1. Introduction

Most forms of traditional medicine in East Asia derive from ideas of the anatomy and physiology of the body in classical Chinese medicine, developed at least as early as the second century BCE (Mitchell et al, 2000), but possibly much earlier, as indicated by excavations such as the Mawangdui tomb excavation, dating from 168 BCE (Harper, 1998). A central feature of this representation of the body is that communication pathways exist between specific areas of the surface of the body and corresponding internal parts of the body, including internal organs. Traditionally, these pathways are called meridians, an idea that has formed a major stumbling block to any integration of modern western and traditional eastern medical traditions.1 Yet, evidence for the existence of the meridians is necessary for any western-style scientific understanding of how treatments like acupuncture and massage may work causally. But western anatomical and physiological analysis failed to find channels that could explain such specific effects transmitted from surface stimulation to specific internal organs.

One of the last attempts to do so within the framework of macro-anatomy was made by a Korean scientist (see review by Lui et al, 2013)), known as the BongHan System, speculating that a third circulatory system exists in addition to the arteries and veins (Yamaoka, 2023). But, intriguing though the BongHan System is, it does not explain the specificity of communication: why should stimulation of a particular part of the body surface specifically affect particular tissues and organs far away from that area?

2. Fields and Hidden Micro-Level Processes

A standard way in which western science has sought to resolve this kind of issue is to suppose that hidden variables or fields of influence must exist. The invention of the idea of a magnetic field is an apposite example. Postulating that a field exists then enables action at a distance to become possible. This example led, in due course, to the development of the theory of electromagnetism, without which many important discoveries in physics could not be understood.

Although it has not been widely accepted by modern evolutionary biologists, there was also a similar development in biological science during the 19th century. The originator of the theory of Natural Selection, Charles Darwin, was convinced that, on its own, that theory could not explain the origin of species by a process of evolution. One of his reasons was that, even in his book The Origin of Species (Darwin, 1859), he outlined several examples which, in his view, required yet another form of action at a distance. He meant the acquisition of acquired characteristics by the progeny, an idea that was universally accepted in 18th/19th century biology, including notably by Lamarck (1809). This idea led Darwin to propose that there must be communication between the soma and the germline in order for those characteristics, acquired by the soma, to pass to the future eggs and sperm. Darwin was therefore faced with a similar dilemma: where were the relevant communication pathways?

He was therefore compelled to postulate action at a distance between the soma and the germline. In his 1868 book, The Domestication of Animals and Plants, he outlined his theory of pangenesis, according to which tiny particles, which he called gemmules, could communicate between soma cells and germline cells. He openly admitted that that there was, at that time, no experimental evidence for their existence. After Francis Galton (1871, see history in Liu 2008) performed blood transfusion experiments which failed to show the expected effects, Darwin’s pangenesis hypothesis was dropped.

3. Vesicles and Exosomes as Darwin’s Gemmules

Darwin’s problem was that 19th century light microscopy did not permit people to visualise what might correspond to his gemmules. That is one reason why his pangenetic idea fell unsupported by later evolutionary biologists, so his idea was ignored. August Weismann sealed the fate of the pangenesis theory with the invention of the Weismann Barrier idea in 1883 (Weismann, 1883).

The introduction of powerful electron microscopy in the 1940s transformed this situation by showing that many particles small enough to be beyond the resolution of the light microscope are found around cells. When first discovered around 30 years ago (Edelstein, et al, 2020) it was thought that this represented cell debris. In itself, this is not an implausible idea. The autophagy process in yeast, for example, consists in cell debris (degraded proteins and other non-functional macromolecules) being accumulated in a cell vacuole that eventually ferries the damaged molecules across the cell membrane to be recycled by the yeast colony (Ohsumi, 2018).

Using fluorescent microscopy to identify RNAs proteins and other molecules in the vesicular material led to a re-interpretation of cell ‘debris’. Extracellular vesicles have now been shown to communicate information from one population of cells in the body to cells in the same tissue but also to other populations, including notably from the soma cells to the germline cells (Smith & Spadafora, 2005; Spadafora, 2018; Noble, 2020, Phillips & Noble, 2024). This communication between the soma and the germline is similar to what Charles Darwin postulated in 1868 as his theory of pangenesis, which has now been vindicated by modern techniques identifying vesicles that can transmit control RNAs and transcription factors affecting expression of DNA in the germ cells (Phillips & Noble, 2024).

4. Vesicular Theory as the Basis of Meridians

This article develops a theory based on the idea that transmission via EVs and exosomes may also form the pathways of communication often called meridians in Chinese, Korean and Japanese and other East and South Asian medical treatments, including massage and acupuncture. Such a theory is needed, since no other pathways have been identified anatomically that could correspond to the meridians. The theory that extracellular vesicles may form such pathways is based on the facts that mechanical, electrical and heat stimuli readily cause cells to release EVs targeted at specific organs of the body. The theory is also open to experimental test. If the theory is correct, the postulated meridians could correspond to communication between cell populations that were close together in the embryo continuing to communicate when they are far apart in the adult. This would explain why stimuli to particular surface body regions can benefit the internal organs of the body.

