef]

- Sõmera, M., Sarmiento, C., & Truve, E. (2015). Overview on sobemoviruses and a proposal for the creation of the family Sobemoviridae. In Viruses (Vol. 7, Issue 6). [CrossRef]

- Sõmera, M., & Truve, E. (2013). The genome organization of lucerne transient streak and turnip rosette sobemoviruses revisited. Archives of Virology, 158(3), 673–678. [CrossRef]

- STRAUSS, J. H., & STRAUSS, E. G. (2008). Minus-Strand RNA Viruses. In Viruses and Human Disease (pp. 137–191). Elsevier. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y., Zhang, H., Fan, M., He, Y., & Guo, P. (2020). Genome-wide identification of long non-coding RNAs and circular RNAs reveal their ceRNA networks in response to cucumber green mottle mosaic virus infection in watermelon. Archives of Virology, 165(5). [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H., & Tsukahara, T. (2014). A View of Pre-mRNA Splicing from RNase R Resistant RNAs. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 15(6), 9331–9342. [CrossRef]

- Tatineni, S., & Hein, G. L. (2023). Plant Viruses of Agricultural Importance: Current and Future Perspectives of Virus Disease Management Strategies. In Phytopathology (Vol. 113, Issue 2). [CrossRef]

- Vaghela, B., Vashi, R., Rajput, K., & Joshi, R. (2022). Plant chitinases and their role in plant defense: A comprehensive review. In Enzyme and Microbial Technology (Vol. 159). [CrossRef]

- Várallyay, É., Válóczi, A., Ágyi, Á., Burgyán, J., & Havelda, Z. (2010). Plant virus-mediated induction of miR168 is associated with repression of ARGONAUTE1 accumulation. The EMBO Journal, 29(20), 3507–3519. [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, S., Badar, U., Shoeb, E., Hashim, G., AbouHaidar, M., & Hefferon, K. (2021). An Inside Look into Biological Miniatures: Molecular Mechanisms of Viroids. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(6), 2795. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Gao, Y., Sun, S., Li, L., & Wang, K. (2022). Expression Characteristics in Roots, Phloem, Leaves, Flowers and Fruits of Apple circRNA. Genes, 13(4). [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Li, J., Guo, B., Xu, L., Li, L., Song, X., Wang, X., Zeng, X., Wu, L., Niu, D., Sun, K., Sun, X., & Zhao, H. (2022). Exonic Circular RNAs Are Involved in Arabidopsis Immune Response Against Bacterial and Fungal Pathogens and Function Synergistically with Corresponding Linear RNAs. Phytopathology, 112(3). [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. L., Bao, Y., Yee, M. C., Barrett, S. P., Hogan, G. J., Olsen, M. N., Dinneny, J. R., Brown, P. O., & Salzman, J. (2014). Circular RNA is expressed across the eukaryotic tree of life. PLoS ONE, 9(3). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Yang, M., Wei, S., Qin, F., Zhao, H., & Suo, B. (2017). Identification of circular RNAs and their targets in leaves of Triticum aestivum L. under dehydration stress. Frontiers in Plant Science, 7. [CrossRef]

- Wei, T., Zhang, C., Hong, J., Xiong, R., Kasschau, K. D., Zhou, X., Carrington, J. C., & Wang, A. (2010). Formation of complexes at plasmodesmata for potyvirus intercellular movement is mediated by the viral protein P3N-PIPO. PLoS Pathogens, 6(6). [CrossRef]

- Wen-Sheng, X., Xiang-Jing, W., Tian-Rui, R., & Su-Qin, C. (2006). Purification of recombinant wheat cytochrome P450 monooxygenase expressed in yeast and its properties. Protein Expression and Purification, 45(1). [CrossRef]

- Wilson, T. J., & Lilley, D. M. J. (2009). The Evolution of Ribozyme Chemistry. Science, 323(5920), 1436–1438. [CrossRef]

- Yamanaka, T., Ohta, T., Takahashi, M., Meshi, T., Schmidt, R., Dean, C., Naito, S., & Ishikawa, M. (2000). TOM1 , an Arabidopsis gene required for efficient multiplication of a tobamovirus, encodes a putative transmembrane protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 97(18), 10107–10112. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X., Liu, Y., Zhang, H., Wang, J., Zinta, G., Xie, S., Zhu, W., & Nie, W. F. (2020). Genome-Wide Identification of Circular RNAs in Response to Low-Temperature Stress in Tomato Leaves. Frontiers in Genetics, 11. [CrossRef]

