1. Introduction

The global response to the COVID-19 pandemic has relied heavily on mass vaccination campaigns, most prominently with mRNA-based vaccines [

1]. These vaccines have demonstrated robust efficacy in preventing severe disease and reducing transmission, primarily through the induction of both humoral and cellular immune responses [

2,

3]. However, real-world data and follow-up studies have increasingly highlighted the heterogeneity of immune responses among vaccinated individuals[

4].

Immunological protection against SARS-CoV-2 involves two interrelated but distinct components: humoral immunity, primarily mediated by neutralizing antibodies such as IgG, and cellular immunity, which involves T-cell responses targeting viral antigens. While antibody titers are easily measurable and have become the standard marker for assessing post-vaccination immunity [

5], they are known to decline over time, often dropping below detectable levels within months of vaccination [

6]. In contrast, T-cell responses are typically more durable and play a vital role in long-term immunity, particularly in reducing disease severity upon viral exposure [

7].

Despite widespread recognition of this dual-arm immune architecture, current vaccination monitoring practices often neglect cellular immunity [

8,

9,

10]. Notably, a negative antibody result is frequently used as the sole criterion for assessing immune protection or determining the need for additional vaccine doses, potentially misclassifying individuals who possess protective cellular responses [

11].

Moreover, the kinetics of the T-cell response following vaccination remain less well defined, particularly in antibody non-responders after vaccination. While studies have shown that T-cell responses typically emerge within 1–2 weeks and up to one month post-vaccination in immunocompetent individuals [

12], this timeline may differ in those with impaired or delayed humoral responses [

13]. It remains unclear whether cellular immunity in these individuals is merely delayed, entirely absent, or uncoupled from the antibody response.

This study addresses this knowledge gap by examining the development of cellular immunity in a cohort of vaccinated, COVID-19-naïve individuals who were tested for T-cell response using the ELISpot interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA) methodology. We specifically focused on those individuals who tested negative for SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG at the time of examination. Building upon our previous study [

14], which showed that SARS-CoV-2–vaccinated individuals who were IgG seronegative exhibited lower levels of T-cell responses compared to seropositive individuals, the present study aimed to compare T-cell responses at different time points post-vaccination to determine whether cellular responses in IgG-negative individuals follow a delayed kinetic pattern. Understanding these dynamics could enhance post-vaccination immune profiling, guide the optimal timing for follow-up testing, and inform decisions regarding booster administration—particularly in populations at risk of being misclassified based solely on antibody status.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

A retrospective, descriptive analysis was carried out using data obtained from electronic medical records of adult individuals who visited the “BIOIATRIKI” Healthcare Center—a major medical facility in Attica—between September 2021 and September 2022. These individuals sought SARS-CoV-2 immunity testing on their own initiative during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study included adults who were fully vaccinated and had no prior exposure to COVID-19. The participants were divided into two groups based on their SARS-CoV-2 IgG levels at the time of testing: those with a positive (≥50 AU/ml) and those with a negative IgG measurement (≥50 AU/ml).

Eligibility criteria required participants to be free of current or past COVID-19 symptoms, have no known contact with confirmed COVID-19 cases, and no prior diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection before vaccination, as verified by PCR tests, rapid antigen tests, self-tests, or IgG/IgM antibody assessments. Only individuals who had completed their primary vaccination regimen without receiving any booster doses at the time of testing were considered. Individuals with known immunocompromised status were excluded from the study.

The date marking the completion of primary vaccination (either the first or second dose, depending on vaccine type) was recorded as the individual’s vaccination date. Additional demographic and medical history data were gathered through structured questionnaires routinely administered at the time of examination. Although the specific vaccine type administered was not documented for each participant, mRNA vaccines were widely available in Greece during the study period.

The study protocol received ethical approval from the institution’s review board on June 29, 2021 (6th Annual Meeting).

