Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

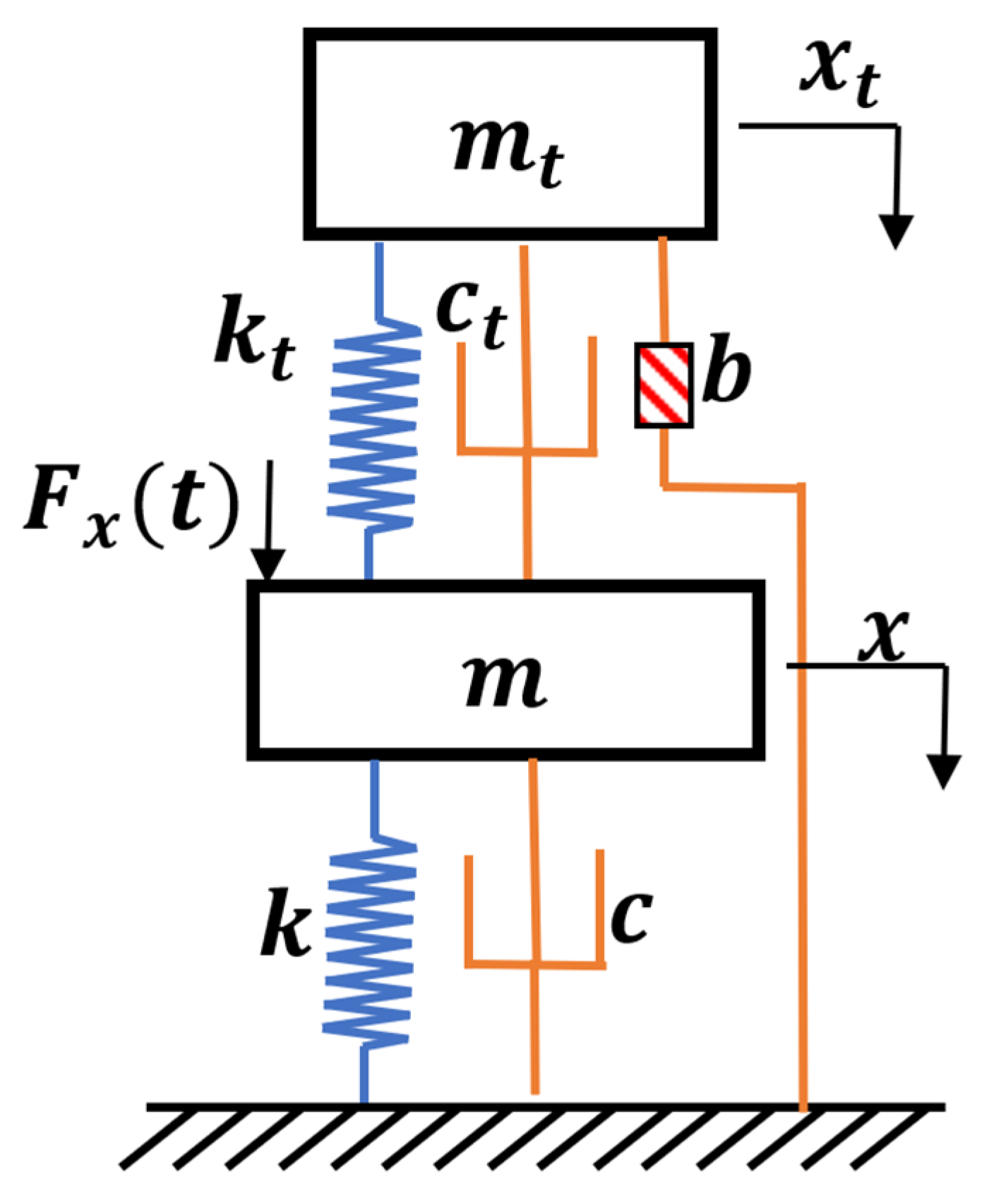

1. Introduction to TMDI Damper

2. The methodology of the Derivation of Optimum TMDI Parameters

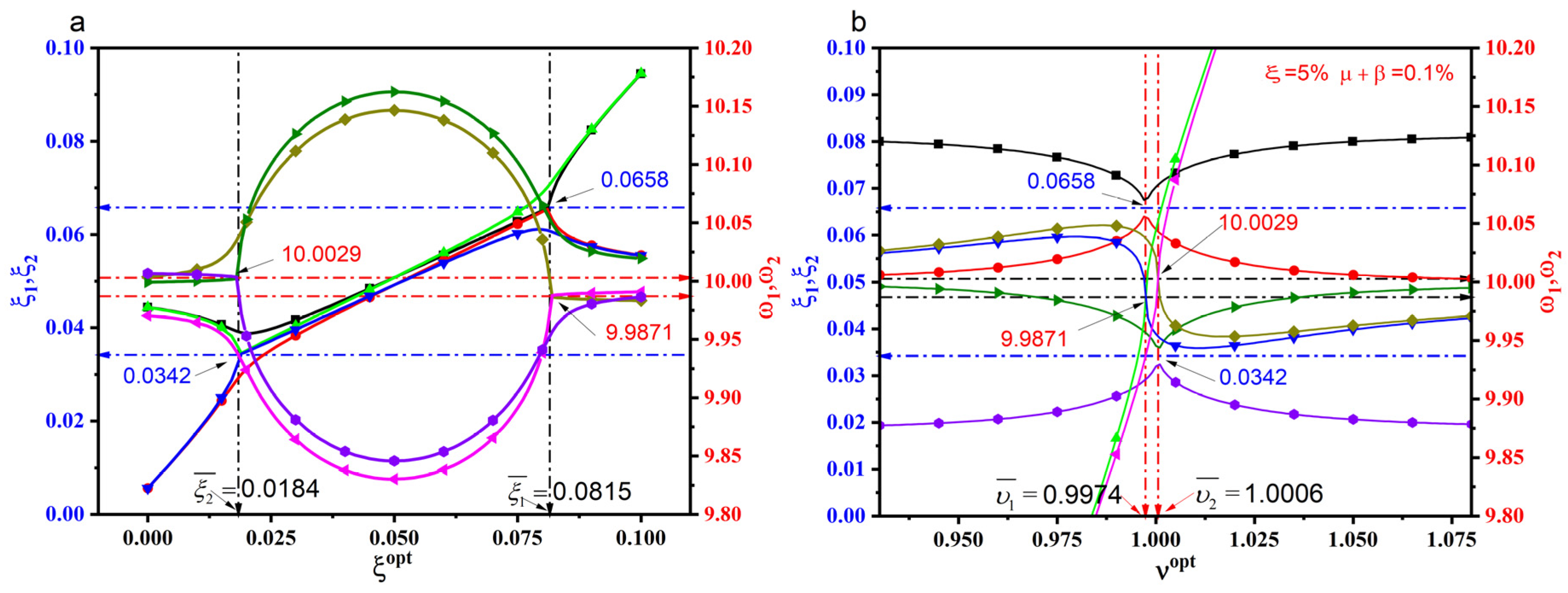

3. Equal Modal Damping and Frequency of TMDI System

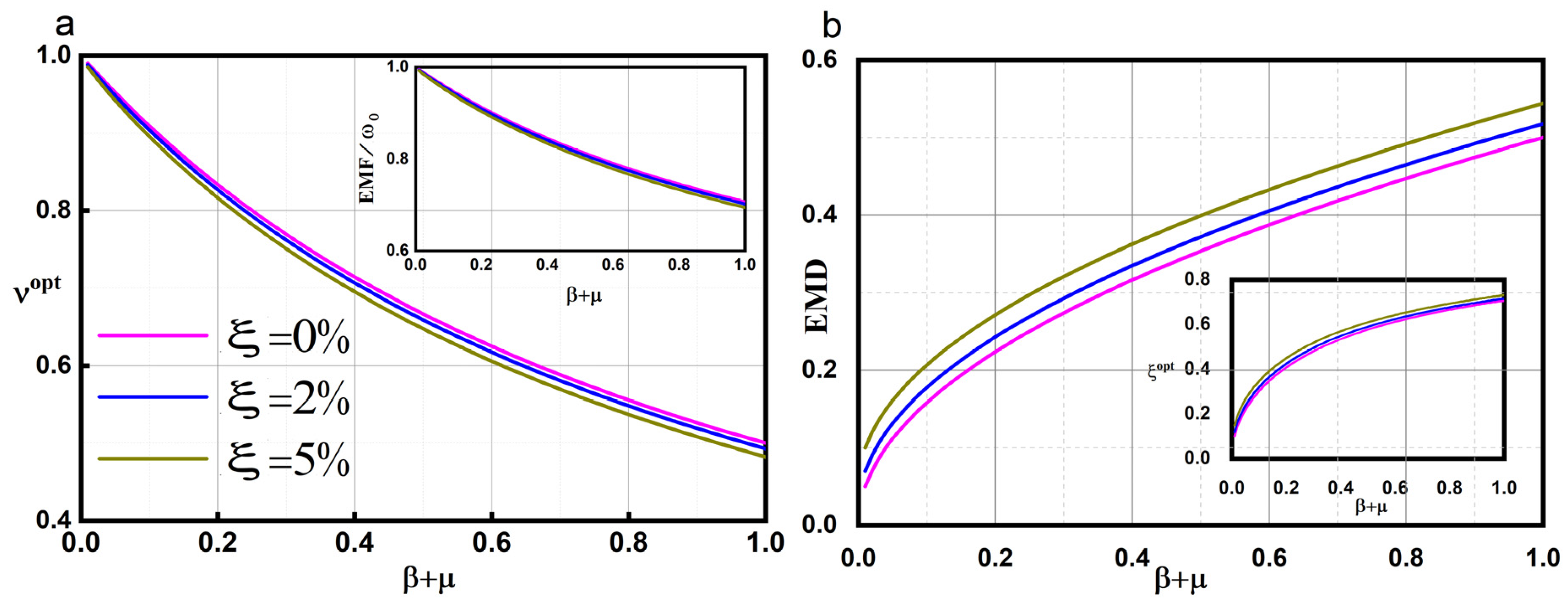

4. Equal Modality on Optimal Parameters for TMDI

5. Effect of Absolute Mass Ratio for TMDI

6. Procedure for Estimating Optimal Parameters in a TMDI Controlled Structure

- Estimate Natural Frequency: Using the stiffness and mass properties of the main system, estimate the natural frequency:

- Determine Mass and Damping Ratios: Evaluate Mass Ratio () and Inertance ratio based on the structural control strategy using TMDI. The Absolute Mass Ratio is calculated as . Determine Structural Damping Ratio (), as per the relevant standard.

- Calculate Optimal Frequency Ratio () using the equation 27, where /

- Compute Equal Modal Frequency (EMF) using equation 17:

- Estimate Optimal Damping Ratios , using equation 26,

- Calculate Equal Modal Damping (EMD) using equation 17: where,

- Determine Effective Optimal Damping Roots: The optimal damping roots are: .

- Proceed to Compute Parameters R₁ to R₄ as per equation 28.

