1. Introduction

Dental erosion, defined as the irreversible loss of dental hard tissue due to chemical processes not involving bacterial activity, has emerged as a growing oral health concern in the 21st century [

1]. Unlike caries and periodontal disease, which are associated with bacterial biofilms, dental erosion progresses due to extrinsic or intrinsic chemical challenges acting directly on the tooth surface. These processes may go unnoticed until significant structural injury has occurred, leading to functional and aesthetic complications [

2].

The diagnosis of erosion may be clinically challenging due to its asymptomatic progression. Patients are often unaware of the condition until dentin becomes exposed or the tooth surface undergoes visible morphological change. In many cases, early-stage lesions are missed during routine dental examinations, contributing to underdiagnosis and delayed intervention [

3]. The importance of identifying erosion early is underscored by its irreversible nature and potential to affect quality of life through hypersensitivity, enamel translucency loss, and restorative complications [

4].

Global evidence suggests that dental erosion is increasingly common in young adults [

2]. Recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses estimate the worldwide prevalence of erosive tooth wear in youth to range from 25% to over 50%, depending on age group, region, and diagnostic criteria [

5,

6,

7]. However, the incidence of dental erosion—defined as the number of new cases developing over a period of time—is rarely reported, particularly in prospective studies. While prevalence data reflect a snapshot of disease burden, incidence studies are crucial for understanding the dynamic nature of disease progression and for identifying emerging trends in specific populations [

7].

Despite growing interest in erosion-related research globally, there is a notable lack of longitudinal studies in Eastern European populations [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Most research from this region, including Romania, remains cross-sectional and does not provide information on the natural course of erosive wear [

13]. In particular, there is limited data on erosion development in young adults—a group often considered at the early stages of exposure and disease onset. Understanding erosion incidence in this population could provide important guidance for preventive strategies, early diagnosis, and targeted public health messaging [

12].

Furthermore, little is known about how demographic variables such as gender may influence the development of erosive lesions over time. However, studies have suggested that males may be at higher risk due to behavioral, anatomical, or physiological factors [

12], still findings remain inconsistent and underexplored in Eastern European contexts [

11].

The BEWE index was first introduced in 2008 by Bartlett et al. as a simplified, standardized scoring system designed to facilitate clinical and epidemiological assessments of erosive tooth wear [

14]. Since then, it has become a cornerstone tool in both general dentistry and research for tracking the severity and progression of non-carious enamel loss. For clinical and research purposes, the Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE) index has been widely adopted as a standardized method for assessing erosive tooth wear [

8]. Its structure allows clinicians to classify severity by scoring the most affected surface in each sextant, generating a cumulative score that guides clinical risk assessment and monitoring over time. The BEWE has shown good intra- and inter-examiner reliability and has been recommended by the European consensus group on tooth wear as a suitable tool for use in both general practice and epidemiological research [

15].

With advancements in digital dentistry, intraoral scanning technology has introduced novel possibilities for objective and reproducible measurement of enamel loss. By capturing high-resolution, three-dimensional surface data, intraoral scanners enable digital quantification of dental erosion over successive time points. This approach allows for precise monitoring of changes in enamel volume or surface contours, overcoming some limitations of visual indices and providing a valuable validation tool for clinical findings [

16].

The present longitudinal study was conducted over a ten-year period in Târgu Mureș, Romania, with the following aims:

To assess the ten-year incidence of dental erosion in a cohort of healthy young adults using the BEWE index.

To investigate whether gender or other demographic factors are associated with the development of new erosive lesions.

To evaluate the sensitivity of the digital surface analysis in detecting early or localized erosive changes not captured by BEWE.

To validate clinical findings through 3D digital surface loss analysis using intraoral scanning and quantitative measurement of enamel wear.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