2.2. Laboratory Procedures

2.2.1. ELISpot Assay for Detection of IFN-γ T-cell Responses

To evaluate T-cell-mediated immune response to SARS-CoV-2, the T-SPOT®.COVID test (Oxford Immunotec, UK) was used. This assay, based on the ELISpot platform, detects T-cell responses by measuring the release of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) in response to SARS-CoV-2 antigens, specifically spike (S) and nucleocapsid (N) proteins. Blood samples were collected in lithium heparin tubes and treated with T-cell Xtend reagent. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated, washed, counted, and plated into a 96-well plate at approximately 250,000 cells per well. Antigen peptide pools targeting the S and N proteins were added to two separate wells. A mitogen (phytohemagglutinin) was used as a positive control, while cell culture medium alone served as the negative control. After an incubation period of 16–20 hours, wells were washed and treated with a conjugated secondary antibody that binds to IFN-γ. Unbound components were removed through additional washing, and a substrate was introduced to visualize IFN-γ secretion as dark spots, which were manually counted under a microscope by trained personnel. Results were assessed separately for responses to the S and N antigens. A test result was deemed invalid if the negative control exhibited more than 10 spot-forming cells (SFCs) or if the positive control yielded fewer than 20 SFCs and the antigen wells showed no reactivity. The predefined threshold for a positive response was 6 SFCs. A borderline range of ±1 SFC (i.e., 5–7 SFCs) was established to account for assay variability. Based on these criteria, results were classified as reactive (≥8 SFCs), non-reactive (≤4 SFCs), or borderline (5–7 SFCs) for the respective antigens.

2.2.2. Measurement of SARS-CoV-2 IgG Antibodies

Quantification of SARS-CoV-2-specific IgG antibodies was conducted using the SARS-CoV-2 IgG II Quant assay developed by Abbott Laboratories. This is a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) performed on the Alinity i system. It detects and quantifies IgG antibodies targeting the receptor binding domain (RBD) of the S1 subunit of the spike protein, using sequences from the WH-Human 1 coronavirus (GenBank accession MN908947). Blood serum samples were analyzed on the same day of examination. The assay reports results within an analytical range of 21 to 40,000 arbitrary units per milliliter (AU/mL), with a positivity threshold set at ≥50 AU/mL, according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

We performed an initial cutoff analysis across all distinct post-vaccination time points in our dataset (100 cutoffs from 14 to 364 days) separately within the IgG-negative and IgG-positive cohorts. At each cutoff, participants were dichotomized into “early” (≤ cutoff) and “late” (> cutoff) groups. For the continuous S-antigen levels we applied the Wilcoxon rank-sum (U) test, and for the binary S-antigen positivity outcomes we used Pearson’s chi-square test (with no Yates correction). This exploratory scan highlighted a region of particular interest between 60 and 150 days after vaccination.

To rigorously assess significance within this window while accounting for multiple testing, we then carried out a permutation-based adjustment on just the 29 available cutoffs (days of post vaccination testing, in the dataset) between 60 and 150 days. In each of 10 000 permutations, we randomly shuffled the S-antigen positivity labels among subjects, re-ran the series of 29 chi-square tests, and recorded the minimum p-value observed in that permutation. The permutation-adjusted p-value was defined as the fraction of permutations in which the permuted minimum p-value was at least as small as the observed minimum.

All statistical analyses were conducted in R (version 4.4.0). Parallel computation via the Parallel package was used to expedite the 10 000 permutations. Throughout, two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A cohort of 262 individuals, comprising 148 females (56.5%) and 114 males (43.5%), with ages ranging from 17 to 92 years (mean age: 59.47 ± 15.5 years), were included in this study. Participants’ demographic characteristics are presented in

Table 1. Individuals were divided into two groups: individuals with a positive (≥50 AU/ml) on the day of testing and those with a negative SARS-CoV-2 IgG result (<50 AU/ml). The IgG negative group was larger (216/262), since a negative humoral immunity measurement was the primary reason for ordering a follow-up T-cell immunity test to verify whether vaccination had successfully induced at least one form of SARS-CoV-2 immunity. Both T-SPOT positivity rates and levels were significantly different between the two groups (U test, p<0.01) (

Table 2). Days elapsed since vaccination, sex, and age did not differ significantly between the groups.

