1. Introduction

In vitro research offers advantages over in vivo research, such as tight control of the chemical and physical environment, reduced costs, decreased animal use, and higher throughput. However, classic in vitro experiments fail to replicate the conditions of living organisms. Isolated primary cells grown in in vitro environments differ from those in living organisms, which limits the value of in vitro data for predicting in vivo behaviors. Current in vivo research involves testing living subjects, creating ethical dilemmas [

1].

Cell-based processes often originate from experiments on rigid materials like polystyrene and glass that don’t mimic physiological conditions. Cells in these environments tend to exhibit abnormal behaviors: flattened shapes, unusual polarization, altered responses to drugs, and a loss of their specialized characteristics. These culture systems are typically two-dimensional (2D) [

2], whereas cells within the body receive signals from all dimensions, not just their bottom surface [

3]. Culture systems are needed that more accurately replicate the biological conditions.

Biomaterials now provide greater complexity in cell culture by controlling mechanical, compositional, and structural cues to replicate native tissues [

4]. Various systems have been developed, but hydrogel networks of water-swollen polymers have emerged as the most promising. Hydrogels mimic native extracellular matrices (ECMs), possess mechanical properties similar to soft tissues, and support cell adhesion and protein retention [

5].

Biodegradable scaffolds can be implanted into defective tissue sites to support regeneration [

6]. Cells infused onto scaffolds adhere in three dimensions (3D), proliferate, and secrete extracellular matrix [

7,

8]. Scaffolds are highly porous with interconnected microarchitecture mimicking living organisms [

9]. Scaffolds also provide pathways for nutrient transportation and cell signaling, promoting cell growth and tissue formation [

10]. Arabinoxylan (AX) forms continuous and cohesive matrices, producing jelly-like films [

11].

The biocompatibility of scaffold gels allows cells to adhere, function normally, migrate, and proliferate before creating new extracellular matrix [

12]. Due to biodegradability, cells can produce extracellular matrix while degrading the scaffold. The balance between mechanical properties and porosity of the scaffold enables cell migration and proliferation. Well-prepared scaffolds contain interconnected pores for cellular penetration, nutrient diffusion, and excretion of waste products [

13].

Hydrogels mimicking native extracellular matrix provide the mechanical environment for cellular responses and tissue creation in vitro [

14]. Cells respond to mechanical signals, such as fluid shear, applied strains, and confinement, while also generating forces in their surroundings [

15]. Stiffness is a key mechanical property of hydrogel, often used interchangeably with elasticity [

16]. Physical interactions affect the hydrogel’s dynamic properties, such as stress relaxation with suitable stiffness. Alternating blocks of sugars with alginate interacting with divalent cations ensure biological applications [

17], though stiffness changes with bivalent Ca+ concentration. Relative stiffness is quantified by elastic modulus or stress-strain tangent curve. Hydrogel stiffness can be tuned by altering the polymer concentration or cross-linking density, or both.

Hydrogels have proven useful in cell culture applications, revealing principles of cell behavior and offering tools for expanding various cell types in ways not achievable with conventional culture materials [

18]. While both natural and synthetic polymer-based hydrogels have their merits, e.g., high mechanical strength, ease of processing, and stability, natural polymer-based hydrogels excel in bioactive properties, biocompatibility, and biodegradability [

19]. Natural polymers serve a broader range of functions, facilitating better cell interactions and improving tissue performance [

20]. Additionally, natural polymers more easily incorporate cell membrane receptors and peptide ligands to promote cell adhesion [

21]. Another noteworthy feature of natural polymeric hydrogels is their capacity to retain cells and drugs, enabling controlled delivery, and they are suitable for modifications involving ligand attachment and crosslinking [

22]. Natural polymer-based hydrogels have garnered significant attention in clinical applications due to their minimal provocation of inflammatory or immunological responses in host tissues.

The objective of this study was to develop and evaluate a novel, cost-effective hydrogel system using sodium alginate and wheat bran-derived AX for cultivating 3D triple-negative breast cancer spheroids. This hybrid gel system aims to provide a more physiologically relevant microenvironment for cancer cell growth while supporting high-content imaging assays for rapid assessment of cellular toxicity, uptake, and treatment effects. Specifically, MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were used, being the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women [

23]. More than 40,000 women die from breast cancer in the US every year [

24]. Triple-negative breast cancer cells (TNBC) are the most aggressive type and lack estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors [

25]. Researchers use established triple-negative breast cancer cell lines like MDA-MB-231 [

26], which develop 3D spheroids [

27] for studying cell-cell interactions and the tumor microenvironment. These cells require specialized conditions to study their behavior more accurately in the laboratory [

28].

