Submitted:

15 May 2025

Posted:

16 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

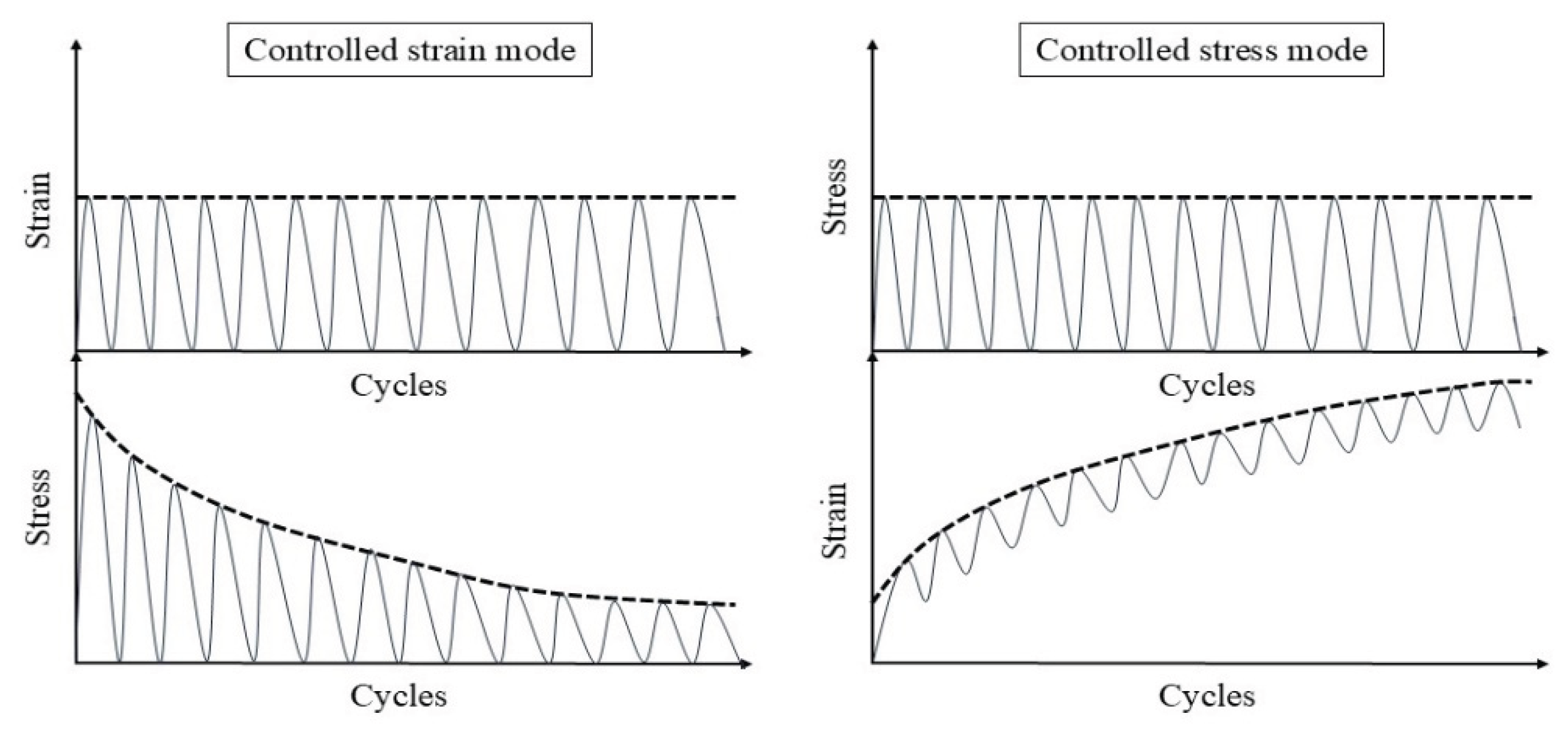

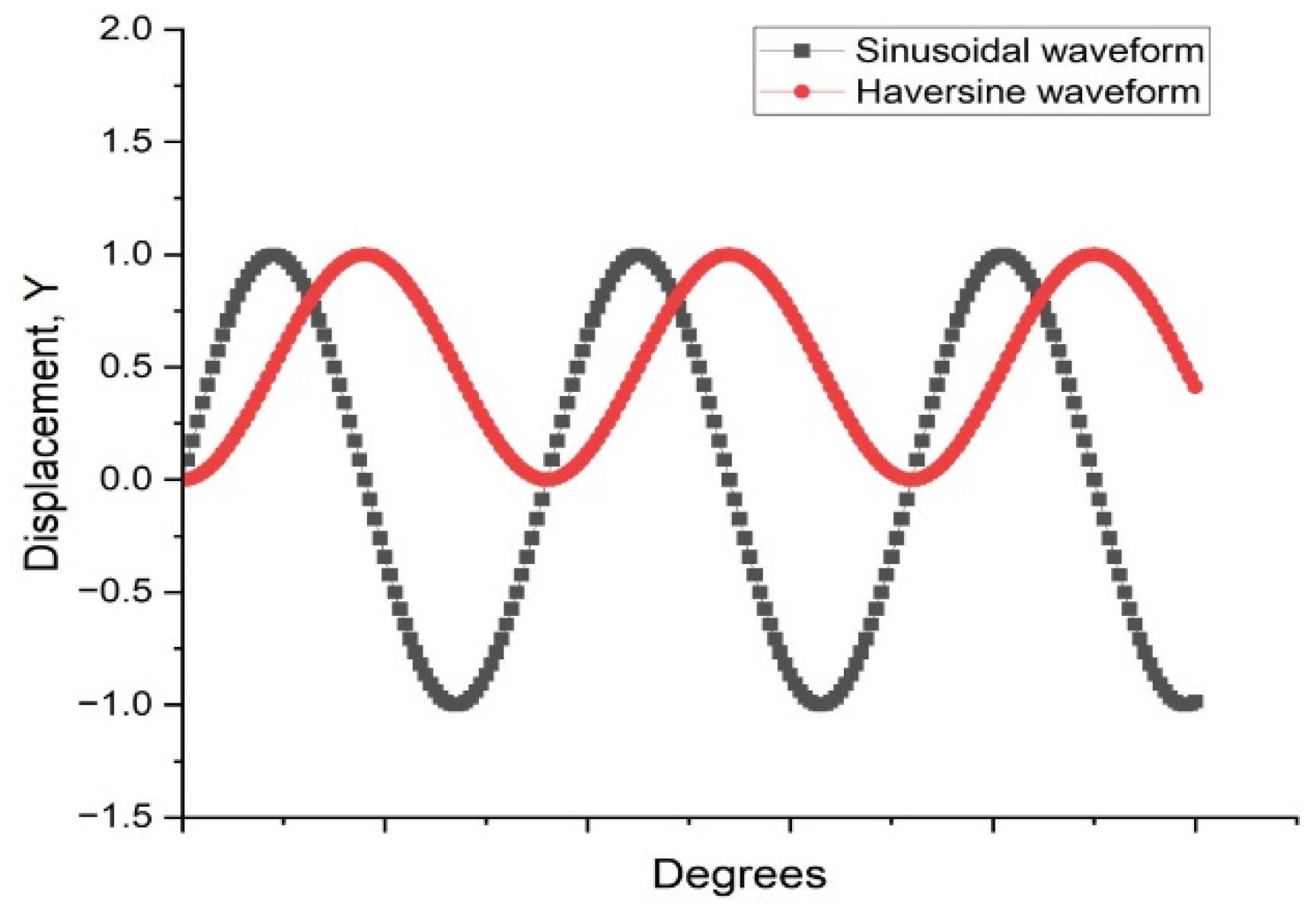

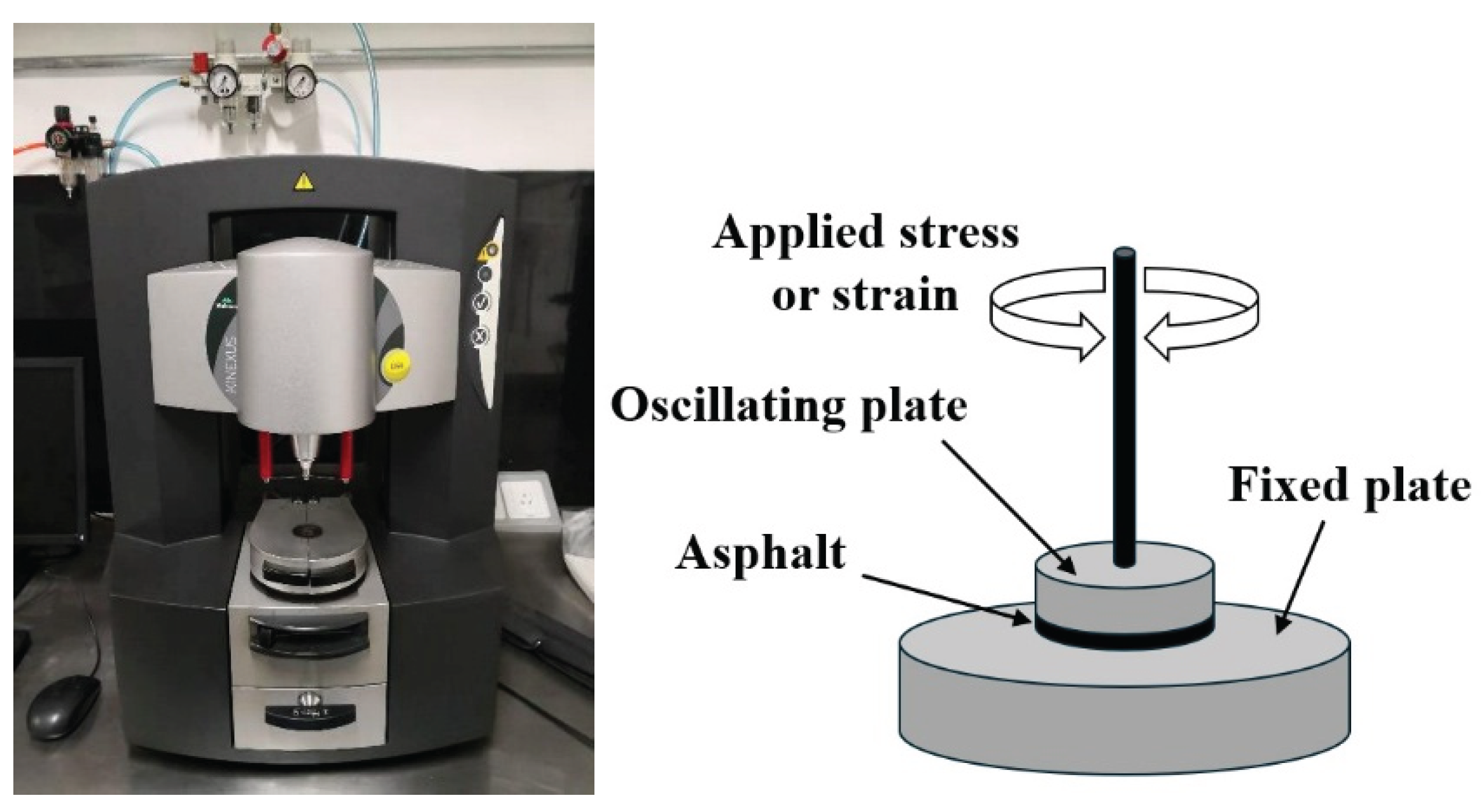

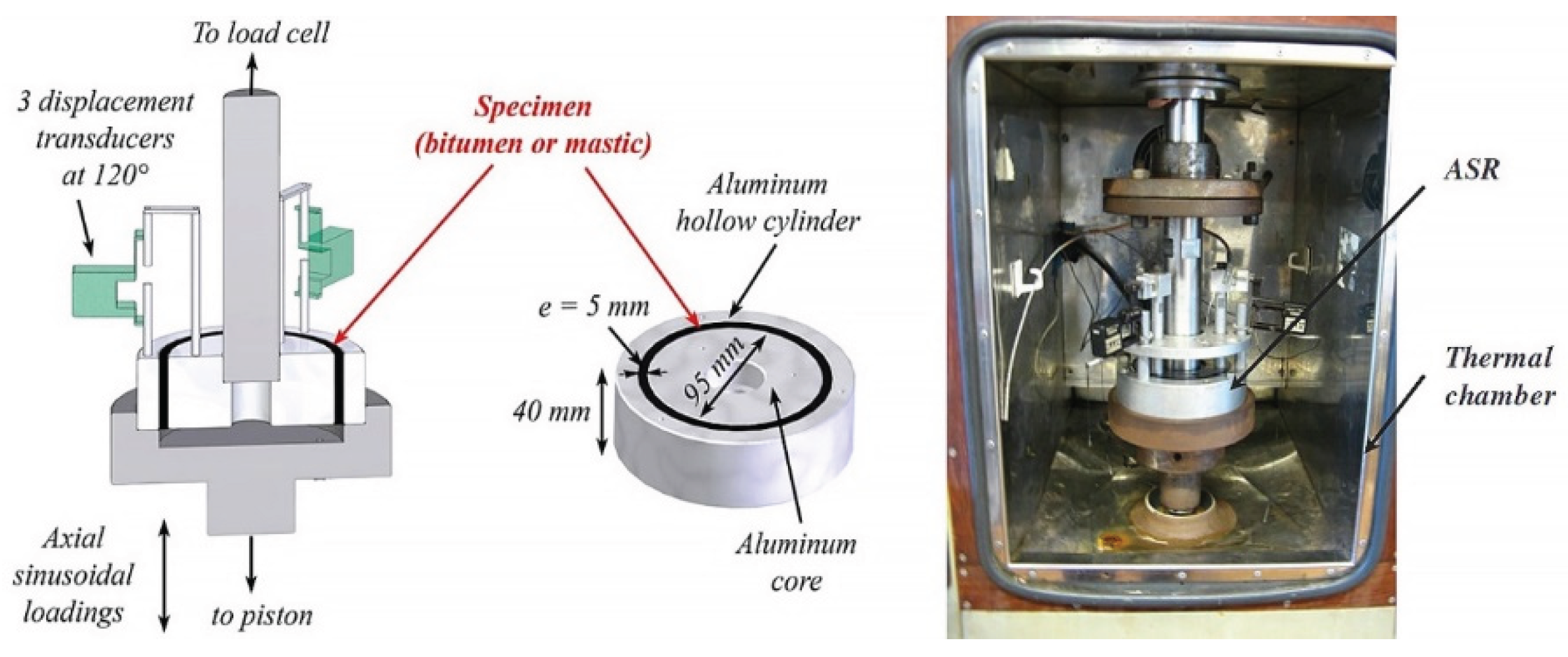

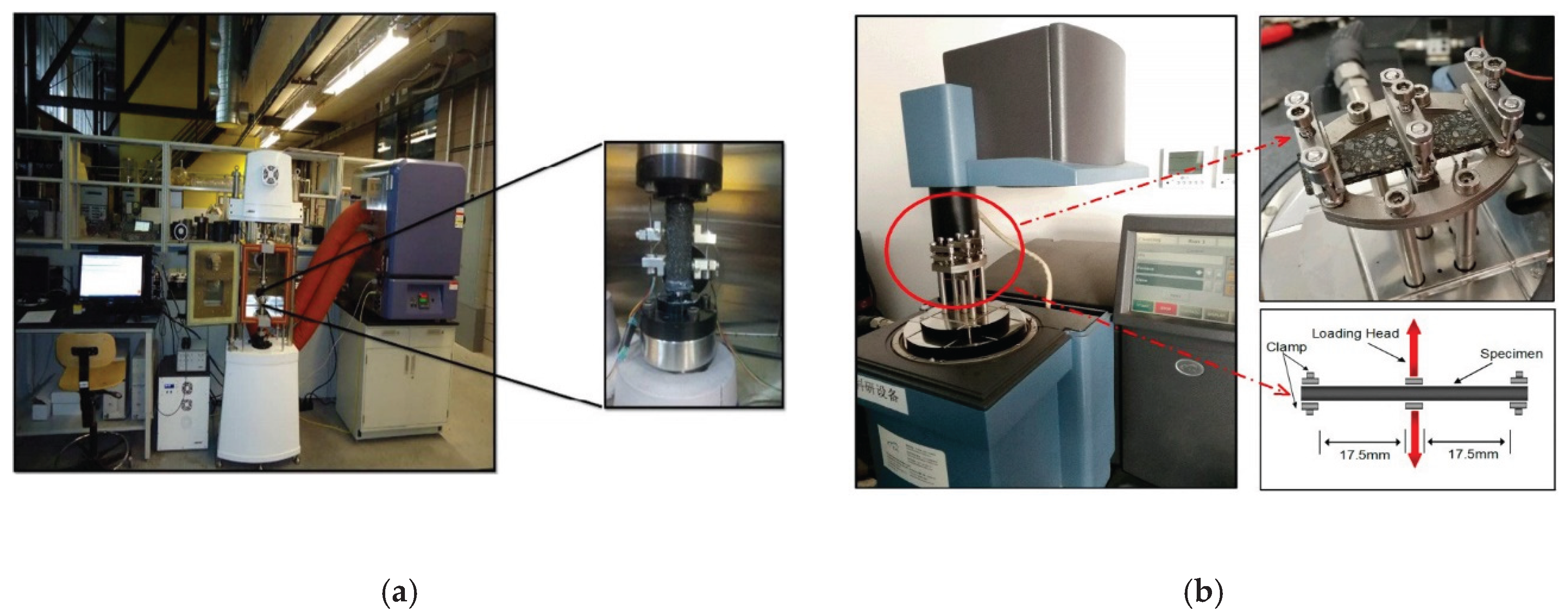

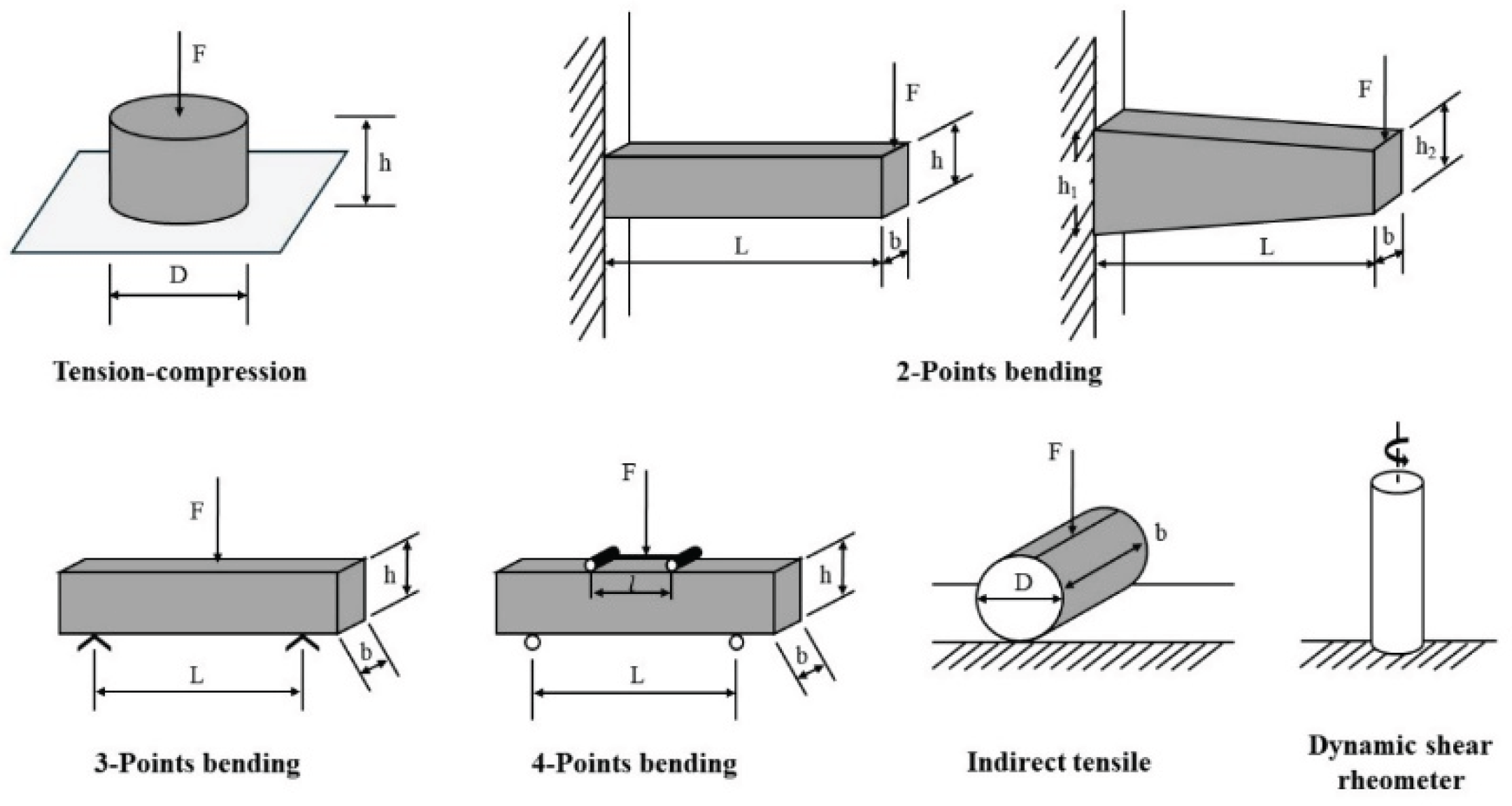

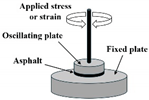

2. Fatigue Test Methods

3. Failure Criteria for Fatigue Approaches

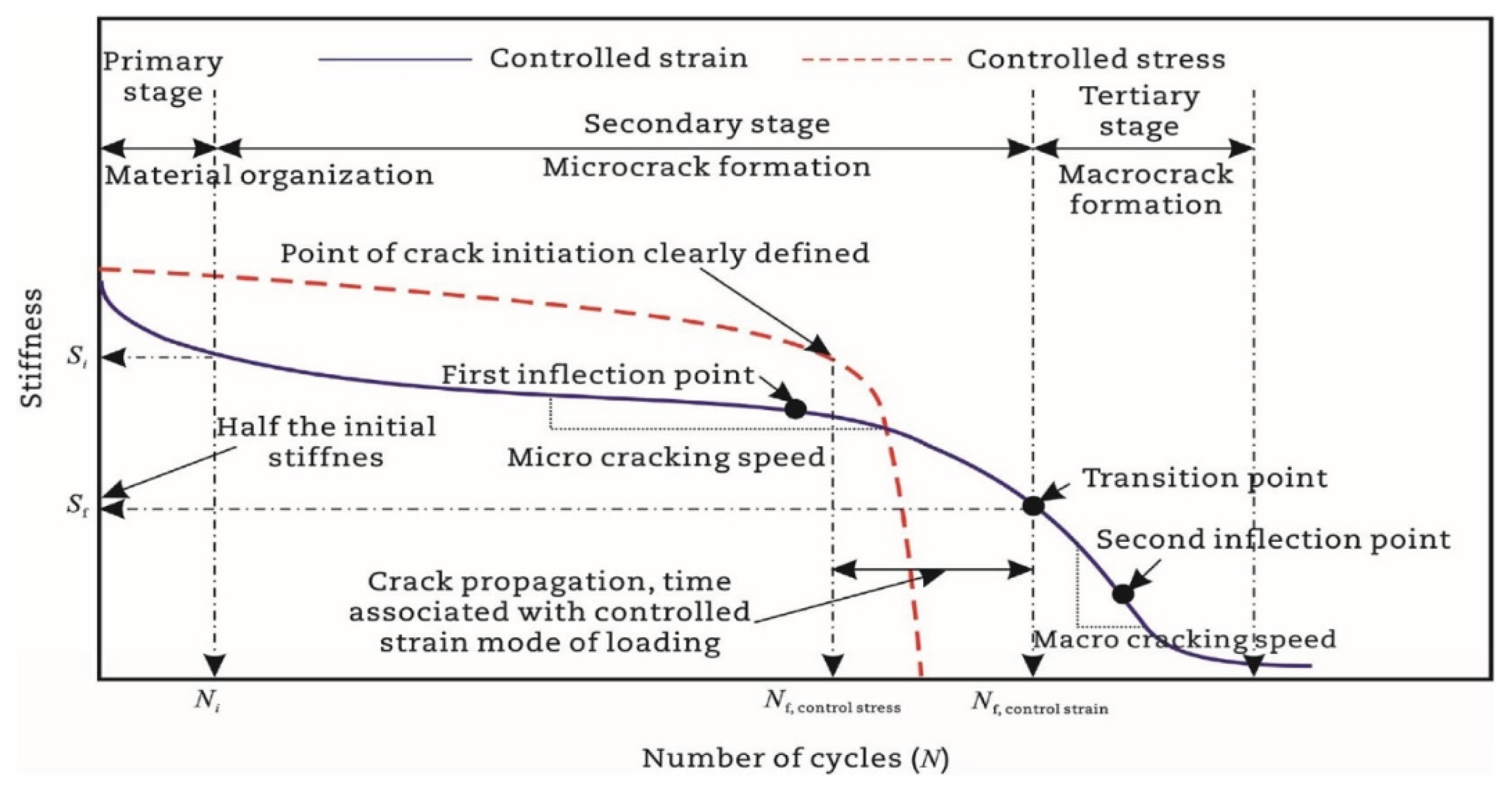

3.1. Phenomenological Approaches

3.1.1. Failure Criteria of Basic Fatigue Models

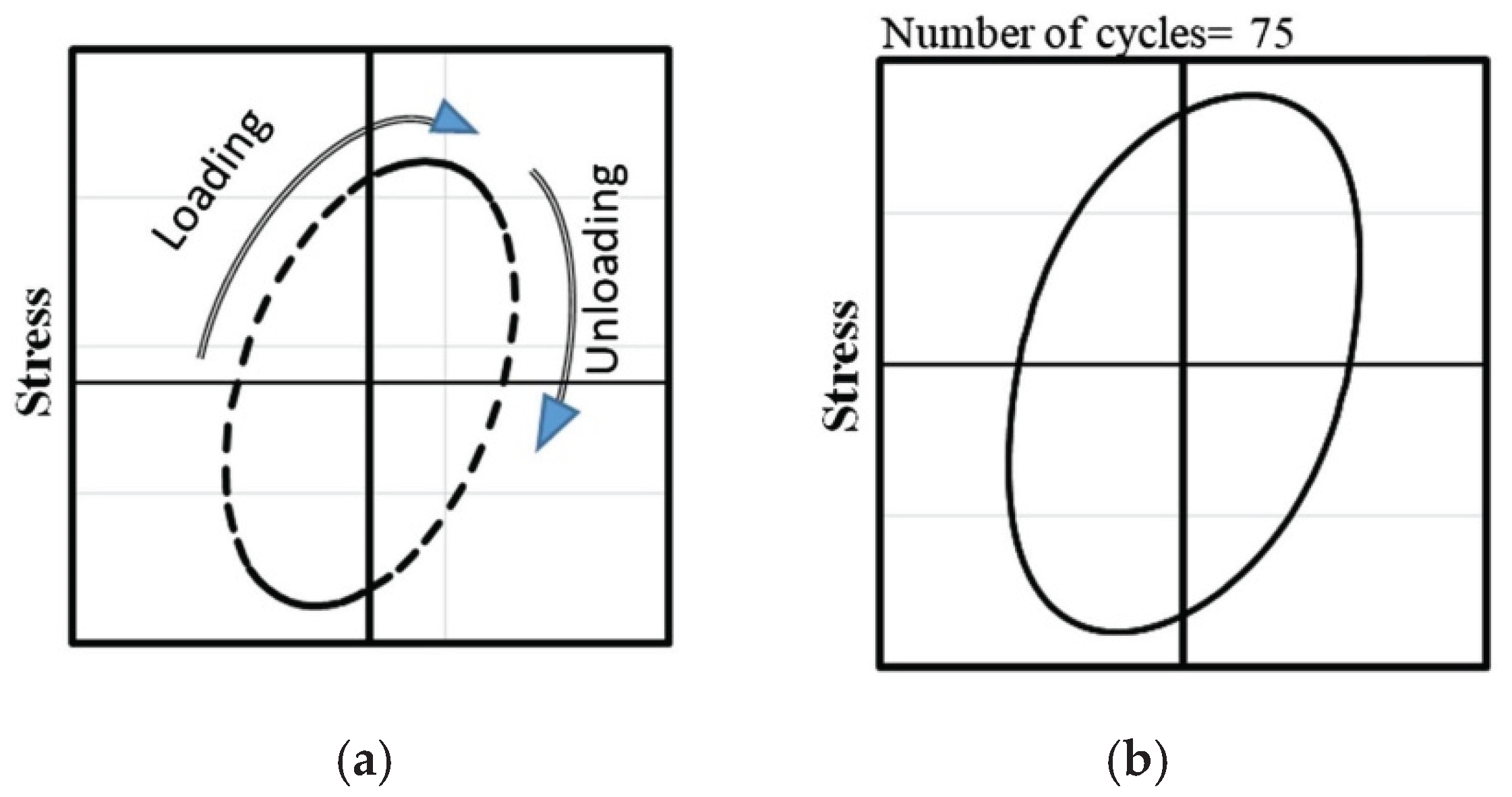

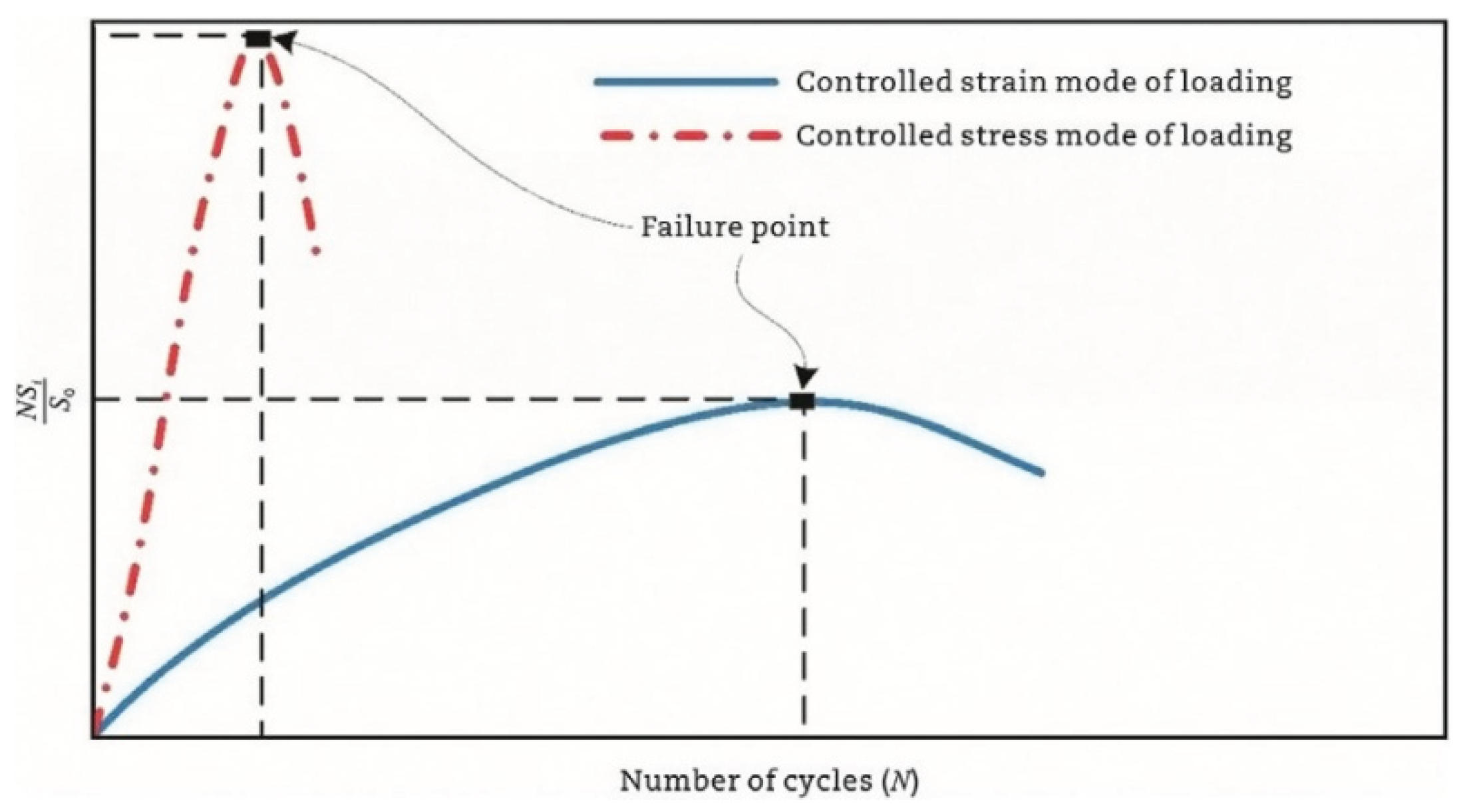

- Phase I (or adaptation phase): the stiffness decreases rapidly in the primary stage. The two biasing phenomena, including heating caused by energy dissipation and binder thixotropy, can be interpreted for the sudden loss in stiffness [52]. When the test is paused at this stage, this loss of stiffness can be easily recovered.

- Phase II (or quasi-stationary phase): this secondary stage is characterized by a quasi-linear decrease of stiffness. In this phase, the fatigue phenomenon can be characterized by the initiation of microcracks.

- Phase III (or failure phase): at a certain degree of damage, the macrocracks generated by the coalescence of microcracks inside the material propagate in the tertiary stage. The fatigue test cannot be considered as homogenous anymore.