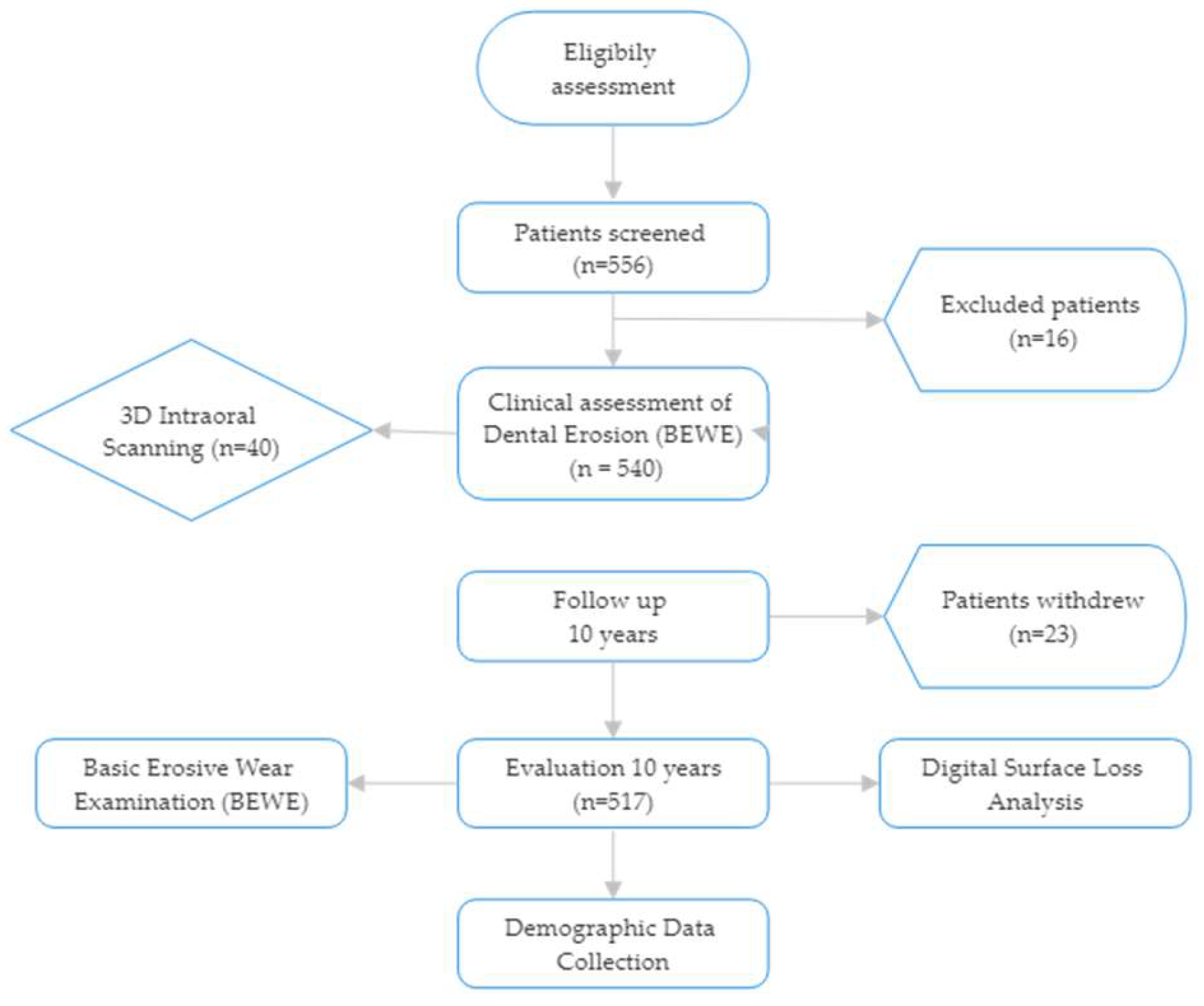

This prospective, longitudinal observational study was conducted over ten years (2014–2024) in Târgu Mureș, Romania. The study aimed to evaluate the incidence and progression of dental erosion in a cohort of healthy young adults. Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee (Approval No. 432/2014), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Participant Selection and Follow-Up

A total of 540 healthy adults aged 18–30 years were recruited in 2014 from university and community clinics. Inclusion required a full dentition (excluding third molars) and a BEWE score of 0 (no signs of erosion) at baseline. Exclusion criteria included:

Diagnosed gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or eating disorders,

Use of medications causing xerostomia,

Fixed orthodontic appliances or extensive restorations affecting enamel integrity.

At the 2024 follow-up, 517 participants (95.7%) were successfully re-examined; 23 participants were lost for follow up.

2.2. Clinical Assessment of Dental Erosion

2.2.1. Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE)

Dental erosion was assessed at baseline and follow-up using the BEWE index [

15]. The dentition was divided into six sextants, and the most severely affected tooth surface in each sextant was scored as follows: 0: No erosion; 1: Initial loss of surface texture; 2: Distinct hard tissue loss <50% of the surface area; 3: Hard tissue loss ≥50% of the surface area.

A BEWE score ≥1 in any sextant at follow-up indicated dental erosion diagnosis. All clinical assessments were performed by two calibrated examiners, and inter-examiner reliability was high (Cohen’s kappa = 0.87).

Impressions for each patient were recorded and casts were poured appropriately marked to be recognized upon follow up.

2.2.2. Digital Surface Loss Analysis (3D Intraoral Scanning)

To objectively quantify enamel wear, a selected subgroup of 40 participants (20 males, 20 females) underwent digital scanning at follow-up. The baseline dental casts were also scanned.

Scanning Procedure: Intraoral scans were captured using a MEDIT i700 scanner [

18]. STL files were processed using Exocad DentalCAD (Exocad, GmbH) software. Superimposition of baseline and follow-up scans was performed using best-fit alignment to detect enamel loss on the buccal and palatal surfaces of anterior teeth. Enamel surface loss >30 µm was defined as clinically significant [

1].

Digital Outcomes:

Mean enamel loss per participant (in microns)

Localization of wear (palatal vs buccal surfaces)

Correlation with BEWE score and intraoral scanning

2.2.3. Demographic Data Collection

Basic demographic variables (age and sex) were collected at baseline. Due to the non-interventional design, no dietary, behavioral, or salivary data were recorded.

2.2.4. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS v 26.0. Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic data, erosion incidence BEWE distribution, and digital wear measurements. Group comparisons included:

Chi-square tests for gender differences in erosion incidence

Relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI)

Pearson’s correlation coefficient to evaluate the relationship between clinical scores and 3D enamel loss

