1. Introduction

Heart Failure and related readmissions contribute to one of the highest causes of healthcare resource utilization in the United States (US). Hospital admissions for patients with a primary diagnosis of heart failure as well as those who may have CHF as a secondary diagnosis have proven to be burdensome to both hospital systems as well as for patient morbidity and mortality. [

1]. The major contributors to this include cost of treating comorbidities, invasive procedures and readmissions. [

25] Congestive heart failure is also the number one cause of hospital admission across the US and accounts for 26.9% of all 30-day re-admissions. [

2] Much of the morbid symptom burden from this pathology is due to an overload of circulatory volume which leads to intravascular congestion. The pathophysiology of volume overload is complex and is the result of multiple related physiologic and pathologic pathways. Elevated cardiac filling pressures play a key role in the pathophysiology of both heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) as well as heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF.) [

3]. While pathologic medical factors such as concurrent atrial fibrillation, chronic lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, and obesity do have a physiologic impact on elevating cardiac filling pressures, there are also secondary drivers eliciting re admission in some populations. Socioeconomic factors have been noted to play a strong role in heart failure readmissions, especially those in vulnerable populations with higher degrees of negative social determinants of health (SDOH). [

4]. Though there have been recent advancements in the manage of congestive heart failure, Guideline Directed Medical therapy (GDMT) remains the cornerstone of how this condition is managed both in ambulatory as well as for patients who are hospitalized. Notably, the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) as well beta-adrenergic receptors have been found to have a role in cardiac remodeling. The utilization of both beta blockade as well as RAAS inhibition has been found to subdue to progression of cardiac remodeling seen in patients with CHF, thus reducing the magnitude of filling pressure elevation. GDMT thereby has a known association with prevention of heart failure readmissions [

5]. Multiple trials including the STRONG -HF trial [

6], have shown that using intensive GDMT therapy in patients hospitalized with HFrEF is both cost-effective and results in improved clinical outcomes. Likewise, data has shown a strong association with the use of quadruple GDMT (ARNI+beta blockade+mineralcorticoid receptor antagonist+SGLT2-i) and better outcomes. Though the data supports the use of GDMT, it does have limitations in a variety of patient populations. Both socioeconomic factors such as unfunded patients, limited follow up, low health literacy as well as medical comorbidities such as patients with ESRD, hypotension or bradycardia may bar GDMT utilization. Presence of comorbidities, especially chronic kidney disease (CKD) further increases the burden by preventing the use of RAAS inhibitors, which play a key role in prevention of remodeling. Most patients with acute decompensated heart failure still have residual congestion even after hospitalization and intensive diuretic regimen. This factor was associated with higher rates of re-hospitalization and death. Decongestion surrogates, such as diuretic response, are still significant predictors of outcomes, but they do not provide meaningful additive prognostic information [

7].

2. Materials and Methods

We used the National readmission Database (NRD) 2021 to obtain materials for analysis. STATA 18 was used for statistical analysis. The index events for Congestive Heart Failure admissions between the months January and September of 2021 were selected using the ICD diagnosis codes (I110, I130, I132, I5020-I5023, I5030-I5033, I5040-I5043). Inclusion criteria are as stated: Age > 18, and no documented mortality during the index admission. Additionally, only patients with documented unique patient linkage numbers were included in this study. Readmission events for both 30- and 90-day periods following initial admission were subsequently analyzed. Patient data was also obtained to stratify the number of re-admission events recorded following initial admission. This allowed for grouping based both on number of re-admissions as well as re-admission initial diagnosis. Population characteristics of each group were collected (groups include initial admission, 30- and 90-day admission groups). Characteristics obtained included sex, quarterly income, and concurrent alcohol or tobacco use. The total hospital charges for each admission group were analyzed into weighted means. The index admission population as well as the readmission population were stratified based on the quarterly income to account for economic disparities that hold associations with repeat admissions for heart failure. Re-admissions were analyzed using ICD 10 codes for the documented main diagnosis of the readmission event. Readmissions for heart failure (ICD 10: I110, I130, I132, I5020-I5023, I5030-I5033, I5040-I5043), Acute Myocardial Infarction (ICD 10: I219, I214), Acute Kidney Injury (ICD N179), sepsis (ICD 10 A419), COVID 19 (ICD 10 U071), Community Acquired Pneumonia (ICD 10 J189) and COPD (ICD 10 J449) were included. Association of comorbid conditions with both re-admission groups (30 and 90 day) were determined. Multivariate logistic regression was used for the analysis. Age, sex, income, associated smoking and alcohol abuse were used to account for confounding as they have independent association with both the index as well as the readmission events. A two tailed p value < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. The association between lower quartile of the income in the readmission pool and occurrence of readmission events were done.

3. Results

We identified 5,61,371 admissions for heart failure between the months of January, and September 2021.

In the 30 days following discharge, there were a total of 146,714 patients who had readmission events, and 230,677 total readmission events among this patient population pool. In the 90 days following discharge, 190,994 patients had readmission events and 349,416 total readmission events among this patient population pool.

