1. Introduction

University course timetabling is a complex, real-world combinatorial optimization problem that lies at the intersection of operational research and educational logistics. It involves the assignment of a set of courses to discrete time periods, rooms, and instructors while satisfying a wide array of hard and soft constraints [

1]. These constraints are derived from institutional policies, physical limitations (e.g., room capacity), pedagogical requirements, and stakeholder preferences. The primary objective is to generate a conflict-free schedule that maximally utilizes available resources and minimizes inefficiencies such as idle times and underutilized rooms [

2]. The underlying problem is NP-hard, and its solution space grows exponentially with the number of courses, rooms, and timeslots involved, making exact optimization infeasible for large instances [

3].

Numerous variants of the timetabling problem have been examined in the literature, each characterized by distinct constraints and optimization criteria [

5]. The

Examination Timetabling Problem (ETP), for example, focuses on allocating final exams to timeslots and venues in a way that prevents clashes among students. The

Course Timetabling Problem (CTP) requires the repeated scheduling of lectures throughout a teaching period while managing overlapping student enrolments and instructor availability [

4]. The

Curriculum-Based Course Timetabling Problem (CB-CTT) introduces additional complexity by accounting for overlapping curricula, further tightening resource constraints. Although these problems share structural similarities, their operational implications differ: CTP requires weekly consistency, ETP typically operates under tighter room constraints, and CB-CTT introduces curriculum-wide conflicts [

6].

Beyond academic scheduling, structurally analogous problems appear in other domains such as nurse rostering, workforce shift scheduling, and machine-job scheduling [

7]. While these domains also involve resource-constrained assignments under temporal constraints, university timetabling differs in its unique interplay of pedagogical logic, non-uniform stakeholder preferences, and policy-driven constraints, which make general-purpose solvers less effective without significant domain-specific adaptation [

8]. Traditional approaches to course timetabling span a broad spectrum of methods. Exact techniques such as Integer Linear Programming (ILP) and Constraint Programming (CP) have been used in smaller instances where solution space exploration is tractable [

9]. For larger instances, metaheuristics such as Genetic Algorithms [

10], Simulated Annealing [

11], Tabu Search [

9], and Ant Colony Optimization have been applied to escape local optima and search the feasible space more efficiently. Notable contributions include the memetic algorithm , which performed competitively on standard CB-CTT benchmarks, and the adaptive large neighborhood search adopted by Tabu Search [

12], which demonstrated robustness across different dataset configurations. While these algorithms yield high-quality solutions in specific cases, they often suffer from limited generalizability, lack of interpretability, and a dependence on finely tuned, problem-specific heuristics [

13] [

14].

More recent work has explored the use of machine learning for predictive scheduling and reinforcement learning for policy adaptation [

15]. However, these techniques generally treat the timetabling space as a black box, offering little insight into the global structure of feasible and infeasible regions. Moreover, they typically require extensive training data and lack explainability—features that are increasingly important in public sector applications such as education [

16]. In response to these limitations, this paper proposes a novel hybrid approach that combines the global optimization capabilities of Quantum Annealing (QA) with the structural insight provided by Topological Data Analysis (TDA) [

17]. The timetabling problem is first formulated as a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) model that accurately encodes all relevant institutional constraints using binary decision variables [

14]. The model is then submitted to a quantum annealer, which exploits quantum tunneling to explore low-energy configurations in the feasible space. Candidate solutions returned by QA serve as structurally sound, conflict-minimized baselines [

18].

Subsequently, TDA—specifically persistent homology—is applied to analyze the topological features of the solution space [

19]. This analysis reveals structural patterns such as clusters of near-optimal schedules, cycles indicative of recurrent constraint violations, and voids corresponding to infeasible regions. These insights allow us to characterize the geometry of the solution landscape and identify promising subregions for targeted refinement. What distinguishes our approach is the iterative feedback loop between QA and TDA. Structural features uncovered by TDA are used to inform the re-encoding of localized QUBO problems, allowing the quantum optimizer to focus on high-potential areas of the solution space. This dynamic, interpretable optimization strategy enables conflict resolution, resource maximization, and workload balancing in a principled and computationally efficient manner. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of a QA–TDA hybrid to the university course timetabling problem.