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

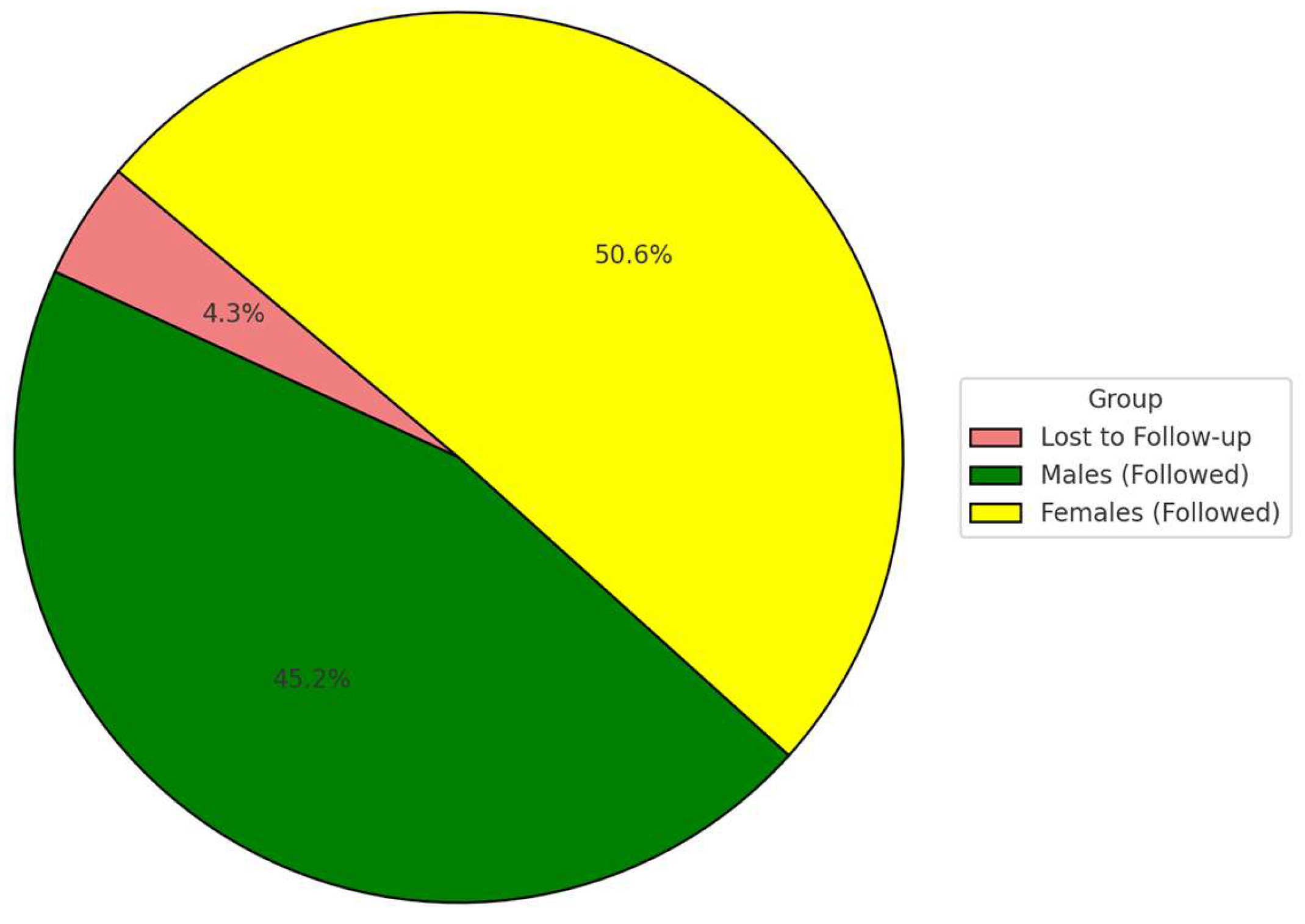

A total of 540 young adult participants were enrolled at baseline in 2014. At the 2024 follow-up, 517 participants (95.7%) were successfully re-examined and included in the final analysis. The mean age at baseline was 24.7 ± 3.1 years, and the follow-up mean age was 34.7 years. The gender distribution was 244 males (47.2%) and 273 females (52.8%) (

Figure 2).

