1. Introduction

The capacity to comprehend and anticipate the outcomes of deliberate actions constitutes a fundamental element of human cognition. This faculty allows individuals to envision whether a sequence of events will culminate in an intended objective, elucidate past occurrences by inferring plausible action chains, and diagnose failures by tracing the sequence of actions that precipitated an adverse state [

2]. As artificial intelligence systems become increasingly embedded in everyday settings, these agents must acquire parallel competencies to navigate and manipulate complex physical and social contexts effectively. For instance, as articulated by Davis and Marcus [

4], if a robot tasked with serving wine discerns that the offered glass is either fractured or contaminated, it should intuitively refrain from fulfilling the request. Similarly, in scenarios where a domestic cleaning agent encounters obstacles, such as a cat darting across its path, the agent must exercise restraint, neither causing harm nor mismanaging the object. These illustrative examples accentuate the criticality of robust action-effect reasoning mechanisms within artificial agents.

Historically, Reasoning about Actions and Change (RAC) has been heralded as a central research agenda since the formative years of AI. The pioneering work of McCarthy et al. [

9] laid the intellectual groundwork by conceptualizing systems capable of deductive reasoning over sequences of actions, exemplified through scenarios like journey planning from home to the airport by aggregating micro-actions such as walking and driving. Subsequently, the breadth of RAC applications has expanded, permeating domains ranging from robotic planning to fault diagnosis, necessitating sophisticated modeling of state transitions and the interactive dynamics of agents with their environments [

1].

While the RAC paradigm was predominantly nurtured within the knowledge representation and logical reasoning communities, contemporary advancements have spurred burgeoning interest among NLP and computer vision researchers. This interdisciplinary shift has been systematically chronicled in the survey by Sampat et al. [

13], which cataloged a wealth of studies probing neural models’ capacity to reason about actions and their aftermath when supplied with visual and/or linguistic stimuli. Salient among these are the contributions of Park et al. [

10], Sampat et al. [

12], Shridhar et al. [

14], Yang et al. [

17], Gao et al. [

5], Patel et al. [

11], whose works exemplify the diverse approaches adopted in this nascent yet rapidly evolving field.

