2.1. A Multidimensional Framework of Nanostores’ Identity

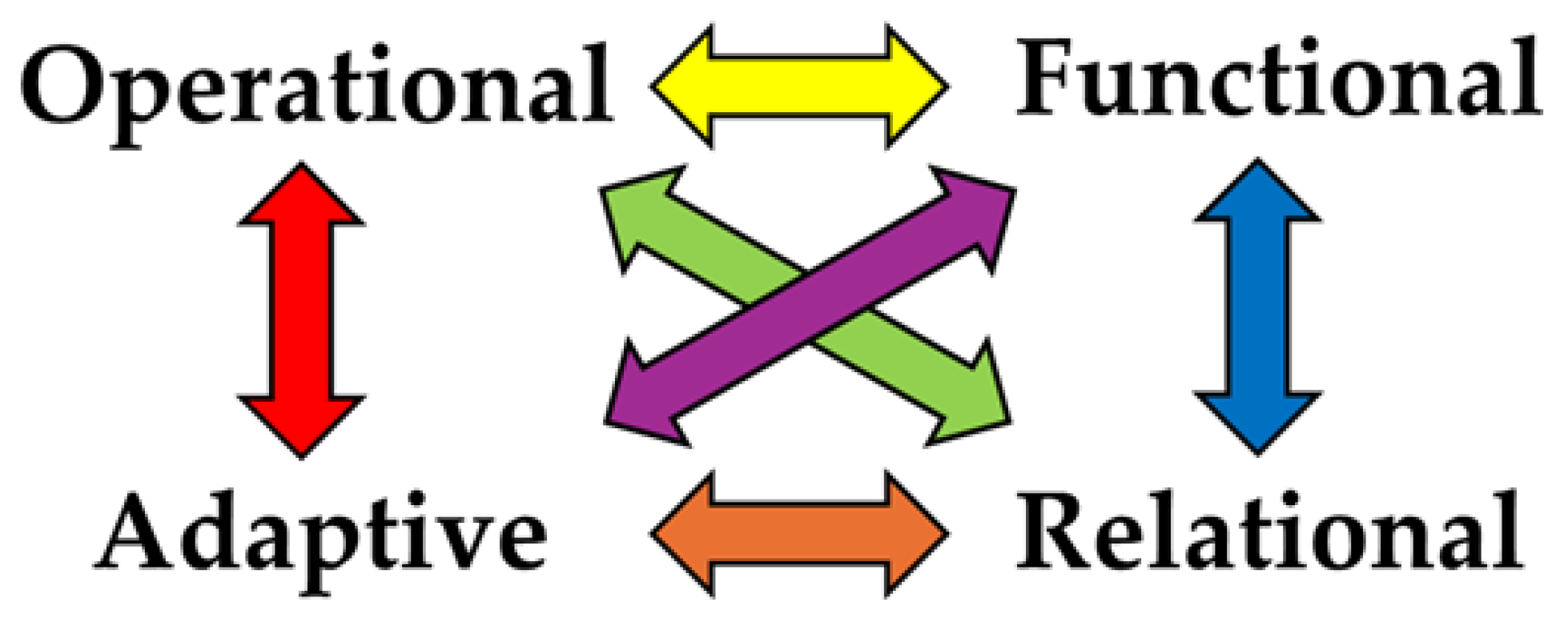

Figure 1 synthesises a framework with the key dimensions of nanostore identity derived from the literature review, categorising them as operational, functional, relational, and adaptive. Each dimension interacts dynamically to define the unique role of nanostores in retail landscapes and communities.

The operational dimension encompasses the physical & operational characteristics of nanostores. This refers to their size & format and close/distant location (e.g., urban/suburban/rural location) [

3,

17]. It also considers the operational roles, activities, and decision-making of shopkeepers and staff conducting retail operations [

5,

9,

16]. Supply chain constraints, inventory management, cash-flow management, and supply efficiencies are also part of the operational identity [

13]. From this perspective, looking at the operational dimension of nanostores informs about logistic and supply strategies, in-store operations, product inventories, space optimisation, resource allocation, and supplier negotiations.

The functional dimension points to the business and retail nanostores’ roles in driving customer responsiveness. This considers nanostores as micro family businesses and income sources, serving different socioeconomic levels (e.g., low, medium and high-income), degrees of accessibility (e.g., good vs poor), customer niches (e.g., affordability, proximity and convenience), and hyperlocal responsiveness (e.g., product search and home delivery services) [

5,

12,

19]. Moreover, the functional dimension covers product assortments of curated grocery products or additional services tailored to local demand and income levels [

4,

16]. The functional dimension informs about, for instance, differentiation and pricing strategies (e.g., leveraging proximity and product assortments), integrated services (as total customer solutions), and business support requirements (e.g., digital literacy enhancement, partnerships, infrastructure, and funding).