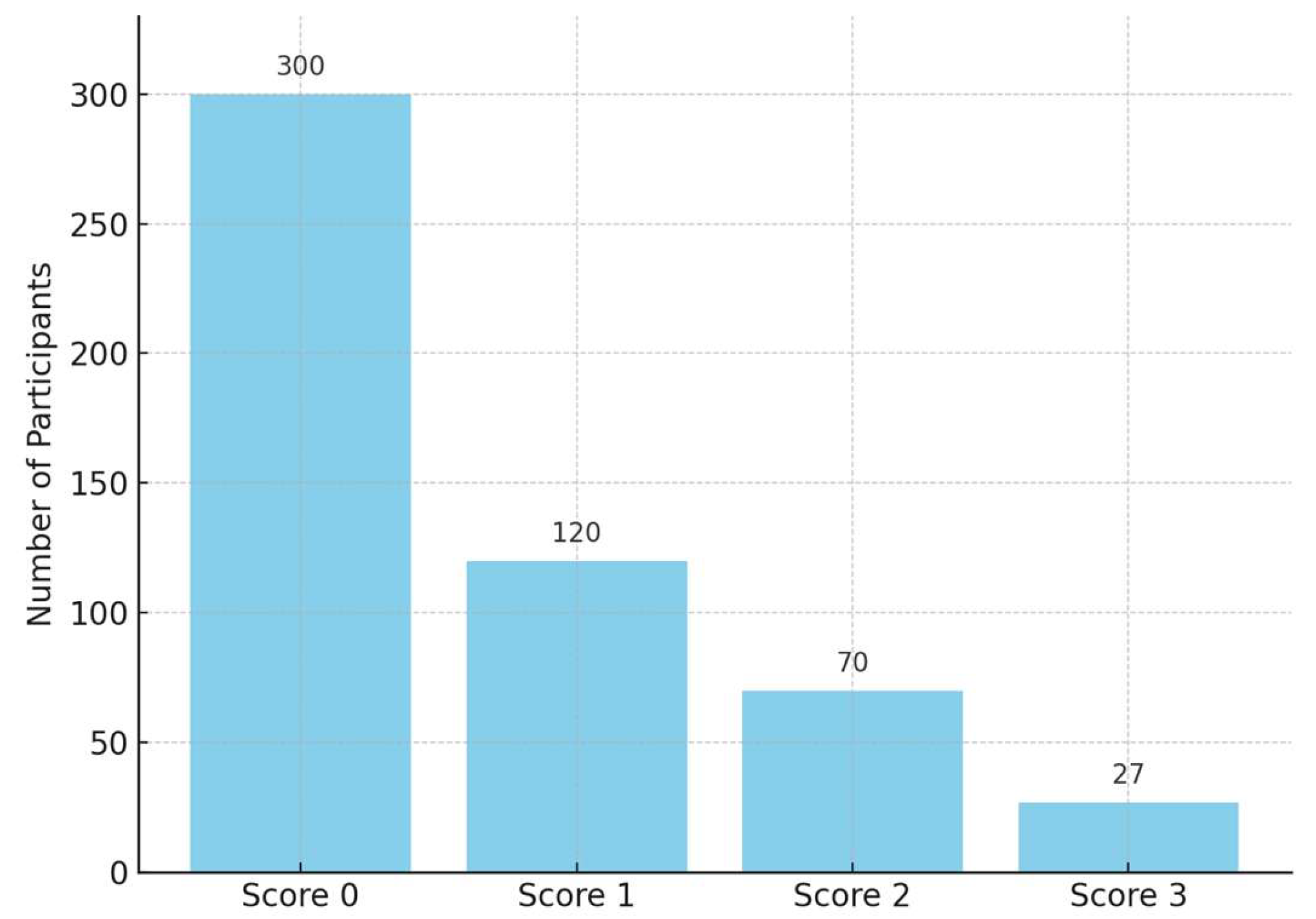

Dental Erosion Incidence

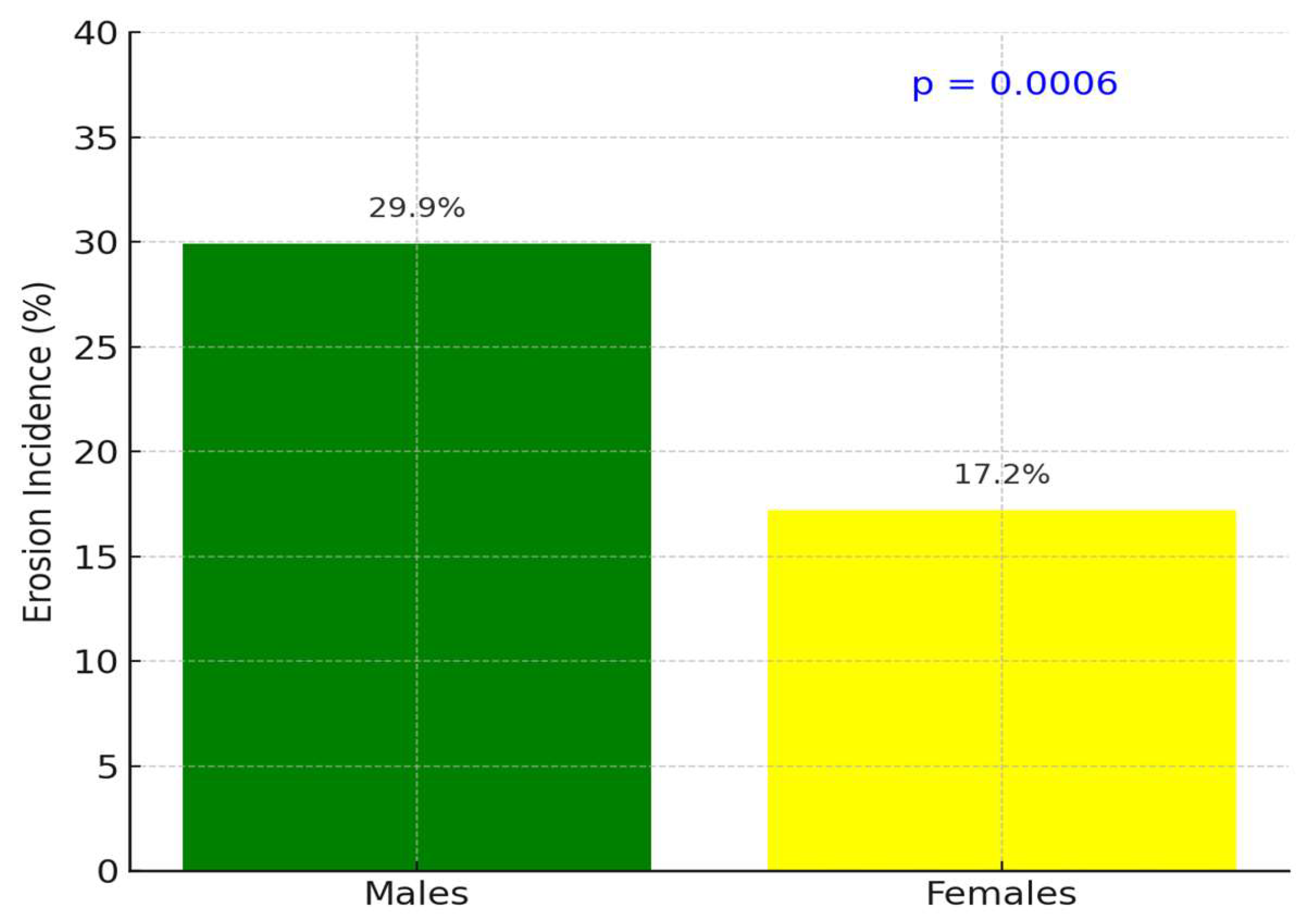

Over the 10-year period, 120 of the 517 participants (23.2%) developed dental erosion lesions on at least one tooth surface. Erosive wear incidence differed markedly by gender (

Table 1). Males exhibited a higher incidence (73 of 244; 29.9%) compared to females (47 of 273; 17.2%). A chi-square test confirmed that the incidence of erosion was significantly greater in males p = 0.0006 (statistically significant at p < 0.001,

Figure 3). The relative risk of developing dental erosion for males versus females was 1.74 (95% confidence interval: 1.26–2.40), indicating that male participants were about 74% more likely to experience new erosive wear over the decade than female participants.