We are not the first to highlight that extracellular vesicles may be the medium for the meridians. Several recent articles in journals of traditional alternative and complementary medicine (Li et al, 2020), and in western medical journals (Mo et al, 2022; Lyu et al 2023) have already done so. Those articles, and our own, reflect a topic of discussion that is frequently arising in conferences on traditional medicine. The reason is clear. The discovery of exosomes and EVs and their targeted functional roles has completely transformed discussion of the meridians. It is the clear function of these vesicle messengers from all cells in the body to communicate with other cells in the body. That already satisfies part of the presumed role of the meridians in traditional medicine, as we will show in a later section (see targeted nature of vesicular communication). As Lyu et al (2023) conclude “The emergence of exosomes seems to provide a feasible way to fully simulate the therapeutic effects of acupuncture, assuming that exosomes can become not only the transmitters during acupuncture treatment, but also carriers of needle-like effects at the end of an acupuncture intervention. Therefore, exosomes are very interesting and promising research components.”

However, this fact in itself, does not explain why particular regions of the surface of the body communicate specifically with particular internal parts of the body since it does not explain how those particular connections arose in the first place. The specificity exists, but how did it get established during development?

We propose that ‘development’ may be the key to an answer to this question. No internal organs of the body exist at the gastrulation stage of embryonic development. Those organs develop as the result of cellular migration from parts of the early ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm, the patterns of which are only partially clarified so far. The reason is that tracking migrating cells during development, or indeed during any other process, such as cancer metastasis, is extremely time-consuming using existing methods. Automated tracking methods are being introduced into developmental studies (Holme et al 2023) and it is to be hoped that such methods may enable the hypothesis we propose to be tested in future work.

Our hypothesis can be summarised as follows:

1.Vesicular communication is a key feature of multicellular development since it provides a process by which cells in the same tissue or region identify with and conform to the regulatory processes that must exist in multicellular organisms to enable them to develop. Those communication processes develop in the embryo.

2. It is then plausible that cells that developed such communication early in embryonic development may still possess those communication connections when they become far apart in embryonic development.

3.There is then no difficulty in understanding how surface therapeutic interventions may influence internal organs and systems. It would be a perfectly natural outcome of embryological development.

Our proposal also leads to a clear prediction: when we know more about cell migration in embryonic development the hypothesis predicts that the meridians may simply be the persistence of those communication memories. Thus, the liver originates from cells in the endoderm layer, one of the three germ layers formed early during gastrulation (Tremblay & Caret, 2005). So also do the thyroid and the pancreas. The nervous system develops from cells in the ectoderm which form the neural tube and neural crest. Germ cells also have specific origins in the early embryo before the cells migrate to form the adult germ cells.

5. Targeted Nature of Vesicular Communication

In contrast to the situation when EVs were first discovered using electron microscopy, and were regarded as cell debris, it is now well-established that many EVs are targeted at particular locations and functions. One of the authors of this article (DN) was a co-editor of a Clinical Compendium on exosomes (Edelstein et al, 2020) which includes articles across a wide range of clinical conditions in which vesicles have been shown to have functional targeting, ranging through various forms of cancer (Corbeil & Lorica, 2020; Raimondo et al, 2020, Urabe et al, 2020), bacterial infections (Cheng & Schorey, 2020), HIV-1 infection (Pang & Teow, 2020), parasitic diseases (Xander et al, 2020), cardiovascular diseases (Deftu et al. 2020), dermatological disease (McBride et al, 2020), nephrology (Hunter et al, 2020), neurodegenerative disorders (Mäger et al, 2020), fibrosis (Kadota, et al 2020), inflammation (Costantini et al, 2020), metabolic syndromes (Le hay et al, 2020), reproductive medicine (Nair & Salomon, 2020), respiratory disease (Alipoor & Mortaz, 2020), retinal disease (Webere at el, 2020), regenerative medicine (Zhou et al, 2020), in addition to basic biology (Conigliaro et al, 2020, Zhou et al, 2020, Noble, 2020).

In this section we have chosen to highlight the following articles for their novel insights. He et al. (2022) showed exosomal targeting and its potential clinical application. Under the action of a content sorting mechanism, some specific surface molecules can be expressed on the surface of exosomes, such as tetraspanins protein and integrin. To some extent, these specific surface molecules can fuse with specific cells, so that exosomes show specific cell natural targeting. Despite the promise of exosomes as drug delivery vehicles, challenges remain in harnessing their natural targeting capabilities. Optimizing exosomal targeting is essential for improving delivery specificity and developing more effective therapeutic strategies. He et al. (2022) highlights the inherent targeting ability of exosomes and summarizes current engineering approaches—such as surface modification with targeting peptides or proteins, and physical or chemical alterations—designed to enhance targeting efficiency. These advancements offer new directions for disease-specific treatments and broaden the potential for clinical translation.

Table 1.

Engineering exosomes as drug delivery systems reproduced from He et al 2022.

Table 1.