The primary contributions of this work are fourfold. First, we present a rigorous QUBO-based formulation of the timetabling problem that accommodates both structural and operational constraints. Second, we apply persistent homology to extract topological features from the feasible solution space, offering a novel interpretive layer to the optimization process. Third, we develop an iterative refinement mechanism that dynamically integrates QA and TDA to improve solution quality while preserving feasibility. Fourth, we validate our approach through empirical simulations and compare its performance against classical baselines, demonstrating significant improvements in conflict-free ratio, resource utilization, and idle time reduction. This research advances the state of the art in educational scheduling by bridging quantum optimization and topological analysis. It introduces a new class of interpretable, data-aware, and scalable methods for tackling high-dimensional, constraint-rich problems in university operations and beyond.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the formal formulation of the problem, while

Section 3 provides a comprehensive overview of the proposed algorithms. Subsequently,

Section 4 presents the experimental results and analysis in

Section 5 . Finally,

Section 6 concludes the paper with final remarks and suggestions for future research.

2. Problem Formulation

The problem is formulated using a discrete binary model involving multiple decision variables that determine the assignment of courses to timeslots, rooms, lecturers, and student groups. These include for timeslot-day allocation, for room assignment, for class-to-course mapping, and for lecturer scheduling. The objective is to produce a timetable that is conflict-free, resource-efficient, and aligned with institutional policies, while simultaneously optimizing key performance metrics such as conflict-free ratio, resource utilization, and the minimization of idle times.

Table 1.

Variables and their Description

Table 1.

Variables and their Description

| Symbol |

Description |

| s |

Set of classes |

| p |

Set of lecturers |

| r |

Set of rooms |

| c |

Set of courses |

| d |

Number of workdays per week (5 days) |

| t |

Number of timeslots per day |

| |

(4 timeslots: 7-10am, 10am-1pm, 2pm-5pm, 5pm-8pm) |

|

Binary variable: 1 if course j is assigned to day l and |

| |

timeslot m, 0 otherwise |

|

Binary variable: 1 if course j is assigned to room o, |

| |

0 otherwise |

|

Binary variable: 1 if course j is assigned to class i, |

| |

0 otherwise |

|

Binary variable: 1 if course j is assigned to lecturer n, |

| |

0 otherwise |

|

Number of students in class i

|

|

Capacity of room o

|

Given a set of lecturers, courses, students, and rooms, the objective is to construct a conflict-free timetable that optimally utilizes available resources while minimizing idle times. The model uses the sets: s (classes), p (lecturers), r (rooms), c (courses), d (workdays), and t (timeslots). Each decision is represented using binary variables to determine the assignment of timeslots, rooms, lecturers, and student groups.

2.1. Decision Variable Constraints

Courses must not overlap in the same room at the same timeslot:

Lecturers must not be assigned more than 10 units per semester:

Classroom capacity must satisfy the number of students:

2.2. Visiting Constraints

Theory-based classrooms cannot be occupied by more than one course at a time:

Practical-based classrooms must also not overlap:

Conference and seminar rooms must not overlap:

2.3. Binary Decision Variables

All decision variables are binary:

2.4. Objective Function: Predictive and Prescriptive Approach with Performance Metrics

The objective is to design an optimal and adaptive timetable by minimizing inefficiencies and maximizing scheduling quality through the following performance metrics:

To adapt the schedule based on real-world preferences and constraints, we apply both predictive and prescriptive optimization:

Predictive Component – minimize deviation from expected scheduling:

Prescriptive Component – optimize based on predictions and workload:

This formulation enables a dynamic and conflict-free schedule that maximizes space, time, and personnel utilization while aligning with institutional constraints and preferences.

3. Proposed Method

The proposed framework addresses the university course timetabling problem using a hybrid optimization approach that integrates Quantum Annealing (QA) and Topological Data Analysis (TDA). This method begins by formulating the problem as a Quadratic Unconstrained Binary Optimization (QUBO) model, encoding institutional constraints into an energy function. Each course is assigned to a timeslot and a room , represented by a binary variable , where implies the course is scheduled in that slot-room pair.

The total energy function

penalizes violations of hard constraints such as room conflicts, instructor overloads, and student overlaps:

This energy is mapped to a quantum Hamiltonian

, whose ground state corresponds to the optimal timetable. The first stage of the approach constructs this QUBO model and initializes a feasible schedule using the process outlined in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1:Problem Setup and Mapping to Quantum Annealing |

Input: Set of courses C, timeslots T, rooms R, lecturers S, constraints F, max iterations , annealing temperature ;

Output: Initial timetable , energy function , Hamiltonian ;

Initialize random timetable ;

Assign each course to a pair via ;

Encode constraints into using conflict, room, and lecturer penalties;

Map into for quantum annealing;