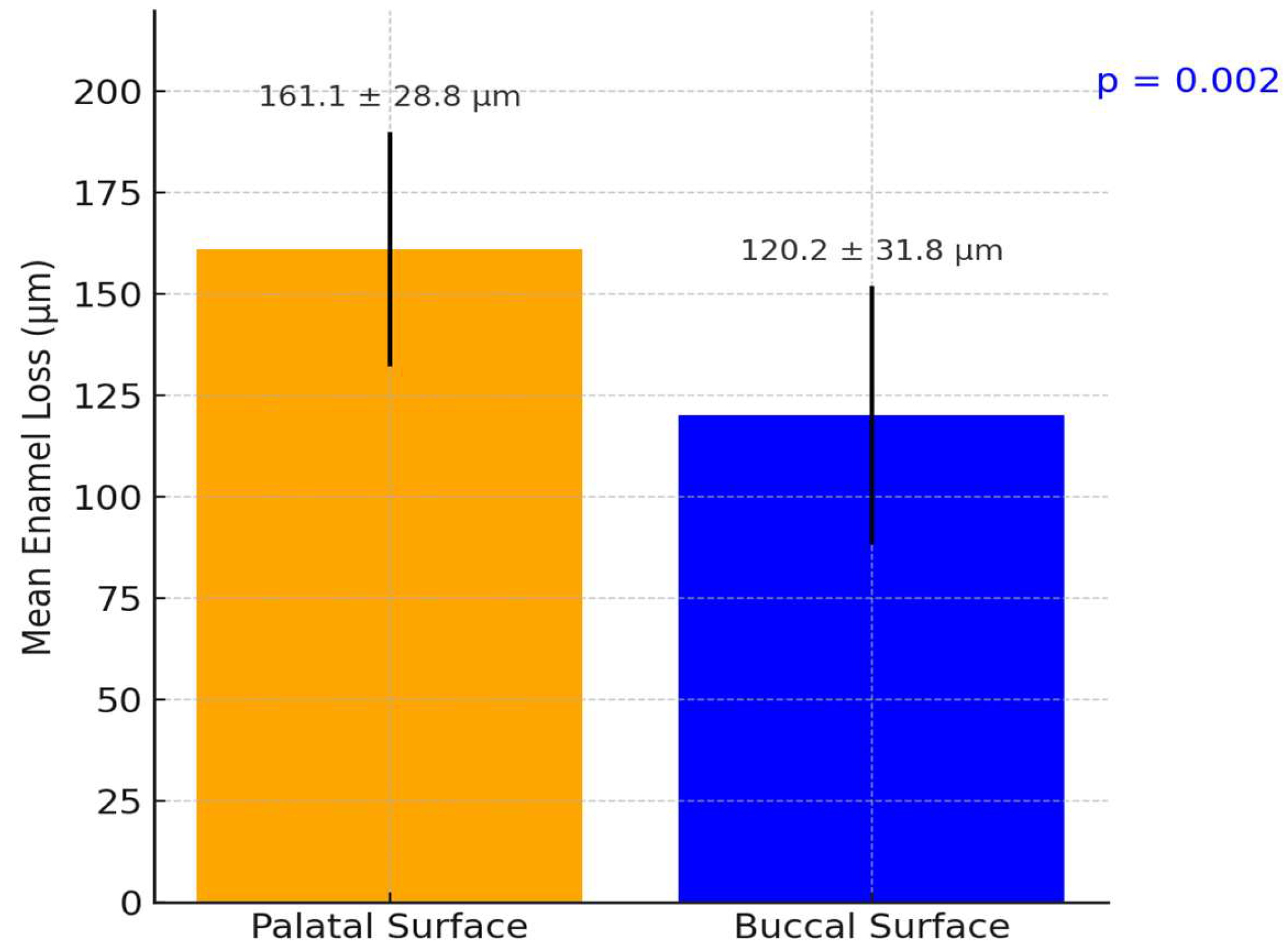

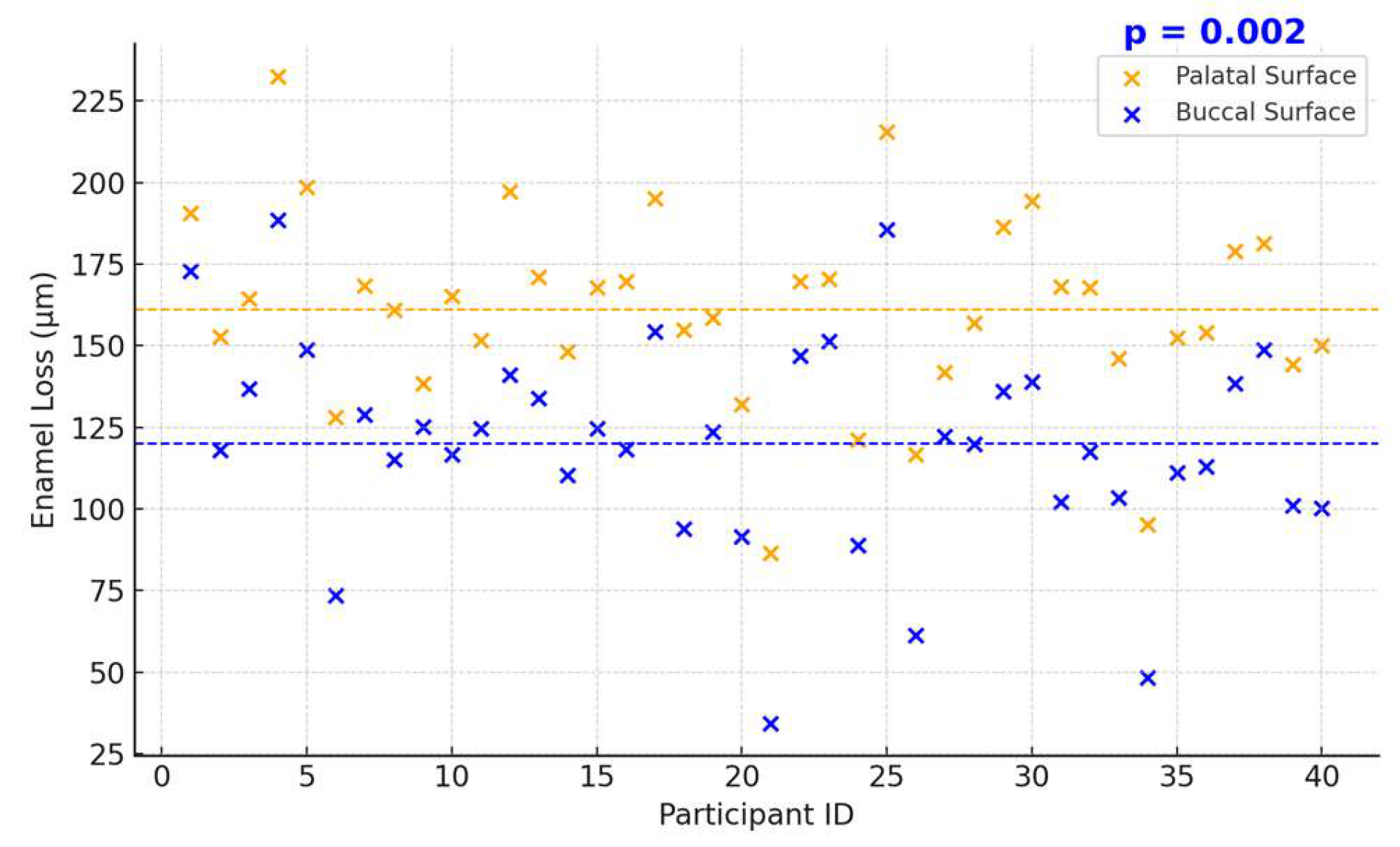

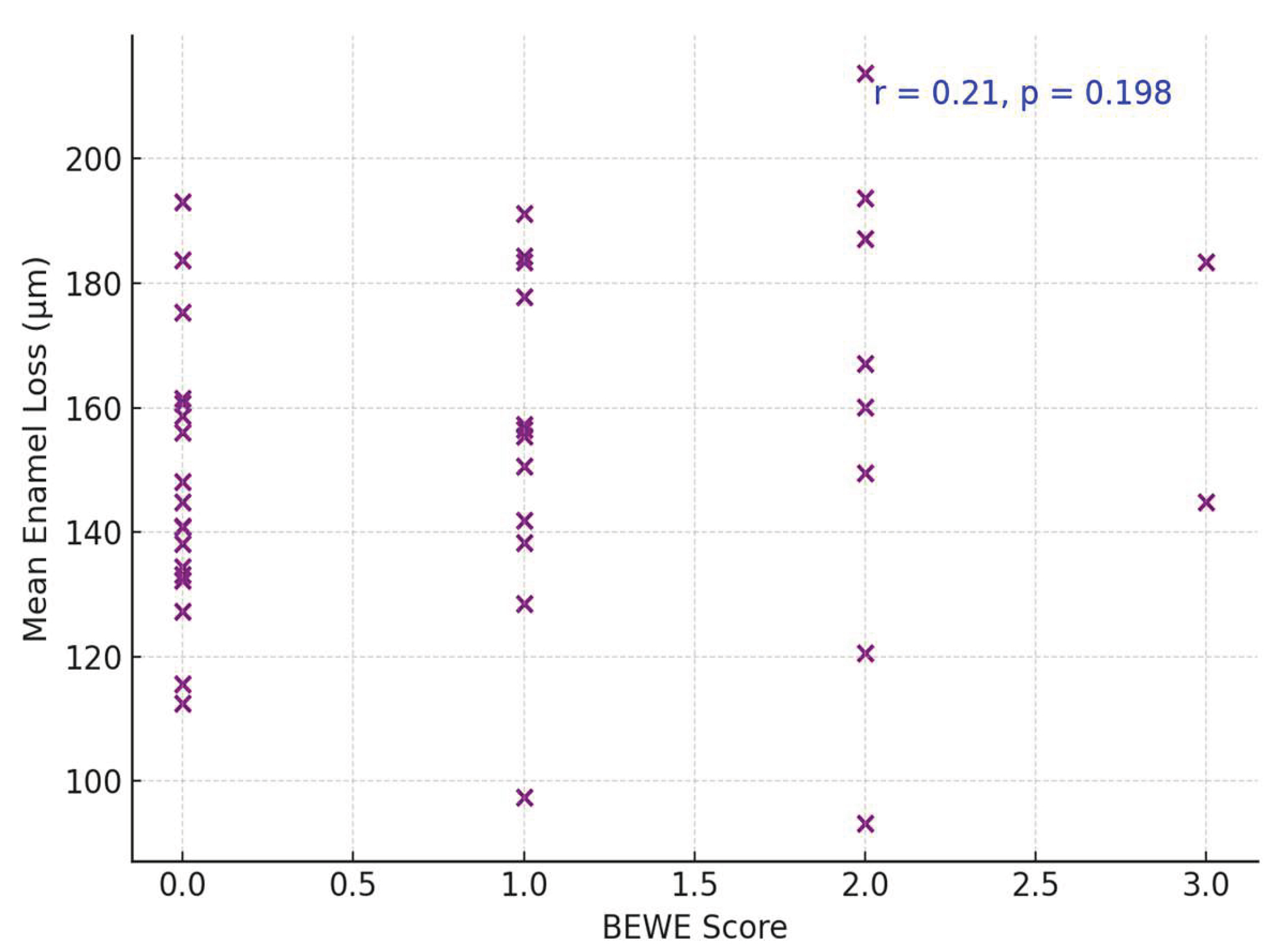

The extent of measured enamel loss also correlated positively with the clinical erosion indices recorded at follow-up: participants with higher BEWE scores tended to have greater enamel loss (

Figure 4). 3D volumetric analysis showed a mean enamel thickness loss of approximately 137 ± 79 µm per participant over the decade. Palatal surfaces had significantly greater mean enamel loss than buccal surfaces (mean palatal loss 162 ± 85 µm vs. buccal loss 114 ± 66 µm;

p = 0.002, paired comparison,

Figure 5, 6). Pearson’s correlation between mean enamel loss and BEWE score was about

r = 0.58, (

p < 0.001), indicating a moderate association between the clinically scored wear and actual enamel thickness loss.

Figure 4.

BEWE Score Distribution (no p-value, descriptive). Digital Surface Loss Analysis (n = 40).

Figure 4.

BEWE Score Distribution (no p-value, descriptive). Digital Surface Loss Analysis (n = 40).

Figure 5.

Mean digitally measured enamel surface loss after 10 years (n=40).

Figure 5.

Mean digitally measured enamel surface loss after 10 years (n=40).

Figure 6.

Distribution of mean enamel loss per participant over 10 years in the digital analysis subset (n = 40).

Figure 6.

Distribution of mean enamel loss per participant over 10 years in the digital analysis subset (n = 40).

Over half the participants exhibited <150 µm of enamel loss on average, whereas a minority (12.5%) experienced ≥250 µm loss. Only one participant exceeded 300 µm of mean loss, indicating that extreme erosive loss was uncommon in this group (

Figure 7). The correlation between BEWE scores and digital enamel loss measurements was moderate and statistically significant (r = 0.58, p <0.001), indicating a clear relationship between clinical assessments and quantitative digital findings.

4. Discussion

Long-term studies indicate that a significant proportion of young adults develop new erosive tooth wear over a decade. In a Romanian 10-year longitudinal cohort of young adults, it was observed a notable increase in the presence and severity of dental erosion from baseline to the ten-year follow-up. This trend aligns with international longitudinal data. For example, a Swedish 4-year study in adolescents reported that 76% of initially erosion-free individuals developed erosive lesions over that short period [

17]. In Norway, a cohort examined at ages 15 and 18 showed prevalence rising from 51% to 60% (with about 18% of those initially healthy developing erosion in 3 years) [

18]. Over six years (ages 15 to 21), prevalence similarly climbed from 57% to 60%, indicating a ~6% incidence of new cases into early adulthood [