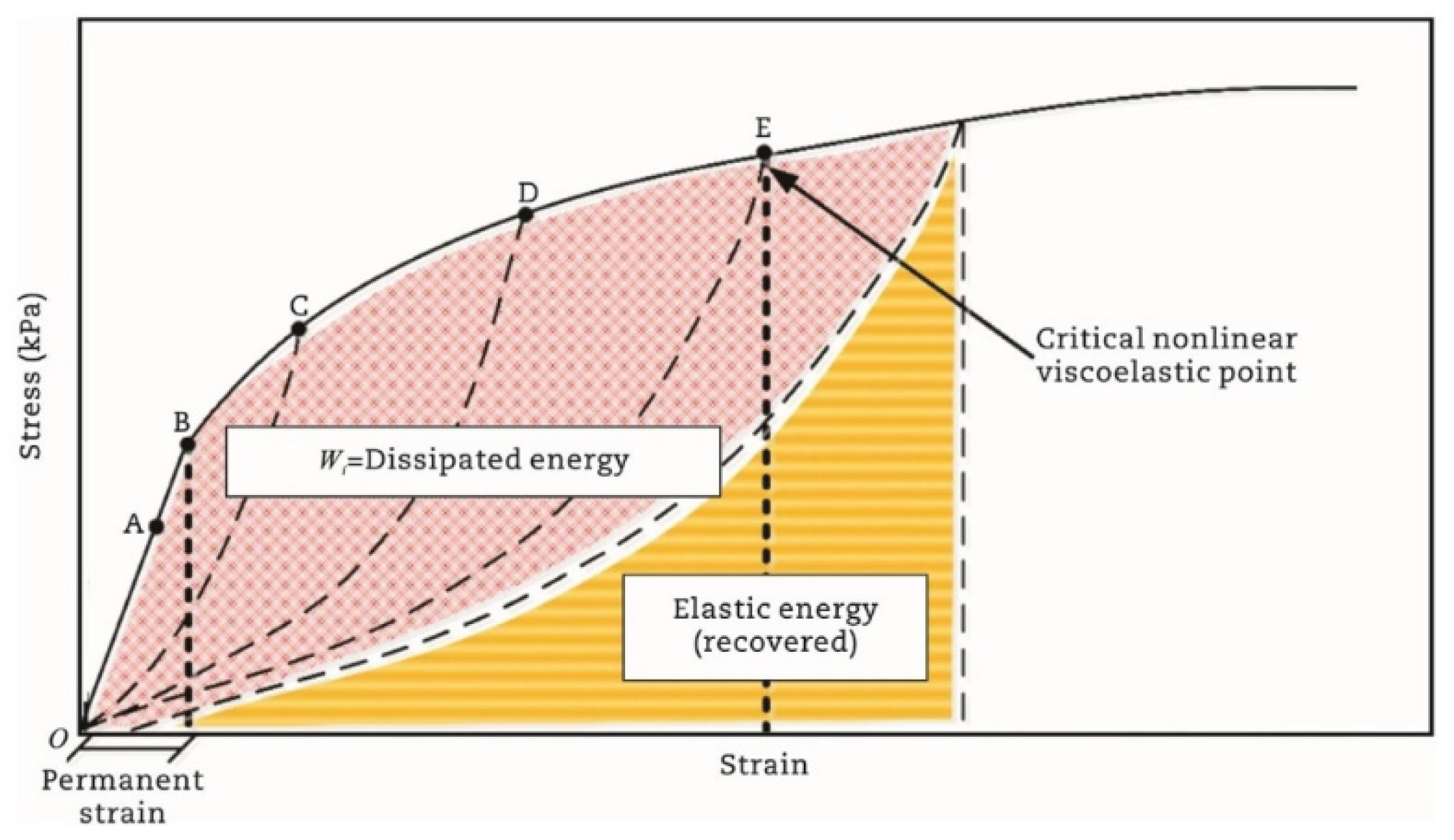

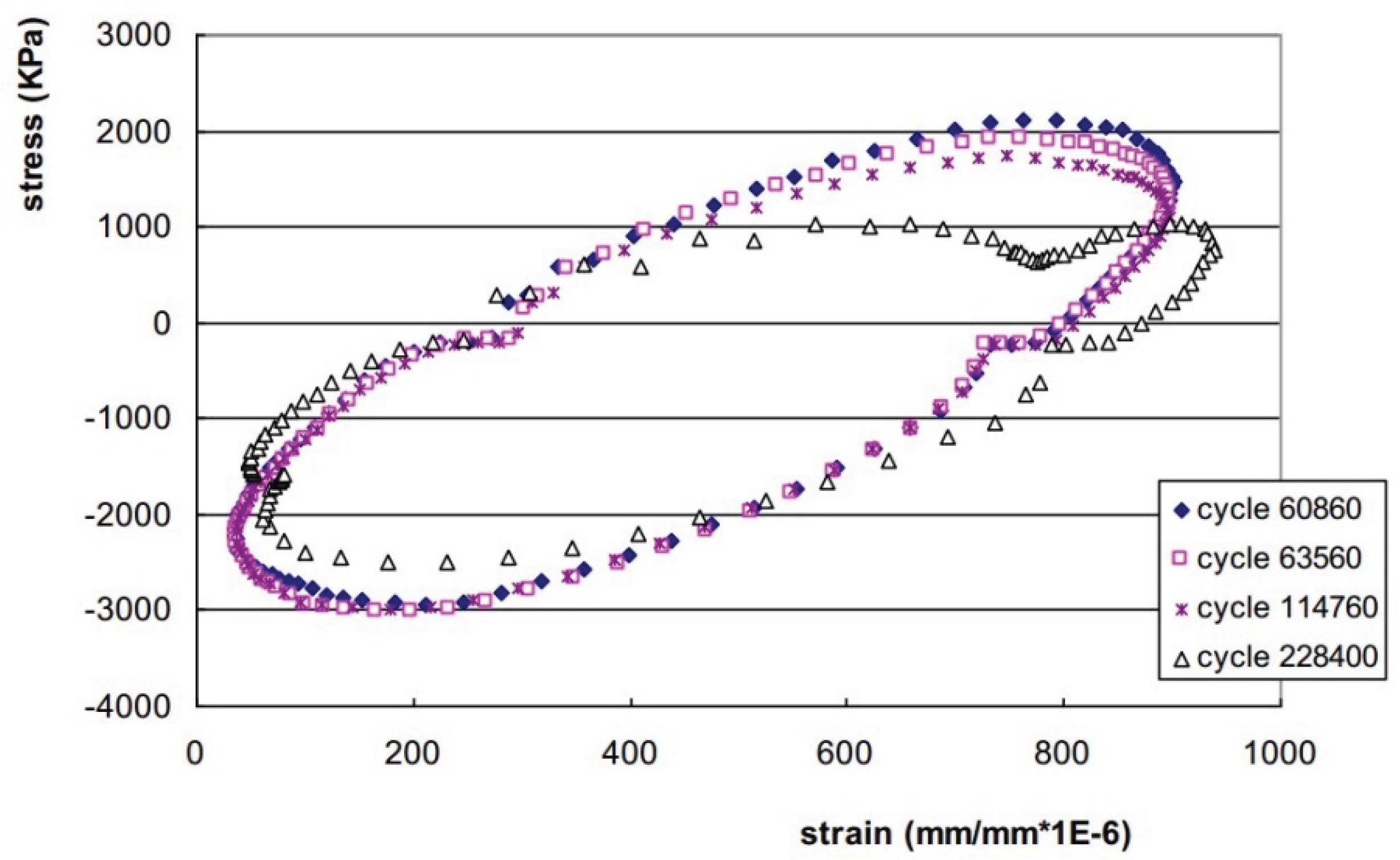

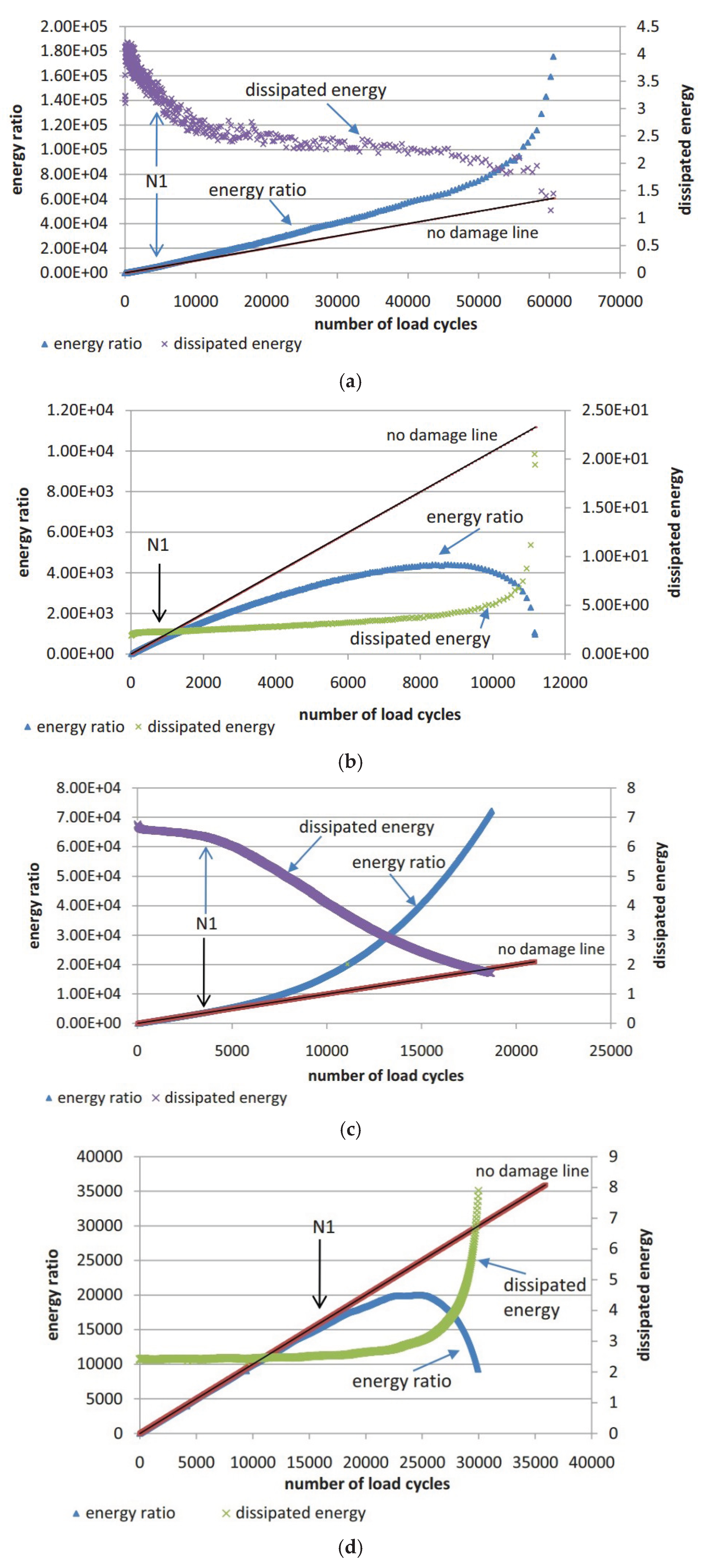

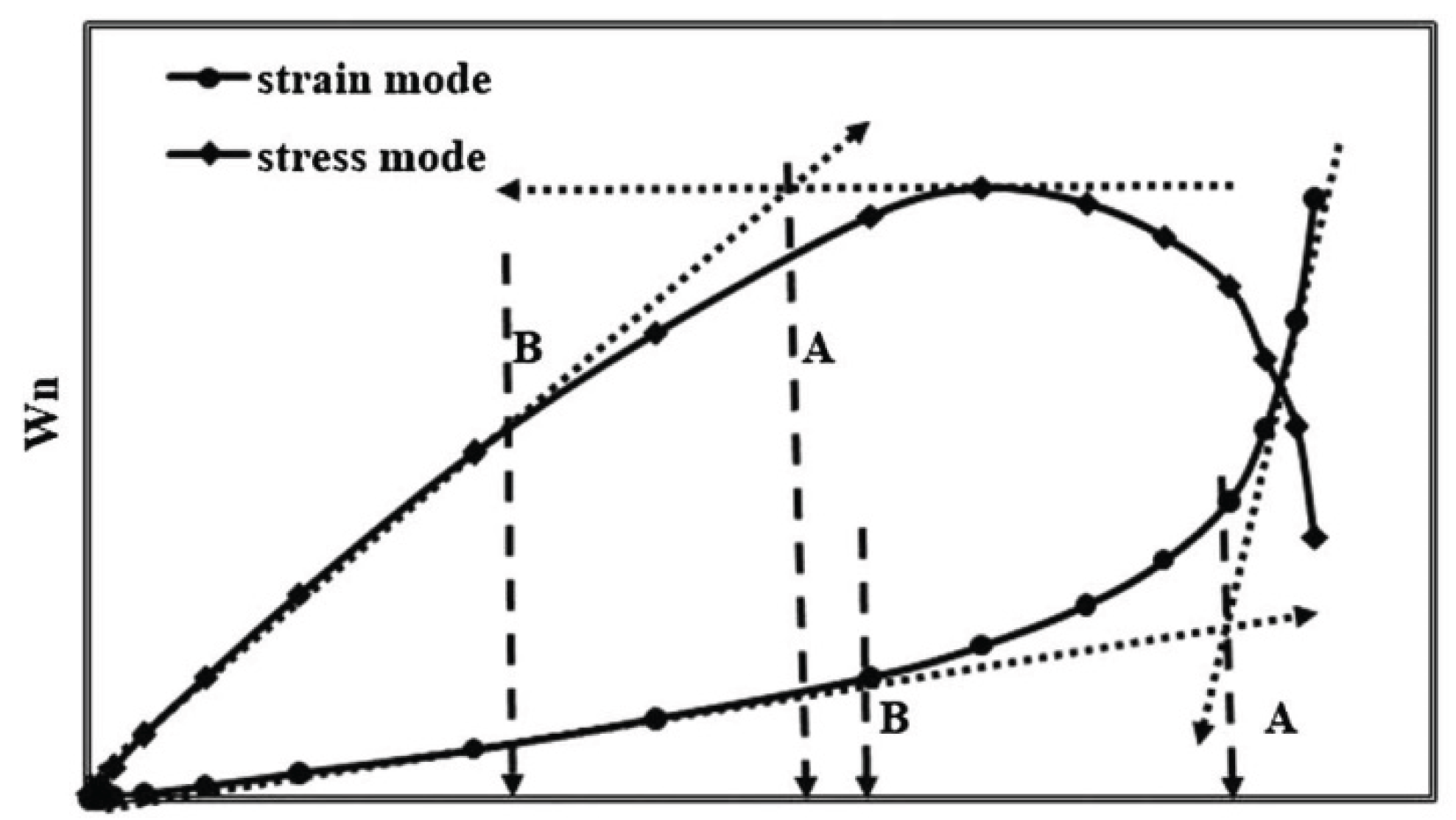

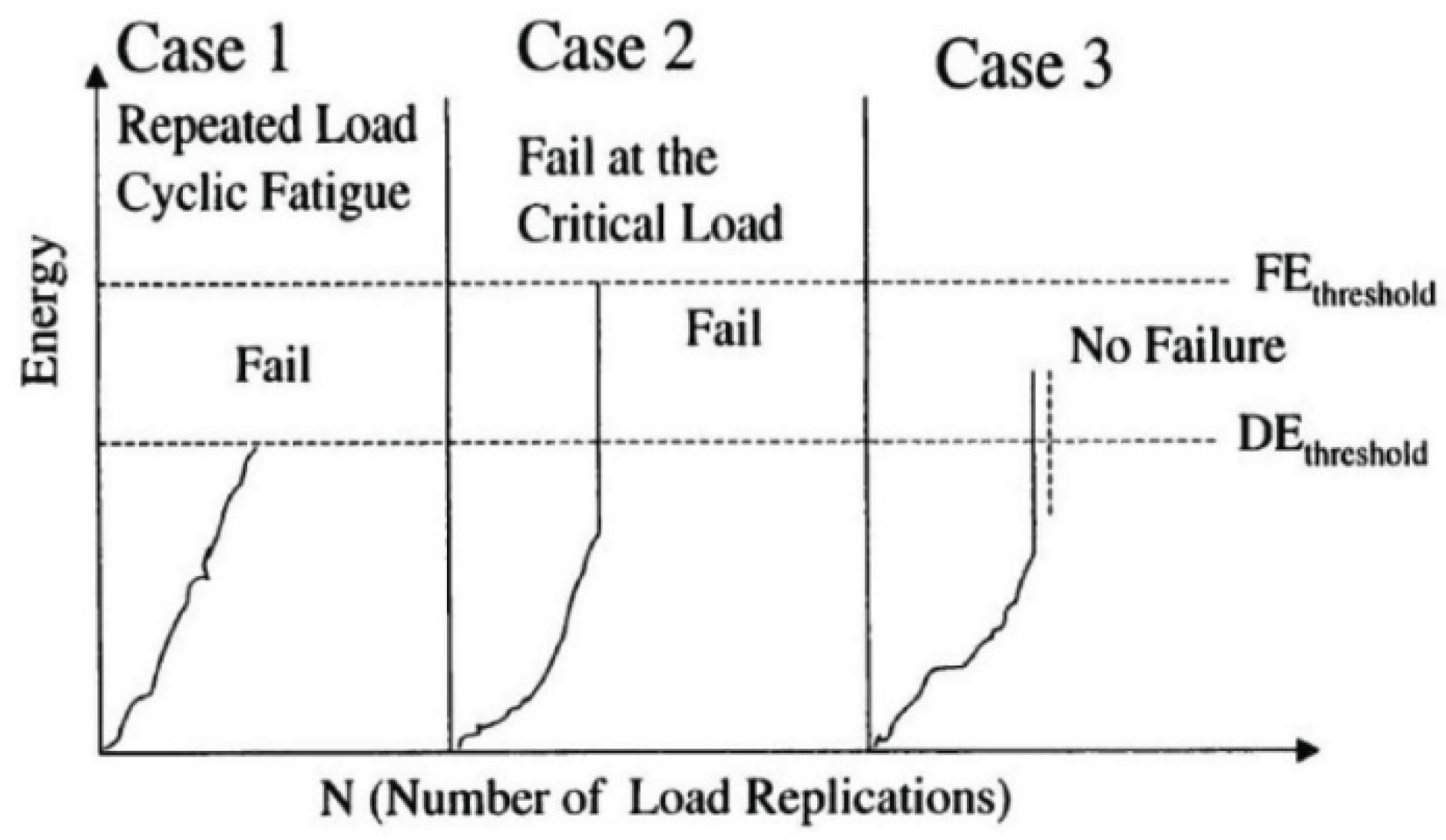

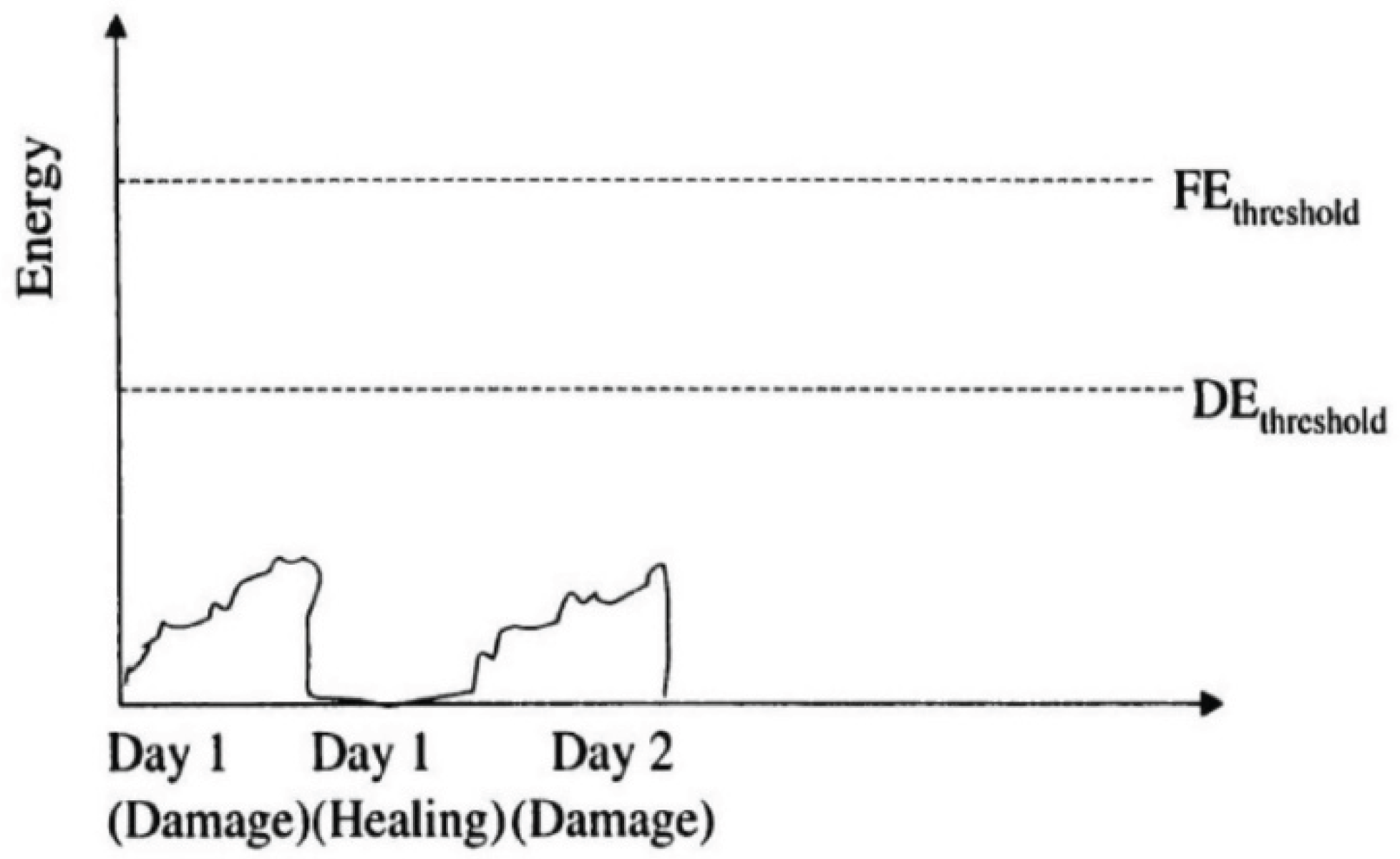

3.1.2. Failure Criteria of Energy-Based Models

3.2. Mechanistic Approaches

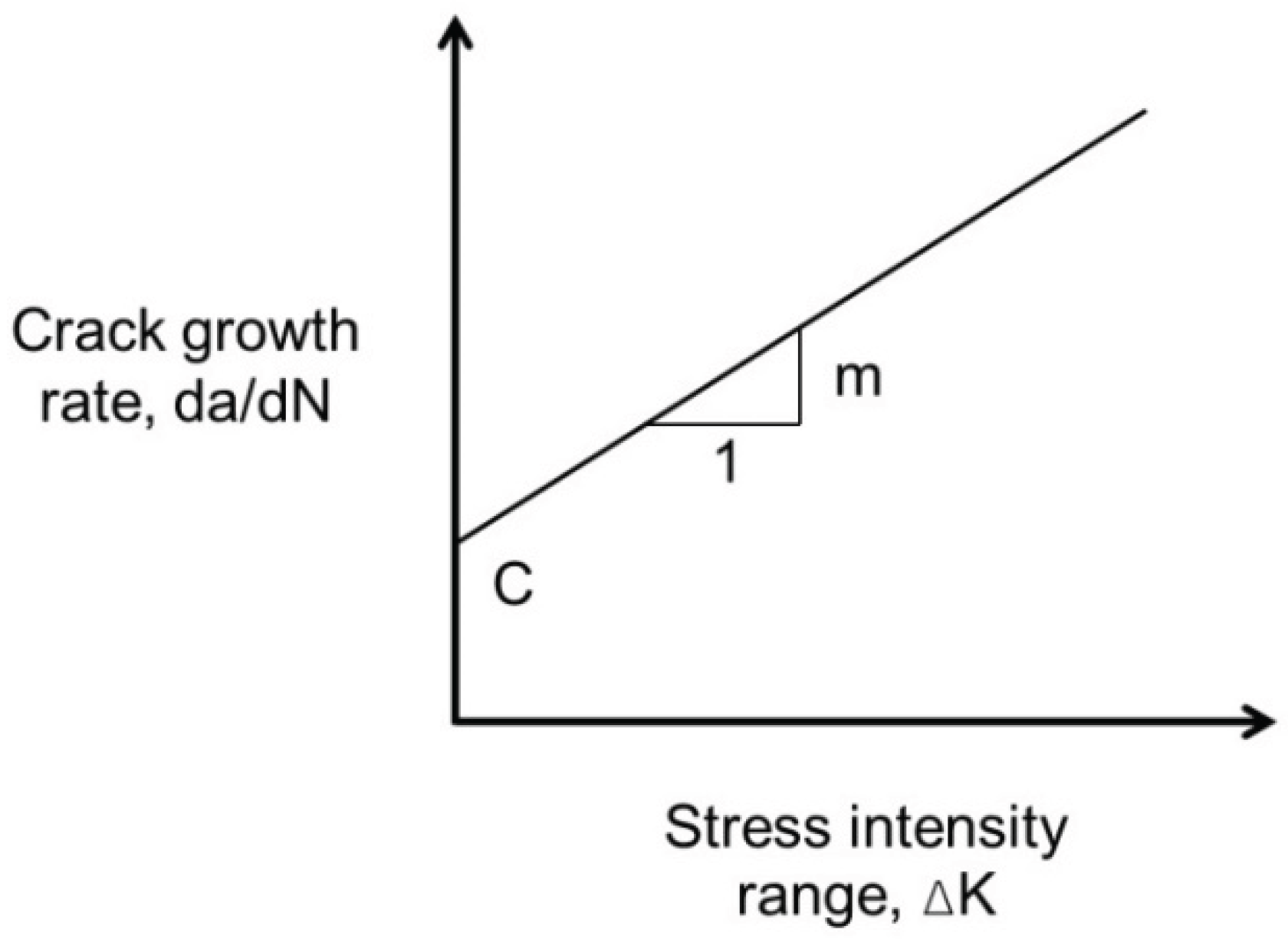

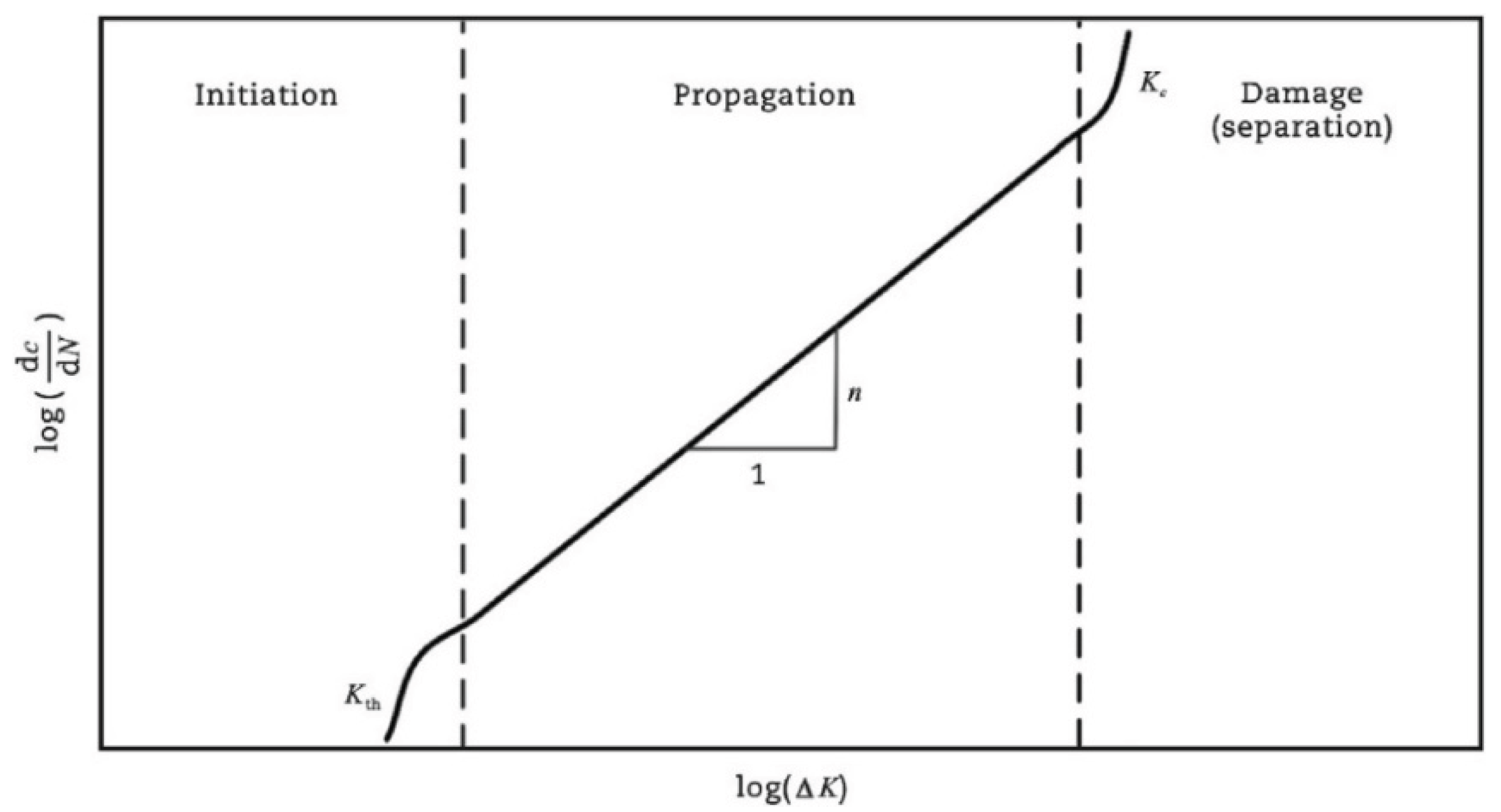

3.2.1. Fracture Mechanics Models

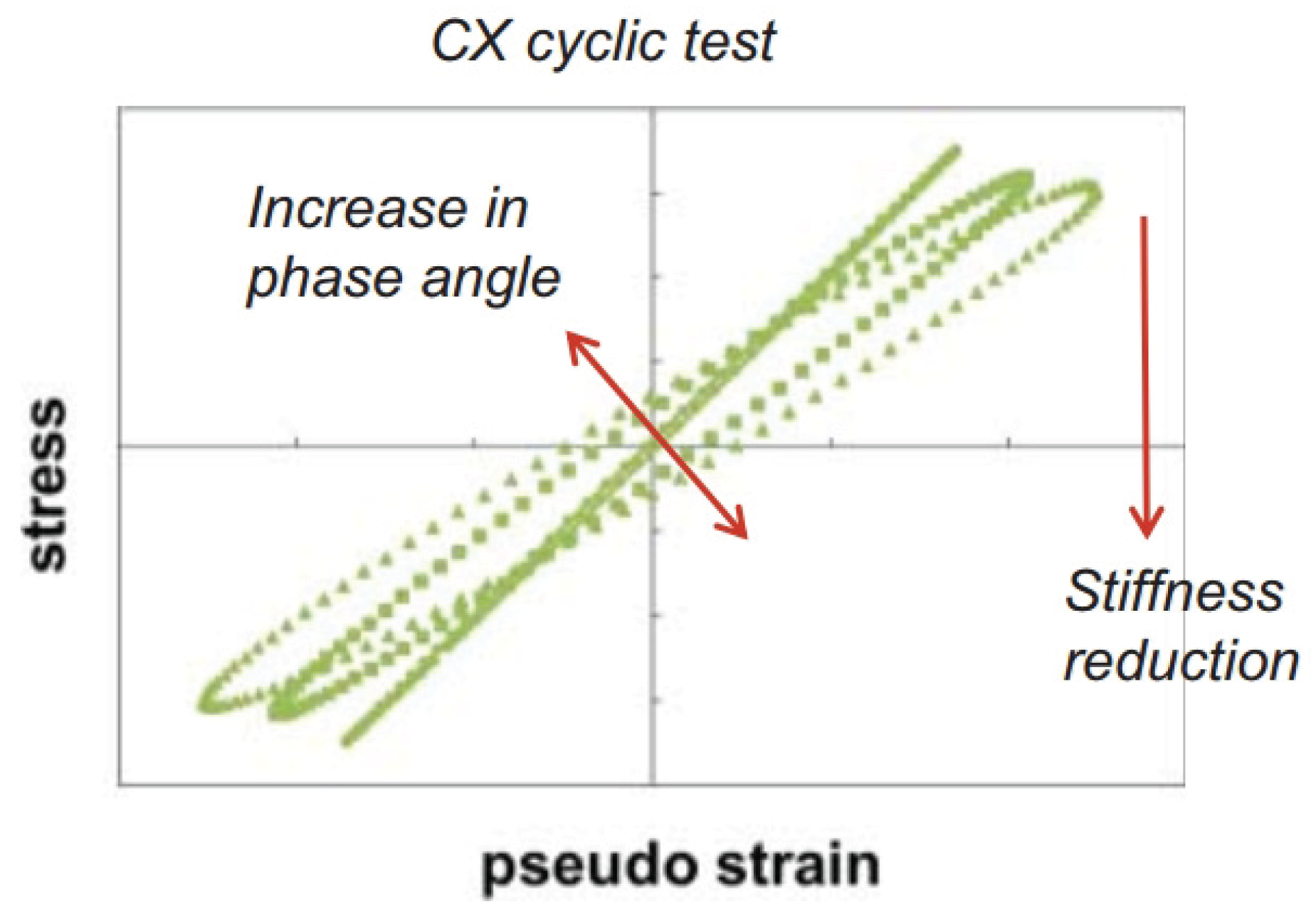

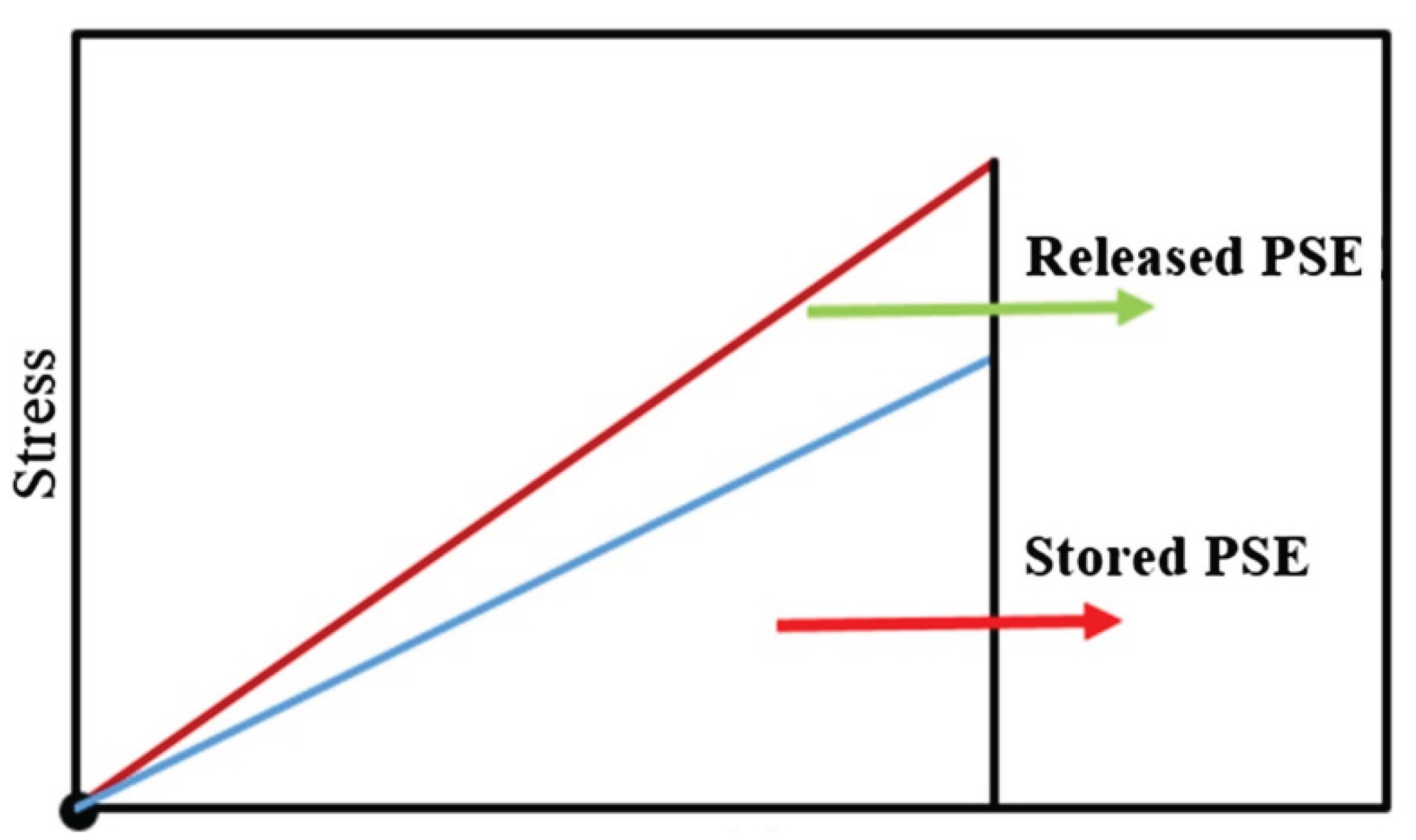

3.2.2. Viscoelastic Continuum Damage (VECD) Model

3.3. Artificial Neural Network Approaches

4. Discussion and Conclusions

- The academic community currently lacks a consensus regarding the standardized definition of fatigue failure criteria for asphalt binders and mixtures. These criteria are employed to establish a critical failure point, corresponding to a specific number of loading cycles (), that represents an equivalent damage state at the conclusion of fatigue testing. An effective criterion must demonstrate robustness across diverse experimental conditions, including variations in loading modes (e.g., stress- vs. strain-controlled), temperature regimes, applied strain or stress amplitudes, and testing protocols.