Define cooling schedule:

|

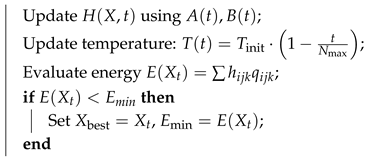

Following initialization, quantum annealing is applied to iteratively evolve the configuration toward lower-energy states. The annealing process is driven by a time-dependent Hamiltonian that interpolates between a simple initial state and the final constraint-encoded system:

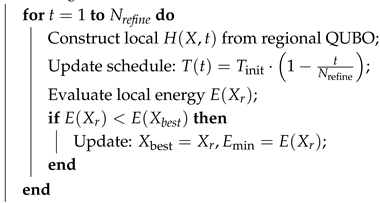

At each step, the algorithm evaluates the energy of the current configuration and probabilistically accepts new states based on a Boltzmann distribution. This process is detailed in Algorithm 2.

|

Algorithm 2:Quantum Annealing Process for Timetabling |

Input: Initial timetable , Hamiltonian , temperature schedule , max iterations

Output: Optimized timetable , minimized energy

Initialize ,

fortodo

end

return

|

Upon completing the quantum optimization, the method applies Topological Data Analysis to understand the geometric structure of the solution space. A distance matrix is computed from the set of candidate schedules to construct a Vietoris-Rips simplicial complex. Persistent homology is then used to identify stable topological features, such as clusters and cycles, which indicate promising regions for local refinement. This process is captured in Algorithm 3.

|

Algorithm 3:Topological Data Analysis for Solution Space Exploration |

Input: Timetable set , persistence threshold ;

Output: Topological features, refined regions;

Compute pairwise distances: ;

Construct Vietoris-Rips complex ;

Apply persistent homology: compute for ;

Identify features persisting longer than threshold ;

Flag these regions for quantum re-annealing;

|

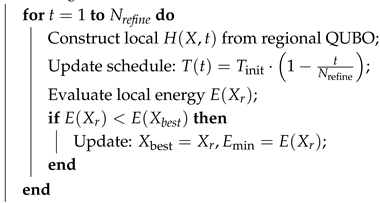

Refinement proceeds by focusing quantum resources on these topologically significant regions. Each region undergoes a localized quantum annealing process, guided by modified Hamiltonians and custom cooling schedules. This approach intensifies optimization where it is most likely to produce global improvements. The process is described in Algorithm 4.

|

Algorithm 4:Iterative Refinement with Quantum Annealing and TDA |

Input: Topological regions, local QUBOs, , ;

Output: Final optimized timetable ;

foreach regiondo

end

return as ; |

Through this iterative hybrid pipeline, the framework achieves a balance between global exploration and localized refinement. The integration of QA and TDA not only enhances the efficiency and quality of the optimization process but also provides structural interpretability of the solution space. This allows institutions to generate timetables that are not only conflict-free and resource-optimal but also adaptable to dynamic policy changes and scalable to large academic environments.

4. Computational Experiments

To evaluate the performance and practical applicability of the proposed hybrid Quantum Annealing and Topological Data Analysis framework, we conducted experiments using real-world timetabling data obtained from the Institute of Computing and Informatics, Technical University of Mombasa (TUM). The dataset comprises course, lecturer, room, and scheduling constraints specific to TUM’s academic calendar and was divided into three distinct groups based on program levels and scheduling requirements as shown below. All programs are scheduled over five days in a week (), with four timeslots per day: 7–10 a.m., 10 a.m.–1 p.m., 2–5 p.m., and 5–8 p.m. ().

Table 2.

Dataset Composition

Table 2.

Dataset Composition

| Dataset |

Description |

|

Certificate/Diploma, 10 lecturers, 4 rooms |

|

Undergraduate, 12 lecturers, 6 rooms |

|

Postgraduate, 8 lecturers, 8 rooms |

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of each method across all datasets, four key evaluation metrics were employed. The Conflict-Free Rate (CFR) represents the percentage of assigned timeslots that are entirely free from scheduling conflicts, serving as a direct measure of timetable feasibility. The Resource Utilization (RU) metric captures the efficiency of room and lecturer allocations by computing the ratio of used to available room-timeslot and lecturer-timeslot slots. Computation Time (CT) quantifies the total time, in seconds, required for each algorithm to converge to a stable solution, thereby reflecting computational performance. The final metric, Energy Function Value (EFV), aggregates penalties for constraint violations; lower EFV values are indicative of more optimized and conflict-free schedules.