For the 30-day re-admission pool, 22,585 patients had readmission for subsequent CHF exacerbation as primary diagnosis. A total of 31,363 heart failure readmission events were identified in this pool. In the 90-day pool, a total of 43,225 patients had readmission for subsequent heart failure exacerbations, with a total of 75,352 total heart failure related readmissions.

Population analysis of initial heart failure admission as well as 30- and 90-day readmission pools are summarized below in

Table 1.

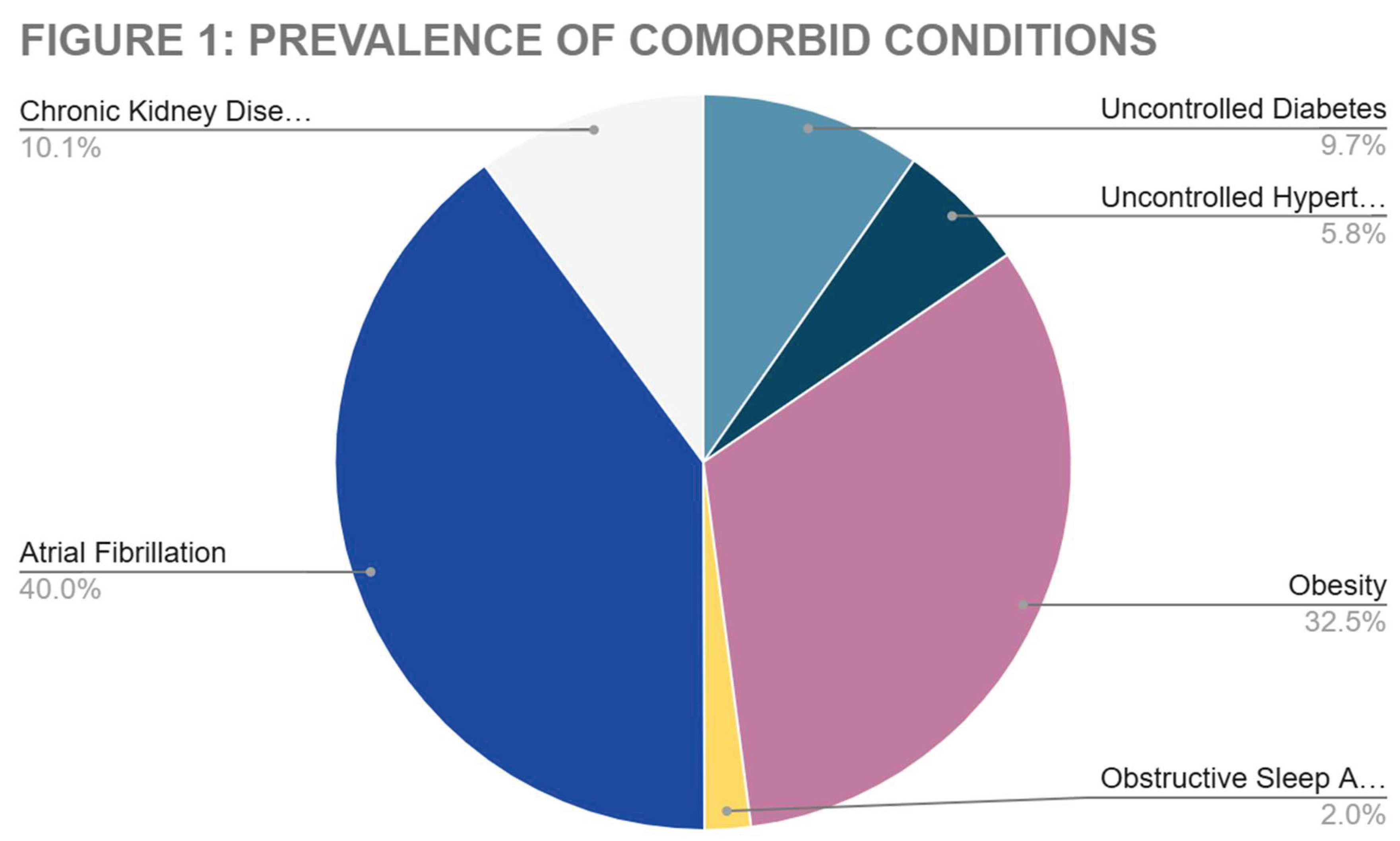

Additional analysis of comorbid conditions in patients who had readmission events for repeat heart failure exacerbation both 30- and 90-day groups are depicted in

Figure 1, below.

Total hospital charges and length of stay were compared between the initial admissions and the readmission groups for heart failure. Charges for both 30- and 90-day groups are below in

Table 2.