- The determination of fatigue failure criteria is intrinsically contingent upon the specific analytical framework employed (e.g., dissipated energy theory, continuum damage mechanics). Consequently, the selection of an appropriate criterion necessitates rigorous methodological justification, as no universal criterion possesses sufficient generalizability to encompass all modeling paradigms.

- Phenomenological models demonstrate statistically comparable fatigue life predictions ( values) under identical experimental conditions. The widespread adoption of the stress degradation ratio criterion in such frameworks stems from its operational merits: (1) simplified instrumentation requirements enabling robust measurement, (2) accelerated testing protocols through early failure state identification, and (3) critical compatibility with macrocrack propagation scenarios where fracture planes develop beyond the detection range of axial strain sensors.

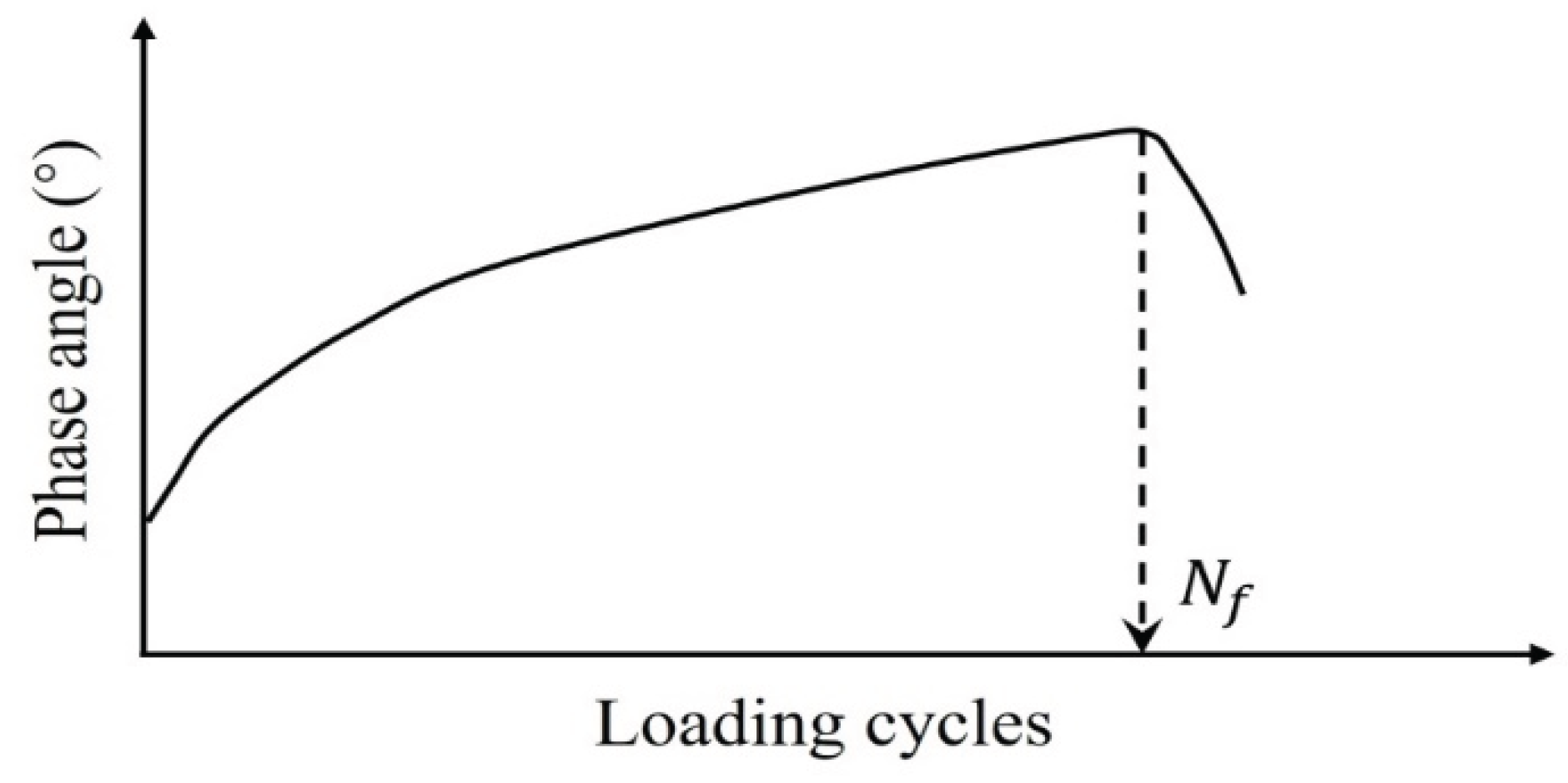

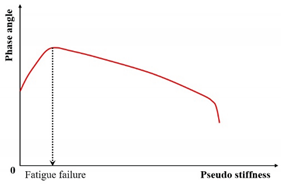

- While the phase angle criterion lacks predictive capacity for fatigue failure progression, it operationally defines failure thresholds through post hoc experimental determination; thus falling under an empirically derived classification. Conversely, failure criteria developed within Viscoelastic Continuum Damage (VECD) modeling frameworks constitute theoretically derived classifications, as they emerge from mechanistic analyses of damage accumulation processes.