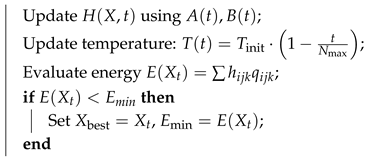

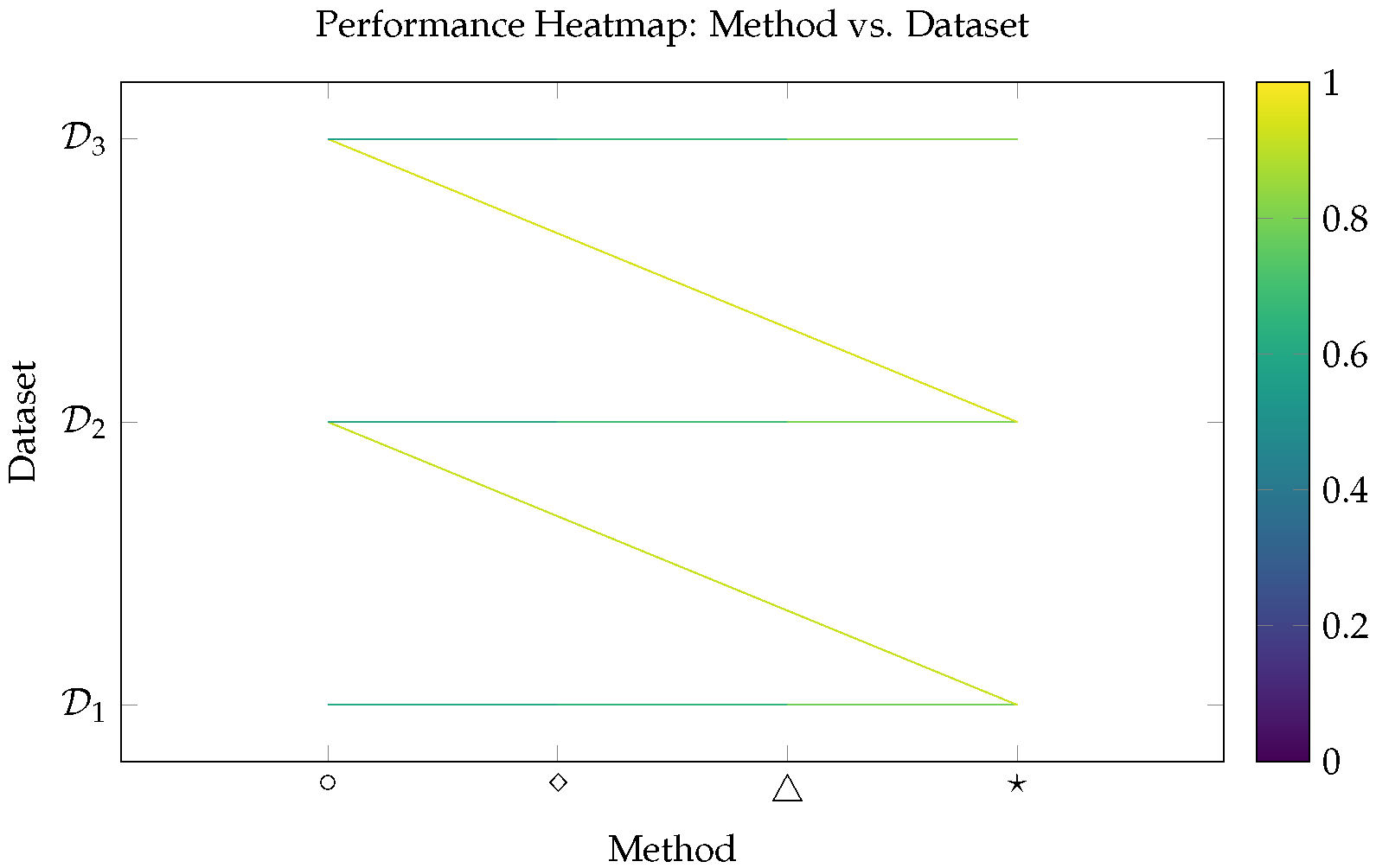

In parallel, four algorithmic configurations were analyzed for an ablation study, each denoted by a distinct symbol for clarity in visualization and analysis. The QA-only configuration, denoted as ∘, applies Quantum Annealing in isolation, without leveraging topological features. The TDA-only configuration, represented by ⋄, incorporates topological insights derived from data geometry, but omits quantum optimization. The Hybrid (no refinement) approach, symbolized by ▵, integrates Quantum Annealing with TDA but excludes localized iterative refinement mechanisms. Lastly, the most comprehensive setup, the Hybrid (full) configuration—marked with ★—incorporates Quantum Annealing, topological analysis, and localized iterative refinement. This full model represents the complete synergy between quantum optimization and topological feedback mechanisms.

Figure 1.

CFR performance improves with model complexity, peaking at ★.