18]. These findings suggest that the ten-year incidence in young adults internationally may fall in the tens of percentage points, depending on baseline risk and age. Cross-sectional surveys likewise show high cumulative prevalence by the late 20s. Many countries report roughly 30–50% of young adults exhibit some erosive. In fact, a European multi-center study found over 50% of 18–35 year-olds had at least some dental erosion, and a Swedish study noted prevalence as high as 75% in this age range [

18]. Notably, high-income populations often show greater erosion; for instance, surveys in the UK and Scandinavia consistently find over one-third of youths affected [

19]. The Romanian cohort’s ten-year results appear to mirror these global patterns, reinforcing that erosive wear is a progressive condition during late adolescence and early adulthood across diverse populations. Factors like increased exposure to dietary acids and changing lifestyles likely drive the upward trend worldwide [

20].

4.1. Gender Differences in Erosion Risk and Severity

A consistent finding across studies is that males tend to exhibit higher dental erosion prevalence and severity than females in comparable age groups [

17]. The Romanian 10-year study reportedly found men experiencing more pronounced progression of erosive lesions than women, which is in line with international data. A large adolescent survey in Stockholm County, Sweden found dental erosion significantly more prevalent and severe in males than females [

17]. Specifically, 15- to 17-year-old boys had higher rates of erosive wear, including severe (dentin-level) lesions, compared to girls [

17]. Similarly, a Norwegian study observed that 72% of males (108 of 150) vs 57% of females (85 of 150) had dental erosion by age 18 (p = 0.006) [

18]. This male predominance held true for advanced dentin lesions as well (though the gender difference in dentin-level cases was not statistically significant in that sample). Other surveys and reviews concur that male young adults are at higher risk for erosive tooth wear [

21,

22]. Proposed explanations include behavioral and biological factors: young men may consume acidic beverages (soft drinks, sports drinks, citrus juices) more frequently or in larger volumes, and tend to have riskier dietary habits, leading to greater acid exposure [

21,

23]. Some authors have also speculated that males’ larger muscle force (heavy chewing/grinding) and possibly thinner enamel in certain cases could exacerbate erosive wear [

18]. In contrast, females might benefit from more cautious dietary choices or protective salivary and enamel factors. Indeed, a genetic study suggested females could be less susceptible to erosion, as indicated by the consistently lower prevalence in women [

22]. Overall, the evidence strongly supports a gender difference: young males typically present with higher incidence and more severe progression of dental erosion than females, both in Romania and internationally, making gender a recognizable risk indicator in epidemiology of tooth erosion.