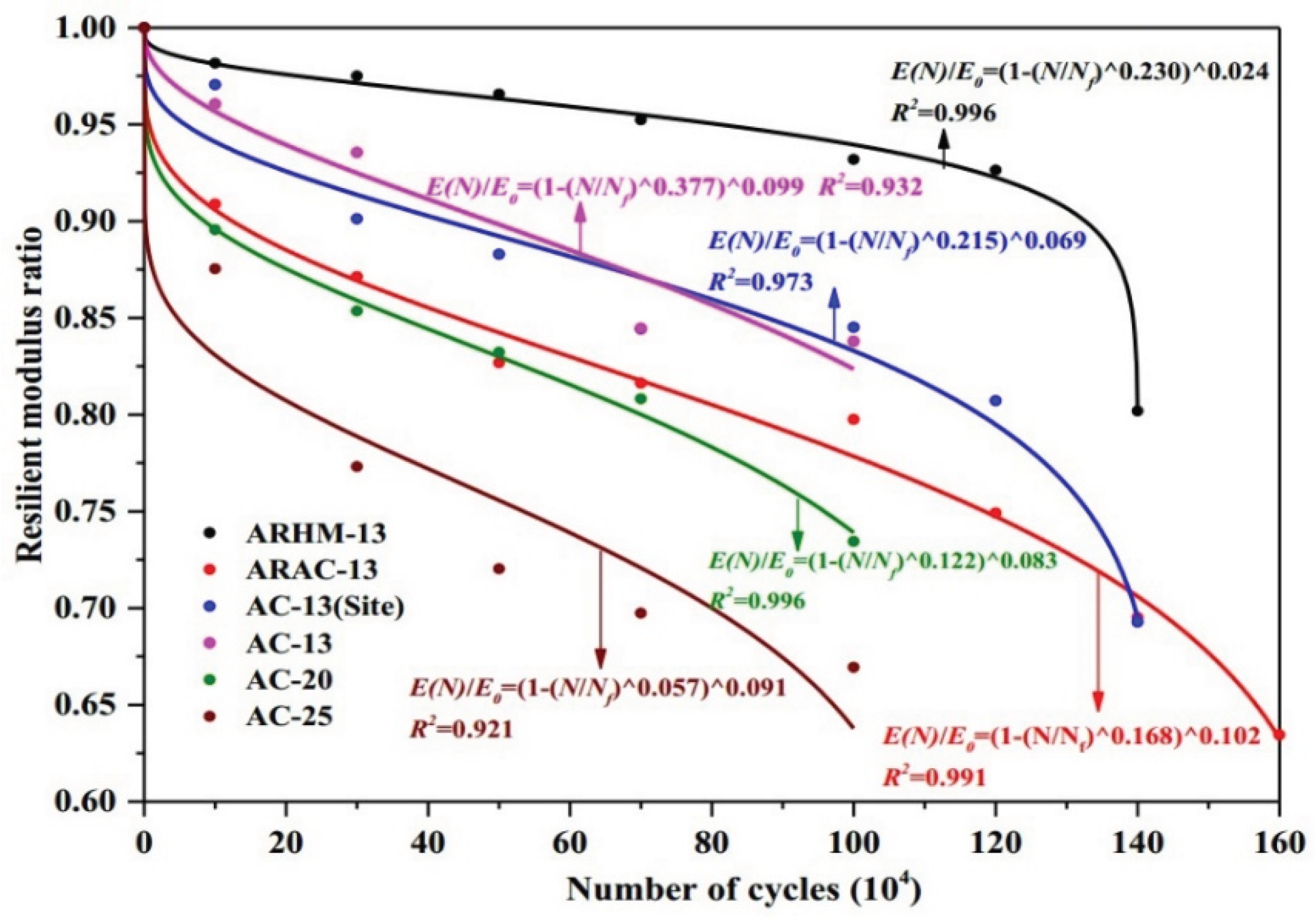

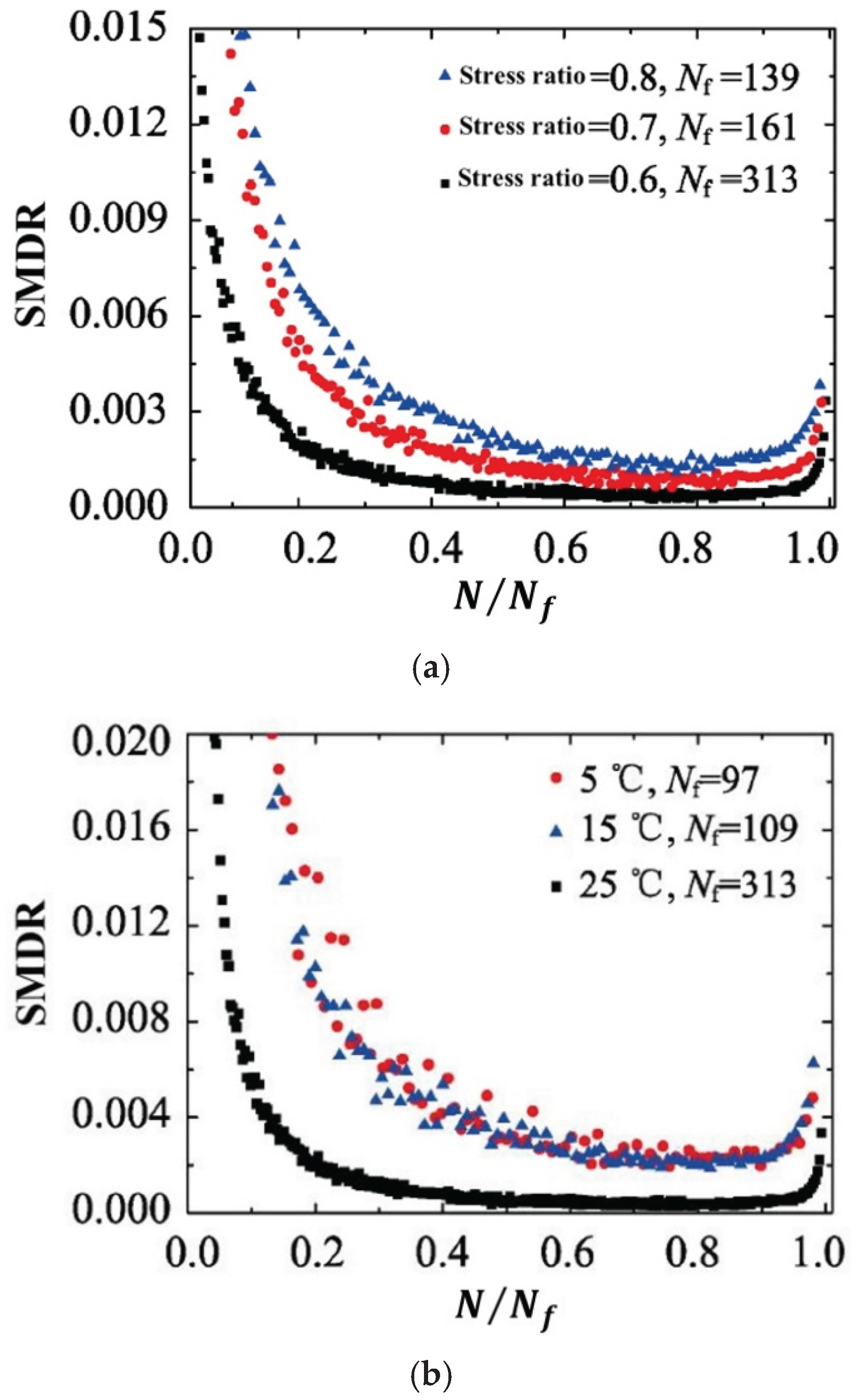

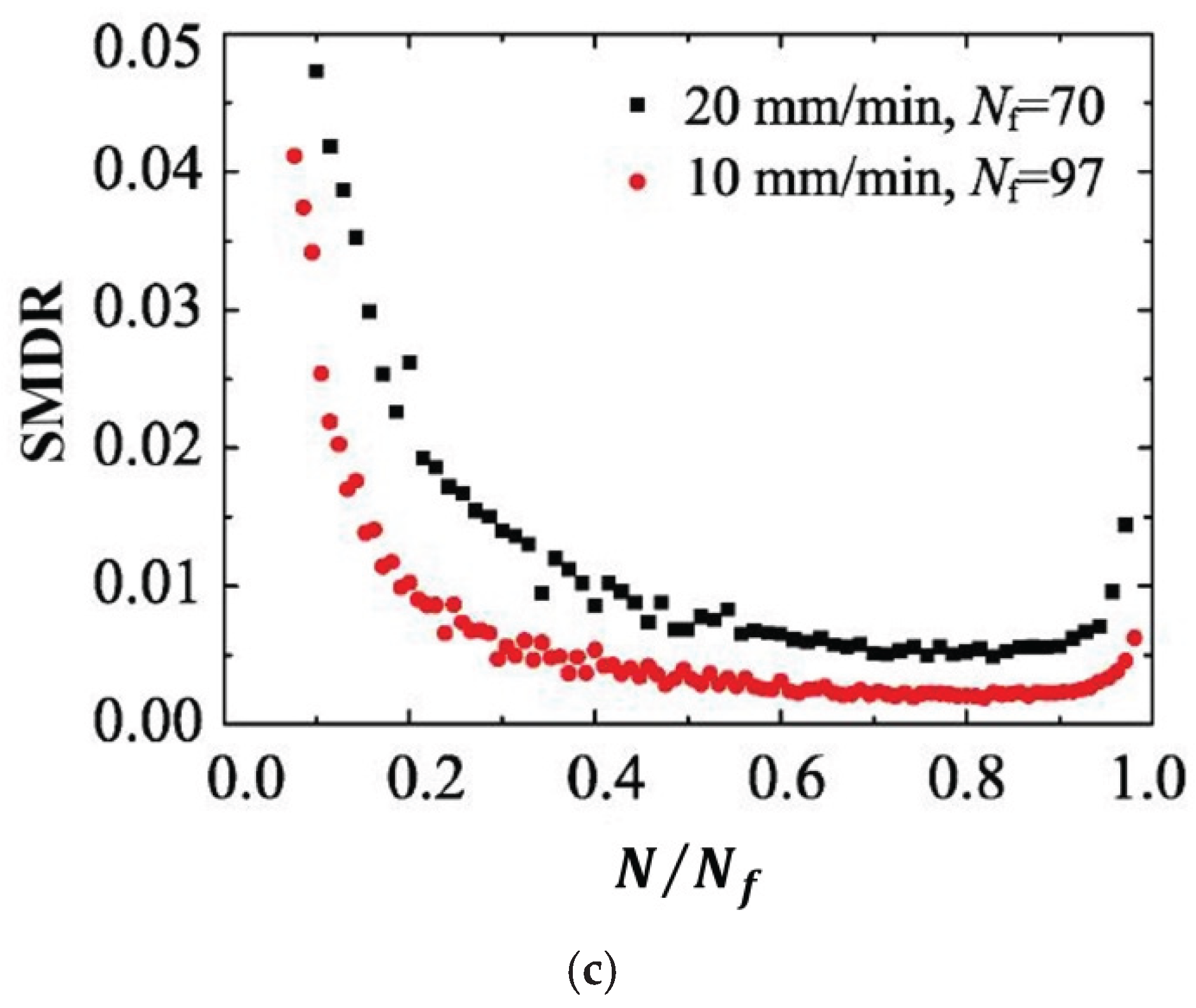

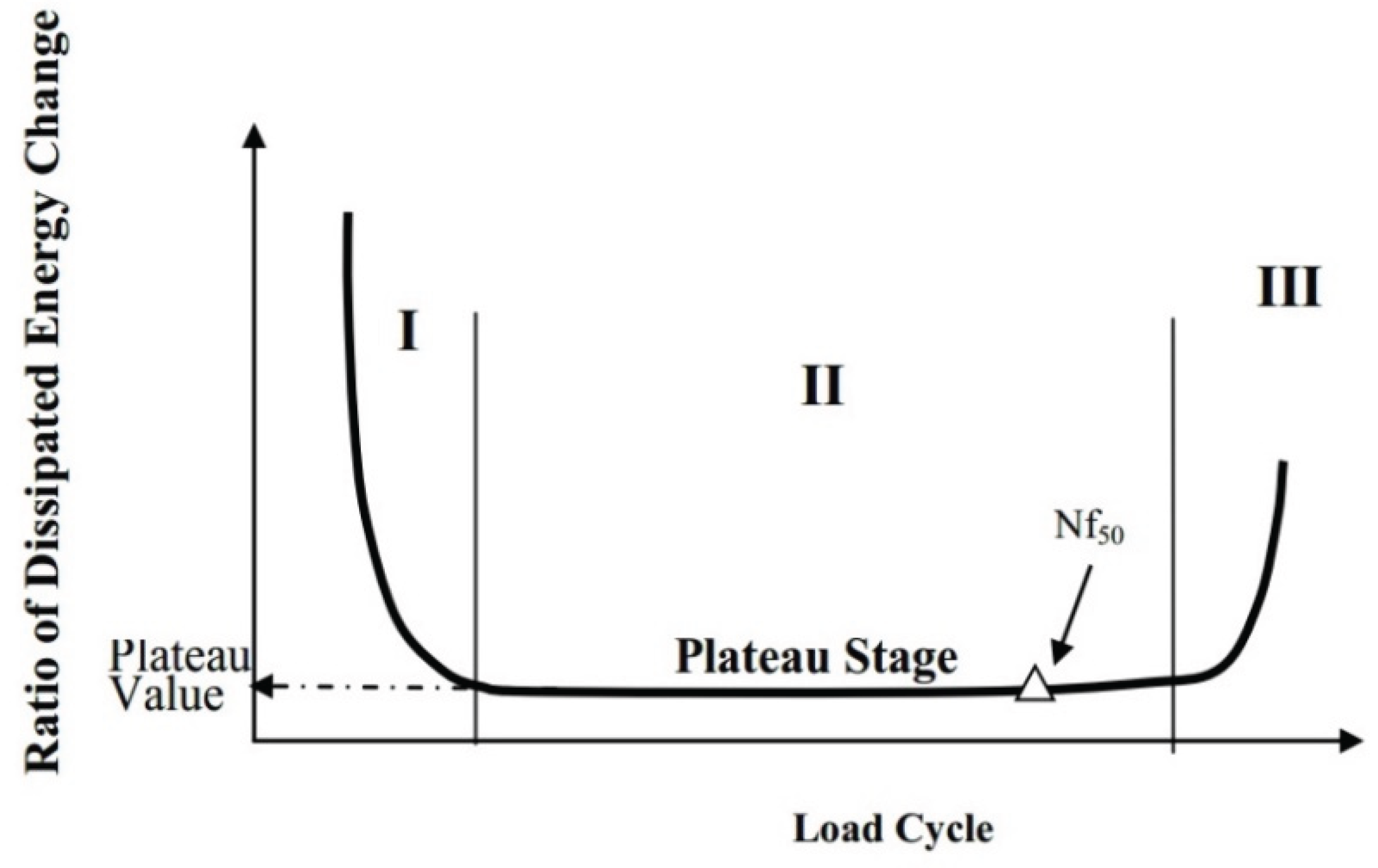

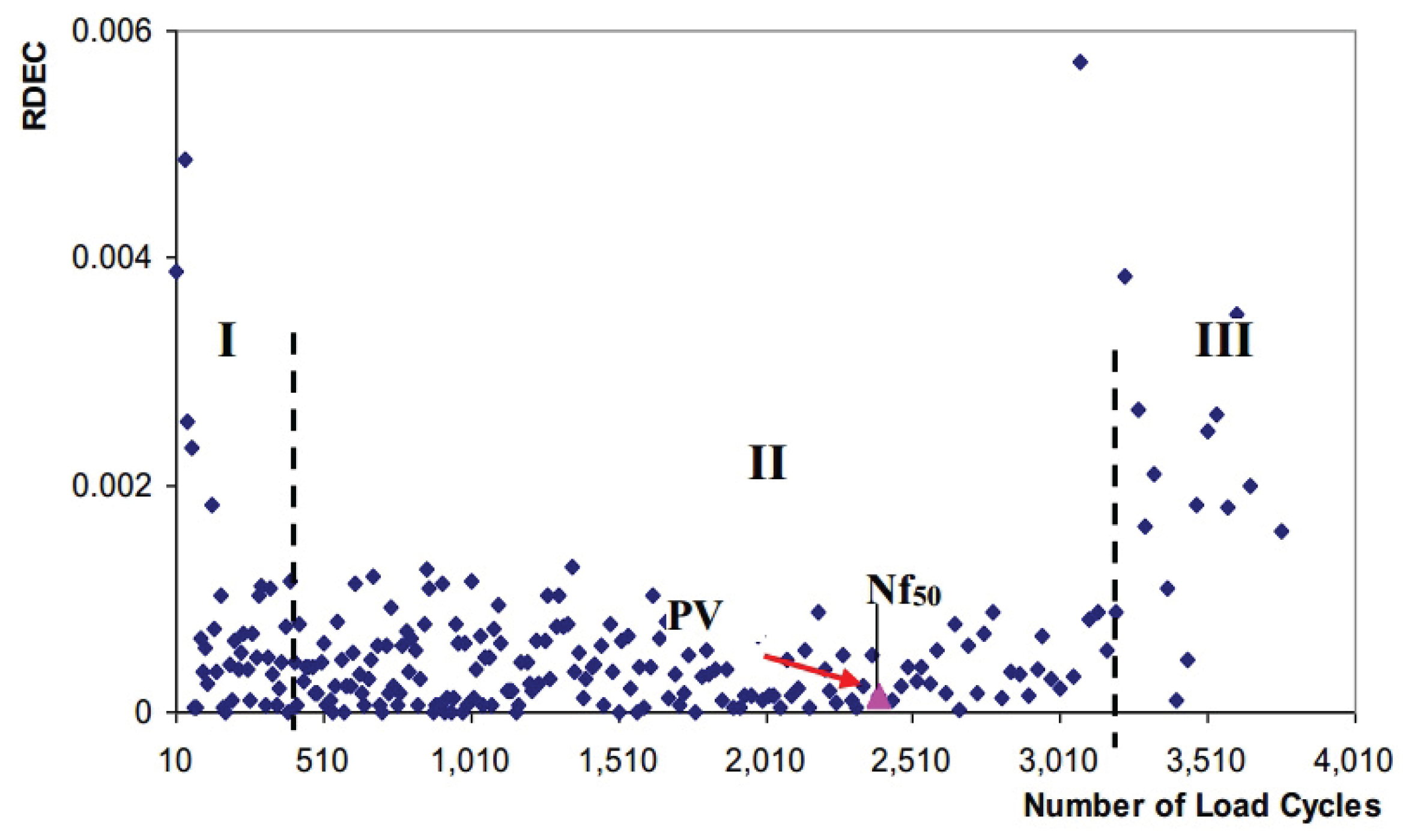

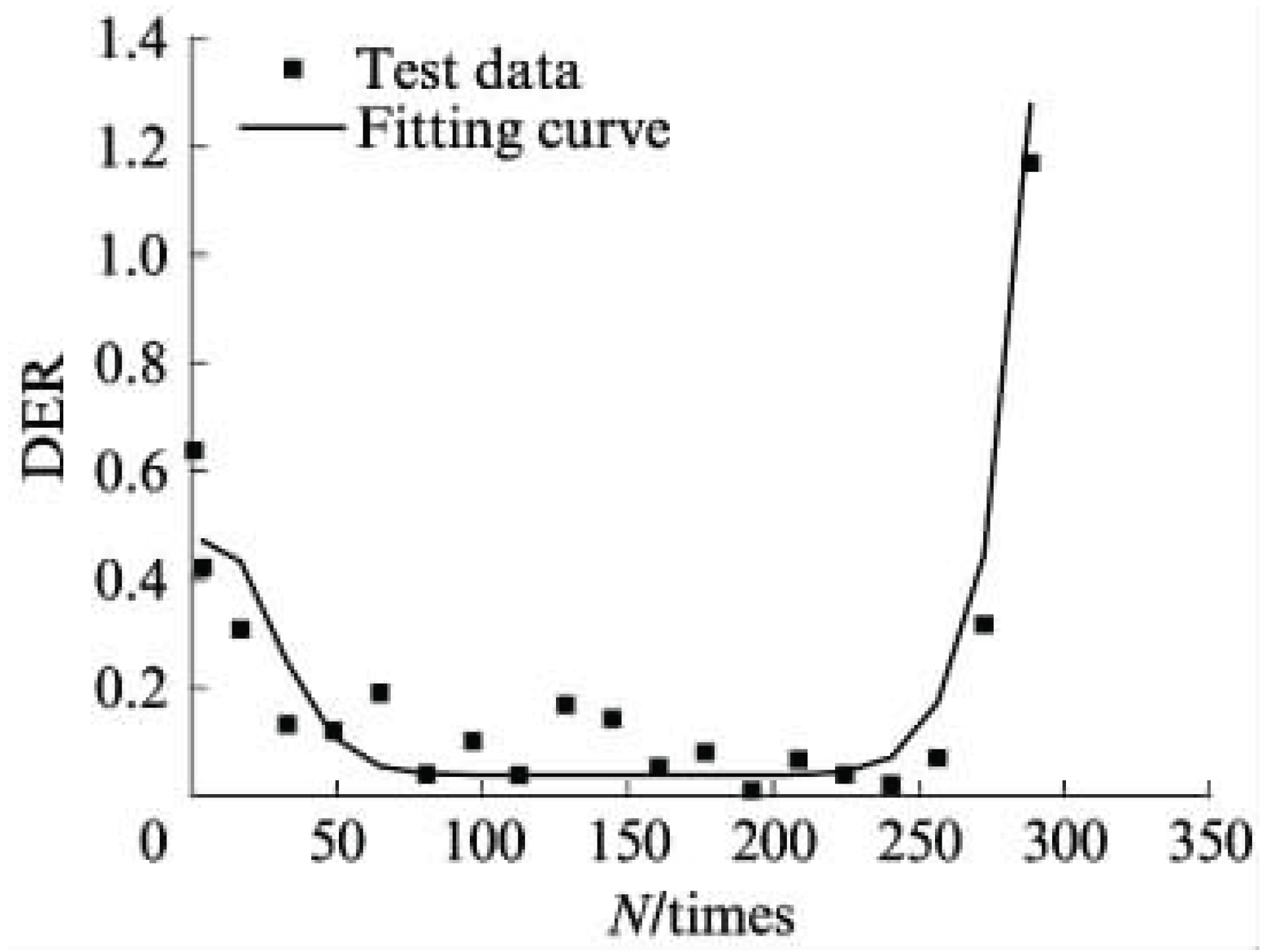

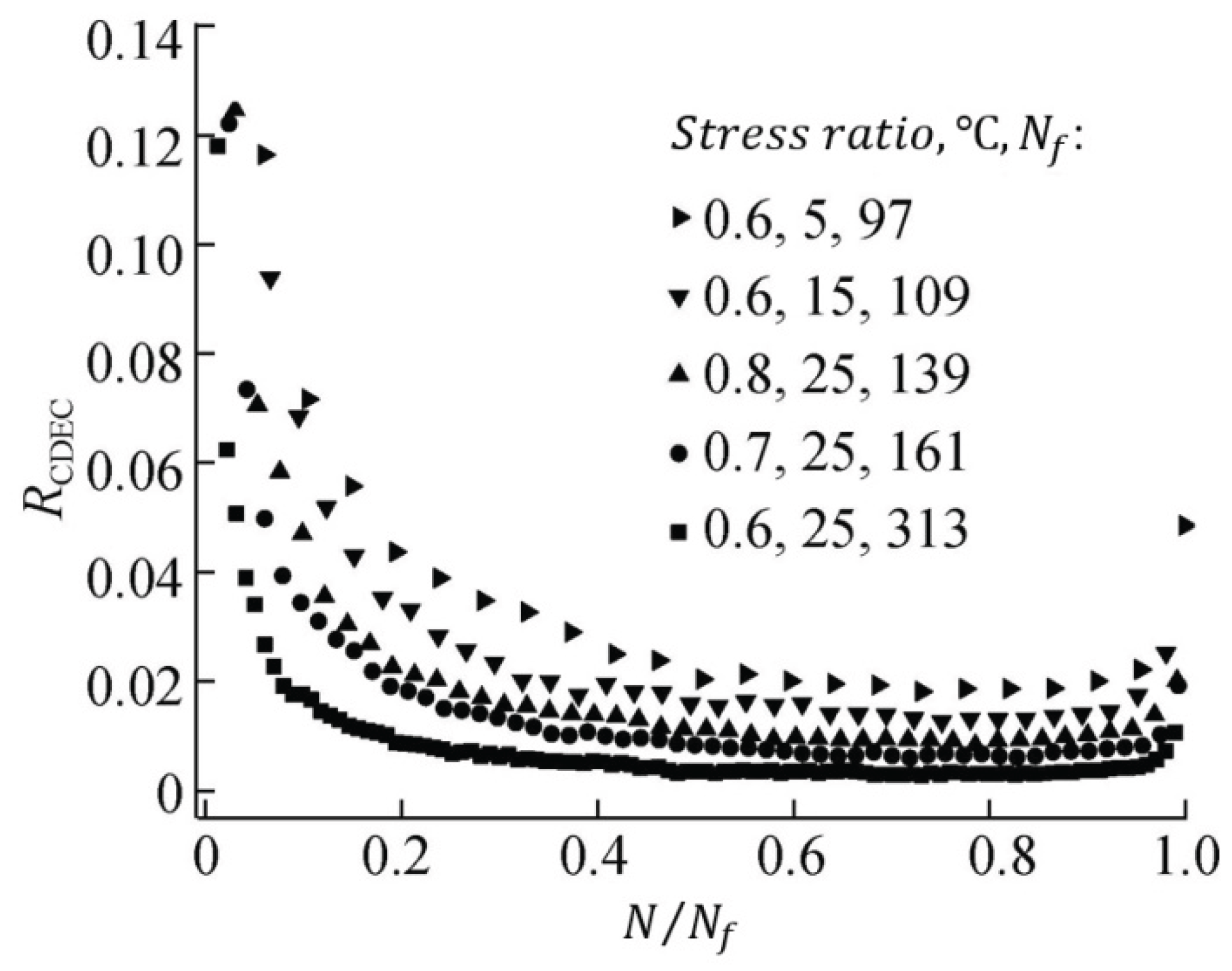

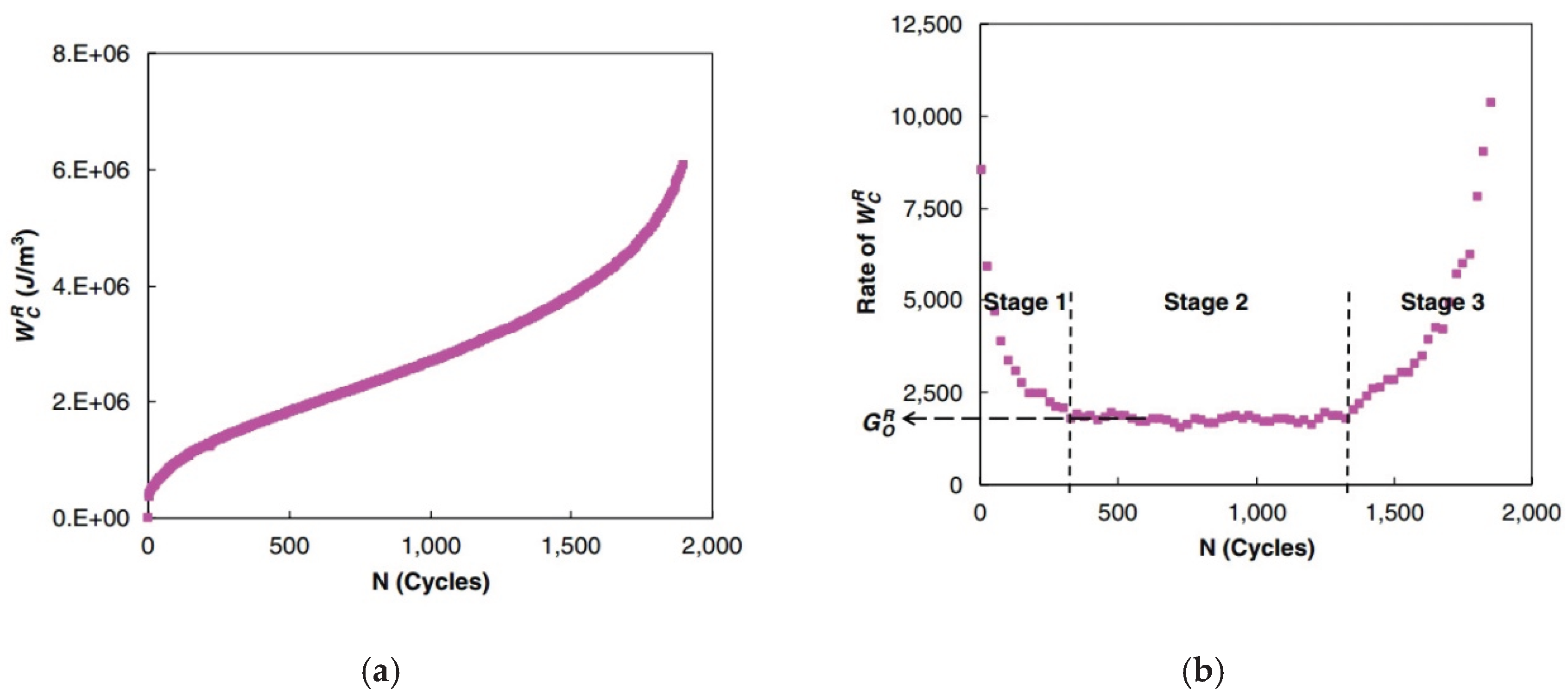

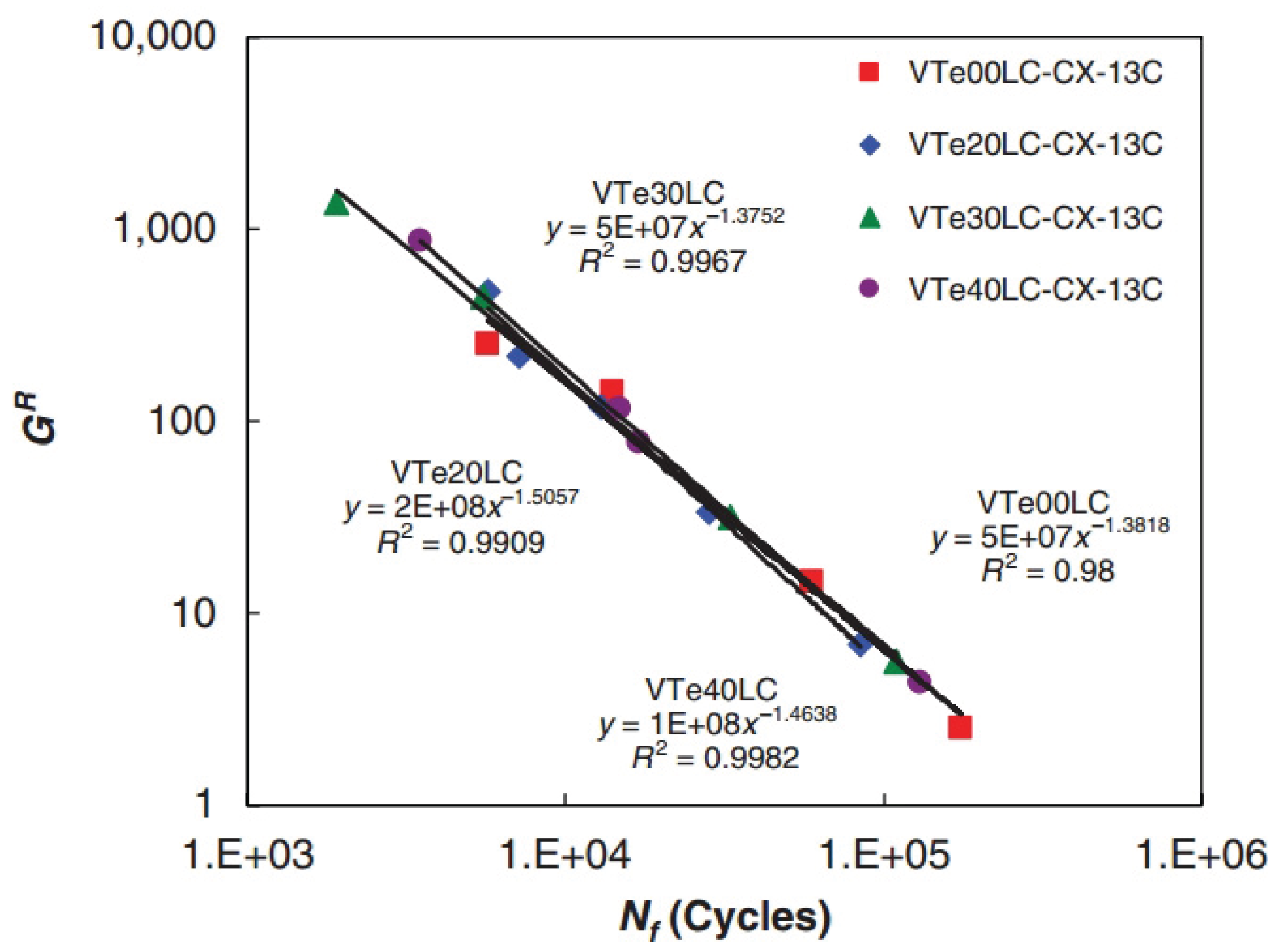

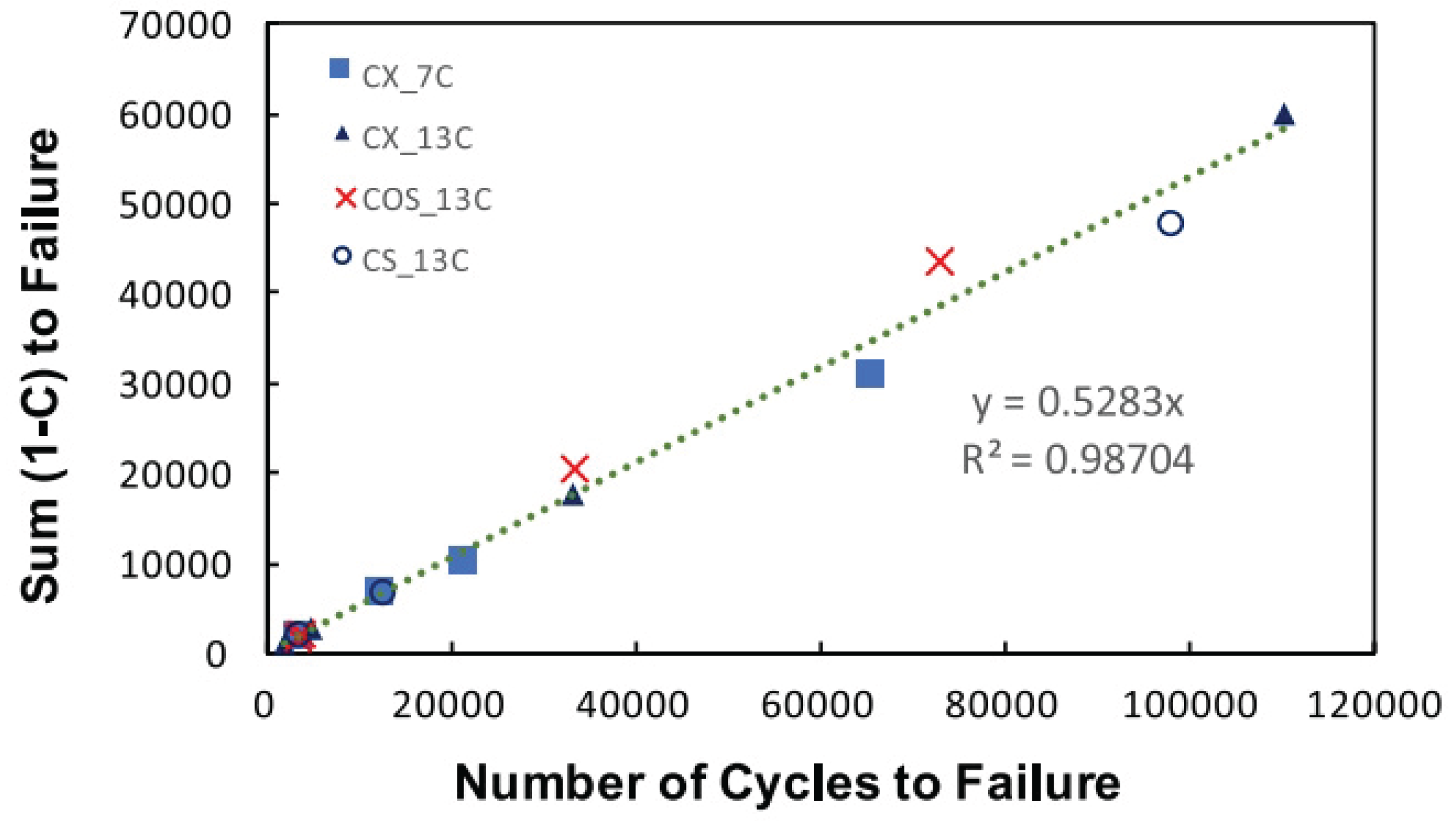

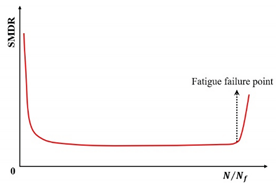

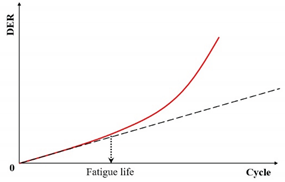

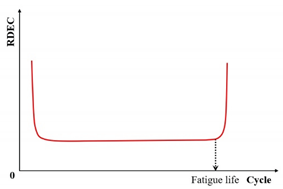

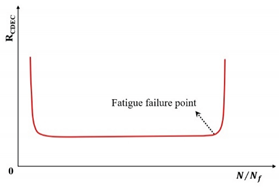

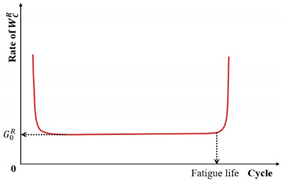

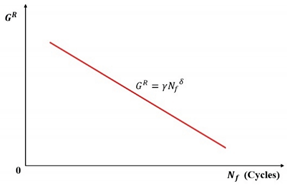

- The fatigue damage evolution metrics—including stiffness modulus degradation ratio (SMDR), ratio of dissipated energy change (RDEC), cumulative dissipated energy change (RCDEC), pseudo strain energy release rate (), and average dissipated pseudo energy rate ()—demonstrate characteristic U-shaped trajectories when plotted against loading cycles () in cyclic fatigue tests. The plateau value (PV) serves as a quantitative indicator of asphalt mixtures' fatigue endurance, while the critical transition point marking the abrupt shift from Stage II (steady-state damage accumulation) to Stage III (accelerated crack propagation) provides a physically anchored failure criterion. These findings collectively suggest that formulating analogous constitutive relationships to Equation (24), grounded in energy dissipation mechanisms, could enable precise determination of fatigue failure thresholds.

- The artificial neural network (ANN) framework emerges as a promising computational approach for fatigue life prediction in asphalt mixtures. While its predictive capability is contingent upon the comprehensiveness of existing fatigue datasets and algorithmic sophistication, ANN essentially functions as a data-driven predictive framework. Furthermore, this methodology holds significant potential for establishing systematic validation protocols to quantitatively assess the sensitivity thresholds and operational domains of established failure criteria under multi-parametric loading scenarios.

- The implementation of fatigue failure criteria requires rigorous field validation through in-situ monitoring of asphalt pavements subjected to multi-axial stress states and hygrothermal fluctuations. Furthermore, advancing predictive fidelity demands a synergistic integration of experimental characterization (e.g., controlled laboratory ageing protocols) and computational modeling frameworks (e.g., discrete element method coupled with viscoplasticity theory). Critical research priorities should include: (1) quantitative benchmarking protocols for cross-criteria reliability assessments, and (2) domain-specific validity assessments through multivariate sensitivity analyses across material gradations and climatic regimes.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HMA | Hot mix asphalt |

| HPABs | High-polymer asphalt binders |

| HMABs | High-modulus asphalt binders |

| WMA | Warm-mix asphalt |

| RAP | Reclaimed asphalt pavement |

| DSR | Dynamic shear rheometer |

| LAS | Linear amplitude sweep |

| TS | Time sweep |

| ASR | Annular shear rheometer |

| FAM | Fine aggregate matrix |

| AC | Asphalt concrete |

| SCB | Semi-circular beam |

| DCT | Disk compact tension |

| SENB | Single-edge notched beam |

| DENP | Double-edge notched prism |

| UGR-FACT | University of Granada-Fatigue Asphalt Cracking Test |

| DMA | Dynamic mechanical analyzer |

| VECD | Viscoelastic continuum damage |

| VEFM | Viscoelastic fracture mechanics |

| ANN | Artificial neural network |

| SMDR | Stiffness modulus degradation ratio |

| SMD | Stiffness modulus degradation |

| LVDT | Linear variable differential transformer |

| DER | Dissipated energy ratio |

| RDEC | Ratio of dissipated energy change |

| PV | Plateau value |

| RCDEC | Ratio of cumulative dissipated energy change |

| DCSE | Dissipated creep strain energy |

| FE | Fracture energy |

| EE | Elastic energy |

| SIF | Stress intensity factor |

| DPSE | Dissipated pseudo-strain energy |

| S-VECD | Simplified viscoelastic continuum damage |

| PSE | Pseudo strain energy |

| I-FIT | Illinois flexibility index test |

References

- Ahmed, T. M.; Al-Khalid, H.; Ahmed, T. Y. , Review of techniques, approaches and criteria of hot-mix asphalt fatigue. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2019, 31(12), 03119004. [Google Scholar]

- Gudipudi, P. P.; Underwood, B. S. , Reliability analysis of fatigue life prediction from the viscoelastic continuum damage model. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2016; 2576, 1, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi, A.; Sabouri, M.; Kim, Y. R. , Fatigue life and endurance limit prediction of asphalt mixtures using energy-based failure criterion. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2017, 18(11), 990–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Safaei, F.; Castorena, C. , Material nonlinearity in asphalt binder fatigue testing and analysis. Materials & Design, 2017; 133, 376–389. [Google Scholar]

- Shadman, M.; Ziari, H. , Laboratory evaluation of fatigue life characteristics of polymer modified porous asphalt: A dissipated energy approach. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 138, 434–440. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X. Research on fatigue damage of asphalt mortar and asphalt mixture based on viscoelastic continuous damage model. Changsha University of Science & Technology, Changsha, 2021.

- Sudarsanan, N.; Kim, Y. R. , A critical review of the fatigue life prediction of asphalt mixtures and pavements. Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering-English Edition, 2022; 9, 5, 808–835. [Google Scholar]

- Oteki, D.; Yeneneh, A.; Gedafa, D.; Suleiman, N. , Evaluating the fatigue-cracking resistance of North Dakota’s asphalt mixtures. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2024; 2678, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Navarro, F.; Rubio-Gámez, M. C. , A review of fatigue damage in bituminous mixtures: Understanding the phenomenon from a new perspective. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 113, 927–938. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.; Lee, S.; Park, M.; Yoo, P.; Hong, Y. , Preparation and characterization of microcapsule-containing self-healing asphalt. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2015, 29, 330–337. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, S.; Hu, L.; Xia, C.; Wang, X.; Borges Cabrera, M.; Guo, S.; Chen, J. , Development of fatigue damage model of asphalt mixtures based on small-scale accelerated pavement test. Construction and Building Materials 2020, 260, 119930. [Google Scholar]

- Mensching, D.; Rahbar-Rastegar, R.; Underwood, S.; Sias, J. , Identifying indicators for fatigue cracking in hot-mix asphalt pavements using viscoelastic continuum damage principles. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2016; 2576, 1, 28–39. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. R.; Lee, H. J.; Little, D. N. In Fatigue characterization of asphalt concrete using viscoelasticity and continuum damage theory, Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists Technical Sessions, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA, 1997; AAPT: Salt Lake City, Utah, USA, pp 520-569.

- Pouget, S.; Sauzéat, C.; Benedetto Hervé, D.; Olard, F. , Viscous energy dissipation in asphalt pavement structures and implication for vehicle fuel consumption. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2012, 24(5), 568–576. [Google Scholar]