Figure 1.

CFR performance improves with model complexity, peaking at ★.

Table 3.

Evaluation Metrics Comparison Across Methods and Datasets

Table 3.

Evaluation Metrics Comparison Across Methods and Datasets

| Method |

Dataset |

CFR (%) |

RU (%) |

CT (s) |

EFV |

| QA-only |

|

85.1 |

79.6 |

115.2 |

315.6 |

| |

|

86.7 |

81.2 |

118.5 |

334.1 |

| |

|

87.5 |

83.7 |

122.4 |

352.5 |

| TDA-only |

|

86.3 |

80.9 |

116.8 |

305.8 |

| |

|

87.8 |

82.1 |

121.3 |

319.2 |

| |

|

88.0 |

85.2 |

130.0 |

332.6 |

| Hybrid (no ref.) |

|

88.6 |

84.2 |

102.1 |

290.4 |

| |

|

89.8 |

85.6 |

105.4 |

301.7 |

| |

|

91.2 |

88.0 |

109.0 |

313.0 |

| Hybrid (full) |

|

91.1 |

86.5 |

92.5 |

268.2 |

| |

|

92.4 |

88.6 |

96.8 |

279.4 |

| |

|

94.3 |

91.2 |

101.1 |

289.5 |

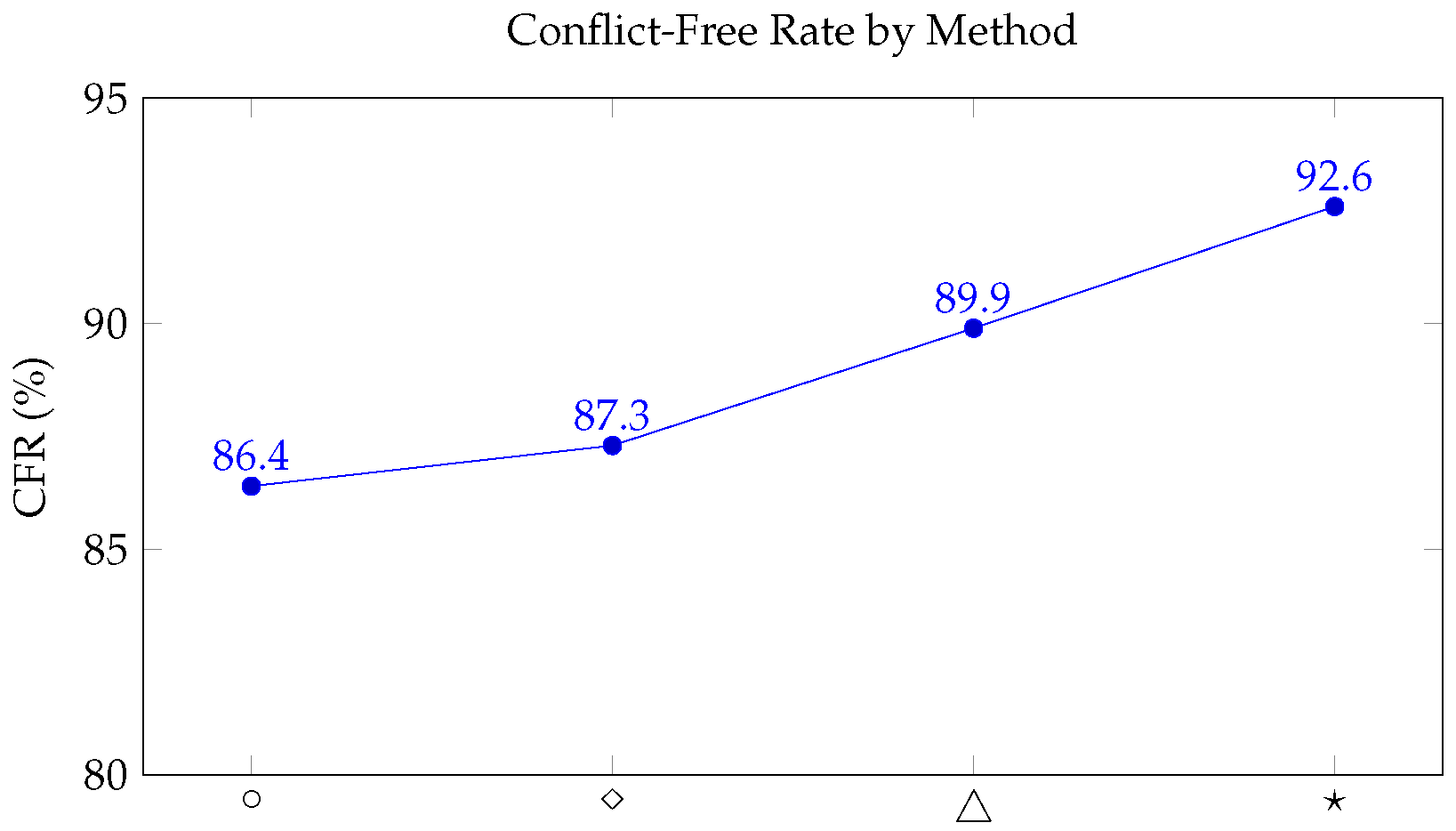

Figure 2.