AX was extracted from wheat bran collected from a North Dakota milling company. Wheat bran constitutes about 15- 25% of milling byproducts but provides little profit due to transportation costs [

29]. Wheat bran primarily comprises the outer kernel layers and is composed of insoluble AX, cellulose, starch, protein, β-glucan, and lignin [

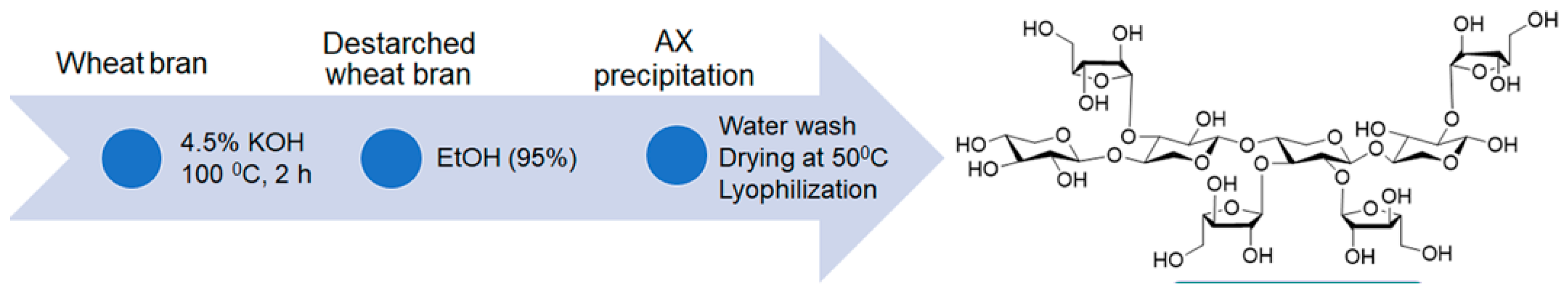

30]. The overall AX concentration ranges from 6.1% to 22.1% in bran and 1.4% to 2.8% in flour. Wheat bran AX constitutes approximately 29% of wheat’s total dietary fiber. Wheat bran is a valuable reservoir of hemicellulose compounds, with around 7.8% being water-soluble. AX, a polysaccharide, makes up 86.4% of the total water-soluble hemicellulose in wheat bran. AX, composed of arabinose and xylose pentose sugar units, displays a notably intricate molecular structure, characterized by a β-(1−4)-xylan backbone with α-(1−2) and α-(1−3) linked arabinose side chains (

Figure 1) [

31,

32].

AX’s chemical structure offers a platform for delivering bioactive molecules due to its branching and multifunctional chemical groups. The self-assembling behavior of AX resulted from the hydrophobic interactions, Van der Waals forces, and various intra- and intermolecular H-bonding among AX molecules. Previously, our group developed a facile and reproducible method to generate functional nanomaterials from wheat bran-derived AX and encapsulated the nanoparticle with nucleic acid and showed the potential of using AX for nucleic acid delivery. In this study, the spectroscopic characterization of AX, such as FTIR and

1H NMR were conducted [

31].

Sodium alginates from brown seaweed form hydrogels through ionic gelation with higher concentrations of Ca

2⁺, Sr

2⁺, or Ba

2⁺ ions [

33]. Research has shown that human intestinal organoids can be cultured in vitro and undergo epithelial differentiation in alginate hydrogels. Optimal cancer spheroid survival rates occurred in 1-2% alginate gels. The 0.5% alginate gel closely resembled those of commercial extracellular matrix (ECM) hydrogels [

34]. To enhance cell adhesion and the growth of cancer spheroids, a hybrid alginate-AX hydrogel was prepared that is cost-effective compared to commercial ECM mixtures and compatible with high-content imaging assays for cellular toxicity assessment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Extraction of AX from Wheat Bran

AX was extracted from wheat bran by a method developed by Lopez et al. with modifications following our previous work [

31]. An amount of 40 g of wheat bran was mixed with 400 mL of 4.5% potassium hydroxide (KOH) solution and stirred at 100 °C for 2 h. The resultant slurry was then centrifuged for 20 min at 8885 g, and the supernatant was collected. Thereafter, two times the volume of 95 % ethanol was added to the collected supernatant, and the suspension was stored at 4 °C for 16 h to ensure complete precipitation of AX. The precipitate was then collected by centrifugation (same speed and time above) and was washed thoroughly with distilled water to remove ethanol and excess KOH. Subsequently, the AX was dried in a vacuum oven at 40 °C for 24 h and was lyophilized at −50 °C using a freeze-dryer (Modulyod, Thermo Electron Corporation, USA). The chemical structure and the extraction process of AX are shown in

Figure 1.