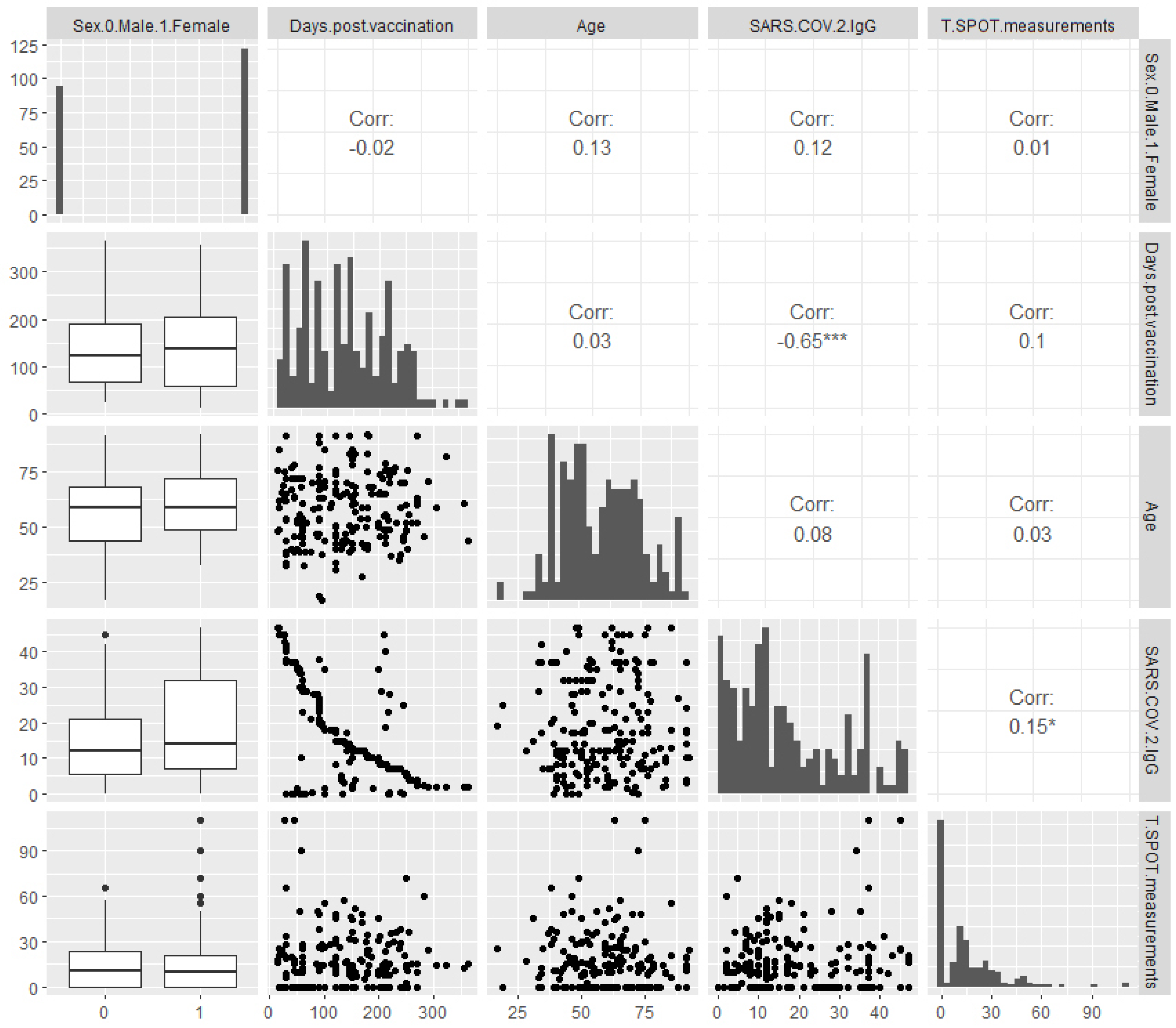

In the IgG-negative group, detailed pairwise plots revealed a moderate yet highly significant negative correlation between SARS-CoV-2 IgG levels and days since vaccination (Spearman ρ=–0.65, p<0.001) (

Figure 1). Although IgG levels in this group were below the protective threshold, this finding aligns with the well-documented time-dependent decline in IgG reported in the literature. In contrast, no significant correlation was found between T-SPOT measurements and days since vaccination (Spearman ρ=0.1, p>0.05), suggesting that T-cell immunity was either stable over time or independent of time. A weak positive correlation between IgG and T-SPOT measurements was observed (Spearman ρ=0.15, p<0.05), indicating a modest interaction between humoral and cellular immunity.