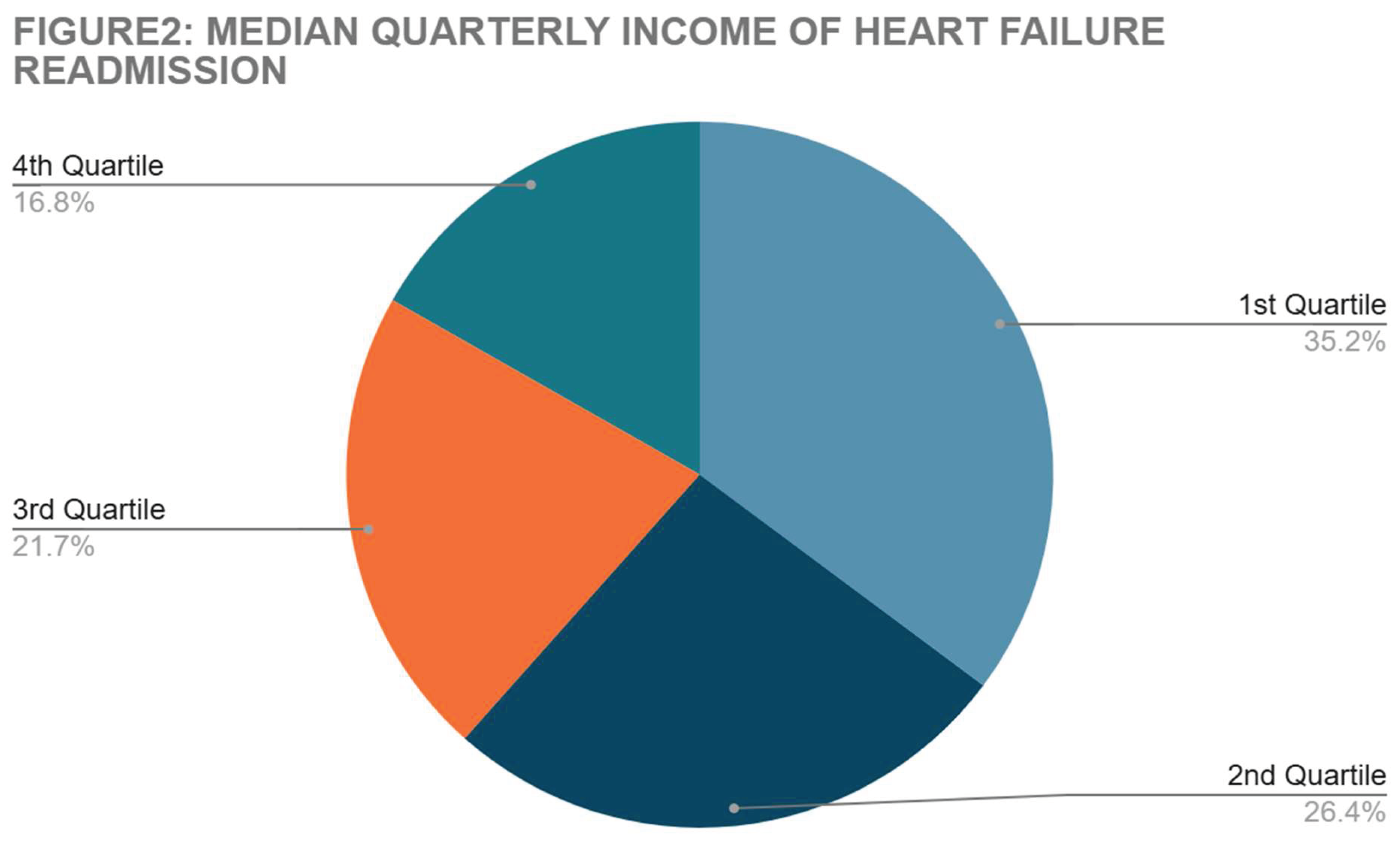

Median quarterly income was stratified in both 30 and 90 groups with secondary admission for heart failure. Results are summarized in

Figure 2.

Readmission causes in both 30- and 90-day day groups are summarized below in

Figure 3.

Comorbid conditions that held significant association with repeat admissions for heart failure in the 30, and 90 groups are summarized below in