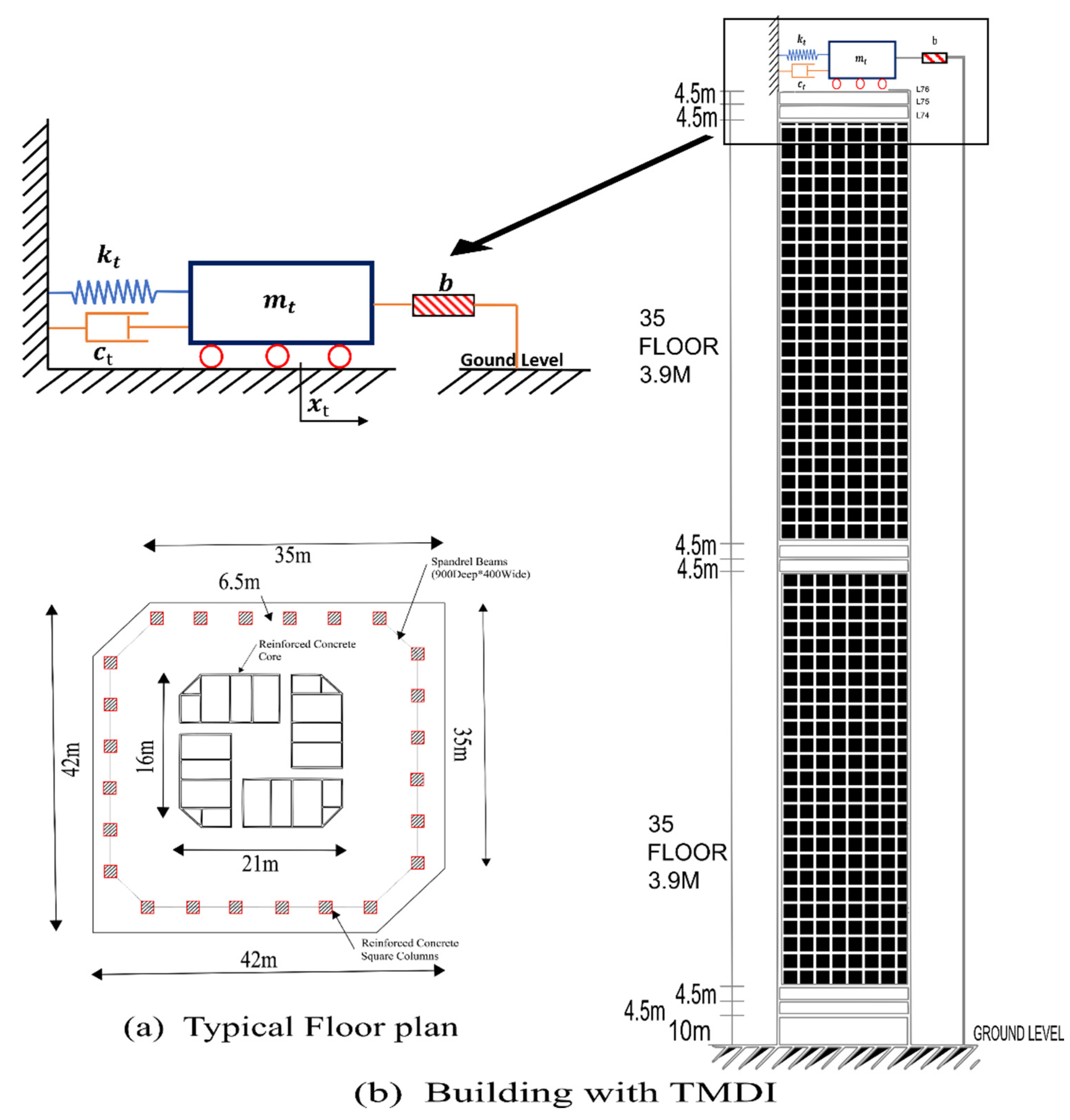

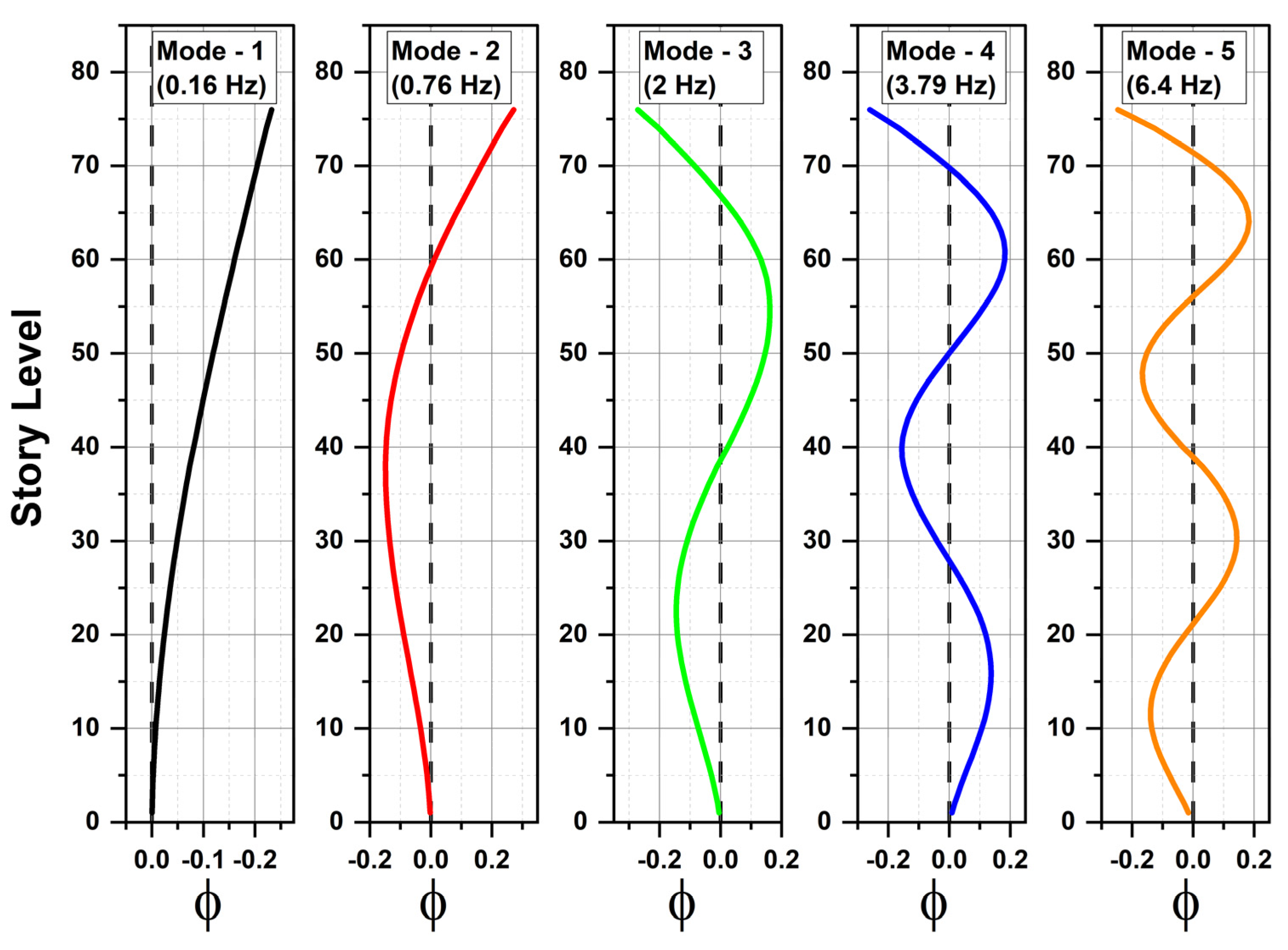

7. Study of Benchmark Tall Building

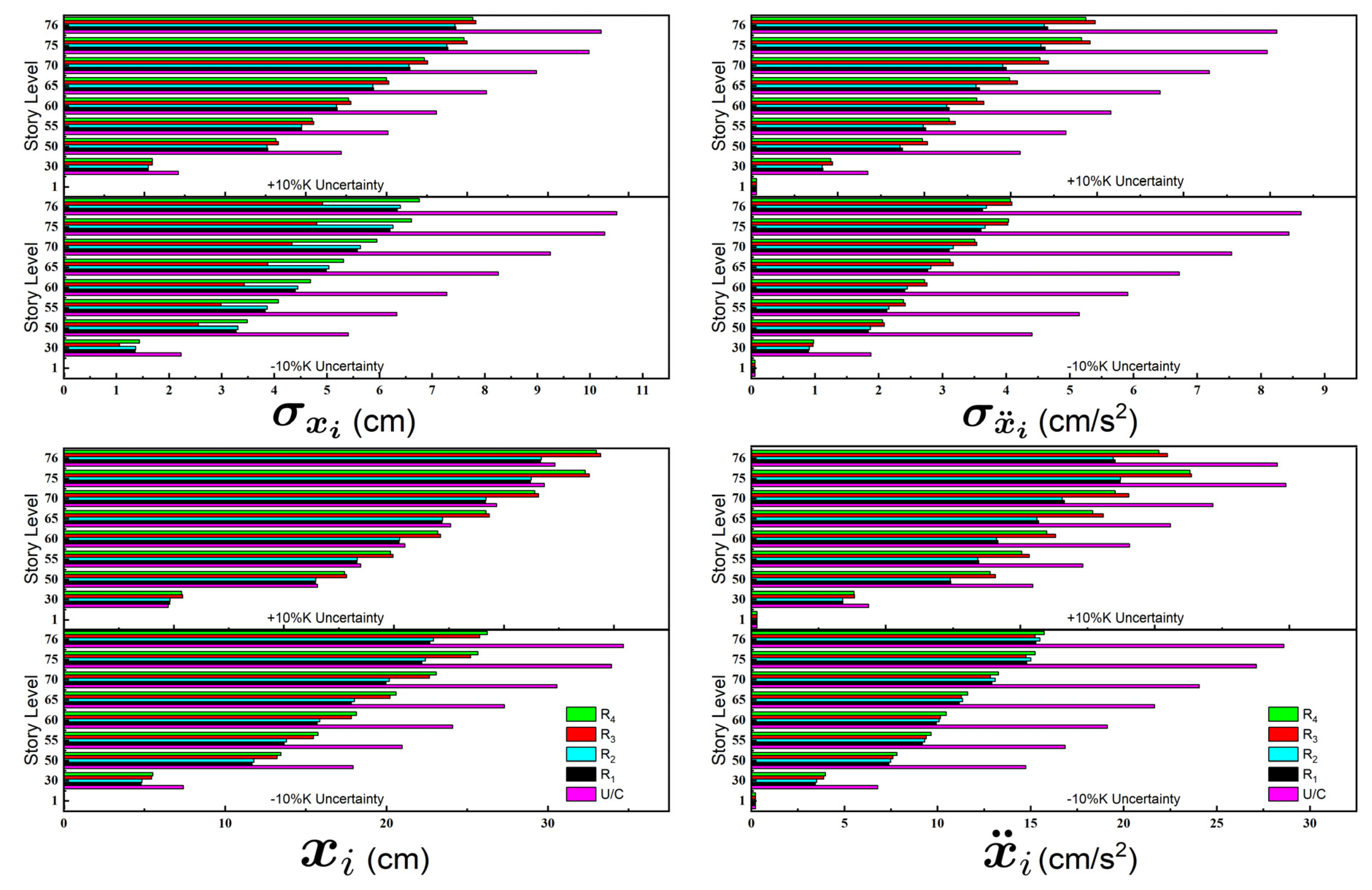

8. Performance Measures of Benchmark Building

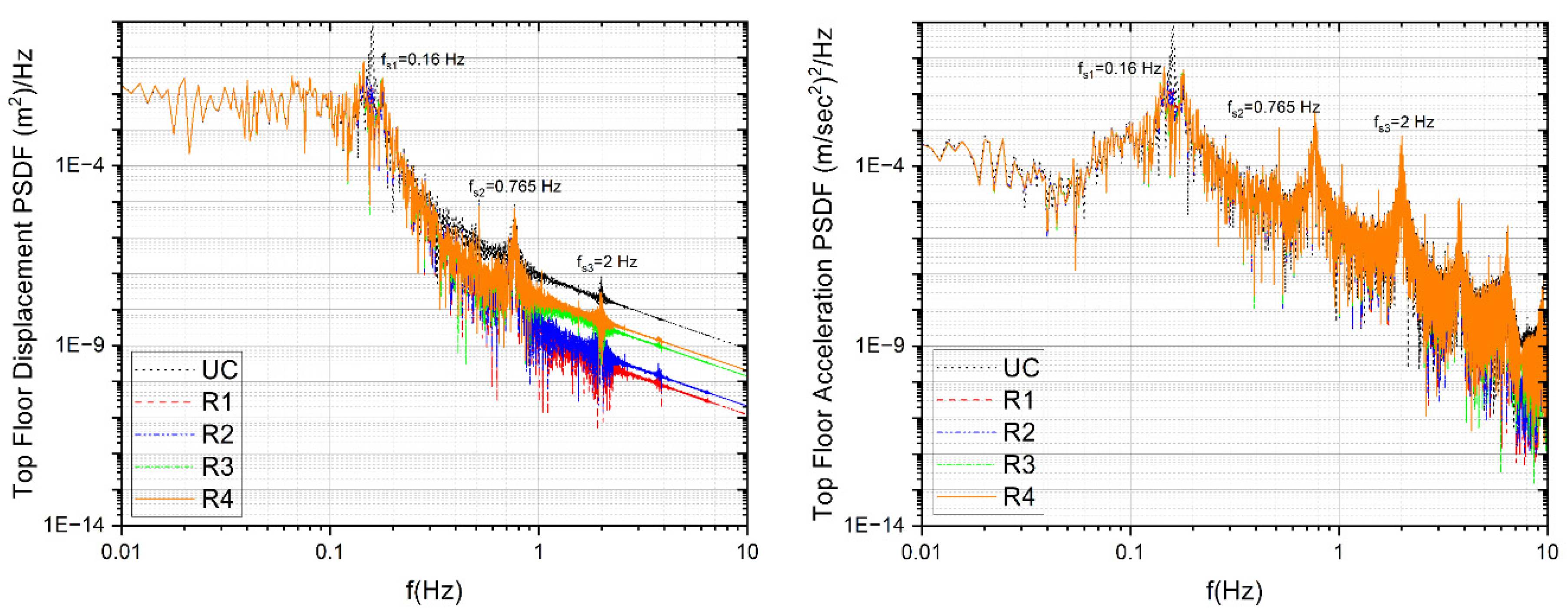