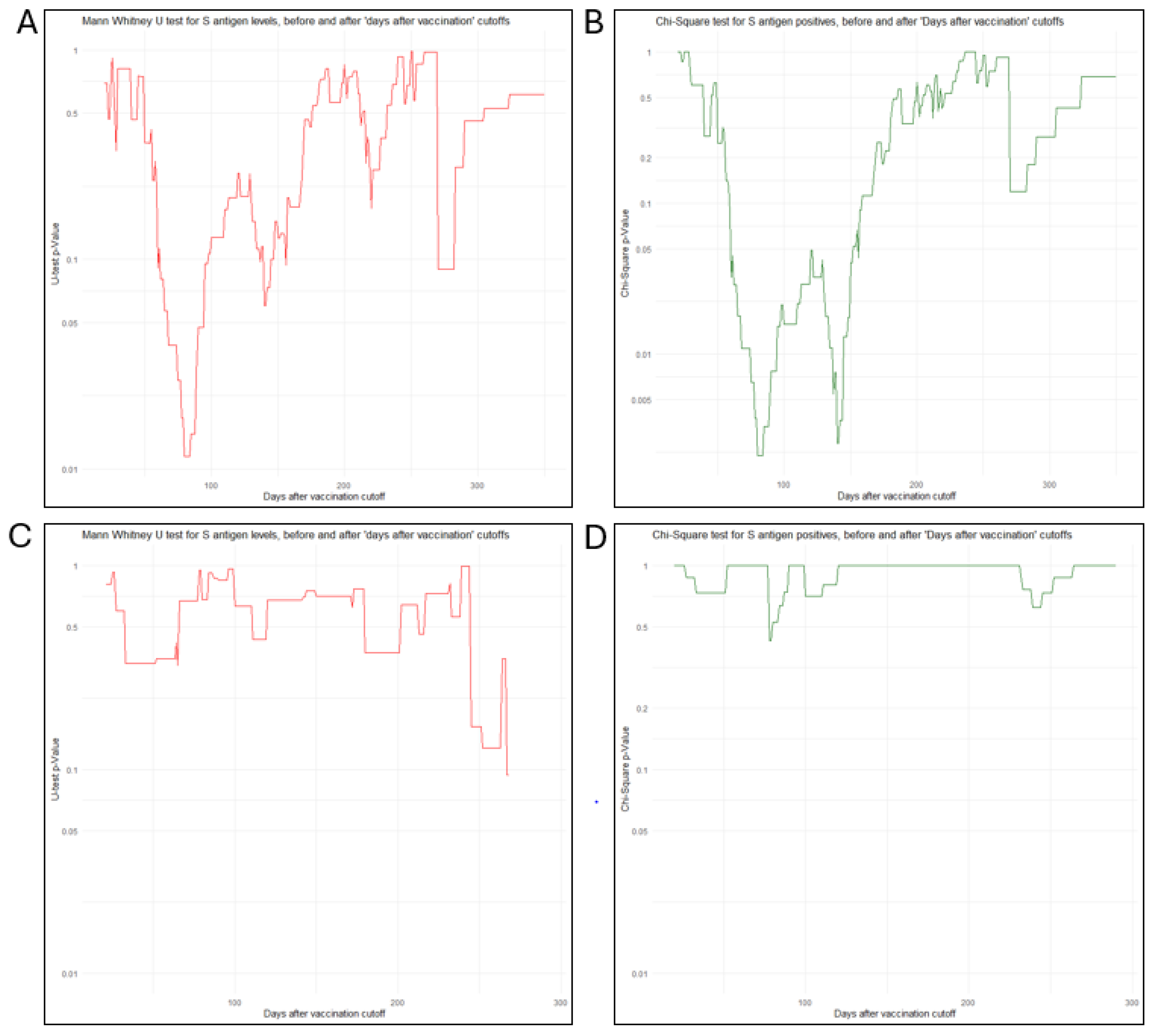

To investigate the temporal impact on the development of cellular immunity and T-SPOT measurements in individuals lacking protective IgG levels after vaccination, we performed a comprehensive cutoff analysis using 1-day intervals. This analysis involved statistical comparisons of T-SPOT measurements and positivity rates on either side of each cutoff point, tracking p-value trends (

Figure 2). For T-SPOT measurements in the IgG-negative group, consecutive U-tests revealed a significant difference between subgroups formed before and after time cutoffs between 68 and 94 days. Within this window, the «late» subgroup (formed after each cutoff) consistently showed significantly higher T-SPOT measurements. The strongest significance (i.e., the lowest p-value) was observed at 80 days (U test, p=0.011), suggesting a potential critical time point.