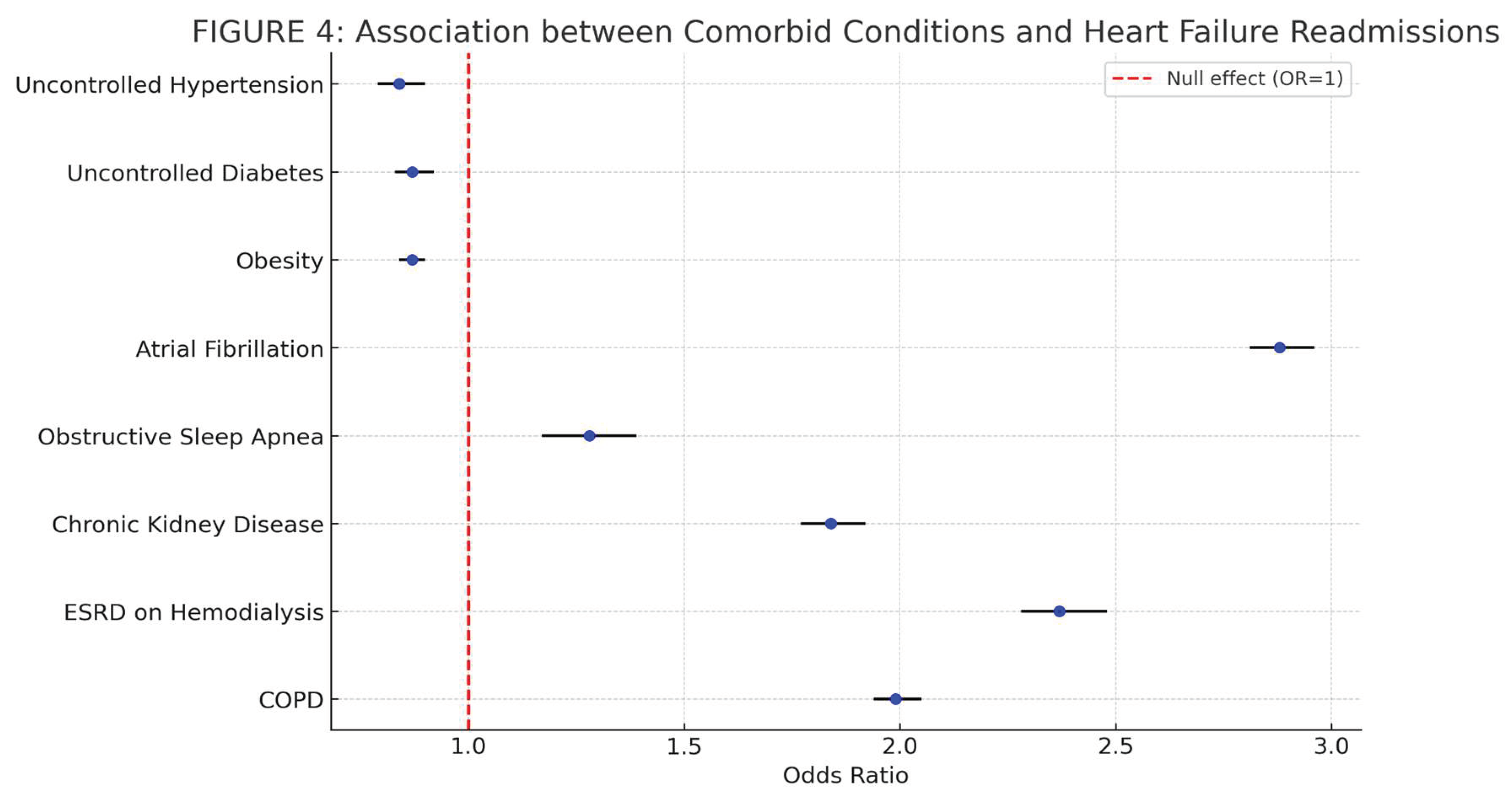

Table 3. Multivariate logistic regression was used for determining this association. Age, Sex, quarterly income, smoking, and alcohol abuse were the confounding factors used in the regression to determine the adjusted odds ratio. A two tailed p-value < 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance. The forest plot for the associations is shown in

Figure 4.

We stratified the population with readmission events for heart failure in both 30- and 90-day groups following discharge from a heart failure admission. The association between lower income strata (1st quartile of monthly income) and readmission events for heart failure were analyzed. This is summarized in

Table 4.