- Ghuzlan, K. A.; Carpenter, S. H. , Fatigue damage analysis in asphalt concrete mixtures using the dissipated energy approach. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering 2006, 33(7), 890–901. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Carpenter, S. , Application of the dissipated energy concept in fatigue endurance limit testing. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2005; 1929, 1, 165–173. [Google Scholar]

- Shan, L.; Tan, Y.; Underwood, S.; Kim, Y. , Separation of thixotropy from fatigue process of asphalt binder. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2011; 2207, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sadek, H.; Masad, E.; Al-Khalid, H.; Sirin, O. , Probabilistic analysis of fatigue life for asphalt mixtures using the viscoelastic continuum damage approach. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 126, 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, R. , Properties of aged asphalt binder related to asphalt concrete fatigue life. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 1997, 66, 604–632. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, A.; Anderson, D. A. , New test protocol to measure fatigue damage in asphalt mixtures. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2005, 6(4), 485–514. [Google Scholar]

- Safaei, F.; Lee, J.-s.; Nascimento, L. A. H. d.; Hintz, C.; Kim, Y. R. , Implications of warm-mix asphalt on long-term oxidative ageing and fatigue performance of asphalt binders and mixtures. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2014, 15 sup1, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monismith, C. L. In Fatigue characteristics of asphalt paving mixtures and their use in pavement design, Proceedings of the 18th Paving Conference, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, 1981; University of New Mexico, Albuquerque.

- Yuan, M. Research on fatigue failure mechanism of asphalt mixtures using digital speckle correlation method. South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, 2013.

- Wang, C. Rheological characterization on paving performance of asphalt mixture. Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, 2015.

- Wang, Y. Z.; Kim, Y. R. , Development of a pseudo strain energy-based fatigue failure criterion for asphalt mixtures. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2019, 20(10), 1182–1192. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO, Standard method of test for determining the damage characteristic curve and failure criterion using the asphalt mixture perfromance tester (AMPT) cyclic fatigue test. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, D.C., 2018; Vol. AASHTO TP 107-18.

- Sousa, J.; Pais, J.; Prates, M.; Barros, R.; Langlois, P.; Leclerc, A.-M. , Effect of aggregate gradation on fatigue life of asphalt concrete mixes. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1998; 1630, 62–68. [Google Scholar]

- Di Benedetto, H.; Ashayer Soltani, A.; CHAVEROT, P. , Fatigue damage for bituminous mixtures: A pertinent approach. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 1996, 65, 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Jia, Y.; Yang, T.; Du, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y. , Fatigue performance evaluation of asphalt mixtures based on energy-controlled loading mode. Construction and Building Materials 2017, 157, 348–356. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, A. M.; Gilchrist, M. D. , Evaluating four-point bend fatigue of asphalt mix using image analysis. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2004, 16(1), 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-R.; Little, D. N.; Lytton, R. L. , Fatigue and healing characterization of asphalt mixtures. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2003, 15(1), 75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Branco, V. T. F. C. A unified method for the analysis of nonlinear viscoelasticity and fatigue cracking of asphalt mixture using the dynamic mechanical analyzer. Ph.D. dissertation, Texas A & M University, Texas, 2008.

- BSI, Bituminous mixtures—Test methods for hot mix asphalt. BSI (British Standard Institution): London, 2012; Vol. BS EN 12697-24.

- AASHTO, Standard method of test for determining the fatigue life of compacted asphalt mixtures subjected to repeated flexural bending. AASHTO: Washington, D.C., 2017; Vol. AASHTO T 321-17.

- ASTM, Standard test method for determining fatigue failure of compacted asphalt concrete subjected to repeated flexural bending. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, 2010; Vol. ASTM D7460-10.

- Pronk, A. C.; Poot, M. R.; Jacobs, M. M. J.; Gelpke, R. F. , Haversine fatigue testing in controlled deflection mode: Is it possible? In Transportation Research Board 89th Annual Meeting, Washington DC, United States, 2010.

- Yang, K.; Cui, H.; Liu, P.; Zhu, M.; An, Y. , Accuracy analysis of fatigue life prediction in asphalt binders under multiple aging conditions based on simplified viscoelastic continuum damage (S-VECD) approach. Construction and Building Materials 2024, 435, 136868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shen, S.; Shi, B.; Wang, H. , Characterization of the fatigue behavior of asphalt mixture under full support using a Wheel-tracking Device. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 277, 122326. [Google Scholar]

- Mull, M. A.; Stuart, K.; Yehia, A. , Fracture resistance characterization of chemically modified crumb rubber asphalt pavement. Journal of Materials Science 2002, 37(3), 557–566. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, L. N.; Kim, M.; Challa, H. Development of Performance-based Specifications for Louisiana Asphalt Mixtures; FHWA/LA.14/558; Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 2016.

- AASHTO, Standard method of test for determining the fracture potential of asphalt mixtures using the Illinois Flexibility Index Test (I-FIT). AASHTO: Washington, D.C., 2020; Vol. AASHTO TP 124-20.

- Ozer, H.; Al-Qadi, I. L.; Lambros, J.; El-Khatib, A.; Singhvi, P.; Doll, B. , Development of the fracture-based flexibility index for asphalt concrete cracking potential using modified semi-circle bending test parameters. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 115, 390–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Dave, E.; Buttlar, W.; Behnia, B. , Compact tension test for fracture characterization of thin bonded asphalt overlay systems at low temperature. Materials and Structures 2012, 45, 1207–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM, Standard test method for determining fracture energy of asphalt mixtures using the disk-shaped compact tension geometry. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, 2020; Vol. ASTM D7313-20.

- Kim, K. W.; El Hussein, M. , Variation of fracture toughness of asphalt concrete under low temperatures. Construction and Building Materials 1997, 11(7), 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braham, A.; Buttlar, W.; Ni, F. , Fracture characteristics of asphalt concrete in mixed-mode. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2010, 11(4), 947–968. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, Y.; Kim, Y.; Schapery, R.; Witczak, M. W.; Bonaquist, R. , A study of crack-tip deformation and crack growth in asphalt concrete using fracture mechanics. Asphalt Paving Technology, AAPT, 2004; 73, 697–730. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Navarro, F.; Rubio-Gámez, M. C. , UGR-FACT test for the study of fatigue cracking in bituminous mixes. Construction and Building Materials 2013, 43, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buannic, M.; Di Benedetto, H.; Ruot, C.; Gallet, T.; Sauzéat, C. In Fatigue Investigation of Mastics and Bitumens Using Annular Shear Rheometer Prototype Equipped with Wave Propagation System, 7th RILEM International Conference on Cracking in Pavements, Dordrecht, 2012//, 2012; Scarpas, A.; Kringos, N.; Al-Qadi, I.; A, L., Eds. Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, pp 805-814.