For T-SPOT positivity rates in the IgG-negative group, consecutive chi-square tests revealed a broader window of significance between 60 and 150 days, with two distinct p-value minima at 80 days (χ²(1), N=216, p=0.0013) and 140 days (χ²(1), N=216, p=0.0016). At all-time points within this range, the subgroup formed after each cutoff consistently showed a significantly higher positivity rate. Permutation analysis, as described in the Methods section for the time window between 60 and 150 days, yielded an adjusted p= 0.0082. Since this value is well above the p-values of the two observed minima, both cutoffs were retained as significant time points for post-vaccination T-SPOT positivity rates in the IgG-negative group.

Table 3. highlights the 80-day time point, which emerged as highly significant in relation to T-SPOT measurements and positivity rate analyses among IgG seronegative individuals. In the IgG-positive group, the same cutoff analysis did not reveal any significant time points, suggesting that T-cell immunity in this group was established early post-vaccination and remained stable throughout the study period (14–364 days).

4. Discussion

In our study, we observed that individuals who did not develop detectable antibodies after COVID-19 vaccination exhibited a delayed onset of cellular immune responses. In the IgG-positive group, T-cell responses appear to have been established early—consistent with previous reports indicating that robust T-cellular immunity develops as early as 1–2 weeks after a two-dose vaccination regimen [

15,

16,

17], and mostly within one month [

18,

19]. In contrast, our IgG-negative cohort exhibited a delayed pattern of cellular immunity. Specifically, T-cell response levels in these individuals were significantly lower before 68 days post-vaccination but increased markedly thereafter, with both positivity rate and quantitative levels peaking at 80 days.

Several mechanisms may underlie this delayed development in the IgG-negative group according to current literature. Firstly, it is possible that a subset of individuals who fail to mount a humoral response initially—due to factors such as underlying B-cell dysfunction or other immunological constraints [

20,

21,

22,

23]—also experience a slower maturation of cellular immunity. This finding aligns with literature on immunocompromised patients—for example, those on B-cell–depleting therapies—where robust SARS-CoV-2–specific T-cell responses are detected only several weeks after vaccination [

24]. Furthermore, intrinsic variability in immune responsiveness—driven by genetic polymorphisms affecting antigen presentation, T-cell receptor diversity, and cytokine signaling—can influence the efficiency of cellular immunity [

25]. Age-related immunosenescence may also play a role, even in individuals without overt immunosuppression, by impairing both humoral and cellular responses [

26]. Suboptimal antigen presentation, possibly due to inadequate dendritic cell activation or insufficient vaccine-induced priming, can delay T-cell engagement [

27]. Additionally, host genetic background, including HLA type, along with epigenetic modifications, can further affect the timing and strength of T-cell responses [

28]. Other contributing factors include variability in vaccine uptake or antigen expression and epigenetic influences on T-cell activation [

29]. These diverse biological and immunological factors likely contribute to the heterogeneity in cellular immune responses observed post-vaccination. It is, in any case, noteworthy that a delayed induction and a lower frequency of SARS-CoV-2-specific CD8+ T-cells have been associated with severe cases of COVID-19 [

30], which prompts for an investigation of possible common mechanisms involved in COVID-19 naïve individuals with similar T-cell profiles after complete vaccination.

On the other hand, while individuals who initially develop protective levels of IgG are most likely to be classified into the IgG-positive group, those tested at later intervals (e.g., after 4 months post-vaccination) may be falsely classified as IgG negative due to a significant drop in IgG levels by the time of testing. This interpretation is supported by systematic reviews indicating that although antibody levels may diminish by over 75% at five months post-vaccination [

31], T-cell responses tend to be more stable [

32,

33]. Therefore, as these individuals are expected to have mounted an initial T-cell response within the usual timeframe of 1–4 weeks, their classification as IgG negative may be contributing to the observation of an increased T-cell response rate in the later time window.