The relational dimension refers to nanostores’ social and community roles, including customer bonds (i.e., trust-based relationships), informal credit (i.e., “fiado”), and personalised services (e.g., personal shopping) [

9], community hubs (i.e., space for social interaction, information exchange, and local cohesion) [

6,

14], and informal economy pillars (i.e., providing a financial safety net for low-income customers) [

17]. The relational dimension emphasises the potential of nanostores to foster loyalty ties and establish community partnerships, such as offering service payments. Additionally, they can engage in community development initiatives, like selling products from local smallholder farmers and promoting goods or services from local stakeholders to support employment. Nanostores can also play a role in health and sustainability initiatives, such as improving access to healthy food.

Finally, the adaptive dimension sheds light on the resilience & evolution capability of nanostores. This involves their business model flexibility by location [

3,

17], hybridisation (e.g., blending traditional retail with digital tools [

5], and survival strategies (e.g., leveraging social capital to counter modern retail competition) [

11]. The adaptive dimension informs about innovation support capacity (e.g., e-commerce integration) and resilience-building capability (e.g., supplier collaborations and cooperation strategies with other nanostores) to face existing market environment challenges and opportunities.

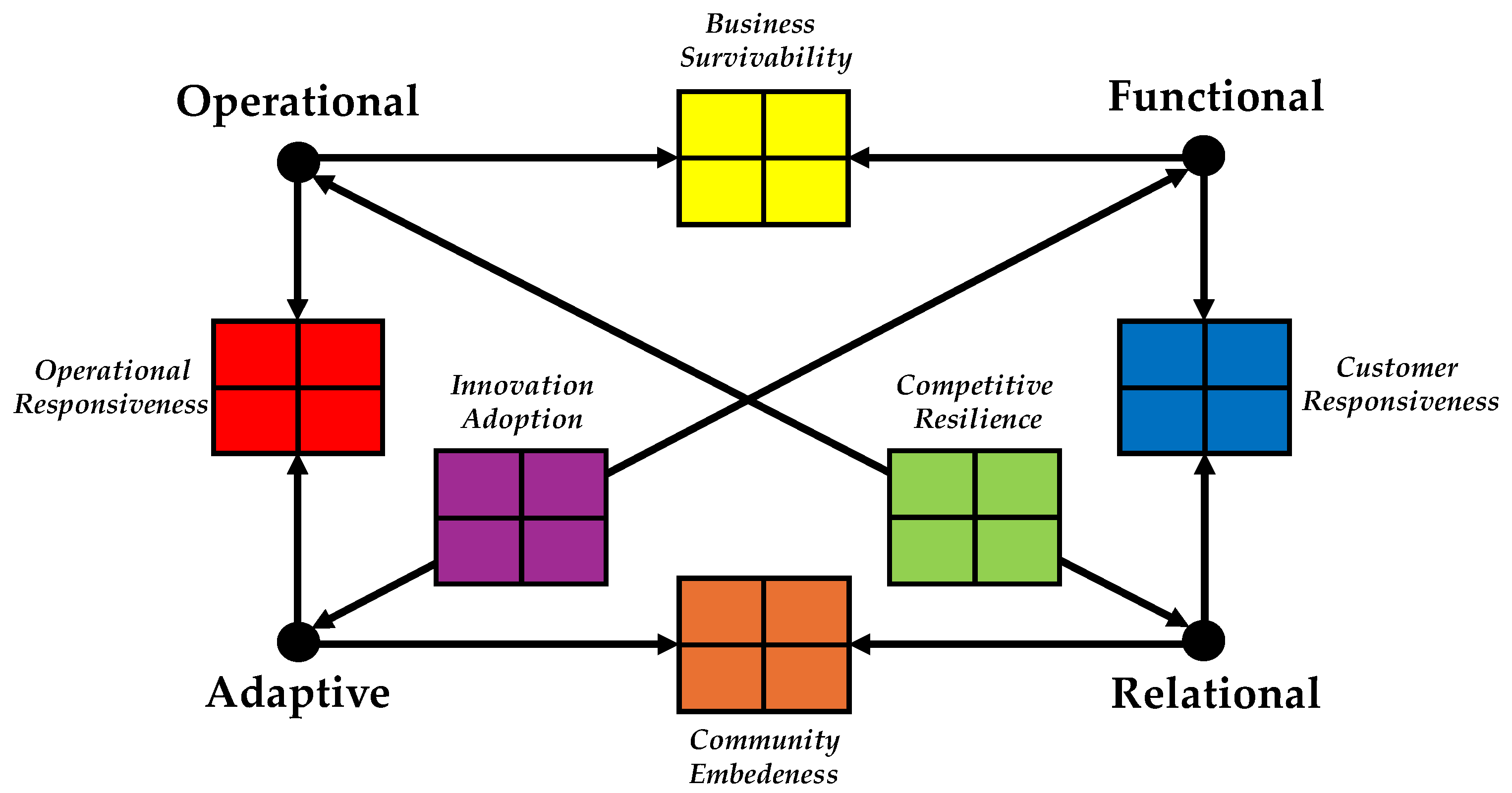

Therefore, the framework suggests that nanostore identity is shaped by the interplay of the four dimensions, resulting in six-dimensional combinations. Accordingly, twenty-four nanostore archetypes can be visualised in 2x2 matrices to plot how dimensions interact in particular contexts [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. The proposed archetypes are presented as follows:

Operational-Functional (

Table 1): Structure and functional capabilities drive sales and business survivability.

This interplay demonstrates how retail businesses’ success depends on both structural advantages (like location and space) and functional effectiveness (e.g., business model adaptation).

Shops with strong structures and advanced functionality become Thriving Hubs—optimising space, stock, offerings and customer experience. Those with strong structure but basic functionality are Stable but Limited, missing growth opportunities due to undifferentiated offerings and lack of tailored customer strategies. Businesses with weak structures but high adaptability become Hustle Heroes, overcoming limitations through customisation and agility, despite their constrained operations (e.g., reduced spaces and limited stocks). Meanwhile, At-Risk Shops, both with weak structure and basic functionality, are cluttered, under-resourced shops that struggle with inefficiencies and are vulnerable to failure.