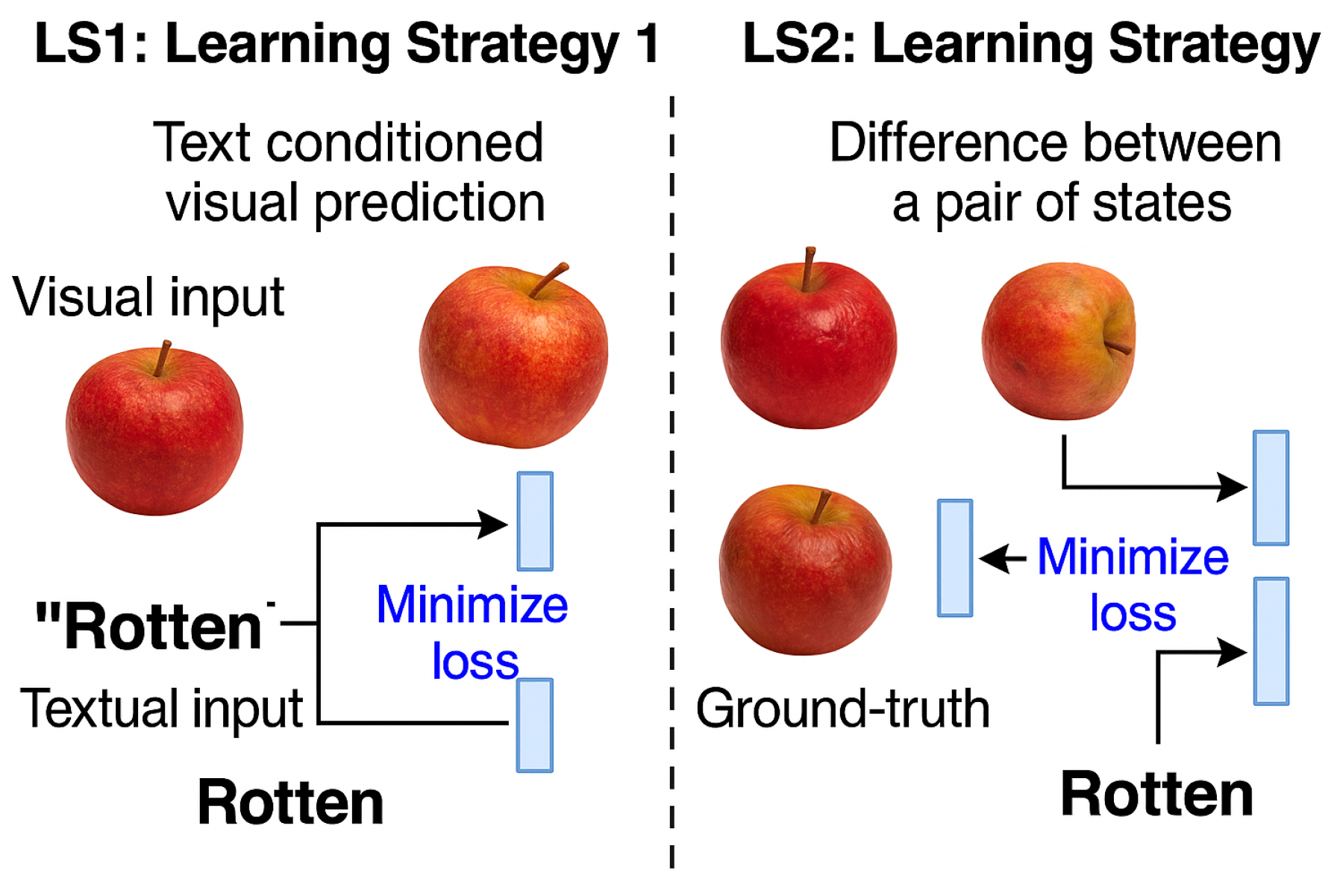

Figure 1.

Existing methods for learning paradigm, and our proposed method.

Figure 1.

Existing methods for learning paradigm, and our proposed method.

Within this contextual backdrop, we critically reexamine prevailing methodologies for action-effect modeling, which predominantly follow an intuitive paradigm wherein raw visual features extracted from images are amalgamated with embedded action descriptions to simulate possible outcomes. However, through rigorous introspection, we contend that such approaches, herein referred to as the conventional LS1 strategy, may inadequately encapsulate the differential nuances that characterize the true effects of actions. Rather than implicitly expecting the model to infer such effects from static representations, our proposed DEAR framework introduces an explicit comparative mechanism wherein the agent observes and encodes state alterations via juxtaposed scene-graphs depicting pre-action and post-action conditions.

More precisely, DEAR capitalizes on extracting relational deltas, effectively highlighting distinctions such as the emergence of decay in an apple following the action of rotting. By establishing direct associations between these observed deltas and the corresponding linguistic action descriptors (e.g., “rotten”), the agent fosters a more grounded and interpretable internal representation of action-effect dynamics. This structured comparative approach, we argue, is poised to amplify the agent’s reasoning acuity, rendering it more adept at discerning causality and generalizing to unfamiliar scenarios where nuanced state shifts are critical indicators of action outcomes.

In subsequent sections, we will systematically articulate the architectural intricacies underpinning DEAR, delineate its operational mechanics through mathematical formalization, and present empirical assessments substantiating its superiority over LS1-based models. Our experiments on the CLEVR_HYP [

12] benchmark underscore DEAR’s efficacy across multiple metrics, heralding it as a promising foundation for advancing action-effect reasoning in visually grounded AI systems.

2. Related Work

2.1. Reasoning About Actions and Change

Reasoning about Actions and Change (RAC) has been a foundational topic in artificial intelligence, deeply rooted in classical knowledge representation and logical reasoning traditions. Early works such as McCarthy et al. [

9] established the necessity for systems capable of modeling and deducing the consequences of actions in dynamic worlds. The seminal contributions in this domain focused on developing formalisms like the Situation Calculus and the Event Calculus, which provided declarative representations of how actions alter the state of the world. These frameworks facilitated deductive reasoning and planning, enabling agents to model hypothetical sequences of actions to achieve desired goals.

In the realm of commonsense reasoning, Davis and Marcus [

4] emphasized the crucial role of action reasoning in enabling AI systems to navigate the intricacies of everyday environments where explicit programming is insufficient. The ability to reason about preconditions, effects, and ramifications of actions was identified as an indispensable competence for agents operating in open-world settings.

Recent years have witnessed a growing interest in extending RAC paradigms into data-driven domains, leveraging advancements in deep learning to learn action-effect dynamics from visual and linguistic observations. Banerjee et al. [

1] explored neural approaches for modeling transitions in structured environments, while Park et al. [

10] pioneered the task of generating commonsense consequences of visual events using pretrained language models, thereby bridging symbolic RAC traditions with modern neural architectures.

2.2. Scene Graph-Based Visual Reasoning

Scene graphs have emerged as a powerful intermediate representation that encapsulates the semantic structure of visual scenes by modeling objects, their attributes, and inter-object relationships. This structured abstraction has been extensively employed in visual reasoning tasks, including Visual Question Answering (VQA) [

18], visual captioning, and object-centric representation learning.

In the context of action-effect reasoning, Sampat et al. [

12] introduced CLEVR_HYP, a synthetic dataset designed to study the reasoning capabilities of models in scenarios where actions modify the scene’s state. Their work demonstrated the viability of leveraging scene-graph representations to facilitate interpretable action-effect modeling and highlighted the limitations of existing models that predominantly rely on direct visual-linguistic feature fusion.

Building upon this trajectory, Chen et al. [

3] proposed graph-editing networks capable of simulating the transformations induced by actions on scene-graphs, framing action reasoning as a graph manipulation task. Such approaches underline the potential of scene-graph-centric models to serve as transparent and structured reasoning substrates, capable of generalizing across diverse action types and complex scenes.