Our cutoff analysis of T-SPOT responses rates in the IgG-negative group revealed a continuous window of significance between 60 and 150 days, with distinct minima at 80 and 140 days. We interpret the minimum at 80 days as indicating the peak in the magnitude of the T-cell response. In contrast, the second minimum at 140 days may not represent an additional increase in T-cell response per se but rather a change in the composition of the IgG-negative cohort, as argued above. This interpretation is strongly supported by the cutoff analysis of S-antigen quantitative measurements, which revealed only one significant minimum at 80 days. This suggests that once a robust T-cell response is established, its magnitude remains relatively stable over the subsequent period, up to 140 days and beyond—even if the proportion of IgG negative individuals categorized as T-cell responders increases due to waning IgG levels in those who initially developed both arms of immunity. This stability in cellular immunity aligns with longitudinal studies indicating that T-cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 remain durable for at least 6 months post-vaccination, despite marked declines in antibody titers [

34].

In summary, our cross-sectional data indicate that among IgG-negative individuals, T-cell response is more frequently detected at later time points post-vaccination. While some individuals tested within 80 days of vaccination may have failed to mount a sufficient response in both the humoral and cellular compartments, those tested later may include individuals who either developed T cell responses later than expected or initially generated both IgG and T cell responses, but subsequently showed a decline in antibody levels. Notably, the 80-day time point consistently emerged as a critical juncture in our analyses, marking the peak of T-cell response in the IgG-negative group. This finding suggests that assessing T-cell responses beyond 80 days post-vaccination may offer a more accurate evaluation of vaccine-induced immunity, potentially guiding recommendations for optimal timing of post-vaccination testing.

A key strength and novel contribution of this study is its focus on a well-defined population: individuals with no prior history of COVID-19 infection who received a complete primary immunization schedule, the majority of whom received two doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine. By excluding participants with prior SARS-CoV-2 exposure and limiting the analysis to those who had not received additional booster doses, this study provides a clearer view of the immune response—particularly cellular immunity—induced by primary vaccination alone. This controlled context allows us to more accurately examine the natural trajectory and timing of T-cell responses in seronegative individuals, without the confounding effects of infection-induced or booster-amplified immunity.

However, there are also certain limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the study’s cross-sectional design captures immune responses at a single time point per individual, which limits our ability to track the true kinetics of humoral and cellular immunity over time. Longitudinal follow-up would be required to confirm the temporal patterns suggested by our cutoff analysis. In addition, the classification of individuals as IgG-negative may include those who had previously mounted an antibody response but experienced rapid waning, introducing heterogeneity into this group.

5. Conclusions

The assessment of cellular immunity plays a crucial role in understanding immune protection against SARS-CoV-2, especially in individuals who do not develop detectable antibody responses after vaccination. Our results support the inclusion of cellular assays in post-vaccination monitoring and emphasize the need to reconsider the timing and criteria for evaluating vaccine response. Although interpreting cellular immunity results remains complex due to methodological challenges and individual variability, incorporating such measurements is essential for a more comprehensive evaluation of vaccine-induced immunity and long-term protection. Further longitudinal studies are warranted to validate these observations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.C.P., D.N.; Formal analysis, V.C.P., D.N., K.E.K. and I.V.V.; Investigation, K.E.K., N.I.S., I.V.V. and C.S.; Methodology, D.N. V.C.P. A.D.K. and C.S.; Supervision,V.C.P., A.T.; Validation, V.C.P.,; Writing—original draft, V.C.P., D.N. Writing—review and editing, V.C.P., A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the institutional review board (9 June 2021, 6th Scientific Board of Bioiatriki).

Informed Consent Statement

clinia

Data Availability Statement

All data from this study are included in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Dimitris Nikoloudis, Kanella E. Konstantinakou, and Irene V. Vasileiou are employed by Bioiatriki Healthcare Group. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yang ZR, Jiang YW, Li FX, Liu D, Lin TF, Zhao ZY, et al. Efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and the dose-response relationship with three major antibodies: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lancet Microbe. 2023 Apr;4(4):e236-e246. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Szabó GT, Mahiny AJ, Vlatkovic I. COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: Platforms and current developments. Mol Ther. 2022 May 4;30(5):1850-1868. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mirtaleb MS, Falak R, Heshmatnia J, Bakhshandeh B, Taheri RA, Soleimanjahi H, et al. An insight overview on COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: Advantageous, pharmacology, mechanism of action, and prospective considerations. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023 Apr;117:109934. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ciabattini A, Pettini E, Fiorino F, Polvere J, Lucchesi S, Coppola C, et al. Longitudinal immunogenicity cohort study of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines across individuals with different immunocompromising conditions: heterogeneity in the immune response and crucial role of Omicron-adapted booster doses. EBioMedicine. 2025 Mar;113:105577. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kumar, A.; Tripathi, P.; Kumar, P.; Shekhar, R.; Pathak, R. From Detection to Protection: Antibodies and Their Crucial Role in Diagnosing and Combatting SARS-CoV-2. Vaccines 2024, 12, 459. [CrossRef]