2.2. Preparation for Stock Solutions

2.2.1. Preparation of the 4 % (w/v) Alginate Solution

Twenty-five milliliters of 4 % (w/v) sodium alginate solution were prepared by dissolving 1 g of sodium alginate (Fisher Scientific, USA) in 25 mL of PBS (Fisher Scientific, USA) in a heat-resistant flask, stirring with magnetic stirrers. Sodium alginate was added slowly to avoid precipitating sodium alginate in PBS. The solution was incubated at 50 °C for 2 h to fully dissolve the sodium alginate. The solution was sterilized in an autoclave under 15 psi at 121 °C for 30 minutes.

2.2.2. Preparation of the 2 % (w/v) AX Solution

A volume of 25 mL of 2 % (w/v) solution was prepared by dissolving 0.5 g of AX in 25 mL of ultrapure cell culture grade water (Fisher Scientific, USA) in a heat-resistant flask, and the AX was dissolved by continuously stirring the solution using a magnetic stirrer for 2 days. The AX solution was also autoclaved under the same conditions as the alginate solution.

2.3. Fabrication and Plating of Hydrogel

A working solution of hydrogel mix that contains 2% alginate and 1% AX (2:1) was prepared. A volume of 125 μL/well was prepared by mixing 62.5 μL of 4% (w/v) sodium alginate solution, 62.5μL of 2% (w/v) AX solution. This mixing process was done under the laminar flow hood (ESCO Class II BSC, Esco Technologies, Inc., USA) with vigorous shaking until a uniform-colored mixture was achieved. Before adding the sodium alginate-AX mixture to the well of the 24-well cell culture plate (Fisher Scientific, USA), the wells were coated with poly-D-lysine to prevent the alginate gels from detaching from the cell culture plastics during 3D culture. A 0.5 mg/mL poly-D-lysine solution was prepared by dissolving the powder in ultrapure water, and the solution was sterilized by passing it through a 0.22 μm filter. Two hundred fifty microliters (250 μL) of the prepared poly-D-lysine were added to each well of a 24-well plate, and the plate was incubated for an hour under UV light. One hundred twenty-five microliters (125 μl) of the alginate-AX working solution were added to the well by making sure that the bottom surface of the well was covered. Polymerization of the hydrogel was achieved by adding 100 mM of sterile CaCl2 solution, which was prepared by dissolving 735 mg CaCl2 dihydrate in 50 mL ultrapure water and sterilized in a similar way to the poly-D-lysine was sterilized. A volume of 100 μL of 100 mM CaCl2 sterile solution was carefully added to the hydrogel mix, and the solution was kept in a horizontal position undisturbed for 10 min at room temperature. Any unbound CaCl2 solution was removed carefully, and the hydrogel was washed with PBS.