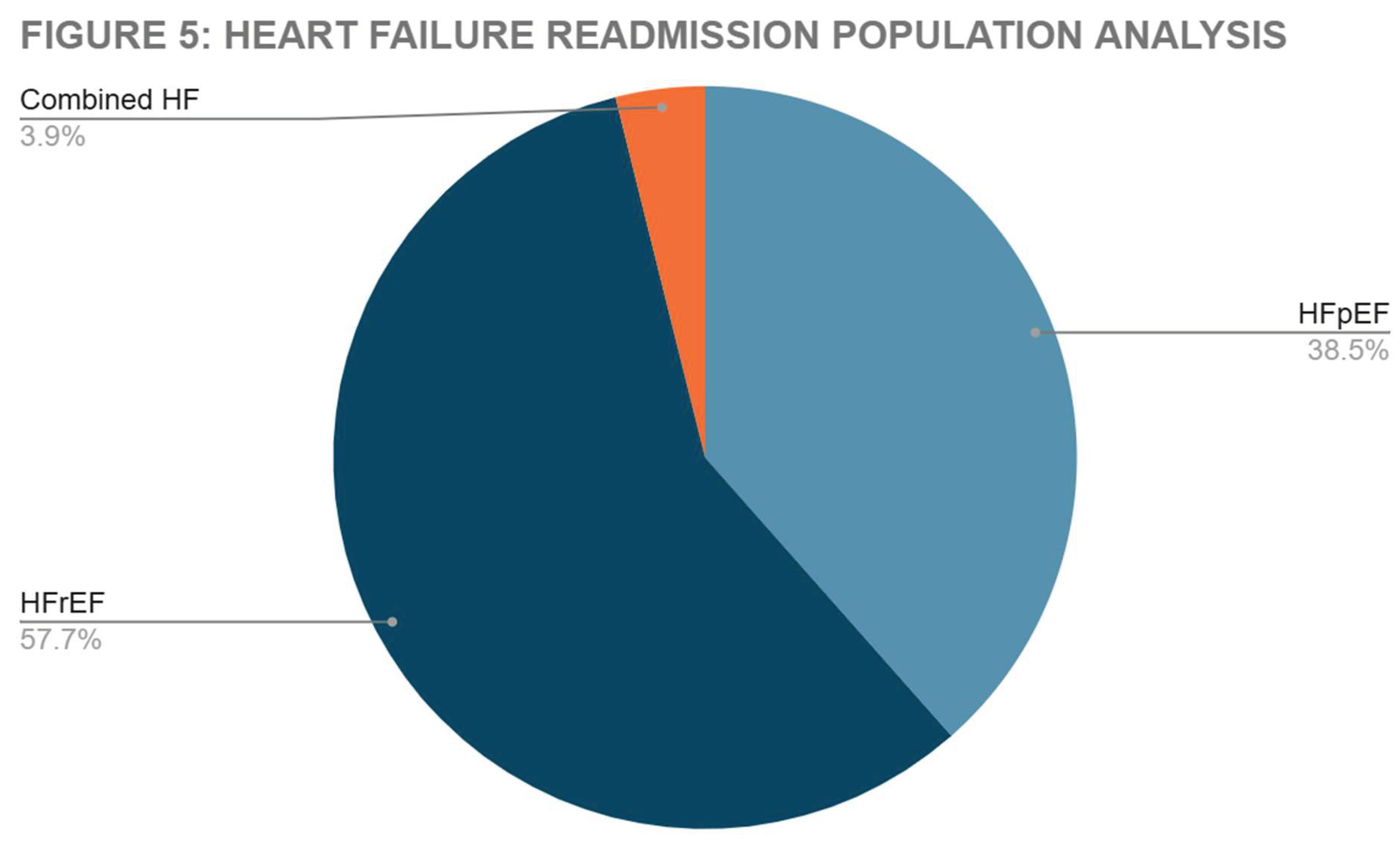

We analyzed the proportion of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF) and Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF) patients in the heart failure readmission pool. Results summarized in

Figure 5.

4. Discussion

The results of the readmission trends for CHF admissions as well as readmissions from the 2021 database highlights the healthcare resource burden associated with this diagnosis. When looking at data collected, patients with an initial primary diagnosis of CHF were noted to have 30- and 90-day re-admission rates of 5.558% and 7.699% respectively. When these rates are compared to those for similarly burdensome conditions like COPD, Asthma or cirrhosis we see that heart failure contributes to a significantly higher rate of re-admissions than those pathologies. [

8]. It may be noted that comorbid conditions and socioeconomic factors do contribute to this increased rate of readmissions. Likewise, some studies have shown that effective patient education can play a key role in nullifying this trend to some degree. [

8]. Looking at the results in

Table 2, when comparing the total hospital charges and length of hospital stay, this becomes evident. The total costs associated with both 30- and 90-day readmissions are similar to the costs of the index admission events. The length of hospital stay of the readmission events are also like that of the index admission events.

When looking at the associated comorbidities re-admission populations, we found that Atrial fibrillation has the highest prevalence followed by chronic kidney disease. Several clinical studies, including the CASTLE-AF Trial [

9] have shown that patients with concurrent diagnoses of both CHF and atrial fibrillation have a higher burden of congestive symptoms. The efficacy of restoration of sinus rhythm with pacing in prevention of cardiac remodeling in Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in my PACE randomized clinical trial [

10]. In HFpEF and HFmrEF, nearly 40% of patients have subclinical AF by 1 year. Baseline AF (atrial fibrillation) burden, even at low levels, is strongly associated with Heart Failure events [

11]. The mean age for both index admission as well as the readmission groups was found to be 70 in this analysis. The burden of CHF related hospital admissions has also found to be higher among the elderly [

12]. The higher prevalence of concomitant comorbidities in these patients combined with elderly patients having higher rates of hospital-related adverse events, (delirium and hospital acquired infections) may contribute to this correlation.

The interplay between CKD and CHF is complex- both pathophysiologically and due to the rate of morbid symptoms. While type 1 and 2 Cardiorenal Syndromes (CRS) may be explained by congestive nephropathy (secondary to elevated right filling pressures,) types 3 and 4 are the inverse, where elevated cardiac filling pressures are driven by poor GFR. [

13]. Combined and intensive diuretic strategies must be employed type 1 CRS, which is the most common cause of kidney injury in all CHF admissions. Conventional diuretic regimens may not be as successful in adequately diuresing patients with CRS, leading to residual volume retention therefore increasing the likelihood of readmission [

14].