Engineering exosomes as drug delivery systems reproduced from He et al 2022.

| Targeting peptide/protein |

|

Receptor |

|

Targetcells/organ

|

Function |

Reference |

| IRGD peptide |

|

Lamp2b |

|

Breast cancer cell |

Targeting delivery of DOX and effectively inhibit tumor growth |

Tian et al 2014 |

| CSTSMLKAC peptide |

|

Lamp2b |

|

Ischemic myocardium |

Reduce inflammation, apoptosis and fibrosis, enhance angiogenesis, and cardiac function |

Wang et al 2018 |

| c (RgdyK) peptide |

|

Integrin ovß3 |

|

Ischemic brain injury area |

Targeting delivery of cur and inhibits the inflammatory response in lesion area |

Tian et al 2014 |

| RGE peptide |

|

Neurokinin- 1 |

|

Glioma |

Targeting delivery of cur |

Jia et al 2018 |

| c-Met binding peptide |

|

c-Met |

|

TNBC cells |

Targeting delivery of DOX |

Li et al 2020 |

| GEII peptide |

|

EGFR |

|

Breast cancer cell |

Targeting delivery of the tumor inhibitory miRNA |

Ohno et al 2013 |

| RVG peptide |

|

Lamp2b |

|

Brain neurons, microglia, and oligodendrocytes |

Targeting delivery of siRNA and knockdown of Alzheimer's disease related genes |

Alvarez-Erviti et al. 2011 |

| RVG peptide |

|

Acetylcholine receptor |

|

Neuron cell |

Targeting delivery opioid receptor mu siRNA to treat morphine addiction |

Liu et al 2025 |

| APo—A 1 |

|

SR-Bl receptor |

|

Liver cancer cells |

Targeting delivery Functional miR-26a |

Liang et al 2018 |

Hoshino et al., (2015) showed that tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis, and demonstrated that integrins on exosomes dictate their organotropic metastasis patterns. Exosomes from mouse and human lung-, liver- and brain-tropic tumour cells fuse preferentially with resident cells at their predicted destination, namely lung fibroblasts and epithelial cells, liver Kupffer cells and brain endothelial cells. Tumour-derived exosomes uptaken by organ-specific cells prepare the pre-metastatic niche. Treatment with exosomes from lung-tropic models redirected the metastasis of bone-tropic tumour cells.

Alvarez-Erviti et al (2011), showed delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes.

El-Andaloussi et al. (2012) showed exosome-mediated delivery of siRNA in vitro and in vivo. The use of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to induce gene silencing opens a new avenue in drug discovery. However, their therapeutic potential is hampered by inadequate tissue-specific delivery. Exosomes are promising tools for drug delivery across different biological barriers. They showed how exosomes derived from cultured cells can be harnessed for delivery of siRNA in vitro and in vivo. Alvarez-Erviti et al (2011), showed delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. El-Andaloussi et al. (2012) showed exosome-mediated delivery of siRNA in vitro and in vivo. The use of small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) to induce gene silencing opens a new avenue in drug discovery. However, their therapeutic potential is hampered by inadequate tissue-specific delivery. Exosomes are promising tools for drug delivery across different biological barriers. They showed how exosomes derived from cultured cells can be harnessed for delivery of siRNA in vitro and in vivo.

Urabe et al. (2021) showed that extracellular vesicles in the development of organ-specific metastasis. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are increasingly being demonstrated as critical mediators of bi-directional tumour-host cell interactions, controlling organ-specific infiltration, adaptation and colonization at the secondary site. EVs govern organotropic metastasis by modulating the pre-metastatic microenvironment through upregulation of pro-inflammatory gene expression and immunosuppressive cytokine secretion, induction of phenotype-specific differentiation and recruitment of specific stromal cell types.