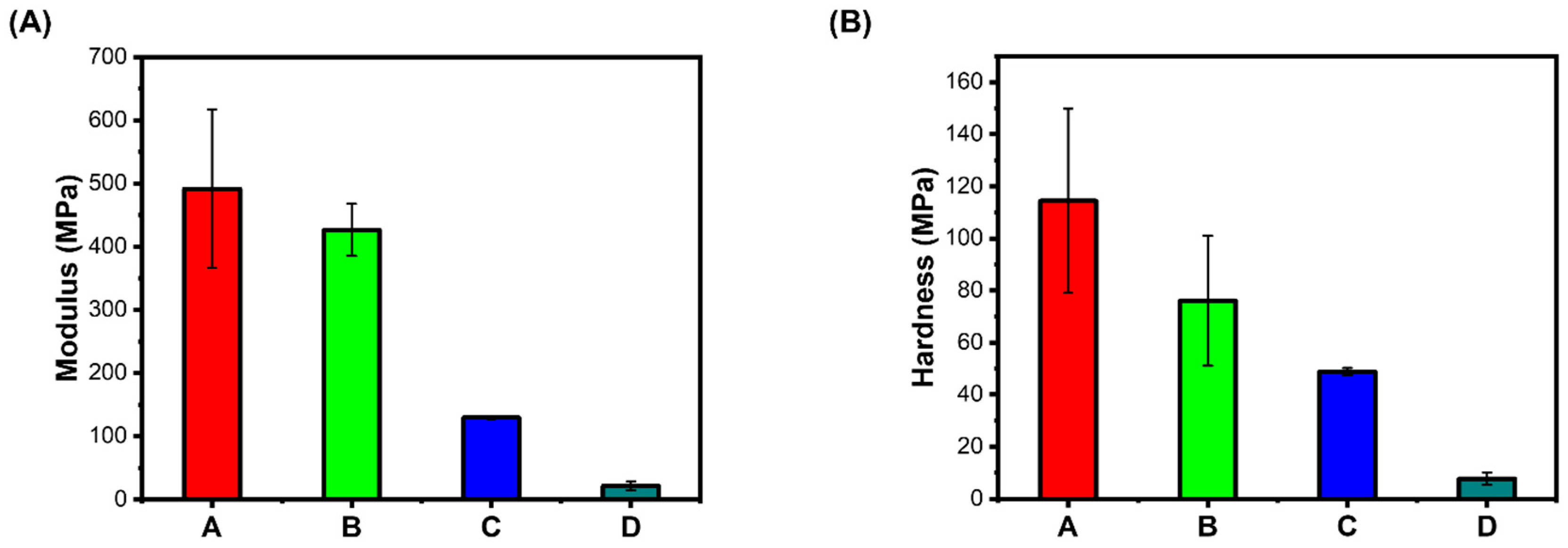

2.4. Mechanical Properties of Hydrogels

Elastic Modulus: Nanoindentation tests were carried out to comprehend the mechanical properties of the prepared hydrogels. The elastic modulus of the hydrogel A. wheat bran AX (WBAX) and Na- alginate (SA) (1:2) compared to B. sugar beet pulp arabinoxylan (SBAX) and SA (1:2), C. WBAX, SA, and collagen (C) (1:2:1), and D. SBAX, SA, and C (1:2:1). First, the gel samples were freeze-dried before placing to the indenter. Then, the samples were mounted on an iron base and loaded on the magnetic stage of HYSITRON, T1970 triboindenter. Before creating an indent in the gel samples, the Berkovich diamond indenter was calibrated using a quartz specimen. The air indentation was performed to calibrate the transducer electrostatic force and check the transducer plate spacing. The contact area between the sample and the tip was used to determine the sample’s elastic modulus. The visible light and scanning probe microscopes connected to a triboindenter were used to identify the indentation. A minimum of three indentations were performed on each specimen, and the average value was reported. The load function for each indentation was chosen in such a way that the peak load value was 500 μN, while the loading time of 10 s was the same as the unloading time. The unloading curve slope was used to calculate the specimens’ modulus and hardness, and the integral software was used to establish the maximum depth to which the indenter could be forced.