Obesity was similarly prevalent in the re-admission pool for this study. In recent years, the prevalence of obesity in global populations has increased dramatically. The effects of increased this have direct impacts on many chronic health condition. Obesity paradox is yet another interesting pattern noted in current research. Obesity positively impacts the prognosis of patients with chronic illnesses such as chronic heart failure (CHF) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). [

15]

The evaluation of socioeconomic factors (

Figure 2 and

Table 4) showed a significance between lower socioeconomic status and increased numbers of heart failure related readmissions. These associations were noted even when comorbidities like atrial fibrillation, CKD, smoking and alcohol abuse were accounted for. Several similar studies correlate this data. Geography also has a notable role in the burden of CHF readmissions. It is noted that patients who have their primary residence located within disadvantaged regions have higher numbers of subsequent admissions. [

16]. As mentioned in the introduction section of the article, the effect of the economic factors in prevention of optimization of GDMT may contribute to this.

Higher prevalence of associated risk factors like smoking, alcohol abuse and obesity also play a key role. Analyzing the 30- and 90-day readmission events following initial admissions for congestive heart failure admission, readmissions for heart failure related complications was the most prevalent (

Figure 3). Coronary heart disease (CHD) is the most common underlying risk factor for CHF. Up to one-third of the patients who are hospitalized for HF each year in the United States have a history of myocardial infarction (MI). Although silent MI (SMI) could account for up to one-half of all MIs, only a few studies examined the relationship between SMI and risk of HF [

17].

Analyzing the association of comorbid conditions with heart failure related readmissions, Atrial fibrillation (AF), CKD, Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA), and End Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) had significant association (

Table 3 and

Figure 4). Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common arrhythmia among patients with heart failure (HF), and HF is the most common cause of mortality in this population. AF is frequently associated with pathological atrial myocardial dysfunction and remodeling, which can interact with the remodeling seen in CHF. Likewise, AF can be both cause or consequence of clinical HF, and the directionality varies between individual patients and across the spectrum of HF. AF is particularly common in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (defined as left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≥ 50%), with a prevalence ranging around 40-60%. When discussing treatment for those with both pathologies, initial trials note no significant advantage for a systematic rhythm control strategy HFREF, however newer data suggest there may be benefit from those with early ablation [

18]. In two recent trials, treatment with SGLT2 inhibitors resulted in a lower risk of worsening heart failure or cardiovascular death than placebo in patients with HFpEF. With patients who had both AF and HFpEF, SGLT2 inhibitors similarly improved prognosis. Analyses for subgroups of interest of patients with HFpEF likely to be at higher risk of AF (particularly those with older age or obesity) similarly indicated a consistent benefit with SGLT2 inhibitors. That subgroup in patients with HFpEF is those with a history of previous HF with LVEF ≤ 40%. [

19]. Diagnosis of HFpEF may require further investigation when seen in patients with co-morbid AF. Similarly to heart failure, AF is associated with similar changes in echocardiographic parameters as well as increases circulating natriuretic peptides that may blur the lines of forming a solid diagnosis. Symptomatic improvement with diuretic therapy supports the presence of HFpEF in patients with concomitant AF [

20].

When considering other comorbidities, OSA (obstructive sleep apnea) must be considered. Its prevalence is as high as 40% to 80% in patients with hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery disease, pulmonary hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and stroke. Despite its high prevalence in patients with heart disease and the vulnerability of cardiac patients to OSA-related stressors and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, OSA is often underrecognized and undertreated in cardiovascular practice [

21]. One trial of nightly positive airway pressure treatment of OSA included patients with HF and showed no improvement in clinical outcomes. However, conclusions derived from this trial must consider several important pitfalls that have been extensively discussed in the literature. With the role of positive airway pressure as the sole therapy for SDB in HF increasingly questioned, a critical examination of long-accepted concepts in this field is needed [

22]. The primary impact of ventilation and ventilatory efforts on left ventricular (LV) function in left ventricular dysfunction relate to how changes in intrathoracic pressure (ITP) alter the pressure gradients for venous return into the chest and LV ejection out of the chest. Spontaneous inspiratory efforts by decreasing ITP increase both pressure gradients, subsequently increasing venous blood flow and impeding LV ejection. This results in increased intrathoracic blood volume. In severe heart failure states when lung compliance is reduced, or airway resistance is increased these negative swings in ITP can be exacerbated leading to LV failure and acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema. By merely reversing these negative swings in ITP using non-invasive continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), these profoundly detrimental forces may be immediately reversed. These reversals lend to increased cardiovascular stability which may be rapidly obtained [

23].