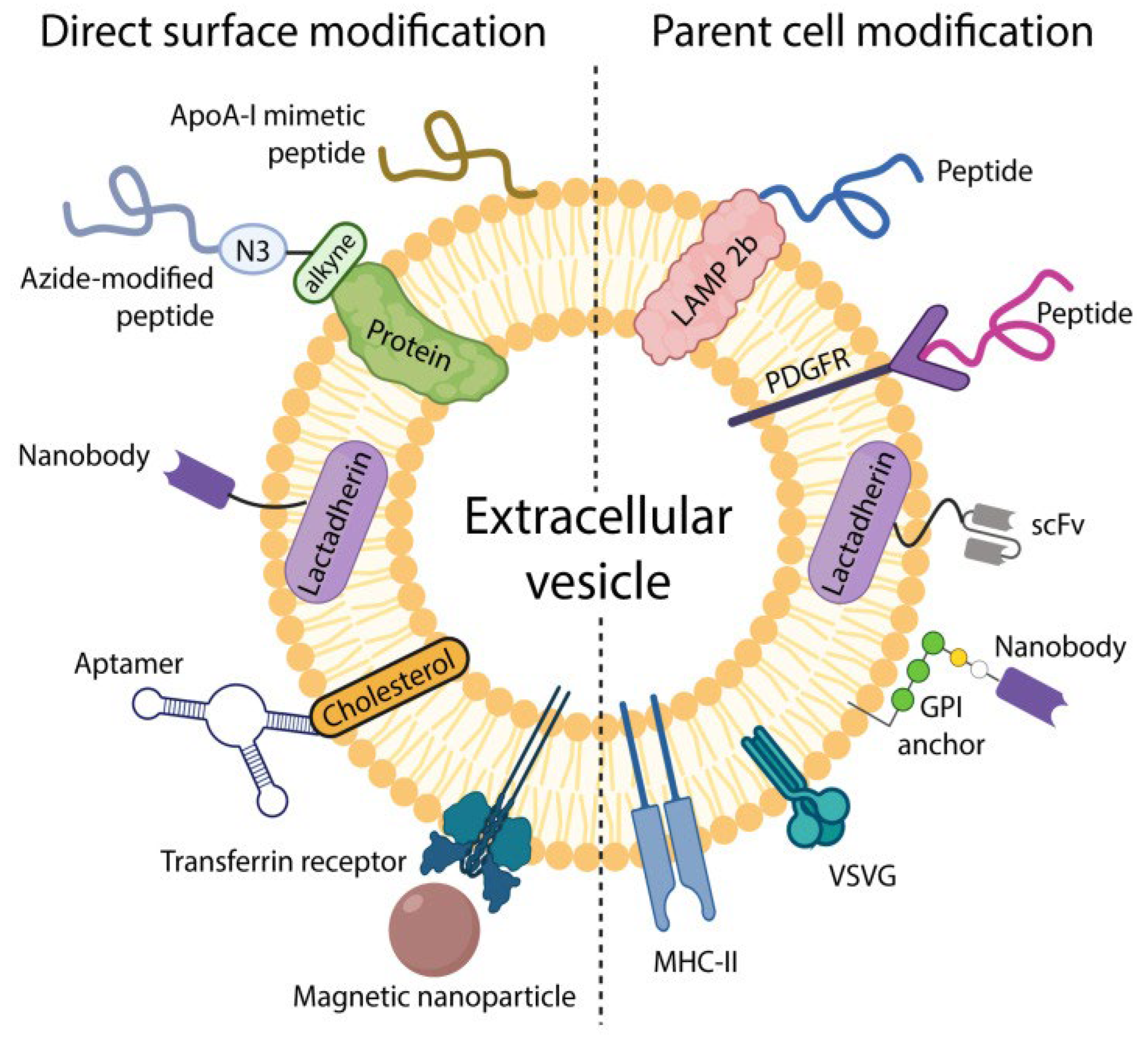

As described by Frolova and Li (2022), extracellular vesicles (EVs) can be functionalized with surface molecules to improve their targeting capabilities. This can be achieved either by directly attaching targeting ligands to the EV surface or by engineering the parent cells to express specific targeting moieties (see

Figure 1).

6. Molecular Composition and Targeting Mechanisms of Extracellular Vesicles

In this section we provide more details and references on how EVs play their pivotal role in intercellular communication by transporting a diverse array of lipoids, proteins, nucleic acids and signalling molecules to the recipient cells (Dixson et al, 2023; Kumari et al, 2021; Momen-Heravi et al, 2013; Salmond & Williams, 2021). They are released under a wide variety of physiological and pathological conditions and the heterogeneity of EVs, stemming from their diverse cellular origins and biogenesis pathways, contributes to their functional versatility, enabling them to mediate a wide range of biological processes, including immune responses, tissue repair, and disease progression (Gangadaran et al, 2022; Liu & Wang, 2023; Nail et al, 2023). The inherent targeting ability of exosomes stems from specific surface molecules, such as tetraspanins and integrins, that facilitate their interaction with recipient cells (He et al., 2022).

The precise molecular cargo reflects the physiological state of the originating cell, in turn depending on the cell type, its activation status and therefore on environmental cues (Yoshikawa et 2019). MicroRNAs (miRNAs), short non-coding RNA molecules, are selectively sorted into EVs and delivered to recipient cells, where they regulate gene expression by binding to complementary sequences in the 3' untranslated region of target mRNAs, thereby modulating cellular functions and responses (Dellar et al., 2024).

The targeting mechanisms of EVs involve a complex interplay of surface molecules, receptor-ligand interactions, and environmental cues that guide EVs to specific recipient cells. EV surface proteins, such as integrins, tetraspanins, and selectins, mediate interactions with complementary receptors on target cells, facilitating EV binding, internalization, and cargo delivery. The lipid composition of EV membranes, including the presence of specific gangliosides and phospholipids, also influences their targeting properties, modulating interactions with target cell membranes and promoting membrane fusion. Glycans, sugar molecules attached to proteins and lipids on the EV surface, contribute to EV targeting by interacting with lectins and other glycan-binding proteins on target cells. The cellular environment, encompassing factors such as temperature, pH, and extracellular matrix components, also influences EV targeting, with gradients of morphogens acting as source-sink mechanisms guiding EVs to specific locations. The specificity of EV targeting is further influenced by the expression of adhesion molecules related to the progenitor cell, enabling EVs to preferentially target certain receptor cells (Liu & Wang, 2023). Tetraspanins, which are enriched in exosomes, contribute to target cell selection because of the selective binding interactions between EVs and cells (Liu & Wang, 2023).

The cellular environment of EVs, which includes temperature, pH, and extracellular matrix components, also plays a role in EV targeting. The rational design of targeting ligands requires a comprehensive understanding of the molecular landscape of target cells and the corresponding ligands that mediate specific interactions. Moreover, the characteristics of EVs can also be influenced by the state of the cells that secrete exosomes, which further influence cellular binding and uptake (Liu & Wang, 2023).

Esmaeili et al (2022) highlight the inherent targeting ability of exosomes and summarize current engineering approaches—such as surface modification with targeting peptides or proteins, and physical or chemical alterations—designed to enhance targeting efficiency (He et al., 2022).