- Đaković Rode O, Bodulić K, Zember S, Cetinić Balent N, Novokmet A, Čulo M, et al. Decline of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG Antibody Levels 6 Months after Complete BNT162b2 Vaccination in Healthcare Workers to Levels Observed Following the First Vaccine Dose. Vaccines (Basel). 2022 Jan 20;10(2):153. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pitiriga VC, Papamentzelopoulou M, Konstantinakou KE, Vasileiou IV, Konstantinidis AD, Spyrou NI, et al. Prolonged SARS-CoV-2 T-cell Responses in a Vaccinated COVID-19-Naive Population. Vaccines (Basel). 2024 Mar 4;12(3):270. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Erra L, Uriarte I, Colado A, Paolini MV, Seminario G, Fernández JB, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Responses with Different Vaccine Platforms in Patients with Inborn Errors of Immunity. J Clin Immunol. 2023 Feb;43(2):271-285. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chang-Rabley E, van Zelm MC, Ricotta EE, Edwards ESJ. An Overview of the Strategies to Boost SARS-CoV-2-Specific Immunity in People with Inborn Errors of Immunity. Vaccines (Basel). 2024 Jun 18;12(6):675. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stoddard, M.; Yuan, L.; Sarkar, S.; Mangalaganesh, S.; Nolan, R.P.; Bottino, et al, A. Heterogeneity in Vaccinal Immunity to SARS-CoV-2 Can Be Addressed by a Personalized Booster Strategy. Vaccines 2023, 11, 806. [CrossRef]

- Pitiriga, V.C.; Papamentzelopoulou, M.; Konstantinakou, K.E.; Theodoridou, K.; Vasileiou, I.V.; Tsakris, A. SARS-CoV-2 T-cell Immunity Responses following Natural Infection and Vaccination. Vaccines 2023,11,1186. [CrossRef]

- Folegatti PM, Ewer KJ, Aley PK, Angus B, Becker S, Belij-Rammerstorfer S, et al; Oxford COVID Vaccine Trial Group. Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Aug 15;396(10249):467-478. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Aug 15;396(10249):466. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31687-1. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 Dec 12;396(10266):1884. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32597-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Paniskaki, K.; Anft, M.; Meister, T.L.; Marheinecke, C.; Pfaender, S.; Skrzypczyk, S.; et al. Immune Response in Moderate to Critical Breakthrough COVID-19 Infection After mRNA Vaccination. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 816220.

- Pitiriga, V.C.; Papamentzelopoulou, M.; Nikoloudis, D.; Saldari, C.; Konstantinakou, K.E.; Vasileiou, I.V.; et al. Evaluating SARS-CoV-2 T-cell Immunity in COVID-19-Naive Vaccinated Individuals with and Without Spike Protein IgG Antibodies. Pathogens 2025, 14, 415. [CrossRef]

- Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, Jackson LA, Roberts PC, Makhene M, et al; mRNA-1273 Study Group. Safety and Immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 Vaccine in Older Adults. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 17;383(25):2427-2438. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sahin U, Muik A, Derhovanessian E, Vogler I, Kranz LM, Vormehr M, et al. COVID-19 vaccine BNT162b1 elicits human antibody and TH1 T-cell responses. Nature. 2020 Oct;586(7830):594-599. Erratum in: Nature. 2021 Feb;590(7844):E17. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03102-w. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi JS, Fukunaga A, Yamamoto S, Tanaka A, Matsuda K, Kimura M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 specific T-cell and humoral immune responses upon vaccination with BNT162b2: a 9 months longitudinal study. Sci Rep. 2022 Sep 14;12(1):15447. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tarke, A.; Coelho, C.H.; Zhang, Z.; Dan, J.M.; Yu, E.D.; Methot, N.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccination induces immunological T-cell memory able to cross-recognize variants from Alpha to Omicron. Cell 2022, 185, 847–859.e11.