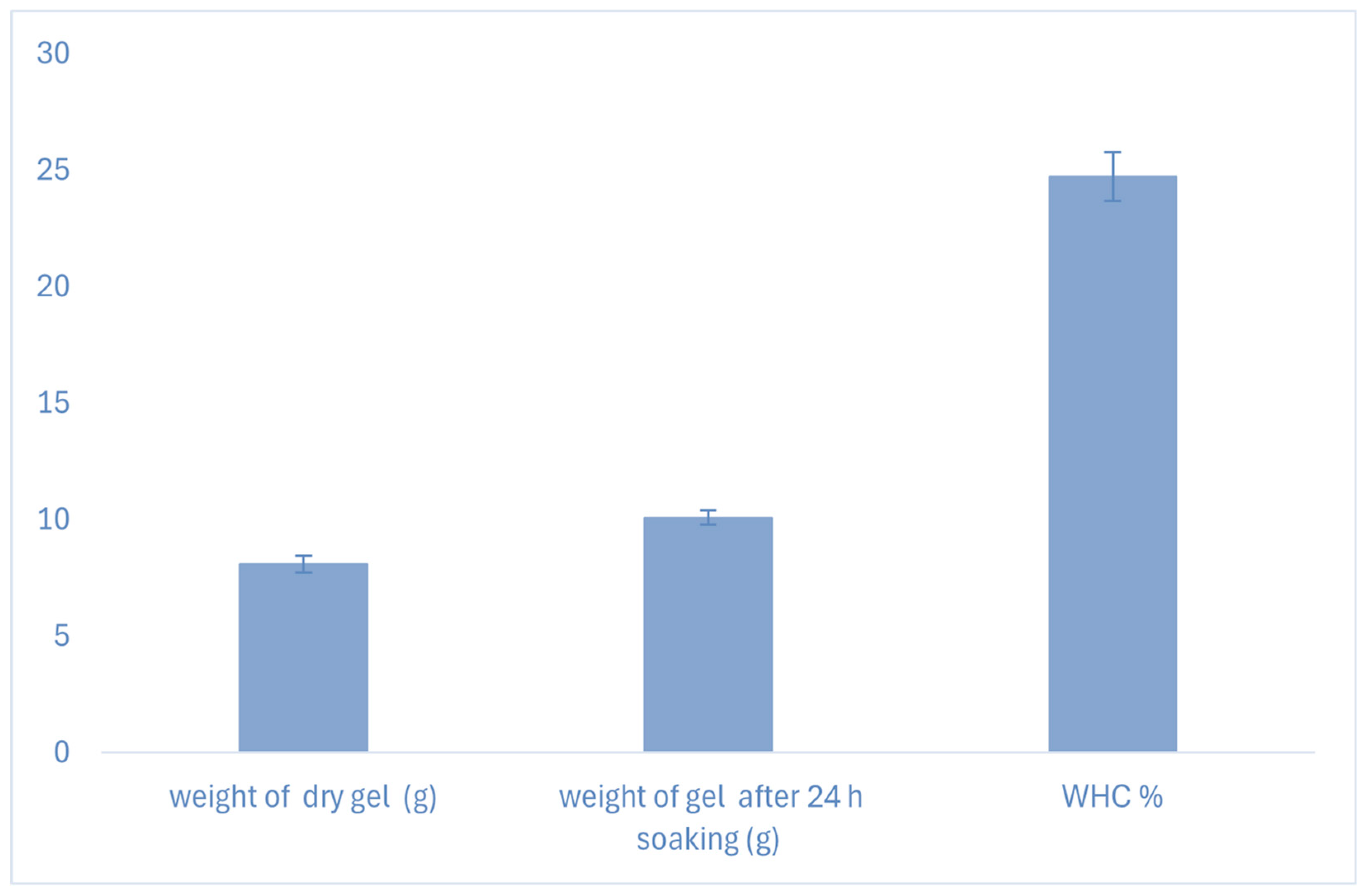

Water-Holding Capacity (WHC): The Water-Holding Capacity is the maximum amount of water absorbed and retained by a material under certain conditions. It is usually expressed as the % of water retained per weight of dry materials, and the most acceptable physicochemical property of the hydrogel for in vitro three-dimensional cell cultures [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. The WHC of the hydrogel has been determined by following the method described by Shiwei [

38]. The dry hydrogel was weighed as w

0 and placed into a beaker containing 50 mL of distilled water. The gels were allowed to soak for 24 hours. After 24 hours at room temperature, the hydrogel was removed from the water and weighed as w

1. Water-holding capacity (W

h%) was determined using the formula.

Where, w0 = initial weight of the hydrogel in (g); w1 = final weight of the hydrogel after soaking in (g), Wh = water holding capacity in %.

2.5. Cell Thawing, Cell Plating, Propagation, and Collection

Cryopreserved human breast cancer cell lines MDA-MB-231 (ATCC®) were thawed in a water bath at 37 °C. The MDA MB-231 cells were maintained in a monolayer within a T75 flask (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) in the DMEM-enriched medium (Cytiva, USA). The cells were harvested once the cell culture flasks were 80% confluent. The flask was transferred into laminar flow and incubated at 37 °C after adding 6 mL of TrypLE, and the progress of the detachment of the cells was observed every 5 minutes until they were fully detached. After the cells were detached, an equal volume of media was added to quench the TypLE activity. The cell suspension was transferred into 50 mL centrifuge tubes (32.5 mL each) and centrifuged at 200 X g for 10 minutes. The supernatant was removed, and the cells were resuspended in 15 mL of fresh media. Three hundred microliters (300 μL) of the MDA MB-231 suspension were seeded into each well (7500 cells/well) on the hydrogel. The plate was incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2, for 21 days, with the culture medium refreshed every 4-5 days. A 40-1500X Inverted Phase-Contrast + Fluorescence Microscope fitted with 15X eyepieces (30mm), UV-Filter(365nm/450nm), B1(480nm/535nm), G1(560nm/635nm) filters, 6MP Extreme Low-light Camera (AmScope™, USA) was used to observe the progress of cell growth and development and image analysis.