2.3. Neuro-Symbolic Reasoning Approaches

The intersection of neural networks and symbolic reasoning has gained significant momentum as a promising paradigm for combining the scalability and perceptual prowess of deep learning with the interpretability and systematic reasoning capabilities of symbolic systems. Neuro-symbolic models such as those proposed by Yi et al. [

18] have demonstrated impressive capabilities in executing complex reasoning over structured representations like scene-graphs, achieving near-human performance on benchmarks such as CLEVR [

8].

These methods leverage neural modules to parse visual inputs into structured scene-graphs, followed by symbolic program execution over these graphs to answer compositional questions. While effective in static reasoning scenarios, these approaches often assume fully observable and static environments, lacking mechanisms to model dynamic changes induced by actions.

Our proposed DEAR framework aligns with this line of work by adopting scene-graphs as a reasoning substrate but extends these paradigms by explicitly modeling state transitions and action-induced graph transformations, thereby enabling dynamic reasoning capabilities that are absent in purely neuro-symbolic models.

2.4. Language-Vision Grounded Reasoning

Recent advances in multimodal AI have yielded significant progress in developing models capable of jointly reasoning over visual and linguistic modalities. Pretrained vision-language transformers such as LXMERT [

15], ViLBERT, and VisualBERT have achieved state-of-the-art performance on various downstream tasks by learning cross-modal representations over large-scale image-text corpora.

These models, however, are primarily optimized for tasks such as Visual Question Answering (VQA) and Visual Commonsense Reasoning (VCR), where the input scene remains static, and the reasoning revolves around inferring latent knowledge from the given scene. They lack explicit mechanisms to model and simulate how actions modify the state of the environment, which is critical for action-effect reasoning.

Vo et al. [

16] explored text-conditioned image editing, where models learn to synthesize modified images based on action descriptions. While such approaches enable implicit modeling of action effects, they often struggle with compositional generalization and lack interpretability due to their reliance on dense feature manipulations.

Our work builds upon these insights but diverges by introducing explicit state differential learning via paired scene-graphs, thereby promoting interpretability and facilitating compositional reasoning about actions and their consequences in a structured and disentangled manner.

Bridging the Gaps.

Despite the advancements across these domains, a unified approach that holistically integrates scene-graph-based reasoning, neuro-symbolic program execution, and language-guided action-effect modeling remains underexplored. Our DEAR framework seeks to bridge these gaps by introducing a novel differential effect-aware reasoning paradigm that synergistically combines the strengths of structured scene-graph representations, neural language-action alignment, and graph-editing mechanisms. By doing so, we aim to advance the frontiers of action reasoning and establish a robust foundation for developing agents capable of performing dynamic, interpretable, and compositional reasoning in complex visual environments.

Figure 2.

Overview of the overall framework.

Figure 2.

Overview of the overall framework.

3. Proposed Differential Effect-Aware Reasoner Framework

In this section, we elaborate on the comprehensive architecture of our proposed Differential Effect-Aware Reasoner (DEAR), meticulously designed to enhance action-effect reasoning by leveraging paired scene-graph differentials. Our central hypothesis postulates that by exposing the model to explicit visual differences between pre-action and post-action states, and aligning these deltas with natural language action descriptions, the model can develop a more grounded and interpretable representation of action semantics.

To systematically model this paradigm, DEAR comprises a meticulously engineered three-stage pipeline, each addressing a critical subtask that cumulatively facilitates robust action-effect comprehension and reasoning.

3.1. Stage-1: State Differential Encoder-Decoder Module

The initial stage of DEAR architecture is dedicated to constructing an Action-Effect Differentiation Encoder-Decoder module. This component is entrusted with the task of encoding the difference between two scene-graphs—S (pre-action) and (post-action), followed by reconstructing conditioned on S and the encoded differential representation . This stage is critical, as it establishes a structured latent representation that captures the delta induced by specific actions.

Given the CLEVR_HYP dataset [

12], which provides meticulously annotated scene-graph pairs (

S,

), we select a balanced subset of 20k pairs ensuring uniform representation across action categories (add, remove, change, move). The encoder module encodes the relational differences and object-level alterations into an embedding

, while the decoder reconstructs

, optimizing the following joint objective function:

Here,

. Additionally, to ensure robust scene consistency, we introduce a regularization term leveraging scene-graph structural similarity measured via graph edit distance

:

where

denotes the decoder’s reconstruction and

is a scene-graph feature extractor based on Graph Convolution Networks (GCN).

The overall objective becomes:

where

controls the weight of graph consistency regularization.

3.2. Stage-2: Linguistic-to-Action Representation Alignment Module

Building upon the representations obtained in Stage-1, Stage-2 focuses on bridging the gap between linguistic actions and their induced visual differentials. The goal is to map the natural language action description to an action-effect representation that approximates .

We freeze the encoder-decoder module from Stage-1 and introduce a Neural Language-to-Action Representation module. This module employs a stack of embedding layers, an LSTM encoder with a hidden size of 200, followed by multi-head attention and dense layers to capture contextual semantics.