- Geurtsvan Kessel, C.H.; Geers, D.; Schmitz, K.S.; Mykytyn, A.Z.; Lamers, M.M.; Bogers, S.; et al. Divergent SARS-CoV-2 Omicron-reactive T and B cell responses in COVID-19 vaccine recipients. Sci. Immunol. 2022, 7, eabo2202.

- Gallais, F., Velay, A., Nazon, C., et al. Intrafamilial Exposure to SARS-CoV-2 Associated with Cellular Immune Response without Seroconversion, France. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 27(1), 113–121 (2021).

- Bacher P, Rosati E, Esser D, Martini GR, Saggau C, Schiminsky E, et al. Low-Avidity CD4+ T-cell Responses to SARS-CoV-2 in Unexposed Individuals and Humans with Severe COVID-19. Immunity. 2020 Dec 15;53(6):1258-1271.e5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Marasco V, Carniti C, Guidetti A, Farina L, Magni M, Miceli R, et al. T-cell immune response after mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccines is frequently detected also in the absence of seroconversion in patients with lymphoid malignancies. Br J Haematol. 2022 Feb;196(3):548-558. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jay C, Ratcliff J, Turtle L, Goulder P, Klenerman P. Exposed seronegative: Cellular immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in the absence of seroconversion. Front Immunol. 2023 Jan 26;14:1092910. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Apostolidis SA, Kakara M, Painter MM, Goel RR, Mathew D, Lenzi K, et al. Cellular and humoral immune responses following SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in patients with multiple sclerosis on anti-CD20 therapy. Nat Med. 2021 Nov;27(11):1990-2001. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hoang Nguyen KH, Le NV, Nguyen PH, Nguyen HHT, Hoang DM, Huynh CD. Human immune system: Exploring diversity across individuals and populations. Heliyon. 2025 Jan 13;11(2):e41836. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schwarz T, Tober-Lau P, Hillus D, Helbig ET, Lippert LJ, Thibeault C, et al. Delayed Antibody and T-Cell Response to BNT162b2 Vaccination in the Elderly, Germany. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021 Aug;27(8):2174-2178. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shi Y, Lu Y, You J. Antigen transfer and its effect on vaccine-induced immune amplification and tolerance. Theranostics. 2022 Aug 1;12(13):5888-5913. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative. The COVID-19 Host Genetics Initiative, a global initiative to elucidate the role of host genetic factors in susceptibility and severity of the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic. Eur J Hum Genet. 2020 Jun;28(6):715-718. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pathak GA, Singh K, Miller-Fleming TW, Wendt FR, Ehsan N, Hou K, et al. Integrative genomic analyses identify susceptibility genes underlying COVID-19 hospitalization. Nat Commun. 2021 Jul 27;12(1):4569. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Karl V, Hofmann M, Thimme R. Role of antiviral CD8+ T-cell immunity to SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination. J Virol. 2025 Apr 15;99(4):e0135024. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Notarte KI, Guerrero-Arguero I, Velasco JV, Ver AT, Santos de Oliveira MH, Catahay JA, et al. Characterization of the significant decline in humoral immune response six months post-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination: A systematic review. J Med Virol. 2022 Jul;94(7):2939-2961. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Goel RR, Painter MM, Apostolidis SA, Mathew D, Meng W, Rosenfeld AM, et al. mRNA vaccines induce durable immune memory to SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern. Science. 2021 Dec 3;374(6572):abm0829. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tarke A, Sidney J, Methot N, Yu ED, Zhang Y, Dan JM, et al. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 variants on the total CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell reactivity in infected or vaccinated individuals. Cell Rep Med. 2021 Jul 20;2(7):100355. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Pitiriga, V.C.; Papamentzelopoulou, M.; Konstantinakou, K.E.; Vasileiou, I.V.; Konstantinidis, A.D.; Spyrou, N.I.; Tsakris, A. Prolonged SARS-CoV-2 T-cell Responses in a Vaccinated COVID-19-Naive Population. Vaccines 2024, 12, 270. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).