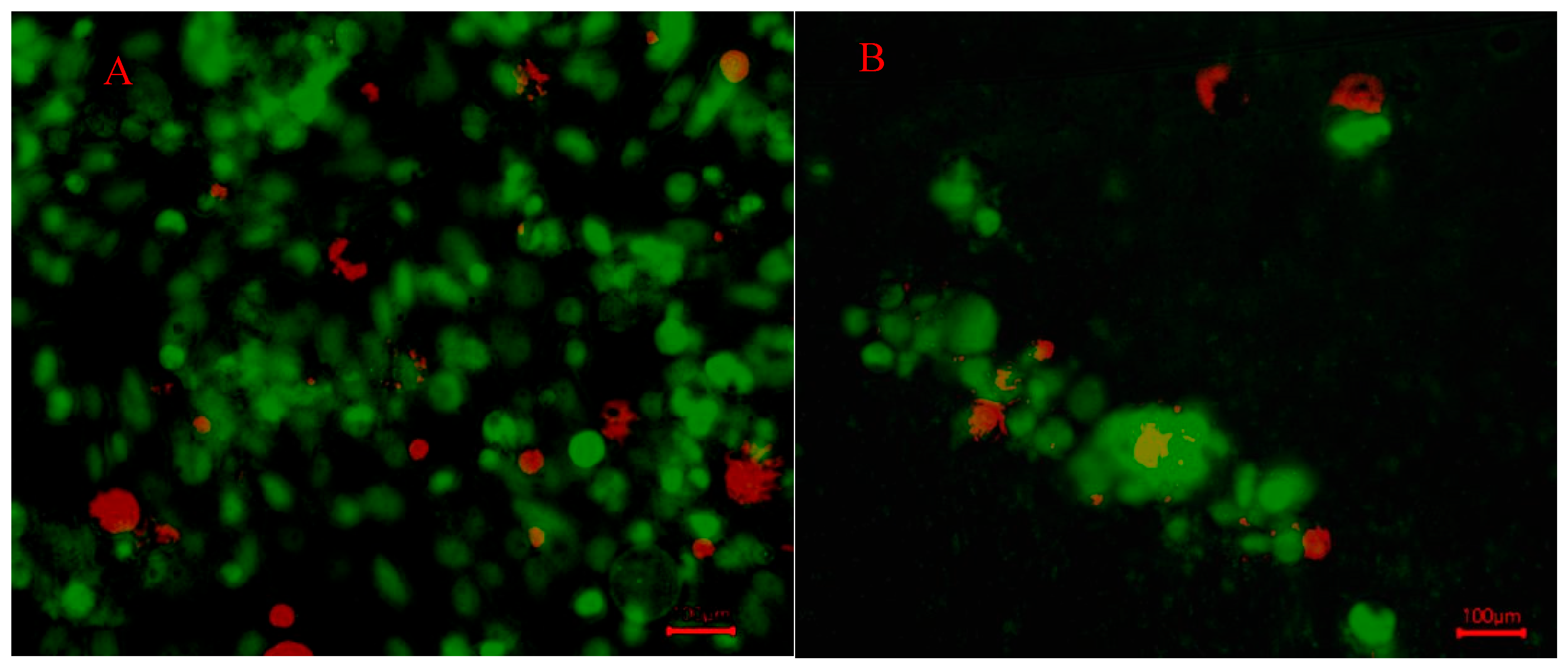

2.6. Cell Staining

The cells in the 3D scaffold gels were stained to analyze the concentration of live and dead cells. SYBR green dye and red propidium iodide were added to the wells. The green dye penetrates all cells, living and dead, and the red dye only penetrates cells with membranes that are no longer intact. Therefore, the cells fluorescing green were living, and the cells fluorescing red were considered dead [

20,

40]. Live/dead cell staining was performed using SYBR

® Green I, nucleic acid gel stain, 10,000X concentrate in DMSO, Lot No. 24117W (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and Propidium Iodide, Solution in Water, 1 mg/mL Lot: 19PO628, Mwt: 668.4 (Biotium, Inc., USA).