- Ye, C. Y., Chen, L., Liu, C., Zhu, Q. H., & Fan, L. (2015). Widespread noncoding circular RNAs in plants. New Phytologist, 208(1). [CrossRef]

- Yie, Y., & Tien, P. (1993). Plant virus satellite RNAs and their role in engineering resistance to virus diseases. Seminars in Virology, 4(6), 363–368. [CrossRef]

- Yoshii, M., Nishikiori, M., Tomita, K., Yoshioka, N., Kozuka, R., Naito, S., & Ishikawa, M. (2004). The Arabidopsis Cucumovirus Multiplication 1 and 2 Loci Encode Translation Initiation Factors 4E and 4G. Journal of Virology, 78(12), 6102–6111. [CrossRef]

- Zaphiropoulos, P. G. (1996). Circular RNAs from transcripts of the rat cytochrome P450 2C24 gene: correlation with exon skipping. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(13), 6536–6541. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X., Lin, W., Guo, M., & Zou, Q. (2017). A comprehensive overview and evaluation of circular RNA detection tools. In PLoS Computational Biology (Vol. 13, Issue 6). [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y., Yuan, Q., Qiu, S., Li, S., Li, M., Zheng, H., Wu, G., Lu, Y., Peng, J., Rao, S., Chen, J., & Yan, F. (2021). Turnip mosaic virus impairs perinuclear chloroplast clustering to facilitate viral infection. Plant, Cell & Environment, 44(11), 3681–3699. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Fan, Y., Sun, X., Chen, L., Terzaghi, W., Bucher, E., Li, L., & Dai, M. (2019). A large-scale circular RNA profiling reveals universal molecular mechanisms responsive to drought stress in maize and Arabidopsis. Plant Journal, 98(4). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Li, S., & Chen, M. (2020). Characterization and Function of Circular RNAs in Plants. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 7. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Liu, Y., Chen, H., Meng, X., Xue, J., Chen, K., & Chen, M. (2020). CircPlant: An Integrated Tool for circRNA Detection and Functional Prediction in Plants. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics, 18(3), 352–358. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W., Olson, N. H., Baker, T. S., Faulkner, L., Agbandje-McKenna, M., Boulton, M. I., Davies, J. W., & McKenna, R. (2001). Structure of the maize streak virus geminate particle. Virology, 279(2). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. O., Dong, R., Zhang, Y., Zhang, J. L., Luo, Z., Zhang, J., Chen, L. L., & Yang, L. (2016). Diverse alternative back-splicing and alternative splicing landscape of circular RNAs. Genome Research, 26(9). [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Zhang, X., Hong, Y., & Liu, Y. (2016). Chloroplast in Plant-Virus Interaction. Frontiers in Microbiology, 7. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R., Yu, X. Q., Xu, L. P., Wang, Y. L., Zhao, L. P., Zhao, T. M., & Yu, W. G. (2019). Genome-wide identification of circular RNAs in tomato seeds in response to high temperature. Biologia Plantarum, 63. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Ye, J., Zhang, L., Xia, L., Hu, H., Jiang, H., Wan, Z., Sheng, F., Ma, Y., Li, W., Qian, J., & Luo, C. (2017). Differential Expression of Circular RNAs in Glioblastoma Multiforme and Its Correlation with Prognosis. Translational Oncology, 10(2), 271–279. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, J., Wang, Q., Zhu, B., Luo, Y., & Gao, L. (2016). Deciphering the roles of circRNAs on chilling injury in tomato. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 479(2), 132–138. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

RT-PCR results of genomic (virus-infected plants) and transcripts of TRoV capsid protein in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. RNA samples were used after DNase treatment for the cDNA synthesis, followed by PCR. Panel A. Lane 1: RT-PCR product of healthy Arabidopsis used as the negative control. Lane 2: empty lane. Lane 3: 800 bp RT-PCR product from plants infected with TRoV (positive control). Lane 4: 800 bp RT-PCR product from CP-TRoV transgenic plants. Panel B. Elongation factor gene was included for internal control experiments. 35 cycles for each analysis were applied.

Figure 1.