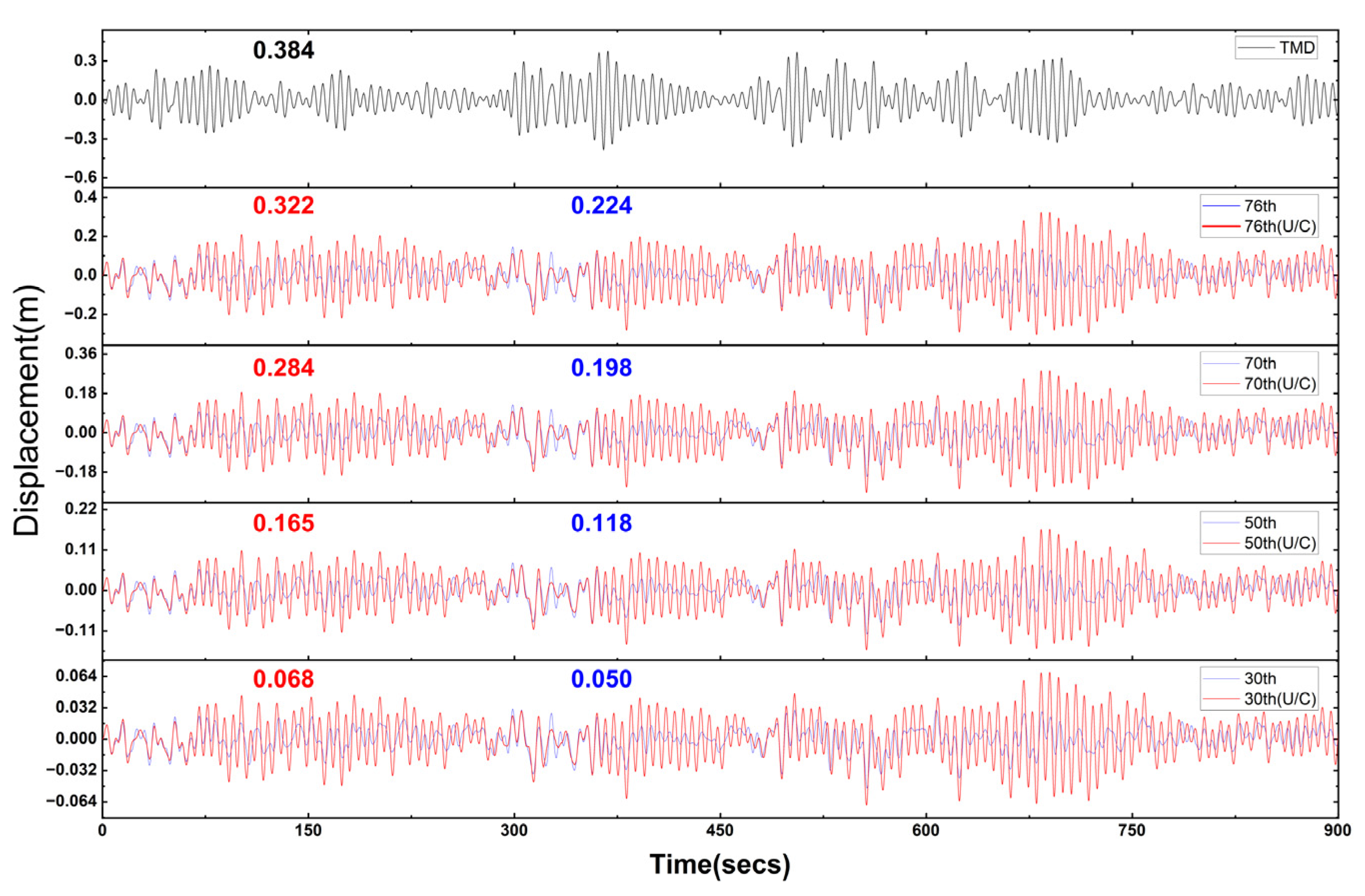

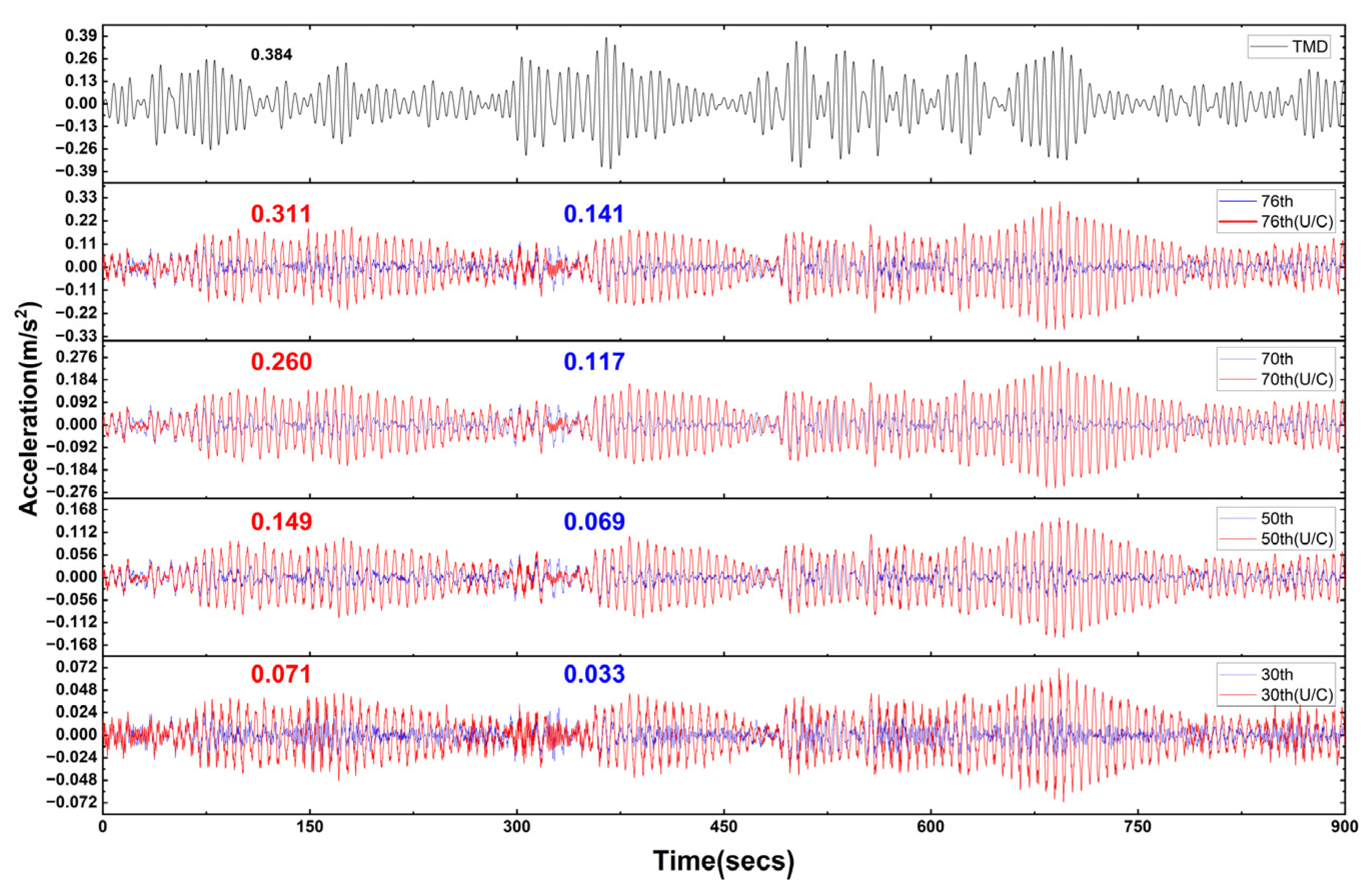

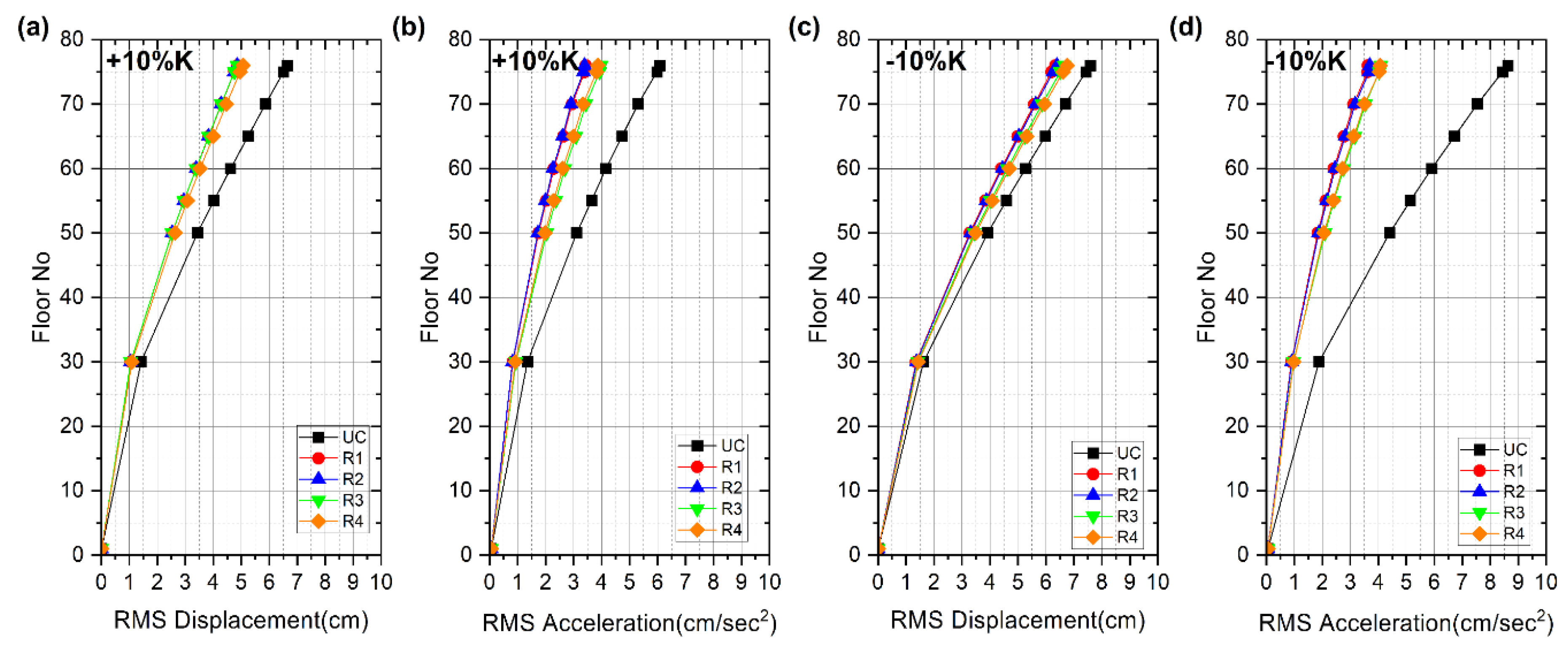

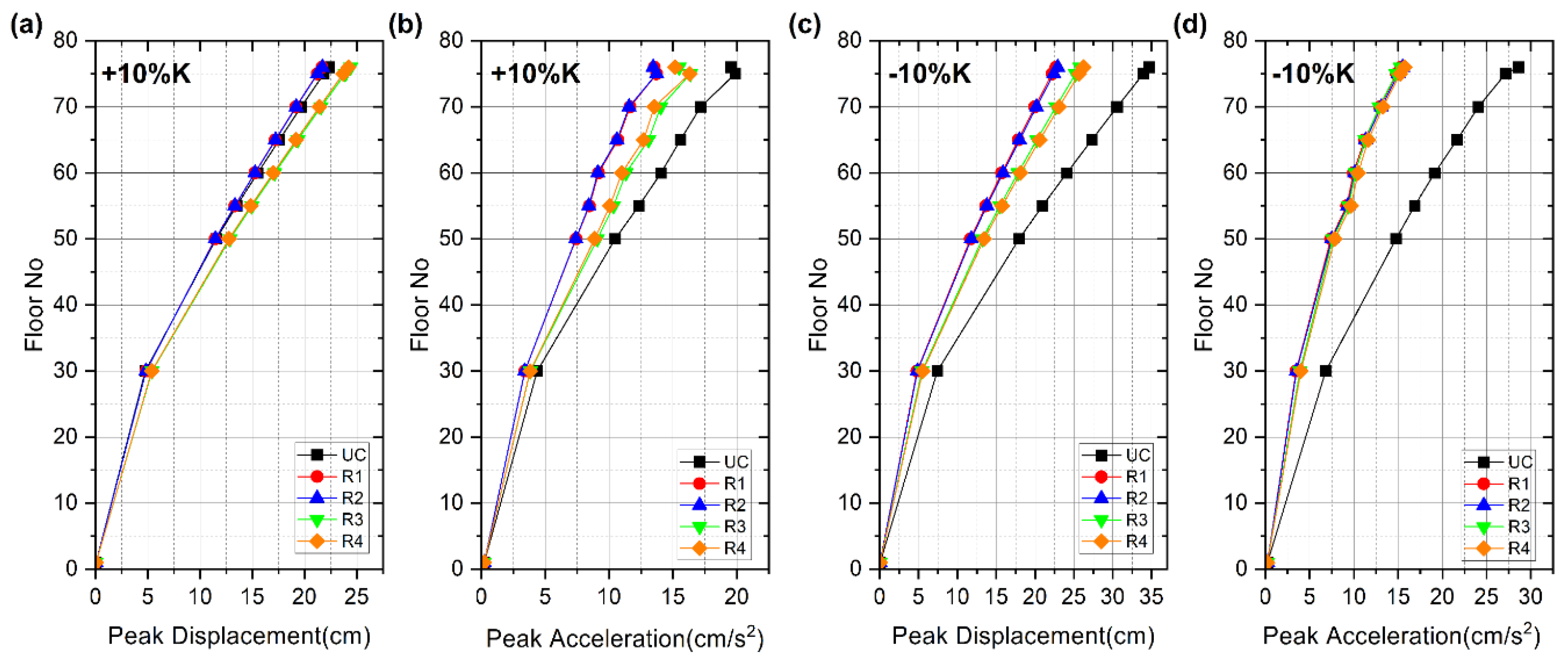

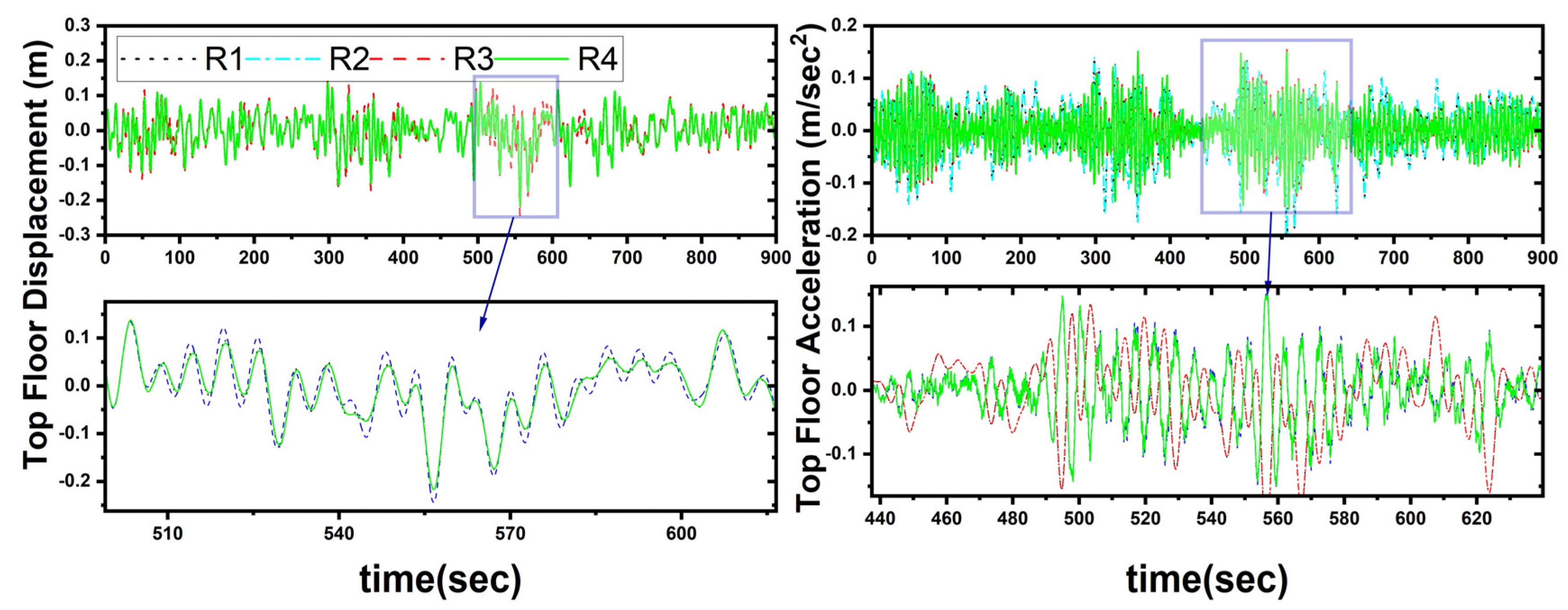

9. Assessment of Structural Response Characteristics

10. System Response Evaluation and Insight

11. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TMD | Tuned Mass Damper |

| TMDI | Tune Mass Damper Inerter |

| SDOF | Single Degree Of Freedom |

| MDOF | Multi Degree Of Freedom |

| EMF | Equal Modal Frequency |

| EMD | Equal Modal Damping |

| PSDFs | Power Spectral Density Functions |

| UC | Uncontrolled Structures |

| RMS | Root M |

References

- Taranath, B.S. Wind and Earthquake Resistant Buildings; 0 ed.; CRC Press, 2004; ISBN 978-0-8493-3809-0.