A loss of glomerular filtration rate, seen in acute kidney injury (AKI) or chronic kidney disease (CKD), independently predicts mortality and accelerates the overall progression of cardiovascular disease and HF. Importantly, cardiac and renal diseases interact in a complex bidirectional and interdependent manner in both acute and chronic settings. From a pathophysiological perspective, cardiac and renal diseases share several common pathways, including inflammatory and direct, cellular immune-mediated mechanisms; stress-mediated and (neuro)hormonal responses; metabolic and nutritional changes including bone and mineral disorder, altered hemodynamic and acid-base or fluid status; and the development of anemia. To understand the important biochemical interactions between the two, classifications such as the cardio-renal syndromes were developed. This classification might lead to a more precise understanding of the complex interdependent pathophysiology of cardiac and renal diseases [

24].

5. Conclusions

The most notable conclusion formulated from this analysis is the significant association of lower economic status with subsequent heart failure readmissions. Some rationale derived from the data seen, is that socioeconomic factors may preclude timely optimization of GDMT therapy on an ambulatory basis. Looking at comorbid factors that hold significant association, Atrial Fibrillation and CKD were noted from our data. Chronic kidney disease leading to repeated admissions post hospitalization may be due to multiple causes. Most notably, reduced glomerular filtration leads to further fluid buildup which may increase the rate and severity of cardiac remodeling as well as overall HF morbidity and mortality. Atrial fibrillation has a more complex interplay in the pathology of HF. As mentioned, there is a unique bidirectionality with atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Both pathologies may lead to the development of the other. Early rhythm control may result in the prevention of cardiac remodeling as well decreasing intracardiac filling pressures: the primary pathophysiologic mechanisms driving HF exacerbations. Further clinical studies aimed at analyzing heart failure readmission rates with adequate patient education on optimization of GDMT as well as overcoming the socioeconomic barriers for GDMT optimization would be crucial in reducing the burden of heart failure readmissions. Early rhythm control strategy in patients with concomitant atrial fibrillation would be critical, not only in terms of reduction of readmission events, but also in the general disease course of congestive heart failure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, VJV. and AK.; methodology, VJV; software, Stata 18.5; validationSK, QY,AK. and VJV.; formal analysis, VJV.; investigation, AK,SK.; resources, QY.; data curation, QY.; writing—original draft preparation,VJV,SK,AK,QY.; writing—review and editing, QY,AK; visualization, VJV.; supervision, AK.; project administration, AK.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

HCUP NRD 2021 ( Publicly available database).