4.2. BEWE Index vs. 3D Scanning: Diagnostic Accuracy and Correlation

Accurate diagnosis of dental erosion can be challenging. Traditional clinical indices like the Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE) are widely used for scoring erosive wear in different sextants of the mouth. While BEWE is practical and has shown good intra- and inter-examiner reliability in general use [

24], it provides only an ordinal grading of surface loss and may underestimate subtle changes. Emerging digital techniques – notably 3D intraoral scanning with model superimposition – allow for quantitative monitoring of tooth surface loss over time. Comparing these methods reveals important differences in sensitivity and accuracy. Research has shown that 3D digital models are especially sensitive in detecting initial erosive wear that might be missed or scored as “sound” in a visual exam [

24]. In one validation study, intraoral scanner analysis could reliably detect tissue loss on the order of 50–100 µm, with around 97% accuracy when compared to micro-CT measurements [

25]. This means very early enamel erosions (such as beginning cupping or shallow faceting) register on digital overlays even if they are hard to discern clinically. Indeed, when examiners applied the BEWE scoring on digital scans versus directly in the mouth, the digital method often recorded more surfaces with erosive wear or higher BEWE scores than the clinical assessment. For example, Alaraudanjoki et al. found that erosive lesions appeared more extensive on 3D scanned models, and upper posterior tooth surfaces in particular tended to be underscored in the clinical exam [

24]. In that study, some participants who were deemed erosion-free by clinical BEWE had small lesions visible on the scans; only 6% of subjects were lesion-free on digital models versus 26% clinically [

26]. This indicates the higher sensitivity of digital detection in picking up incipient erosion.

However, the concordance (correlation) between clinical scores and digital measurements is only moderate. A recent clinical study on young adults compared BEWE scoring done intraorally to BEWE on corresponding 3D scan models. The agreement was fair-to-moderate (weighted kappa in the range 0.4–0.6), and it was poorest for molar occlusal surfaces [

26]. Interestingly, examiners often assigned higher scores on the digital models for the same tooth than they did in person, especially for the posterior teeth [

26]. The discrepancy may arise because on a screen one can enlarge and inspect the 3D model closely from all angles, detecting even tiny “cuppings” or wear facets, whereas clinically those might be overlooked or not judged as significant under standard lighting [

26]. On the other hand, digital models lack tactile feedback and subtle color changes (like enamel translucency or dentin shining through) that clinicians use to gauge depth of erosion [

26]. For instance, BEWE scoring criteria consider mainly the area of surface involved, not the depth; a very small but deep erosion into dentin still only scores 1 on BEWE if it’s under 50% of the surface [

26]. An examiner might intuitively rate such a lesion higher in severity when seeing it in person (due to visible dentin), potentially causing inconsistency with the model-based score. Thus, while digital scanning offers superior precision and the ability to monitor volumetric loss over time, it does not perfectly mirror clinical index assessments. Researchers conclude that 3D scans are an excellent adjunct for early detection and serial monitoring of erosive wear – one study noted no patient was entirely erosion-free when combining clinical and digital detection [

26] – but the BEWE index remains a convenient chairside tool for screening. The two approaches are moderately correlated; they generally identify the same individuals with heavy wear, but may differ on grading subtle lesions. In practice, using both methods in complement can improve diagnostic accuracy: the BEWE can flag patients with erosive wear risk, and intraoral scanning can document baseline lesions and quantify small changes at recalls. As digital technology advances, we may see improved software that correlates better with clinical indices or even new indices tailored for digital model analysis [

26].

Also, other authors suggested that etiological factors of erosive tooth wear should be considered and scored for differential diagnosis and risk assessment [

27,

28].

5. Conclusions

Longitudinal Erosion Rates: The Romanian 10-year study confirms that dental erosion accumulates appreciably in young adults over time, in line with global data. International longitudinal studies report substantial 5–10 year incidence of erosive wear in this age group (on the order of tens of percent), with prevalence often rising from around one-quarter in the late teens to over one-third or more by the late twenties.

Gender Differences: Males consistently show higher susceptibility to dental erosion than females. Romanian findings and worldwide evidence concur that young men experience higher incidence and greater severity of erosive tooth wear than women of similar age. Behavioral factors (e.g., more acidic drink consumption) and possible biological differences likely contribute to this male predominance.

Diagnostic Methodologies: There is a meaningful difference between clinical index scoring and digital detection of erosion. The BEWE index is practical for in vivo assessment but may underestimate early or localized erosions, whereas 3D intraoral scanning can detect and measure very initial enamel wear with high sensitivity. Studies show only moderate agreement between BEWE scores and digital measurements, implying that combining traditional and digital methods provides a more complete picture of erosive wear status.

In summary, 3D scanning offers superior accuracy in quantifying erosion progression, while BEWE remains a valuable, validated tool for quick clinical evaluation – the two should be viewed as complementary in monitoring dental erosion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.; methodology, A.B; software, A.B.; validation, M.S.; formal analysis A.B.; investigation, A.B; writing–original draft preparation, A.B; writing–review and editing, A.B; supervision, G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committee (approval No: 432/2014). All procedures followed ethical standards in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent to participate in this study was obtained from the patients.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schlueter N, Luka B. Erosive tooth wear—A review on global prevalence and on its prevalence in risk groups. Br Dent J. 2018;224(5):364-370.

- Avila V, Betlrán EO, Cortés A, Usuga-Vacca M, Castellanos Parras JE, Diaz-Baez D, Martignon S. Prevalence of erosive tooth wear and associated risk factors in Colombian adolescents. Braz Oral Res. 2024 Jun 24;38:e050.

- de la Parte-Serna, A.C.; Monticelli, F.; Pradas, F.; Lecina, M.; García-Giménez, A. Gender-Based Analysis of Oral Health Outcomes Among Elite Athletes. Sports 2025; 13:133.

- Quinchiguano Caraguay MA, Amoroso Calle EE, Idrovo Tinta TS, Gil Pozo JA. Non-carious cervical lesions (NCCL): a review of the literature. RSD [Internet]. 2023;12(5):e26612541876.