- Gudipudi, P. P.; Underwood, B. S. , Development of modulus and fatigue testprotocol for fine aggregate matrix for axial direction of loading. Journal of Testing and Evaluation 2017, 45(2), 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Ren, Q.; Qian, Z.; Wang, X. , Evaluating the effects of high RAP content and rejuvenating agents on fatigue performance of fine aggregate matrix through DMA flexural bending test. Materials 2019, 12(9), 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Benedetto, H.; Nguyen, Q. T.; Sauzéat, C. , Nonlinearity, heating, fatigue and thixotropy during cyclic loading of asphalt mixtures. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2011, 12(1), 129–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiada, W. A.; Zeiada, W. A.; Souliman, M. I.; Kaloush, K. E.; Mamlouk, M. S.; Underwood, B. S. , Comparison of fatigue damage, healing, and endurance limit with beam and uniaxial fatigue tests. Transportation Research Record, 2014; 2447, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Fang, C.; Wang, J.; Ma, Z.; Ye, Y. , Energy-based approach to predict fatigue life of asphalt mixture using three-point bending fatigue test. Materials 2018, 11(9), 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Di, L.; Yinshan, X.; Jiandong, H.; and Liu, W. , Fatigue behaviour of rock asphalt concrete considering moisture, high-temperature, and stress level. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2022, 23(13), 4638–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BSI, Bituminous mixtures, test methods, resistance to fatigue British Standards Institution: London, 2018; Vol. EN 12697-24.

- BSI, Bituminous mixtures, test methods, stiffness. British Standards Institution: London, 2018; Vol. EN 12697-26.

- Li, K.; Huang, M.; Zhong, H.; Li, B. , Comprehensive evaluation of fatigue performance of modified asphalt mixtures in different fatigue tests. Applied Sciences 2019, 9(9), 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y. , Fatigue behaviours of asphalt mixture at different temperatures in four-point bending and indirect tensile fatigue tests. Construction and Building Materials 2021, 273, 121675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AASHTO, Standard method of test for determining the dynamic modulus of asphalt mixtures using the indirect tension test. American Association of State and Highway Transportation Officials: Washington DC, 2018; Vol. AASHTO TP131.

- AASHTO, Standard specification for developing dynamic modulus master curves for asphalt mixtures using the indirect tension testing method. American Association of State and Highway Transportation Officials: Washington DC, 2018; Vol. AASHTO PP96.

- AASHTO, Standard specification for preparation of indirect tension performance test specimens. American Association of State and Highway Transportation Officials: Washington DC, 2018; Vol. AASHTO PP95.

- Ahmed, T.; Al-Khalid, H. , A new approach in fatigue testing and evaluation of hot mix asphalt using a dynamic shear rheometer. In 6th International Conference on Bituminous Mixtures and Pavements, Thessaloniki, 2015; pp 351-359.

- Apostolidis, P.; Kasbergen, C.; Bhasin, A.; Scarpas, T.; Erkens, S. , Study of asphalt binder fatigue with a new dynamic shear rheometer geometry. Transportation Research Record Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2018, 2672, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (CEN), E. C. f. S. , Bituminous mixtures-test methods-part 44: crack propagation by semi-circular bending test. CEN: Brussels, 2019; Vol. EN 12697-44.

- Kim, Y.-R.; Little, D.; Lytton, R.; D'Angelo, J.; Davis, R.; Rowe, G.; Reinke, G.; Marasteanu, M.; Masad, E.; Roque, R.; Tashman, L. , Use of dynamic mechanical analysis (DMA) to evaluate the fatigue and healing potential of asphalt binders in sand asphalt mixtures. Asphalt Paving Technology: Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists-Proceedings of the Technical Sessions, 2002; 71, 176–206. [Google Scholar]

- Delaporte, B.; Van Rompu, J.; Di Benedetto, H.; Chaverot, P.; Gauthier, G. , New procedure to evaluate fatigue of bituminous mastics using an annular shear rheometer prototype. Pavement Cracking: Mechanisms, Modeling, Detection, Testing and Case Histories, 2008; 457–467. [Google Scholar]

- Rompu, J. V.; Benedetto, H. D.; Gauthier, G.; Gallet, T. , Advanced testing and characterization of bituminous materials, two volume set. CRC Press: 2009; p 12.

- AASHTO, Estimating damage tolerance of asphalt binders using the linear amplitude sweep. AASHTO: Washington DC, 2014; Vol. AASHTO TP 101.

- Castorena, C.; Velasquez, R.; Johnson, C.; Bahia, H. , Modification and validation of linear amplitude sweep test for binder fatigue specification. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2011; 2207, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Braham, A.; Underwood, B. S. , State of the art and practice in fatigue cracking evaluation of asphalt concrete pavements. Association of Asphalt Paving Technology: Lino Lakes, MN, 2016.

- Hveem, F. N. Pavement deflections and fatigue failures; Washington, D.C., 1955; pp 43-87.

- Zhiyong, W. Research on cumulative fatigue damage of asphalt mixture and asphalt layer based on multi-level amplitude loading. South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, China, 2014.

- Li, H.; Luo, X.; Zhang, Y.; Leng, Z. , Viscoelastic fracture mechanics-based fatigue life model in asphalt-filler composite system. Engineering Fracture Mechanics 2023, 292, 109589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Amirkhanian, S.; Juang, C. H. , Prediction of fatigue life of rubberized asphalt concrete mixtures containing reclaimed asphalt pavement using artificial neural networks. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2009, 21(6), 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, T. M.; Green, P. L.; Khalid, H. A. , Predicting fatigue performance of hot mix asphalt using artificial neural networks. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2017, 18(sup2), 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Gao, R.; Huang, W. , Asphalt mixture fatigue life prediction model based on neural network. In CICTP 2017, 2018; pp 1292-1299.

- Wang, Z.; Guo, N.; Wang, S.; Xu, Y. , Prediction of highway asphalt pavement performance based on Markov chain and artificial neural network approach. The Journal of Supercomputing 2021, 77(2), 1354–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houl'ik, J.; Valentin, J.; Nezerka, V. , Predicting the fatigue life of asphalt concrete using neural networks. ArXiv, 2024; arXiv:abs/2406.01523. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, A.; Yu, M.; Zhou, X.; Lv, Z.; Song, P. , Fatigue damage and full-cycle life estimation of rubber asphalt mixture. Journal of Building Materials 2018, 21(4), 620–625. [Google Scholar]

- Monismith, C. L.; Secor, K. E.; Blackmer, E. W. , Asphalt mixture behavior in repeated flexure. Proceedings of Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 1961, 30, 188–222. [Google Scholar]

- Monismith, C. L.; Deacon, J. A. , Fatigue of asphalt paving mixtures. Transportation Engineering Journal of ASCE 1969, 95(2), 317–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pell, P. S. In Fatigue characteristics of bitumen and bituminous mixes, First International Conference on the Structural Design of Asphalt Pavements, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1962; National Academy of Sciences: Ann Arbor, Michigan, pp 310-323.