In conclusion, the uptake of EVs by target cells occurs through several mechanisms, including endocytosis, direct fusion with the plasma membrane, and receptor-mediated signaling, with the predominant mechanism depending on the EV type, target cell type, and environmental conditions. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis, caveolin-mediated endocytosis, and lipid raft-mediated endocytosis are the major endocytic pathways involved in EV uptake, with each pathway characterized by distinct protein machinery and membrane invagination mechanisms. Direct fusion of EVs with the plasma membrane allows for rapid delivery of EV contents into the cytoplasm of target cells, so bypassing the need for endosomal trafficking and processing.

With regard to the hypothesis that EVs may form the communication system needed to understand the causal basis of traditional treatments, such as massage and acupuncture, understanding the molecular basis of specific targeting of EV communication between cells and parts of the body provides a crucial piece of evidence.

7. Therapeutic Potential and Use as Markers of Disease States

Understanding the molecular composition of EVs and the mechanisms governing their targeting to specific recipient cells is crucial for harnessing their therapeutic potential (Liu & Wang, 2023), but realizing their full therapeutic potential requires refining their inherent targeting capabilities (Liang et al., 2021). The identification and characterization of EV-associated molecules hold great promise for biomarker discovery, enabling the development of non-invasive diagnostic tools for various diseases (Hernández et al., 2020). Furthermore, therapeutic agents, including chemotherapeutic drugs and neuroprotective agents, can be encapsulated within EVs, enabling targeted delivery to specific cells or tissues and minimizing systemic toxicity (Liu & Wang, 2023). EVs can also be engineered to deliver therapeutic agents for neurological disorders, and can be loaded with molecules like miR-193b, which is associated with amyloid precursor protein expression, showing promise for Alzheimer's disease therapy and biomarker development (Davidson et al., 2022; Liu & Wang, 2023).

However, the native targeting of exosomes might be insufficient for precise drug delivery to specific cells or tissues. Off-target effects can arise due to the varied biological distribution and accumulation of exosomes derived from different cells (He et al., 2022). Therefore, optimizing exosomal targeting is essential for improving delivery specificity and efficacy. Challenges remain in harnessing the natural targeting capabilities of EVs. Since the specificity of exosomal targeting is determined by the interactions between ligands on the exosome surface and receptors on the target cell membrane (Liu & Wang, 2023) engineering the exosome surface with specific targeting ligands, may succeed in directing exosomes to specific cell types or tissues (He et al., 2022).

The use of antibody fragments specific for epitopes displayed on target cells is a common strategy for targeting nanoparticle drugs and is currently being evaluated in a variety of clinical trials (Marcus & Leonard, 2013). Clinical trials are also underway on the therapeutic efficacy of exosomes as such (Cheng et al, 2017). Exosomes derived from human embryonic kidney cells are immunologically inert, therefore without safety concerns, and they have high transfection efficiency, and can deliver drugs to various target tissues (Dai et al., 2022).

Various engineering strategies have been developed to augment exosomal targeting, which includes surface modification with targeting ligands, genetic engineering of exosomal producing cells, and physical or chemical alterations. Surface modification involves conjugating targeting moieties, such as peptides, antibodies, or aptamers, to the exosomal membrane. These modifications facilitate the targeted delivery of therapeutic payloads to specific cells or tissues, enhancing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects (He et al., 2022). Genetic engineering enables the manipulation of exosomal composition and function by modifying the exosomal producing cells. This involves fusing ligands or homing peptides with transmembrane proteins expressed on the surface of exosomes (Liu & Wang, 2023). Physical and chemical alterations, such as sonication, electroporation, and click chemistry, can also be employed to enhance exosomal targeting. These methods facilitate the encapsulation of therapeutic agents into exosomes and improve their targeting efficiency (Xu et al., 2020; Yong et al., 2019). Furthermore, maintaining the structural integrity of exosomes during modification processes is essential for preserving their functionality (Johnsen et al., 2016).

We conclude that EVs are, in themselves, promising vehicles for the development of specific therapies.

8. Resurrection of Darwin’s Pangenesis Theory

Despite Galton’s 1871 experiments showing no evidence for pangenesis, Darwin never wavered in his belief that all cells of the body “throw off” minute particles that may be transmitted to other parts of the body. For a whole decade before he died in 1882, he engaged with a young physiologist, George Romanes, to carry out grafting experiments in plants in his attempts to prove his case. Much of that work was subsequently referred to by Romanes in his 3 volume 1893 publication, Darwin and After Darwin (Romanes, 1893).

But, no further experiments on Darwin’s theory were carried out until the 1950s, when a number of Russian scientists performed transfusion experiments on poultry and rabbits showing evidence that the idea was correct. Liu has analysed more than 50 papers published on these experiments and concludes that 45 gave positive results (see Liu 2008 for references and further explanation). Even before the proposal that EVs might be the missing process in pangenesis, Liu concluded that “Darwin’s Pangenesis contains a great truth and needs to be reconsidered” (Liu, 2008 p. 149).

Since Liu’s careful historical work the evidence that transmission of nucleotides, proteins and metabolites can pass from the soma to the germline has become very strong. An article entitled “Bubbling Beyond the Barrier”, co-authored by one of us (Phillips & Noble, 2024), has around 150 references to experiments showing how widespread the phenomenon is. Their conclusion is that “the idea that so many cases of GEI [germline epigenetic inheritance] are expected to change an animal’s evolutionary fitness is re-igniting the historical debate between Larmarckian and Neo-Darwinian evolution.” (Phillips & Noble, 2024, p 10).