The optimization objective is defined as:

where

. To ensure alignment between

and

, we introduce an auxiliary contrastive loss

formulated as:

where

denotes cosine similarity,

is the temperature hyperparameter, and

N is the batch size.

The cumulative objective becomes:

This dual-objective encourages DEAR to not only generate plausible post-action scenes but also ensures that its action representations are discriminative across varying actions.

3.3. Stage-3: Visual-Linguistic Reasoning Integration with Scene Graph Parsing

In the final stage, we integrate the learned modules with established visual recognition and reasoning backbones. Specifically, we employ a Mask R-CNN [

6] followed by ResNet-34 [

7] pipeline to extract fine-grained object attributes, spatial relationships, and scene semantics, which are subsequently converted into structured scene-graphs.

These generated scene-graphs are then fed into the Scene-Graph Question Answering (SGQA) module inspired by [

18], which utilizes a neuro-symbolic execution engine over scene-graph representations to answer complex queries. This component ensures that the reasoning capabilities of DEAR can be seamlessly evaluated via established benchmarks such as CLEVR [

8].

To ensure smooth integration, we introduce a scene normalization module that aligns feature distributions from pre-trained detectors with our internal representations:

This ensures compatibility across modules while mitigating domain shift issues.

3.4. Comparative Baselines for Evaluation

To validate the effectiveness of DEAR, we compare its performance against two strong baselines reported in Sampat et al. [

12].

(TIE) Text-conditioned Image Editing: This method employs a text-adaptive encoder-decoder augmented with residual gating mechanisms [

16] to synthesize modified images conditioned on the action text. Subsequently, LXMERT [

15], a vision-language transformer, processes the generated image and the associated query to predict answers.

(SGU) Scene-Graph Update: This baseline formulates the action-text understanding as a graph-editing problem. The initial image is translated into a scene-graph, and the action text is parsed into a functional program (FP). Following the approach of Chen et al. [

3], the FP is executed to update the scene-graph, which is then utilized by a neuro-symbolic VQA model [

18] to generate the final answer.

In addition to these baselines, we augment our evaluation by introducing a novel ablation variant of DEAR where the contrastive alignment loss is disabled, allowing us to empirically quantify the significance of explicit action-effect alignment within DEAR’s reasoning process.

4. Experiments

In this section, we conduct comprehensive empirical evaluations to assess the effectiveness, generalization ability, and robustness of our proposed Differential Effect-Aware Reasoner (DEAR) model. We benchmark DEAR against several strong baselines on the CLEVR_HYP dataset [

12], followed by detailed ablation studies, qualitative analyses, and additional diagnostic experiments to uncover the behavior and limitations of our approach.

4.1. Benchmark Comparison with State-of-the-Art Methods

Evaluation Metrics: Following the task design in CLEVR_HYP, we adopt Exact Match Accuracy (%) as our primary evaluation metric, which measures the proportion of correctly predicted answers matching the ground truth.

As shown in

Table 1, DEAR achieves substantial performance gains over existing models, particularly excelling on the most challenging settings involving multi-step actions and complex logical queries. These results underscore the superior reasoning capabilities and better action-effect modeling achieved by DEAR’s explicit differential learning mechanism.

4.2. Fine-Grained Analysis by Action and Reasoning Types

To gain deeper insights, we analyze model performance disaggregated by action and reasoning categories.

The results in

Table 2 and

Table 3 clearly show that DEAR achieves consistent improvements across all action and reasoning types. Notably, DEAR reduces the performance gap on traditionally challenging ‘Add + Move’ and logical combinations such as ‘And’ and ‘Not’ queries, validating the effectiveness of explicit state-differential modeling.

4.3. Qualitative Evaluation and Visualization

We present qualitative results to visually assess DEAR’s reasoning competence. As shown, DEAR accurately captures the intended scene alterations resulting from various action descriptions, even when synonyms or paraphrases are used. Additionally, we show the t-SNE plot of learned action vectors, where DEAR forms distinct and semantically coherent clusters, indicating meaningful action representation learning. We further extend the qualitative study by introducing a confusion matrix of action classification results, as presented in

Table 4.

4.4. Robustness and Error Analysis

To further stress-test DEAR’s robustness, we introduce noisy action descriptions by adding irrelevant modifiers or introducing paraphrased variants.

Table 5 shows the accuracy degradation compared to clean queries.

The error analysis reveals that the majority of failures stem from ambiguous actions (e.g., where both ‘remove’ and ‘change’ might be plausible) or occlusion-induced visual ambiguities.

4.5. Ablation Studies

We perform extensive ablations to evaluate the contribution of DEAR’s key components, including the differential learning module, action vector dimensionality, and data size requirements. The results, shown in

Table 6, and newly introduced

Table 7, confirm the indispensable role of Stage-1 in enabling strong action-effect reasoning and identify 125 as the optimal action vector length.