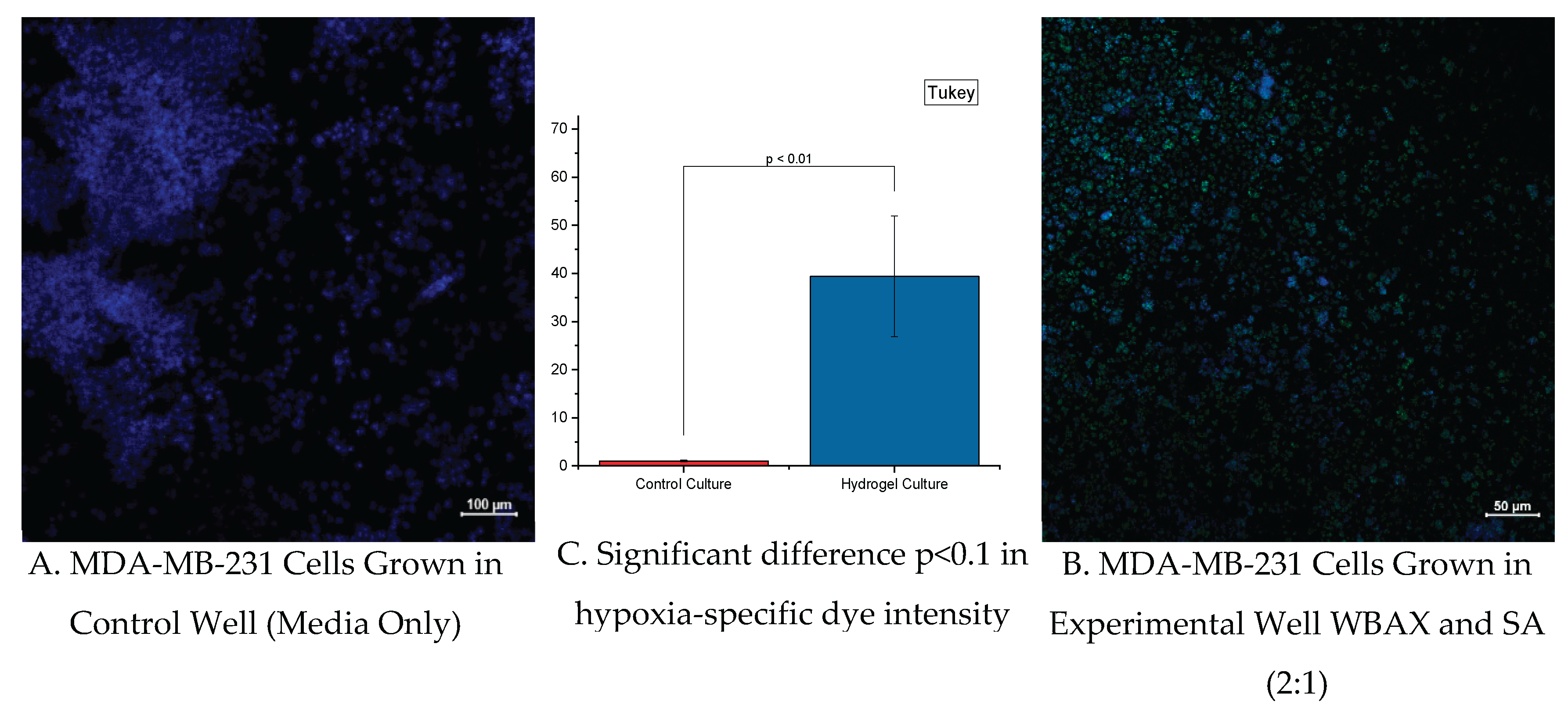

To determine the presence of hypoxia within the microenvironment, hydrogel cell cultures of MDA-MB-231 (ATCC®) were stained with green hypoxia dye, specifically Image-iT™ Green Hypoxia Reagent (5 µM), Lot No. I14833 (Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA). The dye doesn’t become fluorescent until atmospheric oxygen levels are less than 5%, and it is irreversible even when oxygen levels are returned to normal. The Hypoxia dye was incubated with living cells for 1.5 hours before being fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. Once imaged to capture the intensity of hypoxia, the fixed-hydrogel cell cultures were submerged with 0.1% Triton for 30 minutes, bovine serum albumin for blocking for 4 hours, and fluorescent stain 4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole or DAPI (~1 ug/mL), Cat. No. 40,011 (Biotium, Inc., USA) for 30 minutes to stain cell nuclei for identification. Images were captured with a Zeiss Airyscan Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope or AC-LSM (immunofluorescence, Zeiss Microscopy, North Dakota State University, ND, USA).