Time and again, advances in experimental methods enabling scientists to visualise objects and processes previously beyond the resolution of previous methods shows that “progress is often achieved by a ‘criticism from the past’ ….Theories are abandoned and superseded by more fashionable accounts long before they have had an opportunity to show their virtues.” (Feyerabend, 1993, p. 59).

9. Conclusions

The discovery of exosomes and other forms of extracellular vesicles transforms the theory of meridians in the various forms of Asian traditional medicine. There is no longer a conflict between western and eastern interpretations of the anatomy of the body. Furthermore, the specificity assumed in traditional medicine could in consequence be susceptible to standard scientific interpretations of the causality involved.

The same comment from Feyerabend in the previous section applies to the meridians of Asian Traditional Medicine. With the discovery of the targeted functionality of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles a complete system of ancient medical treatment comes within reach of the methods of modern medical science.

Concerning the wired pathway, which the BongHan System claimed, it does not need to be fully identified as an additional circulatory system. The question is rather how versatile our living systems are. The extracellular vesicle pathway works for a general signalling mechanism. But there is nothing to prevent that system using standard anatomical vessels. The specificity need not lie in the pathway but rather in what is transported, the targeted vesicle.

We conclude that vesicular communication can not only provide a process for the long-postulated meridians, but also an explanation for the specificity of the targeting, which may arise naturally during embryonic development. The meridians may then follow the pathways of embryonic cell migration.

Authorship

All authors contributed to the conceptualization and writing.

Funding

No funding supported this project.

Acknowledgments

We thank Reine Bourret for many valuable comments on this article. We thank therapists Linda Nuttall, Chris Thurgar and Zhidao Xia for practical experience.

References

- Alipoor, S.D. & Mortaz, E. 2020. Exosomes in respiratory disease. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp. 383-414. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Erviti1, L., Seow, Y., Yin, H.F., Betts, C., Lakhal, S., 1 & Wood, M.J.A. 2011, Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes, Nature Biotechnology, 29. https://www.nature.com/articles/nbt.1807.

- Cheng, L. , Zhang, K., Wu, S., Cui, M., & Xu, T. (2017). Focus on Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes: Opportunities and Challenges in Cell-Free Therapy. Stem Cells International. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y. & Schorey, J.S. 2020. The function and therapeutic use of exosomes in bacterial infections.

- In Edelstein, L.R.; et al. (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp. 123-146. [CrossRef]

- Conigliaro, A. , Corrado, C., Fontana, S., Alessandro, R. 2020. Exosomes basic mechanisms. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Constantini, T.W. , Coimbra, R., & Eliceiri, B.P. 2020. Mechanisms of exosome-mediated immune cell crosstalk in inflammation and disease. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 325-342. [CrossRef]

- Corbell, D. , Lorico, A. 2020. Exosomes, micro vesicles and their friends in solid tumors. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 39-80. [CrossRef]

- Dai, X. , Ye, Y., & He, F. 2022. Emerging innovations on exosome-based onco-therapeutics [Review of Emerging innovations on exosome-based onco-therapeutics]. Frontiers in Immunology. [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. 1859. On the Origin of Species. London: Murray.

- Darwin, C. 1868. The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication. London: Murray.

- Davidson, S. M. , Boulanger, C. M., Aïkawa, E., Badimón, L., Barile, L., Binder, C. J., Brisson, A., Buzás, E. I., Emanueli, C., Jansen, F., Katsur, M., Lacroix, R., Lim, S. K., Mackman, N., Mayr, M., Menasché, P., Nieuwland, R., Sahoo, S., Takov, K., … Sluijter, J. P. G. 2022. Methods for the identification and characterization of extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular studies: from exosomes to microvesicles. Cardiovascular Research. [CrossRef]

- Deftu, A.T. , Radu, B-M., Cretoiu, D., Deftu, A.F., Cretoiu, S.M. & Xiao, J. 2020. Exosomes as intercellular communication messengers for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 199-238. [CrossRef]

- Dellar, E. R. , Hill, C., Carter, D. R. F., & Baena-López, L. A. 2024. Oxidative stress-induced changes in the transcriptomic profile of extracellular vesicles. Journal of Extracellular Biology. [CrossRef]

- Dixson, A. C. , Dawson, T. R., Vizio, D. D., & Weaver, A. M. 2023. Context-specific regulation of extracellular vesicle biogenesis and cargo selection. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. [CrossRef]

- Edelstein, L.R., Smithies, J.R., Quesenberry, P.J. & Noble, D. (Eds) 2019 Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-816053-4.

- El-Andaloussi, S. , et al. 2012. Exosome-mediated delivery of siRNA in vitro and in vivo. Nature Protocols. 7. https://www.nature.com/doifinder/10.1038/nprot.2012.131.

- Esmaeili, A. , Alini, M., Eslaminejad, M. B., & Hosseini, S. (2022). Engineering strategies for customizing extracellular vesicle uptake in a therapeutic context. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Feyerabend, P. 1993. Again Method: Outline of an anarchistic theory of knowledge. Verso.

- Frolova and Li (2022), Targeting Capabilities of Native and Bioengineered Extracellular Vesicles for Drug Delivery. Bioengineering, 9, 496. [CrossRef]

- Galton, F. 1871. Experiments in Pangenesis, by breeding from rabbits of a pure variety, into whose circulation blood takenfrom other varieties had previously been largely transfused. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 19, 393–410.