Functional adaptability can compensate for structural weaknesses, while strong structure alone is insufficient without functional effectiveness. This interplay helps identify which businesses need support and what interventions, whether improving functionality or optimising structure, could enhance their accessibility and long-lasting resilience capacity.

- 2.

Functional-Relational (

Table 2): Functional capability and relations strengthen customer responsiveness and competitiveness.

The functional-relational intersection reveals four distinct archetypes that emerge from functional effectiveness and relational depth, demonstrating unique customer engagement, customer development, and business feasibility patterns.

Trust-Driven Functionals represent the finest configuration, successfully blending strong functional performance with deep customer relationships through personalised service, trust-based practices like informal credit systems, and local sourcing initiatives. These shops build strong customer loyalty by fulfilling practical needs and social expectations while growing community engagement upstream collaterally.

In contrast, Effective but Impersonal shops maintain competent functional performance with well-curated product selections but fail to develop meaningful customer relationships, resulting in transactional interactions that limit customer retention and affect customer experience despite their functional strengths. Community Safeguards demonstrate an alternative survival strategy, compensating for basic functional limitations through strong community ties and social support roles, though this makes them vulnerable to broader market pressures. The most vulnerable archetype, Fragile Outposts, struggles with deficiencies in both dimensions, lacking both distinctive product offerings and customer relationships, which leads to high closure risks in competitive markets.

This interplay highlights the importance of interventions designed to strengthen nanostores and train their owners to enhance the strategic perspective of their business models. Integrated approaches that address business operations and community relationships may yield the most sustainable improvements. The framework also helps explain why some stores thrive despite functional limitations and others fail despite the competent execution of basic retail functions.

- 3.

Relational-Adaptive (

Table 3): Relational and adaptive capability translate into community embeddedness and socioeconomic roles driving innovation.

The relational-adaptive matrix identifies four nanostore archetypes with distinct community integration and resilience patterns. Community Pillars exemplify ideal synergy, blending deep social ties (e.g., credit systems, local gatherings) with proactive adaptation (e.g., tech adoption and model innovation) to serve as dual commercial and social hubs. In contrast, Traditional Bonds rely solely on historical trust while resisting change and innovation, rendering them increasingly obsolete despite strong community roots.