5. Conclusions

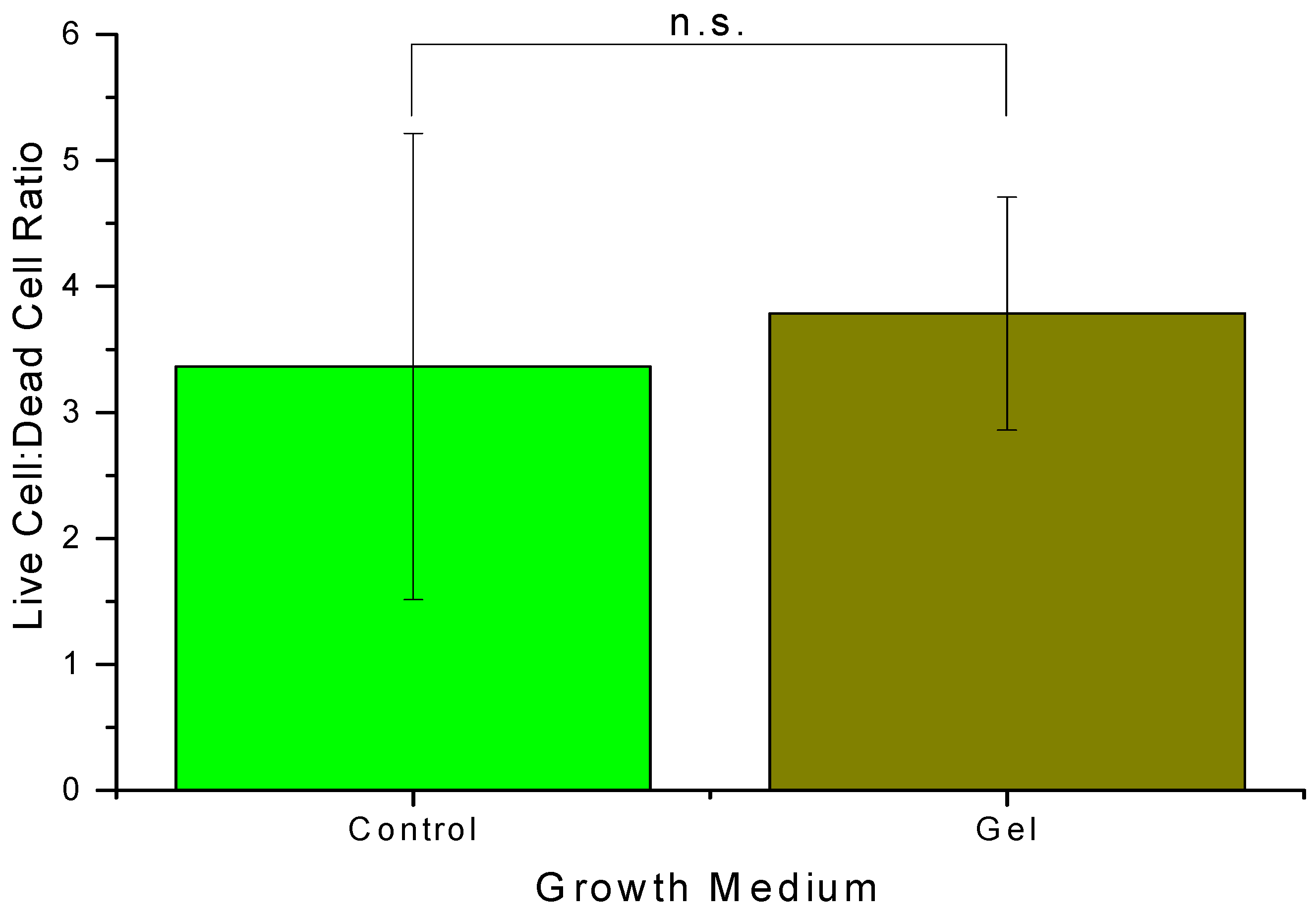

As for the in vitro component concerning AX, the breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells were cultured successfully, in 2D and 3D conditions. However, there was a clear difference in morphology between the control and AX treatment groups, with a greater degree of clumping of cells (characteristic of early-stage tumor spheroid formation) in the AX treatment group. The scaffolds, prepared with wheat bran AX mixed with Na-alginate, showed sustainable growth and development of cancer cells (up to 21 days). This natural polymer-based scaffold may have excellent biocompatibility and tunable mechanical properties. However, further studies on cell growth and development are important.

Cell growth of MDA-MB-231 in hydrogels persisted for up to three weeks with continuous cellular respiration (as indicated by a change of phenol red color of DMEM cell culture media). Morphology change was shown due to the absence of a fixed surface for cellular attachment, but this did not deter cell growth. Additionally, the WBAX and sodium alginate hydrogel induce a hypoxic microenvironment for the cells to grow, which closely mimics solid tumor conditions compared to conventional cell culture circumstances. More studies to assess phenotypic alterations and cancer stemness will need to be conducted to determine whether or not this hydrogel formulation induces similar changes seen in cells grown in solid tumor physiological settings. We have developed more hydrogel systems using AX from another agricultural byproduct, sugar beet pulp, and incorporating a natural protein source such as collagen.