4.6. Extended Diagnostic: Compositional Generalization to Unseen Actions

To evaluate DEAR’s compositional generalization, we design a new test set combining unseen combinations of action sequences (‘Remove + Move + Change’). The results in

Table 8 show that DEAR significantly outperforms baselines, highlighting its compositional reasoning strength.

5. Conclusions

The ability to reason about the intricate interplay between actions and their consequences is widely recognized as a cornerstone of human intelligence and decision-making processes. As artificial agents increasingly permeate human environments, endowing them with such sophisticated reasoning capabilities becomes paramount for achieving seamless, context-aware, and trustworthy interactions. In this paper, we introduced the Differential Effect-Aware Reasoner (DEAR), a novel and data-efficient framework meticulously designed to address this challenging goal within the context of vision-language reasoning.

Our proposed DEAR framework advances the state-of-the-art by introducing an explicit and interpretable action-effect modeling mechanism, which systematically leverages paired scene-graph differentials to ground action semantics. Unlike previous methods that primarily relied on implicit feature manipulation or heuristic program generation, DEAR formulates action reasoning as a structured state transition modeling problem, fostering more robust generalization and enhanced interpretability.

We operationalized our approach through a carefully designed three-stage architecture. The first stage learns explicit state differentials by observing pre- and post-action scene-graph pairs, enabling the model to internalize fine-grained relational shifts induced by diverse action types. The second stage bridges natural language actions to these visual differentials via a neural alignment module, ensuring that linguistic cues can effectively trigger accurate visual predictions. Finally, the third stage integrates the learned modules into a reasoning pipeline capable of answering complex visual queries over modified scenes.

Through extensive experiments on the CLEVR_HYP benchmark, our method demonstrates superior performance across multiple evaluation splits, consistently surpassing strong baselines in both accuracy and generalization to unseen action combinations and complex logical queries. Additionally, our ablation studies reveal the indispensable role of DEAR’s state-differential learning component in enabling these gains. Our qualitative analyses further confirm that DEAR learns meaningful and disentangled action representations, which manifest as semantically coherent clusters in the learned embedding space.

Beyond empirical validation, DEAR exhibits several desirable properties, including data efficiency and robustness to linguistic variations, as evidenced by our robustness evaluations and compositional generalization tests. These qualities position DEAR as a promising foundation for building real-world AI systems capable of interacting with dynamic environments and collaborating effectively with humans in complex physical tasks.

Despite its strengths, DEAR also opens several avenues for future exploration. Currently, our approach focuses on a finite set of predefined action types and operates within a synthetic domain. Extending DEAR to support open-ended and ambiguous real-world actions, possibly incorporating uncertainty modeling and probabilistic reasoning, remains an exciting direction. Furthermore, integrating DEAR with embodied agents and testing its capabilities in embodied reasoning scenarios, such as embodied question answering or task planning, could unlock new potentials for AI-human collaboration.

In conclusion, we believe DEAR offers a meaningful step forward in equipping AI agents with structured and interpretable action-effect reasoning abilities, and we hope this work will inspire further research at the intersection of scene understanding, commonsense reasoning, and grounded language understanding.

References

- Banerjee, P.; Baral, C.; Luo, M.; Mitra, A.; Pal, K.; Son, T. C.; and Varshney, N. 2020. Can Transformers Reason About Effects of Actions? arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.09938. [CrossRef]

- Baral, C. 2010. Reasoning about actions and change: from single agent actions to multi-agent actions. In In KR.

- Chen, L.; Lin, G.; Wang, S.; and Wu, Q. 2020. Graph edit distance reward: Learning to edit scene graph. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 539–554. Springer.

- Davis, E.; and Marcus, G. 2015. Commonsense reasoning and commonsense knowledge in artificial intelligence. In Communications of ACM. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Yang, S.; Chai, J.; and Vanderwende, L. 2018. What action causes this? towards naive physical action-effect prediction. In In ACL.

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; and Girshick, R. B. 2017. Mask R-CNN. In IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, ICCV 2017, Venice, Italy, October 22-29, 2017, 2980–2988. IEEE Computer Society.

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; and Sun, J. 2016. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2016, Las Vegas, NV, USA, June 27-30, 2016, 770–778. IEEE Computer Society.

- Johnson, J.; Hariharan, B.; van der Maaten, L.; Fei-Fei, L.; Zitnick, C. L.; and Girshick, R. B. 2017. CLEVR: A Diagnostic Dataset for Compositional Language and Elementary Visual Reasoning. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2017, Honolulu, HI, USA, July 21-26, 2017, 1988–1997. IEEE Computer Society.

- McCarthy, J.; et al. 1960. Programs with common sense. RLE and MIT computation center Cambridge, MA, USA.

- Park, J. S.; Bhagavatula, C.; Mottaghi, R.; Farhadi, A.; and Choi, Y. 2020. Visualcomet: Reasoning about the dynamic context of a still image. In In ECCV.

- Patel, M.; Gokhale, T.; Baral, C.; and Yang, Y. 2022. Benchmarking Counterfactual Reasoning Abilities about Implicit Physical Properties. In NeurIPS 2022 Workshop on Neuro Causal and Symbolic AI (nCSI).