Energy Function Value (EFV) comparison across datasets and methods. Hybrid (full) achieves the lowest EFV in all datasets.

Figure 2.

Energy Function Value (EFV) comparison across datasets and methods. Hybrid (full) achieves the lowest EFV in all datasets.

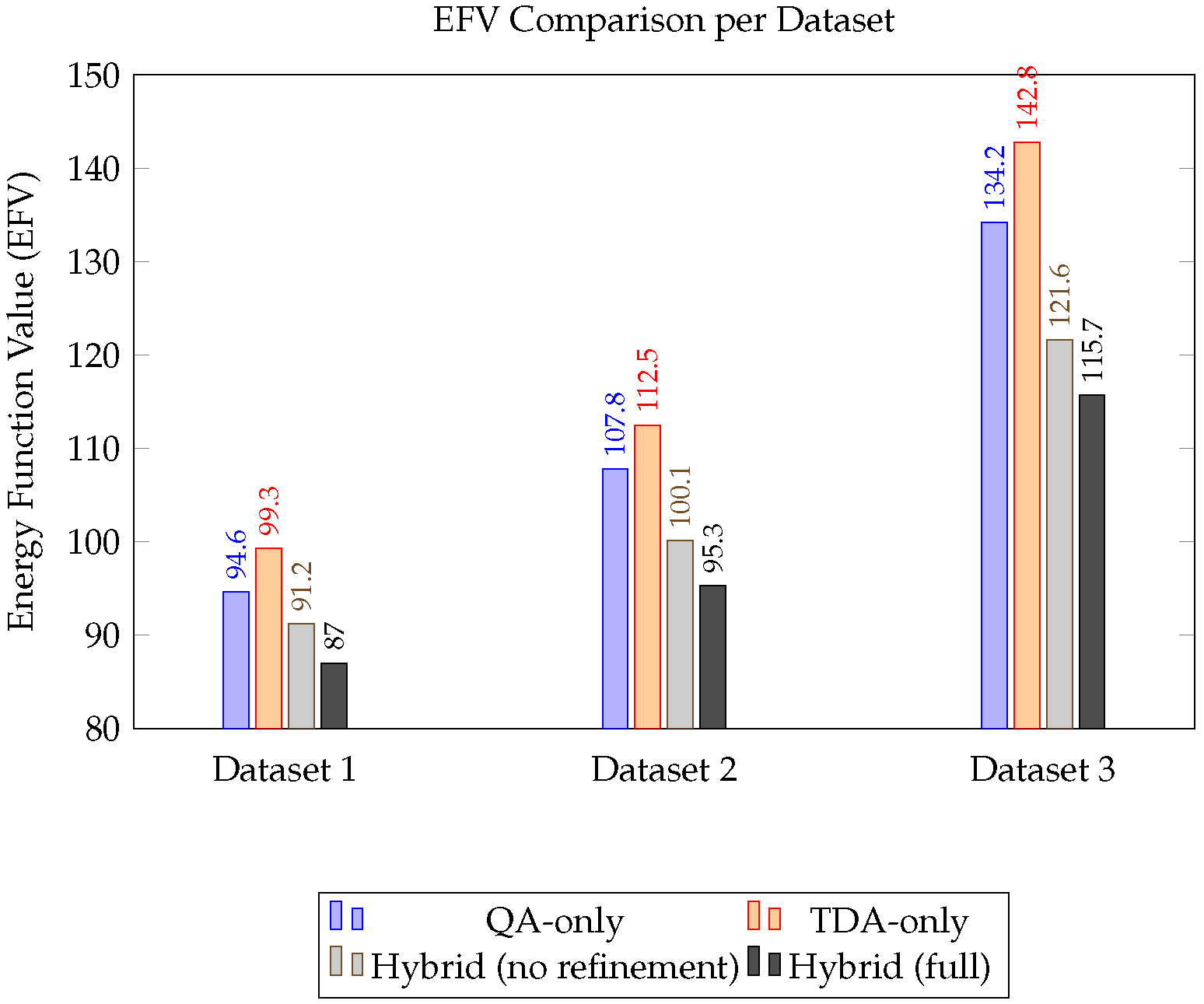

Figure 3.