- Gangadaran, P. , Gunassekaran, G. R., Rajendran, R. L., Oh, J. M., Vadevoo, S. M. P., Lee, H., Hong, C. M., Lee, B.-H., Lee, J., & Ahn, B. (2022). Interleukin-4 Receptor Targeting Peptide Decorated Extracellular Vesicles as a Platform for In Vivo Drug Delivery to Thyroid Cancer. Biomedicines. [CrossRef]

- Harper, D. 1998. Early Chinese Medical Literature. The Wawangdui Medical Manuscripts. London and New York: Kegan Paul International.

- He, J. , Ren, W., Wang, W., Jiang, L, Zhang, D., & Gut, M. 2022. Exosomal targeting and its potential clinical application. Drug Deliv Transl Res. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, A. , Arab, J. P., Reyes, D., Lapitz, A., Moshage, H., Bañales, J. M., & Arrese, M. (2020). Extracellular Vesicles in NAFLD/ALD: From Pathobiology to Therapy. Cells. [CrossRef]

- Holme, B. , Bjørnerud, B., Pedersen, N.M. et al. 2023. Automated tracking of cell migration in phase contrast images with CellTraxx. Scientific Reports. [CrossRef]

- Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, et al. 2015. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 527(7578):329-35. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunter, R.W. , Dear, J.W.. & Bailey, M.A. 2020. Exosomes in nephrology. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 257-283. [CrossRef]

- Jia G, Han Y, An Y, et al. 2018. NRP-1 targeted and cargo-loaded exosomes facilitate simultaneous imaging and therapy of glioma in vitro and in vivo. Biomaterials, 178, 302–316. [CrossRef]

- Kadota, T. , Kosaka, N., Fujita, J., Kuwana, K., Ochiya, T. 2020. Extracellular vesicles in fibrotic diseases: New applications for fibrosis diagnosis and treatment. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 307-323. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J-S. 2020. The potential of exosomes as theragnostics in various clinical situations. n Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp. 467-486. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, P. V. K. , Srilekhya, K., Sindhu, K. B., & Rao, Y. S. 2021. Exosome nanocarriers: Basic biology, diagnosis, novel perspective approach in drug delivery systems: A Review. International Journal of Applied Pharmaceutics. [CrossRef]

- Lamarck, J-B. 1809. Philosophie Zoologique. Paris: Flammarion.

- Le Lay, S. , Andriantsitohaina, R., Martiinez, M.C. 2020. Exosomes in metabolic syndrome. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp. 343-356. [CrossRef]

- Liang G, Kan S, Zhu Y, et al. 2018. Engineered exosome mediated delivery of functionally active miR-26a and its enhanced suppression effect in HepG2 cells. Int J Nanomed, 13, 585–99. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y. , Duan, L., Lu, J., & Xia, J. 2021. Engineering exosomes for targeted drug delivery [Review of Engineering exosomes for targeted drug delivery]. Theranostics, 11(7), 3183. Ivyspring International Publisher. [CrossRef]

- Li NC, Li MY, Lu ZX, Li MY, Zhuo XM, Chen Y, et al. 2020. Exosome is an important novel way of acupuncture information transmission. World J Tradit Chin Med. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Wu Y, Ding F, et al. 2020. Engineering macrophage-derived exosomes for targeted chemotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer. Nanoscale, 12, 10854–10862.

- Liu, J.L. , Jing, X-H, Shi, H., Chen, S-P, Bai, W-Z, Zhu, B. 2013. Historical Review about research on “Bonghan System” in China. Evidence-based Complementary & Alternative Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. 2008. A new perspective on Darwin’’s Pangenesis. Biological Reviews. 83, 141-149. PMID: 18429766. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Li D, Liu Z, et al. 2015. Targeted exosome-mediated delivery of opioid receptor Mu siRNA for the treatment of morphine relapse. Sci Rep, 5:17543. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. , & Wang, C. (2023). A review of the regulatory mechanisms of extracellular vesicles-mediated intercellular communication. Cell Communication and Signaling, 21(1). BioMed Central. [CrossRef]

- Lyu Q, Zhou X, Shi L-Q, Chen H-Y, Lu M, Ma X-D and Ren L (2023) Exosomes may be the carrier of acupuncture treatment for major depressive disorder. Front. Behav. Neurosci. [CrossRef]

- Marcus, M. , & Leonard, J. N. (2013). FedExosomes: Engineering Therapeutic Biological Nanoparticles that Truly Deliver. Pharmaceuticals. [CrossRef]

- Mäger, I. , Willms, E., Bonner, S., Hill, A.F., Wood, M.J.A. 2020. Extracellular vesicles in neurodegenerative disorders. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 285-305. [CrossRef]

- McBride, J.D. , Aickara, D., & Badiavas, E. 2020. Exosomes in cutaneous biology and dermatologic disease. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 239-255. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C., Ye, F. & Wiseman. N. (Eds) 2000. Shang Han Lun: On Cold Damage. London: Churchill Livingstone.