- Simiu, E.; Yeo, D. Wind Effects on Structures: Modern Structural Design for Wind; Fourth edition.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 2019; ISBN 978-1-119-37593-7. [Google Scholar]

- Elias, S.; Matsagar, V. Research Developments in Vibration Control of Structures Using Passive Tuned Mass Dampers. Annu. Rev. Control 2017, 44, 129–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaralis, A.; Petrini, F. Wind-Induced Vibration Mitigation in Tall Buildings Using the Tuned Mass-Damper-Inerter. J. Struct. Eng. 2017, 143, 04017127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samali, B.; Kwok, K.C.S.; Wood, G.S.; Yang, J.N. Wind Tunnel Tests for Wind-Excited Benchmark Building. J. Eng. Mech. 2004, 130, 447–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frahm, H. Device for Damping Vibrations of Bodies 1911.

- Hartog, J.P.D. Mechanical Vibrations; Courier Corporation, 1985; ISBN 978-0-486-64785-2.

- Sadek, F.; Mohraz, B.; Taylor, A.W.; Chung, R.M. A METHOD OF ESTIMATING THE PARAMETERS OF TUNED MASS DAMPERS FOR SEISMIC APPLICATIONS. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1997, 26, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Structural Motion Engineering; ISBN 978-3-319-06281-5.

- Design Optimization of Active and Passive Structural Control Systems:; Lagaros, N.D., Plevris, V., Mitropoulou, C.C., Eds.; IGI Global, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4666-2029-2.

- Xu, K.; Dai, Q.; Bi, K.; Fang, G.; Ge, Y. Closed-form Design Formulas of TMDI for Suppressing Vortex-induced Vibration of Bridge Structures. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2022, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, S.J.; Jangid, R.S. Design of Tuned Liquid Sloshing Dampers Using Nonlinear Constraint Optimization for Across-Wind Response Control of Benchmark Tall Building. Structures 2021, 33, 2675–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, N.U.; Jangid, R.S. Optimum Parameters of Tuned Inerter Damper for Damped Structures. J. Sound Vib. 2022, 537, 117218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.; Jangid, R.S. Optimum Parameters of Tuned Mass Damper-Inerter for Damped Structure under Seismic Excitation. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2022, 10, 1322–1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisal, A.Y.; Jangid, R.S. Dynamic Response of Structure with Tuned Mass Friction Damper. Int. J. Adv. Struct. Eng. 2016, 8, 363–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, S.J.; Patil, V.B.; Jangid, R.S. Optimization of MR Dampers for Wind-Excited Benchmark Tall Building. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2022, 27, 04022048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, M.; Kim, Y.H. Structural Dynamics: Theory and Computation; Springer, 2018; ISBN 978-3-319-94743-3.

- Hart, G.C.; Wong, K. Structural Dynamics for Structural Engineers; John Wiley & Sons: New York Weinheim, 2000; ISBN 978-0-471-36169-5. [Google Scholar]

- Connor, J.; Laflamme, S. Structural Motion Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2014; ISBN 978-3-319-06280-8. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, S.S. Mechanical Vibrations; Addison-Wesley, 1990; ISBN 978-0-201-50156-8.

- Warburton, G.B. Optimum Absorber Parameters for Various Combinations of Response and Excitation Parameters. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1982, 10, 381–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaverde, R. Reduction Seismic Response with Heavily-Damped Vibration Absorbers. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 1985, 13, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sladek, J.R.; Klingner, R.E. Effect of Tuned-Mass Dampers on Seismic Response. J. Struct. Eng. 1983, 109, 2004–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquot, R.G. Optimal Dynamic Vibration Absorbers for General Beam Systems. J. Sound Vib. 1978, 60, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.C. A Method for Tuning Tuned Mass Dampers for Seismic Applications. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2013, 42, 1103–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, J.C. System Intrinsic, Damping Maximized, Tuned Mass Dampers for Seismic Applications. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2012, 19, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.M.; Jaiswal, O.R. Optimum Parameters of Variant Tuned Mass Damper Using Equal Eigenvalue Criterion. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 52, 2852–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.B.; Jangid, R.S. Closed-Form Derivation of Optimum Tuned Mass Damper Parameter Based on Modal Multiplicity Criteria. ASPS Conf. Proc. 2022, 1, 1041–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.B.; Jangid, R.S. Optimal Parameters for Tuned Mass Dampers and Examination of Equal Modal Frequency and Damping Criteria. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 7159–7173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, L.; Giaralis, A. Optimal Design of a Novel Tuned Mass-Damper–Inerter (TMDI) Passive Vibration Control Configuration for Stochastically Support-Excited Structural Systems. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 2014, 38, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, C.; Smith, M.C. Laboratory Experimental Testing of Inerters. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 44th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control; IEEE: Seville, Spain, 2005; pp. 3351–3356. [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe, F.; Smith, M.C. Analytical Solutions for Optimal Ride Comfort and Tyre Grip for Passive Vehicle Suspensions. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2009, 47, 1229–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, T.L.; Smith, K.S. Mechanical Vibrations: Modeling and Measurement; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-52343-5. [Google Scholar]

- Barredo, E.; Blanco, A.; Colín, J.; Penagos, V.M.; Abúndez, A.; Vela, L.G.; Meza, V.; Cruz, R.H.; Mayén, J. Closed-Form Solutions for the Optimal Design of Inerter-Based Dynamic Vibration Absorbers. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2018, 144, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzeski, P.; Pavlovskaia, E.; Kapitaniak, T.; Perlikowski, P. The Application of Inerter in Tuned Mass Absorber. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2015, 70, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, F.; Jafari, M. Investigation Approaches to Quantify Wind-Induced Load and Response of Tall Buildings: A Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 62, 102376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, H.; Tamura, Y.; Ueda, H.; Hibi, K. Dynamic Wind Pressures Acting on a Tall Building Model — Proper Orthogonal Decomposition. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1997, 69–71, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Nagarajaiah, S.; Shi, W.; Zhou, Y. Study on Adaptive-passive Eddy Current Pendulum Tuned Mass Damper for Wind-induced Vibration Control. Struct. Des. Tall Spec. Build. 2020, 29, e1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, A.E. Vibration Control of a Tall Benchmark Building under Wind and Earthquake Excitation. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 2021, 26, 04021005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, X. Bidirectional Wind Response Control of 76-Story Benchmark Building Using Active Mass Damper with a Rotating Actuator. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2018, 25, e2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.N.; Agrawal, A.K.; Samali, B.; Wu, J.-C. Benchmark Problem for Response Control of Wind-Excited Tall Buildings. J. Eng. Mech. 2004, 130, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Bi, K.; Hao, H. Inerter-Based Structural Vibration Control: A State-of-the-Art Review. Eng. Struct. 2021, 243, 112655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagg, D.J. A Review of the Mechanical Inerter: Historical Context, Physical Realisations and Nonlinear Applications. Nonlinear Dyn. 2021, 104, 13–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Cheng, Z.; Jia, G.; Shi, Z. Energy Analysis of an Inerter-enhanced Floating Floor Structure (In-FFS) under Seismic Loads. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2022, 51, 3111–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaveh, A.; Fahimi Farzam, M.; Hojat Jalali, H. Statistical Seismic Performance Assessment of Tuned Mass Damper Inerter. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, M.Z.Q.; Shu, Z.; Huang, L. Analysis and Optimisation for Inerter-Based Isolators via Fixed-Point Theory and Algebraic Solution. J. Sound Vib. 2015, 346, 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ikago, K. Optimal Design of Nontraditional Tuned Mass Damper for Base-Isolated Building. J. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 27, 2841–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krenk, S. Resonant Inerter Based Vibration Absorbers on Flexible Structures. J. Frankl. Inst. 2019, 356, 7704–7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Yang, J.; Jiang, J.Z. Tuning Methods for Tuned Inerter Dampers Coupled to Nonlinear Primary Systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 2022, 107, 1663–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, M.; Kim, Y.H. Structural Dynamics: Theory and Computation; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2019; ISBN 978-3-319-94742-6. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, A.K. Dynamics of Structures: Theory and Applications to Earthquake Engineering; Pearson Always learning; Fifth edition.; Pearson: Hoboken, NJ, 2017; ISBN 978-0-13-455512-6. [Google Scholar]