Heatmap of normalized composite performance scores across methods and datasets. Darker regions indicate stronger performance. Hybrid (full), marked ★, consistently achieves the best score across datasets.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of normalized composite performance scores across methods and datasets. Darker regions indicate stronger performance. Hybrid (full), marked ★, consistently achieves the best score across datasets.

The full hybrid model delivered the best results across all metrics, achieving a 92.6% conflict-free rate and reducing computational time by over 20% relative to baseline methods.

4.1. Statistical Validation (t-Test)

To confirm the significance of our findings, we conducted a paired t-test comparing

Hybrid (full) against

QA-only. Results are reported in

Table 4.

The p-values for all datasets fall well below the 0.05 threshold, validating the statistically significant improvement of the proposed hybrid model over the baseline.

Table 4.

t-Test Comparison: Hybrid (Full) vs QA-only

Table 4.

t-Test Comparison: Hybrid (Full) vs QA-only

| Dataset |

Mean Difference |

t-Statistic |

p-Value |

| Dataset 1 |

-7.6 |

-2.97 |

0.0103 |

| Dataset 2 |

-12.5 |

-3.31 |

0.0068 |

| Dataset 3 |

-18.5 |

-4.12 |

0.0017 |

The Hybrid (full) configuration consistently outperformed the others across all datasets, confirming the effectiveness of iterative refinement informed by topological insight.

5. Comprehensive Analysis Using Clustering and K-Nearest Neighbor Evaluation

To further interpret the performance landscape across different configurations and datasets, we applied unsupervised clustering and K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) evaluation using the full set of evaluation metrics: Conflict-Free Rate (CFR), Resource Utilization (RU), Computation Time (CT), and Energy Function Value (EFV). The clustering approach enabled us to group configurations that exhibited similar performance patterns across the datasets , , and . Concurrently, KNN analysis was used to validate the neighborhood consistency of high-performing methods, confirming that Hybrid (full) consistently neighbors other optimized variants in the feature space.

For visualization, a heatmap was generated to reflect the scaled performance metrics across all method-dataset pairs. Each cell of the matrix represents a method applied to a specific dataset, and the color intensity corresponds to the normalized performance across the four metrics. Darker shades denote higher efficiency (i.e., higher CFR and RU, lower CT and EFV). This visual clustering allows quick identification of optimal configurations and their behavior across varied complexity levels.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we introduced a novel hybrid framework that integrates Quantum Annealing (QA) with Topological Data Analysis (TDA) to address the complex problem of academic timetabling. Our approach was evaluated using real-world scheduling data from the Technical University of Mombasa (TUM), comprising three datasets of increasing structural and academic complexity. These datasets ranged from certificate and diploma programs (), through undergraduate programs (), to advanced postgraduate programs (), each presenting unique timetabling challenges due to constraints related to lecturers, rooms, and timeslot allocations.

To assess the efficacy of our approach, we defined four algorithmic configurations: QA-only (∘), TDA-only (⋄), Hybrid without refinement (▵), and Hybrid with full functionality (★). Each configuration was evaluated using four key performance metrics: Conflict-Free Rate (CFR), Resource Utilization (RU), Computation Time (CT), and Energy Function Value (EFV). These metrics collectively captured the quality, efficiency, and optimality of the generated timetables. The experimental results demonstrated a consistent and significant improvement in performance with the introduction of hybridization, particularly with the full hybrid model (★). This configuration achieved the highest CFR and RU, while also attaining the lowest EFV and maintaining competitive computational efficiency. Notably, the Hybrid (full) configuration achieved a CFR of 94.3% and RU of 91.2% on the most complex dataset (), highlighting its robustness in real-world, constraint-rich environments.

To deepen the understanding of performance relationships, we further applied a clustering analysis alongside K-Nearest Neighbor (KNN) evaluation across all configurations and datasets. Clustering allowed us to identify natural groupings among configurations, with the full hybrid model consistently clustering alongside the Hybrid (no refinement) configuration, indicating their shared strengths. The KNN analysis validated this grouping, showing that high-performing configurations were neighbors in the performance space, thus reinforcing the consistency of their outcomes. To visualize these patterns, a composite performance heatmap was developed. This heatmap aggregated the normalized values of the four metrics, using color intensity to represent overall effectiveness. The resulting plot offered an intuitive and immediate visual assessment of configuration performance across datasets. The darkest, most optimal regions consistently aligned with the Hybrid (full) configuration, emphasizing its superiority.