Transaction-Focused shops prioritise operational agility (e.g., cost leadership, digital tools) but neglect relational depth, limiting loyalty and social-bonding resilience. Given the low level of trust they develop with their patronage, these shops are reactive to the market. The most vulnerable, Isolated Outposts lack high dynamic adaptation and deep community ties, operating with outdated practices and anonymous clientele that heighten closure risks.

Sustained resilience requires balancing social embeddedness with adaptability. The framework underscores that interventions must address relational and adaptive dimensions to strengthen nanostores, as neither operational competence nor community goodwill alone ensures longevity in fiercely competitive and evolving markets. This duality explains why some stores endure as neighbourhood members while others fail despite functional adequacy. The latter shows the importance of trust-based relationships and the social dimension that has not been explored in the literature on this topic.

- 4.

Adaptive-Operational (

Table 4)

: Adaptive and operational capabilities provide operational adaptability.

The interaction between adaptive capacity and operational constraints produces four distinct nanostore archetypes with varying survival strategies. Modernising Expanders combine strong adaptability with structural advantages, leveraging technology adoption and diffusion (e.g., digital payments, inventory apps) and prime locations to innovate and optimise resources. However, higher costs may challenge survivability. Resilient Improvisers thrive in constrained environments through hyperlocal responsiveness and technology adoption, yet face instability from constrained operations, stockouts and informal supply chains. These nanostores have great vision but fail to perform the daily operations effectively.

Conversely, Static Underperformers waste their operational potential by resisting modernisation and clinging to outdated methods and traditional practices despite having adequate space, technology readiness, customer-centric behaviour, and location advantages. Meanwhile, Vulnerable Traditionalists, hindered by rigid cash-only models, poor assortments, weak service offerings, and other structural limitations, struggle with inefficiencies operationally and strategically, and rely on dwindling loyalists, making them most prone to closure without intervention.

Adaptability offsets structural limitations while resistance to change amplifies operational weaknesses. Nanostore’s survivability depends on inherent operational strengths and the capacity to evolve within dynamic retail landscapes.

- 5.

Operational-Relational (

Table 5)

: Operational and relational capabilities develop competitive resilience.

The operational-relational matrix identifies four nanostore archetypes with distinct competitive trajectories. Unshakeable Nodes emerge as the most resilient, synergising prime locations and ample inventories with deep community bonds to create loyal customer bases that prefer them over supermarkets. Their dual strengths enable value-added services and institutional neighbourhood status. They rely on developing strong relationships with customers and suppliers, promoting collaboration to proactively achieve strategic and operational effectiveness.

Convenience Plays demonstrate how structural advantages alone provide only temporary protection. While accessible locations and stocked shelves ensure short-term survivability, their transactional relationships leave them vulnerable to chain competitors that can replicate their functional benefits at scale. Long-term survival requires cultivating deeper community ties and solid bases of customers and other stakeholders. Oasis Shops reveals how relational capital mitigates structural weaknesses. As essential providers in underserved areas, they maintain community dependence despite poor locations and limited stock, though growth remains constrained without operational improvements due to insufficient resources. The most vulnerable, Deserted Outposts, lack operational merits and customer relationships. Their isolation and generic offerings accelerate the decline in competitive markets, highlighting how neither dimension alone ensures survivability.

Successful nanostores transform structural assets into community value, while vulnerable ones overlook this synergy. Strategic interventions should therefore address these dimensions in tandem, helping stores evolve toward the Unshakeable Node ideal where physical and social advantages reinforce each other. This approach will also allow nanostores to develop a strategic, social-driven roadmap while driving efficient daily activities, which create a proper combination of agility, adaptability, and alignment strategies.

- 6.

Functional-Adaptive (

Table 6): Adaptive and functional capabilities (e.g., tailored assortments and accessibility) allow for innovation adoption.

The functional-adaptive matrix reveals four distinct approaches to innovation adoption in traditional retail. Retail Pioneers lead through comprehensive modernisation, combining updated technologies with niche business models, though their ambitious transformations risk overextension in resource-limited settings. Nimble Basics adopt a more selective strategy, focusing adaptive efforts on high-impact, context-specific innovations that maximise their limited operational capacity by prioritising the most promising strategies.

Conversely, Struggling Functionals possess adequate resources but lack adaptive agility, resulting in misaligned innovations that fail to meet market needs in the long term. The most vulnerable, Static Survivors, resist all changes with basic functional effectiveness, relying on inertia until market forces threaten their survival.

These four archetypes promote customised innovation strategies that consider each operational environment. Ultimately, retail innovation success is redefined as the capability for contextual implementation rather than simply adopting and diffusing technology or innovation.