- Sampat, S. K.; Kumar, A.; Yang, Y.; and Baral, C. 2021. CLEVR_HYP: A Challenge Dataset and Baselines for Visual Question Answering with Hypothetical Actions over Images. In In NAACL:HLT.

- Sampat, S. K.; Patel, M.; Das, S.; Yang, Y.; and Baral, C. 2022. Reasoning about Actions over Visual and Linguistic Modalities: A Survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.07568. [CrossRef]

- Shridhar, M.; Thomason, J.; Gordon, D.; Bisk, Y.; Han, W.; Mottaghi, R.; Zettlemoyer, L.; and Fox, D. 2020. Alfred: A benchmark for interpreting grounded instructions for everyday tasks. In In CVPR.

- Tan, H.; and Bansal, M. 2019. LXMERT: Learning Cross-Modality Encoder Representations from Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (EMNLP-IJCNLP), 5100–5111. Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Vo, N.; Jiang, L.; Sun, C.; Murphy, K.; Li, L.; Fei-Fei, L.; and Hays, J. 2019. Composing Text and Image for Image Retrieval - an Empirical Odyssey. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2019, Long Beach, CA, USA, June 16-20, 2019, 6439–6448. Computer Vision Foundation / IEEE.

- Yang, Y.; Panagopoulou, A.; Lyu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Yatskar, M.; and Callison-Burch, C. 2021. Visual Goal-Step Inference using wikiHow. In In EMNLP.

- Yi, K.; Wu, J.; Gan, C.; Torralba, A.; Kohli, P.; and Tenenbaum, J. 2018. Neural-Symbolic VQA: Disentangling Reasoning from Vision and Language Understanding. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 31: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2018, NeurIPS 2018, December 3-8, 2018, Montréal, Canada, 1039–1050.

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. 2019. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers). Association for Computational Linguistics, 4171–4186.

- Endri Kacupaj, Kuldeep Singh, Maria Maleshkova, and Jens Lehmann. 2022. An Answer Verbalization Dataset for Conversational Question Answerings over Knowledge Graphs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2208.06734 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Magdalena Kaiser, Rishiraj Saha Roy, and Gerhard Weikum. 2021. Reinforcement Learning from Reformulations In Conversational Question Answering over Knowledge Graphs. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval. 459–469.

- Yunshi Lan, Gaole He, Jinhao Jiang, Jing Jiang, Wayne Xin Zhao, and Ji-Rong Wen. 2021. A Survey on Complex Knowledge Base Question Answering: Methods, Challenges and Solutions. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI-21. International Joint Conferences on Artificial Intelligence Organization, 4483–4491. Survey Track.

- Yunshi Lan and Jing Jiang. 2021. Modeling transitions of focal entities for conversational knowledge base question answering. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing (Volume 1: Long Papers).

- Mike Lewis, Yinhan Liu, Naman Goyal, Marjan Ghazvininejad, Abdelrahman Mohamed, Omer Levy, Veselin Stoyanov, and Luke Zettlemoyer. 2020. BART: Denoising Sequence-to-Sequence Pre-training for Natural Language Generation, Translation, and Comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 7871–7880.

- Ilya Loshchilov and Frank Hutter. 2019. Decoupled Weight Decay Regularization. In International Conference on Learning Representations.

- Pierre Marion, Paweł Krzysztof Nowak, and Francesco Piccinno. 2021. Structured Context and High-Coverage Grammar for Conversational Question Answering over Knowledge Graphs. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) (2021).

- Pradeep K. Atrey, M. Anwar Hossain, Abdulmotaleb El Saddik, and Mohan S. Kankanhalli. Multimodal fusion for multimedia analysis: a survey. Multimedia Systems, 16(6):345–379, April 2010. ISSN 0942-4962. [CrossRef]

- Yann LeCun, Yoshua Bengio, and Geoffrey Hinton. Deep learning. Nature, 521(7553):436–444, may 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dong Yu Li Deng. Deep Learning: Methods and Applications. NOW Publishers, May 2014. URL https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/publication/deep-learning-methods-and-applications/.

- Eric Makita and Artem Lenskiy. A movie genre prediction based on Multivariate Bernoulli model and genre correlations. (May), mar 2016a. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/1604.08608.

- Junhua Mao, Wei Xu, Yi Yang, Jiang Wang, and Alan L Yuille. Explain images with multimodal recurrent neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:1410.1090, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Deli Pei, Huaping Liu, Yulong Liu, and Fuchun Sun. Unsupervised multimodal feature learning for semantic image segmentation. In The 2013 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), pp. 1–6. IEEE, aug 2013. ISBN 978-1-4673-6129-3. URL http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/lpdocs/epic03/wrapper.htm?arnumber=6706748. [CrossRef]