- Monismith, C. L. In Symposium on flexible pavement behavior as related to deflection, Part II — Significance of pavement deflections, Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists, 1962; pp 231-260.

- Epps, J. A.; Monismith, C. L. In Influence of mixture variables on the flexural fatigue properties of asphalt concrete, Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists, Los Angeles, 1969; Los Angeles, pp 423-464.

- Kingham, R. I. In Failure criteria from AASHO road test data, Third International Conference on the Structural Design of Asphalt Pavements, London, 1972; London, pp 656-669.

- Monismith, C. L.; Epps, J. A.; Kasianchuk, D. Asphalt mixture behavior in repeated flexure; TE 70-5; Institute of Transportation and Traffic Engineering: University of California, Berkeley, 1972.

- Witczak, M. W. In Design of full-depth asphalt airfield pavements, Third International Conference on the Structural Design of Asphalt Pavements, London, 1972; London, pp 550-567.

- Claessen, A. I. M.; Edwards, J. M.; Sommer, P.; Ugé, P. In Asphalt pavement design, the shell method, Forth International Conference on the Structural Design of Asphalt Pavements, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1977; Ann Arbor, Michigan, pp 39-74.

- Di Benedetto, H.; Roche, C.; Baaj, H.; Pronk, A. C.; Lundström, R. , Fatigue of bituminous mixtures. Materials and Structures 2004, 37, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baaj, H.; Di Benedetto, H.; Chaverot, P. , Effect of binder characteristics on fatigue of asphalt pavement using an intrinsic damage approach. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2005, 6(2), 147–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstrom, R.; Di Benedetto, H.; Isacsson, U. , Influence of asphalt mixture stiffness on fatigue failure. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2004, 16(6), 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q. T.; Di Benedetto, H.; Sauzéat, C. , Determination of thermal properties of asphalt mixtures as another output from cyclic tension-compression test. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2012, 13(1), 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapsoba, N.; Sauzéat, C.; Di Benedetto, H. , Analysis of fatigue test for bituminous mixtures. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2013, 25(6), 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- READ, J. M.; Collop, A. C. , Practical fatigue characterization of bituminous mixes. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 1997, 66, 74–108. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, H. L. Determination of the stiffness moduli and fatigue endurance limits of asphalt pavements for perpetual pavement design. PhD thesis, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, 2022.

- Cheng, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, L.; Liu, L. , Critical position of fatigue damage within asphalt pavement considering temperature and strain distribution. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2021, 22(14), 1773–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellinen, T.; Christensen, D.; Rowe, G.; Sharrock, M. , Fatigue-transfer functions: how do they compare? Transportation Research Record 2004, 1896, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J. Study on fatigue performance of asphalt mixture. South China University of Technology, Guangzhou, 2005.

- Wen, H. , Use of fracture work density obtained from indirect tensile testing for the mix design and development of a fatigue model. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2013, 14(6), 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahadori, A. M.; Mansourkhaki, A.; Ameri, M. , A phenomenological fatigue performance model of asphalt mixtures based on fracture energy density. Journal of Testing and Evaluation 2015, 43(1), 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Castro, M.; Sánchez, J. A. , Estimation of asphalt concrete fatigue curves – A damage theory approach. Construction and Building Materials 2008, 22(6), 1232–1238. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, L.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, L. , Estimation of total fatigue life for in-service asphalt mixture based on accelerated pavement testing and four-point bending beam fatigue tests. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering 2018, 46(7), 557–566. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnaure, F.; Gravois, A.; Udron, J. , A new method for predicting the fatigue life of bituminous mixes. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 1980, 49, 499–529. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, T. M.; Ahmed, T. Y.; Al-Hdabi, A. , Evaluating fatigue performance of hot-mix asphalt using degradation parameters. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Construction Materials, 2018; 173, 3, 111–122. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO, Standard test method for determining the fatigue life of compacted hot mix asphalt (HMA) subjected to repeated flexural bending. 1996; Vol. AASHTO TP8-94.

- China, M. o. T. o. t. P. s. R. o. , Standard test methods of bitumen and bituminous mixtures for highway engineering. Renmin Communication Press: China, 2011; Vol. JTG E20—2011.

- Van Dijk, W. , Practical fatigue characterization of bituminous mixes. Journal of Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 1975, 44, 38–74. [Google Scholar]

- Tayebali, A.; Rowe, G.; Sousa, J. , Fatigue response of asphalt-aggregate mixtures. J. Assoc. Asphalt. Paving. Technol. 1992, 61, 333–360. [Google Scholar]

- Tayebali, A. A.; Deacon, J. A.; Coplantz, J. S.; Monismith, C. L. In Modeling fatigue response of asphalt-aggregate mixtures, Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists: Technical Sessions, Austin, Texas, USA, 1993; Austin, Texas, USA, pp 385-421.

- Di Benedetto, H.; Ashayer Soltani, A.; CHAVEROT, P. , Fatigue damage for bituminous mixture: A pertinent approach. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 1996, 65, 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H. J. Uniaxial constitutive modeling of asphalt concrete using viscoelasticity and continuum damage theory. PhD thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, N.C., 1996.

- Lee, H.-J.; Daniel Jo, S.; Kim, Y. R. , Continuum damage mechanics-based fatigue model of asphalt concrete. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2000, 12(2), 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, G. M. , Performance of asphalt mixtures in the trapezoidal fatigue test. Journal of Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 1993, 62, 344–384. [Google Scholar]

- Copper, K.; Pell, P. S. The effect of mix variables on the fatigue strength of bituminous materials; Transport and Road Research Laboratory: 1974; pp 1-69.

- SHRP Fatigue response of asphalt-aggregate mixtures; National Research Council: Washington D.C., 1994.

- READ, J. M.; Collop, A. C. , Practical fatigue characterization of bituminous paving mixture. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 1997, 66, 74–108. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, L.; Cheng, H.; Liu, L.; Cao, W. , Fatigue characteristics of in-situ emulsified asphalt cold recycled mixtures. Journal of Tongji University. Natural Science, 2017; 45, 11, 1648–1654+1687. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, G.; Bouldin, M. G. In Improved techniques to evaluate the fatigue resistance of asphaltic mixtures, In Proceedings of the 2nd Eurasphalt & Eurobitume Congress Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 01/01, 2000; Barcelona, Spain, pp 754-763.

- Li, N.; Pronk, A. C.; Molenaar, A.; Ven, M.; Wu, S. , Comparison of uniaxial and four-point bending fatigue tests for asphalt mixtures. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2013; 2373, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Abhijith, B. S.; Narayan, S. P. A. , Evolution of the modulus of asphalt concrete in four-point beam fatigue tests. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2020, 32(10), 04020310. [Google Scholar]

- Lundström, R.; Isacsson, U. , Characterization of asphalt concrete deterioration using monotonic and cyclic tests. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2003, 4(3), 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Mollenhauer, K.; Wistuba, M. , Evaluation of hot-mix asphalt susceptibility to temperature-induced top-down fatigue cracking by means of Uniaxial Cyclic Tensile Stress Test. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2012, 13(1), 171–190. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Sabouri, M.; Guddati, M. N.; Kim, Y. R. , Development of a failure criterion for asphalt mixtures under fatigue loading. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2013, 14(sup2), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Castorena, C.; Zhang, J.; Richard Kim, Y. , Unified failure criterion for asphalt binder under cyclic fatigue loading. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2015, 16(sup2), 125–148. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Lu, X. , Energy based laboratory fatigue failure criteria for asphalt materials. Journal of Testing and Evaluation 2011, 39(3), 313–320. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Huang, W. , Laboratory investigation on fatigue performance of modified asphalt concretes considering healing. Construction and Building Materials 2016, 113, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ameri, M.; Yeganeh, S.; Erfani Valipour, P. , Experimental evaluation of fatigue resistance of asphalt mixtures containing waste elastomeric polymers. Construction and Building Materials 2019, 198, 638–649. [Google Scholar]

- Airey, G.; Rahimzadeh, B.; Collop, A. C. , Linear and Nonlinear Rheological Properties of Asphalt Mixtures. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 2002, 71, 160–196. [Google Scholar]

- Reese, R. A. , Properties of aged asphalt binder related to asphalt concrete fatigue life. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 1997, 66, 604–632. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H.; Kim, Y.; Lee, S. , Prediction of asphalt mix fatigue life with viscoelastic material properties. Transportation Research Record 2003, 1832(1), 139–147. [Google Scholar]

- Sabouri, M.; Kim, Y. R. , Development of a failure criterion for asphalt mixtures under different modes of fatigue loading. Transportation Research Record Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2014; 2447, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Khateeb, G.; Shenoy, A. , A distinctive fatigue failure criterion. Asphalt Paving Technology: Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists-Proceedings of the Technical Sessions, 2004; 73, 585–622. [Google Scholar]

- Kutay, M. E.; Gibson, N.; Youtcheff, J. , Conventional and viscoelastic continuum damage (VECD) - based fatigue analysis of polymer modified asphalt pavements. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 2008, 77, 395–435. [Google Scholar]

- Ashayer Soltani, M. A. Comportement en fatigue des enrobés bitumeux. Ph.D. thesis, Ecole Nationale des Travaux Publics de l’Etat (ENTPE)—Institut National des Sciences Appliquées de Lyon (INSA), Lyon, France, 1998.

- Baaj, H. Comportement à la fatigue des matériaux granulaires traités aux liants hydrocarbonés. Ph.D. thesis, Ecole Nationale des Travaux Publics de l’Etat (ENTPE) and Institut National des Sciences Appliquées de Lyon (INSA), Lyon, France, 2002.

- Luo, X.; Luo, R.; Lytton, R. , Modified paris's law to predict entire crack growth in asphalt mixtures. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2013; 2373, 54–62. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S. Dissipated energy concepts for HMA performance: fatigue and healing. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chomton, G.; Valyer, P. J. In Applied rheology of asphalt mixes - practical applications, Third International Conference on the Structural Design of Asphalt Pavement, London, England, 1972; London, England, pp 214-225.

- Van Dijk, W.; Moreaud, H.; Quedeville, A.; Ugé, P. In The fatigue of bitumen and bituminous mixes, Third International Conference on the Structural Design of Asphalt Pavement, London, England, 1972; London, England, pp 355-366.

- Dondi, G.; Vignali, V.; Pettinari, M.; Mazzotta, F.; Simone, A.; Sangiorgi, C. , Modeling the DSR complex shear modulus of asphalt binder using 3D discrete element approach. Construction and Building Materials 2014, 54, 236–246. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, S.; Shen, S. , Dissipated energy approach to study hot-mix asphalt healing in fatigue. Transportation Research Record 2006, 1970, 178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, J. S.; Bisirri, W.; Kim, Y. R. , Fatigue evaluation of asphalt mixtures using dissipated energy and viscoelastic continuum damage approaches. Asphalt Paving Technology: Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists-Proceedings of the Technical Sessions, 2004; 73, 557–583. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, W.; Visser, W. In The energy approach to fatigue for pavement design, Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists Proc, San Antonio, Texas, 01/01, 1977; San Antonio, Texas, pp 1-40.

- Pronk, A. C.; Hopman, P. C. , Energy dissipation: the leading factor of fatigue. In Highway research: sharing the benefits, Thomas Telford Publishing: London, 1991; pp 255-267.

- Hopman, P.; Kunst, P.; Pronk, A. In A renewed interpretation method for fatigue measurements-verification of Miner’s rule, 4th Eurobitume Symp, Brussels, Belgium, 1989; Association, E. B., Ed. European Bitumen Association: Brussels, Belgium, pp 557-561.

- Pronk, A. , Fatigue lives of asphalt beams in 2 and 4 point dynamic bending tests based on a "new" fatigue life definition using the dissipated energy concept. Ministerie van Verkeer en Waterstaat: The Hague, Netherlands, 1997.

- Rowe, G. M.; Bennert, T.; Blankenship, P.; Criqui, W.; Mamlouk, M.; Willes, J. R.; Steger, R.; Mohammad, L. The bending beam fatigue test improvements to test procedure definition and analysis; Asphalt Mixture Expert Task Group: Boton Rouge, LA, March 19-20, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO, Standard method of test for determining the fatigue life of compacted asphalt mixtures subjected to repeated flexural bending. AASHTO: Washington, D.C., 2014; Vol. AASHTO T 321-14.

- Zeiada, W. Endurance limit for HMA based on healing phenomenon using viscoelastic continuum damage analysis. Ph.D. thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, 2012.

- AASHTO, Standard method of test for determining the fatigue life of compacted asphalt mixtures subjected to repeated flexural bending. AASHTO: Washington, D.C., 2022; Vol. AASHTO T 321-22.

- ASTM, Standard test method for determining fatigue failure of compacted asphalt concrete subjected to repeated flexural bending. ASTM: 2010; Vol. D7460-10.

- Tsai, B.-W.; Harvey, J. T.; Monismith, C. L. , High temperature fatigue and fatigue damage process of aggregate-asphalt mixes. Asphalt Paving Technology: Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists-Proceedings of the Technical Sessions, 2002; 71, 345–385. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.; Guo, N.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J. , Research on fatigue life of rubber asphalt mixture based on stiffness modulus. Engineering Mechanics 2020, 37(4), 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- AASHTO, Standard method of test for determining the damage characteristic curve and failure criterion using the asphalt mixture performance tester (AMPT) cyclic fatigue test. AASHTO: Washington D.C., 2024; Vol. AASHTO T 400-24.

- Bonnetti, K.; Nam, K.; Bahia, H. , Measuring and defining fatigue behavior of asphalt binders. Transportation Research Record 2002, 1810, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ghuzlan, K.; Carpenter, S. , Energy-derived, damage-based failure criterion for fatigue testing. Transportation Research Record 2000, 1723, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, S. H.; Jansen, M. In Fatigue behavior under new aircraft loading conditions, Aircraft/Pavement Technology In the Midst of Change, Seattle, Washington, 1997; Seattle, Washington, pp 259-271.

- Carpenter, S. H.; Ghuzlan, K. A.; Shen, S. , Fatigue endurance limit for highway and airport pavements. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2003; 1832, 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, J. S.; Bisirri, W.; Kim, Y. R. , Fatigue evaluation of asphalt mixtures using dissipated energy and viscoelastic continuum damage approaches. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 2004, 73, 557–583. [Google Scholar]

- Bhasin, A.; Castelo Branco Veronica, T.; Masad, E.; Little Dallas, N. , Quantitative comparison of energy methods to characterize fatigue in asphalt materials. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2009, 21(2), 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Sutharsan, T. , Quantification of cohesive healing of asphalt binder and its impact factors based on dissipated energy analysis. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2011, 12(3), 525–546. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.; Huang, B.; Shu, X. , Characterizing fatigue behavior of asphalt mixtures utilizing loaded wheel tester. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2014, 26(1), 152–159. [Google Scholar]

- Nejad Fereidoon, M.; Notash, M.; Forough Seyed, A. , Evaluation of healing potential in unmodified and SBS-modified asphalt mixtures using a dissipated-energy approach. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 2015, 27(12), 04015060. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.; Fang, C.; Wang, J.; Ma, Z. , Method of fatigue life prediction for rubber asphalt mixture based on plateau value of dissipated energy ratio. Journal of Building Materials 2019, 22(1), 108–112. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C. Research on damage evolution and fatigue life prediction of asphalt mixture. Master's thesis, Shenyang Jianzhu University, Shenyang, 2019.

- Fang, C.; Guo, N.; You, Z.; Tan, Y.; Wang, L.; Wen, Y. , Fatigue damage characteristics for asphalt mixture based on energy dissipation history. Journal of South China University of Technology. Natural Science Edition 2021, 51(6), 1018–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Roque, R.; Birgisson, B.; Sangpetngam, B. , Identification and verification of a suitable crack growth law. Proceedings of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 2001, 70, 206–241. [Google Scholar]

- Roque, R.; Birgisson, B.; Sangpetngam, B.; Zhang, Z. , Hot mix asphalt fracture mechanics: A fundamental crack growth law for asphalt mixtures. Asphalt Paving Technology: Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists-Proceedings of the Technical Sessions, 2002; 71, 816–827. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. Identification of suitable crack growth law for asphalt mixture using the superpave indirect tensile test. Ph.D. thesis, University of Florida, Florida, 2000.

- Birgisson, B.; Montepara, A.; Romeo, E.; Roque, R.; Roncella, R.; Tebaldi, G. , Determination of fundamental tensile failure limits of mixtures. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 2007, 76, 303–344. [Google Scholar]

- Masad, E.; Castelo Branco, V. T. F.; Little, D. N.; Lytton, R. , A unified method for the analysis of controlled-strain and controlled-stress fatigue testing. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2008, 9(4), 233–246. [Google Scholar]

- Castelo Branco, V.; Masad, E.; Bhasin, A.; Little, D. , Fatigue analysis of asphalt mixtures independent of mode of loading. Transportation Research Record 2008, 2057, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. R.; LEE, H.-J.; Little, D. N. In Fatigue characterization of asphalt concrete using viscoelasticity and continuum damage theory, Asphalt Paving Technology 1997, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1997; Salt Lake City, Utah, pp 520-569.

- Paris, P.; Erdogan, F. , A critical analysis of crack propagation laws. Journal of Basic Engineering 1963, 85(4), 528–533. [Google Scholar]

- Erkens, S.; Moraal, J. , Cracking in asphalt concrete. HERON 1996, 41(1), 53–70. [Google Scholar]

- SHRP Development and validation of performance prediction models and specifications for asphalt binders and paving mixes; National Academy of Sciences: Washington D.C., 1993.

- Schapery, R. A. , Correspondence principles and a generalized J integral for large deformation and fracture analysis of viscoelastic media. International Journal of Fracture 1984, 25(3), 195–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schapery, R. A. In On viscoelastic deformation and failure behavior of composite materials with distributed flaws, Advances in Aerospace Structures and Materials, New York, 1981; ASME: New York, pp 5-20.

- Schapery, R. A. , Nonlinear viscoelastic and viscoplastic constitutive equations based on thermodynamics. Mechanics of Time-Dependent Materials, 1997; 1, 2, 209–240. [Google Scholar]

- Schapery, R. A. , Nonlinear viscoelastic and viscoplastic constitutive equations with growing damage. International Journal of Fracture 1999, 97(1), 33–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. R.; Little Dallas, N. , One-dimensional constitutive modeling of asphalt concrete. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 1990, 116(4), 751–772. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, J. S.; Kim, Y. R. , Development of a simplified fatigue test and analysis procedure using a viscoelastic continuum damage model. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 2002, 71, 619–650. [Google Scholar]

- Chehab, G.; Kim, Y.-R.; Schapery, R.; Witczak, M. W.; Bonaquist, R. , Time-temperature superposition principle for asphalt concrete with growing damage in tension state. Journal of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists 2002, 71, 559–593. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, B. S.; Kim, Y. R.; Guddati, M. N. , Improved calculation method of damage parameter in viscoelastic continuum damage model. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 2010, 11(6), 459–476. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.-S.; Kim, Y. , Performance-based moisture susceptibility evaluation of warm-mix asphalt concrete through laboratory tests. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 2014; 2446, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Bahia, H. , Characterizing fatigue of asphalt binders with viscoelastic continuum damage mechanics. Transportation Research Record 2009, 2126, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Bahia, H. U. , Evaluation of an accelerated procedure for fatigue characterization of asphalt binders. Road Materials and Pavement Design 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Safaei, F.; Castorena, C. , Temperature effects of linear amplitude sweep testing and analysis. Transportation research record 2016, 2574(1), 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safaei, F.; Castorena, C.; Kim, Y. R. , Linking asphalt binder fatigue to asphalt mixture fatigue performance using viscoelastic continuum damage modeling. Mechanics of Time-Dependent Materials, 2016; 20, 3, 299–323. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, B. S. , A continuum damage model for asphalt cement and asphalt mastic fatigue. International Journal of Fatigue 2016, 82, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Kim, Y. R. , Viscoelastic constitutive model for asphalt concrete under cyclic loading. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 1998, 124(1), 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Kim, Y. R. , Viscoelastic continuum damage model of asphalt concrete with healing. Journal of Engineering Mechanics 1998, 124(11), 1224–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, T.; Underwood, S.; Kim, Y. R. , Fatigue performance prediction of North Carolina mixtures using the simplified viscoelastic continuum damage model. Asphalt Paving Technology: Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists-Proceedings of the Technical Sessions, 2010; 79, 35–73. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J. Development of failure criteria for asphalt concrete mixtures under fatigue loading. M.S. thesis, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, North Carolina., 2012.

- Freire, R. A. Evaluation of the coarse aggregate influence in the fatigue damage using fine aggregate matrices with different maximum nominal sizes. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Ceará, 2015.