- SSTL : Structural Control Benchmarks. Available online: https://sstl.cee.illinois.edu/benchmarks/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Kang, J.; Ikago, K. Seismic Control of Multidegree-of-freedom Structures Using a Concentratedly Arranged Tuned Viscous Mass Damper. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 52, 4708–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Roots | RMS response | Peak response | ||||||||||

| 0.533 | 0.359 | 0.537 | 0.428 | 0.533 | 0.359 | 0.696 | 0.453 | 0.712 | 0.518 | 0.696 | 0.453 | |

| 0.536 | 0.361 | 0.540 | 0.430 | 0.536 | 0.361 | 0.710 | 0.457 | 0.726 | 0.521 | 0.710 | 0.457 | |

| 0.550 | 0.391 | 0.553 | 0.457 | 0.550 | 0.391 | 0.744 | 0.483 | 0.759 | 0.555 | 0.744 | 0.483 | |

| 0.555 | 0.395 | 0.558 | 0.461 | 0.555 | 0.395 | 0.773 | 0.488 | 0.788 | 0.565 | 0.773 | 0.488 | |

| Opt. Para. | Un-cont. | |||||||||

| – | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| – | 0.9852 | 0.9950 | 0.9852 | 0.9950 | ||||||

| – | 0.0998 | 0.1001 | 0.0502 | 0.0502 | ||||||

| Floor No. | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| 30 | 2.15 | 2.02 | 1.17 | 0.82 | 1.17 | 0.83 | 1.20 | 0.88 | 1.21 | 0.89 |

| 50 | 5.22 | 4.78 | 2.81 | 1.70 | 2.82 | 1.71 | 2.89 | 1.86 | 2.92 | 1.88 |

| 55 | 6.11 | 5.59 | 3.28 | 1.97 | 3.29 | 1.98 | 3.38 | 2.16 | 3.41 | 2.18 |

| 60 | 7.02 | 6.42 | 3.77 | 2.23 | 3.78 | 2.24 | 3.88 | 2.44 | 3.91 | 2.47 |

| 65 | 7.97 | 7.31 | 4.26 | 2.57 | 4.28 | 2.58 | 4.39 | 2.81 | 4.43 | 2.84 |

| 70 | 8.92 | 8.18 | 4.77 | 2.87 | 4.79 | 2.89 | 4.92 | 3.14 | 4.96 | 3.18 |

| 75 | 9.92 | 9.14 | 5.29 | 3.33 | 5.32 | 3.35 | 5.46 | 3.62 | 5.51 | 3.66 |

| 76 | 10.14 | 9.35 | 5.41 | 3.36 | 5.43 | 3.38 | 5.58 | 3.66 | 5.63 | 3.69 |

| TMD | – | – | 11.44 | 11.43 | 11.37 | 11.59 | 15.59 | 15.37 | 15.61 | 15.69 |

| Opt. Para. | Un-cont. | |||||||||

| – | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||||||

| – | 0.9852 | 0.9950 | 0.9852 | 0.9950 | ||||||

| – | 0.0998 | 0.1001 | 0.0502 | 0.0502 | ||||||

| Floor No. | ||||||||||

| 1 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 0.21 |

| 30 | 6.84 | 7.14 | 5.01 | 3.39 | 5.10 | 3.36 | 5.32 | 3.57 | 5.52 | 3.50 |

| 50 | 16.59 | 14.96 | 11.88 | 6.93 | 12.10 | 7.06 | 12.65 | 7.80 | 13.13 | 8.28 |

| 55 | 19.41 | 17.48 | 13.82 | 8.46 | 14.08 | 8.53 | 14.73 | 9.30 | 15.29 | 9.75 |

| 60 | 22.34 | 19.95 | 15.81 | 9.18 | 16.11 | 9.26 | 16.86 | 10.12 | 17.51 | 10.34 |

| 65 | 25.35 | 22.58 | 17.83 | 10.55 | 18.19 | 10.65 | 19.04 | 11.57 | 19.78 | 11.75 |

| 70 | 28.41 | 26.04 | 19.88 | 11.77 | 20.28 | 11.90 | 21.25 | 12.85 | 22.07 | 13.04 |

| 75 | 31.59 | 30.33 | 22.00 | 13.30 | 22.44 | 13.45 | 23.53 | 14.48 | 24.44 | 14.70 |

| 76 | 32.30 | 31.17 | 22.48 | 14.12 | 22.93 | 14.24 | 24.04 | 15.07 | 24.98 | 15.22 |

| TMD | – | – | 38.44 | 38.40 | 38.35 | 39.08 | 53.78 | 53.00 | 55.29 | 55.58 |

| Root | Stiffness Uncertainty |

RMS response | Peak response | ||||||||||

| ΔK = +10% | 0.730 | 0.565 | 0.734 | 0.613 | 0.730 | 0.565 | 0.971 | 0.692 | 0.991 | 0.729 | 0.971 | 0.701 | |

| ΔK =-10% | 0.603 | 0.421 | 0.606 | 0.485 | 0.603 | 0.421 | 0.654 | 0.534 | 0.652 | 0.579 | 0.654 | 0.534 | |

| ΔK = +10% | 0.729 | 0.558 | 0.733 | 0.607 | 0.729 | 0.558 | 0.972 | 0.688 | 0.992 | 0.727 | 0.972 | 0.702 | |

| ΔK =-10% | 0.609 | 0.428 | 0.611 | 0.491 | 0.609 | 0.428 | 0.661 | 0.542 | 0.659 | 0.586 | 0.661 | 0.542 | |

| ΔK = +10% | 0.767 | 0.654 | 0.771 | 0.694 | 0.767 | 0.654 | 1.093 | 0.791 | 1.113 | 0.849 | 1.093 | 0.837 | |

| ΔK =-10% | 0.468 | 0.474 | 0.472 | 0.533 | 0.468 | 0.474 | 0.743 | 0.533 | 0.739 | 0.590 | 0.743 | 0.533 | |

| ΔK = +10% | 0.761 | 0.636 | 0.765 | 0.678 | 0.761 | 0.636 | 1.084 | 0.775 | 1.105 | 0.833 | 1.084 | 0.834 | |

| ΔK =-10% | 0.643 | 0.472 | 0.645 | 0.530 | 0.643 | 0.472 | 0.756 | 0.550 | 0.752 | 0.605 | 0.756 | 0.550 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).