- Karen Simonyan and Andrew Zisserman. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv preprint arXiv:1409.1556, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Richard Socher, Milind Ganjoo, Christopher D Manning, and Andrew Ng. Zero-Shot Learning Through Cross-Modal Transfer. In C J C Burges, L Bottou, M Welling, Z Ghahramani, and K Q Weinberger (eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 26, pp. 935–943. Curran Associates, Inc., 2013. URL http://papers.nips.cc/paper/5027-zero-shot-learning-through-cross-modal-transfer.pdf.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Enhancing video-language representations with structural spatio-temporal alignment. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2024. [CrossRef]

- A. Karpathy and L. Fei-Fei, “Deep visual-semantic alignments for generating image descriptions,” TPAMI, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 664–676, 2017.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Retrofitting structure-aware transformer language model for end tasks. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 2151–2161, 2020.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Fei Li, Meishan Zhang, Yijiang Liu, Chong Teng, and Donghong Ji. Mastering the explicit opinion-role interaction: Syntax-aided neural transition system for unified opinion role labeling. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Sixth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 11513–11521, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Wenxuan Shi, Fei Li, Jingye Li, Hao Fei, and Donghong Ji. Effective token graph modeling using a novel labeling strategy for structured sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 4232–4241, 2022.

- Hao Fei, Yue Zhang, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Latent emotion memory for multi-label emotion classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 7692–7699, 2020.

- Fengqi Wang, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Jingye Li, Shengqiong Wu, Fangfang Su, Wenxuan Shi, Donghong Ji, and Bo Cai. Entity-centered cross-document relation extraction. In Proceedings of the 2022 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pages 9871–9881, 2022.

- Ling Zhuang, Hao Fei, and Po Hu. Knowledge-enhanced event relation extraction via event ontology prompt. Inf. Fusion, 100:101919, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Adams Wei Yu, David Dohan, Minh-Thang Luong, Rui Zhao, Kai Chen, Mohammad Norouzi, and Quoc V Le. Qanet: Combining local convolution with global self-attention for reading comprehension. arXiv preprint arXiv:1804.09541, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11719, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jundong Xu, Hao Fei, Liangming Pan, Qian Liu, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Faithful logical reasoning via symbolic chain-of-thought. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.18357, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Matthew Dunn, Levent Sagun, Mike Higgins, V Ugur Guney, Volkan Cirik, and Kyunghyun Cho. SearchQA: A new Q&A dataset augmented with context from a search engine. arXiv preprint arXiv:1704.05179, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, Bobo Li, Fei Li, Libo Qin, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Lasuie: Unifying information extraction with latent adaptive structure-aware generative language model. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2022, pages 15460–15475, 2022.

- Guang Qiu, Bing Liu, Jiajun Bu, and Chun Chen. Opinion word expansion and target extraction through double propagation. Computational linguistics, 37(1):9–27, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, Donghong Ji, and Xiaohui Liang. Enriching contextualized language model from knowledge graph for biomedical information extraction. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 22(3), 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Cross2StrA: Unpaired cross-lingual image captioning with cross-lingual cross-modal structure-pivoted alignment. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 2593–2608, 2023.

- Pranav Rajpurkar, Jian Zhang, Konstantin Lopyrev, and Percy Liang. Squad: 100,000+ questions for machine comprehension of text. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.05250, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Bobo Li, and Donghong Ji. Encoder-decoder based unified semantic role labeling with label-aware syntax. In Proceedings of the AAAI conference on artificial intelligence, pages 12794–12802, 2021a. [CrossRef]

- D. P. Kingma and J. Ba, “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization,” in ICLR, 2015.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, Fei Li, and Donghong Ji. Better combine them together! integrating syntactic constituency and dependency representations for semantic role labeling. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 549–559, 2021.

- K. Papineni, S. Roukos, T. Ward, and W. Zhu, “Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation,” in ACL, 2002, pp. 311–318.

- Hao Fei, Bobo Li, Qian Liu, Lidong Bing, Fei Li, and Tat-Seng Chua. Reasoning implicit sentiment with chain-of-thought prompting. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.11255, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jacob Devlin, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers), pages 4171–4186, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL https://aclanthology.org/N19-1423. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Leigang Qu, Wei Ji, and Tat-Seng Chua. Next-gpt: Any-to-any multimodal llm. CoRR, abs/2309.05519, 2023.

- Qimai Li, Zhichao Han, and Xiao-Ming Wu. Deeper insights into graph convolutional networks for semi-supervised learning. In Thirty-Second AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Meishan Zhang, Mong-Li Lee, and Wynne Hsu. Video-of-thought: Step-by-step video reasoning from perception to cognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2024.

- Naman Jain, Pranjali Jain, Pratik Kayal, Jayakrishna Sahit, Soham Pachpande, Jayesh Choudhari, et al. Agribot: agriculture-specific question answer system. IndiaRxiv, 2019.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Wei Ji, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Dysen-vdm: Empowering dynamics-aware text-to-video diffusion with llms. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pages 7641–7653, 2024.