- Hasselkvist A, Arnrup K. Prevalence and progression of erosive tooth wear among children and adolescents in a Swedish county, as diagnosed by general practitioners during routine dental practice. Heliyon. 2021;7(9):e07977.

- Chan AS, Tran TTK, Hsu YH, Liu SYS, Kroon J. A systematic review of dietary acids and habits on dental erosion in adolescents. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2020;30(6):713-733.

- Kong W, Ma H, Qiao F, Xiao M, Wang L, Zhou L, Chen Y, Liu J, Wang Y, Wu L. Risk factors for noncarious cervical lesions: A case-control study. J Oral Rehabil. 2024;51(9):1684-1691.

- Methuen M, Kangasmaa H, Alaraudanjoki VK, Suominen AL, Anttonen V, Vähänikkilä H, Karjalainen P, Väistö J, Lakka T, Laitala ML. Prevalence of Erosive Tooth Wear and Associated Dietary Factors among a Group of Finnish Adolescents. Caries Res. 2022;56(5-6):477-487.

- Jász M, Szőke J. Dental Erosion and Its Relation to Potential Influencing Factors among 12-year-old Hungarian Schoolchildren. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2022 Mar 14;20:95-102.

- Piórecka B, Jamka-Kasprzyk M, Niedźwiadek A, Jagielski P, Jurczak A. Fluid Intake and the Occurrence of Erosive Tooth Wear in a Group of Healthy and Disabled Children from the Małopolska Region (Poland). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 4;20(5):4585.

- West NX, Davies M, Sculean A, Jepsen S, Faria-Almeida R, Harding M, Graziani F, Newcombe RG, Creeth JE, Herrera D. Prevalence of dentine hypersensitivity, erosive tooth wear, gingival recession and periodontal health in seven European countries. J Dent. 2024 Nov;150:105364.

- Inchingolo F, Dipalma G, Azzollini D, Trilli I, Carpentiere V, Hazballa D, Bordea IR, Palermo A, Inchingolo AD, Inchingolo AM. Advances in Preventive and Therapeutic Approaches for Dental Erosion: A Systematic Review. Dent J (Basel). 2023 Nov 29;11(12):274.

- Tapalaga G, Bumbu BA, Reddy SR, Vutukuru SD, Nalla A, Bratosin F, Fericean RM, Dumitru C, Crisan DC, Nicolae N, Luca MM. The Impact of Prenatal Vitamin D on Enamel Defects and Tooth Erosion: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023 Sep 5;15(18):3863.

- Aránguiz V, Lara JS, Marró ML, O’Toole S, Ramírez V, Bartlett D. Recommendations and guidelines for dentists using the basic erosive wear examination index (BEWE). Br Dent J. 2020 Feb;228(3):153-157.

- Bartlett DW, Ganss C, Lussi A. Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE): A new scoring system for scientific and clinical needs. Clin Oral Investig. 2008;12(Suppl 1):S65–S68.

- O’Toole S, Bartlett D, Keeling A, McBride J, Bernabe E, Crins L, Loomans B. Influence of Scanner Precision and Analysis Software in Quantifying Three-Dimensional Intraoral Changes: Two-Factor Factorial Experimental Design. J Med Internet Res. 2020 Nov 27;22(11):e17150.

- Skalsky Jarkander, M., Grindefjord M., Carlstedt K. (2018). Dental erosion: prevalence and risk factors among a group of adolescents in Stockholm County. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent, 19(1): 23–31.

- Stenhagen, K.R., Berntsen I., Ødegaard M., Mulic A., Tveit A.B. (2017). Has the prevalence and severity of dental erosion in Norwegian adolescents changed over 30 years? Eur J Paediatr Dent, 18(3): 178–184.

- Hasselkvist, A., Johansson A., Johansson A.K. (2016). A 4-year longitudinal study of progression of dental erosion in Swedish adolescents. J Dent, 47: 55–62.

- Bratu DC, Mihali SG, Popa G, Dragoş B, Bratu RC., Matichescu A., Loloș D. Boloș O. The Prevalence of Dental Erosion in Young Adults – A Quantitative Approach. Medicine in Evolution Volume XXX, No. 1, 2024.

- Jenny Bogstad Søvik, Rasa Skudutyte-Rysstad, Anne B. Tveit, Leiv Sandvik, Aida Mulic; Sour Sweets and Acidic Beverage Consumption Are Risk Indicators for Dental Erosion. Caries Res 1 May 2015; 49 (3): 243–250.

- Uhlen MM, Stenhagen KR, Dizak PM, Holme B, Mulic A, Tveit AB, Vieira AR. Genetic variation may explain why females are less susceptible to dental erosion. Eur J Oral Sci. 2016 Oct;124(5):426-432.

- Skalsky Jarkander M, Grindefjord M, Carlstedt K. Dental erosion, prevalence and risk factors among a group of adolescents in Stockholm County. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2018 Feb;19(1):23-31.

- Alaraudanjoki V, Saarela H, Pesonen R, Laitala ML, Kiviahde H, Tjäderhane L, Lussi A, Pesonen P, Anttonen V. Is a Basic Erosive Wear Examination (BEWE) reliable for recording erosive tooth wear on 3D models? J Dent. 2017 Apr;59:26-32.

- Mitrirattanakul S, Neoh SP, Chalarmchaichaloenkit J, Limthanabodi C, Trerayapiwat C, Pipatpajong N, Taechushong N, Chintavalakorn R. Accuracy of the Intraoral Scanner for Detection of Tooth Wear. Int Dent J. 2023 Feb;73(1):56-62.

- Al-Seelawi, Z.; Hermann, N.V.; Peutzfeldt, A.; Baram, S.; Bakke, M.; Sonnesen, L.; Tsakanikou, A.; Rahiotis, C.; Benetti, A.R. Clinical and digital assessment of tooth wear. Sci Rep 14, 592 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Margaritis V, Mamai-Homata E, Koletsi-Kounari H. Novel methods of balancing covariates for the assessment of dental erosion: a contribution to validation of a synthetic scoring system for erosive wear. J Dent. 2011;39:361–367.

- Margaritis V, Alaraudanjoki V, Laitala ML, Vuokko Anttonen V, Bors A, Szekely M, Alifragki P, Jász M, Berze I, Hermann P, Harding M. Multicenter study to develop and validate a risk assessment tool as part of composite scoring system for erosive tooth wear. Clin Oral Invest. 2021;25(5):2745-2756.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).