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Bueno H, Goñi C, Salguero-Bodes R, Palacios B, Vincent L, Moreno G, Rosillo N, Varela L, Capel M, Delgado J, Arribas F, Del Oro M, Ortega C, Bernal JL. Primary vs. Secondary Heart Failure Diagnosis: Differences in Clinical Outcomes, Healthcare Resource Utilization and Cost. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Mar 17;9:818525. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kwok CS, Abramov D, Parwani P, Ghosh RK, Kittleson M, Ahmad FZ, Al Ayoubi F, Van Spall HGC, Mamas MA. Cost of inpatient heart failure care and 30-day readmissions in the United States. Int J Cardiol. 2021 Apr 15;329:115-122. Epub 2020 Dec 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roger, V.L. Epidemiology of heart failure. Circ Res. 2013 Aug 30;113(6):646-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Narasimmaraj PR, Wadhera RK. Heart Failure Readmissions: A Measure of Quality or Social Vulnerability? JACC Heart Fail. 2023 Jan;11(1):124-125. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel J, Rassekh N, Fonarow GC, Deedwania P, Sheikh FH, Ahmed A, Lam PH. Guideline-Directed Medical Therapy for the Treatment of Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Drugs. 2023 Jun;83(9):747-759. Epub 2023 May 31. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mebazaa A, Davison B, Chioncel O, Cohen-Solal A, Diaz R, Filippatos G, Metra M, Ponikowski P, Sliwa K, Voors AA, Edwards C, Novosadova M, Takagi K, Damasceno A, Saidu H, Gayat E, Pang PS, Celutkiene J, Cotter G. Safety, tolerability and efficacy of up-titration of guideline-directed medical therapies for acute heart failure (STRONG-HF): a multinational, open-label, randomised, trial. Lancet. 2022 Dec 3;400(10367):1938-1952. Epub 2022 Nov 7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-Gracia J, Demissei BG, Ter Maaten JM, Cleland JG, O’Connor CM, Metra M, Ponikowski P, Teerlink JR, Cotter G, Davison BA, Givertz MM, Bloomfield DM, Dittrich H, Damman K, Pérez-Calvo JI, Voors AA. Prevalence, predictors and clinical outcome of residual congestion in acute decompensated heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2018 May 1;258:185-191. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements L, Frazier SK, Lennie TA, Chung ML, Moser DK. Improvement in Heart Failure Self-Care and Patient Readmissions with Caregiver Education: A Randomized Controlled Trial. West J Nurs Res. 2023 May;45(5):402-415. Epub 2022 Dec 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brachmann J, Sohns C, Andresen D, Siebels J, Sehner S, Boersma L, Merkely B, Pokushalov E, Sanders P, Schunkert H, Bänsch D, Dagher L, Zhao Y, Mahnkopf C, Wegscheider K, Marrouche NF. Atrial Fibrillation Burden and Clinical Outcomes in Heart Failure: The CASTLE-AF Trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2021 May;7(5):594-603. Epub 2021 Feb 24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Infeld M, Wahlberg K, Cicero J, Plante TB, Meagher S, Novelli A, Habel N, Krishnan AM, Silverman DN, LeWinter MM, Lustgarten DL, Meyer M. Effect of Personalized Accelerated Pacing on Quality of Life, Physical Activity, and Atrial Fibrillation in Patients With Preclinical and Overt Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction: The myPACE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2023 Mar 1;8(3):213-221. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Patel RB, Reddy VY, Komtebedde J, Wegerich SW, Sekaric J, Swarup V, Walton A, Laurent G, Chetcuti S, Rademann M, Bergmann M, McKenzie S, Bugger H, Bruno RR, Herrmann HC, Nair A, Gupta DK, Lim S, Kapadia S, Gordon R, Vanderheyden M, Noel T, Bailey S, Gertz ZM, Trochu JN, Cutlip DE, Leon MB, Solomon SD, van Veldhuisen DJ, Auricchio A, Shah SJ. Atrial Fibrillation Burden and Atrial Shunt Therapy in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2023 Oct;11(10):1351-1362. Epub 2023 Jul 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee WY, Capra AM, Jensvold NG, Gurwitz JH, Go AS; Epidemiology, Practice, Outcomes, and Cost of Heart Failure (EPOCH) Study. Gender and risk of adverse outcomes in heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2004 Nov 1;94(9):1147-52. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar U, Wettersten N, Garimella PS. Cardiorenal Syndrome: Pathophysiology. Cardiol Clin. 2019 Aug;37(3):251-265. Epub 2019 May 21. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chávez-Iñiguez JS, Ibarra-Estrada M, Sánchez-Villaseca S, Romero-González G, Font-Yañez JJ, De la Torre-Quiroga A, de Quevedo AA, Romero-Muñóz A, Maggiani-Aguilera P, Chávez-Alonso G, Gómez-Fregoso J, García-García G. The Effect in Renal Function and Vascular Decongestion in Type 1 Cardiorenal Syndrome Treated with Two Strategies of Diuretics, a Pilot Randomized Trial. BMC Nephrol. 2022 Jan 3;23(1):3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Giri Ravindran S, Saha D, Iqbal I, Jhaveri S, Avanthika C, Naagendran MS, Bethineedi LD, Santhosh T. The Obesity Paradox in Chronic Heart Disease and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Cureus. 2022 Jun 5;14(6):e25674. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kind AJ, Jencks S, Brock J, Yu M, Bartels C, Ehlenbach W, Greenberg C, Smith M. Neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and 30-day rehospitalization: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014 Dec 2;161(11):765-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Soliman, EZ. Silent myocardial infarction and risk of heart failure: Current evidence and gaps in knowledge. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2019 May;29(4):239-244. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Reddy YNV, Borlaug BA, Gersh BJ. Management of Atrial Fibrillation Across the Spectrum of Heart Failure With Preserved and Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circulation. 2022 Jul 26;146(4):339-357. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Fauchier L, Bisson A, Bodin A. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and atrial fibrillation: recent advances and open questions. BMC Med. 2023 Feb 13;21(1):54. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kotecha D, Lam CS, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Van Gelder IC, Voors AA, Rienstra M. Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction and Atrial Fibrillation: Vicious Twins. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Nov 15;68(20):2217-2228. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeghiazarians Y, Jneid H, Tietjens JR, Redline S, Brown DL, El-Sherif N, Mehra R, Bozkurt B, Ndumele CE, Somers VK. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021 Jul 20;144(3):e56-e67. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000988. Epub 2021 Jun 21. Erratum in: Circulation. 2022 Mar 22;145(12):e775. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javaheri S, Brown LK, Abraham WT, Khayat R. Apneas of Heart Failure and Phenotype-Guided Treatments: Part One: OSA. Chest. 2020 Feb;157(2):394-402. Epub 2019 Apr 29. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alvarado AC, Pinsky MR. Cardiopulmonary interactions in left heart failure. Front Physiol. 2023 Aug 8;14:1237741. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schefold JC, Filippatos G, Hasenfuss G, Anker SD, von Haehling S. Heart failure and kidney dysfunction: epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016 Oct;12(10):610-23. Epub 2016 Aug 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair R, Lak H, Hasan S, Gunasekaran D, Babar A, Gopalakrishna KV; “Reducing All-cause 30-day Hospital Readmissions for Patients Presenting with Acute Heart Failure Exacerbations: A Quality Improvement Initiative,” 2020 Mar 25;12(3):e7420. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).