- Mihir Momaya, Anjnya Khanna, Jessica Sadavarte, and Manoj Sankhe. Krushi–the farmer chatbot. In 2021 International Conference on Communication information and Computing Technology (ICCICT), pages 1–6. IEEE, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Fei Li, Chenliang Li, Shengqiong Wu, Jingye Li, and Donghong Ji. Inheriting the wisdom of predecessors: A multiplex cascade framework for unified aspect-based sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the Thirty-First International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, IJCAI, pages 4096–4103, 2022.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Donghong Ji, and Jingye Li. Learn from syntax: Improving pair-wise aspect and opinion terms extraction with rich syntactic knowledge. In Proceedings of the Thirtieth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 3957–3963, 2021.

- Bobo Li, Hao Fei, Lizi Liao, Yu Zhao, Chong Teng, Tat-Seng Chua, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Revisiting disentanglement and fusion on modality and context in conversational multimodal emotion recognition. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5923–5934, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Qian Liu, Meishan Zhang, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Scene graph as pivoting: Inference-time image-free unsupervised multimodal machine translation with visual scene hallucination. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 5980–5994, 2023.

- S. Banerjee and A. Lavie, “METEOR: an automatic metric for MT evaluation with improved correlation with human judgments,” in IEEMMT, 2005, pp. 65–72.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Vitron: A unified pixel-level vision llm for understanding, generating, segmenting, editing. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, NeurIPS 2024,, 2024.

- Abbott Chen and Chai Liu. Intelligent commerce facilitates education technology: The platform and chatbot for the taiwan agriculture service. International Journal of e-Education, e-Business, e-Management and e-Learning, 11:1–10, 01 2021. [CrossRef]

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Xiangtai Li, Jiayi Ji, Hanwang Zhang, Tat-Seng Chua, and Shuicheng Yan. Towards semantic equivalence of tokenization in multimodal llm. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.05127, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jingye Li, Kang Xu, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. MRN: A locally and globally mention-based reasoning network for document-level relation extraction. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021, pages 1359–1370, 2021.

- Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Yafeng Ren, and Meishan Zhang. Matching structure for dual learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, ICML, pages 6373–6391, 2022.

- Hu Cao, Jingye Li, Fangfang Su, Fei Li, Hao Fei, Shengqiong Wu, Bobo Li, Liang Zhao, and Donghong Ji. OneEE: A one-stage framework for fast overlapping and nested event extraction. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pages 1953–1964, 2022.

- Isakwisa Gaddy Tende, Kentaro Aburada, Hisaaki Yamaba, Tetsuro Katayama, and Naonobu Okazaki. Proposal for a crop protection information system for rural farmers in tanzania. Agronomy, 11(12):2411, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, and Donghong Ji. Boundaries and edges rethinking: An end-to-end neural model for overlapping entity relation extraction. Information Processing & Management, 57(6):102311, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Jingye Li, Hao Fei, Jiang Liu, Shengqiong Wu, Meishan Zhang, Chong Teng, Donghong Ji, and Fei Li. Unified named entity recognition as word-word relation classification. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, pages 10965–10973, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mohit Jain, Pratyush Kumar, Ishita Bhansali, Q Vera Liao, Khai Truong, and Shwetak Patel. Farmchat: a conversational agent to answer farmer queries. Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies, 2(4):1–22, 2018.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Hanwang Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Imagine that! abstract-to-intricate text-to-image synthesis with scene graph hallucination diffusion. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, pages 79240–79259, 2023.

- P. Anderson, B. Fernando, M. Johnson, and S. Gould, “SPICE: semantic propositional image caption evaluation,” in ECCV, 2016, pp. 382–398.

- Hao Fei, Tat-Seng Chua, Chenliang Li, Donghong Ji, Meishan Zhang, and Yafeng Ren. On the robustness of aspect-based sentiment analysis: Rethinking model, data, and training. ACM Transactions on Information Systems, 41(2):50:1–50:32, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yu Zhao, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Bobo Li, Meishan Zhang, Jianguo Wei, Min Zhang, and Tat-Seng Chua. Constructing holistic spatio-temporal scene graph for video semantic role labeling. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, MM, pages 5281–5291, 2023.

- Shengqiong Wu, Hao Fei, Yixin Cao, Lidong Bing, and Tat-Seng Chua. Information screening whilst exploiting! multimodal relation extraction with feature denoising and multimodal topic modeling. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pages 14734–14751, 2023.

- Hao Fei, Yafeng Ren, Yue Zhang, and Donghong Ji. Nonautoregressive encoder-decoder neural framework for end-to-end aspect-based sentiment triplet extraction. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 34(9):5544–5556, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kelvin Xu, Jimmy Ba, Ryan Kiros, Kyunghyun Cho, Aaron Courville, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Richard S Zemel, and Yoshua Bengio. Show, attend and tell: Neural image caption generation with visual attention. arXiv preprint arXiv:1502.03044, 2(3):5, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Seniha Esen Yuksel, Joseph N Wilson, and Paul D Gader. Twenty years of mixture of experts. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 23(8):1177–1193, 2012.

- Sanjeev Arora, Yingyu Liang, and Tengyu Ma. A simple but tough-to-beat baseline for sentence embeddings. In ICLR, 2017.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).