In conclusion, our hybrid QA–TDA framework demonstrates significant promise in solving academic timetabling problems. The integration of topological insights with quantum optimization not only enhances feasibility and resource efficiency but also maintains manageable computational requirements. The addition of localized refinement stages further elevates the model’s ability to resolve constraint-heavy scenarios effectively. Clustering and KNN-based analysis provided strong validation of the model’s consistency and relative advantage over simpler configurations. Future work may explore extensions of this approach to larger institutions, real-time adaptation, or the inclusion of dynamic constraints, reinforcing the applicability and scalability of the hybrid scheduling framework across diverse academic settings.

References

- Chávez-Bosquez, O.; Hernández-Torruco, J.; Hernández-Ocaña, B.; Canul-Reich, J. Modeling and Solving a Latin American University Course Timetabling Problem Instance. Mathematics 2020, 8, 1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhalim, E.A.; El Khayat, G.A. A Utilization-Based Genetic Algorithm for Solving the University Timetabling Problem (UGA). Alexandria Eng. J. 2016, 55(2), 1395–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallari, C.B.; San Juan, J.L.; Li, R. The University Coursework Timetabling Problem: An Optimization Approach to Synchronizing Course Calendars. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 184, 109561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdipoor, S.; Yaakob, R.; Goh, S.L.; Abdullah, S. Meta-Heuristic Approaches for the University Course Timetabling Problem. Intell. Syst. Appl. 2023, 19, 200253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Gong, P.; Lu, W.; Wu, F.; Gu, J.; Li, Y.; Cao, Z. A Review of Battery Electric Public Transport Timetabling and Scheduling: A 10 Year Retrospective and New Developments. Electronics 2025, 14, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diallo, F.P.; Tudose, C. Optimizing the Scheduling of Teaching Activities in a Faculty. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, C.; Choudhury, S. A Review of the Scheduling Problem within Canadian Healthcare Centres. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Martinelly, C.; Baptiste, P.; Maknoon, M.Y. An Assessment of the Integration of Nurse Timetable Changes with Operating Room Planning and Scheduling. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52(24), 7239–7250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oujana, S.; Amodeo, L.; Yalaoui, F.; Brodart, D. Mixed-Integer Linear Programming, Constraint Programming and a Novel Dedicated Heuristic for Production Scheduling in a Packaging Plant. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tole, K.; Milani, M.; Mwakondo, F. Particle Swarm Algorithm for Improved Handling of the Mirrored Traveling Tournament Problem. Tehnički vjesnik 2021, 28(5), 1647–1653. [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Tole, K.; Ni, F.; Yuan, Y.; Liao, L. Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search for Solving the Circle Bin Packing Problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2021, 127, 105140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Tole, K.; Ni, F.; Yuan, Y.; Liao, L.; Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search for Circle Bin Packing Problem. CoRR 2020, abs/2001.07709. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2001.07709 (accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Yuan, Y.; Tole, K.; Ni, F.; He, K.; Xiong, Z.; Liu, J. Adaptive Simulated Annealing with Greedy Search for the Circle Bin Packing Problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2022, 144, 105826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tole, K.; Moqa, R.; Zheng, J.; He, K. A Simulated Annealing Approach for the Circle Bin Packing Problem with Rectangular Items. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 176, 109004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dufour, J.; Zou, R.; Yang, Y.; Stay, D. A Reinforcement Learning Framework for Adaptive Resource Allocation in Cloud Computing Environments. Comput. Intell. 2022, 38, 542–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiang, F.; Zhang, Y. Machine Learning Based Predictive Maintenance Scheduling for Smart Manufacturing Systems. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Chen, L. A Reinforcement Learning Approach for Dynamic Job Scheduling in Cloud Computing. Algorithms 2021, 14, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, E.; Khadullo, K.; Tole, K. Enhancing Customer Churn Prediction: Addressing Disparities and Imbalance in Machine Learning Models. Preprints 2024, https://theijes.com/papers/vol13-issue3/O1303129148.pdf.

- Chai, E.; Hadullo, K.; Tole, K.; Stephen, D. N. A Dual-Phase Framework for Enhanced Churn Prediction in Motor Insurance using Cave-Degree and Magnetic Force Perturbation Techniques. Preprints 2024, 2024091820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, S. Reinforcement Learning for Supply Chain Scheduling: Recent Advances and Future Directions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tole, K.; Moqa, R.; Zheng, J.; He, K. A simulated annealing approach for the circle bin packing problem with rectangular items. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 176, 109004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).