- Mo C, Zhao J, Liang J, Wang H, Chen Y and Huang G (2022), Exosomes: A novel insight into traditional Chinese medicine. Front. Pharmacol. [CrossRef]

- Momen-Heravi, F. , Balaj, L., Alian, S., Mantel, P., Halleck, A. E., Trachtenberg, A. J., Soria, C. E., Oquin, S., Bonebreak, C. M., Saracoglu, E., Skog, J., & Kuo, W. P. (2013). Current methods for the isolation of extracellular vesicles. Biological Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Nail, H. M. , Chiu, C., Leung, C., Ahmed, M. M. M., & Wang, H. (2023). Exosomal miRNA-mediated intercellular communications and immunomodulatory effects in tumor microenvironments [Review of Exosomal miRNA-mediated intercellular communications and immunomodulatory effects in tumor microenvironments]. Journal of Biomedical Science. [CrossRef]

- Nair, S. , Salomon, C. 2020. Potential role of exosomes in reroductive medicine and pregnancy. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 357-381. [CrossRef]

- Noble, D. 2020. Exosomes, gemmules, pangenesis and Darwin. In: Edelsteien et al (Eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 487-501. [CrossRef]

- Ohno S, Takanashi M, Sudo K, et al. 2013. Systemically injected exosomes targeted to EGFR deliver antitumor microRNA to breast cancer cells. Mol Ther, 21, 185–191. [CrossRef]

- Ohsumi, Y. 2016. Nobel Lecture: Autophagy – an Intracellular Recycling System". Nobel Prize. December 7, 2016.

- Pang, S-W., Teow, S-Y. 2020. Emerging therapeutic roles of exosomes in HIV-1 infection. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 147-178. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D. & Noble, D. 2024. Bubbling Beyond the Barrier: exosomal RNA as a vehicle for soma-germline communication. Journal of Physiology. [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, S. , Sapeva, L., Alessandro, R. 2020. Hematologic malignancies: The exosome contribution in tumor progression. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 81-100. [CrossRef]

- Romanes, G. 1893. Darwin and After Darwin. Cambridge: CUP.

- Salmond, N. , & Williams, K. C. (2021). Isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicles for clinical applications in cancer – time for standardization? Nanoscale Advances. [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. & Spadafora, C. 2005. Sperm-mediated gene transfer: applications and implications. Bioessays. [CrossRef]

- Soh, K.-S. 2005. Review on recent Korean works on Bonghan system. International Journal of Society of Life Information. [CrossRef]

- Soh, K.-S. 2013. 50 years of Bong-Han theory and 10 years of primo vascular system. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Spadafora, C. 2018. The “evolutionary field” hypothesis.Non-Mendelian trangenerational inheritance mediates diversification and evolution. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. [CrossRef]

- Tian Y, Li S, Song J, et al. 2014. A doxorubicin delivery platform using engineered natural membrane vesicle exosomes for targeted tumor therapy. Biomaterials, 35, 2383–2390. [CrossRef]

- Tian T, Zhang H, He C, et al. 2018. Surface functionalized exosomes as targeted drug delivery vehicles for cerebral ischemia therapy. Biomaterials, 150, 137–149. [CrossRef]

- Tickner, J. A. , Urquhart, A., Stephenson, S., Richard, D. J., & Oâ€TMByrne, K. J. (2014). Functions and Therapeutic Roles of Exosomes in Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology, 4. Frontiers Media. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, K. D, Zaret K.S. 2005. Distinct populations of endoderm cells converge to generate the embryonic liver bud and ventral foregut tissues. Dev Biol. [CrossRef]

- Urabe, F.; et al. 2021. Extracellular vesicles in the development of organ-specific metastasis, J Extracell Vesicles. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8287318/.

- Urabe, F. , Osaka, N., Asano, K., Agawa, S., Ochiya, T. 2020. Physiological and pathological functions of prostasomes: From basic research to clinical application. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 101-121. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Chen Y, Zhao Z, et al. 2018. Engineered exosomes with ischemic myocardium-targeting peptide for targeted therapy in myocardial infarction. J Am Heart Assoc, 7:e008737. [CrossRef]

- Weber, S.R. , Zhou, M., Zhao, Y., Sundstrom, J.M. 2020. Exosomes in retinal diseases. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp. 415-431. [CrossRef]

- Weismann, A. Die Allmacht der Naturzuchtung: eine Erwiderung an Herbert Spencer. Jena: Fischer. Translated and published in 1893 as “The All-sufficiency of natural selection. A reply to Herbert Spencer. Contemporary Review. 1893, 64, 309–338. [Google Scholar]

- Xander, P. , Cronemberger-Andrade. A., Torrecilhas, A.C. 2020. Extracellular vesicles in parasitic disease. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 1790198. [CrossRef]

- Yamaoka, D. 2023. Comments on Professor Denis Noble’s OPINION article in the Journal of Physiology. Journal of Physiology. [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, F. S. Y. , Teixeira, F. M. E., Sato, M. N., & Oliveira, L. M. da S. (2019). Delivery of microRNAs by Extracellular Vesicles in Viral Infections: Could the News be Packaged? Cells. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N. , Weber, S.R., Zhao, Y., Chen, H., Sundstrom, J.M. 2020. Methods for exosome isolation and characterization. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp 23-38. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z. , Osaka, N., Xiao, Z., Ochiya, T. 2020. MSC-exosomes in regenerative medicine. In Edelstein, L.R. et al (eds) Exosomes: A Clinical Compendium, Academic Press, pp. 433-465. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).