RT-PCR results of genomic (virus-infected plants) and transcripts of TRoV capsid protein in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. RNA samples were used after DNase treatment for the cDNA synthesis, followed by PCR. Panel A. Lane 1: RT-PCR product of healthy Arabidopsis used as the negative control. Lane 2: empty lane. Lane 3: 800 bp RT-PCR product from plants infected with TRoV (positive control). Lane 4: 800 bp RT-PCR product from CP-TRoV transgenic plants. Panel B. Elongation factor gene was included for internal control experiments. 35 cycles for each analysis were applied.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR results of genomic (virus-infected plants) and transcripts of genomic RYMV in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. RNA samples were used after DNase treatment for the cDNA synthesis, followed by PCR. Panel A. Lane 1: RT-PCR product of healthy rice used as the negative control. Lane 2: 720 bp RT-PCR product from rice plants infected with RYMV (positive control). Lane 3: RT-PCR product of healthy Arabidopsis used as the negative control Lane 4: 720 bp RT-PCR product from genomic RYMV expressed in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Panel B. Elongation factor gene was included for internal control experiments. 35 cycles for each analysis were applied.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR results of genomic (virus-infected plants) and transcripts of genomic RYMV in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. RNA samples were used after DNase treatment for the cDNA synthesis, followed by PCR. Panel A. Lane 1: RT-PCR product of healthy rice used as the negative control. Lane 2: 720 bp RT-PCR product from rice plants infected with RYMV (positive control). Lane 3: RT-PCR product of healthy Arabidopsis used as the negative control Lane 4: 720 bp RT-PCR product from genomic RYMV expressed in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Panel B. Elongation factor gene was included for internal control experiments. 35 cycles for each analysis were applied.

Figure 3.

RT-PCR results of sc-LTSV in transgenic Arabidopsis plants infected with TRoV. RNA samples were used after DNase treatment for the cDNA synthesis, followed by PCR. Panel A. 322 bp product was obtained in the transgenic A. thaliana infected with TRoV other bands were observed at 522 due to the presence of concatamers (200 + 322 bp on circ-LTSV transcript) bp and 844 bp due to the production of concatemers in the rolling circle replication process in lane 1. Lane 2. No bands were visible in the negative control. Panel B. Elongation factor gene was included for internal control experiments. 35 cycles for each analysis were applied.

Figure 3.

RT-PCR results of sc-LTSV in transgenic Arabidopsis plants infected with TRoV. RNA samples were used after DNase treatment for the cDNA synthesis, followed by PCR. Panel A. 322 bp product was obtained in the transgenic A. thaliana infected with TRoV other bands were observed at 522 due to the presence of concatamers (200 + 322 bp on circ-LTSV transcript) bp and 844 bp due to the production of concatemers in the rolling circle replication process in lane 1. Lane 2. No bands were visible in the negative control. Panel B. Elongation factor gene was included for internal control experiments. 35 cycles for each analysis were applied.

Figure 4.

RT-PCR results of sc-LTSV in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. RNA samples were used after DNase treatment for the cDNA synthesis, followed by PCR. Lanes 1 and 2. No bands were visible in the negative controls. Lane 4. 322 bp product was obtained from turnip infected with LTSV used as a positive control. Lane 6. 322 bp product was obtained in the transgenic A. thaliana.

Figure 4.

RT-PCR results of sc-LTSV in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. RNA samples were used after DNase treatment for the cDNA synthesis, followed by PCR. Lanes 1 and 2. No bands were visible in the negative controls. Lane 4. 322 bp product was obtained from turnip infected with LTSV used as a positive control. Lane 6. 322 bp product was obtained in the transgenic A. thaliana.

Figure 5.

RT-PCR results of transgenic scLTSV Arabidopsis using CP-TRoV primers. RNA samples were used after DNase treatment for the cDNA synthesis, followed by PCR. Panel A. Lanes A: RT-PCR product from the transgenic scLTSV Arabidopsis used as the negative control. Lane B: RT-PCR product of healthy Arabidopsis used as the negative control. Lane C: transgenic scLTSV Arabidopsis infected with TRoV showing the resistance of the scLTSV transgenic plants to TRoV. Lane D: 800 bp RT-PCR product from Arabidopsis plants infected with TRoV alone (positive control). Panel B. Elongation factor gene was included for internal control experiments 35 cycles for each analysis were applied.

Figure 5.

RT-PCR results of transgenic scLTSV Arabidopsis using CP-TRoV primers. RNA samples were used after DNase treatment for the cDNA synthesis, followed by PCR. Panel A. Lanes A: RT-PCR product from the transgenic scLTSV Arabidopsis used as the negative control. Lane B: RT-PCR product of healthy Arabidopsis used as the negative control. Lane C: transgenic scLTSV Arabidopsis infected with TRoV showing the resistance of the scLTSV transgenic plants to TRoV. Lane D: 800 bp RT-PCR product from Arabidopsis plants infected with TRoV alone (positive control). Panel B. Elongation factor gene was included for internal control experiments 35 cycles for each analysis were applied.

Figure 6.