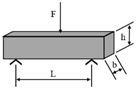

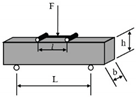

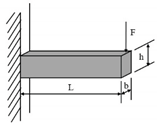

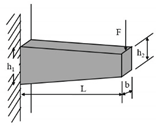

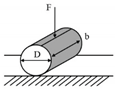

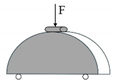

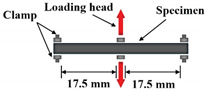

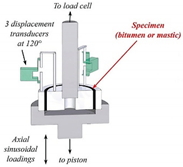

| Loading Mode/Test Tpye | Schematic Diagram | Material Type | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uniaxial compression/tension (UT/UC) |  |

AC | [26,33,52,53] |

| Beam bending (BB) |

Three-point bending (3PB) |

AC | [54,55] |

Four-point bending (4PB) |

[34,35] | ||

Two-point bending (2PB) |

[56,57,58] | ||

| Indirect tensile (IDT) |  |

AC | [59,60,61,62] |

| Dynamic shearing (DS) |  |

AC | [63,64] |

| Semi-circular bending (SCB) |  |

AC | [41,65] |

| Dynamic mechanical analyzer (DMA) |  |

FAM | [51,66] |

| Annular shear rheometer (ASR) |  |

Asphalt or mastic | [49,67,68] |

| Linear amplitude sweep (LAS) |  |

Asphalt | [69,70] |

| Criteria | Indicator | Schematic diagram | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stiffness modulus reduction criteria | Stiffness modulus |  |

[28,31,108,118] |

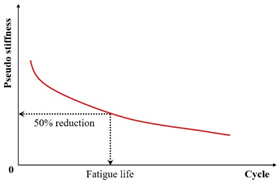

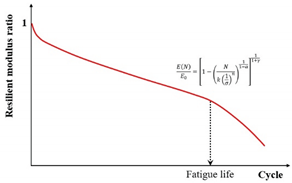

| Pseudo stiffness |  |

[112,113] | |

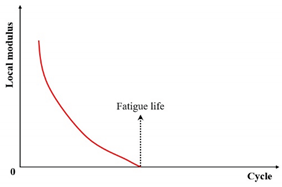

| Local modulus |  |

[121] | |

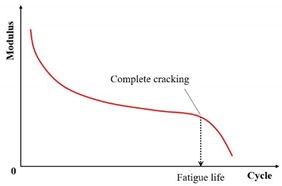

| Complete fracture |  |

[31] | |

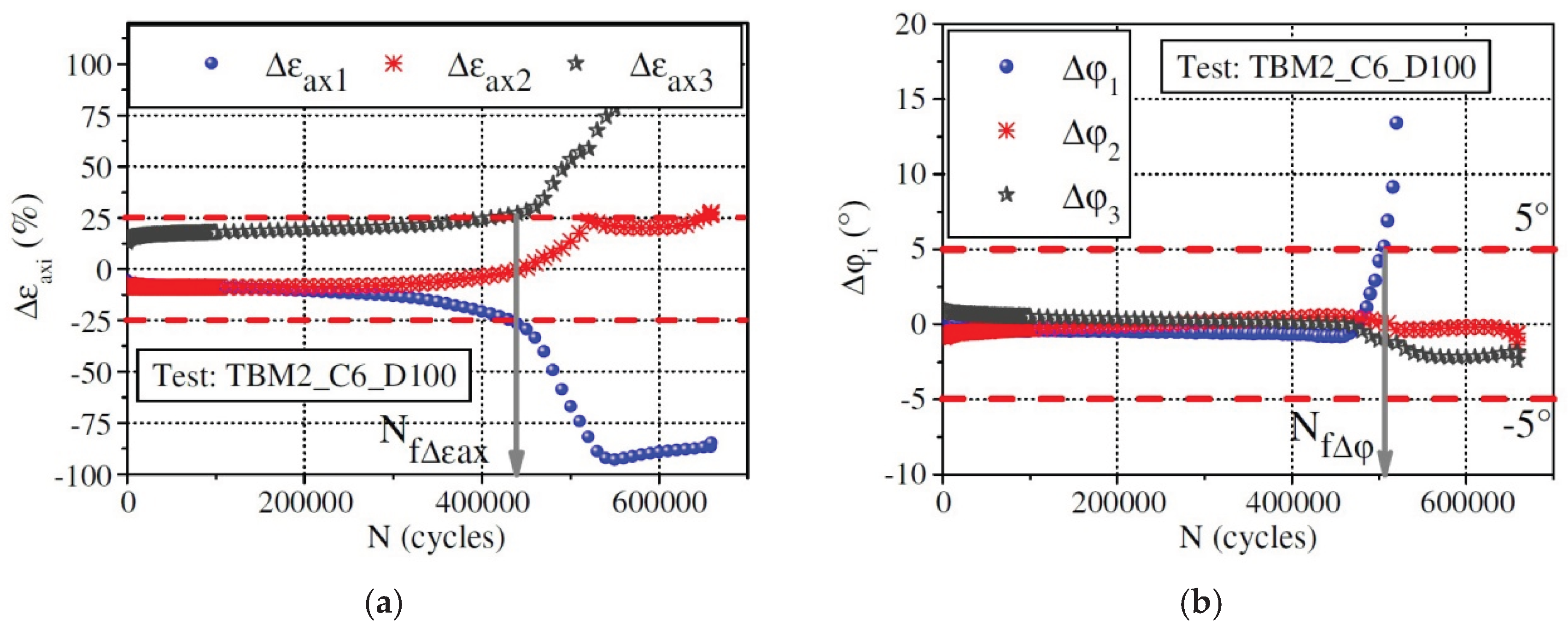

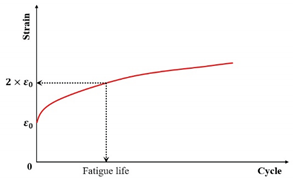

| Strain |  |

[117] | |

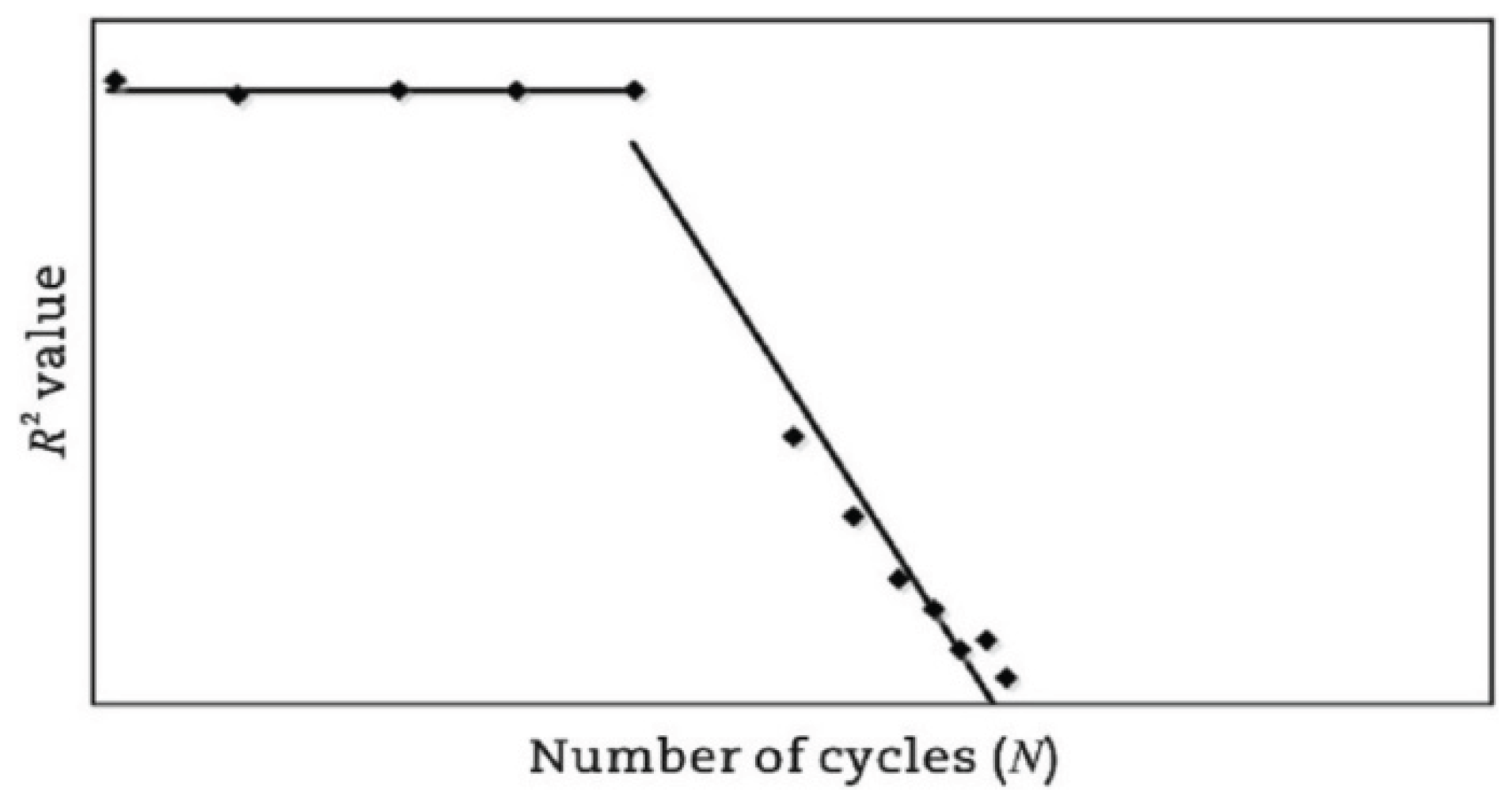

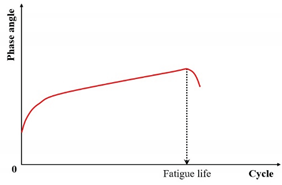

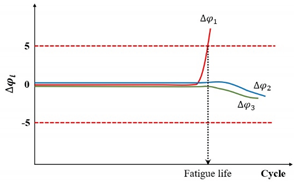

| Phase angle criterion | Phase angle |  |

[31,130,131] |

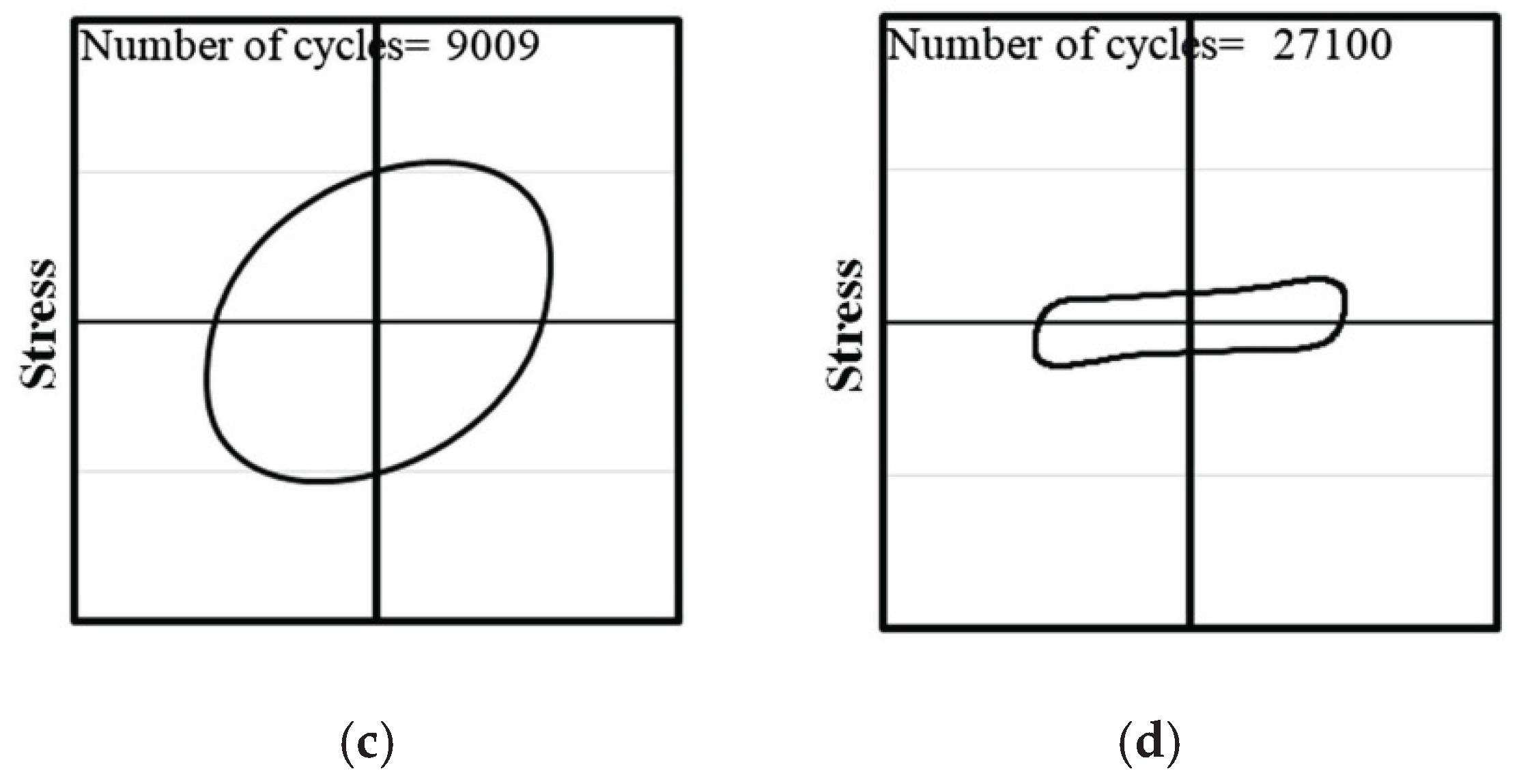

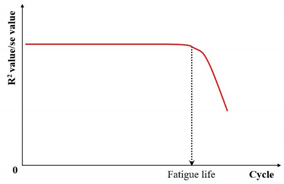

| Fitting change-point criterion | R2 value/se value |  |

[133,134] |

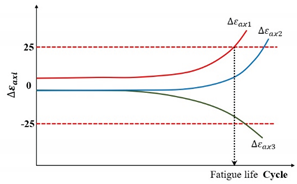

| Specimen homogeneity criterion | ) |  |

[135,136] |

| ) |  |

| Criteria | Indicator | Schematic diagram | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

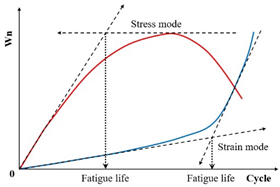

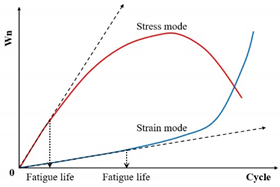

| Energy ratio criteria | Energy ratio (Wn) |  |

[147] |

|

[126] | ||

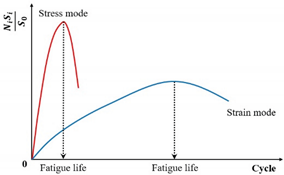

| Stiffness degradation ratio criterion | ) |  |

[150] |

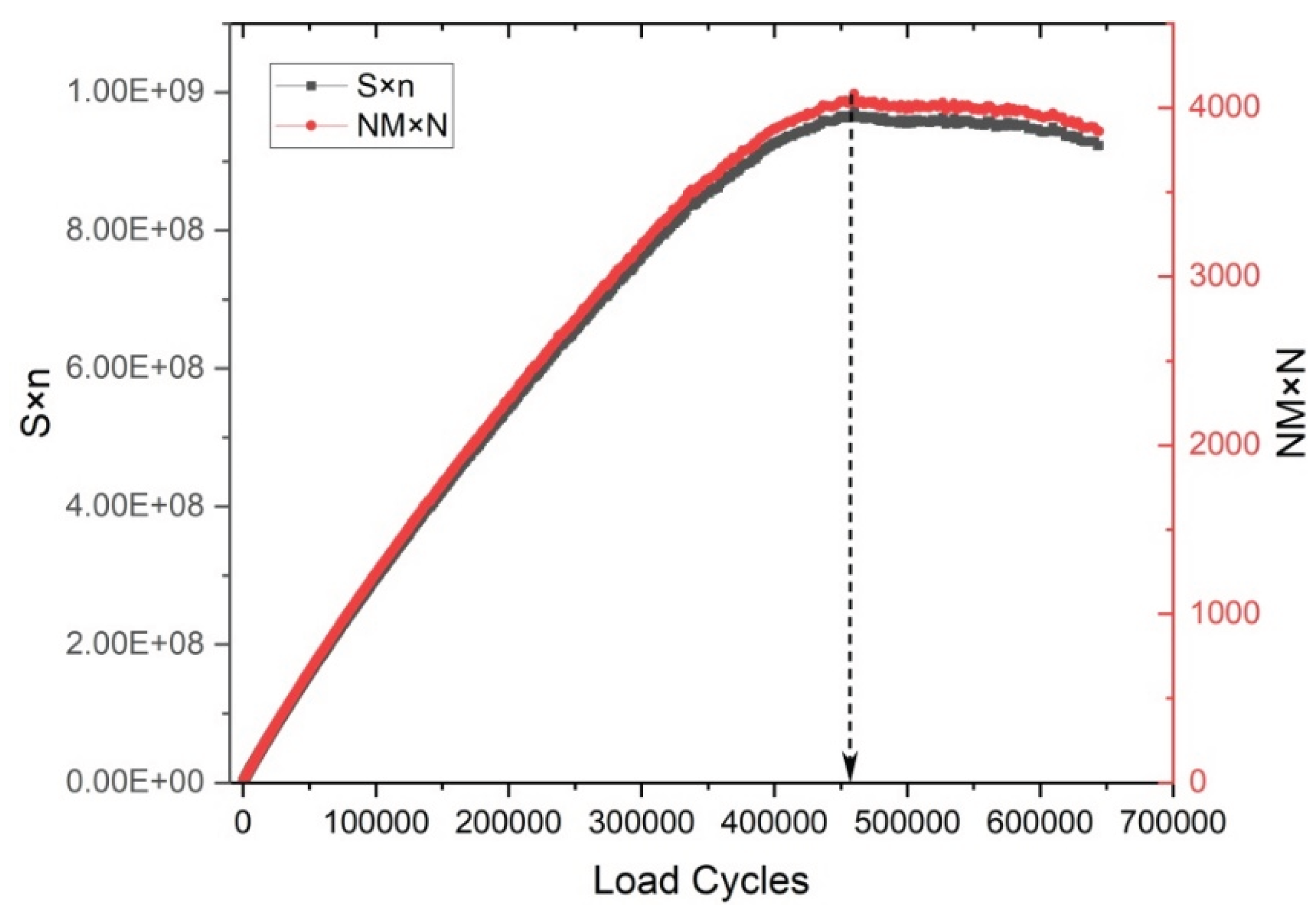

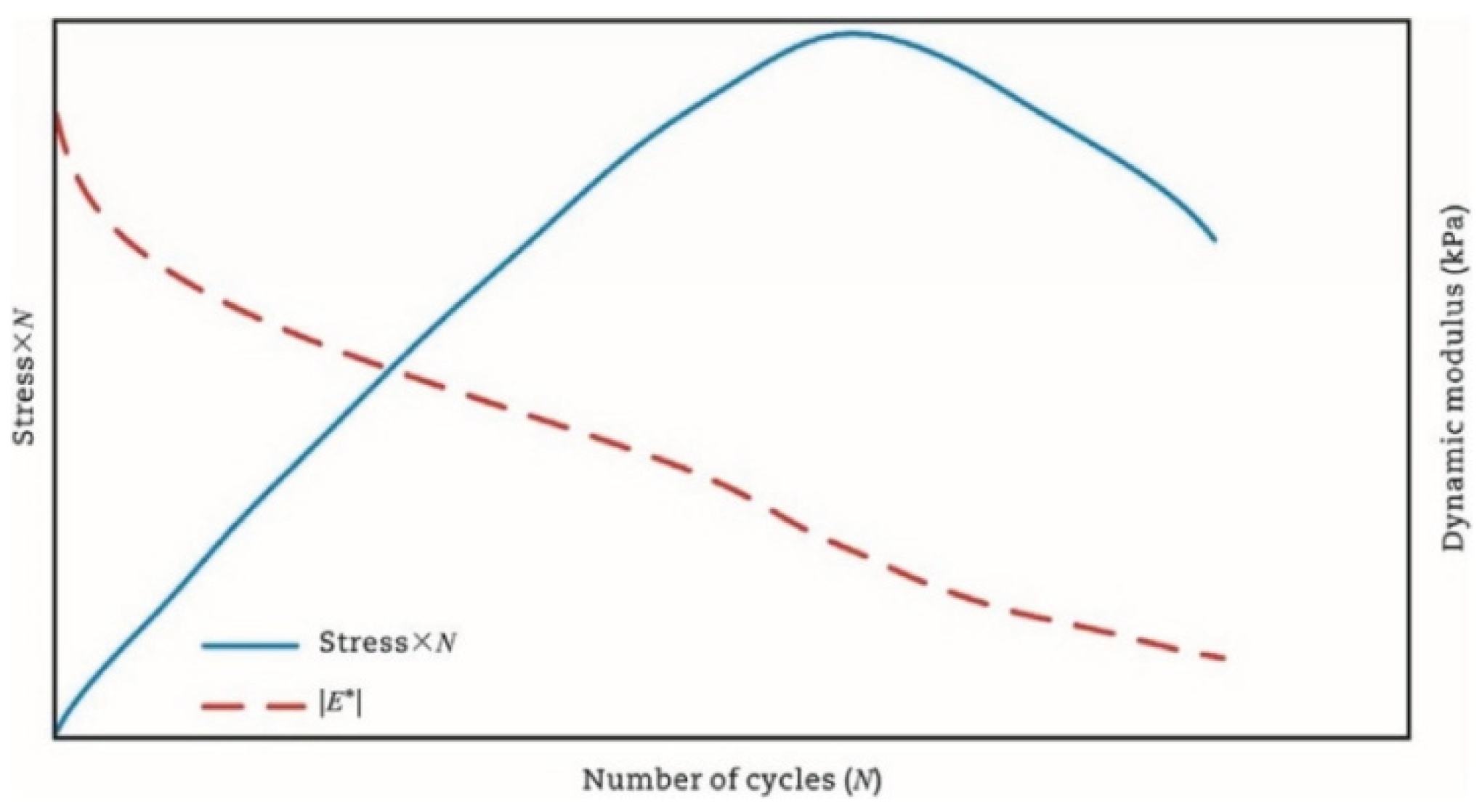

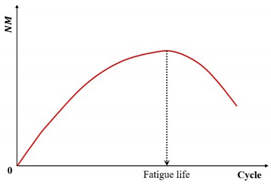

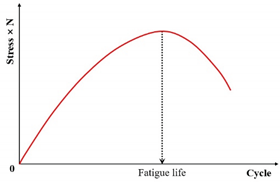

| The normalized modulus × cycles (NM) |  |

[151] | |

| ) |  |

[11] | |

| The stiffness modulus degradation ratio (SMDR) |  |

[154] | |

| Stress degradation ratio criterion | Stress × N |  |

[7] |

| Dissipated energy ratio criteria | The dissipated energy ratio (DER) |  |

[156] |

| The ratio of dissipated energy change (RDEC) |  |

[142,143,157] | |

| The ratio of cumulative dissipated energy change (RCDEC) |  |

[167] | |

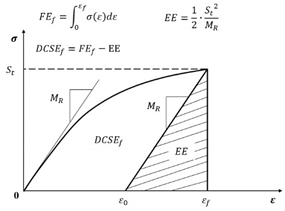

| Fracture energy criteria | )) |  |

[168,170,171] |

| Criteria | Indicator | Schematic diagram | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudo stiffness criterion | The pseudo stiffness value |  |

[194] |

| -based criterion | is the total released pseudo strain energy |  |

[124] |

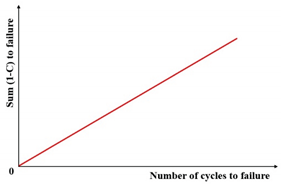

| -based criterion | ) |  |

[132] |

| -based criterion | ) |  |

[25] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).